ABSTRACT

Background: Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in refugees is higher compared to the general population, and barriers in accessing mental health care are often experienced. With staggering numbers of people seeking refuge around the world, and 40% being 18 years or younger, effective trauma-focused therapies for refugee children with PTSD are highly needed.

Objective: A systematic review and meta-analyses were conducted to provide an overview of, and to analyse, intervention studies using PTSD measures in young refugees, assessing treatment effectiveness and addressing efforts to mitigate barriers to mental health care.

Method: Eleven databases were searched for studies evaluating trauma-focused treatments (TFT) for refugee children (0–18). Meta-analyses were conducted for all included studies grouped together; and second, per intervention type, using posttreatment measures and follow-up measures. Pooled between-group effect sizes (ESs) and pre–post ESs, using a random-effects model were calculated.

Results: A total of 47 studies was retrieved, with 32 included in the meta-analyses. The narrative review highlighted positive outcomes in reducing posttraumatic stress symptoms for CBT-based interventions, EMDR therapy, KIDNET, and other treatments such as art therapy. Meta-analyses revealed medium pooled pre–post ESs for CBT-based interventions (ES = −.55) and large for EMDR therapy (ES = −1.63). RCT and CT studies using follow-up measures showed promising outcomes for KIDNET (ES = −.49). High heterogeneity of the included studies limited interpretation of several other combined effects. Results should be interpreted with caution due to the generally low quality of the included studies. All studies addressed efforts to minimize treatment barriers.

Conclusion: More high-quality studies are urgently needed to inform treatment recommendations. Evidence-based therapies, such as CBT-based interventions, EMDR therapy, and KIDNET, demonstrate promising findings but need further replication. Strategies to overcome barriers to treatment may be necessary to reach this population.

KEYWORDS: Trauma-focused treatment, refugees, displaced, children, cultural barriers, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychosocial interventions, kidnet, CBT, EMDR therapy

HIGHLIGHTS

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated intervention studies targeting PTSD in young refugees, analysing treatment effectiveness and barriers to mental health care.

Meta-analyses revealed medium to large pre–post effect sizes for CBT-based interventions and EMDR therapy. Medium between-group effect sizes where shown for KIDNET when using follow-up measures, suggesting effectiveness over time. All studies addressed efforts to minimize treatment barriers.

Due to high heterogeneity and generally low study quality, additional high-quality research is needed to inform treatment recommendations. Implementing strategies to overcome treatment barriers may be essential for effectively reaching this population.

Abstract

Antecedentes: La prevalencia del trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) en refugiados es más alta en comparación con la población general, y las barreras para acceder a la atención de salud mental son frecuentemente experimentadas. Con un número alarmante de personas que buscan refugio alrededor del mundo, y cuando 40% son menores de 18 años o menos, se necesitan urgentemente terapias eficaces centradas en el trauma para los niños refugiados con TEPT.

Objetivo: Una revisión sistemática y meta-análisis fueron llevados a cabo para proporcionar una mirada general de, y para analizar, los estudios de intervención usando las medidas de TEPT en refugiados jóvenes, evaluando la efectividad del tratamiento y abordando los esfuerzos por mitigar las barreras de atención de salud mental.

Método: Se buscaron estudios evaluando los tratamientos centrados en el trauma (TFT en su sigla en inglés) para niños refugiados (0–18) en once bases de datos. Los meta-análisis se llevaron a cabo para todos los estudios incluidos agrupados; y luego, por tipo de intervención, usando medidas al postratamiento y de seguimiento. Se calcularon los tamaños del efecto entre los grupos (ESs en su sigla en inglés) y ESs antes y después, usando un modelo de efectos aleatorios que fueron calculados.

Resultados: Un total de 47 estudios fueron extraídos, con 32 siendo incluidos en el meta-análisis. La revisión narrativa subrayó los resultados positivos en reducir los síntomas de estrés postraumático para las intervenciones basadas en TCC, terapia EMDR, KIDNET, y otros tratamientos como arte-terapia. Los meta-análisis revelaron ESs agrupados antes y después medianos para las intervenciones basadas en TCC (ES = −.55) y grandes para la terapia EMDR (ES = −1.63). Estudios de RCT y CT que utilizaron medidas de seguimiento mostraron resultados prometedores para KIDNET (ES = −.49). La alta heterogeneidad de los estudios incluidos limitó la interpretación de varios otros efectos combinados. Los resultados deberían ser interpretados con precaución debido a la baja calidad general de los estudios incluidos. Todos los estudios abordaron esfuerzos para minimizar las barreras al tratamiento.

Conclusión: Se necesitan urgentemente estudios de más alta calidad para recomendaciones de tratamiento definitivas. Las terapias basadas en la evidencia, tales como intervenciones basadas en TCC, terapia EMDR, y KIDNET, demostraron hallazgos prometedores, pero requieren mayor replicación. Es posible que se requieran estrategias para superar las barreras al tratamiento.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Tratamiento centrado en el trauma, refugiados, desplazados, niños, barreras culturales, trastorno de estrés postraumático, intervenciones psicosociales, KIDNET, EMDR, TCC

1. Introduction

At the end of 2023, 117.3 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced from their homes due to conflict, violence, or persecution (UNHCR, 2022). Approximately 40% of this population are children below 18 years (UNHCR, 2022). Refugee children commonly experience trauma and loss due to numerous challenging events before and during displacement. Besides, these minors might face other stressors when settling in a new host country, such as insecurity regarding long-lasting legal procedures, language barriers, adapting to new living circumstances, and discrimination (Fazel et al., 2012). Consequently, and despite resilience and flexibility, minors are at increased risk for developing a range of psychological problems such as posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, anxiety disorders, and behavioural difficulties (Henley & Robinson, 2011). In a recent systematic review, prevalence rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) between 19.0% and 52.7% were found in populations of refugee and asylum-seeking children (Kien et al., 2019). In addition, refugee children experience barriers in accessing mental health care. Examples of barriers to mental health services include mental health stigma, unstable living conditions, financial difficulties, language barriers, concerns about confidentiality, and lack of awareness regarding the available options and the procedures for accessing services (Byrow et al., 2020; Heidi et al., 2011; van Es et al., 2019). Untreated PTSD can lead to the onset of additional anxiety, mood, or substance use disorders, and may also negatively affect children's personality development, posing lifelong health risks (Kessler, 2000). The aforementioned studies emphasize the importance of effective and timely trauma treatment for refugee children and also underscore the necessity of adopting an appropriate culturally sensitive approach to effectively reach this target group.

Until now, several review articles have been published, focusing on the effectiveness of trauma-focused treatments for refugee children specifically (Chipalo, 2021; Cowling & Anderson, 2023; Genç, 2022; Nocon et al., 2017; Rafieifar & Macgowan, 2022). Nocon et al. (2017) published a systematic review and meta-analysis on psychosocial interventions, including 16 studies reporting PTSD outcomes. Among these, two studies evaluating cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) reported medium and large effects on PTSD compared to a control group. The effects of other studies using a control group were either non-existent or not statistically significant. Studies using pre–post analysis confirmed positive effects for CBT, as well as for other interventions, including Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy and writing for recovery. However, since mainly post-treatment data was used, the long-term effects remain unclear. Finally, due to high heterogeneity, the combined effect for PTSD outcomes could not be meaningfully interpreted. Another systematic review and meta-analysis focused on trauma-focused group interventions, demonstrating that CBT-based interventions, including school-based CBT, My Way – a group intervention for unaccompanied refugee minors (UCMs), and Teaching Recovery Techniques, effectively reduced PTSD symptoms, with a medium pooled effect size reported (Rafieifar & Macgowan, 2022). Unfortunately, follow-up effects were not assessed. Other systematic reviews summarized evidence supporting the effectiveness of trauma-focused CBT in reducing trauma symptoms and maintaining improvements during follow-up assessments (Chipalo, 2021), alongside therapies such as narrative exposure therapy (NET), EMDR therapy, My Way, and art therapy (Cowling & Anderson, 2023; Genç, 2022). However, these reviews lack meta-analyses (Chipalo, 2021; Cowling & Anderson, 2023; Genç, 2022), which are crucial for accurately estimating the effectiveness of specific treatments by evaluating the combined effects of the studies. Moreover, reviews generally overlook efforts to mitigate cultural barriers to accessing mental health services, despite the outlined obstacles. Addressing these efforts in reviews is important, as it not only enhances the understanding of treatment effectiveness by providing more context and insight into generalizability, but also helps to identify potential adjustments needed to improve accessibility, engagement, and feasibility. A recent study assessed psychological treatments for forced migrants in reducing PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. It included 32 studies focused on children and adolescents, revealing PTSD effect sizes ranging from −0.26 to −1.05 (Molendijk et al., 2024). This review evaluated whether the included studies incorporated language and/or cultural adaptations but provided no details on the specific adaptations made. The presence or absence of adaptations didn’t affect treatment outcomes. This review excluded studies involving internally displaced people (IDP), preventive interventions, or case studies. While the findings of the reviews suggest the effectiveness of psychological treatments for PTSD in refugee children, there is insufficient evidence to provide specific treatment recommendations for this population.

Given the continuous rise of the number of refugee children worldwide, it is crucial to build upon previous findings. Summarizing the above, previous reviews have become outdated, often overlooking the follow-up effects of treatment, lacking meta-analyses, or exclude certain target groups, such as IDP, or specific interventions. Efforts to decrease barriers to accessing mental health services are rarely described. Therefore, this review aims to enhance the current literature by systematically evaluating trauma-focused interventions for reducing PTSD complaints in refugee children and adolescents. To ensure the broadest possible inclusion of relevant studies, no exclusions were made based on intervention type or study design. The first objective is to create an up-to-date overview of the literature, including all described strategies to minimize potential (cultural) barriers. The second objective is to conduct a comprehensive meta-analysis, assessing the pre–post and follow-up effectiveness of potential trauma treatments in reducing PTSD symptoms in young refugees.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

The following databases were searched seven times between 27 August 2019 and 25 June 2024: PsycINFO (Ovid), Ovid Medline, Embase (Ovid), Ovid Evidence Based Medicine Reviews, PTSDpubs, Nederlandse Artikelendatabank voor de Zorg (NAZ), WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, Health Systems Evidence, NICE, and Open Grey. Search terms related to refugees, children, PTSD, and interventions were used in each search. The search strategy was developed in PsycINFO (Ovid) and translated to the other databases, while taking database specific thesaurus terms and technical aspects into account. The search strategy for PsycINFO (Ovid) is shown in Table S1 in the supplementary material. Furthermore, reference lists of previously published systematic reviews and tables of content of a few scientific journals were inspected to identify publications not retrieved from the original search. Searches were not limited by publication date or language.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the narrative review when: (1) More than half of the studied population are refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced people (IDP), or unaccompanied minor refugees (UCM); (2) the mean age of participants is under 19 years (3) including a trauma-focused intervention; (4) reporting PTSD symptoms measured with a clinical diagnostic interview or questionnaire. Conference abstracts and articles in a language other than Dutch or English were excluded.

2.3. Data extraction

A web-based programme for systematic reviews, Rayyan, was used to screen and select the references (Ouzzani et al., 2016). The titles and abstracts of all searches were screened by two researchers (MV and MS, TM, or BB), and disagreements were resolved by discussion. One author (MV) coded study characteristics. Two other authors (MS, TM) randomly checked a minimum of 20% of these characteristics to ensure accuracy. Coded study characteristics were: location of study, country of origin of participants, study population (refugee children, IDP, UCM), age, sample size (N), type of study (RCT, controlled trial, pre-posttest design), type of treatment, control group, number and duration of sessions, by whom the intervention was delivered: mental health professional (MHP) or trained lay person (TLP), instrument to measure PTSD, timing of follow-up measures if applicable, number and percentage of participants who discontinued intervention, approaches to minimize possible (cultural) barriers to treatment, and the main findings. The outcomes will be described in the narrative review of findings. Two authors (MV, RMK) extracted data on statistical measures, to be used in the meta-analysis.

2.4. Statistics

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA), version 3 (Biostat) was used to compute effect sizes, using random-effects models. First, a meta-analysis was performed with all eligible studies grouped together, which were categorized by study design for separate analyses. Pre–post studies were analysed using a specific template in the CMA programme, while controlled trials (CT) and randomized controlled trials (RCT) were analysed together with another template. Second, to account for anticipated high heterogeneity, we planned to perform meta-analyses for each treatment type separately, if at least two studies with the same design and treatment type (e.g. EMDR therapy, KIDNET, CBT-based interventions) were available. The primary outcomes were the post-treatment and, if available, follow-up measures of posttraumatic stress symptoms. If multiple questionnaires were used to assess PTSD, the data of the first questionnaire listed in Table 1 was selected for the meta-analysis. The selection was based on choosing the most frequently used questionnaire across studies to minimize heterogeneity. Additionally, self-report measures were prioritized over parent-report. Hedges’ g was used to indicate differences between treatment and control conditions using posttreatment measurements or follow-up measures, or to indicate differences between pre- and post-measurements in studies without a control group. An effect size of 0.2 was considered small, 0.5 was considered medium, and an effect size of 0.8 was considered large (Cohen, 1988).

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Publication | Study population, study location (age) | Type of study (N), Therapist training | Experimental group (intervention dose) | PTSD measure | Follow-up measures, number and percentage discontinued intervention | Approaches to minimize possible (cultural) barriers | Main findings regarding PTSD symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | |||||||

| Cognitive behavioural based interventions | |||||||

| Bosqui et al. (2023) | Syrian refugee children in Lebanon (8–14) | Multiple n = 1 design (N = 9) TLP | T-CETA (trauma and depression treatment flow – 8–12 sessions for child and 4–8 with caregiver) | CPSS | Pi (n = 0, 0.0%) | The original CETA manual underwent linguistic and cultural adaptation to be suitable for Syrian children and was adapted to be delivered via telephone. | All six children in the trauma treatment flow experienced a drop in trauma symptoms |

| Ehntholt et al. (2005) | Refugee children from Albanian, Sierra Leone, Turkey, Afghanistan, Somalia in the UK (11–15) | Controlled trial (N = 26) MHP | TRT – school-based CBT group (6 sessions of 60 min) | R-IES | Pi or after WL + 2 months (n = 0, 0.0%) | Intervention was offered in school setting. | CBT group: Significant decreases in PTSS. Follow-up: Gains not maintained at 2-month follow-up. Waiting list group: No improvements observed |

| WL (6 weeks) | |||||||

| Gormez et al. (2017) | Refugee children from Syria in Turkey (10–15) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 32) TLP | School-based group CBT (8 sessions of 70–90 min) | CPTS-RI | Pi (n = 0, 0.0%) | Intervention was offered in school setting. Arabic leaflets explaining the programme were available. Psychometric tools were validated in Arabic. Teachers guided assessment, and Arabic-speaking team members provided translations. Treatment was delivered by Arabic-speaking teachers. | Significant decreases in the PTSSI total score, intrusive and arousal symptoms were shown. |

| King and Said (2019) | UCM from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia in the UK (14–17) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 14) MHP | A psychological skills group (open group of 35 weeks, participants could join at any time) | CRIES-8 | Pi (n = 3, 21.4%, mean attendance of all participants was 65%) | Translators were available. Physical health, sleep and issues related to power/race or status were considered. Adaptions were made fitting the needs of the group as young people. | At the review time point, seven of the young people for whom data were available (N = 10) scored above the clinical threshold on the CRIES-8. |

| Lange-Nielsen et al. (2012) | Refugee children/ IDP in Gaza (12–17) | RCT (N = 124) MHP | Writing for recovery (3 days with 2 sessions of 15 min: 6 sessions of 15 min) | CRIES-13 | Pi, 19 days + 4/5 months (n = 14, 11.3%, all from the WL) | GTECL was administered with questions relevant to the Israeli siege. An Arabic version of the DSRS was obtained through translation and blind back-translation. | Results at posttest showed a reduction in PTSS in both groups. No evidence for improvements due to the intervention was found. |

| WL | |||||||

| Murray et al. (2018) | Refugee children from Somali at the Ethiopian/Somali border (7–18) | Pre-test/ post-test design (N = 38) TLP | CETA (6–12 sessions of 60–90 min) | CPSS-I | Pi (n = 1, 2,63%) | Utilized locally validated mental health instruments. The instruments were translated and back-translated into the Somali language. All items were discussed by a local team of interviewers to assess the meaning, conceptual clarity of the translations, and cultural appropriateness of each item for the local context. Locally relevant symptoms were included in measures. Treatment delivered by local counselors who were fluent in Somali. Delivered in refugee camps. | Results showed significant decreases in PTSS. Caregivers also reported significant decreases in child symptoms. |

| Rondung et al. (2022) | UCM’s from Afghanistan and Eritrea in Sweden (16–20) | Feasibility trial RCT, results show pre-test/posttest measures (N = 15) TLP | TRT – a group-based CBT programme (7 weekly sessions of two hours for youth, two caregiver sessions) | CRIES-13 | Pi + 18 weeks follow-up (14 participants received TRT, six attended four or more sessions) | Translators were available. Tried to facilitate attendance by arranging sessions at the residential care home where most youth lived. | Mean scores per measuring moment are shown. No statistical analyses are done. |

| WL | |||||||

| Ooi et al. (2016) | Refugee children from 15 countries in Africa and Asia in Australia (10–17) | RCT (N = 82) MHP | TRT – a group-based CBT programme (8 sessions of 60 min) | CRIES-13 | Pi + 3 month (n = 8, 9.8%) | Intervention was offered in school setting. Forms with information about the study were translated. Telephone translators were available. | Participants in the TRT condition showed a greater symptom reduction compared to WL condition, result was maintained at 3-month follow-up. |

| WL | |||||||

| Pfeiffer and Goldbeck (2017) | UCM from different countries, mainly from Afghanistan followed by Eritrea in Germany (14–18) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 36) TLP | My Way – a trauma-focused group intervention (6 sessions of 90 min) | CATS | Pi (n = 7, 19.4%) | A wide range of illustrations and nonverbal materials was used. The intervention was conceptualized as a limited number (six) of 90-minute sessions because of the often transient stay of UCMs in CAW programmes. Offered at CAW programmes. | Significantly fewer reported overall PTSS after intervention. There were 14 participants preintervention and 7 postintervention who fulfilled the PTSD criteria. |

| Pfeiffer et al. (2018) | UCM’s from Asian, middle-eastern and African countries in Germany (13–21) | RCT (N = 99) TLP | My Way – a trauma-focused group intervention (6 sessions of 90 min) Usual care |

CATS-S, CATS-C | 2 months Pi (n = 3, 3.0%) | Offered at CAW programmes. Self-report questionnaires were professionally translated into the most common native languages of the refugee population in Germany, using independent forward and backward translations. | My Way was significantly superior to usual care regarding self-reported PTSS, but not regarding caregiver-reported symptoms and self-reported dysfunctional posttraumatic cognitions. |

| Sarkadi et al. (2018) | UCM’s, majority from the middle east, largest group Afghans followed by Syrian in Sweden (13–18) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 90) TLP | TRT – a group-based CBT programme (5 sessions of 90–120 min) | CRIES-8 | Pi (n = 30, 33.3%) | Translators were available. Intervention was delivered at an asylum health care centre, a Red Cross Treatment Centre for Trauma, school health services and group homes for UCMs. | Although more than half (62%) of the participants reported negative life events during the study period, PTSS decreased significantly after the intervention. |

| Schottelkorb et al. (2012) | Refugee children from 15 different countries in the USA (6–13). | RCT (N = 31) TLP | CCPT (24 sessions of 30 min + 6 15 min parent consultations) TF-CBT (average of 17 sessions of 30 min + 2–4 sessions with parents) |

UCLA PTSD Index for DSM–IV + PROPS | Pi (n = 5, 16.1%) | Psychoeducation included refugee-specific trauma. Counselors received the book Four Feet, Two Sandals (focused on child refugees) along with art materials, books, and games for therapy. CCPT incorporated multicultural dolls, musical instruments, play food, and culturally relevant toys. The intervention was delivered in a school setting, with translators available. | Both CCPT and TF-CBT were effective in reducing trauma symptoms according to child and parent report. |

| Unterhitzenberger et al. (2015) | UCM from Somalia, Afghanistan, Iran in Germany (16–18) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 6) MHP | TF-CBT (12–28 sessions of 100 min) | CAPS-CA + PDS | Pi (n = 0, 0%) | Modifications to protocol for some participants: extend time for affective modulation, more than four sessions spent on the trauma narrative, creating a life-line before starting the narrative, use diverse methods for discussing trauma (audiotaping, walking around), focus on enhancing a feeling of safety. Collaboration with translators, with the option to consult for the impact of culture-related issues on emotions. | Moderate to high levels of PTSD were observed at baseline, with a clinically significant reduction in symptoms at posttest. |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner (2016) | UCM from East Africa in Germany (17) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 1) MHP | TF-CBT (12 sessions of 45–50 min) | CAPS-CA | Pi and 6 months follow-up (n = 0, 0.0%) | Simplified psychoeducation using illustrative graphics and additional trauma narrative sessions to enhance understanding. | The participant recovered from PTSD by the end of treatment, with stable success observed over 6 months. |

| Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al. (2019) | UCM Predominantly from Afghanistan in Germany (15–19) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 26) MHP | TF-CBT (a mean of 15 sessions of 100 min) | CATS | Pi, 6 weeks and 6 months follow-up (n = 4, 15.4%) | Translators were provided, allowing participants to choose their gender. Trusted caregivers were involved from the start. Multilingual information sheets were available, and additional psychoeducation covered PTSD and psychotherapy. A grief-specific component was added to TF-CBT for those with multiple losses, addressing homesickness and loss of homeland. | Post-intervention, the completers demonstrated significantly reduced PTSS. Improvements were sustained at 6 weeks and 6 months. |

| EMDR | |||||||

| Banoğlu and Korkmazlar (2022) | Syrian refugee children in Turkey (6–15) | RCT (N = 94) MHP | EMDR-GP/C (3–4 group sessions of 90–120 min) WL |

CPTS-RI | Pi (n = 33, 35.1%) | Bilingual Arabic and Turkish informative flyers were used. School meetings informed Syrian parents on the importance of early mental health care. A 24/7 hotline was set up for refugee families seeking research project information. Translators were available. | After the treatment, EMDR-GP/C had significantly lower trauma scores compared to WL. |

| Kuiper and Uriakhel (2020) | Refugee children from Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan in the Netherlands (7–18) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 12) MHP | EMDR (2–6 sessions) + access to a coach for practical support and to answer pedagogical questions | CRIES-13 | Pi + 3 month follow-up (n = 0, 0.0%) | Translators were available, via telephone or live. | EMDR significantly reduced trauma complaints, with effects stable after three months. |

| Lempertz et al. (2020) | Refugee children from Syria and Afghanistan in Germany (4–6) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 10) MHP | EMDR-based group treatment (5 sessions of 50–60 min) | DLTC + 15 questions from CBCL 1,5–5 | Pi, 3 month (n = 0, 0.0%, three children were absent for one session) | The story of ‘Ben the Bear,’ was chosen as bear being a cross-cultural figure with positive connotations. Treatment took place in the room where the children normally spent their days, thus minimizing the disruption for the families. Translators were available. The parents’ version of the CBCL was translated in a single one-way translation process into several languages. | According to preschool teachers’ perspective, PTSS dropped significantly at posttreatment and at follow-up. |

| Oras et al. (2004) | Refugee children from Asia, Turkey, Europe, Africa in Sweden (8–16) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 13) MHP | Age 8–13: EMDR + play therapy. Age 13+: EMDR + conversational therapy (5–25 sessions of which 1–6 sessions of EMDR) | PTSS-C | Pi (n = 0, 0.0%) | Translators were available. | A significant improvement was noticed in all PTSS-C scales after treatment. |

| Perilli et al. (2019) | Refugee children from Syria at the border between Turkey and Syria (8–17) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 14) MHP | EMDR-IGTP (3 sessions of 60–90 min) | CRIES-8 | 45 days pi (n = 5, 35.7%) | Cultural mediators, matched by gender, and Syrian translators were available. To reduce mental health stigma, psychoeducation on trauma, PTSD, and EMDR was provided. The study was introduced to key community members like imams. Sessions were held in the late afternoon to suit local customs. Refugees preferred to keep their treatment private. Drawings were used to express feelings without words. | A significant decrease in CRIES-8 scores after treatment was shown. |

| Wadaa et al. (2010) | Refugee children from Iraq in Malaysia (6–13) | Controlled trial (N = 37) MHP | EMDR (12 sessions) No treatment |

UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV parent version | Pi (n = 0, 0.0%) | Scale was translated and back-translated in Arabic and modified to suit the Arab culture. Professional Iraqi psychologists and psychiatrists were asked to judge this questionnaire for testing PTSD in the case of the children | EMDR, but not the control group, was effective in reducing PTSS. |

| KIDNET | |||||||

| Catani et al. (2009) | IDP in Sri Lanka (8–14) | RCT (N = 31) TLP | KIDNET (6 sessions of 60–90 min) MED-RELAX (6 sessions of 60–90 min) |

UCLA PTSD index for DSM-IV | 4/5 weeks +6 months (n = 0, 0.0%) | Treatment was delivered within the framework of an ongoing psychosocial school programme. Delivered in refugee camps. Delivered in own language. UCLA PTSD index was available in Tamil. | In both treatment conditions, PTSS were significantly reduced at one month post-test and remained stable over time, with no significant differences between the two groups. |

| Ertl et al. (2011) | IDP from Uganda in Northern Uganda (12–25) | RCT (N = 85) TLP | NET (8 sessions of 90–120 min) | CAPS for DSM-IV | 3 + 6 + 12 months (n = 4, 4.7%) | The VWAES was developed especially for use in the Northern Ugandan context. | PTSS severity was significantly more improved in the NET group than in the academic catch-up programme and WL. |

| WL | |||||||

| Academic catch-up programme (8 sessions of 90–120 min) | |||||||

| Onyut et al. (2005) | Refugee children from Somali in Uganda (13–17) | Pre-test/ post-test design (N = 6) MHP | KIDNET (4–6 sessions of 1–2 h) | CIDI, PDS for screening | Pi + 9 months (n = 0, 0.0%) | Offered in an African refugee settlement. Translators were available. | After nine months, four of the six participants no longer met the criteria for PTSD, two had borderline scores. |

| Peltonen and Kangaslampi (2019) | Refugee children from middle Eastern and African countries and one-quarter children with experiences of family violence in Finland (9–17) | RCT (N = 50) MHP | KIDNET (7–10 sessions of 90 min) | CRIES-13 | Midway, pi + 3 months follow up (n = 7, 14.0%) | Worked with translators. With one exception, the same interpreter worked with the same child in all sessions. | PTSS decreased regardless of treatment group. Within-group analyses showed that the decrease in PTSS was significant in the NET group only. |

| TAU | |||||||

| Ruf et al. (2010) | Refugee children from Turkey, Balkan, Syria, Chechnya, Russia, Georgia, Balkan in Germany (7–16) | RCT (N = 26) MHP | KIDNET (7–10 sessions of 90–120 min) WL (6 months) |

UCLA PTSD index for DSM-IV | Pi + 6 and 12 months (n = 1, 3.8%) | Parental involvement wasn’t required for this treatment. Children could attend with refugee support volunteers. Translators with prior training in PTSD and mental health were available to assist. | The KIDNET group, but not the controls, showed clinically significant improvements in PTSS and functioning, which were sustained at the 12-month follow-up. |

| Said and King (2020) | UCM’s from Sudan, Vietnam, Albania in the UK (16–17) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 4) MHP | NET (9–20 sessions) | CRIES-8 + CPSS-5 | Midtreatment + pi (n = 1, 25%) | Therapy was delivered in the participants preferred language, there was a possibility of working with translators. | The three completers showed reliable improvement, with two no longer meeting the PTSD clinical cut-off. The non-completer showed no change. |

| Schauer et al. (2004) | Refugee child from Somalia in Uganda (13) | Case study, pre–post measures (N = 1) MHP | KID-NET (4 sessions of 60–90 min) | PDS | Pi (n = 0, 0%) | Informed consent sheet was read in own language. Working with a translator. The therapy was delivered in the refugee camp. The Somali version of the PDS was available. | The post-test revealed that symptoms had remitted to a degree below the diagnostic threshold. |

| Other trauma-focused treatments | |||||||

| Cardeli et al. (2020) | Bhutanese refugee students in the USA (11–15) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 34) TLP | Tier 2 of Trauma-Systems Therapy for Refugees (TST-R) (skills-based groups) | UCLA PTSD-RI | Pi (n = 0, 0%) | The intervention was integrated into school services to normalize mental health support and improve attendance. Clinicians and cultural brokers collaborated. Cultural consultants guided item selection from a trauma screening scale (WTSS). Cultural brokers worked with community members to facilitate meetings with families to describe the group intervention, invite children to participate, and obtain parental consent. Groups met after school, with transportation home. The manual was adapted for Bhutanese refugees with input from a cultural broker, adding cultural notes for each session to provide context on relevant norms, believes and practices. | There was no significant difference between PTSS scores from baseline to postintervention. |

| Ellis et al. (2013) | Refugee children from Somali + Somali Bantu in the USA (11–15) | Controlled trial (N = 30) TLP | TST (tier 3 + 4) Child resilience building (tier 2, weekly sessions for 9 months) |

UCLA PTSD-RI | 6 + 12 months after baseline (n = 7, 23.3%) | The original TST model was further adapted for use with refugees by linking it to more broad-based community and group services (Tiers 1 and 2). Cultural brokers were integrated into treatment planning and implementation and were available to clarify any questions of the youths about the process or translation or meaning of an item. Questionnaires (WTSS and PWA) adapted for, and used with, Somali adolescents were chosen. | All tiers showed improvements in mental health and resources. Resource hardships were associated with PTSS over time, the stabilization of resource hardships coincided with significant improvements in PTSS for the top tier participants. |

| Eruyar and Vostanis (2020) | Refugee children from Syria in Turkey (8–14) | RCT (N = 30 parent-child dyads) MHP | Group theraplay (8 sessions of 45 min) No intervention |

CRIES-8 | Pi (n = 1 child and n = 13 parents) | Sessions were held on Saturdays near the children's school and homes. Measures were translated into Arabic. Children were divided into groups according to their gender, to assure cultural and religious sensitivity. Translator was available. | There was a significant improvement in children's PTSS. |

| Feen-Calligan et al. (2020) | Refugee children from Syria in the USA (7–14) | Controlled trial (N = 24) MHP | Art therapy (12 sessions of 90 min) No intervention |

UCLA PTSD-RI | Pi (83% retention rate) | Participants were provided with transportation to and from the intervention site, to bolster retention. Data was obtained by native Arabic speakers. Questionnaires were available in Arabic in written and oral form. | The findings showed a large significant effect of art therapy on posttraumatic stress compared to control group. |

| Garoff et al. (2019) | UCM mainly from Afghanistan and Iraq in Finland (9–17) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 18) MHP and TLP | Group-based mental health intervention (10 sessions of 90 min) | CRIES-13 | Pi (n = 2, 11.1%) | The intervention was delivered at the living location and (co-) facilitated by the staff that interact with the UCMs on a daily basis. Self-report questionnaires were translated using translation and back-translation. Translators were available. | No statistically significant changes on the PTSS measures were found. |

| Gotseva-Balgaranova et al. (2020) | Refugee families from Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria in Bulgaria and Germany (6–11) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 31, 15 children and 16 parents) EBTS leaders | Evidence-Based Trauma Stabilization programme (4 sessions with parents and 5 sessions with parent–child pairs) | TSCYC, cPC | Pi (n = 0, 0%) | The instruments were translated into Arabic and Farsi. Translators were available. The EBTS-Programme uses the language of the children – play and child-friendly, playful stabilization techniques. | There was a significant decrease in intrusion, arousal, depression, and dissociation in children. All scales showed a decrease in mothers’ results, but none were significant. |

| Grasser et al. (2019) | Refugee children from Syria in the USA (mean age 10) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 20) Unknown | Dance movement therapy (12 sessions of 90 min) | UCLA PTSD-RI | Pi (n = 5, 25%) | Programme adherence improved by providing free transportation for participants and simultaneous yoga sessions for mothers, with all sessions in native Arabic facilitated by a translator. | Following the 12-week DMT programme, changes in self-reported posttraumatic stress were observed. |

| Gupta and Zimmer (2008) | IDP in Sierra Leone (8–17) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 315) TLP | Rapid-Ed (8 sessions of 60 min trauma healing module + 16 sessions of 20 min of recreational activities) | IES | Pi (n = 9, 2.9%) | Interviews were done in Creole by locally trained female research assistants at their camps. The Sierra Leonean translation team ensured cultural and linguistic accuracy for items. The English-Creole questionnaires were verified through back-translation. Rapid-Ed literacy and numeracy modules were reviewed by an educational research specialist, in consultation with the Ministry of Education and Plan International staff, to ensure cultural relevance. | Post-test findings showed statistically significant decreases in intrusion and arousal symptoms. |

| Jordans et al. (2023) | Syrian refugees in Lebanon (10–14) | RCT (N = 198) TLP | EASE (7 group sessions for adolescents and 3 for caregivers of 90–120 min) | CRIES-13 | Pi + 3-months + 12-months (n = 23, 11.6%) | EASE was adapted to the cultural context. All instruments were translated into simple Arabic understandable to children living in Lebanon. | There were no significant differences in mean change between groups for PTSD outcomes. |

| Enhanced treatment as usual (one session of 30–45 min) | |||||||

| Koch et al. (2020) | Male Afghan refugees in Germany (15–21) | RCT (N = 44) MHP | STARC (14 sessions of 90 min) WL (4 months) |

HTQ, PCL-5 | Pi + 3 months (n = 8, 18.2%) | Translator was available. Self-report measures were translated into Dari and back-translated. Religious sayings were used with management of anger and provocations. | Significant improvement in PTSS were shown compared to the waitlist group, with effects sustained over 3 months. |

| Kubitary and Alsaleh (2018) | War- affected children and IDP in Syria (13–17) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 41) MHP | TRPPT (One time education in TRPPT for 90 min + at least three times a day for 3–5 min for 33 days) | DTS | Pi (n = 3, 7.3%) | Treatment was offered at school. Questionnaires were available in Arabic. | The results showed a significant decrease in PTSD. |

| Meyer DeMott et al. (2017) | UCM from Afghanistan, Somalia, Iran, Western Sahara, Palestine, Algeria in Norway (15–18) | Controlled trial (N = 145) MHP | EXIT (10 sessions of 1,5 h) LAU |

HTQ | Pi + 5 months + 15 months + 25 months (n = 2, 1.4%) | The instruments were presented in the participants’ native languages. Study was carried out at the arrival centre. Translator for each language participated. | There were significant time by group interactions in favour of the EXIT group for PTSS. |

| Mohlen et al. (2005) | Refugee children from Kosovo in Germany (10–16) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 10) TLP | Psychosocial treatment programme (2 diagnostic –,6 group –, 2–4 individual – and 1 family session) | HTQ | Pi (n = 0, 0%) | The current life situation (e.g. residing in a refugee accommodation) was considered. Treatment was offered in the refugee accommodation area. A translator was present during all sessions and interviews. Questionnaires were translated into Albanian. | Post-traumatic symptoms were reduced significantly. The rate of PTSD diagnoses fell from 60% to 30%. |

| Panter-Brick et al. (2018) | Refugee children from Syria and Jordanian youth in Jordan (12–18) | Experimental trial (n = 214) + RCT (n = 603) TLP | Advancing adolescents delivered in group format (16 sessions) | CRIES-8 | Pi + 11 months (n = 284 lost to follow-up, 34.8%) | Transport for participants by bus was provided. The same personnel undertook all surveys with adolescents, in Arabic. | No programme impacts for posttraumatic stress reactions was found. |

| WL | |||||||

| Thabet et al. (2005) | Refugee children in the Gaza strip (9–15) | Controlled trial (N = 111) 1 (MHP) 2 (teachers) | Crisis intervention group (7 sessions) Teacher education about symptoms (4 sessions) No intervention |

CPTSD-RI | 3 months after baseline (n = 0, 0%) | The interventions were provided in school. The protocol was adjusted to the nature of trauma (ongoing political conflict), sociocultural circumstances and children’s developmental ability. Arabic version of the CDI was available. | No significant impact of the group intervention was found on children’s PTSS. |

| Thierrée et al. (2020) | IDP in Syria (7–14) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 161) MHP | Trauma reactivation under propranolol (5 sessions of 10–20 min) | CPSS-5 | 1 month + 3 months follow-up (n = 30, 18.6%) | Questionnaires were available in Arabic, translated by a professional translator from Syria. | Significant symptom reduction was observed at all posttreatment measurement times vs. baseline. |

| Ugurlu et al. (2016) | Refugee children from Syria in Turkey (7–12) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 63) MHP | Art therapy | UCLA PTSD | Pi (n = 0, 0.0%) | Questionnaires were available in Arabic. Data collection was carried out by trained Syrian college students by going to refugees’ houses with the help of Sultan Beyli Municipality members. Assessment, procedure and sessions were in Arabic, with the help of translators. | Trauma symptoms of children were significantly reduced at the post-assessment. |

| van Es et al. (2021) | UCM from Eritrea, Syria and Afghanistan in the Netherlands (12–19) | Pre-test/post-test design (N = 41) MHP | Multimodal trauma-focused treatment (4–17 sessions of app 80 min) | CRIES-13 | Pi (n = 3, 7.3%) | Therapist collaborated with intercultural mediators. Outreach care in a familiar environment, to save the youngsters the effort of travelling, and to prevent feeling different from others because they have to go to a mental health institution. | A statistically significant reduction in PTSD scores was found. |

| van Es et al. (2023) | UCM from Eritrea and Syria in the Netherlands (15–18) | Mixed methods multiple baseline design (N = 10) MHP | Multimodal trauma-focused treatment (4–11 sessions of app 80 min) | CRIES-13 | Pi + 4 weeks follow-up (n = 3, 30.0%) | Therapist collaborates with intercultural mediators. Outreach care in a familiar environment, to save the youngsters the effort of travelling, and to prevent feeling different from others because they have to go to a mental health institution. | Quantitative results did not show clinically reliable symptom reductions at posttest or follow-up. |

Abbreviations: TLP: Trained lay persons. t-CETA: Telephone-delivered Common Elements Treatment. CPSS: Child PTSD Symptom Scale. Pi: Post intervention. MHP: Mental health professionals. TRT: Teaching Recovery Techniques. WL: waitlist. R-IES: Revised Impact of Event Scale. CPTS-RI: The child post-traumatic stress- reaction index. PTSS: post-traumatic stress symptoms. UCM: Unaccompanied refugee minors. CRIES: Children's Impact of Event Scale. GTECL: Gaza traumatic event check. IDP: internally displaced persons. RCT: randomized controlled trial. CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist. YSR: Youth Self Report. CATS: Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen. CATS-S: Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen self-report. CATS-C. Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen caregiver version. CCPT: Child centered play therapy. PROPS: Parent Report of Posttraumatic Symptoms. TF-CBT: Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral therapy. CAPS-CA: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents. EMDR: Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. SLE: Serious Life Events checklist. DLTC: Daily Life Test for Children. PTSS-C: Posttraumatic Stress Symptom Scale for Children. KIDNET: Narrative Exposure Therapy for children. MED-RELAX: meditation-relaxation. VWAES: The violence, War and Abduction Exposure scale. CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview. PDS: Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale. HSCL: Hopkins Symptom Checklist. TAU: Treatment as usual. TST: Trauma System Therapy. WTSS: War Trauma Screening Scale. TSCYC: Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Young Children. PCL-5: Self-assessment checklist for PTSD symptoms. cPC: Children Stress Checklist. EASE: Early Adolescent Skills for Emotions. HTQ: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire. STARC: Skills-Training of Affect Regulation- a Culture sensitive Approach. DTS: Davidson Trauma Scale. TRPPT: Therapy by Repeating Phrases of Positive Thoughts. EXIT: expressive arts intervention. LAU: Life as usual. CPTSD-RI: Child Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index.

Heterogeneity of study results was assessed by the I-squared statistic (I2), and a visual inspection of the forest plot and the prediction interval (IntHout et al., 2016). I2 shows the proportion of the variance in observed effects which is attributed to the variance in true effects. The prediction interval indicates how much the effect size varies using the same scale as the effect size itself. Additionally, publication bias was assessed by a visual inspection of the funnel plot and by conducting the Egger’s test of the intercept (Egger et al., 1997), a test for asymmetry of the funnel plot. The trim-and-fill technique was used to adjust for a publication bias (Duval & Tweedie, 2000). Egger’s test was not conducted in the case of substantial heterogeneity due to its poor performance with high heterogeneity (Peters et al., 2010); additionally, Egger’s test cannot be calculated based on two studies. Furthermore, outliers were identified as studies from which the 95% confidence interval did not overlap with the 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect size. These outliers were only excluded if two authors (MV, RK) could argue that the study design was noticeably different from the other included studies.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

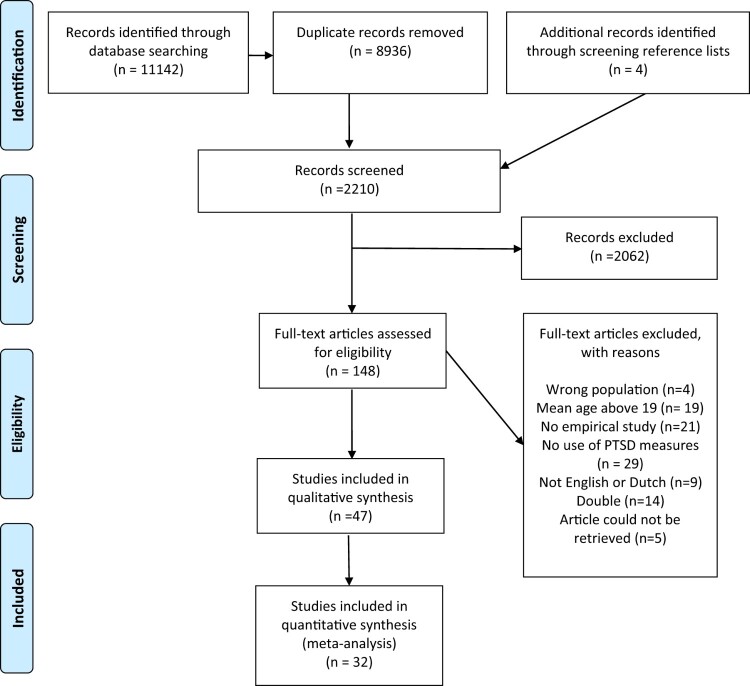

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram of the selection and inclusion process. In total, 2210 titles and abstracts were screened from which 148 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Forty-seven articles met all inclusion criteria. Two three-arm studies were included in the narrative review (Ertl et al., 2011; Thabet et al., 2005). For the meta-analysis, two arms from each study were selected based on the most frequently used trauma-focused treatments and a control group. Consequently, the analyses included NET versus waitlist (WL) (Ertl et al., 2011) and a crisis intervention group versus WL (Thabet et al., 2005). Fifteen studies were excluded from the meta-analysis. One study was removed due to overlapping treatment groups (Ellis et al., 2013). Four studies using the Wilcoxon rank test were excluded because Hedges’ g assumes normally distributed populations with equal variances (Fritz et al., 2012; Marfo & Okyere, 2019; Oras et al., 2004; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015). Similarly, Hedges’ g was not calculated for six studies with small samples (N = 2 to N = 7) (Onyut et al., 2005; Rondung et al., 2022; Said & King, 2020; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019; van Es et al., 2023) and case studies were not included (Bosqui et al., 2023; Schauer et al., 2004; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016). Four studies lacked sufficient data to calculate effect sizes, and attempts to obtain additional information from the authors were unsuccessful (Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020; Lempertz et al., 2020; Meyer DeMott et al., 2017; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Narrative review of findings

Below, an overview of findings from all included studies is presented (see Table 1). Participant and study characteristics, primary findings per treatment, and approaches to minimize (cultural) barriers in mental health care will be described.

3.2.1. Study characteristics

All 47 studies have been published between 2004 and 2023. The studies were conducted in Germany (n = 9), the USA (n = 5), Turkey (n = 4), Uganda (n = 3), Sweden (n = 3), the Netherlands (n = 3), Syria (n = 2), the UK (n = 2), Lebanon (n = 2), Gaza (n = 2), Finland (n = 2), and (n = 1) studies from Sri Lanka, the border of Syria and Turkey, Jordan, Germany, Bulgaria, Sierra Leone, Norway, Australia, Malaysia, and the border between Ethiopia and Somalia. Sample sizes ranged from N = 1 to N = 817. Participants originated from 28 different countries; their age ranged from 4 to 25 years.

The 47 primary studies employed various study designs: 25 studies used a pretest-posttest design, 14 studies adopted a RCT design, 6 studies used a non-randomized controlled trial design, 1 study a non-concurrent multiple-baseline design, and 1 study used a multiple N = 1 design. Nineteen studies used control groups. Six studies made a comparison with an active psychosocial treatment, such as meditation-relaxation (MED-RELAX) (Catani et al., 2009), child resilience building (Ellis et al., 2013), child centred play therapy (Schottelkorb et al., 2012), or treatment as usual (TAU) (Jordans et al., 2023; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019; Pfeiffer et al., 2018). The other CT and RCT studies assigned the control participants to a no-treatment group, such as a waitlist control group (Banoğlu & Korkmazlar, 2022; Ehntholt et al., 2005; Ertl et al., 2011; Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020; Feen-Calligan et al., 2020; Koch et al., 2020; Lange-Nielsen et al., 2012; Ooi et al., 2016; Panter-Brick et al., 2018; Rondung et al., 2022; Ruf et al., 2010; Thabet et al., 2005; Wadaa et al., 2010).

Used measures of PTSD diagnoses or complaints were self-report PTSD screeners such as the Children's Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-13) (Ehntholt et al., 2005; Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020; Garoff et al., 2019; Gupta & Zimmer, 2008; Jordans et al., 2023; King & Said, 2019; Kuiper & Uriakhel, 2020; Lange-Nielsen et al., 2012; Meyer DeMott et al., 2017; Mohlen et al., 2005; Ooi et al., 2016; Panter-Brick et al., 2018; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019; Perilli et al., 2019; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Pfeiffer & Goldbeck, 2017; Rondung et al., 2022; Sarkadi et al., 2018; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019; van Es et al., 2021; van Es et al., 2023), self-report questionnaires as the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Banoğlu & Korkmazlar, 2022; Bosqui et al., 2023; Cardeli et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2013; Feen-Calligan et al., 2020; Gormez et al., 2017; Grasser et al., 2019; Koch et al., 2020; Kubitary & Alsaleh, 2018; Murray et al., 2018; Oras et al., 2004; Said & King, 2020; Schauer et al., 2004), or a (semi-)structured interview to assess PTSD symptoms as the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents (CAPS-CA) (Catani et al., 2009; Ertl et al., 2011; Ruf et al., 2010; Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016). One study used parent-report questionnaires in addition to the self-report measures of the children (Schottelkorb et al., 2012). Three studies assessed PTSD symptoms using parent or teacher reports (Gotseva-Balgaranova et al., 2020; Lempertz et al., 2020; Wadaa et al., 2010).

3.2.2. Primary findings per treatment

Most studies examined the effects of evidence-based treatments, including CBT-based interventions (Bosqui et al., 2023; Ehntholt et al., 2005; Gormez et al., 2017; King & Said, 2019; Lange-Nielsen et al., 2012; Murray et al., 2018; Ooi et al., 2016; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Pfeiffer & Goldbeck, 2017; Rondung et al., 2022; Sarkadi et al., 2018; Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019), EMDR therapy (Banoğlu & Korkmazlar, 2022; Kuiper & Uriakhel, 2020; Lempertz et al., 2020; Oras et al., 2004; Perilli et al., 2019; Wadaa et al., 2010), and the child version of NET (KIDNET) (Catani et al., 2009; Ertl et al., 2011; Onyut et al., 2005; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019; Ruf et al., 2010; Said & King, 2020; Schauer et al., 2004). The primary findings of these studies will be described first, followed by the outcomes of the remaining interventions.

Fifteen studies examined the effects of CBT-based interventions. Significant reductions in posttraumatic stress symptoms were found at post-intervention and maintained at follow-up for up to 6 months for Trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) (Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019). Significant decreases in posttraumatic stress symptoms were observed for Teaching Recovery Techniques – a group-based CBT programme (Ehntholt et al., 2005; Ooi et al., 2016; Sarkadi et al., 2018). In one study, effects were maintained at 3-month follow-up (Ooi et al., 2016), while another study showed no sustained effects (Ehntholt et al., 2005). Decreases in posttraumatic stress symptoms were also reported for a school-based CBT group (focused on relaxation techniques, psychoeducation and trauma- and grief-related experiences), My Way (a trauma-focused group intervention for UCM’s including psychoeducation, relaxation, trauma narrative, and cognitive restructuring) and a common elements treatment approach (teaching CBT elements such as cognitive restructuring and behavioural activation) (Bosqui et al., 2023; Gormez et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2018; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Pfeiffer & Goldbeck, 2017). No evidence for improvements due to the intervention ‘writing for recovery’ regarding PTSS symptoms was found (Lange-Nielsen et al., 2012). At the time of the review, seven out of ten participants in the psychological skills group (a group focused on three key themes: physical health needs, emotional wellbeing, and resilience-building and empowerment, utilizing cognitive behavioural approaches), scored above the clinical threshold on the CRIES-8 (King & Said, 2019). Dropout ranged from 0.0% until 33.3%.

Six studies examined the effects of EMDR therapy, both group and individual treatment. EMDR therapy is an evidence-based trauma therapy. It involves recalling distressing memories, while performing a distractive task. All studies showed reductions in posttraumatic stress symptoms at posttreatment (Banoğlu & Korkmazlar, 2022; Kuiper & Uriakhel, 2020; Lempertz et al., 2020; Oras et al., 2004; Perilli et al., 2019; Wadaa et al., 2010). Two studies with 3-month follow-up measures showed these effects were maintained at follow-up (Kuiper & Uriakhel, 2020; Lempertz et al., 2020). Dropout ranged from 0.0% until 35.7%.

Seven studies investigated the effects of KIDNET. (KID)NET is an evidence-based treatment for individuals with multiple traumatic experiences, originally developed for low-resource, crisis-affected countries. The therapy involves creating a ‘lifeline,’ where positive experiences are represented by flowers and negative ones by stones. KIDNET aims to reduce PTSD symptoms through narrative exposure, helping children process traumatic memories by working chronologically through their lifeline. All studies demonstrated reductions in posttraumatic stress symptoms following treatment (Catani et al., 2009; Ertl et al., 2011; Onyut et al., 2005; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019; Ruf et al., 2010; Said & King, 2020; Schauer et al., 2004). Positive effects were maintained at follow-up for up to 12 months (Catani et al., 2009; Ertl et al., 2011; Onyut et al., 2005; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019; Ruf et al., 2010). Dropout ranged from 0.0% until 25.0%.

Finally, reductions in PTSD symptoms were observed for art therapy (Feen-Calligan et al., 2020; Meyer DeMott et al., 2017; Ugurlu et al., 2016), group thera-play (Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020), evidence-based trauma stabilization programme (Gotseva-Balgaranova et al., 2020), dance movement therapy (Grasser et al., 2019), Rapid-Ed (an intervention consisting of trauma healing modules, such as normalizing children's reactions to trauma or sharing war-related stories in pairs or small groups, and engaging in recreational activities) (Gupta & Zimmer, 2008), Skills-Training of Affect Regulation, a culture sensitive approach (STARC) (Koch et al., 2020), Training of Repeating Positive Thoughts (TRPT) (Kubitary & Alsaleh, 2018), a psychosocial treatment programme (including individual, family, and group sessions, combining a psychoeducational approach with trauma and grief-focused activities, creative techniques, and relaxation methods) (Mohlen et al., 2005), trauma reactivation under propranolol (Thierrée et al., 2020), tier 2–4 of a multi-tiered school-based programme (tier 2 focuses on resilience building through school-based groups, while tier 3 and 4 provide direct intervention using the Trauma Systems Therapy (TST) model) (Ellis et al., 2013), and a multimodal trauma-focused treatment approach, specifically adapted for UCMs, which includes psychoeducation, the creation of a lifeline (adapted from KIDNET), followed by an intervention module (such as CBT, EMDR, or stress regulation) tailored to the individual needs of the UCM (van Es et al., 2021). No significant difference between the control group and the trauma-focused group, or no decrease of PTSD symptoms, were observed for a group-based mental health intervention for UCM’s (focused on stabilizing and preventing mental health problems) (Garoff et al., 2019), the multimodal trauma-focused approach (van Es et al., 2023), Tier 2 of TST for refugees (Cardeli et al., 2020), a crisis intervention group (a group where children can talk, draw or write about their experience of trauma, losses suffered during the conflict, and the impact of trauma on their family, peers and their community), and an Early Adolescent Skills for Emotions group (focusing on psychoeducation, stress management techniques, behavioural activation strategies, problem solving strategies and relapse prevention) (Jordans et al., 2023; Thabet et al., 2005).

3.2.3. Approaches to minimize (cultural) barriers in mental health care

All included studies describe approaches to overcome (cultural) barriers, such as potential benefits of the chosen therapy for this specific population, cultural adaptations of protocols, and strategies to reach the target population or enhance treatment attendance, and to overcome language barriers.

Most studies selected treatments based on their suitability for this population, such as interventions designed for large groups in low-resource settings, those that use trained lay persons, are tested in culturally diverse settings, time-efficient, minimal language dependence, or are developed specifically for refugee populations (Banoğlu & Korkmazlar, 2022; Bosqui et al., 2023; Cardeli et al., 2020; Catani et al., 2009; Ehntholt et al., 2005; Ellis et al., 2013; Ertl et al., 2011; Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020; Feen-Calligan et al., 2020; Garoff et al., 2019; Gormez et al., 2017; Grasser et al., 2019; Koch et al., 2020; Lange-Nielsen et al., 2012; Mohlen et al., 2005; Murray et al., 2018; Onyut et al., 2005; Ooi et al., 2016; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019; Perilli et al., 2019; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Pfeiffer & Goldbeck, 2017; Rondung et al., 2022; Ruf et al., 2010; Said & King, 2020; Sarkadi et al., 2018; Schauer et al., 2004; Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019; van Es et al., 2021; van Es et al., 2023).

Cultural adaptations of protocols included enhanced psychoeducation (Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019), integration of cultural notes (Cardeli et al., 2020), addressing specific stressors (Mohlen et al., 2005; van Es et al., 2021; van Es et al., 2023) or cultural contexts (Bosqui et al., 2023; Jordans et al., 2023), adding grief components (Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019), including locally relevant symptoms in measures (Murray et al., 2018). Strategies to reach the target population included: involving key community members like imams (Perilli et al., 2019). To enhance attendance, treatments were offered at schools (Cardeli et al., 2020; Kubitary & Alsaleh, 2018; Ooi et al., 2016; Sarkadi et al., 2018; Thabet et al., 2005), or outreach care was offered at a familiar environment (van Es et al., 2021; van Es et al., 2023), child welfare programmes or at participants’ residences (Garoff et al., 2019; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Pfeiffer & Goldbeck, 2017; Rondung et al., 2022), refugee camps or other accommodations (Catani et al., 2009; Mohlen et al., 2005; Murray et al., 2018; Onyut et al., 2005; Schauer et al., 2004). Some studies arranged transportation or scheduled sessions on weekends (Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020; Feen-Calligan et al., 2020; Grasser et al., 2019; Panter-Brick et al., 2018).

Approaches to minimize language barriers included providing translated materials (Banoğlu & Korkmazlar, 2022; Gormez et al., 2017; Ooi et al., 2016; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019), working with translators (Banoğlu & Korkmazlar, 2022; Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020; Garoff et al., 2019; Gormez et al., 2017; Gotseva-Balgaranova et al., 2020; Grasser et al., 2019; King & Said, 2019; Koch et al., 2020; Kuiper & Uriakhel, 2020; Lempertz et al., 2020; Meyer DeMott et al., 2017; Mohlen et al., 2005; Onyut et al., 2005; Ooi et al., 2016; Oras et al., 2004; Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019; Perilli et al., 2019; Rondung et al., 2022; Ruf et al., 2010; Said & King, 2020; Sarkadi et al., 2018; Schauer et al., 2004; Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Ugurlu et al., 2016; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015; Unterhitzenberger, Fornaro, et al., 2019; Unterhitzenberger, Wintersohl, et al., 2019) or cultural mediators/cultural brokers (Cardeli et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2013; Perilli et al., 2019; van Es et al., 2021; van Es et al., 2023), who facilitate communication between therapists and participants from similar cultural backgrounds, addressing cross-cultural differences during treatment. In addition, treatment was delivered in participants’ native languages (Catani et al., 2009; Gormez et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2018) or questionnaires in participants’ languages were used (Catani et al., 2009; Eruyar & Vostanis, 2020; Feen-Calligan et al., 2020; Garoff et al., 2019; Gormez et al., 2017; Gotseva-Balgaranova et al., 2020; Gupta & Zimmer, 2008; Jordans et al., 2023; Koch et al., 2020; Kubitary & Alsaleh, 2018; Lange-Nielsen et al., 2012; Lempertz et al., 2020; Meyer DeMott et al., 2017; Mohlen et al., 2005; Murray et al., 2018; Panter-Brick et al., 2018; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Schauer et al., 2004; Thabet et al., 2005; Thierrée et al., 2020; Ugurlu et al., 2016; Wadaa et al., 2010).

3.3. Meta-analyses

Table 2 presents the summary of findings reporting the pooled effect sizes (Hedges’ g) using a random-effects model, and the heterogeneity index I-squared (I2). Forest plots can be found in the supplementary material (Figures S1–S8).

Table 2.

Treatment effects and heterogeneity indices.

| Hedges g (95% CI) | p | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies with a RCT or CT design (n) | |||

| All studies (n = 15), pt | −.83 (−1.31, −.36) | <.001a | 93% |

| All studies (n = 8), fu | −.52 (−.91, −.14) | <.001a | 78% |

| CBT-based intervention (n = 4), pt | −1.21 (−3.01, .59) | .19 | 97% |

| CBT-based intervention (n = 2), fu | −.31 (−.71, .09) | .12 | 0% |

| KIDNET (n = 4), pt | −.34 (−.69, −.00) | .05 | 14% |

| KIDNET (n = 3), fu | −.49 (−.85, −.12) | .01a | 0% |

| Studies with a pre-posttest design (n) | |||

| All studies (n = 17), pt | −.55 (−.70, −.40) | <.001a | 65% |

| All studies (n = 3), fu | −.97 (−1.82, −.11) | .03a | 84% |

| CBT-based intervention (n = 5), pt | −.55 (−.72, −.39) | <.001a | 0% |

| EMDR therapy (n = 2), pt | −1.63 (−2.28, −0.99) | <.001a | 0% |

Abbreviations: n, number of studies; CI, confidence interval; pt: analyses using posttreatment measures; fu: analyses using follow-up measures.

Combined effect sizes that are statistically significant (p < .05).

3.3.1. The efficacy of trauma-focused treatments grouped together

First, meta-analyses were conducted for studies that had adopted a controlled or randomized controlled design (n = 15), identifying five outliers (Jordans et al., 2023; Koch et al., 2020; Panter-Brick et al., 2018; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Wadaa et al., 2010), though none were removed. The I-squared statistic was high (I2 = 93, p < .001), and the effect size varied between small and large, indicating a high amount of heterogeneity. In studies with follow-up assessments (n = 8), I² was also high (I2 = 78, p < .001), with effect sizes ranging from small to large, again indicating high heterogeneity. Second, meta-analyses were conducted for studies that had adopted a pre- and posttest design (n = 17), with one outlier identified but not removed (Gupta & Zimmer, 2008). High heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 65, p < .001). The same held for the studies that included a follow-up assessment (n = 3) (I2 = 84, p = .00). The high level of heterogeneity makes the pooled effect size unreliable for interpretation.

3.3.2. The efficacy of specified trauma-focused treatments

To conduct meta-analyses for specified trauma-focused treatments, sufficient studies were available for CBT-based interventions, KIDNET, and EMDR therapy. For CBT-based interventions with a controlled design using posttreatment measures (n = 4), one study was identified as an outlier, but it was not excluded (Pfeiffer et al., 2018). High heterogeneity for these studies was observed (I2 = 97, p < .001). Those studies that included a follow-up assessment (n = 2), revealed a low I-squared statistic, that is, variation happened by change (I2 = 0, p = .94). Effect sizes varied between small and medium. The pooled effect size was small and not statistically significant (Hedges g = −.31; 95% CI:(−.71,.09), p = .12).

Studies with a controlled design assessing KIDNET at post-treatment (n = 4), demonstrated a low I-squared statistic (I2 = 14, p = .32). The pooled effect size was small to medium and not statistically significant (Hedges g = −0.34; 95% CI:(−.69, −.00), p = .05). The Egger’s test did not indicate a risk of publication bias (intercept = −2.91; 95% CI (−18.12,12.30), p = .50). At follow-up, the KIDNET studies (n = 3) revealed effect sizes that varied between small and large. The proportion of observed variance that reflected real differences in effect size was low (I2 = 0, p = .48). The pooled effect size was medium and statistically significant (Hedges g = −.49; 95% CI:(−.85,−.12), p = .01).

Next, meta-analyses were conducted for studies that had adopted a pre-posttest design; five CBT-based interventions and two EMDR interventions were included. For the CBT-based interventions, the proportion of observed variance that reflects real differences in effect size was low (I2 = 00, p = .49). The Egger’s test did not indicate a risk of publication bias (intercept = −4.02, 95% CI:(−9.82,1.78), p = .06). A medium and statistically significant effect size was found (Hedges g = −.55; 95% CI:(−.72,−.39), p < .001). For EMDR therapy, the two studies that were included, demonstrated a low I-squared statistic (I2 = 00, p = .87), and a large and statistically significant effect size was found (Hedges g = −1.63; 95% CI:(−2.28,−.98), p < .001).

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analyses study is a recent update of existing literature on the effectiveness of trauma-focused treatments for PTSD in refugee children and outlines strategies to mitigate barriers to mental health care. Our review included 47 studies, with 32 studies incorporated into the meta-analysis (including 2799 participants).

In the narrative review, a wide range of treatments is evaluated, emphasizing evidence-based therapies like CBT-based interventions, EMDR therapy, and KIDNET. The findings collectively suggest a large decrease of symptom reduction, with many studies showing lasting improvements over time. This indicates that established therapies, effective for the general population, also yield positive outcomes for refugee children. This review also recognizes the potential of other alternative approaches such as art therapy, indicating a need for more research to establish their effectiveness alongside more established interventions. All studies took deliberate steps to address the barriers refugee children face in accessing mental health care (e.g. strategies to improve attendance, cultural adaptations of protocols and treatments administered by trained lay persons). This information is important for policy and practice, as it highlights the need for inclusive care and recognizes the role of culture in treatment. In all, but five, studies dropout ranged between 0 and 25.0%, with KIDNET showing the lowest rates, demonstrating successful engagement with the target population, potentially facilitated by these adjustments. Future research is needed that focuses on explicitly measuring and evaluating these (cultural) adjustments to better understand their impact on recruitment, engagement and outcomes. This review offers an overview of factors to assess.

The meta-analyses showed a medium and statistically significant pooled effect size for CBT-based interventions with a pretest-posttest design. These positive findings are in line with previous literature on effectiveness of CBT-based interventions for refugee children (Chipalo, 2021; Nocon et al., 2017). The pooled effect size of CBT-based treatments with an RCT/CT design using post-treatment measures could not be meaningfully assessed due to high heterogeneity among the studies. The between-group effect size of the CBT-based interventions using follow-up measures (n = 2) showed a small, non-significant pooled effect size. This suggests either the analyses were underpowered or any positive effects did not persist at the 2 or 3-months follow-up. Both studies (Ehntholt et al., 2005; Ooi et al., 2016) evaluated Teaching Recovery Techniques, a group-based CBT programme. One study attributed the diminished follow-up effects to increased local violence and suggested that the six-session group format might have been too brief or diluted (Ehntholt et al., 2005). The other study excluded participants with clinical-level PTSD, potentially limiting the observed symptom reduction (Ooi et al., 2016).

The pooled effect size of RCT/CT studies analysing KIDNET (n = 4) using post-treatment measures, was small to medium and non-significant. This might be due to underpowered analyses, and notably, half of the studies used an active control group (e.g. MED-RELAX or TAU), which likely reduced the pooled effect sizes. However, studies that included follow-up measures (n = 3) showed a medium and statistically significant effect, indicating long-term efficacy of KIDNET. While NET's effectiveness in adults has been well-established, KIDNET shows promise for treating PTSD in children (Lely et al., 2019; Siehl et al., 2021), Siehl et al. (2021) found that RCTs using active controls showed small to medium effect sizes in the short term and large effect sizes in the long term, speculating that the impact of NET becomes more potent over time, a finding supported by the results obtained in this study.

A large and statistically significant pooled effect size was found for EMDR therapy based on studies with a pretest-posttest design. However, this finding is derived from only two studies with some serious disadvantages in study designs (small sample sizes, no use of a clinical interview, absence of a control group). Nonetheless, the significant findings are consistent with previous research supporting the effectiveness of EMDR therapy in treating PTSD in children, a method endorsed by international guidelines (de Jongh et al., 2024). While EMDR therapy has predominantly been tested and applied in Western contexts, these outcomes support the increasing evidence for its effectiveness and suitability for treating trauma symptoms across diverse cultural and ethnic groups, including non-Western settings (de Jongh et al., 2024).

4.1. Limitations

There are several limitations. The pooled effect sizes for all trauma-focused treatments grouped together could not be interpreted meaningfully due to high heterogeneity. The small number of studies in the meta-analysis prevented further subgroup analyses to explore potential mechanisms. Another limitation is the lack of risk of bias assessments for the included studies. Most studies had low quality, lacking control groups and randomization, reducing reliability of the results. The inclusion of different study designs necessitates the use of various standardized tools to assess risk of bias, complicating the ability to conduct a consistent and reliable evaluation. Therefore, no formal tool was used to assess risk of bias; risk of bias was inferred based on the study design alone. In addition, the use of pre–post effect sizes could result in biased outcomes (Cuijpers et al., 2017). However, due to the emerging nature of this field, we aimed to include the broadest scope of studies possible. Finally, this study focused on posttraumatic stress symptoms as outcome. As some interventions did not primarily or exclusively targeted posttraumatic stress outcomes, but included second outcome measures such as quality of life, the findings of this study may not comprehensively capture the overall impact of the included interventions.

4.2. Conclusion

The results indicate that evidence-based ‘western’ treatments for PTSD, such as CBT-based interventions and EMDR therapy, are efficacious for young refugees. Furthermore, evidence-based treatments specifically tailored to this group, such as KIDNET, demonstrate promising outcomes on the long term. Engaging this target population may necessitate the utilization of strategies to ensure accessibility. The number of children worldwide fleeing their homes to find safety elsewhere, has rapidly increased and has never been this high since the World War II (UNHCR, 2022). Testing and identifying effective treatments for the posttraumatic burden of the sequence of events, have become extremely important. While the findings are encouraging, more high-quality studies with rigorous designs, using control groups, structured clinical interviews, and longer follow-up assessments are urgently needed to provide more definitive treatment recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jonna Lind, librarian and information specialist at the ARQ National Psychotrauma Centre, for her assistance in designing and carrying out the literature searches.

Funding Statement

This study was part of a larger study funded by VEN, EMDR Europe, ZONMW and Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2025.2494362

References

- Banoğlu, K., & Korkmazlar, Ü. (2022). Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization and reprocessing group protocol with children in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in refugee children. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6(1), Article 100241. 10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosqui, T., McEwen, F. S., Chehade, N., Moghames, P., Skavenski, S., Murray, L., Karam, E., Weierstall-Pust, R., & Pluess, M. (2023). What drives change in children receiving telephone-delivered Common Elements Treatment Approach (t-CETA)? A multiple n = 1 study with Syrian refugee children and adolescents in Lebanon. Child Abuse & Neglect, 162(Pt 2), Article 106388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrow, Y., Pajak, R., Specker, P., & Nickerson, A. (2020). Perceptions of mental health and perceived barriers to mental health help-seeking amongst refugees: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 75, Article 101812. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardeli, E., Phan, J., Mulder, L., Benson, M., Adhikari, R., & Ellis, B. H. (2020). Bhutanese refugee youth: The importance of assessing and addressing psychosocial needs in a school setting. Journal of School Health, 90(9), 731–742. 10.1111/josh.12935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani, C., Kohiladevy, M., Ruf, M., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2009). Treating children traumatized by war and tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), Article 22. 10.1186/1471-244X-9-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipalo, E. (2021). Is trauma focused-cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) effective in reducing trauma symptoms among traumatized refugee children? A systematic review. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(4), 545–558. 10.1007/s40653-021-00370-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). The effect size. In Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (pp. 77–83). Routledge.

- Cowling, M. M., & Anderson, J. R. (2023). The effectiveness of therapeutic interventions on psychological distress in refugee children: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(8), 1857–1874. 10.1002/jclp.23479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P., Weitz, E., Cristea, I., & Twisk, J. (2017). Pre-post effect sizes should be avoided in meta-analyses. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26(4), 364–368. 10.1017/S2045796016000809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]