Abstract

The low level of physical fitness among Chinese adolescents has a negative impact on schooling and health. The weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) has attracted much attention as a novel indicator for assessing body composition. However, little research has been conducted on the association between WWI and the physical fitness index (PFI) among adolescents in the Xinjiang region of western China. A randomized whole-cluster sampling method was used to assess 4496 adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China. The assessment indexes included height, weight, waist circumference, grip strength, sit-up, standing long jump, sit and reach, 50 m dash, 20-mSRT, and the WWI and PFI were calculated. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Kruskal Wallis rank sum test, Pearson correlation analysis, and curvilinear regression analysis were used to analyze the correlations that existed between WWI and PFI. The differences in PFI between different WWI subgroups of Chinese adolescents in Xinjiang were all statistically significant when compared with each other (H-values of 57.058, 137.515, and 19.443, P < 0.01). The analyzed results did not change according to age. Similarly, the same trend was observed for boys and girls. Overall, WWI showed an inverted “U” curve relationship with PFI, and the effect of increased WWI on PFI was more pronounced in boys than in girls. When the WWI is 8.8, the PFI is at its highest level, i.e. 0.131. The relationship between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents in Xinjiang showed an inverted “U” curve, with lower or higher WWI negatively affecting PFI, and the effect on boys was more obvious than that on girls. In the future, the WWI level of Chinese adolescents in Xinjiang should be effectively controlled to keep it within a reasonable range, promote the development of physical fitness, and safeguard physical and mental health.

Keywords: Adolescents, Associations, Physical fitness index, Weight-adjusted waist index, Xinjiang

Subject terms: Nutrition, Public health, Weight management

Introduction

The physical fitness index (PFI), as a comprehensive indicator of physical fitness, is important to health1. Multiple studies have shown that screen time and sedentary behaviors among adolescents have been lengthening in recent years, contributing to problems of overweight and obesity, which has led to a decline in fitness levels and a negative impact on health2,3. The study found that physical fitness declines by more than a quarter on average from age 11 to 14 in adolescents and continues to trend lower, with serious negative health consequences4. Research shows that cardiorespiratory fitness, a core element of physical fitness, is declining in adolescents, posing a serious threat to health5. A study in U.S. adolescents found that cardiorespiratory fitness, a key predictor of cardiovascular health, has shown a downward trend in the U.S. and internationally over the last 60 years or so. Similarly, muscle strength, an important indicator of physical fitness, has shown a downward trend in recent years, and low muscle fitness in adolescence leads to low muscle fitness in adulthood6. A study of physical fitness trends among Canadian adolescents found a trend toward a decline in grip strength among 11- to 19-year-olds7. PFI is gaining attention as a comprehensive indicator of physical fitness. A study of American adolescents confirmed that PFI is on a downward trend and that there is a strong correlation between PFI and the development of chronic cardiovascular disease8. China, also in an economically underdeveloped region, is no exception. A study of long-term trends among 12-year-olds in China between 1985 and 2014 showed a steady decline in physical fitness levels since 2000 for youth in both urban and rural areas9. A study of Chinese adolescents from 1985 to 2014 found that the PFI of Chinese adolescents showed a downward trend, and compared to 1985, the PFI of Chinese adolescents in 2014 decreased by 0.8, posing a serious threat to adolescent health10. It has also been shown that a decline in physical fitness leads to a higher risk of developing various chronic diseases. A study involving 4,484 Chinese university students found that each one-point increase in lung capacity and endurance running was associated with a 2.1% and 4.1% reduction in the risk of abnormal mental status, respectively11. A survey of 7,199 adolescents in China also showed that the higher the PFI, the lower the detection rate of psychological symptoms among adolescents12. This shows that there is also a close correlation between the decline in PFI and physical and mental health, which should be given sufficient attention. Another study on PFI and waist circumference indicators found that PFI and waist circumference showed an inverted U-shaped curve relationship13. However, past studies have mainly focused on the PFI of adults, and relatively few studies have been conducted on the PFI of adolescents. Meanwhile, few studies have been conducted on PFI in adolescents in remote areas of Xinjiang, China.PFI, as an important indicator of physical fitness, is affected by various factors, such as BMI, waist circumference, lifestyle, and dietary behaviors14,15.

The weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) as a novel indicator for evaluating body composition, has received extensive attention from scholars in recent years. Compared with BMI and waist circumference indicators, WWI has a more sensitive ability to recognize various health diseases16–18. A prospective cohort study in a Chinese population showed an association between WWI and all-cause and cardiovascular deaths, with higher levels of WWI associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular deaths19. Another study also found that WWI was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and that this association was more pronounced in the highest WWI category20. It has also been found that WWI has a better identification for evaluating diseases such as hypertension compared to waist circumference metrics21. A study of non-Asian populations in the United States found a U-shaped relationship between WWI and all-cause mortality in non-Asian populations, and that WWI was superior to BMI and waist circumference in predicting all-cause mortality22. A study of multiple metrics reflecting body composition found that WWI showed better discrimination and accuracy than other obesity metrics in predicting cardiovascular disease and nonaccidental deaths23. However, previous studies have found that most of the studies on WWI have focused on the relationship with a physical fitness indicator or a disease, while few studies have been conducted on the association relationship between WWI and a composite indicator. Therefore, the study of the association between WWI and PFI is of great practical significance and plays an important role in improving physical fitness in adolescents.

As an underdeveloped region in western China, Xinjiang is relatively backward in terms of its level of economic development24. In addition, Xinjiang has a large number of ethnic components and is a typical multi-ethnic settlement area, making it one of the typical ethnic regions in China. Past studies have not identified any research on the association between WWI and PFI conducted on adolescents in the Xinjiang region of China. For this reason, the present study assessed 4496 adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China, on relevant body morphology and physical fitness indexes, and calculated the levels of WWI and PFI, to better analyze the associations that exist between WWI and PFI. The aim was to provide references and suggestions for the intervention and improvement of PFI in adolescents in Xinjiang, China.

Methods

Participants

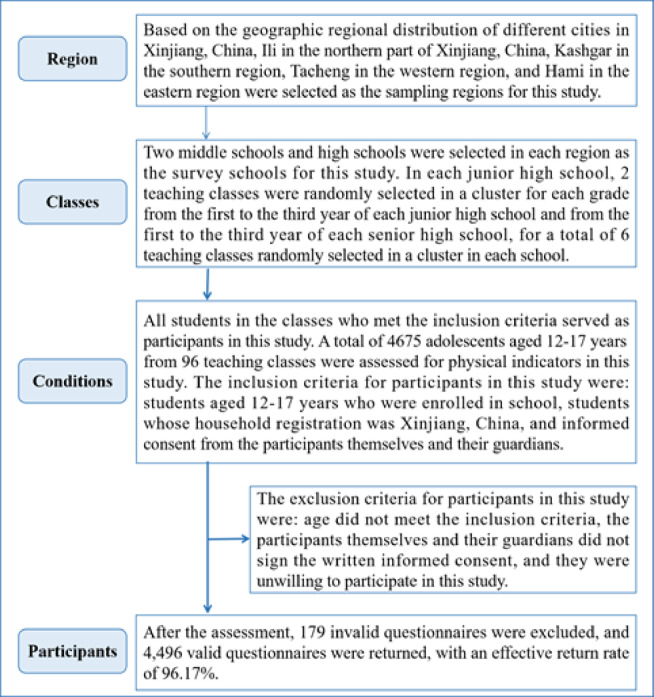

March to May 2024, a randomized whole-cluster sampling method was used to assess 4496 adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China, regarding physical indicators. The participant sampling process was categorized as follows: First, based on the geographic regional distribution of different cities in Xinjiang, China, Ili in the northern part of Xinjiang, China, Kashgar in the southern region, Tacheng in the western region, and Hami in the eastern region were selected as the sampling regions for this study. Second, two middle schools and high schools were selected in each region as the survey schools for this study. In each junior high school, 2 teaching classes were randomly selected in a cluster for each grade from the first to the third year of each junior high school and from the first to the third year of each senior high school, for a total of 6 teaching classes randomly selected in a cluster in each school. All students in the classes who met the inclusion criteria served as participants in this study. A total of 4675 adolescents aged 12–17 years from 96 teaching classes were assessed for physical indicators in this study. After the assessment, 179 invalid questionnaires were excluded. Of these, 23 were not signed by the subjects themselves or their guardians with written informed consent; 142 were missing key demographic information, and 14 had broken and missing questionnaires. 4,496 valid questionnaires were returned, with an effective return rate of 96.17%. The inclusion criteria for participants in this study were: students aged 12–17 years who were enrolled in school, students whose household registration was Xinjiang, China, and informed consent from the participants themselves and their guardians. The exclusion criteria for participants in this study were: age did not meet the inclusion criteria, the participants themselves and their guardians did not sign the written informed consent, and they were unwilling to participate in this study. The participant extraction process of this study is shown in (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

China Xinjiang adolescent participant extraction process.

This study was conducted by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians before the assessment of participants in this study, and participants volunteered to be assessed for this study. Approved by the Human Ethics Committee of East China Normal University (HR 475–2020).

Base situation

Information about the participants’ region, school, birthdate, class, ethnicity, and parents’ ethnicity was investigated to determine the age of the participants and whether they met the inclusion criteria for this study.

Weight-adjusted waist index (WWI)

The WWI is designed to more accurately reflect the relationship between abdominal fat and body weight. The WWI is calculated based on the assessment of weight and waist circumference. The formula is waist circumference (cm) divided by the square root of weight (kg). Weight and waist circumference were assessed according to the methods and instruments required by the China National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH)25. Participants were asked to empty their bowels and urine before weight assessment. Body weight was assessed using a Wanqing brand RGZ-160 scale. The weight was assessed to the nearest 0.1 kg. For the waist circumference assessment, participants were asked to wear light clothing as much as possible for the assessment. Waist circumference was assessed by staff of the same sex. Waist circumference was assessed using a nylon tape measure(CNSSCH Association, 2022). The results of the assessment were accurate to 0.1 centimeter.

Physical fitness index (PFI)

As a comprehensive indicator of physical fitness, PFI can comprehensively assess the physical fitness of adolescents. In this study, the PFI was standardized and summed from grip strength, sit-up, standing long jump, sit and reach 50 m dash, and 20-mSRT. Grip strength, sit-up, standing long jump, sit and reach, and 50 m dash were assessed according to the instruments and methods required by the CNSSCH25. The 20-mSRT was evaluated according to the evaluation methodology and instrumentation required by Cooper Laboratories in the United States26. The grip strength assessment was accurate to 0.1 kg, the standing long jump and sit and reach assessment was accurate to 0.1 cm, and the 50 m dash assessment was accurate to 0.01 s. The specific PFI was calculated as: PFI = Z grip strength+Z sit−up+Z standing long jump+Z sit and reach-Z 50 m dash+Z 20−mSRT.

Quality control

The staff involved in the assessment of this study were trained and assessed to perform the assessment. Staff members were asked to calibrate the instrument before each day’s assessment to guarantee the accuracy of the test. Participants were asked to do preparatory activities before the assessment to prevent sports injuries during the assessment. Participants were asked to wear sportswear for the assessment.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables in this study that conform to a normal distribution are expressed as mean and standard deviation. Continuous variables that do not conform to a normal distribution are expressed as medians. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Continuous variables were compared using one-way ANOVA and the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Correlation analysis between different physical fitness programs was analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis. The correlation between WWI and PFI was analyzed using curvilinear regression analysis. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software, with P < 0.01 as the two-sided test level.

Results

In this study, 4496 adolescents aged 12–17 years were assessed for WWI and various physical fitness, of whom 2140 (47.6%) were boys and 2356 (52.4%) were girls. The mean age of the participants was (14.67 ± 1.55) years. Table 1 shows the distribution of the specific number of participants in each age group from 12 to 17 years.

Table 1.

Distribution of youth aged 12–17 in Xinjiang, China.

| Age(years) | Boys | Girls | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 years | 135(39.9) | 203(60.1) | 338 |

| 13 years | 464(54.0) | 395(46.0) | 859 |

| 14 years | 493(51.8) | 459(48.2) | 952 |

| 15 years | 418(43.8) | 537(56.2) | 955 |

| 16 years | 277(47.0) | 312(53.0) | 589 |

| 17 years | 353(44.0) | 450(56.0) | 803 |

| 12–17 years | 2140(47.6) | 2356(52.4) | 4496 |

Overall the results showed that adolescents aged 12–17 years old in Xinjiang, China, in terms of height, weight, waist circumference, WWI, grip strength, sit-up, standing long jump, sit and reach, 50 m dash, and 20-mSRT indices were compared with each other The differences were statistically significant (F-values of 161.334, 196.908, 449.793, 309.459, 52.244, 142.55, 125.511, 57.858, 306.247, and 516.67, respectively, P < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference when compared in terms of PFI (H-value of 0.578, P > 0.05). A comparison of each physical fitness index in terms of different genders is shown in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of each physical fitness among adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China.

| N | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Waist circumference (cm) | WWI (cm/√kg) | Grip strength (kg) | Sit-up (n) | Standing long jump (cm) | Sit and reach (cm) | 50 m dash (s) | 20-mSRT (laps) | PFI [P50(P25,P75)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||||||||||

| 12–13 years | 599 | 166.48 ± 8.07 | 52.49 ± 10.49 | 65.42 ± 14.45 | 9.09 ± 1.80 | 40.36 ± 10.86 | 38.74 ± 11.41 | 190.31 ± 37.13 | 7.91 ± 8.92 | 8.70 ± 1.71 | 30.68 ± 11.08 | 0.50(−1.63,2.03) |

| 14–15 years | 911 | 170.16 ± 7.87 | 54.14 ± 9.51 | 57.80 ± 14.18 | 7.89 ± 1.86 | 40.34 ± 12.49 | 35.71 ± 12.32 | 200.09 ± 26.60 | 10.39 ± 7.76 | 7.65 ± 0.98 | 24.09 ± 9.21 | 0.00(−1.76,2.22) |

| 16–17 years | 630 | 175.73 ± 7.06 | 61.07 ± 8.75 | 71.35 ± 12.03 | 9.17 ± 1.55 | 39.23 ± 13.35 | 42.86 ± 10.07 | 214.79 ± 30.31 | 12.43 ± 9.85 | 7.64 ± 1.03 | 17.80 ± 5.28 | 0.09(−1.40,1.53) |

| F/H-value | 226.733 | 144.592 | 188.239 | 130.419 | 1.809 | 72.644 | 98.222 | 41.179 | 155.886 | 323.485 | 1.643 | |

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.164 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.440 | |

| Girls | ||||||||||||

| 12–13 years | 598 | 162.39 ± 5.65 | 46.44 ± 8.87 | 57.44 ± 11.20 | 8.49 ± 1.58 | 28.52 ± 7.72 | 30.21 ± 8.98 | 152.29 ± 32.09 | 9.80 ± 9.71 | 10.24 ± 2.42 | 23.82 ± 8.32 | −0.58(−1.85,1.90) |

| 14–15 years | 996 | 163.75 ± 5.58 | 48.90 ± 6.21 | 55.80 ± 11.81 | 8.00 ± 1.68 | 30.54 ± 10.71 | 28.89 ± 10.39 | 161.75 ± 22.34 | 11.70 ± 8.69 | 8.66 ± 1.14 | 22.10 ± 8.27 | −0.16(−1.75,1.52) |

| 16–17 years | 762 | 165.16 ± 7.02 | 52.18 ± 6.83 | 69.25 ± 11.24 | 9.63 ± 1.56 | 23.87 ± 9.63 | 35.50 ± 9.64 | 173.99 ± 23.47 | 13.01 ± 10.44 | 8.58 ± 1.32 | 15.90 ± 5.52 | −0.21(−1.74,1.20) |

| F/H-value | 34.84 | 110.364 | 326.525 | 221.205 | 104.572 | 103.409 | 124.458 | 18.977 | 223.706 | 224.307 | 0.496 | |

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.780 | |

| Total | ||||||||||||

| 12–13 years | 1197 | 164.44 ± 7.26 | 49.47 ± 10.17 | 61.43 ± 13.53 | 8.79 ± 1.72 | 34.44 ± 11.12 | 34.48 ± 11.11 | 171.32 ± 39.56 | 8.85 ± 9.37 | 9.47 ± 2.23 | 27.25 ± 10.38 | 0.00(−1.78,1.96) |

| 14–15 years | 1907 | 166.81 ± 7.49 | 51.40 ± 8.37 | 56.75 ± 13.03 | 7.95 ± 1.77 | 35.22 ± 12.58 | 32.15 ± 11.85 | 180.07 ± 31.07 | 11.08 ± 8.28 | 8.17 ± 1.18 | 23.05 ± 8.79 | −0.15(−1.76,1.79) |

| 16–17 years | 1392 | 169.95 ± 8.79 | 56.02 ± 8.93 | 70.20 ± 11.65 | 9.42 ± 1.57 | 30.82 ± 13.78 | 38.83 ± 10.49 | 192.46 ± 33.61 | 12.75 ± 10.17 | 8.15 ± 1.28 | 16.76 ± 5.49 | −0.09(−1.60,1.33) |

| F/H-value | 161.334 | 196.908 | 449.793 | 309.459 | 52.244 | 142.55 | 125.511 | 57.858 | 306.247 | 516.67 | 0.578 | |

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.749 | |

WWI weight-adjusted waist index; 20-mSRT 20-m shuttle run test, PFI physical fitness index.

Table 3 shows the Pearson correlation analysis of each physical fitness index among adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China. The results showed that there were significant correlations (P < 0.05) among the indicators of grip strength, sit-up, standing long jump, sit and reach, 50 m dash, 20-mSRT, and PFI in adolescents.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation analysis of various physical fitness indicators among adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China.

| Grip strength | Sit-up | Standing long jump | Sit and reach | 50 m dash | 20-mSRT | PFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grip strength | 1.000 | ||||||

| Sit-up | 0.295** | 1.000 | |||||

| Standing long jump | 0.415** | 0.437** | 1.000 | ||||

| Sit and reach | 0.050** | 0.076** | −0.001 | 1.000 | |||

| 50 m dash | −0.205** | −0.230** | −0.391** | 0.011 | 1.000 | ||

| 20-mSRT | 0.184** | −0.044** | 0.035* | −0.269** | 0.034* | 1.000 | |

| PFI | 0.470** | 0.486** | 0.0448** | 0.295** | −0.369** | 0.239** | 1.000 |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. 20-mSRT 20-m shuttle run test, PFI physical fitness index.

Table 4 shows the comparison of PFI among different WWI subgroups of adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China. Overall the results showed that the differences were statistically significant when comparing the PFI between different WWI subgroups (H-values of 57.058, 137.515, and 19.443, P < 0.01). The results did not change with age. The same trend was observed in boys and girls.

Table 4.

Comparison of PFI among different WWI subgroups among adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China.

| Age(yr) | WWI<20th (A) | 20th ≤ WWI<40th (B) | 40th ≤ WWI<60th (C) | 60th ≤ WWI<80th (D) | WWI ≥ 80th (E) | H-value | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P50(P25, P75) | N | P50(P25, P75) | N | P50(P25, P75) | N | P50(P25, P75) | N | P50(P25, P75) | |||

| Boys | ||||||||||||

| 12–13 years | 53 | −0.91(−4.55, 2.95) | 94 | 0.81(0.61, 1.99) | 185 | 1.38(−1.59, 2.31) | 126 | −0.02(−1.02, 2.03) | 141 | −0.48(−2.23, 0.82) | 27.553 | <0.001 |

| 14–15 years | 301 | −0.95(−1.59, 1.20) | 221 | −0.69(−3.16, 1.22) | 197 | 1.53(0.32, 2.30) | 102 | 0.93(−3.02, 3.90) | 90 | 0.21(−1.76, 1.94) | 85.888 | <0.001 |

| 16–17 years | 82 | 0.45(−1.83, 2.21) | 82 | −0.03(−0.60, 1.16) | 95 | 0.68(−1.06, 1.95) | 187 | 0.28(−1.18, 1.53) | 184 | −0.42(−1.84, 0.97) | 15.153 | 0.004 |

| Girls | ||||||||||||

| 12–13 years | 103 | −0.38(−1.35, 0.72) | 114 | 1.43(0.15, 2.13) | 193 | −1.51(−3.53, −0.3) | 131 | −0.59(−1.71, 1.85) | 57 | 1.90(−0.09, 1.90) | 115.204 | <0.001 |

| 14–15 years | 285 | −0.81(−3.69, 1.47) | 355 | −0.22(−1.22, 1.47) | 135 | 0.84(0.00, 2.59) | 104 | −0.53(−1.95, 1.49) | 117 | −0.13(−1.51, 1.53) | 72.976 | <0.001 |

| 16–17 years | 75 | 0.25(−1.21, 2.58) | 49 | 0.62(-1.09, 3.20) | 80 | 0.12(−1.93, 1.18) | 248 | −0.32(−1.74, 0.92) | 310 | −0.28(−1.82, 0.96) | 12.712 | 0.013 |

| Total | ||||||||||||

| 12–13 years | 156 | −0.46(−1.63, 1.11) | 208 | 1.27(0.15, 2.10) | 378 | −0.71(−2.82, 1.67) | 257 | −0.56(−1.71, 2.03) | 198 | 0.01(−1.61, 1.90) | 57.058 | <0.001 |

| 14–15 years | 586 | −0.95(−2.77, 1.22) | 576 | −0.22(−1.64, 1.22) | 332 | 1.53(0.18, 2.30) | 206 | −0.13(−1.95, 3.46) | 207 | 0.04(−1.76, 1.67) | 137.515 | <0.001 |

| 16–17 years | 157 | 0.29(−1.42, 2.43) | 131 | 0.10(−0.69, 1.71) | 175 | 0.46(−1.42, 1.73) | 435 | −0.06(−1.46, 1.20) | 494 | −0.40(−1.82, 0.96) | 19.443 | 0.001 |

WWI weight-adjusted waist index.

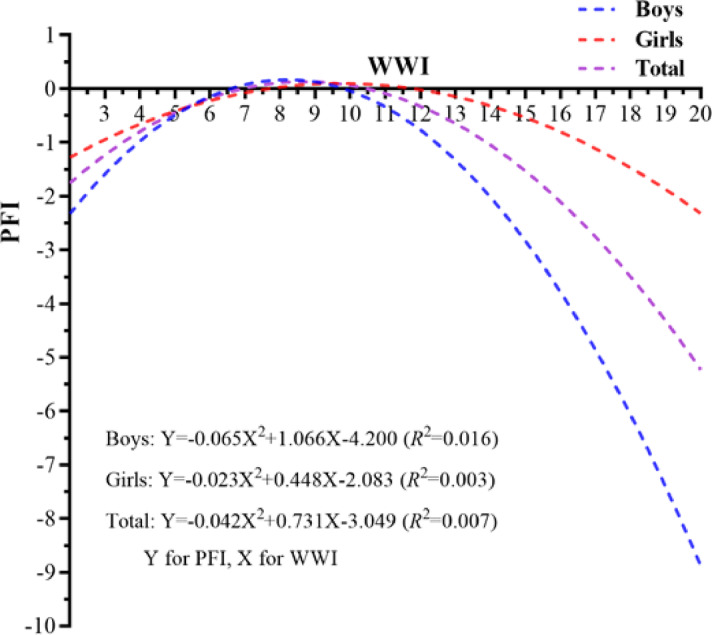

A curvilinear regression analysis stratified by sex with WWI as the independent variable and PFI as the dependent variable yielded the following curvilinear regression equation.

Boys: Y=-0.065 × 2+1.066X-4.200 R2 = 0.016.

Girls: Y=-0.023 × 2+0.448X-2.083 R2 = 0.003.

Total: Y=-0.042 × 2+0.731X-3.049 R2 = 0.007.

Y is PFI, X is WWI.

Figure 2 shows the curvilinear relationship between WWI and PFI among adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China. As can be seen from the figure, the relationship between WWI and PFI showed an inverted “U” curve, i.e., both lower and higher WWI negatively affected adolescents’ PFI, and in particular, when WWI exceeded the normal range, it had a more pronounced effect on the lowering of adolescents’ PFI. The effect of elevated WWI on PFI was more pronounced in boys compared to girls. Overall, the PFI was at its highest point when WWI was 8.8 and the PFI was 0.131.

Fig. 2.

Association between WWI and PFI among adolescents aged 12–17 years old in Xinjiang, China. WWI weight-adjusted waist index, PFI physical fitness index.

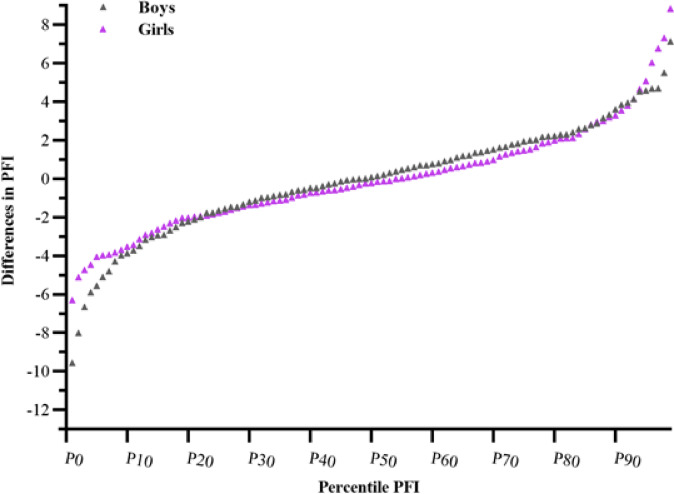

Figure 3 shows the trend of PFI percentile changes among adolescents aged 12–17 years in Xinjiang, China. Overall, the PFI of adolescents in Xinjiang, China, for both boys and girls showed a gradually increasing trend with increasing percentile. Boys’ PFI increased from − 9.55 in P1 to 7.13 in P99; girls’ PFI increased from − 6.29 in P1 to 8.83 in P99.

Fig. 3.

Trends in PFI percentiles for adolescents aged 12–17 in Xinjiang, China. PFI physical fitness index.

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that the WWI values of Chinese adolescents in Xinjiang were higher in the higher age group (16–17 years old) than in the lower age group (12–15 years old), a result that is consistent with the findings of related studies27. There are several specific reasons for this, firstly, the tendency for both weight and waist circumference values to increase with age may be an important reason for the higher WWI values at higher ages28. Secondly, adolescents in the 16–17 age group have less time for physical fitness due to being in high school, a stage where adolescents are under relatively high academic pressure to advance to higher education, leading to higher WWI29. In addition, adolescents in the 12–15 age group are in puberty, during which the body of adolescents mainly grows vertically, while horizontal waist circumference values may tend to decrease, which may also be an important reason for the lower WWI in this age group30. The results of the present study also showed that in the higher age group girls have higher WWI values than boys. The reason for this is related to the fact that girls have higher production of pubertal hormones as they grow older and their body fat content increases, which leads to higher waist circumference values. In addition, the fact that boys are more physically active than girls, which can better control the increase in waist circumference, may also be an important reason for the higher WWI of girls than boys in the present study31. The results of this study also showed that there was a significant correlation between all the indicators of physical fitness (grip strength, sit-up, standing long jump, sit and reach, 50 m dash, 20-mSRT) in adolescents, indicating that there is a close link between the indicators of physical fitness, which enables the use of the composite indicator PFI for the study.

In terms of PFI, the results of the present study showed that adolescent boys had higher levels of PFI than girls, which is consistent with the findings of the study on12. Compared with girls, boys are more inclined to participate in physical exercise due to their predisposition to gender factors, while girls prefer light physical exercise programs, resulting in higher levels of physical fitness in boys than in girls. In addition, due to a combination of genetic factors, boys have a higher muscle mass than girls, which gives them an advantage over girls in the assessment of physical fitness programs and may be an important reason why boys have a higher PFI level than girls32. However, it is of concern that there was no significant difference between the PFI levels of adolescents of different ages in this study, a finding that is inconsistent with previous studies33. It may be because the present study investigated adolescents in the age group of 12–17 years, which is at the peak of pubertal development, and the high variability in physical fitness levels is an important reason for the lack of differences in PFI among the age groups.

In this study, WWI was divided into five equal parts, and the PFIs of each class of WWI after division were compared with each other, and the differences were statistically significant. Overall, it can be seen that adolescents in the 40th ≤ WWI < 60th group had the highest PFI. Curvilinear regression analysis further confirmed that the highest level of PFI was observed when the WWI was 8.8, and that both lower and higher levels of WWI hurt PFI, especially when the WWI was higher. Related studies have confirmed that the same trend exists between BMI and waist circumference and PFI, i.e., an increase in BMI and waist circumference will lead to an increase in body weight, which will have a certain negative impact on PFI34,35. It has also been shown that an increase in body weight leads to a decrease in physical fitness levels, primarily in cardiorespiratory fitness, standing long jump, and 50-meter run performance, which leads to a decrease in PFI, as heavier adolescents need to overcome a greater body weight resistance when assessed in physical fitness programs, which leads to a decrease in performance36–38. It has also been shown that heavier adolescents are associated with lower levels of physical fitness and that there is an association between lower physical fitness and several health indicators39–41. It has also been found that there is an association between obese adolescents and lower aerobic capacity, as well as an association between lower aerobic capacity and lower physical fitness, which may be an important reason for the lower PFI in adolescents with a higher WWI14,42,43. A study based on data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that both higher WWI and lower levels of physical fitness were associated with higher insulin resistance, and that there was a joint effect44. In terms of sex, this study found that the effect of higher WWI on PFI was more pronounced compared to girls. The reason for this is that boys have higher levels of PFI than girls and are more significantly affected by WWI. In addition, girls in this study had higher WWI than boys, while girls had relatively lower levels of PFI, so the effect of WWI on PFI was relatively lower for girls.

There are certain strengths and limitations of this study. In terms of strengths, First, to the best of our knowledge, this study analyzed for the first time the association that exists between WWI and PFI in adolescents in the Xinjiang region of China. This study can provide some reference and help to improve the physical fitness level of adolescents in the Xinjiang region. Second, this study included six physical fitness indicators (grip strength, sit-up, standing long jump, sit and reach 50 m dash, and 20-mSRT) to calculate the PFI values, which comprehensively reflected the physical fitness level of the adolescents, and was able to accurately analyze the existence of the correlation between WWI and PFI. However, this study also has some limitations. First, the present study is a cross-sectional study, which can only analyze the cross-sectional associations that exist between WWI and PFI but cannot understand the causal associations that exist between them. Prospective cohort studies should be conducted in the future to analyze the causal associations. Second, the present study was conducted only on adolescents in the age group of 12–17 years, and more age groups should be included in the future to improve the generalization of the study. In addition, the sample size of this study was limited and more study samples should be included in the future to improve the reliability of the study.

Conclusions

There is an inverted “U”-shaped relationship between WWI and PFI among adolescents in Xinjiang, China. Both lower and higher WWI negatively affected PFI. Meanwhile, the effect of WWI on PFI was more pronounced in boys than in girls. In the future, the WWI level of Chinese adolescents in Xinjiang should be effectively controlled to keep it around 8.8, to ensure a high level of PFI and promote the healthy development of adolescents.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all participants for their support and assistance with our research.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Pengwei Sun, Xiaojian Yin; Data curation, Cunjian Bi; Formal analysis, Feng Zhang; Funding acquisition, Feng Zhang, Cunjian Bi; Investigation, Pengwei Sun, Xiaojian Yin; Methodology, Feng Zhang, Cunjian Bi; Project administration, Yanyan Hu, He Liu; Resources, Pengwei Sun, Xiaojian Yin; Software, Feng Zhang, Cunjian Bi; Supervision, Yaru Guo, Jun Hong; Validation, Yanyan Hu, He Liu; Visualization, Yanyan Hu, He Liu; Writing—original draft, Pengwei Sun, Xiaojian Yin, Feng Zhang, Cunjian Bi, Yaru Guo, Jun Hong, Yanyan Hu, He Liu; Writing—review & editing, Pengwei Sun, Xiaojian Yin, Feng Zhang, Cunjian Bi, Yaru Guo, Jun Hong, Yanyan Hu, He Liu; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by Xinjiang Philosophy and Social Science Research Program (3010020201); the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation(2024M750913); General Project of Cultivating Excellent Young Teachers in Anhui Universities (YQYB2023058).

Data availability

To protect the privacy of participants, the questionnaire data will not be disclosed to the public. If necessary, you can contact the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Institutional review board statement

This study was conducted by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians before the assessment of participants in this study, and participants volunteered to be assessed for this study. Approved by the Human Ethics Committee of East China Normal University (HR 475–2020).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Elyazed, T., Alsharawy, L. A., Salem, S. E., Helmy, N. A. & El-Hakim, A. Effect of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation on exercise capacity in post COVID-19 patients: a randomized controlled trail. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 21, 40 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam, B. et al. The impact of obesity: a narrative review. Singap. Med. J.64, 163 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antwi, F. et al. The effectiveness of web-based programs on the reduction of childhood obesity in school-aged children: A systematic review. JBI Libr. Syst. Rev.10, 1 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardon, G. & Salmon, J. Why have youth physical activity trends flatlined in the last decade? Opinion piece on global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants by Guthold et al. J. Sport Health Sci.9, 335 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dykstra, B. J., Griffith, G. J., Renfrow, M. S., Mahon, A. D. & Harber, M. P. Cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness in children and adolescents with obesity. Curr. Cardiol. Rep.26, 349 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser, B. J. et al. Tracking of muscular strength and power from youth to young adulthood: longitudinal findings from the childhood determinants of adult health study. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 20, 927 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Anna, C., Forte, P. & Pugliese, E. Trends in physical activity and motor development in young people-decline or improvement? A review. Children-Basel 11 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Raghuveer, G. et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness in youth: an important marker of health: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation142, e101 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larouche, R. et al. Development and validation of the global adolescent and child physical activity questionnaire (GAC-PAQ) in 14 countries: study protocol. BMJ Open14 e82275 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Dong, Y. et al. Trends in physical fitness, growth, and nutritional status of Chinese children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis of 1.5 million students from six successive National surveys between 1985 and 2014. Lancet Child. Adolesc.3, 871 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma, S., Xu, Y., Xu, S. & Guo, Z. The effect of physical fitness on psychological health: evidence from Chinese university students. Bmc Public. Health24, 1365 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu, J., Sun, H., Zhou, J. & Xiong, J. Association between physical fitness index and psychological symptoms in Chinese children and adolescents. Children-Basel 9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Chen, Y., Cai, R., Chai, D. & Wu, H. Sex differences in the association between waist circumference and physical fitness index among Tajik adolescents in the Pamir mountains of Xinjiang, China: an observational study. BMC Sports Sci. Med. R16, 188 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi, C. et al. Benefits of normal body mass index on physical fitness: A cross-sectional study among children and adolescents in Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region, China. PLoS One14, e220863 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong, Y. et al. Comprehensive physical fitness and high blood pressure in children and adolescents: A National cross-sectional survey in China. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 23, 800 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun, J. et al. Associations of body mass index, waist circumference and the weight-adjusted waist index with daily living ability impairment in older Chinese people: A cross-sectional study of the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Diabetes Obes. Metab.26, 4069 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, F. L. et al. Strong association of waist circumference (WC), body mass index (BMI), waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) with diabetes: A population-based cross-sectional study in Jilin Province, China. J. Diabetes Res. 8812431 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Tao, Z., Zuo, P. & Ma, G. The association between weight-adjusted waist circumference index and cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes. Sci. Rep-UK. 14, 18973 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding, C. et al. Association of weight-adjusted-waist index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in China: A prospective cohort study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovas. 32, 1210 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai, S. et al. Association of the weight-adjusted-waist index with risk of all-cause mortality: A 10-year follow-up study. Front. Nutr.9, 894686 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun, Q. et al. Association of the weight-adjusted waist index with hypertension in the context of predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine. EPMA J.15, 491 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao, T. et al. Association of weight-adjusted waist index with all-cause mortality among non-Asian individuals: a National population-based cohort study. Nutr. J.23, 62 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, S. et al. Weight-adjusted waist index as a practical predictor for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and non-accidental mortality risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovas. 34, 2498 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar, V. et al. Bronze and iron age population movements underlie Xinjiang population history. Science376, 62 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association, C. N. S. S. C. H. Report on the 2019th National Survey on Students’Constitution and Health (China College & University, 2022).

- 26.Tomkinson, G. R., Lang, J. J., Blanchard, J., Leger, L. A. & Tremblay, M. S. The 20 m shuttle run: assessment and interpretation of data in relation to youth aerobic fitness and health. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci.31, 152 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, J. Y. et al. Associations between weight-adjusted waist index and abdominal fat and muscle mass: Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Diabetes Metab. J.46, 747 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sternfeld, B. et al. Physical activity and changes in weight and waist circumference in midlife women: findings from the study of women’s health across the Nation. Am. J. Epidemiol.160, 912 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens, J., Katz, E. G. & Huxley, R. R. Associations between gender, age and waist circumference. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr.64, 6 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaves, R., Baxter-Jones, A., Souza, M., Santos, D. & Maia, J. Height, weight, body composition, and waist circumference references for 7- to 17-year-old children from rural Portugal. HOMO66 264 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Rosselli, M. et al. Gender differences in barriers to physical activity among adolescents. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovas. 30, 1582 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo, T., Shen, S., Yang, S. & Yang, F. The relationship between BMI and physical fitness among 7451 college freshmen: a cross-sectional study in Beijing, China. Front. Physiol.15, 1435157 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dumith, S. C., Gigante, D. P., Domingues, M. R. & Kohl, H. R. Physical activity change during adolescence: a systematic review and a pooled analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol.40, 685 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dagan, S. S., Segev, S., Novikov, I. & Dankner, R. Waist circumference vs body mass index in association with cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy men and women: a cross sectional analysis of 403 subjects. Nutr. J.12, 12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poorthuis, M. et al. Joint associations between body mass index and waist circumference with atrial fibrillation in men and women. J. Am. Heart Assoc.10, e19025 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen, X., Cui, J., Zhang, Y. & Peng, W. The association between BMI and health-related physical fitness among Chinese college students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 20, 444 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen, R. F. et al. Exercise in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma: A randomized controlled trial of effects on physical function, physical activity, lean body mass, bone mineral density, pain, and quality of life. Eur. J. Haematol.113, 298 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss, E. P., Jordan, R. C., Frese, E. M., Albert, S. G. & Villareal, D. T. Effects of weight loss on lean mass, strength, bone, and aerobic capacity. Med. Sci. Sport Exer. 49, 206 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rauner, A., Mess, F. & Woll, A. The relationship between physical activity, physical fitness and overweight in adolescents: a systematic review of studies published in or after 2000. BMC Pediatr.13, 19 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schilling, R., Schmidt, S., Fiedler, J. & Woll, A. Associations between physical activity, physical fitness, and body composition in adults living in Germany: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One18 e293555 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Joensuu, L. et al. Objectively measured physical activity, body composition and physical fitness: Cross-sectional associations in 9- to 15-year-old children. Eur. J. Sport Sci.18, 882 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mondal, H. & Mishra, S. P. Effect of BMI, body fat percentage and fat free mass on maximal oxygen consumption in healthy young adults. J. Clin. Diagn. Res.11, CC17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goran, M., Fields, D. A., Hunter, G. R., Herd, S. L. & Weinsier, R. L. Total body fat does not influence maximal aerobic capacity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 24, 841 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azzouzi, M. E. et al. Automatic de-identification of French electronic health records: a cost-effective approach exploiting distant supervision and deep learning models. BMC Med. Inf. Decis.24, 54 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

To protect the privacy of participants, the questionnaire data will not be disclosed to the public. If necessary, you can contact the corresponding author.