Abstract

Introduction

The retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens (RP-IOL) offers a sutureless solution to complications like aphakia, intraocular lens (IOL) dislocation, and opacification post-cataract surgery. Unlike time-consuming, complication-prone traditional methods, RP-IOL potentially reduces surgical time and complications. This study evaluates RP-IOL’s clinical outcomes to assess its efficacy and safety.

Methods

This single-center retrospective case series reviewed medical records of 68 eyes from 68 patients who underwent RP-IOL implantation between January 2017 and May 2023. Preoperative and postoperative data, including visual acuity (VA), intraocular pressure (IOP), and spherical equivalent (SE), were analyzed.

Results

The mean uncorrected VA improved significantly from 1.25 ± 0.73 (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution) preoperatively to 0.42 ± 0.47 at 1 month postoperatively (P < 0.001). The mean IOP decreased significantly from 17.69 ± 5.01 mmHg preoperatively to 16.09 ± 4.23 mmHg 1 month postoperatively (P = 0.041). Postoperative complications occurred in 35.3% of cases, with the most common being IOP elevation (13.2%), cystoid macular edema (11.8%), and disenclavation of IOL (7.4%). Most complications were successfully managed. The study also included a subanalysis of seven patients with IOL opacification, showing improved VA postoperatively, although without statistical significance due to the small sample size.

Conclusions

RP-IOL implantation is an effective and safe option for secondary IOL implantation or exchange in cases of aphakia, IOL dislocation, and IOL opacification. The procedure offers significant improvements in visual acuity and a reduction in intraocular pressure, with manageable postoperative complications. While the study supports the use of RP-IOL as a viable option, further research with larger sample sizes and prospective designs is recommended to establish its long-term efficacy and safety compared to traditional methods.

Keywords: IOL dislocation, IOL opacification, Retropupillary iris-claw IOL

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Cataract surgery complications, such as intraocular lens (IOL) dislocation, require more effective intervention options. |

| The study evaluated 68 eyes with retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens (RP-IOL) implantation to determine its clinical effectiveness and safety. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Findings indicated significant improvements in visual acuity post-surgery. |

| Postoperative complications were observed in 35.3% of patients, but were largely manageable. |

| The RP-IOL technique offers a promising alternative for secondary IOL implantation, warranting further long-term studies. |

Introduction

It has been over decades since the phacoemulsification has completely changed the surgical treatment option for cataracts. Due to its effectiveness, cataract surgery has become more popular than ever and is now the most frequently performed surgical procedure worldwide, with approximately 20 million cases conducted annually [1]. As the number of cataract surgeries has skyrocketed, so too have the associated complications, the most significant of which is dislocation of the intraocular lens (IOL).

There has been an ongoing debate on the most effective way to correct IOL dislocation. Many attempts have been made to develop an efficient yet effective procedure for IOL exchange, but none of them were market-changing. Conventional secondary IOL implantation via scleral sutures has been the treatment of choice, and is still employed by many clinicians. This method has proven effective for a longer time compared to others, and it respects the anatomy of the eye. However, it is relatively time-consuming and requires sufficient experience from a surgeon [2]. Furthermore, various complications such as vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment (RD), choroidal detachment, and suture-related complications have been reported [3]. Anterior chamber IOLs were proposed as an alternative to conventional techniques in the 1980s. This technique gained popularity due to its simplicity and shorter operation time, but soon after, severe complications, including secondary glaucoma, uveitis, and reduced endothelial cell count (ECC) were reported [4].

Retropupillary iris-claw IOL (RP-IOL) was an attempt to merge the strong points of the conventional method and anterior chamber IOLs. First introduced by Amar in the 1980s, this method allowed the implanted lens to be positioned anatomically, reducing the complications associated with anterior chamber IOL placement. Since the method allows the fixation of IOL with only two points of “clawing” at the posterior surface of the iris, it does not require a suture of IOL, and thus is time-effective and prevents a variety of suture-related complications. RP-IOL has been proven to be an efficient technique for correcting aphakic status due to various conditions with or without IOL dislocation [2, 5–9].

IOL opacification is one of the rare complications after cataract surgery. It is understood to be caused by particular surgeries including Descemet’s stripping (automated) endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK/DSAEK), Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty, pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with gas or air injection, and possible association with conditions such as asteroid hyalosis, uveitis, diabetes, hypertension, and glaucoma have been suggested [10, 11]. Although many of the cases remain mild, some can lead to severe visual impairment, leading to inevitable IOL exchange. IOL exchange in IOL opacification remains a challenging task, since some damage of the intact ocular anatomy is unavoidable during the procedure. There is no consensus on the best method, possibly due to a wide variety of preoperative status. There have been only limited reports on applying the conventional method of IOL posterior chamber implantation, sulcus fixation, and scleral fixation [11, 12].

In this study, we aimed to analyze the clinical outcome of RP-IOL implantation in various indications, including aphakia, IOL dislocation, and IOL opacification.

Methods

Study Population

This was a single-center, retrospective case series study in a tertiary hospital (Soonchunhyang University Hospital Bucheon) located in South Korea. Patients who underwent RP-IOL implantation from January 1, 2017 to May 1, 2023 in the Ophthalmology Department of Soonchunhyang University Hospital Bucheon were enrolled. The data were accessed at 01/06/2023. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the institutional review board of Soonchunhyang University Hospital (IRB No.2024-06-009). The requirement of informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, and the data were anonymized before the analysis.

Preoperative and Postoperative Examination

Medical records, including past medical history and preoperative and postoperative data of each patient, were reviewed. Preoperative measures included uncorrected visual acuity (VA), best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure (IOP), refractive data, axial length, ECC, and pupil diameter. Visual acuities were originally measured with a Snellen vision chart and were converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) value for statistical analyses. IOP was measured using a non-contact tonometer. Refractive data, including spherical equivalent (SE) and corneal astigmatism, were obtained using an auto kerato-refractometer (KR-800A; Topcon Medical Systems, Inc., Oakland, NJ, USA). Biometry measurements were obtained using a IOLMaster 500 or 700 (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany). IOL diopter was determined using the SRK/T formula using an A-constant of 116.9, the manufacturer’s recommendation for retropupillary fixation. ECC was measured using specular microscopy SP-1P (Topcon Medical Systems, Inc.).

Postoperative measures included uncorrected VA, BCVA, IOP, refractive data, and the presence of postoperative complications. The presence of postoperative complications included iris atrophy and/or focal defect, elevated IOP, disenclavation, cystoid macular edema (CME), RD, uveitis, and decreased ECC. All postoperative data were obtained at immediate postoperative follow-up, and VA, BCVA, and IOP were measured at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and then yearly. The presence of postoperative complication was evaluated at every visit until the last visit.

Surgical Technique

All surgeries were performed by two experienced vitreoretinal surgeons of the institution under either general or peribulbar anesthesia, and both surgeons used the same technique (Fig. 1). All patients underwent a 25-gauge PPV (EVA; DORC, Zuidland, The Netherlands). After the core vitrectomy and peripheral shaving were performed, opacified, dislocated, or dropped IOL was removed when present with the following steps. Two paracentesis incisions were made at the 2 o’clock and 10 o’clock positions using a sharp blade. The anterior chamber was filled with viscoelastics, and the dislocated IOL was lifted into the anterior chamber. After the conjunctival incision was made, a 5.5-mm scleral flap was created using a crescent blade, and a sclerocorneal incision was made using a steel keratome. The dislocated IOL was then gently removed via sclerocorneal incision. RP-IOL (Artisan Aphakia Model 205; Ophtec BV, Groningen, The Netherlands) was prepared for use, and after filling the anterior chamber with viscoelastics again, the IOL was implanted through previously created sclerocorneal incision. The IOL was then fixated at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions of the posterior iris using a lens forceps and an enclavation needle (Ophtec BV). The scleral tunnel was sutured using 10-0 nylon. The anterior chamber was irrigated and the viscoelastic material was removed. The conjunctival incision was sutured using 7-0 vicryl.

Fig. 1.

Surgical procedures for retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens implantation

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using R for Windows, version 4.4.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive measures were used to summarize the baseline patient characteristics. Paired t test was used to compare the measurements at two time-points. All P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

We analyzed a total of 68 eyes of 68 patients who underwent RP-IOL implantation. Among them, 52/68 (76.5%) were male and 16/68 (23.5%) were female (Table 1). The mean follow-up period was 19.12 ± 17.37 months. Mean uncorrected preoperative VA (logMAR) was 1.25 ± 0.73, while mean best-corrected VA (logMAR) was 0.58 ± 0.73. The mean preoperative IOP was 17.69 ± 5.01 mmHg. The mean preoperative SE was 5.35 ± 5.63 diopters, and mean preoperative corneal astigmatism was − 0.97 ± 0.77 diopters. Mean axial length was 24.02 ± 1.33 mm. Mean preoperative ECC was 2295.21 ± 597.10 cells/mm2. The most common preoperative diagnosis was IOL dislocation or subluxation, which accounted for 39/68 (57.4%) of the patients. Complicated cataract surgery and related aphakia (18/68, 26.5%) was the second most common reason for RP-IOL, followed by IOL opacity (7/68, 10.3%) and crystalline lens dislocation (3/68, 4.4%).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients who underwent retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens implantation surgery

| Variable | N (%) or mean ± standard deviation |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.19 ± 9.67 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 52 (76.5) |

| Female | 16 (23.5) |

| Follow-up period (months) | 19.12 ± 17.37 |

| Preoperative measurements | |

| Preoperative uncorrected VA (logMAR) | 1.25 ± 0.73 |

| Preoperative best-corrected VA (logMAR) | 0.58 ± 0.73 |

| Preoperative IOP (mmHg) | 17.69 ± 5.01 |

| Spherical equivalent (diopter) | 5.35 ± 5.63 |

| Corneal astigmatism (diopter) | − 0.97 ± 0.77 |

| Axial length (mm) | 24.02 ± 1.33 |

| Endothelial cell count (/mm2) | 2295.21 ± 597.10 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | |

| Complicated cataract surgery and related aphakia | 18 (26.5) |

| Crystalline lens dislocation | 3 (4.4) |

| IOL dislocation, subluxation | 39 (57.4) |

| IOL opacity | 7 (10.3) |

| Vitreous prolapse | 1 (1.5) |

VA visual acuity, IOP intraocular pressure, IOL intraocular lens

Visual Acuity

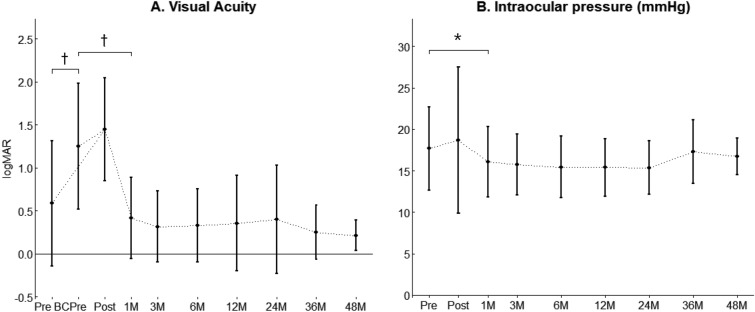

The change in VA before and after the surgery is presented in Fig. 2A. The mean preoperative uncorrected VA (logMAR) was 1.25 ± 0.73, while the mean preoperative best-corrected VA was 0.58 ± 0.73. After the surgery, the mean uncorrected VA was 1.49 ± 0.60 at immediate postop, and it changed to 0.42 ± 0.47 at 1 month, 0.32 ± 0.41 at 3 months, 0.33 ± 0.43 at 6 months, 0.35 ± 0.55 at 1 year, 0.40 ± 0.63 at 2 years, 0.40 ± 0.63 at 3 years, and 0.21 ± 0.18 at 4 years after the surgery, respectively. The mean preoperative uncorrected VA was significantly lower than the mean preoperative best-corrected VA (P < 0.001). Although the mean uncorrected VA right after the surgery did not show any significant difference from the mean preoperative uncorrected VA, that of 1 month after the surgery was significantly higher (P < 0.001). This significant difference of uncorrected mean VA compared to preoperative uncorrected mean VA lasted until 4 years after the surgery.

Fig. 2.

Changes in A visual acuity and B intraocular pressure before and after retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens implantation. The small black dots represent mean data points and error bars represent standard deviations. Pre preoperative, Post postoperative days, M month, BC best-corrected. *P < 0.05. †P < 0.001

Intraocular Pressure

The trend for IOP before and after the surgery is presented in Fig. 2B. The mean preoperative IOP was 17.69 ± 5.01 mmHg, and it changed to 18.71 ± 8.83 mmHg at immediate postop, 16.09 ± 4.23 mmHg at 1 month, 15.77 ± 3.67 mmHg at 3 months, 15.44 ± 3.71 mmHg at 6 months, 15.41 ± 6.47 mmHg at 1 year, 15.37 ± 3.21 mmHg at 2 years, 17.29 ± 3.85 mmHg at 3 years, 16.71 ± 2.21 mmHg at 4 years after the surgery, respectively. The mean preoperative IOP and the mean IOP a day after the surgery did not show any significant difference (P = 0.396), but the mean IOP a month after the surgery was significantly lower than that before the surgery (P = 0.041). This difference lasted until 1 year after the surgery, and after that, there was no significant difference in mean IOP compared to before the surgery.

Spherical Equivalent and Postoperative Complications

The mean postoperative SE was significantly lower than that before the surgery (− 0.38 vs. 3.93 diopters; P < 0.001). Table 2 presents the postoperative complications after RP-IOL implantation and its frequency. A total of 24 eyes (35.3%) had at least one of the complications. Among them, the most common was IOP elevation (9/68, 13.2%). All IOP elevation was temporary and was well treated with topical medication. However, in one patient, although there was only a moderate IOP elevation (31 mmHg) a day after the surgery (which was well resolved with topical medication), there was a sudden decrease in VA to counting fingers at 6 months after the surgery with pale disc, and the VA did not improve after then. The second most common postoperative complication was CME (8/68, 11.8%). Intravitreal steroid injection was performed for these patients, and they responded well in most cases but in two cases with a previous history of vitrectomy and one case in which RD occurred after the surgery, CMEs were proven to be refractory. Five of 68 patients (7.4%) suffered from disenclavation of the IOL, and all cases went under successful repositioning. Two patients presented with iris atrophy/focal defect (2/68, 2.9%), in which one of the cases presented with disenclavation. RD developed in one patient (1/68, 1.5%) 3 months after the RP-IOL implantation. Although the retina was reattached, a moderate decrease in visual acuity occurred and persisted.

Table 2.

Postoperative complications in patients undergoing retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens implantation

| Complication | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Cystoid macular edema | 8 (11.8) |

| Disenclavation | 5 (7.4) |

| Intraocular pressure elevation | 9 (13.2) |

| Iris atrophy/focal defect | 2 (2.9) |

| Retinal detachment | 1 (1.5) |

Retropupillary IOL for Patients with IOL Opacity

Subanalysis for seven patients who underwent RP-IOL implantation for IOL opacity was done. Out of seven patients, five were male (71.4%) and two were female (28.63%). The mean age for patients with IOL opacity was 63.00 ± 10.46 years, and they were followed for mean of 18.86 ± 17.60 months. Preoperative values were as follows: [1] mean axial length, 23.50 ± 0.80 mm; [2] mean SE, 0.98 ± 2.71 diopters; [3] mean ECC, 2577.57 ± 506.15; [4] mean uncorrected VA (logMAR), 1.28 ± 0.75; [5] mean best-corrected VA (logMAR), 1.22 ± 0.83; [6] mean IOP, 15.00 ± 3.22 mmHg. Mean uncorrected VA changed to 1.59 ± 0.79 after the surgery, and it improved to 0.45 ± 0.41 at 1 month, 0.40 ± 0.37 at 3 months, 0.26 ± 0.25 at 6 months, and 0.28 ± 0.24 at 1 year after the surgery. However, there was no statistical significance in all time points after surgery when compared to preoperative VA. Mean IOP changed to 21.57 ± 10.42 mmHg after surgery, and it became 17.14 ± 2.91 mmHg at 1 month, 15.20 ± 4.14 mmHg at 3 months, 16.80 ± 4.32 mmHg at 6 months, and 12.80 ± 2.59 mmHg at 1 year after the surgery. There was no significant mean difference in IOP except for 1 year after the surgery in which the mean IOP was significantly lower than preoperative mean IOP (P = 0.033). Two out of seven patients (28.6%) experienced temporary IOP elevation which was controlled with topical medication.

Discussion

The results of this study show that the implantation of RP-IOL resulted in a significant uncorrected VA increase a month after the surgery (mean – 0.83 logMAR), which lasted until 4 years. IOP was significantly lower a month after the surgery, and this difference disappeared a year after the surgery. Nearly one-third of patients (35.3%) experienced various postoperative complications of which the most common ones being increased IOP (13.2%), CME (11.8%), and disenclavation (7.4%), but most of the cases resolved without further complication.

RP-IOL implantation is regarded as an effective and considerably safe method for rescuing various cases of absence of zonular support [5, 6, 13–17]. A review report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology concluded that there was no superiority of any single IOL implantation technique, including RP-IOL in the absence of zonular support, and that each technique has its own profile of inherent risk of postoperative complications [13]. Although many of the reports were based on retrospective studies, a prospective randomized clinical trial to compare the long-term efficacy and safety of IOL exchange by RP-IOL implantation and IOL repositioning of scleral suturing also reported that there was no significant differences in the two methods regarding the VA and safety measures [18]. A recent study that compared the long-term outcome between RP-IOL implantation and the Yamane technique that has been utilized by many clinicians nowadays showed that both techniques were effective in increasing corrected VA, and that the Yamane group exhibited less predictable refractive outcomes [15]. Another recent study that compared relocation with iris suture versus exchange to sutureless iris-claw IOL concluded that both techniques for dislocated IOLs yielded similarly favorable outcomes, with IOL relocation resulting in less postoperative astigmatism while IOL exchange offered the advantage of shorter surgical time [19]. The result of our study also shows that implantation of RP-IOL was a relatively effective and safe method with comparable or better mean postoperative VA results (20/40 [Snellen] at 3 months postoperatively), which ranged from 20/115 to 20/40 (Snellen) [13].

Although RP-IOL implantation is widely used for various cases of absence of zonular support, including IOL dislocation and surgically induced aphakia after complicated cataract surgery, literature has been scarce for cases of opacity [20–22]. This is because of the rarity of IOL opacity itself and the variety of the preoperative status regarding capsular support and the need for vitrectomy in cases of IOL opacity [22]. In many cases, capsules are intact and capsular support adequate, and new IOL can be implanted into the bag or into the sulcus [10, 12, 23]. However, in some cases with insufficient zonular stability with possible vitreous prolapse, vitrectomy is necessary and RP-IOL can be considered as a viable option [10]. In a case series with 48 eyes of patients with opacified IOLs, 11 cases resulted in implantation of RP-IOL. There was no report of complication based on the surgical method, but the authors did report that in total 9/48 (18%) underwent further surgical procedures due to IOL re-dislocation (n = 2), RD (n = 6), epiretinal membrane (n = 2), pupillary block (n = 1), in which three of six RD patients used RP-IOL [22]. Our study included seven patients with IOL opacity who underwent RP-IOL implantation, and showed that the mean VA was increased after the surgery (mean uncorrected VA [logMAR]; 0.26 ± 0.25 at 6 months), although there was no statistical significance probably due to a small number of patients (P = 0.079 at 1 month, 0.102 at 3 months, 0.055 at 6 months). Unlike in Marker et al.’s report, there was no RD development in our patients with IOL opacity, and increased IOP were controlled well with topical medication in 2/7 (28.6%) patients.

Increased IOP was the most common complication after RP-IOL implantation in our study, with 13.2% of patients. However, all cases were controlled with topical antiglaucoma medication, and mean IOP values were significantly lower until 1 year after surgery, and it was comparable after then. This was in agreement with previous reports which reported the incidence of increased IOP after RP-IOL implantation from 7 to 13%, and aids the view that RP-IOL is an anatomic IOL and does not induce angle closure of pupillary block in normal circumstances [5, 16, 21]. Report of prolonged increased IOP or glaucoma development (elevated IOP lasting for over 3 months) was not common, with rates of 0–3.3%, presumably less than other methods of IOL exchange [13].

Development of CME is reported to occur in 0–11.5% of patients who underwent RP-IOL [5, 13, 21, 24, 25]. Our cases showed a relatively higher percentage of patients with CME development (11.8%) compared to previous reports, possibly due to including patients with a previous history of vitrectomy and complex cataract surgery, which led to aphakia. Furthermore, the fact that not all of the included patients underwent total vitrectomy might have influenced the occurrence of CME after the surgery. Choi et al.’s report [5] shows a relatively lower CME incidence rate of 3.9%, possibly due to the exclusion of patients with a previous history of uveitis and all patients undergoing total vitrectomy, and compares the rate with Gonnermann et al.’s (8.7%) [26], which included various cases with possible uveal pathologies and did not perform total vitrectomy in all cases. Jayamadhury et al.’s report [24], which reported high percentage of CME development in 11.47% also included patients with various previous history, and performed partial vitrectomy when needed.

Disenclavation/dislocation occurred in 0.8–6% of previous reports, and our patients showed a higher percentage of 7.4%, but in all cases, the IOL was repositioned successfully [13]. Although hard to compare directly, this rate of disenclavation seems to be relatively lower than the rate of dislocation of scleral-fixated IOLs (0–28%) [13]. Furthermore, it seems that RP-IOL is fairly easier and less time-consuming to reposition compared to other methods of IOL exchange, especially compared to ones using sutures. It is well known that suture-related complications lead to many other complications ranging from inflammation, need for IOL exchange, and/or endophthalmitis [27, 28]. Using RP-IOL lets surgeons be free of these various suture-related complications. To minimize disenclavation risks, meticulous enclavation technique, careful patient selection, and reducing iris manipulation during surgery are essential considerations. Iris atrophy/focal defect seems on the opposite end of suture-related complications, since it usually occurs after implantation of iris-claw IOLs including RP-IOL. Previous reports show the occurrence of 6.55% to 13%, but it occurred in only 2.9% of our patient, and none of the two patients complained of any symptom related to iris defect [5, 16, 25]. Although uveitis is reported in up to 7.7% of the patients after RP-IOL implantation, no patient had such inflammation postoperatively in our study [25].

The overall complication rate in this study (35.3%) appears relatively high compared to previous reports of other IOL implantation techniques, including scleral-fixated IOLs, which show complication rates ranging from 0 to 28% [13, 15, 18]. This rate may be somewhat inflated, as 13.2% of the cases involved only transient IOP elevation. The disenclavation rate in our study (7.4%) was higher than the 0.8–6% reported in previous RP-IOL studies [13], but still generally lower than the reported dislocation rates for scleral-fixated IOLs (0–28%) [13]. The incidence of CME (11.8%) was also at the upper limit of the reported range for RP-IOL implantation (0%–11.5%) [5, 13, 21, 24, 25] and comparable to rates seen with scleral-fixated or sutured techniques, particularly in eyes with pre-existing risk factors [13, 25]. This relatively high CME rate in our cohort may be attributed to the inclusion of patients with a history of vitrectomy or complex cataract surgery, as well as the fact that total vitrectomy was not performed in all cases. Despite these findings, the complication rates observed remain within the expected range for alternative IOL implantation methods, especially in complex surgical cases. Importantly, most complications were effectively managed without lasting sequelae.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective design and relatively small number of patients. Indications for surgery varied, and this might have hindered us from giving clearer effectiveness of the surgical method based on a homogenous population. Due to the absence of a control group, a direct comparison between the RP-IOL method and alternative techniques was not possible. The number of patients with IOL opacity was small, and a study with a larger population would help in assessing the efficacy of using RP-IOL in such cases. Further investigation involving a larger cohort is planned to validate these findings. Best-corrected VA was not available for all visits after the surgery and therefore could not be assessed postoperatively. Serial assessment of SE and ECC was not available, and therefore was not able to be analyzed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reports that implantation of RP-IOL is a relatively efficient and safe method for various indications for secondary IOL implantation or IOL exchange, including IOL opacity, comparable with previous and newer methods including IOL scleral fixation. Although no clear consensus can be asserted for the best surgical method in each different real-world clinical scenario of IOL exchange, RP-IOL implantation seems to be a viable and effective option that can be effective and efficient for both the patient and the surgeon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyo Song Park, Jung Woo Han/Data curation: Hyo Song Park, Sung Chul Park/Formal analysis: Hyo Song Park/Funding acquisition: Hyo Song Park, Jung Woo Han/Investigation: Hyo Song Park/Methodology: Hyo Song Park, Jung Woo Han/Resources: Hyo Song Park, Jung Woo Han/Supervision: Jin Ha Kim, Young Hoon Ohn, Tae Kwann Park, Jung Woo Han/Validation: Hyo Song Park, Jung Woo Han/Visualization: Hyo Song Park/Writing-original draft: Hyo Song Park/Writing-review and editing: Hyo Song Park, Jung Woo Han.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023–00209639 and RS-2023–00238454). This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023–00209639). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Hyo Song Park has nothing to disclose. Sung Chul Park has nothing to disclose. Jin Ha Kim has nothing to disclose. Young Hoon Ohn has nothing to disclose. Tae Kwann Park has nothing to disclose. Jung Woo Han has nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of Soonchunhyang University Hospital (IRB No.2024-06-009). The requirement of informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, and the data were anonymized before the analysis. Informed consent was waived from the IRB due to the retrospective design.

References

- 1.Rossi T, Romano MR, Iannetta D, et al. Cataract surgery practice patterns worldwide: a survey. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021;6(1): e000464. 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shuaib AM, El Sayed Y, Kamal A, El Sanabary Z, Elhilali H. Transscleral sutureless intraocular lens versus retropupillary iris-claw lens fixation for paediatric aphakia without capsular support: a randomized study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(6):e850–9. 10.1111/aos.14090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies EC, Pineda R. Complications of scleral-fixated intraocular lenses. Semin Ophthalmol. 2018;33(1):23–8. 10.1080/08820538.2017.1353808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawada T, Kimura W, Kimura T, et al. Long-term follow-up of primary anterior chamber intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24(11):1515–20. 10.1016/s0886-3350(98)80176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi EY, Lee CH, Kang HG, et al. Long-term surgical outcomes of primary retropupillary iris claw intraocular lens implantation for the treatment of intraocular lens dislocation. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):726. 10.1038/s41598-020-80292-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoo TK, Lee SM, Lee H, Choi EY, Kim M. Retropupillary iris fixation of an artisan myopia lens for intraocular lens dislocation and aphakia in eyes with extremely high myopia: a case series and a literature review. Ophthalmol Ther. 2022;11(3):1251–60. 10.1007/s40123-022-00494-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forlini M, Soliman W, Bratu A, et al. Long-term follow-up of retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens implantation: a retrospective analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:143. 10.1186/s12886-015-0146-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristianslund O, Råen M, Østern AE, Drolsum L. Late in-the-bag intraocular lens dislocation: a randomized clinical trial comparing lens repositioning and lens exchange. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(2):151–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toro MD, Longo A, Avitabile T, et al. Five-year follow-up of secondary iris-claw intraocular lens implantation for the treatment of aphakia: anterior chamber versus retropupillary implantation. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4): e0214140. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackert M, Muth DR, Vounotrypidis E, et al. Analysis of opacification patterns in intraocular lenses (IOL). BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021;6(1): e000589. 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grzybowski A, Markeviciute A, Zemaitiene R. A narrative review of intraocular lens opacifications: update 2020. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(22):1547. 10.21037/atm-20-4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SM, Choi S. Clinical efficacy and complications of intraocular lens exchange for opacified intraocular lenses. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2008;22(4):228–35. 10.3341/kjo.2008.22.4.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen JF, Deng S, Hammersmith KM, et al. Intraocular lens implantation in the absence of zonular support: an outcomes and safety update: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(9):1234–58. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iranipour BJ, Rosander JH, Zetterberg M. Visual improvement and lowered intraocular pressure after surgical management of in-the-bag intraocular lens dislocation and aphakia correction; retrospective analysis of scleral suturing versus retropupillary fixated iris-claw intraocular lens during a 5-year period. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:315–24. 10.2147/OPTH.S445244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerin PL, Guerin GM, Pastore MR, Gouigoux S, Tognetto D. Long-term functional outcome between Yamane technique and retropupillary iris-claw technique in a large study cohort. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2024;50(6):605–10. 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim MJ, Han GL, Chung TY, Lim DH. Comparison of clinical outcomes among conventional scleral fixation, retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens implantation, and intrascleral fixation. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2022;36(5):413–22. 10.3341/kjo.2022.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thulasidas M. Retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lenses: a literature review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:2727–39. 10.2147/OPTH.S321344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalby M, Kristianslund O, Drolsum L. Long-term outcomes after surgery for late in-the-bag intraocular lens dislocation: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;207:184–94. 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellucci C, Mora P, Romano A, Tedesco SA, Troisi M, Bellucci R. Iris fixation for intraocular lens dislocation: relocation with iris suture versus exchange to sutureless iris claw IOL. J Clin Med. 2024;13(21):6528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart SA, McNeely RN, Chan WC, Moore JE. Visual and refractive outcomes following exchange of an opacified multifocal intraocular lens. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:1883–91. 10.2147/OPTH.S362930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang HG, Jun JW, Choi EY, et al. Comparison of long-term surgical outcomes for scleral-fixated versus retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;49(7):686–95. 10.1111/ceo.13965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Märker DA, Radeck V, Barth T, Helbig H, Scherer NCD. Long-term outcome and complications of IOL-exchange. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:3243–8. 10.2147/OPTH.S436963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vounotrypidis E, Schuster I, Mackert MJ, et al. Secondary intraocular lens implantation: a large retrospective analysis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(1):125–34. 10.1007/s00417-018-4178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelkar A, Shah R, Vasavda V, Kelkar J, Kelkar S. Primary iris claw IOL retrofixation with intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide in cases of inadequate capsular support. Int Ophthalmol. 2018;38(1):111–7. 10.1007/s10792-017-0467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayamadhury G, Potti S, Kumar KV, et al. Retropupillary fixation of iris-claw lens in visual rehabilitation of aphakic eyes. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64(10):743–6. 10.4103/0301-4738.195012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonnermann J, Klamann MK, Maier AK, et al. Visual outcome and complications after posterior iris-claw aphakic intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(12):2139–43. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vote BJ, Tranos P, Bunce C, Charteris DG, Da Cruz L. Long-term outcome of combined pars plana vitrectomy and scleral fixated sutured posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(2):308–12. 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luk AS, Young AL, Cheng LL. Long-term outcome of scleral-fixated intraocular lens implantation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(10):1308–11. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.