Abstract

Bacterial meningitis is a significant public health concern, with over 1.2 million cases reported globally each year. Rwanda is at increased risk of meningitis outbreaks due to its proximity to countries that lie in the meningitis belt. Rwanda has been conducting surveillance and recording meningitis outbreak cases across the country since 2012. We evaluated the meningitis surveillance system at Kibogora Level Two Teaching hospital, Nyamasheke district of Rwanda to assess whether the surveillance objectives were being met. The study was cross-sectional, using purposive sampling to select healthcare providers participating in the meningitis surveillance. Rwanda’s bacterial meningitis data from 2017 to 2021 was collected from clinical registers and Rwanda’s electronic integrated disease surveillance system (eIDSR) from Kibogora Level Two Teaching Hospital catchment area, Nyamasheke district, Rwanda. The study area was chosen because a meningitis outbreak was recorded in the area and its bordering country namely Democratic of Republic of Congo (DRC) prior to the current study period. Information on the participant’s demographics, occupation, training, professional experience, and their perception on the surveillance system were gathered using a structured questionnaire. Meningitis surveillance systems attributes including usefulness, acceptability, and flexibility were assessed and categorized as poor (< 50% score), reasonable (50–69%), good (70–90%), or excellent (> 90%) in reference to the study conducted on the evaluation of the meningitis surveillance system in Luanda Province, Angola in March 2017. Data collected from clinical registers and eIDSR were used to assess core functions of the meningitis surveillance system including accuracy in detection of cases, laboratory confirmation of cases, and availability of evaluation reports. Descriptive statistics were analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel. Thirty-one healthcare providers working on meningitis surveillance in the Kibogora Level Two Teaching Hospital were interviewed. During the period under evaluation, 48 suspected cases of meningitis were identified; 43 (90%) met the surveillance case definition, and only 10 (21%) were reported to eIDSR (completeness). Attributes such as flexibility scored good while stability and acceptability scored reasonable. Out of 48 suspected meningitis cases, only 2 (4%) samples were collected from patients and sent to the hospital laboratory for analysis. This study found a good knowledge level of the meningitis surveillance system among healthcare workers; however, the system’s core functions, such as notification rate and laboratory confirmation were found to have gaps. The notification rate could be improved by conducting regular refresher courses for healthcare workers supporting surveillance system. Moreover, MoH could enhance the implementation of a national policy requiring mandatory CSF sample testing to confirm pathogens for all suspected cases. Future studies should explore performance-based incentives to improve reporting completeness. Rwanda’s experience could provide insights for other low-resource settings facing similar surveillance challenges.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-99538-z.

Subject terms: Health services, Public health

Introduction

Bacterial meningitis is a significant global public health concern, with over 1.2 million cases reported annually, including 135,000 fatalities1. The African Meningitis Belt Member States record an average of 24,000 suspected cases and 1800 deaths each year, with a case fatality rate of 5% to 14% since 2010. The major pathogens causing meningitis include Neisseria Meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus agalactiae1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that since February 2012, the expected global annual mortality due to bacterial meningitis had increased to 170,000, with global mortality rates ranging from 2 to 30%3. After recovering from acute bacterial meningitis, between 10 to 20% of individuals experience severe sequelae like epilepsy, intellectual disability hearing loss, and other neurological abnormalities. Acute bacterial meningitis is more common in developing countries and is the fourth leading cause of disability in these regions1,3.

The WHO Regional Office for Africa (AFRO) and its technical partners adopted the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) strategy in 1998 to build and implement comprehensive public health surveillance and response systems in African nations4. The primary goals of the meningitis surveillance system are early detection and confirmation of outbreaks, tracking trends of particular meningococcal strains, and assessing the effectiveness of preventive measures, such as vaccination campaigns5. Most sub-Saharan African countries were reported to have weak meningitis surveillance systems, which provide limited information to guide control measures6,7. Rwanda implemented IDSR after conducting a countrywide evaluation of the communicable disease surveillance program8. Healthcare providers at district hospitals and health centers enter data into the electronic Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (eIDSR) system. The system requires immediate (within 24 h), weekly (Monday before noon) and monthly reporting of reportable diseases, conditions and or events including meningitis as mandated by the International Health Regulations (IHR) set by WHO; district hospitals should ensure that all health facilities in its catchment area provide the required reports of recommended diseases, including bacterial meningitis that have epidemic potential9.

Rwanda has shown commitment to promoting the use of information technology in healthcare systems, and facilitated rapid implementation of the eIDSR system through establishment of surveillance and reporting mechanisms including building capacity of district hospital rapid response teams on disease surveillance and response. Ministry of Health (MoH) developed core indicators to evaluate performance of the IDSR from the point of entry including community, health centers, district hospitals, and national levels. District Hospitals were strengthened to be the convergence of integration of surveillance activities. The implementation of IDSR involves the development of documents, including guidelines, Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) tools, training of individuals such as IDSR focal persons, data managers and clinicians, and should be followed by the rollout and reporting phases10.

Functioning and evaluation of IDSR were developed based on WHO African Region technical guidelines for integrated disease surveillance and response in the African Region. Core indicators to assess the performance of the IDSR system at the district level include the availability of evidence for the analysis of surveillance data, the number of surveillance recommendation reports for the notified cases, and number of samples sent for bacteriological testing and confirmation at the National Reference Laboratory (NRL)4,9. Studies conducted in Uganda and Sudan reported some gaps in planning and monitoring of the core functions and supporting the surveillance system, such as providing feedback to the stakeholders, data analysis, case notification and case confirmation4,9,11–13.

While successful implementation of IDSR for surveillance of diseases, including meningitis, was reported in Rwanda, limited knowledge is available regarding the evaluation of its effectiveness and prevention and control measures for meningitis. In general, surveillance system attributes include usefulness, simplicity, data quality, representativeness, timeliness, completeness, and flexibility, while core functions are composed of case detection, notification, analysis and interpretation, investigation report, response, feedback report to the stakeholders, evaluation, and recommendations for improvement7,12–14. Rural areas in Rwanda may have more challenges in the detection and response to infectious diseases, including meningitis, and an effective surveillance system can inform effective public health response mechanisms, such as readiness to respond, developing well-informed policies, targeted interventions, and effective resource allocation.

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the meningitis surveillance system in Rwandan rural areas, specifically in catchment area of Kibogora Level Two Teaching Hospital (hereafter referred to as Kibogora Hospital), Nyamasheke district which borders the Democratic of Republic of Congo that experiences recurring meningitis outbreaks15,16. Moreover, a meningitis outbreak was recorded in the study area in 2015 with over 70 suspected cases and 10 confirmed cases recorded and since then evaluation of the surveillance system functionality or efficacy has not been conducted.

Methodology

Study setting

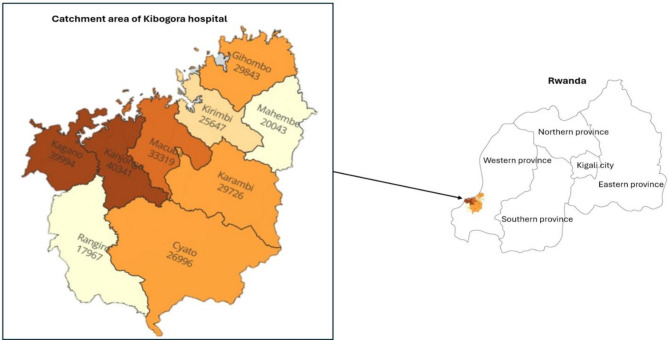

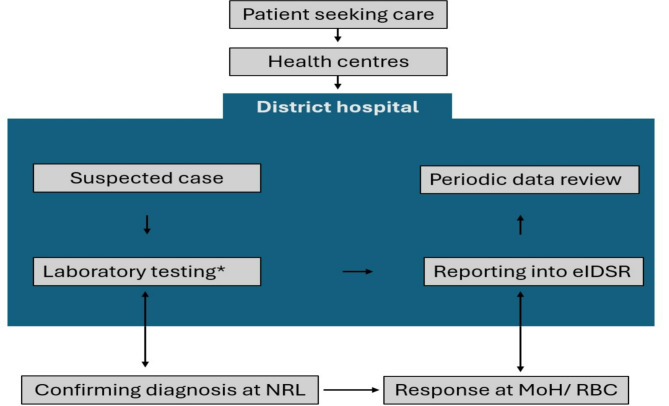

The study was conducted in Nyamasheke district, located in the Western Province of Rwanda. Kibogora Hospital is located in Nyamasheke district, serving 13 health centers located in 9 sectors as shown in the map. The catchment area of Kibogora Hospital had a population of 238,229 people in 2022 (Fig. 1). Suspected cases of meningitis from the community present at health centers and are referred to the Hospital. After clinical evaluation of patients, clinical specimens are collected and sent to the Hospital laboratory for preliminary analysis. The clinician managing the patient notifies every meningitis suspected case to the IDSR focal person, who reports to the Hospital administration and district administration. After laboratory analysis, results are reported to the department requesting analysis, and the remaining specimens are sent to the National Reference Laboratory (NRL) for culture and confirmation. The NRL provides results and sends the feedback to the Hospital’s laboratory and the Rwanda Biomedical Centre (RBC). The data manager of the hospital provides immediate, weekly, and monthly reports on identified cases including zero reports (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Geodemographic map of the study settings.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of meningitis surveillance system at Kibogora hospital. *Laboratory testing of bacterial meningitis in most district hospitals is limited to direct microscopy examination and the diagnosis is confirmed at the national reference laboratory by culture. eIDSR: Electronic integrated disease surveillance and response. NRL: National reference laboratory. MoH: Ministry of health. RBC: Rwanda Biomedical Centre.

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in Nyamasheke district at Kibogora Hospital catchment area. The evaluation took place in October and November 2022. Retrospective data from 2017 to 2021 were also reviewed, and healthcare providers participating in the meningitis surveillance system were interviewed.

Sampling strategy

Thirty-one sample size (N = 31) health care providers were purposively selected based on their roles in meningitis surveillance. Selected staff were nurses, doctors, laboratory staff, and data managers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Doctors and nurses working in internal medicine, emergency, and pediatric departments, as well as laboratory staff and data managers were recruited as they were directly involved in the management, testing, or reporting of case meningitis patients. Staff who did not consent were excluded. Emergency, Pediatric and Internal Medicine departments were selected because they are directly involved with the patient during the case management process, providing care and support to the patients may have meningitis.

Data collection

Primary data were collected by administering the questionnaire designed to evaluate the meningitis surveillance system in terms of usefulness, simplicity, data quality, acceptability, stability, timeliness, completeness, flexibility and study participants knowledge regarding meningitis surveillance system, objective of the system, case definitions and notification deadline. The questionnaire (Supplementary table 1) was developed based on Updated Guidelines for Evaluating Public Health Surveillance Systems from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), customized to evaluate the meningitis surveillance system in Rwanda17,18. The questionnaire was validated in a pilot study involving three healthcare providers. Secondary data was collected using data collection tool (Supplementary table 2) from clinical registers in hospital departments, including emergency and outpatients, internal medicine, pediatrics, IDSR, and Health Management Information System (HMIS) reports, to assess surveillance system attributes and its core functions.

Identified cases were defined according to WHO definitions, as either a suspected, probable, or confirmed meningitis case4. A person with suspected meningitis was defined as an individual with sudden onset of fever (> 38.5 C rectal or 38.0 C axillary) and one of the following signs: neck stiffness, altered consciousness or other meningeal signs. A probable meningitis case was defined as any suspected case with macroscopic aspect of Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) turbid, cloudy or purulent; or with microscopic test showing Gram negative diplococcus. A confirmed meningitis case was defined as isolation or identification of causal pathogen (Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae) from the CSF of a suspected or probable case by culture4,9. Moreover, any recorded cases which didn’t fall under meningitis suspected, probable or confirmed cases were considered as a non-case.

Data analysis

Evaluated attributes (usefulness, data quality, completeness, timeliness, acceptability, stability, flexibility, and simplicity) were scored. The scores were provided to each attribute based on responses from the participants or information available in registers. Level of the knowledge and attributes were then categorized as poor (< 50%), reasonable (50–69%), good (70–90%), or excellent (> 90%) in reference to the study conducted by Pode et al., in Angola, March 20175. Supplementary table 3 shows meningitis surveillance system attributes evaluation indicators. Core functions were evaluated based on indicators related to case detection, notification, analysis and interpretation, investigation report, response, feedback report, evaluation, improvement, laboratory testing, and confirmation, and were categorized using the same scoring system as the attributes. Supplementary table 4 shows indicators for evaluation of meningitis surveillance system core functions. Microsoft Office Excel was used for data analysis.

Ethical consideration

This activity was reviewed by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. Informed consent was waived by Kibogora Hospital Ethics Committee, with the ethical approval reference number: 109/46/10.22/IRB. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Experimental protocol was approved by Kibogora Hospital Ethics Committee, with the ethical approval reference number: 109/46/10.22/IRB. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. To promote privacy and confidentiality, we used the study codes to identify participants. Moreover, study participants data were stored in locked places, and database was protected by password with restricted access to the study staff only.

Results

Socio-demographic and knowledge of health care providers on meningitis surveillance system

The study recruited 31 healthcare providers who were involved in the meningitis surveillance system. Table 1 displays their sociodemographic and professional characteristics. Among study participants, 18 (58%) were male, 20 (65%) had bachelor’s degree, and 14 (45%) had 1 to 4 years of work experience. There were 11 nurses (35%), 11 laboratory staff (35%), 6 physicians (19%), and 3 data managers (10%). The majority of the participants (61%) did not receive any training on the public health surveillance system.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and professional characteristics of the health care providers of study participants (N = 31), Kibogora Hospital from October–November, 2022.

| Characteristics | Health care provider n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 18 (58%) |

| Female | 13 (42%) |

| Education level | |

| Secondary school | 1 (3%) |

| Advanced diploma | 9 (29%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 20 (65%) |

| Masters ‘s degree and above | 1 (3%) |

| Role in the surveillance System | |

| Data manager | 3 (10%) |

| Laboratory staff | 11 (35%) |

| Nurse | 11 (35%) |

| Physician | 6 (20%) |

| Years of work experience | |

| From 1 to 4 years | 14 (45%) |

| From 5 years and above | 13 (42%) |

| Less than one year | 4 (13%) |

| Had training or onsite orientation on surveillance system | |

| Yes | 12 (39%) |

| No | 19 (61%) |

Distribution of knowledge parameters on surveillance system

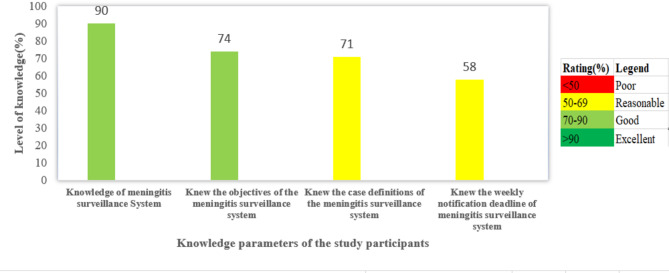

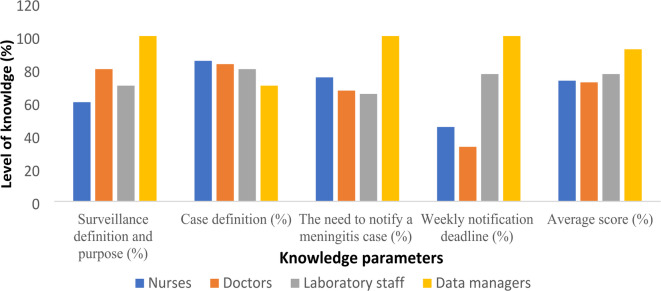

Among study participants, 28 (90%) had knowledge of the meningitis surveillance system definitions and purpose. Moreover, 23 (74%) knew the objectives of the meningitis surveillance system, 22 (71%) knew case definition of meningitis, and 18 (58%) knew the weekly notification deadline (Fig. 3). Among study participants, nurses had knowledge of 100% followed by doctors, nurses had highest knowledge of case definition compared to other study participants while data managers had highest score of 100% on the need to notify a meningitis case and weekly notification followed by laboratory staff. In addition, Data managers had the highest score of correct responses, followed by laboratory staff, doctors and nurses (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Overall score of knowledge parameters on meningitis surveillance system among study participants (N = 31), Kibogora Hospital from October–November, 2022.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of knowledge parameters on surveillance system among study participants, by occupational category (N = 31), Kibogora Hospital from October–November, 2022.

Evaluation of meningitis system core functions

Among 48 suspected meningitis cases found in the Hospital registers, 43 (90%) met the standard case definition of a meningitis suspected case in Rwanda but only 21% were notified through the system. No cases meeting the probable meningitis case definition were found. Additionally, there were no confirmed cases. Furthermore, there was no evidence of routine analysis of surveillance data, interpretation, evaluation, or improvement reports that were conducted for the notified cases. Additionally, only 2 (4%) of the 48 cases had CSF specimens collected for laboratory analysis, and none were sent to the NRL for confirmation. Table 2 shows performance on key indicators by the meningitis surveillance system in Kibogora Hospital, 2017–2021.

Table 2.

Performance on key indicators by the meningitis surveillance system, Kibogora Hospital, 2017–2021.

| Core function | Indicators | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case detection | Number of cases meeting suspected meningitis case definition in Rwanda | 43 (90%) | Good |

| Notification | Number of meningitis suspect cases notified through eIDSR (Completeness) | 10/48 (21%) | Poor |

| Number of meningitis suspect cases notified through eIDSR on time (timeliness) | 10/48 (21%) | Poor | |

| Analysis and Interpretation | Number of available meningitis surveillance data analysis reports | 0/48 (0%) | Poor |

| Investigation and response | Number of investigation report and response required | 48 | |

| Number of investigation report and response done | 0/48 (0%) | Poor | |

| Feedback report | Number of meningitis surveillance feedback reports shared with surveillance stakeholders required | 48 | |

| Number of feedback report provided to the partners | 0/48 (0%) | Poor | |

| Evaluation and improvement report | Number of meningitis outbreak investigation evaluation and improvement report required | 240 | |

| Number of meningitis surveillance evaluation and improvement report available | 0/240 (0%) | Poor | |

| Laboratory testing | Number of samples sent for direct laboratory testing | 2/48 (4%) | Poor |

| Laboratory confirmation | Number of samples sent for bacteriological testing and Confirmation at NRL | 0/48 (0%) | Poor |

Description of attributes of meningitis surveillance system

Overall score of evaluation of attributes showed that the meningitis surveillance system is considered complex with a score of 40%, stable (68%), and useful (44%), with data quality, timeliness and completeness considered poor and each scoring 21% acceptability (65%) and stability (68%) were graded reasonable, while the flexibility (81%) was graded good (Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation attributes on meningitis surveillance system, Kibogora Hospital, Oct–Nov, 2022.

| No | Attributes | Evaluation criteria | Results | Overall score (%) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Usefulness | Number of respondents who reported use of meningitis surveillance data for control and preventive measures of the disease over total number of interviewed | 19/31 = 61% | 44% | Poor |

| Number of respondents who reported to analyse meningitis surveillance data to monitor trend of morbidity or mortality over all respondents | 16/31 = 52% | ||||

| Number of suspected meningitis cases reported on time (within 24 h) in eIDSR system over total meningitis suspected cases recorded in registers | 10/48 = 21% | ||||

| 02 | Data quality | Proportion of suspected meningitis cases reported in eIDSR system over reported meningitis suspect cases in registers | 10/48 = 21% | 21% | Poor |

| 03 | Completeness | Number of suspected meningitis cases presents in eIDSR system with no missing required information over reported meningitis suspected cases in registers | 10/48 = 21% | 21% | Poor |

| 04 | Timeliness | Number of suspected meningitis cases reported on time (within 24 h) in eIDSR over total suspected cases reported in registers | 10/48 = 21% | 21% | Poor |

| 05 | Acceptability | Number of respondents who responded that surveillance system of Meningitis is adequate and suitable for use over all interviewed | 27/31 = 87% | 65% | Reasonable |

| Number of respondents who felt that the meningitis reporting methods standard, understandable and applicable in their working place are acceptable over all respondents | 27/31 = 87% | ||||

| Number of suspected cases reported in system over suspected cases reported in registers | 10/48 = 21% | ||||

| 06 | Stability | Number of respondents reported that integration of meningitis surveillance system in eIDSR make it more sustainable over all respondents | 16/31 = 52 | 68% | Reasonable |

| Number of respondents who didn’t experience any reporting system outages that compromised the surveillance activities over all respondents | 26/31 = 84% | ||||

| 07 | Flexibility | Number of respondents who respond that current reporting system is able to admit changes and modification, when necessary, over-all respondents | 25/31 = 81% | 81% | Good |

| 08 | Simplicity | Number of respondents who considered reporting in meningitis surveillance system to be simple over all respondents | 12/31 = 39% | 41% | Poor |

| Number of respondents who felt that the case definition is easy to understand over all interviewed | 18/31 = 58% | ||||

| Number of respondents who respond that completion of registers, meningitis reporting form and or IDSR system are simple over all interviewed | 15/31 = 48% | ||||

| Numbers of suspected meningitis present in system over recorded cases in registers | 10/48 = 21% |

Discussion

This study evaluated the meningitis surveillance system in a rural area of Rwanda at Kibogora Hospital, located in Nyamasheke district. The majority of the study’s participants, who were healthcare providers that participate in surveillance of meningitis at this facility, completed a bachelor’s degree (65%). High educational level of healthcare providers working on meningitis surveillance system might explain good knowledge level of study participants. However, to ensure a continuous efficiency of health system functions including meningitis surveillance, training of healthcare providers is essential, and we found that 61% of the healthcare providers did not receive any type of public health surveillance training including meningitis surveillance.

The good knowledge level of the meningitis surveillance system (90%), and reasonable awareness of the notification deadlines (58%) observed in this study were higher than those reported in Angola, where the knowledge of the surveillance system (11.5%) and awareness on the notification deadlines (15.4%) were poor. Potential reasons contributing to this difference could be explained by the discrepancy in the level of education, where in our study, 97% of study participants had a high educational level, higher than the educational level (45%) reported in Angola among health care workers5. The training rate (39%) observed in this study is lower than reported in Sudan (52%) in 201511, but higher than the training reported rate in Angola (14%) in 2017, indicating a significant capacity building issue in Africa. Potential factors contributing to this scarcity in training include limited training opportunities, and gap in knowledge sharing, where trained staff might not train the peers5.

The meningitis surveillance system demonstrated reasonable effectiveness, particularly in its stability (68%) and acceptability (65%) among healthcare workers. However, critical weaknesses were identified in usefulness (44%), simplicity (41%), case completeness (21%) and laboratory testing rates (4%), indicating significant underreporting and sample collection failures. The low case notification rate (21%) suggests barriers in real-time data entry and healthcare worker compliance, which could be linked to the limited training of health care workers. Addressing these limitations requires enhanced surveillance training, mandatory CSF sample collection protocols, and timely reporting of the results in the eIDSR system. Timely reporting could be enhanced by implementing an automated alert system within eIDSR to remind healthcare workers of reporting deadlines. An alternative way of promoting data reporting could be initiating a new approach of incentives to boost compliance, by giving financial benefits to the healthcare providers with good performance in data reporting. This incentive-based approach was found effective in improving reporting in some countries19–21.

The findings were consistent with a study done in Angola where only one third of healthcare providers participating in meningitis surveillance felt it was simple (33.3%)5. In contrast, a qualitative study conducted in Ghana reported that most health care workers perceived the meningitis surveillance system to be simple17. The difference could be attributed to the fact that most of the healthcare providers in the study conducted in Ghana were trained about their role and requirements of the meningitis surveillance system, which made them feel comfortable with the system.

We found that the meningitis surveillance system core functions including notification, confirmation, analysis, interpretation, and reporting were poorly performed and monitored. Most cases identified at the hospital met the meningitis suspected case definition in Rwanda (90%), Lab results showed that 4% were having normal macroscopic aspect and having zero white blood cell under microscopy and stained negative for gram stain, but there was no documentation of laboratory confirmation at the NRL. This was in agreement with the study conducted in Uganda and in Sudan where most of the surveillance system core functions were poorly monitored13. Similarly a study conducted in Sudan found that in one-third of the hospitals, CSF bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity tests were unavailable among rural hospital settings11. Such similarity in these different settings could be linked to the gap in knowledge about the surveillance system in both settings.

In Ghana, samples of cerebral spinal fluid from suspected cases were promptly delivered to the Public Health Reference Laboratory to identify meningitis cases, but low sensitivity and low positive predictive value were found17. Given the variability in infectious agents, characterisation of the etiological agent causing meningitis at the NRL could help design contextual-specific interventions, and help clinicians understand effectiveness of antibiotic response.

Investigation and evaluation reports for the surveillance system were not found; MoH recommends that district hospitals coordinate surveillance activities in the catchment areas and make periodic evaluation reports. Lack of investigation and evaluation reports could limit public health surveillance system utility in the area. Early detection of diseases that might cause epidemics can help to prevent transmission by identifying high-risk individuals and developing evidence-based interventions. Effective evaluation is essential to address challenges faced by system users, and could optimize usefulness of the system5,9.

Limited studies are available to compare use of IDSR for the surveillance of meningitis and other diseases in Rwanda, which calls for attention to public health practitioners. Moreover, evaluation of surveillance systems for infectious diseases provides opportunities for improvement by highlighting challenges healthcare providers encounter in the process of detecting cases, reporting, and using system information to prevent diseases. While the high performance of a surveillance system testifies to a well-functioning health system, the poor performance we found can call for interventions like training of healthcare providers on IDSR and meningitis surveillance system, which is an integral part of an effective surveillance system.

Although this study was conducted in catchment areas of Kibogora hospital, mostly representing Nyamasheke district, it is generalizable to other remote areas in Rwanda as, the meningitis national surveillance systems are coordinated in the same manner by MoH. Moreover, the available resources, such as the staff qualifications, diagnostic capabilities and reporting mechanisms are comparable to the rest of rural areas in the country.

However, our study illustrated some limitations. All attributes were not evaluated such as representativeness, predictive positive value and predictive negative value due to the lack of some data such as laboratory results that confirm those suspected meningitis cases. Moreover, we collected some data by requesting the participants to self-report their practices and perceptions, which could have resulted in a recall bias, but we mitigated this limitation by comparing the self-reported data with the information available in the clinical registers. This triangulation by using multiple sources of information increased the confidence in quality of reported findings.

Conclusion

This study found a good knowledge level of the meningitis surveillance system among healthcare workers; however, the system’s core functions, such as notification rate and laboratory confirmation were found to have gaps. The notification rate could be improved by conducting regular refresher courses for healthcare workers supporting surveillance system. Moreover, MoH could enhance the implementation of a national policy requiring mandatory CSF sample testing to confirm pathogens for all suspected cases. Future studies should explore performance-based incentives to improve reporting completeness. Rwanda’s experience could provide insights for other low-resource settings facing similar surveillance challenges.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

S.N and J.C.N conceptualized the study, collected, analyzed and interpreted the data. S.N drafted the first version of the manuscript. E.N and J.N analyzed, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. A.U and C.S reviewed the study protocol, interpreted the results, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies. This study has been supported by The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, with technical assistance provided by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Data availability

The dataset used in this study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mazamay, S. et al. An overview of bacterial meningitis epidemics in Africa from 1928 to 2018 with a focus on epidemics ‘outside-the-belt’. BMC Infect. Dis.21(1), 1027. 10.1186/s12879-021-06724-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Framework for the implementation of the global strategy to defeat meningitis by 2030 in the who African region. Brazzaville (2021).

- 3.Kaburi, B. B. et al. Evaluation of the enhanced meningitis surveillance system, Yendi municipality, northern Ghana, 2010–2015. BMC Infect. Dis.17(1), 306. 10.1186/s12879-017-2410-0 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Technical Guidelines for Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response in the African Region: Third edition. Brazzaville (2019).

- 5.N’dongala Pode, D. D., Esteves Pires, J., Ventura, F. B., António, R. M. & Ajumobi, O. O. Evaluation of the meningitis surveillance system in Luanda Province, Angola. J. Interv. Epidemiol. Public Health1, 1. 10.37432/jieph.2018.1.1.6 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwambana-Adams, B. A. et al. Toward establishing integrated, comprehensive, and sustainable meningitis surveillance in Africa to better inform vaccination strategies. J. Infect. Dis.224(Supplement_3), S299–S306. 10.1093/infdis/jiab268 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novak, R. T. et al. Future directions for meningitis surveillance and vaccine evaluation in the meningitis belt of Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Infect. Dis.220(Supplement_4), S279–S285. 10.1093/infdis/jiz421 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kebede, S. et al. Strengthening systems for communicable disease surveillance: creating a laboratory network in Rwanda. Health Res. Policy Syst.9(1), 27. 10.1186/1478-4505-9-27 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health. Technical guideline for integrated disease surveillance and response, Kigali (2012).

- 10.Thierry, N. et al. A national electronic system for disease surveillance in Rwanda (eIDSR): Lessons Learned from a successful implementation. Online J. Public Health Inform.6(1), e61291. 10.5210/ojphi.v6i1.5014 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baghdadi, I. A. A. Assessment of core and support functions of case-based surveillance of meningitis in hospitals in Khartoum State in 2015 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.WHO. Standard operating procedures for surveillance of meningitis preparedness and response to epidemics in Africa, no. October (2018).

- 13.Ario, A. R. et al. Evaluation of public health surveillance systems in refugee settlements in Uganda, 2016–2019: lessons learned. Confl. Health16(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s13031-022-00449-x (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azevedo, M. J. The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities, 1–73 (2017). 10.1007/978-3-319-32564-4_1.

- 15.Mazamay, S. et al. Understanding the spatio-temporal dynamics of meningitis epidemics outside the belt: The case of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). BMC Infect. Dis.20(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s12879-020-04996-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manegabe, J. T., Kitoga, M., Mwilo, M., Yoyu, J. & Archippe, B. M. Identified bacteria and virus in the cerebrospinal fluid of under five years hospitalized children for clinical meningitis at Panzi Hospital in the Eastern Part of DRC. Open J. Pediatr.13(05), 676–688. 10.4236/ojped.2023.135076 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apanga, P. & Awoonor-Williams, J. An evaluation of meningitis surveillance in Northern Ghana. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Heal.12(2), 1–10. 10.9734/IJTDH/2016/22489 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.German, R. R. et al. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: Recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep.50(13), 1–35 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaburi, B. B. et al. Evaluation of the enhanced meningitis surveillance system, Yendi municipality, northern Ghana, 2010–2015. BMC Infect. Dis.17(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12879-017-2410-0 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keusch, G. T., Pappaioanou, M., Gonzalez, M. C., Scott, K. A. & Tsai, P. Sustaining Global Surveillance and Response to Emerging Zoonotic Diseases (2009). http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12625.html [PubMed]

- 21.Zalwango, J. F. et al. Understanding the delay in identifying Sudan Virus Disease: Gaps in integrated disease surveillance and response and community-based surveillance to detect viral hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis.24(1), 754. 10.1186/s12879-024-09659-5 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.