Abstract

Objective

Early and accurate detection of COVID-19 and pneumonia through medical imaging is critical for effective patient management. This study aims to develop a robust framework that integrates synthetic image augmentation with advanced deep learning (DL) models to address dataset imbalance, improve diagnostic accuracy, and enhance trust in artificial intelligence (AI)-driven diagnoses through Explainable AI (XAI) techniques.

Methods

The proposed framework benchmarks state-of-the-art models (InceptionV3, DenseNet, ResNet) for initial performance evaluation. Synthetic images are generated using Feature Interpolation through Linear Mapping and principal component analysis to enrich dataset diversity and balance class distribution. YOLOv8 and InceptionV3 models, fine-tuned via transfer learning, are trained on the augmented dataset. Grad-CAM is used for model explainability, while large language models (LLMs) support visualization analysis to enhance interpretability.

Results

YOLOv8 achieved superior performance with 97% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, outperforming benchmark models. Synthetic data generation effectively reduced class imbalance and improved recall for underrepresented classes. Comparative analysis demonstrated significant advancements over existing methodologies. XAI visualizations (Grad-CAM heatmaps) highlighted anatomically plausible focus areas aligned with clinical markers of COVID-19 and pneumonia, thereby validating the model's decision-making process.

Conclusion

The integration of synthetic data generation, advanced DL, and XAI significantly enhances the detection of COVID-19 and pneumonia while fostering trust in AI systems. YOLOv8's high accuracy, coupled with interpretable Grad-CAM visualizations and LLM-driven analysis, promotes transparency crucial for clinical adoption. Future research will focus on developing a clinically viable, human-in-the-loop diagnostic workflow, further optimizing performance through the integration of transformer-based language models to improve interpretability and decision-making.

Keywords: YOLOv8, synthetic image augmentation, COVID-19 detection, pneumonia classification, medical image analysis

Introduction

Pneumonia is a contagious lung disease that causes inflammation in the alveoli, the tiny air sacs in the lungs responsible for oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange. 1 It is a significant global health concern, particularly for children, the elderly, and individuals with weakened immune systems. 2 Early detection and treatment of pneumonia are critical, as timely intervention can significantly improve patient outcomes. 3 However, diagnosing pneumonia poses challenges due to its symptoms often overlapping with other respiratory disease. 4

Traditionally, pneumonia is diagnosed through the analysis of chest X-ray images. While this method has been effective in many cases, it is not without limitations. 5 Identifying pneumonia from X-ray images is a complex task that heavily depends on the experience and expertise of medical professionals. Misinterpretation of images can lead to diagnostic errors, potentially delaying treatment and increasing patient risk. These challenges have prompted researchers to explore the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Recent advancements in deep learning (DL) and image processing technologies have revolutionized medical imaging. These tools have demonstrated immense potential for automating the detection of diseases, including pneumonia, by analyzing X-ray images with high precision and speed. 6 DL models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have shown remarkable performance in image classification tasks. 7 This study leverages advanced techniques, including synthetic image generation, transfer learning, and state-of-the-art DL models, to improve pneumonia detection.

One of the key innovations in this study is the use of Google's Frame Interpolation for Large Motion (FILM) technology. Originally designed for video processing, FILM enhances image quality by smoothing frames in videos or generating clearer images from sequences with large movements. 8 In the context of medical imaging, FILM is adapted to improve the quality of X-rays. By generating high-quality synthetic images, the model can better learn subtle features, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

Principal component analysis (PCA), a data reduction method, is another important technique in use. PCA simplifies complex datasets by removing irrelevant or redundant information while retaining the most critical features. 9 In this study, PCA highlights the essential features of X-ray images that are most relevant for diagnosis, enabling the model to focus on distinguishing between healthy and diseased lungs.

Additionally, this study utilizes the You Only Look Once (YOLO) model, specifically its latest iteration, YOLOv8. YOLO is a fast and effective object detection model widely applied in various domains, from autonomous driving to medical imaging. 10 YOLOv8 offers significant improvements in speed and accuracy compared to its predecessors. 11 For pneumonia detection, YOLOv8 excels at identifying subtle changes in X-ray images, enabling precise differentiation between pneumonia and other lung conditions.

One of the significant challenges in training DL models for medical imaging is the imbalance in datasets. Pneumonia datasets often contain more healthy images than diseased ones, which can bias the model and reduce its accuracy. 12 To address this, synthetic images were generated to balance the dataset. These artificial images mimic real X-rays, ensuring the model learns equally from all classes, thereby improving performance.

Transfer learning (TL) is another critical technique used in this study. This involves leveraging pre-trained models that have already learned features from large datasets, such as ImageNet. 13 By fine-tuning these models for pneumonia detection, high accuracy can be achieved even with limited data. This study employs several pre-trained models, including DenseNet121, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, and ResNet152V2. TL enables these models to adapt their learned features to pneumonia detection, reducing training time and enhancing efficiency.

Advanced CNN models like DenseNet121, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, and ResNet152V2 are renowned for their ability to extract detailed features from images. These models analyze images across multiple layers, capturing both low-level and high-level features.14–16 This multi-layered analysis makes them particularly effective for identifying complex diseases like pneumonia, where subtle differences in X-ray images may indicate the presence of disease. By combining these models with techniques like FILM and PCA, this study aims to maximize diagnostic accuracy.

Eliwa et al. 17 introduced a novel framework that integrates Microsoft Azure and blockchain technologies to ensure transparency and security in the classification of colon and lung cancer. Elmessery et al. 18 employed several Mix Transformer Encoders—specifically MiT-B5, MiT-B3, and MiT-B0—for the semantic segmentation of various diseases from strawberry leaf images. Additionally, Shams et al. 19 utilized the YOLOv8 model for real-time, on-site broiler live weight estimation.

Ameen et al. 20 conducted a comprehensive review of 82 prominent research articles on ECG- and PCG-based cardiovascular disease detection using DL and ML techniques. Mostafa et al. 21 applied feature reduction techniques in combination with ML algorithms to predict hepatocellular carcinoma. In a related study, Mostafa et al. 22 systematically examined DL approaches used to address feature selection challenges in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma.

The primary goal of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of modern medical image analysis technologies in detecting pneumonia and to develop a framework capable of providing accurate and reliable diagnoses. Pneumonia detection is a critical task in the medical field, as early and precise diagnosis can save lives. By integrating synthetic image generation, advanced DL models, and innovative techniques like FILM and PCA, this study seeks to push the boundaries of medical imaging capabilities.

The primary contributions of this study are as follows:

Framework for Pneumonia Classification: A framework is proposed to classify COVID-19, pneumonia, and normal cases using medical images, integrating advanced image processing, synthetic data generation, and DL techniques.

Innovative Use of FILM and PCA: Google's Frame Interpolation for Large Motion (FILM) and PCA are utilized to generate high-quality synthetic training and validation images, addressing dataset imbalance.

Advanced Detection Techniques: YOLOv8 and TL are applied for fast and accurate feature detection, enabling precise differentiation between pneumonia and COVID-19 cases.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section Related works provides a review of related works, highlighting previous studies and their contributions to pneumonia detection. Section Methodology details the methodology, describing the proposed framework, including the integration of transfer learning, synthetic data augmentation techniques such as FILM and PCA, and the YOLOv8 architecture. Section Results and discussion presents the experimental results, comparing the performance of the proposed method with benchmark models to demonstrate its effectiveness. Finally, Section Conclusion and future work concludes the paper by summarizing the findings and offering suggestions for future research directions.

Related works

Several studies have explored ML and DL methods for medical imaging and disease detection, particularly for pneumonia and other conditions.

In Huang et al., 23 the YOLOv8 algorithm, optimized for real-time object detection and medical imaging applications, was applied to a dataset of 3976 annotated liver images representing various liver disease cases. The study reported significant gaps in achieving consistently high precision (94%), recall (96%), and an mAP@0.5 rate of 59% for liver disease detection.

Rana and Bhushan 24 conducted an extensive review of ML classifiers such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forest (RF), and Naïve Bayes, alongside artificial neural networks and CNNs for disease detection. TL with large datasets of MRI, CT, and X-ray images was used to improve feature extraction and diagnostic accuracy.

Aceto et al. 25 reviewed nearly 600 scientific publications on information and communication technologies in healthcare, using Google Scholar and IEEE Xplore. They identified fragmented literature due to diverse research approaches across scientific disciplines, limiting the comprehensiveness of their findings.

Bhatt et al. 26 conducted a systematic review of DL models for medical diagnostics, emphasizing CNNs and recurrent neural networks (RNNs). While these models were effective, their complexity posed challenges for beginners.

Verma and Prakash 27 reviewed ML and DL techniques for detecting breast cancer using mammography, ultrasound, and MRI images. Their study summarized applications, findings, and challenges, especially in achieving high accuracy across diverse imaging types.

Bhatt and Shah 28 developed CNN architectures for pneumonia classification from chest X-rays using convolutional and pooling layers. They combined models with varying kernel sizes through ensemble learning, achieving a recall of 99.23%, an F1-score of 88.56%, an accuracy of 84.12%, and a precision of 80.04%.

Reshan et al. 29 used eight pre-trained models, including ResNet50, DenseNet121, Xception, and MobileNet, trained on datasets of 5856 and 112,120 chest X-ray images. MobileNet achieved the highest accuracy (94.23% and 93.75%) across both datasets, with performance improvements from simulations using different optimizers and batch sizes.

Yao et al. 30 proposed a new DL model, DenseDNN, for liver disease screening using liver function test data. It outperformed traditional ML methods and a standard DNN, achieving an AUC of 0.8919 on a large dataset.

Wong et al. 31 introduced a DL model called MSANet for classifying pneumonia types, including COVID-19, using chest CT images. MSANet achieved 97.46% accuracy, 97.31% precision, 96.18% recall, and a 96.71% F1-score by focusing on critical image features.

Attallah 32 established a diagnostic framework combining texture-based radiomics features and DL methods. Radiomics features such as the gray-level covariance matrix and discrete wavelet transform were extracted and used to train ResNet models. SVMs classified the fused features, achieving 99.47% sensitivity and 99.60% accuracy, outperforming models trained on original CT images.

Asnaoui et al. 33 fine-tuned various DCNNs, including VGG16, InceptionV3, and MobileNetV2, using 5856 chest X-rays. Their models achieved accuracies ranging from 83.14% to 96.61%. However, dataset biases and limited real-world validation affected generalizability.

Zhang et al. 34 employed VGG-based architectures with Dynamic Histogram Enhancement to improve image contrast while reducing model parameters. They achieved 96.068% accuracy, 94.408% precision, 90.823% recall, and a 92.851% F1-score but noted limitations due to reliance on a single architecture and limited dataset diversity.

Rajasenbagam et al. 35 developed a DCNN for pneumonia detection in chest X-rays using the Chest X-ray8 dataset. Data augmentation with Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) increased dataset size. Their VGG19-based model achieved a classification accuracy of 99.34% on previously unseen images.

Irede et al. 36 provided a comprehensive overview of X-ray imaging principles, covering mechanisms such as X-ray absorption, image formation, and advancements in imaging technologies like computed radiography and digital radiography. They discussed clinical roles in early diagnosis, monitoring disease progression, guiding interventions, and screening at-risk populations. Future research directions were also suggested, emphasizing the growing importance of X-ray imaging in infection detection.

Babukarthik et al. 37 developed a genetic deep CNN architecture that employs Huddle Particle Swarm Optimization in place of traditional gradient descent for the early detection of COVID-19 from chest X-ray images.

Moreover, Abdel and Abd 38 applied ML and CNN techniques to track trunk movement patterns in postpartum women experiencing low back pain. In a related study, Abdel et al. 39 utilized feature selection methods and ML algorithms to predict abdominal fat levels during the cavitation post-treatment phase. Furthermore, Mabrouk et al. 40 employed various regression models and optimization techniques to analyze scapular stabilization strategies aimed at alleviating shoulder pain in college students.

Abdel and Abd 41 also investigated the role of core muscles in female sexual dysfunction (FSD), exploring how machine and DL models can be used to predict changes in core muscle structure to support rehabilitation. FSD, which affects women of all ages, includes symptoms such as low libido, difficulty achieving orgasm, and painful intercourse. Their analysis incorporated models including MLP, LSTM, CNN, RNN, ElasticNetCV, RF, SVR, and Bagging Regressor—emphasizing the critical yet often overlooked importance of core muscles in FSD.

Finally, Eliwa et al. 42 proposed a CNN-based approach optimized with the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) algorithm to classify monkeypox skin lesions. The GWO-enhanced CNN achieved significantly higher accuracy than its non-optimized counterpart.

Methodology

Data collection

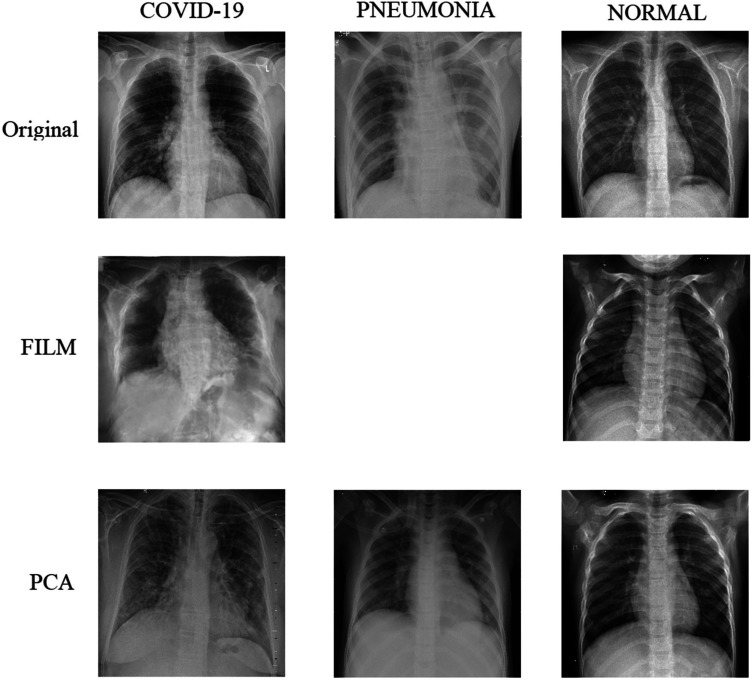

The chest X-ray (COVID-19 & Pneumonia) dataset 43 used in this study (sample shown in Figure 1) was sourced from Kaggle and consists of 6432 images categorized into three main classes: COVID-19, normal, and pneumonia. To ensure compatibility with the model, the images were resized and preprocessed to match the model's input size.

Figure 1.

Sample images of the dataset.

A key challenge in pneumonia detection datasets is class imbalance, particularly the relatively small number of pneumonia images. To address this issue, synthetic image generation techniques, specifically Feature Interpolation through Linear Mapping (FILM), were employed to generate additional pneumonia images, thereby balancing the dataset.

To further enhance image quality, the FILM was applied to improve image smoothness and clarity, resulting in higher quality data for model training. Additionally, PCA was used to reduce noise and emphasize critical features in the lung images, enabling the model to focus on the most relevant areas for accurate diagnosis.

The dataset was carefully structured (see Table 1) to maintain a consistent number of instances across the three classes: COVID-19, normal, and pneumonia, as summarized in Table 2. This balanced allocation minimizes class inconsistency during model training and ensures the model learns robust representations of each pathological case.

Table 1.

Comprehensive dataset structure.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Source | www.kaggle.com/datasets/prashant268/chest-xray-covid19-pneumonia |

| Total images | 6432 (Original) → 12,553 (After Augmentation) |

| Class Distribution | COVID-19: 576 (8.9%), Pneumonia: 4273 (66.4%), Normal: 1583 (24.6%) |

| Original split | Train: 80% (5144), Test: 20% (1288) - No validation set in original |

| Augmented split | Train: 11,253, Val: 11,254, Test: 1288 (20% of original) |

| Image specifications | Grayscale, Variable Original Dimensions → Uniform 256 × 256 (Lanczos4 resizing) |

| Augmented dataset link | www.kaggle.com/datasets/abdulhasibuddin/chest-x-ray-covid-19-and-pneumonia-aug-film-pca/data |

Table 2.

Data statistics (The original dataset can be found at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/prashant268/chest-X-ray-covid19-pneumonia).

| Dataset | COVID19 | Pneumonia | Normal | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Val | Test | Train | Val | Test | Train | Val | Test | Train | Val | Test | |

| Original | 460 | - | 116 | 3418 | - | 855 | 1266 | - | 317 | 5144 | - | 1288 |

| Augmented | 4266 | 4266 | 116 | 3418 | 3418 | 855 | 3569 | 3570 | 317 | 11,253 | 11,254 | 1288 |

Proposed system

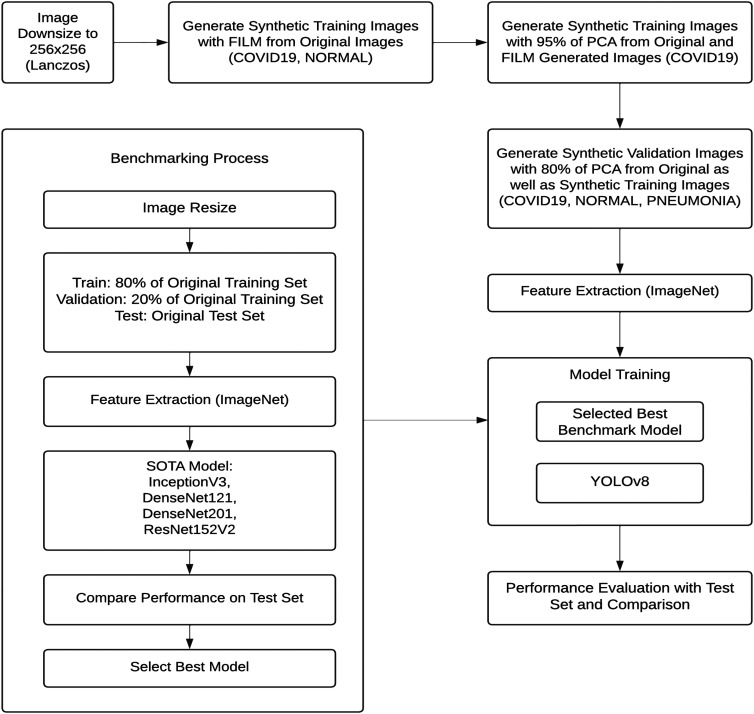

The proposed system aims to enhance the accuracy of pneumonia and COVID-19 detection by leveraging advanced DL techniques, synthetic image generation, and state-of-the-art models. Figure 2 illustrates the workflow diagram of the proposed framework, which follows a structured approach to process, augment, and classify medical images. Algorithm 1 shows the step-by-step process. The framework is designed to improve diagnostic performance while addressing data imbalance challenges.

Figure 2.

Proposed framework.

Step 1: Benchmarking and model selection

The process begins with benchmarking to evaluate the performance of several pre-trained DL models. During this step, the images are resized to a uniform resolution of 256 × 256 pixels using Lanczos interpolation. The dataset is split into training, validation, and testing sets, with 80% allocated for training, 20% for validation, and a separate test set reserved for evaluation.

Feature extraction is conducted using ImageNet pre-trained models such as InceptionV3, DenseNet121, DenseNet201, and ResNet152V2 to capture meaningful features from the X-ray images. The models are assessed based on performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The best-performing model is selected as the benchmark for further development.

Algorithm 1: Proposed Framework for COVID-19/Pneumonia Classification. —

Step 2: Image enhancement and synthetic data generation

Algorithm 2: FILM-PCA Synthetic Image Generation —

To address the issue of class imbalance, particularly for pneumonia images, synthetic image generation techniques are applied (see Algorithm 2). Frame Interpolation for Large Motion (FILM) is used to generate additional images from the original dataset. FILM enhances image quality by smoothing and clarifying X-ray images, making them more informative for the model.

Additionally, PCA is employed to reduce noise and highlight essential features of the lung regions, further improving image quality for training. Synthetic images are generated for all classes, including COVID-19, normal, and pneumonia. Augmented pneumonia images are specifically designed to increase training data for this underrepresented class. These synthetic images are integrated into the training and validation sets to balance the dataset and enhance model performance.

Step 3: Transfer learning and YOLOv8 model

After incorporating synthetic images, feature extraction is repeated using the ImageNet pre-trained models to prepare the data for training. TL is employed by fine-tuning the weights of pre-trained models such as DenseNet121, DenseNet201, and InceptionV3 for pneumonia and COVID-19 detection. This approach allows the system to leverage features learned from large-scale image recognition tasks, enhancing performance on medical imaging despite limited data.

The YOLOv8 model, a cutting-edge object detection model, is then applied to detect and classify pneumonia and COVID-19 in X-ray images. Known for its speed and accuracy, YOLOv8 is well-suited for real-time medical imaging applications. It identifies pneumonia by detecting distinctive features such as lung opacity, commonly observed in infected individuals.

Step 4: Training and evaluation

In the final step, the YOLOv8 model is trained using both synthetic and real images from the augmented dataset. The model is fine-tuned starting from the best-performing benchmark model. The system's performance is evaluated on a separate test set comprising both original and augmented images, which remains unseen during training. This ensures an unbiased evaluation of the model's generalization capability.

Hyper-parameter configuration

To ensure optimal performance, specific hyper-parameter settings were applied to each component of the proposed framework. These hyper-parameters (see Table 3) were carefully tuned to enhance model accuracy, reduce overfitting, and maintain computational efficiency. The key hyper-parameters used for benchmarking, synthetic image generation, and model training are detailed below.

Table 3.

Hyper-parameters used for analysis.

| Component | Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmarking | Batch size | 16 | Fixed for all pre-trained models (InceptionV3, DenseNet, ResNet). |

| Learning rate | 0.001 | Initial LR for RMSProp optimizer. | |

| Image dimensions | 256 × 256 | Resized using Lanczos interpolation. | |

| Early stopping patience | 5 epochs | Training halted if validation loss did not improve for 5 epochs. | |

| FILM augmentation | Interpolation cycles | 2 | Two FILM passes per image pair to enhance smoothness. |

| Fill value | 0.5 | Pixel blending ratio for motion interpolation. | |

| PCA variance retained | 95% (train), 80% (val) | Retained eigenvalues to balance feature preservation and noise reduction. | |

| YOLOv8 training | Optimizer | AdamW | Combines Adam's adaptive LR with L2 regularization (weight decay=0.0005). |

| Initial learning rate | 0.01 | Linearly decayed to 0.0001 (lrf=0.01). | |

| Momentum | 0.9 | Nesterov momentum for gradient updates. | |

| Flip augmentation | Left-right (p = 0.5), Up-down (p = 0) | Horizontal flips to improve generalization. |

FILM: Frame Interpolation for Large Motion; PCA: principal component analysis; YOLO: You Only Look Once.

Benchmarking parameters

The following hyper-parameters were employed during the benchmarking process for the selected pre-trained models:

Batch Size: 16

Validation Split: 0.2

Image Dimensions: (256, 256)

Rescale Factor: Each image pixel value was normalized using the formula: x’ = , where x is the original pixel intensity.

Initial Weights: Pre-trained on ImageNet.

Learning Rate (LR): 0.001

Epsilon (ε): 0.0001, used for numerical stability in the optimization process.

Early Stopping: Training was halted if the validation loss (Lval) did not improve by at least 0.0009 (min_delta) for five consecutive epochs. This criterion is expressed as: Lval (epochi+1)—Lval (epochi) < 0.0009, where i represents the epoch index.

Loss Function: Categorical cross-entropy, defined as: Loss =— , where (ytrue) is the true label, and (ypred) is the predicted probability.

Classifier Activation: Softmax, calculated as: softmax(xi) = for all j, where xi is the logit score for class i.

Optimizer: RMSProp, with weight updates defined as: wt + 1 = wt − * gradt, where lr is the learning rate, Gt is the accumulated squared gradients, is a small constant, and gradt is the gradient at step t.

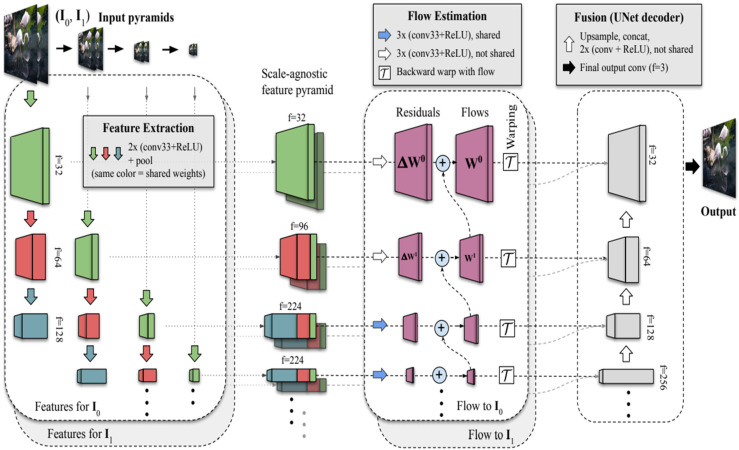

FILM hyper-parameters

Figure 3 illustrates the architecture of the Frame Interpolation for Large Motion (FILM) technique. The following parameters were applied for synthetic image generation:

Fill Value: 0.5, used to interpolate missing pixels during the motion estimation process.

Image Resize Dimensions: All images were resized to 256 × 256 using Lanczos interpolation. The resized pixel value p’(x, y) at position (x, y) computed as a weighted sum of neighboring pixel values p(i, j): p’(x, y) = , where wij are Lanczos kernel weights, and (i, j) represent neighboring pixel coordinates.

Interpolation Cycles: Two iterations of interpolation were performed to enhance image smoothness and clarity.

Figure 3.

Frame Interpolation for Large Motion (FILM) mechanism. 8

YOLOv8 model training parameters

The YOLOv8 model was fine-tuned for pneumonia and COVID-19 detection using the following hyper-parameters:

Image Size: 256 × 256 pixels

Patience: 5 epochs, with early stopping based on validation metrics

Batch Size: 16

Initial Learning Rate (lr0): 0.01

Learning Rate Final Ratio (lrf): 0.01, meaning the learning rate decayed linearly from lr0 to lr0 * lrf over the training process

Momentum: 0.9, calculated as: velocityt = momentum * velocityt−1 + lr * gradt, where velocityt is the current update, gradt is the gradient, and lr is the learning rate

Weight Decay: 0.0005, used as a regularization term in the loss function: Lossreg = Lossoriginal + weightdecay * , where w represents model weights

- Flip Probability:

- Flip Up-Down: 0.0

- Flip Left-Right: 0.5

Optimizer: AdamW, with weight updates computed as follows:

mt = β1 * mt−1 + (1 − β1) * gradt

vt = β2 * vt−1 + (1 − β2) *

wt + 1 = wt − lr *

where β1 and β2 are exponential decay rates for the first and second moments, gradt is the gradient, and is a small constant for numerical stability.

These hyper-parameters contributed to the success of the proposed framework, ensuring high classification accuracy and robustness across imbalanced datasets.

Performance metrics

To evaluate the proposed framework, standard classification metrics were used: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. These metrics were computed using the components of the confusion matrix: True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN).

Accuracy: Measures the proportion of correctly classified instances (both positive and negative) out of the total number of instances:

| (1) |

Precision: Also called Positive Predictive Value, Precision calculates the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances out of all instances predicted as positive:

| (2) |

Recall: Also known as Sensitivity or True Positive Rate, Recall measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances out of all actual positive instances:

| (3) |

F1-score: The harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a balance between the two metrics:

| (4) |

Computational resources

The experiments were conducted on Kaggle's free tier, which provides:

Hardware: 15GB NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU, 29GB RAM.

Software: Python 3.10, TensorFlow 2.12, PyTorch (YOLOv8), and scikit-learn (results analysis).

Visualization: Matplotlib and Seaborn for plotting.

Deployment Considerations and Cost:

For deployment, a mid-range GPU (e.g. NVIDIA RTX 3060/3070) would be sufficient to run inference.

The software stack is based on open-source libraries, minimizing licensing costs.

Cloud-based deployment using services such as AWS or Google Cloud can incur operational expenses; however, inference tasks (as opposed to training) are computationally lightweight, especially with YOLOv8's optimization for speed.

YOLOv8's low inference latency and memory footprint make it suitable for edge devices or on-premise deployment in hospitals or mobile screening units.

Results and discussion

Benchmark performances

This section presents the benchmarking results for the selected state-of-the-art models, including DenseNet121, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, and ResNet152V2, integrated with TL, as summarized in Table 4. The benchmarking process evaluated each model's performance on the original dataset.

Table 4.

Performance comparison for the proposed framework.

| Methodology | Year | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. 23 | 2024 | - | 94 | 96 | - |

| Bhatt and Shah 28 | 2023 | 84.12 | 80.04 | 99.23 | 88.56 |

| Reshan et al. 29 | 2023 | 93.75 | 91.36 | 94.39 | 93.18 |

| DenseNet121 + TL | - | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 |

| DenseNet201 + TL | - | 91 | 92 | 91 | 92 |

| InceptionV3 + TL | - | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 |

| ResNet152V2 + TL | - | 83 | 84 | 83 | 83 |

| Proposed framework (InceptionV3) | - | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| Proposed framework (YOLOv8) | - | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

YOLO: You Only Look Once; TL: transfer learning.

DenseNet121 with Transfer Learning: DenseNet121 achieved an accuracy of 92%, precision of 92%, recall of 92%, and an F1-score of 92%. The model demonstrated robust performance, effectively identifying both positive and negative cases. Its ability to capture complex patterns in the data while maintaining computational efficiency underscores its reliability for medical image classification.

DenseNet201 with Transfer Learning: DenseNet201 performed slightly below DenseNet121, with an accuracy of 91%, precision of 92%, recall of 91%, and an F1-score of 92%. While the model offered comparable precision, its slightly lower recall indicated occasional misclassification of true positive cases. This limitation could be attributed to its deeper architecture, which typically requires larger datasets to generalize effectively.

InceptionV3 with Transfer Learning: InceptionV3 emerged as the best-performing model among the benchmarks, achieving an accuracy of 94%, precision of 94%, recall of 94%, and an F1-score of 94%. Its ability to extract features at multiple scales through its unique inception modules contributed to its superior performance. This model's balanced performance across all metrics made it the optimal choice as the baseline for the proposed framework.

ResNet152V2 with Transfer Learning: ResNet152V2 achieved an accuracy of 83%, precision of 84%, recall of 83%, and an F1-score of 83%. The comparatively lower performance could be attributed to its very deep architecture, which may not have been well-suited to the size of the available dataset. The model's tendency to overfit or underperform on smaller datasets likely explains its reduced classification efficiency.

InceptionV3 performances

The InceptionV3 model, integrated with the proposed framework, achieved a test accuracy of 96.43%, demonstrating a significant improvement over the benchmark results. A detailed performance analysis based on the confusion matrix and classification report is provided below.

COVID-19 Class (116 samples): Out of 116 COVID-19 cases, 115 were correctly classified, with only one misclassified as PNEUMONIA. This reflects an exceptional recognition rate for this critical class, achieving precision and recall values exceeding 97%. The model's reliability in detecting COVID-19 is evident, with minimal false positives and false negatives, which is crucial for accurate diagnosis during pandemics.

Normal Class (317 samples): Among the normal cases, 285 were correctly identified, while 29 were misclassified as PNEUMONIA and 3 as COVID-19. This results in a recall of 90%, indicating challenges in distinguishing normal cases from PNEUMONIA, likely due to overlapping radiographic features in chest X-rays. However, the high precision of 96% suggests the model remains robust in identifying normal cases, with a low rate of false positives.

PNEUMONIA Class (855 samples): For the PNEUMONIA class, 842 samples were correctly classified, with 13 misclassified as normal and none as COVID-19. This performance is reflected in a recall of 98% and a precision of 97%, underscoring the model's ability to accurately detect and differentiate PNEUMONIA cases, thereby minimizing diagnostic errors for this prevalent condition.

The model exhibits consistent precision across all classes, with values of 97% for COVID-19 and 96% for normal cases. This highlights the reliability of the predictions, particularly for critical classes such as COVID-19, where false positives can lead to unnecessary medical interventions. High recall values of 99% for COVID-19 and 98% for PNEUMONIA demonstrate the model's strong capability to identify true positive cases. However, the slightly lower recall of 90% for the normal class suggests potential areas for improvement, as some normal cases were misclassified, likely due to subtle similarities with mild PNEUMONIA cases.

Additionally, F1-scores of 0.98 for both COVID-19 and PNEUMONIA reflect near-perfect performance in diagnosing these conditions. The normal class, with an F1-score of 0.93, indicates an acceptable balance between precision and recall but highlights room for refinement to address false negatives. The model's overall accuracy of 96.43% validates the effectiveness of the proposed framework in handling imbalanced datasets and recognizing subtle variations in chest X-rays.

However, the slightly lower recall for the normal class highlights a need for further refinement. Misclassification of normal cases as PNEUMONIA could result from shared radiographic features between mild PNEUMONIA and healthy lungs. Addressing this issue could involve incorporating additional preprocessing techniques and introducing more robust model architectures to enhance differentiation.

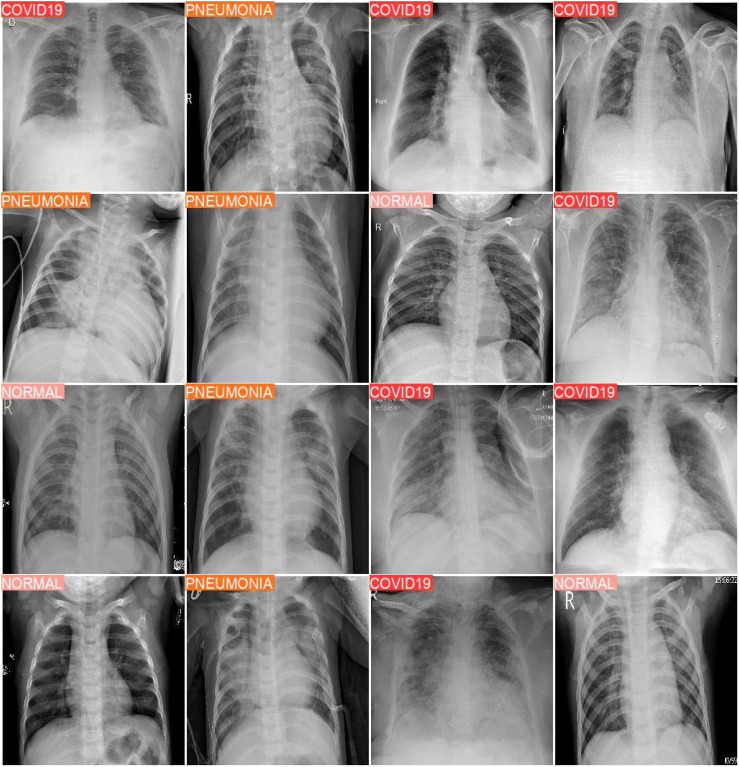

YOLOv8 performances

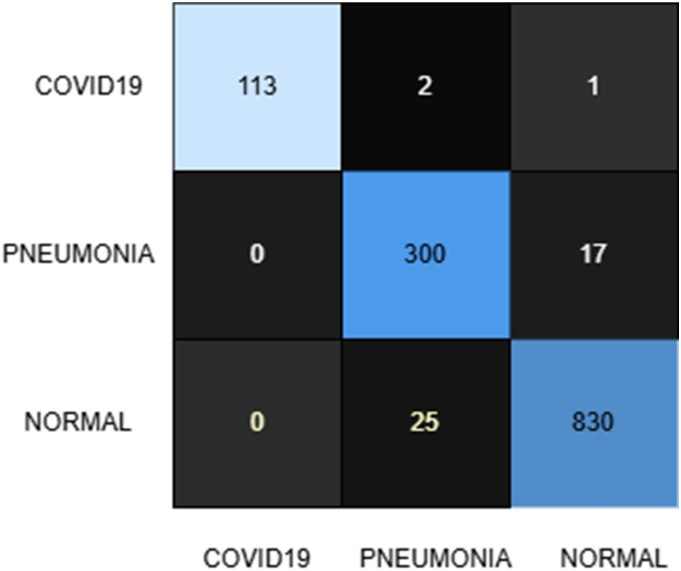

The YOLOv8 model, applied within the proposed framework, achieved an impressive test accuracy of 97%, surpassing the benchmark and demonstrating robust classification performance across all classes. Sample classification outputs are provided in Figure 4, while the confusion matrix (see Figure 5) and classification report (Table 5) offer a detailed breakdown of the results, as summarized below.

Figure 4.

Sample of experimental result output for YOLOv8 model trained on the augmented dataset. YOLO: You Only Look Once.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix for the YOLOv8 model after training on the produced dataset containing synthetic images. YOLO: You Only Look Once.

Table 5.

Classification report of the YOLOv8 model after training on the produced dataset containing synthetic images.

| Precision | Recall | F1-score | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covid19 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 116 |

| Normal | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 317 |

| Pneumonia | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 855 |

| Accuracy | 0.97 | 1288 | ||

| Macro AVG | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1288 |

| Weighted AVG | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1288 |

YOLO: You Only Look Once.

COVID-19 Class (116 samples): Out of 116 COVID-19 cases, 114 were correctly identified, with two misclassified as normal and none as PNEUMONIA. This results in a recall of 98% and a precision of 100%, highlighting the model's exceptional ability to correctly identify COVID-19 cases while completely avoiding false positives for this class. The F1-score of 0.99 reflects a near-perfect balance between precision and recall, underscoring the model's reliability for this critical condition.

Normal Class (317 samples): Among the normal cases, 300 were correctly classified, with 17 misclassified as PNEUMONIA and none as COVID-19. This corresponds to a recall of 95%, showing a significant improvement over the InceptionV3 model. However, a precision of 92% indicates a slightly higher false positive rate due to normal cases being misclassified as PNEUMONIA. The F1-score of 0.93 demonstrates the model's reliability while highlighting the potential for reducing false alarms.

PNEUMONIA Class (855 samples): For the PNEUMONIA class, 831 samples were correctly classified, with 24 misclassified as normal and none as COVID-19. A recall of 97% and precision of 98% emphasize the model's effectiveness in detecting PNEUMONIA cases while minimizing both false negatives and false positives. The F1-score of 0.98 reflects a high level of robustness in diagnosing this class.

We have implemented an ensemble learning strategy by combining the predictions of the InceptionV3 and YOLOv8 models to enhance classification accuracy and robustness. The ensemble model aggregates predictions to reduce individual model biases and improve overall generalization performance.

The classification results of the ensemble model are presented in Table 6, highlighting precision, recall, and F1-scores for three classes: Covid-19 (1.00, 0.97, 0.99), Normal (0.95, 0.94, 0.94), and Pneumonia (0.98, 0.98, 0.98), with an overall accuracy of 0.97. These results confirm the effectiveness of the ensemble approach in enhancing diagnostic performance.

Table 6.

Classification report of the ensemble of YOLOv8 and inceptionV3 models.

| Precision | Recall | F1-score | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covid19 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 116 |

| Normal | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 317 |

| Pneumonia | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 855 |

| Accuracy | 0.97 | 1288 | ||

| Macro AVG | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1288 |

| Weighted AVG | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1288 |

YOLO: You Only Look Once.

Key observations

Precision: Precision values are notably high across all classes, with 100% for COVID-19, emphasizing the model's ability to avoid false positives in critical diagnoses. PNEUMONIA achieves an excellent precision of 98%, while the normal class attains a commendable 92%. However, further improvements could reduce false positives for the normal class.

Recall: The model achieves a recall of 98% for COVID-19 and 97% for PNEUMONIA, demonstrating its ability to accurately identify true positive cases for these critical conditions. The recall of 95% for the normal class indicates significant improvement over the InceptionV3 model, showcasing a stronger ability to avoid false negatives for healthy cases.

F1-Score: F1-scores of 0.99 for COVID-19 and 0.98 for PNEUMONIA demonstrate near-optimal performance for these classes. The normal class's F1-score of 0.93 reflects an acceptable trade-off between precision and recall, though further refinement could enhance overall performance.

Performance summary

The YOLOv8 model exhibits outstanding performance, particularly for the COVID-19 and PNEUMONIA classes. Its ability to completely avoid false positives for COVID-19 ensures exceptional reliability in critical diagnostics, a vital feature in high-stakes scenarios such as pandemic management. The model also demonstrates significant improvement in classifying normal cases, with a recall of 95%, reducing the likelihood of misclassifying healthy cases as pathological conditions.

Areas for improvement

Despite its strong performance, the normal class's precision of 92% highlights a tendency to misclassify some healthy cases as PNEUMONIA. This issue may stem from overlapping visual features in chest X-rays between mild PNEUMONIA and normal lungs. Addressing this challenge could involve incorporating additional preprocessing techniques or refining the augmentation strategy to better represent the variability in normal cases.

Comparative analysis

The comparison in Table 4 between the proposed framework and previously published methodologies highlights significant advancements in medical image classification for COVID-19 and pneumonia detection.

Among the published works, Huang et al. 23 reported precision and recall values of 94% and 96%, respectively, but did not specify accuracy or F1-score. While these results reflect strong detection capabilities, the absence of comprehensive metrics limits a full performance evaluation. Similarly, Bhatt and Shah 28 achieved an accuracy of 84.12%, precision of 80.04%, recall of 99.23%, and an F1-score of 88.56%, indicating moderate performance with room for improvement, particularly in accuracy and precision. Reshan et al. 29 reported better results, achieving an accuracy of 93.75%, precision of 91.36%, recall of 94.39%, and an F1-score of 93.18%, reflecting a balanced performance across evaluation metrics.

The benchmarking step of the proposed framework evaluated state-of-the-art models integrated with transfer learning. DenseNet121 + TL and DenseNet201 + TL both exhibited consistent performance, with DenseNet121 + TL achieving an accuracy of 92% across all metrics. DenseNet201 + TL showed similar results but with a slightly lower recall (91%) while maintaining high precision (92%). InceptionV3 + TL, the best-performing benchmark model, achieved an accuracy of 94%, with precision, recall, and F1-scores all at 94%. In contrast, ResNet152V2 + TL demonstrated comparatively lower performance, with an accuracy of 83%, precision of 84%, and recall of 83%, suggesting challenges in achieving consistent classification.

The proposed framework significantly improved performance metrics when integrated with either InceptionV3 or YOLOv8. InceptionV3 within the proposed framework achieved an accuracy of 96%, with precision, recall, and F1-scores all at 96%, surpassing all benchmark models and previously reported methodologies. This improvement demonstrates the effectiveness of integrating synthetic image generation and advanced preprocessing techniques such as FILM and PCA. Furthermore, YOLOv8, implemented within the proposed framework, outperformed all other methods, achieving the highest accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score of 97%. This exceptional performance highlights YOLOv8's ability to learn effectively from augmented and diverse datasets, ensuring robust classification of all three classes: COVID-19, NORMAL, and PNEUMONIA.

Key factors behind YOLOv8's success

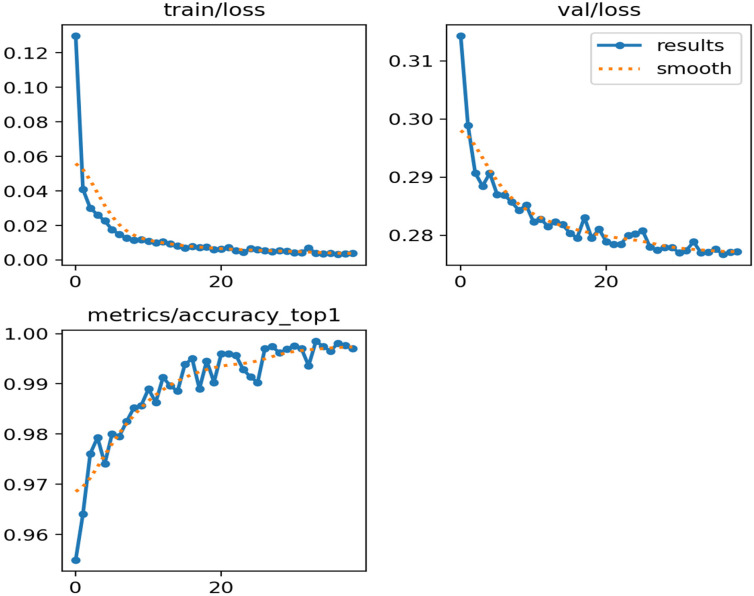

The remarkable performance of YOLOv8 with TL (Figure 6), trained on a dataset enhanced with FILM and PCA synthetic images, can be attributed to several factors:

Figure 6.

Training loss, validation loss, and accuracy tendency while training the YOLOv8 model with transfer learning in the proposed framework. YOLO: You Only Look Once.

Advanced Architecture: YOLOv8, as a state-of-the-art object detection model, combines real-time inference capabilities with high accuracy. 11 Its multi-scale feature extraction architecture efficiently captures spatial variations in chest X-ray images, enabling precise classification of COVID-19, NORMAL, and PNEUMONIA cases.

Transfer Learning: Utilizing pre-trained weights from ImageNet provided YOLOv8 with a strong initialization, facilitating rapid adaptation to domain-specific features of medical X-ray imagery. This minimized overfitting and accelerated model convergence. 13

Synthetic Image Generation with FILM: FILM-generated synthetic images enriched the dataset by introducing diverse and realistic variations. FILM enhances image quality by interpolating frames to create smoother, clearer images, allowing the model to learn detailed features. This diversity enabled the model to generalize better to unseen test data. 8

Feature Refinement with PCA: PCA further improved the dataset by reducing noise and emphasizing critical lung features. Retaining 95% of the variance for synthetic training data and 80% for validation data ensured that only the most relevant features were preserved. This guided the YOLOv8 model to focus on diagnostically significant regions, enhancing precision and recall.

Class Imbalance Mitigation: Addressing the class imbalance in the original dataset was critical to the model's success. The inclusion of FILM and PCA synthetic images balanced the dataset by providing sufficient samples of all classes during training. This reduced bias and improved classification performance across all categories. 12

Optimization Strategies: The use of an adaptive learning rate, the AdamW optimizer, and regularization techniques contributed to YOLOv8's effective convergence. These optimization strategies ensured that the model learned robust feature representations without overfitting, even with an expanded dataset. 44

Image Preprocessing: Consistently resizing all images to a 256 × 256 resolution using Lanczos interpolation (which balances sharpness and smoothness during image resampling 45 ), coupled with YOLOv8's ability to efficiently process high-resolution input, preserved critical diagnostic details. This enhanced the model's capability to distinguish between classes with overlapping visual features.

Limitations

Despite the high performance achieved by the proposed model, there are important limitations to consider. During training, both the training and validation accuracy reached nearly 100%, while the corresponding losses approached zero. This suggests limited capacity for further learning on the current dataset (see Table 2: Augmented dataset). Notably, both the training and validation sets consist of synthetic data, whereas the test set includes only real-world data. Although a test accuracy of 97% was achieved, it indicates that the synthetic data may lack sufficient diversity or realism, and future work should focus on improving the quality and diversity of the synthetic dataset.

Discussion

Our results (97% accuracy with YOLOv8) surpass prior work (see Table 4) by 3–13% by utilizing FILM's Motion-Aware Augmentation and PCA-Guided Noise Reduction. Unlike GANs, FILM preserves anatomical structures (Figure 3), reducing artifacts. On the other hand, PCA with 95% variance (Section Step 2: Image enhancement and synthetic data generation) improved focus on diagnostically relevant regions. Nonetheless, misclassification of normal cases as pneumonia (5% FP rate) may require radiologist oversight. While synthetic data takes care of class imbalance, it cannot fully replicate rare pathologies (e.g. COVID-19 variants). Future work will integrate clinician feedback to refine false positives.

In term of computational efficiency, the proposed framework's training times were measured on a NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU (16GB VRAM). YOLOv8 demonstrated faster per-epoch processing (235s vs. 250.2 s). Total training times were 3753 s (InceptionV3) and 2820s (YOLOv8), reflecting a 24.8% reduction for YOLOv8. These metrics confirm the framework's suitability for real-world deployment where efficiency is critical.

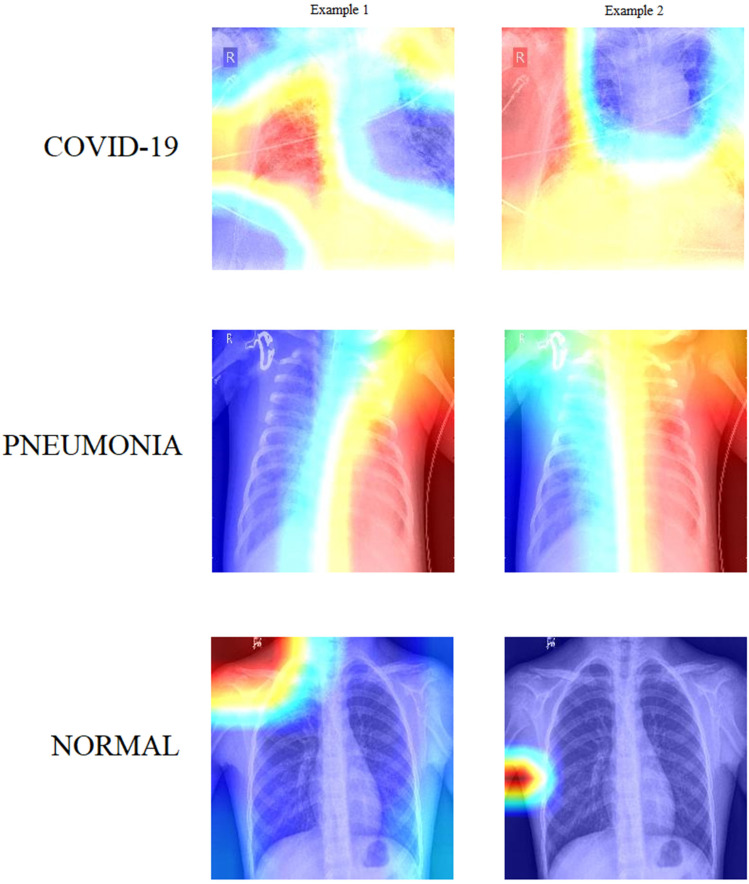

Visualization

To better understand how the model interprets input images, we applied Grad-CAM, a widely used explainable AI technique, to generate class activation maps. Figure 7 presents Grad-CAM heatmaps for representative cases from each of the three classes (COVID-19, NORMAL, and PNEUMONIA). These visualizations reveal which regions of the X-ray images the models focused on during classification.

Figure 7.

Feature visualization using grad-CAM.

To analyze these visualizations, we incorporated large language models to automatically describe the salient features identified by the model. This supports our broader vision of developing a clinically adoptable, human-in-the-loop diagnostic workflow.

COVID-19—Example 1: In this Grad-CAM visualization, the model is highly focused on the peripheral region of the left lung, particularly in the mid-to-lower zone. The intense red coloration in this area indicates that the model considered it a key feature for classifying COVID-19. This aligns with common radiological patterns seen in COVID-19 pneumonia, where ground-glass opacities and consolidations typically appear in peripheral and lower lung zones, often bilaterally but not always symmetrically. The model appears to have identified subtle opacity in this region, suggesting alveolar damage or inflammation—typical markers of COVID-19. The right lung and central thoracic area, shown in cooler (blue) tones, contributed less to the classification, which is also consistent with the disease's early presentation as patchy, localized abnormalities.

COVID-19—Example 2: This image displays a different pattern. The Grad-CAM heatmap highlights a vertically elongated region in the center of the thorax, primarily aligning with the mediastinum and lower lung zones. The left peripheral lung region also shows moderate activation. This spread of focus could indicate the model's response to more diffuse involvement or bilateral opacities, often observed in moderate or advanced cases of COVID-19. The red-to-yellow transition around the mediastinal area may reflect attention to vascular prominence, interstitial thickening, or bilateral consolidations. The cool blue tones in the central lung fields suggest regions that contributed little to the classification, possibly due to their clarity or minimal anomalies. Compared to Example 1, this visualization suggests a more extensive distribution, potentially indicating disease progression.

Pneumonia—Example 1: This Grad-CAM heatmap shows strong activation on the right side of the thorax, particularly in the mid-to-lower lung fields, extending laterally. The model's focus in this region—represented by a vibrant red band—suggests localized opacity or consolidation, which is characteristic of bacterial pneumonia. The vertical alignment of the red zone could indicate lobar pneumonia affecting the right lower lobe. The left lung appears deep blue, indicating that it was largely ignored during decision-making. This unilateral focus aligns with the presentation of focal infections, distinguishing it from the typically bilateral nature of COVID-19.

Pneumonia—Example 2: The second pneumonia image also reveals an asymmetrical pattern, with high Grad-CAM activation on the right hemithorax and minimal contribution from the left. However, the area of attention forms a more diffuse vertical strip, slightly more centrally aligned compared to Example 1. The model may be attending to perihilar or central lobe involvement, possibly indicating atypical pneumonia or multi-lobar infection on the right side. Once again, the left thorax and mediastinum show little activation. The slightly more diffuse pattern may hint at overlapping features with viral infections, though the model still confidently classifies it as pneumonia.

Normal—Example 1: In this case, the Grad-CAM highlights an area near the left shoulder and upper thoracic wall, far from the central lung fields. The lungs themselves are rendered in cool blue, indicating the model found no significant radiological abnormalities in the lung parenchyma. The red hotspot near the shoulder may correspond to non-pathological features—such as clavicular overlap, muscle shadows, or even training noise. This peripheral focus typically occurs when the model detects no disease-relevant patterns in the lung and instead relies on regions that help confirm the absence of pathology. Overall, the visualization supports the “Normal” classification.

Normal—Example 2: This image displays an even more definitive signature of normality. The model's attention is entirely outside the lung fields, especially around the lower left lateral edge of the thorax. The lung fields, heart shadow, and diaphragm appear in cool blue shades, indicating no meaningful activation. The red activation is concentrated over the soft tissue near the arm or ribs, again suggesting the model is relying on non-lung cues in the absence of pathology. This pattern may reflect the model's learned baseline for normal anatomical structures. The Grad-CAM clearly indicates that no intrapulmonary regions influenced the classification, reinforcing the accuracy of the “Normal” label.

Conclusion and future work

This study presents a robust framework for classifying COVID-19, NORMAL, and PNEUMONIA cases using advanced techniques, including FILM and PCA for synthetic data generation, as well as YOLOv8 for transfer learning. The proposed approach effectively addresses class imbalance and improves dataset quality, resulting in enhanced classification performance. YOLOv8 achieved the highest accuracy of 97%, showcasing its effectiveness in handling the complexity of medical imaging data.

For future work, we plan to explore more advanced synthetic data generation techniques by integrating GANs and Variational Autoencoders to enhance the realism of generated images. Additionally, incorporating data from similar public datasets could further improve diversity. Extensive cross-validation and hyper-parameter tuning will also be considered to optimize performance. Moreover, integrating a human-in-the-loop approach could enable more trustworthy deployment of the framework within real-world clinical settings.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Uddin A. Hasib https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1000-2600

Jing Yang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8132-8395

Chin Soon Ku https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0793-3308

Lip Yee Por https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5865-1533

Ethical considerations: Ethical approval was not required for this study as we analyzed publicly available data that was not collected from human subjects but from publicly available symptom checker apps.

Author contributions: AHU contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and writing-original draft. MAR contributed to validation and data curation. JY contributed to software and formal analysis. UAB contributed to validation. CSK contributed to data curation, validation, and writing—review and editing. LYP contributed to conceptualization, Methodology, supervision, formal analysis, project administration, validation, and writing—review and editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by National Science and Technology Council in Taiwan under grant number NSTC-113-2224-E-027-001 and the KW IPPP (Research Maintenance Fee) Individual/Centre/Group (RMF1506-2021) at Universiti Malaya, Malaysia. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement: This study obtained research data from publicly available online repositories. We mentioned their sources using proper citations. Here is the link to the data https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/prashant268/chest-X-ray-covid19-pneumonia.

References

- 1.Mayo Clinic. Pneumonia - symptoms and causes. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pneumonia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354204 (accessed 25 November 2024).

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). Pneumonia. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/pneumonia (accessed 25 November 2024).

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumonia. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/index.html (accessed 25 November 2024).

- 4.Cleveland Clinic. Pneumonia: Causes, symptoms, diagnosis & treatment. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4471-pneumonia (accessed 25 November 2024).

- 5.American Lung Association. Pneumonia symptoms and diagnosis. Available at: https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/pneumonia/symptoms-and-diagnosis (accessed 25 November 2024).

- 6.Wang X, Peng Y, Lu L, et al. ChestX-ray8: Hospital-Scale chest X-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, pp.3462–3471. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM 2017; 60: 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reda F, Kontkanen J, Tabellion E, et al. FILM: frame interpolation for large motion. pp.250–266.

- 9.Jolliffe I. Principal component analysis. In: Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. Chichester: Wiley, 2005, pp.1580–1584. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, et al. You only Look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, pp.779–788. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Li X, Chen J, et al. DPH-YOLOv8: improved YOLOv8 based on double prediction heads for the UAV image object detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 2024; 62: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.He H, Garcia EA. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng 2009; 21: 1263–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, et al. Imagenet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp.248–255: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, et al. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp.2261–2269: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szegedy C, Vanhoucke V, Ioffe S, et al. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp.2818–2826: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 16.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp.770–778: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eliwa EHI, Mohamed El Koshiry A, Abd El-Hafeez T, et al. Secure and transparent lung and colon cancer classification using blockchain and microsoft azure. Adv Respir Med 2024; 92: 395–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elmessery WM, Maklakov DV, El-Messery TM, et al. Semantic segmentation of microbial alterations based on SegFormer. Front Plant Sci 2024; 15: 1352935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shams MY, Elmessery WM, Oraiath AAT, et al. Automated on-site broiler live weight estimation through YOLO-based segmentation. Smart Agr Technol 2025; 10: 100828. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ameen A, Fattoh IE, Abd El-Hafeez T, et al. Advances in ECG and PCG-based cardiovascular disease classification: a review of deep learning and machine learning methods. J Big Data 2024; 11: 159. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mostafa G, Mahmoud H, Abd El-Hafeez T, et al. Feature reduction for hepatocellular carcinoma prediction using machine learning algorithms. J Big Data 2024; 11: 88. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mostafa G, Mahmoud H, Abd El-Hafeez T, et al. The power of deep learning in simplifying feature selection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2024; 24: 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang J, Li C, Yan F, et al. An improved liver disease detection based on YOLOv8 algorithm. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 2024; 15: 1168–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rana M, Bhushan M. Machine learning and deep learning approach for medical image analysis: diagnosis to detection. Multimed Tools Appl 2023; 82: 26731–26769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aceto G, Persico V, Pescapé A. The role of information and communication technologies in healthcare: taxonomies, perspectives, and challenges. J Netw Comput Appl 2018; 107: 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatt C, Kumar I, Vijayakumar V, et al. The state of the art of deep learning models in medical science and their challenges. Multimed Syst 2021; 27: 599–613. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verma G, Prakash S. Pneumonia classification using deep learning in healthcare. Int J Innov Technol Explor Eng 2020; 9: 1715–1723. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhatt H, Shah M. A convolutional neural network ensemble model for pneumonia detection using chest X-ray images. Healthc Anal 2023; 3: 100176. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reshan MSA, Gill KS, Anand V, et al. Detection of pneumonia from chest X-ray images utilizing MobileNet model. Healthcare 2023; 11: 1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao Z, Li J, Guan Z, et al. Liver disease screening based on densely connected deep neural networks. Neural Netw 2020; 123: 299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong PK, Yan T, Wang H, et al. Automatic detection of multiple types of pneumonia: open dataset and a multi-scale attention network. Biomed Signal Process Control 2022; 73: 103415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attallah O. A computer-aided diagnostic framework for coronavirus diagnosis using texture-based radiomics images. Digit Heal 2022; 8: 205520762210925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Asnaoui K, Chawki Y, Idri A. Automated methods for detection and classification pneumonia based on X-ray images using deep learning. Cham: Springer, 2021, pp.257–284. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang D, Ren F, Li Y, et al. Pneumonia detection from chest X-ray images based on convolutional neural network. Electronics (Basel) 2021; 10: 1512. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajasenbagam T, Jeyanthi S, Pandian JA. Detection of pneumonia infection in lungs from chest X-ray images using deep convolutional neural network and content-based image retrieval techniques. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput 2021; 2021: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irede EL, Aworinde OR, Lekan OK, et al. Medical imaging: a critical review on X-ray imaging for the detection of infection. Biomed Mater Devices 2024; 2024: 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babukarthik RG, Chandramohan D, Tripathi D, et al. COVID-19 identification in chest X-ray images using intelligent multi-level classification scenario. Comput Electr Eng 2022; 104: 108405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdel Hady D, Abd El-Hafeez T. Utilizing machine learning to analyze trunk movement patterns in women with postpartum low back pain. Sci Rep 2024; 14: 18726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdel Hady DA, Mabrouk OM, Abd El-Hafeez T. Employing machine learning for enhanced abdominal fat prediction in cavitation post-treatment. Sci Rep 2024; 14: 11004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mabrouk OM, Hady DAA, Abd El-Hafeez T. Machine learning insights into scapular stabilization for alleviating shoulder pain in college students. Sci Rep 2024; 14: 28430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdel Hady DA, Abd El-Hafeez T. Revolutionizing core muscle analysis in female sexual dysfunction based on machine learning. Sci Rep 2024; 14: 4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eliwa EHI, El Koshiry AM, Abd El-Hafeez T, et al. Utilizing convolutional neural networks to classify monkeypox skin lesions. Sci Rep 2023; 13: 14495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel P. Chest X-ray (Covid-19 & Pneumonia) [Dataset]. Kaggle. Available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/prashant268/chest-X-ray-covid19-pneumonia (accessed 25 November 2024).

- 44.Loshchilov I, Hutter F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. ArXiv Prepr. Available at:http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05101 (2017).

- 45.Lanczos C. Trigonometric interpolation of empirical and analytical functions. J Math Phys 1938; 17: 123–199. [Google Scholar]