Abstract

Introduction:

Leishmaniasis is a potential concern for solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients, particularly those from endemic regions. Among SOT procedures, kidney transplantation (KT) is the most common. This study aims to synthesize the evidence about visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in KT candidates and recipients, with a focus on risk factors and associated outcomes.

Methods:

This integrative review analyzed studies from the past 20 years, focusing on disease profile, treatment, prognosis, and risk of asymptomatic infection.

Results:

A total of 32 articles were included. Of the KT recipients, 85.7% were male, with an average age of 42.5 years. The average timespan since symptom onset was 54.7 months. Renal function impairment was reported in 64% of patients, with an associated mortality rate of 15%. Post-treatment relapse occurred in 10–37.5% of patients. Among KT candidates, 13.9% were seropositive for Leishmania spp.

Conclusion:

VL is an infrequent condition among KT recipients, limiting the quality of the available evidence. Early detection and prompt treatment are crucial for improving outcomes. While renal function impairment is common, it rarely leads to graft rejection. In the reviewed studies, the coexistence of VL and cutaneous or mucocutaneous forms was linked to higher mortality. Recurrences are common and require individualized management strategies. Hemotransfusion poses a potential infection risk, although routine screening in blood banks is not yet recommended.

Keywords: Kidney Transplantation; Leish-maniasis, Visceral; Neglected Diseases; Immunocompromised Host

Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a neglected tropical parasitic disease, caused by a group of intracellular protozoa belonging to the Leishmania donovani complex, also known as “kala-azar”. These pathogens, transmitted by the bite of the female Phlebotomus or Lutzomyia sand fly, have tropism for reticuloendothelial cells, mainly those of the spleen, liver, and bone marrow 1 .

In transplant recipients, the use of immuno-suppressant agents is essential to prevent allograft rejection, which is associated with symptomatic manifestation of the infection through mechanisms that have not been fully elucidated and can reactivate asymptomatic infections 2, 3, 4 . Kidney transplant (KT) recipients may become infected through blood transfusion, allograft transmission, or further exposure to infected sand flies 4 . Information regarding asymptomatic VL in transplant candidates is scarce, and disease recognition in the transplant recipient may therefore be delayed 5 .

The diagnosis involves the identification of parasites mainly by microscopy (of the bone marrow and, less frequently, of the spleen). Culture isolation, rK39 rapid immunochromatographic test (antigen detection), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from peripheral blood or bone marrow 6 can also be used. Serology, through indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and direct agglutination test (DAT), is an option, although each test may present different levels of sensitivity and specificity 6 . The preferred treatment in these patients requires a systemic approach, and a reduction of the immunosuppression dose is often advisable. The drug of choice is liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) and, alternatively, pentavalent antimonials, which can cause kidney damage. Other less common options include miltefosine, pentamidine, and paromomycin 7 .

VL is an uncommon infection in the post-transplant period, even within endemic regions. Among solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients, VL is most frequently reported in KT, accounting for 77% of cases 1 . This finding likely reflects the higher prevalence of this type of transplant among SOT 4, 8 . Typically, VL infection causes fever, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, and weight loss. However, these are the classic but not universal manifestations of VL. In some cases, the disease can also lead to nephropathy, caused by inflammatory infiltration and glomerular sclerosis, which can lead to graft dysfunction in KT recipients 1, 5, 9 .

This study aimed to elucidate the current scientific knowledge on leishmaniasis infection and outcomes among KT candidates and recipients, emphasizing the adverse effects related to treatment and renal health in this population.

Methods

An integrative review was conducted to discuss the clinical profile and diagnosis of VL infection in KT candidates and recipients, in addition to outlining treatments and prognostic factors.

The search was conducted using the descriptors “(‘Visceral Leishmaniasis’) AND (‘Kidney Transplant’ OR ‘Renal Transplant’)” in three databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, and MEDLINE) in March 2024. The search covered the period from 2004–2024, selecting only articles in English. Case reports and series, retrospective cohorts, and systematic reviews were all included. Duplicates were manually removed and abstracts from conferences were excluded.

The inclusion criteria were studies describing patients with VL or asymptomatic Leishmania spp. infection diagnosed in KT recipients and candidates published in indexed journals. The exclusion criteria were studies focused on non-visceral forms of leishmaniasis (cutaneous and mucocutaneous), those involving non-KT patients or transplant types other than KT (e.g., liver or hematopoietic stem cell transplants), and manuscripts that failed to specify the transplant type.

The article selection process was conducted by two authors (OMVN and PYLM), and any uncertainties regarding inclusion or exclusion were discussed within the group of authors for consensus. The final list of selected articles was documented in a spreadsheet, which was managed by the authors, for subsequent data analysis.

Results

Included Studies

Figure 1 shows a flowchart detailing the selection process of studies included in this review.

Figure 1. Study selection flowchart. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart adapted for integrative reviews.

The authors categorized the manuscripts into subgroups as follows: case reports or series on KT recipients 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 ; observational studies on asymptomatic infection in KT candidates 5, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 ; observational studies on KT patients who developed VL 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 ; and a systematic review of VL in KT recipients 1 .

Epidemiology of VL in KT recipients, prevalence of asymptomatic infection in KT candidates, clinical and laboratory data, biopsy findings, therapeutic management, and relapses were observed in each of the included studies.

Epidemiology

The selection of articles yielded 20 articles from case reports and case series containing data from 25 patients (Table 1). Most reports originate from endemic countries such as those in the Mediterranean Basin, Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, and Iran 13 . Three patients reported travelling: one to Spain and Tunisia 12 , one to France and Morocco 19 , and one to Brazil and Thailand 25 .

Table 1. Data from case reports and small case series (<8 patients) of visceral leishmaniasis among kidney transplant recipients.

| Symptoms | Time after KT | SCr | CL/MC presentation | Country | Death | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Busutti et al. 9 , 2023 | Night sweat and fever | 18 | 3.7 | None | Italy | No | L-AmB |

| Rana et al. 10 , 2022 | Abdominal pain and weight loss | 48 | 2.5 | None | India | No | L-AmB |

| Marques et al. 11 , 2020 | Fever and oral ulcers | 108 | – | Both | Portugal | Yes | L-AmB |

| Dettwiler et al. 12 , 2010 | Fever, anorexia, weight loss, asthenia, and hepatoesplenomegaly | 69 | 2.71 | None | Travel to endemic area | Yes | L-AmB |

| Bouchekoua et al. 13 , 2014 | Fever, anorexia, asthenia, and weight loss | 17 | 4.18 | None | Tunisia | No | Glucantime |

| Kardeh et al. 14 , 2023 | Fever, chills, and malaise | 23 | 1.61 | None | Iran | No | L-AmB |

| Madhyastha et al. 15 , 2016 | Fever and oral ulcers | 62 | 4.3 | MC | India | No | L-AmB |

| Sánchez et al. 16 , 2018 (Case 1) | Fever and adenopathies | 24 | – | None | Spain | No | L-AmB |

| Sánchez et al. 16 , 2018 (Case 2) | Fever | 192 | – | None | Spain | No | L-AmB |

| Simon et al. 17 , 2011 (Case 1) | Oral ulcers | 120 | – | MC | Italy | Yes | L-AmB |

| Simon et al. 17 , 2011 (Case 2) | Fever and general deterioration | 204 | – | CL | Italy | No | L-AmB* |

| Zumrutdal et al. 18 , 2010 | Fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and weight loss | 60 | 2,2 | None | Turkey | No | L-AmB/ Allopurinol* |

| Duvignaud et al. 19 , 2015 | Fever, asthenia, and diarrhea | 72 | 1.54 | None | Travel to endemic area | No | L-AmB/Pentamidine |

| Yücel et al. 20 , 2013 | Fever and skin papules | 84 | – | CL | Turkey | Yes | L-AmB |

| Pedroso et al. 21 , 2014 | Fever, chills, and indisposition | 192 | – | None | Italy | Yes | L-AmB* |

| Oliveira et al. 22 , 2008 (Case 1) | Fever, asthenia, anorexia, and diarrhea | 5 | 1.8 | None | Brazil | No | L-AmB |

| Oliveira et al. 22 , 2008 (Case 2) | Fever, chills, anorexia, and weight loss | 36 | 2.5 | None | Brazil | No | L-AmB |

| Oliveira et al. 22 , 2008 (Case 3) | Fever, anorexia, asthenia, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly | 36 | 1.2 | None | Brazil | No | L-AmB |

| Oliveira et al. 22 , 2008 (Case 4) | Diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, asthenia, anorexia, and fever | 8 | 2.7 | None | Brazil | No | L-AmB |

| Rancan et al. 23 , 2022 | Diarrhea, fever, and hepatosplenomegaly | 48 | – | None | Brazil | Yes | L-AmB |

| Jha et al. 24 , 2012 | Fever, cervical lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly | 84 | 1.1 | MC | Nepal | No | L-AmB |

| Pêgo et al. 25 , 2013 | Fever, indisposition, weakness, night sweat, and cachexia | 17 | 1.48 | None | Travel to endemic area | No | L-AmB |

| Prasad et al. 26 , 2011 | Fever, asthenia, and myalgia | 84 | 5.2 | None | India | No | L-AmB |

| Gembillo et al. 27 , 2021 | Anemia, fever, and urinary retention | 36 | 4 | None | Italy | No | L-AmB |

| Keitel et al. 28 , 2018 | Fever, myalgia, weight loss, weakness, and splenomegaly | 33 | – | None | Brazil | No | L-AmB |

Abbreviations – KT: kidney transplant; SCr: serum creatinine (mg/dL) at diagnosis; CL/MC: presence of cutaneous (CL); mucocutaneous (MC) manifestations.

Note – *VL recurrence after first treatment. “—” refers to the absence of data.

Furthermore, the 4 observational studies docu-mented in the literature, gathered in Table 2, provide data from 66 patients in total. The patients in Tables 1 and 2 were of an average age of 42.52 (18–75) years; 78 of the patients (85.71%) were male.

Table 2. Data from observational studies (≥8 patients) of visceral leishmaniasis among kidney transplant recipients.

| Oliveira et al. (2008) 38 | Basset et al. (2005) 37 | Da Silva et al. (2013) 36 | De Silva et al. (2015) 35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | (n = 8) | (n = 8) | (n = 20) | (n = 30) |

| Location | Ceará (Brazil) | France | Ceará/Piauí (Brazil) | Ceará/Piauí (Brazil) |

| Male (%) | 87.5 | 50 | 90 | 80 |

| Average age | 35.5 ± 11.2(22−57) | 52.8 ± 8.1(38−67) | 37 ± 10.7(18–60) | 40 ± 10.5(22−60) |

| Previous blood transfusion (%) | – | – | 50 | 43.3 |

| Fever (%) | 100 | 75 | 100 | 70 |

| Splenomegaly (%) | 100 | 12.5 | 100 | 93.3 |

| Hepatomegaly (%) | 100 | 12.5 | – | 70 |

| Weight loss (%) | 100 | 62.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Skin Lesions (%) | – | – | 80 | 83.3 |

| Bone Marrow Microscopy+ (%) | 87.5 | 75 | 95 | 63.3 |

| rK39+ (%) | 37.5 | – | 20 | 16.7 |

| Cure (%) | 100 | 87.5 | 85 | 80 |

| VL remission with dialysis (%) | – | – | 10 | – |

| Relapse (%) | 37.5 | 12.5 | 10 | 26.7 |

| Death (%) | 0 | 12.5 (refused treatment) | 15 | 16.7 |

| Treatment-associated nephrotoxicity | 37.5% (before treatment, mean SCr was 2.58) | – | 95% with SCr >30% elevated | On the 2nd day of VL remission, the mean SCr value reached 2.21 |

Abbreviations – VL: visceral leishmaniasis; SCr: serum creatinine (mg/dL) at diagnosis.

Asymptomatic Infection by Leishmania spp. in KT Candidates

In total, 1,348 KT candidates were included in the studies shown in Table 3, all from endemic areas for VL. Studies that compared diagnostic methods had conflicting results 5, 29, 30 . Furthermore, among the 1,348 patients, 188 (13.9%) tested positive in at least one of the diagnostic tests. Three studies explored the exposure of patients to blood transfusion 29, 30, 32 . In these studies, 34.8% of the 89 infected patients had undergone previous blood transfusions, and 14.1% of the 240 patients who received transfusions had positive serology for Leishmania spp.

Table 3. Data from observational studies on asymptomaticLeishmania spp.infection in KT candidates.

| Country | Nº of patients | Average age (years) | Male (%) | Received transfusion | Test results (positivity) | Positive test result and past transfusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comai et al. (2021) 5 | Italy | 119 | 70±13.55 (20-94) | 61 | — | 19 (16.0%): 17 WB+ and 3 PCR+ (one patient WB and PCR) | — |

| Menike et al. (2022) 29 | Sri Lanka | 124 | 44.48±11,36 (18-72) | 81.4 | 115 | 4 (2.4%): 2 DAT+ and 2 rK39+ | 4 (100%) |

| França et al. (2020) 30 | Brazil | 50 | 32±10 (20-72) | 60 | 30 | 16 (32.0%): all IFAT+ | 10 (62.5%) |

| Deni et al. (2024) 31 | Italy | 120 | — | 64.1 | — | 50 (41.7%): 9 WB+, 32 WBA+, and 4 PCR+ | — |

| Souza et al. (2009) 32 | Brazil | 310 | — | 52.9 | 81 | 69 (22.3%): all IFAT+ | 17 (24.6%) |

| Elmahallawy et al. (2015) 33 | Spain | 625 | 49 (11–81) | 64.0 | — | 30 (4.8%): all IFAT+ | — |

Abbreviations - KT: Kidney Transplant. VL: Visceral Leishmaniasis. L-AMB: Liposomal Amphotericin B. PAHO: Pan American Health Organization.

Clinical and Laboratory Data

As seen in Table 1, the average time of symptom onset was 54.7 months post-transplant. Most cases had symptoms within less than 5 years post-transplant (60.6%). Only 4 cases reported the interval between symptom onset and VL diagnosis, with an average of 16 days (variation of 7–28 days) 9, 25, 26, 27 .

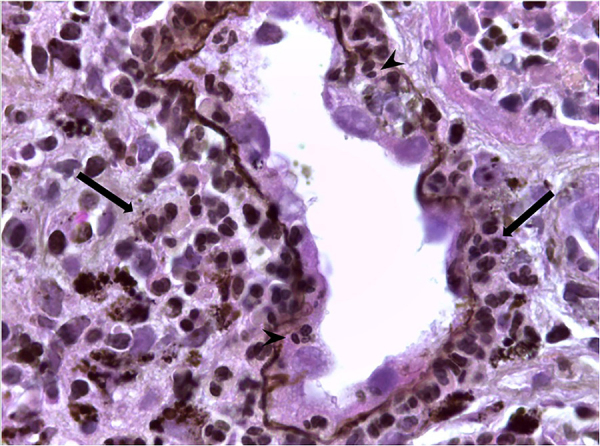

In the 25 case reports, the main diagnostic tests utilized were: bone marrow microscopy (73.9% positivity - illustrated in Figure 2); PCR (100%); and serology methods (77.8%). Only one study employed rK39 testing 29 . These data are not presented in Table 1.

Figure 2. Bone marrow biopsy (A) and aspirate (B) (hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), 1000x) showing interstitial macrophages containing numerous rounded microorganisms (amastigotes) in the cytoplasm (arrows), compatible with Leishmania spp. (Fazzio CSJ and Farias LABG with permission).

Symptoms and laboratory tests were analyzed in each patient of Table 1: thrombocytopenia (84%), leukopenia (84%), bicytopenia (84%), anemia (80%), pancytopenia (80%), fever (65.7%), splenomegaly (64%), fatigue (44%), weight loss (40%) 10, 12, 13, 14, 18, 22, 25, 28 hepatomegaly (24%), anorexia (20%), diarrhea (16%) 10, 19, 22, 38 , and lymphadenopathy (16%) 12, 16, 17, 24, 38 were common findings. The prevalence of the main symptoms mentioned in the large cohorts is detailed in Table 2. Furthermore, in some cases, there were associations between VL and cutaneous (12%) 11, 17, 20 and/or mucocutaneous (16%) 11, 15, 17, 24 forms.

In terms of mortality associated with VL, taking into consideration a maximum of 2 years between first diagnosis and death, a rate of 20% was found for the cases in Table 1, and varied from 0–16.7% for the cases in Table 2. In Table 1, for patients who developed only VL, the mortality rate was 15%, while for those who presented either the cutaneous or mucocutaneous form, a mortality rate of 33.3% was found.

Kidney Biopsy Findings

Only 5 (20.0%) of the 25 patients in Table 1 underwent a kidney biopsy, and two of them were due to kidney injuries not associated with VL 17, 19 . Among the three patients with renal damage attributable to VL, the following findings were observed: diffuse interstitial fibrosis with tubular atrophy, moderate chronic interstitial inflammation, glomerulosclerosis, chronic vascular damage, and identification of Leishmania spp. kinetoplastic DNA (kDNA), without amastigotes 9 ; glomerulosclerosis, along with moderate diffuse inflammation, in addition to amastigotes inside macrophages 12 ; and chronic nephropathy, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, along with segmental and focal glomerulosclerosis (SFGS) 23 .

Management

As shown in Table 1, the treatment of choice for VL in KT recipients was L-AmB, due to its lower risk of nephrotoxicity and effectiveness 18 , with doses ranging from 3 to 5 mg/kg and a duration ranging from 5 to 10 days. Only one patient received secondary prophylaxis after the initial diagnosis with monthly L-AmB dose of 3 mg/kg 12 . In cases of relapse, a new regimen with L-AmB was initiated. In case of intolerance or therapeutic failure, patients were switched to alternative medications (glucantime, pentamidine or miltefosine) 12, 17, 19, 23 . In the remaining cases, treatment started with second-choice drugs, due to the unavailability of L-AmB (more expensive) 26, 38 . L-AmB usually provides a transient increase in SCr 36 . Seventy-two percent of patients in Table 1 (who reported renal function) had an increase in SCr during or after treatment with L-AmB. However, some patients already had changes in kidney function with symptoms since admission, and in some cases there was no report on kidney function after the adopted therapy.

Six (24%) out of 25 patients from Table 1 reported nephrotoxicity 9, 12, 19, 21, 23, 25 . Four of them were treated primarily with L-AmB. In one case, L-AmB was delayed 25 and in another, glucantime was used as prophylaxis 23 . Two patients presented pancreatitis attributed to pentavalent antimony 13, 23 .

Relapses

Relapse was defined as a recurrence of signs and symptoms from 1–24 months after completing successful therapy 39 . Of the 25 cases in Table 1, recurrences were observed in 3 cases (12%). Of the cases with recurrences, 1 (33.3%) progressed to death 21 . Notably, one case had five relapses 23 , eventually leading to death 18 . Only one of the patients with relapses started secondary prophylaxis, with L-Amb at a dose of 4 mg/kg for 4 weeks after the first recurrence 18 . In Table 2, a total of 66 patients are reported, and the relapse rate ranged from 10–37.5%.

Discussion

In this review, KT recipients with VL were from or had traveled to countries classified as leishmaniasis-endemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) 40 . However, with climate change, the concept of “endemic country” may vary 41 . In transplant patients, VL can develop through three main mechanisms: (1) new infection in an immunocompromised recipient, especially after travelling to endemic regions; (2) reactivation of an asymptomatic infection triggered by immunosuppressive drugs; and (3) iatrogenic transmission via the transplanted organ 42, 43 or blood products 4 .

Table 3 shows the prevalence of asymptomatic carriers among KT candidates 8 . In the present study, the frequency of asymptomatic infection in KT candidates was not significantly higher than the general population (13.9% in Table 3 vs. 11.2% in meta-analysis 44 ). The current guidelines do not recommend serological screening for asymptomatic infection in organ donors, transplant recipients, or candidates, including those in endemic countries 6, 45, 46, 47 . However, this is a controversial topic, and the lack of agreement on methods, the inability to distinguish previous exposure from active infection, and the potential cross-reaction with other protozoa all limit the use of serological screening 6 . Nevertheless, if an available donor is known to be seropositive, it is advisable to perform clinical and laboratory monitoring of the recipient in the post-transplant period rather than to reject the organ for transplant (Table 4) 45 . Table 3 also presents test results (serological and molecular) used for screening, and there is a notable discrepancy in methods and results 5, 31 . For this reason, this review was not designed to compare screening methods. Sensitivity and specificity vary according to the methods chosen, the antigens used, and the geographical area 6, 51 . Nevertheless, different methods have been proposed 31, 52 , and results usually present high positivity 4 , although prospective studies with a greater number of patients from endemic and non-endemic areas are still needed.

Table 4. Visceral leishmaniasis management in the context of kidney transplantation.

| Situation | Formal Recommendation | Explanation/Discussion |

|---|---|---|

| Screening for Leishmania spp. in blood banks | Not included in systematic screening in blood banks 2, 48 . | There are no gold-standard methods established for screening of asymptomatic infection 49 . Leukoreduction has been proposed to reduce transfusion-transmitted leishmaniasis 2 . |

| Screening for VL in donor and recipient | Not included in routine systematic screening. A known asymptomatic infection in the donor should not reject the organ for transplant 45 | There are no gold-standard methods established for screening of asymptomatic infection 7, 49 . Proven transmission through organ grafts is exceptional 42, 43 , therefore, routine screening of donors is not recommended 49 . However, a known positive serology of the organ donor or recipient may indicate a closer follow-up and early treatment of the recipient, if disease is suspected 45 . |

| Primary prophylaxis for VL among KT recipients | Neither primary prophylaxis nor preventive treatment is recommended in asymptomatic patients 7, 45 . | — |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL among KT recipients | Secondary prophylaxis with L-AmB can prevent relapses in recurrent cases 7, 45 . It should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and frequent clinical follow-up is recommended 50 . | Posology: L-AmB, 3 mg/kg/dose every 2–3 weeks 45, 50 . |

| Preferred treatment for VL in KT recipients | L-AmB is the drug of choice, along with immunosuppression reduction during treatment 3, 7, 45 . | Food and Drug Administration: 4

mg/kg/day IV in days 1–5, 10, 17, 24, 31 e 38 (total dose of 40 mg/kg)

45

. PAHO: 3 mg/kg/day IV up to 20–40 mg/kg total dose 50 . |

| Management of VL treatment-associated nephropathy | Premedication; saline loading; dose testing; slow infusions (2–6 h); electrolyte supplementation, increased intervals between doses, and/or drug holidays, if indicated 45 . Avoid/minimize use of other nephrotoxic agents 45 . | PAHO guidelines emphasize strict renal function monitoring during treatment, especially in immunocompromised patients 50 . |

Notes - VL infection was considered based on a positive result in any of the tests. RK39+: number of patients who tested positive for RK39-ELISA. DAT+: number of patients who tested positive for direct agglutination test. WB+: number of patients who tested positive for specific igg western-blot method ANTI-LEISHMANIA. PCR+: number of patients who tested positive for dna polymerase chain reaction of the LEISHMANIA SPP. KINETOPLAST. IFAT+: Number Of Patients Who Tested Positive For ANTI-LEISHMANIA SPP. Antibody Immunofluorescence Test. WBA+: number of patients who tested positive for WHOLE BLOOD ASSAY.

Cytokine release assays (such as the interferon gamma release assay - IGRA) have been increasingly studied to detect asymptomatic infection and clinical cure after treatment of patients receiving immunosuppressive agents 53 . To the best of our knowledge, only one such study shows promising accuracy for this screening method, and its clinical applicability remains uncertain 54 .

A prospective cohort suggests that the screening of donors and recipients could be performed in cases at high risk of transmission or reactivation, and PCR could thus be a tool with greater specificity 46 . Nonetheless, this study is small, PCR positivity may be transient, and a positive result in the recipient does not necessarily predict disease development 46 . One case report of a lung transplant recipient shows that VL could have been diagnosed months before the development of symptoms by quantitative PCR, suggesting its role in early diagnosis 55 .

In three cohorts (see Table 3), 34.8% of infected KT candidates had a history of transfusion, and 14.1% of the blood transfused patients tested positive for Leishmania spp 29, 30, 32 . Although rare, transfusion-transmitted leishmaniasis has been previously described in the literature 56, 57, 58 , and blood transfusions may be a source of infection for KT candidates and recipients 13 . The occurrence of previous transfusions in these studies remains to be detailed, given their well-established role in the pathogenesis of leishmaniasis 4, 57 . Current guidelines, including the WHO, do not universally recommend screening for VL in blood banks, even in endemic regions (Table 4) 48 .

Tables 1 and 2 focus on clinical data. Fever, weight loss, splenomegaly, and pancytopenia are considered classic symptoms of VL, but may not always be present. Atypical manifestations may delay diagnosis 46 . In a recent large systematic review of Leishmania infection in KT recipients, classic manifestations were present in more than 90% of patients 1 . Nevertheless, the clinician needs to be aware of atypical presentations. Furthermore, serology should always be used at least as a first-line method of diagnosis in transplant recipients whenever VL is suspected 4 . It is possible that the inhibition of cellular immunity may affect clinical presentation and outcomes, as suggested in patients with co-infection with VL and acquired immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 59, 60 , but experimental studies to support this hypothesis are seriously lacking in the SOT population. Despite that, it is formally suggested to reduce immunosuppression during VL treatment 1, 45 , as with any opportunistic infection. A higher mortality is observed in this group of patients. The rate can be increased when VL is associated with a cutaneous or mucosal presentation (33.3% vs. 15% of mortality in isolated VL, in Table 1). The reason for this is not fully understood, but it is reasonable to consider a more severe and disseminated disease.

The impact of VL in renal function is presented in Tables 1 and 2, with increased levels of SCr at diagnosis. A retrospective study found an increase of more than 30% in SCr in 95% of KT recipients with VL 36 . Irreversible renal dysfunction was a rare event, occurring in only one patient, and was also associated with antimony nephrotoxicity 23 . Kidney damage has a complex physiopathology. Francesco Daher et al. 61 describe the formation of systemic and in situ immune complexes in leishmaniasis nephropathy, emphasizing their interaction with glomerular antigens and the involvement of inflammatory cells. Figure 3 shows some patterns of leishmaniasis nephropathy. The biopsy aims to determine the cause of kidney injury, but it is challenging to distinguish between the effects of parasitic infection, drug-induced nephrotoxicity, or graft rejection. Glomerular lesions (especially FSGS) and tubulointerstitial nephritis are common patterns in VL nephropathy 62 . Additionally, in this review, interstitial involvement was also common and associated with mononuclear infiltrate and tubular atrophy 61 . Although uncommon 63 , parasites were seen in a kidney biopsy of one of the cases 12 .

Figure 3. Renal biopsy showing visceral leishmaniasis-associated nephropathy (Methenamine Silver, 400x). Tubule and interstitium with inflammatory infiltrate, mostly composed of lymphocytes and macrophage (larger arrows); acute tubular epithelial degenerative changes and tubulitis (smaller arrows). (Baptista MASF with permission).

Overall, immunosuppression should be reduced during the anti-VL treatment, but this depends on a case-by-case assessment 7, 45 . Indications for primary and secondary prophylaxis are not yet defined, but possible approaches are presented in Table 4 45, 50 . There is a scarcity of randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses of VL treatment, especially in immunosuppressed populations without HIV, and guidelines are based on extrapolations of reports and small case series 50 . Current treatment recom-mendations are mostly based on expert opinion, but the preferred treatment option is L-AmB (Table 4) 7, 45, 50 . However, it is occasionally necessary to resort to alternative medications due to either intolerance or lack of availability of L-AmB, and patients should be carefully monitorized 7, 45, 50 . Nephrotoxicity is a major concern in these patients due to pre-existing kidney function impairment. L-AmB is preferred over amphotericin deoxycholate for its lower toxicity 7, 45 . The management and monitoring of L-AmB nephrotoxicity are shown in Table 4 7, 19 . Other drug options may be considered 7 .

Moreover, 12% of patients experienced relapses, with a mortality rate of 33.3% (Table 1). Relapse rates in larger series were similar, ranging from 10% to 37.5% (Table 2) 4 . Monitoring immunosuppressed patients with VL for relapses is recommended for at least one year following diagnosis 4, 45 . This follow-up should be guided by clinical and laboratory assessments, depending on availability 45, 50 .

This review has inherent limitations due to its retrospective nature and reliance on the quality of clinical records for data accuracy. The studies included were conducted over an extended period of time, potentially leading to variability in findings. Additionally, some cases may have been duplicated in individual case reports and larger series. The aim of this review was to focus in VL within the KT scenario, but there is a scarcity of studies on asymptomatic candidates and the impact of previous infection. The lack of uniformity among these studies limits direct comparisons. The role of immunosuppression on the serological diagnosis and outcomes of VL in SOT recipients is also challenging, particularly due to the lack of immunological studies. Finally, given that VL in KT recipients is a rare occurrence, even in endemic regions, the statistical power of the conclusions of this review is significantly limited. Nonetheless, the study highlights important considerations regarding screening and the risk of disease development in this specific group of patients. Although VL is rare among transplant recipients and often neglected even in endemic areas, early identification and appropriate treatment are crucial for improving survival outcomes.

Conclusion

This integrative review assessed the clinical profile of VL in KT recipients and candidates, emphasizing the limited data available for this group. Most VL cases displayed typical presentations, although atypical forms were challenging to diagnose. Concomitant mucocutaneous involvement was associated with higher mortality rates. Serological tests are not routinely performed for the screening of asymptomatic infection, and KT candidates did not show a higher prevalence of latent infection compared to the general population. While renal function may decline due to the disease or its treatment, graft loss remains uncommon. Blood transfusions could increase the risk of infection, but routine screening in blood banks for donors or recipients is not currently recommended. Further studies are needed in order to better understand the role of immunosuppression and secondary prophylaxis in VL management.

Acknowledgments

The group would like to thank the esteemed team of professors and staff from the Federal University of Ceará, the São José do Rio Preto Base Hospital, and the Federal University of Minas Gerais for their invaluable contributions and extensive expertise, which were instrumental in the development of this work. Special thanks to the illustrious Dr. Luís Arthur Brasil Gadelha Farias for generously providing Figure 2, which greatly enriched this study.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request and in the manuscript tables.

References

- 1.Favi E, Santolamazza G, Botticelli F, Alfieri C, Delbue S, Cacciola R, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, diagnostic work up, and treatment options of leishmania infection in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(10):258. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7100258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira LQ, Tanaka SCSV, Ferreira-Silva MM, Vânia F, Santana MP, Aguiar R, et al. Leukoreduction as a control measure in transfusion transmission of visceral leishmaniasis. Transfusion. 2023;63(5):1044–1049. doi: 10.1111/trf.17308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griensven JV, Carrillo E, López-Vélez R, Lynen L, Moreno J. Leishmaniasis in immunosuppressed individuals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(4):286–299. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antinori S, Cascio A, Parravicini C, Bianchi R, Corbellino M. Leishmaniasis among organ transplant recipients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comai G, Pascali De AM, Busutti M, Morini S, Ortalli M, Conte D, et al. Screening strategies for the diagnosis of asymptomatic Leishmania infection in dialysis patients as a model for kidney transplant candidates. J Nephrol. 2021;34(1):191–195. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00705-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemente WT, Mourão PHO. In: Emerging transplant infections. Morris M, Kotton C, Wolfe C, editors. Cham: Springer; 2020. Leishmaniasis in transplant candidates and recipients: diagnosis and management. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemente WT, Mourão PHO, Aguado JM. Current approaches to visceral leishmaniasis treatment in solid organ transplant recipients. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018;16(5):391–397. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1473763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemente W, Vidal E, Girão E, Ramos ASD, Govedic F, Merino E, et al. Risk factors, clinical features and outcomes of visceral leishmaniasis in solid-organ transplant recipients: a retrospective multicenter case-control study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(1):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busutti M, Deni A, Pascali De AM, Ortalli M, Attard L, Granozzi B, et al. Updated diagnosis and graft involvement for visceral leishmaniasis in kidney transplant recipients: a case report and literature review. Infection. 2023;51(2):507–518. doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01943-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rana A, Gadde A, Lippi L, Bansal SB. Visceral leishmaniasis after kidney transplant: an unusual presentation and mode of diagnosis. Exp Clin Transplant. 2022;20(3):311–315. doi: 10.6002/ect.2021.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marques N, Bustorff M, Cordeiro Da Silva A, Pinto AI, Santarém N, Ferreira F, et al. Visceral dissemination of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in a kidney transplant recipient. Pathogens. 2020;10(1):18. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dettwiler S, McKee T, Hadaya K, Chappuis F, Van Delden C, Moll S. Visceral leishmaniasis in a kidney transplant recipient: parasitic interstitial nephritis, a cause of renal dysfunction. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(6):1486–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchekoua M, Trabelsi S, Ben Abdallah T, Khaled S. Visceral leishmaniasis after kidney transplantation: report of a new case and a review of the literature. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2014;28(1):32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kardeh S, Masjedi F, Faezi-Marian S, Shamsaeefar A, Torabi Jahromi M, Pakfetrat M, et al. An atypical course of visceral leishmaniasis after kidney transplantation: a case report from Iran. Transplant Proc. 2023;55(8):1924–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2023.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahesh E, Varma V, Gurudev K, Madhyastha PR. Mucocutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in renal transplant patient from nonendemic region. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(5):1059–1062. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.190903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sánchez FC, Sánchez TV, Díaz MC, Moyano VES, Gallego CJ, Marrero DH. Visceral leishmaniasis in renal transplant recipients: report of 2 cases. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(2):581–582. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon I, Wissing KM, Del Marmol V, Antinori S, Remmelink M, Nilufer Broeders E, et al. Recurrent leishmaniasis in kidney transplant recipients: report of 2 cases and systematic review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13(4):397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zümrütdal A, Erken E, Turunç T, Çolakoğlu Ş, Demıroğlu YZ, Özelsancak R, et al. Delayed and overlooked diagnosis of an unusual opportunistic infection in a renal transplant recipient: visceral leishmaniasis. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2010;34(4):183–185. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2010.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duvignaud A, Receveur MC, Ezzedine K, Pistone T, Malvy D. Visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum in a kidney transplant recipient living in France. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13(1):115–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yücel S, Özcan D, Seçkin D, Allahverdiyev AM, Kayaselçuk F, Haberal M. Visceral leishmaniasis with cutaneous dissemination in a renal transplant recipient. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(6):892–893. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedroso JA, Salerno MP, Spagnoletti G, Bertucci-Zoccali M, Zaccone G, Bianchi V, et al. Elderly kidney transplant recipient with intermittent fever: a case report of leishmaniasis with acute kidney injury during liposomal amphotericin B therapy. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(7):2365–2367. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira RA, Silva LSV, Carvalho VP, Coutinho AF, Pinheiro FG, Lima CG, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis after renal transplantation: report of 4 cases in northeastern Brazil. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10(5):364–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2008.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rancan EA, Martins CPA, Araújo IM, Pavanetti LC, Ribeiro CA, Suzuki RB, et al. Recurrent American visceral leishmaniasis in a kidney transplant recipient: a case report. Rev Cubana Med Trop. 2022;74(2) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vankalakunti M, Siddini V, Babu K, Ballal S, Jha P. Postrenal transplant laryngeal and visceral leishmaniasis - A case report and review of the literature. Indian J Nephrol. 2012;22(4):301–303. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.101259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pêgo C, Romãozinho C, Santos L, Macário F, Alves R, Campos M, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: an unexpected diagnosis during the evaluation of pancytopenia in a kidney transplant recipient. Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension. 2013;27(2):119–123. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad N, Gupta A, Sharma R, Gopalakrishnan S, Agrawal V, Jain M. Cytomegalovirus and Leishmania donovani coinfection in a renal allograft recipient. Indian J Nephrol. 2011;21(2):128–131. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.78064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gembillo G, D’Ignoto F, Salis P, Santoro D, Liotta R, Barbaccia M, et al. POS-720 atypical cause of pancytopenia in a kidney transplant patient. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(4):S314–S315. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keitel E, Bruno RM, Zanetti H, Meinerz G, Jacobina LP, Silva AB, et al. Adenovirus nephritis followed by visceral leishmaniasis in a renal transplant recipient. Transplantation. 2018;102(Suppl 7):S661–S671. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000543593.55169.e9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menike C, Dassanayake R, Wickremasinghe R, Seneviwickrama M, Alwis ID, Abd A, et al. Assessment of risk of exposure to leishmania parasites among renal disease patients from a renal unit in a Sri Lankan endemic leishmaniasis focus. Pathogens. 2022;11(12):1553–1553. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11121553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.França ADO, Masselli G, Oliveira LP, Raquel L, Mendes RP, Elizabeth M. Presence of anti-Leishmania antibodies in candidates for kidney transplantation. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deni A, Mistral A, Ortalli M, Balducelli E, Provenzano M, Ferrara F, et al. Identification of asymptomatic Leishmania infection in patients undergoing kidney transplant using multiple tests. Int J Infect Dis. 2024;138:81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Souza RM, Braullio I, Câmara V, Costa K, Pereira R, Almeida JB, et al. Presence of antibodies against Leishmania chagasi in haemodialysed patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(7):749–751. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elmahallawy EK, Cuadros-Moronta E, Liébana-Martos MC, Rodríguez-Granger JM, Sampedro-Martínez A, Agil A, et al. Seroprevalence of Leishmania infection among asymptomatic renal transplant recipients from southern Spain. Transpl Infect Dis. 2015;17(6):795–799. doi: 10.1111/tid.12444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veroux M, Corona D, Giuffrida G, Cacopardo B, Sinagra N, Tallarita T, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in the early post-transplant period after kidney transplantation: clinical features and therapeutic management. Transpl Infect Dis. 2010;12(5):387–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Silva AA, Pacheco e Silva Á, Filho, Sesso RC, Esmeraldo RM, de Oliveira CM, Fernandes PF, et al. Epidemiologic, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of visceral leishmaniasis in renal transplant recipients: experience from thirty cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0852-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Da Silva A, Pacheco-Silva A, de Castro Cintra Sesso R, Esmeraldo RM, Costa de Oliveira CM, Fernandes PFCBC, et al. The risk factors for and effects of visceral leishmaniasis in graft and renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013;95(5):721–727. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827c16e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basset D, Faraut F, Marty P, Dereure J, Rosenthal E, Mary C, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in organ transplant recipients: 11 new cases and a review of the literature. Microbes Infect. 2005;7(13):1370–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira CMC, Oliveira MLMB, Andrade SCA, Girão ES, Ponte CN, Mota MU, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in renal transplant recipients: clinical aspects, diagnostic problems, and response to treatment. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(3):755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simão JC, Victória C, Fortaleza CMCB. Predictors of relapse of visceral leishmaniasis in inner São Paulo State, Brazil. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis [Internet] 2023. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/gho-ntd-leishmaniasis [cited 2024 July 14]

- 41.Trájer AJ, Grmasha RA. The potential effects of climate change on the climatic suitability patterns of the Western Asian vectors and parasites of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the mid- and late twenty-first century. Theor Appl Climatol. 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhaliwal A, Chauhan A, Aggarwal D, Davda P, David M, Amel-Kashipaz R, et al. Donor acquired visceral leishmaniasis following liver transplantation. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12(7):690–694. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horber FF, Lerut JP, Reichen J, Zimmermann A, Jaeger P, Malinverni R. Visceral leishmaniasis after orthotopic liver transplantation: impact of persistent splenomegaly. Transpl Int. 1993;6(1):55–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.1993.tb00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mannan SB, Elhadad H, Loc TTH, Sadik M, Mohamed MYF, Nam NH, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of asymptomatic leishmaniasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol Int. 2021;81:102229. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2020.102229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, Pearson R, Lopez-Velez R, Weina P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(1):24–45. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-84256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clemente WT, Rabello A, Faria LC, Peruhype-Magalhães V, Gomes LI, da Silva TAM, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic Leishmania spp. infection among liver transplant recipients and donors from an endemic area of Brazil. Am J Transplant. 2013;14(1):96–101. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibarra-Meneses AV, Corbeil A, Wagner V, Onwuchekwa C, Fernandez-Prada C. Identification of asymptomatic Leishmania infections: a scoping review. Parasit Vectors. 2022;15(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-05129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization . Screening donated blood for transfusion-transmissible infections: recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monge-Maillo B, López-Vélez R. Leishmaniasis in transplant patients: what do we know so far? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2024;37(5):342–348. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000001034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan American Health Organization . Guideline for the Treatment of Leishmaniasis in the Americas. 2nd. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cota GF, De Sousa MR, Demarqui FN, Rabello A. The diagnostic accuracy of serologic and molecular methods for detecting visceral leishmaniasis in HIV infected patients: meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(5):e1665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maritati M, Trentini A, Michel G, Hanau S, Guarino M, Giorgio RD, et al. Performance of five serological tests in the diagnosis of visceral and cryptic leishmaniasis: a comparative study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2023;17(5):693–699. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Botana L, Ibarra-Meneses AV, Sánchez C, Matía B, Martin JVS, Moreno J, et al. Leishmaniasis: a new method for confirming cure and detecting asymptomatic infection in patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment for autoimmune disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(8):e0009662–e0009672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carrillo E, Carrasco-Antón N, López-Medrano F, Salto E, Fernández L, Víctor J, et al. Cytokine release assays as tests for exposure to leishmania, and for confirming cure from leishmaniasis, in solid organ transplant recipients. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(10):e0004179–e0004189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Opota O, Balmpouzis Z, Berutto C, Kaiser-Guignard J, Greub G, Aubert JD, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in a lung transplant recipient: usefulness of highly sensitive real-time polymerase chain reaction for preemptive diagnosis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18(5):801–804. doi: 10.1111/tid.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jimenez-Marco T, Fisa R, Girona-Llobera E, Cancino-Faure B, Tomás-Pérez M, Berenguer D, et al. Transfusion-transmitted leishmaniasis: a practical review. Transfusion. 2016;56(S1, Suppl Suppl 1):S45–S51. doi: 10.1111/trf.13344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferreira‐Silva MM, Teixeira LAS, Tibúrcio MS, Pereira GA, Rodrigues V, Palis M, et al. Socio‐epidemiological characterisation of blood donors with asymptomatic Leishmania infantum infection from three Brazilian endemic regions and analysis of the transfusional transmission risk of visceral leishmaniasis. Transfus Med. 2018;28(6):433–439. doi: 10.1111/tme.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dey A, Singh S. Transfusion transmitted leishmaniasis: a case report and review of literature. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24(3):165–170. doi: 10.1016/S0255-0857(21)02344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henn GAL, Ramos AN, Júnior, Colares JKB, Mendes LP, Silveira JGC, Lima AAF, et al. Is Visceral Leishmaniasis the same in HIV-coinfected adults? Braz J Infect Dis. 2018;22(2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McFarlane E, Carter KC, McKenzie AN, Kaye PM, Brombacher F, Alexander J. Endogenous IL-13 plays a crucial role in liver granuloma maturation during leishmania donovani infection, independent of IL-4Rα-responsive macrophages and neutrophils. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(1):36–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Francesco Daher E, Silva GB, Jr, Barros E, d’Avila DO. In: Core concepts in parenchymal kidney disease. Fervenza F, Lin J, Sethi S, Singh A, editors. New York: Springer; 2014. Tropical Infectious Diseases and the Kidney. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dutra M, Martinelli R, Marcelino E, Rodrigues LE, Brito E, Rocha H. Renal involvement in visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1985;6(1):22–27. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(85)80034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bezerra G, Barros G, Daher EDF. Kidney involvement in leishmaniasis: a review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18(4):434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]