Abstract

Objective.

To map the literature on the prevalence of pain in nursing professionals.

Methods.

This is a scoping review that was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews, and according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The protocol was developed and registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) [https://osf.io/2zu73/]. The search was carried out in the following databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Virtual Health Library (VHL), Web of Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), SciVerse Scopus, Embase, and the Catalog of Theses and Dissertations of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Results.

A total of 49 studies were included, all of which were cross-sectional studies, and the total sample of the included studies was 35,069 participants. Most of the included studies were concentrated in the Asian continent (71.4%). Among the selected studies, it was shown that the most affected area was the lumbar region (81.57%), followed by the neck (71.5%) and shoulder (31.57%) regions.

Conclusion.

According to the studies evaluated, the prevalence of occupational pain in nursing professionals was of musculoskeletal origin. The high prevalence of pain found reinforces the importance of monitoring the health of nursing workers.

Descriptors: pain, nursing professionals, occupational diseases.

Resumen

Objetivo.

Mapear la literatura científica sobre la prevalencia del dolor en los profesionales de enfermería.

Métodos.

Se trata de una revisión de alcance que se llevó a cabo de acuerdo con las metodologías del Instituto Joanna Briggs y con la extensión de la guía PRISMA. El protocolo se elaboró y registró en el Open Science Framework (OSF) [https://osf.io/2zu73/]. La búsqueda se realizó en las siguientes bases de datos: PubMed/MEDLINE, Biblioteca Virtual de Salud (BVS), Web of Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), SciVerse Scopus, Embase y el Catálogo de Tesis y Disertaciones de la Coordinación para el Perfeccionamiento del Personal de Educación Superior (CAPES).

Resultados.

Se incluyeron 49 estudios, todos eran estudios transversales, incluyendo la muestra un total de 35069 participantes. La mayoría de los estudios incluidos se concentraban en el continente asiático (71.4%). Entre los estudios seleccionados, se encontró que la zona más afectada por el dolor era la región lumbar (81.57%), seguida de las regiones de cuello (71.5%) y hombros (31.57%).

Conclusión.

Según los estudios evaluados, la prevalencia de dolor ocupacional en los profesionales de enfermería fue de origen musculoesquelético. La elevada prevalencia de dolor encontrada refuerza la importancia de acompañar la salud de los trabajadores de enfermería.

Descriptores: dolor, enfermeras practicantes, enfermedades profesionales.

Resumo

Objetivo.

Mapear a literatura acerca da prevalência de dor em profissionais de enfermagem.

Métodos.

Trata-se de uma revisão de escopo que foi conduzida de acordo com metodologia do Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) para revisões de escopo, e de acordo com o Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). O O protocolo foi elaborado e registrado no Open Science Framework (OSF) [https://osf.io/2zu73/]. A pesquisa foi realizada nas bases de dados: PubMed/MEDLINE, Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (BVS), Web of Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), SciVerse Scopus, Embase e o Catálogo de Teses e Dissertações da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Resultados.

Foram incluídos 49 estudos, todos eram estudos transversais e a amostra total dos estudos incluídos foi de 35.069 participantes. Maior parte dos estudos incluídos se concentrou no continente asiático (71.4%). Dentre os estudos selecionados, demonstrou-se que a área mais afetada foi a região lombar (81.57%), seguidas pelas regiões do pescoço (71.5%) e ombro (31.57%).

Conclusão.

De acordo com os estudos avaliados, a prevalência de dor ocupacional nos profissionais de enfermagem foi de origem musculoesquelética. A alta prevalência de dor encontradas reforça a importância do acompanhamento da saúde dos trabalhadores de enfermagem.

Descritores: dor, profissionais de enfermagem, doenças profissionais

Introduction

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or similar to, that associated with actual or potential tissue damage.” 1 It is one of the most common symptoms leading to medical care and impacts individuals’ personal and financial lives.2,3 Pain can be classified according to its time of evolution (acute or chronic), its site of origin (peripheral, central, visceral, and somatic), and its pathophysiological mechanism (neuropathic, nociplastic, and nociceptive).3,4 When observed clinically, it is possible to identify that pain triggers a wide variety of motor adaptations, ranging from subtle motor compensations during the performance of tasks to the complete avoidance of painful movements and activities.2

Chronic pain (CP) is characterized by its persistence after three months of the typical recovery period from an injury, or by being associated with chronic pathological conditions, leading to continuous or recurrent pain.4,5 Furthermore, CP is classified as a disease by the International Classification of Diseases - 11, entitled primary chronic pain (that is not explained by another chronic condition), there are also secondary chronic pains, which are related to other pathologies or conditions (CP related to cancer, neuropathic CP, secondary visceral CP, secondary musculoskeletal CP, secondary post-surgical/post-traumatic CP or secondary headache/orofacial CP).5 CP is considered an important public health problem, with serious consequences for both the individual and society in personal, social and economic terms, and may also be associated with higher levels of physical and emotional stress. Furthermore, it has a higher prevalence in women between the ages of 45 and 65.4,5 CP interferes with the ability to work, since it is one of the main causes of disability. A study conducted with North American citizens estimated that the costs of people with chronic pain were around US$560 billion per year in medical costs and lost productivity.3 CP is the main cause of sick leave, absenteeism and low productivity in the workplace.4

Currently, there is a growing increase in the prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) in several countries, manifesting in different clinical forms and reaching epidemic proportions. In the United States, WMSDs are the main cause of pain, suffering and disability in the workplace.6 WMSDs affect workers in various occupations, and this set of disorders affects muscles, tendons and nerves. The most common risk factors are poor posture and forced repetitive tasks; The presence of these disorders usually presents with insidious pain that, if left untreated, can lead to temporary or permanent incapacity for work.7 Work-related pain is directly linked to the increased number of sick leaves and absenteeism, and is the leading cause of disability, socioeconomic problems and reduced quality of life in the adult population of developed countries. Workers in various occupations have their health affected by debilitating musculoskeletal pain and/or work-related injuries in the hospital environment; musculoskeletal diseases continue to be the leading cause of decline in the workforce.7,8

Nursing professionals, in particular, are at greater risk than other health professionals of experiencing work-related musculoskeletal injuries and disorders, including low back pain.7,8 In nursing professionals, ergonomic factors, such as patient handling and other activities related to manual patient repositioning, have been identified as major risk factors for the presence of pain and injuries for these professionals, especially in the lumbar spine region.9 Nursing staff constitute the largest group of workers in the hospital setting and are responsible for the majority of patients’ care.10 During their duties, nursing professionals have a high physical burden; the continuous and repetitive action of lifting and transferring patients, associated with physical limitations due to poor ergonomics of hospital equipment, results in greater physiological stress for these professionals.8,9

The presence of disabling pain in this population requires attention, since nursing professionals are indispensable for the provision of quality health care and are present at all levels of health care. According to the Federal Nursing Council (COFEN), it is estimated that this category is responsible for approximately 90% of the care processes carried out in the health area, as well as for 60 to 80% of all actions in Primary Health Care.11 Disabling pain can lead to an increase in sick leave and absenteeism among these professionals, causing a workforce deficit to provide health care to patients. A preliminary search was carried out in the following databases: PROSPERO, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Open Science Framework and no published or ongoing scoping and systematic reviews were found that address the prevalence of pain manifestations in nursing professionals. Based on this assumption, it was observed that there is a need for an overview of the prevalence of pain in nursing professionals. That said, this review aims to map the literature on the prevalence of pain in nursing professionals.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews,12 and according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)13 for preparing the review report. The protocol for this review was developed and registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) [https://osf.io/2zu73/]. The guiding question for this review was developed based on the mnemonic PCC, Population (nursing professionals), Concept (pain) and Context (work environment). Thus, this scoping review aims to answer the research question: What is the prevalence of pain in nursing professionals?

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were established based on the elements of the guiding question, according to the PCC mnemonic, as detailed below: (P) - Population: studies that assessed the prevalence of pain in nursing professionals, whether nursing technicians, nursing assistants or nurses; (C) - Concept: manifestations of pain presented by nursing professionals; and (C) - Context: work environment. In view of the above, studies were included regardless of the year of publication and in all languages, with a view to developing a complete review with relevant quality. The following were excluded: studies that did not fit the research theme, studies that assessed other health professionals, qualitative studies, review studies, reports, protocols, letters, comments and conference proceedings.

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate published and unpublished studies. As recommended by the JBI (REF), the search process was carried out in 3 phases in the development of a comprehensive research strategy.

First phase: conducting an initial limited search in a selected database, with the aim of finding articles related to the topic of interest. In this first stage, the PubMed database was chosen. In this initial search, the following descriptors and Boolean operators were used: pain AND nurses AND occupational diseases. Based on the initial result (n=700), the titles, abstracts and index terms used to describe and categorize them were read. When observing that the initial strategy presented high sensitivity and many of the studies did not meet the inclusion criteria, the necessary adjustments were made to perform a new search in the same database, using the descriptors: Nurse, Occupational Disease, Musculoskeletal Disease, Ache, Physical Suffering. The result of the new search was 272 articles. The titles and abstracts of the first 20 articles were read to determine whether they would be relevant to the guiding question of the review. After observing that the new strategy proved to be more appropriate, adaptations were made for the other databases. The final search strategies are detailed in Table 1, with the respective adaptations for each of them.

Table 1. Search strategies.

| Database | Search strategy | Result |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((((nurse) AND (occupational disease)) AND (Musculoskeletal Disease)) AND (ache)) AND (Physical Suffering) | 272 |

| BVS | (nurses) AND (pain) AND (occupational disease) AND (Physical Suffering) | 83 |

| Web of Science | ((ALL=(nurse)) AND ALL=(pain)) AND ALL=(occupational disease) | 264 |

| SciELO | (pain) AND (nurses) AND (occupational diseases) | 11 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY ( nurse ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( occupational AND disease ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( musculoskeletal AND disease ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( pain ) ) | 333 |

| Embase | ('nurse'/exp OR nurse) AND 'occupational disease' AND 'musculoskeletal disease' AND pain | 64 |

| CAPES Theses and Dissertations Catalogue | (nurse) AND (pain) OR (Physical Suffering) AND (occupational disease) | 15 |

Second phase: it involves conducting targeted researches in each of the selected databases and information sources, as previously defined in the protocol. The following databases were investigated: PubMed/MEDLINE, Virtual Health Library (VHL), Web of Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), SciVerse Scopus, Embase and the Catalog of Theses and Dissertations of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Third phase: scanning the reference lists of the selected studies for critical evaluation, in order to identify any additional relevant research.

Study selection

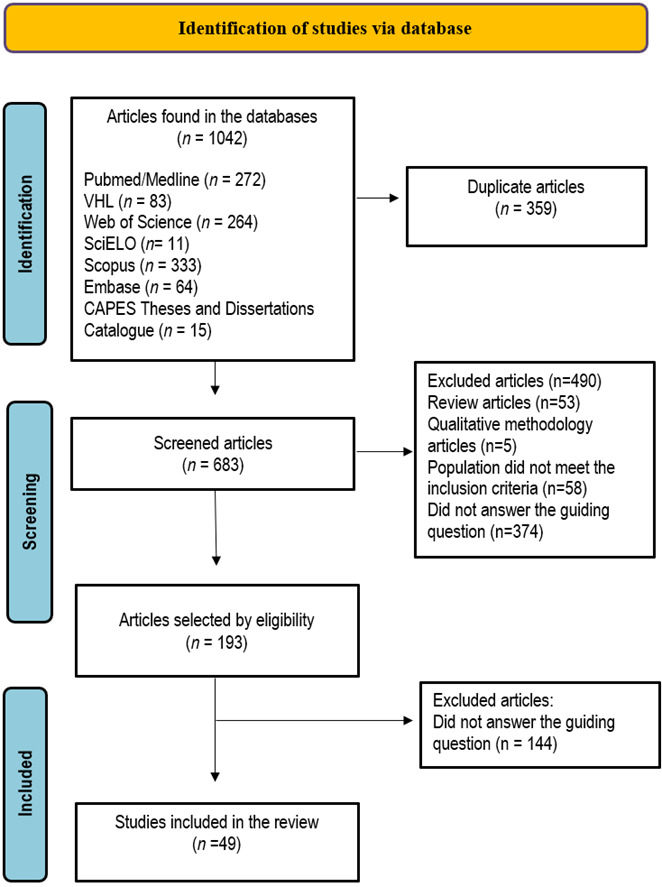

After the search, all identified citations were imported into the bibliography management software EndNote Web® and duplicate studies were removed. The remaining articles were imported into Rayyan Systems Inc. (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar).15,16 After a pilot test, two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria for the review. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full and their citation details were imported into Rayyan Systems Inc. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. The analysis of gray literature resulting from dissertations or theses occurred without the aid of automated tools. Two independent researchers performed the analysis of the titles and abstracts directly in the CAPES Dissertation and Theses Catalog. When necessary, the authors or coordinators of the graduate programs were contacted to request the full studies. Dissertations or theses that met the eligibility criteria were evaluated in full. The reasons for exclusion of articles, dissertations or theses after reading the full text were described in the PRISMA-ScR flowchart.13

Data extraction

Data were collected using the instrument suggested by the JBI.12 Subsequently, these data were standardized and organized in an electronic spreadsheet that included information on the title, authors, year of publication, type of study, number of participants, study location and prevalence of pain presented by nursing professionals.

Results

A total of 1042 studies were identified in the databases, of which 359 were duplicates, totaling 683. After analysis, 490 studies that did not meet the selection criteria were excluded. 193 studies were eligible, and after reading them in full, 144 studies were excluded. Thus, 49 studies were selected for this review. The results of the search and the study inclusion process are described in the PRISMA-SCR flowchart (Figure 1). The studies were published from 1996 to 2023. All were cross-sectional studies and the total sample of nursing professionals included was 35,069. Most of the included studies were concentrated in the Asian continent (71.4%) 18-26,29,33,35,36,38,39,42,44-49,51,52-58,60-64 followed by the European (14.2%) 30-32,34,37,40,50 American (8.1%) 28,41,43,65 and African (6.1%) 17,27,59 continents, with a predominance of publications in the last ten years (Table 2).

Figure 1. Flowchart of study selection according to PRISMA-SCR.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies by author, year of publication and results.

| Author, year of publication, country and sample | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akodu et al., 201917 Nigeria, n= 135 | Prevalence of WMSD in 12 months: | |||

| • Low back region: 43.2% • Knees: 9.9% • Shoulders: 9.9% | • Thoracic region: 9.9% • Neck: 8.6% • Elbows: 6.1% | • Ankles: 3.7% • Hips/thighs: 4.9% | • Wrist: 2.5% • Fingers: 1.2% | |

| Almaghrabi et al., 202118 Saudi Arabia, n=234 | 82.9% of nurses complained of low back pain. | |||

| • 0 day: 14.4% • 1 to 7 days: 50% | • 8-30 days: 8.2% | • >30 days: 19.6% | • Daily: 7.7% | |

| Almhdawi et al., 202019 Jordan, n= 597 | Prevalence of WMSD in the lower quadrant in 12 months: | |||

| • Low back region: 77.4% | • Knee: 37.5% | • Ankle/foot: 28.5% | • Hips/thighs: 22.3% | |

| Amin et al., 2014 20 Malaysia n= 376 | Prevalence of WMSD in 12 months by body region: | |||

| • Neck: 48.94% • Shoulder: 36.94% • Low back region: 35.28% | • Thoracic region: 40.69% • Arms: 6.63% • Wrists: 26.33% | • Thighs: 19.36% • Knees: 25.55% | • Feet: 47.2% • At least 1 region: 73.2% | |

| Ando et al., 200021 Japan, n= 314 | Prevalence of pain in the last month: | |||

| • Low back region: 57.7% | • Shoulder: 42.8% | • Neck: 31.3% | • Arm: 18.6% | |

| Attar et al., 201422 Saudi Arabia, n= 200 | The overall 12-month prevalence of self-reported WMSD was 85%. | |||

| • Low back region: 65.7% • Ankle/foot: 41.5% • Wrist/hand: 10% | • Shoulder: 29% • Knee: 21% | • Neck: 20% • Hips/thighs: 16.5% | •Mid back: 5% •Elbow: 3% | |

| Barzideh et al., 201423 Iran, n= 385 | Regions of musculoskeletal symptoms in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Low back region: 61.8% • Legs/feet: 59.7% | • Knees: 54.8% • Thoracic region: 54% | • Neck: 48.6% • Wrists/hands: 48.1% | • Shoulders: 45.5% • Thighs: 29.1% | |

| Chandralekha et al., 202224 India, n= 207 | The prevalence of WMSD among those in the last 12 months was 81.2% | |||

| • Low back region: 55.1% • Neck: 43.5% | • Shoulders: 43% | • More than one region: 38.2% | • More than 6 regions: 18.8% | |

| Cheung et al., 200525 China, n= 406 | The overall prevalence of back pain was 71.2%. | |||

| • Neck: 62.9% • Shoulders: 73.1% • Back: 71.2% | • Thoracic region: 61.2% • Low back region: 55.9% • Knees: 65.1% | • Ankles/feet: 53.4% • Wrists/hands: 30.3% | • Hips or thighs: 27.7% • Elbows: 17.3% | |

| Cheung et al.,201826 China, n= 440 | Prevalence of WMSD symptoms at the time of the survey: | |||

| • At least 1 region: 88.4% • Shoulders: 53% • Low back region: 41.4% | • Knees: 37.5 % • Ankles/feet: 28.2 % • Elbows/forearms 27.5% | • Wrists/hands: 25.8% • Fingers 25.7% • Neck: 24.8% | • Calf: 17.7% • Hips/thighs: 11.6% • Thoracic region: 6.4% | |

| Chiwaridzo et al., 201827 Zimbabwe, n= 117 | 82.1% reported WMSD in the last 12 months. | |||

| • Back (lower and upper): 84.3% | • Low back region: 67.9% | |||

| Daraiseh et al., 201028 USA, n= 263 | Musculoskeletal symptoms at 1 month were more prevalent in the following regions: | |||

| • Low back region: 74.1% | • Neck: 55.2% | • Ankle/foot: 52.5% | • Shoulders: 50% | |

| Dhas et al., 202329 , Qatar n= 127 | Presence of pain reported by region of the body: | |||

| • Low back region: 55.2% • Neck: 35.5% • Shoulder: 33.9% | • Thoracic region: 29.2% • Wrist/hand: 17.4% | • Ankle/foot: 15.8% • Knee: 15% | • Hips/thighs: 11.9% • Elbow: 7.9% | |

| Engels et al., 199630 The Netherlands, n= 846 | Complaints of pain by body region: | |||

| • Thoracic region: 7.9% • Low back region: 33.8% • Arm/Neck: 30.4% | • Neck: 22.9% • Shoulder: 19.5% • Elbow: 2.3% | • Wrist/hand: 5.7% • Leg: 15.7% • Hips/thighs: 6.9% | • Knee: 10.2% • Ankle/foot: 3.7% | |

| Eriksen et al., 200331 Norway, n= 6.485 | Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain during the last 14 days: | |||

| • Head: 41.9% • Neck: 53.5% • Shoulder: 47.1% | • Elbow: 11.7% • Wrist/hand: 20.8% • Thoracic region: 27.3% | • Low back region: 54.9% • Hips/thighs: 26.6% • Knee: 20.5% | • Ankle/foot: 15.5% • Any region: 88.8% • Generalized pain: 26.6% | |

| Freimann et al., 201632 Estonia, n= 409 | Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in the last year and in the last month: | |||

| • Low back region: 56.9% • Neck: 55.7% | • Shoulder: 30.9% • Elbow: 12.4% | • Wrist/hand: 20% • Knee: 31.2% | • Any region: 70% | |

| Gaowgzeh, 201933 Saudi Arabia, n= 60 | 61.7% of nurses had low back pain. | |||

| • Strong: 9.5% | • Moderate: 42.9% | • Mild: 47.6% | ||

| Gilchrist et al., 202134 Czech Republic, n=569 | • 84.7% of participants reported low back pain during the previous 12-month period • 76.6% of participants reported low back pain during the previous month | |||

| Karki et al., 202335 Nepal, n= 165 | Prevalence of MSD in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Neck: 60% • Shoulders: 45.5% • Elbows: 7.3% | • Wrists/hands: 43% • Thoracic region: 51.5% | • Low back region: 75.8% • Hips/thighs: 35.2% | • Knees: 38.8% • Ankles/feet: 37% | |

| Khan et al, 201936 Pakistan, n= 254 | - 185 nurses presented low back pain • 33.46% for more than 10 years • 23.23% for 6 to 10 years • 15.35% for 1 to 5 years. • 0.79% for less than 1 year. | - Among those who worked 6 to 7 hours: • 5.11% had mild pain • 12.6% had moderate pain • 10.63% had moderate pain | - Among those who worked 7 to 8 hours: • 9.06% had mild pain • 23.23% had moderate pain • 12.2% had moderate pain | |

| Knibbe et al., 199637 The Netherlands, n= 355 | Prevalence of back pain: | |||

| • Last 12 months: 66.8% | • Last 3 months: 51.8% | • Last 7 days: 20.6% | ||

| Koğa et al., 201938 Türkiye, n= 253 | • 62.8% of nurses reported a family history of low back pain. • Lifetime prevalence of severe low back pain: 28.2% • Lifetime prevalence of ongoing low back pain: 21.1% | |||

| Krishnan et al., 202139 Malaysia, n= 300 | Complaints of musculoskeletal pain or discomfort reported by nurses over a 12-month period: | |||

| • Low back: 86.7%; • Ankle/feet: 86.7%; • Neck: 86%; | • Shoulders: 85.3%; • MMI: 85%; • Cervical spine: 84.3%; | • Knees: 77.3%; • Femoral region: 73.7%; • Hip (66.3%); | • Wrist/hand: 63%; • Forearm: 61.7%; • Elbow: 55%; | |

| Latina et al., 202040 Italy, n= 280 | Reports of pain in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Low back region: 83.4% • Neck: 71.3% • Shoulders: 64.5% | • Back: 59.6% • Wrist: 43.9% | • Knees: 41.9% • Hips/thighs: 39.6% | • Ankles: 29.4% • Elbows: 24.2% | |

| Machado et al., 201441 Brazil, n= 309 | Low back pain was the most frequent health problem reported by professionals (52.8%). | |||

| Mehrdad et al., 201042 Iran, n= 317 | Musculoskeletal symptoms in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Low back region: 73.2% • Neck: 46.3% • Shoulders: 48.6% | • Elbows: 16.6% • Thoracic region: 43.5% | • Wrists/hands: 42.2% • Ankles/feet: 39.3% | • Hips/Thighs: 28.8% • Knees: 68.7% | |

| Moreira et al., 201443 Brazil, n= 258 | Musculoskeletal symptoms in the last 12 months: | |||

| • At least 1 region: 93.5% • Cervical spine: 47.8% • Thoracic spine: 50.8% • Lower back spine: 57.1% | • Spine: 76.3% • Shoulder: 52% • Elbow: 7.8% | • Hip/thigh: 32.7% • Wrist/hand: 31.8% • Upper limb: 62% | • Knee: 31.8% • Ankle/foot: 40.4% • Lower limb: 65.3% | |

| Nasaif et al., 202344 Bahrain, n= 550 | The prevalence of musculoskeletal complaints in the last 12 months was 88.1%. | |||

| • Low back region:72.3% | • Shoulders: 52.8% | • Neck: 49.0% | • Elbow: 12.1% | |

| Nguyen et al., 202045 Vietnam, n= 1.179 | Prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms during the last 12 months: | |||

| • Neck: M: 36.2% / W: 45.2% • Shoulder/arm: M: 22.2% / W: 30.6% • Elbow/forearm: M: 5.9% / W:30.6% | • Wrist/hand: M: 8.1% / W: 18.4% • Cervical spine: M: 24% / W: 33.4% • Lower back spine: M:28.5% / W: 47.9% | • Hip/thigh: M: 3.2% / W: 6.5% • Knee/leg: M: 14% / W: 21.4% • Ankle/foot: M: 16% / W: 8.8% | ||

| Nourollahi et al., 201846 Iran, n= 80 | Prevalence of WMSD in the body regions of hospital nurses: | |||

| • Low back region: 72% • Knees: 62% • Cervical spine: 57% | • Legs: 61% • Hands/wrist: 55% | • Neck: 46% • Shoulders: 42% | • Elbows: 30% • Hips: 21% | |

| Pinnar, 201047 Türkiye, n= 2.400 | Prevalence of WRMD in 12 months by body regions | |||

| • Low back region: 49.7% • Cervical region: 19.2% | • Neck: 35% • Shoulders: 38% | •Back/neck/shoulders: 13.7% •Legs: 30% | • Any region: 79.5% | |

| Samaei et al., 201748 Iran, n=243 | The prevalence of low back pain among 243 nursing professionals in Iran in the last 12 months was 69.5%. | |||

| Senthilkumar et al., 201949 India, n= 100 | Prevalence of pain in body parts: | |||

| ICU Nurses: • Neck: 57.6% • Shoulders: 44% • Back: 40.2% • Legs: 30.1% | General ward nurses: • Neck: 42.1% • Shoulders: 35.6% • Back: 30.6% • Legs: 25.4% | |||

| Serranheira et al., 201250 Portugal, n= 2.140 | - Prevalence of pain symptoms in the last 12 months: • Low back region: 60.6% • Neck: 48.6% • Thoracic region: 44.5% | - Prevalence of pain symptoms in the last 7 days: • Low back region: 29.5% • Neck: 25.8% • Thoracic region: 21.1% | ||

| Sezgin et al., 201551 Türkiye, n= 1.515 | The prevalence of MSD by body regions: | |||

| • Legs: 64.4% • Low back region: 58.8% • Back: 44.6% | • Shoulders: 33.7% • Neck: 30.3% | • Feet: 14.9% • Arms: 14.6% | • Fist: 9.6% • Head: 7.4% | |

| Sharma et al., 202252 India, n= 260 | The prevalence of WMSD in the last 12 months among Indian nurses was 80% | |||

| • Neck: 36% • Shoulders: 32% | • Elbow: 5% • Wrists/hands: 10% | • Back: 52% • Hip: 25% | • Knee: 28% • Ankles/Feet: 46% | |

| Frequency of pain: | • Regular: 50% | • Occasionally: 25% | • Never: 25/% | |

| Shieh et al., 201653 China, n= 788 | 72% of study participants reported having low back pain. | |||

| Smith et al., 200354 Japan, n= 305 | Prevalence of MSD: | |||

| • Low back region: 59% • Neck: 27.9% • Shoulders: 46.6% • Thoracic region: 10.2% | • Arms: 2.6% • Elbows: 2% • Forearms: 1.6% | • Wrists: 4.3% • Thighs: 11.8% • Knees: 16.4% | • Legs: 8.5% • Ankles: 7.5% • Any region: 78.4% | |

| Smith et al., 200455 China, n= 282 | Prevalence of musculoskeletal complaints in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Any region: 70% • Low back region: 56% | • Neck: 45% | • Shoulder: 40% | • Thoracic region: 37% | |

| Smith et al., 200456 China, n= 206 | MSD prevalence in the 12-month period: | |||

| • Low back region: 56.7% • Neck: 42.8% • Thoracic spine: 38.9% | • Shoulder: 38.9% • Elbows: 10% • Knees: 31.1% | • Wrists: 27.8% • Legs: 22.8% | • Ankle/feet: 34.4% • Any region: 70% | |

| Smith et al., 200557 Korea, n= 330 | Prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms: | |||

| • Neck: 62.7% • Shoulders: 74.5% • Thoracic region: 29.7% | • Elbow: 6.4% • Forearm: 9.7% • Wrists/hands: 46.7% | • Low back region: 72.4% • Thighs: 14.2% • Knees: 35.2% | • Legs: 52.1% • Feet: 38.8% • Any region: 93.6% | |

| Tang et al.,202258 China, n= 651 | Twelve-month prevalence of SCI: | |||

| • Low back region: 73.5% • Neck: 73.2% • Shoulders: 66.2% | • Thoracic region: 56.3% • Thighs/hips: 38.9% | • Elbows: 29.5% • Wrists/hands: 42.6% | • Knees: 42.3% • Ankles/feet: 42.5% | |

| Tinubu et al., 201059 Nigeria, n= 128 | Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders: | |||

| • Low back region: 44.1% • Neck: 28% • Knees: 22.4% | • Thoracic region: 16.8% • Wrists/hands: 16.2% | • Shoulders: 12.6% • Ankles/feet: 10.2% | • Elbows: 7.1% • Hips/thighs: 3.4% | |

| Tojo et al.,201860 Japan, n= 640 | The prevalence of foot and ankle pain in the last month was 23% (SNQ) and 51% (MFPDI). | |||

| • Hallux: 14% • Little toe: 14% • Plantar forefoot: 9% | • Medial arch: 9% • Midfoot: 16% | • Ankle: 10% • Heel: 6% | • Heel back: 7% • Overall: 23% | |

| Yan et al., 201761 China, n= 6674 | - Prevalence of WMSD in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Neck: 59.77% • Shoulder: 49.66% • Back: 39.5% | • Elbow: 14.49% • Low back: 62.71% • Wrists: 21.7% | • Hip: 20.41% • Knee: 33.35% • Ankle: 29.86% | • 1 body region: 77.43% • 2 body regions: 68% | |

| Yang et al., 201962 China, n= 679 | Prevalence of pain by body region in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Low back region: 80.1% • Neck: 78.6% • Shoulder: 70.4% | • Thoracic spine: 39.3% • Elbow: 15.8% • Wrist/hand: 38.9% | • Hip/thigh: 29.9% • Knee: 37.4% | • Ankle/foot: 31.5% • Overall WMSD: 97.1% | |

| Yao et al., 201963 China, n= 692 | Prevalence of WMSD in the last 12 months: | |||

| • Elbow: 17.3% • Hip: 23.8% • Knee: 34.5% | • Hands/wrists: 30.1% • Ankle/foot: 30.6% • Neck: 68.2% | • Back: 39.7% • Shoulder: 54.6% | • Waist: 67.6% • Any region: 84% | |

| Yilmaz et al., 202264 Türkiye, n= 169 | Pain regions: | |||

| • Low back region: 68% • Neck: 52.1% • Back: 68% | • Shoulder: 46% • Elbow: 10.7% | • Hands/wrists: 29.6% • Hips/thighs: 28.4% | • Knees: 37.3% • Foot/ankle: 41.4% | |

| Zhang et al., 202065 USA, n= 327 | Reports of pain in the following areas of the body: | |||

| • Low back region: 63% • Neck: 50.6% | • Shoulder: 42.4% • Knee: 35% | • Fist/forearm: 24.2% | • Ankle/foot: 39.3%. | |

Legend: MSD - Musculoskeletal disorders; WMSD - Work-related musculoskeletal disorders; RSI - Repetitive strain injury; SCI - Musculoskeletal injuries; ADL - Activities of daily living; SNQ - Standardized Nordic Questionnaire; MFPDI - Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index.

Discussion

This scoping review mapped the literature on the prevalence of pain in nursing professionals. Among the selected studies that evaluated multiple regions of the body (38 studies)17,19-26,28-32,35,39,40,42-47,49-52,54-59,61-65, the majority demonstrated that the most affected area was the low back region (81.57%), followed by the neck (71.5%) and shoulder (31.57%) regions. Eight studies evaluated only the prevalence of low back pain18,33,34,36,38,41,48,53, two of back pain 27,37 and one only pain in the foot and ankle region.60 The incidence of low back pain among hospital nursing professionals is considerably high, being the main reason for sick leave in this professional segment.76 High physical or mechanical demands strain and fatigue the muscles, which can trigger low back pain due to prolonged positions and repetitive movements.73 Low back pain is recognized as a significant occupational risk in most countries, causing long-term impacts on the health of nurses, compromising their work performance and job stability, and having an overall impact on the quality of care provided to patients.74 In addition, nurses who have had low back pain and continue to work are at greater risk of experiencing situations that aggravate their low back pain.75

In all included studies, the pain was of musculoskeletal origin. Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) represent a major health concern, being internationally recognized as the second leading cause of physical disability.66 MSDs represent a significant problem for nursing professionals, since they directly impact quality of life, increase absenteeism and restriction of work functions, in addition to the considerable financial cost for individuals and organizations.59 Some studies have concluded that the high prevalence of pain in various regions of the body was associated with psychosocial factors, especially stress, suggesting that the interactions of psychosocial factors and physical exhaustion potentially increased the risk of musculoskeletal pain in nursing professionals.(20,42,55) In addition, another study indicated that high psychological and physical demands at work were associated with an increase in back injuries.23

Musculoskeletal pain symptoms have also been associated with organizational factors, such as type of hospital, frequent schedule changes, type of shift work, patient handling, and working conditions,21,49,51 similarly, high physical workload is associated with increased low back pain in hospital nurses, along with longer working hours and many hours standing with constant commuting.18,22,25,26,53,59 High workloads and stress have been associated not only with pain but also with the risk of injuries. In the study by Clark67 et al., it was observed that high work demands were related to an increased likelihood of needlestick injuries and near misses among hospital nurses.67 Musculoskeletal pain in nurses is a result of work demands and physical exhaustion resulting from the professional activities performed, mainly affecting the low back, thoracic, and cervical regions.68-70

In the study by Tojo et al.60, where the prevalence of pain in the foot and ankle region was investigated, a pain prevalence rate in the last month of 23% was found using the standardized Nordic questionnaire and 51% using the Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index. Other studies included also provided data on prevalence in the foot and ankle region, where in four of them, the prevalence rate was greater than 50%23,25,28,39. Several conditions can generate chronic pain in the feet and ankle, however, the pain is mainly caused by inadequate footwear.71 Another important factor is work activities, since nurses spend most of their working time standing, they can develop several conditions resulting from the use of inadequate footwear, which can cause pain in the feet and ankles, such as plantar fasciitis, bunions and hammertoes. (72

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in nursing staff arise from direct activities with patients, such as bed baths, adjusting patients in bed, changing clothes, and transferring patients between beds and stretchers. This occurs when appropriate techniques are not used to deal with repetitive, monotonous, and physically demanding activities.77 Additionally, rotating shifts and night work contribute to pain, fatigue, and illness among these professionals.78

The conclusion of this study is that the prevalence of pain in nursing professionals was of musculoskeletal origin, with the most affected areas being the low back, neck, and shoulder regions. Working conditions, long working hours, and the intense workload faced by nursing professionals are associated with the presence of pain, especially in the low back region. The high prevalence of pain found reinforces the importance of monitoring the health of nursing workers, as well as the need for occupational changes, preventive actions and health education, since the presence of pain affects the well-being of the physical and occupational health of the nursing professional, which can compromise the quality of care and increase absenteeism at work.

References

- 1.Santana JM, Perissinotti DMN, Oliveira JO, Jr, Correia LMF, Oliveira CM, Fonseca PRB. Revised definition of pain after four decades. Brazilian Journal of Pain. 2020;3(3):197–198. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merkle SL, Sluka KA, Frey-Law LA. The interaction between pain and movement. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2020;33(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. 397Lancet. 2021;29(10289):2082–2097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figueiró JAB, Angelotti G, Pimenta CAM. Dor e Saúde Mental. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguiar DP, Souza CPQ, Barbosa WJM, Santos-Júnior FFU, Oliveira AS de. Prevalence of chronic pain in Brazil: systematic review. Brazilian Journal of Pain. 2021;4(3):257–267. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos KOB, Almeida MMC, Gazerdin DD da S. Dorsalgias e incapacidades funcionais relacionadas ao trabalho: registros do sistema de informação de agravos de notificação (SINAN/DATASUS) Revista brasileira de saúde ocupacional. 2016;41 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein S, Sparer EH, Tran BN, Ruan QZ, Dennerlein JT, Singhal D, Lee BT. Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Surgeons and Interventionalists: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surgery. 2018;153(2):e174947. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shieh SH, Sung FC, Su CH, Tsai Y, Hsieh VC. Increased low back pain risk in nurses with high workload for patient care: A questionnaire survey. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology. 2016;55(4):525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kołcz A, Jenaszek K. Assessment of pressure pain threshold at the cervical and lumbar spine region in the group of professionally active nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Occupational Health. 2020;62(1):e12108. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haegdorens F, Van Bogaert P, De Meester K, Monsieurs KG. The impact of nurse staffing levels and nurse's education on patient mortality in medical and surgical wards: an observational multicentre study. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):864–864. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conselho Federal de Enfermagem (COFEN) Enfermagem em defesa da saúde como direito constitucional. Brasília: COFEN; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annal of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joanna Briggs Institute . Template for scoping reviews protocols. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rayyan . How to do a Systematic Review - Rayyan Systematic Review Tutorial. Cambridge; RayyanSystemsInc: 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rayyan systems inc . About Rayyan. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akodu AK, Ashalejo ZO. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders and work ability among hospital nurses. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2019;14(3):252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almaghrabi A, Alsharif F. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Associated Risk Factors among Nurses at King Abdulaziz University Hospital. International Journal of Environmental Research ans Public Health. 2021;18(4):1567–1567. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almhdawi K A, Alrabbaie H, Kanaan SF, Oteir AO, Jaber AF, Ismael NT, Obaidat DS. Predictors and prevalence of lower quadrant work-related musculoskeletal disorders among hospital-based nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2020;33(6):885–896. doi: 10.3233/BMR-191815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin NA, Nordin R, Fatt QK, Noah RM, Oxley J. Relationship between Psychosocial Risk Factors and Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Public Hospital Nurses in Malaysia. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2014;26:23–23. doi: 10.1186/s40557-014-0023-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ando S, Ono Y, Shimaoka M, Hiruta S, Hattori Y, Hori F, Takeuchi Y. Associations of self estimated workloads with musculoskeletal symptoms among hospital nurses. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2000;57(3):211–216. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attar SM. Frequency and risk factors of musculoskeletal pain in nurses at a tertiary centre in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2014;7:61–61. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barzideh M, Choobineh AR, Tabatabaee HR. Job stress dimensions and their relationship to musculoskeletal disorders in Iranian nurses. Work : a journal of prevention, assessment, and rehabilitation. 2014;47(4):423–429. doi: 10.3233/WOR-121585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandralekha K, Joseph M, Joseph B. Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders and Quality of Life Among Staff Nurses in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Bangalore. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2022;26(3):178–182. doi: 10.4103/ijoem.ijoem_25_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung K, Gillen M, Faucett J, Krause N. The prevalence of and risk factors for back pain among home care nursing personnel in Hong Kong. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2006;49(1):14–22. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung K, Szeto G, Lai GKB, Ching SSY. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Work-Related Musculoskeletal Symptoms in Nursing Assistants Working in Nursing Homes. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health. 2018;15(2):265–265. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiwaridzo M, Makotore V, Dambi JM, Munambah N, Mhlanga M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among registered general nurses: a case of a large central hospital in Harare, Zimbabwe. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(1):315–315. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daraiseh NM, Cronin SN, Davis LS, Shell RL, Karwowski W. Low back symptoms among hospital nurses, associations to individual factors and pain in multiple body regions. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2010;40(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhas BN, Joseph L, Jose JA, Zeeser JM, Devaraj JP, Chockalingam M. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among pediatric long-term ventilatory care unit nurses: Descriptive cross-sectional study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2023;69:e114–e119. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2022.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engels JA, van der Gulden JW, Senden TF, van't Hof B. Work related risk factors for musculoskeletal complaints in the nursing profession: results of a questionnaire survey. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 1996;53(9):636–641. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.9.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksen W. The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in Norwegian nurses' aides. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2003;76(8):625–630. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freimann T, Pääsuke M, Merisalu E. Work-Related Psychosocial Factors and Mental Health Problems Associated with Musculoskeletal Pain in Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pain Research Management. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/9361016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaowgzeh RAM. Low back pain among nursing professionals in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Prevalence and risk factors. Journal of Back Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2019;32(4):555–560. doi: 10.3233/BMR-181218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilchrist A, Pokorná A. Prevalence of musculoskeletal low back pain among registered nurses: Results of an online survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021;30(11-12):1675–1683. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karkz P, Joshi YP, Khanal SP, Gautam S, Paudel S, Karki R, Acharya R. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Occupational Musculoskeletal Disorders among the Nurses of a Tertiary Care Center of Nepal. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Health. 2023;13(3):375–385. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan T, Tanveer F, Ahmad A, Gilani SA. Prevalence of occupational low back pain and its association with job duration and working hours among nurses working in hospitals of Lahore, Pakistan. Rawal Medical Journal. 2019;44(3):594–596. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knibbe JJ, Friele RD. Prevalence of back pain and characteristics of the physical workload of community nurses. Ergonomics. 1996;39(2):186–198. doi: 10.1080/00140139608964450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koğa AÖ, Deniz ÖP, Abacıgil F, Beşer E. The Prevelance of Low Back Pain and Risk Factors Among Nurses Working in a University Hospital: A Cross Sectional Study. Meandros and Medical Dental Journal. 2019;20:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnan KS, Raju G, Shawkataly O. Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: Psychological and Physical Risk Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(17) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latina R, Petruzzo A, Vignally P, Cattaruzza MS, Vetri Buratti C, Mitello L, Giannarelli D, D'Angelo D. The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and low back pain among Italian nurses: An observational study. Acta Biomedica. 2020;91(12-S):e2020003. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i12-S.10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado LS de F, Rodrigues EP, Oliveira L de MM, Laudano RCS, Nascimento CL., Sobrinho Agravos à saúde referidos pelos trabalhadores de enfermagem em um hospital público da Bahia. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 2014;67(5):684–691. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167.2014670503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehrdad R, Dennerlein JT, Haghighat M, Aminian O. Association between psychosocial factors and musculoskeletal symptoms among Iranian nurses. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010;53(10):1032–1039. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moreira RFC. Prevalência de sintomas musculoesqueléticos em ambiente hospitalar técnicos de enfermagem e auxiliares de enfermagem: associações com dados demográficos fatores. Revista Brasileira de Fisioterapia. 2014;18(4):323–333. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nasaif H, Alaradi M, Hammam R, Bucheeri M, Abdulla M, Abdulla H. Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms among nurses: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Bahrain. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2023;29(1):192–198. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2021.2025315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen TH, Hoang DL, Hoang TG, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Multisite Musculoskeletal Symptoms among District Hospital Nurses in Haiphong, Vietnam. BioMed Research International. 2020;2020:3254605–3254605. doi: 10.1155/2020/3254605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nourollahi M, Afshari D, Dianat I. Awkward trunk postures and their relationship with low back pain in hospital nurses. Work : a journal of prevention, assessment, and rehabilitation. 2018;59(3):17–323. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.PINAR R. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Turkish Hospital Nurses. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences. 2010;30(6):1869–1867. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samaei SE, Mostafaee M, Jafarpoor H, Hosseinabadi MB. Effects of patient-handling and individual factors on the prevalence of low back pain among nursing personnel. Work: a journal of prevention, assessment, and rehabilitation. 2017;56(4):551–561. doi: 10.3233/WOR-172526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senthilkumar S, Gokul S Kiran. Rapid Upper Limb Analysis in Musculoskeletal Disorders among Intensive Care Unit Nurses. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2019;12:8–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serranheira F, Cotrim T, Rodrigues V, Nunes C, Sousa-Uva A. Nurses' working tasks and MSDs back symptoms: results from a national survey. Work : a journal of prevention, assessment, and rehabilitation. 2012;41(Suppl 1):2449–2451. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0479-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sezgin D, Esin MN. Predisposing factors for musculoskeletal symptoms in intensive care unit nurses. International Nursing Review. 2015;62(1):92–101. doi: 10.1111/inr.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma F, Kalra S, Rai R, Chorsiya V, Dular S. Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders, Workability and its Predictors among Nurses Working in Delhi Hospitals: A Multicentric Survey. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2022;16(10):LC01–LC06. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shieh SH, Sung FC, Su CH, Tsai Y, Hsieh VC. Increased low back pain risk in nurses with high workload for patient care: A questionnaire survey. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;55(4):525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith DR, Choe MA, Jeon MY, Chae YR, An GJ, Jeong JS. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal symptoms among Korean hospital nurses. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2005;11(4):431–440. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2005.11076663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith DR, Ohmura K, Yamagata Z, Minai J. Musculoskeletal disorders among female nurses in a rural Japanese hospital. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2003;5(3):185–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith DR, Wei N, Kang L, Wang RS. Musculoskeletal disorders among professional nurses in mainland China. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2004;20(6):390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith DR, Wei N, Zhao L, Wang RS. Musculoskeletal complaints and psychosocial risk factors among Chinese hospital nurses. Occupational Medicine. 2004;54(8):579–582. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang L, Wang G, Zhang W, Zhou J. The prevalence of MSDs and the associated risk factors in nurses of China. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2022:87–87. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tinubu BM, Mbada CE, Oyeyemi AL, Fabunmi AA. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses in Ibadan, South-west Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2010;20(11):12–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tojo M, Yamaguchi S, Amano N, Ito A, Futono M, Sato Y, Naka T, Kimura S, Sadamasu A, Akagi R, Ohtori S. Prevalence and associated factors of foot and ankle pain among nurses at a university hospital in Japan: A cross-sectional study. 27Journal of Occupational Health. 2018;60(2):132–139. doi: 10.1539/joh.17-0174-OA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan P, Li F, Zhang L, Yang Y, Huang A, Wang Y, Yao H. Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Nurses Working in Hospitals of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Pain Research and Management. 2017;2017:5757108–5757108. doi: 10.1155/2017/5757108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang S, Lu J, Zeng J, Wang L, Li Y. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Intensive Care Unit Nurses in China. Workplace Health & Safety. 2019;67(6):275–287. doi: 10.1177/2165079918809107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yao Y, Zhao S, An Z, Wang S, Li H, Lu L, Yao S. The associations of work style and physical exercise with the risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in nurses. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2019;32(1):15–24. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yilmaz T, Isik Andsoy I. Musculoskeletal system disorders among surgical nurses related to the health industry in northwestern Turkey: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2022;28(4):2119–2124. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2021.1956797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, ElGhaziri M, Nasuti S, Duffy JF. The Comorbidity of Musculoskeletal Disorders and Depression: Associations with Working Conditions Among Hospital Nurses. Workplace Health & Safety. 2020;68(7):346–354. doi: 10.1177/2165079919897285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Azizpour Y, Delpisheh A, Montazeri Z, Sayehmiri K. Prevalence of low back pain in Iranian nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nursing. 2017;16:50–50. doi: 10.1186/s12912-017-0243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clarke SP, Rockett JL, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Organizational climate, staffing, and safety equipment as predictors of needlestick injuries and near-misses in hospital nurses. American Journal of Infection Control. 2002;30(4):207–216. doi: 10.1067/mic.2002.123392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schultz CC, Colect C de F, Treviso P, Stumm EMF. Factors related to musculoskeletal pain of nurses in the hospital setting: cross-sectional study. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem. 2022;43:e20210108. doi: 10.1590/1983-1447.2022.20210108.en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petersen R de S, Marziale MHP. Análise da capacidade no trabalho e estresse entre profissionais de enfermagem com distúrbios osteomusculares. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem. 2017;38(3):e67184. doi: 10.1590/1983-1447.2017.03.67184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Silva TPD da, Araújo WN, Stival MM, Toledo AM de, Burke TN, Carregaro RL. Desconforto musculoesquelético, capacidade de trabalho e fadiga em profissionais da enfermagem que atuam em ambiente hospitalar. Revista da escola de enfermagem da USP. 2018;52:e03332. doi: 10.1590/S1980-220X2017022903332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bálint GP, Korda J, Hangody L, Bálint PV. Regional musculoskeletal conditions: foot and ankle disorders. Best Practice & Research: Clinical Rheumatology. 2003;17(1):87–111. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(02)00103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Attar SM. Frequency and risk factors of musculoskeletal pain in nurses at a tertiary centre in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2014;7:61–61. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cargnin ZA, Schneider DG, Vargas MA de O, Machado RR. Dor lombar inespecífica e sua relação com o processo de trabalho de enfermagem. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2019;27 doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.2915.3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nelson A Owen B, Lloyd JD Fragala G, Matz M W, Amato M Lentz K. Safe Patient Handling and Movement. American Journal of Nursing. 2003;103(3):32–43. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200303000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Skela-Savič B, Pesjak K, Hvalič-Touzery S. Low back pain among nurses in Slovenian hospitals: cross-sectional study. International Nursing Review. 2017;64(4):544–551. doi: 10.1111/inr.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maul I, Läubli T, Klipstein A, Krueger H. Course of low back pain among nurses: a longitudinal study across eight years. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;60(7):497–503. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.7.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sousa BVN, Silva DLDS, Ferreira MS, Santana RR, Cunha WC, Brito C de O. Lesões por esforço repetitivo em profissionais de enfermagem: revisão sistemática. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Funcional. 2016;4(2):59–59. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Felli VEA. Condições de trabalho de enfermagem e adoecimento: motivos para a redução da jornada de trabalho para 30 horas. Enfermagem em Foco, São Paulo. 2017;3(4):178–181. [Google Scholar]