ABSTRACT

Background: This study aims to elucidate the causal relationship between childhood maltreatment (CM) and subsequent mental health outcomes, including major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety (ANX), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide attempts, and non-fatal self-harm. Utilising Mendelian Randomisation (MR) and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) data from individuals of European descent, this research applies a rigorous analytical methodology to large-scale datasets, overcoming the confounding variables inherent in previous observational studies.

Methods: Genetic data were obtained from publicly available GWAS on individuals of European ancestry, focusing on Childhood Maltreatment (CM), Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Anxiety (ANX), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Age at First Episode of Depression, Number of Depression Episodes, Non-fatal self-harm, and Suicide Attempts. Mendelian Randomisation (MR) analyses were conducted to investigate the causal impact of CM on these outcomes. Sensitivity analyses included IVW, MR Egger, WM, and MR-PRESSO. FDR corrections were applied to account for multiple testing. Results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) with confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: Significant associations were identified between CM and the likelihood of developing MDD (IVW: OR = 2.28, 95% CI = 1.66–3.14, PFDR < .001), ANX (IVW: OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.00–1.02, PFDR =.032), and PTSD (IVW: OR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.43–3.67, PFDR =.001). CM was also linked to increased non-fatal self-harm (IVW: OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.04–1.08, PFDR <.001), higher frequency of depressive episodes (IVW: β=0.31, 95% CI = 0.17–0.46, PFDR <.001), and earlier onset of depression (IVW: β=−0.17, 95% CI = −0.32 to – 0.02, PFDR =.033). No significant association was found between CM and suicide attempts (IVW: OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.81–1.45, PFDR =.573).

Conclusion: This study provides robust evidence that CM is a significant causal factor for MDD, ANX, PTSD, and non-fatal self-harming behaviours. It is associated with a higher frequency of depressive episodes and earlier onset of depression. These findings highlight the need for early intervention and targeted prevention strategies to address the long-lasting psychological impacts of CM.

KEYWORDS: Childhood maltreatment, major depressive disorder, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder, Mendelian randomisation

HIGHLIGHTS

Our study employs Mendelian randomisation to demonstrate that CM directly increases the risk of developing major depressive disorder, anxiety, non-fatal self-harm, suicide attempts, and post traumatic stress disorder in later life.

The findings indicate that individuals who experienced CM are significantly more likely to suffer from depression, PTSD and anxiety, underscoring the long-term negative impacts of early adverse experiences.

The research highlights the critical need for early prevention and intervention strategies. It reveals that CM not only elevates the likelihood of more frequent and earlier-onset depression but also underscores the necessity for specialised support for affected individuals.

Abstract

Antecedentes: Este estudio busca dilucidar la relación causal entre el maltrato infantil (MI) y las consecuencias posteriores en la salud mental, incluyendo el trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM), la ansiedad (ANS), el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT), los intentos de suicidio y las autolesiones no letales. Utilizando datos de aleatorización mendeliana (AM) y estudios de asociación de todo el genoma (GWAS, por sus siglas en inglés) de personas de ascendencia europea, esta investigación aplica una rigurosa metodología analítica a conjuntos de datos a gran escala, superando las variables de confusión inherentes a estudios observacionales previos.

Métodos: Los datos genéticos se obtuvieron de GWAS públicos en individuos de ascendencia europea, centrándose en maltrato infantil (MI), trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM), ansiedad (ANS), trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT), edad al primer episodio de depresión, número de episodios de depresión, autolesiones no fatales e intentos de suicidio. Se realizaron análisis de aleatorización mendeliana (AM) para investigar el impacto causal del MI en estos resultados. Los análisis de sensibilidad incluyeron IVW, MR Egger, WM y MR-PRESSO. Se aplicaron correcciones FDR para considerar la multiplicidad de pruebas. Los resultados se presentaron como probabilidades (OR, por sus siglas en inglés) con intervalos de confianza (IC).

Resultados: Se identificaron asociaciones significativas entre MI y la probabilidad de desarrollar TDM (IVW: OR = 2,28, IC 95% = 1,66–3,14, PFDR < 0,001), ANS (IVW: OR = 1,01, IC 95% = 1,00–1,02, PFDR = 0,032) y TEPT (IVW: OR = 2,29, IC 95% = 1,43–3,67, PFDR = 0,001). El MI también se relacionó con un aumento de las autolesiones no fatales (IVW: OR = 1,06; IC del 95% = 1,04–1,08; PFDR <0,001), una mayor frecuencia de episodios depresivos (IVW: β = 0,31; IC del 95% = 0,17–0,46; PFDR <0,001) y un inicio más temprano de la depresión (IVW: β = −0,17; IC del 95% = −0,32 a – 0,02; PFDR = 0,033). No se encontró una asociación significativa entre el MI y los intentos de suicidio (IVW: OR = 1,09; IC del 95% = 0,81–1,45; PFDR = 0,573).

Conclusión: Este estudio proporciona evidencia sólida de que el MI es un factor causal significativo para el TDM, la ansiedad, el TEPT y las conductas de autolesión no letales. Se asocia con una mayor frecuencia de episodios depresivos y una aparición más temprana de la depresión. Estos hallazgos resaltan la necesidad de una intervención temprana y estrategias de prevención específicas para abordar los impactos psicológicos a largo plazo del MI.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Maltrato infantil, trastorno depresivo mayor, ansiedad, trastorno por estrés postraumático, aleatorización mendeliana

1. Introduction

Childhood maltreatment (CM) typically refers to actions or negligence that cause actual or potential harm to children under 18, potentially affecting their health, survival, development, or dignity. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines childhood maltreatment (CM) as all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, and exploitation that result in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, development, or dignity (WHO, Child Maltreatment, 2020). Forms of maltreatment include, but are not limited to, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and physical or emotional neglect (WHO, Child Maltreatment, 2020). Abuse refers to harmful actions such as hitting, sexually exploiting, or verbally assaulting a child (CDC, 2024). Neglect, on the other hand, involves the failure to provide for a child’s basic needs, including physical, emotional, and educational necessities (Gonzalez et al., 2024). The adverse impacts of CM on an individual's physical and mental health have been recognised as a significant public health issue. According to the World Health Organisation, nearly three in four children aged 2–4 years regularly suffer physical punishment and/or psychological violence at the hand s of parents and caregivers. Additionally, one in five women and one in thirteen men report having been sexually abused as a child aged 0–17 years (Kelly et al., 2019). Maltreatment leads not only to short-term physical or psychological harm to children but also to severe and enduring traumatisation, which has drawn increasing scholarly attention in recent years. Recent studies have further emphasised the long-term adverse effects of childhood maltreatment on mental health, physical health, and social outcomes, highlighting its critical public health implications (Lacey et al., 2020; Smith & Pollak, 2020).

An increasing body of research indicates that CM leads to a range of mental health issues, significantly increasing the risk of internalising problems such as major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders (ANX), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Hughes et al., 2017; McLaughlin et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2017). Early experiences of CM are linked to a higher likelihood of developing these disorders (Li et al., 2016). Additionally, CM can lead to externalising behavioural problems, including non-fatal self-harm, suicide attempts, violence, and substance abuse (Abajobir et al., 2017; Baiden et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018). Risky sexual behaviour and adverse life outcomes like teen pregnancies are also associated with CM (Charlton et al., 2018). Furthermore, CM increases the risk of various somatic and mental disorders by affecting the development of the neurological, endocrine, and immune systems (Gilbert et al., 2015; Hughes et al., 2017; Marin et al., 2021; Shields et al., 2016; Suglia et al., 2018), resulting in conditions such as depression and anxiety characterised by low mood and panic (Li et al., 2016, 2022).

The connection between CM and the development of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, has been extensively explored. For instance, M. Li et al. investigated the direct impact of CM on depression and anxiety through an attachment and cognitive lens (Li et al., 2016), while Huh et al. delved into the underlying mechanisms linking CM with MDD and ANX, focusing on emotion regulation (Huh et al., 2017). Research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) has highlighted the long-term bio-psycho-social impacts of childhood adversity. Previous studies have shown that early life stressors, such as maltreatment, neglect, and household dysfunction, are linked to various negative health outcomes, including mental disorders like MDD and ANX (Bellis et al., 2019; Hughes et al., 2017). This body of literature underscores the importance of addressing childhood maltreatment to improve long-term health and well-being.

Despite extensive research, there is a need for more precise methodologies to establish causality between CM and mental health outcomes. Observational studies often face ethical and practical constraints and are limited by potential confounding factors and reporting biases (Pingault et al., 2018). Incorporating genetic information into samples can enhance causal inference capabilities. Mendelian Randomisation (MR) analysis, which uses genetic variations as instrumental variables to circumvent confounders or reverse causality, is widely employed in investigating public health risk factors (Davies et al., 2018). However, there is a noticeable lack of studies using MR methods to investigate the causal links between CM and the risks of MDD, ANX, PTSD, non-fatal self-harm, and suicide attempts. This study aims to fill this gap by employing MR analysis and utilising data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted on individuals of European descent. By overcoming the limitations of previous observational studies, our research seeks to provide robust evidence of the causal relationships between CM and specific mental health outcomes. This evidence can inform the development of targeted prevention and intervention strategies to mitigate the adverse psychological effects of CM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Research design

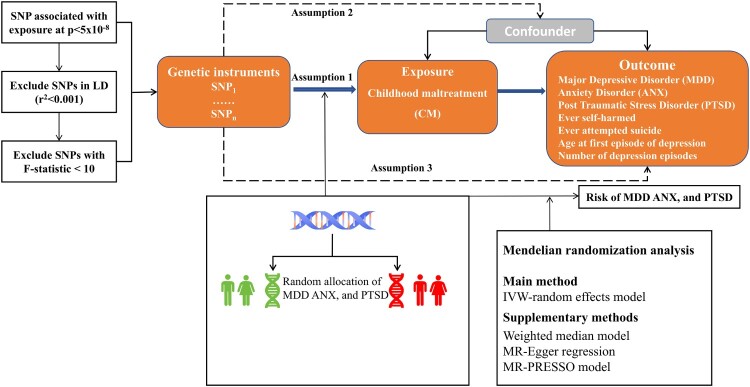

Our research synthesises multiple data sources, encompassing meta-analysis data from published GWAS, datasets from the UK Biobank (UKB), insights from the Neale lab, and summary data furnished by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC). Within the framework of a two-sample MR study, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) act as proxies for phenotypic and genetic Instrumental Variables (IVs). The chosen SNPs must meet three critical MR assumptions: first, they must exhibit a strong association with CM (Assumption 1); second, these SNPs should be independent of potential confounders that could influence the study outcomes (Assumption 2); and finally, there should be no direct causal pathway linking the instrumental variables and the study outcomes (Assumption 3) (Davies et al., 2018). The specific process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the three hypotheses of the MR study.

Note. Solid arrow lines indicate MR analysis processes and can only influence the outcome by exposure. Dashed arrows indicate instrumental variables independent of any confounding variables. IVW: inverse-variance weighted; LD: linkage disequilibrium; SNP: single-nucleotide polymorphism.

2.2. Data sources

This study utilised data from several large-scale GWAS to investigate the causal effects of CM on mental health outcomes. The meta-analysis incorporated data from 185,414 participants primarily of European descent, as summarised in the study by Warrier et al. (2021). Detailed information on the data sources, including sample size, age range, demographics, and measures of CM, is provided in Table 1. These data sources include well-established cohorts and consortia such as the UK Biobank, PGC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, and Generation R Study. Each organisation contributes valuable phenotypic and genetic data, collected with informed consent, and represents predominantly European descent populations. The CM measures vary across studies, employing tools like retrospective questionnaires, parent-reported data, and self-reported questionnaires, ensuring comprehensive and diverse data capture.

Table 1.

Overview of data sources for childhood maltreatment GWAS.

| Study | Sample size | Age range | Demographics | Inclusion criteria | Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank | 143,473 | 40–69 years | Predominantly European descent, balanced representation of sexes | Participants had phenotypic and genetic data, provided informed consent | Childhood maltreatment Screener (emotional, sexual, physical abuse, emotional and physical neglect) |

| PGC | 26,290 | Not specified | Predominantly European descent | Participants had phenotypic and genetic data, provided informed consent | Retrospective questionnaires on CM (sexual, physical, emotional abuse) |

| ALSPAC | 8,346 | Birth years 1991–1992 | Predominantly European descent | Participants had phenotypic and genetic data, provided informed consent | Parent-reported data using Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-PTSD and Children’s Report of Parental Behaviour Inventory |

| ABCD Study | 5,400 | Birth years 2006–2008 | Predominantly European descent | Participants had phenotypic and genetic data, provided informed consent | Multiple parent and self-reported questionnaires at different time points |

| Generation R Study | 1,905 | Birth years 2002–2006 | Predominantly European descent | Participants had phenotypic and genetic data, provided informed consent | Mother-reported data using Life Event and Difficulty Schedule |

Note. PGC: Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, ALSPAC: Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, ABCD Study: Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study.

The summary-level datasets for MDD and PTSD were obtained from the PGC. For MDD, the GWAS included 59,851 cases and 113,154 controls of European ancestry, utilising structured diagnostic interviews and medical records across multiple cohorts. For PTSD, the GWAS meta-analysis involved 23,212 cases and 151,447 controls of European ancestry, assessing PTSD based on DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and DSM-5 criteria. Both studies employed rigorous quality control measures and covariate adjustments for population stratification (Nievergelt et al., 2019; Wray et al., 2018). Complementary data for ANX, non-fatal self-harm, suicide attempts, age of onset, and the frequency of depressive episodes were obtained from the Neale Lab and the MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (MRC-IEU). These summary data sets include information from various GWAS, each identified by specific GWAS IDs. For instance, data sets from the Neale Lab and MRC-IEU provide comprehensive genetic and phenotypic data, with details such as sample size, SNP count, and population ancestry. All participants met DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-5, ICD-9, or ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for mental disorders. The study was confined to GWAS data from individuals of European descent, who had undergone ethical review and provided informed consent. Detailed information on the GWAS datasets is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary information of the GWAS database in the two-sample MR study.

| Phenotype | Data source | Sample size | nSNP | Population | PMID/GWAS ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood Maltreatment | UKB | 185,414 | 16,754,619 | European | 33740410 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | PGC | 173,005 | 13,554,550 | European | 29700475 |

| Anxiety | Neale Lab | 337,159 | 10,894,596 | European | ukb-a-82 |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder | PGC | 174,659 | 9,766,174 | European | 31594949 |

| Ever self-harmed | Neale Lab | 117,733 | 12,075,154 | European | ukb-d-20480 |

| Ever attempted suicide | Neale Lab | 4,933 | 10,941,854 | European | ukb-d-20483 |

| Age at first episode of depression | Neale Lab | 190,643 | 10,894,596 | European | ukb-d-20433_irnt |

| Number of depression episodes | MRC-IEU | 58,290 | 9,851,867 | European | ukb-b-1464 |

Note. UKB: UK Biobank; PGC: Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; MRC IEU: The MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; NA: Not applicable.

2.3. Selection of instrumental variables

The SNPs used as instrumental variables for CM met the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10−8) to satisfy Assumption 1. To obtain independent SNPs, linkage disequilibrium pruning was conducted (LD r2 < 0.001, kb > 10,000) (Shen et al., 2021). To further evaluate the strength of the instrumental variables, the F-statistic for each SNP was calculated, and those with F < 10, considered weak instrumental variables, were excluded (Burgess & Labrecque, 2018); the F-statistic was determined using the formula: F = [(N – k – 1)/k] × [R2/(1-R2)] (Burgess & Thompson, 2011), where R2 was computed as follows: R2 = 2 × (1 – MAF)×MAF × (β/SD)2 (Wu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021), In these formulas, N represents the sample size of the selected dataset, k is the total number of SNPs chosen for MR analysis, β is the effect estimate of the SNP on the measured variable, SD is the standard deviation of β, and MAF is the minor allele frequency.

2.4. Exclusion of confounding and palindromic SNPs

To adhere to the second assumption of Mendelian randomisation, each SNP and its associated phenotypes were assessed using the Phenoscanner V2 database (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/), and SNPs associated with traits related to MDD and ANX were excluded at an r2 threshold greater than 0.80 (Kamat et al., 2019; Staley et al., 2016). To harmonise the data for exposure and outcome, all palindromic SNPs with intermediate allele frequencies were removed from the selected SNPs (Lukkunaprasit et al., 2021). Palindromic SNPs have A/T or G/C alleles, and intermediate allele frequencies range between 0.01 and 0.30 (Cui et al., 2020).

2.5. Effect estimation and sensitivity analysis

Based on the list of SNPs determined by the established screening criteria, we employed the inverse-variance weighted (IVW), MR-Egger regression, and weighted median (WM) methods to conduct a comprehensive MR analysis to assess the causal relationship between CM and the incidence and symptoms of MDD, ANX and PTSD (Marouli et al., 2019). Given the potential pleiotropy of instrumental variables that might bias the results, we validated the robustness of the findings by comparing the effect estimates from these three MR methods. The IVW method assumes all SNPs are valid instrumental variables and combines the Wald ratios of each SNP for meta-analysis (Cui et al., 2020). Effect sizes are presented as odds ratios (OR) or regression coefficients (β) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). To satisfy the third assumption of MR, heterogeneity assessments and sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the potential impact of instrumental variable heterogeneity and pleiotropy on MR results. We estimated the heterogeneity among SNPs using the statistic and P-value from Cochran's Q test (Greco et al., 2015) and assessed the impact of removing different SNPs on the causal effect through leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to ensure the stability of the MR estimates (Burgess & Thompson, 2017). Additionally, the MR-Egger intercept test and MR-PRESSO global test were applied to assess pleiotropy and outliers, with MR-PRESSO also providing revised estimates after outlier removal (Verbanck et al., 2018). To enhance statistical rigour, we applied False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction to adjust for multiple comparisons, reducing the risk of type I errors. This adjustment ensures the significance and reliability of our findings across various hypotheses.

This study conducted all statistical analyses using the R statistical software (version 4.1.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The analysis utilised several packages, including ‘dev tools,’ ‘TwoSampleMR,’ ‘LDlinkR,’ and ‘MR-PRESSO.’ All statistical tests were two-sided. The results of the MR and sensitivity analyses were deemed statistically significant if the P-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Causal effect estimates from MR analysis

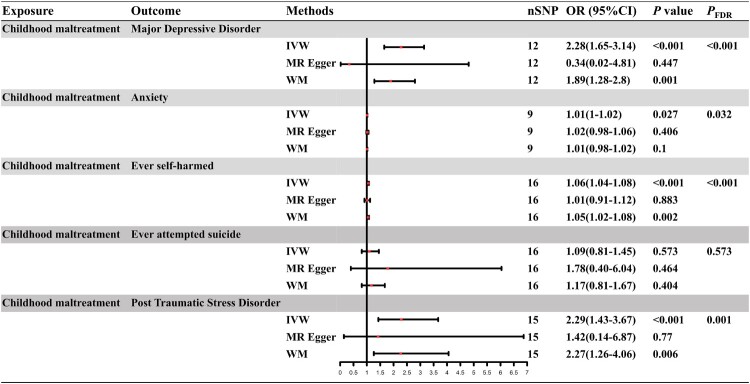

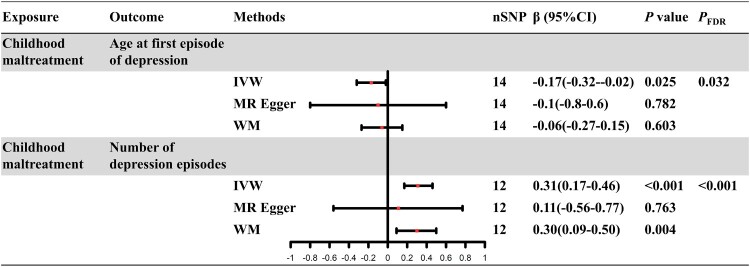

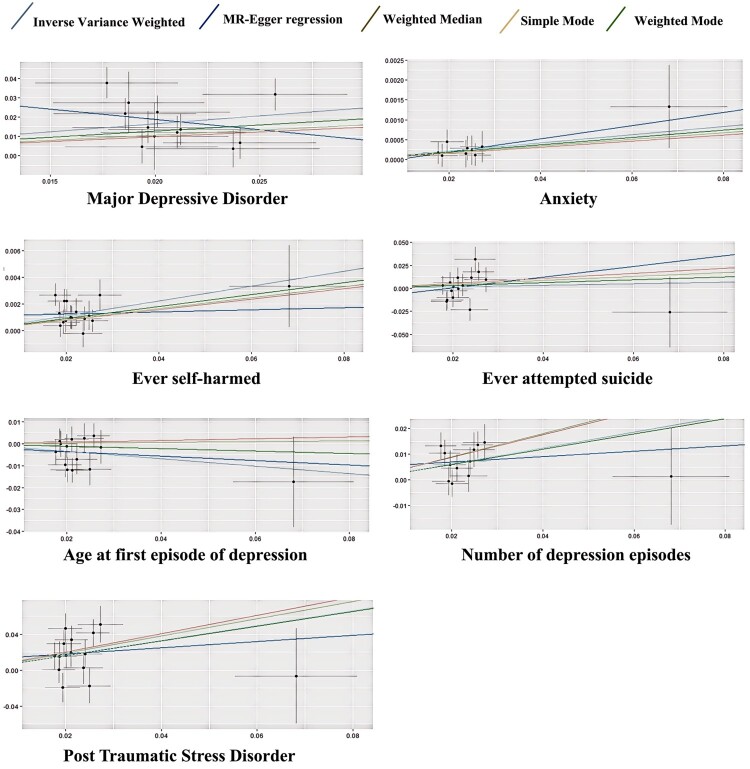

Following the defined screening criteria (P < 5 × 10−8, r² < 0.001, F > 10) and exclusion of potential confounders related to ANX and MDD, a total of 20 SNPs were included as instrumental variables for CM. After harmonising the datasets for MDD, ANX, PTSD, non-fatal self-harm, suicide attempts, age at onset of depression, and frequency of depressive episodes in the same direction and excluding palindromic SNPs, seven sets of instrumental variables were ultimately identified. The results indicated several potential causal links. For mental disorders, CM was significantly associated with an increased risk of MDD (OR = 2.28, 95% CI = 1.65–3.14, PFDR < .001), ANX (IVW: OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.00–1.02, PFDR = .032), and PTSD (IVW: OR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.43–3.67, PFDR = .001). Regarding behavioural outcomes, CM was significantly associated with Ever self-harmed (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.03–1.08, PFDR < .001), but not with Ever attempted suicide (IVW: OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.81–1.45, PFDR = .573). Additionally, for depressive episode characteristics, CM was significantly associated with the frequency of depressive episodes (IVW: β = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.17–0.46, PFDR < .001) and an earlier age of first onset of depression (IVW: β = −0.17, 95% CI = −0.32 to −0.02, PFDR = .033). Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate these causal relationships, and Figure 4 presents scatter plots using five different MR methods to validate these findings.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the causal relationships between CM and MDD, ANX, PTSD, non-fatal self-harm, and suicide attempts based on three MR methods.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the causal relationships between CM and the onset age of depression and the number of episodes, based on three MR methods.

Note. OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; IVW: inverse variance weighting; WM: weighted median; MR Egger: MR Egger regression; nSNP: number of single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 4.

Scatter Plot of MR on the Causal Effects of CM on MDD, ANX, PTSD, Non-fatal self-harm, Suicide Attempts, and the Age and Frequency of the First Depressive Episode.

Note. The horizontal x-axes indicate the genetic instruments linked to the exposure data, while the vertical y-axes represent the genetic instruments associated with the outcome data. The IVs employed in the MR analysis are indicated by black dots. Light blue: inverse-variance weighted; green: weighted-median estimator; deep blue: MR-Egger. As the inverse-variance weighted and weighted-median estimator methods produced highly similar estimates in the analysis, these figures exhibit a visual overlap.

3.2. Heterogeneity and pleiotropy

In our MR analysis, we evaluated heterogeneity and pleiotropy to ensure the robustness and validity of our results. The MR-Egger regression test showed no significant pleiotropy for all outcomes, including MDD, ANX, PTSD, non-fatal self-harm, suicide attempts, age of depression onset, and number of depressive episodes. Cochran’s Q test indicated no significant heterogeneity among genetic instruments for these outcomes. Additionally, the MR-PRESSO global test found no significant pleiotropy. These results suggest no significant evidence of pleiotropy or heterogeneity, supporting the validity of our MR analyses in establishing causal relationships between CM and various mental health outcomes. Regarding the statistical strength and power of the selected SNPs, the calculated F-statistics ranged from 132.45 to 222.17, with all power estimates exceeding 80%, well above the conventional thresholds (F > 10, Power > 80%). The specific results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of heterogeneity, pleiotropy, and statistical strength tests.

| Outcome | MR-Egger regression | Cochran’s Q | MR-PRESSO | R2(%) | F | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egger intercept | P value | Q value | P value | Global test P value | |||

| MDD | .04 | .188 | 16.34 | .09 | .085 | .11 | 203.45 |

| ANX | <−.01 | .74 | 1.4 | .986 | .99 | .06 | 132.45 |

| PTSD | .01 | .679 | 21.41 | .092 | .113 | .11 | 216.52 |

| Ever self-harmed | <−.01 | .368 | 12.14 | .595 | .654 | .12 | 221.17 |

| Ever attempted suicide | −.01 | .522 | 19.95 | .132 | .169 | .12 | 221.16 |

| Age of depression | <−.01 | .848 | 23.05 | .442 | .542 | .09 | 166.87 |

| Number of depression | <−.01 | .547 | 1.65 | .386 | .482 | .12 | 221.17 |

Note. MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; ANX: Anxiety Disorders; PTSD: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; MR-PRESSO: Mendelian Randomisation Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier.

4. Discussion

This study utilises Mendelian randomisation to scrutinise GWAS data, revealing potential causal links between CM and the emergence of several mental health outcomes, including MDD, PTSD, ANX, Non-fatal self-harm tendencies, as well as the age and frequency of depression onset. Sensitivity analyses, including tests for pleiotropy and heterogeneity, were performed to ensure the robustness and impartiality of the results derived from IVW.

Our MR study aligns with previous research findings, showing that various forms of maltreatment (emotional maltreatment and neglect, physical maltreatment and neglect, and sexual maltreatment) are highly correlated with the ORs for MDD, PTSD, and ANX (Nanni et al., 2012; Norman et al., 2012). Specifically, emotional maltreatment shows a significant link to depression, although its impact is relatively minor compared to other forms of maltreatment. Some studies suggest that the association between emotional maltreatment and depressive disorders is more potent than that with sexual or physical maltreatment (Choi et al., 2017; Remigio-Baker et al., 2014). Emotional maltreatment has also been strongly linked to PTSD, with evidence indicating that individuals who experience emotional abuse are at a heightened risk of developing PTSD symptoms (Wiersma et al., 2009).

One theory suggests that emotional maltreatment is often perpetrated by individuals from whom the victim expects love and respect, and the violation of this expectation may lead to more severe emotional maltreatment than other forms of maltreatment (Gibb & Alloy, 2006). Existing research supports this theory, indicating that emotional maltreatment is strongly associated with a range of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Spinazzola et al., 2014; Taillieu et al., 2016). Taillieu et al. (2016) found that individuals who experienced emotional maltreatment in childhood had significantly higher rates of mental disorders in adulthood compared to those who experienced other forms of maltreatment. Similarly, Spinazzola et al. (2014) highlighted that emotional maltreatment has a profound impact on emotional regulation and can lead to long-term psychological difficulties. Another theory posits that negative cognitive and emotion regulation strategies mediate the impact of CM on the onset of MDD, ANX, and PTSD (Huh et al., 2017). This suggests that the use of maladaptive cognitive and emotion regulation strategies is a key mechanism by which CM adversely affects the severity of these mental health disorders in adulthood. These findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that emotion regulation mediates the adverse effects of CM (Kim & Cicchetti, 2010) and that CM can lead to emotion dysregulation later in life (Cloitre et al., 2009). Furthermore, the biological sequelae of CM, such as elevated levels of inflammation, are evident in mental health disorders like MDD, ANX, and PTSD (Baumeister et al., 2016; Peirce & Alviña, 2019). Studies have shown that individuals with a history of maltreatment and mood disorders exhibit more pronounced inflammatory responses compared to those without mood disorders (Danese et al., 2011; Miller & Cole, 2012; Slavich & Irwin, 2014). For instance, individuals with both CM and depression have significantly higher levels of inflammation compared to those with only depression, only CM, or neither. This heightened inflammatory response may contribute to the increased risk and severity of psychological disorders (Danese et al., 2011). Given the relative scarcity of research on emotional maltreatment (Scott et al., 2012), further studies are needed to clarify the mechanistic relationships between emotional maltreatment and the onset and symptoms of mood disorders.

Furthermore, a study conducted in China indicated that CM is a significant precursor to non-suicidal non-fatal self-harm, with difficulties in emotion regulation and depression as the primary mediating factors (Hu et al., 2023). In our MR analysis, we examined the age of onset and the frequency of depressive episodes related to CM. We used MR-PRESSO tests after bidirectional correction and excluded outlier SNPs to ensure the stability of the IVW method. The results suggest that CM significantly increases the incidence of non-fatal self-harm but found no causal link between CM and suicide attempts (OR = 1.09, PFDR = 0.573), which contrasts with some previous studies (Angelakis et al., 2019; Huang & Hou, 2023; Norman et al., 2012) and warrants further investigation. It is noteworthy that some research indicates the current emotional state can influence the reporting of abusive behaviours, as shown by higher median scores for MDD and ANX among participants with a history of maltreatment (including emotional, physical, and sexual maltreatment) compared to those without such a history (Hosang et al., 2023).

Our findings have several important clinical implications. The robust causal evidence linking CM to MDD, ANX, PTSD, and Non-fatal self-harm underscores the need for early identification and intervention in children who have experienced maltreatment. Clinicians should be vigilant in screening for a history of CM in patients presenting with these mental health disorders and consider early intervention strategies such as cognitive–behavioural therapies focused on emotion regulation and cognitive restructuring to mitigate long-term psychological impacts. The inconsistency between our findings and previous research regarding suicide attempts highlights the need for further investigation. A multidisciplinary approach, integrating psychological and medical interventions, is essential to improve long-term outcomes. Future research should explore these complex relationships, including the role of genetic predisposition and intergenerational trauma, and develop targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of CM on mental health. Addressing these areas will enhance our understanding and treatment of the psychological and biological consequences of CM.

5. Advantages and limitations

The strength of this study lies in its use of a large sample size from GWAS summary data sets, which significantly reduces confounding factors and reverse causation biases compared to observational studies, thereby enhancing the stability of the causal effect estimates. Additionally, the use of MR methods allows for a more robust inference of causality by leveraging genetic instruments to minimise the impact of confounders.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, our research subjects were exclusively of European descent, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups. Secondly, the reliance on retrospective self-report measures for CM may introduce recall bias and affect data accuracy. Additionally, important variables such as socioeconomic status and environmental factors were not included, which could influence the results. Our sample consisted only of individuals who met criteria for mental disorders, potentially introducing selection bias and limiting the generalizability of our findings to the broader population. Furthermore, the role of genetic predisposition and the intergenerational transmission of trauma in the development of mental disorders following CM was not fully explored. The potential for parents with mental disorders to pass on genetic vulnerabilities and create stressful environments that confound the risk of mental disorders in their children warrants further investigation. The original datasets lacked detailed subtypes of CM, such as emotional maltreatment and neglect, physical maltreatment and neglect, and sexual maltreatment, which could provide more nuanced insights into the specific impacts of different forms of CM. Although we conducted tests to minimise pleiotropic effects of the genetic instruments used in MR analysis, future research should focus on developing and validating instruments with minimal pleiotropy to strengthen causal inferences. Addressing these limitations will enhance the robustness and applicability of our findings.

6. Future directions

Future research should replicate these findings in diverse populations to enhance generalizability. Longitudinal studies with prospective data collection could reduce recall bias from retrospective self-reports. Including variables such as environmental and socioeconomic factors would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between CM and mental health outcomes. Additionally, future studies should consider the role of genetic predisposition and intergenerational trauma, given that many children who experience maltreatment have parents with mental disorders, potentially confounding results. Incorporating these factors into MR analyses will help clarify the interplay between genetics and environmental stressors. Finally, developing genetic instruments with minimal pleiotropy will strengthen causal inferences from MR analyses. Addressing these areas will improve our understanding of CM's impact on mental health and guide targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC), Neale Lab and UK Biobank researchers for providing GWAS data.

Funding Statement

This work received support from the Development of an Intelligent System for the Diagnosis and Treatment Assistance of Psychiatric Disorders [grant number KJZD-K202400410]. The study funders/sponsors played no role in the design and execution of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Authors’ contributions

Zheng Zhang and Yuanzhi Ju made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, as well as the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Xinglian Wang, Jiazheng Li, and Yating Wang provided critical intellectual revisions. Qinghua Luo, Chenggang Jiang, and Haitang Qiu significantly contributed to drafting the work and critically revising it for important intellectual content. Chenggang Jiang also participated in the manuscript modifications. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Data availability statement

The data utilised in this study were sourced from publicly accessible repositories and published studies: CM Exposure Data: Derived from the meta-analysis by Warrier et al. (2021), accessible via the Cambridge Data Repository. Mental Health Outcome Data: Obtained from open-access databases, including the IEU Open GWAS (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/) and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) (https://pgc.unc.edu/for-researchers/download-results/). All datasets are publicly available and can be accessed following the respective repository guidelines.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval had been obtained in all original studies. We used publicly available summary data from original studies so that no ethical approval is required for this study.

Transparency statement

In this manuscript, we employed the same datasets and statistical models as those used in our previous study, ‘Exploring the causal link between Childhood Maltreatment and Asthma: A Mendelian randomization study’ (Ref.: Ms. No. ZEPT-2024-0144). This approach ensures analytical consistency and facilitates comparative interpretation of our findings.

References

- Abajobir, A. A., Kisely, S., Scott, J. G., Williams, G., Clavarino, A., Strathearn, L., & Najman, J. M. (2017). Childhood maltreatment and young adulthood hallucinations, delusional experiences, and psychosis: A longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(5), 1045–1055. 10.1093/schbul/sbw175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis, I., Gillespie, E. L., & Panagioti, M. (2019). Childhood maltreatment and adult suicidality: A comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(7), 1057–1078. 10.1017/S0033291718003823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiden, P., Stewart, S. L., & Fallon, B. (2017). The role of adverse childhood experiences as determinants of non-suicidal self-injury among children and adolescents referred to community and inpatient mental health settings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 163–176. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, D., Akhtar, R., Ciufolini, S., Pariante, C. M., & Mondelli, V. (2016). Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: A meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(5), 642–649. 10.1038/mp.2015.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Ramos Rodriguez, G., Sethi, D., & Passmore, J. (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4(10), e517–e528. 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S., & Labrecque, J. A. (2018). Mendelian randomization with a binary exposure variable: Interpretation and presentation of causal estimates. European Journal of Epidemiology, 33(10), 947–952. 10.1007/s10654-018-0424-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S., Thompson, S. G., & CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration . (2011). Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(3), 755–764. 10.1093/ije/dyr036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S., & Thompson, S. G. (2017). Erratum to: Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. European Journal of Epidemiology, 32(5), 391–392. 10.1007/s10654-017-0276-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . (2024, July 11). About child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/about/index.html.

- Charlton, B. M., Roberts, A. L., Rosario, M., Katz-Wise, S. L., Calzo, J. P., Spiegelman, D., & Austin, S. B. (2018). Teen pregnancy risk factors among young women of diverse sexual orientations. Pediatrics, 141(4), e20172278. 10.1542/peds.2017-2278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N. G., DiNitto, D. M., Marti, C. N., & Choi, B. Y. (2017). Association of adverse childhood experiences with lifetime mental and substance use disorders among men and women aged 50+ years. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(3), 359–372. 10.1017/S1041610216001800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M., Stolbach, B. C., Herman, J. L., van der Kolk, B., Pynoos, R., Wang, J., & Petkova, E. (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399–408. 10.1002/jts.20444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z., Hou, G., Meng, X., Feng, H., He, B., & Tian, Y. (2020). Bidirectional causal associations between inflammatory bowel disease and ankylosing spondylitis: A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Frontiers in Genetics, 11, 587876. 10.3389/fgene.2020.587876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese, A., Caspi, A., Williams, B., Ambler, A., Sugden, K., Mika, J., Werts, H., Freeman, J., Pariante, C. M., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2011). Biological embedding of stress through inflammation processes in childhood. Molecular Psychiatry, 16(3), 244–246. 10.1038/mp.2010.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V., & Davey Smith, G. (2018). Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ, 362, k601. 10.1136/bmj.k601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, B. E., & Alloy, L. B. (2006). A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 264–274. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, L. K., Breiding, M. J., Merrick, M. T., Thompson, W. W., Ford, D. C., Dhingra, S. S., & Parks, S. E. (2015). Childhood adversity and adult chronic disease: An update from ten states and the district of Columbia, 2010. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(3), 345–349. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, D., Bethencourt Mirabal, A., & McCall, J. D. (2024). Child abuse and neglect. In Statpearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459146/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco, M. F. D., Minelli, C, Sheehan, N. A., & Thompson, R. J. (2015). Detecting pleiotropy in Mendelian randomisation studies with summary data and a continuous outcome. Statistics in Medicine, 34(21), 2926–2940. 10.1002/sim.6522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosang, G. M., Manoli, A., Shakoor, S., Fisher, H. L., & Parker, C. (2023). Reliability and convergent validity of retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment by individuals with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research, 321, 115105. 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C., Huang, J., Shang, Y., Huang, T., Jiang, W., & Yuan, Y. (2023). Child maltreatment exposure and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The mediating roles of difficulty in emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(1), 16. 10.1186/s13034-023-00557-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M., & Hou, J. (2023). Childhood maltreatment and suicide risk: The mediating role of self-compassion, mentalization, depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 341, 52–61. 10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh, H. J., Kim, K. H., Lee, H.-K., & Chae, J.-H. (2017). The relationship between childhood trauma and the severity of adulthood depression and anxiety symptoms in a clinical sample: The mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 44–50. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat, M. A., Blackshaw, J. A., Young, R., Surendran, P., Burgess, S., Danesh, J., Butterworth, A. S., & Staley, J. R. (2019). Phenoscanner V2: An expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics (oxford, England), 35(22), 4851–4853. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C., Street, C., & Building, M. E. S. (2019). Child maltreatment 2019. Child Maltreatment. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(6), 706–716. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, R. E., Pinto Pereira, S. M., Li, L., & Danese, A. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences and adult inflammation: Single adversity, cumulative risk and latent class approaches. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 820–830. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, M., D’Arcy, C., & Meng, X. (2016). Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychological Medicine, 46(4), 717–730. 10.1017/S0033291715002743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Tu, L., & Jiang, X. (2022). Childhood maltreatment affects depression and anxiety: The mediating role of benign envy and malicious envy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 924795. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.924795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R. T., Scopelliti, K. M., Pittman, S. K., & Zamora, A. S. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(1), 51–64. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30469-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukkunaprasit, T., Rattanasiri, S., Ongphiphadhanakul, B., McKay, G. J., Attia, J., & Thakkinstian, A. (2021). Causal associations of urate With cardiovascular risk factors: Two-sample Mendelian randomization. Frontiers in Genetics, 12, 687279. 10.3389/fgene.2021.687279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin, T. J., Lewinson, R. E., Hayden, J. A., Mahood, Q., Rossi, M. A., Rosenbloom, B., & Katz, J. (2021). A systematic review of the prospective relationship between child maltreatment and chronic pain. Children, 8(9), 806. 10.3390/children8090806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marouli, E., Del Greco, M. F., Astley, C. M., Yang, J., Ahmad, S., Berndt, S. I., Caulfield, M. J., Evangelou, E., McKnight, B., Medina-Gomez, C., van Vliet-Ostaptchouk, J. V., Warren, H. R., Zhu, Z., Hirschhorn, J. N., Loos, R. J. F., Kutalik, Z., & Deloukas, P. (2019). Mendelian randomisation analyses find pulmonary factors mediate the effect of height on coronary artery disease. Communications Biology, 2(1), 119. 10.1038/s42003-019-0361-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, K. A., Weissman, D., & Bitrán, D. (2019). Childhood adversity and neural development: A systematic review. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1(1), 277–312. 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-084950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. E., & Cole, S. W. (2012). Clustering of depression and inflammation in adolescents previously exposed to childhood adversity. Biological Psychiatry, 72(1), 34–40. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni, V., Uher, R., & Danese, A. (2012). Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(2), 141–151. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J., Klumparendt, A., Doebler, P., & Ehring, T. (2017). Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(2), 96–104. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievergelt, C. M., Maihofer, A. X., Klengel, T., Atkinson, E. G., Chen, C.-Y., Choi, K. W., Coleman, J. R. I., Dalvie, S., Duncan, L. E., Gelernter, J., Levey, D. F., Logue, M. W., Polimanti, R., Provost, A. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Stein, M. B., Torres, K., Aiello, A. E., Almli, L. M., … Koenen, K. C. (2019). International meta-analysis of PTSD genome-wide association studies identifies sex- and ancestry-specific genetic risk loci. Nature Communications, 10(1), 4558. 10.1038/s41467-019-12576-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 9(11), e1001349. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, J. M., & Alviña, K. (2019). The role of inflammation and the gut microbiome in depression and anxiety. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 97(10), 1223–1241. 10.1002/jnr.24476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingault, J.-B., O’Reilly, P. F., Schoeler, T., Ploubidis, G. B., Rijsdijk, F., & Dudbridge, F. (2018). Using genetic data to strengthen causal inference in observational research. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19(9), 566–580. 10.1038/s41576-018-0020-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remigio-Baker, R. A., Hayes, D. K., & Reyes-Salvail, F. (2014). Adverse childhood events and current depressive symptoms among women in Hawaii: 2010 BRFSS, Hawaii. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(10), 2300–2308. 10.1007/s10995-013-1374-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., Smith, D. A. R., & Ellis, P. M. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: Comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(6), 469–475. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J., Zhou, H., Liu, J., Zhang, Y., Zhou, T., Yang, Y., Fang, W., Huang, Y., & Zhang, L. (2021). A modifiable risk factors atlas of lung cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. Cancer Medicine, 10(13), 4587–4603. 10.1002/cam4.4015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields, M. E., Hovdestad, W. E., Pelletier, C., Dykxhoorn, J. L., O’Donnell, S. C., & Tonmyr, L. (2016). Childhood maltreatment as a risk factor for diabetes: Findings from a population-based survey of Canadian adults. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 879. 10.1186/s12889-016-3491-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich, G. M., & Irwin, M. R. (2014). From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 774–815. 10.1037/a0035302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. E., & Pollak, S. D. (2020). Early life stress and development: Potential mechanisms for adverse outcomes. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 12(1), 34. 10.1186/s11689-020-09337-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola, J., Hodgdon, H., Liang, L.-J., Ford, J. D., Layne, C. M., Pynoos, R., Briggs, E. C., Stolbach, B., & Kisiel, C. (2014). Unseen wounds: The contribution of psychological maltreatment to child and adolescent mental health and risk outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(Suppl 1), S18–S28. 10.1037/a0037766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staley, J. R., Blackshaw, J., Kamat, M. A., Ellis, S., Surendran, P., Sun, B. B., Paul, D. S., Freitag, D., Burgess, S., Danesh, J., Young, R., & Butterworth, A. S. (2016). Phenoscanner: A database of human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics (oxford, England), 32(20), 3207–3209. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suglia, S. F., Koenen, K. C., Boynton-Jarrett, R., Chan, P. S., Clark, C. J., Danese, A., Faith, M. S., Goldstein, B. I., Hayman, L. L., Isasi, C. R., Pratt, C. A., Slopen, N., Sumner, J. A., Turer, A., Turer, C. B., Zachariah, J. P., & American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research . (2018). Childhood and adolescent adversity and cardiometabolic outcomes: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 137(5), e15–e28. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taillieu, T. L., Brownridge, D. A., Sareen, J., & Afifi, T. O. (2016). Childhood emotional maltreatment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative adult sample from the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59, 1–12. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbanck, M., Chen, C.-Y., Neale, B., & Do, R. (2018). Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nature Genetics, 50(5), 693–698. 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrier, V., Kwong, A. S. F., Luo, M., Dalvie, S., Croft, J., Sallis, H. M., Baldwin, J., Munafò, M. R., Nievergelt, C. M., Grant, A. J., Burgess, S., Moore, T. M., Barzilay, R., McIntosh, A., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Cecil, C. A. M. (2021). Gene-environment correlations and causal effects of childhood maltreatment on physical and mental health: A genetically informed approach. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(5), 373–386. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30569-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2020). Child maltreatment. Retrieved January 26, 2024, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment

- Wiersma, J. E., Hovens, J. G. F. M., Oppen, P. van, Giltay, E. J., Schaik, D. J. F. van, & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2009). The importance of childhood trauma and childhood life events for chronicity of depression in adults. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(7), 983–989. 10.4088/JCP.08m04521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray, N. R., Ripke, S., Mattheisen, M., Trzaskowski, M., Byrne, E. M., Abdellaoui, A., Adams, M. J., Agerbo, E., Air, T. M., Andlauer, T. M. F., Bacanu, S.-A., Bækvad-Hansen, M., Beekman, A. F. T., Bigdeli, T. B., Binder, E. B., Blackwood, D. R. H., Bryois, J., Buttenschøn, H. N., Bybjerg-Grauholm, J., … Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . (2018). Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nature Genetics, 50(5), 668–681. 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.-F., Zhang, W., Zhang, X., & Zhang, R. (2020). Application and interpretation of Mendelian randomization approaches in exploring the causality between folate and coronary artery disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 111(6), 1299–1300. 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S., Xiong, Y., & Larsson, S. C. (2021). An atlas on risk factors for multiple sclerosis: A Mendelian randomization study. Journal of Neurology, 268(1), 114–124. 10.1007/s00415-020-10119-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilised in this study were sourced from publicly accessible repositories and published studies: CM Exposure Data: Derived from the meta-analysis by Warrier et al. (2021), accessible via the Cambridge Data Repository. Mental Health Outcome Data: Obtained from open-access databases, including the IEU Open GWAS (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/) and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) (https://pgc.unc.edu/for-researchers/download-results/). All datasets are publicly available and can be accessed following the respective repository guidelines.