Abstract

Background

Primary headaches mainly consist of headaches such as migraine, tension-type headache (TTH), and cluster headache (CH). There is contradictory data concerning the association between smoking cigarettes and headaches. The objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of an association between smoking and primary headaches.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. PubMed and Scopus were screened up until February 2025. Next, those studies with eligible criteria related to this topic were included in a meta-analysis. To assess risk of bias, the Joanna Briggs Institute tool (JBI) was used. The random effects model was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and smoking prevalence.

Results

There were 2,713 records out of which 37 studies were included in the meta-analysis. 22 out of the 37 included studies had a low risk of bias. The prevalence of smoking in migraine was 20% (95% CI: 16–24) and in migraine with aura (MwA) 27% (95% CI%: 17–27). For TTH, the prevalence was 19% (95% CI: 7–34) and in CH, it was 65% (95% CI: 55–76). The overall smoking prevalence in primary headaches was 32% (95% CI: 8–62). Current smoking was associated with an increased risk of migraine (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.02–1.62, p = 0.034) compared to the group without any headache. Meta-regression revealed that neither age, sex, nor year of publication influenced this result. Current smoking was associated with a decreased risk of TTH (OR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.68–0.89, p < 0.001). No association was observed between current smoking and CH and MwA; additionally, no association was found between former smoking and migraine. Meta-regression could not be conducted for TTH and CH.

Conclusions

Current smoking was associated with an increased risk of migraine and a decreased risk of TTH. There was no association between current smoking and CH despite the fact that over half of CH patients smoked. The influence of electronic cigarettes commonly used these days is not yet explored in primary headaches, despite the wide-spread use of such cigarettes among the young population who are vulnerable to primary headache onset.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s10194-025-02076-2.

Keywords: Lifestyle, Factor, Trigger, Tobacco, Nicotine, Cigarette, Exposure, Vaporize

Introduction

Primary headaches are the most common neurological condition characterized by having a headache as the main symptom without being caused by other diseases. The main types of primary headaches are migraine, tension-type headache (TTH), and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) with the main representative being cluster headache (CH, [1]). The global prevalence of active headaches is significant and may affect up to approximately 52% of subjects worldwide [2]. It is estimated that about 15.8% of people experience headaches every day [3]. Primary headaches and their comorbidities constitute a serious public health burden, generating direct and indirect costs for healthcare systems around the world [4, 5]. Although the exact pathomechanisms responsible for the development of primary headaches are not fully understood, the importance of environmental and lifestyle factors – including tobacco smoking – is postulated [6–8].

There is evidence to suggest that both active and passive smoking may increase the frequency and severity of headaches, especially migraine [9, 10] and cluster headaches [11, 12]. However, the exact relationship between smoking and migraine is not entirely clear due to minor discrepancies in the results of existing studies and the limited available evidence [6]. A similar situation occurs in the case of CH, where many patients with CH are heavy smokers, suggesting a possible link between smoking and the occurrence of CH episodes [13, 14]. In the case of TTH, the role of smoking is even less clear. There are no studies in the literature exploring the association between tobacco use and TTH; however, the overall impact of smoking on vascular health and neurological function suggests that avoiding nicotine may be beneficial in this case as well [15, 16].

Therefore, to synthesize the current gap in the literature, we are performing a systematic review with a meta-analysis. The main objective is to verify the association between smoking and the most common primary headache types, i.e. migraine, TTH, and CH. The secondary aim is to examine the prevalence of smoking in the primary headache population.

Methods

Search strategy and collection process

This systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Medical databases such as PubMed and Medline (Scopus) were searched until the end of February 2025. Three authors (BB, PN, JP) formulated the following key terms in order to find articles related to the main objective of the present study: (“migraine” OR “tension-type headache” OR “cluster headache” OR “primary headache” OR “aura” OR “MwoA” OR “MwA” OR “TTH”) AND (“tobacco” OR “smoking” OR “nicotine” OR “cigarette” OR “smoke” OR “vaping”). Then, the above databases were screened without a timeframe. Initially, abstracts of all identified articles were read independently by the three authors (BB, PN, JP). To reach the final results, the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and selection criteria from “Selection criteria” section were used. Only full-text available studies with eligible criteria were considered for data extraction. In the event of any disagreement between the authors regarding inclusion, a fourth author (MWP) helped resolve the issue via discussion. No automated tools were used in the searching process.

Selection criteria

Before the search process, the inclusion criteria were set: full-text articles in English; original type of studies; headache diagnosis based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) at any version or International Headache Society (IHS) criteria; control group in the included study for association calculation had to be without any other headache diagnosis; patients with primary headache had to be marked in current smokers/former smokers/never smokers or included study had to describe methods used to define smoking such as smoking duration expressed in time range, in pack-years or amount of cigarettes per day; data from the study had to be presented as number of patients in particular groups. Additionally, only cigarette-smoking was considered; other forms of nicotine addiction were excluded. Exclusion criteria included articles such as reviews, letters to the editor, animal studies, conference abstracts, book chapters, duplicates and non-English papers; studies that did not contain precise data about smoking with division into active/past smoking or number of cigarettes per day etc.; studies without exact diagnosis of migraine based on validated criteria – probable migraine was not considered for inclusion; studies where the same register databases of patients were used to create different analyses; studies with missing data; studies where the main focus was on a serious medical condition such as stroke, heart attack, or multiple sclerosis, because smoking has a negative impact on these conditions [17, 18].

Methods to assess risk bias

Risk of bias was assessed independently by the three authors (BB, PN and JP) using a critical appraisal tool, the Joanna Briggs Institute tool (JBI CAT, [19]). After assessment of all publications included in this systematic review by each of the above-mentioned authors, the results were discussed thoroughly and final decisions regarding the assessment of risk of bias were made. In the event of disagreement, a fourth author (HM) resolved problems regarding risk of bias assessment via discussion. Due to the large methodological diversity of the included studies, appropriate JBI checklists assigned to each research design such as case-control, case-series, cohort, cross-sectional, and randomised control trial (RCTs) were used. For cross-sectional studies, eight questions measured the risk of bias; for case-control studies, there were ten questions; in cohort studies, there were 11 questions; case-series studies contained ten questions; and in RCTs, there were 13 control questions. The possible answers on risk of bias questions were “Yes”, “No”, “Unclear”, “Not applicable”. A “low” risk of bias was considered if a cross-sectional study received ≥ 6 times “yes” answers, ≥ 7 times “yes” in case-control and case-series articles, 8 ≥ times “yes” in cohort studies, and ≥ 9 times “yes” in RCTs. A “high” risk of bias was noted if cross-sectional studies received ≤ 3 times “yes” answers, case-control and case-series studies received ≤ 4 times “yes” answers, cohort studies ≤ 5 times “yes” answers, and there were ≤ 6 times “yes” answers in RCTs. A “moderate” assessment was given if studies scored between the described ranges.

Meta-analysis

The data from the included studies was extracted to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, 2010 version, USA). Results aggregation was performed in the JASP program (Jeffreys’s Amazing Statistics Program, JASP Team, version 0.19.3), and the ’metafor’ script of the R language environment (R version 4.3.1) was used to create a forest plot of prevalence. Heterogeneity was assessed by calculating the Cochran Q statistic and using an I2 test. Considering the diversity of the collected studies, random effect models were selected in the meta-analyses. The adopted measure of final effect was the odds ratio (OR) corresponding confidence intervals (CI). In order to detect a possible publication bias, the symmetry of funnel plots was analyzed using the trim-and-fill method, and the Egger test was also used. In order to assess the extent to which the assumptions of the meta-analysis and the included studies influenced the obtained total results, a sensitivity analysis was also performed. In all statistical tests, a p < 0.05 value was considered significant. Meta-regression was used to assess the extent to which various moderating variables (age of the study participants, percentage of females in the study group and year of publication) impacted on the results.

Results

Study inclusion

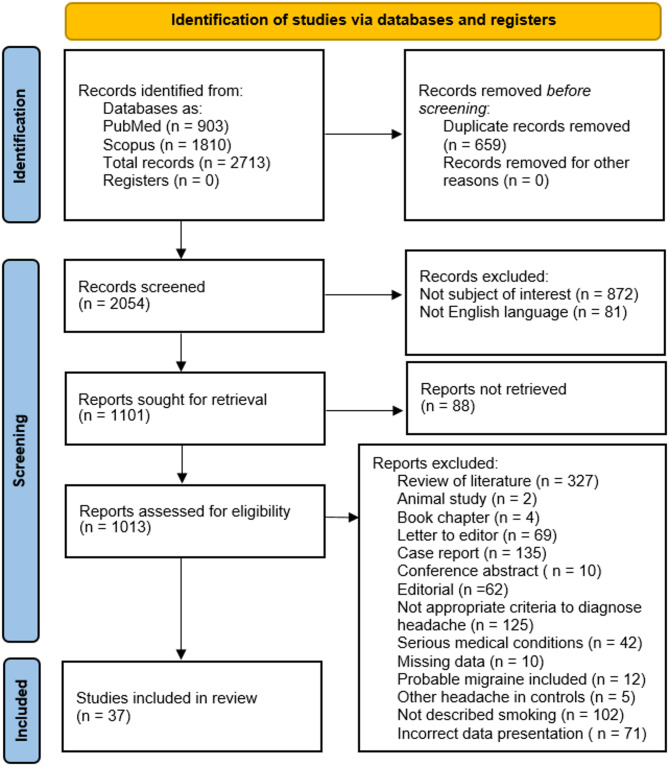

There were 2,713 search results in PubMed and Scopus. Of these 2,713 papers, there were 659 duplicates. After the duplicates were removed, the remaining 2,054 were screened by abstract and title. Next, there were 81 non-English studies, and 872 were articles not relevant to the subject of our study. Among the remaining 1,101 articles, 88 were not available to be retrieved. Of the potentiall eligible reports, there were 327 reviews, two animal studies, 4 book chapters, 69 letters to editors, 135 case reports, ten conference abstracts, and 62 editorials. In the rest of the articles, there were other reasons for exclusion such as inappropriate criteria for headache diagnosis (125 articles); in 42 papers, headache diagnosis and smoking data were for serious medical conditions; in ten, there was missing data; in 12, probable migraine diagnosis was conflated with migraine diagnosis; in five, control groups contained other types of headaches; in 102, smoking was not described according to inclusion criteria; 71 articles presented data incorrectly. Finally, 37 studies were included in the presented systematic review. Details of the steps in the selection process are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram

Study characteristics

Thirty-seven studies were included, and these came from many countries; that is, one from Egypt [12], two from the Netherlands [20, 21], eight from the USA [22–29], two from Brazil [30, 31], two from South Korea [32, 33], four from Italy [34–37], three from Taiwan [38–40], two from Turkey [41, 42], two from China [43, 44], two from Germany [45, 46], and individual reports was from Iran [47], France [48], Norway [49], Spain [50], Syria [51], Greece [52], Ukraine [53], Denmark [54], and India [55]. The studies involved 24,502 participants. The most common methods to diagnose headache were ICHD criteria. Smoking was assessed in different ways, such as interview, questionnaire, or both methods combined. Different categories of smoking were utilized in the studies such as active smokers, former smokers, and never-smokers; current smokers, former smokers, and never-smokers; all smokers, current smokers, and past smokers. Some studies provided additional smoking group characteristics including amount (defined as cigarettes per day or packets or packyears), duration (years of smoking or packyears) or smoking group categorization such as mild, moderate, or heavy smoking. Twenty-seven of the 37 studies described migraine [20–23, 25–31, 33, 35–39, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47, 49, 50, 53, 55], five studies showed MwoA and MwoA [21, 35, 39, 42, 49], four studies examined smoking in TTH [30, 40, 46, 52], and nine studies were about smoking in CH [12, 24, 32, 34, 36, 40, 43, 48, 54].

Twenty-two out of 37 studies contained comparison groups marked as “control group” besides groups with primary headaches [20, 21, 26–32, 34, 35, 39, 41, 44, 45, 47, 49–52, 54, 55]. However, in seven out of these 22 studies, comparison group was not clearly described as patients without any headache or there was just presented as the control group involving patients with other types of headaches (primary or secondary), therefore in order to avoid potential bias risk of mixing patients with other headaches and patients without any headaches, only prevalence of smoking in primary headaches was extracted from these 7 articles [20, 26, 29, 31, 47, 50, 51]. Additionally, if covariates such as age, sex, year of publications needed for meta-regression in calculation of association between smoking and primary headaches could not be simply extracted, this study was only involved in the prevalence estimation [42, 45]. Finally, 14 studies were used to estimate the association between primary headaches and smoking [21, 27, 28, 30, 32, 34, 35, 39, 41, 44, 49, 52, 54, 55]. From all 37 studies [12, 20–33, 35–50, 52–55], the prevalence of smoking was calculated. The described study characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the studies included in this paper

| No. | Author | Study type | Country | Year of publication | Criteria used to assess headache | Age of study population | Type of headache | Headache subjects | Method used to assess smoking | Smoking group characteristic in patients with primary headaches (e.g. current smokers/former smokers/never smokers) and smoking measurement method used in included studies (e.g. smoking duration expressed in time range or in pack-years, amount of cigarettes per day) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers | Nonsmokers | Total number of subjects | ||||||||||

| 1. | Hamdy et al. [12] | Cohort | Egypt | 2024 | ICHD-3 | Mean age: 42.08 ± 10.93 (20–66) | Cluster | 144 | 28 | 172 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Smokers -Non-smokers Smoking measurement: Smoking was definied as -Smoking index -Smoking duration -Average cigarettes/day -Age at onset of smoking -History of exposure to smoking during childhood |

| 2. | Al-Hassany et al. [20] | Crss-sectional | Netherlands | 2024 | ICHD-2 | Median age (IQR): 62.2 (55.5 − 72.8) | Migraine | 159 | 926 | 1085 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers -Former smokers Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as pack-years |

| 3. | True et al. [22] | Cohort | USA | 2024 | ICHD − 3 beta | Mean age (SD): 43.1 (12.15) | Migraine | 188 | 1612 | 1800 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers Smoking measurement: -None |

| 4. | Belitardo de Oliveira et al. [30] | Cohort | Brazil | 2024 | ICHD − 2 |

Mean age (95%CI): TTH: 48.6 (48.3–48.8) Migraine: 47.3 (46.9–47.7) |

Migraine | 142 | 843 | 985 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers Smoking measurement: -None |

| TTH | 453 | 3239 | 3692 | |||||||||

| 5. | Kim et al. [32] | Cross-sectional | South Korea | 2024 | ICHD − 3 and ICHD − 3 beta | Mean age ± SD: 37.8 ± 9.6 | Cluster | 186 | 237 | 423 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers Smoking measurement: -None |

| 6. | Cho et al.[33] | Cross-sectional | South Korea | 2024 | ICHD-3 | Age at baseline, n (% of whole included population): 20–29 y.o.: 34 (5.1); 30–39 y.o.: 44 (6.4); 40–49 y.o.: 60 (7.3); 50–59 y.o.: 32 (3.8) | Migraine | 36 | 134 | 170 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers Smoking measurement: -None |

| 7. | Silvestro et al. [34] | Cross-sectional | Italy | 2021 | ICHD − 3 | Median age (IQR): 40 (36–43.5) | Cluster | 15 | 5 | 20 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as > 15 cigarettes/day |

| 8. | Wang et al. [38] | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | 2023 | ICHD − 3 | Mean age ± SD: 41.7 ± 13.9 | Chronic migraine | 56 | 564 | 620 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current tobacco use Smoking measurement: -None |

| 9. | Liampas et al. [52] | Case-control | Greece | 2021 | ICHD − 3 | Mean age ± SD: 46.0 ± 11.6 | TTH | 14 | 16 | 30 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Smoker -Never smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as active smoker or quit less than 1 year ago |

| 10. | Delva et al. [53] | Cross-sectional | Ukraine | 2022 | ICHD − 3 |

Median age (Q1-Q3) in two groups: Fatigue 34 (24–41) No-fatigue 27 (25–37) |

Migraine | 19 | 66 | 85 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Non-smoker -Current smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as smoking regularly for the last 1 year |

| 11. | Yin et al. [39] | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | 2021 | ICHD − 3 | Mean age ± SD: 36.7 ± 12.0 | Migraine with aura | 67 | 364 | 431 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Ever smoker (current/former) -Current smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| Migraine without aura | 100 | 726 | 826 | |||||||||

| 12. | Lipton et al. [23] | Cross-sectional | USA | 2020 | ICHD-3 | Mean age (SD): 44.8 (13.4) | Migraine | 704 | 3997 | 4701 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Not current smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| 13. | Lund et al. [54] | Case-control | Denmark | 2019 | ICHD-2 | Mean age (SD): 46.2 (11.5) | Cluster headache | 193 | 207 | 400 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers -Former smokers Smoking measurment: -Smoking was definied as pack-years of ever smokers |

| 14. | Rozen [24] | Case-series | USA | 2018 | ICHD-3 | Data not provided | Cluster headache | 8 | 2 | 10 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| 15. | Chaudhuri et al. [55] | Case-control | India | 2016 | ICHD-3 beta | Mean age ± SD: 45.1 ± 8.9 | Migraine | 39 | 261 | 300 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Nonsmoker (including ex-smokers and occasional smokers) Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as daily smoking |

| 16. | Monteith et al. [26] | Cohort | USA | 2015 | ICHD-2 | Age at baseline, n (% of whole included population): <60 y.o.: 77 (29); 60–69 y.o.: 97 (37); 70–79 y.o.: 67 (26); 80+ y.o.: 21 (8) | Migraine | 35 | 227 | 262 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Never smoker -Former smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| 17. | Gür-Özmen and Karahan-Özcan [41] | Case-control | Turkey | 2016 | ICHD-2 |

Mean age (SD): TTH: 36.5 (10); Migraine: 35.05 (9) |

TTH | 17 | 153 | 170 | Questionnaire and interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Nonsmoker (including ex-smokers and never smokers) Smoking measurement: -None |

| Migraine | 31 | 139 | 170 | |||||||||

| 18. | Jahromi et al. [47] | Cross-sectional | Iran | 2013 | ICHD-2 |

Mean ± SD Age (year): 38.4 ± 11.1 |

Migraine | 8 | 261 | 269 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Active smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as smoking in past 6 month |

| 19. | Xie et al. [43] | Cross-sectional | China | 2013 | ICHD-2 | Data not provided | Cluster headache | 14 | 12 | 26 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Nonsmoker -Ex-smoker -Current smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as years of smoking (three ranges: <10; 11–20; >20) |

| 20. | Sacco et al. [35] | Case-control | Italy | 2014 | ICHD-2 |

Mean age ± SD: MwoA: 37.0 ± 9.3 MwA: 35.8 ± 9.8 |

Migraine without aura | 14 | 36 | 50 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Active smokers Smoking measurement: -None |

| Migraine with aura | 17 | 33 | 50 | |||||||||

| 21. | Leroux et al. [48] | Cross-sectional | France | 2013 | ICHD-2 | Mean age ± SD: 40.4 ± 11.3 | Cluster headache | 103 | 36 | 139 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers -Nonsmokers -Not available Smoking measurement: -None |

| 22. | Lambru et al. [36] | Case-control | Italy | 2010 | ICHD-2 | Mean age ± SD: CH: 18.7 ± 11.7; MwoA: 17.9 ± 10.1 | Cluster headache | 150 | 50 | 200 |

Questionnaire (filled in by the physician) |

Smoking group characteristic: -Mild tobacco intake -Moderate tobacco intake -Heavy tobacco intake -Non-smokers Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as amount ranges: mild (1–15 cigarettes/day), moderate (16–24 cigarettes/day) and heavy (> 25 cigarettes/day) |

| Migraine | 89 | 111 | 200 | |||||||||

| 23. | Winsvold et al. [49] | Cohort | Norway | 2013 | ICHD-1 |

Median (quartiles): MwoA: 41 (34, 48); MwA: 40 (32, 48) |

Migraine with aoura | 88 | 210 | 298 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoking Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as current daily smoking |

| migraine without aura | 441 | 1165 | 1606 | |||||||||

| 24. | Rozen [25] | Cross-sectional | USA | 2011 | ICHD-2 | Not provided | Migraine | 23 | 94 | 117 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -All smokers -Current smokers -Past smokers Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as smoking continuously for at least 1 year during patients lifetime |

| 25. | Lopez-Mesonero et al. [50] | Cross-sectional | Spain | 2009 | ICHD-2 | Age rangeof participants: 19–26 years | Migraine | 17 | 41 | 58 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smokers Smoking measurements: -Smoking was definied as two group divided by amount per day: >10 cigarettes per day and < 10 cigarettes per day |

| 26. | Peterlin et al. [27] | Cross-sectional | USA | 2010 | ICHD-2 | Mean age (SD): 38.9 (12.9) | Migraine | 79 | 172 | 251 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Former smoker -Never smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| 27. | Benseñor et al. [31] | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 2010 | ICHD-2 | Mean age (SD): 70.6 (5.25) | Migraine | 48 | 117 | 165 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Former smoker -Never smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| 28. | Straube et al. [45] | Cross-sectional | German | 2010 | ICHD-2 |

Different mean age for each study population: -Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) population: EM: 50.1 CM 61.0 -Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) study population: EM: 50.0 CM 60.8: - Dortmund Health study population: EM: 47.5 |

Migraine | 89 | 320 | 409 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Active smokers Smoking measurement: -None |

| 29. | QiHong et al. [44] | Cross-sectional | China | 2009 | ICHD − 2 | Mean age (SD): 29.2 (8.2) | Migraine | 96 | 233 | 329 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as over 5 years, above 15 packs/month |

| 30. | Tietjen et al. [28] | Cross-sectional | USA | 2007 | ICHD − 2 |

Mean age ± SD: 37.6 ± 10 Range: 18–62 |

Migraine | 39 | 132 | 171 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Ever smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| 31. | Scher et al. [21] | Cross-sectional | Nederland | 2005 | ICHD-1 | Adjusted mean (Standard error): 41.9 (0.4) | Migraine | 229 | 391 | 620 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Never smokers -Ex-smokers Smoking measurement: -Smoking status was definied as occasional (1 cigarette/day), light (1 to 19 cigarettes/day), heavy (20 cigarettes/ day) |

| 32. | Misakian et al. [29] | Cross-sectional | USA | 2003 | ICHD − 1 | Mean age (SD): 55.2 (6.2) | Migraine | 218 | 1691 | 1909 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Past smoker -Never smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

| 33. | Martini et al. [51] | Cross-sectional | Syria | 2025 | ICHD-3 | Mean age ± SD: 25.941 ± 6.58 | Migraine | 52 | 467 | 519 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Non-smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking status was categorized as packet per day or 2 packets per day and hookah smoking |

| 34. | Dinia et al. [37] | Cohort | Italy | 2013 | ICHD-2 | Mean years ± SD Two groups: with white matter lesion − 49.1 ± 12.9;without white matter lesion − 40.0 ± 12.2 | Migraine | 10 | 31 | 41 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Smoker -Non-smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as ≥ 5 cigarettes per day |

| 35. | Celik et al. [42] | Cross-sectional | Turkey | 2005 | ICHD − 1 | Mean age (SD): 34.59 (10.81) | Migraine | 27 | 50 | 77 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Non smoker Smoking measurement: -Smoking was definied as < 20 cigarettes/day and > 20 cigarettes/day |

| 36. | Lin et al. [40] | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | 2004 | ICHD − 1 | Age mean ± SD (range): 39.2 ± 12.2 (18–84) | Cluster headache | 61 | 43 | 104 | Questionnaire |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker -Non-smokers -Ex-smokers Smoking measurement: -None |

| 37. | Steiner et al. [46] | RCT | Germany | 2003 | ICHD − 1 |

Mean age (SD) in five different studied groups: Acetylsalicylic acid 500 mg: 39.9 (11.8) ASA 1000 mg: 41.0 (12.3) Paracetamol 500 mg: 39.7 (11.4) Paracetamol 1000 mg: 38.4 (11.8) placebo: 40.6 (11.4) |

TTH | 124 | 418 | 542 | Interview |

Smoking group characteristic: -Current smoker Smoking measurement: -None |

Abbreviations: ICHD International classification of headache disease, second and third versions, IHS International, headache society, TTH tension-type headache, CH cluster headache, EM episodic migraine, CM chronic migraine, SD standard deviations, IQR interquartile range, RCT randomized controlled trials

Smoking prevalence in primary headaches

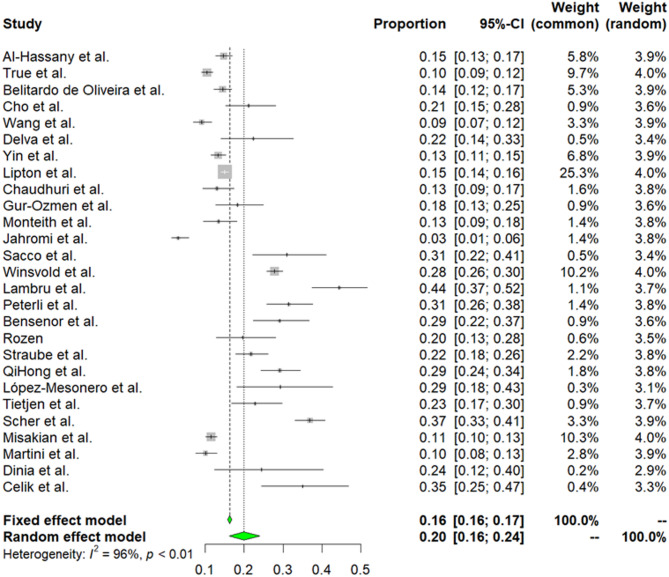

Twenty-seven studies embracing 18,574 participants contained data about current smoking and migraine [20–23, 25–31, 33, 35–39, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47, 49, 50, 53, 55]. Due to high heterogeneity among selected articles (I2 = 96%, p < 0.01), random effect model was used to estimate prevalence. The weighted-pooled prevalence of smoking in migraine was 20% (95% CI: 16–24). This result is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The prevalence of smoking in migraine

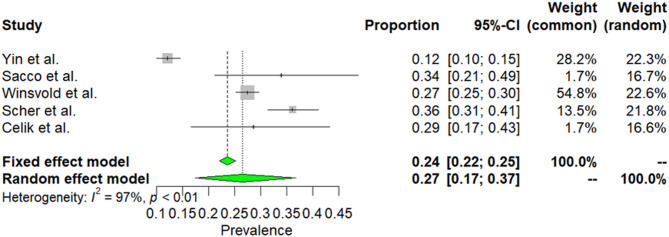

Five studies with 999 patients were focused on patients with MwA [21, 35, 39, 42, 49]. Due to high heterogeneity among selected articles (I2 = 97%, p < 0.01), random effect model was used to estimate prevalence. The weighted-pooled prevalence of smoking in MwA was 27% (95% CI%: 17–27). This result is presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The prevalence of smoking in MwA

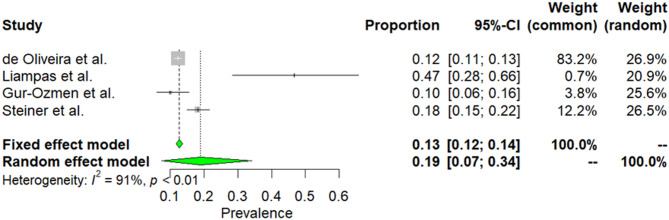

Four studies embraced 4,434 patients with TTH [30, 40, 46, 52]. Due to high heterogeneity among selected articles (I2 = 91%, p < 0.01), random effect model was used to estimate prevalence. The weighted-pooled prevalence of smoking in TTH was 19% (95% CI: 7–34). This result is presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The prevalence of smoking in TTH

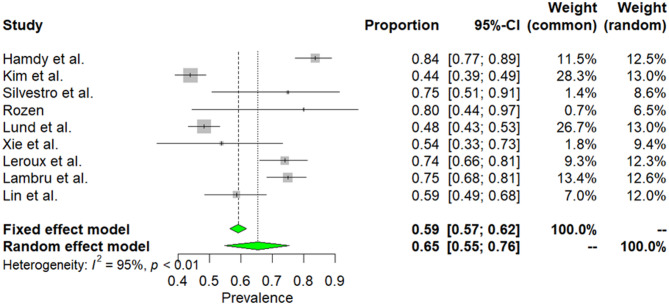

Nine studies was conducted in 1,494 patients with CH [12, 24, 32, 34, 36, 40, 43, 48, 54]. Due to high heterogeneity among selected articles (I2 = 95%, p < 0.01), random effect model was used to estimate prevalence. The weighted-pooled prevalence of smoking in CH was 65% (95% CI: 55–76). This result is presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The prevalence of smoking in CH

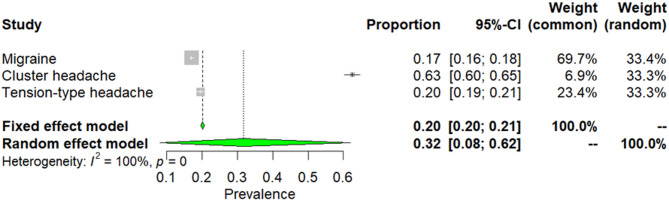

In summary, from 37 included studies there were pooled-prevalence of smoking calculated embracing 24,502 patients with headaches. Due to high heterogeneity among selected articles (I2 = 100%, p = 0), a random effect model was used to estimate prevalence. The weighted-pooled prevalence of overall smoking in primary headaches was 32% (95% CI: 8–62). This result is presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The overall prevalence of smoking in primary headaches

Association between smoking and primary headaches

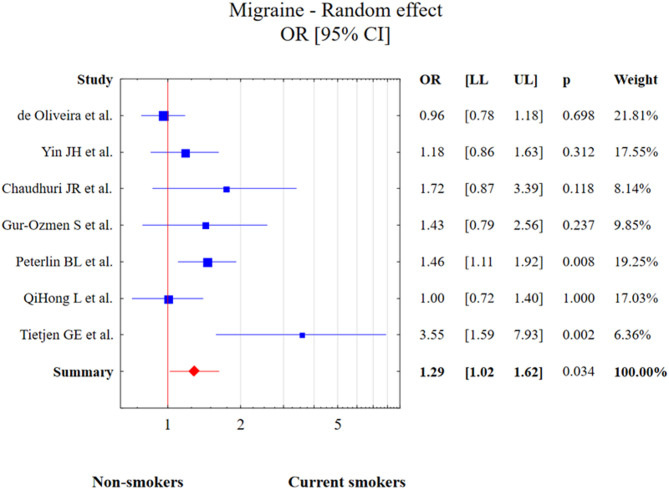

Seven studies had migraine groups which involved 3,463 patients and groups of patients without any headache which were described as control groups. The test of heterogeneity was Q = 15.7, df = 6, p = 0.015, I2 = 69.1%. However, the tunnel graph analysis from Figure S1 (supplementary material) as well as the results of Egger’s test (p > 0.05) indicate a lack of any statistically significant publication bias. Current smoking was associated with increased risk of migraine diagnosis in comparison to the control group (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.02–1.62, p = 0.034). This result is presented in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The meta-analysis results of current smoking and migraine in comparison to control patients. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

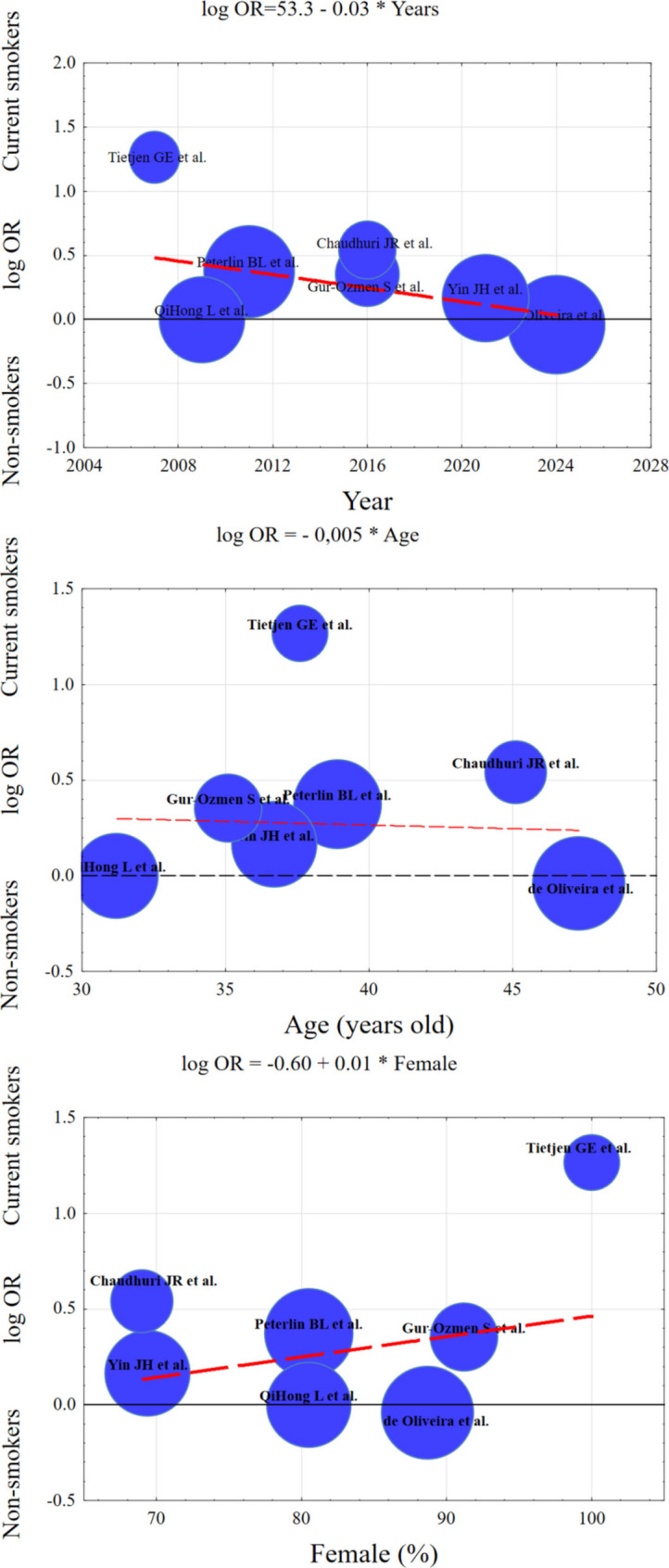

Meta-regression was performed to consider the influence of three moderators on the effect of the meta-analysis. The result indicates that none of the factors (i.e. age, gender and year of publication) is a significant predictor of migraine (p > 0.05). Although the effect size decreases in more recent publications (b = -0.040), increases with more women in the migraine group (b = 0.012) and decreases with age (b = -0.008), these coefficients do not differ significantly from the zero value (p > 0.05). These results are summarized in Table S1 in the supplementary materials. The three bubble plots in Fig. 8 visualize the predicted effects of the moderators (year of publication, mean age of the study participants, and the proportion of women in the study) along with the effect size estimates and confirm that the effect of these moderators is nonsignificant.

Fig. 8.

The bubble plots of meta-regression

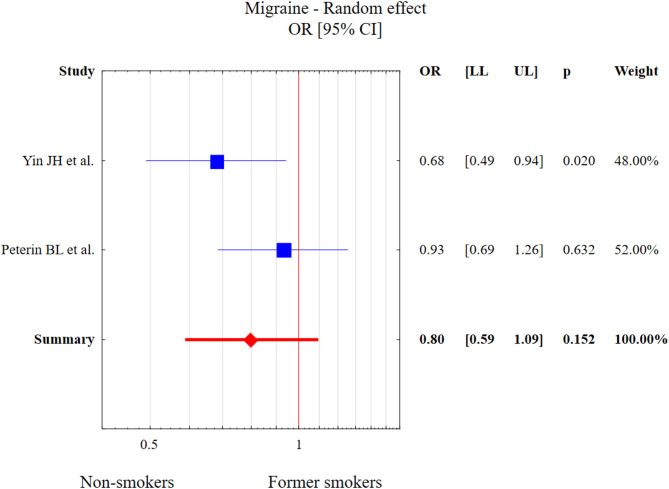

Only two studies considered former smoking in migraine. The test of heterogeneity was Q = 1.9, df = 1, p = 0.168, I2 = 47.5%. The results of Egger’s test (p > 0.05) indicate a lack of any statistically significant publication bias. Former smoking was not associated with migraine diagnosis in comparison to the control group (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.59–1.09, p = 0.152). This result is presented in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

The meta-analysis results of former smoking and migraine in comparison to control patients. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

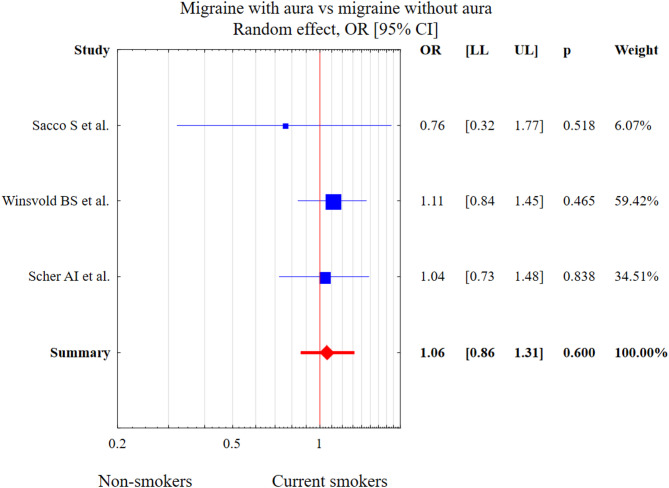

Three studies presented a migraine division into MwA and MwoA. The test of heterogeneity was Q = 0.722, df = 2, p = 0.697, I2 = 0.00%. Current smoking was not associated with MwA diagnosis in comparison to the MwoA group (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 0.86–1.31, p = 0.600). This result is presented in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

The meta-analysis results of current smoking and MwA in comparison to MwoA patients. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

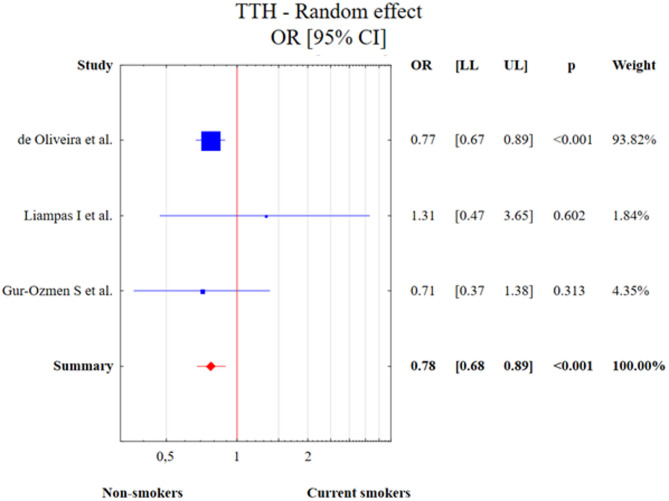

Three studies described smoking in TTH. The test of heterogeneity was Q = 1.087, df = 2, p = 0.581, I2 = 0.00%. Due to the value of the I2 statistic, a random effect model was used in the meta-analysis. Current smoking was associated with decreased risk of TTH diagnosis in comparison to the control group (OR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.68–0.89, p < 0.001). This result is presented in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

The meta-analysis results of current smoking and TTH in comparison to control patients. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

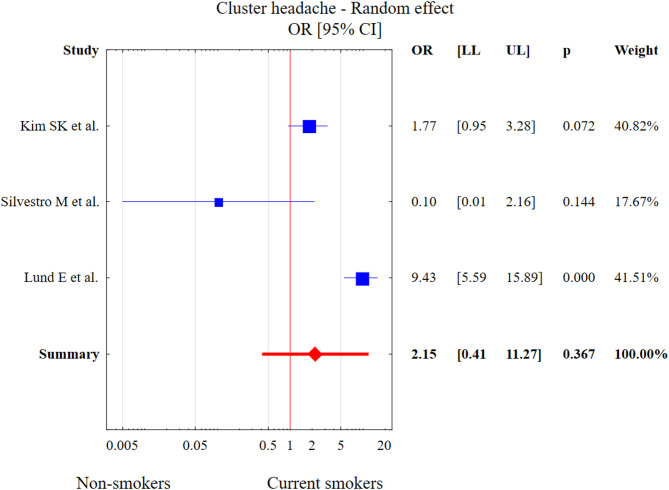

Three studies described smoking in CH. The test of heterogeneity was Q = 22.55, df = 2, p < 0.001, I2 = 95.33%. The results of Egger’s test (p > 0.05) indicate a lack of any statistically significant publication bias. Current smoking was not associated with CH diagnosis in comparison to the control group (OR = 2.15, 95% CI: 0.41–11.27, p = 0.367). This result is presented in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

The meta-analysis results of current smoking and CH in comparison to control patients. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

A meta-regression was not available for TTH, CH, and former-smoker calculations due to the limited number of included studies.

Risk of bias assessment in included studies

All thirty-seven included studies were assessed for risk of bias. Of these, thirty-six were observational studies [12, 20–40, 42–45, 47–56] and one was an experimental study [46]. Among the observational studies, twenty-three were cross-sectional studies [20, 21, 23, 25, 27–29, 31–34, 38–40, 42–45, 47, 48, 50, 51, 53], six were case-control studies [35, 36, 41, 52, 54, 55], six were cohort studies [12, 22, 26, 30, 37, 49], and one was a case-series [24] study. Within the cross-sectional studies, one study received seven “yes” answers [20] and thirteen received six “yes” answers, resulting in a low risk of bias [21, 23, 27–29, 31, 34, 38–40, 44, 47, 48]; while four studies received five “yes” answers [25, 33, 43, 45] and two received four “yes” answers [32, 51], thus receiving moderate risk of bias note; and the last three studies received three positive answers [42, 50, 53], resulting being assessed as having a high risk of bias. In the group of case-control studies, one study received nine “yes” answers [36], three studies received eight “yes” answers [35, 41, 54], one seven positive answers [55] and thus they having a low risk of bias; one study received six “yes” answers [52] and consequently it was assessed as having a moderate risk of bias. The distribution of responses in the cohort studies was as follows: two studies received eight “yes” responses, which allowed them to be classified as having a low risk of bias [12, 49]; two studies had seven positive answers [26, 37], one six positive answers [22] and were classified as moderate risk of bias; one study got four “yes” responses and it had high risk of bias [30]. The one case-series study [24] received six “yes” responses, resulting in a classification as having a moderate risk of bias. The randomized controlled study [46] received ten positive responses, and its risk of bias was assessed as low. In summary, 22 out of 37 included studies received “low” risk of bias note [12, 20, 21, 23, 27–29, 31, 34–36, 38–41, 44, 46–49, 54, 55], 11 out of 37 were identified as moderate risk of bias [22, 24–26, 32, 33, 37, 43, 45, 51, 52] and 4 studies received high risk of bias note [30, 42, 50, 53]. Additional details on the responses to individual questions for each study are provided in the Table S2 from supplementary materials.

Discussion

Smoking is a risk factor for many diseases such as stroke, cardiovascular disease and lung cancer [57]. It is responsible for over 20% of males deaths annually [58]. In 2019, there were 1,14 billion smokers worldwide, and its prevalence was estimated at approximately 15% [59]. Pooled prevalence of smokers in patients with migraine in our study was estimated as 20%. These similar values may indicate that patients with migraine slightly more often smoke than the general population. However, in a previous review of literature related to this topic, smoking prevalence in migraine varied between 25.9% and 51%, and thus the authors suggested smoking is more common in this group of patients [6]. The above difference between presented review and this study may be the result of either their not conducting meta-analysis or from including single studies with other methodologies and participant characteristics [60–63]. Tobacco smoke is often indicated as a trigger for migraine [50, 64–67]. Our study confirmed that current smoking is associated with increased risk of migraine. However, some authors deny the smoking association in migraine [39, 55, 68]. Since smoking may trigger a migraine attack, as was mentioned earlier [50, 64–67], it is interesting that the prevalence of smoking in patients with migraine was comparable with the global population or patients with TTH. Several mechanisms have been proposed which explain the association between migraine and smoking. Tobacco smoke contains nicotine and other chemicals, such as cadmium, that can affect central nervous system structures [69] or stimulate expression of pro-inflammatory molecules resulting in peripheral and central sensitization which can contribute to the development of headache pain [70–72]. The other theoretical pathways include oxidative stress, decreased NO generation, and increased production of hormones helping in trigger attack [6, 73–75]. Taking into consideration the migraine subtypes, it has been suggested that aura attacks in patient with MwA are also associated with smoking [76, 77]. Our study did not show an association with smoking habits in MwA in comparison to MwoA, but Salhofer-Polanyi et al.’s study suggested that smoking might decrease the risk of MwoA while increasing MwA risk [76]. Also, former smoking was not associated with migraine. It is difficult to discuss these results with those in the literature, because similar observations have not been conducted. There is a need to emphasize that data for the present study were extracted from studies which were not mainly focused on smoking topics; additionally, in prevalence and association calculation between smoking and migraine was noted high heterogeneity, therefore, our results need to be interpreted carefully and may be different in other populations.

There was observation that patients with CH have a tendency to use different addictive substances including cigarettes [78]. Therefore, in accordance with that fact the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking in primary headaches belongs to patients with CH in our study. There are proofs in the literature confirming our results [12, 79–81]. Common smoking in CH might be partially explained by the opinion that CH is more widespread in men [82], and also male subjects are more often smokers [63]. However, the pooled-prevalence was estimated on 64% smoking in patients with CH which is extremaley high value. Lund et al. and Rozen et al. [54, 83], independently, compared smoking habits in patients with CH for both sexes, and their results showed a much higher prevalence of cigarette usage in males [54]. Besides the highest prevalence of smoking among primary headaches, there was a lack of association between CH and smoking. However, in the literature, CH is considered to be positively associated with smoking, and smoking increases CH frequency and severity [11, 84]. Additionally, nicotinism might be associated with a worse clinical course of CH [85]. Our result may, however, stem from the limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis. As well as the presented calculations included only patients with CH without any co-existing headache or severe systemic disease, therefore it may be the cause of non-significant association between CH and smoking. Observed high heterogeneity in smoking prevalence and association in this meta-analysis may limit generalizability of our findings. On the other hand, patients who have never smoked appear to have an earlier onset of CH [13, 86]. Moreover, there is no clear evidence that quitting smoking reduces the frequency or intensity of CH attacks, suggesting a more complex relationship between smoking and CH involving genetic or neurobiological factors [87, 88]. We conclude that since the highest prevalence of smoking was always in CH, and some authors have automatically associated it with CH, but smoking in CH may result from other, as yet unidentified factors.

According to our analysis, 19% of patients with TTH currently smoke. In the literature, there is little evidence regarding tobacco use in TTH. The study by Sabah et al. [89] reports cigarette smoking is present among 62.74% of patients with TTH. However, this research had specific settings, i.e. the study was conducted by electronic questionnaires, and smoking was not clearly defined. Our study showed that smoking may protect against TTH attacks, because smoking was associated with decreased risk of TTH. There are no similar results in the literature. We have to emphasize that this result is only based on three studies, and it was not possible to calculate the meta-regression. On the other hand, the pathophysiology of TTH is often connected with the serotonergic system [90]. and smoking is known for its influence on serotonin levels, which may provide a potential connection between smoking and TTH [91]. However, this observation requires further analysis, because we obtained contrasting results.

It is worth mentioning that smoking is more widespread among disadvantaged patients, such as those with low socioeconomic status or low income [92, 93]. In turn smoking is positively associated with increased all types of headache or migraine frequency among patients with low socioeconomic status [94]. The presented association may potentially have an impact on received results, but we were not able to assess the impact of low-income status and socioeconomic status as moderator factors in a meta-analysis, because not every study contains these data. Also comorbidity disease in patients with primary headache may have an impact on smoking. For example, smoking is significantly associated with increased risk of depression, which is a common disease in migraine [95–97]. Similar situation concern occurring psychiatric diseases in patients with CH [54]. By contrast lifestyle has a significant impact on headaches, especially not adequate and unhealthy lifestyle can exacerbate migraine [98, 99]. So, our results without checking the influence of comorbid disease or lifestyle to primary headache have to be interpreted carefully.

In addition, nicotine may currently also be delivered in other modern products such as electronic cigarettes. These devices have never been studied for their effect on primary headaches, but previous studies indicate that headaches, not necessarily primary headaches, may be a side effect of using electronic cigarettes [100]. Electronic cigarettes are marketed as a safer option for smoker and may help people to quit smoking; however, it is mostly young people who use these products, and they are also vulnerable to primary headaches [101, 102]. Therefore, there is a need for a modern study on this topic.

The present study had several limitations. This is the first attempt to summarize data on smoking and primary headaches utilizing a systematic review and meta-analysis. However, different authors have used other statistical methods in studies related to our subject of our interest, and only some of these consider data about confounding factors. In our meta-analysis, we performed meta-regression to minimize confounding factors, but due to the insufficient number of studies adjusting results to factors such as socio-economic status, level of education and alcohol consumption, we were only able to use age, gender and year of publication as moderators. Meta-regression could not be performed in prevalence of smoking calculation due to lack of basic population data in every included study. It is also important to emphasize that not all studies included in the prevalence analysis were included into association calculations, because most of them did not contain a control group of patients without headache. Additionally, some studies contain comparison groups consisting of patients with other types of headache, or probable migraine diagnosis, or primary headache subtypes. This type of study was only included in prevalence in order to elicit the most objective results. In our opinion, the reduced number of studies in association calculations is the biggest limitation to our study.

Conclusions

The prevalence of smoking in migraine and TTH was moderate. Current smoking was associated with increased risk of migraine and decreased risk of TTH. The direction of these associations remains unclear, so by no means is smoking advised to avoid TTH. There was no direct association between current smoking and CH, despite the fact that over half of patients with CH smoked. The influence of electronic cigarettes commonly used these days is not yet explored in primary headaches, despite their wide-spread use. Due to the potential limitations of the presented study, the results have to be interpreted carefully, and studies focused only on the topic of smoking are needed in the future.

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

MWP and BB was involved in the conception and visualization of the study. BB, JP, PN, MWP collected the data and prepared a manuscript. BB was involved in data analysis. MWP, SB, HM supervised the study. MWP, HM, MS and SB revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang Z, Yang X, Zhao B, Li W (2023) Primary headache disorders: from pathophysiology to neurostimulation therapies. Heliyon 9(4):e14786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmetz JD, Seeher KM, Schiess N, Nichols E, Cao B, Servili C et al (2024) Global, regional, and National burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Neurol 23(4):344–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Linde M, Steiner TJ (2022) The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J Headache Pain 23(1):34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waliszewska-Prosół M, Montisano DA, Antolak M, Bighiani F, Cammarota F, Cetta I et al (2024) The impact of primary headaches on disability outcomes: a literature review and meta-analysis to inform future iterations of the global burden of disease study. J Headache Pain 25(1):27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ (2023) Global epidemiology of migraine and its implications for public health and health policy. Nat Rev Neurol 19(2):109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberger AH, Seng EK (2023) The relationship of tobacco use and migraine: a narrative review. Curr Pain Headache Rep 27(4):39–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elser H, Kruse CFG, Schwartz BS, Casey JA (2024) The environment and headache: a narrative review. Curr Environ Health Rep 11(2):184–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajdusianek W, Żórawik A, Waliszewska-Prosół M, Poręba R, Gać P (2021) Tobacco and nervous system development and function-new findings 2015–2020. Brain Sci 11(6):797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Yang P, Wu X, Yu X, Zeng F, Wang H (2023) Association between secondhand smoke exposure and severe headaches or migraine in never-smoking adults. Headache 63(10):1341–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarker MAB, Rahman M, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Hossain S, Kasuya H, Sakamoto J et al (2013) Association of smoked and smokeless tobacco use with migraine: a hospital-based case-control study in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Tob Induc Dis 11(1):15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elbadawi ASA, Albalawi AFA, Alghannami AK, Alsuhaymi FS, Alruwaili AM, Almaleki FA et al (2021) Cluster headache and associated risk factors: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Cureus 13(11):e19294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamdy MM, Nasr N, Hamdy E (2024) Smoking and cluster headache presentation and responsiveness to treatment. BMC Neurol 24(1):349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung PW, Kim BS, Park JW, Sohn JH, Lee MJ, Kim BK et al (2021) Smoking history and clinical features of cluster headache: results from the Korean cluster headache registry. J Clin Neurol Seoul Korea 17(2):229–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levi R, Edman GV, Ekbom K, Waldenlind E (1992) Episodic cluster headache. II: high tobacco and alcohol consumption in males. Headache 32(4):184–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin PR (2020) Triggers of primary headaches: issues and pathways forward. Headache 60(10):2495–2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wahbeh F, Restifo D, Laws S, Pawar A, Parikh NS (2024) Impact of tobacco smoking on disease-specific outcomes in common neurological disorders: a scoping review. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Australas 122:10–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan B, Jin X, Jun L, Qiu S, Zheng Q, Pan M (2019) The relationship between smoking and stroke: a meta-analysis. Med (Baltim) 98(12):e14872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieczorek M, Gwinnutt JM, Ransay-Colle M, Balanescu A, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Boonen A et al (2022) Smoking, alcohol consumption and disease-specific outcomes in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs): systematic reviews informing the 2021 EULAR recommendations for lifestyle improvements in people with RMDs. RMD Open 8(1):e002170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moola S, Munn Z, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Lisy K et al (2015) Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): the Joanna Briggs institute’s approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13(3):163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Hassany L, Acarsoy C, Ikram MK, Bos D, MaassenVanDenBrink A (2024) Sex-specific association of cardiovascular risk factors with migraine: the population-based Rotterdam study. Neurology 103(4):e209700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scher AI, Terwindt GM, Picavet HSJ, Verschuren WMM, Ferrari MD, Launer LJ (2005) Cardiovascular risk factors and migraine: the GEM population-based study. Neurology 64(4):614–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.True D, Mullin K, Croop R (2024) Safety of Rimegepant in adults with migraine and cardiovascular risk factors: analysis of a multicenter, long-term, open-label study. Pain Ther 13(5):1203–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipton RB, Buse DC, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singh P, Munjal S et al (2021) Burden of increasing opioid use in the treatment of migraine: results from the migraine in America symptoms and treatment study. Headache 61(1):103–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozen TD (2019) High-Volume anesthetic suboccipital nerve blocks for treatment refractory chronic cluster headache with long-term efficacy data: an observational case series study. Headache 59(1):56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozen TD (2011) A history of cigarette smoking is associated with the development of cranial autonomic symptoms with migraine headaches. Headache 51(1):85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monteith TS, Gardener H, Rundek T, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL (2015) Migraine and risk of stroke in older adults. Neurology 85(8):715–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterlin BL, Rosso AL, Sheftell FD, Libon DJ, Mossey JM, Merikangas KR (2011) Post-traumatic stress disorder, drug abuse and migraine: new findings from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Cephalalgia Int J Headache 31(2):235–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tietjen GE, Bushnell CD, Herial NA, Utley C, White L, Hafeez F (2007) Endometriosis is associated with prevalence of comorbid conditions in migraine. Headache 47(7):1069–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misakian AL, Langer RD, Bensenor IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE et al (2003) Postmenopausal hormone therapy and migraine headache. J Womens Health 2002 12(10):1027–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belitardo de Oliveira A, Winter Schytz H, Fernando Prieto Peres M, Peres Mercante JP, Brunoni AR, Wang YP et al (2024) Does physical activity and inflammation mediate the job stress-headache relationship? A sequential mediation analysis in the ELSA-Brasil study. Brain Behav Immun 120:187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benseñor IM, Goulart AC, Lotufo PA, Menezes PR, Scazufca M (2011) Cardiovascular risk factors associated with migraine among the elderly with a low income: the Sao Paulo ageing & health study (SPAH). Cephalalgia Int J Headache 31(3):331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SK, Chu MK, Kim BK, Chung PW, Moon HS, Lee MJ et al (2024) An analysis of the determinants of the health-related quality of life in Asian patients with cluster headaches during cluster periods using the time trade-off method. J Clin Neurol Seoul Korea 20(1):86–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho S, Kim KM, Chu MK (2024) Coffee consumption and migraine: a population-based study. Sci Rep 14(1):6007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silvestro M, Dovetto FM, Corvino V, Apisa P, Malesci R, Tessitore A et al (2021) Enlarging the spectrum of cluster headache: extracranial autonomic involvement revealed by voice analysis. Headache 61(9):1452–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacco S, Altobelli E, Ornello R, Ripa P, Pistoia F, Carolei A (2014) Insulin resistance in migraineurs: results from a case-control study. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 34(5):349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambru G, Castellini P, Manzoni GC, Torelli P (2010) Mode of occurrence of traumatic head injuries in male patients with cluster headache or migraine: is there a connection with lifestyle? Cephalalgia Int J Headache 30(12):1502–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dinia L, Bonzano L, Albano B, Finocchi C, Del Sette M, Saitta L et al (2013) White matter lesions progression in migraine with aura: a clinical and MRI longitudinal study. J Neuroimaging Off J Am Soc Neuroimaging 23(1):47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang YF, Tzeng YS, Yu CC, Ling YH, Chen SP, Lai KL et al (2023) Sex differences in the clinical manifestations related to dependence behaviors in medication-overuse headache. J Headache Pain 24(1):145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin JH, Lin YK, Yang CP, Liang CS, Lee JT, Lee MS et al (2021) Prevalence and association of lifestyle and medical-, psychiatric-, and pain-related comorbidities in patients with migraine: a cross-sectional study. Headache 61(5):715–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin KH, Wang PJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Chung CT, Tsou HK et al (2004) Cluster headache in the Taiwanese -- a clinic-based study. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 24(8):631–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gür-Özmen S, Karahan-Özcan R (2016) Iron deficiency anemia is associated with menstrual migraine: a case-control study. Pain Med Malden Mass 17(3):596–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Celik Y, Ekuklu G, Tokuç B, Utku U (2005) Migraine prevalence and some related factors in Turkey. Headache 45(1):32–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie Q, Huang Q, Wang J, Li N, Tan G, Zhou J (2013) Clinical features of cluster headache: an outpatient clinic study from China. Pain Med Malden Mass 14(6):802–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.QiHong L, Jinzh X, HongYan L (2009) Association between Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG antibodies and migraine. J Headache Pain 10(2):121–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straube A, Pfaffenrath V, Ladwig KH, Meisinger C, Hoffmann W, Fendrich K et al (2010) Prevalence of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache in Germany–the German DMKG headache study. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 30(2):207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steiner TJ, Lange R, Voelker M (2003) Aspirin in episodic tension-type headache: placebo-controlled dose-ranging comparison with paracetamol. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 23(1):59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jahromi SR, Abolhasani M, Meysamie A, Togha M (2013) The effect of body fat mass and fat free mass on migraine headache. Iran J Neurol 12(1):23–27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leroux E, Taifas I, Valade D, Donnet A, Chagnon M, Ducros A (2013) Use of cannabis among 139 cluster headache sufferers. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 33(3):208–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winsvold BS, Sandven I, Hagen K, Linde M, Midthjell K, Zwart JA (2013) Migraine, headache and development of metabolic syndrome: an 11-year follow-up in the Nord-Trøndelag health study (HUNT). Pain 154(8):1305–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.López-Mesonero L, Márquez S, Parra P, Gámez-Leyva G, Muñoz P, Pascual J (2009) Smoking as a precipitating factor for migraine: a survey in medical students. J Headache Pain 10(2):101–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martini N, Hawa T, Almouallem MM, Hanna M, Almasri IA, Hamzeh G (2025) Investigating risk factors for migraine in Syrian women: a cross-sectional case-control study. Sci Rep 15(1):4148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liampas I, Papathanasiou S, Tsikritsis N, Roka V, Roustanis A, Ntontos T et al (2021) Nutrient status in patients with frequent episodic tension-type headache: a case-control study. Rev Neurol (Paris) 177(10):1283–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delva M, Delva I, Pinchuk V, Kryvchun A, Purdenko T. Prevalence, and predictors of fatigue in patients with episodic migraine. Wiadomosci Lek Wars Pol 1960 2022;75(8 pt 2):1970–1974 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Lund N, Petersen A, Snoer A, Jensen RH, Barloese M (2019) Cluster headache is associated with unhealthy lifestyle and lifestyle-related comorbid diseases: results from the Danish cluster headache survey. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 39(2):254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaudhuri JR, Mridula KR, Keerthi AS, Prakasham PS, Balaraju B, Bandaru VCSS (2016) Association between Chlamydia pneumoniae and migraine: a study from a tertiary center in India. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 30(2):150–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gur-Ozmen S, Karahan-Ozcan R (2019) Factors associated with insulin resistance in women with migraine: a cross-sectional study. Pain Med Malden Mass 20(10):2043–2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Silva R, Silva D, Piumika L, Abeysekera I, Jayathilaka R, Rajamanthri L et al (2024) Impact of global smoking prevalence on mortality: a study across income groups. BMC Public Health 24(1):1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ezzati M, Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Lopez AD (2005) Role of smoking in global and regional cardiovascular mortality. Circulation 112(4):489–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reitsma MB, Flor LS, Mullany EC, Gupta V, Hay SI, Gakidou E (2021) Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and initiation among young people in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. Lancet Public Health 6(7):e472–e481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y, Huang X, Cheng H, Guo H, Yan B, Mou T et al (2023) The association between migraine and Fetal-Type posterior cerebral artery in patients with ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis Basel Switz 52(1):68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gan WQ, Estus S, Smith JH (2016) Association between overall and mentholated cigarette smoking with headache in a nationally representative sample. Headache 56(3):511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sedlic M, Mahovic D, Kruzliak P (2016) Epidemiology of primary headaches among 1,876 adolescents: a cross-sectional survey. Pain Med Malden Mass 17(2):353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molarius A, Tegelberg A, Ohrvik J (2008) Socio-economic factors, lifestyle, and headache disorders - a population-based study in Sweden. Headache 48(10):1426–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spierings EL, Ranke AH, Honkoop PC (2001) Precipitating and aggravating factors of migraine versus tension-type headache. Headache 41(6):554–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wöber C, Brannath W, Schmidt K, Kapitan M, Rudel E, Wessely P et al (2007) Prospective analysis of factors related to migraine attacks: the PAMINA study. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 27(4):304–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Lima AM, Sapienza GB, Giraud V, de Fragoso O (2011) Odors as triggering and worsening factors for migraine in men. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 69(2B):324–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelman L (2007) The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 27(5):394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roy R, Sánchez-Rodríguez E, Galán S, Racine M, Castarlenas E, Jensen MP et al (2019) Factors associated with migraine in the general population of Spain: results from the European health survey 2014. Pain Med Malden Mass 20(3):555–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rozen TD (2018) Linking cigarette smoking/tobacco exposure and cluster headache: a pathogenesis theory. Headache 58(7):1096–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hawkins JL, Denson JE, Miley DR, Durham PL (2015) Nicotine stimulates expression of proteins implicated in peripheral and central sensitization. Neuroscience 290:115–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zięba S, Zalewska A, Żukowski P, Maciejczyk M (2024) Can smoking alter salivary homeostasis? A systematic review on the effects of traditional and electronic cigarettes on qualitative and quantitative saliva parameters. Dent Med Probl 61(1):129–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Swain N, Thakur M, Pathak J, Patel S, Hosalkar R, Ghaisas S (2022) Altered Immunoexpression of SOX2, OCT4 and Nanog in the normal-appearing oral mucosa of tobacco users. Dent Med Probl 59(3):389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ambrose JA, Barua RS (2004) The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol 43(10):1731–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moody TW, Jensen RT (2021) Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide/vasoactive intestinal peptide [Part 1]: biology, pharmacology, and new insights into their cellular basis of action/signaling which are providing new therapeutic targets. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 28(2):198–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taylor FR (2015) Tobacco, nicotine, and headache. Headache 55(7):1028–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salhofer-Polanyi S, Frantal S, Brannath W, Seidel S, Wöber-Bingöl Ç, Wöber C et al (2012) Prospective analysis of factors related to migraine aura–the PAMINA study. Headache 52(8):1236–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hauge AW, Kirchmann M, Olesen J (2011) Characterization of consistent triggers of migraine with aura. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 31(4):416–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Govare A, Leroux E (2014) Licit and illicit drug use in cluster headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 18(5):413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li K, Sun S, Xue Z, Chen S, Ju C, Hu D et al (2022) Pre-attack and pre-episode symptoms in cluster headache: a multicenter cross-sectional study of 327 Chinese patients. J Headache Pain 23(1):92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rozen TD, Fishman RS (2012) Cluster headache in the united States of America: demographics, clinical characteristics, triggers, suicidality, and personal burden. Headache 52(1):99–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manzoni GC (1999) Cluster headache and lifestyle: remarks on a population of 374 male patients. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 19(2):88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fischera M, Marziniak M, Gralow I, Evers S (2008) The incidence and prevalence of cluster headache: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 28(6):614–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rozen TD, Fishman RS (2012) Female cluster headache in the united States of America: what are the gender differences? Results from the United States cluster headache survey. J Neurol Sci 317(1–2):17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nappi C, Giuseppe (1995) Case-control study on the epidemiology of cluster headache I: etiological factors and associated conditions. Neuroepidemiology 14(3):123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lund NLT, Snoer AH, Jensen RH (2019) The influence of lifestyle and gender on cluster headache. Curr Opin Neurol 32(3):443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rozen TD (2018) Cluster headache clinical phenotypes: tobacco nonexposed (Never smoker and no parental secondary smoke exposure as a Child) versus tobacco-exposed: results from the United States cluster headache survey. Headache 58(5):688–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petersen AS, Lund N, Goadsby PJ, Belin AC, Wang SJ, Fronczek R et al (2024) Recent advances in diagnosing, managing, and understanding the pathophysiology of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol 23(7):712–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ferrari A, Zappaterra M, Righi F, Ciccarese M, Tiraferri I, Pini LA et al (2013) Impact of continuing or quitting smoking on episodic cluster headache: a pilot survey. J Headache Pain 14(1):48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sabah ZU, Aziz S, Narapureddy BR, Alasiri HAA, Asiri HYM, Asiri AHH et al (2022) Clinical-epidemiology of tension-type headache among the medical and dental undergraduates of King Khalid university, Abha, Saudi Arabia. J Pers Med 12(12):2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bendtsen L (2000) Central sensitization in tension-type headache–possible pathophysiological mechanisms. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 20(5):486–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Campos MW, Serebrisky D, Castaldelli-Maia JM (2016) Smoking and cognition. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 9(2):76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M (2012) Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1248:107–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Raffaelli B, Rubio-Beltrán E, Cho SJ, De Icco R, Labastida-Ramirez A, Onan D et al (2023) Health equity, care access and quality in headache – part 2. J Headache Pain 24(1):167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Winter AC, Berger K, Buring JE, Kurth T (2012) Associations of socioeconomic status with migraine and non-migraine headache. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 32(2):159–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hu Z, Cui E, Chen B, Zhang M (2025) Association between cigarette smoking and the risk of major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis in depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Front Med 12:1529191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amiri S, Behnezhad S, Azad E (2019) Migraine headache and depression in adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Klin Diagn Ther Rehabil Organ Ges Osterreichischer Nervenarzte Psychiater 33(3):131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee J, Bhowmick A, Wachholtz A (2020) Chronic migraine headaches: role of smoking and locus of control. SN Compr Clin Med 2(5):579–586 [Google Scholar]

- 98.Raggi A, Leonardi M, Arruda M, Caponnetto V, Castaldo M, Coppola G et al (2024) Hallmarks of primary headache: part 1– migraine. J Headache Pain 25(1):189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huang Y, Yan W, Jia Y, Xie Q, Lei Y, Chen Z et al (2025) Migraine and increased cardiovascular disease risk: interaction with traditional risk factors and lifestyle factors. J Headache Pain 26(1):92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lindson N, Butler AR, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hajek P, Begh R et al (2024) Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1):CD010216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gorini G, Gallus S, Carreras G, De Mei B, Masocco M, Faggiano F et al (2020) Prevalence of tobacco smoking and electronic cigarette use among adolescents in Italy: global youth tobacco surveys (GYTS), 2010, 2014, 2018. Prev Med 131:105903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li X, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Chen F, Shao L, Zhang L (2022) Association between E-Cigarettes and asthma in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 62(6):953–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.