Abstract

Background

The pressures on community Children and Young People’s Mental Health Service (CYPMHS) clinicians to manage and maintain caseloads can be immense, therefore discharging young people from CYPMHS in a safe and timely way is often discussed as a priority. However, there is limited research into how discharge can be done well, especially for discharge occurring prior to children and young people (CYP) reaching the upper age limit of CYPMHS. Thus, this study aimed to gain a better understanding of the barriers and facilitators discharging CYP from community CYPMHS, by exploring clinicians experiences of discharging CYP from their service.

Method

Semi-structured interviews of 30–40 minutes were conducted with 12 clinicians working at different CYPMHS in England and analysed using codebook thematic analysis.

Results

Six themes were identified. These included, “perfectionistic approach towards treatment outcomes”, “reducing dependence on CYPMHS through empowerment”, “a lack of flexibility in the wider system”, “lack of collaborative care”, “an increasing pressure on the service” and “keeping the focus on discharge”.

Conclusion

Clinicians face multiple barriers when discharging CYP which should be addressed, alongside enhancing the use of reported facilitators to ensure timely, safe and well-managed discharges.

Keywords: Thematic analysis, discharge, children and young people, mental health services, CYPMHS

Plain Language Summary

Little research has been conducted on the discharge pathway at child and adolescent mental health services (CYMPHS) despite it being the way in which many young people will leave the service. Additionally, the few studies which are present, indicate that discharge is poorly managed and can be delayed. They have also mainly focused on young people who were around 16–18 years old. Thus, this study aimed to gain a better understanding of the discharge pathway, specifically the barriers and facilitators of discharging children and young people across all ages from CYMPHS. The researchers interviewed twelve clinicians from CYMPHS across the UK. We found that multiple barriers affected the ability of clinicians to carry out a timely, and well-planned discharge such as families becoming too attached, a disjointed and inflexible mental health care system, lengthy waiting times, high staff turnover and a lack of focus on discharge planning from the outset. However, there were also some facilitators, which included helping families become self-confident, regular communication with all relevant parties, and using supervision to keep the focus on discharge. The findings of this study can be used to improve the current discharge pathway at CYMPHS, and to hopefully bring attention to this topic which has been so far fairly neglected.

Introduction

Community Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) play a crucial role in assessing and supporting children and young people (CYP) up to the age of 18 with mental health difficulties in the UK. Community CYPMHS are part of a larger network of NHS mental health services for CYP, each of which may have their own specialist focus, including; neurodevelopmental diagnosis, crisis home treatment, eating disorders and inpatient services.

Whilst there have been several studies exploring how to better engage young people in community CYPMHS and how these services can best meet the needs of young people (Coyne et al., 2015; McNicholas et al., 2016; Stafford et al., 2020), there is comparatively little evidence regarding how to manage the process whereby a young person’s care comes to an end. Care ending could be due to several factors, including a natural discontinuation of support once a young person’s mental health difficulties have improved, an ending of support after a period in which a young person has not experienced improvements in their mental health (Bear et al., 2020; Edbrooke -Child’s et al., 2018), or when they have reached the upper age limit for their service (Singh et al., 2010).

Most discharge literature to date has focused on the latter reason for care ending. This is known as the transition boundary and occurs around the ages of 16–18 (Paul et al., 2018). If there are continuing mental health needs, CYP should transition to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS) (Appleton et al., 2022). However, there is a wealth of research indicating that this transition is a negative experience for the majority of young people (Broad et al., 2017; Hovish et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2010), and only around a quarter of young people transition due to a combination of factors including long waiting lists, higher eligibility thresholds and scarcity of resources (Appleton et al., 2019; Newlove-Delgado et al., 2019). However, if a young person does not meet the illness threshold for AMHS, or if adult services are not best suited to meet their clinical needs, alternative forms of support should be available, avoiding an inappropriate transition (Paul et al., 2018). Thus, being discharged is a beneficial option for many young people, underscoring the need for a well-managed pathway.

Previous research has found that the majority of young people are discharged to their GP after reaching the CYPMHS age boundary (Appleton et al., 2019) however this is poorly managed with many young people reporting a disjointed experience with unmet health needs (Appleton et al., 2022). This could be due to multitude of factors including scarcity of resources and insufficient training for GPs (Hinrichs et al., 2012; Newlove-Delgado et al., 2019). The remaining three quarters of CYP open to CYPMHS will follow other discharge routes, with their lead clinician needing to liaise with local voluntary sector services to find a suitable provider for ongoing support alongside by GPs if further “sub AMHS threshold” mental health support is required.

Whilst there have been several recent studies on the CYPMHS – AMHS transition pathway, there has been less research focused on discharging CYP from CYPMHS prior to the transition age boundary. Community CYPMHS is a specialist service, for which there is high demand resulting in lengthy waiting lists (Islam et al., 2016; Punton et al., 2022; Rocks et al., 2020; Valentine et al., 2023), therefore it is important that use of this finite resource is reserved for those who have a clear and ongoing need for it. Being discharged is a beneficial option both for the service (as this allows clinicians to see the next CYP on the waiting list), and the young person, signifying that the CYPs treatment is at an end, potentially due to them having a significant reduction in their emotional distress and a set of coping skills that will enable them to maintain their recovery.

Earlier discharge may be beneficial and avoid a more sudden end to CYPMHS care at the transition boundary. For example, Gerritsen et al. (2022) questioned whether some young people could have been discharged before they reached the transition boundary given the continued improvement of mental-health difficulties after leaving CYPMHS. This was relevant for almost half of CYP in the study who did not stay in CYPMHS or transition after reaching the boundary, underscoring the need to look at discharge planning rather than solely focusing on transitional care. However, it would be beneficial to explore how clinicians experience discharging a young person from the service. This is important, as if we can begin to understand this experience we may be able to begin creating a more positive and productive pathway for young people and those working within services.

Therefore, this study aims to develop a more comprehensive understanding of discharge by interviewing community CYPMHS clinicians about the barriers and facilitators of discharging CYP. We define ‘discharge’ as the managed process which involves planning for a young person’s care at – CYPMHS coming to an end for any reason, which includes, but is not limited to, young people reaching the upper age limit for the service. This will help us understand what factors contribute to this poorly managed pathway, and how it can be improved.

Methods

This study is reported following the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O’Brien et al., 2014).

Participants and Procedures

Staff members were recruited purposively (Robinson, 2014) in order to generate a diverse sample across various professionals to help represent a wider range of views in our study. All participants had to have experience working with CYP at CYPMHS to be eligible to take part.

Members of the research team sent out email invitations via their personal networks to provide information about the study to eligible staff. The email contained the participant information sheet and details on how to respond if they were interested in taking part. The study was also advertised on social media platforms such as X (Twitter).

We aimed to recruit around 10–15 participants for the study. This was guided by Hennink and Kaiser’s (2022) systematic review in which they reported that 9–17 interviews were enough to capture most relevant concepts and pragmatic considerations regarding the study timeline.

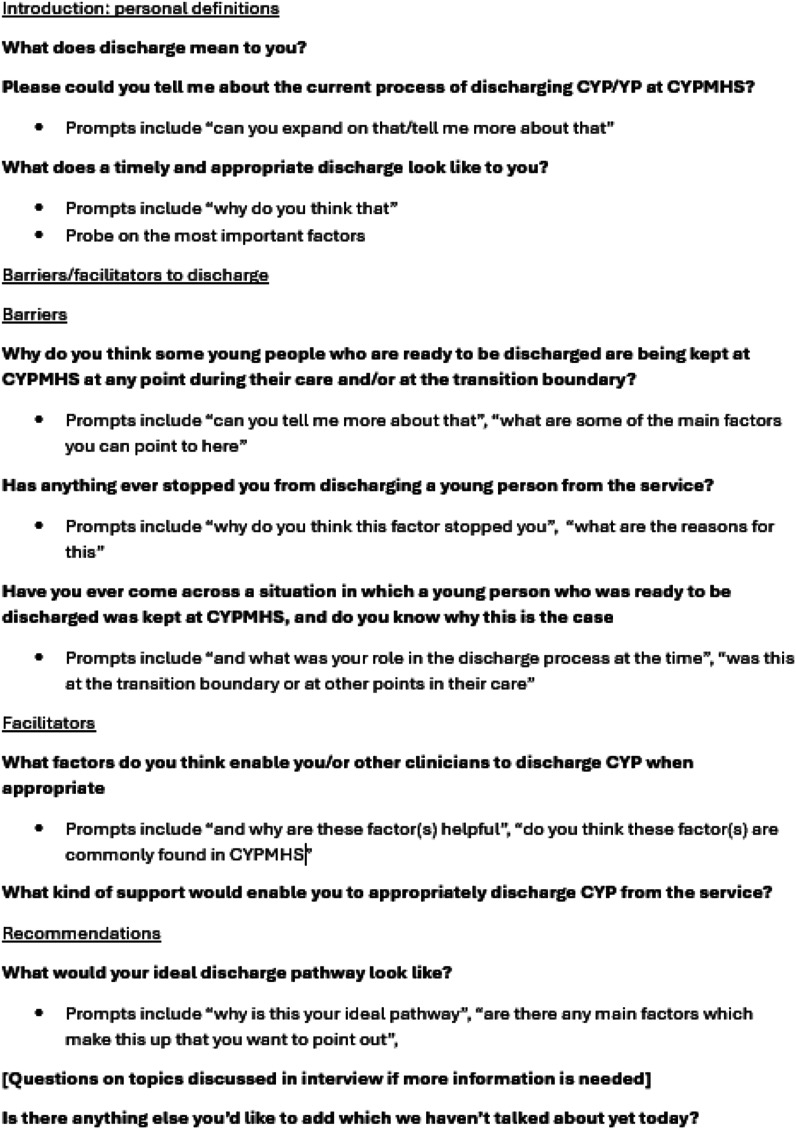

Semi-structured interviews were conducted and audio-recorded. The interview topic guide (see Figure 1) was collaboratively developed in advance by the research team. Interviews took place over Microsoft Teams. Informed written consent was taken from all participants prior to the interviews.

Figure 1.

Interview Topic Guide.

Analysis

The audio recordings were anonymised and transcribed verbatim. They were analysed using codebook thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022) within NVivo 12 software. An initial codebook was developed based on our study objectives and further refined from the themes emerging from the analysis. The final codebook was developed after agreement from all the authors.

Themes were developed starting with data familiarisation which included reading and re-reading of the transcripts. To acquire an overview of the most prominent content, participant quotes and semantic codes were organised inductively. Latent codes were then investigated and organised. We, then reviewed the connections between these codes, which enabled higher order inductive themes to be generated. Finally, sub-themes were identified and developed before these were reviewed, re-organised, defined and titled.

Quality

Instead of utilizing concepts which demonstrate quality in quantitative research, such as reliability and generalizability (Tobin & Begley, 2004), we sought to improve the trustworthiness of our thematic analysis. For example, we made efforts to actively engage with and immerse ourselves with the dataset, used a reflective journal as a means of establishing an audit trail and held biweekly research meetings to allow time for peer debriefing (Nowell et al., 2017). Additionally, the data was analysed by more than one researcher in order to enhance credibility (Côté & Turgeon, 2005). Finally, we sought confirmability by demonstrating that our findings are clearly derived from the data by including verbatim quotes from the transcripts.

Reflexivity

SS led this study as part of her MSc. As she was previously unfamiliar with this field, this may have impacted her ability to identify subtle expressions of themes which are clear to an “insider” (Berger, 2015). To manage this, SS was supported by RA, an experienced qualitative researcher with a background in CYP mental health research and SB, a CYPMHS mental health nurse and researcher. The team regularly discussed any topics that SS needed clarification on, and reviewed themes/codes together.

A reflexive journal was also kept in which we recorded our personal reflections/insights and methodological decisions, which helps minimise the impact of researcher biases and acts as a self-critical account (Tobin & Begley, 2004).

Results

In total, 12 participants took part in the study.

All participants were females. The most predominant profession was primary mental health workers (33.3%). Most participants had worked in CYPMHS for multiple years, except for two clinicians who had been there for just under a year (16.7%). Full participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Interviews took place between June and August 2023 and lasted between 30 and 40 minutes.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

| Participant Number | Gender | Profession | Years of experience in CYPMHS | NHS Trust | NHS Band |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | Primary mental Health worker | 5 | ELCAS | 7 |

| 2 | Female | Educational mental Health practitioner | 2 | ELCAS | 5 |

| 3 | Female | Community practitioner | 7 | CNTW | 6 |

| 4 | Female | Occupational therapist | 4 | CNTW | 6 |

| 5 | Female | Assistant psychologist | 2.5 | NSFT | 4 |

| 6 | Female | Non-medical prescriber and nurse specialist | 7 | CNTW | 7 |

| 7 | Female | Primary mental Health worker | 11 | ELCAS | 7 |

| 8 | Female | Primary mental Health worker | 17 | ELCAS | 7 |

| 9 | Female | Primary mental Health worker | 10 | ELCAS | 6 |

| 10 | Female | Specialist nurse | Under a year | CNTW | 7 |

| 11 | Female | Occupational therapist | 1 | CNTW | 6 |

| 12 | Female | Clinical psychologist | Under a year | Covwarkpt | 7 |

CNTW = Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear, ELCAS = East Lancashire Child and Adolescent Services, NSFT = Norfolk and Suffolk Foundation Trust, Covwarkpt = Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership NHS Trust.

Themes

Six themes were identified: “perfectionistic approach towards treatment outcomes”, “reducing dependence on CYPMHS through empowerment”, “a lack of flexibility in the wider system”, “lack of collaborative care”, “an increasing pressure on the service” and “keeping the focus on discharge”. All themes are discussed below

Perfectionistic approach towards treatment outcomes

Participants spoke about how at times clinicians, parents and third-sector organisations can hold a “perfectionistic” approach towards treatment outcomes which means they expect the child to be “all happy and normal again” (P10 Specialist Nurse) by the end of treatment, and where this is not met the CYP is kept back in CYPMHS.

For example, clinicians expressed that, “You might, as a practitioner, also seek this perfection. That can be a real barrier. There’s still something to work on so let’s keep going” (P5 Assistant Psychologist). A similar attitude was found amongst parents, “often it’s hard to discharge young people, because parents feel there is a need for more sorting to happen…they want the child to be fully fixed or cured” (P9 Primary Mental Health Worker). Third-sector organisations also expressed a perfectionistic attitude, “they can be very vocal that young people need to remain within our service because their difficulties have not been completely resolved” (P9 Primary Mental Health Worker). Thus, the perfectionistic desire to resolve all the CYPs difficulties is perceived as an important barrier to discharging young people.

However, the participants recognised that this was an unrealistic expectation as it is likely that many young people will have some continuing mental health difficulties, but the aim is to help them manage these difficulties without professional support. Therefore, many felt that there needed to be better and earlier psychoeducation for families and staff around what to expect from CYPMHS:

“Maybe a better leaflet of expectations of the service because we have this expectation that they’re going to come out happy, cured and never self-harm again. Actually, a realistic expectation is that they’re not always going to be happy, and some might self-harm … but that doesn’t mean we’ve failed” (P10 Specialist Nurse)

Therefore, although having a perfectionistic attitude was identified as a barrier to discharging young people, managing expectations and improved psychoeducation were viewed as facilitators.

Reducing dependence on CYPMHS through empowerment

This theme is split into two sub-themes, namely “becoming dependent on CYPMHS” and “empowering families and young people “, which are both explained in more detail below.

Becoming dependent on CYPMHS

Participants felt that for young people CYPMHS can become like a “security blanket” (P5 Assistant Psychologist), and they become “quite dependent within the regular sessions” (P9 Primary Mental Health Worker). This is accompanied by a diminished confidence in their own abilities as “they fear they will be left to their own devices” (P9 Primary Mental Health Worker). Similarly, staff spoke about how parents were often “wanting more support…because its comfortable and they want their child to be looked after” (P3 Community Practitioner) implying a sense of dependence on CYPMHS to look after their child's difficulties rather than themselves. In fact, participant experienced that “parents become a little bit frightened about services stepping out and having to manage everything themselves” (P8 Primary Mental Health Worker).

Therefore, although this dependence facilitates treatment (e.g., coming to appointments regularly), it may also become detrimental as their time in the service is coming to an end.

To resolve this challenge, participants suggested strategies to empower families and young people by helping them to recognise their own resources and abilities, hence reducing dependence on CYPMHS to look after them. This is described in the sub-theme below.

Empowering families and young people

Participants discussed how they helped build parent’s confidence by asking them to think about the skills/resources they already had, “Right, okay, how can we build on those foundations, build on those parenting skills, that confidence that you’ve got in being a mum, a carer, a father, to be able to move forward out of mental health services?” (P8 Primary Mental Health Worker). This was alongside letting them “know exactly how they were going to be supported” (P3 Community Practitioner) by other services and making them aware that “if they want to refer back in, then it’s an option” (P2 Education Mental Health Practitioner).

Clinicians also stressed the importance of involving young people in their care because “If they are involved in their care, if they participate, they can see why they need to be discharged, that empowers them and makes them feel better about discharge” (P3 Community Practitioner). Additionally, allowing them to physically see the progress they have made can enable them to feel prepared to leave CYPMHS, “then another point is we review their goals every week because it’s quite structured, the children themselves can see when they're going to be discharged…you can actually help them with coming to an end” (P2 Education Mental Health Practitioner).

Therefore, whereas a sense of dependence was considered a barrier to discharge, empowering families to build confidence in themselves was a facilitator.

A Lack of flexibility in the wider system

The wider system refers to the third-sector organisations that CYP can be discharged to after their care at CYPMHS ends.

Firstly, staff spoke about how these services can have quite strict entry criteria for accepting referrals from CYPMHS. This can be seen in cases of self-harm and/or previous suicide attempts, “So for example, if there’s like self-harm in the past, they may not accept them, but then maybe the last time they self-harmed was quite a while ago and they’re managing them quite well” (P12 Clinical Psychologist). Thus, clinicians can feel they need to hold onto young people whose clinical needs no longer warrant a CYPMHS referral.

Similarly, staff felt that these services do not easily take on cases in which trauma is mentioned, “As soon as trauma gets mentioned it’s like, “Well it must be the trauma…Services won’t touch it” (P10 Specialist Nurse). In some cases, participants stated that CYP are unable to access services if they are open to CYPMHS for medication reviews, “the medication is a real big thing. Sometimes .. If they’re staying under a doctor for medication, they can’t go and access other things because they’re open to CYPMHS” (P5 Assistant Psychologist).

Therefore, participants expressed finding third-sector services have strict criteria around what type of young person they will accept, which may contribute to the low numbers of CYPs referred to them. Additionally, participants felt that other organisations such as schools struggled to adapt to the young person’s needs implying a lack of flexible care, “we get pressure from schools saying that “You can't discharge them and we can’t still offer this bespoke service and keep all the adaptations if a secondary specialist mental health team isn't involved” (P4 Occupational Therapist). These adaptations included having reduced timetable or smaller class sizes. This may hinder timely discharge due to the inevitable back-and-forth discussions between CYPMHS and schools about whether and how adaptations can be made.

Therefore, a key recommendation was that instead of expecting young people to mould into services, we need “flexible services that can almost mould to the young person” (P1 Primary Mental Health Worker). Indeed strategies which honed this principle, such as offering different treatment options, and allocating staff cases according to their skillsets were identified as facilitators for discharge, “so if you allocate based on staff skills they’re going to be able to do an intervention better” (P3 Community Practitioner).

“You've also got to be mindful it might not be the right therapy for them… we can step it up if we need to, to high intensity or children's psychology…Suggest Kooth (online organisation providing free mental health support and counselling to CYP)…that facilitates the discharge process as well” (P2 Education Mental Health Practitioner),

Lack of collaborative care

Participants spoke about the lack of communication internally within CYPMHS (e.g., between staff members and with families), and externally (e.g., with voluntary sector organisations). For example, staff expressed how “sometimes the young people don’t know when they’re going to be discharged or have any clue about it” (P11 Occupational Therapist). This is likely to cause problems, for example if an unprepared young person finds out about their discharge quite late, this could trigger a relapse and further delay the process. This may be especially true for those with trauma or attachment issues who could feel quite rejected. Also, participants spoke about the poor connections between CYPMHS and voluntary sector organisations, for example “services might be kind of disjointed I mean a lot of services” (P7 Primary Mental Health Worker). Thus, this poor communication between services means that any important referrals or support systems which should be in place well before discharge are not, inevitably delaying the discharge of CYP who require these as they leave CYPMHS.

Following this, participants reported good channels of communication between all parties as a facilitator. For example, clear communication with other services, “Communication is absolutely important, making sure that all professional services which are involved with that young person are aware of our assessment” (P8 Primary Mental Health Worker), and with families was viewed as key factors to ensuring timely discharges, “for me it would be in consultation with the young person and their family, do they feel okay to be discharged” (P1 Primary Mental Health Worker).

Finally, participants reported that the use of multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs) could help ensure clear communication and joint working within CYPMHS. These meetings allowed clinicians to talk to other staff members who are also involved in the CYP’s care within one space, and solve any concerns which might be hindering discharge, “a young person might be at a point of discharge, but there is something that you need to clarify, you need an MDT eye...you can just go and talk through it”. Additionally, if other staff members agreed with their decision to discharge it reassured clinicians that they were doing the right thing, “working as part of an MDT can really help because you kind of discussed it … where it feels ok this is not just my decision here, other people are in agreement” (P12 Clinical Psychologist). Paradoxically, a challenge to holding MDTs can be the availability of those involved, particularly when caseloads and working lives are so busy.

An increasing pressure on the service

Participants discussed the effects of lengthy waiting lists at CYPMHS on discharge, “the waiting times are so long that you feel uncomfortable almost discharging them knowing that they’re going to have such a lengthy wait for intervention if they need to come back” (P1 Primary Mental Health Worker). Similarly, due to long waiting times at external services staff held onto CYP until they were seen there, “suppose we’re trying to plug a gap as well … We’re doing low intensity, and they may need an ADHD or autism assessment. You feel, if I discharge them now, they’re going to have a whole year on a waiting list. … I suppose that holds the discharge process up a bit then” (P2 Educational Mental Health Practitioner). Thus, clinicians’ concerns that the CYP’s mental health could worsen in the waiting period was an important barrier to discharging CYP.

Also, due to high levels of staff burnout which causes them to leave CYPMHS, participants expressed high rates of staff turnaround: “Staff turnaround is huge… I absolutely envision that the new person coming in will probably do their own assessment, start again, and probably end up keeping them half a year just because, as a clinician, you’re going to want to make sure you’re content with that plan” (P10 Specialist Nurse). Therefore, instead of picking up from the same place, the new clinician may begin their own treatment plan delaying the CYP’s discharge. Finally, participants discussed how time pressures and high caseloads meant they were more likely to put off an already lengthy discharge process, “I think a lot of the barriers is that there's a lot of work that comes with discharge so you probably avoid doing it because it’s easier to keep people than it is to have a whack load of work to do” (P10 Specialist Nurse).

In response to these challenges, participants called for more investment as a lot of these things are “down to funding” [P6 non-medical prescriber and nurse specialist] which ensures “smaller caseloads” (P10 Specialist Nurse), high staff retention rates and smaller waiting lists.

Keeping the focus on discharge

Participants also spoke for the need for more open and frequent discussions about discharge in their workplace, “Maybe if there was more open discussion about it… I don’t think we talk about discharge a lot… it’s not part of day-to-day our dialogue” (P5 Assistant Psychologist). Thus, it seems that discharge may not be a priority within all CYPMHS, and so staff in these services may be less likely to think about it. In fact, this absence could instil a negative attitude towards the process, rather than make it feel positive and recovery oriented. Additionally, clinicians felt that due to high caseloads and time pressures, they had less time to think about discharging as they continued their appointments, “Time pressures mean you don't have that reflective space to think about it” (P1 Primary Mental Health Worker).

However, participants also spoke about some factors that helped retain the focus on a timely discharge. Firstly, they felt good supervision was one in which there was a reflective space and accountability in relation to discharge, “They can come in and say, “Look, you’ve had 100 appointments, what are you still doing? What could you possibly still be doing? If you still need to be doing it, it’s not working. So where do we go from here?” (P10 Specialist Nurse).

Secondly, clinicians emphasised the role of regularly reviewing treatment goals, as it helped them recognise whether the original therapy goals have been met. If they had, this indicates that they should start discussing discharge rather than continue to work on other things, “So we start off with a goal-based outcome…Once we’ve achieve them we’ll be looking towards discharge and you can check are you still addressing what the young person came into service for or found yourself going off on a tangent?” (P5 Assistant Psychologist). Considering this participants recommended that staff should be given more “clarity on why we do goal-based outcomes” (P10 Specialist Nurse) and also be trained on how to set suitable goals which are smaller because “if you raise the bar too high, you can always feel like you're not succeeding” (P4 Occupational Therapist).

Discussion

This study aimed to understand clinicians experiences of discharging CYP from CYPMHS whatever the discharge destination and, specifically the barriers and facilitators they faced whilst doing so.

We found that discharges can be delayed at any age while in CYPMHS due to a number of factors. Clinicians, parents and voluntary sector organisations can hold a “perfectionistic” attitude, where they may delay discharge until they are satisfied that all of the young person’s mental health difficulties have been resolved. Families can also become very dependent on CYPMHS and be reluctant for their child to leave the service.

Additional barriers to discharge included a lack of flexibility in the system and poor communication between all relevant parties. Lengthy waiting lists also made clinicians uncomfortable about discharging CYP, whilst high staff turnover caused further delays.

There are multiple, complicated factors maintaining the status quo of challenge within and around the community CYPMHS system. This has led to challenges in the discharge process for clinicians, CYP, and their families.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is the diverse sample, which included clinicians from varying professional backgrounds, NHS Trusts and levels of clinical experience which ensured that a range of views and experiences were represented. This study represents the beginning of what will hopefully become an emerging field of research attempting to understand the complexities around discharging young people from community CYPMHS.

However, several limitations should be noted.

In terms of our sample, although there was some diversity in NHS Trusts, most participants came from two services. Due to the variability in resources, charitable support and waiting times (Stafford et al., 2020) and funding (Bowles et al., 2023) staff in other trusts may experience different pressures which are not represented in our findings. Additionally, interviewing a varied selection of staff, for example family therapists, psychiatrists, psycho-dynamic therapists and those in nurse management positions could also bring forth new perspectives. We did not collect information from participants on the type of CYPMHS they worked for, which may have helped to identify barriers at particular types of services. Thirdly, interviewing a larger sample, including male clinicians may have been beneficial to achieve a wider range of views.

There may also have been selection bias present in our study as clinicians voluntarily came forth to participate, who may have been more likely to hold more positive or negative views.

Comparison with existing literature

It has been recognised that clinicians in other fields can sometimes have unhealthy amounts of perfectionism in relation to their patients care (Peters & King, 2012), mirroring the experiences of CYPMHS clinicians in our study. Additionally, our findings around families expecting their children to be “fixed or cured” can also be found in the family therapy literature for example O’Reilly (2015) found that parents often expressed a desired outcome of “fixing” their child during therapy. However, this can have adverse consequences as this positions the child as the problem and blames them for their mental health difficulties (Asen, 2002; O’Reilly 2005; Parker & O’Reilly, 2012). Findings from one study which interviewed clinicians and CYP from CYPMHS aligned with the current research, in that it reported that there is an expectation that services struggle to manage parents’ expectations and feel as those they should ‘cure’ CYP of all their problems (Bear et al., 2021).

Our findings around parents feeling anxious or fearful when leaving CYPMHS has also been previously reported (Appleton et al., 2021; Dalzell et al., 2018). For example, Appleton et al. (2021) found that parents whose children had not transitioned to AMHS, saw CYPMHS as a “safety net” and worried about what would happen in the future. Similarly, parents of children who did eventually transition to AMHS reported concerns around having to leave the secure relationships they had developed in CYPMHS (Lindgren et al., 2014; McNamara et al., 2017; Richards & Vostanis, 2004). Previous literature also indicates that young people leaving CYPMHS often feel very anxious and uncertain about their ability to cope (Dalzell et al., 2018; Dunn, 2017) which is in line with our findings.

Additionally, clinicians in our study expressed that parents are anxious about having to manage everything themselves if their child is discharged. Indeed, these fears are not unfounded as previous studies indicate that parents whose children were discharged from CYPMHS, or were waiting for AMHS, found themselves juggling multiple financial, emotional and social responsibilities which went beyond what is usual for a parent-child relationship (Appleton et al., 2022; Lockertsen et al., 2021).

Our theme of a fragmented care system is also reflected multiple times in the literature, where clinicians cite a lack of communication between CYPMHS and AMHS (McNamara et al., 2017; Reale & Bonati, 2015), GPs (Appleton et al., 2021, 2022) and with schools (Rothi & Leavey, 2006). Across many studies, increased joining up of services is recommended to improve the transition and discharge process (Broad et al., 2017; Hill et al., 2019; Richards & Vostanis, 2004; Singh et al., 2010). In addition, findings relating to lengthy waiting lists as a barrier to discharge (Bear et al., 2021; Dalzell et al., 2018) and high staff turnaround and burnout in CYPMHS (Doody et al., 2021) have been reported elsewhere.

Finally, the literature has long acknowledged that the current mental healthcare system is inflexible (Mughal & England, 2016), which corroborates our findings. The findings from, our study illustrate how this inflexibility in the wider system can negatively impact the discharge process and so may result in increased pressures on CYPMHS.

Implications for research and practice

Firstly, there is an important need to help manage the expectations of clinicians, young people and their families. For example, services should help staff and patients understand that the aim of treatment is not to make sure all CYPs mental health difficulties have been resolved but to help them manage these in a safe and effective way. This can be done by making it a part of early conversations with CYP and families and introducing it in training sessions with staff. Clinicians should also help build families’ self-confidence from the beginning of treatment using the techniques mentioned by participants in our study. This would reduce the anxiety families feel as they are approaching the end of treatment, while at the same time building clinician confidence to close cases. CYPMHS should also ensure that there is space for discharge within their services, through the wider implementation of factors mentioned by our participants such as supervision and teaching staff how to use treatment goals appropriately. Finally, unhealthy perfectionism in clinicians can be tackled using techniques such as teamworking, constructive feedback and coaching. These strategies can help identify the relevant staff members and provide them with alternative ways of working (Peters & King, 2012).

As put forth by participants under the theme of “an increasing pressure on the service”, it is likely that increased investment in CYPMHS would provide a longer-term solution to address multiple barriers by increasing the number of clinicians, reducing waiting times, caseloads and staff turnover.Indeed, CYPMHS is currently described as the “Cinderella of the Cinderella Services” (Mughal & England, 2016, p. 502) by being chronically underfunded and undervalued (Mughal & England, 2016) and, funding has stagnated despite apparent commitments to increase investment (Lambert et al., 2020). Investing in more voluntary sector services is helpful however it is more important to ensure that their entry criteria are not similarly restrictive otherwise the system will remain inflexible (Holding et al., 2022; Wright & Richardson, 2020). Finally, joint working between relevant parties, such as GPs, social workers, voluntary sector services, schools and CYPMHS should be a priority to provide good continuity of care to CYP. MDTs were recognised as being especially beneficial in this regard, however this needs to be balanced alongside considerations around staff availability for these meetings given their high caseloads.

Future research should explore whether our findings are replicable in larger and more diverse samples, which will help establish whether they represent the majority of CAMHS clinicians’ experiences. It is also crucial to examine young people’s and parents experiences of being discharged from CYPMHS, as this study only gathered family-related factors through clinician’s viewpoints. The same applies to third-sector services so we can better understand the challenges they face whilst accepting CYPMHS referrals. Finally, future research should investigate how our recommendations can be implemented, for example how an effective training programme can be delivered to clinicians at CYPMHS and elsewhere.

Conclusion

This study adds to existing literature regarding clinicians’ experiences of discharging CYP from CYPMHS, specifically the barriers and facilitators to doing so. It highlights the need for a more joined up approach across different services to ensure good continuity of care for CYP and to make sure they are receiving support from the service best placed to meet their needs. Our findings also indicate that CYPMHS clinicians face multiple systemic barriers to discharge, and that discharge could be facilitated through the use of goal-setting and managing both CYP and families’ expectations of the support which can be offered by the service.

However, these recommendations cannot be implemented without significant changes in current policies and clinical practice. Future research with CYP, families ,voluntary sector organisations and a wider selection of CYMPHS staff is needed in order to understand their concerns and views on how the discharge process from CYPMHS should be improved. It is vital that services focus on ensuring timely, safe and well-managed discharges, which take the needs of all CYP into consideration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the clinicians who took part in our study.

Author biographies

Shadab Shahid, MSc, was based in the Division of Psychiatry, University College London, before relocating to complete psychological well-being training in the NHS. This study was her MSc project.

Trinity De Simone, MSc, was based in the Division of Psychiatry, University College London before relocating to work as an assistant psychologist at The Havens, a pan-London NHS SARC.

Rebecca Appleton, PhD, Senior Research Fellow in the Mental Health Policy Research Unit at UCL. Research interests: young people's mental health, implementation science, mental health policy.

Sarah Bisp, MSc, PhD candidate, is an Assistant Professor of Mental Health Nursing in the School of Healthcare and Nursing Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle. Her research interests centre on children and young people’s mental health and person-centred care.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

Ethical considerations

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was received from the UCL Research Ethics Committee (Ethics ID Number: 25187/001).

Consent to participate

Informed written and verbal consent was obtained from all participants prior to conducting the interviews.

Consent to publication

Consent for publication was obtained for every individual persons data included in the study.

ORCID iDs

Shadab Shahid https://orcid.org/0009-0003-5597-4830

Sarah Bisp https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8691-5006

Data Availability Statement

We did not ask for written consent from participants to share their data, therefore supporting data is not available.

References

- Appleton R., Connell C., Fairclough E., Tuomainen H., Singh S. P. (2019). Outcomes of young people who reach the transition boundary of child and adolescent mental health services: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(11), 1431–1446. 10.1007/s00787-019-01307-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleton R., Elahi F., Tuomainen H., Canaway A., Singh S. P. (2021). “I’m just a long history of people rejecting referrals” experiences of young people who fell through the gap between child and adult mental health services. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(3), 401–413. 10.1007/s00787-020-01526-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleton R., Loew J., Mughal F. (2022). Young people who have fallen through the mental health transition gap: A qualitative study on primary care support. British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 72(719), e413–e420. 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asen E. (2002). Outcome research in family therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8(3), 230–238. 10.1192/apt.8.3.230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bear H. A., Dalzell K., Edbrooke-Childs J., Garland L., Wolpert M. (2021). How to manage endings in unsuccessful therapy: A qualitative comparison of youth and clinician perspectives. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 32(2), 249–262. 10.1080/10503307.2021.1921304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear H. A., Edbrooke-Childs J., Norton S., Krause K. R., Wolpert M. (2020). Systematic review and meta-analysis: Outcomes of routine specialist mental health care for young people with depression and/or anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(7), 810–841. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. 10.1177/1468794112468475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., Clifford D., Mohan J. (2023). The place of charity in a public health service: Inequality and persistence in charitable support for NHS trusts in England. Social Science & Medicine, 322(3), Article 115805. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broad K. L., Sandhu V. K., Sunderji N., Charach A. (2017). Youth experiences of transition from child mental health services to adult mental health services: A qualitative thematic synthesis. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12888-017-1538-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté L., Turgeon J. (2005). Appraising qualitative research articles in medicine and medical education. Medical Teacher, 27(1), 71–75. 10.1080/01421590400016308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I., McNamara N., Healy M., Gower C., Sarkar M., McNicholas F. (2015). Adolescents’ and parents’ views of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) in Ireland. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(8), 561–569. 10.1111/jpm.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalzell K., Garland L., Bear H., Wolpert M. (2018). In search of an ending: Managing treatment closure in challenging circumstances in child mental health services. [Google Scholar]

- Doody N., O’Connor C., McNicholas F. (2021). Consultant psychiatrists’ perspectives on occupational stress in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). Irish Journal of Medical Science, 191(3), 1–9. 10.1007/s11845-021-02648-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn V. (2017). Young people, mental health practitioners and researchers co-produce a Transition Preparation Programme to improve outcomes and experience for young people leaving Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s12913-017-2221-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbrooke-Childs J., Wolpert M., Zamperoni V., Napoleone E., Bear H. (2018). Evaluation of reliable improvement rates in depression and anxiety at the end of treatment in adolescents. BJPsych Open, 4(4), 250–255. 10.1192/bjo.2018.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen S. E., Van Bodegom L. S., Overbeek M. M., Maras A., Verhulst F. C., Wolke D., Rizopoulos D., De Girolamo G., Franić T., Madan J., McNicholas F., Paul M., Purper-Ouakil D., Santosh P. J., Schulze U. M. E., Singh S. P., Street C., Tremmery S., Tuomainen H., MILESTONE consortium . (2022). Leaving child and adolescent mental health services in the MILESTONE cohort: A longitudinal cohort study on young people's mental health indicators, care pathways, and outcomes in Europe. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(12), 944–956. 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00310-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink M., Kaiser B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292(6), Article 114523. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A., Wilde S., Tickle A. (2019). Transition from child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) to adult mental health services (AMHS): A meta‐synthesis of parental and professional perspectives. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(4), 295–306. 10.1111/camh.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs S., Owens M., Dunn V., Goodyer I. (2012). General practitioner experience and perception of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) care pathways: A multimethod research study. BMJ Open, 2(6), Article e001573. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holding E., Crowder M., Woodrow N., Griffin N., Knights N., Goyder E., McKeown R., Fairbrother H. (2022). Exploring young people's perspectives on mental health support: A qualitative study across three geographical areas in England, UK. Health and Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e6366–e6375. 10.1111/hsc.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovish K., Weaver T., Islam Z., Paul M., Singh S. P. (2012). Transition experiences of mental health service users, parents, and professionals in the United Kingdom: A qualitative study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(3), 251–257. 10.2975/35.3.2012.251.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z., Ford T., Kramer T., Paul M., Parsons H., Harley K., Weaver T., McLaren S., Singh S. P. (2016). Mind how you cross the gap! Outcomes for young people who failed to make the transition from child to adult services: The TRACK study. BJPsych Bulletin, 40(3), 142–148. 10.1192/pb.bp.115.050690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert A. K., Doherty A. J., Wilson N., Chauhan U., Mahadevan D. (2020). GP perceptions of community-based children’s mental health services in Pennine Lancashire: A qualitative study. BJGP Open, 4(4), Article bjgpopen20X101075. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren E., Söderberg S., Skär L. (2014). Managing transition with support: Experiences of transition from child and adolescent psychiatry to general adult psychiatry narrated by young adults and relatives. Psychiatry Journal, 2014(1), Article 457160. 10.1155/2014/457160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockertsen V., Holm L. A. W., Nilsen L., Rø Ø., Burger L. M., Røssberg J. I. (2021). The transition process between child and adolescent mental services and adult mental health services for patients with anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study of the parents’ experiences. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s40337-021-00404-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara N., Coyne I., Ford T., Paul M., Singh S., McNicholas F. (2017). Exploring social identity change during mental healthcare transition. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(7), 889–903. 10.1002/ejsp.2329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas F., Reulbach U., Hanrahan S. O., Sakar M. (2016). Are parents and children satisfied with CAMHS? Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 33(3), 143–149. 10.1017/ipm.2015.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mughal F., England E. (2016). The mental health of young people: The view from primary care. British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 66(651), 502–503. 10.3399/bjgp16X687133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlove-Delgado T., Blake S., Ford T., Janssens A. (2019). Young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in transition from child to adult services: A qualitative study of the experiences of general practitioners in the UK. BMC Family Practice, 20(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s12875-019-1046-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell L. S., Norris J. M., White D. E., Moules N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), Article 1609406917733847. 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien B. C., Harris I. B., Beckman T. J., Reed D. A., Cook D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(9), 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly M. (2005). “What seems to be the problem?” A myriad of terms for mental health and behavioral concerns. Disability Studies Quarterly, 25(4). 10.18061/dsq.v25i4.608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly M. (2015). ‘We’re here to get you sorted’: Parental perceptions of the purpose, progression and outcomes of family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy, 37(3), 322–342. 10.1111/1467-6427.12004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker N., O’Reilly M. (2012). ‘Gossiping’ as a social action in family therapy: The pseudo-absence and pseudo-presence of children. Discourse Studies, 14(4), 457–475. 10.1177/1461445612452976 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M., O’hara L., Tah P., Street C., Maras A., Ouakil D. P., Santosh P., Signorini G., Singh S. P., Tuomainen H., McNicholas F., MILESTONE Consortium . (2018). A systematic review of the literature on ethical aspects of transitional care between child-and adult-orientated health services. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12910-018-0276-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M., King J. (2012). Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ, 344, Article e1674. 10.1136/bmj.e1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punton G., Dodd A. L., McNeill A. (2022). ‘You’re on the waiting list’: An interpretive phenomenological analysis of young adults’ experiences of waiting lists within mental health services in the UK. PLoS One, 17(3), Article e0265542. 10.1371/journal.pone.0265542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale L., Bonati M. (2015). Mental disorders and transition to adult mental health services: A scoping review. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 30(8), 932–942. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M., Vostanis P. (2004). Interprofessional perspectives on transitional mental health services for young people aged 16–19 years. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 18(2), 115–128. 10.1080/13561820410001686882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. 10.1080/14780887.2013.801543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocks S., Glogowska M., Stepney M., Tsiachristas A., Fazel M. (2020). Introducing a single point of access (SPA) to child and adolescent mental health services in England: A mixed-methods observational study. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12913-020-05463-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothi D., Leavey G. (2006). Child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and schools: Inter‐agency collaboration and communication. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 1(3), 32–40. 10.1108/17556228200600022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. P., Paul M., Ford T., Kramer T., Weaver T., McLaren S., Hovish K., Islam Z., Belling R., White S. (2010). Process, outcome and experience of transition from child to adult mental healthcare: Multiperspective study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 197(4), 305–312. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford J., Aurelio M., Shah A. (2020). Improving access and flow within child and adolescent mental health services: A collaborative learning system approach. BMJ Open Quality, 9(4), Article e000832. 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin G. A., Begley C. M. (2004). Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(4), 388–396. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine A. Z., Sayal K., Brown B. J., Hall C. L. (2023). A national survey of current provision of waiting list initiatives offered by child and adolescent mental health services in England. British Journal of Child Health, 4(2), 78–83. 10.12968/chhe.2023.4.2.78 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright B., Richardson G. (2020). How ‘Together We Stand’ transformed the local delivery of mental health services. Health Service Journal, 19. [online] . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We did not ask for written consent from participants to share their data, therefore supporting data is not available.