Abstract

Purpose of Review

The global incidence of obesity has risen dramatically in recent decades, with consequent detrimental health effects. Extensive studies have demonstrated that obesity significantly affects the risk, prognosis, and progression of various cancers, including multiple myeloma (MM). As an established modifiable risk factor for both MM and its precursor stages -monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) and smoldering MM (SMM)- the association between obesity and disease onset has become a compelling area of research. This review presents a comprehensive overview of the current epidemiological evidence linking obesity to MM, emphasizing its role in disease pathogenesis and patient outcomes. It also offers insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying this deleterious association, and discusses therapeutic strategies targeting obesity-driven contributions to MM.

Recent Findings

Emerging epidemiological evidence suggests that obesity not only influences MM development but also alters its biological behavior, impacting myelomagenesis, and clinical outcomes. Biologically, multiple pathways exist through which adipose tissue may drive MM onset and progression. Obesity fosters a state of chronic inflammation, where dysfunctional adipocytes and fat-infiltrating immune cells release proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, adipokines, and fatty acids, contributing to the proliferation and expansion of MM. Additionally, communications between MM cells and adipocytes within the bone marrow are crucial in MM biology.

Summary

Collectively, the discoveries described in this review underscore the necessity for broader preclinical and clinical investigations to better characterize the complex interplay between obesity and MM, and to determine whether lifestyle interventions can impact MM incidence and clinical outcomes, particularly in high-risk populations.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, Smoldering multiple myeloma, Obesity, Body mass index, Bone marrow microenvironment, Adipokines

Introduction

Multiple Myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by the uncontrolled expansion of atypical plasma cells within the bone marrow, often resulting in destructive bone lesions, renal dysfunction, anemia, and hypercalcemia [1]. According to GLOBOCAN 2022 data, MM ranks as the second most prevalent blood cancer worldwide, with an estimated 187.952 new diagnoses and 121.388 deaths reported in both sexes worldwide [2]. MM typically progresses from Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS), a precursor stage marked by the existence of monoclonal plasma cells without overt clinical symptoms. The transformation of normal plasma cells into MGUS, and eventually to MM, involves a series of genetic and molecular alterations [3]. These may include dysregulated cell cycle control, evasion of apoptotic pathways, and modifications in the bone marrow microenvironment that facilitate malignant clonal plasma cell growth. Following its initial onset, MM often transitions through an indolent phase known as smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM), during which clonal growth remains relatively slow. Once the clonal load becomes significant, dysfunctional plasma cells may subvert organs, directly or indirectly, through the excessive secretion of monoclonal light chains, leading to widespread tissue damage [4]. Over the past two decades, significant advances in MM therapies have markedly improved median survival rates. Proteasome inhibitors (PIs, i.e. bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib) and immunomodulatory drug (IMiD), along with thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide, have become crucial backbones of treatment combinations [5], along with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) daratumumab, isatuximab, and elotuzumab [6–9]. Moreover, treatment armamentarium is now empowered by novel drugs such as selective inhibitors of nuclear export, selinexor [10], bispecific agents, as teclistamab, talquetamab and elranatamab [10–12] and CAR-T cells [13]. Nevertheless, the disease remains largely incurable. Evidence indicates that obesity and obesogenic behaviors may represent significant and compelling targets for MM prevention. Obesity is one of the limited recognized risk factors for MM and its precursors, including MGUS and SMM, and it is the only identified modifiable risk factor for this neoplasia. Obesity-driven mechanisms, such as chronic inflammation, altered adipokine signaling, and immune dysregulation, play a pivotal part in MM pathogenesis. Therefore, understanding the link between obesity and MM is crucial for identifying strategies to reduce disease incidence and progression.

In this review, we aim to underscore the complex and not yet fully elucidated relationship existing between obesity and MM. First, we will present a comprehensive overview of current epidemiological evidence linking obesity to MM, highlighting its impact on disease pathogenesis and patient outcomes. Furthermore, we will explore the molecular mechanisms by which obesity-associated changes may impact MM biology, focusing on the key actors involved in this harmful association. Lastly, we will discuss therapeutic strategies targeting obesity-driven factors involved in MM development and progression.

Methodology of the Review

A literature search was conducted in Medline/PubMed database (up to April 2025) to obtain relevant material for this review. An investigation was undertaken into the ClinicalTrials.gov website to retrieve data regarding completed or currently ongoing clinical trials. The following keywords were used in various combinations and forms: “multiple myeloma”, “monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance”, “smoldering multiple myeloma “, “overweight”, “obesity”, “body mass index”, “waist-to-hip ratio”, “waist circumference”, “adiposity”, “bone marrow”, “myelomagenesis”, “microenvironment”, “adipocyte”, “adipokines”, “growth factors”, “cytokines”, “hormones”, and similar sentences related to the review topic. Moreover, supplementary articles were identified from the reference lists of selected papers. The inclusion criteria encompassed research articles, observational and experimental studies, meta-analysis, and, in selected instances, reviews that offered valuable insights or unique perspectives not present in primary research published over the past decade. Commentaries, editorials, and articles lacking accessible full text or not published in English language were excluded from the review.

Risk Factors for MM and MGUS

MM represents a multifactorial disease, encompassing several risk factors spanning different aspects of life [14]. Age is one of the most significant risk factors, with the median age at diagnosis being approximately 69 years, and incidence rates increasing sharply with advancing age. MM development is thought to result from the gradual accumulation of genetic mutations over decades, which explains why the disease typically becomes clinically apparent later in life, particularly in individuals without other predisposing risk factors or genetic alterations [15]. Racial background also plays a critical role, since African Americans are more than twice as likely to develop MM compared to white people. This disparity is over threefold among individuals under the age of 50, suggesting that African Americans experience an earlier onset of the disease, on average [16]. Sex is another relevant factor, with men exhibiting a roughly 1.5-fold higher risk than women, although the underlying biological mechanisms remain under investigation [17]. A family history of MM or related plasma cell disorders, such as MGUS, is associated with an elevated risk, suggesting a heritable predisposition. According to the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium, having a first-degree relative with any lymphohaematopoietic cancer, especially MM, further elevates risk, with a stronger correlation observed among men and African Americans [18]. Older age, male sex, black race, family history of MGUS and similar disorders are also non-modifiable factors for MGUS [19]. Additionally, people who were exposed to ionizing radiation (i.e. exposure from nuclear power stations or nuclear bombs), or to certain hazardous agents, including environmental or occupational hazards (i.e. benzene, methylene chloride, xylene, and chemical hydrocarbons) may be at higher risk for developing MM [20]. Chronic antigenic stimulation by infective agents, such as Ebstein-Barr virus [21], and Kaposi Sarcoma Herpes Virus [22] have also been linked with MM. Exposure to asbestos, aromatic hydrocarbons, fertilizers, mineral oils, pesticides and radiation are associated with a significant increase in MGUS development [19]. Furthermore, modifiable factors like anthropometric characteristics, including overweight and obesity, as well as nutrition, have been implicated in MM risk and its progression from MGUS [19, 23]. A large body of evidence suggests that obesity, in particular, plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of MM, further emphasizing the need for continued research into its contribution to disease onset and progression.

Obesity—Definition

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes overweight and obesity as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation correlated to a health risk. Body mass index (BMI), calculated dividing weight by the square of height (kg/m2), is the standard metric used to classify obesity [23]. Specifically, an individual is considered overweight when their BMI falls between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2, while obesity is classified when the BMI reachs or exceeds 30 kg/m2. This condition is further categorized into the three following grades: I, with BMI between 30.0 and 34.9 kg/m2, II, with BMI between 35.0 and 39.9 kg/m2), and III, with BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 [24]. According to these measures, the most recent WHO data indicated approximately 2.5 billion adults worldwide classified as overweight, and more than 890 million as obese individuals. Alarmingly, the global occurrence of obesity has surged threefold over the past forty years and is anticipated to continue increasing in the foreseeable future.

Beyond BMI, WHO recommendations propose waist circumference (WC) and waist-hip ratio (WHR) as better predictors of abdominal obesity, and of obesity-related diseases [25]. A WC ≥ 80 cm for women and ≥ 94 cm for men as well as a WHR (calculated as WC divided by the hip circumference using for both the same units of measurements) above 0.85 for women and 0.90 for men are used as a criterion to classify central or abdominal obesity (WHO Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio Expert consultation 2008). This is because WC and WHR are more reflective of body composition and metabolically active fat deposits, particularly visceral fat, which plays a central role in metabolic and hormonal disturbances (i.e. impaired glucose tolerance, reduced insulin sensitivity, and altered lipid profiles) [26]. On the other hand, BMI does not effectively differentiate between fat mass and lean tissue nor account for adipose distribution. For example, it may overestimate fat levels in highly active individuals and undervalue them in elderly subjects experiencing muscle loss [27]. Despite these limitations, BMI continues to be a widely and convenient tool to assess obesity and evaluate the risk of the associated adverse outcomes.

The Epidemiological Association Between Obesity and MM

The link between obesity and MM began to draw significant attention in the 1990 s with the advent of large cohort studies as a robust method for exploring disease correlations [28]. These early observations were subsequently validated through larger, and more comprehensive studies [29, 30]. Accumulating evidence has now suggested that obesity impacts the risk of of developing plasma cell disorders, including the transformation from MGUS or SMM to MM, as well as in MM mortality [31]. Moreover, various clinical trials have been performed or are currently underway at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. In particular, using “MM”, “MGUS”, or “SMM” as the condition/disease and “Obesity”, “BMI”, “Waist Circumference”, or “Waist-to-Hip Ratio” as additional search terms yielded 25 results. Upon detailed analysis, three of these clinical trials stand out for their focus on the link between obesity and MM. These are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of the studies on obesity and MM at www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Interventions | Status | Eligible criteria, primary outcome and purpose | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05565638 |

Behavioral: Prolonged Fasting Intervention Behavioral: Education Control |

Not Applicable |

Eligibility criteria: patients (≥ 18 years) with documented diagnosis of MGUS or SMM or Smoldering Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia (WM) via EMR review. BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 Primary outcome: changes in body composition assessed via whole body DXA scans, baseline to 4 months Purpose: to understand if fasting for a prolonged nightly fasting (PROFAST) could be helpful to thwart blood malignancy development among overweight and obese subjects |

Not Applicable |

| NCT04920084 | Other: Plant based meals | Not Applicable |

Eligibility criteria: patients (≥ 18 years) with diagnosis of MGUS or SMM. M spike (immunoglobulin) ≥ 0.2 g/dL or abnormal free light chain ratio with augmented level of the proper light chain. Secretory disease. BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 Primary outcome: Weight loss-BMI reduction indicated as the average BMI reduction at 12 weeks Purpose: to assess i) the feasibility of a plant-based diet in overweight MGUS or SMM patients; ii) the effectiveness in MM prevention |

Not Applicable |

| NCT04764695 | Diagnostic Test: D2O dilution technique | Not Applicable |

Eligibility criteria: Children aged 2 to 14 years with leukemia, myeloma and lymphoma diagnosis at any phase of cancer therapy Primary outcome: changes in the fat-free mass (FFM) and fat mass (FM), and hydration status at the enrrollment of the study and 6 months after Purpose: to estimate the body composition and nutritional status of child subjects with hematological malignancies |

Not Applicable |

BMI Body mass index; DXA Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; EMR Nuclear magnetic resonance; MGUS Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; SMM Smoldering multiple myeloma

Increased BMI and Risk of Transformation of MGUS to MM

MM is invariably anticipated by a precancerous stage referred as MGUS. Patients with MGUS exhibit atypical immunoglobulin proteins in their blood or urine without the organ injury or bone disease characteristic of MM. Typically asymptomatic, MGUS is often diagnosed incidentally during routine blood tests performed for unrelated health concerns. This condition impacts roughly 3.2% of adults (> 50 years old), with an estimated 1% progressing to MM annually [32]. Chang et al. reported that MGUS patients with overweight and obesity are at a heightened likelihood of progressing to MM compared to their normal-weight counterparts [33]. Similarly, findings from the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES-RS) showed that increased BMI during midlife significantly correlated with a high risk of progression from MGUS to MM and further lymphoproliferative disorders. Specifically, participants with a midlife BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 (mean age: 53.3 and 52.1 years old for women and men, respectively) exhibited a 2.7-fold greater risk (95% CI: 1.17–6.05) of developing MM and related disorders than healthy individuals [34]. Additionally, a cross-sectional study comparing MGUS (n = 40) to MM (n = 32) patients revealed that MM individuals showed significantly larger abdominal fat cross-sectional areas and increased metabolic activity in adipose tissue [35]. According to existing data, a recent systematic review supports the positive association between increased BMI and MGUS occurrence or MM progression [36]. Interestingly, an ongoing clinical trial (NCT04850846) is investigating whether metformin, which is typically used for weight reduction, metabolic disorders, or obesity-related measures (i.e. BMI and WC) [37], might serve to prevent MGUS or SMM evolution to active MM.

Collectively, this and other accumulated evidence, as outlined in Table 2, indicate that obese patients have an increased risk of progressing from MGUS to MM in respect to non-obese individuals.

Table 2.

List of epidemiological studies associating obesity with MGUS and its transformation to MM

| Author/Year | Study design | Population | Comparison | Number of patients | Findings | Comments/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al. 2017 [33] | Retrospective cohort study | Patients in the U.S Veterans Health Administration database |

UW (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) NW (BMI = 18.5—24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25—29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

7.878 MGUS patients | Increased risk of transformation of MGUS to MM in OW-OB patients versus NW patients |

Use of generic tests to diagnose MGUS Data not representative of the US population Not all patients with a verified diagnosis of MGUS |

| Thordardottir et al. 2017 [34] | Case–control study | Participants from the population-based Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study | Weight (Kg), BMI (kg/m2), percent body fat (%), fat (kg), total body fat (cm2), visceral fat (cm2), subcutaneous fat (cm2), and 2 versions of abdominal circumference (cm), lifetime maximum weight (kg), and measured midlife BMI (kg/m2) |

300 MGUS patients 275 LC-MGUS patients 5.425 controls |

No correlation was observed between the 11 obesity markers and MGUS or LC-MGUS. However, a higher risk of developing MM and other LP diseases from MGUS/LC-MGUS was associated with a high BMI in middle age |

Elevated mean age of the cohort (77 years) Exclusively white individuals included |

| Veld et al. 2016 [35] | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Patients underwent FDG-PET/CT at Massachusetts General Hospital | Weight (kg), BMI (kg/m2), TAT CSA (cm2), TAT metabolic activity (SUV), TAT total metabolic activity (SUV x cm2), VAT CSA (cm2), VAT metabolic activity (SUV), VAT total metabolic activity (SUV x cm2), SAT CSA (cm2), SAT metabolic activity (SUV), SAT total metabolic activity (SUV x cm2) |

40 MGUS patients 32 MM patients |

MM patients exhibited increased abdominal fat CSA and fat metabolic activity versus MGUS patients |

Potential misinterpretation of abdominal fat activity due to peristalsis and respiration Different imaging protocols and equipment |

| Kleinstern et al. 2022 [38] | Cohort study | Patients residing in Olmsted County, Minnesota (USA) |

BMI < 25 kg/m2 BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 |

594 patients with MGUS, with 39 subjects whose condition progressed to MM | High BMI represents a prognostic factor for the progression of MGUS, with a more pronounced relationship in females |

Lack of BMI measurement within two years of screening in 20% of patients Predominance of white individuals Insufficient power for analyses of sex differences in prognostic factors, including BMI and BMI change |

| Thompson et al. 2004 [39] | Case–control study |

Patients at Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota (USA) |

Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 100 MGUS patients with MM progression and 100 MGUS patients who did not progress | Obesity does not impact MGUS progression |

Retrospective study design Small patient cohort |

| Landgren et al. 2010 [40] | Cohort study | Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) women cohort |

BMI = 18–24.99 kg/m2 BMI = 25–29.99 kg/m2 BMI = 30–45 kg/m2 |

1.000 black and 996 white women of similar socio-economic status for MGUS | Obesity was indipendently correlated with an increased MGUS risk, with a twofold excess among black women |

No access to clinical/pathological information of MGUS cases Cross-sectional design limiting temporality assessment and causal inference |

| Landgren et al. 2014 [41] | Cohort study | National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) cohort |

BMI < 25 kg/m2 BMI = 25—30 kg/m2 BMI > 30 kg/m2 |

12.482 adults | A trend toward increased MGUS risk with higher BMI was observed across all racial/ethnic groups, though the association did not reach statistical significance |

Disparity of cytogenetic subtypes between races Racial/ethnic variability in prognosis and progression |

| Chang et al. 2015 [42] | Retrospective Cohort study | Patients in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration database |

UW (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) NW (BMI = 18.5—24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25—29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

2.003 MGUS patients | Metformin use reduced the risk of MGUS progression to MM in diabetics with different BMI |

Asymptomatic nature of MGUS limiting prediction and control Different distributions of follow-up time among metformin users and non-users Exclusion of insulin and sulfonylureas influence Sample not representative of U.S. population, with overrepresentation of males, lower socio-economic groups, and older individuals |

| Boursi et al. 2017 [43] | Case–control study | A database of 11 million UK patients treated by general practitioners | Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

124 MGUS cases with MM progression 760 MGUS patients without MM progression (controls) |

Antidiabetic drugs may have a protective effect against the development of MM among diabetic patients with MGUS with different BMI |

Reduced sample size in diabetes subgroup analysis Inability to assess pathological characteristics of MGUS Inability to assess race Short follow-up period from MGUS diagnosis |

| Schmid et al. 2019 [44] | Cohort study | Prospective population-based Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study | BMI | 4787 partecipants | BMI did not show any association with MGUS |

Absence of urine analysis or imaging Lack of bone marrow biopsy results for MGUS diagnosis and severity details Possibility of overlooked MGUS cases and rare plasma cell dyscrasias |

BMI Body mass index; CSA Cross sectional area; FDG-PET/CT Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography; LC-MGUS Light-chain MGUS; LP Lymphoproliferative diseases; MGUS Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM Multiple myeloma; NW Normal weight; OB Obese; OW Overweight; SAT Subcutaneous adipose tissue; SUV Standardized uptake value; TAT Total abdominal adipose tissue; UK United Kingdom; USA United States of America; U.S. United States; UW Underweight; VAT Visceral adipose tissue

Increased BMI and Risk of MM Occurrence

In an extensive cohort study involving male U.S. military veterans (3.668.486 white and 832.214 black individuals) with an obesity diagnosis between 1969 and 1996, researchers evaluated the hazard of tumor across the main types. MM risk was found to be significantly greater in obese veterans than in their non-obese counterparts (RR: 1.22; CI: 1.05–1.40 for white veterans; RR: 1.26; CI: 1.02–1.56 for black veterans) [45]. A study directed by the University of Oxford’s Cancer Epidemiology Unit examined the association between BMI and the incidence of 17 types of cancer in 1.3 million women with 50–64 years old. Adjusting for confounders (i.e. age, geographic location, socioeconomic background, age at first childbirth, number of births, tobacco use, alcohol intake, physical activity, years post-menopause, and hormone replacement therapy use), the analysis attributed approximately 5% of postmenopausal cancer cases to overweight or obesity. For MM, a significant increase in relative risk (RR: 1.31) was detected for every 10-unit BMI increase [46]. A systematic review and meta-analysis by researchers at the University of Manchester’s School of Cancer Studies assessed the relationship of BMI with 20 cancer types across 221 datasets from 141 studies, including 282.137 incident cancer cases. A slight but significant rise in MM risk was noted for every 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI with RR values of 1.11 in both sexes [47]. Similarly, a multi-institutional European study spanning 30 European countries demonstrated an increasing tumor burden linked to excessive BMI between 2002 and 2008. Notably, MM risk was significantly raised showing an RR of 1.09 (95% CI: 1.01–1.17) in men and 1.11 (95% CI: 1.07–1.15) in women [48]. These findings align with results from a study conducted by the Division of Epidemiology at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, involving 2.000.611 men and women (20–74 years old), with BMI measurements recorded between 1963 and 2001. Assessments of lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative neoplasia risk revealed a significant correlation across BMI categories (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, BMI: 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, BMI: 25–29.9 kg/m2, and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) with an RR increasing from roughly 0.83 to 1.24 and 0.97 to 1.48 in men and women, respectively [49]. On the other hand, a meta-analysis presented that bariatric surgery (BS) in obese patients was linked to a decreased overall cancer incidence (RR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.46–0.84, p < 0.002), and a lower risk of obesity-related cancers (RR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.39–0.90, p = 0.01), with a potential trend toward a reduction in MM incidence (RR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.26–1.11, p = 0.10) [50]. A significantly reduced MM risk in obese patients undergoing BS in respect to the non-surgical cluster (RR: 0.45, 95%CI: 0.23–0.88, P < 0.02) was also reported in a meta-analysis of 2.452.503 obese patients [51]. Therefore, current evidence, summarised in Table 3, underscores that obesity positively affects the risk of developing MM across sexes and racial groups, particularly with sustained high BMI throughout adulthood. However, further research is required to devise effective interventions for promoting weight reduction and reducing the influence of obesity on MM development.

Table 3.

List of main studies associating obesity and MM risk

| Author/Year | Study type | Population | Comparison | Number of patients | Findings | Comments/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samanic et al. 2004 [45] | Cohort study | U.S. male veterans hospitalised for obesity |

Non-OB (BMI < 30 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

3.668.486 whites 832.214 blacks | Obese veterans had a greater MM risk than those of a normal weight |

A lack of data, leading to imprecise analysis of obesity and cancer associations, particularly among black men Incomplete cancer diagnoses due to lack of systematic follow-up No data on confounders Only male population |

| Reeves et al. 2007 [46] | Cohort study | UK women recruited into the Million Women Study |

Reference (BMI = 22.5–24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

1.3 million women | Increased risk of MM in women with a high body mass index |

No information on weight loss in the year before recruitment Only female population Bias of the age range 50–64 |

| Sӧderberg et al. 2009 [47] | Cohort study | Swedish and Finnish Twin Cohort |

Reference (BMI = 22.5–24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

70.067 | Increased risk of MM and other haematological diseases in overweight people compared with normal weight people | Non-differential misclassification of BMI due to changing weight during follow-up |

| Renehan et al. 2010 [48] | Meta-analysis | 30 European countries population |

NW (BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

282.137 | There is a small but important link between a 5 kg/m2 BMI rise and a higher risk of MM, in both sexes |

Impact measures reflecting the shortcomings of the original risk exposure surveys, such as variations in years surveyed, age groups, and data collection methods (e.g. self-report vs. measured) Potentially inconsistent link between body weight and cancer risk across age groups |

| Engeland et al. 2006 [49] | Cohort study | People involved in the Department of Epidemiology at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health |

UW (BMI ≤ 18.5 kg/m2) NW (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) Class I OB (BMI = 30–34.9 kg/m2) Class II OB (BMI = 35–39.9 kg/m2) Class III OB (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) |

2.001.617 (963.653 men and 1.037.964 women) | In both men and women, the risk of lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative neoplasms was significantly associated with higher BMI | Limited control for confounders, like smoking, alcohol, diet |

| Wilson et al. 2023 [50] | Meta-analysis | Adult individuals (> 18 years old), diagnosed with morbid obesity |

Morbid obesity patients not undergoing BS Obese patients undergoing BS |

440.656 patients in the BS cohort 1.658.865 control group | A reduced trend in the risk of developing MM was observed in patients who have undergone BS |

Retrospective cohort studies Presence of confounding factors Healthy user bias: more positive lifestyle changes (e.g. smoking cessation, diet/exercise) after BS Lack of long-term follow-up |

| Wallin et al. 2011 [51] | Meta-analysis | Studies include various populations from different countries and age groups |

Reference (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

15 cohort studies with 10.827 patients with MM and 6.566.684 controls | Patients categorised as overweight or obese had a statistically significant elevated risk of MM |

Variables other than age/sex differed across included studies No treatment adjustment in any trials Results influenced by unknown confounding Variations in study findings due to different BMI definitions |

| Larsson et al. 2007 [52] | Meta-analysis | Studies include various populations from different countries and age groups |

Reference (BMI < 25 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

11 cohort studies with 13.120 MM patients and 4 case–control studies with 1.166 MM patients and 8.247 controls | Overweight/obese patients had a statistically significant higher risk of MM than normal-weight patients |

Recall and selection bias from case–control studies BMI misclassification due to body weight changes during follow-up Failure of individual studies to control for confounders Variations of study results due to differing BMI categorisation |

| Hofmann et al. 2013 [53] | Cohort study | National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort |

UW (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) NW (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI = 30–34.9 kg/m2) Severely OB (BMI ≥ 35.0 kg/m2) |

485.049 participants 489 MM |

Elevated BMI and MM risk earlier in adult life | Measurement error in both the self-report and the measurement of physical activity levels |

| Birmann et al. 2017 [29] | 8 Case control studies | IMMC case–control studies |

NW (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

2.318 MM 9.609 controls |

The strongest MM risk was found among overweight or obese people in both time-use and young-adult periods |

Small numbers in BMI joint analysis categories in early and late adulthood Lack of information on other potentially relevant anthropometric measures Limited statistical power for analyses of non-white strata |

| Marinac et al. 2018 [54] | Cohort study | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), Women’s Health Study (WHS) |

UW (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) NW (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI = 30–34.9 kg/m2) Severely OB (BMI ≥ 35.0 kg/m2) |

153.260 female 49.374 male |

A higher BMI in both later adulthood and young adulthood was associated with a similarly increased risk of MM |

Errors in self-reported weight, height, and activity Homogeneous populations Few established risk factors for MM |

| Marinac et al. 2019 [55] | Cohort study | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) | Measures: weight, height, weight patterns, body shape, waist and hip circumference, outcome ascertainment |

1.21.700 female 51.529 male 582 MM |

A larger body shape, especially after 60, and extreme weight fluctuation are risk factors for MM |

Based on self-reported data for primary exposure variables Number of people with stable weight overestimated Homogeneous populations |

| Blair et al. 2005 [56] | Cohort study | Iowa Women's Health Study population | BMI, weight, WHR, waist, hip circumferences | 37.083 postmenopausal women | Women with higher BMI, weight, WHR and waist and hip circumference had increased MM risk |

Possibly errors in anthropometric measures as they were self-reported Inability to assess confounding by immunological disorders Only women population |

| Britton et al. 2008 [57] | Multicenter prospective cohort study | European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) population |

NW (BMI < 25 kg/m2) OW (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) OB (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) WC (< 102 or ≥ 102 cm in men, and < 88 or ≥ 88 cm in women) WHR (< 0.95 or ≥ 0.95 for men, and < 0.80 or ≥ 0.80 for women) |

371.983 cancer-free individuals 1,219 cancer cases (609 men and 610 women) |

No connection was found between abdominal fat indicators and MM in both genders | Differences in methods used for anthropometric assessment between EPIC centres |

| Bertrand et al. 2022 [58] | Cohort study | Six U.S. prospective cohort studies populations | BMI, WC and predicted fat mass |

544.016 individuals 2756 incident diagnoses |

A 10% increased risk of MM was observed for each 5 kg/m2 increase in usual adult BMI and favourable correlations were identified for early adult BMI, height, WC and predicted fat mass | Potential errors in self-reported measurement |

| Teras et al. 2014 [30] | Cohort study | Population of 20 prospective cohorts in the National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium |

Height (sex-specific categories) Baseline Reference BMI (15.0–18.4, 18.5–20.9, 21.0–22.9 kg/m2) BMI (23.0–24.9, 25.0–27.4, 27.5–29.9, 30.0–34.9, 35.0–59.9 kg/m2) BMI change between early adulthood and baseline WC (10-cm categories) WHR (sex-specific categories) |

1.5 million participants (including 1.388 MM deaths) | The elevated mortality rate observed in MM cases was associated with higher BMI and WC |

Possible errors in self-reported anthropometric data Pooled dataset, including several potential confounders, but not all risk factors (i.e. family history, occupational exposures) Data not generalisable to non-White populations due to the small number of non-White participants |

BMI Body mass index; BS Bariatric surgery; IMMC International Multiple Myeloma Consortium; MM Multiple myeloma; NW Normal weight; OB Obese; OW Overweight; U.S. United States; UK United Kingdom; UW Underweight; WC Waist circumference; WHR Waist-To-Hip Ratio

Increased BMI and Risk of MM Mortality

The American Cancer Society conducted a prospective study, named as Cancer Prevention Study II, involving 900.000 U.S. adults without evidence of cancer at enrollment in 1982. Over 16 years of follow-up, 57.145 cancer-related deaths were recorded. Among participants with extreme obesity (BMI ≥ 40.0 kg/m2), the cancer death rate was 52% greater in men and 62% greater in women than normal weight individuals. Specifically, the RR of cancer death in this cluster was 1.52 (CI: 1.13–1.87) for men and 1.62 (CI: 1.40.1.87) for women. Notably, MM mortality increased significantly with rising BMI, with men and women having a BMI between 29.9 and 39.9 kg/m2 showing an RR of ~ 1.50, and ~ 1.45, respectively [59]. Researchers from the University of Oxford’s Cancer Epidemiology Unit also examined BMI-related mortality risks for 17 cancer types in a cohort of 1.3 million women between 50 and 64 years old in the UK and found a significant trend of increasing MM mortality with rising BMI (RR: 1.50 and 1.45, for men and women with BMI ranging from 29.9 to 39.9 kg/m2, respectively) [46]. A meta-analysis of prospective studies further confirmed these findings, demonstrating a statistically significant rise in MM mortality among overweight or obese subjects as compared with the normal weight category [51]. Findings from the African American BMI-Mortality Pooling Project (spanning 7 prospective cohorts with 239.597 participants) found a statistically significant growing tendency in MM death rates across BMI ranges from 18.5 to < 60 kg/m2, with hazard ratio (HR) peaking at 1.43 [60]. Results on mortality also showed a 16% increased risk of MM per 5 kg/m2 in an update of the WCRF-AICR (World Cancer Research Fund-American Institute for Cancer Research) systematic review of published prospective studies [61]. A significant negative effect of obesity on COVID-19-related outcomes in MM patients was also recently reported [62], further strengthen the link between obesity and increased MM mortality across diverse populations.

Increased BMI and Risk of Relapsed/Refractory MM

Beyond its established effects on MM occurrence and mortality, obesity may also influence several aspects of disease outcomes, including relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM). A retrospective analysis of 13 RRMM clinical trials, including 5.898 patients, found that individuals with a BMI > 25.0 kg/m2 tended to have slightly improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to those having a BMI between 18.5–24.99 kg/m2 [63]. Similarly, a separate prospective clinical trial, involving 331 RRMM patients, showed that a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was associated with better PFS and OS than a BMI < 30 kg/m2 among patients with heavily pretreated MM, despite comparable response rates in the two groups [64]. Further supporting this trend, in a retrospective study of 111 RRMM patients who underwent CAR-T cell treatment, Cheng et al. reported an improved median PFS in overweight partecipants, although no significant differences in OS or duration of response were observed across BMI groups [65]. Moreover, a recent retrospective multicenter study of 267 RRMM patients treated with CAR-T reported that obesity had no significant impact OS, time to progression, or safety [66].

Collectively, these findings suggest the presence of an “obesity paradox” in RRMM, wherein a higher BMI does not appear to negatively affect survival outcomes. This paradox may be partially attributed to greater nutritional and muscle reserves found in individuals with increased BMIs, which may potentially confer a survival advantage for patients who have undergone multiple lines of therapy and/or reduce the impact of disease-related weight loss or cachexia. However, to fully understand the prognostic relevance of BMI in RRMM, further studies incorporating comprehensive body composition parameters (i.e. visceral fat, muscle mass, and fat-to-muscle ratios) are necessary.

Increased BMI and Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

A single-center retrospective study of 142 MM patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AutoHCT) reported that increased BMI at transplant was correlated with worse OS, although no significant association was shown between BMI and PFS in this cohort [67]. Similarly, another study, involving 99 MM patients who underwent autoHSCT, showed that individuals suffering from obesity had significantly poorer outcomes than those with normal body weight, with a 3-year PFS rate of 33% compared to 69% in patients with normal BMI [68]. In contrast, an analysis of clinical outcomes in 1.087 MM patients after AutoHCT demonstrated that obesity had no significant effect on OS, PFS, progression, or non-relapse mortality [69]. Moreover, recent data from a large cohort of patients with MM receiving upfront auto-HCT revealed that a high BMI may not be a limiting factor for auto-HCT eligibility [70], underscoring that the potential implications of obesity in this setting remain an area of investigation that still requires clarification.

Waist Circumference (WC), Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) and MM

Blair et al. investigated the relationship between anthropometric measurements and the occurrence of MM in a prospective, population-based sample of 37.083 postmenopausal women and revealed a superior risk of MM development linked to higher levels of body fat, assessed through weight, weight, BMI, WC and WHR [56]. Within the framework of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), anthropometric parameters were evaluated in a cohort of 371.983 individuals without cancer at baseline. Over an 8.5-year follow-up period, 1.219 newly diagnosed and histologically confirmed cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and MM were identified, affecting 609 males and 610 females. No abdominal fat distribution indicators, including WC and WHR, showed a significant connection with MM in either gender. Nevertheless, based on established thresholds, men with a WC of ≥ 102 cm exhibited a higher likelihood of developing MM than individuals having a WC below 102 cm (RR: 2.03 and 1.50, respectively). Similarly, a WHR above 0.80 was associated with an increased MM risk among women (RR: 1.32) [57]. A study combining information from six prospective cohort studies, encompassing 544.016 participants and 2.756 newly diagnosed cases over a follow-up period of 20 to 37 years, identified a positive association between WC and MM occurrence. Specifically, within a subset of individuals with accessible parameters (n = 895), the HR per 15 cm increase in WC was 1.09 (95% CI: 1.00–1.19) [58]. Malek E. et al. directed a secondary evaluation of BMT CTN 0702, a randomized controlled trial that compared three therapeutic strategies following a single HCT. Their analysis explored the effect of visceral adiposity, assessed through WHR, on clinical outcomes and quality of life in MM patients, and found no notable difference in individuals undergoing HCT [71]. Regarding MM mortality, a pooled analysis was conducted using data from 1.5 million individuals across 20 prospective cohorts in the National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium. An increased risk of MM mortality was found in relation to WC (HR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.10 per 5 cm), whereas WHR was not associated with MM mortality [30].

Although the use of WC and/or WHR may represent an important advance compared to earlier research based only on BMI, additional studies are still required to confirm the impact of visceral obesity on the outcomes of patients with MM at different disease stages or in MM patients undergoing treatments.

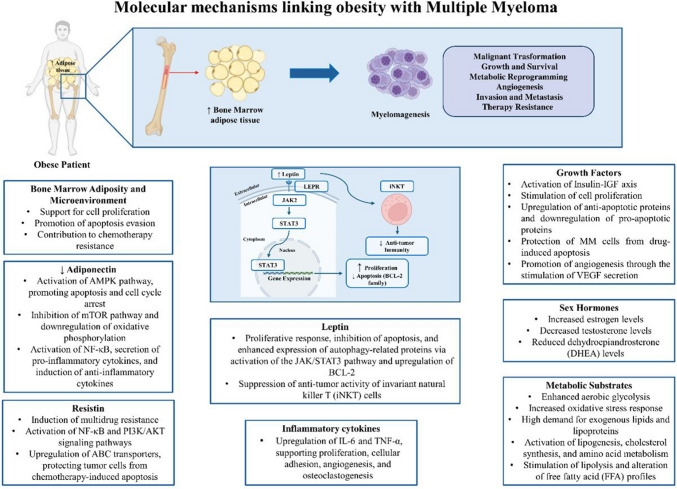

Biological Mechanisms Linking Obesity to MM

Biologically, multiple pathways exist through which adipose tissue may drive MM development and progression (Fig. 1). Obesity creates a state of chronic inflammation, where dysfunctional adipocytes and fat-infiltrating immune cells release proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, adipokines, and fatty acids, contributing to the proliferation and expansion of MM. Additionally, communications between MM cells and adipocytes within the bone marrow (BMAds) might promote MM cell trafficking, autophagy, proliferation, and chemoresistance. Lastly, obesity might enhance the BM environment’s susceptibility to bone disease by encouraging osteoclast differentiation and resorptive activity, further fueling MM cell growth in a self-reinforcing manner [72].

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms linking obesity with MM. Obesity is correlated with crucial local and systemic variations, including different releases of cytokines, adipokines (mainly leptin), growth factors and inflammatory molecules. The intricate interplay across all these alterations might support MM development, progression and drug resistance. BMAds: bone marrow adipocytes; DHEA: dehydroepiandrosterone; IGF: insulin-like growth factor; iNKTs: invariant natural killer T cells; IFN-γ: interferon gamma; JAK2: Janus kinase 2; LEPR: leptin receptor; MM: multiple myeloma; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription

Role of Visceral Adipocytes

Fat tissue functions as an active endocrine organ made up of adipocytes that release various bioactive molecules, including inflammatory cytokines [i.e. interleukin-6 (IL-6)], growth factors [i.e. insulin-like growth factors (IGF)−1 and −2], and adipokines [i.e. adiponectin, leptin, resistin, and adipsin]. These molecules play a crucial role in regulating homeostasis and essential physiological processes [73]. Adipocytes in overweight or obese individuals exhibit a different cytokine profile compared to those in people of normal weight, resulting in higher expression of inflammatory markers and leptin, along with reduced levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines and adiponectin [74]. This heightened inflammatory state is believed to contribute to genomic instability, interfere with DNA repair mechanisms, trigger epigenetic modifications, and influence tumor development and progression [75]. For example, co-culture experiments of human MM cells with adipocytes obtained from patients with varying body weights (ranging from normal to overweight, obese, and severely obese) showed a significant association between BMI and both the adhesion and angiogenic potential of MM cells. Additionally, dysregulation of hormonal, lipid, and signaling factors was detected in adipocytes from obese individuals, potentially influencing MM development and progression [76].

Role of Bone Marrow Adipocytes

Adipocytes are a crucial element of human bone marrow (BM), comprising up to 70% of its volume and representing over 10% of the fat mass among normal weight subjects. This proportion rises in medical settings associated with impaired skeletal or metabolic function [77]. BM adipose tissue (BMAT) is considered a key part of the supportive microenvironment, thought to promote MM progression and its resistance to treatment [78]. Indeed, BMAT may create a favorable ‘soil’ for MM cells to implant and proliferate [79].

The close correlation between BM adipocytes (BMAds) and MM has been demonstrated in clinical specimens, mouse models and “in vitro” co-culture assays. A study of 41 patients diagnosed with MM revealed an enhanced adipocyte dimensions and numbers in the BM when compared to the control groups. Interestingly, levels of adipogenic differentiation-associated genes (i.e. FABP4, adipsin, and PPAR-γ) were higher in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from the same patients expressed than those in the controls [80]. In agreement with these findings, Panaroni et al. reported that patients affected by MGUS/SMM exhibited a significant higher expression of adipogenic markers (i.e. leptin-receptor) compared to healthy donor groups. Furthermore, a human MM cell line (i.e. MM.1S), induced adipocyte differentiation in all BMMSCs derived from both healthy donors and patients. It has been also demonstrated that murine 5 TGM1 and several human MM cell lines (e.g. OPM2, MM.1S, INA6, KMS-12) supported lipolysis and modified fatty acid metabolism in OP9, a pre-adipose cell model derived from murine BMSCs [81]. Morris et al. observed that a murine MM model, the Radl 5 T, which closely mimics human MM, exhibited an increase in BM adiposity in the initial disease phases, with BMAds progressively accumulating at the tumor-bone interface in more advanced stages. Moreover, it was observed that MM cells co-cultured with a BM-derived stromal cell line (ST2), via tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), decreased the expression of adiponectin, an adipokine with antitumor properties, predominantly present in white adipose tissue [82]. “In vitro” evidence showed that in co-culture system MM cells induced the differentiation of MM-MSCs towards BMAds via PPARγ, a key transcriptional factor controlling adipogenesis [80]. On the contrary, Fairfield et al. revealed that patients affected by MM expressed in relation to treatment or stage of disease a reduction in volume fraction as well as in mean size of BMAds. Same changes in adipocyte volume, number and density have been also assessed in BM of different mouse models (BKAL mice harboring 5 TGM1gfp+luc+ model MM cells and SCID-Beige human xenograft bone homing MM.1Sgfp+luc+ mouse model). Furthermore, it has been determined that co-culturing 3 T3-L1 adipocytes, a model employed to avoid the presence of heterogeneous stromal cells or donor-related variability existing in primary samples, or human MSC-derived BMAds with different MM cells, lead to loss of the normal adipogenic functions. Interestingly, adipocytes exposed to MM derived conditioned medium exhibited a senescence-like phenotype and damaged mitochondria. This was accompanied by an altered secretion of IL-6, which is known to sustain MM cell growth [83].

The effects of BMAds in modulating the phenotype of MM cells have been also investigated. Caers et al., in 2007 found that the conditioned media derived from murine 14 F1.1 and human-derived BMAds sustained growth and inhibited apoptosis of MM cells along with augmented migratory capabilities. Furthermore, by analyzing the secretome of BMAds they found a higher expression of several cytokines among which they identified leptin as a potential mediator of MM cell/adipocyte crosstalk [84]. It has been also reported that pre-BMAds and mature-BMAds derived from both healthy donors and MGUS/SMM patients sustained the growth of MM.1S cell lines. Noteworthy, these effects have been demonstrated to be further increased in co-culture experiments between MM cell lines and BMAds isolated from patients [81]. As previously cited, the presence of MM cell lines in BMAds has been demonstrated to result in a decrease in adiponectin levels. This, in turn, resulted in enhanced MM cell proliferation, as well as to their evasion of apoptosis and migration [82]. Wei et al. reported that both MSCs-derived adipocytes isolated from normal and MM patients sustained the proliferation and migration of MM cell lines (XG1 or RPMI 8226). Furthermore, the study revealed that these adipocytes were able to protect MM cells from apoptosis triggered by the chemotherapeutic drug bortezomib [80]. In accordance with these findings, it has been established that BMAds, obtained from human MSCs derived from BM of healthy donors, primarily via the secretion of adipsin and leptin, diminish the response to two different chemotherapeutic drugs (melphan or bortezomib) in MM tumor cells [85]. Besides, it has been demonstrated that CM originating from human MSC-derived BMAds rescue MM cells against the pro-apoptotic activity of dexamethasone, a pharmaceutical agent utilized in the treatment of MM patients, either as a monotherapy or alongside additional agents [83].

All these findings further support the hypothesis that BMAds are pivotal within the BM microenvironment, exhibiting the capacity to deeply influence the biology of MM cells.

Role of Bone Marrow Microenvironment

Tumor cells do not proliferate in isolation; instead, they form close interplay with the surrounding microenvironment, which is vital for their survival and advancement [86]. In contrast to solid tumors, where primary and metastatic sites are usually separate, MM is marked by extensive cancer presence across multiple locations within a single microenvironment: the BM. BM is a multifaceted organ composed of various specialized cell types, each contributing to essential functions like blood cell production, immune response, and maintaining skeletal integrity. The BM microenvironment (BMME) is traditionally divided into distinct niches, including the vascular niche, the endosteal niche, and the immune microenvironment, which functions as a region for specialized immune cells in BM stroma. As a key pathogenic actor in MM, the BM niche holds central importance [87]. While the BMME has been demonstrated to promote tumor growth, cell death resistance, and the movement and localization of cancer cells, its definitive involvement in driving the progression from MGUS and SMM to active MM is still being explored [88]. A known mutual signaling loop exists between MM cells and other cellular components within the BMME. Additionally, the BMME in MM patients shows distinct differences in both cellular and noncellular composition compared to that of healthy people [86]. The BMME contains a variety of cell types, each residing in one of the niches. These can be categorized into hematopoietic cells, including B cells, T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and osteoclasts, as well as non-hematopoietic cells such as BM stromal cells, osteoblasts, and endothelial cells [86]. The progression from asymptomatic MGUS to active myeloma involves both an increased mutational burden and notable shifts in the cellular constitution of the BMME. This shift disrupts immune surveillance, leading to immune exhaustion and suppression within the BMME. Key immunosuppressive cells recruited include MDSCs cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), regulatory B cells (Bregs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [87]. Indeed, obesity alters B cell function by promoting a pro-inflammatory phenotype, which can enhance MM progression through increased IL-6 and TNF-α secretion, contributing to tumor cell survival [89]. T cell dysfunction in this context is characterized by impaired cytotoxic activity and increased exhaustion markers, reducing immune surveillance against MM cells and promoting disease progression [89]. Moreover, obesity-driven metabolic dysregulation negatively impacts NK cell function, leading to reduced cytotoxicity and impaired ability to eliminate MM cells in the BMME [90].

Role of Adipokines

In addition to the effects of BMAT, the abnormal increase of white adipose tissue during obesity promotes the formation of dysfunctional adipose tissue, able to secrete a wide array of different bioactive peptides collectively known as adipokines. To date, over 100 distinct adipokines have been identified, and emerging evidence proposes a role for some of them in MM progression, modulating tumor microenvironment interactions, and influencing treatment outcomes. Table 4 provides a detailed overview of major studies examining the role of the three main adipokines—adiponectin, resistin, and leptin—in the development of MGUS or MM.

Table 4.

List of main studies associating adipokines with MGUS and MM

| Adipokine | Role | Number of patients | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | Tumor-suppressive |

174 MM 348 controls |

Inverse relationship between adiponectin levels and MM risk | Hofmann et al. 2012 [91] |

|

1.269 MM 2.158 controls |

Lower circulating adiponectin levels in MM patients than in controls | Liu et al. 2022 [92] | ||

|

624 MM 1.246 controls |

Reduced MM risk with a high level of adiponectin | Hofmann et al. 2016 [93] | ||

|

84 MGUS 104 SMM 25 MM |

Association between reduced adiponectin expression and progression from MGUS to clinically manifest MM | Hofmann et al. 2017 [94] | ||

|

73 MM 73 controls |

Inverse association between lower serum adiponectin levels and higher MM risk | Dalamaga et al. 2009 [95] | ||

|

23 newly MM 23 controls |

Reduced plasma concentration of adiponectin among men with newly diagnosed MM compared with controls | Reseland et al. 2009 [96] | ||

| Resistin | Unclear |

73 MM 73 controls |

Inverse correlation between serum resistin levels and MM risk | Dalamaga et al. 2009 [95] |

|

178 MM 358 controls |

Slight inverse association between resistin levels and MM risk | Santo et al. 2017 [97] | ||

|

23 newly MM 23 controls |

No difference in resistin concentrations between patients with newly diagnosed MM and controls | Reseland et al. 2009 [96] | ||

|

1.269 MM 2.158 controls |

No significant difference in resistin levels between MM patients and controls | Liu et al. 2022 [92] | ||

|

14 MM 25 controls |

Higher resistin levels in lymphoma patients, but no significant difference in MM patients | Pamuk et al. 2006 [98] | ||

| Leptin | Pro-tumoral |

14 MM 25 controls |

Significant increase in leptin serum levels in MM groups compared to the control group | Pamuk et al. 2006 [98] |

|

23 newly MM 23 controls |

Raised plasma leptin levels in female and male MM patients compared to controls | Reseland et al. 2009 [96] | ||

|

1.269 MM 2.158 controls |

Significantly higher circulating leptin levels in MM patients compared to controls | Liu et al. 2022 [92] | ||

|

62 MM 20 controls |

Significantly higher leptin levels in newly diagnosed MM patients compared to controls, with no increase with disease progression | Alexandrakis et al. 2004 [99] | ||

|

174 MM 348 controls |

No consistent association between MM risk and leptin plasma levels | Hofmann et al. 2012 [91] | ||

|

73 MM 73 controls |

No significant difference in leptin serum levels in MM patients compared with controls | Dalamaga et al. 2009 [95] |

MGUS Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM Multiple myeloma

Adiponectin

Adiponectin, namely ACRP30, apM1, adipoQ and GBP28, is a hormonal molecule uniquely generated by adipocytes and intensely up-regulated in the process of adipogenesis, resulting in one of the most adipocyte-specific markers discovered so far [100]. Nevertheless, in contrast to most hormones and secreted proteins derived from adipose tissue, both adiponectin mRNA and serum concentrations are reduced in obesity [101]. Supporting these observations, studies have found hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes [102]. Furthermore, a more robust negative correlation between adiponectin and fat mass (measured via bioelectrical impedance or CT scans) than between adiponectin and BMI was reported [103]. Obese people exhibit lower concentration of circulating adiponectin than those of normal weight, despite it being primarily secreted by visceral adipose tissue [104]. Decreased adiponectin levels have been linked to the promotion of myelomagenesis in obesity. In a case–control study with 73 MM cases and 73 matched controls, higher adiponectin levels were associated with a lower risk of MM, with odds ratios of 0.44, 0.25, and 0.06 across increasing quartiles of adiponectin (Q2, Q3, Q4). An additional study examined the potential association of circulating levels of total adiponectin, as well as high molecular weight adiponectin, with MM risk in 174 MM patients and 348 controls from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. An inverse correlation with MM risk was found for total adiponectin (highest quartile vs. lowest: odds ratio = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.26–0.93, Ptrend = 0.03) and high molecular weight adiponectin (0.44; 0.23–0.85, Ptrend = 0.01) [91]. Another pooled analysis including seven cohorts within the MM Cohort Consortium (MM cases = 624, individually matched controls = 1.246) demonstrated that higher levels of total adiponectin were linked to a decreased overall risk of MM (highest quartile vs. lowest: odds ratio [OR] = 0.64, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.47–0.85; Ptrend = 0.001). Moreover, adiponectin levels were significantly reduced in patients with SMM and fully developed MM, both overall (16–20% decrease; P = 0.048) and in those with IgG/IgA isotypes (26–28% decrease; P = 0.004). In relation to MGUS subjects, adiponectin levels were found to be significantly lower in those with the higher-risk IgM isotype than in those with IgG/IgA isotypes (42% decrease; P = 0.036) [94]. These data suggest that elevated blood adiponectin levels before diagnosis might offer protection against MM onset.

The proposed biological mechanism behind this inverse link is that adiponectin activates its receptors, which are expressed on both normal and MM cells [105], and subsequently AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). This activation inhibits the mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and downregulates oxidative phosphorylation [106]. Adiponectin also promoted apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in MM cells by activating AMPK pathways [107]. This adipocyte-derived molecule directly impacts the adipocyte to block inflammation, inhibiting lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of nuclear transcription factor κB (NF-κB) and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) and inducing anti-inflammatory cytokine expression (i.e. IL-10 or IL-1 receptor antagonist) [108]. L-4 F, an apolipoprotein peptide mimetic, has been shown to increase serum levels of high-molecular-weight adiponectin in obese mice, enhancing osteoblast activity and consequently bone mass [109]. In MM-bearing mice, L-4 F similarly improved bone disease, decreased tumor burden, and extended survival [107]. However, further studies are surely needed to clarify the role of adiponectin within the BMME in MM pathogenesis.

Resistin

Resistin, initially identified in 2001, was recognized for its activity in inducing insulin resistance and glucose intolerance [110]. In mice, it is released from white adipose tissue, while in humans, resistin is produced by monocytes and macrophages. This adipocyte-related polipetide is highly abundant in BM [111]. Studies have shown that resistin treatment may affect cell proliferation, angiogenesis, the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and metastasis in numerous solid cancers [112–116]. Accordingly, a positive correlation between serum resistin levels and BMI has been reported, with obese individuals revealing higher resistin concentrations [117]. However, data concerning obesity, resistin levels and MM risk are still controversial. One case–control study indicated that increased serum resistin levels were associated with reduced MM risk, and BMI did not modify this significance [95]. A separate nested case–control study including 178 MM patients and 358 matched controls also confirmed these data [97]. The link between low resistin levels and MM risk may reflect a compensatory negative feedback response in the resistin signaling triggered by elevated levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and other cytokines known to boost MM development and progression [95]. In contrast, Reseland et al. observed no significant difference in resistin levels across MM patients and healthy individuals [96], validated in a further analysis (MM patients = 367, controls = 524) [92]. However, the exact relationship between resistin and MM warrants further investigation. On a molecular point of view, it was demonstrated that resistin treatment resulted in multidrug resistance in MM cells [118]. Indeed, treatment of human MM cell lines and primary MM cells isolated from patients’ BM aspirates with recombinant resistin protected tumor cells from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. This protective effect occurs through the activation of the NF-κB and PI3 K/Akt signaling pathways, and enhanced levels of ABC transporters, indicating that this adipokine may be important in inducing MM cell survival and proliferation.

Leptin

Leptin, a 16 kDa multifunctional, neuroendocrine hormone produced by adipocytes in relation to the amount of fat stores, has been extensively implicated in regulating food intake, energy homeostasis, immune responses, and reproductive functions. Increasing evidence indicates that this adipokine binds to its own receptor (LepR or ObR) and activates several signaling pathways (i.e. estrogen, growth factor, and inflammatory cytokine ones) to affect several hallmarks of cancer [119]. The leptin receptor is believed to share both structural and functional similarities with IL-6 receptors [120] and certain hematopoietic growth factor receptors [95], having proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects in T-lymphocytes, leukemic cells, hematopoietic progenitor cells, influencing angiogenesis and stimulating cytokine secretion from T-lymphocytes and monocytes [95, 97]. Studies on leptin levels in MM patients have produced mixed conclusions. In one study, serum leptin levels were higher in MM patients (22.6 ± 14.7 ng/mL) than healthy controls (10.3 ± 7.6 ng/mL) [98]. Another study similarly found elevated leptin levels in newly-diagnosed MM patients as compared to controls [96]. A 2021 meta-analysis of seven studies by Liu et al., which included 406 MM patients and 530 controls, confirmed an increase in concentrations in the MM groups (SMD: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.33–1.41, p = 0.002) [92]. Alexandrakis et al. investigated serum leptin levels in 62 MM patients across stages I, II, and III (per the Durie and Salmon criteria) and found no significant differences in leptin levels by stage, suggesting that increased leptin was not linked to MM progression [99]. In contrast, Hofmann et al., analyzing leptin levels in 174 patients and 348 healthy individuals in the US, found no significant difference between groups (10.01 ± 2.64 ng/mL vs. 9.6 ± 2.71 ng/mL, p = 0.78) [91].

There are different potential mechanisms underlying leptin effects in MM development. A first proposed mechanism includes a significant proliferative response and apoptosis inhibition triggered by leptin. Co-culture experiments between RPMI-8226 MM cells and adipocytes resulted in enhanced proliferation of the MM cells and increased levels of leptin through pSTAT3/STAT-3 signaling [76]. Additionally, using the U266 and H929 cell lines, the researchers noted that leptin stimulated cell growth, and increased the phosphorylation levels of AKT and STAT3; whereas using that JAK/STAT inhibitor AG490, leptin-mediated effects were abrogated [121]. Studies have also demonstrated that leptin induces an up-regulation of BCL-2 levels, while inhibiting caspase-3 activation [121]. Additionally, leptin can enhance autophagic protein content through the JAK/STAT3 signaling in MM cells, thereby exerting an anti-apoptotic effect [85]. Leptin was also proposed as a key modulator of anti-tumor immunity. For instance, invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are reduced in MM [122, 123]. Favreau et al., utilizing an immunocompetent preclinical model that mimics human MM (the murine 5 T33MM model), discovered elevated expression of both leptin and leptin receptors on iNKT cells. Similar findings were observed in MM patients. Moreover, MM cells and leptin collaboratively suppressed the anti-tumor activity of murine and human iNKT cells, and ‘in vivo’ blocking of leptin receptor signaling along with iNKT cell activation enhanced anti-tumor activity, suggesting how leptin axis could serve as a potential treatment target for checkpoint inhibition in MM therapy [124]. The main mechanisms by which leptin impact MM progression are summarized in Fig. 1.

Novel Adipokines

Recent findings on the role of adipokines in bone metabolism have led to the discovery of previously unidentified adipokines over the past decade [125]. Among these, visfatin has emerged as an interesting adipokine found in high concentrations within visceral fat in both humans and mice [126]. Notably, elevated plasma levels of visfatin have been observed during the progression of obesity, indicating a possible link between this adipokine and metabolic dysregulation [127]. Visfatin has been identified as being analagous to a protein previously known as pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF1), or nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), a 52-kilodalton cytokine expressed in lymphocytes [126]. One study reported significant upregulation of PBEF1 in MM cells from a large patient cohort, as well as in MM cell lines and in primary MM cells co-cultured with osteoclasts [128]. Supporting this, another investigation demonstrated that NAD⁺ depletion—either via APO866 treatment or PBEF1 knockdown—significantly impaired the survival and proliferation of MM cells ‘in vitro’, in co-culture systems, and ‘in vivo’, underscoring PBEF1 enzymatic activity as a crucial factor in disease progression [129]. In patients resistant to bortezomib, Cagnetta et al. reported increased visfatin mRNA expression, suggesting its potential role as a prognostic biomarker in MM [130]. Importantly, combining a NAD⁺-depleting agent such as FK866 with bortezomib has shown additive effects in promoting MM cell death and overcoming bortezomib resistance [130].

Chemerin, also referred to as TIG2 or RARRES2, is a recently discovered adipokine implicated in the regulation of inflammation, obesity, adipocyte metabolism, and cancer progression [131, 132]. In a study by Westhrin et al., serum chemerin levels were found to be significantly higher in MM patients compared to healthy individuals, with concentrations positively correlating with disease stage [133]. The same study revealed that chemerin expression was markedly elevated in BMSC and pre-adipocytes relative to primary MM cells. Conversely, MM cell lines exhibited lower chemerin expression levels when compared to primary MM cells, suggesting a differential regulation of this adipokine within the tumor microenvironment.

Apelin is the endogenous ligand of the human apelin-receptor (APJ), a seven-transmembrane receptor related to the angiotensin type 1 receptor [134]. Evidence from the literature indicates that the apelin/APJ signaling axis plays a significant role in tumor development and is associated with poor prognosis across various cancer types [135]. In a comparative study involving 29 MM patients (18 males and 11 females) and 19 healthy controls (13 males and 6 females), plasma apelin levels were found to be significantly elevated in MM patients [136]. This observation aligns with findings in other malignancies, including colon adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, and tumors characterized by increased angiogenesis [137]. These results suggest that apelin may serve as a potential diagnostic biomarker in MM and could contribute to the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying myelomagenesis.

Adropin and Omentin-1, two adipokines released by adipose tissue and known for their roles in metabolic regulation and inflammation [138, 139], have been increasingly studied for their potential roles in the pathophysiology of various malignancies, including—but not limited to—colorectal [140, 141], breast [142–146], prostate [147–149] and endometrial [150, 151] cancers. In these contexts, serum concentrations of these adipokines have been quantitatively assessed in patient cohorts, with findings indicating significant alterations associated with obesity, a well-established risk factor for tumorigenesis [152, 153]. However, despite the increasing interest in the relationship between adipokines, cancer, and metabolic status, a significant gap remains in the literature, as no studies to date have investigated the expression or clinical relevance of adropin and omentin-1 in MM patients.

Role of Inflammatory Cytokines

Obesity is characterized by chronic inflammation, which is marked by elevated release of various inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, C-reactive protein (CRP), and TNF-α [154]. The BMME in individuals with MM exhibits elevated levels of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R), IL-16, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and cytokines stimulated by interferon-γ (IFN-γ) [155], all of which are recognized as supporters of MM development [156–161], acting both as growth factors for MM cells and as enhancers of cellular adhesion. Additionally, further cytokines seem to facilitate processes such as angiogenesis and osteoclastogenesis [162–168], or to contribute to a BM supportive environment [169]. For instance, IL-6 is believed to contribute to drug resistance through the action of epigenetic modulation proteins, enhancing DNA methyltransferase-1 activity, which stimulates p53 methylation and inactivation, thereby allowing MM cells to evade apoptosis [170]. A phase II trial investigating the use of an IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) combined with low-dose dexamethasone in individuals with SMM or indolent MM at high risk of progressing to active MM showed a major improvement in PFS and OS in patients who achieved a high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) reduction of ≥ 40% at six months compared to baseline, compared to those who did not (median PFS: 104 months vs. 11 months; median OS: not reached vs. 7.9 years) [171]. The researchers hypothesized that IL-1Ra could suppress IL-1-induced IL-6 release and MM proliferation, with reductions in hs-CRP indicating effective targeting of the IL-1/IL-6 signaling. Elevated pre-transplant CRP levels (> 8 mg/L, the upper limit of normal) independently predicted worse post-transplant survival in another report involving MM patients undergoing delayed autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), with a hazard ratio of 2.0 (95% CI 1.0–3.8) on multivariate analysis [172]. Additionally, evidence suggests that CRP, by binding and activating FCγ receptors, triggers PI3 K/AKT, MAPK/ERK, and NF-κβ signalings, while inhibiting chemotherapy-induced caspase activation. CRP also acts synergistically with IL-6 to inhibit chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in MM cells [173].

Another notable mediator in this contex is TNF-α. Both TNF-α mRNA and protein expression are reported in MM plasma cells [174]. This cytokine stimulates the expression of adhesion molecules on both MM cells and BM stromal cells, resulting in an enhanced binding between these cells and an increased IL-6 production [175].

Role of Growth Factors

Similar to its role in other tumors, the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system has been shown to be important in MM development and progression [176]. IGF-I functions in the homing of MM cells, attracting them from peripheral blood (PB) into the BMME. After entering in the BM, IGF-I promoted MM cell growth and regulates the expression of apoptosis-related molecules by increasing anti-apoptotic and decreasing pro-apoptotic protein expression, thereby inhibiting drug-induced apoptosis [176]. Additionally, IGF-I promotes angiogenesis by stimulating VEGF release by MM cells, and it contributes to MM-related bone disease by enhancing osteoclast maturation and function [176]. Insulin and IGFs also suppressed dexamethasone-mediated apoptosis, potentially contributing to the preservation of the neoplastic cell population [177]. Nevertheless, the NHANES study, which examined the relationship among different obesity-associated metabolic biomarkers -including C-peptide, insulin, and glucose- and MGUS prevalence, found no significant associations [41]. Also, in a cohort of U.S. veterans with diabetes, the use of metformin for more than 4 years was linked to a 53% decrease in the risk of MGUS advancing to MM, possibly due to its disruption of insulin and IGF receptor pathways [42].

While progressing from an avascular to a vascular stage, MM is characterized by an enhanced density of microvessels within the BM, therefore, another important growth factor is endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [178]. VEGF likely promoted growth and migration of cancer cells expressing VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) in an autocrine way [179, 180]. VEGFRs are predominantly expressed on endothelial cells that surround or infiltrate malignant tissue, while they are not found on vascular cells in the adjacent healthy tissue [181]. These data indicate that VEGF secreted by malignant tumor cells stimulates the expression of VEGFR on endothelial cells during tumor angiogenesis.

The paracrine involvement of VEGF in MM was initially proposed by Dankbar et al., who found that IL-6 stimulation of plasma cells derived from the bone marrow of MM patients resulted in enhanced VEGF secretion [182]. Likewise, VEGF stimulation of endothelial and BM stromal cells triggered a significant, dose-dependent increase in IL-6 secretion, that acts as a growth factor for MM cells and a strong inhibitor of plasma cell apoptosis [183]. Additional cytokines, including TNF-α, have also been involved in regulating VEGF production in MM cells [184]. Furthermore, VEGF plays a crucial role in the development of lytic bone lesions in MM, either directly or indirectly by stimulating TNF-α and IL-1β activity, which in turn activates osteoclasts [185].

Role of Sex Hormones

In obesity, the free fraction of sex hormones, such as estrogen and testosterone, increase partly due to reduced levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) [186, 187]. These sex hormones influence several signalings, likely affecting MM biology. For instance, it has been demonstrated that estrogens support MM progression by increasing the immunosuppressive function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [188]. Additionally, the microtubule-associated serine/threonine kinase family member 4 (MAST4), an estrogen response gene, has been recognized as a critical factor in MM-associated bone disease [189]. A significant biological interaction between sex hormone signaling and pathways related to obesity linked to an enhanced risk of MM was also reported. Indeed, estrogen receptor (ER) and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) expression was found to be positively correlated [190], with estrogen enhancing IGF-IR levels [191], and IGF-I increasing ER sensitivity to estrogen [192]. Estradiol also stimulates cytokine release, such as TNF-α [154]. However, estrogen/MM correlation remains complex. Indeed, it has been shown that activation of estrogen receptors, which are strongly expressed in MM cells, can inhibit interleukin-6-driven MM cell proliferation [193].

Obesity is linked to low circulating total and free testosterone levels in men [194] and reduced testosterone levels are commonly observed in MM individuals [195]. Multiple cross-sectional reports have identified a significantly inverse association between plasma free dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels and anthropometric indicators -such as BMI, body fat mass, and % body fat- in both males and females [196]. Evidence suggests that DHEA directly inhibits MM cell proliferation and reduces IL-6 release by BMME [197], proposing a potential link between reduced circulating DHEA levels in obesity and an elevated MM risk.

Role of Metabolic Substrates