Abstract

Riboswitches are non-coding RNA sequences that control cellular processes through ligand binding. Conformational heterogeneity is fundamental to riboswitch functionality, yet this same attribute makes structural characterization of these mRNA elements challenging. Here, we use a combination of molecular dynamics and cryo-electron microscopy to expound the flexible nature of the glycine riboswitch tandem aptamers and characterize diMerent structural populations. We find that Mg2+ partially stabilizes the fully folded state, resulting in one-third of the particles adopting a unique “walking man” conformation, consisting of a rigidified core and two dynamic helices, and two-thirds adopting distinct, partially folded states. Glycine interactions double the relative population of fully folded particles by stabilizing a conserved inter-aptamer Hoogsteen base pair, enabling our capture of a 2.9 Å structure for this RNA-only system. The population data show that glycine and Mg2+ operate synergistically: glycine enhances Mg2+ occupancy, while Mg2+ drives glycine specificity. Our findings indicate that cryo-electron microscopy oMers a promising avenue to characterize RNA folding ensembles.

Introduction

RNAs are structurally and functionally heterogeneous molecules that are essential and abundant in all known organisms. In bacteria, for example, RNA accounts for nearly 20% of the entire dry mass of the cell1. Despite their significance, RNA structure is still poorly characterized and diMicult to predict when compared to protein structure2. Indeed, of the >233,000 structures in the PDB in March of 2025, less than 1% are RNA-only structures, and a small fraction of those represent complex structures under 3 Å3. Issues with obtaining high-resolution structures of RNA are derived from the molecule’s two-fold heterogeneity. Firstly, the sugar-phosphate backbone has many degrees of freedom, resulting from seven torsion angles for each residue4. This leads to diMiculties in signal averaging at the atomic level. Secondly, RNA secondary and tertiary structures are surprisingly malleable and prone to kinetic trapping in local free energy minima5. Their folds are often highly dependent on solution conditions6–8 or minor diMerences in transcriptional start sites9. RNA structural characterization methods often produce either complex data resulting from the convolved signals of divergent states (as in the case of 2D probing methods or NMR), or a single snapshot of a dynamic system (as in the case of X-ray crystallography). While these methods are extraordinarily useful for describing some aspects of RNA structure, recent advancements in cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) data collection and processing have made it possible to simultaneously characterize heterogeneity and produce high-resolution information10–13, while removing signal from misfolded particles.

Riboswitches are RNA-based regulatory elements residing in mRNA that undergo structural changes in response to specific metabolites like glycine14, guanine15, SAM16, and many others. Structural heterogeneity is therefore fundamental to riboswitch functionality. Riboswitches are typically located in 5′-untranslated regions of mRNA, where they operate in cis to either transcriptionally or translationally regulate the expression of downstream genes17,18. Notably, riboswitches often control genes that metabolize or transport the very compounds that bind to them, creating an extremely eMicient feedback loop. Riboswitches generally consist of a ligand-binding aptamer domain, and a regulatory region, called the expression platform. Aptamer domain interactions with the ligand trigger global rearrangements in riboswitch structure, leading to either upregulation (ON-switch) or downregulation (OFF-switch) of target genes18. In some cases, such as in the glycine riboswitch family, homologous ON and OFF switches have both been identified, with downstream genes dictating the regulatory mechanism19.

Glycine riboswitches exhibit unusual functional and mechanistic diversity, extending beyond their simple ON/OFF role. DiMerent homologs can function as either transcriptional or translational riboswitches and may contain either a single glycine-binding aptamer domain or a pair of aptamer domains (Figure 1A). Riboswitches with two aptamer domains are referred to as “tandem riboswitches” and their functional states are often described using Boolean logic20. In the case of the glycine riboswitch, where both aptamers bind glycine molecules to regulate a shared expression platform, an AND logic gate is typically ascribed. This would mean that each aptamer must bind a glycine molecule to eMectively regulate the downstream gene.

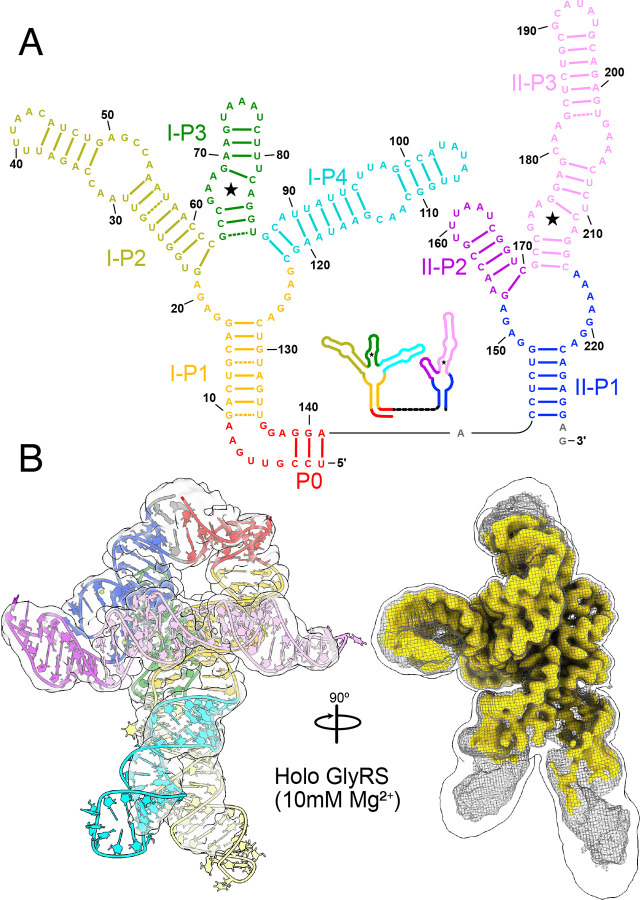

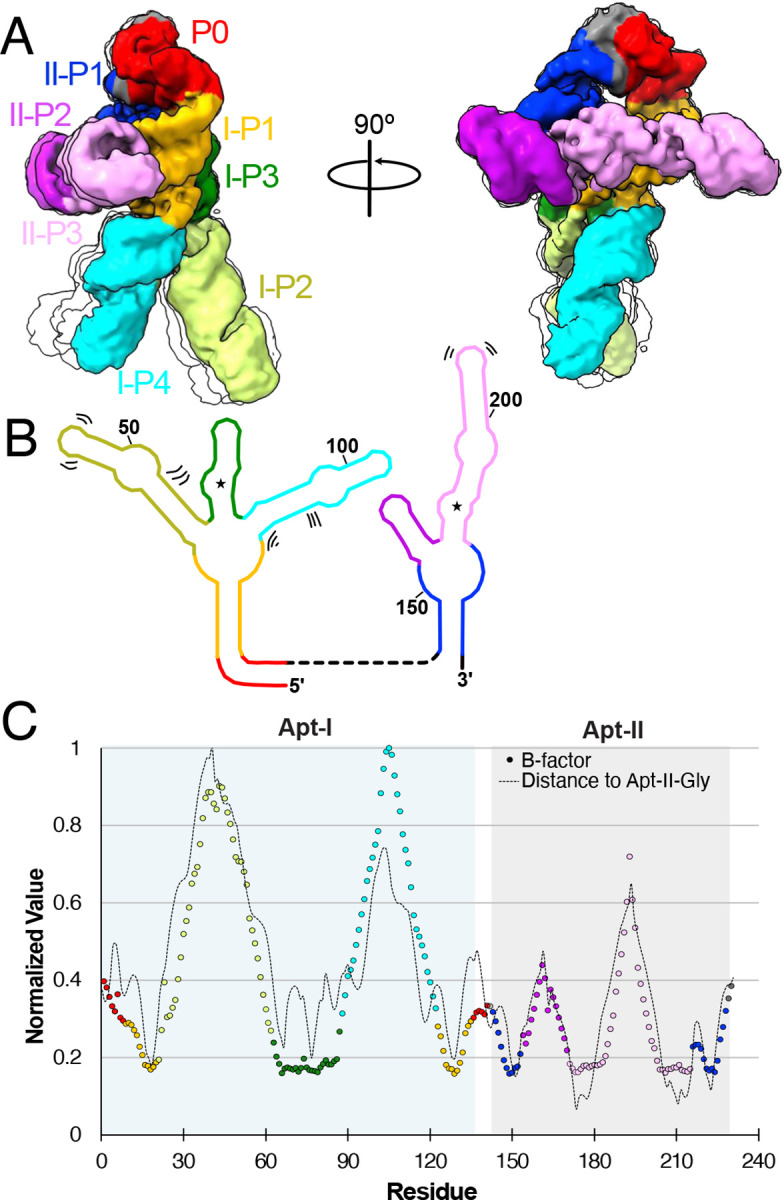

Fig. 1: Overall walking man fold for the holo glycine riboswitch.

a Secondary structural representation of the tandem glycine riboswitch aptamers, colored to highlight structural elements. Stars denote glycine binding pockets. A schematic representation is included as an inset. b Cryo-EM density of the holo glycine riboswitch structure, with the model colored consistent with panel a. A triple overlay of raw (mesh), sharpened (gold), and gaussian filtered (silhouette) maps is shown on the right to demonstrate how diMerent regions of the model were fit and refined.

The distinctive architecture of the tandem glycine riboswitch has long intrigued riboswitch researchers, leading to extensive biochemical and biophysical investigations14,19,21–27. Initial investigations demonstrated that some glycine riboswitch (glyRS) constructs displayed cooperative glycine-binding behavior, where binding of glycine to one aptamer increased the aMinity of the other aptamer for glycine14,22,23. However, subsequent research identified a conserved kink-turn interaction between a leader and linker region, which inhibits glycine binding cooperativity and facilitates both riboswitch folding and glycine interactions28,29. These findings led to the suggestion that the observed glycine binding cooperativity might have been due to the truncated constructs. The prevailing model posits that the function of the tandem glycine riboswitch involves a complex interplay between aptamer dimerization and glycine binding. Detailed analyses via equilibrium dialysis assays and site-directed mutagenesis indicate that a single aptamer is suMicient to drive glycine binding, and this interaction in turn stabilizes the tertiary structure of the riboswitch, facilitating gene regulation21,26,27,30. Importantly, RNA folds for riboswitches are also highly sensitive to the electrostatic environment of the solution due to their intricate tertiary folds and complex interactions with Mg2+ ions31,32. Cooperativity in riboswitches may be attributed to Mg2+ interactions leading to increased aMinity for target ligands33,34. Understanding how Mg2+ and other cations impact the populations of various conformational states of the ensemble is therefore imperative to understand RNA folding.

Here, we use a combination of cryo-EM and molecular dynamics simulations (MD) to characterize and depict the structural diversity inherent in the tandem aptamer domains of the Vibrio cholerae glycine riboswitch in three conditions: (i) without ligand or divalent cation, (ii) in the presence of Mg2+, and (iii) with both Mg2+ and glycine. Our analyses led to a “walking man” structure for the fully folded glycine riboswitch (Figure 1B), resolvable to 2.9 Å in the holo complex and to 3.3 Å in the absence of glycine. By exhaustively picking particles, we were able to generate a comparative ensemble of maps for each condition, which revealed several distinct core folds that are stable in the presence of Mg2+, and partially stabilized in the absence of Mg2+. While Mg2+ appears to shift the equilibrium toward folded conformations, and notably stabilizes the individual aptamers, glycine shifts the population of fully folded glycine riboswitch from approximately one to two thirds. Indeed, by comparing the diMerences in the electrostatic potential maps in the presence or absence of glycine, we show that a conserved inter-aptamer Hoogsteen base pair is held in a more consistent and proximal arrangement in the presence of glycine, leading to stabilization of the entire riboswitch fold.

Within the active sites, binding orientations for the glycines were fit based on the cryo-EM density and key interactions were supported by explicit solvent MD, providing a replicable method for combining mid-level resolution with MD to obtain biophysically reliable structures. Both glycine binding sites contain notable density for a coordinated Mg2+ that directly interacts with the carboxyl groups of the glycines. This Mg2+ density is either unidentifiable, or greatly reduced in the absence of glycine, supporting previous suggestions that there is heterotropic cooperative binding between Mg2+ and glycine33,34. Our data provide atomic-level details about the structure and dynamics of the glycine riboswitch, and demonstrate how key ligands modulate the stability of various populations within an RNA’s structural ensemble.

Methods

RNA Preparation

The V. cholerae gDNA template sequence used here (GGCCTTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTCCGTTGAAGACTGCAGGAGAGTGGTTGTTAACCAGATTTTAACATCTGAGCCAAATAACCCGCCGAAGAAGTAAATCTTTCAGGTGCATTATTCTTAGCCATATATTGGCAACGAATAAGCGAGGACTGTAGTTGGAGGAACCTCTGGAGAGAACCGTTTAATCGGTCGCCGAAGGAGCAAGCTCTGCGCATATGCAGAGTGAAACTCTCAGGCAAAAGGACAGAGGAGTGAA) includes both aptamer domains, but lacks the expression platform, and is based on the construct utilized in Kappel et al. (2020)35. The DNA template was generated by polymerase chain reaction using synthetic gblocks (IDT, Coralville, IA), with primers F: 5′ -GGCCTTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′ and R: 5′ -TTCACTCCTCTGTCCTTTTGCC-3′. The RNA was prepared through in vitro T7 RNA polymerase transcription using an AmpliScribe T7 High Yield Transcription Kit (LGC Biosearch Technologies; Hoddesdon, UK). The resulting RNA was then purified using RNAClean XP Beads (Beckman Coulter; Brea, CA) to the manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in sterile Milli-Q water. Five separate preparations of RNA were combined and concentrated using a vacuum concentrator to generate the final 2.5 mg/ml sample. RNA purity was verified using both native and denaturing gel electrophoresis.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection

To compare the impact of Mg2+ and glycine, three RNA samples containing final solutions with 1) no ligands or cofactors, 2) 10mM MgCl2, and 3) 10mM MgCl2 plus 2mM glycine were prepared in parallel and treated equally. Purified RNA was refolded using a modified version of the protocol described previously36. Briefly, RNA solutions containing 1.2mg/ml glycine riboswitch and 25mM MES (pH 6.0) were denatured at 95°C for 4 min and flash cooled on ice for 5 min. Either MgCl2, or MgCl2 and glycine were added to respective samples, and all three RNA solutions were then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were stored at 4°C until grids were prepared (approximately 1 hr).

Refolded RNAs were applied as 3.5 μl aliquots to Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 300-mesh gold grids (EM sciences, Prod. No. Q350AR1.3). Grids were glow discharged with a Gatan Solarus instrument for 30 s at 15 mA before sample application. Grids were blotted for 3 s in an FEI Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific), set to 4 °C and 100% humidity, prior to plunge-freezing into liquid ethane.

Cryo-EM data were collected at the Columbia University Cryo-Electron Microscopy Center (CEC). Data were collected with a pixel size of 0.823 Å on a Titan Krios G3i (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at 300 kV using a Gatan K3 BioQuantum direct electron detector. A total of three Leginon37 data collections were used to generate the structures for the glycine riboswitch without MgCl2 or glycine, with 10mM MgCl2, and with 10mM MgCl2 and 2mM glycine. Data collection statistics are summarized in Extended Data Table 1.

Cryo-EM data processing

The three datasets were processed using cryoSPARC (v4.6.0)38. The procedure is outlined in Extended Data Figure 1. Briefly, in all datasets, movie alignments, drift correction, and dose weighting were done using cryoSPARC’s patched implementations. Micrographs with poor CTF fits or non-ideal ice thickness were removed, resulting in 5338 micrographs for the holo dataset, 5819 micrographs for the MgCl2 dataset, and 4312 micrographs for the no-MgCl2, no-glycine dataset (Extended Data Table 1). For all datasets, particles were first auto-picked using cryoSPARC’s blob picker job to select particles with dimensions from 70Å to 120Å in an unbiased manner. Particles were then extracted with a box size of 256 px (210 Å) and datasets were cleaned using iterative 2D classification to remove obvious junk/spurious classes while conserving the heterogeneity in the sample. For each sample, 10 ab initio models were generated from cleaned particle pools to characterize how ligands and cofactors impact structural heterogeneity. Structures were then heterogeneously refined and aligned using cryoSPARC’s “Align 3D” job (Figure 3, Extended Data Figure 1)38.

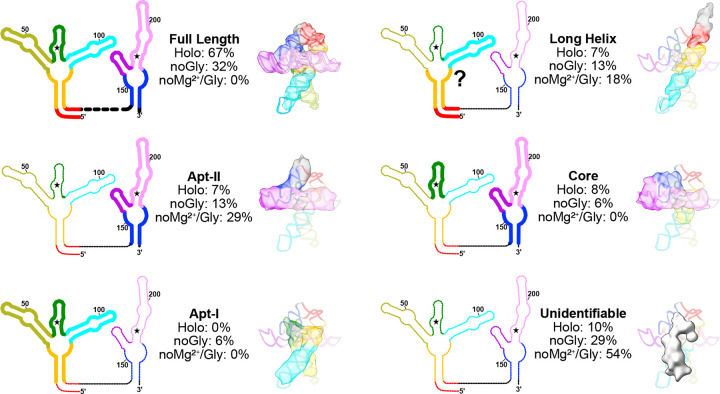

Fig. 3: Populations of glycine riboswitch folds are highly responsive to solution conditions.

Six general classes of structures are show as both a schematic representation and with a representative transparent map overlaid with a potential structural element from the model. Fractional populations within the holo, no glycine, and no glycine/Mg2+ sample are noted for each class. A question mark is used to emphasize the uncertainty inherent in defining which specific residues are involved in the structure.

To generate final maps for the MgCl2 and holo samples, 3D classes consistent with the fully folded construct were selected and filtered via successive rounds of 3D classification. Final datasets were obtained via reference-based motion correction, and non-uniformly refined39 without adaptive marginalization or dynamic masking to produce the final maps. Map resolution was determined by the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between two half-maps at a value of 0.143 with FSC-mask auto-tightening, resulting in ostensible resolutions of 2.9 Å (215,269 particles) for the holo sample, and 3.3 Å for the MgCl2 sample. To better understand the dynamic motions present in the holo complex, the final particle pool was 3D-classified into four maps at a filter resolution of 5 Å (Figure 4). Structural heterogeneity was further explored via 3D-variability analysis with 20 models at filter resolutions of 5 Å (Movie 1 and Movie 2)40. Although attempts were made to further refine and resolve the leg regions using various cryo-EM toolkits that focus on dynamic regions, we were unable to obtain a high-resolution reconstruction of the leg regions.

Fig. 4: The glycine riboswitch P2 and P4 regions are highly dynamic.

a Four representative models derived from 3D classification of the final holo particle pool, limited to 5 Å resolution. One structure is colored based on structural elements, while three others are shown as simple transparent silhouettes. b Schematic representation of secondary structure, with bending and shifting motions denoted by sets of two or three lines. c Normalized B-factor (colored circles) and distance of Apt-II glycine (dashed line) per residue for the holo glycine riboswitch cryoEM structure. Circles are colored consistent with structural elements in a,b. Apt-I and Apt-II regions are shaded in blue and grey, respectively.

Model building and refinement

A low-resolution structure of the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch is available (PDB-6WLT)35, which was used as the initial template for modelling our structures in Coot (v.9.8.95)41. RNA A-form restraints were used extensively to ensure low-resolution areas did not collapse during refinement. Model geometries and fits to maps were adjusted in ISOLDE (v1.8)42 to decrease issues arising from steric clashes, with restraints placed on RNA based pairs. Low-resolution regions in the “legs” and “left arm” were refined in a filtered map to ensure backbone placement was reasonable, but care should be taken to interpret finer details in any of these low resolution regions (Extended Data Figure 2). As it is diMicult to distinguish well-occupied Mg2+ sites from water in cryo-EM electrostatic potential maps, decisions on which molecule to model were based on either biochemical evidence (such as within the glycine binding site), or derived from homologous regions of a previously available 3.55 Å crystal structure of the related Fusobacterium nucleatum glycine riboswitch (PDB-3P49)23. Where neither method was applicable, ligands were left unmodelled to avoid overinterpreting the data. Final refinements were performed using PHENIX (v1.21.1-5286-000)43 real space refinement against the final maps for both the holo and MgCl2 samples. Model statistics are disclosed in Extended Data Table 1. Structures and maps were visualized and presented using ChimeraX44.

Explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations

The structure of the glycine riboswitch obtained in the 10 mM MgCl2 plus 2 mM glycine condition was used to perform all-atom explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations. The riboswitch structure was solvated with the TIP3P water molecules and 10 mM MgCl2. Notably, a bulk concentration of 10 mM Mg2+ ions (bulk is defined by the region >12 Å away from the RNA) was achieved following conducting several cycles of equilibration stages using the protocol described previously45. Moreover, 140 mM K+ ions were added for neutralizing the whole system to net charge zero, which resulted in bulk concentration of 80 mM K+. The resulting systems had approximately 240,000 atoms in total. The amber M99bsc0χOL3 force field for RNA46, amber ff19SB for zwitterionic glycine47, and recently optimized parameters for the ions Mg2+, K+, and Cl− with TIP3P water were used48,49. The cut-off for short-range electrostatics and the Van der Waals interactions was 12 Å, and the PME method50 was used for the long-range electrostatics with a grid size of 1.2 Å. Hydrogen-containing bonds were constrained using the LINCS algorithm to enable a timestep of 2 fs51. To check the stability of glycines in Apt-I and Apt-II in our proposed orientations, we used four unbiased simulations for the timescale of 1 μs. All MD simulations were carried out using the GROMACS v2024.352 patched with PLUMED v2.9.253.

Metadynamics explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations

To further support our proposed glycine orientations, we employed the combined well-tempered and multiple walker metadynamics technique54,55. To enforce reorientation of the glycine in both aptamers, two collective variables for Apt-I and Apt-II defined as the angle between the z-components of vector passing from amino nitrogen to carboxyl carbon atoms of a glycine molecule and z-axis56. To define these collective variables, the whole riboswitch was aligned with respect to z-axis as shown in Figure 6A, and the phosphorus atom position was restrained during the simulations. Three independent simulations for a total timescale of 2 μs were carried out. In each simulation two metadynamics runs, each having 8 walkers, were performed simultaneously by biasing the angle collective variables defined for Apt-I and Apt-II57. Along the collective variable, Gaussians with the height of 1 kJ/mol and width of 1° were deposited at the interval of 2 ps. The bias factor was set to 15, corresponding to tuning temperature of 4200 K. Upon completion of simulations, two-dimensional free energy surfaces as a function of collective variables, distance between Mg2+ and center of mass of glycine and the angle of glycine with respect to z-axis, were calculated using the Tiwary-Parrinello reweighting scheme58.

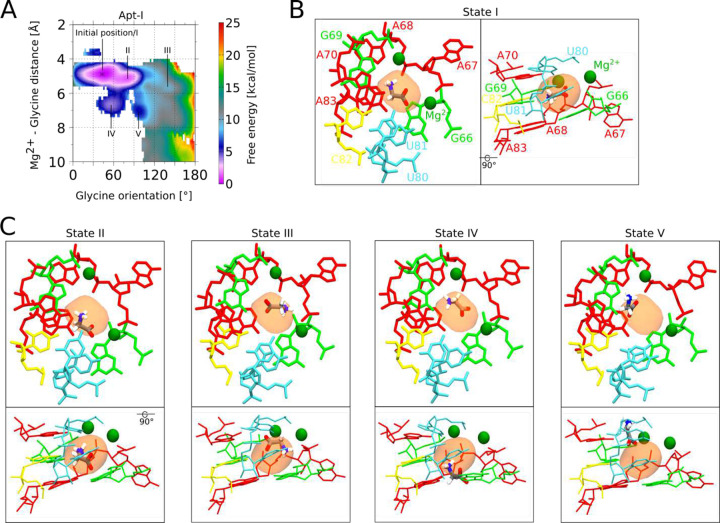

Fig. 6: Glycine binding orientation analysis using all-atom explicit solvent MD simulations.

a Glycine orientation is defined as the angle between the z-components of the vector passing from amino N to carboxyl C of glycine and the z-axis. To facilitate the angles calculations, the whole riboswitch structure is aligned to z-axis in the same manner as shown in the figure. Initial angles for Apt-I and Apt-II glycines are mentioned on subset panels. b Free energy surfaces with respect to two variables: i) distance between the Mg2+ and the center of mass of glycine, and ii) glycine orientation as described in panel a. Surfaces on both left panels for Apt-I and Apt-II glycines are obtained by running four 1 μs long equilibrium (unbiased) simulations, while on the right are derived after performing three 2 μs long metadynamics simulations, where the above described angle variables for both glycines were sampled to reorient glycines in all possible orientations. The starting position of the glycines with respect to both variables are marked with the * symbol on all panels.

Flexible simulations using SMOG

The initial cryo-EM structure was used to generate the SMOG native contact potential59. All simulations were performed using the MD software package GROMACS60. The initial configuration and topology files for GROMACS were generated using the SMOG web tool61. The starting structure was minimized for 10,000 steps using the SMOG native contact potential. MDFIT62,63 and cryo_fit64 were employed for flexible fitting into the generated cryoEM map. To accurately match the cryo-EM density map with the configurational map, a 105-step MD simulation was conducted to evolve the simulation towards a stable structure. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the MD trajectories to gain insights into collective motion. The inbuilt subroutine, gmx covar, in GROMACS was used to generate both eigenvalues and eigenvectors, followed by filtering the individual eigenvectors to analyze the two largest eigenvalues. For visualization, VMD65,66 and UCSF Chimera were utilized.

Results

Holo state of the glycine riboswitch adopts ‘walking man’ fold

To better categorize populations within the folding ensemble, it is important to have a well-resolved reference structure to align partially folded arrangements. Previous small-angle X-ray scattering studies by Lipfert et al. (2007, 2010) have produced low-resolution descriptions of the tandem glycine riboswitch, which demonstrated that it is most stable and compacted in the presence of both Mg2+ and glycine25,34. We therefore first sought to characterize the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch in a solution containing 10mM Mg2+ and 2mM glycine to obtain a reasonably homogeneous sample. Under these conditions, we were able to generate a 2.9 Å electrostatic potential map for the holo glycine riboswitch, which folds into a conformation resembling a “walking man” (Figure 1B, SI Figure 1). The core torso region of this fold (Aptamer-I P1 and P3; Aptamer-II P1 and P3) is well resolved, with clear density around base pairs. In contrast, the arm (Aptamer-II P2 and P3) and leg regions (Aptamer-I P2 and P4) are not as well resolved (Figure 1B, Extended Data Figure 2), despite utilizing several methods that attempt to characterize and refine dynamic regions in cryo-EM structures. This may be due to the relatively small size and multidirectional stepwise motion of the leg regions (described below).

Although it can be diMicult to build initial models for RNA-only systems without collecting 2D probing data35,67, prior work on a holo system for a diMerent species (F. nucleatum), which did not explore the conformational ensemble, yielded a 3.55 Å crystal structure of the glycine riboswitch stabilized by a proteinaceous partner. An excellent previous study also used cryoEM to obtain a 5.7 Å structure of the holo V. cholerae glycine riboswitch, which is 35% longer than the F. nucleatum homolog23,35. While 5.7 Å is insuMicient resolution to make out finer molecular details, this structure, in combination with the F. nucleatum X-ray crystallography structure, served as excellent starting points to build our model (Figure 1B).

As it is diMicult to distinguish well-occupied Mg2+ sites from water in cryo-EM electrostatic potential maps, decisions on which molecule to model were based on either biochemical evidence (such as within the glycine binding site), or derived from homologous regions of a previously available 3.55 Å crystal structure of the related Fusobacterium nucleatum glycine riboswitch (PDB-3P49)23. X-ray crystallography can also take advantage of electron counts, occupancy, and coordination to attempt to distinguish Mg2+ from water68,69. The homologous F. nucleatum crystal structures of the full length23 and aptamer constructs24 were therefore also utilized to corroborate solvent and ion assignments when biophysical evidence was insuMicient. Where neither method was applicable, ligands were left unmodelled to avoid overinterpreting the data.

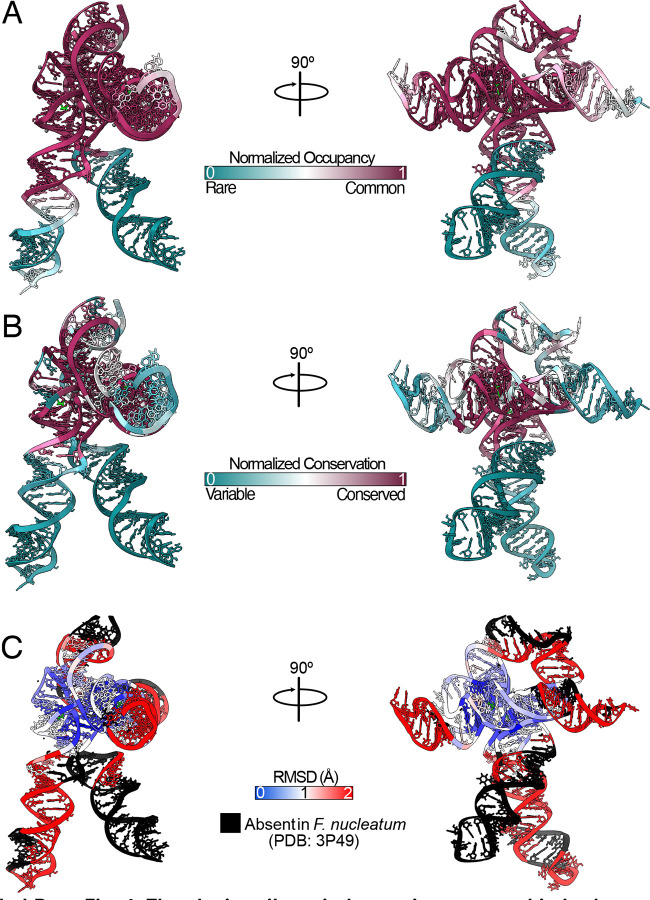

Our cryo-EM study shows that the tandem aptamers of the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch adopt distinct folds, with aptamer one (Apt-I) forming a 4-way junction to fashion the back and leg helices, while aptamer two (Apt-II) forms a 3-way junction to create the arms and head region (Figure 1, Figure 2). The global fold is stabilized by three main inter-aptamer interaction zones: 1) a conserved Hoogsteen base pair (U77-A206 here) between the P3 regions23, 2) three adenines in the loop of Apt-I P3 buried in the minor groove of Apt-II P1, and 3) the reciprocal interaction with four adenine bases of Apt-II P3 binding to a loop in Apt-I P1 (Figure 2). Our findings are consistent with previous chemical probing and crystallography work, which identified these “A-minor” motifs and demonstrated that P1 and P3 are conserved, while P2 and P4 are variable21–24,27. The kink-turn motif is positioned to contribute to tandem aptamer stabilization. We visualize this region and confirm that nucleotides G4-A8 adopt a conformation consistent with a kink-turn motif (7r6p2[0a70; Extended Data Figure 3). Interestingly, the regions of the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch that are best resolved (Figure 1B, Extended Data Figure 2) mirror those that are structurally most conserved among the V. cholerae and F. nucleatum glycine riboswitches (Extended Data Figure 4). These regions also display the highest level of sequence conservation across all known homologs (Extended Data Figure 4)21. This indicates that these folds represent the “core” glycine riboswitch and may provide a means to develop a minimized functional version of this regulatory RNA.

Fig. 2: The full glycine riboswitch fold is stabilized by three main regions of inter-aptamer contacts.

a CryoEM map and model colored to highlight residues derived from Apt-I (light green), Apt-II (pink), or linker regions (grey). b Regions of Inter-aptamer contact. Residues of one aptamer that approach within 2.5 Å of the other aptamer were considered as a contact, leading to three regions involved in stabilization of the fully folded conformation. This includes two sets of A-minor motifs (1,2), and one Hoogsteen base pair (3). CryoEM density for contact regions is extracted to demonstrate fit. A schematic representation of these contact regions is included (right) to emphasize regions involved in stabilization of the full fold. Model and schematic representation are colored to emphasize structural elements.

Exploring the conformational ensemble by investigating non-holo states: Glycine remodels the conformational landscape, stabilizing the fully folded conformation

To understand how glycine and Mg2+ aMect the ensemble of configurational populations of the glycine riboswitch, we broadly picked particles from cryo-EM grids in three conditions: 1) holo glycine riboswitch with 10mM Mg2+ and 2mM glycine, 2) glycine riboswitch with 10 mM Mg2+ without glycine, and 3) glycine riboswitch without Mg2+ and without glycine. Particles were used to generate ten ab initio models for each condition, which were then heterogeneously refined into ten representative structures of the conformational ensemble. When glycine and magnesium are both present, approximately two thirds% of all particles are fully folded (Figure 3 and Extended Data Figure 1). In addition, several distinct classes that resemble the core of the riboswitch are identifiable, as well as one fold reminiscent of Apt-II alone (Figure 3 and Extended Data Figure 1). Our results are consistent with those of previous studies that show that Apt-II is the driver for glycine binding in V. cholerae and the structurally more stable aptamer21,24,27.

The population of fully folded RNA is significantly lower when glycine is absent (Figure 3 and Extended Data Figure 1), accounting for only one third of all picked particles. Instead, the relative population of the potential Apt-II fold is doubled, and a new conformation consistent with an Apt-I fold is now identifiable (Figure 3 and Extended Data Figure 1). The presence of a possible Apt-I class in the absence of glycine, as well as the strong enrichment of fully folded particles when both ligands are present, suggests that glycine helps to stabilize inter-aptamer contacts to shift the single aptamer populations towards the fully folded state.

Nearly 30% of particles belong to unidentifiable classes in the Mg2+-alone sample, compared to 10% in the holo sample (Figure 3 and Extended Data Figure 1). While these low-resolution structures could be artifacts evolving from insuMicient statistical coverage, the shift of populations upon addition of ligands suggests that they are instead intermediates or oM-target, misfolded conformations. In some cases, similar but unidentifiable folds are present in both samples containing Mg2+ (Extended Data Figure 1). It may therefore be possible to use cryo-EM to characterize potentially relevant conformations in RNA folding pathways.

Synergy between Mg2+ and glycine: the glycine riboswitch requires Mg2+ to adopt the fully folded conformation

In contrast to the cases discussed above, no fully folded particles were discernable in the absence of both Mg2+ and glycine (Extended Data Figure 1, Figure 3). Nearly 30% of all picked particles instead adopted a “7-shaped” fold, akin to a portion of the Apt-II structure (Figure 3, Extended Data Figure 1). The relatively lower resolution of maps from these classes indicates that the RNA is dynamic, leading to poor signal averaging. Interestingly, long RNA helices were identifiable in all three conditions, with the population decreasing as the fully folded population increased (Figure 3). These data suggest that either a single long helix, such as the one encompassing P1 and P2 of Apt-I, is particularly stable, or that RNA chains form helical assemblies in solution to facilitate burial of bases.

The glycine riboswitch is highly heterogeneous in the leg regions when fully folded

The degrees of freedom in the RNA backbone manifest not only an ensemble of folds, but also dynamic regions within the folds. To characterize glycine riboswitch dynamics and identify potential hinge regions, we used two approaches: (i) a 3D classification and 3D variability analysis on our final holo particle pool (Movie 1, Movie 2, Figure 4)40, and (ii) structure-based molecular simulations. With the first method, we identified three distinct movements within the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch. First, we observe that the distance between the feet regions increases from 51 Å to 61 Å, and their tangent-tangent angle increases from 51° to 81°. The overall motion the of the leg regions resembles a stepping motion (Movie 1). Second, the core hip regions flex simultaneously, leading to the legs pivoting forward by approximately 9° (Movie 2). The final motion visible is within the head region, where our low-resolution analysis catches movement in the 3’ and 5’ ends of the RNA (Movie1, Movie 2). These movements are partially recapitulated in the PHENIX-derived B-factors, which show that the legs are the most dynamic region (Figure 4). Interestingly, the normalized B-factors correlate well with the distance between each nucleotide and the Apt-II glycine. The glycine binding site is therefore likely to be the most stable part of the holo riboswitch. Although it is unclear what role the more dynamic regions play in riboswitch functionality, it is of note that the most dynamic portion (i.e. Apt-I P4) is present in only 13% of glycine riboswitches21.

To further evaluate the dynamic motions obtained via cryo-EM, we used all-atom structure-based molecular simulations. The RMSF values mirrored the PHENIX-derived B-factors, and the two distinct stepping motions seem in cryoEM were mirrored in the principal component analysis motions derived from the molecular simulations (Movie 3, Movie 4), indicating that molecular simulations can capture molecular motions similar to those derived from cryo-EM variability analysis.

Glycine and Mg2+ bind in a synergistic manner and stabilize inter-aptamer contacts

The conformational ensemble analysis demonstrated that glycine stabilizes the fully folded conformation. To understand the mechanism of stabilization, we solved the glycine riboswitch structure for the most enriched class in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ and compared it to the holo structure. Notably, despite using the same RNA preparation and a similar number of particles (216K in the holo sample and 207K with Mg2+ alone), the resolution was significantly lower in the absence of glycine, yielding a 3.3 Å structure. This diMerence (i.e., lower resolution in the absence of glycine vs. higher resolution in the presence of glycine) may be indicative of structural rigidification by the bound glycine. The overall fold for our RNA construct, which lacks the regulatory expression platform, is essentially identical under the two conditions (Extended Data Figure 1). Indeed, a diMerence map of the electrostatic potentials under either condition demonstrates that all the major changes take place in a localized region surrounding the glycine binding sites (Figure 5).

Fig. 5: Glycine and magnesium synergistically stabilize inter-aptamer glycine riboswitch contacts.

a Transparent cryoEM map of the holo glycine riboswitch, overlaid with a gaussian filtered diMerence map of the holo glycine riboswitch minus the apo glycine riboswitch, demonstrating structural changes are localized to the glycine binding loci. b Schematic representation of the glycine riboswitch secondary structure, colored to emphasize diMerent structural elements. c Enlarged view of regions altered in the presence of glycine, with residues colored consistent with panel b and overlaid with a silhouette view of the diMerence map. Glycine ligands are colored in grey and magnesium ions are shown in lime green. Note the direct path of stabilization between the two glycine residues, connected via the conserved inter-aptamer Hoogsteen base pair (here, U77-A206). Three key regions are further enlarged, with modified density in the Apt-I (1), and Apt-II (2) binding pockets, demonstrating a cooperative interaction between magnesium and glycine in these regions. Movement of U80 and U81 (3) may capture movement required to allow glycine access to the tight binding pocket.

As depicted in the RNA secondary structure diagram (Figure 1A), the two glycine binding sites (denoted by star symbols) reside on diMerent aptamers and appear to be quite distant from each other. Interestingly, in 3D, a clear interaction path is visible between the two glycine binding sites, as seen in the diMerence map (Figure 5C). From Apt-II, glycine binding leads to increased density for an adjacent Mg2+ connected to A206. This adenosine forms the conserved Hoogsteen base pair to U77 in Apt-I23, which is also stabilized by an attached Mg2+ bound to the Apt-I glycine. These data evince a role for glycine where binding leads to stabilization of the fully folded tandem aptamer by rigidifying the inter-aptamer Hoogsteen base pair. It is notable that the magnesium density within the glycine binding pocket is either absent (as in Apt-II) or significantly diminished (as in Apt-I) in the absence of glycine (Figure 5C), even though the magnesium concentration is held constant. Previous work has demonstrated that metabolites and cations bind cooperatively to riboswitches, where aMinity is increased for the metabolite when cations are available, and vice-versa33. While many studies describe cations as working as an ion cloud to oMset the phosphate charges in the RNA backbone, our data reveal that the glycine riboswitch also has two specific Mg2+ binding sites that synergistically interact with glycine within the binding pockets.

Crystallographic studies on individual glycine riboswitch aptamers indicate that glycine fits very snugly within the binding pocket and that the glycine itself is trapped by adjacent magnesium ions24. Our data similarly show compact binding pockets surrounded by several Mg2+ (Extended Data Figure 5). In the Apt-I pocket, U80 and U81 undergo significant conformational transitions between the bound and unbound states (Figure 5C, Movie 3). If the nucleotide U80 were in its apo conformation, it would directly clash with bound glycine, thus necessitating this conformational shift. Additionally, the poorer density in this region in the absence of glycine suggests that these residues are more dynamic in the apo state. This conformational transition may therefore represent a potential pathway for glycine access to the binding pocket.

Explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations help validate glycine orientations

Previous crystallography studies on the F. nucleatum glycine riboswitch at 3.55 Å concluded that the Apt-II glycine is stabilized by direct interactions between the carboxyl group and the equivalent of U81, as well the amino group and G6924. Although the 2.9 Å structure generated here is of insuMicient resolution to confidently orient a small glycine ligand, our data are more consistent with an alternate arrangement where the nitrogen group points towards the adjacent phosphate from residue A68 (Extended Data Fig. 5). To distinguish between these two potential conformations, we performed explicit solvent all-atom molecular dynamics simulations using particle mesh Ewald electrostatics, with an environment of explicit bulk magnesium and potassium ions at 10 mM MgCl2 and 80 mM K+.

First, using the unbiased simulations, we confirm that both glycines maintain our proposed orientations with carboxyl groups facing toward with Mg2+ ions, and with glycine-Mg2+ distances/angles conserved (Figure 6B). In this position and orientation, the amino group of both glycines are consistently directed towards the phosphate of A68 in Apt-I and A175 in Apt-II (Extended Data Fig. 6). Subsequently, enhanced-sampling explicit solvent metadynamics molecular dynamics simulations were carried out that sample the glycine molecules at all orientations. The resulting free energy surfaces show that when glycine maintains the 4 to 6 Å distance from Mg2+ ions, our proposed configuration yielded the most favorable energy basins for both aptamers. Inside these basins, the glycine amino groups always remained oriented towards the phosphate of A68 and A175 in respective aptamers (Extended Data Fig. 6), consistent with our proposed cryo-EM structure. Notably, four other potential metastable states seen for Apt-I pull the displaced glycine out of the corresponding experimental density (Extended Data Fig. 7). Both the explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations and explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations with metadynamics help to corroborate our proposed glycine orientations. These data also suggest that glycines bind to V. cholerae glycine riboswitch in an orientation that diMers from previously described systems. This workflow provides a means to combine mid-resolution cryoEM data with MD to provide higher confidence about ligand-complex orientations.

Discussion

Riboswitches play an important role in metabolism and regulate approximately 4% of bacterial genes71,72. Riboswitch function is often described as regulation via alternation between two mutually exclusive conformations; however, this description belies the ensemble nature of biological macromolecules. In proteins, for example, conformational ensembles can be used to describe the mechanism of action for an enzyme or provide information about the biological role of disordered regions73,74. For RNA, an ensemble description is even more germane, as the significant flexibility inherent to the RNA backbone allows for the adoption of a greater variety of conformations4,64,75,76. NMR studies on the 2’ deoxyguanosine riboswitch have demonstrated that the RNA forms a multifarious set of ON, OFF, and intermediate conformations, even in the presence of ligand77,78. In fact, in vitro transcription experiments suggest that only 70% of the particles in some systems adopt a ligand-bound conformation in the presence of metabolite77. Riboswitch operation can thus be described by population states within an ensemble that shift in accordance with changing buMer conditions79. Here, cryoEM explicitly captures this shift in populations and may, in future studies, illuminate the RNA folding pathway via characterization of low population states.

Our study shows that the glycine riboswitch adopts a highly dynamic “walking man” conformation, with several distinct stepping motions that coalesce in a well-resolved core surrounded by flexible loops and helices (Figure 1, Figure 4). The lack of conservation in the dynamic regions (Extended Data Figure 4)21 suggests that their role is not sequence specific. One potential explanation for this is that they encode protein binding sites, as has been seen in the F. nucleatum glycine riboswitch23, that vary dramatically between species. Alternatively, many studies have described a kinetic attribute in riboswitch regulation, where transcriptional pause sites provide time for the RNA structural rearrangements to mediate gene expression77,78,80. It is therefore possible that these flexible regions modulate the eMect of ligand binding on expression levels by serving as an alternative to transcriptional pause sites.

Within each binding pocket, a coordinated Mg2+ is proximal to the bound glycine (Figure 5). The marked reduction of magnesium density in the absence of glycine is notable. While this could indicate that this region is flexible in the absence of glycine, the local resolution of adjacent residues of this core region (Extended Data Figure 2) suggests this region is relatively restricted. The data are instead more consistent with the absence or low occupancy of magnesium at these loci in this case. We therefore hypothesize that glycine stabilizes Mg2+ within the binding pocket, and that this interaction is one of the main drivers for glycine riboswitch specificity. In support of our conclusion, prior studies revealed a reciprocal cooperativity between ligands and Mg2+, with the presence of one binder increasing the aMinity of the other33. Additionally, one prescient study used SAXS data (radius of gyration) to suggest that there are two specific divalent ion binding sites in the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch, which interact cooperatively with glycine to result in the final compact structure34. This series of RNA-ligand-cation interactions strongly stabilizes the core fold of the glycine riboswitch, suggesting an explanation for the larger question of why this riboswitch uses two adjacent aptamer domains. Based on our data, the presence of two aptamer domains helps the riboswitch achieve a more stable or robust structure. The linked domains may also provide structural redundancy, ensuring that the riboswitch folds correctly and functions eMiciently across diMerent environmental conditions.

Previous work on the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch has demonstrated that Apt-II binds glycine more tightly than Apt-I24. In addition, glycine binding by Apt-II is an enthalpically-driven reaction, while Apt-I interactions are entropically driven24, despite having nearly identical binding sites (Extended Data Figure 5). These results suggest that more distal factors, such as the overall fold of the aptamer, influence the thermodynamics of glycine-aptamer interactions. Our ensemble analysis indicates that Apt-II is more stable than Apt-I in V. cholerae (Figure 3), potentially resulting from the extra G-C bond present within the active site (Extended Data Figure 5). The diMerence in thermodynamic stability may therefore derive from additional folding garnered by glycine interactions with Apt-I, which are not required for Apt-II. Consistently, in some glycine riboswitch homologs, where Apt-I displays the higher aMinity interactions, the extra G-C base pair is found in Apt-I instead of Apt-II21. We speculate that an ensemble analysis of these homologs would yield an inverse finding of aptamer stability, where the population of Apt-I is higher than Apt-II in the absence of glycine and/or Mg2+. Interestingly, several studies have shown that RNA folding and compaction increases as the concentration of Mg2+ increases25,33,34,81, raising the intriguing possibility of enriching partially folded conformations by sampling at various Mg2+ concentrations.

Characterization of sparsely populated states, often the etiological agents of disease, has led to significant advancements in our understanding of misfolding-linked diseases82,83. Additionally, many disease-causing mutations operate at the ensemble level, where changes to the sequence result in abrogated populations of folds that can only be identified via an ensemble analysis76. Thus, it is important that work attempting to characterize RNA structure accounts for the highly heterogeneous nature of the biomolecule. Our work demonstrates that CryoEM can be used to generate sub-3Å RNA-only structures, provide information on RNA dynamics, and characterize low-population states in diMerent conditions, allowing one to visualize the remodeling of the configurational landscape under various conditions. With the continuing advances in data collection and processing rates, it may soon be possible to capture mid to high-resolution information on RNA folding pathways and misfolds. While huge advancements in protein fold prediction have occurred since the release of AlphaFold84, the RNA field has less high-resolution training data available, not to mention the significant impact buMer conditions have on RNA folding2. Collection of large cryoEM datasets may serve to address these challenges. The increasingly broad utilization of RNA within the fields of medicine and synthetic biology85,86 necessitates an improved understanding of RNA structure and dynamics.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1: Cryo-EM data processing scheme.

Data collection and processing procedures for the three glycine riboswitch datasets. From left to right: holo (2mM glycine, 10mM Mg2+), apo (no glycine, 10mM Mg2+), and neither glycine nor Mg2+.

Extended Data Fig. 2: Overall and local resolution estimation.

a Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) plot generate in cryoSPARC for the holo (left) and apo (right) glycine riboswitch structures. b Surface representations of the respective maps colored based on local resolution. c Expanded view of the boxed region in b, showing the density and model fit in the core region.

Extended Data Fig. 3: The P0 region of the glycine riboswitch adopts RNA suites consistent with a kink-turn conformation.

a Overlay of residues 4–8 in the holo glycine riboswitch structure with a transparent density map. Colors correspond to base identity. Suites for each sugar-to-sugar set of torsion angles are included. b Chemical view of each nucleotide and suite in the kink-turn.

Extended Data Fig. 4: The glycine riboswitch core is conserved in both sequence and structure.

a Normalized occupancy of each residue within the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch across all identified homologs. b Normalized conservation for each residue within the V. cholerae glycine riboswitch across all identified homologs. Normalized values were calculated with gaps included. Values from a,b were calculated using 11,626 glycine riboswitch sequences identified, and alignments made, in Torgerson et al. (2020)21. c RMSD calculated in ChimeraX44 using the F. nucleatum glycine riboswitch (PDB code: 3P49)23 and the V. cholerae structure solved here. Regions colored in black are absent in F. nucleatum.

Extended Data Fig. 5: Apt-II is stabilized by an additional G-C pair proximal to the glycine binding site.

Residues within 4 Å of the bound glycine are shown for both Apt-I (top) and Apt-II (bottom). Glycines are colored with carbons in grey and magnesium ions proximal to the binding site are shown and colored dark green. Nucleotides are colored according to base identity. Binding sites are largely identical, with the exception of the A70-U80 (Apt-I) to G177-C209 (Apt-II) change.

Extended Data Fig. 6: Glycines remain stable in our proposed configurations for Apt-I and Apt-II.

From unbiased and metadynamics simulations trajectories, several thousand frames representing the initial state conformations (Fig. 6) are extracted, and approximately one hundred conformations are depicted for glycine in each aptamer. Glycines maintain constant distance from the Mg2+ ions, with the carboxyl group facing to towards the Mg+2 ions and the amino group orientated towards the phosphate group of A68 and A175 in Apt-I and Apt-II, respectively, indicating our proposed glycine configurations are most stable.

Extended Data Fig. 7: Glycine conformations in metastable states seen in vicinity of modeled state.

a Free energy surfaces with respect to the Mg2+-glycine distance and glycine orientation for Apt-I (consistent with Fig. 6b). Five minima over the free energy surface, including a minimum representing the initial state of glycine modeled from the cryo-EM map, denoted as state I, are marked. b Conformation of glycine in minimum I, along with the neighboring residues, Mg2+ ions and cryo-EM-derived, low-pass filtered glycine density, are shown from two perspectives. c Similarly, glycine conformations in four additional minima are illustrated.

Extended Data Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and model statistics.

| CryoEM data collection and processing | holo glyRS – glycine and Mg2+ | glyRS – Mg2+ alone | glyRS - no ligand, no Mg2+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage (kV) | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 0.823 | 0.823 | 0.823 |

| Electron exposure (e-/Å2) | 59 | 59 | 59 |

| Defocus range | −0.6 to −2.4 | −0.6 to −2.4 | −0.6 to −2.4 |

| Final micrographs used | 5,338 | 5,819 | 4,312 |

| Particle images (10 models) | 384,275 | 725,637 | 430,437 |

| Particle images (final) | 215,269 | 207,411 | |

| Resolution (FSC threshold 0.143) | 2.86 Å | 3.27 Å | |

| Map sharpening B-factor (Å2) | −51.8 | −68.2 | |

| Refinement | |||

| Reference models | PDB: 6WLT, 3P49 | Holo glyRS | |

| Model composition | |||

| Atoms | 7477 | 7443 | |

| Protein residues | 2 | 0 | |

| RNA Residues | 230 | 230 | |

| Waters | 11 | 7 | |

| Mg2+ | 14 | 12 | |

| CCmask | 0.81 | 0.77 | |

| r.m.s deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.589 | 0.571 | |

| Clash score | 1.88 | 4.58 | |

| MolProbity score | 2.10 | 2.38 | |

| Pucker outliers | 0 | 0 |

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Sanbonmatsu and Joachim Frank laboratories for helpful discussions and critical reading of this manuscript. Further, we thank Robert Grassucci, Zhening Zhang, and Yen-Hong Kao for help with cryo-EM data collection. The electron microscopy data was collected at the Columbia University Cryo-Electron Microscopy Center, a node of the New York Structural Biology Center, supported by the NIH Common Fund Transformative High Resolution Cryo-Electron Microscopy program (U24 GM129539, and NIGMS R24 GM154192) and by grants from the Simons Foundation (SF349247) and NY State Assembly. Generous allocations of computational resources on the Chicoma supercomputer by Los Alamos National Laboratory Institutional Computing are gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to Trevor Glaros for providing laboratory space to conduct experiments. The work was generously supported by funding from NIH RO1-GM110310, US DOE LANL LDRD 20210082DR, US DOE LANL LDRD 20210134ER and the U.S. Department of Energy, OMice of Science, through the Biological and Environmental Research (BER) and the Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) programs under contract number 89233218CNA000001 to Los Alamos National Laboratory (Triad National Security, LLC).

Footnotes

Additional Declarations: There is NO Competing Interest.

Supplementary Files

Data availability

The cryo-EM density maps and model coordinates have been deposited in the EM Data Bank (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/) and the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) with accession codes EMD-48851, and 9N3I for the holo glycine riboswitch sample, and EMD-48852 and 9N3J for the Mg2+ alone sample. A previously published model Kappel et al, (2020) was used as a starting template (PDB code: 6WLT)35.

References

- 1.Simensen V. et al. Experimental determination of Escherichia coli biomass composition for constraint-based metabolic modeling. PLoS One 17, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider B. et al. When will RNA get its AlphaFold moment? Nucleic Acids Res 51, 9522–9532 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman H. M. et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 235 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershkovitz E., Sapiro G., Tannenbaum A. & Williams L. D. Statistical Analysis of RNA Backbone. IEEE/ACM transactions on computational biology and bioinformatics / IEEE, ACM 3, 33 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodson S. A. Compact intermediates in RNA folding: Annual Reviews in Biophysics. Annu Rev Biophys 39, 61 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prajapati J. D., Onuchic J. N. & Sanbonmatsu K. Y. Exploring the Energy Landscape of Riboswitches Using Collective Variables Based on Tertiary Contacts. J Mol Biol 434, 167788 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manz C. et al. Exploring the energy landscape of a SAM-I riboswitch. J Biol Phys 47, 371–386 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennelly S. P., Novikova I. V. & Sanbonmatsu K. Y. The expression platform and the aptamer: cooperativity between Mg2+ and ligand in the SAM-I riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 1922–1935 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musier-Forsyth K., Rein A. & Hu W. S. Transcription start site choice regulates HIV-1 RNA conformation and function. Curr Opin Struct Biol 88, (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fromm S. A. et al. The translating bacterial ribosome at 1.55 Å resolution generated by cryo-EM imaging services. Nature Communications 2023 14:1 14, 1–9 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S., Palo M. Z., Zhang X., Pintilie G. & Zhang K. Snapshots of the second-step self-splicing of Tetrahymena ribozyme revealed by cryo-EM. Nature Communications 2023 14:1 14, 1–10 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J. et al. Ensemble cryo-EM reveals conformational states of the nsp13 helicase in the SARS-CoV-2 helicase replication-transcription complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 29, 250–260 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheres S. H. W. et al. Disentangling conformational states of macromolecules in 3D-EM through likelihood optimization. Nat Methods 4, 27–29 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandal M. et al. A glycine-dependent riboswitch that uses cooperative binding to control gene expression. Science 306, 275–279 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhakal S. H., Panchapakesan S. S. S., Slattery P., Roth A. & Breaker R. R. Variants of the guanine riboswitch class exhibit altered ligand specificities for xanthine, guanine, or 20-deoxyguanosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119, e2120246119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuchs R. T., Grundy F. J. & Henkin T. M. The S(MK) box is a new SAM-binding RNA for translational regulation of SAM synthetase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13, 226–233 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkler W. C. & Breaker R. R. Genetic Control by Metabolite-Binding Riboswitches. ChemBioChem 4, 1024–1032 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrick J. E. & Breaker R. R. The distributions, mechanisms, and structures of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Genome Biol 8, 1–19 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crum M., Ram-Mohan N. & Meyer M. M. Regulatory context drives conservation of glycine riboswitch aptamers. PLoS Comput Biol 15, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherlock M. E. et al. Architectures and complex functions of tandem riboswitches. RNA Biol 19, 1059–1076 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torgerson C. D., Hiller D. A. & Strobel S. A. The asymmetry and cooperativity of tandem glycine riboswitch aptamers. RNA 26, 564–580 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon M. & Strobel S. A. Chemical basis of glycine riboswitch cooperativity. RNA 14, 25 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butler E. B., Xiong Y., Wang J. & Strobel S. A. Structural Basis of Cooperative Ligand Binding by the Glycine Riboswitch. Chem Biol 18, 293–298 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang L., Serganov A. & Patel D. J. Structural Insights into Ligand Recognition by a Sensing Domain of the Cooperative Glycine Riboswitch. Mol Cell 40, 774–786 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipfert J. et al. Structural transitions and thermodynamics of a glycine-dependent riboswitch from Vibrio cholerae. J Mol Biol 365, 1393–1406 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babina A. M., Lea N. E. & Meyer M. M. In vivo behavior of the tandem glycine riboswitch in Bacillus subtilis. mBio 8, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.RuM K. M. & Strobel S. A. Ligand binding by the tandem glycine riboswitch depends on aptamer dimerization but not double ligand occupancy. RNA 20, 1775 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman E. M., Esquiaqui J., Elsayed G. & Ye J. D. An energetically beneficial leader-linker interaction abolishes ligand-binding cooperativity in glycine riboswitches. RNA 18, 496–507 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kladwang W., Chou F. C. & Das R. Automated RNA structure prediction uncovers a kink-turn linker in double glycine riboswitches. J Am Chem Soc 134, 1404–1407 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crum M., Ram-Mohan N. & Meyer M. M. Regulatory context drives conservation of glycine riboswitch aptamers. PLoS Comput Biol 15, e1007564 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu V. B., Bai Y., Lipfert J., Herschlag D. & Doniach S. A repulsive field: advances in the electrostatics of the ion atmosphere. Curr Opin Chem Biol 12, 619–625 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Draper D. E., Grilley D. & Soto A. M. Ions and RNA folding. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 34, 221–243 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hennelly S. P., Novikova I. V. & Sanbonmatsu K. Y. The expression platform and the aptamer: cooperativity between Mg2+ and ligand in the SAM-I riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 1922 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipfert J., Sim A. Y. L., Herschlag D. & Doniach S. Dissecting electrostatic screening, specific ion binding, and ligand binding in an energetic model for glycine riboswitch folding. RNA 16, 708–719 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kappel K. et al. Accelerated cryo-EM-guided determination of three-dimensional RNA-only structures. Nature Methods 2020 17:7 17, 699–707 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy S., Hennelly S. P., Lammert H., Onuchic J. N. & Sanbonmatsu K. Y. Magnesium controls aptamer-expression platform switching in the SAM-I riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res 47, 3158–3170 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suloway C. et al. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J Struct Biol 151, 41–60 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Punjani A., Rubinstein J. L., Fleet D. J. & Brubaker M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nature Methods 2017 14:3 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Punjani A., Zhang H. & Fleet D. J. Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nature Methods 2020 17:12 17, 1214–1221 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Punjani A. & Fleet D. J. 3D variability analysis: Resolving continuous flexibility and discrete heterogeneity from single particle cryo-EM. J Struct Biol 213, 107702 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G. & Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Croll T. I. ISOLDE: A physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 519–530 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams P. D. et al. The Phenix software for automated determination of macromolecular structures. Methods 55, 94–106 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goddard T. D. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Science 27, 14–25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prajapati J. D., Onuchic J. N. & Sanbonmatsu K. Y. Exploring the Energy Landscape of Riboswitches Using Collective Variables Based on Tertiary Contacts. J Mol Biol 434, 167788 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zgarbová M. et al. Refinement of the Cornell et al. Nucleic Acids Force Field Based on Reference Quantum Chemical Calculations of Glycosidic Torsion Profiles. J Chem Theory Comput 7, 2886–2902 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian C. et al. Ff19SB: Amino-Acid-Specific Protein Backbone Parameters Trained against Quantum Mechanics Energy Surfaces in Solution. J Chem Theory Comput 16, 528–552 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mamatkulov S. & Schwierz N. Force fields for monovalent and divalent metal cations in TIP3P water based on thermodynamic and kinetic properties. J Chem Phys 148, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grotz K. K. & Schwierz N. Optimized Magnesium Force Field Parameters for Biomolecular Simulations with Accurate Solvation, Ion-Binding, and Water-Exchange Properties in SPC/E, TIP3P-fb, TIP4P/2005, TIP4P-Ew, and TIP4P-D. J Chem Theory Comput 18, 526–537 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Essmann U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys 103, 8577–8593 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H. J. C. & Fraaije J. G. E. M. LINCS: A Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulations. J Comput Chem 18, 14631472 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hess B., Kutzner C., van der Spoel D. & Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly EMicient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation. J Chem Theory Comput 4, 435–447 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tribello G. A., Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Camilloni C. & Bussi G. PLUMED 2: New feathers for an old bird. Comput Phys Commun 185, 604–613 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barducci A., Bussi G. & Parrinello M. Well-tempered metadynamics: A smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys Rev Lett 100, 020603 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raiteri P., Laio A., Gervasio F. L., Micheletti C. & Parrinello M. EMicient reconstruction of complex free energy landscapes by multiple walkers metadynamics. J Phys Chem B 110, 3533–3539 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prajapati J. D., Fernández Solano C. J., Winterhalter M. & Kleinekathöfer U. Characterization of Ciprofloxacin Permeation Pathways across the Porin OmpC Using Metadynamics and a String Method. J Chem Theory Comput 13, 4553–4566 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Golla V. K., Prajapati J. D., Joshi M. & Kleinekathöfer U. Exploration of Free Energy Surfaces Across a Membrane Channel Using Metadynamics and Umbrella Sampling. J Chem Theory Comput 16, 2751–2765 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tiwary P. & Parrinello M. A time-independent free energy estimator for metadynamics. J Phys Chem B 119, 736–742 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitford P. C. et al. An all-atom structure-based potential for proteins: Bridging minimal models with all-atom empirical forcefields. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 75, 430–441 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Der Spoel D. et al. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J Comput Chem 26, 1701–1718 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noel J. K. et al. SMOG 2: A Versatile Software Package for Generating Structure-Based Models. PLoS Comput Biol 12, e1004794 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ratje A. H. et al. Head swivel on the ribosome facilitates translocation by means of intra-subunit tRNA hybrid sites. Nature 468, 713–716 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Whitford P. C. et al. Excited states of ribosome translocation revealed through integrative molecular modeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 18943–18948 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim D. N. et al. Cryo_fit: Democratization of flexible fitting for cryo-EM. J Struct Biol 208, 1–6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Humphrey W., Dalke A. & Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph 14, 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pettersen E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Deng J. et al. RNA structure determination: From 2D to 3D. Fundamental Research 3, 727–737 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang H. W. & Wang J. W. How cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography complement each other. Protein Sci 26, 32 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng H. et al. CheckMyMetal: a macromolecular metal-binding validation tool. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 73, 223 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jain S., Richardson D. C. & Richardson J. S. Computational Methods for RNA Structure Validation and Improvement. Methods Enzymol 558, 181–212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Winkler W. C. Metabolic monitoring by bacterial mRNAs. Arch Microbiol 183, 151–159 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Winkler W. C. & Breaker R. R. Regulation of bacterial gene expression by riboswitches. Annu Rev Microbiol 59, 487–517 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yabukarski F. et al. Ensemble-function relationships to dissect mechanisms of enzyme catalysis. Sci Adv 8, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tesei G. et al. Conformational ensembles of the human intrinsically disordered proteome. Nature 626, 897–904 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bonilla S. L., Jones A. N. & Incarnato D. Structural and biophysical dissection of RNA conformational ensembles. Curr Opin Struct Biol 88, 102908 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ganser L. R., Kelly M. L., Herschlag D. & Al-Hashimi H. M. The roles of structural dynamics in the cellular functions of RNAs. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2019 20:8 20, 474–489 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Helmling C. et al. Life times of metastable states guide regulatory signaling in transcriptional riboswitches. Nature Communications 2018 9:1 9, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Helmling C. et al. NMR Structural Profiling of Transcriptional Intermediates Reveals Riboswitch Regulation by Metastable RNA Conformations. J Am Chem Soc 139, 2647–2656 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spitale R. C. & Incarnato D. Probing the dynamic RNA structurome and its functions. Nat Rev Genet 24, 178 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chauvier A. et al. Transcriptional pausing at the translation start site operates as a critical checkpoint for riboswitch regulation. Nature Communications 2016 8:1 8, 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tan Z. J. & Chen S. J. Ion-Mediated RNA Structural Collapse: EMect of Spatial Confinement. Biophys J 103, 827 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karamanos T. K., Kalverda A. P., Thompson G. S. & Radford S. E. Mechanisms of amyloid formation revealed by solution NMR. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 88–89, 86–104 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alderson T. R. & Kay L. E. Unveiling invisible protein states with NMR spectroscopy. Curr Opin Struct Biol 60, 39–49 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jumper J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McKeague M., Wong R. S. & Smolke C. D. Opportunities in the design and application of RNA for gene expression control. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 2987–2999 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Childs-Disney J. L. & Disney M. D. Approaches to Validate and Manipulate RNA Targets with Small Molecules in Cells. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 56, 123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The cryo-EM density maps and model coordinates have been deposited in the EM Data Bank (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/) and the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) with accession codes EMD-48851, and 9N3I for the holo glycine riboswitch sample, and EMD-48852 and 9N3J for the Mg2+ alone sample. A previously published model Kappel et al, (2020) was used as a starting template (PDB code: 6WLT)35.