Abstract

Transient hyperammonemia of the newborn is a rare form of hyperammonemia with an unclear, likely nongenetic etiology, primarily affecting larger preterm infants. However, lower birth weight and gestational age are associated with higher ammonia levels, increasing the risk of neurotoxicity and hepatotoxicity. Transient hyperammonemia of the newborn typically manifests as respiratory distress within the first 24 h post-birth, progressing to seizures and coma within 48 h. Continuous renal replacement therapy has demonstrated considerable efficacy in managing severe transient hyperammonemia of the newborn due to its high ammonia clearance rate; however, its application remains limited in very low birth weight preterm infants. Herein, we report the case of a male infant born at 28+2 weeks gestation, weighing 1120 g, who developed transient hyperammonemia of the newborn 22 h post-birth. Despite initial pharmacotherapy and peritoneal dialysis, his ammonia levels continued to rise, necessitating continuous renal replacement therapy. After 42 h of continuous renal replacement therapy, his ammonia levels decreased significantly and he recovered fully, eventually being discharged in good health. This case highlights continuous renal replacement therapy as a viable, life-saving intervention for severe transient hyperammonemia of the newborn, even in very low birth weight preterm infants.

Keywords: Transient hyperammonemia, continuous renal replacement therapy, newborn, preterm infant, very low birth weight

Introduction

Neonatal hyperammonemia is a metabolic syndrome characterized by excessive blood ammonia levels and resultant central nervous system dysfunction. It commonly occurs in conditions such as urea cycle disorders but may also develop secondary to severe hepatic disease, organic acidemias, or multiple carboxylase deficiencies. 1 Transient hyperammonemia of the newborn (THAN) is a hyperammonemia condition with an unknown, likely nongenetic etiology, frequently affecting older preterm infants. These infants typically develop respiratory distress within the first 24 h after birth, with subsequent neurological symptoms such as seizures and coma emerging within 48 h. Lower birth weight and gestational age are associated with elevated blood ammonia levels in THAN. 2

Prolonged hyperammonemia is highly neurotoxic and hepatotoxic, adversely affecting multiple organ systems, including the skeletal muscle, vasculature, kidneys, and lungs.3–6 In severe cases, the patient may develop neurological symptoms such as hypo-reactivity, seizures, and encephalopathy, potentially progressing to intracranial hypertension, cerebral edema, brain herniation, acute liver failure, pulmonary edema, and ultimately multiorgan dysfunction or death. The mortality rate of preterm infants with THAN is estimated to be 6.2%. Moreover, elevated ammonia levels are linked to poor long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes, with ammonia levels ≥360 μmol/L serving as a critical predictor of adverse neurological prognosis. 7 Adults who experienced neonatal THAN may exhibit cognitive and developmental disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. 8

Considering the life-threatening neurotoxicity of severe hyperammonemia, urgent and proactive treatment is essential to reduce mortality and mitigate long-term neurological sequelae. Research has indicated that the prognosis of nervous system dysfunction is closely related to the rate of ammonia clearance.4,9 Therefore, infants with severe hyperammonemia should receive prompt intervention. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) is considered the first-line therapy for neonatal hyperammonemia due to its fewer cardiovascular complications, reduced plasma and transfusion requirements, lower risk of rebound hyperammonemia, and more efficient ammonia clearance rate compared with hemodialysis. 10 However, reports of CRRT for low birth weight and small gestational age preterm infants remain scarce. 11

Herein, we present the case of a very low birth weight (VLBW) preterm infant who developed severe hyperammonemia 22 h after birth. The infant did not respond adequately to standard hyperammonemia treatment but ultimately survived following CRRT. This case confirms that CRRT is an effective treatment modality for severe transient hyperammonemia and can be safely used in VLBW preterm infants.

Case presentation

The patient was a male infant born at 28+2 weeks gestation via cesarean section on 19 August 2023 at Quanzhou Maternity and Children’s Hospital in Fujian Province, China. He weighed 1120 g at birth and exhibited premature rupture of membranes (PROM). He was the second child in a family with no history of genetic disorders or consanguinity. Apgar scores were 7, 8, and 8 at 1, 5, and 10 min, respectively. Upon delivery, he exhibited respiratory distress, requiring immediate intubation, mechanical ventilation, and transfer to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for comprehensive supportive care.

Before delivery, the mother had received a course of dexamethasone at a local hospital to promote fetal lung maturity. PROM occurred 24 h before delivery, with no evidence of intrauterine distress or abnormalities in the amniotic fluid, umbilical cord, or placenta. The mother had a history of miscarriage.

Initial clinical and laboratory findings

Vital signs: Blood pressure level was 48/27 mmHg.

Neurological status: Clear consciousness, equal and reactive pupils (2.5 mm in diameter), warm extremities, and slightly reduced muscle tone in all limbs.

Arterial blood gas analysis: pH = 7.332, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) = 35.10 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) = 61.10 mmHg, base excess (BE) = −6.70 mmol/L, bicarbonate ion ( ) = 18.20 mmol/L.

Electrolytes and metabolic parameters: potassium ion (K+) = 3.75 mmol/L, sodium ion (Na+) = 138.5 mmol/L, glucose = 3.600 mmol/L, lactate =24.4 mg/dL.

Complete blood count: White blood cell count = 13.4 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage = 55.1%, hemoglobin level =169 g/L, platelet count = 301 × 109/L.

Inflammatory markers: C-reactive protein level = 0.29 mg/L.

Liver and renal function tests: Normal.

Urine ketones: Negative.

Cardiac ultrasound: Patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, mild tricuspid regurgitation, and pulmonary hypertension.

Clinical course

After admission, supportive care included fasting, total parenteral nutrition, mechanical ventilation, surfactant replacement, caffeine for respiratory stimulation, and antibiotic therapy with penicillin and ceftazidime to prevent infection.

At 12 h of life, the infant exhibited decreased oxygen saturation (88%–89%) and diminished responsiveness. Repeat blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.310, pCO2 of 33.1 mmHg, pO2 of 45.7 mmHg, BE of −10.0 mmol/L, level of 16.3 mmol/L, anion gap of 23.7 mmol/L, and lactate level of 44.2 mg/dL, indicating hypoxemia, metabolic acidosis, and lactic acidosis. Treatment adjustments included ventilator settings, a second dose of surfactant, and vasopressor support with dopamine and dobutamine to improve circulation.

At 22 h of life, repeat lactate level was 70.4 mg/dL, and blood ammonia levels reached 940 μmol/L, indicating severe hyperammonemia. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS) of blood samples and gas chromatography–MS (GC–MS) of urine samples showed no specific abnormalities. Whole exome sequencing revealed no mutations associated with congenital metabolic diseases.

Treatment

In the initial phase when inherited metabolic disorders could not be ruled out, enteral nutrition administration along with amino acid and lipid emulsion administration was temporarily suspended. Carnitine (100 mg/(kg·d)) and arginine hydrochloride (200 mg/(kg·d)) were administered to enhance ammonia excretion. However, by 30 h of life, the infant’s ammonia levels had only slightly decreased to 876 μmol/L, necessitating peritoneal dialysis.

Peritoneal dialysis was initiated using a 6-Fr double-lumen central venous catheter placed in the rectovesical pouch via the left lower quadrant (lateral third of the umbilical-to-anterior superior iliac spine line). The protocol utilized pre-warmed dialysate (35°C–36°C) infused at 30 mL/kg/h with a volume of 10–15 mL/kg/cycle, 30-min dwells, and 30-min drainage intervals, adjusted based on fluid balance.

Despite peritoneal dialysis and ammonia-clearing medications, the infant exhibited refractory hyperammonemia (920–1110 μmol/L at 3–23 h post-peritoneal dialysis initiation) and persistent metabolic acidosis, necessitating transition to CRRT. Therefore, CRRT was initiated at 56 h of life using the Plasauto iQ21 system (Asahi Kasei Medical, Tokyo) with a polysulfone AEF-03 hemofilter. A 4.0-Fr double-lumen dialysis catheter was placed in the right internal jugular vein for vascular access. The circuit was pre-primed with packed red blood cells (RBCs), and heparin anticoagulant was titrated to maintain target coagulation parameters. CRRT parameters were set as follows: blood flow rate of 7 mL/kg/min, replacement fluid rate of 100 mL/h, dialysate flow rate of 550 mL/h (Table 1).

Table 1.

CRRT prescription.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Device brand | Plasauto iQ21 system (Asahi Kasei Medical) |

| Hemofilter | Polysulfone membrane AEF-03 filter |

| Precharge | Packed red blood cells |

| Modality | CVVHDF |

| Catheter size | 4-Fr double-lumen |

| Blood access | Right internal jugular vein |

| Blood flow rate | 7 mL/min |

| Replacement fluid rate | 100 mL/h |

| Dialysate flow rate | 550 mL/h |

| Anticoagulant | Heparin |

| Ultrafiltration plan | None |

CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; CVVHDF: continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration.

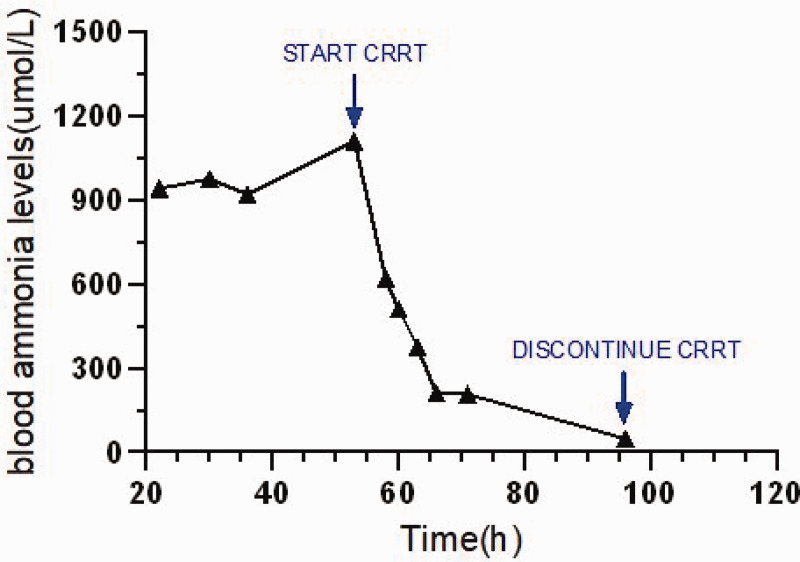

During CRRT initiation, the infant’s blood pressure level dropped to 37/23 mmHg. Vasopressors dosages were adjusted to stabilize the mean arterial pressure at 30–40 mmHg. Ammonia levels declined rapidly to 510 μmol/L after 4 h and 48 μmol/L after 42 h of treatment. CRRT was discontinued due to a platelet count of 11 × 109/L and high bleeding risk. The arginine dose was gradually tapered over the next 7 days, with blood ammonia levels stabilizing between 26 and 93 μmol/L (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fluctuation in blood ammonia levels over hours.

Outcome

The infant was discharged after a 102-day NICU stay, with stable oxygen saturation, strong sucking reflex, and a corrected gestational age of 42+6 weeks (weight: 3730 g). Follow-up neurological assessments, including cranial ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, hearing tests, and video electroencephalogram, showed no abnormalities. At the corrected age of 6 and 12 months, the infant exhibited normal ammonia levels, organ function, and neurodevelopmental milestones.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of THAN remains unclear and may involve increased production and decreased elimination of ammonia. Proposed mechanisms include transient platelet activation in the hepatic portal system 12 or vascular complications due to insufficient ammonia clearance. 13 Conditions such as infection, ischemia, hypoxia, shock, and hemolysis are commonly associated with THAN in preterm infants, with severe infection potentially exacerbating hyperammonemia through increased catabolic activity. 14

THAN is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring the elimination of metabolic disorders such as UCDs, organic acidemias, and fatty acid oxidation defects. In this case, the infant presented with severe hyperammonemia (1110 μmol/L) at 53 h postpartum. Metabolic screening (including liver function tests, tandem MS, and GC–MS) and whole exome sequencing revealed no abnormalities, effectively excluding congenital metabolic disorders. During follow-up, the infant maintained normal ammonia levels while receiving no specific treatment and tolerating a regular diet, confirming the diagnosis of severe THAN.

Severe hyperammonemia (>400 μmol/L) can lead to irreversible neurological damage or death. 15 Prognosis depends on the duration of hyperammonemia, peak ammonia levels, and clearance rate.16,17 CRRT is an effective approach for rapidly reducing ammonia levels and should be initiated promptly in patients with hyperammonemic encephalopathy and persistent ammonia levels of 300–500 μmol/L or >500 μmol/L. 5

CRRT has expanded to treat various diseases and support multiorgan dysfunction, with applications extending to neonates. 18 However, reports of CRRT for neonatal hyperammonemia, particularly in VLBW infants, remain limited. 19 This case demonstrates CRRT’s efficacy in a 1120-g preterm infant with refractory hyperammonemia, highlighting its potential for VLBW neonates.

Hemodynamic instability during CRRT initiation is common, with 85% of preterm infants requiring inotropic support. 20 This may be associated with the small circulating blood volume in neonates and priming volume of the extracorporeal circuit. 21 When the capacity of the tubing and filter (priming volume) is relatively greater than the circulating blood volume, the empty flow effect and blood dilution can lead to hypotension. To mitigate complications, CRRT machines must be optimized for neonates, and strategies such as RBC priming and vasopressor titration are critical.

Studies have reported a THAN survival rate of 13/18 (approximately 72.2%). 22 Neurological prognosis in hyperammonemia is correlated with coma duration and peak ammonia levels. 4 Although mild THAN rarely causes sequelae, severe THAN (>400 μmol/L) can impair neurodevelopment. Most patients recover with timely treatment, although ammonia levels above 1000 μmol/L are associated with poor outcomes. 23 This infant’s remarkable recovery, despite extreme hyperammonemia, underscores the importance of early intervention.

Gestational age <34 weeks and weight <2.0 kg are relative contraindications for CRRT. However, given the critical impact of hyperammonemia duration on outcomes, early CRRT initiation is advisable when irreversible fluid overload or metabolic disturbances are anticipated.

Conclusion

CRRT is an effective treatment modality for severe hyperammonemia in neonates, including VLBW preterm infants. Successful implementation requires timely diagnosis, hemodynamic stability, meticulous fluid management, and an experienced intensive care team. This case supports the viability of CRRT as a life-saving intervention for severe THAN in extremely premature infants.

Acknowledgment

We thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Authors’ contributions: JL conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. JX and DC critically revised the manuscript and guided the study. JX, HY, ZL, and WZ oversaw patient care and data collection. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Quanzhou Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 2022C002) and the Quanzhou City Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 2023NS064).

ORCID iD: Jinglin Xu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6658-0058

Consent for publication

Verbal consent for publication was obtained from the parents of the infant.

Data availability statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report follows the Case Report (CARE) guidelines and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Quanzhou Women’s and Children’s Hospital (No. 50, 2023).

References

- 1.Li M, Chen X, Chen H, et al. Genetic background and clinical characteristics of infantile hyperammonemia. Transl Pediatr 2023; 12: 882–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudak ML, Jones MD, Jr, Brusilow SW. Differentiation of transient hyperammonemia of the newborn and urea cycle enzyme defects by clinical presentation. J Pediatr 1985; 107: 712–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ribas GS, Lopes FF, Deon M, et al. Hyperammonemia in inherited metabolic diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2022; 42: 2593–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raina R, Bedoyan JK, Lichter-Konecki U, et al. Consensus guidelines for management of hyperammonaemia in paediatric patients receiving continuous kidney replacement therapy. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020; 16: 471–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfadhel M, Mutairi FA, Makhseed N, et al. Guidelines for acute management of hyperammonemia in the Middle East region. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2016; 12: 479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warrillow S, Fisher C, Bellomo R. Correction and control of hyperammonemia in acute liver failure: the impact of continuous renal replacement timing, intensity, and duration. Crit Care Med 2020; 48: 218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kido J, Matsumoto S, Häberle J, et al. Long-term outcome of urea cycle disorders: report from a nationwide study in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis 2021; 44: 826–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kido J, Matsumoto S, Ito T, et al. Physical, cognitive, and social status of patients with urea cycle disorders in Japan. Mol Genet Metab Rep 2021; 27: 100724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yetimakman AF, Kesici S, Tanyildiz M, et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy for treatment of severe attacks of inborn errors of metabolism. J Pediatr Intensive Care 2019; 8: 164–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai YC, Huang HP, Tsai IJ, et al. High-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration as an effective therapy for acute management of inborn errors of metabolism in young children. Blood Purif 2007; 25: 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang LF, Ding JC, Zhu LP, et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy rescued life-threatening capillary leak syndrome in an extremely-low-birth-weight premature: a case report. Ital J Pediatr 2021; 47: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Geet C, Vandenbossche L, Eggermont E, et al. Possible platelet contribution to pathogenesis of transient neonatal hyperammonaemia syndrome. Lancet 1991; 337: 73–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuchman M, Georgieff MK. Transient hyperammonemia of the newborn: a vascular complication of prematurity? J Perinatol 1992; 12: 234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ames EG, Powell C, Engen RM, et al. Multisite retrospective review of outcomes in renal replacement therapy for neonates with inborn errors of metabolism. J Pediatr 2022; 246: 116–122.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballard RA, Vinocur B, Reynolds JW, et al. Transient hyperammonemia of the preterm infant. N Engl J Med 1978; 299: 920–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porta F, Peruzzi L, Bonaudo R, et al. Differential response to renal replacement therapy in neonatal-onset inborn errors of metabolism. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018; 23: 957–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JY, Lee Y, Cho H. Optimal prescriptions of continuous renal replacement therapy in neonates with hyperammonemia. Blood Purif 2019; 47: 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellomo R, Baldwin I, Ronco C, et al. ICU-based renal replacement therapy. Crit Care Med 2021; 49: 406–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diane Mok TY, Tseng MH, Chiang MC, et al. Renal replacement therapy in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Neonatol 2018; 59: 474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noh ES, Kim HH, Kim HS, et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy in preterm infants. Yonsei Med J 2019; 60: 984–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raina R, Lam S, Raheja H, et al. Pediatric intradialytic hypotension: recommendations from the Pediatric Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (PCRRT) Workgroup. Pediatr Nephrol 2019; 34: 925–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stojanovic VD, Doronjski AR, Barisic N, et al. A case of transient hyperammonemia in the newborn transient neonatal hyperammonemia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010; 23: 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gropman AL, Prust M, Breeden A, et al. Urea cycle defects and hyperammonemia: effects on functional imaging. Metab Brain Dis 2013; 28: 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.