Abstract

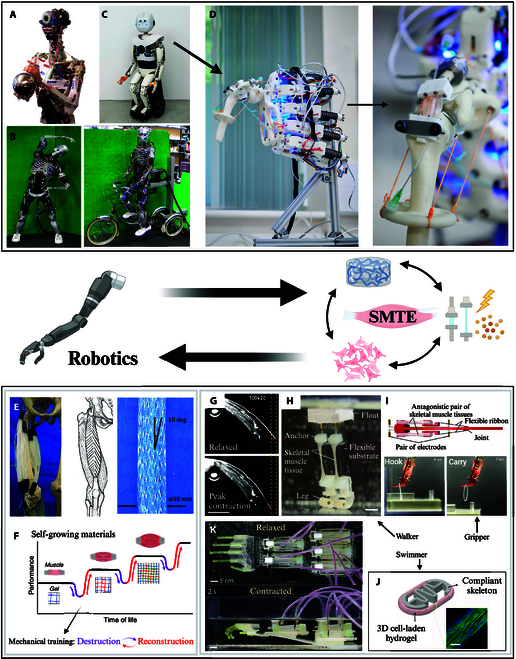

With its remarkable adaptability, energy efficiency, and mechanical compliance, skeletal muscle is a powerful source of inspiration for innovations in engineering and robotics. Originally driven by the clinical need to address large irreparable muscle defects, skeletal muscle tissue engineering (SMTE) has evolved into a versatile strategy reaching beyond medical applications into the field of biorobotics. This review highlights recent advancements in SMTE, including innovations in scaffold design, cell sourcing, usage of external physicochemical cues, and bioreactor technologies. Furthermore, this article explores the emerging synergies between SMTE and robotics, focusing on the use of robotic systems to enhance bioreactor performance and the development of biohybrid devices integrating engineered muscle tissue. These interdisciplinary approaches aim to improve functional recovery outcomes while inspiring novel biohybrid technologies at the intersection of engineering and regenerative medicine.

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is a highly differentiated and organized tissue that makes up over 40% of human body weight [1–3]. It converts chemical energy into mechanical energy to generate force, maintain posture, and produce movement [4]. As an actuation system, skeletal muscle possesses unique characteristics, such as mechanical compliance, energy efficiency, fine motor control, and adaptability through training, allowing it to perform a wide range of tasks requiring varying levels of precision and strength [5]. Remarkably, skeletal muscle has a strong ability to regenerate. Thus, for most muscle injuries, rest and rehabilitation are enough to allow muscle tissue to repair itself naturally. Despite this remarkable regeneration capacity, substantial volumes of muscle loss do not naturally recover and require interventional support. When volumetric muscle loss (VML) surpasses 15% to 20%, patients currently have no alternative but to undergo an autologous muscle flap graft [3,6]. Although this procedure is the gold standard for the treatment of VML, it is associated with major drawbacks including donor site availability and morbidity, extensive surgery time, limited functionality, and risk of graft failure [7] Additional details about VML can be found in Box 1.

Box 1. .

VML epidemiology and clinical need

The incidence of musculoskeletal pathologies is on the rise, driven by the expanding aging population [8]. In the last 30 years, the burden of musculoskeletal disorders has surged by over 30%. These conditions substantially impair movement and coordination, leading to premature exit from the workforce, diminished overall health, and limited engagement in community life. Affecting roughly 1.71 billion individuals, they represent the leading cause of disability worldwide [9]. Musculoskeletal disorders encompass more than 150 different conditions, affecting bones, joints, ligaments, tendons, and muscles [10]. VML injuries are a widespread category of muscle afflictions, associated with an extensive loss of function. Indeed, a loss of muscle weight as small as 10% to 20% can cause a 30% to 90% loss of muscle overall strength [11]. VML can have various causes including crush injuries, penetrative trauma and blast, burns, surgical resection of aggressive malignant tumor, secondary trauma-like compartment syndrome, and comorbidity to open bone fracture [7]. Affecting all age categories, VML causes permanent loss of muscle strength and range of motion, associated with long-term inflammation and extensive fibrosis [12]. These manifestations of VML injuries can lead to chronic disability and overall lower physical activity levels, which then contribute to a general health decline in patients. As there are currently no satisfactory treatments available for VML, there is a clinical need for the development of novel therapies that will allow for a full restoration of muscle function following VML injuries.

The development of engineered muscle grafts presents a promising alternative strategy to tackle those shortcomings [3,6]. Producing such muscle tissue constructs is the main focus of the field of skeletal muscle tissue engineering (SMTE). The general SMTE approach consists of utilizing bioreactor systems to generate tissue in vitro using scaffolds, human or animal cells, and appropriate growth conditions (i.e., chemical environment and relevant external stimuli) [13,14]. While the intricate interplay between these various parameters makes the production of healthy and functional skeletal muscle tissue in vitro an ongoing challenge, current SMTE approaches provide exciting opportunities for medical applications. Beyond regenerative medicine, engineered muscle constructs also hold considerable potential in biorobotics. This emerging interdisciplinary field merges principles from robotics, biology, and engineering to develop robotic systems that either take inspiration from biological structures or directly incorporate living components. While “biorobotics” has been defined in various ways, including as “the science and engineering of applying robotics to problems regarding biology and medicine” [15], the definition that best aligns with the scope of this review emphasizes the integration of biological materials, systems, and principles into robotic technology [16]. Within the context of SMTE, biorobotics encompasses both bioinspired robots that replicate muscle-like actuation and biohybrid robots that integrate engineered skeletal muscle tissue into artificial frameworks, creating adaptive systems with enhanced functionality and responsiveness [5]. Successfully integrating engineered muscle into robotic systems requires careful optimization of all core components of SMTE to achieve the desired properties for specific applications. Among these components, scaffold design is particularly critical, as the mechanical properties, porosity, and biodegradability of the scaffold directly influence the structural integrity and contractile performance of the engineered muscle tissue. The selection of the cell type is also a key consideration to achieve cost-effective long-term scale-up of production while maintaining ethical standards. Additionally, bioreactor design plays a fundamental role throughout the lifespan of integrated muscle constructs. In the early stages, bioreactors provide a controlled environment that supports the development of functional, contractile muscle tissue. Bioreactor chambers, which effectively host tissue constructs, should ensure their long-term sterility and sustained functionality.

This intersection between SMTE and robotics not only advances regenerative medicine but also opens new possibilities for both medical and technological applications. In this context, this review aims to discuss the current trends in SMTE. After outlining the hierarchical structure of skeletal muscle and its natural regeneration pathways, the strategies developed for engineering skeletal muscle will be reviewed, with an emphasis on 3 key domains: scaffold production, cell types, and the role of external stimuli in tissue maturation. Particular attention will be given to the bioreactor systems that support the growth and development of engineered muscle. Additionally, this review will explore the complementary relationship between SMTE and robotics, highlighting the promising contribution of advanced robotic platforms, such as humanoid robots, in providing relevant stimulations to engineered muscle constructs, as well as the current advances in the development of engineered skeletal muscle-actuated biohybrid robots.

Skeletal Muscle Structure and Function

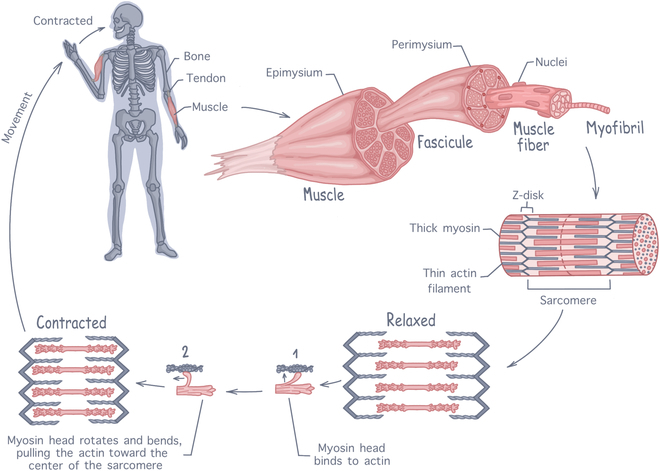

Skeletal muscle is a complex tissue, with a highly organized 3-dimensional (3D) structure intimately linked to its main function: generating force to produce movement [2]. There are over 400 distinct skeletal muscles in the human body, attached to the skeleton by tendons to transmit the generated forces into motion. As shown in Fig. 1, each individual muscle is encapsulated by the epimysium, a dense connective tissue (made of coarse collagen fibers) that protects the organ and passively participate in force transmission [17]. The muscle in itself is composed of muscle fiber (myofibers) bundles, called fascicles, that are each surrounded by another layer of connective tissue, the perimysium. Each myofiber is a highly specialized, elongated, and multinucleated muscle cell, formed by the fusion of undifferentiated muscle cells (myoblasts). Each fiber contains hundreds of nuclei, located at the periphery of the cells, and thousands of long protein filaments arranged in parallel forming rod-like organelles called myofibrils. Myofibrils are the contractile machinery of the myofibers and can make up to 75% of a muscle’s total volume. They are made up of repeating fundamental units called sarcomeres. Each sarcomere consists of an alternating arrangement of thick myosin filaments overlapping with thin actin filaments, which are laterally delimitated by plate-like structure called Z-disks [18]. At the molecular level, sarcomeric contraction is a movement of the myosin heads onto the thin actin filaments. For a muscle fiber to contract, the myosin heads must first be activated by ATP (adenosine triphosphate), with each head binding one ATP molecule and hydrolyzing it to ADP (adenosine diphosphate). The energy released from this hydrolysis is transferred to the myosin head, allowing it to bind to the actin filament. Upon binding, energy is released causing the myosin head springs back, dragging the bound actin filament along. This dragging movement, referred to as the power stroke, is the origin of muscle contraction [4]. During contraction, power strokes occur at a rate of ∼17 s−1, with myosin propelling actin at a velocity of ∼310 nm/s [19]. Notably, increasing load can accelerate this process [20].

Fig. 1.

Anatomy of skeletal muscle tissue, illustrating the hierarchical structure from whole muscle down to sarcomeres. The contraction process involves interactions between actin and myosin filaments within the sarcomeres to generate force.

To enable voluntary movement, skeletal muscle is a densely innervated tissue, with motor neurons extending from the central nervous system into the muscle tissue to establish contact with each myofibers at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) [2,7]. When action potentials are produced, acetylcholine is released and binds to myofibers, depolarizing the cellular membranes and initiating the release of calcium ions within the myofibrils. Calcium ions then bind to the actin filaments, modifying their configuration to expose the myosin-binding sites, which initiate muscle contraction [21]. To meet the considerable metabolic needs created by contractions, skeletal muscle is highly vascularized. Its features a dense capillary network aligned alongside muscle fibers (with around 600 capillaries per millimeter), capturing around 25% of the resting cardiac output, and facilitating efficient exchange of nutrients and oxygen [2].

On top of the dynamic structures formed by myofibrils, skeletal muscle contraction is also sustained by its passive highly organized connective tissue structures. The skeletal muscle extracellular matrix (ECM) forms the supportive network that maintains muscle shape and structural integrity. It enables uniform distribution and force transmission within the muscle and to the tendon, playing an important role in muscle elasticity and allowing the synergic contraction of myofibers during movement [22]. Collagen is the main structural protein in skeletal muscle ECM, accounting for up to 10% of the muscle dry weight, with type I and III being the most abundant. Other ECM proteins include laminin, elastin, fibronectin, and other various proteoglycans [23]. Additionally, by binding nonmatrix molecules such as growth factors, the ECM also creates a dynamic signaling environment essential for muscle growth, regeneration, and homeostasis [24].

Skeletal muscles have an innate remarkable capacity for regeneration, due mostly to the presence of muscle stem cells, also known as satellite cells, in grooves lateral to the longitudinal axis of the muscle fibers [8]. Upon activation, satellite cells can proliferate and differentiate into myoblasts, which will then mature into fully functional myofibers. Therefore, when compared to other closely related tissues such as tendons or ligaments, skeletal muscle stands out by its high repair speed. Within a few weeks after injury, full functional repair can be achieved following a highly orchestrated regeneration process. This process can be divided in 3 main phases [1,25]: (a) a degenerative and inflammatory phase, associated with muscle cell necrosis, hematoma formation, and immune cells invasion; (b) a regenerative phase, consisting of phagocytosis of the necrotic muscle tissue, ECM deposition, and satellite cell activation and proliferation to initiate myofiber regeneration; (c) a remodeling and maturation phase, where functional recovery is reached by including reorganization of the scar tissue, ECM remodeling, maturation of myofibers, angiogenesis, and innervation. For most skeletal muscle injuries, this natural regeneration process is sufficient to allow the tissue to completely recover and regain full functionality [24]. However, when substantial damage is sustained, or in cases of muscle-wasting diseases, this regeneration process is not enough to prevent permanent muscle loss, scar tissue formation, and irreversible loss of function. Several therapeutic strategies are currently being investigated to promote skeletal muscle regeneration, among which SMTE is emerging as a promising approach.

Conventional SMTE

SMTE is an interdisciplinary field that aims at producing healthy and functional skeletal muscle. The conventional SMTE strategy consists of utilizing bioreactor systems to generate muscle tissue in vitro using scaffolds, human or animal cells, and appropriate growth conditions (i.e., chemical environment and relevant external stimuli) [13,14]. While the intricate interplay between these various parameters makes the production of skeletal muscle tissue in vitro an ongoing challenge, current SMTE approaches provide exciting opportunities for medical applications. To be of interest for clinical use, engineered skeletal muscle needs to fulfill an array of criteria. It needs to be of relevant shapes and sizes, have contractile ability, incorporate itself to the native muscle upon implantation, sustain innervation and vascularization to enable full functionality recovery, etc. In the current state of the SMTE field, most of those specifications remain challenges to be solved. Research mainly focuses on 4 areas: the choice of the scaffold used, of the type of cells cultured, of the stimuli applied, and of the bioreactor in which the tissue maturation happens. Here, an overview of the current strategies explored to address the current limitations of SMTE is proposed.

Scaffolds

In tissue engineering, scaffolds are temporary structures that support cell growth and 3D development during the tissue developmental stage [1]. To properly guide cells and promote tissue neogenesis, scaffolds need to possess some chemical, mechanical, and structural characteristics that are specific to the target tissue. For SMTE, an ideal scaffold should (a) be biocompatible, (b) biodegrade, with a degradation rate matching the speed of tissue neogenesis, (c) have a stiffness mimicking the one of native skeletal muscle (10 to 20 kPa), and (d) promote myoblast growth, differentiation, and alignment [11]. Examples of existing SMTE scaffolds can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of scaffolds used in SMTE.

| Origin | Material | Description | Mechanical properties | Cell interaction | Biodegradability | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing techniques | Scaffold description | Modulus | Adhesion | Differentiation | |||||

| Synthetic | PCL | Polycaprolactone | Electrospinning | Aligned PCL fibers, 0.7 μm diameter | 75 MPa | Supports satellite cell adhesion, alignment, and growth | Increased myogenic gene expression at day 4 | X | [142] |

| 3D bioprinting | PCL fiber bundles, 10 μm diameter, plasma treated | 25 MPa | Supports myoblast adhesion, proliferation, and alignment | Supports myotube formation, with increased myogenic activity from day 14 | No significant degradation after 3 weeks in PBS, 37 °C | [143] | |||

| Freeze-drying | PCL microparticles functionalized with polyPEGMA | 10 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion and promotes proliferation | Supports myotube formation, with up-regulated myogenic markers | X | [144] | |||

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) | Electrospinning | Aligned PLGA fibers | 750 MPa | Supports and promotes myoblast adhesion and elongation | Enhances myoblast fusion from 14 d | X | [145] | |

| Randomly oriented PLGA fibers, with or without added collagen | 149 MPa | Promotes myoblast adhesion and elongation | Limited myoblast fusion on PLGA scaffold, but enhances fusion and myogenic gene expression with the addition of collagen | X | [146] | ||||

| 3D bioprinting | E-jet printed PLGA multilayer scaffold with 50-μm fibrillar gap | X | Enhances myoblast adhesion and proliferation | Supports myotube formation, with increased myogenic gene expression | X | [65] | |||

| Freeze-drying | Plasma-treated PLGA scaffold | X | Supports myoblast adhesion and proliferation in vitro for 48h | Not directly investigated. In vivo experiments show new tissue growth on scaffold 7 d post-implantation |

No significant weight loss at 28 d in PBS, 37 °C | [147] | |||

| Hydrogel casting | Microgrooved PLGA hydrogel | X | Promotes myoblast adhesion, enhanced proliferation with wider grooves | Large grove widths and shallow groove depths promote myotube formation and alignment | X | [148] | |||

| PEGDA | Polyethylene glycol diacrylate | 3D bioprinting | PEGDA-fibrinogen (145:1) scaffold encapsulating muscle progenitor cells | 0.1–1 kPa | Supports cell viability and growth | Supports myotube formation and alignment with spontaneous contraction from day 10 | 40% degradation in collagenase (0.5 mg/ml, 30 min) | [135,149] | |

| Hydrogel casting | Photo-crosslinked micropatterned PEGDA hydrogel | 33 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion, and promotes alignment | Supports myotube formation in the axis of the grooves, with myogenic genes up-regulation | X | [150] | |||

| Natural | Fibrin | Fibrous ECM protein involved in blood clotting | Electrospinning | Crosslinked fibrin fiber bundles with 0.2% PEO as carrier polymer | 17 kPa | Stem cells infiltrate the scaffold and align in the direction of the fibers | Limited success with myogenic differentiation. Absence of multinucleation. | X | [151] |

| 3D bioprinting | Fibrin hydrogel (3.5% gelatine) with encapsulated myoblasts | 15 kPa | 90% myoblast viability at day 1. Supports myoblast proliferation and alignment | Thinner constructs promote myotube formation, with enhanced myogenic expression | X | [152] | |||

| Hydrogel casting | Fibrin hydrogel, 5.6 mg/ml density in DMEM | 3.3 MPa | Supports satellite cell adhesion, activation, and proliferation | Increased myogenic gene expression and enhanced myotube formation | Complete degradation by day 5 in physiological pH | [153] | |||

| Collagen | Main structural ECM protein. Most abundant protein in mammals | Electrospinning | Calf skin derived type I collagen fibers | 38 MPa | Retains 40% of myoblasts upon seeding. Supports proliferation and cell alignment | Supports myoblast formation, displaying cross-striated pattern at 10 d. Spontaneous contraction from day 24 | X | [154] | |

| 3D bioprinting | Rat-tail collagen I scaffolds | 10–25 kPa | Supports adhesion, proliferation, and alignment of myoblasts | Formation of aligned and densely packed myotubes | X | [155] | |||

| Freeze-drying | Rat-tail collagen I freeze-dried at −60 °C with fibrillogenesis step | 33 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion and alignment | Limited success with myotube formation | 70% degradation after 9 h in collagenase solution (50 U/ml) | [156] | |||

| Bovine type I collagen freeze-dried sponges | 2.5 kPa | Smaller pore size improved initial cell adhesion, but poorer cell infiltration at the core of the sponges | Smaller pore size associated with higher levels of myogenic gene expression, supporting myotube formation. | X | [157] | ||||

| Hydrogel casting | Rat-tail collagen I hydrogel, 4 mg/ml density in PBS | 3.7 MPa | Supports satellite cell adhesion, activation, and proliferation | Increased myogenic gene expression, supports myotube formation | No weight decrease at 15 d of culture | [153] | |||

| Alginate | Naturally occurring polysaccharide found in algae. Does not provide mammalian cell adhesion ligands | Electrospinning | Alginate fibers with 2% PEO as a carrier polymer | 5 MPa | 90% cell viability at days 1 and 7, supports myoblast proliferation | Promotes myoblast elongation, alignment, and myogenic differentiation | X | [158] | |

| Hydrogel casting | Alginate gels with or without conjugated gelatine and heparin | 30–80 kPa | No MSC adhesion on alginate gels, adhesion increases with decreasing % of alginate | Increased myogenic gene expression on alginate–gelatine–heparin gels, with enhanced myotube formation | X | [159] | |||

| Natural (ECM) | Plant ECM | Plant-derived decellularized extracellular matrix | Whole decellularized tissue | White asparagus decellularized with detergent treatment | 4.9 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion and proliferation | Supports myotube formation | X | [160] |

| Apple slice decellularized with SDS treatment | 8–17 kPa | Supports adhesion, infiltration and proliferation | Differentiation not investigated. No visible spontaneous myoblast fusion after 3 weeks in culture | X | [161] | ||||

| Non-tissue specific ECM | Decellularized extracellular matrix derived from tissues other than skeletal muscle | Electrospinning | Porcine-derived urinary bladder dECM (UBM) electrospun fibers | 6.2 MPa | Supports cell growth, but with lower affinity than on tissue culture plate | Not investigated | 35% mass loss after 1 week in PBS, 37 °C | [162] | |

| Hydrogel casting | UBM hydrogel | X | Supports myoblast adhesion, proliferation, and infiltration | Not investigated | X | [162] | |||

| UBM hydrogel (8 mg/ml) | 0.11 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion and proliferation | Limited myotube formation | Fully degraded in 35 d after in vivo implantation | [57] | ||||

| Porcine dermal dECM hydrogel (8 mg/ml) | 0.45 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion and proliferation | Supports radially alignment myotube formation by day 7 | Fully degraded in 35 d after in vivo implantation | [163] | ||||

| Tissue-specific dECM | Skeletal muscle decellularized extracellular matrix | Electrospinning | Aligned dECM electrospun fibers, with GA crosslinking | 648 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion and proliferation | Promotes myotube differentiation alignment | 33% loss of scaffold volume in 10 d in cell culture media | [164] | |

| 3D bioprinting | Multilayer printed porcine skeletal muscle dECM scaffold encapsulating human skeletal muscle cells | 10–12 kPa | Over 85% viability, supports cell proliferation | Promotes myotube formation with enhanced myogenic gene expression in vitro | X | [38] | |||

| Whole decellularized tissue | Decellularized rat extensor digitorum longus | X | Supports satellite cell infiltration and proliferation | Supports myotube formation, which can be enhanced by coculture with fibroblasts | X | [24] | |||

| Hydrogel casting | Rabit muscle dECM hydrogel, thermally casted on PLLA nonwoven scaffold | 0.25 kPa | Supports myoblast adhesion and proliferation. Cell infiltration into the inner layers reported | Promotes myotube formation, with enhanced myogenic gene expression in vitro. Acceleration of muscle regeneration with increased collagen deposition in vivo. | X | [165] | |||

Scaffold composition

To have those desirable properties, SMTE scaffolds can be made from synthetic or natural polymers, including decellularized ECM [22]. Briefly, synthetic polymers possess the advantage of having highly tunable properties, allowing a precise control over their chemical, mechanical, and topological properties. Their structures are established and controlled, and characteristics such as strength, stiffness, and degradation rates are predictable and reproducible, ensuring performance reliability. Synthetic polymers are generally easier to synthesize and process, making them usually more affordable for widespread production than their natural counterparts. However, they lack intrinsic cell adhesion sites, which can lead to low cell attachment and insufficient bioactivity [26]. Bioactivity can be improved through surface coatings or surface functionalization with ECM proteins via physical adsorption or covalent binding [27]. Additionally, synthetic polymers are typically hydrophobic, potentially triggering host immune responses [28], but this limitation can often be mitigated through surface treatments [27]. Nevertheless, concerns persist about their long-term safety due to potential accumulation of their degradation products [28]. Natural polymers are typically nontoxic and highly compatible with biological systems, making them attractive for tissue engineering applications. However, their biological origin gives them an inherent immunogenicity, which can elicit host immune responses if antigenic components are not adequately removed during processing [29]. While their superior bioactivity enhances cell response, their natural origin and production methods lead to high batch-to-batch variability, processing difficulties, and higher production costs, limiting their widespread manufacturing [26]. Natural polymers usually exhibit poorer material properties, such as lower strength, reduced stiffness, and limited shelf life [3]. They also present a higher risk of pathogen contamination, raising concerns about their safety. Despite having better cell affinity than synthetic polymers, natural polymers still lack the complexity of the 3D-extracellular environment, which limits their ability to guide cells toward mature tissue states. ECM-derived scaffolds are a potential solution to address this limitation. Those can be either non-tissue specific (e.g., derived from animal or plant tissues) or tissue specific (e.g., derived from skeletal muscle), the latter offering biochemical cues tailored to the target tissue. Both types are associated with enhanced cellular function, including cell attachment, growth, and differentiation in vitro [1]. However, ECM scaffolds are challenging to manufacture, with limited control over their physiochemical properties [26] and difficulties in scaling to clinically relevant sizes. Additionally, they can trigger inflammation or rejection due to the presence of residual foreign DNA or of nonhuman cell membrane antigens [30]. A standardized decellularization method still needs to be established to ensure that the native genetic material is completely removed while preserving the mechanical and structural properties of the matrix.

Manufacturing techniques

Besides the materials used, manufacturing techniques also play an important role in scaffold design to closely imitate the native cellular environment and accurately guide cells toward tissue formation. Importantly, for SMTE, scaffolds should be porous to allow cell penetration, and they should possess an aligned structure mimicking the natural organization of skeletal muscle fibers. To achieve this, various manufacturing techniques can be used, including electrospinning, 3D bioprinting [31], hydrogel micromolding [32], and freeze-drying [11]. Details on those techniques can be found in Box 2. In the case of ECM-derived scaffolds, on top of using ECM slurry to formulate hydrogels, bioinks for 3D bioprinting, or electrospinning solutions, it is also possible to fabricate scaffolds directly by decellularizing whole tissue fragments, which could preserve the native 3D ECM structure [1]. Overall, each technique provides different levels of control over the properties of the final construct and comes with its own set of pros and cons. By carefully selecting the appropriate method and material, the design and functionality of tissue-engineered constructs can be optimized to better mimic natural skeletal muscle.

Box 2. .

Common SMTE scaffold manufacturing techniques

Electrospinning: Electrospinning is a fiber fabrication process, governed by the application of an electric force that draws charged threads of polymer solutions into nanometric fibers. Various soluble polymers and additives can be used for electrospinning either individually [33] or in blends [34]. This method enables fine control over fiber diameter, morphology, and orientation, making it interesting for creating aligned structures for SMTE scaffolds [3]. However, electrospinning only offers limited control over scaffold porosity, often leading to the formation of dense nanofiber mats that restrict cell infiltration [27]. Strategies to address this limitation include adding sacrificial fibers or microparticles, adjusting the collector’s structure to manipulate density, or introducing post-production treatments, such as ultrasonication or gas foaming, to enhance pore size and improve cell penetration [35]. Additionally, electrospun scaffolds tend to have low mechanical strength and are associated with poor load-bearing properties [36]. This limitation can be mitigated by integrating carbon nanotubes into the fibers, by further arranging the electrospun fibers into weaved, braided, or knitted structures, or by crosslinking the mesh [37].

3D bioprinting: 3D bioprinting creates functional structures by layering bioinks combining biomaterials, cells, and support molecules such as growth factors [38]. Common 3D bioprinting methods include inkjet bioprinting, laser bioprinting, and extrusion bioprinting. Inkjet bioprinting uses electromagnetic or piezoelectric force to push our drops of low viscosity bioink onto a substrate, allowing for a fast fabrication of relatively low-cost constructs. However, poor precision on the droplets’ placement limits the resolution of the printed structures. Laser-assisted bioprinting achieves high micrometric precision by vaporizing and propelling bioink with a laser pulse, but this method is associated with long printing times and high operation costs. Finally, extrusion bioprinting employs a mechanical or pneumatic force to expel bioink through a nozzle, producing constructs with high structural integrity and high cell density. A major drawback of this technique is the low cell viability associated, with survival rates as low as 40% [39]. To limit shear stress, prevent cell damage, and thus increase cell survival rates, strategies such as using lower-viscosity or non-Newtonian shear-thinning bioinks, modifying nozzle geometry and size [40], and regulating nozzle and printing chamber temperature can be implemented [41].

Hydrogel micromolding: Also known as soft lithography, hydrogel micromolding uses patterned molds to shape hydrogel precursors, which are then cross-linked to retain the mold’s shape [42]. Crosslinking methods include ultraviolet and thermal polymerization. Soft lithography offers high-resolution patterning, enabling the creation of detailed structures. Those microscale topographic cues, often grooves or ridges with optimized dimensions, guide the adhesion, alignment, and differentiation of muscle cells [32]. Unlike photolithography, which directly patterns hydrogel constructs using light beams, soft lithography only requires the master mold to be patterned. Because of this, soft lithography eliminates the systematic need for a clean-room environment, significatively reducing costs of production [27]. While these hydrogels typically exhibit poor mechanical strength and limited resistance to dynamic forces, they can be integrated with stiffer frameworks, such 3D-printed or electrospun structures, enhancing their mechanical properties [32].

Freeze-drying: Freeze-drying is a promising technique for fabricating highly porous SMTE scaffolds. It is a dehydration process using ice as a porogen, which involves freezing water-soluble polymer constructs and sublimating ice crystals to create interconnected pores. This technique uses water as a solvent, reducing cytotoxicity risks compared to methods using harsher solvents [11]. Additionally, the resulting high porosity and interconnectivity promotes cell migration and infiltration into the constructs, as well as sufficient nutrient diffusion. Although porosity can be influenced by freezing-rate adjustments, freeze-dried scaffolds often remain heterogeneous, with pore sizes inferior to what is needed for proper cell integration [43].

Cell types

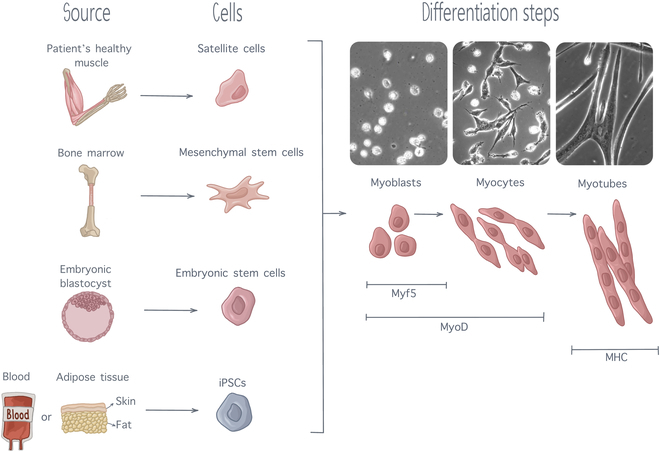

In SMTE, immature cells are supported and guided by scaffolds and external physicochemical cues to undergo myogenic differentiation and form mature, healthy, and contractile muscle tissue. Myogenesis can be broken down in a sequence of steps. Precursor cells differentiate into myoblasts, which start fusing and forming myocytes, which then further fuse and organize themselves into myotubes (Fig. 2) [2]. As they progress down the myogenic differentiation cascade, cells express specific transcription factors, which are distinctive attributes of the current cell state [44]. Put simply, following activation and entry into the cell cycle, precursor cells will start expressing myogenic factor 5 (Myf5), confirming their commitment toward the myogenic lineage. Alongside with Myf5, myoblasts will express a protein called myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD), which marks myoblast commitment. As myoblasts proliferate and start fusing, Myf5 expression will decrease while MyoD expression will surge. When fully fusing into myofibers, MyoD expression will be replaced by myosin heavy chain protein (MHC) expression, which is considered as a marker of late-stage myoblast differentiation [2,6]. Thus, quantifying those transcription factors is usually done to characterize the progression of myogenic differentiation.

Fig. 2.

Myogenesis steps, from precursors cells of various sources to fully differentiated myotubes. As differentiation progresses, muscle cells express several transcription factors, including Myf5, MyoD, and MHC expressing subsequent level of maturation. Cell pictures are adapted from [137] with permission from Development.

Precursor cell types for SMTE must possess a high proliferative capacity while being able to efficiently differentiate into myotubes [27]. Multiple cell types can be used for clinical applications, including satellite cells, which are stem cells derived directly from the patient’s healthy muscle. Satellite cells are direct precursors of skeletal muscle. They are naturally used for muscle regeneration by the organism and are thus particularly appropriate for SMTE [45]. However, their extraction process is highly invasive, limiting their application to SMTE. Therefore, interest for other types of stem cells with an ability for myogenesis has increased. Stem cell lineages of interest include mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [44,46]. MSCs, also known as mesenchymal stromal cells, are multipotent cells with an ability to differentiation into diverse cell types, including cartilage cells, fat cells, bone cells, and muscle cells. They are mainly extracted from the bone marrow (through femur or tibia bone marrow biopsies) or from adipose tissue. Adipose tissue-derived MSCs are easier to obtain, with only limited patient discomfort, and can be expanded in large quantities in vitro; thus, most of the research conducted on MSCs is currently focused on adipose tissue-derived MSCs [45]. Although MSCs can differentiate into muscle cells, their ability for myogenicity is quite limited. It had been established that, in differentiation medium, only 15% of MSCS could differentiate into myocytes [44]. Although this differentiation ability can be enhanced using an appropriate scaffold and external stimulation, this low myogenic ability limits the use of MSCs for SMTE. ESCs are found in the inner cell mass at the early stage of human embryonic development, from the 4th to the 7th day after fertilization [47]. They possess the capacity to differentiate into all cell types existing in the human body and are thus referred to as pluripotent. Although their pluripotency makes them exciting candidates for tissue regeneration, the ethical concerns linked to their embryonic origin strongly limit their usage in research. In recent years, iPSCs have emerged as a promising alternative to overcome the limitation associated with the use of ESCs. These pluripotent cells can be derived from almost every adult tissue, share morphological similarities with ESCs, and possess the ability to proliferate indefinitely [44]. The discovery of the process to convert mature cells back into pluripotent stem cells owed Dr. Shinya Yamanaka and Sir John Gurdon the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine [48], as iPSCs are extremely promising for regenerative medicine. More precisely for the field of SMTE, it has been shown that iPSCs can generate multinucleated myotubes in 2D culture, while 3D culture into hydrogels allowed iPSCs to differentiate into contractile skeletal muscle tissue constructs [44]. Despite these favorable results, several ethical and safety concerns remain to be addressed surrounding the potential clinical use of iPSCs. A major concern is their tumorigenic potential, which can arise through malignant transformation of differentiated iPSCs or benign teratoma formation from residual partially differentiated cells [49], caused by oncogenes used during the reprogramming process [50]. Additionally, immature iPSCs tend to exhibit deficient DNA damage repair and impaired cell cycle arrest, making them more prone to accumulating genomic abnormalities [51]. A large-scale study, conducted by the International Stem Cell Initiative across 38 laboratories, compared 11 iPSC lines at early and late passages and found that more than 20% displayed increased activity of anti-apoptotic genes after extended in vitro culture [52]. This finding underscores the risk that prolonged iPSC culture may lead to genomic instabilities, further exacerbating their tumorigenic potential. To mitigate these risks, alternative reprogramming factors are being researched as well as protocols to minimize residual undifferentiated cells and targeted elimination of aberrant cells using drug-induced cell suicide [51]. Besides, immunogenicity of iPSCs remains a concern as studies suggest that iPSC-derived cells may elicit immune responses despite being autologous [53]. Traditional immunosuppressive therapies, commonly used to enhance graft tolerance, would be unsuitable for iPSC-based treatments, as suppressing the immune system to prevent rejection could inadvertently further heighten the risk of tumor formation [50]. Given iPSCs’ tumorigenicity, this dual risk presents a challenge for their safe clinical application. Therefore, continuous efforts must be made to accurately detect genetic instabilities and insure homogeneity of cell populations.

For these reasons, stem cell-derived products require strict quality control measures dictated by a strong regulatory framework at all stages of development [50]. At this stage, out of these potential cell sources for SMTE application, none have currently been approved by regulatory bodies for patient usage. Currently, the only stem cells approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are hematopoietic progenitor cells, which are blood-forming stem cells that are derived from umbilical cord blood [54]. These stem cells possess a limited ability to support myogenic differentiation when cocultured with myoblast; thus, their interest for SMTE is strongly limited [55]. Additionally, while they have obtained approval for the treatment of blood pathologies, their usage for other purposes remains unauthorized.

While clinical applications require human precursor cells, in current SMTE research, most studies limit themselves to using already partially differentiated muscle cells. One step further down in their commitment toward myogenic phenotype, myoblasts are more affordable, with high proliferation capacity and robustness, and they differentiate easily into myotubes. Consequently, the immortalized mouse myoblast C2C12 cell line is widely used to test scaffolds and stimuli for myotube formation. However, for translation to clinical use, all the research conducted with C2C12 will have to be confirmed with human cell lines. For other applications of SMTE, such a biorobotics or cell-cultured meat production, this translation to human cell lines is not necessarily needed. In this regard, less work remains to be conducted for potential application of SMTE to those fields.

When differentiating into myofibers in vivo, myoblasts receive crucial information from their cellular environment. Information can be delivered by the ECM they are in contact with, by the dynamic mechanical cues of their 3D environment, and by other cells present in their vicinity. A few cell types naturally found in skeletal muscle tissue are known to influence its growth and regeneration, and researchers have been investigating their potential for guiding myoblast differentiation in in vitro cocultures. For instance, macrophages and fibroblast are known to invade the injury site during the muscle repair process. Thus, Venter and Niesler [56] investigated the behavior of myoblasts in in vitro cocultures with those cells. They reported that both macrophages and fibroblasts could significatively promote myoblast proliferation and proliferation. Other important cells when attempting to recreate the native myoblast cellular environment are motor neurons. Motor neurons provide myofibers with the electrical stimulation required to initiate contraction. In vitro 3D cocultures of myoblasts with neural stem cells have been shown to result in the formation of NMJs by Morimoto et al. [57], and the NMJs formed where subsequently used to stimulate the myoblasts to guide their differentiation toward myofibers. While only partially mature myofibers were obtained, contraction of the neuro-muscle constructs was still observed under stimulation. The constructs produced could therefore be attractive candidates for soft robotic bioactuators. Vascular cells, such as epithelial cells, also play an important role in skeletal muscle tissue formation. Indeed, a highly integrated vascular system is key to ensure that the high metabolic demand of skeletal muscle tissue is met. Endothelial cells and muscle progenitor cells share a deeper connection than just their spatial vicinity: They have been shown to mutually promote and regulate one another’s proliferation, migration, and differentiation [58]. However, in vitro cocultures of endothelial cells and myoblasts remain technically challenging, as they both require different growth media composition. While cocultures allow to better encompass and reproduce the complexity of the in vivo myoblast environment, giving promising results in terms of promoting and regulating proliferation and migration, they are also more technically complex to establish and maintain in vitro [6]. Therefore, direct chemical stimulation of engineered skeletal muscle constructs is also being researched. While this would not fully replicate the native myoblast environment, it could still positively impact myoblast development, differentiation, and growth. Details on this approach is given in the next section.

External stimuli

Mechanical stimulation

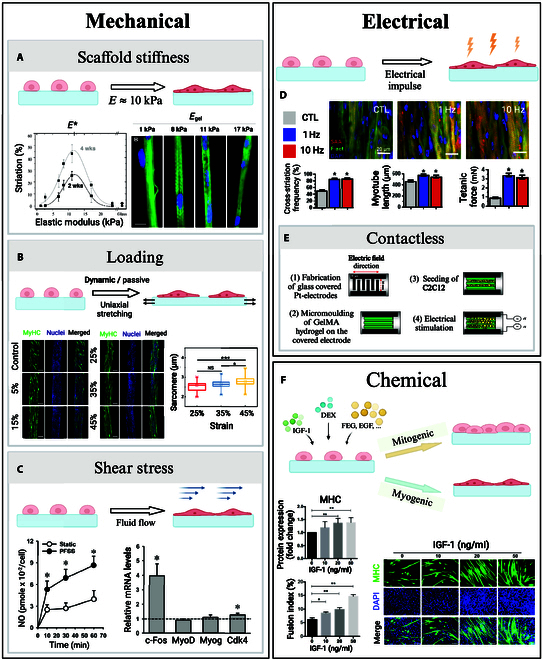

Most cells, including those of the musculoskeletal system, are mechanoresponsive [59,60]. While the exact cellular processes involved in mechanotransduction remain to be elucidated, it is known that external mechanical signaling is registered by cells through focal adhesions and a variety of other mechanosensitive structures such as cytoskeleton filaments, mechanically activated ion channels, and myosin motors [61]. These mechanical cues induce cytoskeletal reorganization, driving morphological and metabolic changes [6], muscle growth, protein synthesis, satellite cell activation, and growth factor release. Remarkably, cell differentiation pathways are affected by surface stiffness [62] as focal adhesions allow cells to sense the elasticity of the substrate they are attached to [61]. Engler et al. [63] observed that, when cultured on polyacrylamide gels matching the stiffness of brain tissue (0.1 to 1 kPa), muscle tissue (8 to 17 kPa), and collagenous bone tissue (25 to 40 kPa), MSCs displayed morphological changes and up-regulation of biomarkers associated respectively with neurogenic, myogenic, and osteogenic phenotypes. In the same manner, scaffold stiffness plays an important role in myoblast differentiation toward mature myotubes. Myoblasts cultured on collagen-coated polyacrylamide gels of varied stiffness showed different levels of striation, with well-organized sarcomeres on substrates of intermediate stiffness (8 to 11 kPa) (Fig. 3A). While softer and stiffer substrates (including glass controls) also supported myoblast fusion into multi-nucleated myotubes, only gels possessing a muscle-like stiffness showed advanced levels of myosin striation even at 4 weeks in culture [64]. Typically, higher levels of sarcomere organization are associated with a higher degree of myotube maturation and a higher force production potential. Those findings point toward the existence of an optimal scaffold stiffness to promote maturation of myotube, which would be around 10 kPa, i.e., the stiffness of native skeletal muscle [5]. However, other data suggest that the range of acceptable scaffold mechanical stiffness necessary to promote myotube formation might be wider. Levy-Mishali et al. [61] reported that higher substrate stiffness in the range of 200 to 250 kPa was associated with higher myoblast viability and increased number of myotube formation at 7 d. Those stiffer substrates also resulted in the formation of larger cellular bodies, and they supported higher rates of myotube alignment than the softer gels (4 to 60 kPa). Thus, while scaffold stiffness has been proven to impact myotube viability, morphology, alignment, and sarcomere arrangement, the ideal mechanical properties required to engineer mature functional skeletal muscle still need to be determined.

Fig. 3.

External stimuli in SMTE. (A) Two weeks after seeding myoblasts on collagen-coated substrates, Engler et al. [64] stained for myosin (green) and nuclei (blue). Gels of intermediate stiffness showed notable actin–myosin striation, with an optimal reached for E = 12 kPa (scale bar: 20 μm). (B) Morphology of C2C12 cells after stimulation, investigated by Chen et al. [65] Sarcomere lengths increased with the strain ratios (scale bars: 200 μm). (C) Pulsative fluid shear stress doubled nitric oxide production and up-regulated proliferation marker expression in muscle stem cells, presented by Haroon et al. [67]. (D) Khodabukus et al. [68] studied the effects of electrical stimulation on myotube structure. Myobundles stained for α-actinin (red), filamentous actin (green), and nuclei (blue) showed an increase in striation, myotube length, and tetanic force for stimulated constructs. (E) Ahadian et al. [70] presented a contactless electrical stimulator for SMTE. The pH of the culture media remained stable over the time of culture when compared to traditional electrical stimulators, and expression of myogenic factors increased under a 10 V–1 Hz stimulation. (F) Supplementing myoblasts with IGF-1 resulted in enhanced MHC expression and higher fusion indexes after 5 d of culture, presented by Guan et al. [73] (scale bar: 100 μm). Permissions granted where necessary.

Besides passive stiffness, skeletal muscle cells also respond to active mechanical stimulation [7]. For instance, Chen et al. [65] reported that, under uniaxial stretching, myoblasts encapsulated in fiber-shaped gelatine methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogel cellular constructs showed higher degrees of cell spreading, elongation, and alignment as well as more pronounced myofiber contractibility (Fig. 3B). A contractibility saturation level was reached for a strain ratio of 35%, which points toward the existence of an optimal stretching degree to favor functional mature myofiber formation. This optimal strain ratio appears consistent with the range of deformation undergone by native skeletal muscle during in vivo contraction (up 40%) [5].

In addition to sensing mechanical loading, skeletal muscle cells also respond to shear stress. Traditional cell culture systems, such as plates or flasks, are static. They only allow for limited gas and nutrient exchange, often causing engineered skeletal muscle tissue to become necrotic at its core. To overcome this limitation, bioreactors with continuous flow of media have been developed. This new generation of culture reactors allow for a more physiological delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the cells, resulting in higher cell survival rates, while also promoting the up-regulation of cell proliferation markers through shear stress-induced cellular mechanisms [66]. Haroon et al. [67] reported that pulsative fluid shear stress loading of muscle stem cells in vitro up-regulated the expression of several genes, including c-Fos and Cdk4, which are known to promote cell proliferation (Fig. 3C). Shear stress also induced higher levels of nitric oxide production, which is associated with enhanced muscle stem cell (MuSC) self-renewal during skeletal muscle regeneration.

Electrical stimulation

Sustained contractile activation of skeletal muscle is vital to maintain striated muscle cell viability and function [59]. Electrical stimuli, delivery in vivo by motor neurons, regulates muscle tonus and prevents muscle atrophy [59,68]. In vitro, electrical stimulation has been shown to enhance myogenic differentiation and maturation of engineered striated muscles [69]. Khodabukus et al. [68] studied the effect of intermittent electrical stimulation (1-h stimulation at either 1 or 10 Hz, separated by 7-h rest periods) on the differentiation and maturation of human myobundles (Fig. 3D). They reported that, after 1 week of stimulation, myobundles exhibited an increased number of nuclei, associated with an augmentation of myotube cross-section and length. Cell staining also revealed higher degree of striation, corresponding to more highly organized sarcomeres in stimulated muscle constructs. Increased glucose consumption and higher lactate production indicated a higher cellular metabolic rate, which was associated with a 3-fold increase in tetanic and twitch force output in stimulated myobundles.

While it has been established that electrical stimulation leads to higher degrees of engineered muscle maturation and functionality, currently employed electrical stimulation devices use electrodes that are in direct contact with the muscle constructs or the culture medium in which they are immerged. This contact may cause detrimental effects on the engineered constructs, including hydrolysis of the culture medium, therefore causing bubble formation, pH increases, and temperature elevation of the medium through joule heating. Contamination of the tissue culture environment by the products of electrode corrosion is also made more likely [70]. To overcome those limitations, Ahadian et al. [70] developed a contactless electrical stimulator successfully delivering electrical stimulation to engineered skeletal muscle constructs using glass-covered platinum electrodes (Fig. 3E). They reported that this contactless device allowed to maintain a stable pH of the culture media for up to 6 h of continuous stimulation while also preventing the formation of bubbles. When applying their device to deliver electrical stimulation to muscle myofibers, up-regulated levels of myogenic genes expression were measured, demonstrating higher myotube maturation and contractile abilities.

Biochemical stimulation

When progenitor muscle cells terminally differentiate into myotubes in vivo, they receive critical biochemical stimulation from their environment guiding them toward myogenesis. Macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and even other myoblasts deliver both structural cues, through cell–cell contact, and chemical cues through the release of growth factors and other chemical stimulants. Inspired by those natural processes, chemical stimulation by delivery of chemical agents to increase proliferation and maturation of engineered skeletal muscle construct is being researched [6]. A variety of growth factors are involved in skeletal muscle tissue development. Most growth factors have a mitogenic impact on muscle precursor cells, which means that they promote cellular division by forcing the cells to reenter the cell cycle [71]. By doing so, they actively block cellular differentiation and are thus boosting cell proliferation but preventing tissue maturation. Such growth factors, for example, include epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [6,71]. Notably, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) has been found to have both a mitogenic and a myogenic effect on myoblast. IGF-1 thus promotes both myoblast proliferation and terminal differentiation, setting it apart from other mitogenic growth factors. At the organism level, IGF-1 has been shown to be essential to muscle growth development [72]. Experiments conducted on mice embryo established that the knocking out of IGF-1 gene results in the birth of nonviable pups [71]. At the cellular level, Guan et al. [73] reported that supplementing myoblasts with IGF-1 resulted in enhanced cellular proliferation, with significatively higher mitochondrial DNA quantities measured, and higher degrees of differentiation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3F). The increase in myoblast fusion index was paired with an up-regulated expression of myogenic factors. Other kinds of chemicals have also been investigated as potential stimulant for the development of engineered skeletal muscle constructs. Remarkably, the glucocorticoid dexamethasone (DEX) has been shown to stimulate myoblast differentiation into myotubes. Syverud et al. [74] reported that muscle satellite cell supplementation with DEX exhibited higher rates of myogenic proliferation. Addition of DEX was associated with the formation of denser myotubes with larger cellular bodies.

Additional stimulation methods to promote skeletal muscle tissue formation

While mechanical, electrical, and biochemical stimulation remain the most widely used methods for promoting tissue formation and regeneration, other techniques have also shown potential. Notably, magnetic stimulation has emerged as a promising tool for enhancing muscle repair in SMTE approaches [6]. Although still in its early stages, it shows potential across several dimensions. First, magnetic stimulation has been shown to promote muscle regeneration following injury. For instance, using a murine muscle injury model, Stölting et al. [75] reported that external magnetic stimulation significantly reduced inflammatory infiltration and scar formation, prevented post-traumatic muscle atrophy, and promoted hypertrophy. Moreover, it enhanced muscle metabolism and turnover, tripled the expression of muscle-specific markers, and improved functional recovery. The authors concluded that magnetic stimulation supported both muscle and nerve regeneration by enhancing muscle-nerve cross-talk and promoting the maturation of NMJs. Second, magnetic fields can be used to guide and manipulate the 3D organization of engineered tissues. This is particularly advantageous for promoting muscle cell alignment, which is critical to achieve high functionality of the engineered muscle. Yamamoto et al. [76] demonstrated that magnetically labeled C2C12 myoblasts could be aligned around hollow fibers using external magnetic fields. This setup enabled the formation of dense, multilayered muscle constructs, highlighting the utility of magnetic stimulation through cell labeling to form large-scale skeletal muscle constructs [77]. Beyond in vitro applications, magnetically labeled cells also hold promise for direct in vivo tissue engineering approaches. Studies have shown that such cells could be injected and subsequently guided to injury sites using external magnetic fields, facilitating targeted regeneration of musculoskeletal tissues such as bone, cartilage, and skeletal muscle, in a minimally invasive manner [78]. For instance, Nakabayashi et al. [79] delivered magnetically labeled MSCs into a rat model of muscle injury and observed enhanced cell proliferation within 72 h under magnetic targeting. Histological and biomechanical analyses confirmed improved repair outcomes in the treated muscles. Collectively, these findings highlight the versatility and therapeutic potential of magnetic stimulation as a noninvasive strategy in skeletal muscle regeneration and tissue engineering.

Finally, as the different types of stimulation reviewed here have shown great promise for tissue engineering of skeletal muscle constructs, ways of combining those stimulation methods together to further promote muscle growth are now being investigated [6]. For instance, Liao et al. [80] have reported that a combined electromechanical stimulation (5% cyclic strain at 1 Hz from 2 d post-differentiation with 20 V at 1 Hz from 7 d post-differentiation) induced significant increase in myogenic factor expression in myoblasts. Synchronized dual stimulation resulted in the formation of myotubes with a higher degree of striation. In brief, while the results reported in the literature are promising, additional work needs to be conducted to establish optimal stimulation settings for all parameters, and progress also needs to be made to efficiently deliver the combined stimuli to the construct for optimal engineered skeletal muscle tissue maturation and functionality.

Bioreactor systems

To deliver the different stimuli mentioned above, researchers have been focusing on the development of bioreactor systems. Bioreactors play a crucial role in tissue engineering as they provide a controlled environment supporting the metabolic needs of tissue constructs [81]. To properly support tissue constructs of any kind, a bioreactor must possess some key fundamental characteristics. It needs to be easy to sterilize and able to maintain sterility over the duration of tissue culture. All the materials used for the bioreactor must be cytocompatible, and their corrosion when in contact with tissue culture medium must be minimal. It should provide appropriate biochemical conditions, which include gases and nutrient concentrations, pH, and temperature, and allow for control of the operating conditions over time [59]. Additionally, a bioreactor should enable to monitor the culture conditions, either through built-in captors or through visual input [82]. As bioreactors should aim to mimic the native cellular environment, bioreactors for SMTE must ideally also enable the delivery of mechanical or electrical stimulation to the muscle constructs [83]. As skeletal muscles exist in high stress environments and possess considerable metabolic needs, bioreactor design for SMTE is particularly challenging.

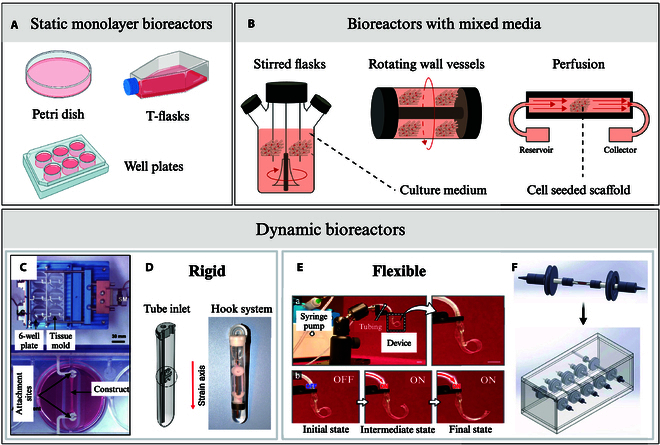

Over the years, many bioreactor systems have been developed for engineering skeletal muscle, with various degrees of complexity (Fig. 4). The simplest bioreactor systems are static monolayer culture bioreactors, which include T-flasks, multi-well plates, and petri dishes. They are economical, simple to use, and easy to sterilize, but they require manual handling for medium exchange. Their major limitation is that they can only support tissue with a limited thickness (around 100 μm) due to insufficient gas exchange via surface aeration and limited diffusion-driven nutrient transfer [59,84], leading to nonuniform tissue formation with preferential cell growth around scaffold edges [85]. To improve mass transfer and allow the culture of thicker tissue constructs, a range of bioreactor systems with continuously mixed media have been developed [59]. Stirred flasks, where cell-seeded scaffolds are suspended in stirred culture medium, are an accessible and relatively simple example of such dynamic bioreactor systems [86]. Turbulent mixing is facilitated by a magnetic stir bar at the bottom of the flask, generating convective forces that enhance nutrient distribution, while temperature and oxygen levels are regulated by an incubator in which the whole setup is placed [85]. While this method allows for higher cell seeding density, more uniform cell distribution compared to static models [85], and improved overall cell viability [59], the stirring setup creates an uneven shear stress distribution leading to nonhomogeneous culture conditions. This can lead to the formation of a dense superficial cell layer, limiting nutrient diffusion to the tissue core [86]. Offering more stable fluid flow than stirred flasks, rotating wall vessel bioreactors, developed by NASA in the 1990s [87], freely suspend scaffolds in media between 2 concentrical cylinders. The outer cylinder rotates, while the inner cylinder of a rotating wall vessel remains stationary, creating a microgravity-like environment that promotes media mixing with a laminar fluid flow [85]. This reduced shear stress while minimizing diffusional limitations of nutrients and waste, therefore supporting higher cell proliferation with lower apoptosis compared to static cultures. However, frequent scaffold collisions with the bioreactor wall may cause cell injury, disrupting attachment and matrix deposition [86]. Finally, perfusion bioreactor systems offer superior mass transfer by continuously circulating media through scaffold pores, promoting homogeneous cell distribution with high seeding efficiencies [85]. The resulting shear forces mechanically stimulates cells, benefiting skeletal muscle tissue formation [66]. However, excessive shear stress can lead to cell washout and can hinder ECM deposition and result in poor cytoskeletal organization [86]. Additionally, the removal of perfusion conditions upon in vivo implantation risks causing rapid tissue necrosis, posing challenges for clinical translation of constructs produced this way [59].

Fig. 4.

Examples of SMTE bioreactors. (A) Static monolayer culture bioreactors: petri dishes, tissue culture flasks (T-flasks), and well plates. (B) Bioreactors with mixed media: stirred flasks, rotating wall vessels, perfusion [138]. Rigid bioreactors: (C) mechanical cell stimulator (modified 6-well plate) by Powell et al. [139] and (D) the MagneTissue bioreactor (custom tube-inlet fitted into a modified falcon tube) by Heher et al. [140]. Flexible bioreactors: (E) pneumatic soft robotic in vitro platform for cell culture by Paek et al. [110] and (F) perfused flexible tubing lines hosting one bioconstruct each, fitted into a Plexiglas chamber, by Quarta et al. [141]. Permissions granted where necessary.

Both the static and dynamic systems mentioned above are built with hard and rigid chambers, often using modified cell culture well plates as the base component. While they are relatively easy to build and operate, rigid bioreactors display very limited performances when it comes to delivering mechanical stimuli as they are usually limited to uniaxial stretching [88]. For skeletal muscle, where mechanical stimulation plays such an important role in tissue maturation, this could limit the functionality of the constructs produced. To overcome this limitation and deliver physiologically relevant multiaxial stresses to the constructs, soft flexible bioreactors have been developed in recent years. Table 2 recapitulates rigid and flexible SMTE bioreactors developed along with their key characteristics. Unlike rigid traditional bioreactors, those new systems are equipped with soft flexible chambers that can undergo a wider variety of multiaxial deformation such as twisting, bending, stretching, and compression [88]. Materials suggested to construct soft chambers allowing this versatility in movement tend to be more permeable to oxygen than materials traditionally used in hard rigid bioreactors. Thus, soft chambers passively improve gas exchange, ensuring a more adequate delivery of oxygen to the engineered skeletal muscle constructs. However, soft materials can rupture more easily, which makes leak proofness and sterility harder to maintain, especially under load-bearing conditions [88]. Additionally, to accurately monitor the mechanical and biochemical conditions in soft bioreactors, flexible integrated sensors must be developed, adding another level of complexity to bioreactor design [89]. While soft chambers are facing those technical challenges and thus remain an emerging area, progress is steadily being made, with increasing efforts and innovations pointing toward their transformative potential. The growing interest in soft, flexible bioreactors is particularly encouraging for SMTE, as such systems not only address the challenges outlined above but also offer an exciting opportunity to bridge tissue engineering with the advancing field of biorobotics.

Table 2.

Current bioreactor systems for SMTE. The presence of an * indicates that the mechanical stimulation is due to shear stress produced by the presence of a liquid flux.

| Reactor type | Description | Stimulation | Cell line | Date | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Electrical | Magnetic | |||||

| Rigid | Perfused commercially available “CellCo” culture system | + * | - | - | Embryonic avian muscle cells | 1998 | [166] |

| Rigid | Covered glass spinner flasks | + * | - | - | C2C12 myoblast | 2001 | [167] |

| Rigid | Modified 6-well plate | + | - | - | Primary human skeletal muscle cells | 2002 | [139] |

| Rigid | Rectangular Plexiglas culture chamber | + | + | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2007 | [82] |

| Rigid | Modified tissue culture container | + | - | - | Human muscle precursor cells | 2008 | [168] |

| Rigid | Scaffold wrapped around silicon tubing into rigid container | + | + | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2009 | [80] |

| Rigid | Polycarbonate chambers perfused with laminar flow | + * | - | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2009 | [169] |

| Rigid | Modified 6-well plate | - | + | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2010 | [170] |

| Rigid | Plexiglas culture chamber | + | - | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2010 | [171] |

| Rigid | Polycarbonate hollow fibers | - | - | + | C2C12 myoblasts | 2012 | [76] |

| Rigid | Silicon chambers into modified 5-well plates | + | - | - | Murine muscle-derived cells | 2012 | [172] |

| Rigid | Fibrin ring scaffolds in modified falcon tubes | + | - | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2015 | [140] |

| Rigid | Perfusion seeding bioreactor with 2 glass columns | - | + | - | Primary mouse myoblasts | 2015 | [173] |

| Rigid | Actuation chamber hosting a modified well plate | + | + | - | Human adipose-derived stem cells | 2016 | [97] |

| Rigid/flexible | Rigid reactor bow containing 4 flexible chambers | + * | - | - | Human muscle stem cells | 2017 | [141] |

| Rigid | 3D-printed perfused chamber | + * | - | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2019 | [174] |

| Rigid | Hydraulic chamber with PDMS membrane | + | - | - | None | 2021 | [175] |

| Flexible | Curling pneumatic device with integrated culture chamber | + | - | - | Human uterine muscle cells | 2021 | [110] |

| Rigid | Sterile culture compartment clamped onto an actuator | + | - | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2021 | [110] |

| Rigid | Metallic chamber equipped with a mobile grip system | + | - | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2022 | [176] |

| Flexible | Silicon chamber with 2 metallic frames in an incubator | + | - | - | C2C12 myoblasts | 2024 | [177] |

Alternatives to conventional SMTE

The conventional SMTE approaches discussed earlier rely on a combination of scaffolds, cells, and bioreactors to generate functional muscle tissue. To simplify this complex process, alternatives have emerged to bypass one of these key elements, leading to scaffold-free, cell-free, and in vivo engineering methods, each offering distinct advantages and challenges. Additionally, advancements in microfluidic technologies, such as organoids and organ-on-chip systems, provide innovative platforms for studying muscle physiology and disease. This section briefly explores these alternative approaches, highlighting their potential applications and limitations in advancing skeletal muscle regeneration.

Scaffold-free, cell-free, and stimulation-free approaches

Scaffold-free approaches in SMTE eliminate the need for an external 3D matrix, relying instead on direct cell delivery [90]. For SMTE, one of the most common methods involves the direct intramuscular injection of cells to the damaged area [7]. While this technique is straightforward and has shown some promising preliminary results [91], it faces considerable challenges such as poor cell retention, low survival rates, and immune rejection of the transplanted cells [7]. To improve retention, alternative scaffold-free strategies have been explored, including through the formation of cell sheets or cell aggregates. The coculture of satellite cells and fibroblasts that self-assemble into cylindrical muscle constructs that can later be implanted is a promising approach for SMTE [92]. However, while they offer better structural integration, such approaches are constrained by the time required for the formation of ECM structures robust enough for integration—often over 4 weeks—and the limited construct size due to nutrient diffusion constraints [92].

In contrast, cell-free approaches, also known as in situ tissue engineering, leverage acellular biomaterial scaffolds to induce endogenous regeneration. By engineering precise biophysical and biochemical cues, these scaffolds can guide host cell recruitment, activation, proliferation, and differentiation [7]. This method offers several advantages, including faster and simpler fabrication, streamlined delivery, and off-the-shelf availability due to the elimination of cell culture requirements [14]. Additionally, regulatory barriers are often lower, accelerating clinical translation [7]. However, a key challenge lies in ensuring uniform cell infiltration throughout the scaffold, particularly at its core, which is critical for achieving consistent and controlled tissue regeneration.

A further alternative to conventional tissue engineering is in vivo tissue engineering, which can be seen as a “stimulation-free approach”. It involves seeding scaffolds with cells immediately before transplantation to minimize cell manipulation, thus preserving cell functionality and simplifying the preparation process [7]. However, transplanted cells remain vulnerable to low viability, retention issues, and immune rejection within the host environment and the success of this method depends on scaffold properties and implantation conditions to enhance cell survival and integration [7].

Organoids and organ-on-chips

Organoids and organ-on-chips (OoCs) represent an extension of conventional tissue engineering, integrating microfluidics to create highly controlled microenvironments that better replicate physiological conditions. These systems operate at the microscale, with dimensions typically confined to around 100 μm to ensure appropriate flow dynamics [93]. While both organoids-on-chips and organs-on-chips merge tissue engineering with microfluidics, their concepts and focuses differ slightly. Organoids-on-chips rely on the self-organization of stem cells to form 3D tissue clusters, which are then cultured on microfluidic chips to support long-term maintenance. In contrast, organs-on-chips do not rely on self-organization; instead, they are fully microengineered platforms incorporating microfluidic channels designed to replicate tissue interfaces and physiological forces present in living tissue. Applied to SMTE, OoCs provide advanced platforms for studying muscle physiology and pathology by closely mimicking the structural organization, functional properties, and regenerative capacity of native skeletal muscle [94]. Consequently, their primary applications lie in drug discovery and disease modeling, where they serve as powerful tools for high-throughput testing with minimal reagent and compound use [93,95]. Additionally, these platforms possess interesting potential in the field of robotics, particularly in the development of microbiorobots. Specifically, they can be employed as testing grounds for microdrug delivery robots [96]. Although the scope of biorobotics discussed in this review excludes a detailed exploration of this application, OoCs remain highly promising technologies that continue to push the boundaries of biomedical research. For a more in-depth analysis, we refer interested readers to previously published reviews [93,94,97].

Challenges in clinical translation of SMTE strategies

Up to this point, this review has primarily examined the individual building blocks of engineered skeletal muscle, including scaffolds, cells, and growth environment, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations. However, as SMTE is ultimately driven by the clinical need to repair large muscle defects, the successful integration of these components into a cohesive and functional tissue is essential. This includes ensuring appropriate donor–host integration and long-term survival of the engineered muscle [98]. At this higher level of abstraction, new challenges emerge, which are not tied to any single component but rather arise from the complex interplay between them. Therefore, these challenges often cannot be resolved by modifying building blocks independently but instead require more complex strategies that account for the full system and its host environment. As a result, many of these issues remain unresolved and continue to represent major barriers to clinical translation.

One of these central challenges toward functional clinical translation is the vascularization of engineered constructs. Skeletal muscle has colossal metabolic needs, requiring an abundant supply of nutrients and oxygen to function and survive [2]. Without vascular networks, construct size is severely limited by diffusion constraints, risking necrosis in central regions and rendering such constructs inherently unsuitable for large defect repair. In vitro strategies to achieve vascularization include coculturing muscle cells with endothelial cells, optimizing scaffold properties, such as incorporating hollow channels, and supplementing with angiogenic factors [99]. While these approaches show promise, work remains to fully achieve vascularization and overcome the size limitations of constructs. Even when viable vascular networks are achieved in vitro, rapid integration with the host’s circulation post-transplantation is necessary to prevent hypoxia-induced cell dead. This remains a major translational challenge [98]. Another major hurdle is innervation, and more specifically, the rapid integration of the engineered muscle with the host’s neuromuscular system. Without timely innervation, grafts will remain nonfunctional in the short term and will risk atrophy over time [98]. Lastly, immune rejection of constructs also threatens host integration. The recipient’s immune system may identify the engineered tissue as foreign and attack it. Using nonimmunogenic scaffolds and autologous cells can mitigate this risk [100], but this approach comes with its own set of drawbacks. Cell harvesting procedures can be invasive, and the regenerative potential of harvested cells often declines during extended in vitro culture [101]. In addition, prolonged graft growth time may allow the injury site to begin healing, allowing scar tissue formation, which would further complicate functional integration [102].

Regulatory hurdles must also be addressed to enable the clinical translation of SMTE approaches. The standardization of engineered constructs and of procedural guidelines remains an obstacle. Universal standards remain to be established, complexified by the interdisciplinarity of the field. Additionally, the financial cost of bringing SMTE therapies to market is a considerable burden. While exact costs are uncertain, pharmaceutical companies typically spend over $850 million to develop and commercialize new products [103]. Given the complexity of SMTE—encompassing multiple components such as cells, scaffolds, bioreactors, and growth factors, all of which may require individualized production methods—the associated costs are expected to be even higher. Despite these challenges, the tissue engineering market is projected to grow by about 10% over the next decade [104], reflecting ongoing advancements and continuous interest. While SMTE primarily aims at repairing large muscle defects, other promising applications like drug discovery, disease modeling, cell-cultured meat, and biorobotics may reach practical use sooner, sustaining enthusiasm for the field.

Advanced Robotics and Muscle Tissue Engineering

Advanced robotics applied to SMTE

In musculoskeletal tissue engineering, it is widely acknowledged that mechanical stimulation plays a crucial role in the growth and maturation of tissues. To deliver the active mechanical loading required to promote tissue growth, simple bioreactor systems have traditionally been used to apply uniaxial stretching and compression [88]. Several commercially available bioreactors, such as the Ebers TC-3 [105], the BioTense [106], or the CellScale MCTX [107], operate on this principle. While these systems effectively provide basic mechanical stimulation, they are inherently limited by their lack of sensing and adaptive control [108]. This poses a challenge as the mechanical properties of engineered tissues evolve over time due to tissue remodeling through scaffold degradation and ECM deposition [6]. Therefore, a fixed set of mechanical stimulation parameters that may be appropriate at the beginning of culture may become inadequate as the tissue matures. To address this, Smith et al. [108] integrated a linear actuator into an autonomous robotic stimulator that dynamically adjusts the applied force in response to changes in tissue stiffness. This ensures a consistent relative force throughout the culture period, enhancing the reliability and effectiveness of mechanical stimulation.