Abstract

Servant leadership in the workplace involves providing services and cultivating trust amongst subordinates. However, leadership dynamics can be distorted when hospitality frontline managers assume leadership roles by strictly adhering to top management strategic directives. This study aims to examine how constraints imposed by top management influence the management styles of frontline managers within the hospitality industry. The current study delved into the interplay amongst servant leadership, employee wellbeing and retention, highlighting the pivotal role of service climate, procedural justice and customer satisfaction as moderating variables. In this research, partial least squares structural equation modelling was used to test the research model, using data collected from 485 respondents. Findings underscore the critical role of hospitality frontline managers in aligning with organisational strategic directives, a requirement that may compromise their servant leadership style. Poor service climate and procedural justice may result from this alignment. The current study emphasises that strictly adhering to predetermined top management decisions can influence the outcomes of servant leadership—an often-overlooked factor in existing research. Lastly, this research enriches the literature on the effect of servant leadership on employee retention.

1. Introduction

Hospitality is a labour-intensive industry [1], and the wellbeing and retention of employees is critical to business operations and performance. Generally, the voluntary turnover rate in the hotel industry is always higher than that in other sectors, typically ranging from 30% to 300%. In China, the average turnover rate across all industries is about 20%, whilst the voluntary turnover rate in the hotel industry reaches as high as 40%, which is the highest in the country [2]. The hospitality industry faces high employee turnover and poor employee wellbeing [3], thereby posing a challenge to the sustainable development of businesses [4,5].

Empirical studies within the hospitality industry focus on the correlation between frontline managers and their leadership styles. However, a significant gap exists on the influence of top management on the service climate and procedural justice, thereby impacting the leadership attitudes and behaviour of hospitality frontline managers [6–8].

Given that the focus shifts towards compliance with top management directives, a growing body of research has explored how servant leadership influence employees’ job satisfaction, health wellbeing and loyalty to the organisation [9,10]. However, the impact of top management’s constraints on servant leadership and its subsequent effect on employee retention remains underexplored. When frontline managers are unable to practice servant leadership owing to top management’s directives, it can lead to decreased employee wellbeing and increased turnover intentions [9,11]. Studies have found that the suppression of servant leadership can lead to a decline in managerial performance and disrupt daily organisational operations [9]. This decline in performance can further impact employee wellbeing and retention because employees may feel unsupported and undervalued.

Notably, employee satisfaction and retention are also influenced by the organisational climate [12]. Hospitality industry problems often exist and caused by top management failing to utilise organisational resources to meet frontline managers and employees’ needs [13]. Although frontline hotel managers have certain freedom to implement a servant leadership style in practice, they still need to follow the organisational norms and standards of practice set by top management. Many research empirical findings exhibit hospitality support, possibly affecting leadership style in achieving negative or positive results [14]. However, such findings disregard the idea that service climate and procedural justice can influence managers’ leadership approach and their ability to cultivate trust amongst their employees [15].

Previous studies [16–18] have discussed servant leadership within the hospitality sector and the hindrances posed by the service environment under top management [19–21]. However, some studies have focused on leadership styles’ positive aspects, overlooking such antecedents as top management norms and organisational decisions, which may cause frontline managers to misinterpret management styles [22]. Furthermore, previous studies [23–25] have also confirmed that procedural fairness affects employees’ job satisfaction and their decisions to stay or leave a job, which is related to leader behavior [26,27]. Therefore, this study explores how top managers’ influence on frontline managers alters their management approach and perceptions of service climate and procedural justice, and how these changes affect their servant leadership style [28–30].

The guidance provided by top management influences service climate and procedural justice within organisations, thereby shaping leadership styles [7,31,32]. Moreover, organisational cues emphasising additional job demands and expectations from top management could diminish frontline managers’ leadership efficacy and conduct [9]. According to early social learning theory [33], employees tend to emulate the work behaviour of role models in the work environment. Therefore, frontline managers likely emulate the attitudes and behaviours of top management, integrating them into the organisation’s acceptable work attitudes.

This study uses top management decision-making as a context and examines how frontline servant leadership, moderated by service climate and procedural justice, affects the wellbeing and retention of junior employees. The results show that frontline managers’ servant leadership style may be compromised by top management’s restrictions. This compromise could eventually affect employees’ wellbeing and retention. This study fills in the aforementioned research gap.

This study provides the following objectives to guide this research:

-

(1)

reveal the relationship between servant leadership and employee wellbeing and retention as measured in the service industry;

-

(2)

investigate whether or not service climate and procedural justice serve as a moderator in the relationship between servant leadership and employees’ wellbeing; and

-

(3)

explore whether or not customer satisfaction serves as a moderator in the relationship between employee wellbeing and retention.

The current study delves into three messages, namely, contributing knowledge of management, psychological studies and human resources management, thereby enhancing the overall value of this research. Theoretical insights are refined by exploring the impact of servant leadership dimensions on employee wellbeing and retention based on leader–member-exchange (LMX) theory and role theory. By integrating and extending these theories, this study advances the dissemination of leadership knowledge and strengthens the foundation of servant leadership research, thereby filling in existing gaps in the field.

2. Literature review and hypothesis

2.1. LMX and role theories

LMX theory and role theory guided this article [34,35]. LMX theory lies in the concept that leaders form trusting, solid, emotional and respect-based relationships with specific team members, potentially increasing interpersonal relationships [36]. Note that LMX theory, which emphasises the quality of relationship between leaders and members and its impact on employee behavior and attitudes, is highly relevant to this study’s focus on the impact of servant leadership on employee wellbeing and retention. Many studies have underscored the need to enhance employee satisfaction through leadership practices. This enhancement can ultimately contribute to employee turnover rate reduction [37–39]. Some researchers have also indicated that servant leadership serves as a mechanism to cultivate organisational citizenship, strengthen commitment and reduce high turnover from the LMX theory perspective [40].

Biddle [41] firstly introduced role theory from cognitive social psychology. The ‘roles’ represent the share of normative expectations and define particular social positions and corresponding behaviour [41]. As the concept of servant leadership evolves, frontline managers assume leadership roles and also adhere to the strategic guidance provided by top management, thereby integrating their management style into the organisational framework. Frontline managers adopt their social norms and special roles based on cues from top management’s expectations [9]. Frontline managers differ from top management and come in various types. The latter may sacrifice employees’ wellbeing and decision-making for their own benefits [42]. Role theory can explain how leadership behaviours can influence employees’ perceptions and behaviours, especially under top management constraints, in which servant leaders may be unable to maximise their positive roles. Therefore, we anticipate that role theory will be the most suitable framework for incorporating our proposed model. This theory can effectively justify how service climate and procedural justice are associated with servant leadership.

2.2. Top management and servant leadership

Top management comprises senior executives and managing directors managing organisations [22,43]. They manipulate the service climate and procedural justice and shape frontline managers’ leadership style. They create visibility and power for the followers. Therefore, we propose top management norms and code of ethics and mould the service climate and justice in organisations that help interpret and develop the leadership style of frontline managers [44]. However, top management can also pressure frontline leaders [45].

Servant leadership is one type of frontline leadership. Canavesi and Minelli [46] defined servant leadership as a leadership philosophy and practice centred on prioritising the interests of those led over the leaders’ own. This leadership underscores the importance of leaders’ actions being geared more towards fostering the gains of subordinates than leaders’ concerns. Servant leadership entails assisting subordinates, establishing trust and inspiring them to follow leaders [8]. Corresponding with LMX theory [36], offering motivational and supportive resources to employees is an important component of increasing employee engagement. This importance coincides with the management characteristics of servant leadership. Once employees feel invested in their leaders at work, they become more loyal to organisations and less inclined to leave.

Leader personality is positively correlated with employees’ perceptions of an atmosphere of procedural justice [47], and employees use procedural justice as a signal to determine whether or not their leaders value them [48]. However, low servant leadership may change their perception of the followers rather than serve to achieve the organisations’ mission [49]. Therefore, this study chose servant leadership as the research object.

2.3. Overview of hypothesis development

Relevant leadership can provide meaningful support for employees’ basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness to promote employees’ self-regulation and satisfy followers’ autonomy needs through empowerment [31,50].

Empirical research has highlighted that wellbeing psychology links to employees’ satisfaction and organisations’ management of emotionally healthy workplaces [51]. Servant leaders’ emotionally healing behaviours can also satisfy followers’ need for relatedness, thereby enabling them to feel understood and appreciated by recognising and connecting with their situations and emotional distress [52]. Conversely, low servant leadership may affect employees’ wellbeing.

Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Low servant leadership has a negative effect on employees’ wellbeing.

Extensive evidence has shown that employee wellbeing affects a variety of performance indicators, including productivity, employee turnover, job satisfaction, job security, rewards and recognition, stress and work–life balance [53,54]. These indicators are related to the antecedents of employee retention [53]. DiPietro et al. [55]showed that workplace wellbeing significantly affects turnover intentions when moderated by positive affective commitment, negative affective commitment; and job satisfaction when moderated by positive affective commitment. Moreover, workplace wellbeing significantly affects turnover intentions. This finding relatively confirms the model of employee wellbeing factors and employee retention rate proposed by Gelencsér et al. [56]. Therefore, employee wellbeing can be a corporate contributor to employee retention. This study proposes the following hypothesis based on the findings on employee wellbeing and employee retention:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Low employee wellbeing has a negative effect on employee retention.

Service climate refers to the service-focused policies, practices and procedures people experience in their work units and the behaviours they observe as being rewarded, supported and expected [57]. This climate comprises interactions amongst employees, and the format and quality of these interactions are the basic manifestations of forming a service atmosphere. A discussion exhibits the consequences of attitudes, organisational citizenship behaviour and service performance influenced by service climates [58,59]. If the organisation performance and climate are weak, then leaders perceive negative supportive service organisations, which will affect their performance and employee satisfaction. Conversely, strong and positive service climates may share the perception of reward and support and can predict positive outcomes [60]. Veld and Alfes [61] confirmed that employee wellbeing can be improved by creating a happy atmosphere. Conversely, poor service climate affect servant leadership and employee wellbeing. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Service climate serves as a moderator in the relationship between servant leadership and employee wellbeing.

Procedural justice refers to the perception that the processes and procedures used by organisations to achieve significant results are fair and justice [62,63]. This type of justice is part of the multidimensional justice structure, including distributive, procedural, informational and interpersonal justice [64]. Leader personality is positively related to employees’ perceptions of procedural justice climate [65], and employees will use procedural justice as a signal to judge whether or not leaders value them [66]. Frontline managers adopt the request from top management; complying with organisations’ expectations may harm employees’ well-being. Therefore, procedural injustice may be related to low servant leadership and employees’ psychological wellbeing.

The relationship between procedural justice and employee wellbeing is considered across various disciplines [67]. A link has been found between employees’ perceptions of procedural injustice and different health problems after experiencing chronic stress processes. The lack of control over procedures, rules, work and decision-making processes will increase employee anxiety, thereby negatively impacting employee wellbeing [68,69]. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Procedural justice is a moderator in the relationship between servant leadership and employee wellbeing.

Customer satisfaction refers to the degree of satisfaction customers express after the service delivery process [70]. When service providers are highly committed to their role in the service process, they are likely to be motivated to continue to provide satisfactory service to customers. Frey et al. [71] showed that customer satisfaction significantly impacts the satisfaction and subjective wellbeing of corporate employees and is an important factor in improving employee retention rates. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Customer satisfaction is a moderator in the relationship between employee wellbeing and employee retention.

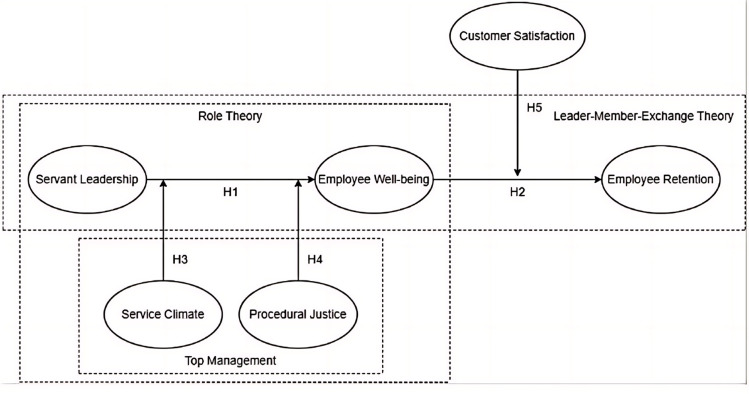

The proposed hypotheses form the research model, as shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and design

This study was designed using a quantitative research method. Quantitative methods are most conducive to testing existing theories and hypotheses, which can quantify the research objects and correlations within them [72]. Accordingly, this study used the Servant Leadership Measurement Scale and the Employee Well-being Measurement Scale that other researchers constructed and validated [73,74]. This research adopted judgemental sampling and collected data from the hospitality industry’s frontline employees in China [75]. The respondents primarily represent hotel frontline departments. The questionnaire was distributed from 1 June to 31 August 2024. The questionnaire was distributed to the human resources departments through personal connections and delivered to the respondents. All respondents signed a written form of informed consent and participated in this survey after understanding the purpose of the study and their rights. This questionnaire is anonymous because it focuses on employees’ views on companies’ leadership and career plans. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the City University of Macao. The research procedure follows the purpose of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The questionnaire contents adopted back translation to provide credibility [76]. A total of 550 questionnaires were sent, 509 of which were collected, for a response rate of 92.5% [77]. The total of valid questionnaires was 485, and the effective questionnaire response rate was 88%. We adopted Smart-PLS4 software to explore the relationship between constructs.

3.2. Measures

This study adopted well-developed scales to measure all the aforementioned constructs. A five-point Likert scale was used to evaluate each construct.

Servant leadership.

Van Dierendonck [78] developed the servant leadership measurement scale, which comprises eight dimensions: empowerment, support, responsibility, understanding, courage, authenticity, humility and stewardship. The current study focused solely on the leadership perceptions of frontline managers, rather than those of other individual employees. This focus is justified by the findings of Ling [79], demonstrating that the leadership style of frontline managers has the most significant impact on frontline employees compared with the influence of leaders at other organisational levels, such as top-level leaders.

Employee wellbeing.

Zheng et al. [74] and Becker et al. [73] referred to a previous scale and divided employee wellbeing into three dimensions.

Employee retention.

This study mainly drew on the employee turnover intention and employee retention scales developed by DiPietro et al. [80] and Arasanmi and Krishna [81], comprising five items.

Service climate.

This study used the service climate measurement scale developed by Ashkanasy et al. [82] and Kralj and Solnet [83], comprising six items.

Procedural justice.

The scale measuring procedural justice was modified based on Erdogan et al. [84] and Ehrhart [47]. A total of four item scales were adopted in this research.

Customer satisfaction.

This study adopted the customer satisfaction measurement scale developed by Chan et al. [85] and Huang et al. [86], comprising four items.

4. Data analysis

In this study, common method bias (CMB) was detected using Harman’s single-factor test. The result of the variance explained by the first principal component extracted without rotation was 35.57%, which was 50% less than the threshold, indicating no serious CMB problem in this study [87].

Table 1 shows that demographic details from 485 valid samples are included in the data analysis. A total of 303 women (62.5%) and 182 men (37.5%) participated in the survey. The respondents are mainly 26–35 years old (75.1%). The education levels are mainly undergraduate and master’s degrees (78.6%). Working experience is usually one to three years (66.4%). Descriptive data analysis is presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Demographic Information.

| Categories | Frequencies | Percentages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 182 | 37.5% |

| Female | 303 | 62.5% | |

| Age | 18–25 years old | 364 | 75.1% |

| 26–35 years old | 26 | 5.4% | |

| 36–45 years old | 34 | 7.0% | |

| Education level | 46–55 years old | 52 | 10.7% |

| Over 55 years old | 9 | 1.9% | |

| High school and below | 24 | 4.9% | |

| Junior college | 43 | 8.9% | |

| Undergraduate | 194 | 40.0% | |

| Master’s | 187 | 38.6% | |

| Doctoral | 37 | 7.6% | |

| Years of work | 1–3 years | 322 | 66.4% |

| 4–6 years | 40 | 8.2% | |

| 7–10 years | 26 | 5.4% | |

| Over 10 years | 97 | 20.0% | |

| Job ranking | Operation level | 219 | 45.2% |

| Supervisory level | 35 | 7.2% | |

| Managerial level | 106 | 21.9% | |

| Others | 125 | 25.8% | |

| Total | 485 | 100% |

2N = 485.

Table 2. Descriptive data analysis.

| Names | Mean | Median | SD | EK | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP1 | 1.895 | 2.000 | 0.807 | 0.960 | 0.832 |

| EP2 | 1.973 | 2.000 | 0.843 | 1.085 | 0.879 |

| EP3 | 1.990 | 2.000 | 0.834 | −0.035 | 0.555 |

| EP4 | 2.031 | 2.000 | 0.867 | 0.141 | 0.569 |

| SB1 | 2.781 | 3.000 | 1.073 | −0.742 | 0.043 |

| SB2 | 2.827 | 3.000 | 1.041 | −0.712 | −0.056 |

| SB3 | 2.301 | 2.000 | 0.854 | −0.473 | 0.216 |

| SB4 | 2.016 | 2.000 | 0.812 | −0.263 | 0.479 |

| AC1 | 2.586 | 2.000 | 1.006 | −0.665 | 0.279 |

| AC2 | 2.428 | 2.000 | 0.924 | −0.411 | 0.338 |

| AC3 | 2.457 | 2.000 | 0.932 | −0.001 | 0.424 |

| FG1 | 2.363 | 2.000 | 0.968 | −0.250 | 0.480 |

| FG2 | 2.447 | 2.000 | 0.955 | −0.396 | 0.286 |

| FG3 | 2.538 | 2.000 | 0.895 | 0.184 | 0.422 |

| CO1 | 2.913 | 3.000 | 1.028 | −0.745 | 0.094 |

| CO2 | 2.464 | 2.000 | 0.927 | −0.691 | 0.168 |

| CO3 | 2.895 | 3.000 | 1.088 | −0.533 | 0.046 |

| AU1 | 2.487 | 2.000 | 0.868 | −0.117 | 0.326 |

| AU2 | 2.365 | 2.000 | 0.850 | −0.462 | 0.336 |

| AU3 | 2.355 | 2.000 | 0.971 | −0.221 | 0.448 |

| HU1 | 2.291 | 2.000 | 0.842 | −0.109 | 0.239 |

| HU2 | 2.122 | 2.000 | 0.804 | 0.754 | 0.610 |

| HU3 | 2.136 | 2.000 | 0.767 | −0.267 | 0.287 |

| HU4 | 2.247 | 2.000 | 0.828 | 0.584 | 0.583 |

| ST1 | 1.946 | 2.000 | 0.766 | −0.328 | 0.423 |

| ST2 | 2.074 | 2.000 | 0.868 | −0.323 | 0.444 |

| ST3 | 2.146 | 2.000 | 0.904 | 0.465 | 0.714 |

| SC1 | 2.920 | 4.000 | 0.804 | 0.506 | 0.497 |

| SC2 | 2.887 | 4.000 | 0.813 | 0.049 | 0.458 |

| SC3 | 2.889 | 4.000 | 0.849 | 0.462 | 0.636 |

| SC4 | 2.967 | 4.000 | 0.880 | 0.187 | 0.628 |

| SC5 | 2.955 | 4.000 | 0.841 | 0.542 | 0.707 |

| SC6 | 1.019 | 2.000 | 0.867 | 0.600 | −0.744 |

| LWB1 | 3.235 | 3.000 | 0.994 | −0.456 | −0.169 |

| LWB2 | 3.515 | 3.000 | 0.872 | 0.021 | −0.178 |

| LWB3 | 3.278 | 3.000 | 0.950 | −0.546 | −0.002 |

| WWB1 | 3.825 | 4.000 | 0.840 | −0.457 | −0.267 |

| WWB2 | 3.410 | 3.000 | 0.894 | −0.198 | −0.120 |

| WWB3 | 3.736 | 4.000 | 0.830 | −0.173 | −0.320 |

| PWB1 | 3.938 | 4.000 | 0.689 | −0.016 | −0.261 |

| PWB2 | 3.794 | 4.000 | 0.794 | −0.100 | −0.260 |

| PWB3 | 3.738 | 4.000 | 0.768 | −0.154 | −0.200 |

| PJ1 | 3.678 | 4.000 | 0.812 | −0.267 | −0.252 |

| PJ2 | 3.511 | 4.000 | 0.819 | 0.050 | −0.172 |

| PJ3 | 3.625 | 4.000 | 0.829 | 0.657 | −0.684 |

| PJ4 | 3.720 | 4.000 | 0.797 | 0.187 | −0.386 |

| CS1 | 3.767 | 4.000 | 0.803 | −0.255 | −0.345 |

| CS2 | 3.810 | 4.000 | 0.769 | 1.031 | −0.618 |

| CS3 | 3.924 | 4.000 | 0.741 | −0.046 | −0.366 |

| CS4 | 3.825 | 4.000 | 0.698 | 0.018 | −0.257 |

| ER1 | 3.569 | 4.000 | 0.949 | 0.229 | −0.598 |

| ER2 | 3.699 | 4.000 | 0.805 | 0.124 | −0.497 |

| ER3 | 3.546 | 4.000 | 0.963 | 0.077 | −0.583 |

| ER4 | 3.753 | 4.000 | 0.860 | 0.861 | −0.771 |

| ER5 | 3.567 | 4.000 | 0.941 | 0.333 | −0.754 |

3Note: SD = Standard deviation; EK = Excess kurtosis.

4.1. Reliability, validity and correlation

Table 3 presents the reliabilities, factor loadings (FL), average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliabilities (CR) for the constructs in this study. All Cronbach’s alpha values, which are for the internal consistency examinations, are above 0.7.

Table 3. Reliability and validity of the constructs.

| Scale items | Abbreviations | Factor loadings | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Servant leadership (including eight dimensions) | |||||

| Empowerment | 0.830 | 0.836 | 0.662 | ||

| My manager does not encourage me to use my talents. | EP1 | 0.989 | |||

| My manager does not encourage his/her staff to come up with new ideas. | EP2 | 0.958 | |||

| My manager does not just tell me what to do but enables me to solve problems myself. | EP3 | 0.984 | |||

| My manager does not offer me abundant opportunities to learn new skills. | EP4 | 0.866 | |||

| Standing back | 0.783 | 0.797 | 0.821 | ||

| My manager does not keep himself/herself in the background and gives credits to others. | SB2 | 0.880 | |||

| My manager appears to enjoy his/her own success more than his/her colleagues’ success. | SB3 | 0.865 | |||

| My manager does not encourage me to handle important work decisions on my own. | SB4 | 0.840 | |||

| Accountability | 0.717 | 0.718 | 0.779 | ||

| My manager does not hold me responsible for the work I carry out. | AC1 | 0.848 | |||

| I am not held accountable for my performance by my manager. | AC2 | 0.892 | |||

| My manager does not hold me and my colleagues responsible for the way we handle a job. | AC3 | 0.858 | |||

| Forgiveness | 0.762 | 0.772 | 0.676 | ||

| My manager does not keep criticising people for the mistakes they have made in their work (r) | FG1 | 0.903 | |||

| My manager does not maintain a hard attitude towards people who have offended him/her at work (r). | FG2 | 0.846 | |||

| My manager finds it is not difficult to forget things that went wrong in the past (r). | FG3 | 0.840 | |||

| Courage | 0.749 | 0.763 | 0.662 | ||

| My manager does not take risks when he/she is not certain of the support from his/her own manager. | CO1 | 0.826 | |||

| My manager does not take risks and does what needs to be done in his/her view. | CO2 | 0.872 | |||

| My manager is unwilling to risk rejection by someone important to get the opportunity to fulfill my life goals tome. | CO3 | 0.843 | |||

| Authenticity | 0.773 | 0.783 | 0.687 | ||

| My manager is not open about his/her limitations and weaknesses. | AU1 | 0.862 | |||

| My manager is not prepared to express his/her feelings even if this might have undesirable consequences. | AU2 | 0.807 | |||

| My manager does not show his/her true feelings to his/her staff. | AU3 | 0.803 | |||

| Humility | 0.799 | 0.820 | 0.623 | ||

| My manager does not learn from criticism. | HU1 | 0.797 | |||

| My manager does not try to learn from the criticism he/she gets from his/her superior. | HU2 | 0.804 | |||

| My manager does not admit his/her mistakes to his/her superior. | HU3 | 0.880 | |||

| My manager does not learn from the different views and opinions of others. | HU4 | 0.825 | |||

| Stewardship | 0.746 | 0.746 | 0.663 | ||

| My manager does not emphasise the importance of focusing on the good of the whole. | ST1 | 0.852 | |||

| My manager does not have a long-term vision. | ST2 | 0.826 | |||

| My manager does not emphasise the societal responsibility of our work. | ST3 | 0.847 | |||

| Service climate | 0.895 | 0.895 | 0.704 | ||

| Company management supports employees when they come up with new ideas on improved customer service. | SC1 | 0.814 | |||

| Company management sets definite quality standards of good customer service. | SC2 | 0.859 | |||

| Company management meets regularly with employees to discuss performance goals. | SC3 | 0.857 | |||

| New employees are trained by company management on how to best serve customers. | SC4 | 0.913 | |||

| Company management continually communicates the importance of service. | SC5 | 0.881 | |||

| There is a true commitment to service, not just ‘lip service’. | SC6 | 0.876 | |||

| Subjective wellbeing (including three dimensions) | |||||

| Life wellbeing | 0.842 | 0.844 | 0.759 | ||

| I am close to my dreaming most aspects of my life. | LWB1 | 0.841 | |||

| Most of the time, I do feel real happiness. | LWB2 | 0.840 | |||

| So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life. | LWB3 | 0.848 | |||

| Work wellbeing | 0.724 | 0.725 | 0.644 | ||

| I am satisfied with my work responsibilities. | WWB1 | 0.871 | |||

| I find real enjoyment in my work. | WWB2 | 0.863 | |||

| I can always find ways to enrich my work. | WWB3 | 0.834 | |||

| Psychological wellbeing | 0.718 | 0.724 | 0.640 | ||

| I handle daily affairs well. | PWB1 | 0.845 | |||

| I generally feel good about myself, and I am confident. | PWB2 | 0.778 | |||

| People think I am willing to give and to share my time with others. | PWB3 | 0.895 | |||

| Procedure justice | 0.830 | 0.838 | 0.661 | ||

| I believe my manager really tries to conduct a fair and objective appraisal. | PJ1 | 0.852 | |||

| Is procedural justice free of bias in your department? | PJ2 | 0.864 | |||

| Are your department’s procedures consistent with ethical standards? | PJ3 | 0.883 | |||

| Are your department’s procedures consistent with ethical standards? | PJ4 | 0.869 | |||

| Customer satisfaction | 0.877 | 0.879 | 0.731 | ||

| I am satisfied with the service we provide. | CS1 | 0.894 | |||

| Our internal operations are efficient and keep our customers satisfied. | CS2 | 0.849 | |||

| The attitude of our staff makes customers satisfied. | CS3 | 0.801 | |||

| Did your customer service experience meet your expectations? | CS4 | 0.834 | |||

| Employee retention | 0.871 | 0.881 | 0.658 | ||

| I feel satisfied with my work in this organisation. | ER1 | 0.895 | |||

| Level of satisfaction with job | ER2 | 0.867 | |||

| Experience: Advancement Opportunities | ER3 | 0.837 | |||

| If I wanted to move into another job or function, then I would firstly look within the organisation for possibilities. | ER4 | 0.871 | |||

| If it were up to me, then I would definitely be working for this agency for the next five years | ER5 | 0.855 | |||

To assess construct validity, all items’ factor loadings should be above 0.7. Otherwise, unqualified items should be removed [88]. Thus, SB1, SB2, AC1 and SC6 4 were removed for further analysis. The AVE values should be above 0.5, and CR should be over 0.7. Therefore, the results align with the guidelines set by Hair et al. [88], and the current study’s internal consistency reliability and validity are satisfactory.

As shown in Table 4, the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its correlation with the other constructs. Moreover, the HTMT value of all constructs was below 0.85. These results confirm the discriminant validity between all constructs [89]. Therefore, the results align with the reliability and validity test guidelines set by Hair et al. [88].

Table 4. Discriminant test.

| AC | AU | CO | CS | EP | ER | FG | HU | LWB | PJ | PWB | SB | SC | ST | WWB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 0.977 | ||||||||||||||

| AU | 0.614 (0.514) |

0.870 | |||||||||||||

| CO | 0.679 (0.435) |

0.694 (0.769) |

0.860 | ||||||||||||

| CS | 0.544 (0.418) |

0.620 (0.548) |

0.557 (0.533) |

0.862 | |||||||||||

| EP | 0.607 (0.503) |

0.565 (0.451) |

0.512 (0.528) |

0.578 (0.478) |

0.851 | ||||||||||

| ER | 0.539 (0.439) |

0.577 (0.577) |

0.601 (0.620) |

0.621 (0.680) |

0.528 (0.541) |

0.819 | |||||||||

| FG | 0.873 (0.726) |

0.677 (0.635) |

0.672 (0.787) |

0.565 (0.518) |

0.629 (0.689) |

0.544 (0.550) |

0.834 | ||||||||

| HU | 0.560 (0.490) |

0.721 (0.725) |

0.571 (0.604) |

0.652 (0.662) |

0.575 (0.623) |

0.544 (0.547) |

0.648 (0.724) |

0.844 | |||||||

| LWB | 0.540 (0.334) |

0.530 (0.436) |

0.668 (0.665) |

0.584 (0.601) |

0.472 (0.435) |

0.554 (0.610) |

0.564 (0.568) |

0.497 (0.348) |

0.890 | ||||||

| PJ | 0.583 (0.391) |

0.663 (0.712) |

0.624 (0.716) |

0.796 (0.843) |

0.593 (0.596) |

0.689 (0.790) |

0.630 (0.673) |

0.685 (0.707) |

0.631 (0.679) |

0.850 | |||||

| PWB | 0.539 (0.423) |

0.615 (0.545) |

0.518 (0.481) |

0.669 (0.800) |

0.514 (0.486) |

0.480 (0.538) |

0.584 (0.545) |

0.698 (0.699) |

0.587 (0.548) |

0.673 (0.731) |

0.847 | ||||

| SB | 0.764 (0.616) |

0.604 (0.574) |

0.713 (0.549) |

0.498 (0.532) |

0.646 (0.736) |

0.580 (0.573) |

0.708 (0.666) |

0.502 (0.594) |

0.604 (0.483) |

0.581 (0.457) |

0.476 (0.567) |

0.843 | |||

| SC | −0.610 (0.511) |

−0.710 (0.557) |

−0.583 (0.538) |

−0.728 (0.682) |

−0.655 (0.648) |

−0.626 (0.636) |

−0.655 (0.586) |

−0.743 (0.711) |

−0.549 (0.471) |

−0.744 (0.670) |

−0.662 (0.622) |

−0.586 (0.713) |

0.861 | ||

| ST | 0.599 (0.422) |

0.640 (0.402) |

0.540 (0.571) |

0.627 (0.532) |

0.616 (0.646) |

0.612 (0.654) |

0.658 (0.612) |

0.730 (0.612) |

0.545 (0.469) |

0.714 (0.614) |

0.608 (0.455) |

0.545 (0.584) |

−0.821 (0.786) |

0.866 | |

| WWB | 0.627 (0.383) |

0.625 (0.446) |

0.689 (0.752) |

0.627 (0.696) |

0.553 (0.672) |

0.636 (0.729) |

0.627 (0.681) |

0.611 (0.601) |

0.758 (0.764) |

0.701 (0.767) |

0.705 (0.810) |

0.649 (0.595) |

−0.657 (0.694) |

0.616 (0.634) |

0.854 |

5Note: The number set in boldface is the square root of AVE; the correlation coefficient is in the parentheses; the HTMT value is in parentheses.

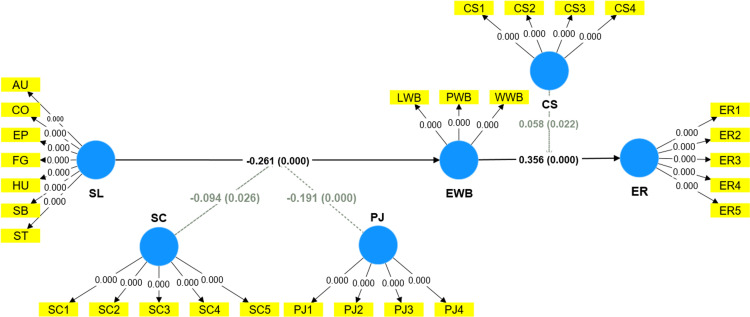

4.2. Results of the PLS analysis

A two-stage approach for high-order construct analysis was adopted in this study. Dimensions were transferred into indicators for high-order construction (Fig 2). Table 5 shows the path coefficients and hypothesis results. The PLS analysis results of the model show that low servant leadership (β = −0.261, t = 5.397, p < 0.05) significantly leads to low employee subjective wellbeing. Hence, H1 is supported. Employee wellbeing (β = 0.356, t = 6.821, p < 0.05) significantly affects employee retention. Thus, H2 is supported. That is, lower subjective wellbeing caused by low servant leadership would reduce employee retention (β = −0.093, t = 3.885, p < 0.05). Thus, subjective wellbeing bridges low servant leadership and employee retention.

Fig 2. Results of the PLS-SEM analysis.

Table 5. Hypothesis tests.

| Paths | Original sample | Sample mean | Standard deviation | t-statistic | P-values | Coincidence intervals | Test result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.50% | 97.50% | ||||||||

| H1 | SL → EWB | −0.261 | −0.263 | 0.048 | 5.397 | 0.000 | −0.353 | −0.167 | Supported |

| H2 | EWB → ER | 0.356 | 0.356 | 0.052 | 6.821 | 0.000 | 0.255 | 0.454 | Supported |

| H3 | SC x SL → EWB | −0.094 | −0.169 | −0.005 | 2.220 | 0.026 | −0.173 | −0.007 | Supported |

| H4 | PJ x SL → EWB | −0.191 | −0.257 | −0.118 | 5.110 | 0.000 | −0.265 | −0.117 | Supported |

| H5 | CS x EWB → ER | 0.058 | 0.008 | 0.110 | 2.296 | 0.022 | 0.009 | 0.108 | Supported |

| SL - > EWB → ER | −0.093 | −0.094 | 0.024 | 3.885 | 0.000 | −0.143 | −0.052 | ||

| SC x SL → EWB → ER | −0.033 | −0.033 | 0.016 | 2.026 | 0.043 | −0.068 | −0.002 | ||

| PJ x SL → EWB → ER | −0.068 | −0.067 | 0.016 | 4.284 | 0.000 | −0.101 | −0.039 | ||

This study used R2 to reflect the explanatory power of the research model, indicating how the independent variable can explain the dependent variable [90]. R2 of dependent variables, such as employee wellbeing and retention, are 0.600 and 0.477, respectively, higher than the critical value requirements in R2 (weak: 0.25; medium: 0.50; strong: 0.75) [91]. Therefore, independent variables explain the dependent variables’ variances well, and the model setup is satisfactory overall.

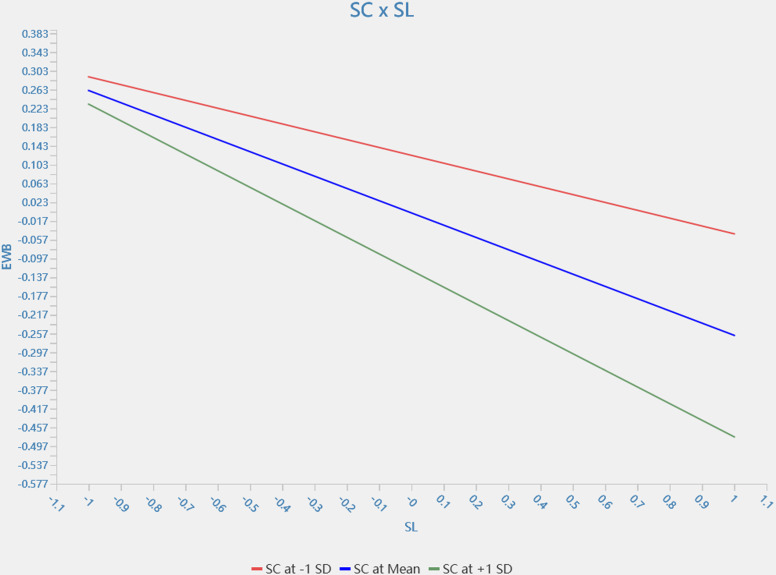

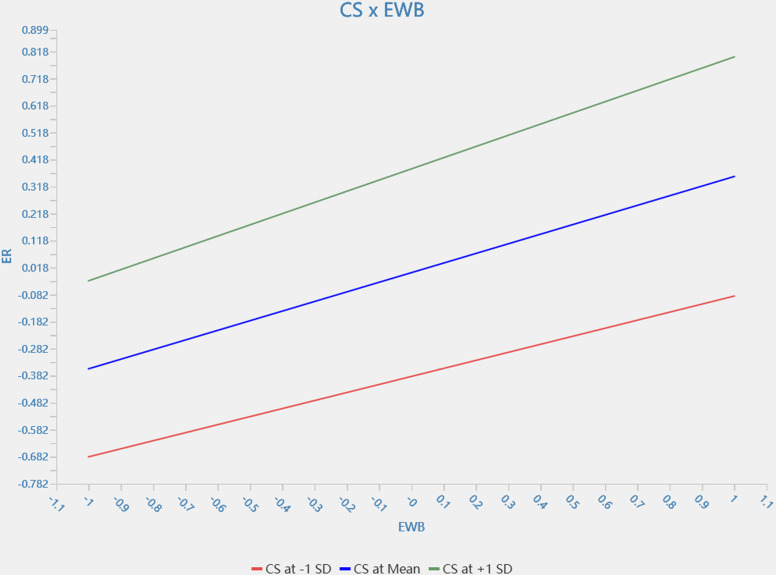

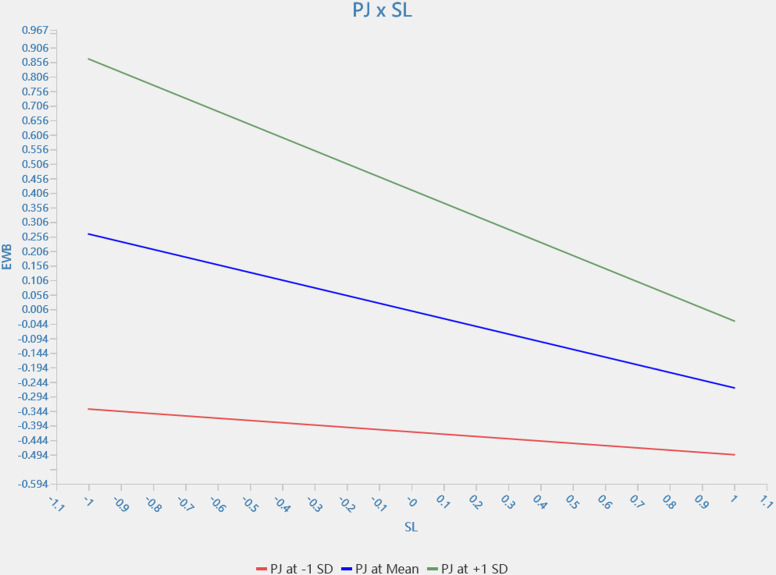

The results of the moderating effect show (Table 5 and Fig 2) that service climate moderates the relationship between servant leadership and employee wellbeing (β = −0.094, 95% CI = [−0.169, −0.005]). Additionally, procedural justice plays the same role as service climate in the relationship between servant leadership and employee well-being (β = −0.191, 95% CI = [−0.257, −0.118]). Customers’ satisfaction moderated the relationship between employee wellbeing and retention (β = 0.058, 95% CI = [0.008, 0.110]). These results indicate that H3, H4 and H5 are fully supported statistically. Figs 3–5 show simple slope analyses of three moderation effects.

Fig 3. SC .

× SL.

Fig 5. CS .

× EWB.

Fig 4. PJ .

× SL.

5. Discussion

In the actual process of business operation, the top management decision often interferes with the frontline managers’ actual management behaviour [92–95]. Given the attention to the ubiquity of compliance with top management decisions, considerable scholarly work has linked to low servant leadership styles that affect employees’ job satisfaction, employee well-being and loyalty to service organisation [9,10]. Therefore, this study was conducted to reveal other disregarded but significant factors that may be constructive for employee retention. We demonstrate that servant leadership has an impact on employee well-being and retention (H1 and H2). We also predict the service climate and procedural justice influence of the low servant leadership on employees (H3 and H4). Low servant leadership is the consequence of inhibiting results from the top management decisions. Furthermore, customer satisfaction exhibits a relationship between employees’ wellbeing and retention (H5).

The main result is consistent with a previous study’s results [96]. It indicates a continuous logical relationship between servant leadership and employee well-being and retention. The dark side of leadership is mostly affected by top management’s low empathy, thereby preventing frontline managers from engaging in desirable ethical decisions [9]. Moreover, the top management’s decision (service climate and procedural justice) plays a positive role in mitigating the harmful effect of low servant leadership. Therefore, open and transparent communication between top management and frontline managers can help ensure that the latter understand the organisations’ goals and expectations. This case can reduce the likelihood of frontline managers feeling constrained by top management’s directives.

Service climate and procedural justice are internal elements of organisational operations and organisational intrinsic capabilities that they can control. Judging from the results of this research, a positive service climate and fair procedure execution can significantly moderate the impact of servant leadership on employee wellbeing. Therefore, this result appeals to astute managers to focus substantially on the capability of the organisational climate and company procedures, which can provide fairness. The two measures can awaken employee enthusiasm, thereby enhancing organisational performance. Accordingly, creating a supportive and inclusive organisational climate can help frontline managers feel significantly empowered to practice servant leadership. This goal can be achieved through such initiatives as team-building activities, recognition programmes and employee feedback mechanisms. Furthermore, ensuring that organisational procedures are fair and transparent can help enhance employees’ perception of procedural justice. Consequently, this situation can improve employee wellbeing and retention.

Additionally, customer satisfaction would also affect employee retention. It is out of the control of the service organisation, but it cannot be disregarded. Customer satisfaction has a significant impact on employee satisfaction and subjective wellbeing. Furthermore, when employees lack job wellbeing and support from their frontline managers, it can affect their retention, ultimately leading to quitting [71].

Employee wellbeing positively impacts employee retention, thereby partially supporting the results of Gordon et al. [97]. However, our results reveal that low servant leadership diminishes this positive outcome. Service employees are markedly valuable and attached to their health and well-being if the leader supports them. Moreover, positive service climates and procedural justice can compensate for low servant leadership, thereby supporting employee retention. Frontline managers should substantially focus on these issues and avoid making the wrong management decisions, particularly blind compliance with top management strategic decisions.

Besides the negative outcomes of servant leadership, we contribute role theory, highlighting that frontline managers who follow top management advice and instructions are likely to reduce servant leadership behaviour [9,10]. Little is known about frontline manager traits and predicting their management outcomes [32]. Many scholars have overlooked ‘the dilemma of servant leadership’. To fill in this gap, our study examines servant leadership, especially the pressure that top management exerts on frontline service leadership. Pressure from top managers on frontline servant leaders to change their leadership behaviours and management styles significantly affects junior employees at work. Additionally, antecedents inhibiting frontline managers from adopting servant leadership, such as distorted management ethics, insufficient service climates and lack of procedural justice, lead to low servant leadership, thereby negatively affecting employees’ well-being and retention. To avoid this situation, organisations should invest in leadership training programmes focusing on developing servant leadership skills. These programmes can help frontline managers understand the importance of servant leadership and provide them with the tools to practice it effectively. Additionally, organisations should regularly monitor and evaluate their leadership practices to identify areas for improvement. This strategy can involve conducting employee surveys, performance reviews and leadership assessments.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The theoretical implications emphasise the significant influence of service climate and procedural justice on servant leadership style. Although existing studies often emphasise the advantages of leadership [9], they tend to overlook the detrimental effects of insufficient servant leadership on service employees’ wellbeing and employee retention. Scholars must acknowledge the negative impact associated with low servant leadership and the consequent organisational challenges it poses. Studies have linked low servant leadership to employee wellbeing and employee retention [11], but studies addressing this phenomenon have been limited [7,31,32,41].

The result demonstrates that service climate and procedural justice facilitate servant leadership. This study offers insights into top management and the relationship between frontline managers and servant leadership. Although no direct evidence demonstrates that top management affects service climate and procedural justice, their attention to frontline managers on compliance with organisations’ decisions and operational process may distort their management style and leadership. Our findings contribute LMX and role theories and suggest a distinct feature for explaining the low servant leadership impact by adopting role theory for discussion. Role theory discusses the top management influence and goes beyond the common conceptualisations inhibiting frontline managers [9,41]. Theory integration provides a benchmark for further investigating how management operation affects employees’ well-being and retention rather than solely focusing on organisational performance [98].

5.2. Practical implications

By revealing the relationship amongst servant leadership, employee well-being and retention, as well as the moderating role of service climate, procedural justice and customer satisfaction, this study provides hotel managers with a guideline reference for management practices.

Firstly, the result indicates that service climate and procedural justice can impact servant leadership on employee wellbeing and retention. In some ways, a poor service climate and unfairness undermine employees’ sense of wellbeing and contribute to employee turnover. Top management compliance with organisation decisions and direction influences frontline managers’ work behavior, thereby leading to an unconstructive leadership style. Therefore, this research highlights the importance of servant leadership and underscores the need for top management to communicate more effectively with frontline managers, aligning their practices with employees’ expectations. Hotel managers can create a positive service-oriented service climate through team building activities, employee recognition programmes or ongoing communication. Additionally, frontline leaders should be consulted regularly and involved in important decisions. A transparent and fair decision-making process must be established to ensure that frontline leaders have a sense of fairness and involvement in their work. Top managers should lead by example, particularly by demonstrating servant–leadership behaviours and setting an example for frontline leaders. We suggest that top management provides flexibility to frontline managers. Moreover, top management ensures they will not sacrifice frontline managers to pursue organisational goals. Our finding is that practitioners need to be aware that when frontline managers are low in perceptive–taking perceived top management decisions–they are likely to disregard service climate and procedural justice, excluding servant leadership from their behavioural repertoire. They may be susceptible to the adverse effects of top management perception. We suggest that organisations set criteria for selecting the right person for leadership or management positions.

Secondly, the results confirm that enhancing employee psychological wellbeing bridges servant leadership and employee retention, making it a necessary and effective way to improve retention in organisations. Hotel managers can offer flexible working arrangements to their employees to maintain their work–life balance. Moreover, employees must be provided with opportunities for career development paths, psychological counselling and stress management training, thereby enhancing their subjective wellbeing. If enterprises can take effective measures for the psychological wellbeing of employees and create organisational attachment, then identification will be created. This situation can improve employees and maintain the best talents for organisations.

Lastly, customer satisfaction significantly impacts employee satisfaction and wellbeing in organisations [71]. Practitioners need to monitor and improve customer satisfaction, which remains an important task for the hospitality industry to continue promoting daily. Hotel managers can establish effective customer feedback channels to collect and process customer opinions in a timely manner and continuously optimise services. By focusing on customer satisfaction with our products and services, we can immediately identify any issues. Additionally, giving employees additional authority to solve customer problems on the spot can also enhance the customer experience. This situation enables us to take immediate action to improve employee wellbeing and reduce their likelihood of leaving.

5.3. Limitations and further studies

This research has several limitations. Firstly, data were collected only from the Chinese hospitality industry and may not be generalisable in other cultural contexts. The Chinese culture emphasises collectivism and relationship orientation, which may have a unique impact on the practice and effectiveness of servant leadership [99,100]. For example, Chinese employees may be markedly inclined to accept authoritative leadership, which may conflict with the democratic and empowering style of servant leadership. Therefore, future research could consider conducting similar studies in different cultural contexts to verify the generalisability of the findings. Secondly, respondents from the hospitality sector have limitations in this study. The research sample mainly focused on frontline employees in the hospitality industry. In future research, scholars should consider including employees at different levels from different industries to provide considerable credibility to the study. Thirdly, we suggest that future research can further examine the top management managerial decision affecting frontline managers’ psychological wellbeing associated with their trust in organisations. The leadership style can extend to other negative leadership and provide insight to the further study.

Supporting information

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28606742.v1.

(XLSX)

Data Availability

The original data files of this study are available from the Figshare database (via: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28606742.v1).

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

References

- 1.Alonso AD, O’Neill MA. Staffing issues among small hospitality businesses: A college town case. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2009;28(4):573–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan Z, Mansor ZD, Choo WC, Abdullah AR. How to Reduce Employees’ Turnover Intention from the Psychological Perspective: A Mediated Moderation Model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:185–97. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S293839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghani B, Zada M, Memon KR, Ullah R, Khattak A, Han H, et al. Challenges and Strategies for Employee Retention in the Hospitality Industry: A Review. Sustainability. 2022;14(5):2885. doi: 10.3390/su14052885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anibal Luciano Alipio R, Xavier Arevalo Avecillas D, Wilfredo Quispe Santivañez G, Jimenez Mendoza W, Felipe Zavala Benites E. Servant leadership and organizational performance: Mediating role of organizational culture. Problems and Perspectives in Management. 2023;21(4):334–46. doi: 10.21511/ppm.21(4).2023.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agustin-Silvestre JA, Villar-Guevara M, García-Salirrosas EE, Fernández-Mallma I. The Human Side of Leadership: Exploring the Impact of Servant Leadership on Work Happiness and Organizational Justice. Behav Sci (Basel). 2024;14(12):1163. doi: 10.3390/bs14121163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Yuan B. Both angel and devil: The suppressing effect of transformational leadership on proactive employee’s career satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2017;65:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozturk A, Karatepe OM, Okumus F. The effect of servant leadership on hotel employees’ behavioral consequences: Work engagement versus job satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021;97:102994. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102994 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kauppila O-P, Ehrnrooth M, Mäkelä K, Smale A, Sumelius J, Vuorenmaa H. Serving to Help and Helping to Serve: Using Servant Leadership to Influence Beyond Supervisory Relationships. Journal of Management. 2021;48(3):764–90. doi: 10.1177/0149206321994173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babalola MT, Jordan SL, Ren S, Ogbonnaya C, Hochwarter WA, Soetan GT. How and When Perceptions of Top Management Bottom-Line Mentality Inhibit Supervisors’ Servant Leadership Behavior. Journal of Management. 2022;49(5):1662–94. doi: 10.1177/01492063221094263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim WC, Mauborgne RA. Procedural Justice, Attitudes, And Subsidiary Top Management Compliance With Multinationals’ Corporate Strategic Decisions. Academy of Management Journal. 1993;36(3):502–26. doi: 10.2307/256590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoch JE, Bommer WH, Dulebohn JH, Wu D. Do Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership Explain Variance Above and Beyond Transformational Leadership? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Management. 2016;44(2):501–29. doi: 10.1177/0149206316665461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi A, Sekar S, Das S. Decoding employee experiences during pandemic through online employee reviews: insights to organizations. PR. 2023;53(1):288–313. doi: 10.1108/pr-07-2022-0478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huertas-Valdivia I, Braojos J, Lloréns-Montes FJ. Counteracting workplace ostracism in hospitality with psychological empowerment. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2019;76:240–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling Y, Chung S, Wang L. Research on the reform of management system of higher vocational education in China based on personality standard. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:1225–37. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01480-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fors Brandebo M, Larsson G. Trust and destructive leadership during international military operations: A longitudinal study. FINT/EIASM Conference 2014 on Trust within and between Organisations: Dialogues between Research and Practice, Coventry University, Coventry, UK; 2014. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:781107 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tortorella GL, de Castro Fettermann D, Frank A, Marodin G. Lean manufacturing implementation: leadership styles and contextual variables. IJOPM. 2018;38(5):1205–27. doi: 10.1108/ijopm-08-2016-0453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birasnav M. Knowledge management and organizational performance in the service industry: The role of transformational leadership beyond the effects of transactional leadership. Journal of Business Research. 2014;67(8):1622–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCann J, Holt R. Ethical Leadership and Organizations: An Analysis of Leadership in the Manufacturing Industry Based on the Perceived Leadership Integrity Scale. J Bus Ethics. 2008;87(2):211–20. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9880-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng XL, Choi SL, Soehod K. The Effects of Servant Leadership on Employee’s Job Withdrawal Intention. ASS. 2016;12(2):99. doi: 10.5539/ass.v12n2p99 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu S, Dooley L. How servant leadership affects organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating roles of perceived procedural justice and trust. LODJ. 2022;43(3):350–69. doi: 10.1108/lodj-04-2021-0146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pham NT, Tuan TH, Le TD, Nguyen PND, Usman M, Ferreira GTC. Socially responsible human resources management and employee retention: The roles of shared value, relationship satisfaction, and servant leadership. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2023;414:137704. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin Y, Sung SY, Choi JN, Kim MS. Top Management Ethical Leadership and Firm Performance: Mediating Role of Ethical and Procedural Justice Climate. J Bus Ethics. 2014;129(1):43–57. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2144-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakotić D, Bulog I. Organizational Justice and Leadership Behavior Orientation as Predictors of Employees Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Croatia. Sustainability. 2021;13(19):10569. doi: 10.3390/su131910569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahednezhad H, Hoseini MA, Ebadi A, Farokhnezhad Afshar P, Ghanei Gheshlagh R. Investigating the relationship between organizational justice, job satisfaction, and intention to leave the nursing profession: A cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(4):1741–50. doi: 10.1111/jan.14717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong IA, Ma E, Chan SHG, Huang GI, Zhao T. When do satisfied employees become more committed? A multilevel investigation of the role of internal service climate. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2019;82:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan SHG, Lin Z (CJ), Wong IA, Chen Y (Victoria), So ACY. When employees fight back: Investigating how customer incivility and procedural injustice can impel employee retaliation. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2022;107:103308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao T, Huang X, Wang L, Li B, Dong X, Lu H, et al. Effects of organisational justice, work engagement and nurses’ perception of care quality on turnover intention among newly licensed registered nurses: A structural equation modelling approach. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(13–14):2626–37. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pattali S, Sankar JP, Al Qahtani H, Menon N, Faizal S. Effect of leadership styles on turnover intention among staff nurses in private hospitals: the moderating effect of perceived organizational support. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-10674-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samad A, Muchiri M, Shahid S. Investigating leadership and employee well-being in higher education. PR. 2021;51(1):57–76. doi: 10.1108/pr-05-2020-0340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rechel B, Buchan J, McKee M. The impact of health facilities on healthcare workers’ well-being and performance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(7):1025–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salas‐Vallina A, Alegre J, López‐Cabrales Á. The challenge of increasing employees’ well‐being and performance: How human resource management practices and engaging leadership work together toward reaching this goal. Human Resource Management. 2020;60(3):333–47. doi: 10.1002/hrm.22021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dietz C, Zacher H, Scheel T, Otto K, Rigotti T. Leaders as role models: Effects of leader presenteeism on employee presenteeism and sick leave. Work & Stress. 2020;34(3):300–22. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2020.1728420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change; 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauer TN, Green SG. Development Of A Leader-Member Exchange: A Longitudinal Test. Academy of Management Journal. 1996;39(6):1538–67. doi: 10.2307/257068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dansereau F Jr, Graen G, Haga WJ. A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1975;13(1):46–78. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(75)90005-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer TN, Erdogan B. The Oxford handbook of leader-member exchange. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cha J, Borchgrevink CP. Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) and Frontline Employees’ Service-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Foodservice Context: Exploring the Moderating Role of Work Status. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration. 2017;19(3):233–58. doi: 10.1080/15256480.2017.1324337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim M, Koo D. Linking lmx, engagement, innovative behavior, and job performance in hotel employees. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2017;29:3044–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang PQ, Kim PB, Milne S. Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) and Its Work Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Gender. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management. 2016;26(2):125–43. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2016.1185989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang J, Kandampully J. Reducing Employee Turnover Intention Through Servant Leadership in the Restaurant Context: A Mediation Study of Affective Organizational Commitment. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration. 2017;19(2):125–41. doi: 10.1080/15256480.2017.1305310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biddle BJ. Recent Developments in Role Theory. Annu Rev Sociol. 1986;12(1):67–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joplin T, Greenbaum RL, Wallace JC, Edwards BD. Employee Entitlement, Engagement, and Performance: The Moderating Effect of Ethical Leadership. J Bus Ethics. 2019;168(4):813–26. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04246-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiersema MF, Bantel KA. Top Management Team Demography and Corporate Strategic Change. AMJ. 1992;35:91–121. doi: 10.5465/256474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shin Y, Hur W-M, Moon TW, Lee S. A Motivational Perspective on Job Insecurity: Relationships Between Job Insecurity, Intrinsic Motivation, and Performance and Behavioral Outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1812. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song S, Shi Y, Ge X, Wang W, Yu H, Tian AW. Leader empowering and upper echelons decision‐making: How and when does top managers’ empowering leadership promote decision‐making speed and comprehensiveness in public organizations? Public Administration. 2024;103(1):136–65. doi: 10.1111/padm.13011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canavesi A, Minelli E. Servant Leadership: a Systematic Literature Review and Network Analysis. Employ Respons Rights J. 2021;34(3):267–89. doi: 10.1007/s10672-021-09381-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehrhart MG. Leadership And Procedural Justice Climate As Antecedents Of Unit‐Level Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Personnel Psychology. 2004;57(1):61–94. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02484.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyler TR, Lind EA. A relational model of authority in groups. In MP Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Vol. 25. p. 115–191. 1992. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60283-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gandolfi F, Stone S. Leadership, leadership styles, and servant leadership. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayer DM, Bardes M, Piccolo RF. Do servant-leaders help satisfy follower needs? An organizational justice perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2008;17(2):180–97. doi: 10.1080/13594320701743558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zineldin M, Hytter A. Leaders’ negative emotions and leadership styles influencing subordinates’ well-being. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2012;23(4):748–58. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.606114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Panaccio A, Raja U, Donia M, Landry G, Pereira MM, et al. Servant leadership and employee wellbeing: A crosscultural investigation of the moderated path model in Canada, Pakistan, China, the US, and Brazil. Int’l Jnl of Cross Cultural Management. 2022;22(2):301–25. doi: 10.1177/14705958221112859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Das BL. Employee Retention: A Review of Literature. IOSR-JBM. 2013;14(2):08–16. doi: 10.9790/487x-1420816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tuzovic S, Kabadayi S. The influence of social distancing on employee well-being: a conceptual framework and research agenda. J Serv Manag. 2021;32:145–60. [Google Scholar]

- 55.DiPietro R, Milman A. Hourly employee retention factors in the quick service restaurant industry. Int J Hosp Tour Adm. 2004;5:31–51. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gelencsér M, Szabó-Szentgróti G, Kőmüves ZS, Hollósy-Vadász G. The Holistic Model of Labour Retention: The Impact of Workplace Wellbeing Factors on Employee Retention. Administrative Sciences. 2023;13(5):121. doi: 10.3390/admsci13050121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneider B, White SS, Paul MC. Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: test of a causal model. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83(2):150–63. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong Y, Liao H, Hu J, Jiang K. Missing link in the service profit chain: a meta-analytic review of the antecedents, consequences, and moderators of service climate. J Appl Psychol. 2013;98(2):237–67. doi: 10.1037/a0031666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Y, Huang S (Sam). Hospitality service climate, employee service orientation, career aspiration and performance: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2017;67:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.07.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bowen DE, Schneider B. A Service Climate Synthesis and Future Research Agenda. Journal of Service Research. 2013;17(1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/1094670513491633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Veld M, Alfes K. HRM, climate and employee well-being: comparing an optimistic and critical perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2017;28(16):2299–318. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1314313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lambert EG, Keena LD, Leone M, May D, Haynes SH. The effects of distributive and procedural justice on job satisfaction and organizational commitment ofcorrectional staff. The Social Science Journal. 2020;57(4):405–16. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2019.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qureshi H, Frank J, Lambert EG, Klahm C, Smith B. Organisational justice’s relationship with job satisfaction and organisational commitment among Indian police. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles. 2016;90(1):3–23. doi: 10.1177/0032258x16662684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Binns R, Van Kleek M, Veale M, Lyngs U, Zhao J, Shadbolt N. “It’s Reducing a Human Being to a Percentage”: Perceptions of Justice in Algorithmic Decisions. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2018. p. 1–14. doi: 10.1145/3173574.3173951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mayer D, Nishii L, Schneider B, Goldstein H. The Precursors And Products Of Justice Climates: Group Leader Antecedents And Employee Attitudinal Consequences. Personnel Psychology. 2007;60(4):929–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00096.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walumbwa FO, Hartnell CA, Oke A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: a cross-level investigation. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(3):517–29. doi: 10.1037/a0018867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujishiro K, Heaney CA. Justice at work, job stress, and employee health. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(3):487–504. doi: 10.1177/1090198107306435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elovainio M, Kivimäki M, Helkama K. Organization justice evaluations, job control, and occupational strain. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):418–24. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robbins JM, Ford MT, Tetrick LE. Perceived unfairness and employee health: a meta-analytic integration. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(2):235–72. doi: 10.1037/a0025408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zygiaris S, Hameed Z, Ayidh Alsubaie M, Ur Rehman S. Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in the Post Pandemic World: A Study of Saudi Auto Care Industry. Front Psychol. 2022;13:842141. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frey R-V, Bayón T, Totzek D. How Customer Satisfaction Affects Employee Satisfaction and Retention in a Professional Services Context. Journal of Service Research. 2013;16(4):503–17. doi: 10.1177/1094670513490236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gilad S. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Pursuit of Richer Answers to Real-World Questions. Public Performance & Management Review. 2019;44(5):1075–99. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2019.1694546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Becker C, Kirchmaier I, Trautmann ST. Marriage, parenthood and social network: Subjective well-being and mental health in old age. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0218704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zheng X, Zhu W, Zhao H, Zhang C. Employee well-being in organizations: theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J Organ Behav. 2015;36:621–44. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ghaleb EAA, Dominic PDD, Fati SM, Muneer A, Ali RF. The Assessment of Big Data Adoption Readiness with a Technology–Organization–Environment Framework: A Perspective towards Healthcare Employees. Sustainability. 2021;13(15):8379. doi: 10.3390/su13158379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brislin RW. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1970;1(3):185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kock N, Hadaya P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS‐SEM: The inverse square root and gamma‐exponential methods. Information Systems Journal. 2016;28(1):227–61. doi: 10.1111/isj.12131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Dierendonck D. Servant Leadership: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of Management. 2010;37(4):1228–61. doi: 10.1177/0149206310380462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ling Q, Lin M, Wu X. The trickle-down effect of servant leadership on frontline employee service behaviors and performance: A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tourism Management. 2016;52:341–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DiPietro RB, Moreo A, Cain L. Well-being, affective commitment and job satisfaction: influences on turnover intentions in casual dining employees. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management. 2019;29(2):139–63. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2019.1605956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arasanmi CN, Krishna A. Employer branding: perceived organisational support and employee retention – the mediating role of organisational commitment. Ind Commer Train. 2019;51:174–83. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ashkanasy NM, Wilderom CP, Peterson MF. Handbook of organizational culture and climate. Sage.CA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kralj A, Solnet D. Service climate and customer satisfaction in a casino hotel: An exploratory case study. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2010;29(4):711–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Erdogan B, Kraimer ML, Liden RC. Procedural Justice as a Two-Dimensional Construct. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2001;37(2):205–22. doi: 10.1177/0021886301372004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chan KW, Yim CK (Bennett), Lam SSK. Is Customer Participation in Value Creation a Double-Edged Sword? Evidence from Professional Financial Services across Cultures. Journal of Marketing. 2010;74(3):48–64. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.74.3.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang P-L, Lee BCY, Chen C-C. The influence of service quality on customer satisfaction and loyalty in B2B technology service industry. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. 2017;30(13–14):1449–65. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2017.1372184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. EBR. 2019;31(1):2–24. doi: 10.1108/ebr-11-2018-0203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wendy Gao B, Lai IKW. The effects of transaction-specific satisfactions and integrated satisfaction on customer loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2015;44:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Usakli A, Kucukergin KG. Using partial least squares structural equation modeling in hospitality and tourism. IJCHM. 2018;30(11):3462–512. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-11-2017-0753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice. 2011;19(2):139–52. doi: 10.2753/mtp1069-6679190202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Terglav K, Konečnik Ruzzier M, Kaše R. Internal branding process: Exploring the role of mediators in top management’s leadership–commitment relationship. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2016;54:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim YH, Sting FJ, Loch CH. Top‐down, bottom‐up, or both? Toward an integrative perspective on operations strategy formation. J of Ops Management. 2014;32(7–8):462–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2014.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soltani E, Wilkinson A. Stuck in the middle with you. International Journal of Operations & Production Management. 2010;30(4):365–97. doi: 10.1108/01443571011029976 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ke W, Wei KK. Organizational culture and leadership in ERP implementation. Decision Support Systems. 2008;45(2):208–18. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2007.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Das SS, Pattanayak S. Understanding the effect of leadership styles on employee well-being through leader-member exchange. Curr Psychol. 2022;42(25):21310–25. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03243-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gordon S, Tang C-H (Hugo), Day J, Adler H. Supervisor support and turnover in hotels. IJCHM. 2019;31(1):496–512. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-10-2016-0565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zada M, Zada S, Ali M, Jun ZY, Contreras-Barraza N, Castillo D. How Classy Servant Leader at Workplace? Linking Servant Leadership and Task Performance During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Moderation and Mediation Approach. Front Psychol. 2022;13:810227. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.810227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fong LHN, He H, Chao MM, Leandro G, King D. Cultural essentialism and tailored hotel service for Chinese: the moderating role of satisfaction. IJCHM. 2019;31(9):3610–26. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-11-2018-0910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Huang Y-H, Bedford O, Zhang Y. The relational orientation framework for examining culture in Chinese societies. Culture & Psychology. 2017;24(4):477–90. doi: 10.1177/1354067x17729362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28606742.v1.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The original data files of this study are available from the Figshare database (via: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28606742.v1).