Abstract

Purpose

To report the rates of risk-reducing surgery (RRS) following germline testing for BRCA1/2 (likely) pathogenic variants (BRCApv) and to assess the impact of RRS and BRCA status on survival after surgical treatment for unilateral breast cancer (BC).

Methods

We identified 7145 women with BC (2000–2017), a BRCA test and median follow-up of 10.8 years from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group’s clinical database. Distant recurrence-free (DRFS) and overall survival (OS) according to BRCA status were evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Hazard ratios (HR) for BRCApv vs. BRCA wild-type, contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy (CRRM), and risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RRBSO), including interaction tests, were estimated using multivariable Cox models.

Results

Among BRCA1pv carriers (n = 403), CRRM rates were higher than in BRCA2pv (n = 317) (66% vs. 52%, p < 0.001) and more likely to receive timely testing, i.e., within 6 months of BC diagnosis (75% vs. 52%, p = 0.004). Regarding RRBSO rates, no differences were observed. CRRM was associated with significantly improved DRFS (HR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.51–0.78) and OS (HR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.51–0.82), independently of BRCA status and age. RRBSO was associated with improved OS only in BRCApv carriers, specifically, those aged ≥ 50 years (HR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.26–0.75). BRCApv (irrespective of affected gene) was associated with worse DRFS (HR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.06–1.63); however, this was only evident after 2 years of follow-up (HR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.22–1.93). BRCApv was not significantly associated with worse OS (HR = 1.25, 95%CI 0.98–1.58).

Conclusion

Timely germline testing at BC diagnosis might increase CRRM rates in BRCApv carriers, thereby improving survival.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10549-025-07726-2.

Keywords: Genetic screening, Hereditary breast cancer, Danish breast cancer cooperative group, Risk-reducing surgery, Contralateral mastectomy

Introduction

Germline pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes (BRCApv) account for 3–5% of breast cancer (BC) incidence and are linked to hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome [1]. Female BRCApv carriers have a cumulative risk of BC up to 70% and ovarian cancer (OC) up to 44% [2, 3]. BRCA1pv carriers with stage I–III (early) unilateral BC have an increased cumulative risk of contralateral BC (CBC) of 40% compared with 17% for BRCA2pv carriers [2, 3]. Healthy BRCApv carriers are offered risk-reducing care, i.e., intensified cancer surveillance, family genetic counseling, and cancer risk-reducing surgery (RRS) [4, 5]. RRS include bilateral mastectomy, risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RRBSO), or both [6]. Knowledge of germline BRCA status impacts the choice of surgical treatment, e.g., patients might opt for a mastectomy instead of breast-conserving surgery combined with a contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy (CRRM) [7, 8]. CRRM is proven to reduce the risk of CBC by at least 90%, with the evidence suggesting decreased BC-specific mortality and improved overall survival (OS), albeit with some selection bias, such as “healthier people choosing or being recommended for CRRM” [9, 10]. On the contrary, BRCA wild-type (BRCAwt) carriers might opt out of a contralateral mastectomy—a procedure associated with a negative psychological impact and less clear evidence of a risk-reductive effect in this patient group [7, 11–13].

Increasing evidence advocates mainstreaming germline BRCA testing (hereinafter referred to as BRCA testing) for women with early BC to promote a risk-reducing approach [7, 14–16]. The most recent American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend BRCA testing in all patients with BC before the age of 65 and for selected patients over 65 [17]. However, both early and recent studies have questioned the survival benefit of CRRM for BRCApv carriers compared to patients with BRCAwt [18–20]. Furthermore, the evidence of worse survival in patients with BRCApv-associated BC is also conflicting, as is the evidence regarding the differing outcomes of BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv [9, 20–23].

In this nationwide and population-based retrospective study, we aimed to describe how the BRCA test timing and test results influenced the uptake of RRSs among females diagnosed with early BC in Denmark from 2000 to 2017. We hypothesized that timely identification of BRCApv (within 6 months of BC diagnosis) would lead to a higher uptake of RRSs and improved survival [24]. We compared survival between BRCApv and BRCAwt carriers using Kaplan–Meier methods and multivariable Cox models, addressing previous conflicting and potentially biased results [19–21, 23, 25–27]. By interaction tests, we examined whether BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv had different impacts on survival due to their distinct clinicopathological characteristics [1]. Finally, we explored the effects of RRSs according to BRCA status (BRCApv vs. BRCAwt and BRCA1 vs. BRCA2), considering different BC recurrence risks and, according to age at diagnosis, addressing questionable risk-reducing effects in older (> 50 years) patients [2, 25, 28–30].

Patients and methods

Study setting and design

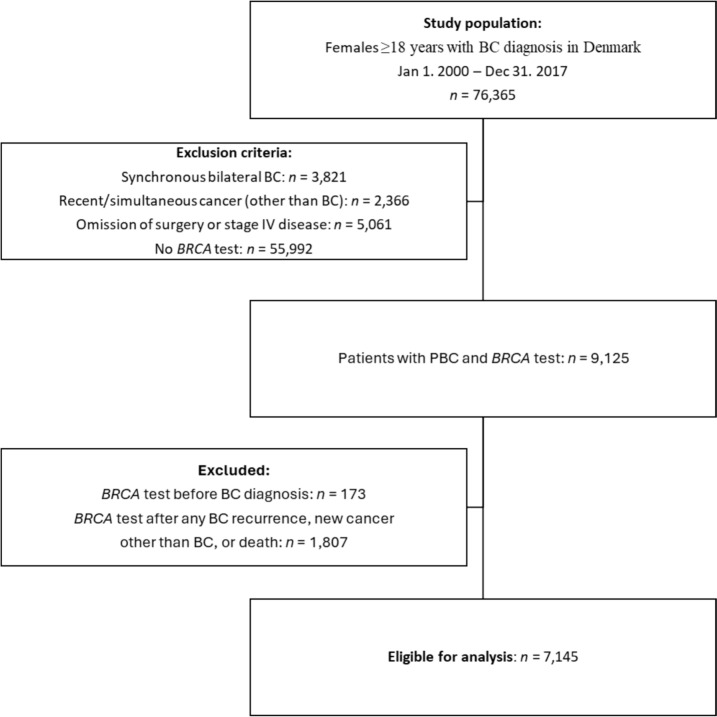

From the clinical Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) database, we identified females (sex assigned at birth) ≥ 18 years of age with pathology-verified invasive BC between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2017 [31]. Exclusion criteria were no registered BRCA test in the DBCG BRCA repository, synchronous bilateral BC, stage 4 disease at or within 90 days after invasive BC, omission of cancer surgery, and recent (up to 9.5 years before BC) or simultaneous (within 90 days after BC) other invasive cancer. Patients with BRCA tests before BC, n = 173, or after the first event of loco-regional recurrence, CBC, other invasive cancer, or post-mortem, n = 1807, were excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trial profile. BC breast cancer, PBC primary breast cancer

Data sources

The clinical DBCG database provided data on primary diagnosis, immunohistochemistry, treatment, date and localization of recurrence, and follow-up time. Events of distant BC recurrence after previous loco-regional recurrence, CBC, or other malignancies were retrieved from records in the Danish Pathology Data Bank [32]. Data on definitive surgery, RRSs, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were retrieved from the National Patient Register [33]. Missing data on baseline tumor characteristics and staging were retrieved from the Danish Pathology Data Bank.

BRCA tests

BRCA testing was performed in five laboratories across Denmark, as previously described [34]. BRCA variants were classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics criteria and the Evidence-Based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles [35, 36]. Patients with germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic BRCA variants were clinically treated equally and comprised the BRCApv group. Patients with BRCA variants of uncertain significance, likely benign or benign variants, or any variants in other screened genes included in a multigene test panel comprised the group of BRCAwt.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS), defined as the time from the date of BC diagnosis to distant BC recurrence or death attributable to any cause, and complies with Standardized Definitions for Efficacy End Points version 2.0 [37]. The secondary endpoint was OS, defined as the time from BC to death of any cause. Alive and event-free patients were censored as of November 1, 2022, following a thorough update of events from multiple registries and manual revisions of electronic health records.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R for Windows, version 4.3.3. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics and treatment were summarized with counts and percentages. Categorical variables were formally tested using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. Missing values were treated as separate categories under the assumption of not missing at random. Age was formally tested using the Mann–Whitney Test.

Absolute DRFS and OS estimates were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and potential median follow-up was estimated with reverse Kaplan–Meier. Left truncation at the date of the BRCA test result was applied to all tested patients to avoid delayed entry selection bias. CRRM and RRBSO were analyzed as time-dependent covariates to address immortal time bias. Survival curves according to type and combination of RRS were plotted using the Simon and Makuch method, assuming that RRS uptake was independent of the patient’s prognosis. We assessed the effect of BRCApv status and RRSs on DRFS and OS in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for variables related to BC prognosis. Proportional hazards were assessed by a goodness-of-fit model and a formal test for independence between scaled Schoenfeld residuals and time. Time-varying effects were assessed to fulfill the proportional hazards assumption. Online Resource 1 describes the models in detail. Estimates for all variables included in the Cox models are presented in Online Resource 2 (Table 5: DRFS model) and Online Resource 3 (Table 6: OS model).

The Wald test was applied for CRRM and RRBSO differential effects in separate models, according to BRCA status and age (< 50 and ≥ 50 years of age at BC diagnosis). The cut-off at 50 years was chosen based on the current age criterion for BRCA testing in Denmark and previous research [38, 39]. P-values for overall effects were calculated using Likelihood-ratio tests. All p-values were two-sided with a significance level of 5%.

Results

Study cohort

Within the clinical DBCG database, we identified 7145 eligible females who, from 2000 through 2021, underwent BRCA testing after surgery for primary BC and before any BC recurrence, new invasive cancer, or death (Fig. 1). One patient was identified as a double BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv carrier (classified as a BRCA1pv), while an additional 402 had a BRCA1pv and 317 a BRCA2pv (Table 1). The 720 (10%) patients with a BRCApv were younger at the time of diagnosis (median age 43 vs. 47), with mainly ductal histological subtype and estrogen receptor (ER)-negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative phenotype. The tumors were characterized by higher malignancy grade and larger tumor size as compared to BRCAwt (all p < 0.001). Patients with BRCApv more frequently had a mastectomy, more received (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy, and fewer received adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET, all p < 0.001). The differences between BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv patients are also presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographical, tumor, and treatment characteristics for 7145 patients with germline BRCA testing after PBC

| BRCApv | p-Value | BRCA status | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1pva | BRCA2pv | BRCApv | BRCAwt | |||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| 403 | (56) | 317 | (44) | 720 | (10) | 6425 | (90) | |||

| Year of PBC diagnosis | 0.18 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| 2000 to 2005 | 84 | (21) | 72 | (23) | 156 | (22) | 933 | (15) | ||

| 2006 to 2011 | 138 | (34) | 124 | (39) | 262 | (36) | 2124 | (34) | ||

| 2012 to 2017 | 181 | (45) | 121 | (38) | 302 | (42) | 3368 | (57) | ||

| Age at PBC diagnosis (years) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| 18–39 | 174 | (43) | 93 | (29) | 267 | (37) | 1502 | (23) | ||

| 40–59 | 203 | (50) | 175 | (55) | 378 | (53) | 3855 | (60) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 26 | (6) | 49 | (15) | 75 | (10) | 1068 | (17) | ||

| Histologic type | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Ductal | 349 | (87) | 284 | (90) | 633 | (88) | 5344 | (83) | ||

| Lobular | 2 | (< 1) | 18 | (6) | 20 | (3) | 538 | (8) | ||

| Other | 50 | (12) | 14 | (4) | 64 | (9) | 521 | (8) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | (< 1) | 1 | (< 1) | 3 | (< 1) | 22 | (< 1) | ||

| ER/HER2 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| ER–/HER2– | 245 | (61) | 61 | (19) | 306 | (43) | 959 | (15) | ||

| ER–/HER2+ | 19 | (5) | 6 | (2) | 25 | (3) | 376 | (6) | ||

| ER+/HER2– | 94 | (23) | 194 | (61) | 288 | (40) | 3782 | (59) | ||

| ER+/HER2+ | 21 | (5) | 27 | (9) | 48 | (7) | 887 | (14) | ||

| Unknown | 24 | (6) | 29 | (9) | 53 | (7) | 421 | (7) | ||

| Malignancy grade | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Grade I | 7 | (2) | 27 | (9) | 34 | (5) | 1270 | (20) | ||

| Grade II | 76 | (19) | 132 | (42) | 208 | (29) | 2544 | (40) | ||

| Grade III | 258 | (64) | 133 | (42) | 391 | (54) | 1837 | (29) | ||

| Not graded | 62 | (15) | 25 | (8) | 87 | (12) | 774 | (12) | ||

| Nodal statusb | < 0.001 | 0.76 | ||||||||

| Node-negative | 252 | (63) | 139 | (44) | 391 | (54) | 3608 | (56) | ||

| 1–3 positive LN | 96 | (24) | 114 | (36) | 210 | (29) | 1840 | (29) | ||

| ≥ 4 positive LN | 40 | (10) | 40 | (13) | 80 | (11) | 669 | (10) | ||

| FNA-positive | 13 | (3) | 21 | (7) | 34 | (5) | 276 | (4) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | (< 1) | 3 | (1) | 5 | (1) | 32 | (< 1) | ||

| Tumor sizec | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| 0–10 mm | 32 | (8) | 52 | (16) | 84 | (12) | 1200 | (19) | ||

| 11–20 mm | 181 | (45) | 105 | (33) | 286 | (40) | 2694 | (42) | ||

| 21–50 mm | 170 | (42) | 142 | (45) | 312 | (43) | 2210 | (34) | ||

| ≥ 50 mm | 20 | (5) | 17 | (5) | 37 | (5) | 282 | (4) | ||

| Unknown | 0 | (0) | 1 | (< 1) | 1 | (< 1) | 39 | (1) | ||

| Definitive surgeryd | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Mastectomy | 137 | (34) | 69 | (22) | 206 | (29) | 1273 | (20) | ||

| Mastectomy with RT | 85 | (21) | 108 | (34) | 193 | (27) | 1619 | (25) | ||

| Breast-conserving with RT | 181 | (45) | 140 | (44) | 321 | (45) | 3533 | (55) | ||

| (Neo)adjuvant chemotherapye | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Any administered | 362 | (90) | 246 | (78) | 608 | (84) | 4689 | (73) | ||

| No | 41 | (10) | 71 | (22) | 112 | (16) | 1736 | (27) | ||

| Endocrine therapy | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Any administered | 115 | (29) | 214 | (68) | 329 | (46) | 4306 | (67) | ||

| No | 288 | (71) | 103 | (32) | 391 | (54) | 2119 | (33) | ||

| Comorbidityf | 0.08 | 0.30 | ||||||||

| CCI 0 | 357 | (89) | 285 | (90) | 642 | (89) | 5670 | (88) | ||

| CCI 1 | 34 | (8) | 16 | (5) | 50 | (7) | 542 | (8) | ||

| CCI ≥ 2 | 12 | (3) | 16 | (5) | 28 | (4) | 213 | (3) | ||

| Follow-up, median years (range) | 11.6 | (8.4–16.2) | 12.4 | (8.9–16.3) | 12.0 | (8.5–16.3) | 10.6 | (7.5–14.5) | ||

| Death | 60 | (15) | 60 | (19) | 120 | (17) | 721 | (11) | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 7 | (2) | 1 | (< 1) | 8 | (1) | 7 | (< 1) | ||

| Age, median years (range) | 57.2 | (55.0–69.5) | 56.5 | (56.5–56.5) | 56.9 | (55.3–67.8) | 61.6 | (60.3–68.2) | ||

CCI Charlson comorbidity index, DBCG Danish breast cancer cooperative group, ER– estrogen receptor-negative, HER2–/ + human epidermal growth factor receptor-negative/positive, ICD-8/-10 international classification of diseases, revision 8/10, LN lymph nodes, PBC primary breast cancer, RT radiotherapy

aOne patient is double-carrier, with both BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv, but is classified as BRCA1pv

bThe clinical node status was applied (radiologically determined with ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) or fine-needle aspirate from axillary nodes for patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Otherwise, the pathological nodal status was applied. If axillary dissection was performed and no LNs were found, the nodal status was determined as “unknown”

cFor patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the clinical tumor size (radiologically determined by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) was applied. Pathological tumor size was applied for patients with upfront surgery

dIntention-to-treat RT according to DBCG guidelines

eIncludes administered anti-HER2 treatment

fCCI was calculated using ICD-8 and ICD-10 codes for 19 chronic diseases retrieved from hospital records in the 10 years before the BC diagnosis (see Online resource 1 for further assumptions)

BRCA test timing and risk-reducing surgery

Among 7145 patients, 2169 (30%) received their BRCA test results within 6 months of BC diagnosis, thus representing timely testing (Table 2). Among those with timely testing, 154 (7%) had a BRCA1pv, while 88 (4%) had a BRCA2pv. RRS, either CRRM, RRBSO, or both, was conducted in 1677 (26%) of patients with BRCAwt compared to 369 (92%) of patients with BRCA1pv and 283 (89%) with BRCA2pv. Ninety-two of 181 patients (51%) with BRCA1pv and 53 of 140 (38%) with BRCA2pv opted for a subsequent bilateral mastectomy after initial breast-conserving surgery (data not shown). The uptake of RRBSO was similar (82%) in BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv carriers and there was no difference depending on test timing (p > 0.99). In contrast, the uptake of CRRM was higher in BRCA1pv compared to BRCA2pv (66% vs. 52%, p < 0.001) and higher if timely tested (75% vs. 52%, p = 0.004).

Table 2.

Proportions of patients with risk-reducing surgery according to BRCA test timing and the test result

| Risk-reducing surgery | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Median age at PBC diagnosis (IQR) | Median time from PBC to genetic testing, weeks (IQR) | Median time from PBC to CRRM, weeks (IQR) | Median time from PBC to RRBSO, weeks (IQR) | CRRM and RRBSO | CRRM only | RRBSO only | None | p-Valuea | |||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |||||||

| BRCA test <6 monthsb | 2169 (30%) | 0.009 | ||||||||||||

| BRCA1pv | 154 (7%) | 39 (33–48) | 14 (9–18) | 34 (29–80) | 45 (37–65) | 105 | (68) | 21 | (14) | 18 | (12) | 10 | (6) | |

| BRCA2pv | 88 (4%) | 44 (37–53) | 15 (10–20) | 43 (31–88) | 40 (30–55) | 45 | (51) | 10 | (11) | 24 | (27) | 9 | (10) | |

| BRCAwt | 1927 (89%) | 44 (38–52) | 15 (10–20) | 52 (29–106) | 68 (41–147) | 75 | (4) | 228 | (12) | 261 | (14) | 1363 | (71) | |

| BRCA test >6 monthsc | 4976 (70%) | 0.40 | ||||||||||||

| BRCA1pv | 249 (5%) | 42 (36–49) | 65 (38–284) | 101 (67–182) | 88 (56–239) | 121 | (49) | 18 | (7) | 86 | (35) | 24 | (10) | |

| BRCA2pv | 229 (5%) | 46 (39–56) | 79 (41–249) | 127 (76–319) | 96 (58–258) | 96 | (42) | 14 | (6) | 94 | (41) | 25 | (11) | |

| BRCAwt | 4498 (90%) | 48 (41–56) | 90 (43–333) | 95 (49–159) | 120 (56–264) | 129 | (3) | 243 | (5) | 741 | (16) | 3385 | (75) | |

BRCAwt wild-type BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, BRCApv pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, CRRM contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy, PBC primary breast cancer, RRBSO risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

aChi-squared test for distributions of risk-reducing surgery among BRCA1pv vs. BRCA2pv

bMann–Whitney U test for differences in age at PBC: BRCA1pv vs. BRCAwt p < 0.0001, BRCA2pv vs. BRCAwt p = 0.86

cMann–Whitney U test for differences in age at PBC: BRCA1pv vs. BRCAwt p < 0.0001, BRCA2pv vs. BRCAwt p = 0.03

Survival analysis

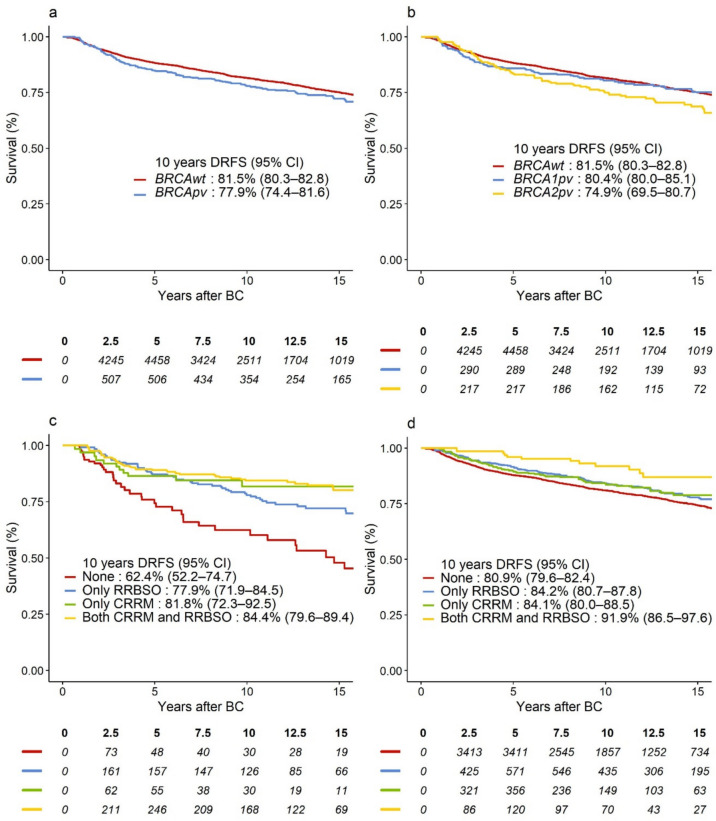

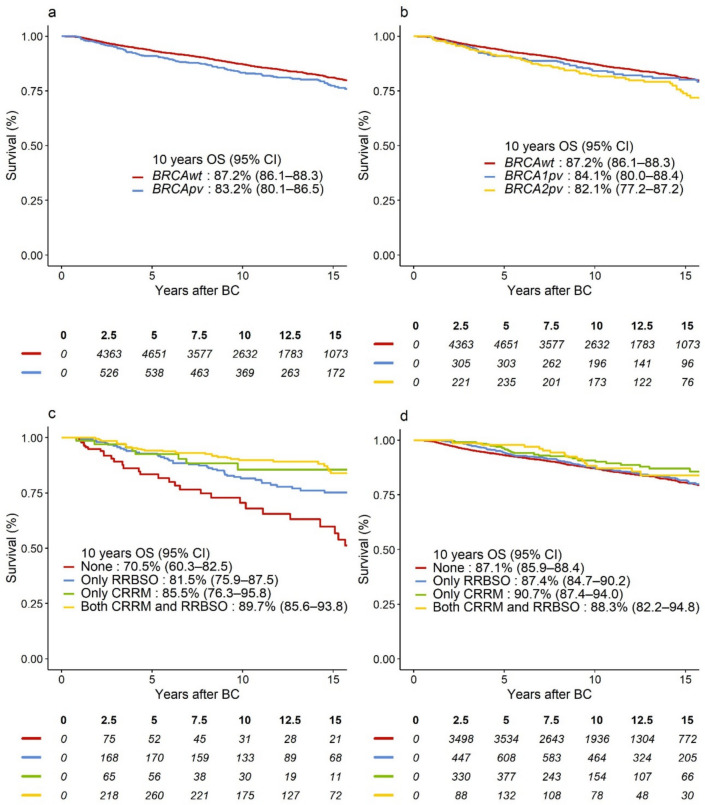

The potential median follow-up was 10.8 years. Of 1104 events in the DRFS analysis, 785 (71%) were distant BC recurrences and 319 (29%) were deaths as the first event. There were 841 events in the OS analysis. In unadjusted analysis, we observed 3.6% lower absolute 10-year DRFS and 4.0% lower 10 year OS for BRCApv vs. BRCAwt (Figs. 2a and 3a).

Fig. 2.

Survival curves representing DRFS in a BRCApv vs. BRCAwt carriers; b BRCA1pv vs. BRCA2pv vs. BRCAwt carriers; DRFS-curves according to type and combination of risk-reducing surgery for c BRCApv carriers, d BRCAwt carriers. BRCAwt wild-type BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, BRCApv pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, BC breast cancer, CI confidence interval, CRRM contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy, DRFS distant recurrence-free survival, RRBSO risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Fig. 3.

Survival curves representing OS in a BRCApv vs. BRCAwt carriers; b BRCA1pv vs. BRCA2pv vs. BRCAwt carriers; OS-curves according to type and combination of risk-reducing surgery for c BRCApv carriers, d BRCAwt carriers. BRCAwt wild-type BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, BRCApv pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, BC breast cancer, CI confidence interval, CRRM contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy; OS overall survival; RRBSO risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

When adjusted for baseline characteristics and treatment, including RRS, BRCApv status was associated with significantly worse DRFS, hazard ratio (HR) = 1.31 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.63), p = 0.01. However, this effect was mainly evident after 2 years of follow-up (HR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.22–1.93), while BRCApv did not significantly worsen the prognosis in years 0–2 (HR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.47–1.11), heterogeneity p < 0.001 (Table 3). In the adjusted analysis, BRCApv was associated with worse OS (HR = 1.25, 95% CI 0.99–1.59), which was similarly observed in Fig. 3a. However, this relation was not statistically significant, p = 0.07. Although BRCA2pv carriers exhibited the lowest absolute 10-year DRFS and OS (Figs. 2b and 3b, respectively), as compared to BRCA1pv, BRCA2pv was not associated with worse DRFS (heterogeneity p = 0.64, Table 3) or OS (heterogeneity p = 0.35, Table 4). Tables 5 (Online Resource 2) and Table 6 (Online Resource 3) show overall and adjusted HR estimates for all variables included in the models.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox model estimates for DRFS, showing adjusted HR and 95% CI for the overall effect of BRCApv vs. BRCAwt and for CRRM yes vs. no, and RRBSO yes vs. no. Time-varying effects (early vs. late and corresponding heterogeneity p-value) of BRCA status adjusting for non-proportional hazards

| Overall effect Adjusted HR (95% CI)a |

p-Value | Early effect adjusted HR (95% CI) | Late effect adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-Value for heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA statusb | |||||

| BRCApv vs. BRCAwt | 1.31 (1.06–1.63) | 0.01 | 0.72 (0.47–1.11) | 1.53 (1.22–1.93) | < 0.001 |

| Subgroup analysis: | |||||

| BRCA1pv vs. BRCAwt | 1.16 (0.88–1.54) | 0.71 (0.42–1.20) | 1.39 (1.01–1.90) | 0.64 | |

| BRCA2pv vs. BRCAwt | 1.47 (1.13;1.91) | 0.73 (0.36–1.49) | 1.66 (1.26–2.18) | ||

| CRRM | |||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) | < 0.001 | |||

| Interactions CRRM | |||||

| BRCAwt | 0.72 (0.56–0.93) | 0.06 | |||

| BRCApv | 0.49 (0.35–0.70) | ||||

| BRCA1pv | 0.38 (0.23–0.62) | 0.12 | |||

| BRCA2pv | 0.65 (0.40–1.04) | ||||

| BRCAwt < 50 years | 0.66 (0.49–0.88) | 0.14 | |||

| BRCAwt ≥ 50 years | 0.98 (0.63–1.55) | ||||

| BRCApv < 50 years | 0.47 (0.32–0.69) | 0.58 | |||

| BRCApv ≥ 50 years | 0.57 (0.31–1.05) | ||||

| RRBSO | |||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) | 0.20 | |||

| Interactions RRBSO | |||||

| BRCAwt | 0.96 (0.79–1.16) | 0.12 | |||

| BRCApv | 0.70 (0.50–0.99) | ||||

| BRCA1pv | 0.68 (0.42–1.11) | 0.86 | |||

| BRCA2pv | 0.73 (0.45–1.18) | ||||

| BRCAwt < 50 years | 0.96 (0.75–1.24) | 0.94 | |||

| BRCAwt ≥ 50 years | 0.98 (0.73–1.30) | ||||

| BRCApv < 50 years | 0.75 (0.51–1.09) | 0.54 | |||

| BRCApv ≥ 50 years | 0.66 (0.41–1.04) |

p-Values for heterogeneity correspond to tests for differential effects of CRRM and RRBSO according to BRCA status and age and for differences in BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv estimates in a subgroup analysis

BRCAwt wild-type BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, BRCApv pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genesl, CI confidence intervall, CRRM contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy, DRFS distant recurrence-free survival, ER estrogen receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor, HR hazard ratio, RRBSO risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

aVariables included in the model: BRCA status (BRCApv vs. BRCAwt), CRRM (time-dependent), RRBSO (time-dependent), age at diagnosis, Charlson Comorbidity Index, definitive surgery method, histological subtype, malignancy grading, tumor diameter, ER/HER2 status, nodal status, (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant endocrine therapy

bEarly (0–2 years) and late (> 2 years of follow-up) effects of BRCApv, including BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv, are presented to comply with the proportional hazard assumption

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox model estimates for overall survival, showing adjusted HR and 95% CI for the overall effect of BRCApv vs. BRCAwt and for CRRM yes vs. no, and RRBSO yes vs. no

| Overall effect adjusted HR (95% CI)a | p-Value | p-Value for heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA status | |||

| BRCApv vs. BRCAwt | 1.25 (0.98–1.58) | 0.07 | |

| Subgroup analysis | |||

| BRCA1pv vs. BRCAwt | 1.12 (0.82–1.53) | 0.29 | |

| BRCA2pv vs. BRCAwt | 1.37 (1.02–1.84) | ||

| CRRM | |||

| Yes vs. No | 0.64 (0.51–0.82) | < 0.001 | |

| Interactions CRRM | |||

| BRCAwt | 0.76 (0.57–1.00) | 0.07 | |

| BRCApv | 0.49 (0.33–0.72) | ||

| BRCA1pv | 0.38 (0.23–0.65) | 0.16 | |

| BRCA2pv | 0.66 (0.39–1.13) | ||

| BRCAwt < 50 years | 0.68 (0.49–0.96) | 0.20 | |

| BRCAwt ≥ 50 years | 1.00 (0.61–1.64) | ||

| BRCApv < 50 years | 0.47 (0.31–0.72) | 0.44 | |

| BRCApv ≥ 50 years | 0.62 (0.32–1.21) | ||

| RRBSO | |||

| Yes vs. No | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | 0.84 | |

| Interactions RRBSO | |||

| BRCAwt | 1.09 (0.89–1.33) | 0.03 | |

| BRCApv | 0.67 (0.46–0.98) | ||

| BRCA1pv | 0.76 (0.44–1.31) | 0.51 | |

| BRCA2pv | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) | ||

| BRCAwt < 50 years | 1.33 (1.03–1.72) | 0.03 | |

| BRCAwt ≥ 50 years | 0.85 (0.61–1.18) | ||

| BRCApv < 50 years | 0.87 (0.58–1.31) | 0.01 | |

| BRCApv ≥ 50 years | 0.44 (0.26–0.75) |

p-Values for heterogeneity correspond to tests for differential effects of CRRM and RRBSO according to BRCA status and age and for differences in BRCA1pv and BRCA2pv estimates in a subgroup analysis

BRCAwt wild-type BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, BRCApv pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, CI confidence interval, CRRM contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy, ER estrogen receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor, HR hazard ratio, RRBSO risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

aVariables included in the model: BRCA status (BRCApv vs. BRCAwt), CRRM (time-dependent), RRBSO (time-dependent), age at diagnosis, Charlson Comorbidity Index, definitive surgery method, histological subtype, malignancy grading, tumor diameter, ER/HER2 status, nodal status, (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant endocrine therapy

In the unadjusted analysis, BRCApv carriers who received any RRS showed improved 10 year survival (Figs. 2c and 3c) compared to those who opted out of RRS, while the risk-reducing effect of CRRM and RRBSO seemed less prominent for BRCAwt carriers (Figs. 2d and 3d). The most significant improvement in survival was observed in BRCApv carriers who opted for CRRM (alone or with RRBSO). The rate of CBC was 2% among those who opted for CRRM (26 of 1105) vs. 4% in the non-CRRM group (217 of 6040). In multivariable analysis, CRRM was associated with significantly better DRFS (adjusted HR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.51–0.78); p < 0.001) and better OS (adjusted HR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.51–0.81), p < 0.001. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, several interactions were explored. Interaction tests could not reject the null hypothesis of no difference in effects of CRRM in BRCApv carriers vs. BRCAwt, or in BRCA1 vs. BRCA2 (all heterogeneity p > 0.05). RRBSO was not significantly associated with DRFS or OS (p = 0.20 and p = 0.82, respectively) in the multivariable analyses. However, interaction tests revealed that RRBSO was associated with OS benefit for BRCApv (HR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.46–0.98), but not for BRCAwt (heterogeneity p = 0.03), and without differences according to the affected gene (heterogeneity p = 0.51, Table 4).

Patients ≥ 50 years of age at diagnosis

In the multivariable models, we tested for different effects of CRRM and RRBSO according to age at diagnosis and BRCA status. In BRCApv patients, CRRM was associated with improved DRFS regardless of age, showing HR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.32–0.69 and HR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.31–1.05, for those < 50 and ≥ 50 years of age at BC diagnosis, respectively, heterogeneity p = 0.58. Similarly, interaction tests showed no difference in CRRM effects for BRCAwt according to age, heterogeneity p = 0.14. In the OS model, tests for interaction between CRRM and age returned similar results (Table 4). RRBSO was associated with significantly improved OS for BRCApv carriers ≥ 50 years at diagnosis with HR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.26–0.75. Although RRBSO also decreased hazards for those < 50 at diagnosis, the effect was not significant, showing HR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.58–1.31, heterogeneity p = 0.01.

Discussion

In this large national cohort of 7145 females with primary BC, we observed an association between germline BRCA test timing and the uptake of RRS. Few BRCApv carriers (8–11%) completely opted out of RRSs, and around 80% opted for RRBSO irrespective of test timing and the affected gene. The uptake of CRRM was correspondingly high among timely tested BRCA1pv but was for BRCA2pv somewhat lower, and late testing reduced the uptake in both groups. The median time from PBC to genetic testing was approximately 15 weeks for timely tested patients, and the median time to CRRM was 34–43 weeks for timely tested BRCApv carriers. Patients with BRCApv (10%) had significantly higher hazards for events of distant BC relapse or death (DRFS) only after 2 years of follow-up (HR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.22–1.93). BRCApv carriers tended to have worse prognostic characteristics, including larger tumors, higher malignancy grading, and ER-negative/HER2-negative subtype. The multivariable analysis did not find a significant association with OS (HR = 1.25, 95% CI 0.98–1.58, p = 0.07), suggesting that the presence of BRCApv may not independently worsen survival outcomes. Instead, the prognosis highly depends on other factors included in the models, such as age, CCI, tumor characteristics and treatment. Patients with BRCA-associated BC were more heavily treated, i.e., received bilateral mastectomy and (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy more often, compared with BRCAwt, which might have improved the prognosis. Compared with BRCAwt, BRCA2pv was associated with worse survival outcomes in multivariable models but was not significantly different from BRCA1pv. Our results align with OS estimates from a meta-analysis by Liu et al. [21]. They found that although BRCA1pv was associated with worse OS compared to BRCA1wt (HR = 1.20, 95% CI 1.08–1.33; p = 0.0008) with worse outcomes in ≤ 5 years follow-up, and BRCA2pv with worse OS after 5 years of follow-up (HR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.22–1.58), combined BRCA1/2pv was not significantly associated with worse OS (HR = 0.98, p = 0.84) [21].

After being diagnosed with primary BC, women and their physicians’ primary concerns are the risks of disease recurrence and death [40]. Only a few tools have been developed and validated for predicting CBC risk, but none are currently implemented in national guidelines [41–43]. An increasing amount of BC patients opt for RRSs, with proven risk-reducing effects in BRCApv carriers and questionable effects in BRCAwt patients [6, 9, 10, 17, 19, 20, 39, 44–47]. The evidence of BRCA test timing on survival is poorly described, but studies show a coherence between BRCA testing at the time of BC diagnosis and surgical treatment decision, similar to our findings [8, 48, 49]. Only a few patients (n = 173) knew their germline BRCA status before PBC, of whom 44 (25%) opted out of bilateral mastectomy. By contrast, 225 patients (3%) opted for CRRM before BRCA testing, of whom 28 (12%) had BRCA1pv, 17 (8%) had BRCA2pv, and 180 (80%) were BRCAwt. This indicates that most Danish patients were genetically counselled prior to CRRM. In a previous cohort study, we have demonstrated that patients under 40 years of age at PBC and those with ER-negative/HER2-negative BC received BRCA testing more often, while the majority of patients still missed testing [34]. The survival benefit of CRRM that we observed among BRCApv patients was similar to previous findings and did not seem restricted to BRCA1 or young age (< 50) at diagnosis [6, 9, 45, 50, 51]. However, the OS benefit associated with RRBSO among BRCApv patients who were 50 years and older at primary diagnosis reflects mainly the prevention of secondary OC and less the endocrine suppression effect [51, 52]. Our results are of great importance for clinicians when discussing risk-reducing procedures with patients 50 years and older at BC diagnosis [8].

A Cochrane review found no evidence of survival benefit after CRRM among BRCAwt patients [5]. In contrast, our results suggest that CRRM might also reduce hazards for events of distant BC recurrence and death among these high-risk patients. Although the effects of RRSs were less pronounced in BRCAwt patients, we found only significantly lower effects of RRBSO in the OS model since these patients might have a lower risk of OC. However, given the low uptake of CRRM (11%) among BRCAwt patients, the results for this group should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, we miss information on patients who chose to undergo RRSs due to pathogenic variants in other high-risk genes such as TP53, STK11, PTEN, PALB2, and CDH1 or after pedigree-based BC risk assessment. The BRCAwt population in our study had a higher risk for recurrence than sporadic BC since they were referred to BRCA testing, which might explain the observed benefit from CRRM. During the study period, moderate cancer risk genes such as ATM, CHEK2, and BARD1 were not analyzed in Denmark [38, 53]. The uptake of CRRM in high-risk BRCAwt young females with BC in Denmark is high and comparable to this in other countries [7, 38, 54].

Sixty-one percent of BRCA1pv carriers in our cohort were ER- and HER2-negative, which is an indication for (neo-)adjuvant chemotherapy [55]. Most (90%) of BRCA1pv, 78% of BRCA2pv, and 73% of BRCAwt patients received chemotherapy (CT). CT was associated with significantly reduced hazards for both DRFS and OS (Online Resources 2 and 3). The reduced administration rate of CT might partially explain the poorer prognosis of BRCA2-associated BC, which was most often ER-positive (70%). Even though most of the BRCA2pv carriers with ER-positive BC received adjuvant ET, non-adherence to ET is evident among patients with this BC subtype, with an increased risk for relapse and death [56]. Furthermore, ER-positive status might have counterintuitive results in certain patient subgroups with mixed results reported [57–59]. Newer therapies for ER-positive BC, such as inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 and intensified focus on ET compliance, might benefit this subgroup [60]. Four out of five BRCApv carriers in our cohort had HER2-negative disease and had received CT and are potential candidates for adjuvant treatment with poly-ADP-ribose-polymerase inhibitors, such as olaparib [61]. However, olaparib is not currently approved in Denmark for this indication, leaving most of these patients without a targeted systemic treatment.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of our study lies in the evaluation of long-term outcomes for 720 BRCApv patients compared to 6425 BRCAwt patients who underwent BRCA testing after BC diagnosis with a median follow-up of 10.8 years. The integration of several national registries allowed us to analyze the timing of BRCA testing and the effects of test results on RRS decisions and survival. Missing data was primarily on HER2 prior to 2006 (Supplementary Methods, Online Resource 1). We assessed the effects of BRCApv and RRSs on time to distant BC recurrence or death (DRFS) and OS in multivariable Cox analysis, adjusting for known prognostic factors to minimize bias, as previously recommended [10, 62]. We also tested for differential effects of RRSs depending on the BRCA status and age at diagnosis, as hypothesized. In contrast, previous studies failed to analyze the effect of BRCA status using multivariable Cox regression models [19, 63]. Our primary outcome is clinically relevant, since distant BC recurrence is associated with the worst prognosis [21]. Furthermore, DRFS does not account for events of local or contralateral BC recurrence, as assessing the risk of CBC in the case of CRRM is biased by missing the organ at risk, as discussed in a large Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results study [64]. While a meta-analysis has examined the association between BRCA status and distant metastasis-free survival, an outcome equivalent to our primary outcome, the studies included in the distant metastasis-free survival analysis reported distant disease-free survival, which also accounts for the time to other non-breast, mainly ovarian cancers [21]. One limitation of our study is that, despite extensive data integration, not all participants had systematic follow-up at hospital departments reporting to DBCG. This could potentially bias the prolonged follow-up time for patients who were alive and event-free. Another limitation is the inclusion of patients with pathogenic variants in other high-risk genes as BRCAwt, which might attenuate the results for this patient group. The median OS was not reached during the follow-up, which might account for the non-significant survival differences between BRCApv and BRCAwt [65]. Lastly, patients in our cohort were selected for germline BRCA testing, and this selection may, at least in part, explain the benefit of CRRM in BRCAwt as well as BRCApv carriers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, BRCApv status was associated with significantly worse DRFS (HR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.06–1.63, p = 0.01) but not with OS (HR = 1.25, 95% CI 0.98–1.58, p = 0.07). CRRM was associated with survival benefits mainly among BRCApv carriers and regardless of the age at diagnosis, while RRBSO was primarily effective in BRCApv carriers over 50 years of age at BC diagnosis, presumably reflecting a reduction in the risk of OC. BRCA2pv status was linked to delayed testing and lower CRRM and adjuvant chemotherapy rates; however, in the adjusted analysis, BRCA2pv outcomes were not significantly worse compared to BRCA1pv. Our results highlight the importance of prompt BRCA testing for women with BC, irrespective of age and hormone receptor status, to identify BRCApv carriers and enable timely RRS and targeted systemic treatment [61, 66].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- BC

Breast cancer

- BRCApv

Pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes

- BRCAwt

Wild-type BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes

- CBC

Contralateral breast cancer

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRRM

Contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy

- CT

Chemotherapy

- DBCG

Danish breast cancer cooperative group

- DMFS

Distant metastasis-free survival

- DRFS

Distant recurrence-free survival

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- ET

Endocrine therapy

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LN

Lymph nodes

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OC

Ovarian cancer

- OS

Overall survival

- PBC

Primary breast cancer

- RRBSO

Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- RRS

Risk-reducing surgery

- RT

Radiotherapy

Author contributions

AK, AL, MJ, BE, MT, and MR: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, validation, and writing of the original draft; AK and MJ: statistical analysis; IP, AP, LL and KW: data resources, review and final draft editing; LCBA and MM: conceptualization, methodology, and final draft review; AL: project administration.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Zealand Region. The Danish Cancer Society, Region Zealand and Region of Southern Denmark Research Foundation, Karen A. Tolstrup Foundation, Holms Mindelegat, and Astrid Thaysen Foundation funded the study. This study was supported by AstraZeneca and Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, who are codeveloping Olaparib.

Data availability

The findings of this study are supported by data which can be provided upon request and approval from the Danish Breast Cancer Group. Data may not be publicly available due to institutional restrictions and by the Danish Health Law.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

AK and AL: Institutional grants from AstraZeneca. Personal grants (presentation): AstraZeneca; AVL: Advisory board: MSD, congress attendance support: Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca; MJ: Meeting expenses and advisory board, Novartis; BE: institutional grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; grants for attending scientific meetings from MSD and Daiichi Sankyo; advisory board member organized by Eli Lilly and Medac. IP: Personal grant (presentation): AstraZeneca. KW: Personal grant (presentation), Seagen Denmark ApS. LCBA and MM are employees of AstraZeneca and hold shares; MT, CMR, and LL report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the board of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, the Capital Region’s Center for Health (R-21061634), and the Zealand University Hospital’s Administration Board (EMN-2021–09331). The study is registered at the Capital Region Research Overview – PACTIUS (J.nr. P-2021–0729) and adheres to the General Data Protection Regulations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Larsen MJ, Thomassen M, Gerdes A-M, Kruse TA (2014) Hereditary breast cancer: clinical, pathological and molecular characteristics. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 8:145–155. 10.4137/BCBCR.S18715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Phillips K-A, Mooij TM, Roos-Blom M-J et al (2017) Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA 317(23):2402–2416. 10.1001/jama.2017.7112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Kolk DM, de Bock GH, Leegte BK, Schaapveld M, Mourits MJE, de Vries J et al (2010) Penetrance of breast cancer, ovarian cancer and contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 families: high cancer incidence at older age. Breast Cancer Res Treat 124(3):643–651. 10.1007/s10549-010-0805-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sessa C, Balmaña J, Bober SL, Cardoso MJ, Colombo N, Curigliano G et al (2023) Risk reduction and screening of cancer in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guideline. Ann Oncol 34(1):33–47. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbine NE, Lostumbo L, Wallace J, Ko H (2018) Risk-reducing mastectomy for the prevention of primary breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4(4):CD002748. 10.1002/14651858.CD002748.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, You R, Wang X, Liu C, Xu Z, Zhou J et al (2016) Effectiveness of prophylactic surgeries in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Cancer Res 22(15):3971–3981. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metcalfe KA, Eisen A, Poll A, Candib A, McCready D, Cil T et al (2021) Frequency of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in breast cancer patients with a negative BRCA1 and BRCA2 rapid genetic test result. Ann Surg Oncol 28(9):4967–4973. 10.1245/s10434-021-09855-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong J, Lynch K, Virgo KS, Schwartz MD, Friedman S, Dean M et al (2021) Utilization, timing, and outcomes of BRCA genetic testing among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer from a national commercially insured population: the ABOARD study. JCO Oncol Pract 17(2):e226–e235. 10.1200/OP.20.00571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heemskerk-Gerritsen BAM, Rookus MA, Aalfs CM, Ausems MGEM, Collée JM, Jansen L et al (2015) Improved overall survival after contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with a history of unilateral breast cancer: a prospective analysis. Int J Cancer 136(3):668–677. 10.1002/ijc.29032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruper L, Kauffmann RM, Smith DD, Nelson RA (2014) Survival analysis of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a question of selection bias. Ann Surg Oncol 21(11):3448–3456. 10.1245/s10434-014-3930-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg SM, Dominici LS, Gelber S, Poorvu PD, Ruddy KJ, Wong JS et al (2020) Association of breast cancer surgery with quality of life and psychosocial well-being in young breast cancer survivors. JAMA Surg 155(11):1035–1042. 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson SE, Lei X, Roubaud MS, DeSnyder SM, Caudle AS, Shaitelman SF et al (2022) Long-term quality of life in patients with breast cancer after breast conservation vs mastectomy and reconstruction. JAMA Surg 157(6):e220631. 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.0631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luque Suarez S, Olivares Crespo ME, Brenes Sanchez JM, de la Herrera MM (2024) Immediate psychological implications of risk-reducing mastectomies in women with increased risk of breast cancer: a comparative study. Clin Breast Cancer 24(7):620–629. 10.1016/j.clbc.2024.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz SJ, Kurian AW, Morrow M (2015) Treatment decision making and genetic testing for breast cancer: mainstreaming mutations. JAMA 314(10):997–998. 10.1001/jama.2015.8088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grindedal EM, Jørgensen K, Olsson P, Gravdehaug B, Lurås H, Schlichting E et al (2020) Mainstreamed genetic testing of breast cancer patients in two hospitals in South Eastern Norway. Fam Cancer 19(2):133–142. 10.1007/s10689-020-00160-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kemp Z, Turnbull A, Yost S, Seal S, Mahamdallie S, Poyastro-Pearson E et al (2019) Evaluation of cancer-based criteria for use in mainstream BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing in patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2(5):e194428. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bedrosian I, Somerfield MR, Achatz MI, Boughey JC, Curigliano G, Friedman S et al (2024) Germline testing in patients with breast cancer: ASCO-Society of Surgical Oncology guideline. J Clin Oncol 42(5):584–604. 10.1200/JCO.23.02225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Sprundel TC, Schmidt MK, Rookus MA, Brohet R, van Asperen CJ, Rutgers EJT et al (2005) Risk reduction of contralateral breast cancer and survival after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Br J Cancer 93(3):287–292. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt MK, van den Broek AJ, Tollenaar RAEM, Smit VTHBM, Westenend PJ, Brinkhuis M et al (2017) Breast cancer survival of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers in a hospital-based cohort of young women. J Natl Cancer Inst 109(8):djw329. 10.1093/jnci/djw329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antunes Meireles P, Fragoso S, Duarte T, Santos S, Bexiga C, Nejo P et al (2023) Comparing prognosis for BRCA1, BRCA2, and non-BRCA breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 15(23):5699. 10.3390/cancers15235699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu M, Xie F, Liu M, Zhang Y, Wang S (2021) Association between BRCA mutational status and survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 186(3):591–605. 10.1007/s10549-021-06104-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cronin-Fenton DP, Kjærsgaard A, Nørgaard M, Pedersen IS, Thomassen M, Kaye JA et al (2017) Clinical outcomes of female breast cancer according to BRCA mutation status. Cancer Epidemiol 49:128–137. 10.1016/j.canep.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baretta Z, Mocellin S, Goldin E, Olopade OI, Huo D (2016) Effect of BRCA germline mutations on breast cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 95(40):e4975. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurian AW, Ward KC, Abrahamse P, Bondarenko I, Hamilton AS, Deapen D et al (2021) Time trends in receipt of germline genetic testing and results for women diagnosed with breast cancer or ovarian cancer, 2012–2019. J Clin Oncol 39(15):1631–1640. 10.1200/JCO.20.02785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans DG, Phillips K-A, Milne RL, Fruscio R, Cybulski C, Gronwald J et al (2021) Survival from breast cancer in women with a BRCA2 mutation by treatment. Br J Cancer 124(9):1524–1532. 10.1038/s41416-020-01164-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambertini M, Ceppi M, Hamy AS, Caron O, Poorvu PD, Carrasco E et al (2021) Clinical behavior and outcomes of breast cancer in young women with germline BRCA pathogenic variants. NPJ Breast Cancer 7(1):16. 10.1038/s41523-021-00224-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurian AW, Abrahamse P, Bondarenko I, Hamilton AS, Deapen D, Gomez SL et al (2022) Association of genetic testing results with mortality among women with breast cancer or ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 114(2):245–253. 10.1093/jnci/djab151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Broek AJ, van’t Veer LJ, Hooning MJ, Cornelissen S, Broeks A, Rutgers EJ et al (2016) Impact of age at primary breast cancer on contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol 34(5):409–418. 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang Y-K, Kwong A (2022) Does genetic testing have any role for elderly breast cancer patients? A narrative review. Ann Breast Surg 6:34. 10.21037/abs-21-122 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurian AW, Bernhisel R, Larson K, Caswell-Jin JL, Shadyab AH, Ochs-Balcom H et al (2020) Prevalence of pathogenic variants in cancer susceptibility genes among women with postmenopausal breast cancer. JAMA 323(10):995–997. 10.1001/jama.2020.0229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christiansen P, Ejlertsen B, Jensen M-B, Mouridsen H (2016) Danish breast cancer cooperative group. Clin Epidemiol 8:445–449. 10.2147/CLEP.S99457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjerregaard B, Larsen OB (2011) The Danish pathology register. Scand J Public Health 39(7 Suppl.):72–74. 10.1177/1403494810393563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT (2015) The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 7:449–490. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostov AM, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, Thomassen M, Rossing CM, Pedersen IS et al (2025) Germline BRCA testing in Denmark following invasive breast cancer: progress since 2000. Acta Oncol 64:147–155. 10.2340/1651-226X.2025.42418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J et al (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17(5):405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spurdle AB, Healey S, Devereau A, Hogervorst FBL, Monteiro ANA, Nathanson KL et al (2012) ENIGMA–evidence-based network for the interpretation of germline mutant alleles: an international initiative to evaluate risk and clinical significance associated with sequence variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum Mutat 33(1):2–7. 10.1002/humu.21628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tolaney SM, Garrett-Mayer E, White J, Blinder VS, Foster JC, Amiri-Kordestani L et al (2021) Updated standardized definitions for efficacy end points (STEEP) in adjuvant breast cancer clinical trials: STEEP version 2.0. J Clin Oncol 39(24):2720–2731. 10.1200/JCO.20.03613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy BL, Yi M, Arun BK, Gutierrez Barrera AM, Bedrosian I (2020) Contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy in breast cancer patients who undergo multigene panel testing. Ann Surg Oncol 27(12):4613–4621. 10.1245/s10434-020-08889-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teoh V, Tasoulis M-K, Gui G (2020) Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer who are genetic carriers, have a strong family history or are just young at presentation. Cancers 12(1):140. 10.3390/cancers12010140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt MK, Kelly JE, Brédart A, Cameron DA, Boniface Jd, Easton DF et al (2023) EBCC-13 manifesto: balancing pros and cons for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Eur J Cancer 181:79–91. 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun J, Chu F, Pan J, Zhang Y, Yao L, Chen J et al (2023) BRCA-CRisk: a contralateral breast cancer risk prediction model for BRCA carriers. J Clin Oncol 41(5):991–999. 10.1200/JCO.22.00833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giardiello D, Hooning MJ, Hauptmann M, Keeman R, Heemskerk-Gerritsen BAM, Becher H et al (2022) PredictCBC-2.0: a contralateral breast cancer risk prediction model developed and validated in ~ 200,000 patients. Breast Cancer Res 24(1):69. 10.1186/s13058-022-01567-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mbuya-Bienge C, Pashayan N, Kazemali CD, Lapointe J, Simard J, Nabi H (2023) A systematic review and critical assessment of breast cancer risk prediction tools incorporating a polygenic risk score for the general population. Cancers 15(22):5380. 10.3390/cancers15225380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, Evans DG, Lynch HT, Isaacs C et al (2010) Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA 304(9):967–975. 10.1001/jama.2010.1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans DGR, Ingham SL, Baildam A, Ross GL, Lalloo F, Buchan I et al (2013) Contralateral mastectomy improves survival in women with BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 140(1):135–142. 10.1007/s10549-013-2583-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao Y-L, Wang K, Liu Q, Li J, Zhang X, Li H-Y (2019) Risk reduction and survival benefit of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in hereditary breast cancer: meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Breast Cancer 19(1):e48–e65. 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bedrosian I, Hu C-Y, Chang GJ (2010) Population-based study of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and survival outcomes of breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 102(6):401–409. 10.1093/jnci/djq018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metcalfe KA, Eisen A, Poll A, Candib A, McCready D, Cil T et al (2021) Rapid genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations at the time of breast cancer diagnosis: an observational study. Ann Surg Oncol 28(4):2219–2226. 10.1245/s10434-020-09160-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wevers MR, Schmidt MK, Engelhardt EG, Verhoef S, Hooning MJ, Kriege M et al (2015) Timing of risk reducing mastectomy in breast cancer patients carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation: retrospective data from the Dutch HEBON study. Fam Cancer 14(3):355–363. 10.1007/s10689-015-9788-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metcalfe K, Gershman S, Ghadirian P, Lynch HT, Snyder C, Tung N et al (2014) Contralateral mastectomy and survival after breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: retrospective analysis. BMJ 348:g226. 10.1136/bmj.g226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Metcalfe K, Lynch HT, Foulkes WD, Tung N, Kim-Sing C, Olopade OI et al (2015) Effect of oophorectomy on survival after breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA Oncol 1(3):306–313. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eleje GU, Eke AC, Ezebialu IU, Ikechebelu JI, Ugwu EO, Okonkwo OO (2018) Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD012464. 10.1002/14651858.CD012464.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Breast Cancer Association Consortium (2021) Breast cancer risk genes—association analysis in more than 113,000 women. N Engl J Med 384(5):428–439. 10.1056/NEJMoa1913948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Terkelsen T, Rønning H, Skytte A-B (2020) Impact of genetic counseling on the uptake of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among younger women with breast cancer. Acta Oncol 59(1):60–65. 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1648860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poggio F, Bruzzone M, Ceppi M, Pondé NF, La Valle G, Del Mastro L et al (2018) Platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 29(7):1497–1508. 10.1093/annonc/mdy127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW (2012) Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 134(2):459–478. 10.1007/s10549-012-2114-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olafsdottir EJ, Borg A, Jensen M-B, Gerdes A-M, Johansson ALV, Barkardottir RB et al (2020) Breast cancer survival in Nordic BRCA2 mutation carriers—unconventional association with oestrogen receptor status. Br J Cancer 123(11):1608–1615. 10.1038/s41416-020-01056-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vocka M, Zimovjanova M, Bielcikova Z, Tesarova P, Petruzelka L, Mateju M et al (2019) Estrogen receptor status oppositely modifies breast cancer prognosis in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers versus non-carriers. Cancers 11(6):738. 10.3390/cancers11060738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Partridge AH, Hughes ME, Warner ET, Ottesen RA, Wong Y-N, Edge SB et al (2016) Subtype-dependent relationship between young age at diagnosis and breast cancer survival. J Clin Oncol 34(27):3308–3314. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.8013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elliott MJ, Cescon DW (2021) Development of novel agents for the treatment of early estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Breast 62(Suppl. 1):S34–S42. 10.1016/j.breast.2021.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garber JO (2024) A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adjuvant olaparib after (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy in patients w/ germline BRCA1 & BRCA2 pathogenic variants & highrisk HER2-negative primary breast cancer: longerterm follow: Abstract Number: SESS-1568. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2024. https://sabcs.org/Portals/0/Documents/Embargoed/GS1-09%20Embargoed.pdf?ver=QzmPFwjedZIaUkgY_OS0Jw%3D%3D

- 62.Klaren HM, van’t Veer LJ, van Leeuwen FE, Rookus MA (2003) Potential for bias in studies on efficacy of prophylactic surgery for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation. J Natl Cancer Inst 95(13):941–947. 10.1093/jnci/95.13.941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Copson ER, Maishman TC, Tapper WJ, Cutress RI, Greville-Heygate S, Altman DG et al (2018) Germline BRCA mutation and outcome in young-onset breast cancer (POSH): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 19(2):169–180. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30891-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giannakeas V, Lim DW, Narod SA (2021) The risk of contralateral breast cancer: a SEER-based analysis. Br J Cancer 125(4):601–610. 10.1038/s41416-021-01417-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez LR, Gormley NJ, Lu R, Amatya AK, Demetri GD, Flaherty KT et al (2024) Improving collection and analysis of overall survival data. Clin Cancer Res 30(18):3974–3982. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-24-0919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Geyer CE, Garber JE, Gelber RD, Yothers G, Taboada M, Ross L et al (2022) Overall survival in the OlympiA phase III trial of adjuvant olaparib in patients with germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1/2 and high-risk, early breast cancer. Ann Oncol 33(12):1250–1268. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.09.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The findings of this study are supported by data which can be provided upon request and approval from the Danish Breast Cancer Group. Data may not be publicly available due to institutional restrictions and by the Danish Health Law.