Abstract

Objectives

Congenital heart disease (CHD) patients with single ventricle physiology (SVP) have heterogeneous characteristics that challenge cohort classification. We aim to develop a phenotyping algorithm that accurately identifies SVP patients using electronic health record (EHR) data.

Materials and Methods

We used ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for initial classification, then enhanced the algorithm with domain expertise, imaging reports, and progress notes. The algorithm was developed using a cohort of 1020 patients who underwent magnetic resonance imaging scans and tested in a separate cohort of 2500 CHD patients with adjudication. Validation was performed in a holdout group of 22 500 CHD patients. We evaluated performance using accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1 score, and compared it to a published algorithm for SVP using the same dataset.

Results

In the 2500-testing cohort, our algorithm based on specialty-defined features and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes achieved 99.24% accuracy, 94.12% precision, 85.11% sensitivity, and 89.39% F1 score. In contrast, the published method achieved 95.20% accuracy, 43.23% precision, 88.30% sensitivity, and 58.04% F1 score. In the 22 500-validation cohort, our algorithm achieved 93.82% precision, while the published method achieved 43.00%.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our automated phenotype algorithm, combined with physician adjudication, outperforms a published method for SVP classification. It effectively identifies false positives by cross-referencing clinical notes and detects missed SVP cases that were due to absent or erroneous ICD codes. Our integrated phenotyping algorithm showed excellent performance and has the potential to improve research and clinical care of SVP patients through the automated development of an electronic cohort for prognostication, monitoring, and management.

Keywords: single ventricle physiology, electronic health records, phenotype algorithm, cohort development

Introduction

Single ventricle physiology (SVP) represents a complex subset of congenital heart diseases (CHDs) and encompasses several endotypes, which can be nuanced. Of the 1.4 million adults and 1 million children in the United States are living with CHD,1,2 SVP lesions comprise 2%-3% of all CHD cases. Single ventricle physiology is responsible for 25%-40% of neonatal cardiac deaths and requires significant health-care resource allocation.3,4 Moreover, those who survive the neonatal period also account for significant morbidity and mortality and resource utilization well into adulthood.

The rarity and heterogeneous endotypes of SVP make it challenging for physicians to diagnose and for researchers to assemble a sufficiently large population to study disease features. Several endotypes include hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), tricuspid atresia, and double inlet left ventricle (DILV), among others. This variability complicates the process of accurately and easily classifying patients as having SVP.5 Traditional methods for identifying SVP entail clinical assessment and some form of imaging.6,7 Clinical assessments can be subjective, and imaging is occasionally suboptimal, potentially resulting in misdiagnosis.8–10 With the growing use of electronic health records (EHRs), algorithms that integrate multimodal data to phenotype disease cohorts have become more feasible.11–13 These computational methods classify and characterize individuals based on observable traits and have been applied to several disease processes, including diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and liver injury.14–16 Previous studies indicate low accuracy when the classification of SVP relies solely on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9/10) coding system.17,18

In this study, we aimed to develop an automated phenotyping algorithm for identifying patients with SVP using data from the EHR. We hypothesized the integration of ICD codes, with clinical information and imaging as cross-reference, could improve the accuracy of SVP classification. The significance of our study is 2-fold: (1) for patients with SVP, an automated rule-based, phenotyping approach that combines both structured and unstructured EHR data is feasible and ensures accurate cohort classification, reducing dependence on a single data source. (2) Our EHR phenotyping algorithm has the potential to reduce human labor typically required for traditional phenotyping approaches by automating complex data aggregation and pattern recognition.

Materials and methods

Cohort characteristics

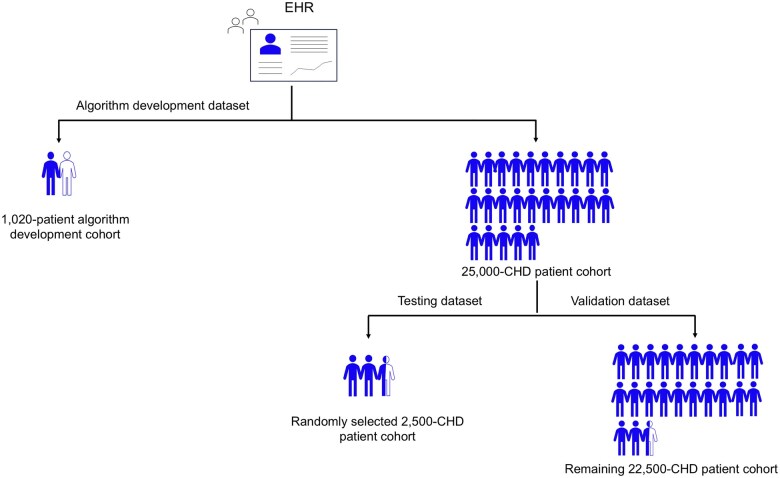

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB) with waiver of consent and was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The algorithm development dataset consisted of retrospective data from the UCLA Health EHR. Our health-care system utilizes an EHR developed by Epic. The cohort for algorithm development consisted of 1020 patients who had undergone ferumoxytol-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes 70010-76499) and were identified using the keywords “ferumoxytol,” “Feraheme,” and “Feriheme” listed in procedure note associated with imaging or individual who had undergone an MRI scan (CPT codes 70010-76499) and had ferumoxytol ordered during the same encounter between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2022. The patient group undergoing ferumoxytol-enhanced MRI was selected for convenience, and accuracy of the CPT codes could be confirmed using manually tracked data available through administrative tracking. The testing and validation datasets were drawn from an EHR cohort of 25 000 patients with clinically adjudicated CHD based on ICD-10 and ICD-9 codes (Table S1). For phenotype algorithm testing, 2500 patients were randomly selected from the 25 000 CHD cohort, and the remaining 22 500 patients were used for validation of the algorithm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of datasets used for algorithm development, testing, and validation. Each blue person tag represents 1000 patients. Abbreviations: CHD, congenital heart diseases; EHR, electronic health record.

Data preprocessing

Demographic information (age, sex, race, and ethnicity) was collected at the last clinical encounter. The data includes time-stamped encounter, diagnosis, imaging impressions, imaging narrative and provider notes, and nontime-stamped data including demographics for the algorithm development cohort and the 25 000 CHD patient cohort. Encounter diagnoses and medical conditions were documented using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, along with their respective diagnosis and entry dates. The notes for imaging data, including imaging impressions and narratives, were derived from echocardiography (echo), cardiovascular MRI, and cardiovascular computed tomography (CT). Cardiology consultation reports were identified and extracted from progress notes using keyword searches for “cardiology consultation.”

Initially, we focused on integrating imaging reports for echo, MRI, and CT, separately. To achieve this, we consolidated all imaging impressions and narratives using the procedure identifiers associated with each modality. Next, we categorized the impressions and narratives by their respective procedure identifiers. The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes were extracted from the encounter diagnoses, and demographic information (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) was retrieved from the patient demographics data.

Data processing and cleaning

We used a Python-based script for data cleaning, processing, and phenotyping analysis of EHR data and the script is available via GitHub (https://github.com/Hang1205/A-phenotyping-algorithm-for-classification-of-single-ventricle-physiology-using-EHR). Imaging impressions for echocardiograms (ECHO), MRI, and CT, along with cardiology consultation reports, were merged separately. We applied keyword searching for 9 specific terms: “Fontan,” “hypoplastic left heart syndrome,” “hypoplastic left ventricle,” “norwood,” “double inlet ventricle,” “tricuspid atresia,” “1.5 ventricle repair,” “good biventricular size,” and “bi-ventricular repair.” To enhance the accuracy of keyword searches, we incorporated synonyms, abbreviations, and variations of the terms, such as “double inlet left ventricle,” “DILV,” and “double inlet LV.” A comprehensive list of synonyms, abbreviations, and variations for the features is provided in Table S2. We formatted all text to be lowercase and eliminated irrelevant words (stop words), typos, and nonstandard medical terms to reduce noise and improve search result accuracy. Patients without notes were also considered as not containing these terms. A total of 38 features were identified, including 36 derived from four types of notes: ECHO, MRI, CT scans, and cardiology consultations, along with 2 additional features—age and left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVi). Age data were extracted from patient demographics, while the LVEDVi was calculated from MRI narratives. Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index was computed by dividing LVEDV by the body surface area (BSA). All patients in the development, testing, and validation cohorts have information for age and ICD codes. However, only 483 out of 1020 patients in the algorithm development cohort, 846 out of 2500 patients in the testing development cohort, and 6524 out of 22 500 patients in the validation development cohort had LVEDVi values. This is because MRI-derived LVEDVi was not available for patients who were not diagnosed with CHD, heart failure, structural heart diseases, or for those who had not undergone an MRI scan. Missing LVEDVi values were imputed using the average. Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index was used only if all other features were insufficient or could not provide clear identification.

Phenotype algorithm development

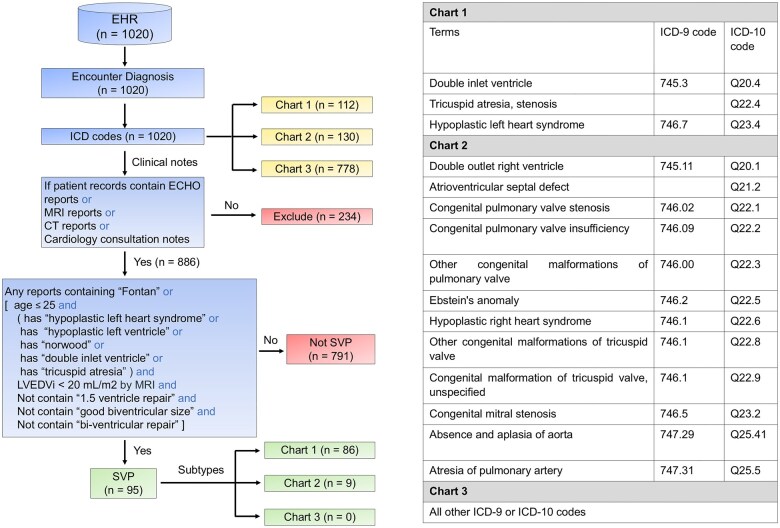

This rule-based algorithm employed a 3-step process to classify SVP patients (Figure 2). First, patients were categorized based on their ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, with those lacking clinical notes excluded from further analysis. Next, we validated the ICD codes documented in patient charts by cross-referencing them with clinical data, including keywords and findings from clinical notes, MRI reports, ECHO notes, CT notes, and cardiology consultation reports. If any clinical note met the relevant criteria, the patients were classified as having SVP. These steps were designed to ensure that the ICD code-based classification is consistent with the clinical context and diagnostic details. Our phenotyping algorithm for classifying SVP was developed using a cohort of 1020 patients who had undergone ferumoxytol-enhanced MRI scans for a variety of indications. The development cohort consisted of 95 SVP cases, all of which were reviewed and confirmed by 2 senior CHD specialists (20 years of CHD experience). Using the same development cohort, we also tested a published ICD-based method.3 Based on the insights gained from testing the published method on our data and additional clinical insights from our CHD experts for defining SVP features, we developed a new EHR phenotyping algorithm for further testing.

Figure 2.

Phenotyping algorithm development. Components from the electronic health record (EHR) used for development of phenotyping algorithm are shown. The blue boxes outline the process from EHR data to SVP classification using the rule-based phenotype algorithm. The yellow boxes highlight the outputs of the SVP classification process. The pink boxes show excluded patients and those classified as non-SVP patients. The green boxes represent the SVP patients and their respective subtypes. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ECHO, echocardiography; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LVEDVi, left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVi=LVEDV divided by body surface area); MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SVP, single ventricle physiology.

Case adjudication and confirmation

The adjudication process is shown in Figure S1. During the testing phase, 3 physicians evaluated a random sample of 2500 patients and categorized SVP status as “yes,” “no,” “possible,” or “uncertain.” In cases classified as “possible” or “uncertain,” final classification was determined in consensus by 2 CHD physicians (20 years’ and 5 years’ experience, respectively). The adjudication process incorporated data from multiple sources, including media, correspondence, ECHO images and reports, cardiology reports, CT images and reports, and MR images and reports. A total of 94 SVP cases were identified from the 2500 and served as reference cases. Based on the initial performance, the algorithm was optimized and finally validated in the remaining 22 500 holdout set of CHD patients. During the validation phase, the remaining 22 500 CHD patients were classified using our proposed phenotype algorithm. The total cases classified by both the phenotyping algorithm (n = 680 cases) and the ICD-based classification method (n = 1658) were reviewed and confirmed by 3 physicians, with final validation conducted by a senior CHD physician (20 years’ experience).

Evaluation metrics for algorithm testing and validation

Model performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall (sensitivity), and F1 score (Python, scikit-learn library). Accuracy measures the overall proportion of correct predictions. Precision indicates the ratio of correctly predicted positive instances to the total predicted positive instances. Sensitivity reflects the ratio of correctly predicted positives to the total actual positives. The F1 score is the weighted harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity, providing a balanced measure of both metrics.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess feature contributions to the phenotyping algorithm’s performance, we conducted sensitivity analysis using an XGBoost model (Python libraries, scikit-learn) and SHAP values.19 A total of 38 features along with the SVP labels served as inputs to the XGBoost model.

Results

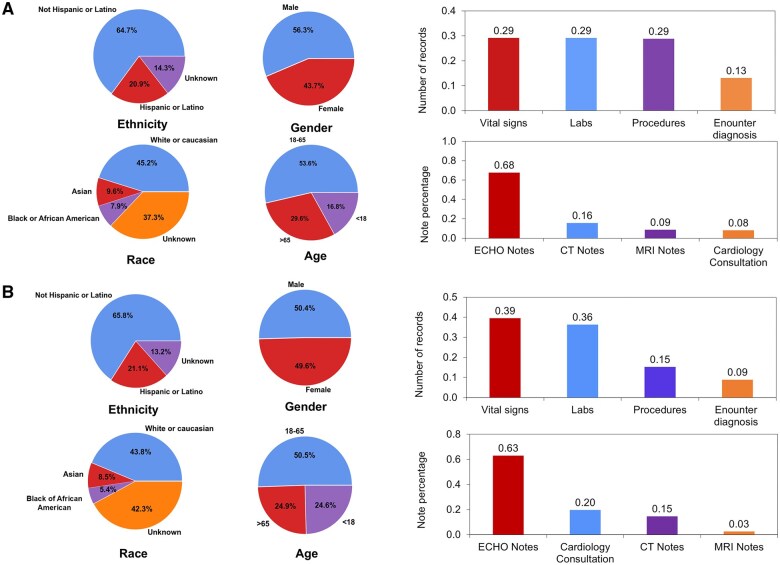

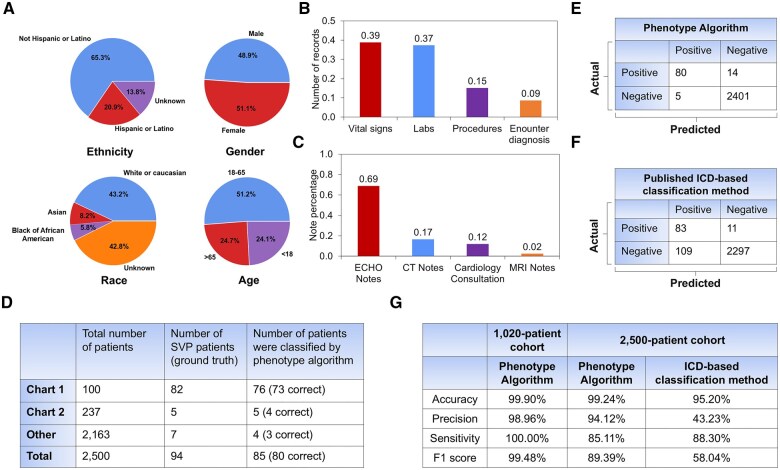

Demographic characteristics of our algorithm development cohort and our testing/validation cohort, along with a summary of data distribution, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cohort demographics and summary of data distribution for the algorithm (A) development cohort and (B) testing/validation cohort. The development cohort consisted of n = 1020 patients who had undergone ferumoxytol-enhanced MRI. The testing/validation cohort consisted of 25 000 random patients with congenital heart disease (CHD). The 25 000 CHD patient cohort generated a total of 231 838 clinical notes including echo/MRI/CT reports, and cardiology consultation notes. Distribution of patients by ethnicity, gender, age, and race are shown. The percentage of records containing vital signs, labs, procedures, and encounter diagnosis, as well as percentage of notes derived from echo/MRI/CT reports, and cardiology consultation notes are summarized.

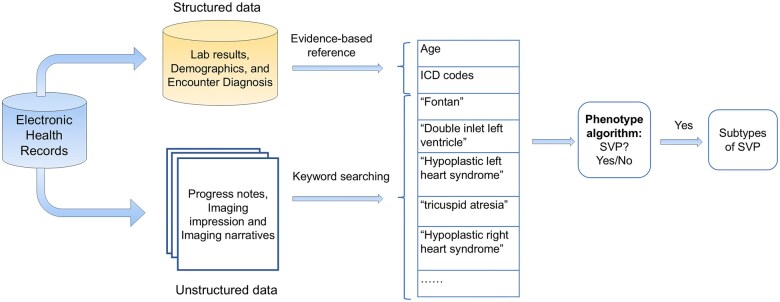

Our classification of SVP is based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes extracted from EHR data (Figure 4). The EHR dataset included both structured data—such as demographics, encounter diagnoses, and ICD codes—and unstructured data, including text from imaging reports (ECHO impressions and narratives, MRI impressions and narratives, CT impressions and narratives), and cardiology consultation notes. These features were used by the phenotyping algorithm to classify the presence of SVP. In total, 3 605 603 records were collected. A total of 14 123 clinical notes were gathered.

Figure 4.

Summary of feature extraction used in algorithm development. The electronic health records consisted of both structured and unstructured data. Features and keywords were extracted for the development of the phenotype algorithm.

Development of the phenotyping algorithm for SVP

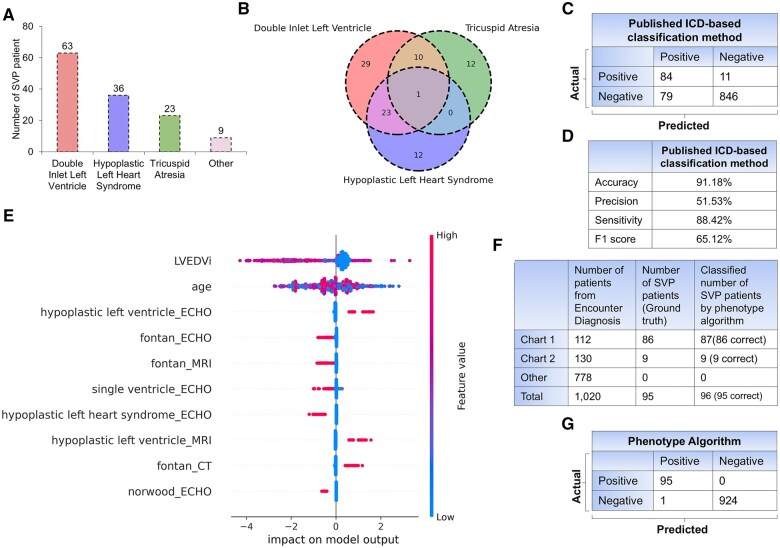

The algorithm development cohort had 95 patients with SVP. To analyze the distribution of endotypes, we ranked them according to 3 primary defects: DILV, HLHS, and tricuspid atresia (Figure 5A). DILV may be overrepresented in our algorithm development cohort. The expected prevalence in the population is: DILV (5-10 of 100 000),20 HLHS (8-25 of 100 000),21 and tricuspid atresia (2-7 of 100 000).22 We examined the overlap among these 3 defects by creating a 3D Venn diagram, which showed both overlapping and distinct cases (Figure 5B). Results from the reference published ICD-based classification method for identifying SVP are shown in Figure 5C.17 The published method predicted 84 out of the 95 SVP cases, while 11 cases were false negatives, and 79 were false positives. The overall accuracy of the published classification method was 91.18%, with a precision of 51.53%, sensitivity (recall) of 88.42%, and an F1 score of 65.12% (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Phenotype algorithm development cohort and their performance metrics (n = 1020). (A) Distribution of SVP patients categorized by the 3 main types of SVP diagnosis (double inlet left ventricle, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and tricuspid atresia). (B) Overlap among the 3 main types of SVP diagnosis. (C) Confusion matrix and (D) performance metrics for the published ICD-based classification method using the development cohort. (E) The Beeswarm plot summarizes the contribution of the top 10 features in the development data set, ranked by the mean absolute SHAP values, that significantly influenced the phenotyping algorithm. (F) Comparison between the total number of patients, actual SVP patients, and SVP patients identified by the phenotyping algorithm across Chart 1, Chart 2, and other ICD code groups. (G) Confusion matrix illustrating the performance of the proposed phenotyping algorithm. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ECHO, echocardiography; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LVEDVi, left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

To enhance classification accuracy, we informed the ICD-based method with expert physician insight to create our new phenotype algorithm. A total of 234 patients were excluded due to the absence of clinical notes, including MRI reports, ECHO notes, CT scans, and cardiology consultation reports. To illustrate the contribution of features in the phenotyping algorithm, Shapley values for the top 10 out of 38 features were computed (Figure 5E). Using ICD codes in Chart 1 (Figure 1), we identified 112 patients. However, our expert physicians confirmed 86 of the 112 patients as having SVP. Further modifications ultimately allowed the algorithm to classify 87 patients as SVP. The discrepancy between patients labeled by the ICD codes and the physician-confirmed diagnoses was attributed to mislabeling of the encounter diagnoses. We identified 2 cases of HLHS who were over 30 years old and did not undergo the Fontan procedure. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome patients, by definition, have SVP. If they have not had the Fontan procedure, then something unusual has occurred in their history (eg, lost to follow up, too high risk for Fontan, declined Fontan, etc.). These 2 patients were considered too high risk to undergo a Fontan procedure. In the development of our algorithm, we considered those patients with SVP who underwent heart transplantation as having a “history of SVP” because their long-term risk profile differs from noncongenital patients. We identified 6 SVP patients who underwent heart transplantation. In 130 SVP cases identified using ICD codes in Chart 2 (Figure 1), only 9 cases were confirmed to be SVP by our expert physicians. Our algorithm accurately identified all 9 cases (Figure 5F). No additional SVP cases were found using the other ICD codes. The performance metrics of the algorithm development cohort demonstrated high accuracy, with only 1 case misclassified (Figure 5G).

Testing of the proposed phenotyping algorithm (n= 2500 CHD)

Demographics of the test cohort are shown in Figure 6A. A total of 7 612 305 records were collected with vital signs, lab results, procedures, and encounter diagnoses (Figure 6B) and 20 373 clinical notes were extracted including echocardiogram reports, MRI notes, CT notes, and cardiology consultation notes (Figure 6C). A summary of our findings in the test cohort using the proposed phenotyping algorithm is shown in Figure 6D. In Chart 1, our proposed phenotype algorithm classified 76 of the 100 CHD patients as SVP, with 73 cases correctly classified and 3 cases misclassified. In Chart 2, our proposed phenotyping algorithm classified 5 of the 237 CHD patients as SVP, with 4 cases correctly classified and 1 case misclassified. Among 2163 patients with ICD codes not listed in Chart 1 and Chart 2, a total of 7 cases were confirmed as SVP. The proposed algorithm classified 4 cases as SVP, with 3 correctly classified and 1 misclassified. Performance characteristics of our phenotype algorithm relative to the published ICD-based classification method are shown in Figure 6E and F.17 Our proposed phenotyping algorithm classified 85 of the 2500 CHD patients as SVP, with 80 true positives, 2401 true negatives, 14 false negatives, and 5 false positives. The published ICD method classified 192 cases as SVP, with 83 true positives, 2297 true negatives, 11 false negatives, and 109 false positives. Based on precision, accuracy, recall, and F1 scores, the proposed algorithm performed exceptionally well (Figure 6G). Although the published ICD-based classification method demonstrated a slightly higher precision score, its overall accuracy, sensitivity, and F1 score were significantly lower than those of the proposed phenotyping algorithm.

Figure 6.

Test performance of the proposed phenotyping algorithm. (A) Cohort demographic distribution. (B) Percentage of records with vital signs, labs, procedures, and encounter diagnosis. (C) Percentage of clinical notes including echo reports, cardiology consultation notes, CT reports, and MRI reports. (D) Summary of the total number of SVP patients from Encounter Diagnosis confirmed SVP patients, and those classified by the phenotyping algorithm across Chart 1, Chart 2, and other groups. (E) Confusion matrix demonstrating the performance of the phenotyping algorithm in n = 2500 CHD patients. (F) Confusion matrix demonstrating the performance of the published ICD-based classification method in the same cohort. (G) Performance evaluation metrics for the phenotyping algorithm in both the development cohort (n = 1020) and the test cohort (n = 2500 CHD patients) cohort relative to the performance of the published ICD-based method.

Validation of the phenotyping algorithm

After testing our algorithm, we validated our phenotyping algorithm to the remaining 22 500 CHD patients. Demographics of this larger cohort are shown in Figure S2A. A total of 64 344 748 records were extracted with vital signs, lab results, procedures, and encounter diagnoses (Figure S2B) and 212 360 clinical notes were collected including echocardiogram reports, MRI notes, CT notes, and cardiology consultation notes (Figure S2C). Using ICD codes in Chart 1 (Figure 1), we identified 808 patients, of which 603 were classified as SVP patients using the phenotyping algorithm. Using ICD codes in Chart 2, we identified 2119 patients, of which 60 were classified as SVP. Of the 19 573 patients with ICD codes not included in Chart 1 or 2, 16 cases were confirmed as SVP (Figure S2D). Of the 680 cases classified by our phenotype algorithm as SVP, a total of 638 cases were confirmed as SVP by our expert physicians. A total of 1658 cases were classified as SVP using the ICD-based classification method, with 713 cases confirmed as SVP by our expert physicians. Our phenotype algorithm achieved a significantly higher precision of 93.82%, surpassing the ICD-based classification method, which had a precision of 43.00% (Figure S2E). Single ventricle physiology endotypes (DILV, HLHS, and tricuspid atresia) identified by encounter diagnosis relative to the proposed phenotype algorithm are shown in Figure S2F.

Discussion

To accurately classify CHD patients with SVP, we developed a phenotyping algorithm that integrates ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes with clinical notes extracted from EHR. Our proposed algorithm demonstrated high accuracy and precision in classifying SVP, while maintaining high sensitivity and F1 scores. Compared to the published ICD-based classification method,17 our algorithm was more effective at identifying false positives through cross-referencing with unstructured data from clinical notes and could detect SVP cases that might be missed due to absent or erroneous ICD codes. This capability mitigated the critical limitation of traditional ICD coding, where cases may be missed due to absent or erroneous coding. The proposed phenotyping algorithm based on multimodal data significantly enhances the classification of SVP and has potential to facilitate more precise diagnosis and tailored management strategies.

Cohort discovery tools such as the Informatics for Integrating Biology and the Bedside and the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model are widely used frameworks for organizing and analyzing health data.23,24 However, there are no established standardized methods for cohort discovery in SVP. Our proposed approach is complementary to these existing tools. Integration of our phenotype algorithm into these platforms would improve the accuracy and sensitivity of SVP cohort identification. Our automated EHR-based phenotype algorithm effectively addressed critical limitations inherent in conventional classification methods that rely solely on ICD codes or expert judgment, both of which often lack cross-validation and are prone to mislabeling.17,18 A previous study demonstrated that using phenotype algorithms with multiparametric data can accurately differentiate between subtypes of dilated cardiomyopathy.25 Furthermore, another application of phenotype algorithms for identifying atrial fibrillation achieved an impressive sensitivity of 95.5%.26 Consistent with these findings, our phenotype algorithm achieved high accuracy (99.24%) and precision (94.12%) in the testing cohort. In the development of our phenotype algorithm, we employed a top-down approach to identify relevant terms (unstructured data) from clinical notes specific to SVP, incorporating an MRI-derived left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVi) cutoff as a crucial trait for SVP screening.27 By cross-referencing clinical notes with ICD diagnoses, our algorithm effectively identified false positives and detected SVP cases that may otherwise be overlooked due to absent or erroneous coding. This approach not only streamlines the classification process but has the potential to help ensure that patients receive care tailored to their specific conditions, ultimately enhancing resource allocation within health-care systems.

One significant advantage of our study was the involvement of clinical CHD experts in the adjudication process. Single ventricle physiology case adjudication by CHD specialists in large cohorts is challenging, as it is time-consuming, and the complexity of SVP conditions is high. Review of both the 1020-development cohort and the 2500 CHD test cohort was time-intensive and required careful coordination among CHD specialists and clinical physicians. We found the time investment by our CHD experts and clinical physicians to be valuable in lending confidence for the diagnosis of SVP in our ground truth datasets and for the purpose of testing and validation of our algorithm.

Our study also clearly delineated the criteria for identifying SVP cases, providing specific reasons for each classification decision. While many machine learning and deep learning approaches have been employed for disease classification using EHR,28–31 our phenotype algorithm offered a distinct advantage with its transparent definition of SVP classification, making it straightforward and easy to follow compared to more complex machine learning and deep learning methods.

Our algorithm has several limitations. First, there were some exceptional cases that posed challenges for our algorithm. For instance, some patients had their SVP diagnosis documented in neurology reports, which the algorithm was unable to identify due to misdocumentation of their condition. Additionally, patients who were referred to our institution only for heart transplantation often lacked essential records, such as ECHO, MRI, CT scans, and cardiology consultation notes, making it difficult to confirm whether they should be classified as SVP. Furthermore, clinical notes for certain transferring patients from outside our medical system were unavailable, preventing their classification as SVP in the absence of supporting clinical evidence. We also included MRI-derived LVEDV index in our analysis; however, this parameter is still under investigation for the classification of SVP and well-accepted cutoffs are not yet clearly established. Moreover, the focus of our algorithm is for classification of a rare subtype in complex CHD and is not meant to be generalizable for other diagnoses beyond the context of SVP. This is purely intentional for the purpose of establishing and standardizing a set of criteria to study patients with SVP. The data used in our algorithm is reflective of those from a quaternary referral center with dedicated expertise in CHD and thus the prevalence of SVP cases is higher than that of a general health-care system without expertise in CHD.

Another limitation of our study is the lack of external validation, which relates to widespread variations in data quality, coding systems, and clinical protocols across institutions, and can introduce site-specific biases, potentially compromising the accuracy of cohort identification. Differences in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of patient populations can also influence disease prevalence, further affecting the algorithm’s performance across diverse settings. To mitigate these challenges, future validation of the algorithm using external cohorts will be critical for evaluating its robustness and refining its performance for broader applicability. Successful validation could facilitate broader clinical application and assessment of the natural history, ultimately improving patient management across the spectrum of CHD subtypes.

Conclusions

Our automated SVP phenotyping algorithm employs multimodal features based on ICD codes, subspecialty physician classification, imaging reports, and physician consultation notes and demonstrates excellent performance. Its implementation has high potential to facilitate the development of an electronic cohort for disease prediction and management. Further external validation is needed to demonstrate the full extent of clinical impact.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Hang Xu, Division of Cardiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States; Department of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States; Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Pierangelo Renella, Department of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States; Division of Pediatric Cardiology, University of California Irvine and Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Irvine, CA 92868, United States.

Ramin Badiyan, Division of Pediatric Cardiology and Mattel Children’s Hospital, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Ziad R Hindosh, Division of Cardiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Francisco X Elisarraras, Division of Cardiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Bing Zhu, Department of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Gary M Satou, Division of Pediatric Cardiology and Mattel Children’s Hospital, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Majid Husain, Division of Pediatric Cardiology and Mattel Children’s Hospital, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

J Paul Finn, Department of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

William Hsu, Department of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States; Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Kim-Lien Nguyen, Division of Cardiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States; Department of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States; Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States.

Author contributions

Hang Xu (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft), Pierangelo Renella (Methodology, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Ramin Badiyan (Validation), Ziad R. Hindosh (Validation), Francisco X. Elisarraras (Validation), Bing Zhu (Conceptualization, Methodology), Gary M. Satou (Validation), Majid Husain (Validation), J. Paul Finn (Investigation, Resources, Funding acquisition), William Hsu (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing), and Kim-Lien Nguyen (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing)

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at JAMIA Open online.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL127153 and UL1TR001881).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no competing interests relevant to this study.

Data availability

Patient-level data from the UCLA Health EHR system are not available due to patient privacy concerns and access restrictions. However, upon approval from the UCLA ULEAD team, access to data may be available to qualified investigators through a collaborative effort for a specified project.

References

- 1. Lee SM, Kwon JE, Song SH, et al. Prenatal prediction of neonatal death in single ventricle congenital heart disease. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36:346-352. 10.1002/pd.4787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilboa SM, Devine OJ, Kucik JE, et al. Congenital heart defects in the United States. Circulation. 2016;134:101-109. 10.1161/circulationaha.115.019307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rusin CG, Acosta SI, Vu EL, Ahmed M, Brady KM, Penny DJ. Automated prediction of cardiorespiratory deterioration in patients with single ventricle. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:3184-3192. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barron DJ, Kilby MD, Davies B, Wright JG, Jones TJ, Brawn WJ. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Lancet. 2009;374:551-564. 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60563-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rao PS. Single ventricle—a comprehensive review. Children. 2021;8:441. 10.3390/children8060441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Edwards RM, Reddy GP, Kicska G. The functional single ventricle: how imaging guides treatment. Clin Imaging. 2016;40:1146-1155. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kutty S, Rathod RH, Danford DA, Celermajer DS. Role of imaging in the evaluation of single ventricle with the Fontan palliation. Heart. 2016;102:174-183. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cashen K, Gupta P, Lieh-Lai M, Mastropietro C. Infants with single ventricle physiology in the emergency department: are physicians prepared? J Pediat. 2011;159:273-277.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwartz SM, Dent CL, Musa NL, Nelson DP. Single-ventricle physiology. Crit Care Clin. 2003;19:393-411. 10.1016/s0749-0704(03)00007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohye RG, Schonbeck JV, Eghtesady P, et al. ; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators. Cause, timing, and location of death in the single ventricle reconstruction trial. J Thorac Cardiovas Surg. 2012;144:907-914. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mo H, Thompson WK, Rasmussen LV, et al. Desiderata for computable representations of electronic health records-driven phenotype algorithms. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:1220-1230. 10.1093/jamia/ocv112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carrell DS, Floyd JS, Gruber S, et al. A general framework for developing computable clinical phenotype algorithms. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31:1785-1796. 10.1093/jamia/ocae121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang S, Varghese P, Stephenson E, Tu K, Gronsbell J. Machine learning approaches for electronic health records phenotyping: a methodical review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2023;30:367-381. 10.1093/jamia/ocac216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esteban S, Tablado MR, Peper FE, et al. Development and validation of various phenotyping algorithms for diabetes mellitus using data from electronic health records. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2017;152:53-70. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tison GH, Chamberlain AM, Pletcher MJ, et al. Identifying heart failure using EMR-based algorithms. Int J Med Inform. 2018;120:1-7. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Overby CL, Pathak J, Gottesman O, et al. A collaborative approach to developing an electronic health record phenotyping algorithm for drug-induced liver injury. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013; 20: e243-e252. 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruiz VM, Goldsmith MP, Shi L, et al. Early prediction of clinical deterioration using data-driven machine-learning modeling of electronic health records. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;164:211-222.e3. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.10.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo Y, Al‐Garadi MA, Book WM, et al. Supervised text classification system detects Fontan patients in electronic records with higher accuracy than ICD codes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e030046. 10.1161/jaha.123.030046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tarabanis C, Kalampokis E, Khalil M, Alviar CL, Chinitz LA, Jankelson L. Explainable SHAP-XGBoost models for in-hospital mortality after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Digit Health J. 2023;4:126-132. 10.1016/j.cvdhj.2023.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gidvani M, Ramin K, Gessford E, Aguilera M, Giacobbe L, Sivanandam S. Prenatal diagnosis and outcome of fetuses with double-inlet left ventricle. AJP Rep. 2011;1:123-128. 10.1055/s-0031-1293515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Öhman A, El‐Segaier M, Bergman G, et al. Changing epidemiology of hypoplastic left heart syndrome: results of a national Swedish cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010893. 10.1161/jaha.118.010893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weld J, Lee B, Loomba RS, et al. Tricuspid atresia and common arterial trunk: a rare form of CHD. Cardiol Young. 2023;33:1192-1195. 10.1017/s1047951122003602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murphy SN, Weber G, Mendis M, et al. Serving the enterprise and beyond with informatics for integrating biology and the bedside (i2b2). J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:124-130. 10.1136/jamia.2009.000893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Makadia R, Ryan PB. Transforming the premier perspective® hospital database into the observational medical outcomes partnership (OMOP) common data model. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2014;2:1110. 10.13063/2327-9214.1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tayal U, Verdonschot JAJ, Hazebroek MR, et al. Precision phenotyping of dilated cardiomyopathy using multidimensional data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:2219-2232. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.03.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chamberlain AM, Roger VL, Noseworthy PA, et al. Identification of incident atrial fibrillation from electronic medical records. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023237. 10.1161/jaha.121.023237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lam CZ, Nguyen ET, Yoo SJ, Wald RM. Management of patients with single-ventricle physiology across the lifespan: contributions from magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38:946-962. 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perry J, Brody JA, Fong C, et al. Predicting out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the general population using electronic health records. Circulation. 2024;150:102-110. 10.1161/circulationaha.124.069105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rajkomar A, Oren E, Chen K, et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:18. 10.1038/s41746-018-0029-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gianfrancesco MA, Tamang S, Yazdany J, Schmajuk G. Potential biases in machine learning algorithms using electronic health record data. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1544-1547. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong J, Horwitz MM, Zhou L, Toh S. Using machine learning to identify health outcomes from electronic health record data. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5:331-342. 10.1007/s40471-018-0165-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Patient-level data from the UCLA Health EHR system are not available due to patient privacy concerns and access restrictions. However, upon approval from the UCLA ULEAD team, access to data may be available to qualified investigators through a collaborative effort for a specified project.