Abstract

Poor dietary habits are a major contributor to chronic disease burden, yet nutrition counseling remains underutilized in primary care settings despite proven effectiveness. This article presents a novel adaptation of the 5 A’s framework (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) titled ‘The 5 A’s Approach to Promoting Nutrition Counseling in Primary Care’, by incorporating validated assessment tools and evidence-based strategies to support implementation in clinical settings. To address practical challenges, implementation approaches are proposed including alternative delivery and payment models. The 5 A’s adaptation can be a tool used to address the critical need for standardized nutrition counseling in primary care.

Keywords: diet, prevention, nutrition counseling, chronic diseases, primary care

Introduction

Poor dietary habits are the leading modifiable risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases.1,2 In the U.S., poor diet contributes to almost half of all cardiometabolic deaths. 3 Nutrition counseling in primary care settings has been shown to effectively improve diet quality, diabetes management, weight loss, and limit gestational weight gain.4,5 However, it occurs in only about one-third of all primary care office visits. 6 Physicians face barriers to nutrition counseling, including time constraints, financial disincentives, and uncertainty of effectiveness.6,7

Patients also face challenges including limited accessibility to fresh foods, insufficient meal preparation time, financial constraints, and limited culinary and nutrition knowledge. 8 Patients do have an interest in nutrition resources such as discounts at grocery stores, sample meal plans, and better guides on healthy recipes. 8 These needs align with physician-reported barriers—in a survey of internal medicine interns, 92% agreed specific dietary advice could help patients improve eating habits, though 86% felt they had insufficient nutrition training. 9 To help address these challenges, promising strategies include targeted continuing education based on newly developed nutrition competencies in medical training, 10 collaboration with Registered Dietitians (RDs), and interventions such as 5 A’s.

The 5 A’s

The 5 A’s framework (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) has the highest empirical support by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended lifestyle prevention strategies and is the national-level model adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for behavioral counseling.11 -15 This structured approach guides clinicians through 5 steps: (1) Assess health risks and behaviors, (2) Advise on behavior changes needed, (3) Agree on specific goals through collaborative decision-making, (4) Assist with skills and resources to achieve goals, and (5) Arrange follow-up support and referrals. 11 Evidence indicates that each component contributes uniquely to behavior change.

When physicians provide ‘Advice’ about weight loss, patients show increased motivation to improve their diet and lose weight. 16 ‘Assess’ improves patient confidence to lose weight when implemented. 16 ‘Assist’ leads to measurable improvements in dietary behaviors, while ‘Arrange’ is associated with both improved dietary fat intake and weight loss. 16 For every additional 5 A’s practice employed, patients express a higher motivation to lose weight and increased intention to improve dietary habits. 14 Notably, the greatest benefits occur when all 5 components are collectively implemented.15,17

Studies support a team-based approach to the 5A’s, where components can be distributed among various healthcare providers such as nurses, RDs, health coaches, and more.12,18 -20 Behavioral counseling interventions with similar principles to the 5 A’s have established sustained benefits, with improvements in blood pressure (BP), lipid levels, and adiposity measures at 12 to 24 months, and reduced cardiovascular events over 1 to 16 years. 12

Assess

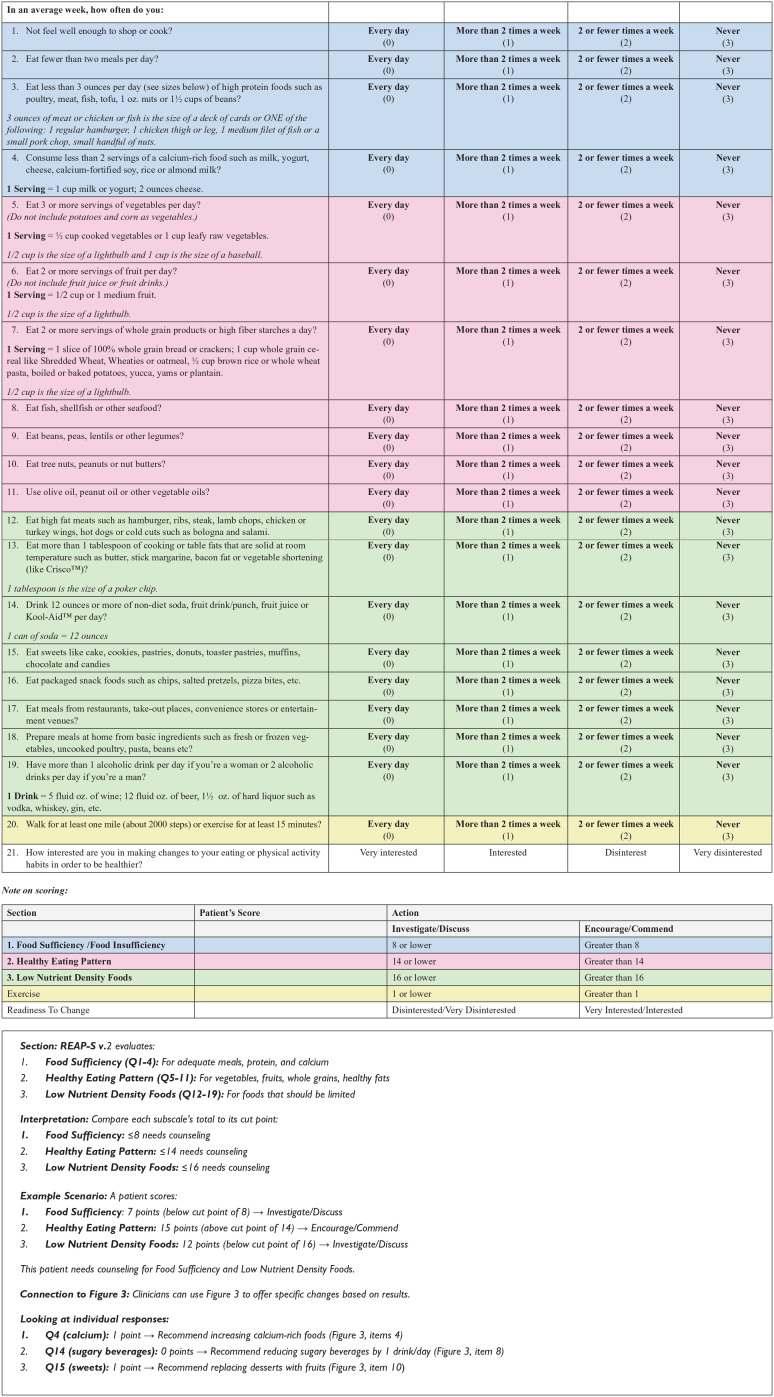

In ‘Assess’, a provider evaluates behavioral health risks related to nutrition (Figure 1).15 -17 To standardize this component, clinicians can use the Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants-shortened version, (REAP-S v.2), 21 an American Heart Association (AHA) recommended dietary screener. 22

Figure 1.

The 5 A’s approach to promoting nutrition counseling in primary care (flowchart with all 5 components, actions, and scripts). 15

This 21-question tool is organized into 3 main dietary subscales to identify patients needing counseling, as detailed in Figure 2. REAP-S v.2 demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .71) and validity through factor analysis and food record comparisons. 21 Before administering REAP-S v.2, providers should screen for contraindications (eg, active eating disorders, pregnancy, or cancer) and make referrals to appropriate specialists. 23

Figure 2.

REAP-S v.2 (rapid eating assessment for PARTICIPANTS, Shortened version, v.2). 21

For optimal clinical workflow, REAP-S v.2 can be integrated into Electronic Medical Record platforms like EPIC with automatic scoring functionality. 21 Ideally, patients would complete REAP-S electronically before visits, allowing providers to efficiently review in 1 to 2 min. 21 ‘Assess’, is supported by evidence that patients who are informed about their health status are 9 times more likely to perceive it as harmful to their health, 15 serving as a potential catalyst for behavior change.

Advise

In ‘Advise’, providers offer personalized dietary recommendations based on ‘Assess’ results (Figure 1).15 -17 Clinicians can utilize the ‘Reasonable Target Changes’ and ‘Realistic Small Substitutions’ (Figure 3) to guide patients toward dietary goals that align with REAP-S.24,25 Figure 3 includes evidence-based guidelines from the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) Scientific report, AHA recommendations, and the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR).26 -28 While ‘Advise’ typically takes 3 min, 14 the comprehensive nature of REAP-S may require 5 to 7 min.

Figure 3.

Reasonable target changes, small substitutions, and cultural adaptations for dietary counseling.24 -28,34

Abbreviations: Increase (↑) Decrease (↓)

To address time constraints, physicians could focus on 1 to 2 priority dietary areas with substantial health impacts (eg, sugar-sweetened beverages) and: (1) delegate detailed dietary counseling to specialized team members including RDs, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, health educators, or trained medical assistants using standardized protocols, (2) refer to RDs for counseling, 23 or (3) provide patients with take-home educational materials to review between visits.

Agree

In ‘Agree’, providers collaborate to select treatment goals based on the patient’s willingness to change (Figure 1).15 -17 After the ‘Advise’ stage, they ask if the suggested changes are realistic and achievable, then propose a specific goal based on the patient’s response.15 -17 Both ‘Agree’ and ‘Assist’ usually require 5 min to complete. 14

Assist

In ‘Assist’, patients receive self-help materials to support goals (Figure 1). This component is ideally implemented by team members such as medical assistants, nurses, health educators, or RDs.16,19-20 While physicians typically excel at ‘Assess’ and ‘Advise’, ‘Assist’, which is associated with behavior change, is suitable for delegation to other healthcare team members.18 -20

This team-based approach addresses a current implementation gap, as studies show that ‘Assist’ is provided in only 13% to 39% of encounters despite its importance for behavior change. 15 Practices can develop standardized workflows where support staff provide pre-selected evidence-based educational resources such as the We Can! Initiative, which includes nutrition guides, portion references, shopping and budgeting tips, and culturally-tailored recipes. 29

Arrange

In ‘Arrange’, providers schedule follow-ups and make referrals to RDs for patients requiring more intensive nutritional support as needed (Figure 1).15 -17 This normally takes 2 min. 14 Currently, Medicare covers Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT) for diabetes and kidney disease but not for dyslipidemia and other cardiometabolic risk factors. 30

Major medical organizations, including the AHA and American Diabetes Association (ADA), do recommend referrals to RDs for treatment of dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, hyperglycemia, and type 2 diabetes. 30 Research shows that ‘Arrange’ is rarely implemented (0%-10% of encounters) despite being 1 of the 2 most valued components by patients (along with ‘Assist’), 15 highlighting the importance of systematizing this component.

The 5 A’s as a Potential Solution

Our adaptation of the 5 A’s for nutrition counseling represents a novel application that addresses key barriers: (1) it standardizes ‘Assess’ via REAP-S v.2 that can be completed before visits and integrated into EMR; (2) it incorporates evidence-based dietary modification strategies with guidance; and (3) it integrates readily accessible educational resources addressing patient needs. Another strength of our approach is its flexibility in implementation.

Evidence supports implementation by non-physician team members and various delivery methods,12,18 -20 optimizing resource utilization while maintaining effectiveness. For example, the Goals for Eating and Moving (GEM) study leveraged physicians to endorse patient goals in <5 min (similar to our ‘Advise’), while health coaches handled the time-intensive ‘Agree’, ‘Assist’, and ‘Arrange’ components through counseling sessions and follow-up calls. 20 GEM aligns with our proposed workflow where physicians focus on priority dietary areas while team members manage other components.

Similarly, the Peer-Assisted Lifestyle (PAL) intervention effectively used peer coaches with the 5 A’s framework to deliver weight management counseling through in-person visits plus 12 scheduled telephone calls. 19 The PAL remote delivery approach achieved clinically significant body mass loss by minimizing travel barriers and accommodating veterans with lower incomes or those living in rural areas. 19

Cultural Considerations

While our framework estimates 18 to 21 min total, implementation time may vary significantly based on cultural and linguistic needs. The Diabetes Prevention Program sessions ranged from 30 to 60 min with 15- to 45-min maintenance sessions, 31 suggesting time allocation should be flexible, especially when language assistance is needed. For ‘Assess’, clinicians may consider using alternative validated tools such as the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS), which has been translated and used in Brazil, Germany, Spain, Israel, and many more settings.32,33

In ‘Advise’, dietary recommendations must be culturally tailored. The Puerto Rican Optimized Mediterranean-like Diet (PROMED) study showed successful cultural adaptation by replacing traditional Mediterranean foods with Puerto Rican alternatives. 34 PROMED can be similarly adapted for populations with shared food traditions centered around rice, beans, root vegetables, and tropical fruits, especially across Afro-Caribbean and Latino communities (Figure 3). 34

When implementing ‘Agree’ with Latino patients, emphasize family health to harness familismo—a cultural value prioritizing family-centered decisions that promotes well-being. 35 For Black patients, trust-building must precede goal-setting, acknowledging historical medical injustices (eg the Tuskegee Syphilis Study), are imperative given that 51% of Black Americans believe healthcare systems are designed against them. 36 When patients and clinicians form collaborative partnerships based on mutual respect and trust, patients become more engaged in their care, leading to better decision-making and adherence to their goals. 37

‘Assist’ requires culturally appropriate resources. Beyond the We Can! Initiative’s Spanish materials, 29 include resources reflecting specific food traditions. Apps like Lose It! (with customizable entries) and MyFitnessPal (with extensive international foods) can support diverse food tracking, 38 while traditional handwritten dietary logs serve communities with technological barriers, ensuring equitable implementation.

In ‘’Arrange’, Promoting Successful Weight Loss in Primary Care in Louisiana (PROPEL) shows effective culturally responsive follow-up systems.39,40 By embedding health coaches within clinics serving Black communities, this intervention ensured structured follow-up with high retention (83.4% completion rate), illustrating successful lifestyle interventions in real-world settings.39,40

Thus, various follow-up modalities (in-person, telephone, digital) should be available to accommodate cultural preferences and technological access. While cultural adaptations improve our framework’s relevance, economic considerations remain crucial for adoption.

Discussion

Economic Impact and Coverage Barriers

Nutrition counseling plays a vital role in disease prevention, but reimbursement barriers continue to limit its implementation. Suboptimal diet leads to $50.4 billion in annual US healthcare expenditure for cardiometabolic diseases. 41 Despite the high costs of diet-related diseases, only 21% of obesity visits include nutrition counseling, far below the 32.6% Healthy People 2030 target. 42 Insurance coverage for nutrition services varies widely by state, with only 26 Medicaid fee-for-service programs and 28 Medicaid managed-care programs covering nutrition counseling. 43

Evidence for Nutrition Interventions

An evidence report from USPSTF (113 RCTs, N = 129 993) found behavioral counseling improves BP (systolic: −0.80 mm Hg; diastolic: −0.42 mm Hg), LDL-C (−2.20 mg/dL), and BMI (−0.32). 44 Food is Medicine programs project $13.6 billion annual savings, 45 while MNT for dyslipidemia reduces total cholesterol (4.64-20.84 mg/dL), LDL-C (1.55-11.56 mg/dL), and triglycerides (15.9-32.55 mg/dL) with medication savings of $638 to 1450 per patient annually. 30

These nutrition interventions remain relevant even in the emerging glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) era. While GLP-1RAs produce significant weight loss, they are costly ($6500-$16 000 annually), have low long-term adherence (27% after 1 year), and are inaccessible. 46 Innovative approaches combining GLP-1RA therapy with nutritional interventions like the 5 A’s framework may provide more sustainable outcomes as an adjunct, especially given common weight regain after medication discontinuation. 46

Implementation Challenges

Implementation challenges include administrative buy-in, time constraints, workflow changes, and resource mobilization. 18 Attrition rates vary from 3.7% to 36.5%, highlighting the need for retention strategies. 18 Our framework requires approximately 18 to 21 min total, exceeding the average 18-min primary care visit. 47

Approaches to address time constraints include (1) pre-visit electronic REAP-S completion; (2) capitated models (which reduce incentives to minimize visit time)48,49; and (3) dividing the 5 A’s across multiple visits under CMS split-visit rules. 50 Under the split-visit approach, the initial visit focuses on ‘Assess’ using REAP-S, with the physician reviewing results and offering either a dedicated follow-up appointment to complete the remaining components, or a referral to an RD. 50 This approach complies with CMS regulations when the same practice completes all components, while RD referrals are processed as separate services. 50

Future Directions

Compelling evidence supports implementing on our adapted 5 A’s framework with further evaluation. Future implementation should consider focusing on 4 key areas. First, expanding provider training through brief modules (shown to significantly improve use of underutilized components with just 15 min of education) 17 to promote wider adoption. Second, developing and testing specialized workflows that strategically distribute components based on team members’ strengths—physicians leading ‘Assess/Advise’ while team members manage ‘Assist/Arrange’.

Third, evaluating technology integration for remote delivery, building on evidence showing equal effectiveness between in-person and digital interventions.18 -20 Research priorities should include measuring REAP-S v.2 EMR integration outcomes, analyzing cost-effectiveness across different practice settings, and conducting longitudinal studies to establish sustained benefits. Fourth, expanding cultural adaptations for diverse populations, following approaches like PROPEL (83.4% retention and −4.99% weight loss)39,40 by developing and validating population-specific implementation strategies.

Conclusion

‘The 5 A’s Approach to Promoting Nutrition Counseling in Primary Care’ provides a structured framework to standardize nutrition counseling with the potential to reduce diet-related chronic disease burden. This evidence-based approach could accelerate healthcare towards promoting preventive nutrition. While offering concrete tools, successful implementation requires broader systemic changes including dedicated funding, policy support, and alternative payment models. Such transformative initiatives may be necessary to address the significant burden of diet-related diseases and sustainably improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Walter C. Willett, MD, DrPH for guidance on implementation strategies and payment models; Rebecca Robbins, PhD, and Shilpa Bhupathiraju, PhD for feedback on drafts; Deniele DeGraff, MS RD for clinical nutrition expertise; Neal Peterson, MD and Rebecca Konkle, MD for clinical feedback on our adapted 5 A’s.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Farhad Mehrtash  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8779-4242

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8779-4242

Ethical Considerations: N/A.

Consent to Participate: None.

Consent for Publication: None.

Author Contributions: FM: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, figure development, and revision, original drafting, feedback integration, editing and review, submission coordination, and refinement of structure and clarity. JEM: Guidance on clinical implementation, team-based care, referral pathways, insurance coverage; editing and review; recommendations on evidence framing, REAP-S integration, and manuscript clarity and arrangement.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. JoAnn E. Manson receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health. No specific funding was received for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement: Data from the findings of the study are available within the sources cited.

References

- 1. Miller V, Micha R, Choi E, Karageorgou D, Webb P, Mozaffarian D. Evaluation of the quality of evidence of the association of foods and nutrients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146705. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 [published correction appears in Lancet. 2021;397(10293):2466. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01342-8]. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958-1972. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Micha R, Peñalvo JL, Cudhea F, Imamura F, Rehm CD, Mozaffarian D. Association between dietary factors and mortality from heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2017;317(9):912-924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell LJ, Ball LE, Ross LJ, Barnes KA, Williams LT. Effectiveness of dietetic consultations in primary health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(12):1941-1962. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.06.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Simões Corrêa Galendi J, Leite RGOF, Banzato LR, Nunes-Nogueira VDS. Effectiveness of strategies for nutritional therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):4243. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19074243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harkin N, Johnston E, Mathews T, et al. Physicians’ dietary knowledge, attitudes, and counseling practices: the experience of a single health care center at changing the landscape for dietary education. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018;13(3):292-300. doi: 10.1177/1559827618809934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vasiloglou MF, Fletcher J, Poulia KA. Challenges and perspectives in nutritional counselling and nursing: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1489. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Torna E, Fitzgerald JD, Nelson DS, et al. Perceptions, barriers, and strategies toward nutrition counseling in healthcare clinics: a survey among health care providers and adult patients. SN Compr Clin Med. 2021;3:145-157. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00674-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Findley T, McEnroe K, Babuch G, et al. Doctoring Our Diet II: Nutrition Education for Physicians is Overdue. Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eisenberg DM, Cole A, Maile EJ, et al. Proposed nutrition competencies for medical students and physician trainees: a consensus statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(9):e2435425. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.35425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral Counseling Interventions: An Evidence-based Approach. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. US Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324(20):2069-2075. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. How to Talk With Patients About Their Prediabetes Diagnosis. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schlair S, Moore S, McMacken M, Jay M. How to deliver high-quality obesity counseling in primary care using the 5As framework. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2012;19(5):221-229. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sherson EA, Yakes Jimenez E, Katalanos N. A review of the use of the 5 A’s model for weight loss counseling: differences between physician practice and patient demand. Fam Pract. 2014;31(4):389-398. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL, et al. Do the five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med. 2011;43(3):179-184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pollak KI, Tulsky JA, Bravender T, et al. Teaching primary care physicians the 5 A’s for discussing weight with overweight and obese adolescents. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(10):1620-1625. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shieh C, Hardin HK, Doerstler MD, Jacobsen AL. Integration of the 5A’s framework in research on obesity and weight counseling: systematic review of literature. Am J Lifestyle Med. Published online December 9, 2024. doi: 10.1177/15598276241306351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wittleder S, Smith S, Wang B, et al. Peer-Assisted Lifestyle (PAL) intervention: a protocol of a cluster-randomised controlled trial of a health-coaching intervention delivered by veteran peers to improve obesity treatment in primary care. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e043013. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mateo KF, Berner NB, Ricci NL, et al. Development of a 5As-based technology-assisted weight management intervention for veterans in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2834-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shankar V, Thompson KH, Wylie-Rosett J, Segal-Isaacson CJ. Validation and reliability for the updated REAP-S dietary screener, (Rapid Eating Assessment of Participants, Short Version, v.2). BMC Nutr. 2023;9(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s40795-023-00747-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vadiveloo M, Lichtenstein AH, Anderson C, et al. Rapid diet assessment screening tools for cardiovascular disease risk reduction across healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(9):e000094. doi: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morgan-Bathke M, Raynor HA, Baxter SD, et al. Medical nutrition therapy interventions provided by dietitians for adult overweight and obesity management: an academy of nutrition and dietetics evidence-based practice guideline. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2023;123(3):520-545.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2022.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mozaffarian D, Capewell S. United Nations’ dietary policies to prevent cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 2011;343:d5747. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kahan S, Manson JE. Nutrition counseling in clinical practice: how clinicians can do better. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1101-1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and Secretary of Agriculture. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Heart Association. Get to Know Grains: Why You Need Them, and What to Look For. American Heart Association; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 28. American Institute for Cancer Research. Recommendation: Limit Consumption of Red and Processed Meat. American Institute for Cancer Research; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Nutrition Tools and Resources. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sikand G, Handu D, Rozga M, de Waal D, Wong ND. Medical nutrition therapy provided by dietitians is effective and saves healthcare costs in the management of adults with dyslipidemia. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023;25(6):331-342. doi: 10.1007/s11883-023-01096-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165-2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. García-Conesa MT, Philippou E, Pafilas C, et al. Exploring the validity of the 14-item mediterranean diet adherence screener (MEDAS): a cross-national study in seven European Countries around the mediterranean region. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):2960. doi: 10.3390/nu12102960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vieira LM, Gottschall CBA, Vinholes DB, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Marcadenti A. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of 14-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener and low-fat diet adherence questionnaire. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;39:180-189. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mattei J, Díaz-Alvarez CB, Alfonso C, et al. Design and implementation of a culturally-tailored randomized pilot trial: Puerto Rican optimized mediterranean-like diet. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022;7(1):100022. doi: 10.1016/j.cdnut.2022.100022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ayón C, Marsiglia FF, Bermudez-Parsai M. Latino family mental health: exploring the role of discrimination and familismo. J Community Psychol. 2010;38(6):742-756. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pew Research Center. Most Black Americans believe U.S. institutions were designed to hold Black people back. Published June 14, 2024. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://www.pewresearch.org

- 37. Krist AH, Tong ST, Aycock RA, Longo DR. Engaging patients in decision-making and behavior change to promote prevention. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;240:284-302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patel ML, Wakayama LN, Bennett GG. Self-monitoring via digital health in weight loss interventions: a systematic review among adults with overweight or obesity. Obesity. 2021;29(3):478-499. doi: 10.1002/oby.23088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katzmarzyk PT, Martin CK, Newton RL, Jr, et al. Weight loss in underserved patients: a cluster-randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):909-918. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Höchsmann C, Dorling JL, Martin CK, et al. Effects of a 2-year primary care lifestyle intervention on cardiometabolic risk factors: a cluster-randomized trial. Circulation. 2021;143(12):1202-1214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jardim TV, Mozaffarian D, Abrahams-Gessel S, et al. Cardiometabolic disease costs associated with suboptimal diet in the United States: a cost analysis based on a microsimulation model. PLoS Med. 2019;16(12):e1002981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). Increase the Proportion of Health Care Visits by Adults With Obesity That Include Counseling on Weight Loss, Nutrition, or Physical Activity — NWS-05: Data. Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP); 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stephenson J. Report finds large variation in states’ coverage for obesity treatments. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(3):e220608. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Patnode CD, Redmond N, Iacocca MO, Henninger M. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known cardiovascular disease risk factors: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(4):375-388. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.7408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mozaffarian D, Aspry KE, Garfield K, et al. “Food is medicine” strategies for nutrition security and cardiometabolic health equity: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(8):843-864. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mozaffarian D. GLP-1 Agonists for obesity-a new recipe for success? JAMA. 2024;331(12):1007-1008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Neprash HT, Mulcahy JF, Cross DA, Gaugler JE, Golberstein E, Ganguli I. Association of primary care visit length with potentially inappropriate prescribing. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(3):e230052. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morenz AM, Zhou L, Wong ES, Liao JM. Association between capitated payments and preventive care among U.S. Adults. AJPM Focus. 2023;2(3):100116. doi: 10.1016/j.focus.2023.100116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Park B, Gold SB, Bazemore A, Liaw W. How evolving united states payment models influence primary care and its impact on the quadruple aim. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(4):588-604. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.04.170388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. American College of Surgeons. Practice management: Reporting Split/Shared E/M Visits in 2024. American College of Surgeons; 2024. [Google Scholar]