Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting is recommended in ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction. Immediate stenting may cause distal embolization, microvascular damage, and flow disturbances, leading to adverse outcomes. We report the 10-year clinical outcomes of deferred stenting versus conventional PCI in patients with ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

METHODS:

We conducted a 10-year follow-up study of the open-label, randomized DANAMI-3-DEFER trial (Third Danish Study of Optimal Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Deferred Stent Implantation Versus Conventional Treatment), conducted in 4 PCI centers in Denmark. Patients with ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction and acute chest pain <12 hours were randomized to deferred stenting >24 hours after the index procedure or conventional PCI with immediate stenting. In the deferred group, immediate stable Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow II to III was established, and intravenous administration of either a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist or bivalirudin for >4 hours after the index procedure was recommended. The primary outcome was a composite of hospitalization for heart failure or all-cause mortality. Key secondary outcomes included individual components of the primary outcome and target vessel revascularization.

RESULTS:

Of 1215 patients, 603 were randomized to deferred stenting and 612 to conventional PCI. After 10 years, deferred stenting did not significantly reduce the primary composite outcome (hazard ratio, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.67–1.02]; P=0.08). In the deferred group, 124 (24%) died versus 150 (25%) in the conventional PCI group (hazard ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.75–1.19]). Hospitalization for heart failure was lower in patients treated with deferred stenting compared with conventional PCI (odds ratio, 0.58 [95% CI, 0.39–0.88]). Target vessel revascularization was similar in both groups (odds ratio, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.81–1.79]).

CONCLUSIONS:

Deferred stenting did not reduce all-cause mortality or the composite primary outcome after 10 years but reduced hospitalization for heart failure compared with conventional PCI.

REGISTRATION:

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT01435408.

Keywords: heart failure, myocardial infarction, odds ratio, percutaneous coronary intervention, stents

WHAT IS KNOWN

A total of 4 randomized clinical trials have investigated the effect of deferred stenting in ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction, with the largest being the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial (Third Danish Study of Optimal Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Deferred Stent Implantation Versus Conventional Treatment).

DANAMI-3-DEFER was the only trial powered to detect clinical outcomes but showed neutral results regarding the effect of deferred stenting on the risk of death, heart failure, or reinfarction compared with standard immediate stent implantation in patients with ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

DANAMI-3-DEFER trial demonstrated that routine deferred stenting was associated with an increased rate of target vessel revascularization, leading to deferred stenting being discouraged in ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

This 10-year follow-up study of the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial showed that deferred stenting in patients with ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction did not reduce the composite of all-cause mortality or hospitalization for heart failure but was associated with a 42% significant reduction in hospitalization for heart failure compared with conventional immediate percutaneous coronary intervention.

This extended follow-up of DANAMI-3-DEFER trial showed that the increased incidence of target vessel revascularization in the deferred stenting group observed in the main trial appeared to diminish in the long-term.

In patients with ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) caused by plaque rupture and thrombus formation, timely percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), including stenting, is the recommended treatment to secure coronary blood flow and prevent re-occlusion.1,2 However, stenting may cause distal embolization with microvascular obstruction and subsequently reduced coronary blood flow.3–5 These complications are associated with larger infarcts and the potential development of heart failure, with a subsequent poor prognosis; in addition, no protective therapy has been shown to be effective.3,4,6–8 Notably, omitting stenting may, in selected patients with STEMI, be an alternative to stenting to avoid procedure-related complications.9

Myocardial protection to preserve the integrity of the left ventricle in relation to the restoration of blood flow has been investigated by strategies such as deferred stenting and distal protection.6,10–14 Thus, delaying stenting after securing a stable blood flow has been shown to decrease the incidence of flow disturbances and distal embolization.5,10 Nevertheless, this effect did not translate into reduced myocardial damage or improved short-term clinical outcomes.10–12,15 Moreover, leaving a culprit lesion without stenting may increase the risk of acute re-occlusion.

The DANAMI-3-DEFER trial (Third Danish Study of Optimal Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Deferred Stent Implantation Versus Conventional Treatment) investigated the effect of deferred stenting versus conventional PCI in 1215 patients with STEMI.12 During a median of 42 months, the primary outcome of all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, recurrent myocardial infarction, or unplanned target vessel revascularization did not differ between the 2 treatment groups.12 As a result, the routine use of deferred stenting is discouraged in the European guidelines.1,16

This 10-year follow-up study of DANAMI-3-DEFER examines the long-term outcomes of deferred stenting versus conventional PCI with immediate stenting. In addition, as 84 (14%) patients did not receive a stent, we also evaluate the long-term outcomes in patients with STEMI treated without stenting.

Methods

Data Availability Statement

Data will not be available to others.

Study Design

As part of the DANAMI-3 trial program, the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial was an open-label, randomized clinical trial conducted at 4 PCI centers in Denmark between March 2011 and February 2014. The DANAMI-3 trial program was performed at 4 heart centers in Denmark and consisted of 3 trials investigating ischemic postconditioning (DANAMI-3-POSTCON trial [Third Danish Study of Optimal Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Ischemic Postconditioning Versus Conventional Treatment]), deferred stenting (DANAMI-3-DEFER), and complete revascularization (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI trial [Third Danish Study of Optimal Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Complete Revascularization Versus Infarct-Related Artery Only]).17 The study protocol and primary results of all 3 trials have been published.12,17–19 The trial was approved by the ethics committee, conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki, and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01435408), with all patients providing informed consent.

Patients

The DANAMI-3 trial included patients with STEMI and <12 hours from symptom onset.17 Major exclusion criteria were cardiogenic shock, stent thrombosis, indication for acute coronary artery bypass surgery, or increased bleeding risk. In a secondary randomization, patients included in the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial with at least 1 nonculprit lesion with an angiographic diameter stenosis >50% were eligible to participate in DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI, testing complete revascularization versus culprit-only PCI.17 The complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria has been published previously.17

Randomization

All trial procedures have been described in depth previously.12,17 In brief, this was an open-label trial and patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either deferred stenting or conventional PCI. The PCI operators were not involved in the subsequent treatment or assessment of the patients.

Procedures

The study specific procedures have been described in depth previously.12,17 In brief, coronary blood flow was established and secured with a guidewire, thrombectomy, and a small-sized balloon. To avoid excess manipulation, only balloons substantially smaller than the reference size of the diameter of the vessel were used to secure blood flow.

To ensure a stable coronary flow without imminent re-occlusion, patients randomized to deferred stenting were observed for 10 minutes after retraction of the guidewire. Deferred stenting was performed between 24 and 48 hours after the primary PCI procedure. Patients allocated to conventional PCI were treated with immediate stenting. Drug-eluting stent implantation was preferred.

A pilot study investigating deferred stenting showed that, in patients with STEMI, ≤30% residual stenosis, and no visible thrombus, stenting could be safely omitted.13 Therefore, in patients randomized to deferred stenting in DANAMI-3-DEFER, stenting was omitted at the deferral procedure when the culprit lesion was deemed stable with ≤30% residual stenosis by visual assessment, no significant thrombus, and no visible dissection.9 All patients treated without stenting were offered an optional third angiography after 3 months. All other procedural interventions and additional treatments were left to the discretion of the PCI operator.

Outcomes

The concept of deferred stenting is to reduce distal embolization upon reflow and thus mitigate flow disturbances due to thrombus debris, to preserve the left ventricular function. Therefore, the primary outcome of this 10-year follow-up study was hospitalization for heart failure or all-cause mortality. Hospitalization for heart failure was defined as in the original trial.12

Secondary outcomes included the components of the primary outcome, cardiovascular mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, any revascularization, and the primary outcome of the original trial, which was a composite of all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, recurrent myocardial infarction, and target vessel revascularization.12 The definitions of outcomes are described in the Supplemental Material.

Patients were initially followed for a period of up to 56 months and treated according to contemporary guidelines, including concomitant medication and rehabilitation programs. During the initial follow-up period, an independent data safety monitoring board evaluated the trial for safety, and an independent clinical events committee adjudicated events.12 From 2015, events were retrieved using hospital records until January 2024. Data were obtained and evaluated by 2 reviewers. In case of discordance, a third reviewer secured consensus. The reviewers were blinded to treatment allocation.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were analyzed strictly by intention-to-treat. The primary outcome and all-cause mortality were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model, calculating a hazard ratio between randomization groups with a 95% CI. Cumulative incidences between groups were illustrated for primary and secondary outcomes. In addition, secondary outcomes were analyzed with all-cause mortality as a competing risk, and the effect of treatment was described with a cumulative incidence regression logistic-link model, which was reported as odds ratios with 95% CI.20 Models were tested for proportionality or constant effects over time and were found valid. The Gray test was also reported as a test between groups in the competing risk analysis, and Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard ratios were subsequently calculated for secondary outcomes that did not include all-cause mortality.21 As patients with multivessel disease could be further randomized in the DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI trial to PCI of the infarct-related artery only or complete revascularization, interaction with randomization allocation in the DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI trial was tested for the primary outcome.

The primary outcome was assessed in subgroups illustrated in a forest plot. Subgroups included age ≥65 years, sex, infarct location, symptom-to-intervention time, pre-PCI Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow, diabetes, use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, and Killip class at admission were assessed. Interaction was tested in all subgroups.

In the deferred treatment group, 84 patients were treated with no stenting due to ≤30% residual stenosis evaluated visually by angiography, no significant thrombus, and no visible dissection.9 As a supplementary analysis, these patients (no stenting) were compared with patients treated with immediate stenting in the conventional PCI treatment group (immediate stenting). Cumulative incidences and effect measures were analyzed as for the primary and secondary outcomes. Furthermore, adjusted analyses for the outcomes were conducted, adjusting for variables that are known to influence the prognosis after STEMI and are of high clinical importance1: age, sex, diabetes, and anterior infarction. A baseline table including patients randomized to deferred stenting, stratified by stenting status, was conducted.

P values were 2-sided and considered statistically significant if <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed between October and December 2024 in the statistical software R, version 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

In the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial, 1215 patients were randomized, of whom 603 were assigned to deferred stenting and 612 to conventional PCI.12 Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between groups (Table S1).12 The median follow-up time among survivors in this report was 10 years (25–75 percentiles: 10–10 years), and there was no loss to follow-up.

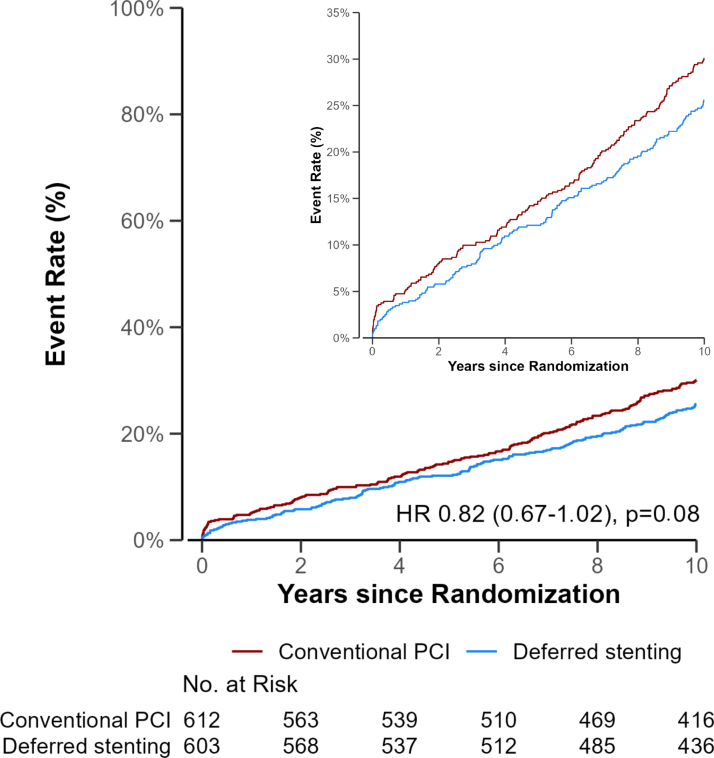

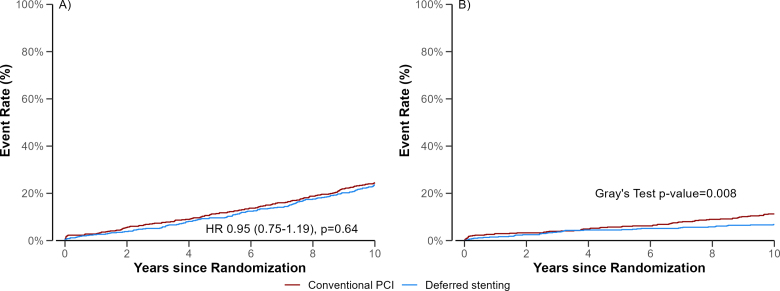

The 10-year cumulative incidence curves of all-cause mortality or hospitalization for heart failure was 26% (95% CI, 22–29%) in the deferred stenting group and 30% (95% CI, 26–34%) in the conventional PCI group and (hazard ratio, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.67–1.02]; P=0.08; Table 1; Figure 1). Of the patients treated with deferred stenting, 142 (24%) died versus 150 (25%) in the conventional group (hazard ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.75–1.19]; Table 1; Figure 2). The cumulative incidence of hospitalization for heart failure was 7% in the deferred stenting group and 11% in the conventional PCI group, with an odds ratio of 0.58 (95% CI, 0.39–0.88; Table 1; Figure 2). The cumulative incidence of the secondary outcomes is presented in Table 1. Cardiovascular mortality and target vessel revascularization did not differ between groups (odds ratio, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.67–1.40] and odds ratio, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.81–1.79]). Furthermore, the composite end point of all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, recurrent myocardial infarction, and target vessel revascularization was similar (odds ratio, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.78–1.12]). The results remained similar in the Fine and Gray models (Table S2).

Table 1.

Outcomes

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality or hospitalization for heart failure. Event rates of the primary outcome of all-cause mortality or hospitalization for heart failure. Follow-up was 10 years after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). HR indicates hazard ratio.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure. Event rates of (A) all-cause mortality and (B) hospitalization for heart failure. Follow-up was 10 years after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). HR indicates hazard ratio.

There was no interaction between randomization allocation in the DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI trial and the primary outcome (P=0.67; Table S3).

Subgroup Analysis

A significant interaction was observed between infarct location and randomization allocation for the primary outcome (P=0.012). In patients with anterior infarction, deferred stenting was associated with a significantly lower risk of the primary outcome (hazard ratio, 0.60 [95% CI, 0.43–0.84]; Figure 3). A similar result was found for patients ≤65 years of age. In the remaining subgroups, no interaction was found (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis. The figure shows a forest plot of the primary outcome in subgroups. Hazard ratios with corresponding 95% CIs are shown and a P value for interaction. The widths of the CIs were not adjusted for multiplicity and should not be interpreted in terms of hypothesis testing. PCI indicates percutaneous coronary intervention; and TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

No Stenting

Among the 603 patients randomized to deferred stenting, 84 (14%) patients did not receive a stent during either the initial or deferred procedure. Of patients randomized to deferred stenting, patients treated without stenting had less diabetes, fewer had multivessel disease, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIb inhibitor was more frequently used compared with patients treated with deferred stenting (Table S4). Comparing the patients that was stented immediately (conventional PCI) with the patients in whom stenting was omitted, there was no difference in clinical outcomes in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses (Table 2). The cumulative incidence of target vessel revascularization was 8% (95% CI, 6–11%) in the immediate stenting group and 5% (95% CI, 2–11%) in the no-stenting group (adjusted odds ratio, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.20–1.72]).

Table 2.

Outcomes in Patients Treated With No Stenting Versus Immediate PCI

Discussion

This 10-year follow-up of the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial demonstrates that deferred stenting in patients with STEMI treated with primary PCI did not significantly reduce the composite end point of all-cause mortality or hospitalization for heart failure, though a strong tendency was observed. While deferred stenting did not reduce all-cause mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction, or cardiovascular mortality, it was associated with a 42% reduction in hospitalization for heart failure compared with immediate stenting. Moreover, in patients with anterior infarction, deferred stenting seemed to lower the combined risk of mortality or heart failure hospitalization by 40%. The original primary outcome of all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, recurrent myocardial infarction, or target vessel revascularization was not different between groups at 10 years. However, unlike earlier findings, the extended follow-up showed that the increased incidence of target vessel revascularization in the deferred stenting group observed in the DANAMI-3-DEFER main trial appeared to diminish in the long-term. Finally, patients randomized to deferred stenting but treated without stenting had in general a trend to a low event rate comparable to patients treated with immediate stenting. However, these groups are not directly comparable, and omitting stenting may only apply to patients with STEMI at lower clinical risk. As this is a post hoc analysis, the findings may be considered hypothesis-generating.

The procedure of deferred stenting relies on the assumption that less manipulation in a fresh plaque rupture with thrombus would reduce peripheral embolization and flow disturbances during primary PCI, leading to attenuation of myocardial damage and, in turn, the development of heart failure.13 Randomized trials have shown that deferred stenting in patients with STEMI significantly reduced the occurrence of no reflow and distal embolization,5,10 but despite these promising results, our original DANAMI-3-DEFER trial failed to show a prognostic benefit of deferred stenting.12 Consistently, a substudy of the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial found no effect of deferred stenting on microvascular obstruction, infarct size, or myocardial salvage on cardiac magnetic resonance.15 Despite no difference in early surrogate markers, we find a difference between groups on long-term hospitalization for heart failure. These ambiguous findings could be explained by the number of patients who underwent both cardiac magnetic resonance scans (n=413, 34%). The substudy may therefore have introduced selection bias by excluding high-risk patients, as they were less likely to undergo the scan. However, as the present study has complete follow-up, this limitation does not apply. Moreover, the cardiac magnetic resonance findings of the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial contrast with other studies that showed significantly higher myocardial salvage and less microvascular obstruction in patients treated with deferred stenting compared with conventional immediate PCI.10,14 The DANAMI-3-DEFER trial showed a small but significantly higher left ventricular ejection fraction at 18 months by echocardiography in patients treated with deferred stenting, a finding that might have contributed to the lower incidence of hospitalization for heart failure in the present report. Still, only 64% of the patients underwent the 18-month echocardiography, and the clinical importance of this finding is uncertain and has not so far resulted in a reduction in mortality. This is in line with recent large-scale heart failure trials showing a reduction in admissions for heart failure that have not translated into a reduction in all-cause mortality.22,23

Despite no significant effect of deferred stenting on the composite end point of all-cause mortality or hospitalization for heart failure in the overall study cohort, there was a significant interaction with infarct location, suggesting substantial benefit in patients with anterior infarction. Although post hoc in nature and therefore only hypothesis-generating, this finding may indicate an effect on the composite end point in patients with a sufficiently large area at risk and a higher risk of distal embolization and no reflow.5,15 Also, patients with anterior infarction are more prone to develop heart failure due to a larger area at risk and subsequent larger final infarct size.24,25

In the original DANAMI-3-DEFER trial, the incidence of target vessel revascularization was higher in the deferred stenting group compared with conventional PCI.12 A considerable number of these end points were represented by early re-occlusions, most of which occurred during the index hospitalization. In the 603 patients allocated to deferred stenting, the reopened infarct-related lesion was deemed stable enough to waive immediate stenting in 78 patients, and that the re-occlusion rate declined during the trial, indicated a certain learning curve in the ability to make this judgment correctly. Importantly, deferred stenting seemed safe in the long-term, as the increased risk of target vessel revascularization in this group diminished over time.12 In the DEFER-STEMI trial (Deferred Stent Trial in STEMI), an intention-to-stent interval in the deferred treatment arm of 4 to 16 hours was applied, with patients receiving glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and low molecular weight heparin.10 This resulted in only 2 cases of re-intervention of the culprit lesion.10 Hence, a shorter interval between procedures combined with a more aggressive antithrombotic regimen may reduce early target vessel revascularization while preserving the potential benefits of deferred stenting.

A pilot study of deferred stenting showed that in 40% of patients with STEMI, it was unnecessary to implant a stent at the deferred procedure.13 Hence, omitting stenting may be favorable in some patients, as the inherent risk of in-stent restenosis and stent thrombosis is avoided.13,26 These benefits may, however, be outweighed by the risk of re-occlusion and recurrent myocardial infarction. A post hoc analysis of the DANAMI-3-DEFER trial showed that patients randomized to deferred stenting and treated without stenting at all due to ≤30% residual stenosis with no significant thrombus or visible dissection, had comparable event rates to patients treated with immediate stenting.9 As presented in the present study, these findings persisted in the long-term. Consequently, the strategy of deferred stenting may lead to safely avoiding stenting in selected cases, although this has not been tested in a larger randomized setting. Finally, these findings are hypothesis-generating and warrant future randomized studies evaluating a no-stenting strategy in selected patients with STEMI.

The optimal reperfusion technique in STEMI remains an area of investigation. A recent study in patients with STEMI found that pressure-controlled reperfusion by stepwise reopening of the occluded artery in combination with delayed stenting (30 minutes) led to better microvascular integrity and smaller infarct size.27 However, despite promising findings, the study is inherently limited by its small sample size. Finally, we are currently awaiting the results of the DANAMI-4 trial investigating both the effect of ischemic in patients with STEMI. Thus, alternative reperfusion strategies beyond conventional PCI in STEMI continue to evolve.

The present study shares limitations with the original trial.12 The trial was open-label, and we cannot rule out that the patients and treating physicians could have been biased by the treatment allocation. Moreover, this study was post hoc in nature, and the findings should only be interpreted as such.

In conclusion, this 10-year follow-up study of DANAMI-3-DEFER shows that deferred stenting in patients with STEMI did not significantly reduce the primary end point of all-cause mortality or hospitalization for heart failure but was associated with a lower incidence of hospitalization for heart failure compared with conventional immediate PCI.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Sources of Funding

DANAMI-3-DEFER trial (Third Danish Study of Optimal Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Deferred Stent Implantation Versus Conventional Treatment) was funded by the Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation and the Danish Council for Strategic Research (EDITORS, grant 09-066994). The funders had no role in this follow-up study.

Disclosures

Dr Køber: speaker’s honorarium from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk. Dr Lønborg: an advisory board fee, an unrestricted grant, and speakers fee from Boston Scientific and speakers fee from Abbott, unrelated to this topic. Dr Engstrøm: advisory board fee from Abbott, Novo Nordisk and speakers fee from Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Boston Scientific. Dr Clemmensen: previous or current involvement in research contracts, consulting, speakers bureau or received research and educational grants from: Abbott, Abiomed, AliveCor, Inc, AstraZeneca, Aventis, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, CeleCor, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli-Lilly, Evolva, Fibrex, Idorsia, IQVIA, Janssen, Merck, Myogen, Medtronic, Mitsubishi Pharma, The Medicines Company, Nycomed, Organon, Pfizer, Pharmacia, Philips, Regado, Sanofi, Searle, Servier, ViFor Pharma. VP, consultant fees, honoraria and educational grant from Abiomed J&JVP. Dr Jensen: unrestricted research grants to her institution from Biotronik, Biosensors and OrbusNeich. The other authors report no conflicts.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Methods

Tables S1–S4

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- DANAMI-3-

- Third Danish Study of Optimal DEFER Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Deferred Stent Implantation Versus Conventional Treatment

- DANAMI-3-

- Third Danish Study of Optimal POSTCON Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Ischemic Postconditioning Versus Conventional Treatment

- DANAMI-3-

- Third Danish Study of Optimal PRIMULTI Acute Treatment of Patients With STEMI – Complete Revascularization Versus Infarct-Related Artery Only

- DEFER-STEMI

- Deferred Stent Trial in STEMI

- PCI

- percutaneous coronary intervention

- STEMI

- ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction

Presented in part at EuroPCR 2025 in Paris, France, May 20–23, 2025.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.125.015369.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 494.

Contributor Information

Thomas Engstrøm, Email: thomas.engstroem@regionh.dk.

Henning Kelbæk, Email: h.kelbaek@dadlnet.dk.

Rasmus Paulin Beske, Email: rasmus.paulin.beske.02@regionh.dk.

Utsho Islam, Email: utsho.islam.02@regionh.dk.

Lene Holmvang, Email: Lene.Holmvang@regionh.dk.

Frants Pedersen, Email: Frants.Pedersen@regionh.dk.

Evald Høj Christiansen, Email: evald.christiansen@clin.au.dk.

Hans-Henrik Tilsted, Email: hans-henrik.tilsted@regionh.dk.

Charlotte Glinge, Email: cglinge@gmail.com.

Reza Jabbari, Email: rezajabbari77@gmail.com.

Ashkan Eftekhari, Email: ashkan81@gmail.com.

Bent Raungaard, Email: b.raungaard@rn.dk.

Peter Clemmensen, Email: p.clemmensen@uke.de.

Hans Erik Bøtker, Email: heb@dadlnet.dk.

Lars Køber, Email: Lars.koeber.01@regionh.dk.

References

- 1.Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, Claeys MJ, Dan G-A, Dweck MR, Galbraith M, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720–3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, Bittl JA, Cohen MG, DiMaio JM, Don CW, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e18–e114. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rezkalla SH, Stankowski RV, Hanna J, Kloner RA. Management of no-reflow phenomenon in the catheterization laboratory. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fokkema ML, Vlaar PJ, Svilaas T, Vogelzang M, Amo D, Diercks GFH, Suurmeijer AJH, Zijlstra F. Incidence and clinical consequences of distal embolization on the coronary angiogram after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:908–915. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nepper-Christensen L, Kelbæk H, Ahtarovski KA, Høfsten DE, Holmvang L, Pedersen F, Tilsted H-H, Aarøe J, Jensen SE, Raungaard B, et al. Angiographic outcome in patients treated with deferred stenting after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction-results from DANAMI-3-DEFER. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2022;11:742–748. doi: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuac098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelbaek H, Terkelsen CJ, Helqvist S, Lassen JF, Clemmensen P, Kløvgaard L, Kaltoft A, Engstrøm T, Bøtker HE, Saunamäki K, et al. Randomized comparison of distal protection versus conventional treatment in primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the drug elution and distal protection in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (DEDICATION) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:899–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaltoft A, Bøttcher M, Nielsen SS, Hansen H-HT, Terkelsen C, Maeng M, Kristensen J, Thuesen L, Krusell LR, Kristensen SD, et al. Routine thrombectomy in percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2006;114:40–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fröbert O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, Omerovic E, Gudnason T, Maeng M, Aasa M, Angerås O, Calais F, Danielewicz M, et al. ; TASTE Trial. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1587–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madsen JM, Kelbæk H, Nepper-Christensen L, Jacobsen MR, Ahtarovski KA, Høfsten DE, Holmvang L, Pedersen F, Tilsted H-H, Aarøe J, et al. Clinical outcomes of no stenting in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing deferred primary percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention. 2022;18:482–491. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-00950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrick D, Oldroyd KG, McEntegart M, Haig C, Petrie MC, Eteiba H, Hood S, Owens C, Watkins S, Layland J, et al. A randomized trial of deferred stenting versus immediate stenting to prevent no- or slow-reflow in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (DEFER-STEMI). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2088–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belle L, Motreff P, Mangin L, Rangé G, Marcaggi X, Marie A, Ferrier N, Dubreuil O, Zemour G, Souteyrand G, et al. ; MIMI Investigators. Comparison of immediate with delayed stenting using the minimalist immediate mechanical intervention approach in acute ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: the MIMI study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelbæk H, Høfsten DE, Køber L, Helqvist S, Kløvgaard L, Holmvang L, Jørgensen E, Pedersen F, Saunamäki K, De Backer O, et al. Deferred versus conventional stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (DANAMI 3-DEFER): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387:2199–2206. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30072-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelbæk H, Engstrøm T, Ahtarovski KA, Lønborg J, Vejlstrup N, Pedersen F, Holmvang L, Helqvist S, Saunamäki K, Jørgensen E, et al. Deferred stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a pilot study. EuroIntervention. 2013;8:1126–1133. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I10A175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JS, Lee HJ, Woong YC, Kim YM, Hong SJ, Park JH, Choi RK, Choi YJ, Park JS, Kim TH, et al. INNOVATION study (Impact of Immediate Stent Implantation Versus Deferred Stent Implantation on Infarct Size and Microvascular Perfusion in Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction). Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e004101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lønborg J, Engstrøm T, Ahtarovski KA, Nepper-Christensen L, Helqvist S, Vejlstrup N, Kyhl K, Schoos MM, Ghotbi A, Göransson C, et al. ; DANAMI-3 Investigators. Myocardial damage in patients with deferred stenting after STEMI: a DANAMI-3-DEFER substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2794–2804. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Høfsten DE, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, Kløvgaard L, Holmvang L, Clemmensen P, Torp-Pedersen C, Tilsted H-H, Bøtker HE, Jensen LO, et al. ; DANAMI 3 Investigators. The third Danish study of optimal acute treatment of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: ischemic postconditioning or deferred stent implantation versus conventional primary angioplasty and complete revascularization versus treatment of culprit lesion only: rationale and design of the DANAMI 3 trial program. Am Heart J. 2015;169:613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engstrøm T, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, Høfsten DE, Kløvgaard L, Clemmensen P, Holmvang L, Jørgensen E, Pedersen F, Saunamaki K, et al. ; Third Danish Study of Optimal Acute Treatment of Patients With ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction–Ischemic Postconditioning (DANAMI-3–iPOST) Investigators. Effect of ischemic postconditioning during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:490–497. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engstrøm T, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, Høfsten DE, Kløvgaard L, Holmvang L, Jørgensen E, Pedersen F, Saunamäki K, Clemmensen P, et al. ; DANAMI-3—PRIMULTI Investigators. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3—PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386:665–671. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60648-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson F, Li J, Scheike T, Zhang M-J. The proportional odds cumulative incidence model for competing risks. Biometrics. 2015;71:687–695. doi: 10.1111/biom.12330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, et al. ; EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1413–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Vaduganathan M, Claggett B, Jhund PS, Desai AS, Henderson AD, Lam CSP, Pitt B, Senni M, et al. ; FINEARTS-HF Committees and Investigators. Finerenone in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1475–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2407107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordlund D, Heiberg E, Carlsson M, Fründ ET, Hoffmann P, Koul S, Atar D, Aletras AH, Erlinge D, Engblom H, et al. Extent of myocardium at risk for left anterior descending artery, right coronary artery, and left circumflex artery occlusion depicted by contrast-enhanced steady state free precession and T2-weighted short tau inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e004376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.004376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madsen JM, Engstrøm T, Obling LER, Zhou Y, Nepper-Christensen L, Beske RP, Vejlstrup NG, Bang LE, Hassager C, Folke F, et al. Prehospital pulse-dose glucocorticoid in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the PULSE-MI randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9:882–891. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2024.2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torrado J, Buckley L, Durán A, Trujillo P, Toldo S, Valle Raleigh J, Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai G, Guzmán LA. Restenosis, stent thrombosis, and bleeding complications: navigating between scylla and charybdis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1676–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sezer M, Escaned J, Broyd CJ, Umman B, Bugra Z, Ozcan I, Sonsoz MR, Ozcan A, Atici A, Aslanger E, et al. Gradual versus abrupt reperfusion during primary percutaneous coronary interventions in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (GUARD). J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e024172. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will not be available to others.