Abstract

Background:

Studies have demonstrated that Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) plays a crucial role in neuropathic pain. However, there have been no relevant reports regarding the role of TLR3 in migraine chronification. This study aims to investigate the molecular mechanisms of TLR3 in the central sensitization of chronic migraine (CM).

Methods:

C57BL/6 male mice were used as models for chronic migraine (CM) disease, receiving an intraperitoneal injection of nitroglycerin (NTG) every other day. Calibrated von Frey filaments were employed to measure the pain threshold in the hind paw sole and periorbital region, enabling the assessment of mechanical allodynia. Western blot was employed to detect the expression changes of TLR3, TRAF6, TAK1, c-Fos, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. Immunofluorescence was used to detect the cellular localization of TLR3 and the expression changes of central sensitization-related indicators, such as c-Fos and CGRP. In addition, we investigated the effects of TLR3 inhibitor (CU CPT4a), MEK inhibitor(PD98059), TRAF6 inhibitor(C25-140), and TAK1 inhibitor (Takinib) on chronic migraine-like behavior, and activation of the ERK pathway in the Trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC).

Results:

Recurrent injections of NTG resulted in a significant increase in the expression of TLR3, TRAF6, TAK1, CGRP, and c-Fos proteins, as well as the activation of the ERK signaling pathway. Concurrent inhibition of TLR3 function, TRAF6, TAK1, and the ERK pathway counteracted these changes and alleviated hyperalgesia in CM mice.

Conclusions:

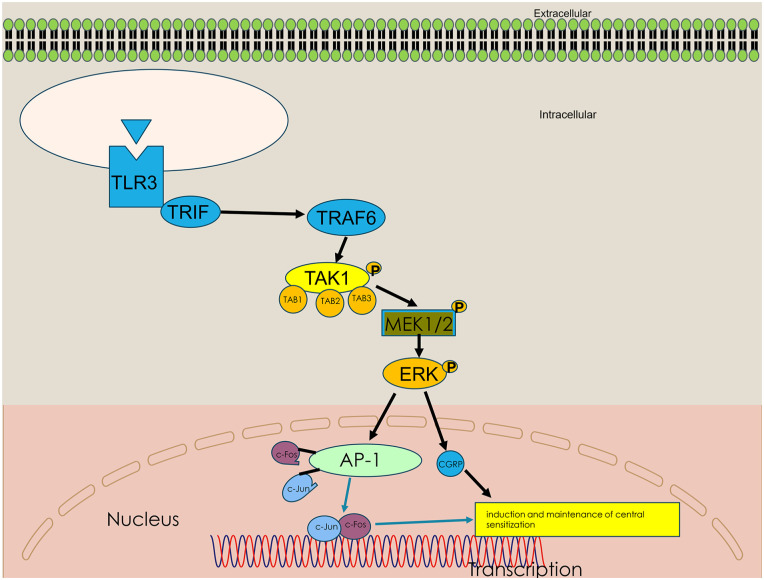

Our findings suggest that TLR3 may play a role in central sensitization in CM mice by TRAF6-TAK1 axis modulating the ERK signaling pathway.

Keywords: TLR3, neuron, chronic migraine, ERK, central sensitization

Introduction

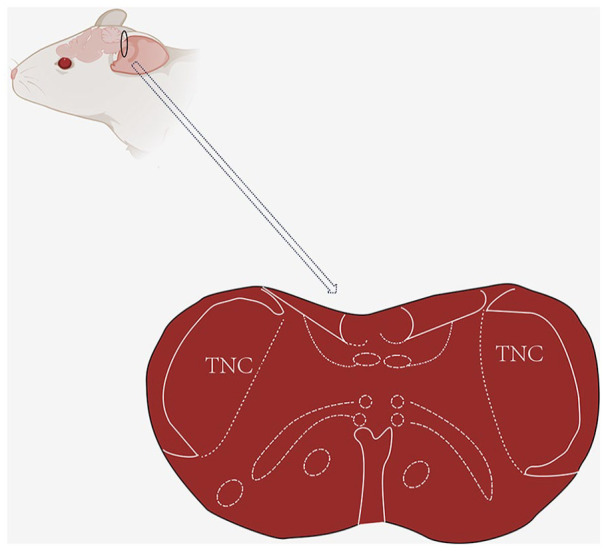

Chronic migraine (CM) is one of the common neurological disorders, which primarily transforms from episodic migraines. 1 CM is one of the common neurological disorders characterized by unilateral or bilateral pulsatile headaches, attacking for more than 15 days per month. 2 CM affects 1%–2% of the general population due to high disability rates, inadequate diagnosis, and lack of effective treatment. With cornification, the modifications of structural, physiological, and biochemical in the brain lead to an increase in the frequency of headaches and a poor reaction to therapy.3,4 The specific mechanism of chronic migraine is still unclear. One of the primary theories is the central sensitization hypothesis, which proposes an increase in the excitability of central neurons in the caudal trigeminal nucleus (Figure 1). 5

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of mouse TNC site.

TNC: Trigeminal nucleus caudalis.

The black circle represents the TNC site of the mouse, and below is an enlarged cross-sectional view of TNC.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are the primary regulatory elements of innate immune function and participate in the activation of inflammatory responses in the brain. 6 Previous studies have shown that TLR3 is a prominent TLR in neurons that is highly expressed in response to inflammatory stimuli such as viral infections.7,8 Research has shown that cortical spreading depression (CSD) leads to increased TLR3 expression in astrocytes. 9 Although there are also studies indicating that TLR3 has anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective in CSD-induced neuroinflammation, 10 recent studies have shown that TLR3 is activated in chronic pain and leads to cognitive impairment after chronic pain by producing inflammatory factors. 11 However, there are currently no reports on the association between TLR3 and chronic migraine.

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), a ubiquitin ligase, is crucial for the production of inflammatory cytokines in the TLR3-mediated signaling pathway. When activated, it produces short protein chains in itself and other proteins. After ubiquitination, TRAF6 will recruit TAK1, causing its phosphorylation, thereby leading to the activation of TAK1. TAK1, transforming growth factor kinase 1, is a member of the Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K) family and can activate the classic phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase ERK signaling pathways. 12 TAK1 and TRAF6 are closely related to chronic pain in mice.13,14

The development of CM is related to the central sensitization process occurring in the TNC.15,16 The ERK signaling pathway is closely associated with central sensitization and performs a significant role in the development and maintenance of chronic pain states, including migraine.17–19 Phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) and c-Fos have always been used as biomarkers for neuronal activation and central sensitization after tissue injury by noxious stimulation. 20 What’s more, the induction of c-Fos which forms the AP1 complex through the ERK pathway is necessary.21–23

Based on these data, we hypothesized that TLR3 mediates central sensitization in CM mice by TRAF6-TAK1 axis modulating the ERK signaling pathway. We validated these findings by using antagonists of these proteins establishing the unique role of TLR3 in CM mice.

Methods

Animals

The research objects of this experiment were male C57BL/6 mice, weighing 20–25 g and aged 8–12 weeks old. Mice were supplied by the Experimental Animal Center of the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Lanzhou, Gansu, China). Under standard laboratory conditions, the mice are required to maintain a 12-h light/dark cycle and be provided with sufficient food and water. The experiments were conducted between 9:00 and 15:00. All animals must be adapted to the environment for 1 week before the start of the experiment and be randomly assigned to the experimental group. Animal experiments should follow the ethical guidelines of the International Association for Pain Research to study experimental pain in conscious animals. 24 During the administration period, the animals were weighed daily, and no adverse reactions were observed.

Establishment of a CM model

We followed the experimental method described by Pradhan et al. 25 and conducted the following experimental procedure: First of all, we established a CM model by repeated intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) of NTG. NTG was purchased from Lanzhou University Second Hospital (Chinese Drug Approval Number: H11020289; 5.0 mg/ml). We did not observe a significant difference in mechanical threshold between animals injected with 0.9% saline and NTG solvents (6% propylene glycol, 6% ethanol, and 0.9% saline). NTG was diluted at 1 mg/ml before the experiment began, and the vehicle control was 0.9% saline. The injection dose for all mice was administered at a volume of 10 mg/kg. Animals received NTG or vehicle every other day within 9 days, a total of five times (in chronic treatment experiments, five times were performed on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9; Figure 2(a)).

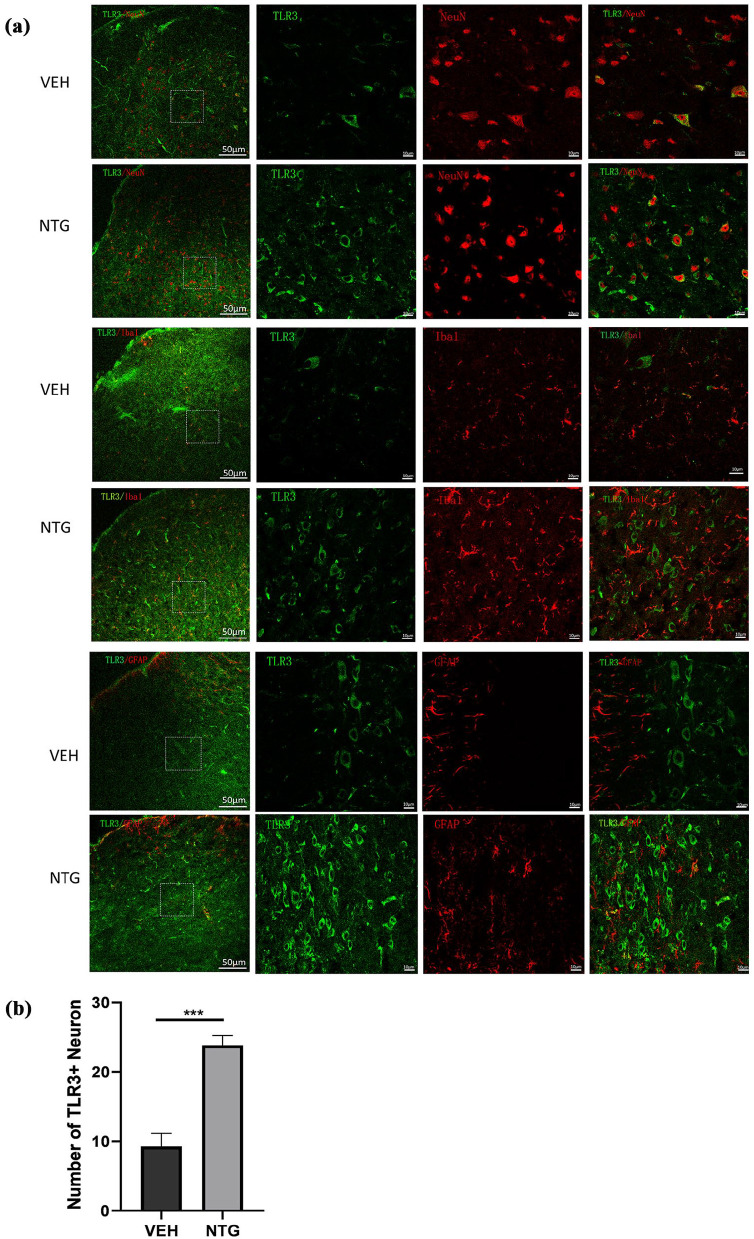

Figure 2.

After NTG administration, the expression of TLR3 in TNC neurons increased. (a) Double immunofluorescence labeling of TLR3, Iba-1, GFAP, and NeuN in the TNC after NTG administration. The first image on the far left shows a higher magnification image. Scale bar: 50 μm. The images on the right show an image with a higher magnification. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of the number of TLR3 with NeuN in the TNC within a 212 × 212 μm² visual field of each section per mouse after NTG injection.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 4 per group, three sections from each mouse.

***p < 0.001 compared to the vehicle group.

Drug administration

To understand the exact role of TLR3 in CM, Before NTG injection, animals were given an intraperitoneal injection of the selective TLR3 antagonist CUCPT4a (5 mg/kg; HY-108473) every other day, with a total of five times within 9 days. To explore the potential involvement of the ERK pathway in CM, animals were also intraperitoneally injected with PD98059 (10 mg/kg; MCE, USA), an antagonist targeting the ERK pathway. To investigate the key adaptor proteins between TLR3 and ERK signaling pathways, TRAF6 antagonist C25-140 (10 mg/kg; HY-120934) and TAK1 antagonist takinib (50 mg/kg; HY-10390) were injected intraperitoneally into mice, respectively. Dissolve CUCPT4a, C25-140, and takinib in 5% DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO, used as a carrier), 40% PEG300, 50% saline, and 5% Tween 80, respectively. PD98059 was dissolved in 50% PEG300 and 50% saline. We used equal volumes of solvents corresponding to each drug as vehicle controls. After the behavioral testing, these solvents were utilized in subsequent immunofluorescence and Western blot experiments. The drug dosage and administration method were determined based on literature and preliminary experiments.26,27

Behavioral assessment

The important pathogenesis of migraine is central sensitization. In clinical practice, central sensitization manifests as skin allodynia and enlargement of pain areas, including both craniofacial and non-craniofacial regions. 28 Therefore, in animal models, we measured the thresholds for periorbital and posterior claw retraction in response to mechanical stimulation, as previously studied. 29 All behavioral tests should be conducted in a quiet environment between 9:00 am and 4:00 pm. Before the experiment starts, we need to train the mice for 3 days. All behavioral tests, including mechanical retraction thresholds (hind paw and periorbital), should be conducted in the same group of animals and conducted by the same researcher, who remains unaware of the specific experimental animal groups and the behavioral data analysis.

Mechanical pain test

The mechanical retraction threshold was measured by a mechanical pain test. Because headache is an important characteristic of migraine, abnormal skin pain is a manifestation of hypersensitivity reactions. 30 Therefore, we represent the peripheral characteristics of central sensitization in CM animal models by measuring head-specific (periorbital) abnormal pain and hind paw hyperalgesia. The withdrawal thresholds of the hind paw and periorbital were every other day before and 2 h after NTG injection (Figure 2(a)). The withdrawal threshold for mechanical stimulation was measured by von Frey filaments with the up-down method, as described in previous research.31,32

In short, a series of von Frey filaments (ranging from 0.008 to 2 g) are applied to the hind paw or periorbital region with an initial stimulation intensity of 0.16 g. If the mouse does not respond to filament stimulation, the filament strength increases; Otherwise, the strength of the filaments decreases until a positive reaction occurs. The stimulation of each filament should last for 3–5 s during testing, with an interval of 3 min. The threshold was recorded as the lowest force triggering a positive response. Positive reactions were represented as X, negative reactions were represented as O, and after the breakthrough point (XO/OX), four additional stimuli were applied, resulting in a pattern of negative and positive reactions, such as OOOXOXO, XXXOXOXO, or OOXOXOX.33,34

In the hind paw test, we placed the mice separately in a suspended acrylic chamber (100 mm × 70 mm × 120 mm) covered with a metal mesh floor. Mice were exposed to a new environment for at least 30 min. We applied von Frey filaments in the central area perpendicular to the surface of the hind paw, avoiding the fat pad. The positive reaction was characterized by rapid withdrawal, shaking, lifting, and licking of the test paw. For periorbital assessment, the mice were placed separately in a 4-oz paper cup with only their heads exposed. The head and front paws could move freely, but they couldn’t rotate their bodies in the cup. The periorbital region includes the area from the tail of the eye to approximately the midline. The positive reaction observed in mice was a rapid retraction of the head following vocalization and stimulation, or when they scratched their face with the same side front paw.

Western blotting

To detect the expression level of TLR3 protein, TNC was collected within 24 h of different NTG injection times. Mice were euthanized under 3% pentobarbital anesthesia sodium. We immediately collected TNC sites from the mouse brain, rinsed them in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and stored them at −80ºC. We placed the tissue (TNC) in a cold RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing benzylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and shook well. The specific grinding procedure is as follows: 4°C; Frequency, 60 Hz; Time, 60 s (10 s per grinding, 10 s intervals, three cycles). Afterward, we placed the thorough ground tissue at 4°C for 1 h to ensure sufficient tissue lysis and then centrifuged the tissue at 12,000 g for 15 min at a 4°C centrifuge. We used the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) to determine protein content. The equivalent amounts of protein samples (150 µg) were separated by 10% SDS dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Hy Clone, Shanghai, USA) and transferred to the NC membrane. Then, we placed the NC membrane in a TBST solution containing 5% skim milk powder and sealed it at room temperature for 1 h. Next step, we incubated it overnight with the following antibodies at 4°C: mouse anti-TLR3 (1:500, ab13915, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), mouse anti-β-actin (1:500, Santa, China), mouse anti-c-Fos (1:1000, ab208942, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti-CGRP (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), mouse anti-TRAF6(1:1,000, SC-7221, China.), rabbit anti-P-TAK1(1:1000, Ser439, MCE, China), mouse anti-TAK1(1:1000, YA663, MCE, China), rabbit anti-P-ERK1/2 (1:1000, 9101S, CST, USA), rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (1:1000, CST, 4695 T, USA), rabbit anti-P-MEK1/2 (1:1000, Ser298, MCE, China), rabbit anti-MEK1/2 (1:1000, ab32576, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). To ensure consistent results, at least five independent experiments should be conducted for each protein blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

For TLR3, c-Fos, and CGRP detection, tissues were collected within 24 h. We anesthetized the mice, perfused them with physiological saline throughout the body, and then fixed them with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After fixation, we removed the entire brain and cervical spinal cord (C1–C2) and fixed them overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C. We extracted medullary segments containing TNC and transferred them sequentially to 20% and 30% sucrose/PBS solutions for dehydration treatment until they sank. After sucrose gradient dehydration, we embedded the tissue with OCT (optimal cutting temperature compound, OCT) tissue embedding agent and froze it in a −80°C freezer. We sliced the embedded tissue (15 μm thickness) on a low-temperature constant temperature slicer (CM 1950; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).35,36 To prevent the tissue on the slices from falling off, we first placed them in a constant temperature incubator at 37°C for 30 min. 37 Afterward, We blocked the slices in 5% normal goat/donkey serum containing 0.3% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated overnight with the following primary antibodies at 4°C: mouse anti-TLR3 (1:400, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti-NeuN (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and goat anti-Iba1 (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti-GFAP (1:50, WL0836, Wanleibio, China), rabbit anti-CGRP (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and mouse anti-c-Fos (1:400, ab208942, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). After washing in PBS for 15 min (5 min each time, 3 times), we placed the slices with fluorescent conjugated second antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594, 1:500, 1:400, Jackson Immunological Research Inc., USA) at room temperature for 2 h (avoiding light treatment). After washing in PBS three times for 5 min each time, the cell nucleus was stained at room temperature with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 10 min. In the end, the sections were fixed, and the images were obtained by using a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II, Germany). To quantify the TLR3+NeuN cell profiles in TNC, four slices of each of the three mice were randomly selected from each group. Using 60× the objective lens captures the square at the center of the TNC surface (212 × 212 µm²) Image. We used image analysis software (Image J 1.52q, Wayne Rasband, USA) to count all immune-responsive cell counts and analyze CGRP fluorescence intensity.

Statistical analysis

We use GraphPad Prism version 9.3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA 92108, USA) for graph generation and statistical analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk was employed to assess the normality of the data distribution. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. This study determined the differences between the two groups through an unpaired Student’s t-test. We apply analysis of variance (ANOVA) to three or more groups and then perform a multiple comparison Tukey post hoc test. Behavioral data were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance with Turkey post hoc analysis. Results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

TLR3 expression increased in TNC neurons after NTG administration

To explore the localization of TLR3 in specific cell types in TNC, double immunofluorescence staining was employed to observe the localization of TLR3. We observed that almost all TLR3-positive cells were double-labeled with NeuN (a marker of neurons; Figure 2(a)). The results showed that TLR3 is expressed in neurons, and non-coexpressed with Iba1 (a marker of microglia) and GFAP (a marker of astrocytes) in the TNC. What’s more, after the administration of NTG, the number of TLR3+neuron was significantly upregulated compared to that in the VEH group (Figure 2(b)). These results suggest that TLR3 is upregulated in TNC Neuron in the NTG-induced CM model.

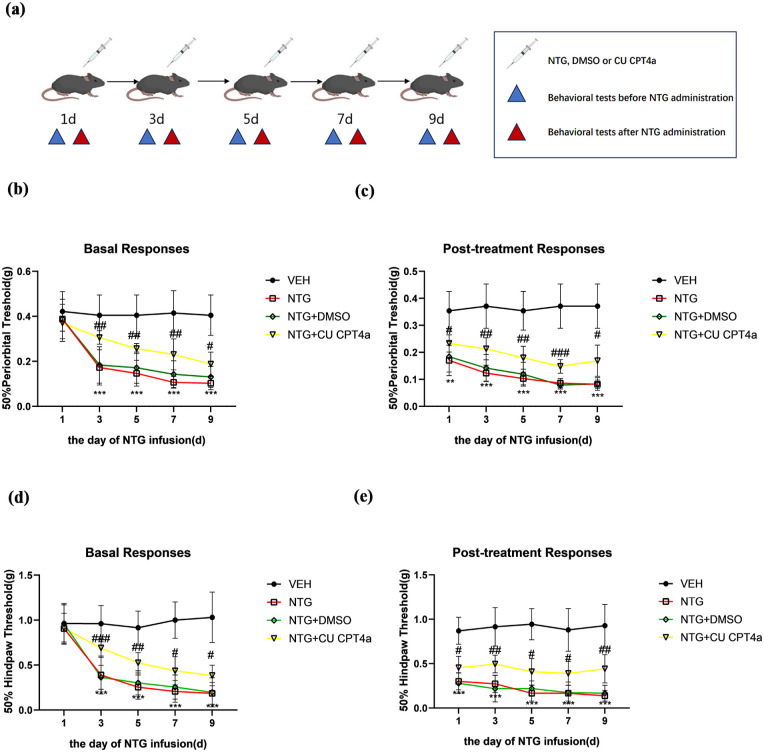

The application of the TLR3 antagonist attenuated CM-associated mechanical allodynia

In this experiment, mice were treated with CU CPT4a (5 mg/kg, i.p.) or a vehicle (equal volume of DMSO) every other day for 9 days before NTG injection (Figure 3(a)). We observed that the thresholds for paw and periorbital withdrawal from a mechanical stimulus in mice treated with NTG or NTG+DMSO gradually decreased in a time-dependent manner before and 2 h after NTG injection (Figure 3(b)–(e)). Specifically, repeated administration of NTG produced progressive and sustained basal hypersensitivity reactions, as well as acute allodynia. To determine whether TLR3 in TNC neurons plays a crucial role in NTG-induced pain behavior, mice received daily treatment with the TLR3 selective antagonist CU CPT4a before NTG administration every other day (n = 10 per group). Chronic treatment with CUCPT4a significantly inhibited NTG-induced basal hypersensitivity and mechanical allodynia (Figure 3(b)–(e)).

Figure 3.

TLR3 antagonist CU CPT4a inhibited NTG-induced mechanical allodynia. Repeated treatment with CU CPT4a or vehicle (equal volumes of DMSO) every other day before NTG injections for 9 days (a). Repeated treatment with CU CPT4a inhibited basal hind paw mechanical (b) and periorbital mechanical allodynia (d). Post-treatment responses, including hind paw mechanical (e) and periorbital mechanical allodynia (c), were estimated 2 h after NTG administration.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM; two-way ANOVA and Turkey post hoc analysis; n = 10 per group.

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the vehicle group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 compared to the NTG group.

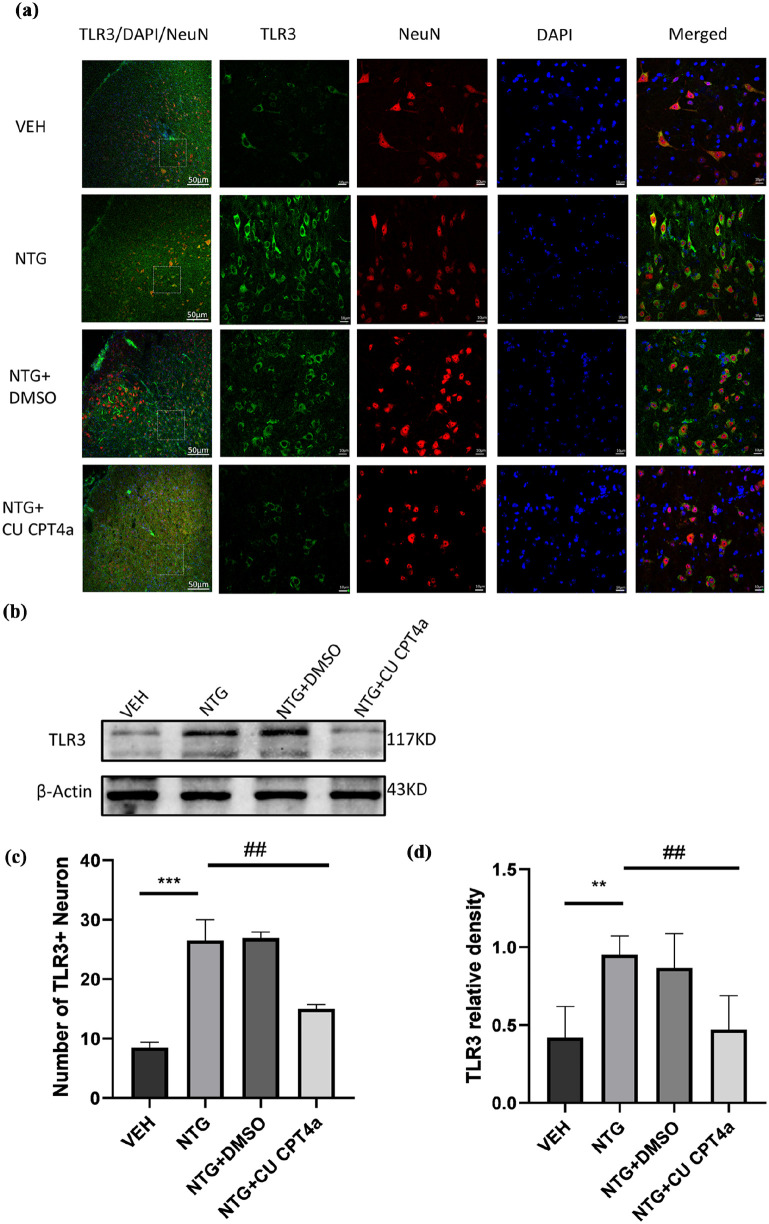

TLR3 inhibitor CU CPT4a attenuated NTG-induced expression of TLR3 in the TNC

To explore whether the expression of TLR3 could be related to chronic migraine, WB and immunofluorescence were used to measure the expression of TLR3 in the TNC. Our study has shown that repeated NTG administration significantly increased the protein expression levels of TLR3 in the TNC (Figure 4(a) and (d)). Compared with the NTG administration group, the Counting of TLR3-positive cells in the TNC was decreased by CU CPT4a (Figure 4(a) and (d)). Consistent results were found by the western blot (Figure 4(b) and (c)).

Figure 4.

TLR3 antagonist CU CPT4a reduced the expression of TLR3 in TNC. (a, d) The first image on the far left shows the location of the TNC, marked with a white dashed box. Scale bar: 50 µm. The images on the right show images with higher magnification. Scale bar: 10 µm (a). Quantitative analysis of the number of TLR3+Neuron in the TNC in a 212 × 212 µm² visual field of each section per mouse after NTG injection (d); n = 4 per group, three sections from each mouse; (b, c) Immunoblot analysis of TLR3 (n = 5).

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests.

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the VEH group; ##p < 0.01 compared to the NTG group.

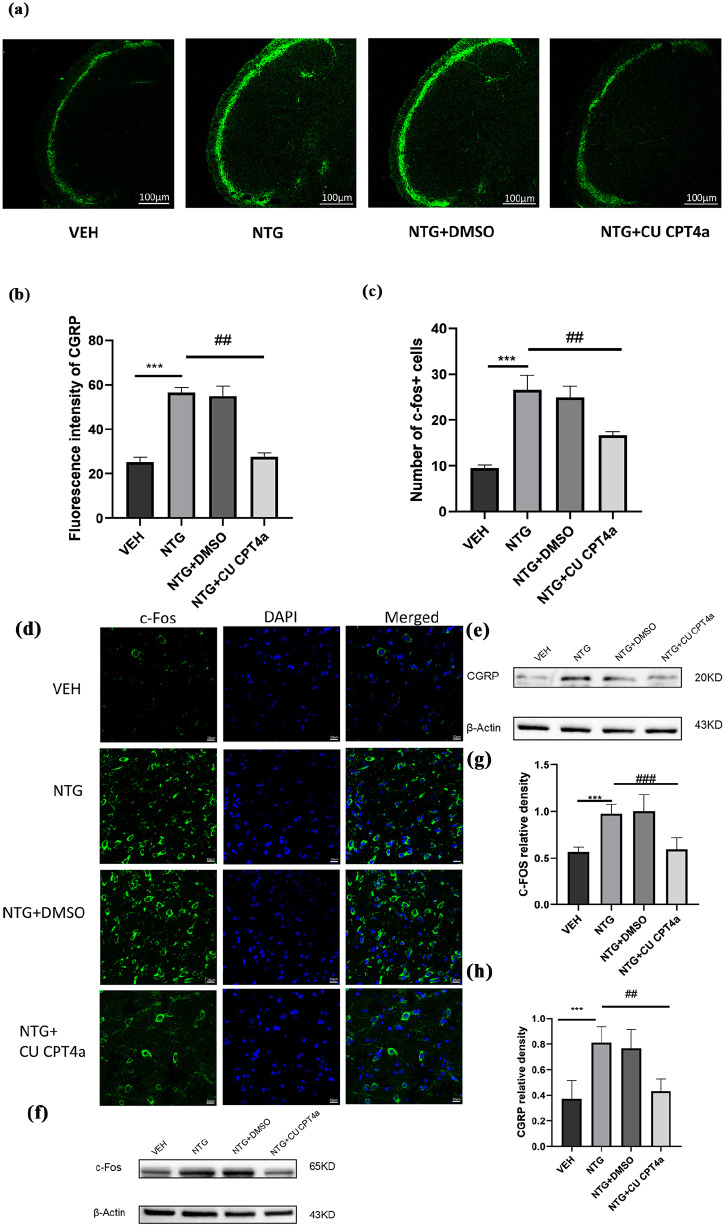

CU CPT4a downregulated CGRP and c-Fos expression in the TNC in the NTG-induced CM model

C-Fos and CGRP as markers of central sensitization in migraine,38,39 To determine whether CM-like hypersensitivity is related to CGRP, we detected the expression levels of CGRP in TNC using immunofluorescence(n = 4/group, 3 slices per mouse) and WB assay (n = 5 in each group; Figure 5(a)–(h)). Compared with the control group, we observed a significant increase in the immunofluorescence intensity of CGRP fibers in the TNC of the NTG group was significantly enhanced (Figure 5(b)) and the difference was statistically significant. What’s more, we also measured the levels of c-Fos, which is widely recognized as a reliable marker for the activation of nociceptive neurons following nociceptive stimulation, using both immunofluorescence and WB assay. Compared to the VEH group, the number of c-Fos immunoreactive positive cells in TNC of the NTG-treated group sharply increased (Figure 5(c) and (d)). To evaluate whether TLR3 affects the expression of CGRP and c-Fos, we intraperitoneally injected CU CPT4a, an inhibitor of TLR3. Compared to the NTG administration group, these results indicate that the inhibitor of TLR3 not only significantly decreased the immunofluorescence intensity of CGRP but also decreased the number of c-Fos immunoreactive positive cells (Figure 5(b) and (c)) in the TNC. Observing consistent results by WB (Figure 5(e)–(h)).

Figure 5.

TLR3 blockade results in the downregulation of c-Fos and CGRP expression. (a–d) In the TNC, quantitative analysis of CGRP immunofluorescence intensity; Scale bars: 100 μm (a, b) and c-Fos immunoreactive cells; Scale bars: 10 μm (c, d). n = 4 for each group, each mouse was selected for three slices for analysis. (e–h) Immunoblot analysis of c-Fos and CGRP (n = 5).

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests.

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the VEH group; ##p < 0.01 compared to the NTG group.

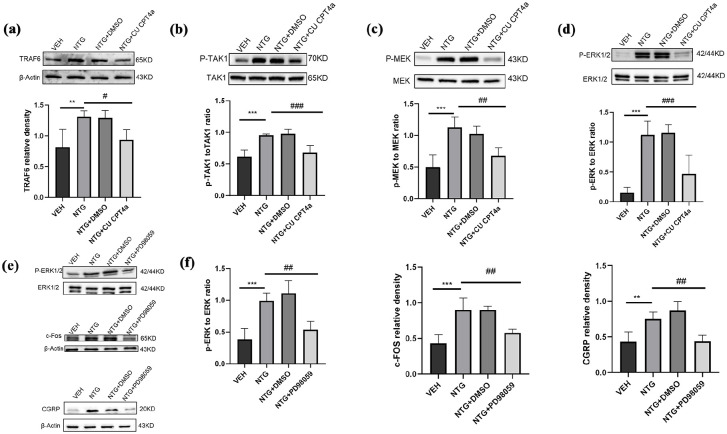

TLR3 regulates the expression of c-Fos through the ERK signaling pathway

To determine whether TLR3 regulates the expression of c-Fos through the ERK signaling pathway in CM, we detected the expression levels of proteins related to this pathway through Western blotting. Compared to the VEH group, the endogenous expression levels of c-Fos, CGRP, MEK, and ERK in the NTG injection group were significantly increased (p < 0.001; Figures 6(c) and (d) and 5(e)–(h)). To further validate whether TLR3 regulates the expression of c-Fos through this pathway, we inhibited TLR3 by systematically administrating its antagonist CU CPT4a (5 mg/kg) and the specific ERK inhibitor (PD98059, 10 mg/kg; n = 5 in each group). We found that the expression of c-Fos, CGRP, phosphorylation of MEK and ERK in the TNC were significantly reduced compared to the NTG group (p < 0.05; p < 0.01; p < 0.001; Figures 5(e)–(h) and 6(c)–(f)).

Figure 6.

TLR3 regulates the expression of c-Fos and CGRP by activating the ERK signaling pathway. (a–d) Immunoblot analysis was performed in the VEH, NTG, NTG+DMSO, and NTG+CU CPT4a groups for p-MEK1/2 to MEK1/2 ratio, p-ERK1/2 to ERK1/2 ratio, p-TAK1 to TAK1 ratio, and TRAF6 (n = 5). (e–f) Immunoblot analysis was performed in the VEH, NTG, NTG+DMSO, and NTG+PD98059 groups for p-ERK1/2 to ERK1/2 ratio, CGRP and c-Fos (n = 5).

Data are the mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus the VEH group, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 versus the NTG group.

The expression levels of phosphorylated ERK, c-Fos, and CGRP were significantly reduced in the PD98059-treated CM mice compared to the NTG group (p < 0.05; p < 0.01; p < 0.001; Figure 6(e)–(f)). These results indicate that TLR3 regulates the expression of c-Fos through the ERK signaling pathway.

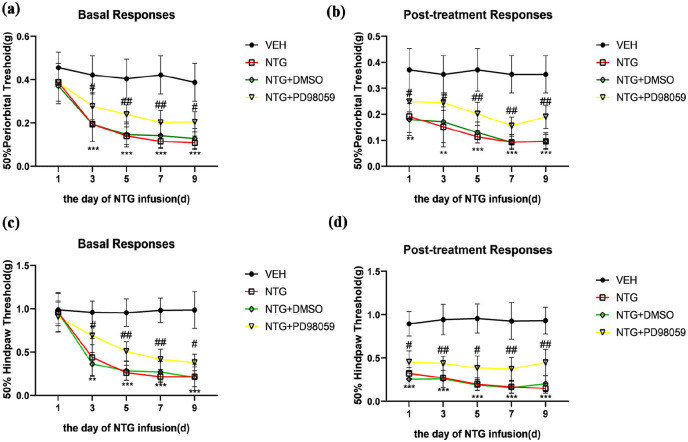

ERK inhibition attenuates CM-related pain hypersensitivity

To further validate the impact of the ERK pathway on CM, we administered PD98059 (10 mg/kg, i.p.), a potent antagonist of MEK, before each NTG injection and assessed its effect on pain hypersensitivity in CM mice. Behavioral data indicated that PD98059 significantly increased both the basal and acute mechanical withdrawal thresholds compared to the NTG group (Figure 7(a)–(d)). Our study demonstrated that the inhibition of ERK activity may effectively alleviate pain hypersensitivity in CM mice to a certain extent.

Figure 7.

ERK inhibition attenuates NTG-induced pain hypersensitivity. PD98059 effectively prevented the decrease in both basal and acute mechanical withdrawal thresholds in the periorbital area (a, b) and the hind paw (c, d). Acute hypersensitivity reactions were detected 2 h after each NTG treatment.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM; two-way ANOVA and Turkey post hoc analysis; n = 10 per group.

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the VEH group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 compared to the NTG group.

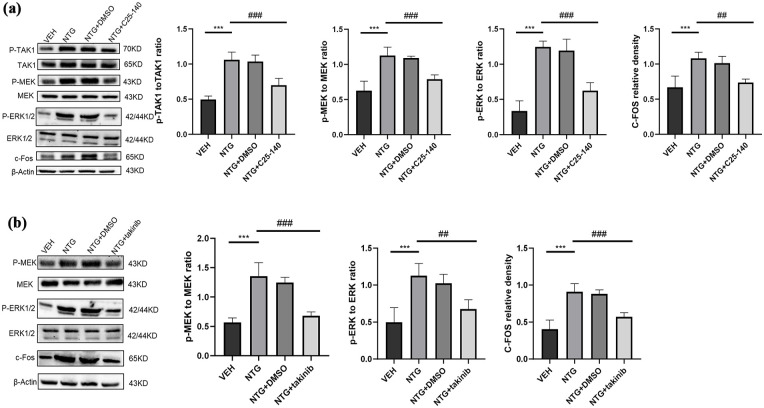

TLR3 regulates the ERK signaling pathway by TRAF6/TAK1 axis

To determine whether TLR3 regulates the ERK signaling pathway in CM by TRAF6/TAK1 axis, we detected the expression levels of proteins related to this pathway through Western blotting. Compared to the VEH group, the endogenous expression levels of TRAF6 and TAK1 in the NTG injection group were significantly increased (p < 0.05; p < 0.01; p < 0.001; Figures 6(a) and (b) and 8(a)). To further validate whether TLR3 regulates the ERK pathway by TRAF6/TAK1 axis, we inhibited TRAF6 by systematically administrating its antagonist C25-140 (10 mg/kg) and the specific TAK1 inhibitor (takinib, 50 mg/kg; n = 5 in each group). We found that compared with the NTG group, the proteins of the ERK signaling pathway in TNC were significantly inhibited (p < 0.05; p < 0.01; p < 0.001; Figure 8(a) and (b)).

Figure 8.

TLR3 regulates the ERK signaling pathway by TRAF6/TAK1 axis. (a) Immunoblot analysis of p-TAK1 to TAK1 ratio, p-MEK to MEK ratio, p-ERK to ERK ratio, and c-Fos were conducted in the indicated groups (n = 5). (b) Immunoblot analysis of p-MEK to MEK ratio, p-ERK to ERK ratio, and c-Fos were conducted in the indicated groups (n = 5).

Data are the mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus the VEH group, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 versus the NTG group.

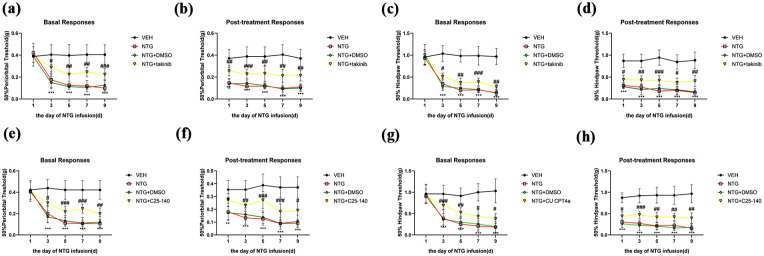

Blocking TRAF6 and TAK1 alleviates CM-related pain hypersensitivity in CM mice

To further validate the impact of the TRAF6-TAK1 axis on CM, we administered C25-140 (10 mg/kg, i.p.) and takinib (50 mg/kg, i.p.) before each NTG injection and assessed their effect on pain hypersensitivity in CM mice. Behavioral data indicated that C25-140 and takinib significantly increased both the basal and acute mechanical withdrawal thresholds compared to the NTG group (Figure 9(a)–(h)). Our study demonstrated that the inhibition of TRAF6 and TAK1 may effectively alleviate pain hypersensitivity in CM mice to a certain extent.

Figure 9.

Blocking TRAF6 and TAK1 alleviates CM-related pain hypersensitivity in CM mice. (a–h) C25-140 and takinib effectively prevented the decrease in both basal and acute mechanical withdrawal thresholds in the periorbital area and the hind paw. Acute hypersensitivity reactions were detected 2 h after each NTG treatment.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM; two-way ANOVA and Turkey post hoc analysis; n = 10 per group.

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the VEH group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 compared to the NTG group.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to investigate whether TLR3 mediates central sensitization in CM mice by TRAF6-TAK1 axis modulating the ERK signaling pathway. Previous research has suggested that repeated NTG stimulation also induces acute allodynia and basal hypersensitivity reactions in the hind paw and periorbital, these observed behaviors are believed to be central sensitization. 20 In the current study, we propose several new findings as follows.

Firstly, we found that the expression level of TLR3 increased after repeated NTG injections, and highly selective inhibitors of TLR3 attenuated pain hypersensitivity in mice and TLR3 expression levels in CM. Secondly, we showed in the first in-vivo experiment that the TLR3 receptor expressed in the trigeminal neurons of CM mice activated the downstream ERK pathways. Thirdly, the administration of PD98059, a potent antagonist of MEK, to CM mice alleviated allodynia and inhibited the expression levels of c-Fos and CGRP in these mice. Fourthly the administration of C25-140 (a potent antagonist of TRAF6) and takinib (a potent antagonist of TAK1) to CM mice alleviated allodynia and inhibited the ERK signaling pathway in these mice. (Figure 10). Collectively, our data underscore the critical role of the TLR3-ERK axis as a key signaling mechanism regulating CM.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of how TLR3 promotes central sensitization by TRAF6-TAK1 axis modulating the ERK signaling pathway.

TLR3 participates in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases by producing inflammatory factors.40,41 However, there is limited research on the role of TLR3 in pain regulation. In the L5 spinal nerve ligation rat model, TLR3 has been shown to promote neuropathic pain by regulating autophagy. 42 So far, there is no evidence of a possible effect of the TLR3 receptor on migraine pathophysiology. In our study, we observed a significant upregulation of TLR3 expression at the TNC site in the CM mouse model. In addition, we also observed that the TLR3 antagonist CU CPT4a significantly alleviated mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in CM mice. These results indicate that TLR3 is involved in the induction of migraine hyperalgesia and the inhibition of TLR3 with the selective individual TLR3 receptor antagonists may be an effective strategy for the prevention of migraine.

To establish an animal model of CM, we utilized chronic intermittent intraperitoneal injections of NTG (10 mg/kg), Chronic administration of NTG in mice not only leads to acute mechanical allodynia but also results in a decrease in the basal mechanical threshold of the hind paw. NTG is a reliable trigger for migraine and can simulate the clinical characteristics of CM patients,25,43 who may experience hyperalgesia or allodynia in the head and extra head areas (such as the neck and forearm). Over the years, the chronic migraine mouse model established through repeated intraperitoneal injections of NTG has been generally accepted. 44

TLR3 is upregulated in TNC neurons in the NTG-induced CM model. Previous studies have reported the expression of TLR3 in microglia, neurons, and astrocytes. 45 However, this study provides no evidence to suggest that microglia and astrocytes express TLR3 in TNC. This lack of evidence may be attributed to variations in the animal models and pain models utilized in the experiment, as well as differences in the timing of TNC tissue extraction.

TRAF6 has been appreciated for its potential in neuropathic pain in recent years. It was revealed that TRAF6 knockdown significantly ameliorated mechanical pain in constriction injury (CCI) mice.14,46 TAK1 mediates chronic pain and cytokine production in mouse models of inflammatory, neuropathic, and primary pain. TAK1 small-molecule inhibitor, takinib, attenuates pain and inflammation in preclinical models of inflammatory, neuropathic, and primary pain. 13 The TRAF6-TAK1 axis plays a critical role in TLR3 activating the ERK signaling pathway. 12 In our study, we observed a significant upregulation of TNC TRAF6 and TAK1 expression in CM mice. Inhibition of TRAF6 and TAK1 significantly suppressed the ERK signaling pathway and alleviated mechanical hyperalgesia in CM mice. These data indicate that TLR3 regulates the ERK signaling pathway through the TRAF6-TAK1 axis in CM mice.

C-Fos has been widely recognized as a biomarker for neuronal activation. 47 Previous studies have shown that the ERK pathways are necessary for inducing c-Fos expression.21,22 CGRP, a key neuropeptide in the trigeminal nervous system, plays a significant role in both peripheral and central sensitization of migraines. 16 Previous studies have shown that chronic exposure to morphine increases the activation of ERK in dorsal root ganglion neurons and releases CGRP, leading to tolerance to morphine-like drugs. 48

In this study, we observed an increase in the levels of CGRP and c-Fos in TNC, which is associated with severe basal hypersensitivity in the CM model. Additionally, the TLR3 antagonist CU CPT4a inhibits the expression of CGRP and c-Fos. Since both CGRP and c-Fos are produced by neurons, and TLR3 is also expressed in these cells, our findings align with our focus on investigating TLR3-mediated central sensitization in CM mice by regulating the expression of c-Fos and CGRP.

To determine the potential mechanisms of neuronal activation in TNC, we investigated the molecular mechanisms by which TLR3 regulates the expression of c-Fos and CGRP. Research has demonstrated that TLR3 can modulate the activation of the ERK signaling pathway.12,49 Moreover, the ERK signaling pathway plays an important role in pain signal transduction, and the phosphorylation of ERK is closely related to the generation and maintenance of pain. Ji et al. 50 found that peripheral nociceptive stimuli can cause phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in spinal dorsal horn neurons. The pre-administration of MEK inhibitors to block ERK phosphorylation can significantly alleviate pain hypersensitivity caused by capsaicin, suggesting that ERK phosphorylation plays a crucial role in pain sensitization. 51 Consistent with previous findings, our results demonstrated that the expression levels of P-MEK and p-ERK significantly increased following NTG injection in CM mice, while CU CPT4a effectively reversed these effects. PD98059, a specific antagonist of MEK, significantly alleviated pain hypersensitivity in CM mice and downregulated the expression of CGRP and c-Fos. Therefore, these experiments suggest that TLR3 regulates c-Fos expression by modulating the ERK signaling pathway in the TNC of CM mice.

This experiment exhibits certain limitations. Firstly, gender has a certain impact on migraine,52,53 as estrogen has a certain impact on the transmission of pain mediators. 54 We established a migraine model using male C57BL/6 mice, and further research is needed on the role of TLR3 in female animal models. Second, the activation of the ERK signaling pathway by TLR3 is closely related to the production of inflammatory factors. 12 Therefore, additional research is necessary to ascertain whether TLR3 induces inflammatory factors that mediate central sensitization through this pathway. In addition, observing behavioral tests through intraperitoneal injection of drugs does not rule out the involvement of the peripheral nervous system in this process.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that the expression of TLR3 was upregulated in the TNC in a recurrent NTG-induced CM model. Inhibiting TLR3 expression alleviated hyperalgesia and reduced the elevation of biomarkers associated with central sensitization in CM, such as c-Fos and CGRP, by TRAF6-TAK1 axis modulating the ERK signaling pathway. In summary, we found that TLR3 is closely linked to the pathological mechanisms of migraine, suggesting it may serve as a potential new drug target for the clinical treatment of this condition.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CM, Chronic migraine; TNC, Trigeminal nucleus caudalis; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2; TLR3, Toll-like receptor3; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; CSD, Cortical Spreading Depression; NTG, Nitroglycerin; VEH, Vehicle; PBS, Phosphate-buffered saline; IF, Immunofluorescence; PFA, Paraformaldehyde; CGRP, Calcitonin gene-related peptide; ERK, phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase; TRAF6, Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; TAK1, Transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1.

Author contributions: BY contributed to the work design. Animal behavior experiments were performed by BY. Molecular biology experiments and the statistical analysis were performed by BY. BY wrote and completed the manuscript. ZMG revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Data availability: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Clinical Medical Research Center of Gansu Neurology (Grant numbers: 20JR10FA663) and the Expert Workstation of Academician Wang Longde from the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University.

Ethics approval: The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital with an approval number of D2023-165.

ORCID iD: Zhaoming Ge  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1620-7351

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1620-7351

References

- 1. Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, Steiner T, Zwart JA. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007; 27: 193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwedt TJ. Chronic migraine. BMJ 2014; 348: g1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet 2018; 391: 1315–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aurora SK, Brin MF. Chronic migraine: an update on physiology, imaging, and the mechanism of action of two available pharmacologic therapies. Headache 2017; 57: 109–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Long T, He W, Pan Q, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Liu C, Liu Q, Qin G, Chen L, Zhou J. Microglia P2X4 receptor contributes to central sensitization following recurrent nitroglycerin stimulation. J Neuroinflammation 2018; 15: 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park C, Lee S, Cho IH, Lee HK, Kim D, Choi SY, Oh SB, Park K, Kim JS, Lee SJ. TLR3-mediated signal induces proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine gene expression in astrocytes: differential signaling mechanisms of TLR3-induced IP-10 and IL-8 gene expression. Glia 2006; 53: 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dalpke A, Helm M. RNA mediated Toll-like receptor stimulation in health and disease. RNA Biol 2012; 9: 828–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghaemi A, Alizadeh L, Babaei S, Jafarian M, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Meuth SG, Kovac S, Gorji A. Astrocyte-mediated inflammation in cortical spreading depression. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 626–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghaemi A, Sajadian A, Khodaie B, Lotfinia AA, Lotfinia M, Aghabarari A, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Meuth S, Gorji A. Immunomodulatory effect of Toll-Like Receptor-3 ligand Poly I:C on cortical spreading depression. Mol Neurobiol 2016; 53: 143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang X, Gao R, Zhang C, Teng Y, Chen H, Li Q, Liu C, Wu J, Wei L, Deng L, Wu L, Ye-Lehmann S, Mao X, Liu J, Zhu T, Chen C. Extracellular RNAs-TLR3 signaling contributes to cognitive impairment after chronic neuropathic pain in mice. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023; 8: 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ko R, Park JH, Ha H, Choi Y, Lee SY. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β ubiquitination by TRAF6 regulates TLR3-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scarneo S, Zhang X, Wang Y, Camacho-Domenech J, Ricano J, Hughes P, Haystead T, Nackley AG. Transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) mediates chronic pain and cytokine production in mouse models of inflammatory, neuropathic, and primary pain. J Pain 2023; 24: 1633–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu Y, Wang L, Zhou C, Yuan Y, Fang B, Lu K, Xu F, Chen L, Huang L. MiR-31-5p regulates the neuroinflammatory response via TRAF6 in neuropathic pain. Biol Direct 2024; 19: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyer N, Dallel R, Artola A, Monconduit L. General trigeminospinal central sensitization and impaired descending pain inhibitory controls contribute to migraine progression. Pain 2014; 155: 1196–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iyengar S, Johnson KW, Ossipov MH, Aurora SK. CGRP and the trigeminal system in migraine. Headache 2019; 59: 659–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Impey S, Obrietan K, Storm DR. Making new connections: role of ERK/MAP kinase signaling in neuronal plasticity. Neuron 1999; 23: 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang L, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Yang L, Wang Y, Shan Z, Liang J, Xiao Z. Inhibiting PAC1 receptor internalization and endosomal ERK pathway activation may ameliorate hyperalgesia in a chronic migraine rat model. Cephalalgia 2023; 43: 3331024231163131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ji RR, Gereau RW, 4th, Malcangio M, Strichartz GR. MAP kinase and pain. Brain Res Rev 2009; 60: 135–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He W, Long T, Pan Q, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Zhang D, Qin G, Chen L, Zhou J. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation mediates IL-1β release and contributes to central sensitization in a recurrent nitroglycerin-induced migraine model. J Neuroinflammation 2019; 16: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim KH, Staudt LM. Toll-like receptor signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013; 5: a011247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karin M, Liu Z, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1997; 9: 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gauzzi MC, Del Cornò M, Gessani S. Dissecting TLR3 signalling in dendritic cells. Immunobiology 2010; 215: 713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain 1983; 16: 109–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pradhan AA, Smith ML, McGuire B, Tarash I, Evans CJ, Charles A. Characterization of a novel model of chronic migraine. Pain 2014; 155: 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheng K, Wang X, Yin H. Small-molecule inhibitors of the TLR3/dsRNA complex. J Am Chem Soc 2011; 133: 3764–3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu T, Zhu X, Huang C, Chen J, Shu S, Chen G, Xu Y, Hu Y. ERK inhibition reduces neuronal death and ameliorates inflammatory responses in forebrain-specific Ppp2cα knockout mice. FASEB J 2022; 36: e22515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Louter MA, Bosker JE, van Oosterhout WP, van Zwet EW, Zitman FG, Ferrari MD, Terwindt GM. Cutaneous allodynia as a predictor of migraine chronification. Brain 2013; 136: 3489–3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bates EA, Nikai T, Brennan KC, Fu YH, Charles AC, Basbaum AI, Ptácek LJ, Ahn AH. Sumatriptan alleviates nitroglycerin-induced mechanical and thermal allodynia in mice. Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burstein R, Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, Ransil BJ, Bajwa ZH. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol 2000; 47: 614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vuralli D, Wattiez AS, Russo AF, Bolay H. Behavioral and cognitive animal models in headache research. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Pan Q, Tian R, Wen Q, Qin G, Zhang D, Chen L, Zhang Y, Zhou J. Repeated oxytocin prevents central sensitization by regulating synaptic plasticity via oxytocin receptor in a chronic migraine mouse model. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bonin RP, Bories C, De Koninck Y. A simplified up-down method (SUDO) for measuring mechanical nociception in rodents using von Frey filaments. Mol Pain 2014; 10: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 1994; 53: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen WJ, Niu JQ, Chen YT, Deng WJ, Xu YY, Liu J, Luo WF, Liu T. Unilateral facial injection of Botulinum neurotoxin A attenuates bilateral trigeminal neuropathic pain and anxiety-like behaviors through inhibition of TLR2-mediated neuroinflammation in mice. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu T, Han Q, Chen G, Huang Y, Zhao LX, Berta T, Gao YJ, Ji RR. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to chronic itch, alloknesis, and spinal astrocyte activation in male mice. Pain 2016; 157: 806–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang L, Zhang Y, Jing F, Long T, Qin G, Zhang D, Chen L, Zhou J. P2X7R-mediated autophagic impairment contributes to central sensitization in a chronic migraine model with recurrent nitroglycerin stimulation in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2021; 18: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Iyengar S, Ossipov MH, Johnson KW. The role of calcitonin gene-related peptide in peripheral and central pain mechanisms including migraine. Pain 2017; 158: 543–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jing F, Zhang Y, Long T, He W, Qin G, Zhang D, Chen L, Zhou J. P2Y12 receptor mediates microglial activation via RhoA/ROCK pathway in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis in a mouse model of chronic migraine. J Neuroinflammation 2019; 16: 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Freitag K, Sterczyk N, Wendlinger S, Obermayer B, Schulz J, Farztdinov V, Mülleder M, Ralser M, Houtman J, Fleck L, Braeuning C, Sansevrino R, Hoffmann C, Milovanovic D, Sigrist SJ, Conrad T, Beule D, Heppner FL, Jendrach M. Spermidine reduces neuroinflammation and soluble amyloid beta in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J Neuroinflammation 2022; 19: 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang J, Liu Y, Liu Y, Zhu K, Xie A. The association between TLR3 rs3775290 polymorphism and sporadic Parkinson’s disease in Chinese Han population. Neurosci Lett 2020; 728: 135005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen W, Lu Z. Upregulated TLR3 promotes neuropathic pain by regulating autophagy in rat with L5 spinal nerve ligation model. Neurochem Res 2017; 42: 634–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Akerman S, Karsan N, Bose P, Hoffmann JR, Holland PR, Romero-Reyes M, Goadsby PJ. Nitroglycerine triggers triptan-responsive cranial allodynia and trigeminal neuronal hypersensitivity. Brain 2019; 142: 103–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen H, Ji H, Zhang M, Liu Z, Lao L, Deng C, Chen J, Zhong G. An agonist of the protective factor SIRT1 improves functional recovery and promotes neuronal survival by attenuating inflammation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 2017; 37: 2916–2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bsibsi M, Ravid R, Gveric D, van Noort JM. Broad expression of Toll-like receptors in the human central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2002; 61: 1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao Y, Li T, Zhang L, Yang J, Zhao F, Wang Y, Ouyang Y, Liu J. TRAF6 promotes spinal microglial M1 polarization to aggravate neuropathic pain by activating the c-JUN/NF-kB signaling pathway. Cell Biol Toxicol 2024; 40: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hermanson O, Telkov M, Geijer T, Hallbeck M, Blomqvist A. Preprodynorphin mRNA-expressing neurones in the rat parabrachial nucleus: subnuclear localization, hypothalamic projections and colocalization with noxious-evoked fos-like immunoreactivity. Eur J Neurosci 1998; 10: 358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ma W, Zheng WH, Powell K, Jhamandas K, Quirion R. Chronic morphine exposure increases the phosphorylation of MAP kinases and the transcription factor CREB in dorsal root ganglion neurons: an in vitro and in vivo study. Eur J Neurosci 2001; 14: 1091–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jiang Z, Zamanian-Daryoush M, Nie H, Silva AM, Williams BR, Li X. Poly(I-C)-induced Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3)-mediated activation of NFκB and MAP kinase is through an interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-independent pathway employing the signaling components TLR3-TRAF6-TAK1-TAB2-PKR. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 16713–16719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ji RR, Befort K, Brenner GJ, Woolf CJ. ERK MAP kinase activation in superficial spinal cord neurons induces prodynorphin and NK-1 upregulation and contributes to persistent inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 478–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Obata K, Yamanaka H, Dai Y, Tachibana T, Fukuoka T, Tokunaga A, Yoshikawa H, Noguchi K. Differential activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase in primary afferent neurons regulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression after peripheral inflammation and nerve injury. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 4117–4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Labastida-Ramírez A, Rubio-Beltrán E, Villalón CM, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Gender aspects of CGRP in migraine. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Marcus R. Study provides new insight into female sex hormones and migraines. JAMA 2023; 329: 1439–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]