Abstract

Cardioids are 3D self‐organized heart organoids directly derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) aggregates. The growth and culture of cardioids is either conducted in suspension culture or heavily relies on Matrigel encapsulation. Despite the significant advancements in cardioid technology, reproducibility remains a major challenge, limiting their widespread use in both basic research and translational applications. Here, for the first time, we employed synthetic, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)‐degradable polyethylene glycol (PEG)‐based hydrogels to define the effect of mechanical and biochemical cues on cardioid development. Successful cardiac differentiation is demonstrated in all the hydrogel conditions, while cardioid cultured in optimized PEG hydrogel (3 wt.% PEG‐2mM RGD) underwent similar morphological development and comparable tissue functions to those cultured in Matrigel. Matrix stiffness and cell adhesion motif play a critical role in cardioid development, nascent chamber formation, contractile physiology, and endothelial cell gene enrichment. More importantly, synthetic hydrogel improved the reproducibility in cardioid properties compared to traditional suspension culture and Matrigel encapsulation. Therefore, PEG‐based hydrogel has the potential to be used as an alternative to Matrigel for human cardioid culture in a variety of clinical applications including cell therapy and tissue engineering.

Keywords: cardioids, human induced pluripotent stem cells, mechanobiology, organoids, synthetic hydrogel

Synthetic matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)‐degradable polyethylene glycol (PEG)‐based hydrogels are developed to investigate the influence of mechanical and biochemical cues on cardioid development. Matrix stiffness and cell adhesion motifs significantly regulate cardioid formation, chamber morphogenesis, contractile function, and cardioid transcriptome. Notably, the synthetic hydrogel enhances the reproducibility of cardioid properties compared to traditional approach based on Matrigel‐encapsulation.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of death globally.[ 1 ] Advancing 3D human cardiac in vitro models is crucial for understanding CVDs and developing new therapeutic strategies. Cardioids, derived directly from human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) aggregates, are typically generated and cultured in round‐bottom ultralow attachment plates.[ 2 , 3 ] These self‐organized structures recapitulate key aspects of early heart development and function, including nascent chamber formation—an advantage over other engineered heart models.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ] However, most cardioid generation methods lack biomaterial scaffolds or external mechanical cues to direct differentiation and tissue development, limiting the reproducibility of organoid formation. To date, only one study has reported the successful generation of cardioids by embedding hPSC aggregates in Matrigel, a matrix extracted from Engelbreth–Holm–Swarm mouse sarcoma.[ 3 ] However, Matrigel has been reported with high batch‐to‐batch variability and the presence of xenogeneic contaminants, leading to inconsistent experimental outcomes and poor reproducibility across studies.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] Thus, there is a growing need to develop alternative synthetic biomaterials to support robust, reproducible cardioid development for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is widely used synthetic biomaterial for organoid culture, supporting the development of intestinal, neural tube, liver, and cerebellar organoids.[ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] RGD‐functionalized PEG hydrogels with an elastic modulus below 100 Pa have shown comparable organoid viability to Matrigel.[ 13 ] Beyond serving as a Matrigel alternative, synthetic hydrogels offer a more precisely defined biochemical and biophysical niche for modulating organoid growth and function.[ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] For example, a stiff PEG‐based matrix maintained the survival and proliferation of undifferentiated intestinal stem cells, whereas a soft matrix promoted their differentiation into functional intestinal organoids.[ 20 ] Additionally, functionalizing 8‐arm PEG hydrogels with integrin‐binding ligands such as the collagen‐mimicking peptide GFOGER has been shown to support the growth and formation of human intestinal and endometrial organoids.[ 26 ] These findings highlight the tunable properties of synthetic hydrogels, which can be leveraged to enhance the reproducibility and functionality of organoid systems. However, only a few studies have utilized PEG hydrogels and pre‐differentiated iPSC‐derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC‐CMs) to generate engineered heart tissues,[ 27 , 28 , 29 ] and no study has yet reported the development and culture of cardioids in synthetic hydrogels.

In this study, we developed a tunable, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)‐degradable PEG‐based hydrogel system for cardioid culture. We systematically investigated how matrix cues, including RGD functionalization and mechanical properties, influence cardioid formation and function. Our findings revealed significant differences in morphology, contractile function, and transcriptomic profiles among cardioids cultured in hydrogels with varying properties. Notably, RGD incorporation in PEG hydrogels significantly enriched gene expression related to heart and vascular development compared to cardioids grown in a scaffold‐free system or PEG hydrogels without RGD. More importantly, we demonstrated distinct advantages of synthetic hydrogels over scaffold‐free and Matrigel‐based methods, particularly in terms of reproducibility. The well‐defined synthetic hydrogel system improved organoid consistency, establishing it as a reliable alternative to animal‐derived matrices like Matrigel. This enhanced reproducibility not only strengthens experimental reliability but also expands the potential applications of cardioids in both basic research and translational studies.

2. Results

2.1. PEG Hydrogel Characterization

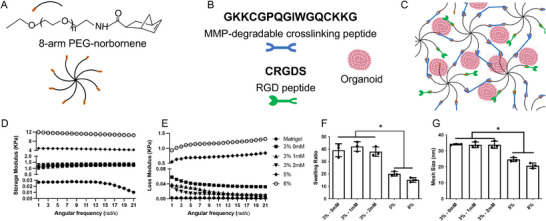

PEG hydrogels were formed using norbornene‐functionalized PEG macromers and a bis‐cysteine MMP degradable peptide crosslinker containing the sequence of GPQGIWGQ, which can be cleaved by cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells secreted MMPs (Figure 1A–C).[ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ] Hydrogels were made at three different concentrations (3, 5, and 8 wt.%) with tunable elastic moduli as well as cell‐binding peptide RGD at a concentration of 1 and 2 mM. Rheological analysis of these formulations demonstrated that initial polymer concentration had a significant effect on hydrogel stiffness. The storage modulus (G′) of 3 wt.% hydrogels remained consistently ≈1.3 kPa with or without RGD. The modulus increased to 4.7 and 11.9 kPa in 5 and 8 wt.% hydrogels, respectively. In comparison, Matrigel has a storage modulus of ≈25 Pa, which is significantly lower than all the PEG hydrogel groups (Figure 1D). We tried to further reduce the hydrogel stiffness by decreasing the PEG concentration to 2 wt.%, but the derived hydrogels were too soft to handle. The loss modulus (G″) did not change obviously during a frequency sweep, indicating that these hydrogels were primarily elastic (Figure 1E). In addition, the swelling ratio of the hydrogels increased with the decrease of PEG concentrations (Figure 1F). Mesh sizes, which are an estimate of the distance between polymer chains, also showed a similar trend as the swelling ratio. Soft hydrogels showed a higher swelling ratio and a larger mesh size (Figure 1G), suggesting better diffusive properties than stiffer hydrogels.[ 34 ]

Figure 1.

PEG hydrogels with synthetic peptides replicated key ECM cues. A) Schematic representation of hydrogel composition using 8‐arm PEG‐norbornene macromers. B) Hydrogel network incorporating MMP‐degradable peptide (blue) as crosslinkers and RGD peptide (green) for cell adhesion. C) Hydrogel polymerization process using the photo‐initiator LAP and long‐wave ultraviolet (UV) light (≈5 mW cm− 2, 365 nm, 3 min) for cardioid encapsulation. D) Storage modulus and E) loss modulus of PEG‐based hydrogels. F) Swelling ratio and G) mesh size calculations of the hydrogels. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA with Tukey post‐hoc correction (*p < 0.05, n = 3).

To validate the reproducibility of the PEG hydrogel, we fabricated new hydrogels and measured their storage modulus using a rheometer. Comparing the rheological results from newly fabricated hydrogels to the ones that were fabricated before, we found no significant difference in modulus between hydrogels fabricated at different batches, demonstrating consistent repeatability and reproducibility (Figure S2A,B, Supporting Information). Moreover, we assessed the efficiency of the 8‐arm PEG norbornene and dithiol peptide reaction using colorimetric analysis of unreacted thiols with Ellman's reagent. Results showed that 97.07% of thiol (‐SH) groups were consumed during gel formation, indicating high reaction efficiency (Figure S2B, Supporting Information). This high conversion rate ensures consistent and reproducible hydrogel fabrication.

2.2. Hydrogel Stiffness Affects Cardioid Viability and Morphology

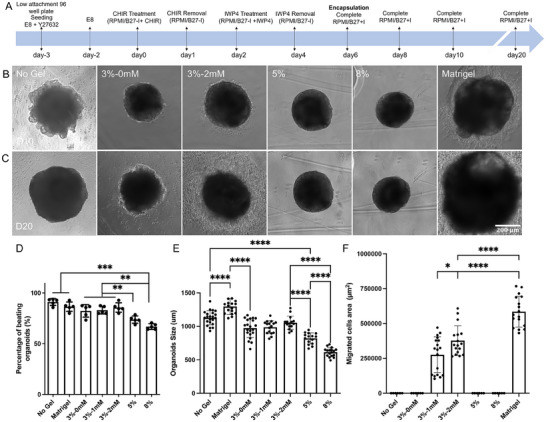

To generate cardioids, hiPSC aggregates were first formed via self‐assembly of hiPSCs in round bottom ultra‐low‐attachment 96‐well plates (Figure S3A–C, Supporting Information). hiPSC aggregates maintained their pluripotency, as confirmed by positive immunofluorescence of OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 (Figure S4A, Supporting Information). We found that cell seeding density significantly influenced aggregates size (Figure S3D, Supporting Information). The aggregates were cultured in E8 medium for 2 days before differentiation into cardioids following our established protocols (Figure 2A).[ 35 , 36 ] During differentiation, mesoderm marker BRA was positively expressed after CHIR99021 treatment (Day 1), while NANOG and OCT4 were downregulated (Figure S4B, Supporting Information). By Day 8, cardioids exhibited positive staining for cardiac progenitor marker ISL1, followed by NKX2.5 and GATA4 expression on Day 10, confirming efficient cardiac differentiation (Figure S4C, Supporting Information). By day 16, beating behaviors was recorded and analyzed, revealing no significant differences in beating rate (Figure S3E, Supporting Information). However, a higher percentage of beating organoids was observed in larger aggregates (10 000 cells per well) compared to those formed with 3000 or 5000 cells per well (Figure S3F, Supporting Information). Based on these findings, a seeding density of 10 000 cells per well was selected for subsequent studies.

Figure 2.

Impact of hydrogel properties on cardioid viability and growth behaviors. A) Timeline of cardioid encapsulation and differentiation. Phase‐contrast images of cardioids encapsulated in different hydrogels on B) day 10 and C) day 20. D) Percentage of beating organoids under different culture conditions, indicating cardiac differentiation efficacy. Comparison of E) organoid size and F) outward cell migration across different culture conditions. Matrigel resulted in the largest organoids and highest cell migration, while increasing hydrogel stiffness reduced organoid size and differentiation efficiency. Statistical significance was determined using one‐way ANOVA with Tukey post‐hoc correction (**p < 0.01, n ≥ 15).

To evaluate the effect of hydrogel encapsulation on cardioid viability, LIVE/DEAD assay was performed 3 days post‐encapsulation. Cardioids embedded in 3 wt.% PEG hydrogels maintained high viability, comparable to those encapsulated in Matrigel. In contrast, organoids encapsulated in 5 or 8 wt.% hydrogels exhibited a reduced viability as gel stiffness increased (Figure S5, Supporting Information). Hydrogel stiffness also influenced cardioid morphology and growth behavior (Figure S6A, Supporting Information). Organoid size was restricted by the surrounding PEG hydrogel network, affecting overall growth (Figure 2B,C; Figure S6B, Supporting Information) and the percentage of beating organoids by Day 20 (Figure 2D). Organoids in stiffer hydrogels (8 wt.%) were rounder and smaller (≈610 µm) compared to those in softer hydrogels (3 wt.%, ≈970 µm) (Figure 2E). In contrast, Matrigel encapsulation had minimal impact on organoid growth (≈1290 µm), likely due to its ultra‐low mechanical stiffness and abundance of growth factors. Cells migrated out of the organoids in RGD‐incorporated hydrogels (Figure 2B,C; Figure S6A, Supporting Information), with the migration area increasing from ≈0.3 mm2 at 1 mM RGD to ≈0.4 mm2 at 2 mM RGD by Day 20. In contrast, no cell migration was observed from the cardioids generated in hydrogels without RGD or suspension culture. Matrigel‐encapsulated cardioids exhibited the fastest migration rate, with migration initiating by Day 8 and reaching the largest migrated cell area (≈0.6 mm2) by Day 20 (Figure 2F).

2.3. Hydrogels Regulate Nascent Chamber Development and Contractile Physiology of Cardioids

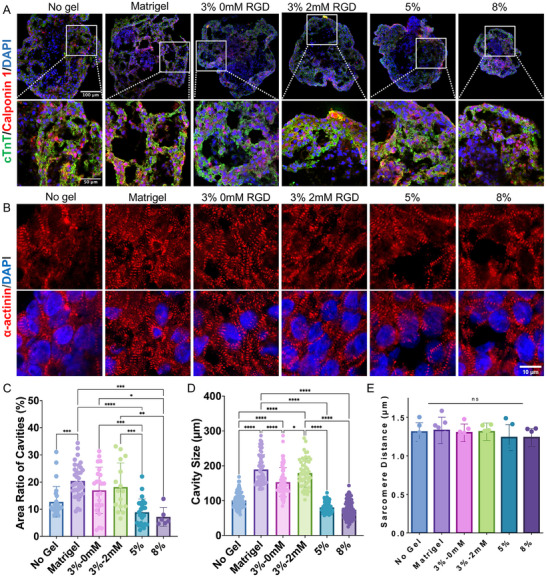

To confirm successful cardiac differentiation, immunostaining was performed for cardiomyocyte‐specific markers, cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and sarcomere α‐actinin (ACTN2), as well as the smooth muscle marker calponin 1 (Figure 3A,B). Positive expression of these markers across all groups confirmed that each hydrogel condition, along with suspension culture, effectively supported cardiac differentiation. Additionally, cavities were observed forming within the cardioids, indicating nascent heart chamber development (Figure 3A). The cavity‐to‐organoid area ratio decreased as hydrogel stiffness increased (Figure 3C). Cardioids cultured in 3 wt.% PEG hydrogels (≈17%), with or without RGD, exhibited a cavity area ratio comparable to Matrigel (20%), both of which were higher than that in suspension culture (13%). A similar trend was observed in average cavity size, with cardioids in stiffer hydrogels (≈74 µm in 8 wt.% PEG) forming significantly smaller cavities than those in Matrigel (≈190 µm) and RGD‐incorporated 3 wt.% hydrogels (≈180 µm) (Figure 3D). Furthermore, sarcomere spacing was quantified across different culture conditions, but no significant differences were observed between groups (Figure 3E). These results suggest that both matrix mechanical properties and cell adhesive motifs influence nascent chamber formation in cardioids, highlighting the critical role of hydrogel encapsulation in enhancing structural development over traditional suspension culture.

Figure 3.

Impact of hydrogel properties on chamber formation within cardioids. A) Immunostaining of cardiomyocyte‐specific protein cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and smooth muscle marker calponin 1. B) Immunostaining of sarcomere α‐actinin to demonstrate sarcomere structures of cardioids. C) Quantification of the cavity area ratio and D) cavity size across different culture conditions. E) Measurement of sarcomere distance in cardioids. Cardioids cultured in 3 wt.% PEG‐2 mM RGD hydrogels exhibited comparable cavity formation to those in Matrigel, both of which were higher than in other conditions. Statistical significance was determined using one‐way ANOVA with Tukey post‐hoc correction (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns = not significant, n ≥ 15).

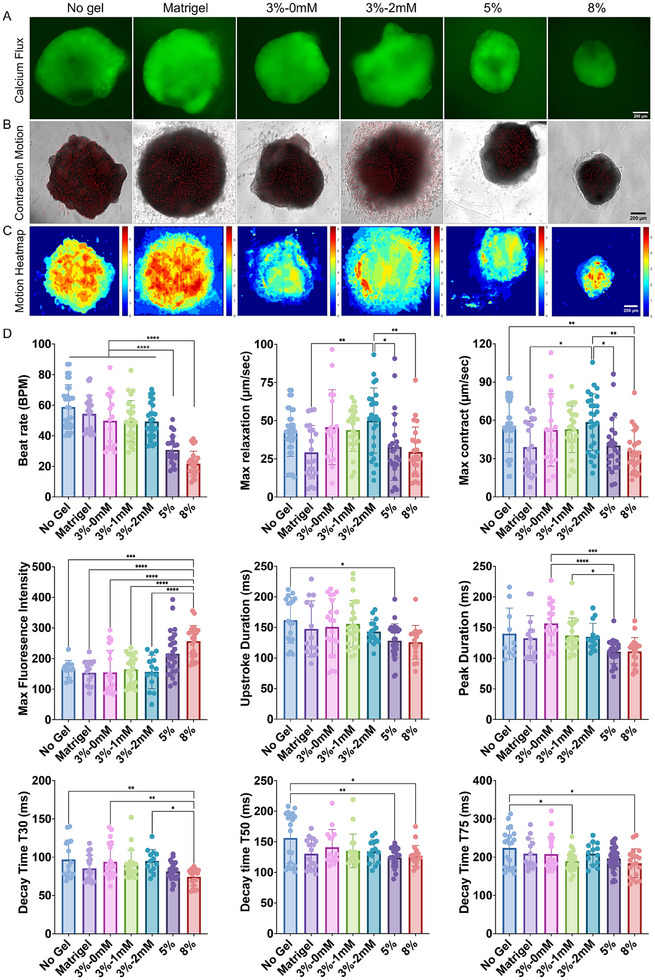

To characterize contraction physiology, we conducted an integrated assessment of GCaMP6f calcium flux and cardiac contraction motion (Figure 4A–C and Movies S1–S6, Supporting Information). Cardioids cultured in stiff hydrogels (8 wt.%) exhibited a significant reduction in beat rate, maximum relaxation velocity, and maximum contraction velocity compared to those cultured in soft hydrogels or suspension (Figure 4D). This finding aligns with previous studies demonstrating that cardiomyocytes cultured on stiff substrates show reduced beat rates and decreased contraction and relaxation velocities.[ 37 , 38 , 39 ] Increased hydrogel stiffness also led to higher maximum calcium flux and a reduction in both upstroke time (T0) and peak duration, suggesting that stiffness modulates intracellular calcium release in cardiomyocytes (Figure 4D). Similarly, calcium decay time values (T30, T50, and T75) were reduced in organoids cultured in hydrogels compared to those without hydrogel encapsulation, further emphasizing the influence of biomechanical cues from stiff hydrogels on calcium flux. These observations are consistent with studies showing that stiff substrates lead to shorter calcium handling times in cardiac cells, potentially contributing to arrhythmias.[ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ] Overall, these findings suggest that softer hydrogels (e.g., 3 wt.%) are more favorable for proper cardioid differentiation and function.

Figure 4.

Impact of hydrogel properties on cardiac contractile function. A) Fluorescent calcium flux imaging and B) brightfield video‐based contraction motion analysis of cardioids. C) Motion heatmaps visualizing contraction dynamics across different hydrogel conditions. D) Quantitative analysis of contractile function, including beat rate, maximum relaxation and contraction velocities, peak fluorescence intensity, upstroke duration (T0), peak duration, and decay times (T30, T50, and T75). Statistical significance was determined using one‐way ANOVA with Tukey post‐hoc correction (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, n ≥ 15).

2.4. Hydrogel Encapsulation Leads to High Reproducibility in Cardioids

To further assess the reproducibility of cardioid formation under different culture conditions, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV) for key parameters, including organoid size, cavity dimensions, sarcomere length, contractile function, and calcium transients (Table S2, Supporting Information). We found that the 3% PEG 2mM‐RGD hydrogel exhibited the lowest average CV value among all culture conditions, indicating the highest reproducibility in cardioid development and function. Specifically, compared to Matrigel encapsulation, the 3% PEG 2mM‐RGD hydrogel demonstrated lower CV values for organoid size, calcium peak time, and contraction velocity, which are critical physiological parameters for ensuring consistent cardioid production and culture. Our findings align with a previous study that used gastrointestinal tissue‐derived extracellular matrix hydrogels as an alternative to Matrigel for gastric organoid culture, reporting significantly lower CV in organoid size compared to Matrigel.[ 45 ] We also highlight the importance of incorporating RGD in PEG hydrogel to achieve consistent cardioid development. We found that in the absence of RGD, the bioinert PEG hydrogel provides minimal cell‐adhesive interactions, which leads to variability in cardioid growth. The incorporation of RGD introduces integrin‐binding sites that facilitate more uniform cardioid‐matrix interactions, thereby stabilizing encapsulated cardioids and reducing CV. Synthetic PEG hydrogels provide a more controlled and customizable environment, allowing for precise modulation of both biochemical and mechanical properties. This level of control leads to more reproducible outcomes in organoid development.

2.5. Transcriptomic Comparison for the Cardioids Under Different Culture Conditions

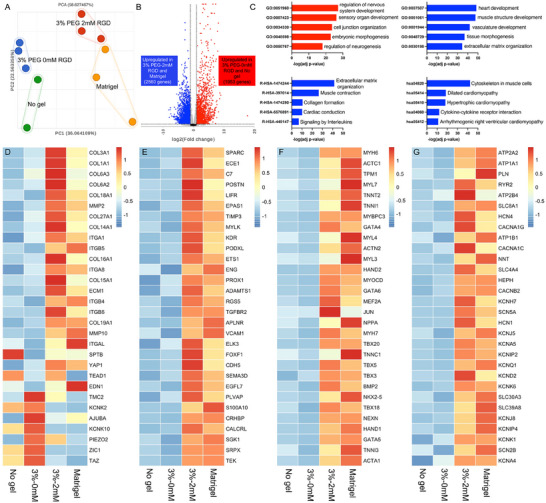

Based on previous results, we observed that softer hydrogels better support cardioid development, promoting more robust chamber formation and enhanced contractile function. As a result, we selected softer hydrogels for transcriptomic comparisons with traditional culture methods, including Matrigel and no‐gel suspension cultures. Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA‐seq) was performed on cardioids generated under various conditions: PEG‐encapsulated cardioids (3 wt.% with and without 2 mM RGD), Matrigel‐encapsulated cardioids, and no‐gel suspension‐cultured cardioids. After filtering out low‐quality reads, ≈18 120 genes were used for downstream analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed distinct separation between conditions. Cardioids from 3 wt.% PEG hydrogels without RGD were closely related to those from no‐gel suspension culture, while cardioids cultured in 3 wt.% PEG hydrogels with 2 mMm RGD were more similar to those encapsulated in Matrigel. Notably, the sample distribution of cardioid replicates from the PEG hydrogel groups was more concentrated in the PCA plot compared to the Matrigel and no‐gel groups, suggesting that cardioids generated with PEG hydrogels exhibit greater consistency in their transcriptomic profiles than those grown using traditional methods (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Transcriptomic profile of cardioids across different culture conditions. A) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing distinct clustering of cardioids cultured in 3 wt.% PEG hydrogels (with and without 2 mM RGD), Matrigel, and suspension culture (No Gel). B) Volcano plot depicting differentially expressed genes between Matrigel / 3 wt.% PEG‐2 mM RGD hydrogels and 3 wt.% PEG‐0 mM RGD / No Gel groups. C) Gene ontology (GO), Reactome, and KEGG pathway analyses highlighting distinct biological processes and signaling pathways enriched in different conditions. Averaged gene expression levels related to D) cell‐ECM interaction and mechanotransduction, E) vasculature development, F) heart development, and G) ion channels across the different culture groups.

We then grouped Matrigel and 3 wt.% PEG‐2 mM RGD hydrogels to compare with the 3 wt.% PEG‐0 mM RGD hydrogels and no gel group. Volcano plot analysis showed that there were 1953 genes upregulated in 3 wt.% PEG‐0 mM RGD hydrogels and no gel group (Figure 5B), which are enriched in nervous system development (LRP2, GBX2 and NGFR), embryonic morphogenesis (SOX2, TFAP2A and POU3F4) and cell junction organization (ITGA2, CLDN11 and GABRB3) (Figure 5C). 2560 genes were upregulated in Matrigel and 3 wt.% PEG‐2 mM RGD hydrogels group, which are enriched in heart development (ACTN2, NKX2‐5 and MYH6), smooth muscle development (ACTA1, TAGLN and ACTC1), vasculature development (ANG, ANGPT1, EDN1 and VEGFC) and extracellular matrix organization (COL1A1, COL3A1, and MMP2).

We further analyzed genes of interest related to cell‐ECM interactions, ion channels, vasculature development, and heart development across all groups. In the RGD‐incorporated PEG hydrogel, we observed a gene expression profile similar to Matrigel, with high expression of genes involved in cell‐ECM interactions (COL3A1, ITGA1, ITGB5, ECM1, MMP2, and MMP10), likely due to the presence of adhesion molecules in these conditions (Figure 5D). However, the expression of mechanotransduction‐related genes (TAZ, ZIC1, TMC2, and KCNK10) were upregulated in both the PEG‐0 mM RGD hydrogel and the no‐gel groups (Figure 5D). More importantly, genes associated with heart development (MYH6, ACTC1, MYL7, NKX2.5, and TBX5) and vasculature development (ETS1, CDH5, ENG, VCAM1, and TGFBR2), and ion channel (CACNA1C, CACNA1G, KCNJ5, KCNK6, and SCN5A) were highly expressed in both the Matrigel and 3 wt.% PEG‐2 mM RGD hydrogels (Figure 5E–G). These findings further demonstrate that RGD‐functionalized PEG hydrogels have a comparable effect to Matrigel in promoting cardiac differentiation.

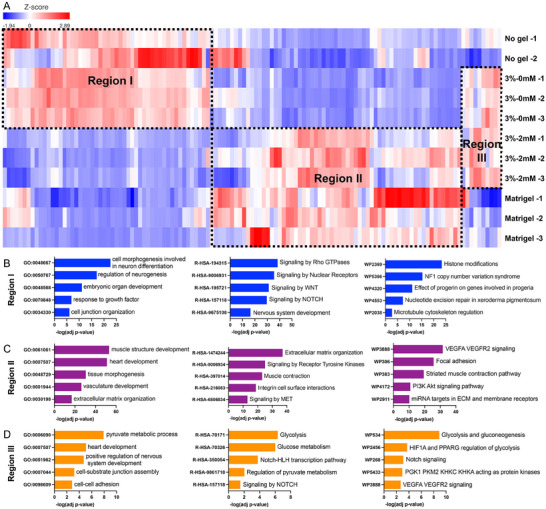

Next, we selected the top 1000 genes with the highest variance from all the samples and plotted them in a heatmap with hierarchical cluster analysis (Figure 6A). The segregation of these genes can be identified as three main regions: Region I highly expressed in no gel and 3 wt.% PEG – 0mM RGD hydrogel groups, Region II highly expressed in Matrigel and 3 wt.% PEG – 2mM RGD hydrogel groups, and Region III highly expressed in PEG hydrogel groups with/out RGD. Next, we performed a global analysis of biological processes (Gene Ontology) and signaling pathways (Reactome Pathway and WikiPathway) based on the gene expression patterns for each region. Region I highlighted embryonic morphogenesis and nervous system development, while pathway analysis showed high enrichment in Rho GTPases signaling and WNT signaling, which are associated with stem cell maintenance and neuron differentiation (Figure 6B). Region II showed gene enrichment associated with heart formation and vasculature development, and pathway analysis showed high enrichment in VEGF and PI3K‐Akt signaling and muscle contraction (Figure 6C). Region III had the genes enriched of metabolic process and involved in NOTCH signaling.

Figure 6.

Analysis of top 1000 genes with highest variances. A) Heatmap and hierarchical clustering showed distinct transcriptome profiles among different groups for the top 1000 genes with highest variance. B–D) Gene ontology, Reactome analysis and KEGG pathway showed 3%‐2mm RGD and Matrigel derived organoids highly enriched the genes associated with heart development, calcium signaling and contractile functions, while 3%‐0mM RGD and No gel cultured organoids expressed the genes associated with embryonic development. The genes enriched in PEG hydrogel groups are related to metabolic activity and NOTCH signaling.

We compared the top 1000 differentially expressed genes across all four groups using volcano plots, applying thresholds of p‐values <0.05 and fold changes >2 (Figure S7, Supporting Information). In both the 3 wt.% PEG without RGD and suspension culture conditions, genes associated with pluripotency and embryonic morphogenesis (SOX2, SOX11, HOXB2) and neuron development (TUBB2B, TUBB3, and NGFR) were upregulated. In contrast, the genes upregulated in Matrigel were typical cardiomyocyte markers (MYL9, MYL7, and MYH6) and endothelial markers (AQP1, ENG, CDH7) (Figure S7A,B, Supporting Information). Compared to Matrigel, the cardioids from RGD‐functionalized PEG hydrogels showed an enrichment of genes involved in ECM synthesis (COL1A1, COL5A1, and EMC10) and connective tissue development (EGR1, FOS, and PDGFRB) (Figure S7C, Supporting Information). Additionally, when compared to PEG hydrogels without RGD, cardioids cultured in RGD‐functionalized PEG hydrogels displayed higher expression of cardiac markers (ACTN2, NKX2.5, MYH7, and MYH6) (Figure S7D, Supporting Information). This comparative analysis highlights that PEG hydrogels functionalized with RGD promoted more robust expression of cardiac‐specific markers in cardioids compared to the culture conditions without external adhesion molecules. To validate the bulk RNAseq results, we analyzed the cardiac markers (MYH6, MYH7, TNNI1, MYL7) using RT‐qPCR (Figure S8, Supporting Information). These cardiac‐specific genes were expressed much higher in the cardioids generated from Matrigel and RGD incorporated PEG hydrogel, compared to those generated in RGD‐free hydrogel and No gel groups. The RT‐qPCR results had a similar trend with the bulk RNAseq results.

3. Discussion

3.1. Synthetic PEG Hydrogel Improved Cardioid Reproducibility

Despite Matrigel's effectiveness in culturing organoids, its tumor‐derived origin, batch variability, and inconsistent biochemical properties lead to poor reproducibility in organoid culture and differentiation. To address these challenges and improve organoid reproducibility, chemically and mechanically defined synthetic hydrogels have been developed as suitable alternatives for various organoid cultures.[ 13 , 16 , 18 , 20 ] In this study, we established fully defined synthetic PEG hydrogels for the 3D culture of cardioids in vitro. Hydrogel encapsulation proved more efficient in inducing cardioid differentiation compared to traditional suspension cultures. Cardioids grown in PEG‐based hydrogels demonstrated similar morphological development, contractile functions, and transcriptomic profiles to those cultured in Matrigel. The improved reproducibility in organoid morphology, chamber formation, contractile functions, and transcriptomics profiles further highlight the advantages and reliability of these well‐defined polymers over Matrigel for cardioid culture. This indicates that these well‐defined synthetic hydrogels can serve as effective alternatives to animal‐derived matrices for culturing cardioids.

Several studies have reported that matrices that are either too stiff or too soft can hinder organoid formation and negatively affect organoid development and function.[ 13 , 20 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ] Similarly, we found that increasing hydrogel stiffness imposed greater mechanical constraint, which restricted the growth of cardioids and induced cell death. The stiffest hydrogels (8 wt.% PEG) led to a reduced beat rate and altered calcium transient. Thus, softer hydrogel may be more favorable for cardioid differentiation and culture. Though this study did not focus on the molecular mechanisms that drive the differences in contractile function and cardioid development, it is believed that several mechanotransduction signaling pathways, such as RhoA/ROCK and YAP/TAZ, might be involved in this process. For example, increased YAP activity has been linked to enhanced cardiac differentiation and maturation.[ 50 , 51 ] Our transcriptomics analysis also revealed high expression of YAP in the RGD‐incorporated hydrogel and Matrigel compared to suspension‐cultured organoids and hydrogels without RGD. We attempted to develop hydrogel with stiffness as low as Matrigel by reducing PEG concentration to 1–2 wt.%, but the formed hydrogels were too soft to handle. Designing new PEG hydrogels with lower stiffness to further investigate their impact on cardioid development would be of great interest to future work.

3.2. Cardioids for Modeling Nascent Chamber Formation During Embryogenesis

Due to their 3D spherical structure, cardioids lack the aligned tissue architecture characteristic of mature heart muscle. In contrast, engineered heart tissues (EHTs) are typically assembled after cells have already differentiated into cardiomyocytes or other relevant cell types. This offers greater control over the spatial arrangement of cells to form the cardiac tissues that more closely resemble the mature heart architecture. While cardioids have limitations in terms of tissue maturation, they possess unique properties that allow them to model heart chamber formation in vitro. Cardioids intrinsically form chamber‐like cavities through the synergistic modulation of FGF, BMP4, and Wnt signaling pathways.[ 5 , 52 , 53 ] In this study, we showed that cavity formation within our cardioids was modulated by the mechanical properties of the surrounding matrix. Previous research has shown that Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development, acting through EphrinB2 to activate NRG1 in the ventricles.[ 54 , 55 ] Consistent with this, we observed higher expression of Notch signaling‐associated genes in cardioids encapsulated in PEG hydrogels compared to those in suspension, leading to the formation of larger cavities. This suggests that cardiac chamber formation is influenced by both biochemical and biomechanical cues during heart development. However, cavity sizes in our cardioids were smaller than those reported in other chambered cardioid models, likely due to insufficient biochemical induction, such as BMP4. Moving forward, our research will focus on promoting full chamber formation within cardioids by manipulating canonical BMP and Notch signaling pathways in conjunction with our engineered matrix.

3.3. Cell Adhesive Motif Promoted Endothelial Development in Cardioids

Incorporation of cell adhesion peptides, such as RGD, AG73, IKVAV, GFOGER, and YIGSR, were reported to affect the morphogenesis and differentiation of organoids.[ 13 , 20 , 24 , 25 , 48 ] We also demonstrated that functionalization of hydrogels with 2 mM RGD enhanced the cardioid differentiation, indicating that cell adhesion peptides are crucial factors in cardioid development. More importantly, our transcriptomic results demonstrated that both Matrigel and PEG hydrogels functionalized with RGD promoted the endothelial gene expression, suggesting a potential enhancement of endothelial cell differentiation in the cardioids. Previous studies have demonstrated that RGD functionalized hydrogels could enhance the endothelial cell differentiation of encapsulated embryoids bodies and mesenchymal stem cells.[ 56 , 57 , 58 ] The intercellular crosstalk between endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes is critical for heart development. Incorporation of vascular cells could improve cardiac functionality by regulating cardiomyocyte proliferation,[ 59 ] contractile force,[ 60 ] and maturation.[ 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ] The detailed cell composition and the relative cell ratio in the cardioids were still unclear, future work to expand this study will focus on lineage tracking and single‐cell RNA sequencing to unveil the cell identities and cell heterogeneity.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we developed a chemically and mechanically defined PEG hydrogel matrix for in vitro culture of human cardioids. The optimized PEG hydrogel (3 wt.% PEG‐2mM RGD) supported organoid growth, cardiac differentiation, nascent chamber formation, and contractile functions. Compared to commonly used suspension culture condition, hydrogel encapsulation with cell adhesion motif further promoted cardiovascular development and nascent chamber formation. Compared to traditional Matrigel encapsulation, synthetic hydrogel improved the reproducibility in both structural properties and transcriptomics of cardioids. These results underscore potential of PEG hydrogels as an alternative to Matrigel for human cardioid culture and their future translational applications.

5. Experimental Section

Hydrogel Fabrication

Stock solutions (20 wt.% w/v) of 8‐arm PEG‐norbornene macromer 20kDa (Creative PEGWorks, TX, US), MMP‐degradable peptide crosslinker GKKCGPQG↓IWGQCKKG (Genscript, NJ, US) and adhesion peptide RGD (peptide sequence: CRGDS, Genscript, NJ, US) were prepared by dissolving them in PBS. Hydrogel precursor solutions were made by mixing PEG stock solution, thiol‐terminated peptide (1:1 thiol:ene ratio) and 0.05 wt.% of the photo‐initiator lithium phenyl‐2,4,6‐trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP). Hydrogels were polymerized under ultraviolet (UV) light (≈5 mW cm−2, 365 nm) for 3 min and transferred to phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) for 24 h before characterization. The RGD concentrations of 1 and 2 mM and the hydrogel concentrations of 3%, 5%, and 8% were investigated in this study.

Mechanical Characterization

Rheological properties of hydrogels were characterized on a DR‐H3 rheometer using an 8 mm plate (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, US). To determine initial storage (G’) and loss (G″) modulus, the polymerized hydrogels were allowed to swell for 24 h at 37 °C in PBS. A frequency sweep was then conducted at 1–10 rad s−1 under 1% strain, which was determined to be within the linear viscoelastic range. To measure changes in modulus over time, hydrogels were periodically analyzed over the period indicated.

To test the swelling ratio, the hydrogel samples were immersed in PBS for 24 h at room temperature. The swollen weight (Ws) was recorded after blotting to remove excess PBS. The hydrogels were then freeze dried to determine the dry weight (Wd). The swelling ratio was calculated by the following equation:

| (1) |

Hydrogel mesh size was estimated using the mass of hydrogels at equilibrium swelling and after lyophilization as previously described.[ 65 ]

Ellman's Assay

Cysteine standards and Ellman's reagent were reconstituted in 0.1 m sodium phosphate reaction buffer (pH 8) with 1 mM EDTA. The PEG macromer and dithiol peptide linker were then mixed at a 1:1 molar ratio of norbornene to thiol groups (3 mM Norb.: 3 mM SH) and photocured in the presence of LAP. Unreacted peptide concentrations were determined by mixing 25 µL of the sample with 5 µL of reconstituted Ellman's reagent and 250 µL of reaction buffer. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min before spectrophotometric analysis at 412 nm.

Human iPSC Maintenance

WTC‐11 and genome‐edited GCaMP6f hiPSC lines (Bruce Conklin lab, Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases) were maintained in Essential‐8 (E8) medium (ThermoFisher, Catalog # A1517001) in six‐well tissue culture plates coated with 1% Geltrex (Fisher Scientific, Catalog # A1413302) in a 37 °C incubator containing 5% CO2. Media was changed daily, and cells were passaged with Accutase (Stem Cell Tech. Catalog # 7922) when reaching ≈70% confluency. 10 µM ROCK inhibitor Y‐27632 (Stem Cell Technologies, Catalog # 72308) was used for the first 24 h post‐dissociation to improve cell viability.

Generation of Cardioids

hiPSCs were dissociated and seeded at a concentration of 3000, 5000, and 10 000 cells per well in a round bottom ultra‐low‐attachment 96‐well plate (Costar) in E8 medium supplemented with 10 µM Y‐27632 (Stem Cell Tech. Catalog # 72308), centrifuged at 300 g and 4 °C for 4 min, and then placed in the incubator for hiPSC aggregates formation. Differentiation of these aggregates was initiated on Day 0 by replacing the E8 medium with RPMI/1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Catalog # 11875135) containing B27 supplement minus insulin (RPMI/B27‐I) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Catalog # A1895601) and 6 µm CHIR99021 (Stem Cell Technology, Catalog # 100‐1042). After 24 h, the medium was changed to RPMI/B27–I. On Day 2, RPMI/B27–I supplemented with 5 µM IWP4 (Stem Cell technology, Catalog # 72554) was added for 48 h and then changed to RPMI/B27–I on Day 4. From Day 6 onward, aggregates were cultivated in RPMI 1640 containing B27 complete supplement (RPMI/B27+C) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Catalog # A3582801). On day 6, the aggregates were collected from 96‐well plates and then mixed with the hydrogel precursor solution. The aggregate‐hydrogel precursor was pipetted into 12‐well plates and photopolymerized under UV light for 3 min. Immediately after polymerization, RPMI/B27+C was added to the plate and changed every 2 days. For Matrigel encapsulation, cardioids were embedded in a Matrigel droplet (Corning, Catalog # 354234) and cast into a 12‐well plates on day 6. After embedding, the plate was placed in the incubator for 30 min to let the Matrigel solidify. In addition, aggregates that continued to be cultured in the 96‐well plates without any encapsulation process were used as No Gel group.

Organoid Viability

To evaluate the survivability of encapsulated organoids, the LIVE/DEAD assay (Invitrogen, Catalog #L3224) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. 2 days after encapsulation, Calcein AM (2 µm) and ethidium homodimer (4 µM) were added directly to the culture medium. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, samples were imaged with Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with Zyla 4.2 PLUS sCMOS camera. The level of cell death was quantified by measuring the fluorescent intensity of the red channel with Image J.

Functional Characterization of Cardioids

At Day 20, GCaMP6f hiPSC‐derived cardioids were imaged in an onstage microscope incubator (OkoLab Stage Top Incubator, UNO‐T‐H‐CO2) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 to maintain physiological conditions on a Nikon Ti‐E inverted microscope with Andor Zyla 4.2+ digital CMOS camera. Videos of contracting cardioids were recorded at 50 frames per second for 10 s in brightfield and exported as a series of single‐frame image files. Contraction physiology was analyzed using video‐based motion tracking software that computes motion vectors based on pixel movement.[ 35 ] For calcium transient analysis, videos were taken under 488 nm excitation at 40 ms exposure time with 25 frames per second. Calcium flux signals were exported as Z‐axis profiles in ImageJ. The fluorescence bleaching decay was corrected and related parameters t0, t50, t75 were computed using in‐house MATLAB scripts. The rising time t0 is defined as the time it takes for the calcium flux to reach peak fluorescence intensity, whereas decay time t50 and t75 represent the time it takes for the calcium flux to decay by 50% and 75% of the peak fluorescent intensity, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry Staining

On day 20, hydrogel‐encapsulated organoids were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min at room temperature. Hydrogels were then washed three times with PBS and embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature solution (OCT, Tissue‐Tek). Then, the organoids were cryo‐sectioned using a Leica CM13050S UV cryostat into 10 µm sections and mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). Samples were incubated in primary antibodies (Table S1, Supporting Information) for 2 h at room temperature, washed with PBS three times, and then secondary antibodies for 1.5 h. Finally, after three PBS washes, the cells were incubated with DAPI for nuclei staining for 10 min. All samples were imaged using a Zeiss 980 confocal microscope. To quantify the cavities inside the cardioids, Image J was used to calculate the area and dimension of the cavities. The cavities were first located in the fluorescent images of the organoids. The cavity area ratio was calculated based on the total cavity area and entire cardioid area (Figure S1, Supporting Information). The cavity dimension was calculated based on the length of the cavity (estimated longest distance). The sarcomere distances were quantified based on two adjacent sarcomere structures of the cardioids using Image J.

Bulk RNA Sequencing

On day 20, cardioids were collected from the hydrogels, centrifuged, and washed with PBS several times to remove all the remaining medium. mRNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, #15596026), Chloroform (Serva, #39553.01), and isopropanol (Fisher, BP2618). The RNA pellet was dissolved into 40uL UltraPureTM DEPC treated water (Invitrogen, #750023) and reserved at −80 °C. The RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop Microvolume UV–Vis Spectrophotometer. The RNA quality was evaluated using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer at Molecular Analysis Core, SUNY Upstate Medical University. The samples with RIN ≥ 8.0 and concentration ≥ 50 ng µL−1 were used for bulk RNA sequencing (Azenta USA Inc). The Illumina Ribo‐Zero rRNA removal kit was used for rRNA depletion of all the samples. The samples were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq with 2 × 150 base pairs configuration, single index, paired‐end reads per lane.

The raw FASTQ files were analyzed using the Partek Flow software, a shared license provided by SUNY Upstate Medical Genomics Core. The unaligned reads were trimmed for bases to obtain a Phred quality score >20 and then aligned using the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) to the human genome (hg38). The post‐alignment assessment was conducted for quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC), which showed the percentage of alignment for each sample was > 75%. The average base quality score per read was between 35.8 and 38.7, indicating good quality reads. Post‐alignment quantification was applied to an annotation model and normalized based on the recommended parameters of counts per million (CPM). The downstream analysis included principal component analysis (PCA), differential gene expression (DESeq), hierarchical clustering, gene ontology (GO), and pathway analysis.

Quantification of Organoid Reproducibility

The coefficient of variation (CV), measuring the dispersion of a probability distribution, was a commonly used method to assess the reproducibility of organoids development.[ 45 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 ] To compare the reproducibility of cardioids under different culture conditions, the CV = σw/µ was calculated, where σw is the standard deviation of the samples, while µ is the mean value. The higher the coefficient of variation, the greater the dispersion level around the mean, but lower reproducibility in samples.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. At least three biological replicates were included in each group for different organoid differentiation. Multiple organoids (6–15 organoids) were analyzed for each differentiation batch as technical replicates. Statistics are analyzed using one‐way ANOVA with the Tukey post‐hoc test. All analysis was performed using Prism 10 (GraphPad). Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Y.S. and Z.M. designed the experiments. Y.S., A.K. and N.Y.M. performed the biological experiments and data analyses. Y.S. and M.S. performed the hydrogel characterization. E.J. advised on material design and characterization. H.Y. provided insights on cardioid properties. Y.S. and Z.M. wrote the manuscript with discussion and improvement from all the authors. Z.M. supervised the project development and funded the study.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supplemental Video 1

Supplemental Video 2

Supplemental Video 3

Supplemental Video 4

Supplemental Video 5

Supplemental Video 6

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH NICHD (R01HD101130 and R15HD108720) and NSF (CBET‐1804875, CBET‐1943798, and CMMI‐2130192), and Research Seed Grants (2021 and 2023) from UNT Research and Innovation Office (H.X.Y.).

Song Y., Seitz M., Kowalczewski A., Mai N. Y., Jain E., Yang H., Ma Z., Mechanically and Chemically Defined PEG Hydrogels Improve Reproducibility in Human Cardioid Development. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2025, 14, 2403997. 10.1002/adhm.202403997

Data Availability Statement

The raw and processed data required to reproduce these findings will be made available via contact with the corresponding author Z.M. (zma112@syr.edu).

References

- 1. Mensah G. A., Roth G. A., Fuster V., J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lewis‐Israeli Y. R., Wasserman A. H., Gabalski M. A., Volmert B. D., Ming Y., Ball K. A., Yang W., Zou J., Ni G., Pajares N., Chatzistavrou X., Li W., Zhou C., Aguirre A., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drakhlis L., Biswanath S., Farr C.‐M., Lupanow V., Teske J., Ritzenhoff K., Franke A., Manstein F., Bolesani E., Kempf H., Liebscher S., Schenke‐Layland K., Hegermann J., Nolte L., Meyer H., de la Roche J., Thiemann S., Wahl‐Schott C., Martin U., Zweigerdt R., Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drakhlis L., Devadas S. B., Zweigerdt R., Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hofbauer P., Jahnel S. M., Papai N., Giesshammer M., Deyett A., Schmidt C., Penc M., Tavernini K., Grdseloff N., Meledeth C., Ginistrelli L. C., Ctortecka C., Salic S., Novatchkova M., Mendjan S., Cell 2021, 184, 3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Volmert B., Kiselev A., Juhong A., Wang F., Riggs A., Kostina A., O'Hern C., Muniyandi P., Wasserman A., Huang A., Lewis‐Israeli Y., Panda V., Bhattacharya S., Lauver A., Park S., Qiu Z., Zhou C., Aguirre A., Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim S., Min S., Choi Y. S., Jo S.‐H., Jung J. H., Han K., Kim J., An S., Ji Y. W., Kim Y.‐G., Cho S.‐W., Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hughes C. S., Postovit L. M., Lajoie G. A., Proteomics 2010, 10, 1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tian A., Muffat J., Li Y., J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Talbot N. C., Caperna T. J., Cytotechnology 2015, 67, 873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gjorevski N., Sachs N., Manfrin A., Giger S., Bragina M. E., Ordóñez‐Morán P., Clevers H., Lutolf M. P., Nature 2016, 539, 560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gjorevski N., Lutolf M. P., Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cruz‐Acuña R., Quirós M., Farkas A. E., Dedhia P. H., Huang S., Siuda D., García‐Hernández V., Miller A. J., Spence J. R., Nusrat A., García A. J., Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Del Bufalo F., Manzo T., Hoyos V., Yagyu S., Caruana I., Jacot J., Benavides O., Rosen D., Brenner M. K., Biomaterials 2016, 84, 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balion Z., Cepla V., Svirskiene N., Svirskis G., Druceikaite K., Inokaitis H., Rusteikaite J., Masilionis I., Stankeviciene G., Jelinskas T., Ulcinas A., Samanta A., Valiokas R., Jekabsone A., Biomolecules 2020, 10, 754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fattah A. R. A., Daza B., Rustandi G., Berrocal‐Rubio M. A., Gorissen B., Poovathingal S., Davie K., Barrasa‐Fano J., Condor M., Cao X., Rosenzweig D. H., Lei Y., Finnell R., Verfaillie C., Sampaolesi M., Dedecker P., Van Oosterwyck H., Aerts S., Ranga A., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graney P. L., Zhong Z., Post S., Brito I., Singh A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2022, 110, 1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mosquera M. J., Kim S., Bareja R., Fang Z., Cai S., Pan H., Asad M., Martin M. L., Sigouros M., Rowdo F. M., Ackermann S., Capuano J., Bernheim J., Cheung C., Doane A., Brady N., R. Singh , Rickman D. S., Prabhu V., Allen J. E., Puca L., Coskun A. F., Rubin M. A., Beltran H., Mosquera J. M., Elemento O., Singh A., Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yin X., Mead B. E., Safaee H., Langer R., Karp J. M., Levy O., Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glorevski N., Sachs N., Manfrin A., Giger S., Bragina M. E., Ordonez‐Moran P., Clevers H., Lutolf M. P., Nature 2016, 539, 560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ruiter F. A. A., Morgan F. L. C., Roumans N., Schumacher A., Slaats G. G., Moroni L., LaPointe V. L. S., Baker M. B., Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2200543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Isik M., Okesola B. O., Eylem C. C., Kocak E., Nemutlu E., D'Este M., Mata A., Derkus B., Acta Biomater. 2023, 171, 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ye S., Boeter J. W. B., Mihajlovic M., van Steenbeek F. G., van Wolferen M. E., Oosterhoff L. A., Marsee A., Caiazzo M., van der Laan L. J. W., Penning L. C., Vermonden T., Spee B., Schneeberger K., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sorrentino G., Rezakhani S., Yildiz E., Nuciforo S., Heim M. H., Lutolf M. P., Schoonjans K., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poudel H., Sanford K., Szwedo P. K., Pathak R., Ghosh A., ACS Omega 2022, 7, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hernandez‐Gordillo V., Kassis T., Lampejo A., Choi G., Gamboa M. E., Gnecco J. S., Brown A., Breault D. T., Carrier R., Griffith L. G., Biomaterials 2020, 254, 120125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takada T., Sasaki D., Matsuura K., Miura K., Sakamoto S., Goto H., Ohya T., Iida T., Homma J., Shimizu T., Hagiwara N., Biomaterials 2022, 281, 121351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maiullari F., Costantini M., Milan M., Pace V., Chirivi M., Maiullari S., Rainer A., Baci D., Marei H. E., Seliktar D., Gargioli C., Bearzi C., Rizzi R., Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Young J. L., Engler A. J., Biomaterials 2011, 32, 1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DeLeon‐Pennell K. Y., Meschiari C. A., Jung M., Lindsey M. L., Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017, 147, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spinale F. G., Circ. Res. 2002, 90, 520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Halade G. V., Jin Y. F., Lindsey M. L., Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 139, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Euler G., Locquet F., Kociszewska J., Osygus Y., Heger J., Schreckenberg R., Schlüter K.‐D., Kenyeres É., Szabados T., Bencsik P., Ferdinandy P., Schulz R., Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2021, 35, 353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baniasadi H., Madani Z., Ajdary R., Rojas O. J., Seppälä J., Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 130, 112424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoang P., Kowalczewski A., Sun S., Winston T. S., Archilla A. M., Lemus S. M., Ercan‐Sencicek A. G., Gupta A. R., Liu W., Kontaridis M. I., Amack J. D., Ma Z., Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hoang P., Wang J., Conklin B. R., Healy K. E., Ma Z., Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bajaj P., Tang X., Saif T. A., Bashir R., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 95, 1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Engler A. J., Carag‐Krieger C., Johnson C. P., Raab M., Tang H.‐Y., Speicher D. W., Sanger J. W., Sanger J. M., Discher D. E., J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ribeiro M. C., Slaats R. H., Schwach V., Rivera‐Arbelaez J. M., Tertoolen L. G. J., van Meer B. J., Molenaar R., Mummery C. L., Claessens M. M. A. E., Passier R., J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 141, 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pioner J. M., Santini L., Palandri C., Langione M., Grandinetti B., Querceto S., Martella D., Mazzantini C., Scellini B., Giammarino L., Lupi F., Mazzarotto F., Gowran A., Rovina D., Santoro R., Pompilio G., Tesi C., Parmeggiani C., Regnier M., Cerbai E., Mack D. L., Poggesi C., Ferrantini C., Coppini R., Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1030920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pioner J. M., Guan X., Klaiman J. M., Racca A. W., Pabon L., Muskheli V., Macadangdang J., Ferrantini C., Hoopmann M. R., Moritz R. L., Kim D.‐H., Tesi C., Poggesi C., Murry C. E., Childers M. K., Mack D. L., Regnier M., Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Psaras Y., Margara F., Cicconet M., Sparrow A. J., Repetti G. G., Schmid M., Steeples V., Wilcox J. A. L., Bueno‐Orovio A., Redwood C. S., Watkins H. C., Robinson P., Rodriguez B., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E., Toepfer C. N., Circ. Res. 2021, 129, 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kyrychenko V., Kyrychenko S., Tiburcy M., Shelton J. M., Long C., Schneider J. W., Zimmermann W.‐H., Bassel‐Duby R., Olson E. N., JCI Insight 2017, 2, 95918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moretti A., Fonteyne L., Giesert F., Hoppmann P., Meier A. B., Bozoglu T., Baehr A., Schneider C. M., Sinnecker D., Klett K., Fröhlich T., Rahman F. A., Haufe T., Sun S., Jurisch V., Kessler B., Hinkel R., Dirschinger R., Martens E., Jilek C., Graf A., Krebs S., Santamaria G., Kurome M., Zakhartchenko V., Campbell B., Voelse K., Wolf A., Ziegler T., Reichert S., et al., Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim S., Min S., Choi Y. S., Jo S. H., Jung J. H., Han K., Kim J., An S., Ji Y. W., Kim Y. G., Cho S. W., Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Capeling M. M., Czerwinski M., Huang S., Tsai Y.‐H., Wu A., Nagy M. S., Juliar B., Sundaram N., Song Y., Han W. M., Takayama S., Alsberg E., Garcia A. J., Helmrath M., Putnam A. J., Spence J. R., Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 12, 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hushka E. A., Yavitt F. M., Brown T. E., Dempsey P. J., Anseth K. S., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2020, 9, 1901214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. DiMarco R. L., Dewi R. E., Bernal G., Kuo C., Heilshorn S. C., Biomater. Sci. 2015, 3, 1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Candiello J., Grandhi T. S. P., Goh S. K., Vaidya V., Lemmon‐Kishi M., Eliato K. R., Ros R., Kumta P. N., Rege K., Banerjee I., Biomaterials 2018, 177, 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Heng B. C., Zhang X., Aubel D., Bai Y., Li X., Wei Y., Fussenegger M., Deng X., Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mills R. J., Titmarsh D. M., Koenig X., Parker B. L., Ryall J. G., Quaife‐Ryan G. A., Voges H. K., Hodson M. P., Ferguson C., Drowley L., Plowright A. T., Needham E. J., Wang Q.‐D., Gregorevic P., Xin M., Thomas W. G., Parton R. G., Nielsen L. K., Launikonis B. S., James D. E., Elliott D. A., Porrello E. R., Hudson J. E., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E8372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schmidt C., Deyett A., Ilmer T., Haendeler S., Caballero A. T., Novatchkova M., Netzer M. A., Ginistrelli L. C., Juncosa E. M., Bhattacharya T., Mujadzic A., Pimpale L., Jahnel S. M., Cirigliano M., Reumann D., Tavernini K., Papai N., Hering S., Hofbauer P., Mendjan S., Cell 2023, 186, 5587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ho B. X., Pang J. K. S., Chen Y., Loh Y.‐H., An O., Yang H. H., Seshachalam V. P., Koh J. L. Y., Chan W.‐K., Ng S. Y., Soh B. S., Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grego‐Bessa J., Luna‐Zurita L., del Monte G., Bolós V., Melgar P., Arandilla A., Garratt A. N., Zang H., Mukouyama Y.‐S., Chen H., Shou W., Ballestar E., Esteller M., Rojas A., Pérez‐Pomares J. M., de la Pompa J. L., Dev. Cell 2007, 12, 415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Samsa L. A., Givens C., Tzima E., Stainier D. Y. R., Qian L., Liu J., Development 2015, 142, 4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schukur L., Zorlutuna P., Cha J. M., Bae H., Khademhosseini A., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2013, 2, 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gallagher L. B., Dolan E. B., O'Sullivan J., Levey R., Cavanagh B. L., Kovarova L., Pravda M., Velebny V., Farrell T., O'Brien F. J., Duffy G. P., Acta Biomater. 2020, 107, 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rupp P. A., Little C. D., Circ. Res. 2001, 89, 566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tulloch N. L., Muskheli V., Razumova M. V., Korte F. S., Regnier M., Hauch K. D., Pabon L., Reinecke H., Murry C. E., Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Voges H. K., Foster S. R., Reynolds L., Parker B. L., Devilee L., Quaaife‐Ryan G. A., Fortuna P. R. J., Mathieson E., Fitzsimmons R., Lor M., Batho C., Reid J., Pocock M., Friedman C. E., Mizikovsky D., Francois M., Palpant N. J., Needham E. J., Peralta M., del Monte‐Nieto G., Jone L. K., Smyth I. M., Mehdiabadi N. R., Bolk F., Janbandhu V., Yao E., Harvey R. P., Chong J. J. H., Elliott D. A., Stanley E. G., Wiszniak S., Schwarz Q., James D. E., Mills R. J., Porrello E. R., Hudson J. E., Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Giacomelli E., Bellin M., Sala L., Van Meer B. J., Tertoolen L. G. J., Orlova V. V., Mummery C. L., Development 2017, 144, 1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Giacomelli E., Meraviglia V., Campostrini G., Cochrane A., Cao X., van Helden R. W. J., Krotenberg Garcia A., Mircea M., Kostidis S., Davis R. P., van Meer B. J., Jost C. R., Koster A. J., Mei H., Míguez D. G., Mulder A. A., Ledesma‐Terrón M., Pompilio G., Sala L., Salvatori D. C. F., Slieker R. C., Sommariva E., de Vries A. A. F., Giera M., Semrau S., Tertoolen L. G. J., Orlova V. V., Bellin M., Mummery C. L., Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Helle E., Ampuja M., Dainis A., Antola L., Temmes E., Tolvanen E., Mervaala E., Kivela R., Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 100280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. King O., Cruz‐Moreira D., Sayed A., Kermani F., Kit‐Anan W., Sunyovszki I., Wang B. X., Downing B., Fourre J., Hachim D., Randi A. M., Stevens M. M., Rasponi M., Terracciano C. M., Cell Rep. Methods 2022, 2, 100280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Van Hove A. H., Wilson B. D., Benoit D. S. W., J. Vis. Ex. 2013, 29, 50890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nickels S. L., Modamio J., Mendes‐Pinheiro B., Monzel A. S., Betsou F., Schwamborn J. C., Stem Cell Res. 2020, 46, 101870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Glass M. R., Waxman E. A., Yamashita S., Lafferty M., Beltran A. A., Farah T., Patel N. K., Singla R., Matoba N., Ahmed S., Srivastava M., Drake E., Davis L. T., Yeturi M., Sun K., Love M. I., Hashimoto‐Torii K., French D. L., Stein J. L., Stem Cell Rep. 2024, 19, 1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kang H. M., Kim D. S., Kim Y. K., Shin K., Ahn S. J., Jung C. R., Int. J. Stem Cells 2024, 17, 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Park S. E., Kang S., Paek J., Georgescu A., Chang J., Yi A. Y., Wilkins B. J., Karakasheva T. A., Hamilton K. E., Huh D. D., Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supplemental Video 1

Supplemental Video 2

Supplemental Video 3

Supplemental Video 4

Supplemental Video 5

Supplemental Video 6

Data Availability Statement

The raw and processed data required to reproduce these findings will be made available via contact with the corresponding author Z.M. (zma112@syr.edu).