ABSTRACT

Objectives

The ultrasound diagnosis of placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT) is challenging owing to a lack of pathognomonic features. Differential diagnosis from other forms of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) is critical owing to major differences in prognosis and treatment. Doppler measurement of uterine artery (UtA) pulsatility index (PI) has been proposed for the diagnosis and management of GTN. The aim of this study was to evaluate the added value of UtA‐PI Doppler measurement during the standard transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) assessment, in patients with PSTT as compared to those with other GTN.

Methods

This was a single‐center prospective cohort study involving ultrasound assessment of all GTN cases referred to and treated at the trophoblast unit of San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy, between 2011 and 2023. TVS assessment included: grayscale analysis for the detection of myometrial or endometrial abnormalities, color and power Doppler assessment of lesions with scoring of vascularization, and spectral pulsed‐wave Doppler for measurement of mean UtA‐PI from the left and right UtAs. Sonographic findings were compared between patients with PSTT and those with other forms of GTN (postmolar, invasive mole or choriocarcinoma), using non‐parametric two‐tailed statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 73 GTN cases were recruited, comprising nine (12.3%) with PSTT and 64 (87.7%) with other GTN. A significant difference was detected between other‐GTN and PSTT cases when comparing rates of substantial endometrial vascularity on Doppler (50% vs 0%; P = 0.013) and mean UtA‐PI measurements (median, 1.5 (interquartile range (IQR), 1.0–2.4) vs 2.2 (IQR, 1.5–2.7); P = 0.014; area under the receiver‐operating‐characteristics curve, 0.768 (95% CI, 0.610–0.888)).

Conclusions

This study describes UtA‐PI as a novel and effective marker allowing for the ultrasound differentiation of PSTT from other forms of GTN. The significantly higher mean UtA‐PI and lower endometrial vascularity observed in PSTT as compared with other GTN suggests a unique vascularization pattern, with a potential role in differential diagnosis and management. © 2025 The Author(s). Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Keywords: choriocarcinoma, color‐power Doppler, gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, placental site trophoblastic tumor, uterine artery pulsatility index

INTRODUCTION

Gestational trophoblastic disease describes a group of rare premalignant and malignant pregnancy‐related disorders arising from the trophoblast 1 . The malignant forms are known as gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN), which includes invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT) and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor (ETT) 1 , 2 . PSTT is one of the rarest forms of GTN, representing 0.2–3% of all GTN cases and with an incidence of 1–5 per 100 000 pregnancies 3 . It is characterized by a slow growth pattern with initial spread within the uterus and local lymph node involvement 4 . The clinical presentation is non‐specific, with abnormal uterine bleeding being the most common symptom, and mildly elevated serum β‐human chorionic gonadotropin (β‐hCG) compared with other GTN forms 5 .

Given the rarity of the disease, paucity of available data and lack of pathognomonic patterns, diagnosis is challenging. However, a prompt differential diagnosis from other forms of GTN (such as invasive mole and choriocarcinoma) is crucial owing to its relative chemoresistance, which indicates demolitive surgery as the mainstay of treatment 6 . Transvaginal sonography (TVS) is the main imaging modality for the evaluation of GTN presenting with heterogeneous myometrial nodules, or solid masses invading the myometrium 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 . However, differentiation of PSTT from other GTN forms by TVS may be difficult 10 , 11 , 12 .

Recently, Doppler measurement of uterine artery (UtA) pulsatility index (PI) has been studied as a possible method contributing to the diagnosis and management of GTN 9 , 12 , representing a measure of tumor vascularity. UtA‐PI has been shown to correlate with the development of postmolar trophoblastic tumors 9 , 13 or chemotherapy resistance during GTN treatment 9 , 14 , 15 . In addition, patients with GTN show lower resistance on UtA Doppler indices than do those who are not pregnant, are in the first trimester of pregnancy or are diagnosed with miscarriage or hydatidiform mole 11 , 13 . However, there are no data regarding UtA Doppler indices in PSTT patients. Given the different biological origin and slower growth pattern of PSTT compared with other entities of the GTN spectrum, UtA Doppler parameters might be different.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the added value of UtA‐PI as part of the standard TVS assessment in patients with PSTT as compared to those with postmolar and non‐molar (invasive mole and choriocarcinoma) GTN.

METHODS

Study design, setting and participants

This single‐center prospective cohort study was approved by the ethics committee of San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy (protocol number 236/DG). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards for human research established by the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all included patients for the use of their personal data.

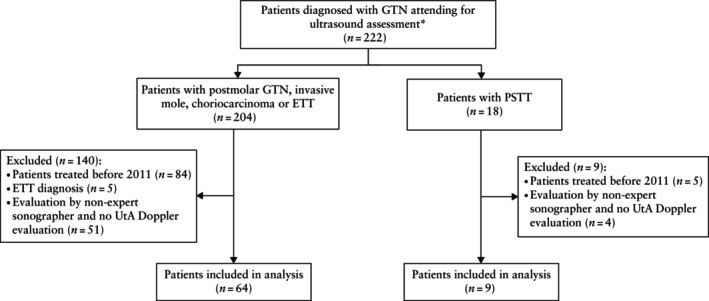

Data from all GTN patients evaluated in our center were comprehensively reviewed. GTN was defined in accordance with the criteria established by the European Organisation for Treatment of Trophoblastic Diseases as the set of malignant forms of gestational trophoblastic disease 16 . Clinically, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics criteria for the diagnosis of postmolar GTN include: β‐hCG plateau for four values over 3 consecutive weeks; β‐hCG levels rise more than 10% for three values over 2 weeks; and persistence of β‐hCG for more than 6 months after molar evacuation 1 , 2 . Only patients who were seen in our center between January 2011 and December 2023, for whom all study variables were available and who were assessed by one of two experienced operators (P.I.C. and R.C.) were selected. Patients with ETT were excluded from the GTN group due to the rarity of this condition and its distinct clinical behavior. The study was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies 17 . The recruitment process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

STROBE flowchart showing inclusion of patients in study. *Attending IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy. ETT, epithelioid trophoblastic tumor; GTN, gestational trophoblastic neoplasia; PSTT, placental site trophoblastic tumor; UtA, uterine artery.

Variables, data sources and measurements

Evaluated ultrasound features included: endometrial thickness, endometrial vascularization, theca lutein cysts, myometrial nodule, maximum nodule diameter, nodule echostructure (solid, liquid or mixed), nodule vascularization and UtA Doppler parameters such as UtA‐PI. Endometrial thickness was defined as pathological when it exceeded 14 mm. This cut‐off has been defined as such considering the maximum thickness in women of childbearing age in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle (12–14 mm according to the criteria of the International Endometrial Tumor Analysis group) 18 . Endometrial or myometrial color score was defined according to definitions of the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis group as a subjective semiquantitative assessment of the amount of blood flow present, with a color score of 1 indicating no flow, 2 minimal blood flow, 3 moderate flow and 4 intense flow 19 .

Ultrasound evaluations were performed by one of two experienced operators (P.I.C. and R.C.) and carried out using a 6–12‐MHz transvaginal probe (Voluson E8 or E10; GE Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) using dedicated machine presets for gynecology. The ultrasound beam frequency was set at an average level of 7 MHz and the pulse repetition frequency range was 1000–7000 Hz, Doppler gain was set at the lowest level to allow recording of adequate signals avoiding noise, and a wall filter of 30–100 Hz was used. Ultrasound grayscale analysis enabled the identification of myometrial lesions, appearing as abnormal areas of increased echogenicity within the myometrium or as abnormal endometrial thickening. A midsagittal longitudinal scan of the uterus was obtained for hysterometry and endometrial measurement; by rotating the probe 90°, a transverse view was obtained at the level of the maximum uterine width. In this phase, careful assessment of the myometrium was undertaken to detect uterine lesions or abnormalities, which were all investigated using color and power Doppler, with semiquantitative assessment and scoring of blood flow, applying standard machine presets. Spectral pulsed‐wave Doppler of the UtAs was performed transvaginally according to a standard procedure 20 , 21 , 22 : in a parasagittal section of the cervix, the UtAs were identified and pulsed‐wave Doppler was used to obtain flow‐velocity waveforms from the ascending branch of the UtA at the point closest to the uterocervical junction. When three similar consecutive waveforms had been obtained, the PI was measured by contour tracing of the waves. The PI was calculated as the difference between the peak systolic velocity (S) and the end‐diastolic velocity (D) divided by the time averaged velocity (Vm): PI = (S – D)/Vm. The mean UtA‐PI was calculated from the left and right UtAs and used for the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Since the distribution of continuous variables was not normal in all study groups according to the Shapiro–Wilk test, non‐parametric tests were used to compare study groups, with the Mann–Whitney U‐test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for dichotomous variables. Receiver‐operating‐characteristics (ROC)‐curve analysis was used to assess the performance of UtA‐PI measurement and the combination of UtA‐PI with the presence of endometrial vascularity in the diagnosis of PSTT. All calculated P‐values were two‐sided. Statistical analysis was carried out using the IBM SPSS software version 29 for Mac (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Ultrasound reports and UtA Doppler parameters at diagnosis were available for 73 patients diagnosed with GTN: nine (12.3%) affected by PSTT and 64 (87.7%) with a diagnosis of other forms of GTN (Figure 1). The clinical and ultrasound characteristics of the PSTT patients included in the analysis are reported in Table 1. The results of the analysis of the ultrasonographic characteristics of GTN and PSTT patients are reported in Table 2. The mean UtA‐PI was significantly higher in the PSTT group compared with the other‐GTN group (median UtA‐PI, 2.2 (interquartile range (IQR), 1.5–2.7) vs 1.5 (IQR, 1.0–2.4); P = 0.014). Additionally, the presence of vascularization in the endometrium was significantly less likely in patients with PSTT compared to those with the other forms of GTN (P = 0.013). Myometrial nodules were found in both groups, with a larger size observed in the group with other forms of GTN and a clearly solid echostructure noted more frequently in the PSTT group. No theca‐lutein cysts were observed in the PSTT group, which is in accordance with the significantly lower average β‐hCG level in this group compared to the group with other forms of GTN (53.4 vs 55404.7 IU/L; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical and ultrasound characteristics of nine patients diagnosed with placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT) included in analysis

| Case | Age (years) | Antecedent pregnancy | Interval from presentation to diagnosis (months) | β‐hCG (IU/L) | FIGO stage | Lesion location | Maximum lesion diameter (mm) | Lesion morphology | Lesion border | Vascularization on color Doppler | Doppler signal pattern | UtA‐PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42 | Term delivery | 24 | 13 | I | Myometrium (fundus), endometrial erosion | 40 | Heterogeneous | Well defined | Color score 4 | Intralesion |

L, 3.90; R, 3.10 |

| 2 | 38 | CHM | 13 | 92 | I | Myometrium, endometrial erosion | 20 | Solid | Ill defined | Color score 1 | Intralesion |

L, 2.43; R, 2.27 |

| 3 | 35 | TOP | 8 | 111 | I | Myometrium, endometrial and perimetrial erosion | 28 | Solid | Well defined | Color score 4 | Intralesion |

L, 3.12; R, 4.71 |

| 4 | 30 | TOP | 9 | 152 | I | Myometrium (right posterior wall) | 35 | Solid | Well defined | Color score 4 | Intraleson |

L, 1.00; R, 1.37 |

| 5 | 34 | Term delivery | 15 | 45 | I | Myometrium, endometrial erosion | 42 | Solid | Ill defined | Color score 3 | Intralesion |

L, 2.64; R, 1.92 |

| 6 | 38 | TOP | 3 | 2 | I | No lesion | — | — | — | — | — |

L, 2.95; R, 3.01 |

| 7 | 34 | Term delivery | 3 | 30.6 | I | Myometrium | 17 | Solid | Well defined | Color score 2 | Intralesion |

L, 2.20; R, 1.30 |

| 8 | 31 | TOP | 17 | 33 | III | Myometrium | 17 | Solid | Ill defined | Color score 3 | Intralesion |

L, 2.77; R, 3.55 |

| 9 | 33 | TOP | 15 | 2 | I | Myometrium | 15 | Solid | Ill defined | Color score 3 | Intralesion |

L, 2.33; R, 2.09 |

β‐hCG, β‐human chorionic gonadotropin; CHM, complete hydatidiform mole; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; L, left; R, right; TOP, termination of pregnancy; UtA‐PI, uterine artery pulsatility index.

Table 2.

Ultrasound characteristics of patients in study (n = 73), according to diagnosis of placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT) or other gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN)

| Ultrasonographic characteristics | Other GTN (n = 64 (87.7%)) | PSTT (n = 9 (12.3%)) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial thickness > 14 mm | 28 (43.8) | 3 (33.3) | 0.554 |

| Endometrial thickness (mm) | 15.0 (7.0–34.3) | 8.0 (6.0–25.0) | 0.824 |

| Presence of endometrial vascularization | 32 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0.013 |

| Presence of myometrial nodule | 47 (73.4) | 8 (88.9) | 0.314 |

| Maximum diameter of nodule (mm) | 34.0 (22.5–44.7) | 17.0 (16.0–38.5) | 0.136 |

| Solid myometrial nodule | 20/47 (42.6) | 7/8 (87.5) | 0.080 |

| Cystic or mixed myometrial nodule | 17/47 (36.2) | 1/8 (12.5) | 0.080 |

| Vascularized myometrial nodule | 33/47 (70.2) | 7/8 (87.5) | 0.729 |

| Theca‐lutein cysts | 16 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0.128 |

| Mean UtA‐PI | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 2.2 (1.5–2.7) | 0.014 |

Data are given as n (%), median (interquartile range) or n/N (%).

*Calculated from left and right uterine artery pulsatility index (UtA‐PI).

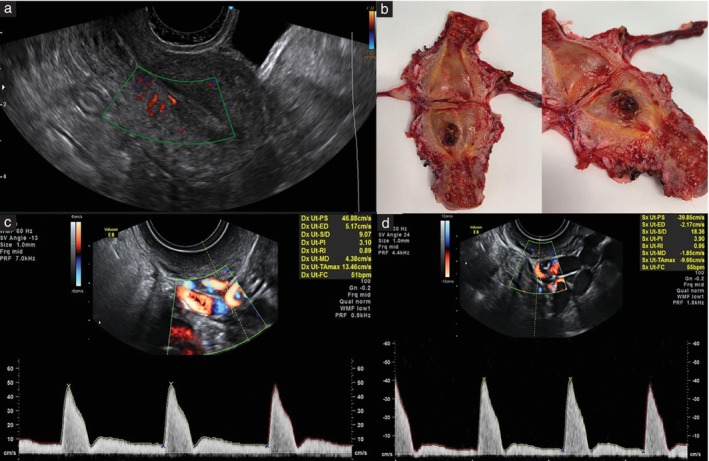

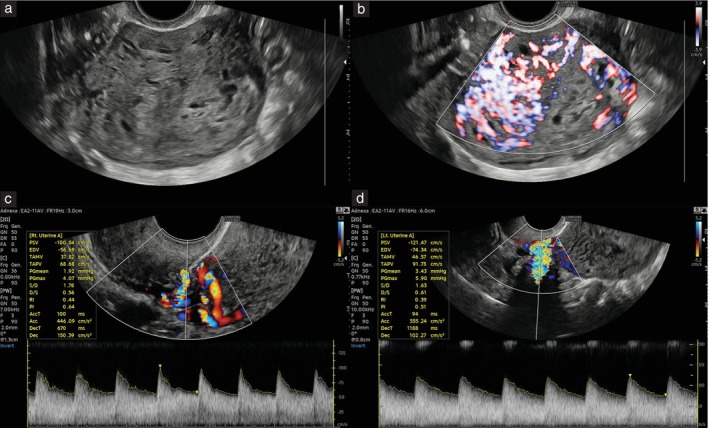

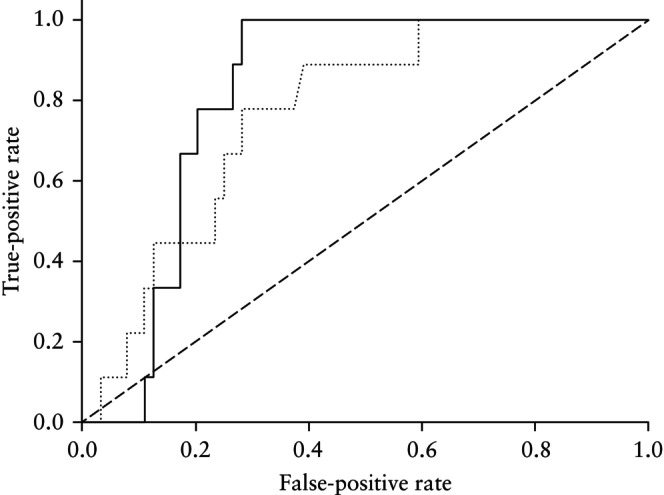

The ultrasound characteristics of PSTT and gestational choriocarcinoma are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. Figure 2b shows the corresponding macroscopic appearance of the PSTT nodule after hysterectomy, seen as a necrotic lesion infiltrating the inner half of the myometrium on the posterolateral wall of the uterus. The results of the ROC‐curve analysis for mean UtA‐PI for diagnosis of PSTT are reported in Figure 4. We found that a UtA‐PI higher than 1.7 predicted a diagnosis of PSTT with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 61% (Youden index, 0.498). The area under the ROC curve was 0.768 (95% CI, 0.610–0.888).

Figure 2.

Transvaginal ultrasound imaging of placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT) nodule of posterior uterine wall. (a) Longitudinal section of uterus with power Doppler interrogation of region of interest. (b) Macroscopic appearance of PSTT nodule in (a) after hysterectomy, seen as necrotic lesion infiltrating inner half of myometrium on posterolateral wall of uterus. (c,d) Spectral Doppler images and waveforms showing right (c) and left (d) uterine arteries.

Figure 3.

Transvaginal ultrasound imaging of gestational choriocarcinoma. (a) Grayscale image of uterus (transverse view). (b) Power Doppler interrogation of nodule in transverse view. (c,d) Spectral Doppler images and waveforms showing right (c) and left (d) uterine arteries.

Figure 4.

Receiver‐operating‐characteristics (ROC) curves for prediction of placental site trophoblastic tumor using mean uterine artery (UtA) pulsatility index (PI) ( ) and combination of presence of endometrial vascularity and mean UtA‐PI (

) and combination of presence of endometrial vascularity and mean UtA‐PI ( ). Area under ROC curve (AUC) for mean UtA‐PI, 0.768 (95% CI, 0.610–0.888). AUC for combined predictors, 0.819 (95% CI, 0.692–0.916).

). Area under ROC curve (AUC) for mean UtA‐PI, 0.768 (95% CI, 0.610–0.888). AUC for combined predictors, 0.819 (95% CI, 0.692–0.916).

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The findings presented in this paper represent a significant advancement in our understanding of the diagnosis of PSTT. For the first time, elevated mean UtA‐PI measurements observed in PSTT were compared with those in other forms of GTN, suggesting a clinically useful role for this parameter in the ultrasound diagnosis of this pathology. Incorporating UtA‐PI measurement into the ultrasound assessment of uterine structures significantly contributed to achieving an accurate diagnosis in the majority of cases. Specifically, our investigation revealed that in patients with suspected GTN, a UtA‐PI exceeding 1.7 predicted a diagnosis of PSTT with a sensitivity of 89%. These findings emphasize the potential clinical utility of UtA‐PI measurement in enhancing the diagnostic accuracy of PSTT, offering clinicians an additional tool for more precise and timely identification of this rare tumor subtype.

Comparison with the literature

The reliability of the different imaging techniques in the diagnosis of PSTT is a subject for debate. In the literature, data regarding the ultrasound diagnosis of PSTT are poor and conflicting (Table S1). Ultrasound examination may identify a heterogeneous mass, solid or cystic, within the endometrial cavity or with myometrial involvement 3 , 10 , 11 , 20 . PSTT may be characterized by differing vascularity, ranging from minimal to high with peripheral and central flow. Pulsed‐wave Doppler shows high‐velocity flow and low impedance 11 , 22 .

Zhou et al. 20 classified PSTT as three different sonographic patterns based on the location and characteristics of the lesion. Type 1 is characterized by a heterogeneous solid mass within the uterine cavity exhibiting minimal to moderate vascularization. Type 2 appears as a heterogeneous solid mass in the myometrium with minimal to high‐grade vascularization. Type 3 presents as a lacunar mass with cystic areas in the myometrium and high vascularization on color Doppler such as to represent an arteriovenous shunt. However, this classification is difficult to generalize, as it may have been limited by the small sample size examined (14 cases).

In particular, this study shows that none of the ultrasonographic features scrutinized in the analysis, including the presence of endometrial disease, presence of a myometrial lesion and lesion morphology, diameter and vascularization, exhibited statistically significant differences between PSTT and other types of GTN. The only parameters showing a statistically significant difference between the two groups were the UtA‐PI and the presence of endometrial vascularization. Doppler ultrasonography presents an effective means of studying tumor vascularization, offering reliability and non‐invasiveness.

Previous studies have established the utility of UtA‐PI measurement in furnishing valuable insights into the prediction of GTN risk during the post‐evacuation monitoring of hydatidiform moles. In a cohort of 246 patients followed up after evacuation of complete moles, UtA‐PI significantly increased in those with spontaneous remission, compared to pre‐evacuation measurements, whereas it remained significantly lower in those developing GTN13.

Another important application of UtA Doppler ultrasound is the evaluation of response to treatment in GTN patients. As shown by Agarwal et al. 15 in a cohort of 239 women, median UtA‐PI was significantly lower in chemoresistant compared to chemosensitive patients (P < 0.0001). Moreover, a gestational pattern with low resistance of the UtA vascularization has been reported in invasive mole and choriocarcinoma 13 , 14 , 23 . All patients affected by PSTT in our series presented with a high UtA‐PI on Doppler with a non‐gestational pattern of flow. This observation represents an important finding, since it may help to distinguish this rare entity from invasive mole and choriocarcinoma, before any invasive procedure is undertaken. Differentiating the two entities (which in most cases are almost indistinguishable clinically and sonographically) is extremely important; in fact, in case of PSTT, the patient should undergo nodule biopsy in order to obtain a histological diagnosis, and demolitive surgery for confirmation and treatment 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 . Such a diagnostic–therapeutic algorithm would be contraindicated in cases of GTN, particularly in choriocarcinoma. The reason PSTT does not alter UtA resistance is currently unknown. It is possible to hypothesize that PSTT (and possibly ETT) exhibits a different vascular morphological pattern than the other forms of GTN as a consequence of different tumor biology. This hypothesis also correlates with the lower β‐hCG levels and the lack of chemosensitivity of these tumors 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 .

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study exploring the role of UtA‐PI measurement in the diagnosis of PSTT. In fact, given the rarity of this condition, conducting prospective investigations on PSTT poses considerable challenges. Our institution serves as a national referral center for trophoblastic diseases, thereby potentially leading to a higher incidence of PSTT diagnoses in this study cohort compared with existing literature reports. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the primary limitation of this study lies in the relatively small sample size of patients included in the analysis. Consequently, further investigations involving larger cohorts are needed to validate and substantiate the diagnostic role of UtA‐PI measurement in identifying PSTT accurately.

Clinical and research implications

Our finding of increased UtA‐PI in PSTT compared with other variants of GTN provides an easy method of identifying PSTT after the diagnosis of GTN, allowing appropriate clinical management. Recently, our research team developed UtA‐PI reference ranges in pregnancy at 11–39 weeks' gestation with a robust statistical methodology based upon modulus exponential normal modeling and fractional polynomial regression 34 . It is essential that future investigations extend these reference ranges to encompass non‐pregnant patients, thus facilitating the clinical application of this concept. Moreover, the generalizability of this approach to various gynecological abnormalities emphasizes its potential broader utility within clinical practice.

Conclusions

This study represents a pioneering endeavor to evaluate UtA‐PI as a predictive marker in a case series of PSTT compared with other forms of GTN. Our findings demonstrate a significant elevation in mean UtA‐PI measurements in PSTT relative to other GTN variants, suggesting a distinct vascularization pattern unique to PSTT among trophoblastic tumors. Integration of UtA‐PI into the diagnostic algorithm may improve the accuracy of PSTT diagnosis, thereby addressing the pressing need for early differentiation between PSTT and other forms of GTN. Early diagnosis of these tumors using a non‐invasive technique such as TVS is crucial for the prompt initiation of appropriate management and improvement of the quality of life for these patients 35 .

Supporting information

Table S1 Clinical and ultrasonographic characteristics of patients diagnosed with placental site trophoblastic tumor, as reported in the literature

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open access funding provided by BIBLIOSAN.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chawla T, Bouchard‐Fortier G, Turashvili G, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: an update. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2023;48(5):1793‐1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mangili G, Sabetta G, Cioffi R, et al. Current evidence on immunotherapy for Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia (GTN). Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(11):2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zampacorta C, Pasciuto MP, Ferro B, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT): a case report and review of the literature. Pathologica. 2023;115(2):111‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moutte A, Doret M, Hajri T, et al. Placental site and epithelioid trophoblastic tumours: diagnostic pitfalls. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(3):568‐572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao J, Lv WG, Feng FZ, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: a review of 108 cases and their implications for prognosis and treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142(1):102‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark JJ, Slater S, Seckl MJ. Treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease in the 2020s. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;33(1):7‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garavaglia E, Gentile C, Cavoretto P, et al. Ultrasound imaging after evacuation as an adjunct to beta‐hCG monitoring in posthydatidiform molar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(4):417.e1‐417.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cavoretto P, Gentile C, Mangili G, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound predicts delayed response to chemotherapy and drug resistance in stage I low‐risk trophoblastic neoplasia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40(1):99‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cavoretto P, Cioffi R, Mangili G, et al. A pictorial ultrasound essay of gestational trophoblastic disease. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(3):597‐613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caspi B, Elchalal U, Dgani R, et al. Invasive mole and placental site trophoblastic tumor. Two entities of gestational trophoblastic disease with a common ultrasonographic appearance. J Ultrasound Med. 1991;10:517‐519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gadducci A, Carinelli S, Guerrieri ME, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor: clinical and pathological features, prognostic variables and treatment strategy. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(3):684‐693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin LH, Bernardes LS, Hase EA, et al. Is Doppler ultrasound useful for evaluating gestational trophoblastic disease? Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2015;70(12):810‐815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Asmar FTC, Braga‐Neto AR, de Rezende‐Filho J, et al. Uterine artery Doppler flow velocimetry parameters for predicting gestational trophoblastic neoplasia after complete hydatidiform mole, a prospective cohort study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2017;72(5):284‐288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sita‐Lumsden A, Medani H, Fisher R, et al. Uterine artery pulsatility index improves prediction of methotrexate resistance in women with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia with FIGO score 5‐6. BJOG. 2013;120(8):1012‐1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Agarwal R, Harding V, Short D, et al. Uterine artery pulsatility index: a predictor of methotrexate resistance in gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(6):1089‐1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lok C, van Trommel N, Massuger L, et al. Clinical Working Party of the EOTTD. Practical clinical guidelines of the EOTTD for treatment and referral of gestational trophoblastic disease. Eur J Cancer. 2020;130:228‐240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453‐1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leone FP, Timmerman D, Bourne T, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of the endometrium and intrauterine lesions: a consensus opinion from the International Endometrial Tumor Analysis (IETA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(1):103‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Timmerman D, Valentin L, Bourne TH, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of adnexal tumors: a consensus opinion from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(5):500‐505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou Y, Lu H, Yu C, et al. Sonographic characteristics of placental site trophoblastic tumor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(6):679‐684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feng X, Wei Z, Zhang S, et al. A review on the pathogenesis and clinical management of placental site trophoblastic tumors. Front Oncol. 2019;9:937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chaves MM, Maia T, Cunha TM, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumour: the rarest subtype of gestational trophoblastic disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(10):e235756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bettencourt E, Pinto E, Abraúl E, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumour: the value of transvaginal colour and pulsed Doppler sonography (TV‐CDS) in its diagnosis: case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1997;18(6):461‐464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang F, Zheng W, Liang Q, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of placental site trophoblastic tumor. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(7):1448‐1451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ichikawa Y, Nakauchi T, Sato T, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of uterine arteriovenous fistula associated with placental site trophoblastic tumor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(6):606‐608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nasiri S, Sheikh Hasani S, Mousavi A, et al. Placenta site trophoblastic tumor and choriocarcinoma from previous cesarean section scar: case reports. Iran J Med Sci. 2018;43(4):426‐431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leiserowitz GS, Webb MJ. Treatment of placental site trophoblastic tumor with hysterotomy and uterine reconstruction. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(4 Pt 2):696‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Savelli L, Pollastri P, Mabrouk M, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor diagnosed on transvaginal sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(2):235‐236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cho FN, Chen SN, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and management of a rare case with placental site trophoblastic tumor. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55(5):724‐727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Niknejadi M, Ahmadi F, Akhbari F. Imaging and clinical data of placental site trophoblastic tumor: a case report. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13(2):e18480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeng X, Liu X, Tian Q, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: a case report and literature review. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2015;4(3):147‐151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Nola R, Schönauer LM, Fiore MG, et al. Management of placental site trophoblastic tumor: Two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(48):e13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qin J, Ying W, Cheng X, et al. A well‐circumscribed border with peripheral Doppler signal in sonographic image distinguishes epithelioid trophoblastic tumor from other gestational trophoblastic neoplasms. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cavoretto PI, Salmeri N, Candiani M, et al. Reference ranges of uterine artery pulsatility index from first to third trimester based on serial Doppler measurements: longitudinal cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023;61(4):474‐480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Di Mattei V, Mazzetti M, Perego G, et al. Psychological aspects and fertility issues of GTD. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;74:53‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Clinical and ultrasonographic characteristics of patients diagnosed with placental site trophoblastic tumor, as reported in the literature

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.