Abstract

Self-assembly via non-covalent interactions is key to constructing complex architectures with advanced functionalities. A noncovalent synthetic chemistry approach, akin to organic chemistry, allows stepwise construction with enhanced control. Here, we explore this by coupling Pt(II) complex self-assembly with a redox reaction. Oxidation to Pt(IV) creates a non-emissive monomer that, upon reduction to Pt(II), forms luminescent gels with unique kinetic and thermodynamic pathways. UV irradiation induces Pt(IV) reduction, generating supramolecular fibers with Pt∙∙∙Pt interactions, enhancing photophysical properties and enabling visible light absorption up to 550 nm. This allows photoselective growth, where fibers convert surrounding Pt(IV) to Pt(II), promoting growth over nucleation, as observed via real-time fluorescence microscopy.

Subject terms: Molecular self-assembly, Photocatalysis, Self-assembly, Self-assembly

This study presents a strategy to form luminescent gels by chemically reducing non-emissive Pt(IV) complexes to emissive Pt(II). Additionally, UV light can induce Pt(IV) reduction, and the resulting fibers can be selectively elongated with visible light.

Introduction

Self-assembly through non-covalent intermolecular interactions is considered the path to achieving the highest level of matter complexity. Complexity is the key to unlocking advanced functions, characteristic of living systems, such as replication, evolution, and communication1–3. Several studies have shown that the outcome of the self-assembly process is determined by an interplay between thermodynamic and kinetic factors4, both of which can be exploited to achieve well-defined architectures. For instance, the cooperative process, which undergoes a nucleation/elongation mechanism, has been widely used to control the supramolecular polymers length5. Indeed, the growth of large aggregates in the elongation phase is thermodynamically more favorable than the formation of small oligomers in the nucleation phase6–9. Kinetic control, instead, is typically achieved by introducing competing off-pathways10. Examples of living supramolecular polymerizations have been realized by combining seed-induced growth with the ability to kinetically trap monomers into off-pathway aggregates11–13. Another strategy consists in inhibiting the spontaneous polymerization of monomers through the establishment of intramolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, which can be broken on demand or with tailored initiators14–16. The dynamic nature and weakness of non-covalent bonds allow for the adaptation in response to external or internal stimuli/effectors under equilibrium conditions. However, they make their manipulation difficult, limiting the field to the mixing of components in one assembly step. Very recently, Vantomme and Meijer17 have proposed a paradigm shift in the field suggesting that self-assembly must be turn into a noncovalent synthetic chemistry following a similar trajectory as organic chemistry, such as through the use of protecting groups and catalysts. In principle this would enable the stepwise construction of complex structures in a more reproducible manner as each assembly step can be physically characterized. A clever strategy in this direction consists in mixing covalent and noncovalent reactions steps so that the noncovalent synthetic products can be stabilized by, or can template, the covalent products thus enabling multistep synthesis18. Luminescent Pt(II) complexes have proven to be exceptional probes for investigating the complexity of supramolecular pathways, owing to the way their optical properties vary with molecular packing19–21. This behavior arises from the square-planar coordination geometry of the metal center, which readily facilitates both Pt∙∙∙Pt interactions and π-π stacking between chromophores, leading to a variety of polymorphic forms. Specifically, due to the dz² orbital interactions, new molecular orbitals are created, resulting in metal–metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MMLCT) states. The stronger the Pt∙∙∙Pt interaction (with distances in the range of 3.0–3.5 Å), the more bathochromically shifted the MMLCT band and emission become22–24. Among the various luminescent platinum complexes, those consisting of an N^N^N-type chromophore and a pyridinic ancillary ligand have proven to be particularly suitable as probes for self-assembly processes. This is due to their ability to change color from blue to red depending on molecular packing and the possibility to control solubility and the tendency to assemble in different solvents by modifying the functionalization of the ancillary pyridine. This enabled to monitor in real time, by fluorescence microscopy, a complex system with two kinetic assemblies (on-pathway) and their thermodynamic counterpart (off-pathway)12 as well as visualization of a supramolecular wrapping process25.

Result and discussion

For this study, we used compound 1, the simplest derivative of this class, to explore an approach different from previous ones, which is based on the change in coordination geometry from square planar Pt(II) to pseudo-octahedral Pt(IV). Indeed, the self-assembly tendency of the Pt(II) complex 1 to form luminescent fibers can be suppressed by oxidizing it with PhICl2 (see ESI), resulting in the formation of the corresponding pseudo-octahedral Pt(IV) complex 2 (see ESI S1-S6 for NMR characterization), which has two chloride ions coordinated in the axial positions (see Fig. 1) as confirmed by single crystal XRD (see ESI S7)26,27. A similar strategy was employed by Vilar et al. suppressing the tendency of interaction of the Pt(II) species with G-quadruplex DNA by oxidizing the complex to its Pt(IV) counterpart, and then triggering the interaction on demand with a reduction process28.

Fig. 1. Self-assembly pathway selection by photo or chemical reduction.

Reaction scheme, operating conditions of the redox process under analysis, and aggregation states achievable directly from compound 1 or through the reduction of compound 2.

The Pt(IV) complex 2 is a non-emissive species that exhibits better solubility than complex 1 due to its pseudo-octahedral geometry and absence of self-assembly behavior. This lack of aggregation is further confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, which shows that drop-casting a 10−3 M solution of complex 2 yields only tiny crystals or amorphous material (ESI S8). Consequently, complex 2 can be regarded as a ‘protected’ monomer, as its self-assembly process can only be initiated through a redox reaction that reverts it to complex 1.

When a solution of complex 2 in THF or ACN (2.6*10−2 M) is mixed with an equal volume of an aqueous solution of a reducing agent (5.2*10−2 M, 2 equivalents) such as sodium ascorbate (a), sodium dithionite (b), or glutathione (GSH) (c) luminescent gels, on-pathway aggregates (G1, G2) are formed. To facilitate the reading of spectra in figures and ESI, it is worth mentioning that the presence of the letter a–c in the legend indicates the presence of the excess of the reducing agent employed and its byproducts in the aggregated system. These reducing agents were selected for their mildness, low toxicity, ease of use, and potential applicability in biological settings. We do not exclude the possibility that many other mild reductants could also be used for this purpose.

The emission colors of these gels are primarily influenced by solvent polarity rather than the reducing agent used (see Table S1 and ESI S9-S24 for photophysical properties). The obtained gels remain stable to the inversion of the test tube (Fig. 1) for days post-synthesis. However, heating G1 to 70 °C (25 min), or sonicating it (5 min, T = RT, frequency of 40 KHz, power 120 W), irreversibly destroys the gel, with consequent loss of its mechanical properties, and producing the thermodynamic, on-pathway, product D1 (Fig. 1). The disruption process of G1 is captured in Supplementary Movie 1, where a vial containing a freshly prepared G1 sample is heated with a heat gun under UV irradiation (365 nm). Initially, G1 exhibits a uniform yellow photoluminescence across the sample. As heating begins, water separates from THF, partially solubilizing the aggregates of 1. Continued heating induces the first conversion of the insoluble aggregates into their thermodynamic state. Upon returning to room temperature, the aggregates elongate in the blue-green emitting thermodynamic state, while the solvent phases become miscible again. However, fiber elongation is too slow to encapsulate the solvent, ultimately leading to gel disruption and the formation of a mixture of aggregates identified as D1. D1 consists in a dispersion of blue-green emissive fibers (λem,max = 497 nm), indicating weaker metallophilic interactions similar to previously reported systems12. Interestingly, G2 retains its properties indefinitely when heated to 70 °C. However, allowing G2 to sit at room temperature for 2 weeks after sonication results in the formation of D2, as confirmed by absorption and emission spectra (Figs. 2a, b and S25–S28 for photophysical properties). The transformation of the kinetic product into the thermodynamic one can also be observed in real time by fluorescence microscopy (Supplementary Movie 2). Thus, by combining preformed fibers in kinetic and thermodynamic state in a THF/H2O mixture (1:1), and taking a snapshot every 5 min, it is observed the gradual conversion of the orange fibers into the blue-green ones over a 2 h 30 min period. The latest do not show further conversion and are stable up to several months.

Fig. 2. Photophysical properties of gels and disrupted gels.

a Normalized UV-Vis of G1,2 (up) and D1,2 (down). b Normalized emission spectrum of G1,2 (up) and D1,2 (down). Concentration of samples for both a and b: 2.6*10−2 M in THF (blue line) and ACN (orange line). c Fluorescence microscope pictures of aggregates derived from a drop cast of G2 (up), and D2 (down) at λ = 385 nm of irradiation.

Further experiments were conducted to better understand the conditions governing the gelation process and the nature of the thermodynamic state in which the aggregates form. The emission spectra of the various species are presented in Figs. S29 and S30, with corresponding PLQY values listed in the caption.

The influence of different parameters was tested, including the concentration and volume of sodium ascorbate (5.2 × 10-³ M, 1 mL aqueous), the stoichiometry of 2/ascorbate (ratios of 5:1 and 1:5, with the concentration of 2 of 2.6*10−2 M), and the speed of reductant addition (1 drop per second), in both THF and ACN organic solvents. In all tests, except for the 2/ascorbate ratio of 1:5, a dispersion of aggregates was obtained with an emission spectrum similar to that of G1 and G2. The most significant variation was observed with the addition of diluted reductant in THF, where the emission spectrum exhibited a notable red shift to 595 nm (Δλemi,max = 24 nm), nearly matching the spectrum obtained with ACN as the organic solvent. When the ratio 2/ascorbate used is 1:5, a gel similar to G1 and G2 is obtained although characterized by lower PLQY.

To investigate the processes leading to the formation of these assemblies, we conducted thermodynamic studies on a 10−4 M solution of complex 1 in THF/H2O (40%) and ACN/H2O (50%) (see ESI S31, S32 and Table S2). These specific solvent ratios were selected to enable both the dissolved molecular state and the fully aggregated form to coexist within a temperature range compatible with the limitations of the Peltier device. Thermodynamic control was ensured by recording multiple spectra at the same temperature until no further changes were observed. Since aggregates formed during the cooling process tend to precipitate, potentially distorting absorbance values, the absolute change in absorbance (∣ΔAbs∣) at 250 nm across various temperatures was used for analysis. Thermodynamic parameters calculated using the Eikelder-Markvoort-Meijer model29 revealed a cooperative nucleation-elongation mechanism in both solvent systems30. The nucleation penalties (ΔHnucl0) were determined to be −18.5 kJ/mol for THF and −20.5 kJ/mol for ACN, while the elongation enthalpies (ΔHel0) were −110.0 kJ/mol and −98.9 kJ/mol, respectively. Surprisingly, in both cases the dispersed fibers formed upon cooling correspond to on-pathway aggregates G1,2 as confirmed by their emission spectra (see ESI S33, S34). This result, along with the thermal transformation of G1 into D1, suggests that D1 may form through a consecutive aggregation pathway, originating from the aggregation of G1 rather than directly from the monomer.10,31 To unravel the thermodynamic properties of D1, a set of fibers obtained by the thermal transformation of G1 in D1 is washed thoroughly with water to ensure the complete removal of any trace of reducing agent and byproducts from the sample. Then, a dispersion of D1 at 10−4 M concentration in a 40/60 THF/H2O is used to perform a heating curve (see ESI S35, Table S3). A tentative fit of the resulting curve gave an elongation enthalpy (ΔHel0) of −180 ± 48 kJ/mol. The very high standard deviation values (see Table S3) obtained for all the thermodynamic parameters do not allow to unambiguously confirm the aggregation mechanism. Unfortunately, the solubility of the aggregates obtained from D1 is poor enough to not allow the heating curve to be performed in ACN. We then turned to the evaluation of the electronic properties of the Pt complex and its aggregates by computations (details on the computational models used can be found in ESI, general section). Whereas the assessment of electronic properties resulting from metallophilic interactions should be performed with caution, we investigated the electronic properties of plausible Pt(II) dimers both in their singlet ground (S0) and first excited triplet (T1) states and compared the computational results with the observed spectroscopic behavior. We note that the solvent effects may contribute to the stabilization of the aggregates as observed for THF or ACN, however the explicit treatment of solvent effects is out of the computational scope, therefore all the calculations were carried in the gas phase. First, we calculated the absorption and emission properties of complex 1 from its S0 and T1 state respectively. Details of the computational method used for the calculation is reported in the experimental part. Time-dependent DFT calculations including spin-orbit effects (SOC TD-DFT) predicts for monomer complex 1 a S0 → T1 transition (λabs = 455 nm; fosc = 0.003) and a S0 → S1 transition (λ = 417 nm; fosc = 0.044) in good agreement with the experimental observations (Fig. S36, vide infra for photophysical characterization of the various species under analysis in this work). Next, we turned our attention to the aggregation properties of complex 1. Although the exact structure of the aggregates here discussed is unknow, we recently reported25 the solid-state structure of an analog Pt(II) complex in two polymorphs. Therefore, we modeled the structures of the aggregates of complex 1 based on the reported structural parameters. Two dimers of complex 1 with different Pt–Pt distances were optimized in their S0 geometry, namely dimer 1-A (Pt–Pt distance = 3.231 Å, Fig. ESI 37a) and 1-B (Pt–Pt distance = 3.698 Å, Fig. ESI 37b). DFT calculations predict the aggregation of two complex 1 to form dimer 1-A to be thermodynamically favored with ΔΔG = −20 kJ mol−1 which is surprisingly close to the nucleation enthalpy determined by thermodynamic experiments. We note that the aggregation of two molecules of complex 1 is energetically favored (ΔΔG = −20 kJ mol−1); while the formation of dimer 1-B is not (ΔΔG = +1 kJ mol−1). This value is also within the margin of uncertainty of the calculation of the ΔHnucl0 of aggregates obtained from D1 during the heating curve experiment (see ESI S35, Table 3). Hence, we speculate that short Pt–Pt distance in dimer 1-A stabilize the aggregate. The effects of the metallophilic interactions are also noted in the predicted spectroscopic properties of the dimers. SOC TD-DFT predicts for dimer 1-A a S0 → T1 transition (λabs = 469 nm; fosc = 0.055) and a S0 → S1 transition (λabs = 415 nm; fosc = 0.016), and for dimer 1-B a S0 → T1 transition (λabs = 465 nm; fosc = 0.0006) and a S0 → S1 transition (λabs = 427 nm; fosc = 0.043). Next, we compute the electronic properties of the dimers 1-A and 1-B in their optimized T1 geometries; in the T1 state the Pt–Pt distance of 1-A is predicted to shorten to 3.153 Å (Fig. ESI 37c); while in the T1 state the Pt–Pt distance of 1-B is predicted to increase to 3.940 Å (Fig. ESI 37d). The shortening of the Pt–Pt distance in the T1 state of dimer 1-A affect the emissive properties of the dimer, SOC TD-DFT calculations predict a bathochromic shift of the emission (λem = 579 nm; fosc = 0.0008) respect to dimer 1-B monomer complex 1 (λem = 546 nm; fosc = 0.0001 and λem = 541 nm; fosc = 0.0004 respectively for dimer 1-B and monomer complex 1). Based on these computational results, we speculate that the energetically favored dimer 1-A characterized by short Pt–Pt, both in the S0 and T1 states, is a good approximation of the G aggregate, for which we found a bathochromic shift of the emission (λem of 571 nm for G1 and 594 nm for G2) and stability. Whereas dimer 1-B represent a metastable form, which does not differentiate spectroscopically from the monomer, we suggest dimer 1-B as an approximation to the D aggregate, also characterized by the weaker of metallophilic interactions than 1-A32.

SEM analysis reveals that gel G1 (see ESI S38–S39) consists of lightly curved fibers of complex 1 that intersect to form a network of wires, with thicknesses ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometers. These fibers are coated with a thick layer of amorphous material composed of complex 2, the reducing agent, and byproducts. The composition of the fibers and the amorphous material was determined through EDX analysis, which provided elemental identification. The fibers, containing Pt but not Cl, were confirmed to be made of complex 1, while the simultaneous presence of Pt and Cl identified the amorphous material as containing complex 2. In contrast, gel G2 (see ESI S40) comprises thicker rods (hundreds of nanometers) coated with a thinner layer of amorphous material. Upon transformation into their thermodynamically stable forms (D1 or D2), the lightly curved fibers of G1 and G2 evolve into straight rods with thicknesses reaching up to 2 μm (see ESI S41–S42).

Attempts to obtain gels starting directly from the Pt(II) species failed due to the insolubility of complex 1, which does not dissolve even after thermal treatment or sonication. Solvents tested in these experiments include toluene, THF, acetone, DMF, DMSO, and ACN. Thus, using conventional methods such as varying temperature, concentration, and solvent/non-solvent ratios resulted in the precipitation of complex 1 as an amorphous powder. To check if the presence of the reducing agents or their byproduct plays a role in the gelation process, samples of gels obtained from the reducing agent a, b and c, are dried under vacuum and the attempt of gelation using thermal methods with THF and ACN is repeated, but no gelation is observed. These observations suggest that the gel is a metastable kinetic state accessible exclusively through the in situ chemical reduction of complex 2.

Photoreduction

The UV-Vis absorption spectrum of the Pt(II) complex 1 (see ESI S36) features an intense band in the UV region, primarily attributed to intraligand (1IL) and metal-perturbed interligand charge transfer (1ILCT) states. Additionally, a broad band between 350–450 nm is ascribed to a mixture of spin-allowed metal-to-ligand charge transfer (1MLCT) and intraligand (1IL) transitions, as commonly observed in this class of compounds33,34. In contrast, the absorption spectrum of complex 2 (see ESI S43) in dilute solution (10−4 M, ACN) shows intense absorptions in the 250–350 nm range, attributed to 1IL and 1ILCT transitions, while 1MLCT absorptions are presumed to be at very high energies and are thus obscured by the ligand-centered transitions, consistent with observations in other Pt(IV) complexes35. Interestingly, irradiating a dilute solution of complex 2 (10−4 M in ACN) with a deuterium lamp results in the reductive photodissociation of the chloride ligands, forming complex 1, phenomenon already observed by Sharp et al.36 on Pt(IV)Cl2 substrates37,38. This transformation is followed by UV-Vis absorption spectra (see ESI S44), and the identity of the species is verified by NMR spectroscopy on an intermediate point of the photoreaction (see ESI S45, 75% conversion). When this photoconversion is performed in the same medium and concentration where gels G1 and G2 are chemically formed, no gelation occurs; instead, the growth of luminescent fibers is observed (see ESI S46–S50 for photophysical characterization). In this case, the gelation does not take place because of the very slow rate of conversion compared with the chemical reduction, which does not allow for the embedding of the solvent. SEM analysis of the aggregates formed by photoreduction reveals a network of lightly curved wires, similar to those obtained with G1 and G2 (see ESI S51–S52). The self-assembly process triggered by photoreduction can be monitored by fluorescence microscopy, as shown in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Movie 3. After approximately 1 min of irradiation, a bundle of fibers is generated only in the irradiated spot (Fig. 3b), allowing for the creation of patterns. For instance, a circle can be drawn on a thin layer of a 2.6*10−2 M solution of complex 2, deposited between two quartz plates, using a deuterium lamp equipped with a beam-shaping mask (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Photoreduction of Pt(IV) species observed via fluorescence microscopy.

a Snapshot of Supplementary Movie 2; photoreduction of 2 at 10−3 M in ACN/H2O (2:1 ratio); light irradiation at λ = 385 nm, magnification ×20. b Snapshot of a spot previously irradiated at 385 nm (×10 magnification, λ = 555 nm). c Circle drawn with a deuterium lamp equipped with a beam-shaping mask using a solution 2 in THF/H2O (1:1 ratio) at 2.6*10−2 M concentration.

Photoselection

Light-triggered self-assembly processes typically exploit the inherent properties of photoactive components such as azobenzenes39–42, spiropyrans43, diarylethenes44–47, triarylamines48,49 or the cis-trans isomerization of imines50,51 or overcrowded alkene52 to cite some that are either combined with or covalently functionalized by other self-assembling motifs. In this case, as partially anticipated, the establishment of ground state Pt∙∙∙Pt metallophilic interactions causes a dramatic change in the photophysical properties of the assemblies destabilizing the HOMO resulting in a bathochromic shift of both absorption and emission spectra53. This peculiar characteristic of such class of compounds makes the assembled structures better light harvesters compared to the monomeric unit, enabling the fibers to absorb light up to approximately 550 nm. Conversely, the monomer complex 1 cannot absorb light with λ > 450 nm, and complex 2 exhibits the most hypsochromic shift with absorption bands only in the UV region with an absorption onset at 400 nm (Fig. 4a). This provides a basis for the photoselective elongation (Fig. 4): by mixing assembled fibers with a fresh solution of complex 2 and irradiating at λ = 555 nm, where only the supramolecular fibers absorb light (Fig. 4c). The reduction of complex 2 can occur solely through photoinduced electron transfer (PET), a phenomenon common also to other Pt(II)(NNN) complexes54,55. In this setup, the aggregated form would synthesize its own monomer 1, promoting the growth of the assembly rather than formation new nuclei, as monomer 1 would be generated only in the immediate vicinity of the existing fibers.

Fig. 4. Selective elongation of Pt(II) fibers.

a Pathway scheme of the selective elongation of Pt(II) fibers under visible light irradiation (λ = 555 nm). Dispersion of aggregates drop casted into a 10−3 M solution of 2 in a 2:1 ACN/H2O solvent system. b UV-Vis spectrum of 2 in ACN at 10−4 M concentration, onset at λ = 400 nm. c Excitation spectrum of aggregated form of 1 obtained by photoreduction of 2 at 10−3 M concentration in ACN/H2O 1:1, onset at λ = 550 nm.

A dispersion of aggregates obtained by photoreduction (20 μL, starting from a 10−3 M solution in ACN/H2O 2:1) is added to a solution of 2 (1 mL, same solvent, and concentration), then, 20 μL of the obtained mixture are deposited on a quartz plate. A group of two fibers is isolated and irradiated at 555 nm under fluorescent microscope. The results are shown in Supplementary Movie 4 and Fig. 4a. In the initial minutes, we observe an increase in the thickness and emission intensity of the fibers, followed by rapid elongation. Unlike in Supplementary Movie 3, no new fibers appear; instead, the two original fibers simply grow longer. Repeating the experiment in a 1 mm quartz cuvette under identical solvent mixture at 2*10−3 M concentration, the depletion of complex 2 was monitored using UV-Vis analysis (Fig. 5a). In the first phase of the experiment, the sample was irradiated with green light (see Methods section for details) for 30 min, during which no depletion of complex 2 was observed. This result further supports the inertness of complex 2 toward green light irradiation. Subsequently, the sample was irradiated with UV light for 3 min, resulting in a detectable depletion of complex 2. During this time, a portion of complex 2 was converted into fibers of complex 1, which are capable of absorbing green light. When the resulting aggregates were irradiated again with green light in the presence of the remaining solution of complex 2, the signal corresponding to complex 2 gradually decreased over time.

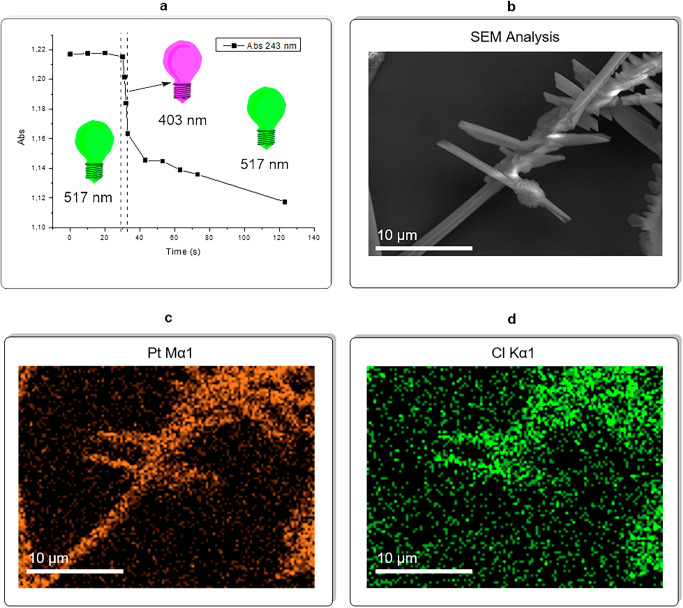

Fig. 5. Quantitative analysis and EDX of Pt(II) fibers selective elongation.

a Quantitative analysis of selective elongation of Pt(II) aggregates via UV–Vis monitoring the Pt(IV) depletion over irradiation with UV light (λ = 403 nm) and green light (λ = 517 nm); initial condition: compound 2 at 2*10−3 M concentration in a 2:1 ACN/H2O solvent mixture (1 mm cuvette). b SEM analysis of the Pt(II) fibers and residual Pt(IV) mixture obtained at the end of the second run of the selective aggregates elongation experiment (1 cm cuvette, same solvent and initial concentration as picture a). c EDX mapping of Pt in the same spot of the SEM analysis. d EDX mapping of Cl in the same spot of the SEM analysis.

In a follow-up experiment conducted in a 1 cm quartz cuvette, samples of the aggregates were collected after their formation under UV light and after their elongation process under green light irradiation. SEM analysis of these samples (see ESI S53 and S54 as representative starting point of selective elongation of fibers; ESI S55, S56 for the end point) revealed that the fibers increased in both thickness and length during the elongation process. Additionally, images taken after elongation (see ESI S55, S56) showed structures resembling secondary nucleation. However, EDX confirmed that the fibers lacked Cl-related peaks, indicating that they were composed of complex 1. In contrast, the crystals, which appeared similar to secondary nucleation, exhibited clear Cl peaks, identifying them as being made of complex 2 (see ESI S57, S58, Table S4). Additionally, EDX mapping Pt and Cl atoms is conducted on a spot of the sample as an additional proof of the nature of the objects observed (Fig. 5b–d). The kinetics of this elongation process can be explained by the deposition of Pt(II) on the surface of the fibers. As the fibers grow, the conversion of Pt(IV) to Pt(II) increases, accelerating the elongation process. The establishment of Pt∙∙∙Pt metallophilic interactions and the geometric transformation from Pt(IV) to Pt(II) are central to this study. These findings could be extended to redox-active organic molecules with aggregation-induced emission (AIE) or those capable of forming H- or J-aggregates, opening new avenues for precision macromolecular engineering.

Methods

General

All the reactions were carried out under an inert atmosphere of argon (Schlenk technique). All the solvents and chemicals were used as received from Aldrich or Fluka without any further purification. The compounds were purified by column chromatography by using either silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh) or neutral alumina as stationary phase. 1H, and 13C{1H} spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer equipped with a BBO probe, while 19F{1H} NMR were recorded with a Bruker 200 MHz equipped with a QNP probe. 1H, and 13C chemical shifts were referenced relative to residual solvents peaks while 19F chemical shifts were referenced using indirect referencing56. The 1H NMR chemical shifts (δ) are given in ppm and referred to residual protons on the corresponding deuterated solvent. All coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz (Hz). All deuterated solvents were used as received without any further purification. HR-MS spectra were recorded on a Thermo Q-Exactive™ equipped with an ESI source. Mass spectra were recorded in positive mode. Elemental analyses were recorded by the analytical service of physical measurements and optical spectroscopy at the University of Strasbourg.

Synthesis of [Pt(Cl)2(DMSO)2]

This compound is synthesized accordingly with a modified literature procedure12. An aqueous solution of K2PtCl4 (1.24 g, 3 mmol in 10 mL) is filtered into a 50 mL beaker through paper. This procedure removes impurities due to metallic Pt and/or K2PtCl6. DMSO (0.64 mL, 9 mmol) is added to this solution, and, after a gentle hand mixing, the solution is left to stand at room temperature until complete precipitation of yellow needles (36 h). The precipitate is filtered, washed 3 times with 10 mL of water, ethanol, and diethyl ether, and dried in vacuo for 4 h. The yield is 1.10 g (87%).

Synthesis of pyridine-2,6-bis(carboximidhydrazide)

This compound is synthesized accordingly with a literature procedure12. In a 500 mL round bottom flask 2,6-pyridinedicarbonitrile (10.0 g, 77.45 mmol) was dissolved in 200 mL of ethanol then 80 mL of hydrazine monohydrate were added, and the flask closed with a rub septum. The resulting solution was stirred for 3 days at room temperature. The solution was then filtered and the slightly yellowish solid washed with ethanol (50 mL) and dried. The compound was used without further purification. Yield 14.6 g (97.5%).

Synthesis of 2,6-bis(3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)pyridine (L1-2H)

This compound is synthesized accordingly with a literature procedure12. Pyridine-2,6-bis(carboximidhydrazide) (2.28 g, 11.8 mmol) was suspended in 25 mL of diethylene glycol dimethyl ether and sonicated until a fine white suspension was formed. Trifluoroacetic anhydride (3.6 mL, 26 mmol) was slowly added to the mixture at room temperature. Upon addition, the suspension dissolves and the solution turns yellow in color. The solution was stirred for 10 min at room temperature then slowly heated up using a silicon oil bath until reflux. The progress of the reaction was followed by TLC using acetone as the eluent and was complete within 1 h from reflux. After cooling down to room temperature, 70 mL of distilled water followed by 2 mL of concentrated HCl were added and the mixture overnight heated at 90 °C. The solution was then cooled down to room temperature and stirred for additional 2 h. The white precipitate was filtered and abundantly washed with water and petroleum ether, then dried overnight at 70 °C. The compound was used without further purification. Yield (3.0 g, 74.5%).

1H NMR (acetone-d6, 400 MHz, ppm): δ = 8.33–8.40 (m); 13C{1H} NMR (acetone-d6, 100 MHz, ppm): δ = 156.42 (s), 156.04–154.88 (q, J = 39 Hz), 146.05 (s), 141.36 (s), 124.55–116.53 (q, J = 268 Hz), 123.82 (s). 19F{1H} NMR (acetone-d6, 376 MHz, ppm): δ = 65.80 (s, CF3). HR-ESI-MS (m/z): C11H5F6N7Na [M + Na] +, calcd. 372.040, found 372.035.

Synthesis of [Pt(II)(L1)(py)] (1)

Complex 1 is synthesized via a modified literature procedure57. [PtCl2(DMSO)2] (100.0 mg, 0.2368 mmol) and 1.0 eq. of L1-2H (82.7 mg, 0.2368 mmol) are suspended, under Ar atmosphere, in 20 mL of ACN, followed by the addition of 2.0 eq of DIPEA (61.2 mg, 0.4736 mmol, 82.6 μL). The initial heterogeneous slurry quickly turns into a yellow solution that is left under stirring at RT for 10 min. Afterwards, 1.3 eq. of pyridine (24.3 mg, 0.3078 mmol, 24.8 μL) are added to the solution, and an orange precipitate starts forming. The heterogeneous orange mixture is stirred at 70 °C overnight turning into a bright yellow suspension. The filtration of the solid, followed by washing with cold ACN and n-hexane, afford the product as a yellow powder which is then dried under vacuum overnight. Yield 73% (107.4 mg 0.1729 mmol). The full NMR characterization can be found in the original paper57. The 1H NMR in CDCl3 is reported below for sake of comparation with compound 2.

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ = 9.74 (dd, 3JHH = 6.6, Hz 4JHH = 1.3 Hz, satellites 3JHPt = 13.2 Hz, 2H; ortho py), 8.14 (pseudo t, 3JHH = 7.6 Hz, 1H; para pyL1), 8.08 (dd, 3JHH = 8.4 Hz, 3JHH = 7.5 Hz 1H; para py), 7.89 (d, 3JHH = 7.9 Hz, 2H; meta pyL1), 7.70 (dd, 3JHH = 7.7 Hz, 3JHH = 6.5 Hz 2H; meta py). 1H NMR (400 MHz, THF-d8) δ = 9.7223 (d, J = 5.8, 2H), 8.2372 (q, J = 8.2, 2H), 7.89 (d, J = 7.8, 2H), 7.76 (t, J = 6.7, 2H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, THF-d8) δ = 154.65, 150.03, 145.04, 141.31, 127.68, 119.46 ppm. 19F{1H} NMR (377 MHz, THF-d8) δ = −65.61 (s) ppm. HR-ESI-ToF-MS (positive scan, m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. 622.0491; found 622.0481.

Synthesis of [Pt(IV)(Cl)2(L1)(py)] (2)

[Pt(II)(L1)(py)] (1) (100 mg, 0.1609 mmol) and 2 eq. of PhICl2 (88.5 mg, 0.3219 mmol) are suspended in 5 mL of EtOAc and stirred at T = 70 °C for 1 h. The initial bright yellow suspension turns into a homogeneous pale-yellow solution. After the addition of 5 mL of hexane, the reaction mixture is filtered through a short silica pad using a 1:1 mixture of EtOAc/hexane as eluent. The product is dried under vacuum at 40 °C for 4 h to yield 74.6 mg (0.1078 mmol) of a pale-yellow powder. Yield 67%.

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ (ppm) = 9.59 (dd, 3JHH = 6.8 Hz, 4JHH = 1.4 Hz, satellites 3JHPt = 11.8 Hz, 2H; ortho py), 8.39 (dd, 3JHH = 8.6 Hz, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 1H; para pyL1), 8.33–8.19 (m, 3H; para py and meta pyL1), 7.91–7.81 (m, 2H; meta py). 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ = 160.5 (s; ipso triazole), 153.6 (q, 2JCF = 39.7 Hz; ipso pyL1), 152.6 (s; ortho py), 146.2 (s, satellites 2JCPt = 2.8 Hz; ipso pyL1), 145.5 (s; para pyL1), 142.1 (s; para py), 127.6 (s, satellites 3JCPt = 12.8 Hz; meta py), 121.0 (s, satellites 3JCPt = 8.4 Hz; meta pyL1), 119.2 (q, 1JCF = 272.1 Hz, CF3). 19F{1H} NMR (188 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ = −64.8 (s, 6F; CF3). Elemental analysis cald. (%) for C16H8Cl2F6N8Pt: C 27.76, H 1.16, N 16.19; found: C 28.55, H 1.64, N 16.17. micrOTOF m/z [M + H]+ calcd. 691.9874; found 691.9976.

General procedure for gel formation G1,2

A solution 2.6*10−2 M of 2 is made in organic solvent (THF or ACN), and an equal volume of water solution of 2 eq. of reducing agent (sodium ascorbate (a), sodium dithionite (b), GSH (c)) is quickly added. The gel formation occurs within seconds, and it is stable-to-inversion of a test tube.

Computational analysis

All calculations were performed with ORCA v 6.0.158. Molecular geometries were optimized without any symmetry constrain in the gas phase using the BP86 functional. Scalar relativistic effects were modeled using the Zeroth Order Regular Approximation (ZORA)59 with the ZORA-Def2-SVP basis set60 and the SARC-ZORA-TZVP61 for platinum with the RI62 approximations and the related auxiliary basis sets (SARC/J)63,64. The D3 dispersion correction65 with Becke-Johnson damping66 was used. All optimized structures were verified as true minima by the absence (Nimag = 0) of negative eigenvalues in the harmonic vibrational frequency analysis. Time-dependent DFT calculations including spin-orbit effects (SOC TD-DFT) calculations were performed in the gas phase using the PBE0 functional67. Scalar relativistic effects were modeled using ZORA with the ZORA-Def2-TZVP basis set60 and the SARC-ZORA-TZVPP61 for platinum with the RI-SOMF(1X) approximations68 with the related auxiliary basis sets (SARC/J). For the TD-DFT calculations 25 roots were computed including both singlet and triplets SOC effects (DOSOC = true) and the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA = true) to speed up the calculations. Structures were visualized with Chemcraft (https://www.chemcraftprog.com). Further information on the computational level of the theory and the xyz coordinates are reported in the supporting information.

Photoreduction and fluorescence microscopy

The photoreduction kinetic of 2 is made on a quartz cuvette with 2 at 10−4 M concentration in ACN and irradiation with a deuterium lamp (AvaLight-DH-S; Wavelength Range UV 175–400 nm, Vis 360–2500 nm, Lamp Power UV 78 W/0.75 A, Vis 5 W/0.5 A). The cuvette is irradiated for fixed amount of time and the conversion is analyzed via UV-Vis. The sample is kept in the dark between the irradiation and the analysis. The same equipment and settings are applied to a 2.6*10−2 M solution of 2 (THF/H2O 1:1) obtaining aggregates of 1.

The photoreduction is observed via fluorescence microscopy (Axio Observer 7) using 20 μL of a solution of 2 at 10−3 M in ACN/H2O 2:1 deposited on a coverslip and covered with a quartz petri dish (Hamamatsu) to prevent solvent evaporation. The sample is irradiated at λ = 385 nm (Light Source Colibri 5 Type RGB-UV; Wavelength Range: UV 385 ± 15 nm, blue 469 ± 19 nm, green 555 ± 15 nm, 631 ± 16.5 nm).

A thin layer of a 2.6*10−2 M solution of 2 (THF/H2O 1:1) is deposited between two quartz slits and irradiated with a deuterium lamp equipped with a circular beam-shape mask. The reduction of 2 to 1 occurs within 15 min of irradiation.

Photoselective elongation

Fibers of 1 obtained by photoreduction of 2 are dispersed into 20 μL of a 10−3 M solution of 2 in ACN/H2O 2:1 and irradiated at λ = 555 nm (Light Source Colibri 5 Type RGB-UV; Wavelength Range/Bandwidth: UV 385/30 nm, blue 469/38 nm, green 555/30 nm, 631/37 nm).

The UV-Vis analysis of the selective elongation of the fibers is made by using a 1 cm quartz cuvette containing a solution of 2 at 10−4 M concentration in ACN/H2O 2:1 and irradiating it for determined period of time with green or UV light with a “Stage light; model ZQ01137” (Wavelength Range/Bandwidth: green light 517/140 nm, UV light 403/120 nm).

Preparation of samples

Samples for photophysical measurements in solution are obtained by dissolution of 3.1 mg (0.005 mmol) of complex 1, or 3.4 mg (0.005 mmol) of 2, in 50 mL volumetric flask and then diluted to a final concentration of 10−4 M, using THF, or ACN as solvent.

Samples for photophysical measurements of gels are obtained by direct deposition of 20 μL of organic solvent containing the Pt (IV) complex at 2.6*10−2 M concentration, and an equal volume of the desired reducing agent at 5.2*10−2 M concentration, directly on the plate cuvette. Samples for integrating sphere were obtained by abstraction with a spatula from a preformed gel.

Samples for SEM analysis were prepared accordingly with photophysical measurements procedures using a silicon fragment as support.

Temperature-dependent absorption spectra (cooling curve)

A solution 10−4 M of 1 in a mixture THF/H2O 40%, or ACN/H2O 50% into a 1 cm quartz cuvette and analyzed via UV-Vis equipped with a Peltier temperature regulator. The initially heterogeneous mixture was heated to 313 K when THF was used as organic solvent, 333 K with ACN. Then, the UV-Vis spectrum was registered at various temperature under thermodynamic control: 15 min of equilibration time with another spectrum acquired after 5 min until the analysis are superimposable. Cooling rate with THF/H2O 40% mixture: 2 K every 15–30 min of equilibration time. Cooling rate with ACN/H2O 50%: 2 K every 15–30 min of equilibration time until 318 K, then 1 K per step until 333 K. Minimum temperature for THF/H2O 40% = 285 K, and for ACN/H2O 50% = 300 K.

A dispersion of aggregates obtained from D1, after having been washed with plenty of water to remove any traces of reducing agent or byproducts, at 10−4 M concentration in a mixture THF/H2O 40%, was transferred into a 1 cm quartz cuvette and analyzed via UV-Vis equipped with a Peltier temperature regulator. The initial temperature of the experiment is 288 K. The sample was analyzed via UV-Vis, then the temperature was raised of 4 K at a time stirring the solution for 1 min before leaving the system to equilibrate for another 15 min and repeating the acquisition every 5 min until two consecutive spectra are superimposable between 288 and 298 K, then 2 K per step until 327 K. Maximum temperature 327 K.

The data analysis was made via Eikelder–Markvoort–Meijer model29.

Photophysical measurements

Absorption spectra were recorded, and baseline corrected, with a Varian Cary 100bio UV-VIS spectrophotometer in 10 mm quartz cuvettes filled with non-degassed solution of investigated compounds. Emission and excitation spectra were recorded with a Photoluminescence Spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments, FLS1000) equipped with a 450 W Xe lamp and an air-cooled single-photon counting photomultiplier (Hamamatsu R13456). The gel samples were directly formed onto a quartz plate cuvette, while 1 and 2 solutions were analyzed in a 10 mm quartz cuvette. Emission and excitation spectra were corrected for source intensity (lamp and grating) and emission spectral response (detector and grating) by standard correction curves. The absolute photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY) were measured on a Hamamatsu Absolute PL quantum yield spectrometer C11347 Quantaurus QY integrating sphere in air-equilibrated condition using an empty quartz Petri dish as a reference. Lifetimes were obtained on a FLS1000 in a quartz plate cuvette in air equilibrated condition. Decay curves were analyzed with the Fluoracle Software using the IRF convolution fitting (for lifetime in ns range) or the tail-fitting for longer lifetimes.

SEM analysis and X-rays microanalysis

SEM analysis of gels and aggregates was performed with a Zeiss Sigma HD microscope, equipped with a Schottky FEG source, one detector for backscattered electrons and two detectors for secondary electrons (InLens and Everhart Thornley). The microscope is coupled to an EDX detector (from Oxford Instruments, x-act PentaFET Precision) for X-rays microanalysis, working in energy dispersive mode, the EDX spectra were acquired at 20 kV.

Single crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments

Single crystals suitable for X ray diffraction analysis were obtained by evaporation of the solvent from concentrated chloroform solution of the compound. The crystallographic data for compound 2 were obtained by mounting a single crystal on a loop fiber and transferring it to a Bruker D8 Venture Photon II single crystal diffractometer working with monochromatic MoKα radiation and equipped with an area detector. The APEX 3 program package was used to obtain the unit-cell geometrical parameters. The raw frame data were processed using SAINT and SADABS to obtain the data file of the reflections. The structure was solved using SHELXT69 (Intrinsic Phasing method in the APEX 3 program). The refinement of the structure (based on F2 by full-matrix least-squares techniques) was carried out using the SHELXTL-2018/3 program70. The hydrogen atoms were introduced in the refinement in defined geometry and refined “riding” on the corresponding carbon atoms. Crystallographic data for the structure reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2371629. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

Emission spectra, excitation spectra and lifetime decay measurements were performed on an Edinburgh FLS 1000 UV/Vis/NIR photoluminescence spectrometer at the PanLab department facility, founded by the MIUR-“Dipartimenti di Eccellenza” grant NExuS. Dr. Ilaria Fortunati is acknowledged for her assistance in emission spectra, excitation spectra and lifetime decay measurements. Moreover, the authors are grateful to the financial support from European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 949087) and from MIUR Progetti di Ricerca di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) project “Roxanne” (grand agreement no. 2022ETBCER).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.A. Methodology: A.A., D.A., L.M., and E.P. Investigation: D.A., A.A., L.M., E.P., C.G., and P.P. Funding acquisition: A.A. Project administration: A.A. Supervision: A.A. and D.A. Writing—original draft: D.A., L.M., A.A., E.P., and C.G. Writing—review & editing: D.A., L.M., A.A., E.P., and P.P.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Miguel Soto and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Numerical values of data shown as graphs, as well as all additional data, are available from the corresponding authors. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) website contains the Supplementary crystallographic data for this paper under identifiers 2371629 for complex 2. These data can be obtained free of charge at www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-58890-4.

References

- 1.Lehn, J.-M. Toward complex matter: supramolecular chemistry and self-organization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA99, 4763–4768 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehn, J.-M. Perspectives in chemistry—steps towards complex matter. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.52, 2836–2850 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monreal Santiago, G., Liu, K., Browne, W. R. & Otto, S. Emergence of light-driven protometabolism on recruitment of a photocatalytic cofactor by a self-replicator. Nat. Chem.12, 603–607 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korevaar, P. A. et al. Pathway complexity in supramolecular polymerization. Nature481, 492–496 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rest, C., Kandanelli, R. & Fernández, G. Strategies to create hierarchical self-assembled structures via cooperative non-covalent interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev.44, 2543–2572 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang, X. et al. Cylindrical block copolymer micelles and co-micelles of controlled length and architecture. Science317, 644–647 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilroy, J. B. et al. Monodisperse cylindrical micelles by crystallization-driven living self-assembly. Nat. Chem.2, 566–570 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Greef, T. F. A. et al. Supramolecular polymerization. Chem. Rev.109, 5687–5754 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutz, J.-F., Lehn, J.-M., Meijer, E. W. & Matyjaszewski, K. From precision polymers to complex materials and systems. Nat. Rev. Mater.1, 16024 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wehner, M. & Würthner, F. Supramolecular polymerization through kinetic pathway control and living chain growth. Nat. Rev. Chem.4, 38–53 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogi, S., Sugiyasu, K., Manna, S., Samitsu, S. & Takeuchi, M. Living supramolecular polymerization realized through a biomimetic approach. Nat. Chem.6, 188–195 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aliprandi, A., Mauro, M. & De Cola, L. Controlling and imaging biomimetic self-assembly. Nat. Chem.8, 10–15 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukui, T. et al. Control over differentiation of a metastable supramolecular assembly in one and two dimensions. Nat. Chem.9, 493–499 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang, J. et al. A rational strategy for the realization of chain-growth supramolecular polymerization. Science347, 646–651 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogi, S., Stepanenko, V., Sugiyasu, K., Takeuchi, M. & Würthner, F. Mechanism of self-assembly process and seeded supramolecular polymerization of perylene bisimide organogelator. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 3300–3307 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogi, S., Stepanenko, V., Thein, J. & Würthner, F. Impact of alkyl spacer length on aggregation pathways in kinetically controlled supramolecular polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 670–678 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vantomme, G. & Meijer, E. W. The construction of supramolecular systems. Science363, 1396–1397 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu, Z. et al. Simultaneous covalent and noncovalent hybrid polymerizations. Science351, 497–502 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong, K. M.-C. & Yam, V. W.-W. Self-assembly of luminescent alkynylplatinum(II) terpyridyl complexes: modulation of photophysical properties through aggregation behavior. Acc. Chem. Res.44, 424–434 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yam, V. W.-W., Wong, K. M.-C. & Zhu, N. Solvent-Induced aggregation through metal···metal/π···π interactions: large solvatochromism of luminescent organoplatinum(II) terpyridyl complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.124, 6506–6507 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Po, C., Tam, A. Y.-Y., Wong, K. M.-C. & Yam, V. W.-W. Supramolecular self-assembly of amphiphilic anionic platinum(II) complexes: a correlation between spectroscopic and morphological properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc.133, 12136–12143 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai, S.-W., Chan, M. C.-W., Cheung, T.-C., Peng, S.-M. & Che, C.-M. Probing d8−d8 interactions in luminescent mono- and binuclear cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes of 6-phenyl-2,2‘-bipyridines. Inorg. Chem.38, 4046–4055 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, W. et al. Structural and spectroscopic studies on Pt···Pt and π−π interactions in luminescent multinuclear cyclometalated platinum(II) homologues tethered by oligophosphine auxiliaries. J. Am. Chem. Soc.126, 7639–7651 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma, B. et al. Synthetic control of Pt···Pt separation and photophysics of binuclear platinum complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.127, 28–29 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno-Alcántar, G. et al. Solvent-driven supramolecular wrapping of self-assembled structures. Angew. Chem.133, 5467–5473 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitfield, S. R. & Sanford, M. S. Reactions of platinum(II) complexes with chloride-based oxidants: routes to Pt(III) and Pt(IV) products. Organometallics27, 1683–1689 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen, C. K. J., Zhang, J. Z., Aitken, J. B. & Hambley, T. W. Influence of equatorial and axial carboxylato ligands on the kinetic inertness of platinum(IV) complexes in the presence of ascorbate and cysteine and within DLD-1 cancer cells. J. Med. Chem.56, 8757–8764 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandeira, S., Gonzalez-Garcia, J., Pensa, E., Albrecht, T. & Vilar, R. A redox-activated G-quadruplex DNA binder based on a platinum(IV)–salphen complex. Angew. Chem.130, 316–319 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ten Eikelder, H. M. M., Markvoort, A. J., de Greef, T. F. A. & Hilbers, P. A. J. An equilibrium model for chiral amplification in supramolecular polymers. J. Phys. Chem. B116, 5291–5301 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonkheijm, P., van der Schoot, P., Schenning, A. P. H. J. & Meijer, E. W. Probing the solvent-assisted nucleation pathway in chemical self-assembly. Science313, 80–83 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matern, J., Dorca, Y., Sánchez, L. & Fernández, G. Revising complex supramolecular polymerization under kinetic and thermodynamic control. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 16730–16740 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinter, P., Hennersdorf, F., Weigand, J. J. & Strassner, T. Polymorphic phosphorescence from separable aggregates with unique photophysical properties. Chem. Eur. J.27, 13135–13138 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauro, M. et al. Self-assembly of a neutral platinum(ii) complex into highly emitting microcrystalline fibers through metallophilic interactions. Chem. Commun.50, 7269–7272 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cebrián, C. et al. Luminescent neutral platinum complexes bearing an asymmetric N^N^N ligand for high-performance solution-processed OLEDs. Adv. Mater.25, 437–442 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juliá, F., Bautista, D., Fernández-Hernández, J. M. & González-Herrero, P. Homoleptic tris-cyclometalated platinum(iv) complexes: a new class of long-lived, highly efficient 3LC emitters. Chem. Sci.5, 1875–1880 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perera, T. A., Masjedi, M. & Sharp, P. R. Photoreduction of Pt(IV) chloro complexes: substrate chlorination by a triplet excited state. Inorg. Chem.53, 7608–7621 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Troian-Gautier, L. et al. Halide photoredox chemistry. Chem. Rev.119, 4628–4683 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karimi, M. & Gabbaï, F. P. Photoreductive elimination of PhCl across the dinuclear core of a [GePt]VI complex. Organometallics41, 642–648 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galanti, A. et al. Electronic decoupling in C3-symmetrical light-responsive tris(azobenzene) scaffolds: self-assembly and multiphotochromism. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 16062–16070 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Endo, M. et al. Photoregulated living supramolecular polymerization established by combining energy landscapes of photoisomerization and nucleation–elongation processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 14347–14353 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yagai, S., Karatsu, T. & Kitamura, A. Photocontrollable self‐assembly. Chem. Eur. J.11, 4054–4063 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Younis, M. et al. Recent progress in azobenzene‐based supramolecular materials and applications. Chem. Rec.23, e202300126 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen, Q. et al. Light‐triggered self‐assembly of a spiropyran‐functionalized dendron into nano‐/micrometer‐sized particles and photoresponsive organogel with switchable fluorescence. Adv. Funct. Mater.20, 36–42 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirose, T., Matsuda, K. & Irie, M. Self-assembly of photochromic diarylethenes with amphiphilic side chains: reversible thermal and photochemical control. J. Org. Chem.71, 7499–7508 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maeda, N., Hirose, T., Yokoyama, S. & Matsuda, K. Rational design of highly photoresponsive surface-confined self-assembly of diarylethenes: reversible three-state photoswitching at the liquid/solid interface. J. Phys. Chem. C120, 9317–9325 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao, X. et al. Fluorescence and morphology modulation in a photochromic diarylethene self-assembly system. Langmuir27, 5090–5097 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnstone, M. D., Hsu, C.-W., Hochbaum, N., Andréasson, J. & Sundén, H. Multi-color emission with orthogonal input triggers from a diarylethene pyrene-OTHO organogelator cocktail. Chem. Commun.56, 988–991 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faramarzi, V. et al. Light-triggered self-construction of supramolecular organic nanowires as metallic interconnects. Nat. Chem.4, 485–490 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim, J. et al. Induction and control of supramolecular chirality by light in self-assembled helical nanostructures. Nat. Commun.6, 6959 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain, A., Dhiman, S., Dhayani, A., Vemula, P. K. & George, S. J. Chemical fuel-driven living and transient supramolecular polymerization. Nat. Commun.10, 450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu, J. & Greenfield, J. L. Photoswitchable imines drive dynamic covalent systems to nonequilibrium steady states. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 20720–20727 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wezenberg, S. J., Croisetu, C. M., Stuart, M. C. A. & Feringa, B. L. Reversible gel–sol photoswitching with an overcrowded alkene-based bis-urea supergelator. Chem. Sci.7, 4341–4346 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams, J. A. G. in Photochemistry and Photophysics of Coordination Compounds II (eds Balzani, V. & Campagna, S.) 205–268 (Springer, 2007).

- 54.Du, P. et al. Photoinduced electron transfer in platinum(II) terpyridyl acetylide chromophores: reductive and oxidative quenching and hydrogen production. J. Phys. Chem. B111, 6887–6894 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monnereau, C. et al. Photoinduced electron transfer in platinum(II) terpyridinyl acetylide complexes connected to a porphyrin unit. Inorg. Chem.44, 4806–4817 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris, R. K., Becker, E. D., Cabral de Menezes, S. M., Goodfellow, R. & Granger, P. NMR nomenclature: nuclear spin properties and conventions for chemical shifts (IUPAC Recommendations 2001). Pure Appl. Chem.73, 1795–1818 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Sinn, S., Biedermann, F. & De Cola, L. Platinum complex assemblies as luminescent probes and tags for drugs and toxins in water. Chem. Eur. J.23, 1965–1971 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci.12, e1606 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Wüllen, C. Molecular density functional calculations in the regular relativistic approximation: method, application to coinage metal diatomics, hydrides, fluorides and chlorides, and comparison with first-order relativistic calculations. J. Chem. Phys.109, 392–399 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.7, 3297–3305 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pantazis, D. A., Chen, X.-Y., Landis, C. R. & Neese, F. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for third-row transition metal atoms. J. Chem. Theory Comput.4, 908–919 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neese, F. An improvement of the resolution of the identity approximation for the formation of the Coulomb matrix. J. Comput. Chem.24, 1740–1747 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rolfes, J. D., Neese, F. & Pantazis, D. A. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for the elements Rb–Xe. J. Comput. Chem.41, 1842–1849 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.8, 1057–1065 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys.132, 154104 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem.32, 1456–1465 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys.110, 6158–6170 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neese, F. Efficient and accurate approximations to the molecular spin-orbit coupling operator and their use in molecular g-tensor calculations. J. Chem. Phys.122, 034107 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT—integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A71, 3–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C71, 3–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Numerical values of data shown as graphs, as well as all additional data, are available from the corresponding authors. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) website contains the Supplementary crystallographic data for this paper under identifiers 2371629 for complex 2. These data can be obtained free of charge at www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033. Source data are provided with this paper.