Abstract

Background:

Understanding of the mechanism of action of Baclofen as anticraving inalcohol dependence syndrome (ADS) is limited.

Aim:

Our study aimed to examine and compareearly changes in brain glutamate and GABA with Baclofen and Acamprosate among patients with alcohol dependence syndrome.

Material and Methods:

Forty patients with ADS were recruited with purposive sampling and were randomized into two groups using computer-generated randomization. At the end of detoxification (CIWA-Ar <10) brain glutamate and GABA were measured with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of the brain along with a measure of craving (PACS). Either Acamprosate or Baclofen was started. After 25 days of starting Baclofen or Acamprosate brain glutamate and brain GABA using 1H-MRS and PACS measures were repeat measured.

Results:

Both groups had shown comparable changes in brain glutamate (F = 0.01, P = 0.92, ηp2 = 0.00) and GABA (F = 0.29, 26 P = 0.59, ηp2 = 0.008) and craving (F = 0.08, P = 0.77, ηp2 = 0.002) over time. Baclofen and Acamprosate showed a differential relation with the clinical characteristics of participants.

Conclusion:

Our study has shown comparable changes in Glutamate and GABA during the early post-detoxification period both for baclofen and acamprosate. Effects of baclofen and acamprosate might correlate differently with the clinical profile of alcohol dependence syndrome which would help in choosing a particular anticraving medication.

Keywords: 1H-MRS, acamprosate, alcohol, anticraving, baclofen, GABA, glutamate

Alcohol use is a worldwide public health problem that adds to the global burden of disease including neuropsychiatric illnesses.[1,2] Craving is an important factor in alcohol use disorder in its maintenance and relapse.[3,4] In craving the Gama Amino Butyric acid (GABA)-ergic and Glutamatergic systems are dysregulated.[5] The Glutamatergic system particularly the NMDA receptors for craving and relapse has been implicated through a hypertrophic Glutamatergic system.[6,7] Alcohol acts on the GABAA receptor, increasing the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.[8] In chronic alcohol abuse, GABAA receptors are downregulated. After alcohol consumption is stopped, downregulated GABAA receptors have little effect on GABA neurotransmission resulting in physical withdrawal symptoms contributed by unopposed excitatory neurotransmission.[8] Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) is anatomically connected with limbic structures.[9,10] Studies describe ACC as a site to detect and monitor errors and suggest an appropriate form of action to be implemented by the motor system.[11,12] Both the dorsal and rostral areas of ACC are involved in substance use.[13,14] Acamprosate acts by inhibiting the Glutamatergic system, and by inhibiting the GABAergic system.[2,6] It is a positive allosteric modulator for GABAA receptors.[2] It interferes with the Glutamatergic system by acting as an NMDA receptor antagonist.[6] Baclofen is a presynaptic GABAB receptor agonist. The modulation of the GABAB receptor is what produces Baclofen’s range of therapeutic properties.[8] Preclinical studies have shown that baclofen-suppressed alcohol stimulated dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of rats.[8] Interestingly, GABAB receptors are in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) where mesolimbic dopamine neurons originate, both on the cell body of dopamine neurons and on the terminals of Glutamatergic afferent neurons. Their activation by GABAB receptor agonists may exert an inhibitory action on the dopamine neuron through which baclofen suppresses alcohol-stimulated dopamine release, hence craving.[2,8] Though both Acamprosate and Baclofen have been used widely as anticraving agents and interact with glutamatergic and GABA-ergic systems, head-to-head comparisons for their effects on glutamatergic and GABA-ergic systems have been inadequately studied.[15,16,17] To the best of our knowledge no study has compared changes in brain Glutamate and GABA between baclofen and acamprosate among patients with ADS. Hence, we aimed to examine and compare the changes in brain glutamate and GABA at ACC between patients of ADS receiving Baclofen and Acamprosate.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

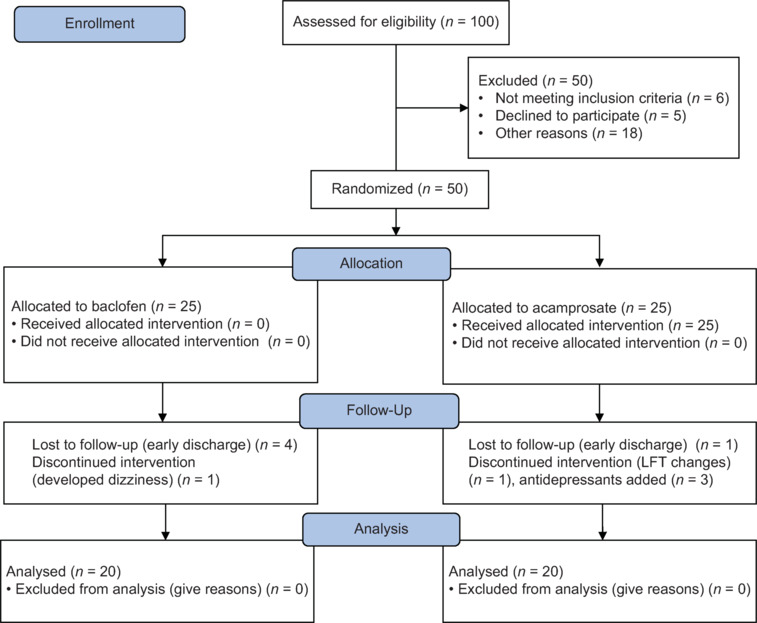

The present study was a hospital-based prospective study conducted at a psychiatric hospital in India. Approval was taken from the Institute Ethics Committee. The study was registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI) with registration number REF/2018/09/021671. Inpatients with 1) a diagnosis of per International Classification of Disease - 10th revision - Diagnostic Criteria for Research (WHO, 1993),[18] 2) aged between 18 and 50 years, 3) Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) score greater than or equal to 15,[19] and 4) Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment scale for Alcohol – Revised (CIWA-Ar) score lesser than 10[20] and 5) giving informed consent were selected for study. Inpatients with any comorbid substance dependence (except nicotine and caffeine) or any medical illness or any comorbid psychiatric illness, dementia, or psychotic disorder and who were on any psychotropic medication in the preceding 2 weeks and with metallic implants/parts in the body were excluded from the study. Data was collected between October 2017 and December 2019 including the start of recruitment and end of follow-up periods. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT flow chart of the study.

Figure 1.

Consort flow chart of the study

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using G*Power. Considering moderate effect size f to be 0.25, alpha set to be 0.05 and power to be 0.85, number of groups 2 and number of measurements to be 2, the sample size was calculated to be 38. Assuming a 20% dropout rate desired sample size for enrolment came out to be 46. Thus, each group had a desired sample size of 23.

Tools

The following tools were used in this study - 1) Socio-demographic and clinical data sheet to record demographic details and clinical characteristics of participants. 2) Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SAD-Q)[19] to measure the severity of alcohol dependence among participants, 3) Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS)[21] to record craving, 4) Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale, revised (CIWA-Ar)[20] to measure withdrawal severity among participants.

5) Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (1H-MRS)

Brain MRI scans were performed on a 3.0T magnetic resonance scanner (3T scanner (Ingenia, Philips made) with an 8-channel head coil. Each brain scan included anatomical images acquired with a 3D-T1 Fast Field Echo (3D-T1 FFE) sequence; time of echo (TE)/time of repetition (TR)/time of inversion (TI) =3.2/7/900 ms; flip angle (FA) =8°; FOV = 240 mm × 240 mm × 180 mm; matrix = 240 × 240) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) acquisition. Single-voxel 1H-MRS was performed using the PRESS sequence for glutamate with several scans (NS) of 160, TR of 1500 ms, and TE of 80 ms. The choice of TE was based on results from a previous study on the optimization of glutamate (Glu) detection.[22] MEGA-PRESS sequence, which is a J-edited PRESS-based method, was used for GABA as it is the most widely used edited method to quantify GABA at 3T.[23] MRS was preceded by an automatic pre-acquisition that included adjustment of the transmitter-receiver, optimization of the tilt angle for water suppression, and homogenization of the field for the selected volume of interest (VOI).

Voxel size was fixed for all patients and controls at 30 × 30 × 30 mm3. The voxel was positioned within the ACC using anatomical guidelines as a reference [Figure 2]. It was placed on midsagittal T1-weighted images, anterior to the genu of the corpus callosum, with the ventral edge aligned with the dorsal corner of the genu and centered on the midline of axial images. An unsuppressed water spectrum of the same voxel was also acquired for eddy current correction and reference purposes.

Figure 2.

Estimated marginal means of PACS

6) Baclofen and Acamprosate tablets- Both baclofen and acamprosate were supplied with regular hospital procurement in 20 mg and 333 mg tablets.

Procedure for data collection

Inpatients fulfilling inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study after obtaining informed consent. SADQ was administered at baseline and every day till it came to less than 10. Patients were detoxified with Benzodiazepines as per withdrawal assessment and institute protocol. Forty such patients fulfilling inclusion criteria were enrolled for the study after detoxification (CIWA-Ar < 10).

Enrolled patients were randomly allocated into two groups using computer-generated randomization.

Group I was started on oral baclofen. Baclofen was orally administered at a dose of 20 mg/day once daily for the first 3 days, with the dose increased to 40 mg/day (20 mg twice daily) for the remaining days.

Group II was started on oral acamprosate. Acamprosate doses given were 1998 mg daily (666 mg three times per day) for individuals over 60 kg. For those under 60 kg, the doses were 1332 mg daily.

For each enrolled patient the day on which CIWA-Ar became less than 10 was noted. On 4th day after initiation of either baclofen or acamprosate, PACS was administered, and brain Glutamate and GABA were assessed using 1H-MRS at ACC. Three days was given as a washout period of Benzodiazepines.[16]

PACS was re-administered, and brain Glutamate and GABA were repeat measured using 1H-MRS after 25 days of initiation of randomized treatment among participants.

Brain glutamate and GABA changes were the primary outcome measure whereas PACS change was the secondary outcome measure in our study.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using the statistical package of social science (SPSS) version 25 for Windows. (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) Descriptive statistics was used wherever applicable. After checking for normal distribution either Fischer exact t test or Mann-Whitney U test was applied between the groups for baseline comparisons. The overall effect of treatment over time between Baclofen and Acamprosate groups was analyzed with repeated measure analysis of variance. Greenhouse-Geisser correction for sphericity was applied. Treatment and time were used as between-group and within-subject factors. A level of significance of P < 0.05 (2-tailed) was taken to consider a result statistically significant. Spearman’s correlation was used to examine the correlation among various clinical and study variables.

RESULTS

Participants’ characteristics

Table S1 describes the participant’s characteristics. The mean age was 35.40 (6.86) and the mean age of onset was 23/68 (6.02) years. A mean SADQ of 31.25 (2.23) indicates they had severe alcohol dependence. Means PACS score of 21.60 (2.65) indicated that participants had experienced significant cravings at baseline. This means both baclofen and acamprosate groups were comparable except for the age of onset where the acamprosate group had a significantly earlier onset of dependence (Mann–Whitney U = 118.05, P = 0.02) [Table S2].

Table S1.

Participants’ characteristics (n=40)

| Characteristics | n (%)/Mean (SD) [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35.40 (6.86) [9] |

| Group | |

| Baclofen | 20 (50) |

| Acamprosate | 20 (50) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 28 (70) |

| Others | 12 (30) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 36 (90) |

| Unemployed | 4 (10) |

| Education in years | 10.75 (2.82) [2] |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 33 (82.5) |

| Unmarried | 7 (17.5) |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear | 17 (42.5) |

| Joint | 23 (57.5) |

| Habitat | |

| Rural | 24 (60) |

| Urban | 16 (40) |

| Monthly income (INR) | 17375.00 (12278.16) [17750] |

| Age of onset (years) | 23.68 (6.02) [8.25] |

| SADQ | 31.25 (2.23) [4.00] |

| PACS- baseline | 21.60 (2.65) [5] |

| CIWA-Ar baseline | 27.25 (2.81) [5] |

| Glutamate – baseline | -0.059 (0.131) [0.029] |

| GABA – baseline | 0.229 (0.127) [0.189] |

SD- standard deviation; INR-Indian National Rupees; IQR- Interquartile range; SADQ- severity of alcohol dependence questionnaire; PACS- Penn Alcohol Craving Scale Questionnaire

Table S2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics comparison between baclofen and acamprosate groups at baseline (n=40)

| Characteristics | Baclofen n/Mean (SD) | Acamprosate n/Mean (SD) | X2/t/U | Z/df | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.35 (6.96) | 34.45 (6.80) | 0.87 | 38 | 0.38 |

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu | 13 | 15 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.73 |

| Others | 7 | 5 | |||

| Occupation | |||||

| Employed | 19 | 17 | 0.27b | 1 | 0.59 |

| Unemployed | 1 | 3 | |||

| Education in years | 10.20 (3.33) | 11.30 (2.15) | 176.00U | -0.67 | 0.51 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 15 | 18 | 0.69b | 1 | 0.40 |

| Unmarried | 5 | 2 | |||

| Family type | |||||

| Nuclear | 9 | 8 | 0.10 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Joint | 11 | 12 | |||

| Habitat | |||||

| Rural | 12 | 12 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Urban | 8 | 8 | |||

| Monthly income (INR) | 16900.00 (11106.66) | 17850.00 (13623.79) | 197.50U | -0.06 | 0.95 |

| Age of onset (years) | 25.90 (6.49) | 21.45 (4.67) | 118.50U | -2.21 | 0.02* |

| SADQ | 31.30 (2.25) | 31.20 (2.28) | 0.13 | 38 | 0.89 |

| PACS- baseline | 21.55 (2.70) | 21.65 (2.68) | -0.11 | 38 | 0.90 |

| CIWA-Ar baseline | 26.95 (2.76) | 27.55 (2.91) | -0.66 | 38 | 0.50 |

| Glutamate – baseline | -0.049 (0.105) | -0.070 (0.155) | 147.00U | -1.43 | 0.15 |

| GABA – baseline | 0.227 (0.134) | 0.232 (0.124) | 192.00U | -0.21 | 0.84 |

U- Mann Whitney U; df=degree of freedom; SD- standard deviation; INR-Indian National Rupees; IQR- Interquartile range; SADQ- severity of alcohol dependence questionnaire; PACS- Penn Alcohol Craving Scale Questionnaire

PACS, brain Glutamate, and brain GABA levels change over time between Baclofen and Acamprosate groups

Repeat measure ANOVA for brain glutamate, brain GABA, and PACS have been shown from Figures 2-4. Both groups had shown comparable changes over time in PACS (F = 0.08, P = 0.77, ηp2 = 0.002) [Figure 2], brain glutamate (F = 0.01, P = 0.92, ηp2 = 0.000) [Figure 3] and GABA (F = 0.29, P = 0.59, ηp2 = 0.008) [Figure 4]. Noteworthy for GABA is that while the acamprosate group showed an increase in GABA, the baclofen group showed a decrease in the same.

Figure 4.

Estimated marginal means of GABA

Figure 3.

Estimated marginal means of Glutamate

Correlations

Baclofen group

Both baseline GABA and duration of alcohol dependence were positively correlated with GABA level after 25 days of treatment in the baclofen group while baseline Glutamate was negatively correlated with glutamate level change. Age of onset of dependence, SADQ, PACS baseline CIWA-Ar baseline, and GABA baseline were negatively correlated with GABA change in the baclofen group.

Acamprosate group

Baseline withdrawal severity was positively correlated with Glutamate change, but baseline glutamate level was negatively correlated with the same. Baseline glutamate and GABA were positively and negatively respectively correlated with GABA change in the acamprosate group.

DISCUSSION

Participants’ characteristics

In the present study, all three groups were comparable in terms of age, education, religion, occupation, income, marital status, family type, and habitat. The mean age was consistent with studies done by Mishra et al.[24] in the Indian population. The majority of them were Hindu which might parallel the demographic characteristics of India. This was also consistent with the lesser alcohol consumption in the other religions, mainly Islam and Jainism.[25] Though lower education has a higher risk of alcohol dependence among Asians participants in our study were educated.[26] The patients in our study were mostly employed which was consistent with previous epidemiological studies.[24] The majority of patients were married. This was consistent with a previous study.[24] A higher number of married patients can be due to marriage being a phase of transition which may play as a stressor, hence aggravating factor for alcohol use.[27]

Brain glutamate and GABA at ACC changes over time between groups

Both glutamate and GABA had shown comparable changes between baclofen and acamprosate groups [Table 1]. This indicates a similar early effect on glutamate and GABA by both baclofen and acamprosate. This supports the promise of baclofen as an anticraving agent like acamprosate which is an approved anticraving medication for alcohol dependence.

Table 1.

Spearman’s correlations in both groups (n=40)

| Glutamate after 25 days |

GABA after 25 days |

Glutamate change |

GABA change |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baclofen | Acamprosate | Baclofen | Acamprosate | Baclofen | Acamprosate | Baclofen | Acamprosate | |

| Age | 0.28 | −0.24 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.12 | −0.14 | −0.04 |

| Age of onset | 0.18 | −0.16 | −0.36 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.22 | −0.47* | 0.22 |

| Duration of dependence | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.56* | −0.07 | 0.26 | −0.01 | 0.28 | −0.15 |

| SADQ | −0.04 | −0.19 | −0.36 | −0.007 | −0.18 | 0.28 | −.47* | −0.24 |

| PACS baseline | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.31 | −0.16 | −0.13 | 0.42 | −.60** | −0.36 |

| CIWA-Ar baseline | −0.13 | 0.10 | −0.22 | −0.22 | −0.23 | 0.47* | −.46* | −0.35 |

| Glutamate baseline | −0.03 | 0.12 | −0.20 | 0.07 | −0.62** | −0.60** | 0.13 | 0.53* |

| GABA baseline | −0.18 | −0.34 | 0.45* | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.282 | −0.47* | −0.59** |

SAD-Q=Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire; PACS=Penn Alcohol Craving Scale; and CIWA-Ar=Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment- Alcohol Revised. *P<0.05. **P<0.01

Correlation among clinical variables, glutamate and GABA in both groups

The present study tried to analyze the relationships between Glutamate and GABA levels at ACC after 25 days of treatment with the clinical characteristics of participants.

Baclofen

Age of onset was significantly negatively correlated with GABA change in the baclofen group, which means those who started having alcohol dependence from an earlier age will show greater changes in their GABA levels at ACC and vice-versa. Alcohol’s ability to potentiate the GABAergic system in healthy young adults with alcohol dependence has also been seen in previous studies.[28] Whether Baclofen is more effective in reducing craving among ADS patients with early age of onset warrants further investigation. Duration of dependence was positively correlated with GABA after 25 days of treatment. Chronic ethanol intake might differentially alter GABA levels causing altered levels in ACC when exposed during early age as compared to adulthood.[29] This might also be due to an already overactive GABAergic system before they went through detoxification. Baseline Glutamate and GABA were negatively correlated with changes in Glutamate and GABA, respectively. Alcohol dependence has been recently shown to be due to abnormal GABA tone and more changes seen in these neurotransmitters with less baseline levels could be due to normalization of these abnormal glutamate and GABA tones.[30] SAD-Q, PACS baseline, and CIWA-Ar baseline were negatively correlated with GABA change. Patient with more dependence, craving, and withdrawal will show fewer changes in their GABA levels with baclofen. This might raise speculation about whether baclofen would be more effective in less severe dependence or vice-versa. In line with this anxiolytic effects of baclofen have been found in alcohol dependence and the same has been related to its anticraving effects.[31,32,33]

Acamprosate

Baseline Glutamate and GABA were negatively correlated with changes at Glutamate and GABA respectively like what was shown in the Baclofen group. As discussed earlier, alcohol addiction is due to abnormal GABA tones, and more changes seen in these neurotransmitters with lower baseline levels could be due to the normalization of these abnormal glutamate and GABA tones.[30] Baseline glutamate was positively correlated with GABA change. This is by the study according to which chronic ethanol exposure caused up-regulation of NMDA receptor function causing increasing glutamate levels and down-regulates GABAA receptor function causing a decrease in GABA at the cingulate cortex and amygdala.[34,35,36]

CIWA-Ar baseline was positively correlated with glutamate change. So, it might be speculated that acamprosate would be more effective than baclofen in more severe alcohol dependence. A hyperglutamatergic state has been implicated in the hyperexcitability of alcohol withdrawal.[37,38,39] The ability of acamprosate to suppress central glutamate levels might therefore be responsible for suppressing acute alcohol withdrawal symptoms leading to more changes in the withdrawal rating scale.[40,41]

Our study suffered a few limitations. The sample size was small. The duration of treatment with baclofen and acamprosate might be longer to examine late changes of central glutamate and GABA. Another group with a higher dosage of baclofen could have been included for better understanding.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study has shown comparable changes in Glutamate and GABA at anterior cingulate cortex during early post-detoxification period both for baclofen and acamprosate. Our study also indicated the effect of baclofen and acamprosate might corelate differently with clinical profile of alcohol dependence syndrome which would help in choosing a particular anticraving medications.

Author Contributions*

SK, CRJK and PD conceptualized the work. AK and PD collected data. AK, SK, and PD drafted the manuscript. All authors except CRJK have approved the final manuscript. [* As CRJK is deceased, he was not able to review the final manuscript].

Ethical statement

Study was approved by Ethics committee of Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, Jharkhand on 25.07.2018.

Data availability statement

Data can be made available on reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Dr Christoday Raja Jayant Khess, Senior professor of Psychiatry, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi for his contribution and suggestion while conducting the study. But for his untimely death he was not able to review the final manuscript otherwise he would have been a co author of the article.

Funding Statement

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kufahl PR, Watterson LR, Olive MF. The development of acamprosate as a treatment against alcohol relapse. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2014;9:1355–69. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2014.960840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Addolorato G, Leggio L, Abenavoli L, Gasbarrini G, Alcoholism Treatment Study Group Neurobiochemical and clinical aspects of craving in alcohol addiction: A review. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1209–24. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anton RF. What is craving?: Models and implications for treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:165–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spanagel R. Alcohol addiction research: from animal models to clinics. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:507–18. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason GF, Petrakis IL, de Graaf RA, Gueorguieva R, Guidone E, Coric V, et al. Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels and the recovery from ethanol dependence: Preliminary evidence of modification by cigarette smoking. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2008;363:3125–35. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter LP, Griffiths RR. Principles of laboratory assessment of drug abuse liability and implications for clinical development. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(Suppl 1):S14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: Neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer J, Pedersen A, Scherbaum N, Bening J, Patschke J, Kugel H, et al. Craving in alcohol-dependent patients after detoxification is related to glutamatergic dysfunction in the nucleus accumbens and the anterior cingulate cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1401–8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botvinick M, Braver T. Motivation and cognitive control: From behavior to neural mechanism. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:83–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss AR, Gillies MJ, Philiastides MG, Apps MA, Whittington MA, FitzGerald JJ, et al. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortices differentially lateralize prediction errors and outcome valence in a decision-making task. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;12:203. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fein G, Di Sclafani V, Cardenas VA, Goldmann H, Tolou-Shams M, Meyerhoff DJ. Cortical gray matter loss in treatment-naive alcohol dependent individuals. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:558–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fava NM, Trucco EM, Martz ME, Cope LM, Jester JM, Zucker RA, et al. Childhood adversity, externalizing behavior, and substance use in adolescence: Mediating effects of anterior cingulate cortex activation during inhibitory errors. Dev Psychopathol. 2019;31:1439–50. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolo N, Nédélec JF, Muzet M, De Witte P, Dahchour A, Durbin P, et al. Central effects of acamprosate: Part 2. Acamprosate modifies the brain in-vivo proton magnetic resonance spectrum in healthy young male volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 1998;82:115–27. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umhau JC, Momenan R, Schwandt ML, Singley E, Lifshitz M, Doty L, et al. Effect of acamprosate on magnetic resonance spectroscopy measures of central glutamate in detoxified alcohol-dependent individuals: A randomized controlled experimental medicine study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1069–77. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morley KC, Lagopoulos J, Logge W, Chitty K, Baillie A, Haber PS. Neurometabolite levels in alcohol use disorder patients during baclofen treatment and prediction of relapse to heavy drinking. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:412. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Geneva: WHO; 1993. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Description and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stockwell T, Murphy D, Hodgson R. The severity of alcohol dependence questionnaire: Its use, reliability and validity. Br J Addict. 1983;78:145–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1983.tb05502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: The revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar) Br J Addict. 1989;84:1353–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric properties of the Penn alcohol craving scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1289–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schubert F, Gallinat J, Seifert F, Rinneberg H. Glutamate concentrations in human brain using single voxel proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3 Tesla. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1762–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullins PG, Chen H, Xu J, Caprihan A, Gasparovic C. Comparative reliability of proton spectroscopy techniques designed to improve detection of J-coupled metabolites. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:964–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra BR, Nizamie SH, Das B, Praharaj SK. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in alcohol dependence: A sham-controlled study. Addiction. 2010;105:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundaram KR, Mohan D, Advani GB, Sharma HK, Bajaj JS. Alcohol abuse in a rural community in India. Part I: Epidemiological study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1984;14:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(84)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilman SE, Breslau J, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Subramanian SV, Zaslavsky AM. Education and race-ethnicity differences in the lifetime risk of alcohol dependence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:224–30. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.059022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLeod JD. Spouse concordance for alcohol dependence and heavy drinking: Evidence from a community sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1146–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gómez AP, Scoppetta O, Alarcón LF. Age at onset of alcohol consumption and risk of problematic alcohol and psychoactive substance use in adulthood in the general population in Colombia. J Int Drug, Alcohol Tobacco Res. 2011;1:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papadeas S, Grobin AC, Morrow AL. Chronic ethanol consumption differentially alters GABAA receptor α1 and α4 subunit peptide expression and GABAA receptor-mediated 36Cl − Uptake in mesocorticolimbic regions of rat brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1270–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Beaurepaire R. A review of the potential mechanisms of action of baclofen in alcohol use disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:506. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krupitsky EM, Burakov AM, Ivanov VB, Krandashova GF, Lapin IP, Grinenko AJ, et al. Baclofen administration for the treatment of affective disorders in alcoholic patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993;33:157–63. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90057-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Addolorato G, Caputo F, Capristo E, Domenicali M, Bernardi M, Janiri L, et al. Baclofen efficacy in reducing alcohol craving and intake: A preliminary double-blind randomized controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:504–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.5.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta M, Verma P, Rastogi R, Arora S, Elwadhi D. Randomized open-label trial of baclofen for relapse prevention in alcohol dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:324–31. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1240797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz B, Fendt M, Gasparini F, Limgenhohl K, Kuhn R, Koch M. The metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist MPEP blocks fear conditioning in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker DL, Davis M. The role of amygdala glutamate receptors in fear learning, fear-potentiated startle, and extinction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:379–92. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu W, Bie B, Pan ZZ. Involvement of non-NMDA glutamate receptors in central amygdala in synaptic actions of ethanol and ethanol-induced reward behavior. J Neurosci. 2007;27:289–98. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3912-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Witte P, Pinto E, Ansseau M, Verbanck P. Alcohol and withdrawal: From animal research to clinical issues. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:189–97. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spanagel R. Alcoholism: A systems approach from molecular physiology to addictive behavior. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:649–705. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fadda F, Rossetti ZL. Chronic ethanol consumption: From neuroadaptation to neurodegeneration. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:385–431. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Harris RA, Arends MA, Koob GF. Alcohol-related genes: Contributions from studies with genetically engineered mice. Addict Biol. 2006;11:195–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spanagel R, Pendyala G, Abarca C, Zghoul T, Sanchis-Segura C, Magnone MC, et al. The clock gene Per2 influences the glutamatergic system and modulates alcohol consumption. Nat Med. 2005;11:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available on reasonable request.