Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and traditional preventive measures focus on lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic interventions, and risk stratification. Recently, imaging has emerged as an interesting tool in cardiovascular prevention. This review explores the role of various imaging modalities in early detection, risk assessment, and disease monitoring. Noninvasive techniques such as carotid ultrasound, arterial stiffness assessment, echocardiography, and coronary artery calcium scoring enable the identification of subclinical atherosclerosis and ventricular dysfunction, providing insights that complement conventional risk factors. Coronary computed tomography angiography and cardiac magnetic resonance offer high-resolution visualization of vascular and myocardial pathology, contributing to refined risk stratification. Furthermore, emerging markers such as epicardial adipose tissue and hepatic steatosis are gaining recognition as potential predictors of cardiovascular risk. Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) are revolutionizing cardiovascular imaging by enhancing image interpretation, automating risk prediction, and facilitating personalized medicine. Future research should focus on optimizing the integration of imaging into clinical workflows, improving risk prediction models, and exploring AI-driven innovations. By exploiting imaging technologies, clinicians could enhance primary and secondary prevention strategies, ultimately reducing the global burden of CVDs.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, cardiac magnetic resonance, cardiovascular imaging, cardiovascular prevention, echocardiography, epicardial adipose tissue

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality, imposing a substantial burden on healthcare systems. Characterized by conditions such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke, CVDs contribute to a significant proportion of worldwide health challenges. With the advancement of medicine in the treatment of CVDs, it seems imperative to explore innovative and effective approaches in prevention, considering that the prevalence of CVDs continues to rise, and so necessitating a paradigm shift toward proactive and preventive healthcare strategies. Recognizing the importance of preventive measures is crucial to change the approach to CVDs, as well as to mitigate the socioeconomic burden associated with these conditions.

This review aims to explore the role of imaging in cardiovascular prevention, a field that has witnessed remarkable advancements in recent years. While preventive measures have traditionally focused on lifestyle modifications, risk factor management, and pharmacological interventions, the integration of imaging technologies is emerging as a pivotal component in the early detection, risk stratification, and monitoring of individuals at risk for cardiovascular events.

Among noninvasive techniques, the ankle–brachial index (ABI) is a ratio calculated by comparing the systolic blood pressure measured at the ankle with that measured at the brachial artery. Proposed for noninvasive diagnosis of lower-extremity peripheral artery disease, the ABI has demonstrated its potential as an indicator of atherosclerosis in other vascular locations and as a prognostic marker for cardiovascular events.[1] However, according to ESC Guidelines, its application in risk classification is limited, except for women at intermediate risk.[2]

Imaging modalities, ranging from traditional techniques such as echocardiography to technologies like coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), provide unprecedented insights into cardiac and vascular structure, function, and dynamics. The ability to visualize and assess cardiovascular anatomy and physiology noninvasively has revolutionized our understanding of disease progression and allow for the implementation of personalized preventive strategies.[3]

In the realm of cardiovascular prevention, the utilization of advanced imaging modalities plays a pivotal role in both diagnosis and risk assessment. Here, we provide an insightful overview of the various imaging modalities employed in cardiovascular imaging.[2,4]

NATURAL HISTORY OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE DEVELOPMENT

The natural history of CVD unfolds as a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The disease typically begins with unmodifiable risk factors such as family history, age, and gender, influencing the individual’s susceptibility. Over time, unhealthy behaviors such as poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, diabetes, and smoking amplify these risks, fostering the development of atherosclerosis, that initially is a subclinical condition. Recently epicardial fat, a metabolically active visceral adipose tissue surrounding the heart, has been increasingly recognized as an independent cardiovascular risk factor due to its proinflammatory and proatherogenic properties, contributing to coronary artery disease and other cardiac dysfunctions.[5,6,7] As atherosclerosis advances, it may remain asymptomatic for years while in the meantime it can develop an atherogenic plaque or a subclinical cardiac dysfunction, such as adverse cardiac remodeling, extracellular matrix remodeling, and myocardial fibrosis. After that, especially in case of continuous poor control of risk factors, a critical event can occur, such as the rupture of a vulnerable plaque, leading to an acute event such as myocardial infarction and stroke and so exacerbating the CVD.[4] In the subject already suffering from CVD, clinically symptomatic or not, the control of risk factors and the correct application of pharmacological and interventional therapies improve the prognosis, falling within the concept of secondary prevention.

NONINVASIVE MODALITIES IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE PREVENTION: UNLOCKING INSIGHTS WITHOUT INVASIVE PROCEDURES

Essentially, the goal of using imaging in cardiovascular prevention is to identify atherosclerosis and ventricular dysfunction early when it has not yet caused the clinical event, to apply proper pharmacological and interventional therapies.

Carotid ultrasound

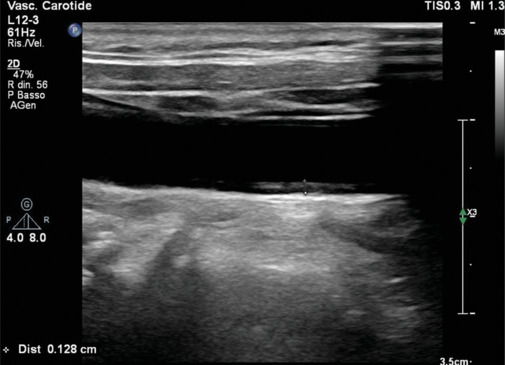

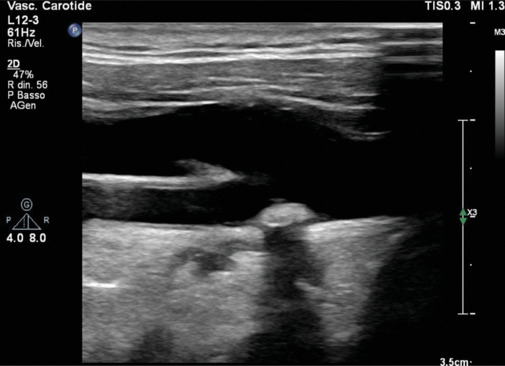

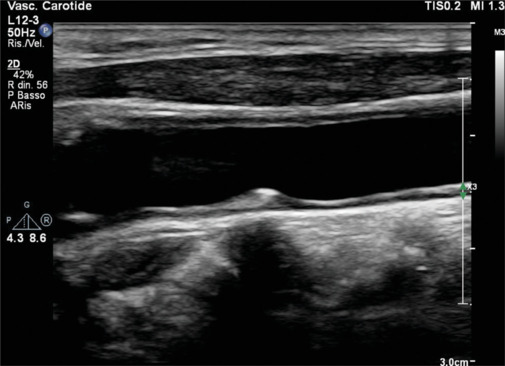

This noninvasive imaging modality focuses on the carotid arteries, offering real-time insights into vascular structure and blood flow, and so identifying atherosclerotic plaques [Figures 1-3]. A plaque is defined as a focal wall thickening ≥50% than the vessel wall or a focal thickening ≥1.5 mm. Carotid ultrasound aids in the early detection of vascular changes and could contribute to risk stratification and to inform about tailored preventive measures. In fact, according to the 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiovascular Prevention, this technique may be considered a risk modifier in case of plaque detection in patients at intermediate risk when coronary artery calcium (CAC) score is not feasible.[2] Systematic use of intima–media thickness (IMT) to improve risk assessment is not recommended due to the lack of methodological standardization, and the absence of the added value of IMT in predicting future cardiovascular events, even in the in the intermediate-risk group.[2]

Figure 1.

Mild carotid intima-media thickness. Normal values range reference is 0.6–0.9 mm. The anechoic line is the internal elastic lamina

Figure 3.

Long-axis view of a hyperechogenic plaque at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery

Figure 2.

Long axis view of an iso-echogenic soft plaque in the common carotid artery, responsible of a noncritical stenosis

Arterial stiffness

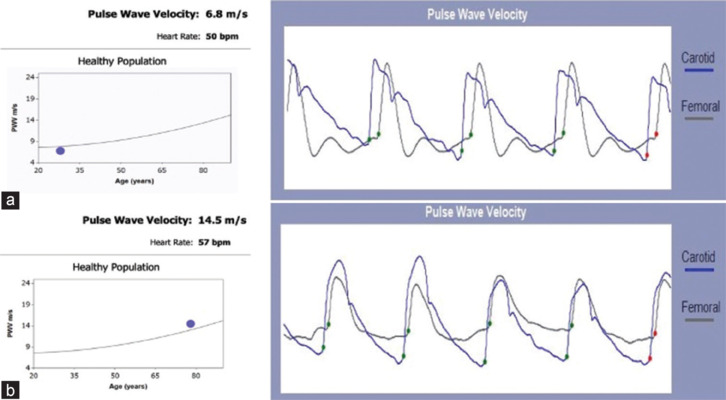

This parameter can be measured with several methods, the more common of which are the pulse wave velocity (PWV) and the arterial augmentation index.[2,8] The PWV is determined by recording the arterial pulse wave at a proximal artery, typically the common carotid, and a distal one, like the femoral. These arteries are commonly chosen due to their superficial location, and to the fact that the distance between these two arteries approximates the aortic measurement. The instrument employed for this purpose is a pulse tonometer.[9] The augmentation index is an indirect measure of arterial stiffness, and it is calculated as augmentation pressure divided by pulse pressure ×100: when stiffness increases, there is a faster propagation of the forward pulse wave and a more rapid reflected wave.[10] Some studies have demonstrated a possible role of arterial stiffness in predicting CVD risk and improving risk assessment.[2] However, its measurement is difficult and not so reproducible: these elements preclude widespread use.[2]

Despite not being included in recent ESC Guidelines on CVD Prevention, PVW and augmentation index have been demonstrated to correlate with the risk of developing CVDs and all-cause mortality, so being a useful tool to measure the vessels aging and helping to estimate the CV risk.[11] A large meta-analysis from 2014 demonstrated that PWV was an independent predictor of coronary heart disease, stroke, and CVD events.[12] Moreover, PWV was shown to be altered in different risk profiles and to improve the risk prediction (13% for 10-years CVD risk for intermediate risk) in some subgroups[12] [Figure 4]. It was even demonstrated that, in hypercholesterolemic children, the PVW was already altered, therefore, suggesting an early mechanism of atherosclerosis.[1] Arterial stiffness was correlated also with impaired diastolic function and the earliest stage of heart failure.[13]

Figure 4.

Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity measurement: (a) normal pulse wave velocity in a young 29-year-old man with no cardiovascular risk factors; (b) elevated pulse wave velocity in a 77-year-old man with obesity, type 2 diabetes and hypertension

Echocardiography

Due to lack of evidence showing that echocardiography improves CVD risk reclassification, this imaging technique is not routinely recommended in primary CVD prevention and risk assessment.[2] However, the possibility of unveiling subtle anomalies even before their clinical manifestation could contribute, on an individual basis, to the risk stratification and to guide personalized preventive strategies. In a recent meta-analysis, hypertrophy, diastolic diameter, and dilations of the left atrium and of the aortic root were associated with an increased risk of adverse events in individuals without known CVDs.[14] Several recent studies suggested a possible role of novel echocardiographic risk marker, such as the longitudinal strain, the three-dimensional morphological and functional evaluation, and the identification and characterization of epicardial adipose tissue (EAT). Moreover, it was described the use of echocardiographic calcium score as a surrogate of CAC score and as a predictor of angiographic coronary artery disease.[15,16]

Echocardiography has an important role in evaluating LV systolic and diastolic functions, both with traditional methods and with more recent methods.[17] In patient with asymptomatic heart failure, echocardiography has been demonstrated to have an incremental value to other risk factors in predicting the evolution of heart failure and cardiovascular events.[18] In young athletes, after the electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiography is the essential first-line screening imaging technique in the prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD), allowing the early identification of structural heart disease, that could be the cause of SCD in these subjects.[19,20] In asymptomatic patients with CV risk factors, without know CV diseases, and with apparently normal LV function, tissue Doppler imaging has been correlated to a significant additional prognostic value, suggesting a possible role in tailored preventive treatment.[21] Recently strain imaging of LV is acquiring growing importance for the evaluation of ventricular function[22] and has been demonstrated to predict all-cause mortality better than ejection fraction and wall motion score index.[23] In cardio-oncology, the LV strain has acquired great importance for detecting and evaluating drug toxicity, even when the ejection fraction is normal or mildly reduced[24] [Figure 5]. Moreover, LV strain could help in the differential diagnosis of cardiomyopathies, hypertensive heart disease, or athlete’s heart [Figure 6]. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors can influence left ventricular myocardial performance in a selective and gender-specific manner, as observed in studies that assess systolic and diastolic impairment through myocardial work quantification, even if its role in cardiovascular prevention has not yet been established.[25,26] Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) easily[27] allows to measure coronary flow velocity in the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, obtained by pulsed-wave Doppler in mid-distal LAD, both the rest flow velocity and the reserve flow velocity during stress with dipyridamole. High resting coronary flow velocity is usually associated with a reduced coronary flow velocity reserve, and it has been associated with worse long-term survival in patients with chronic coronary syndrome.[28] In patients with chronic coronary syndrome and normal LVEF, high resting coronary flow velocity is a predictor of poor outcome; the combination of high resting velocity and low reserve velocity has been associated with the worst prognosis.[29] More, in patients with ischemic and nonischemic heart failure with reduced LVEF, high resting coronary flow velocity has been associated with worse survival, independently and additively to resting LVEF, coronary flow reserve velocity, left ventricle contractile reserve, and inducible ischemia.[30]

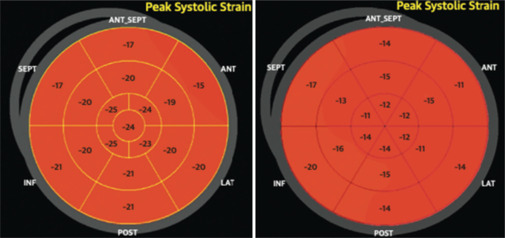

Figure 5.

Global longitudinal strain (GLS) images from the same patient before (left) and after (right) treatment with Doxorubicine. Left image: A GLS average of −20.3% with ejection fraction (EF) 61%. Right image: A GLS average of −17% with EF 60%, detecting a left systolic disfunction even with normal EF. EF: Ejection fraction; GLS: Global longitudinal strain; ANT_SEPT: Antero-septal; ANT: Anterior; LAT: Lateral; POST: Posterior; INF: Inferior; SEPT: Septal

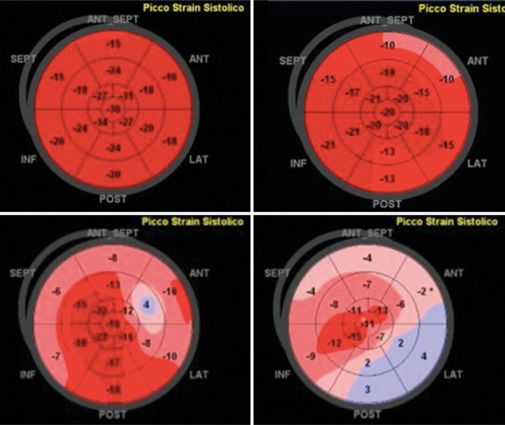

Figure 6.

Global longitudinal strain (GLS) pattern in different conditions: Normal athlete (upper left), arterial hypertension (upper right), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (bottom left), transthyretin-amyloidosis (bottom right). GLS: Global longitudinal strain, TTR: Transthyretin; ANT_SEPT: Antero-septal; ANT: Anterior; LAT: Lateral; POST: Posterior; INF: Inferior; SEPT: Septal

Coronary artery calcium score

The determination of the CAC score is done from axial scans of cardiac computed tomography (CT) [Figure 7], even without the use of a contrast medium. The effective dose of radiation is usually low, <1.5 mSv, comparable to the exposure associated with mammography.[31] A calcification within epicardial coronary arteries is identified as an area of hyperattenuation ≥1 mm2 or ≥3 adjacent pixels with >130 Hounsfied units (HU).[31] The more used system for the quantification of the CAC score is the Agatston method: it uses the weighted sum of lesions multiplying the area of calcium by a factor related to maximum plaque attenuation. This method is reproducible and allows to categorize absolute scores as 0 (no), 1–10 (minimal), 11–100 (mild), 101–400 (moderate), >400 (severe), and >1000 (very severe).

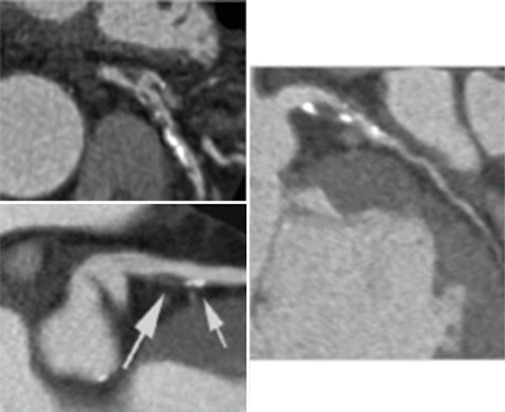

Figure 7.

Cardiac computed tomography showing atheromatic coronary calcifications. White arrows indicate coronary artery calcification and a non-critical plaque

According to the 2021 ESC Guidelines on CVD Prevention, the CAC score can be considered in addition to other risk factors to upward or downward cardiovascular risk.[2] Once calculated, it should be compared with the exact value expected for a subject of the same age and sex: based on this comparison, cardiovascular risk is remodulated for better or worse. This can be very useful in the case of calculated risk values close to the thresholds. These recommendations come from several studies and metanalyses, that have described the addictive predictive value of CAC score in different subgroups of patients.[15,32,33] The recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on primary prevention of CV disease and on the management of blood cholesterol have given an important role to the CAC score in the decision-making process of the therapeutic strategy with statins.[32,34,35] However, the limitations of the CAC score should not be forgotten. In fact, it does not provide information on stenosis severity or total plaque burden, especially in the case of soft plaque.[36] Another interesting observation concerns the increase of CAC score during treatment with statins, especially at high doses, due to an increase of densely calcified plaque, that may represent the plaque-stabilizing effect of statins beyond the deceleration of atherosclerotic plaque progression due to cholesterol reduction.[37,38] This is paradoxical because, stated that a greater CAC score is a strong predictor of increased risk for cardiovascular events, the increase of CAC density observed with high-dose statin treatment may be associated with more stable and less dangerous plaque features and so lower risk of cardiovascular events.[39] Already in 2014, it was stated that CAC density should have been considered together with the CAC scoring system using the Agatson method.[39] Considering this, the role of CCTA as a noninvasive technique to quantify and even characterize coronary plaques may be relevant, and further studies would be desirable.

Contrast computed tomography coronary angiography

CCTA can identify coronary stenoses and predict cardiac events, as shown in the literature[2] [Figure 8]. In fact, the use of this technique demonstrated to reduce the rates of myocardial infarction or coronary death in patients with stable angina.[2] CCTA has a high negative predictive value, contributing to rule out significant coronary artery disease and providing reassurance in low-to intermediate-risk patients, making it an interesting tool in cardiovascular prevention. In a consistent study from 2009, led on 1256 patients with suspected CAD, CCTA demonstrated to have a significant prognostic impact on the prediction of cardiac events for more than 1 year, even identifying a patient population with an event risk lower than predicted by conventional risk factors only.[40] In a subsequent study by the same group, aimed at evaluation of the long-term prognostic impact of CCTA in patients with suspected CAD, CCTA predicted death and myocardial infarction and the need for subsequent revascularizations up to 5 years.[41] The same group concluded by stating that CCTA, evaluating both plaque burden and stenosis, carried additional prognostic value and that a prognostic score based on these data could improve risk prediction over clinical risk scores.[42] Interesting results come from the CONFIRM registry, led more than 10 years ago in 12-center 6-country, over thousands of subjects. In asymptomatic individuals, CCTA stratified the prognosis, but the additional risk-predictive advantage was not clinically significant compared with a classic risk model based on the CAC score.[43] In subjects with angina and suspected CAD, CCTA adds incremental discriminatory power over CAC for the evaluation of persons at risk of death or myocardial infarction.[44]

Figure 8.

Contrast computed tomography coronary angiography showing absence of significant epicardial coronary stenosis along the main coronary axes. RCA: Right Coronary Artery; LAD: Left Anterior Descending coronary artery; Cx: Circumflex coronary artery

CCTA was studied in different settings of CVD prevention but actually there is no strong evidence to support its use in this setting, because its value over CAC score is actually not known.[2,45] Recent trials such as SCOT-HEART[46] and ISCHEMIA[47] have demonstrated that increasing severity of atherosclerotic disease defined by CCTA correlated with the risk of adverse events.

Early CCTA has focused on the study of obstructive stenosis; CCTA is also the only noninvasive tool for the evaluation of nonobstructive CAD, which contributes to adverse cardiac events. Recent CCTA imaging technique studies enable the quantification and characterization of atherosclerotic plaques, assessing the extent of CAD and differentiating between various plaque features. In fact, CCTA is useful in predicting clinical outcomes basing on the extent of coronary atherosclerosis and on plaque characteristics such as low attenuation-soft plaque, positive remodeling, and spotty calcification.[48] Comparing several studies, it seems relevant that not only plaque burden, but also plaque location, composition, and vulnerability, along with stenosis severity, play a role in pathophysiology and outcomes.[49] The combination of morphologic and functional features of coronary plaques could improve the detection of vulnerable plaques and therefore have a role in secondary prevention.[50] From a 2014 analysis of COURAGE trial patients, it emerged that the anatomic burden of coronary stenosis, in this case, evaluated using coronary angiogram in patient treated medically, was a consistent predictor of death and myocardial infarction, whereas ischemic burden evaluated with single photon emission CT was not. In this perspective, CCTA enables an accurate anatomic assessment of coronary plaque and potentially could have an important role as a prognostic stratifier.[51] The application of semiautomatic software has already been evaluated in 2016, where it was observed that a semiautomatically derived index of total coronary atheroma volume had good accuracy in identifying patients with significant CAD.[52]

This emerging evidence along with other applications based on CT, such as derived fractional flow reserve and artificial intelligence (AI), support the possible future role of CCTA role as an important technique in CV primary and secondary prevention.[53]

Cardiac magnetic resonance

Due to its limited availability and significant costs and execution times, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is hardly used as a tool for primary cardiovascular prevention. However, its enormous potential allows it to be used in specific settings [Figure 9]. CMR, in fact, allows for the accurate and highly reproducible evaluation of cardiac morphology and function. Furthermore, a characterization of the myocardial tissue is permitted, even without the use of contrast medium. Finally, the evaluation of perfusion and therefore myocardial viability should also be mentioned. Thanks to these characteristics, CMR is now increasingly used in the prevention of SCD in subjects with cardiomyopathies and ischemic cardiopathy, overcoming the known limits of left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) calculated by echocardiography, that doesn’t seem to be the most accurate parameter for arrhythmic risk assessment, especially in nonischemic cardiomyopathies.[54,55,56] In fact, several cardiopathies (i.e. hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and phenocopies, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy) present a substantial arrhythmic risk beside a normal LVEF. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), T1-T2 mapping, and extracellular volume assessment have been reported to add incremental value for arrhythmic assessment across both ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies.[55,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] LGE, as an expression of fibrotic irreversible damage, has been described as a strong predictor of SCD, both considering the extension and the location, i.e. anterior or septal location of the left ventricle.[55,57,58,59,60] Its use as a predictor of SCD risk is now admitted in multiparametric evaluation scores and to guide the indication of implantable cardioverter defibrillator in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.[64,65,66] However, LGE still suffers from limitations, like not being a static phenomenon and because of the lack of a standardized method of evaluation; more, data about its association with the risk of SCD are sometimes conflicting, underlining the need for further studies to obtain solid data.[55] T1 mapping enables the assessment of fibrosis, and its use has been described as a prognostic indicator in patient with ischemic or nonischemic cardiopathy.[62,63] However, the lack of a standardized evaluation method still precludes an extensive use of T1 mapping. A suggested multiparametric method, incorporating the measurement of scar tissue extent, left ventricular end-diastolic volume, and regional wall motion abnormalities, enhances the risk assessment of patients with a history of myocardial infarction.[67] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also essential in the differential diagnosis of various phenocopies in patients with a hypertrophic phenotype, distinguishing between hypertrophic sarcomeric cardiomyopathy and other conditions such as cardiac amyloidosis or Fabry disease. Moreover, cardiac MRI is invaluable in diagnosing myocarditis, a condition that can underlie SCD even in young athletes, highlighting its importance in preventive cardiology. Finally, CMR could also be useful for the evaluation of EAT that, as reported below, plays a role in cardiovascular pathophysiology;[68,69] however, strong data about the role of CMR in EAT evaluation in cardiovascular prevention are missing. In conclusion, CMR is a strong method to overcome the limitations of LVEF in the evaluation of cardiac patients, being able to identify myocardial fibrosis, which is an expression of cardiac damage and one of the most relevant arrhythmic substrates.[66,70]

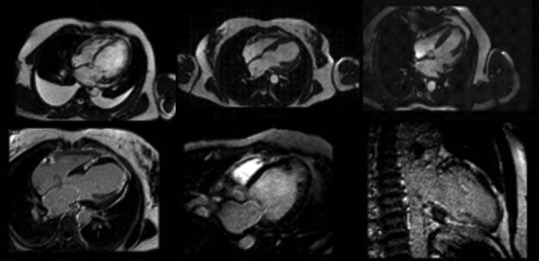

Figure 9.

Cardiac magnetic resonance images showing the adding value in precisely assessing dimensions and function of hearth, late gadolinium enhancement site and extension

EPICARDIAL ADIPOSE TISSUE AND FATTY LIVER

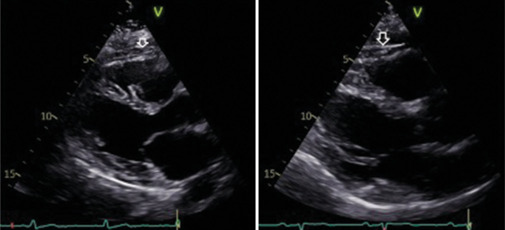

The evaluation of EAT is a new element that seems to correlate with the risk of atherosclerosis. EAT is typically identified as the inhomogeneous hypoechoic formation located between the outer myocardial wall and the visceral layer of the pericardium[6] [Figure 10]. In clinical practice, EAT thickness is most commonly measured utilizing parasternal long-axis views at the end-diastole phase, with a cutoff value of increased EAT considered more than 5 mm.[6,71] Often EAT is limited to the front of the right ventricle, and the measurement is performed perpendicularly along the free wall of the right ventricle. Other authors measured EAT at end-systolic phase, and values have been averaged over three cardiac cycles.[72] The same authors found that the median thickness of epicardial fat was 7 mm in men and 6.5 mm in women among a large cohort of patients who underwent TTE for standard clinical indications.[73] Furthermore, Natale et al. proposed an upper normal limit for EAT thickness of 7 mm, based on data gathered from a study involving 50 healthy volunteers.[74] Other authors suggest that measurements >5 mm during end-diastole could be considered as the cutoff value of increased epicardial fat, but larger studies are missing.[71] As recently described, EAT is independently and linearly associated with coronary artery disease and its severity.[7] Moreover, EAT could have a role in the development of several CVDs as atrial fibrillation[75] or Takotsubo syndrome,[76] through complex mechanisms and could be a potential therapeutic target for novel cardiometabolic medications that modulate adipose tissue.[77,78] Given this, in particular the simplicity of detection, EAT could, therefore, play an important role in cardiovascular prevention and treatment of CVD, both with echocardiogram and with other cardiovascular imaging methods, even with the application of deep learning technologies.[5,69,77]

Figure 10.

Parasternal long-axis echocardiographic images demonstrating epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) thickness. The white arrows indicate the inhomogeneous hyoechoic formation corresponding to EAT, measuring 6 mm (left) and 8 mm (right).

Hepatic steatosis, also known as fatty liver disease, is a condition in which an accumulation of fats is created in the liver. Generally, patients don’t have specific symptoms and so they are unaware of this condition. The most recent literature shows a close connection between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NALFD) and CVDs.[79,80,81,82,83,84] Ultrasound imaging is frequently used to detect steatosis, even if it’s limited because of nonquantitative and subjective assessment. It is not difficult to imagine that NAFLD fits into a metabolic syndrome picture, with various elements acting on the cardiovascular system. Furthermore, NAFLD is associated even with endothelial dysfunction, increased systemic inflammatory tone, and systemic fat deposition: this is the result of an important systemic disturbance in lipid metabolism. Although not standardized, several articles conclude by underlining the importance of a better description of the correlation between NALFD and CVDs, to optimize the prevention strategies for these two conditions.[80,81,82,83] For this purpose, the visualization and description of the liver echogenicity during the subcostal sections of the echocardiogram might be a starting point.

THE ROLE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Due to the huge amount of real-world data about CVD risk factors and prevention, the application of AI on these data could lead to a personalized medicine and tailored primary or secondary prevention strategies.[85] AI techniques could be easily applied to imaging tools, such as CT, echocardiography, and CMR. In echocardiography, LVEF with automatic calculation is an AI-learned pattern that can effectively calculate LVEF.[86] Recently, a group from Japan successfully applied a deep convolutional neural network technology to diagnose regional wall motion abnormalities in patients with a history of myocardial infarction.[87] The automated global longitudinal strain was described as an independent predictor of major cardiovascular events in patients with a history of myocardial infarction.[88] The application of AI in CCTA imaging, that is often time-consuming and requiring semiautomated evaluation, has recently reached brilliant results in accurate and rapid assessment of stenosis, atherosclerosis, and vessel morphology.[89] A recent big multicenter international study on subjects with a wide range of clinical presentations of coronary artery disease that underwent CCTA demonstrated that a deep learning system provides rapid and reliable measurements of plaque volume and stenosis severity; more, this algorithm has showed a potential significance in predicting prognosis of myocardial infarction.[90]

CAC is visible on all CT scans of the chest but is not routinely evaluated. Recently an international group evaluated a deep learning system to automatically quantify coronary calcium on routine cardiac-gated and noncardiac-gated CT of the chest, studied on more than 20,000 individuals from cohorts of asymptomatic and stable and acute chest pain subjects. The study showed that the automated score is a strong predictor of cardiovascular events and is independent by risk factors, demonstrating its clinical value.[91] A study conducted by Eisenberg et al. used a fully automatic deep learning algorithm to qualify EAT volume and attenuation from noncontrast cardiac CT in subject without a history of CAD: this study demonstrated that automated-EAT was associated with an increased risk of major cardiovascular events and so may provide prognostic information in asymptomatic patient, even without additional imaging techniques or human interaction.[92]

A multicenter British group applied AI on CMR and obtained a very interesting result: in fact, in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease, reduced stress myocardial blood flow and myocardial perfusion reserve measured automatically with AI quantification provide a strong and independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.[93] The AI-aided CVD outcome prediction seems to be real and effective on real data, thus helping secondary prevention. AI can also integrate different information at different points in time, creating a personalized patient risk model that is difficult to conceive and implement by a human operator.[86] Even if not directly applied to imaging techniques, the capacity of AI in the prediction of cardiovascular events from the simple reading of ECGs considered normal is sensational.[86,94,95]

We mustn’t forget the limitation of AI, that are actually related to the transparency and fairness of algorithms.[85] The automatic decision-making of AI enables decisions without human interference; the result is more efficient data management but also a more difficult understanding of decisions. This raises a major ethical problem in the application of AI in medicine.

Examples of AI application in CVD prediction models are growing fast and we are experiencing a turning point in recent years. It is likely that the application of AI in this specific field of medicine, with all the limitations and unknowns, will play a primary role that will revolutionize the way of predicting cardiovascular risk and therefore the way of carrying out primary and secondary prevention.

CONCLUSIONS

Cardiovascular imaging plays a crucial role in assessing cardiovascular risk by enabling the refinement of risk stratification across a spectrum of baseline risk levels. The examination of myocardial strain has proven valuable, especially in specific patient subgroups, for detecting early signs of ventricular dysfunction before clinical manifestation. In low to intermediate-risk patients, CT coronary angiography, incorporating the calculation of coronary calcium score, is currently considered the preferred imaging method. The potential discovery of novel risk markers, including through echocardiography, cardiac tomography, and CMR, coupled with the imminent integration of AI, enhances the promise and utility of cardiovascular imaging in the realm of cardiovascular prevention.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, Creager MA, Diehm C, et al. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:2890–909. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276fbcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visseren FL, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3227–337. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perone F, Bernardi M, Redheuil A, Mafrica D, Conte E, Spadafora L, et al. Role of cardiovascular imaging in risk assessment: Recent advances, gaps in evidence, and future directions. J Clin Med. 2023;12:5563. doi: 10.3390/jcm12175563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varadarajan V, Gidding SS, Wu C, Carr JJ, Lima JA. Imaging early life cardiovascular phenotype. Circ Res. 2023;132:1607–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.322054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guglielmo M, Lin A, Dey D, Baggiano A, Fusini L, Muscogiuri G, et al. Epicardial fat and coronary artery disease: Role of cardiac imaging. Atherosclerosis. 2021;321:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacobellis G, Assael F, Ribaudo MC, Zappaterreno A, Alessi G, Di Mario U, et al. Epicardial fat from echocardiography: A new method for visceral adipose tissue prediction. Obes Res. 2003;11:304–10. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meenakshi K, Rajendran M, Srikumar S, Chidambaram S. Epicardial fat thickness: A surrogate marker of coronary artery disease – Assessment by echocardiography. Indian Heart J. 2016;68:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riggio S, Mandraffino G, Sardo MA, Iudicello R, Camarda N, Imbalzano E, et al. Pulse wave velocity and augmentation index, but not intima-media thickness, are early indicators of vascular damage in hypercholesterolemic children. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:250–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirwany NA, Zou MH. Arterial stiffness: A brief review. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:1267–76. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fantin F, Mattocks A, Bulpitt CJ, Banya W, Rajkumar C. Is augmentation index a good measure of vascular stiffness in the elderly? Age Ageing. 2007;36:43–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sequí-Domínguez I, Cavero-Redondo I, Álvarez-Bueno C, Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP, Nuñez de Arenas-Arroyo S, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Accuracy of pulse wave velocity predicting cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2080. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Shlomo Y, Spears M, Boustred C, May M, Anderson SG, Benjamin EJ, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity improves cardiovascular event prediction: An individual participant meta-analysis of prospective observational data from 17,635 subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:636–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zito C, Mohammed M, Todaro MC, Khandheria BK, Cusmà-Piccione M, Oreto G, et al. Interplay between arterial stiffness and diastolic function: A marker of ventricular-vascular coupling. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2014;15:788–96. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandes LP, Barreto AT, Neto MG, Câmara EJ, Durães AR, Roever L, et al. Prognostic power of conventional echocardiography in individuals without history of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2021;76:e2754. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2021/e2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaibazzi N, Rigo F, Facchetti R, Carerj S, Giannattasio C, Moreo A, et al. Differential incremental value of ultrasound carotid intima-media thickness, carotid plaque, and cardiac calcium to predict angiographic coronary artery disease across Framingham risk score strata in the APRES multicentre study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:991–1000. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaibazzi N, Baldari C, Faggiano P, Albertini L, Faden G, Pigazzani F, et al. Cardiac calcium score on 2D echo: Correlations with cardiac and coronary calcium at multi-detector computed tomography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014;12:43. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Restelli D, Carerj ML, Bella GD, Zito C, Poleggi C, D’Angelo T, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: An update on noninvasive multimodal diagnosis. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2023;33:161–70. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_61_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carerj S, La Carrubba S, Antonini-Canterin F, Di Salvo G, Erlicher A, Liguori E, et al. The incremental prognostic value of echocardiography in asymptomatic stage a heart failure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:1025–34. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radmilovic J, D’Andrea A, D’Amato A, Tagliamonte E, Sperlongano S, Riegler L, et al. Echocardiography in athletes in primary prevention of sudden death. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2019;29:139–48. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_26_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barletta V, Fabiani I, Lorenzo C, Nicastro I, Bello VD. Sudden cardiac death: A review focused on cardiovascular imaging. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2014;24:41–51. doi: 10.4103/2211-4122.135611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Salvo G, Di Bello V, Salustri A, Antonini-Canterin F, La Carrubba S, Materazzo C, et al. The prognostic value of early left ventricular longitudinal systolic dysfunction in asymptomatic subjects with cardiovascular risk factors. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:500–6. doi: 10.1002/clc.20933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zito C, Longobardo L, Citro R, Galderisi M, Oreto L, Carerj ML, et al. Ten years of 2D longitudinal strain for early myocardial dysfunction detection: A clinical overview. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:8979407. doi: 10.1155/2018/8979407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanton T, Leano R, Marwick TH. Prediction of all-cause mortality from global longitudinal speckle strain: Comparison with ejection fraction and wall motion scoring. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:356–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.862334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zito C, Manganaro R, Cusmà Piccione M, Madonna R, Monte I, Novo G, et al. Anthracyclines and regional myocardial damage in breast cancer patients. A multicentre study from the working group on drug cardiotoxicity and cardioprotection, Italian Society of Cardiology (SIC) Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22:406–15. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trimarchi G, Carerj S, Di Bella G, Manganaro R, Pizzino F, Restelli D, et al. Clinical applications of myocardial work in echocardiography: A comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2024;34:99–113. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_37_24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahiti F, Morbach C, Cejka V, Tiffe T, Wagner M, Eichner FA, et al. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors on myocardial work-insights from the STAAB cohort study. J Hum Hypertens. 2022;36:235–45. doi: 10.1038/s41371-021-00509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeuchi M, Lodato JA, Furlong KT, Lang RM, Yoshikawa J. Feasibility of measuring coronary flow velocity and reserve in the left anterior descending coronary artery by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography in a relatively obese American population. Echocardiography. 2005;22:225–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0742-2822.2005.04004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciampi Q, Cortigiani L, Zagatina A, Gaibazzi N, Rigo F, Picano E. High resting coronary flow velocity predicts worse survival in chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(Suppl 2) ehac544.080. [doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac544.080] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortigiani L, Gaibazzi N, Ciampi Q, Rigo F, Rodríguez-Zanella H, Wierzbowska-Drabik K, et al. High resting coronary flow velocity by echocardiography is associated with worse survival in patients with chronic coronary syndromes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13:e031270. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.031270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciampi Q, Cortigiani L, Zagatina A, Gaibazzi N, Rigo F, Picano E. High resting coronary flow velocity predicts worse survival in chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2022;43 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.031270. ehac544.080. [doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac544.080] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neves PO, Andrade J, Monção H. Coronary artery calcium score: Current status. Radiol Bras. 2017;50:182–9. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasir K, Cainzos-Achirica M. Role of coronary artery calcium score in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 2021;373:n776. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters SA, den Ruijter HM, Bots ML, Moons KG. Improvements in risk stratification for the occurrence of cardiovascular disease by imaging subclinical atherosclerosis: A systematic review. Heart. 2012;98:177–84. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e563–95. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber LA, Cheezum MK, Reese JM, Lane AB, Haley RD, Lutz MW, et al. Cardiovascular imaging for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2015;8:36. doi: 10.1007/s12410-015-9351-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferencik M, Chatzizisis YS. Statins and the coronary plaque calcium “paradox”: Insights from non-invasive and invasive imaging. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:783–5. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngamdu KS, Ghosalkar DS, Chung HE, Christensen JL, Lee C, Butler CA, et al. Long-term statin therapy is associated with severe coronary artery calcification. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0289111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Ix JH, McClelland RL, Wassel CL, Rifkin DE, et al. Calcium density of coronary artery plaque and risk of incident cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2014;311:271–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadamitzky M, Freissmuth B, Meyer T, Hein F, Kastrati A, Martinoff S, et al. Prognostic value of coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of cardiac events in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:404–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hadamitzky M, Täubert S, Deseive S, Byrne RA, Martinoff S, Schömig A, et al. Prognostic value of coronary computed tomography angiography during 5 years of follow-up in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3277–85. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hadamitzky M, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Berman D, Budoff M, Cademartiri F, et al. Optimized prognostic score for coronary computed tomographic angiography: Results from the CONFIRM registry (COronary CT angiography evaluation for clinical outcomes: An international multicenter registry) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:468–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho I, Chang HJ, Sung JM, Pencina MJ, Lin FY, Dunning AM, et al. Coronary computed tomographic angiography and risk of all-cause mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction in subjects without chest pain syndrome from the confirm registry (coronary CT angiography evaluation for clinical outcomes: An international multicenter registry) Circulation. 2012;126:304–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.081380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Mallah MH, Qureshi W, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, et al. Does coronary CT angiography improve risk stratification over coronary calcium scoring in symptomatic patients with suspected coronary artery disease? Results from the prospective multicenter international confirm registry. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:267–74. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mortensen MB, Blaha MJ. Is there a role of coronary CTA in primary prevention? current state and future directions. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021;23:44. doi: 10.1007/s11883-021-00943-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.SCOT-HEART Investigators. Newby DE, Adamson PD, Berry C, Boon NA, Dweck MR, et al. Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:924–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, O’Brien SM, Boden WE, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munnur RK, Cameron JD, Ko BS, Meredith IT, Wong DT. Cardiac CT: Atherosclerosis to acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2014;4:430–48. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2014.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolossváry M, Szilveszter B, Merkely B, Maurovich-Horvat P. Plaque imaging with CT-a comprehensive review on coronary CT angiography based risk assessment. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7:489–506. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2016.11.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maurovich-Horvat P, Ferencik M, Voros S, Merkely B, Hoffmann U. Comprehensive plaque assessment by coronary CT angiography. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:390–402. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mancini GB, Hartigan PM, Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Hayes SW, Bates ER, et al. Predicting outcome in the courage trial (clinical outcomes utilizing revascularization and aggressive drug evaluation): Coronary anatomy versus ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kishi S, Magalhães TA, Cerci RJ, Matheson MB, Vavere A, Tanami Y, et al. Total coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden assessment by CT angiography for detecting obstructive coronary artery disease associated with myocardial perfusion abnormalities. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lakshmanan S. Cardiac CT, a friend and guide in cardiovascular prevention: Fellow’s voice. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;10:100347. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2022.100347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mele D, Nardozza M, Ferrari R. Left ventricular ejection fraction and heart failure: An indissoluble marriage? Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:427–30. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faganello G, Porcari A, Biondi F, Merlo M, Luca A, Vitrella G, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance in primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2019;29:89–94. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_25_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Licordari R, Trimarchi G, Teresi L, Restelli D, Lofrumento F, Perna A, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance in HCM phenocopies: From diagnosis to risk stratification and therapeutic management. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3481. doi: 10.3390/jcm12103481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gutman SJ, Costello BT, Papapostolou S, Voskoboinik A, Iles L, Ja J, et al. Reduction in mortality from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy patients is dependent on the presence of left ventricular scar. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:542–50. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halliday BP, Gulati A, Ali A, Guha K, Newsome S, Arzanauskaite M, et al. Association between midwall late gadolinium enhancement and sudden cardiac death in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and mild and moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Circulation. 2017;135:2106–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuruvilla S, Adenaw N, Katwal AB, Lipinski MJ, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:250–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.001144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Disertori M, Rigoni M, Pace N, Casolo G, Masè M, Gonzini L, et al. Myocardial fibrosis assessment by LGE is a powerful predictor of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ischemic and nonischemic LV dysfunction: A meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1046–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spieker M, Haberkorn S, Gastl M, Behm P, Katsianos S, Horn P, et al. Abnormal T2 mapping cardiovascular magnetic resonance correlates with adverse clinical outcome in patients with suspected acute myocarditis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:38. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0350-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Z, Sohal M, Voigt T, Sammut E, Tobon-Gomez C, Child N, et al. Myocardial tissue characterization by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging using T1 mapping predicts ventricular arrhythmia in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:792–801. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carrick D, Haig C, Rauhalammi S, Ahmed N, Mordi I, McEntegart M, et al. Prognostic significance of infarct core pathology revealed by quantitative non-contrast in comparison with contrast cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in reperfused ST-elevation myocardial infarction survivors. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1044–59. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, Winkel BG, Behr ER, Blom NA, et al. 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3997–4126. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, Day SM, Deswal A, Elliott P, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2020;142:e558–631. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rowin EJ, Maron MS, Adler A, Albano AJ, Varnava AM, Spears D, et al. Importance of newer cardiac magnetic resonance-based risk markers for sudden death prevention in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An international multicenter study. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19:782–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Di Bella G, Siciliano V, Aquaro GD, Molinaro S, Lombardi M, Carerj S, et al. Scar extent, left ventricular end-diastolic volume, and wall motion abnormalities identify high-risk patients with previous myocardial infarction: A multiparametric approach for prognostic stratification. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:104–11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leo LA, Paiocchi VL, Schlossbauer SA, Ho SY, Faletra FF. The intrusive nature of epicardial adipose tissue as revealed by cardiac magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2019;29:45–51. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_22_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guglielmo M, Penso M, Carerj ML, Giacari CM, Volpe A, Fusini L, et al. DEep learning-based quantification of epicardial adipose tissue predicts MACE in patients undergoing stress CMR. Atherosclerosis. 2024;397:117549. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.117549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guaricci AI, De Santis D, Rabbat MG, Pontone G. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and primary prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy: Current recommendations and future directions. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2018;19:223–8. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eroğlu S. How do we measure epicardial adipose tissue thickness by transthoracic echocardiography? Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:416–9. doi: 10.5152/akd.2015.5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic epicardial fat: A review of research and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iacobellis G, Willens HJ, Barbaro G, Sharma AM. Threshold values of high-risk echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:887–92. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Natale F, Tedesco MA, Mocerino R, de Simone V, Di Marco GM, Aronne L, et al. Visceral adiposity and arterial stiffness: Echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness reflects, better than waist circumference, carotid arterial stiffness in a large population of hypertensives. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:549–55. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ballatore A, Gatti M, Mella S, Tore D, Xhakupi H, Giorgino F, et al. Epicardial atrial fat at cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and AF recurrence after transcatheter ablation. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2024;11:137. doi: 10.3390/jcdd11050137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cau R, Bassareo P, Cademartiri F, Cadeddu C, Balestrieri A, Mannelli L, et al. Epicardial fat volume assessed with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Eur J Radiol. 2023;160:110706. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2023.110706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iacobellis G. Epicardial adipose tissue in contemporary cardiology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:593–606. doi: 10.1038/s41569-022-00679-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Antonini-Canterin F, Di Nora C, Poli S, Sparacino L, Cosei I, Ravasel A, et al. Obesity, cardiac remodeling, and metabolic profile: Validation of a new simple index beyond body mass index. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2018;28:18–25. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_63_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ismaiel A, Dumitraşcu DL. Cardiovascular risk in fatty liver disease: The liver-heart axis-literature review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6:202. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Josloff K, Beiriger J, Khan A, Gawel RJ, Kirby RS, Kendrick AD, et al. Comprehensive review of cardiovascular disease risk in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022;9:419. doi: 10.3390/jcdd9120419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duell PB, Welty FK, Miller M, Chait A, Hammond G, Ahmad Z, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42:e168–85. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Adams LA, Anstee QM, Tilg H, Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its relationship with cardiovascular disease and other extrahepatic diseases. Gut. 2017;66:1138–53. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Del Ben M, Baratta F, Pastori D, Angelico F. The challenge of cardiovascular prevention in NAFLD. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:877–8. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00337-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meyersohn NM, Mayrhofer T, Corey KE, Bittner DO, Staziaki PV, Szilveszter B, et al. Association of hepatic steatosis with major adverse cardiovascular events, independent of coronary artery disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1480–8.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ciccarelli M, Giallauria F, Carrizzo A, Visco V, Silverio A, Cesaro A, et al. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular prevention: New ways will open new doors. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2023;24:e106–15. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun X, Yin Y, Yang Q, Huo T. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular diseases: Diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives. Eur J Med Res. 2023;28:242. doi: 10.1186/s40001-023-01065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kusunose K, Abe T, Haga A, Fukuda D, Yamada H, Harada M, et al. A deep learning approach for assessment of regional wall motion abnormality from echocardiographic images. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:374–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Backhaus SJ, Aldehayat H, Kowallick JT, Evertz R, Lange T, Kutty S, et al. Artificial intelligence fully automated myocardial strain quantification for risk stratification following acute myocardial infarction. Sci Rep. 2022;12:12220. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16228-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Choi AD, Marques H, Kumar V, Griffin WF, Rahban H, Karlsberg RP, et al. CT evaluation by artificial intelligence for atherosclerosis, stenosis and vascular morphology (CLARIFY): A multi-center, international study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2021;15:470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin A, Manral N, McElhinney P, Killekar A, Matsumoto H, Kwiecinski J, et al. Deep learning-enabled coronary CT angiography for plaque and stenosis quantification and cardiac risk prediction: An international multicentre study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4:e256–65. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00022-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeleznik R, Foldyna B, Eslami P, Weiss J, Alexander I, Taron J, et al. Deep convolutional neural networks to predict cardiovascular risk from computed tomography. Nat Commun. 2021;12:715. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20966-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eisenberg E, McElhinney PA, Commandeur F, Chen X, Cadet S, Goeller M, et al. Deep learning-based quantification of epicardial adipose tissue volume and attenuation predicts major adverse cardiovascular events in asymptomatic subjects. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:e009829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.009829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Knott KD, Seraphim A, Augusto JB, Xue H, Chacko L, Aung N, et al. The prognostic significance of quantitative myocardial perfusion: An artificial intelligence-based approach using perfusion mapping. Circulation. 2020;141:1282–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Toya T, Ahmad A, Attia Z, Cohen-Shelly M, Ozcan I, Noseworthy PA, et al. Vascular aging detected by peripheral endothelial dysfunction is associated with ECG-derived physiological aging. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018656. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raghunath S, Ulloa Cerna AE, Jing L, vanMaanen DP, Stough J, Hartzel DN, et al. Prediction of mortality from 12-lead electrocardiogram voltage data using a deep neural network. Nat Med. 2020;26:886–91. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0870-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]