Abstract

Background

The study aimed to investigate the impact of high knee range of motion at discharge on functional outcome after total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of 136 patients with primary osteoarthritis who were treated between January 2022 and June 2023. Patients were classified according to the type of rehabilitation program: high range of motion (HROM) group or control group. In the HROM group, patients underwent high-intensity rehabilitation, especially without restricting the range of motion (ROM) following knee surgery. In the control group, patients received routine rehabilitation, with the affected knee achieving approximately 90 degrees of flexion at discharge. Patients’ data related to postoperative knee ROM, Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score, visual analogue scale (VAS) score, transfusion rate, wound complications, thrombus of lower limb, and usage of analgesic drugs were recorded to assess the influence of ROM at discharge on clinical outcomes.

Results

The HROM group had a higher knee ROM compared to the control group at discharge (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the HROM group and the control group in the basic demographic information, hospital stay and operation time (P > 0.05). HSS scores and knee ROM in the HROM group were significantly higher than those in the control group 1 and 2 months after surgery (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in VAS at 1, 2 and 7 days after surgery between the two groups. The usage of analgesic drugs, wound complications, thrombus of lower limb, and transfusion rates were similar between the two groups (P > 0.05).

Conclusions

High knee ROM at discharge achieved through high-intensity rehabilitation is an effective and simple way to improve early knee mobility and function. The routine application of this protocol did not increase the incidence of wound complications.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, Range of motion, Hospital for special surgery score, Discharge

Knee osteoarthritis, one of the most common types of osteoarthritis, not only causes pain, stiffness, and impaired walking, but may also increase the use of NSAIDs and thus increase all-cause mortality [1–3]. According to statistics, the annual cumulative incidence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis in China was 3.6% at knee level and 5.7% at patient level [4]. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a highly effective method for treating end-stage knee osteoarthritis. It can significantly reduce pain, improve mobility, and enhance knee function [5–7]. However, after TKA, some patients still experience severe functional impairment compared with their age- and sex-matched peers, especially when involved in highly restrictive activities [8]. Patient satisfaction with TKA is often associated with greater range of motion (ROM) and better function of the knee. If postoperative knee pain and function are improved, the patient’s satisfaction is high [9, 10]. Although TKA can successfully restore a considerable degree of knee function, there is still a need to further improve knee function to enable patients to perform all activities they consider important [11].

Miner et al. [12] found that in patients with knee flexion greater than 95 degrees, the WOMAC function score was significantly better than that of the patients with knee flexion less than 95 degrees. ROM has been established as an important factor in TKA. The ROM of the knee joint is crucial for the rehabilitation of patients with severe arthritis. Even slight changes in ROM can significantly impact the functional prognosis of the knee joint [13]. Quality criteria are generally set as 90 degrees knee flexion at discharge [14]. However, it has not been confirmed whether improving the ROM of the knee joint at the time of discharge can achieve a better knee joint functional status. The main purpose of this retrospective cohort study was to investigate whether high ROM at discharge achieved through high-intensity rehabilitation had an effect on: (1) the blood transfusion rate, thrombus of lower limb, and wound complications; (2) the affected knee ROM, the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score, visual analogue score (VAS) and usage of analgesic drugs.

Patients and methods

The patients who received primary unilateral TKA between January 2022 and June 2023 were included in the study. The patients were diagnosed with end-stage knee osteoarthritis by imaging examination and clinical diagnosis. Other exclusion criteria included hematological disorders, severe heart, liver, or kidney dysfunction, peripheral vascular disease, deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity, external knee malformations, and knee joint infection. Patients with poor alignment who were found in postoperative radiography were also excluded. All patients and their families signed written informed consent, and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuyang Hospital affiliated to Anhui Medical University.

Finally, 136 patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the study. Patients were divided into two groups: patients who underwent TKA after October 2022 received high-intensity rehabilitation postoperatively and were classified as the high range of motion (HROM) group, while those who underwent surgery before October 2022 received routine rehabilitation and served as the control group.

Surgical procedures

After anesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position. Prophylactic antibiotics and tranexamic acid (TXA) were administered before the surgical incision was made. The medial parapatellar approach was used to separate the patella so that the quadriceps femoris and patella could be pushed to the outside. Then, the joint surface was trimmed before bending the knee to expose the joint. Tourniquets were used before the bone was cut off. The gap balance technique was used to complete the osteotomy and soft tissue balance. Suitable posterior stabilization prosthesis was selected for installation. After confirming no active bleeding, the incision was sutured layer by layer, and the drainage tube was implanted. Then, we applied pressure to the wound with an elastic bandage. TXA (1000 mg/50 mL) was injected into the joint and left open after being clamped for 4 h. The drainage tube was removed 24 h post-surgery. All procedures were performed by a senior orthopedic surgeon.

Rehabilitation

All patients received the same multimodal analgesia protocol, including a single preoperative nerve block, postoperative intravenous infusion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ice application, and so on. Patients were given patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) within 48 h following surgery. After the removal of the drainage tube, physical therapy was conducted under the supervision of therapists, which included two rehabilitation protocols.

HROM group rehabilitation

Patients in the HROM group underwent a high-intensity rehabilitation training program throughout the perioperative period [15], which primarily included muscle strength training combined with passive rehabilitation exercises, active rehabilitation exercises, and progressive weight-bearing training. Preoperatively, patients performed knee flexion and extension exercises in bed, ensuring the heel was brought as close to the hip as possible. Straight leg raise training ensured the heel was slowly lifted to 20 cm above the bed and held suspended for 10 s. The above two training methods were performed 30 times/group, 3 groups/day. Postoperative exercises utilized continuous passive motion (CPM) for passive training, starting at a small angle and gradually increasing to the patient’s tolerance threshold, 2 times/day for 30 min/time. All patients were instructed to perform straight leg raises, knee flexion and extension exercises, and ankle pump exercises 30 times/group, 3 groups/day. On the second postoperative day, patients were advised to stand by the bedside. On the third postoperative day, they began using a walker to walk slowly with assistance, with the distance and duration of walking gradually increased each day. Starting on the fifth postoperative day, patients were instructed to actively or passively perform knee flexion exercises, requiring them to maintain the bend for 8 min, 2–3 times daily.

Control group rehabilitation

The training program for the control group was developed based on previously published rehabilitation protocols [16]. During the first 4 postoperative days, the CPM machine was initiated at a small angle and gradually increased to approximately 90 degrees of knee flexion, twice daily for 30 min each session. Patients were advised to perform straight leg raises and ankle pump exercises 10–20 times/day, along with knee flexion and extension exercises 10 times daily. By the fifth postoperative day, the frequency of these exercises was increased. The frequency of standing and walking activities was progressively increased based on the patient’s recovery progress. The main differences compared to the HROM group were as follows: (1) The ROM for CPM was limited to approximately 90 degrees of knee flexion; (2) There was no standardized guidance, and the training sessions were less frequent; (3) Rehabilitation was limited to the postoperative period and lacked exercises to maintain the knee in a flexed position.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were ROM, Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score, and analgesic dosage used via PCIA. The secondary outcomes were wound complications, length of hospital stay, transfusion rate and thrombus of lower limb. Patients were followed up for ROM and HSS scores at first month, second month, and 12th month postoperatively. VAS scores were recorded on postoperative day 1, 2, and 7. 24-hour and 48-hour analgesic used via PCIA were recorded. Color Doppler ultrasound was performed in patients with clinically suspected lower extremity thrombosis.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 23.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform statistical analysis. Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test was used for the comparison of nominal data. After the continuous variables were tested by Shapiro-Wilk test, Student’s t-test was employed to compare continuous variables of normally distributed data sets, whereas the Mann Whitney U-test was used for non-normally distributed data sets. The results were assessed using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) for consistency testing. For multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction was applied, with P < 0.05 divided by the number of comparisons set as the threshold for statistical significance. For other outcome measures, the level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

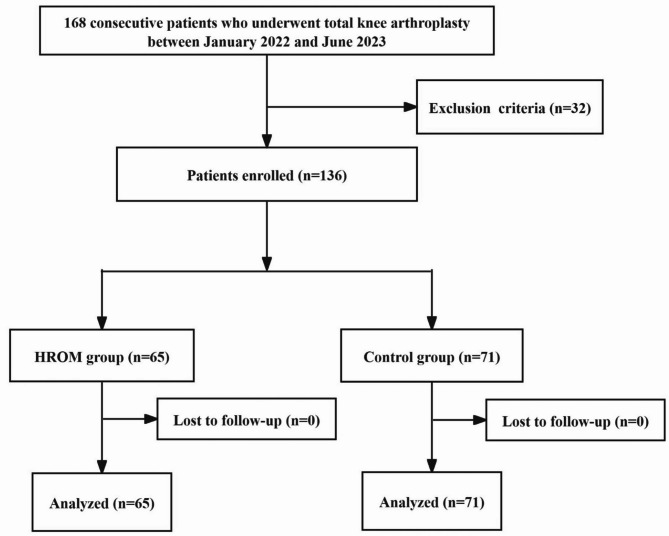

During the recruitment period from January 2022 to June 2023, 136 patients with osteoarthritis who received unilateral primary TKA were ultimately included in the analysis. There were 65 patients in the HROM group and 71 patients in the control group (Fig. 1). Inter-rater reliability analysis revealed a good consistency between the reviewers (ICC = 0.87). The HROM group had a higher knee ROM compared to the control group at discharge (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in age (P = 0.380), sex (P = 0.775), operative side (P = 0.276), body mass index (P = 0.091), preoperative ROM (P = 0.580) and other general data between the HROM group and the control group (Table 1). The baseline characteristics of the two groups demonstrated no significant differences via Student’s t-test or Chi-square test, and due to the limited sample size, we refrained from applying propensity score matching for adjustment. However, through multivariate regression analysis, we found that the statistical significance of post-adjustment intergroup differences remained unchanged, supporting the robustness of the results.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for patient enrollment

Table 1.

Comparison of the baseline information between the HROM and control groups

| HROM group (n = 65) | Control group (n = 71) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 66.51 ± 6.01 | 67.48 ± 6.78 | 0.380 |

| Sex (man/woman) | 16/49 | 16/55 | 0.775 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.20 ± 3.41 | 27.20 ± 3.43 | 0.091 |

| Operative side (L/R) | 26/39 | 35/36 | 0.276 |

| Operation time (min) | 110.15 ± 16.82 | 110.06 ± 14.80 | 0.971 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 9.43 ± 2.39 | 10.24 ± 2.84 | 0.076 |

| Preoperative ROM (degree) | 102.46 ± 8.47 | 101.66 ± 8.32 | 0.580 |

| Preoperative HSS scores | 45.74 ± 4.74 | 44.75 ± 3.90 | 0.184 |

| Preoperative VAS | 5.75 ± 1.19 | 5.68 ± 1.14 | 0.698 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ROM, range of motion; HSS, Hospital for Special Surgery; VAS, visual analogue scale

The ROM in the HROM group was significantly higher than that in the control group at discharge and 1 or 2 months after operation ((P < 0.001). In addition, the HSS scores were significantly higher than that in the control group at 1 and 2 months after surgery ((P < 0.001). Moreover, there was no significant difference in VAS between the two groups at postoperative day 1, 2, 7 (P > 0.05). At 12 months, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in ROM and HSS scores (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences in transfusion rate, wound complications, analgesic dosage used via PCIA and thrombus of lower limb between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2). All cases of wound complications and lower limb thrombosis in the two groups were successfully treated before discharge.

Table 2.

Comparison of the clinical outcomes between the HROM and control groups

| HROM group (n = 65) | Control group (n = 71) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROM at discharge (degree) | 101.20 ± 7.44 | 91.48 ± 7.85 | 0.000 |

| ROM at first month (degree) | 105.38 ± 6.92 | 97.00 ± 7.59 | 0.000 |

| ROM at second month (degree) | 110.03 ± 5.70 | 105.00 ± 5.66 | 0.000 |

| ROM at 12th month (degree) | 112.08 ± 3.93 | 111.06 ± 4.19 | 0.146 |

| HSS at first month | 75.43 ± 4.70 | 70.06 ± 4.14 | 0.000 |

| HSS at second month | 79.48 ± 3.67 | 76.87 ± 3.35 | 0.000 |

| HSS at 12th month | 88.40 ± 3.35 | 87.25 ± 3.43 | 0.051 |

| VAS at POD 1 | 3.06 ± 0.83 | 2.96 ± 0.78 | 0.453 |

| VAS at POD 2 | 2.92 ± 0.91 | 3.08 ± 0.86 | 0.288 |

| VAS at POD 7 | 2.29 ± 0.96 | 2.21 ± 0.88 | 0.608 |

| Mean 24-h analgesic used via PCIA (mL) | 51.85 ± 2.04 | 51.69 ± 2.07 | 0.660 |

| Mean 48-h analgesic used via PCIA (mL) | 102.18 ± 2.08 | 101.63 ± 2.37 | 0.154 |

| Transfusion | 1 | 0 | 0.478 |

| Thrombus of lower limb | 2 | 1 | 0.938 |

| Wound complications | 1 | 4 | 0.417 |

Abbreviations: ROM, range of motion; HSS, Hospital for Special Surgery; VAS, visual analogue scale; POD, postoperative day; PCIA, patient-controlled intravenous analgesia

Discussion

Knee ROM has consistently been viewed as a crucial metric for assessing the outcome of knee surgery. Possessing a satisfactory ROM is advantageous in enhancing flexibility and mitigating stiffness [17]. A previous study [18] reported that there is a strong association between ROM at discharge and later ROM and function, which proves the practicability and relevance of ROM as an early postoperative clinical indicator. In summary, ROM should always be the focus of treatment from the time of discharge until formal rehabilitation ceases.

After patients undergo TKA, routine rehabilitation always requires that patients achieve a knee ROM of 90 degrees upon discharge from the hospital [14]. This measure is intended to prevent poor ROM after discharge, which can lead to long-term knee stiffness, decreased knee function, and subsequently lower patient satisfaction. However, current research [19] suggests that there is no standardized postoperative restriction following TKA. The recovery of preoperative activities should be individualized based on the patient’s ability. Therefore, we no longer limit the knee ROM upon discharge to 90 degrees. Instead, we gradually increase the patient’s ROM as tolerated, aiming for the maximum ROM possible upon discharge. Compared to routine rehabilitation, our present study demonstrated that patients with high ROM at discharge could improve early knee mobility and function. Moreover, this protocol did not increase the pain intensity of patients or the incidence of wound complications.

In recent years, with the continuous development of rehabilitation concepts, many studies have begun to pay attention to the impact of postoperative rehabilitation on knee functional recovery [20–22]. Exercises such as maximal strength training and cold compression dressings can effectively strengthen the muscles of the lower limbs, improve the ROM of the knee joints, and promote the rapid recovery of postoperative knee function [15, 23, 24]. However, at present, no relevant studies have shown whether high knee ROM at discharge has an impact on the postoperative outcome of patients. Most studies are limited by variables such as differences in hospital stay duration, prosthesis types, or surgical philosophies, with few establishing clear criteria for knee ROM at discharge. This gap in the literature motivated the present study. The study showed high knee ROM at discharge achieved through high-intensity rehabilitation is an effective and simple way to improve early knee mobility and function. In this study, the rehabilitation exercise program of the HROM group did not restrict the knee flexion ROM. Therefore, the HROM group was able to perform more adequate muscle exercise and joint movement in the early period. The knee motion and HSS score of the high-flexion group were significantly higher than those of the control group at 1 and 2 months after surgery. Jiao et al. [15] found that high-intensity progressive rehabilitation training was more effective than the control group in the early stages. This is also consistent with our results. However, there were no significant differences in knee motion and HSS scores between the two groups at 12 months. For the lack of statistical difference between the two groups after 12 months, we consider the following possibilities. First, both groups achieved optimal recovery at 12 months, possibly due to the ceiling effect. Second, most patients will continue rehabilitation training after discharge. However, due to the complex rehabilitation protocol of patients in the HROM group and the lack of direct supervision and guidance of therapists, the effectiveness of long-term postoperative rehabilitation training is difficult to guarantee.

The main goals of TKA are to relieve pain caused by knee disease, improve joint function, restore joint ROM, and improve patients’ quality of life. At present, whether the function of the knee joint is related to the ROM of the knee joint has been controversial. Richter et al. [14] found that there was no correlation between the outcome of total knee surgery and whether the knee had reached 90 degrees flexion. However, LaHaise et al. [25] found that patients with a flexion of 80 to 90 degrees at discharge were more than 2 times more likely to develop manipulation under anesthesia than those with more than 90 degrees of flexion. There is an association between lower ROM at discharge and a higher risk of manipulation under anesthesia after TKA. Moreover, Devers et al. [26] suggested that increasing knee flexion, especially above 130 degrees, may improve functional ability and knee sensation after TKA. Similar to our findings, greater ROM generally predicts better knee function and a smaller risk of knee stiffness. Although there was no significant difference in HSS between the two groups after 1 year, the HROM group showed better ROM and function in the early or subacute phase after TKA.

Postoperative pain is a challenge that cannot be ignored. It not only limits patients’ early mobility and reduces their ROM, but also may cause a series of serious health problems [27]. Specifically, postoperative pain not only increases the risk of knee stiffness, but also may lead to serious complications such as deep vein thrombosis and muscle atrophy. More seriously, it may also have adverse effects on the cardiopulmonary system [28]. Therefore, pain management is crucial for patients after TKA surgery. In this study, rehabilitation therapists usually prioritize straight leg raising exercises to reduce the resistance of quadriceps muscles when bending the knee joint. This reduces the patient’s inability to relax due to muscle tension and increases the pain caused by knee bending. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the analgesic dosage used via PCIA between the two groups of patients. Besides, no significant difference in VAS was found between the two groups at postoperative day 1, 2, 7, which confirms that our rehabilitation program is feasible.

However, there are some limitations to this study. Firstly, this is not a randomized controlled trial, which may introduce selection bias and reduce the internal validity of our findings. Secondly, the independent effects of particular exercises on achieving high ROM remain unclear and warrant further investigation. Thirdly, adherence to rehabilitation exercises could not be precisely quantified, so the true extent of the difference between the two groups could not be determined.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that patients with a high knee ROM at discharge achieved through high-intensity rehabilitation tend to achieve better functional and rehabilitation outcomes in the early or subacute phase compared to the control group. Additionally, high knee ROM at discharge does not increase the incidence of post-operative pain and complications. Therefore, we suggest that increasing patients’ knee ROM at discharge is a simple, effective, and feasible approach.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- HROM

High range of motion

- TKA

Total knee arthroplasty

- ROM

Range of motion

- HSS score

Hospital for Special Surgery score

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

- TXA

Tranexamic acid

- PCIA

Patient-controlled intravenous analgesia

- CPM

Continuous passive motion

Author contributions

The study was designed by JM. Material preparation and study were performed by all authors. The data collection and analysis were performed by YZ, ZD, ZG and RS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JM and YZ, and was revised by WC. JM and YZ contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.All authors read and approved submission of the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Major Natural Science Project of Universities in Anhui Province (No. KJ2021ZD0034) and the Scientific Research Fund of Anhui Medical University (No.2022xkj071).

Data availability

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuyang Hospital of Anhui Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jimin Ma and Yakun Zhu contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

- 1.Liu Q, et al. Knee symptomatic osteoarthritis, walking disability, NSAIDs use and All-cause mortality: Population-based Wuchuan osteoarthritis study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, et al. Knee osteoarthritis, potential mediators, and risk of All-Cause mortality: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73(4):566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muraki S, et al. Association of radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis with health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort study in Japan: the ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(9):1227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, et al. Incidence and related risk factors of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a population-based longitudinal study in China. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein AM, et al. Estimating the burden of total knee replacement in the united States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(5):385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGrory B, et al. The American academy of orthopaedic surgeons Evidence-Based clinical practice guideline on surgical management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(8):688–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh JA, Lewallen DG. Depression in primary TKA and higher medical comorbidities in revision TKA are associated with suboptimal subjective improvement in knee function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noble P.C., et al. Does total knee replacement restore normal knee function? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;431:p157–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nam HS, et al. Preoperative education on realistic expectations improves the satisfaction of patients with central sensitization after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(11):4705–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeFrance MJ, Scuderi GR. Are 20% of patients actually dissatisfied following total knee arthroplasty?? A systematic review of the literature. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(3):594–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss JM et al. What functional activities are important to patients with knee replacements? Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2002(404): pp. 172–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Miner AL, et al. Knee range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: how important is this as an outcome measure? J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(3):286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jergesen HE, Poss R, Sledge CB. Bilateral total hip and knee replacement in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: an evaluation of function. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;137:120–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richter J, Matziolis G, Kahl U. Knee flexion after hospitalisation is no predictor for functional outcome one year after total knee arthroplasty]. Orthopadie (Heidelb). 2023;52(2):159–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiao S, et al. High-Intensity progressive rehabilitation versus routine rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39(3):665–e6712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artz N, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwata M, et al. Dynamic stretching has sustained effects on range of motion and passive stiffness of the hamstring muscles. J Sports Sci Med. 2019;18(1):13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naylor JM, et al. Is discharge knee range of motion a useful and relevant clinical indicator after total knee replacement? Part 2. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(3):652–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortier LM, et al. Activity recommendations after total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103(5):446–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mistry JB, et al. Rehabilitative guidelines after total knee arthroplasty: A review. J Knee Surg. 2016;29(3):201–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kool N, Kool J, Bachmann S. Duration of rehabilitation therapy to achieve a minimal clinically important difference in mobility, walking endurance and patient-reported physical health: an observational study. J Rehabil Med. 2023;55:jrm12322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiao S, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery combined with quantitative rehabilitation training in early rehabilitation after total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2024;60(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy AS, Marmar E. The role of cold compression dressings in the postoperative treatment of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1993(297): pp. 174–8. [PubMed]

- 24.Husby VS, et al. Randomized controlled trial of maximal strength training vs. standard rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2018;54(3):371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaHaise KM, et al. Range of motion at discharge predicts need for manipulation following total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2021;34(2):187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devers BN, et al. Does greater knee flexion increase patient function and satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(2):178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li JW, Ma YS, Xiao LK. Postoperative pain management in total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Surg. 2019;11(5):755–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morishita S, et al. Face pain scale and Borg scale compared to physiological parameters during cardiopulmonary exercise testing. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2021;61(11):1464–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.