Abstract

Background

Paeonia lactiflora Pall. (PL) is widely recognized for its ornamental, edible, and medicinal properties. Its principle bioactive constituents include monoterpene glycosides (MGs), gallaglycosides (GGs), and flavonoids. However, the metabolic and molecular basis underlying their biosynthesis in PL remain poorly understood. In this study, an integrated non-targeted metabolomics and transcriptomics approach was employed to investigate the metabolic profiles and gene expression patterns in four distinct PL tissues.

Results

Metabolomic and transcriptome profiling revealed tissue-specific patterns of metabolite accumulation and gene expression. KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) showed that secondary metabolites biosynthesis and transport processes play vital roles in the tissue-specific accumulation of bioactive constituents. A total of 19 DEMs and 90 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with MGs, 10 DEMs and 14 DEGs associated with GGs, and 205 DEMs and 67 DEGs associated with flavonoids were identified. Roots, the primary medicinal tissue, exhibited substantial accumulation of eight MGs, two GGs, and 18 flavonoids, as well as elevated expression levels of 16, two and nine structural genes, respectively. Nine CYP450 s and two UGTs associated with MGs, and 14 UGTs associated with flavonoids, were identified as new candidate genes through phylogenetic and expression analyses. CYP71E1, CYP71 AN24.1, CYP71 AU50.2, and UGT91 A1.1 for MGs biosynthesis, and UGT71 K1.4, UGT89B2, UGT73 C25, and UGT71 K1.2 for flavonoids biosynthesis were prioritized through correlation analysis. WGCNA revealed that turquoise, green, and blue modules were significantly correlated with MGs and flavonoids biosynthesis, identifying 24 hub genes for MGs and 18 for flavonoids. The overlap of phylogenetic, expression, correlation and WGCNA analyses identified CYP71 AN24.1 and UGT91 A1.1 as putative MGs biosynthetic genes, and UGT89B2 as a flavonoid-related gene. Protein structure prediction and similarity analysis further supported their functional conservation with known terpenoid-modifying enzymes and flavonoid-specific glycosyltransferases, respectively.

Conclusions

These findings identified CYP71 AN24.1, UGT91 A1.1, and UGT89B2 as novel genes involved in MGs and flavonoids biosynthesis. The study provides a valuable theoretical foundation for future metabolic engineering aimed at optimizing the biosynthetic pathways of these primary active constituents in PL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11750-3.

Keywords: Paeonia Lactiflora, Monoterpene glycosides, Gallaglycoside, Flavonoids, Biosynthesis, Transcriptome, Metabolomic

Introduction

Paeonia lactiflora Pall. (PL), a plant with excellent ornamental, edible and medicinal value, has been cultivated in China for over 1200 years. Its roots, classified as “Paeoniae Radix Alba” (Baishao) and “Paeoniae Radix Rubra” (Chishao) based on different processing methods, have been traditionally used in Chinese herbal medicines, highly esteemed for their therapeutic properties [1, 2]. Rich in bioactive compounds such as terpenoids, gallatannins, and flavonoids [3, 4], PL roots exhibited diverse pharmacological properties, including neuroimmune modulation, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, improvement of blood rheology, antidepressant, anti-liver fibrosis, and anti-tumor effects [3–5]. Due to these extensive medicinal properties, PL has served as a critical raw material in traditional Chinese medicine, nutraceuticals, and functional food and beverage industries. Over the past decade, the annual demand for PL consistently remained high, ranging between 12,000 and 15,000 metric tons for medicinal applications alone. This sustained demand has highlighted the importance of elucidating the biosynthetic regulation and enhancing the accumulation of bioactive constituents in PL to improve its quality and efficacy.

Notably, monoterpene glycosides (MGs) were the most abundant active constituents in PL roots. MGs, characterized by a cage-like pinane skeleton, such as paeoniflorin and its derivatives, served as chemotaxonomic markers of the Paeoniaceae family [6]. These compounds also contained a benzoyl substituent and a glucoside group attached to the pinane skeleton. Their biosynthesis primarily occurred through the mevalonate (MVA) or methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathways, generating the precursor isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [6]. With the aid of isopentenyltransferase (PT), IPP and DMAPP were converted into various terpene precursors, such as geranyl diphosphate (GPP) [7]. These precursors underwent several chemical reactions, including chain extension, modification, and skeleton structure rearrangement, facilitated by enzymes such as terpene synthase (TPS) and modifying enzymes, ultimately forming various MGs [8]. Furthermore, benzoic acid and its derivatives, acting as benzoyl ligands of MGs, were biosynthesized via the core β-Oxidative pathway and non-β-Oxidative pathway, using phenylalanine as the initial substrate [9].

In addition to MGs, the Paeoniaceae family was reported to be abundant in gallaglycosides (GGs), hydrolyzable compounds composed of polygalloyl esters of glucose. This class of compounds, prominent in PL and exhibiting significant pharmacological effects, was biosynthesized through a process divided into three stages, corresponding to the typical structural features of the intermediates involved. Gallagic acid synthesis initiated through the shikimate pathway [10], followed by conjugation with glycosyl moieties to form simple GGs. These early intermediates, ranging from β-glucogallin (monogalloglycoside, 1GG) to the fully substituted core structure 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucopyranose (pentagalloylglycoside, 5GG), were characterized by fewer than five gallayl groups eaterified onto the glucose backbone. Further gallacylation of 5GG then converted simple gallaglycosides into complex gallaglycosides (referred to here as polygalloylglucodies), which contained six to twelve gallayl substituents (hexagalloglycosides, 6GG to dodecagalloslydides, 12GG).

Moreover, flavonoids represented another class of active ingredients found abundantly in PL, yet their pharmaceutical potential remained underexplored. The biosynthesis of flavonoids in PL primarily occurs through the phenylpropanoid pathway, with L-Phenylalanine used as the initial substrate. This pathway involved enzymes such as chalcone synthesis (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), dihydroflavanol 4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthesis (ANS), and other phenylpropanoid biosynthesis enzymes, ultimately producing quercetin, catechin, anthocyanidin and others [11].

However, few studies addressed the identification genes responsible for the biosynthesis of MGs, GGs, and flavonoids in PL. Although comparative transcriptomics techniques were previously utilized by Yuan [12] and Lu [13] to investigate genes associated with MGs biosynthesis, particularly paeoniflorin and its derivatives in PL, the complete set of the genes involved in MGs and paeoniflorin biosynthesis, including their pathways, remained unclear. Similarly, genes related to the GGs and flavonoids remained poorly characterized, with previous research mainly focused on gallagic acid and anthocyanin biosynthesis in PL flowers [14, 15]. To address these gaps, an integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic approach was employed to systematically clarify the biosynthesis and metabolism of MGs, GGs, and flavonoids in PL. This approach, previously validated in other plants such as Centella asiatica [16], Glycyrrhiza [17], and Piper nigrum [18], enabled the correlation of gene expression patterns with metabolite profiles, thereby facilitating identification of candidate genes and biosynthesis pathways specific to PL.

Previous studies also demonstrated significant variations in chemical constituents among different PL tissues. Terpenoids and glycosides, flavonoids, tannins, volatile oils, phenols, and carbohydrates were predominantly found in roots [19, 20], while flavonoids, astragaloside, and gallatannins were abundant in flowers [21]. Tannins and astragalosides were reported in fruits and seeds [22], respectively. Stems and leaves were notable for high flavonoids content [23]. Our previous investigation on the expression patterns of four MGs (oxypaeoniflorin, albiflorin, paeoniflorin, benzoylpaeoniflorin) and nine related biosynthesis genes, primarily involved in upstream terpene skeleton synthesis, revealed tissue-specific and temporal differences in metabolites levels [24]. Variations in metabolites often resulted from differential gene expression within metabolic networks. Analyzing these differential expressed metabolites (DEMs) and associated genes among PL tissues could help elucidate secondary metabolites biosynthesis pathways and identify key enzyme genes.

In this study, untargeted metabolomics and high-throughput sequencing technologies were applied to comprehensively investigate gene expression and metabolic differences across PL tissues. Additionally, the correlation between gene transcription levels and metabolite accumulation was examined to elucidate the biosynthesis pathways of important secondary metabolites such as MGs, GGs and flavonoids, providing new insights into the complex metabolic network in PL. These findings provided a useful metabolites database and genetic information for PL, potentially facilitating metabolic engineering of genes involved in terpenoids and flavonoids synthesis.

Results

Untargeted metabolic profiling of different PL tissues

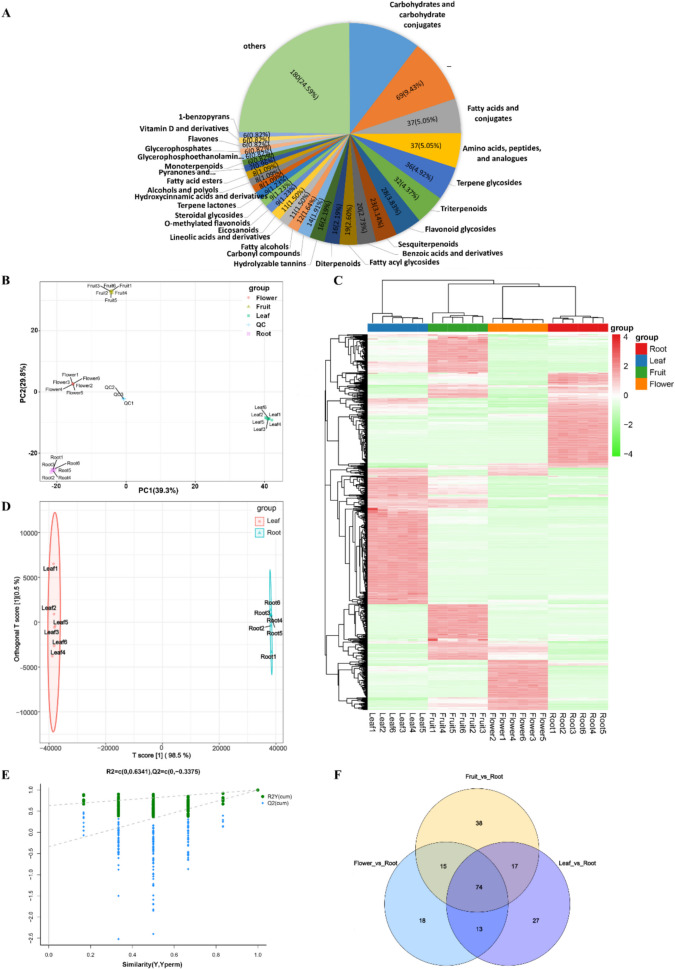

Untargeted metabolomics profiling was performed on all samples. A total of 1406 metabolites belonging to 11 categories (column “superclass” in Additional Table 1) were identified in four tissues based on the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB). The top five categories were “Lipids and lipid-like molecules”, “Phenylpropanoids and polyketides”, “Organic oxygen compounds”, “Organoheterocyclic compounds”, and “Organic acids and derivatives”, containing 307, 135, 100, 73, and 58 metabolites, respectively. The presence of various secondary metabolites, such as terpenoids, flavonoids, glycosides, tannins, and organic acids, indicated a complex metabolic landscape in PL tissues (Fig. 1A). A relatively high proportion of uncertain compounds (9.43%) highlighted the need for further exploration of novel metabolites in PL.

Table 1.

Structural similarity analysis of CYP71 AN24.1 and UGT91 A1.1 enzymes

| Proteins | TM-Score | RMSD |

|---|---|---|

| CYP71 AN24.1-PmCYP71 AN24 | 0.91391 | 2.10 |

| CYP71 AN24.1-PdCYP71 AN24 | 0.91389 | 2.08 |

| CYP71 AN24.1-CYP71 AN24.2 | 0.93376 | 2.35 |

| CYP71 AN24.1-CYP71 AN24.3 | 0.93397 | 2.19 |

| CYP71 AN24.1-CYP71 A1.1 | 0.96939 | 0.97 |

| CYP71 AN24.1-CYP71 A1.2 | 0.92852 | 1.86 |

| CYP71 AN24.1-CYP71 A1.3 | 0.93104 | 1.77 |

| PmCYP71 AN24-PdCYP71 AN24 | 0.99918 | 0.23 |

| UGT91 A1.1-UGT91 C1.1 | 0.88751 | 2.30 |

| UGT91 A1.1-UGT79B9 | 0.83668 | 2.50 |

| UGT91 A1.1-GpUGT91 A1 | 0.87196 | 2.24 |

| UGT91 A1.1-GmUGT79 A6 | 0.82362 | 2.85 |

| GpUGT91 A1- GmUGT79 A6 | 0.91325 | 2.27 |

| UGT89B2-UGTB9 A2 | 0.94566 | 1.82 |

| UGT89B2-SrUGT89B2 | 0.94804 | 1.64 |

| UGT89B2-SmUGT89B2 | 0.95613 | 1.80 |

| SrUGT89B2- SmUGT89B2 | 0.96696 | 1.31 |

Fig. 1.

Classification and differential metabolites analysis of Paeonia Lactiflora Pall. A Classification of Paeonia Lactiflora Pall. compounds based on the HMDB database. B Principal component analysis (PCA) Scores Plot among different tissues (flower, fruit, leaf, root). C Heatmap based on hierarchical clustering analysis among different tissues (flower, fruit, leaf, root). Upregulated and downregulated genes are shown in red and green, respectively. D Orthogonal projection to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) scores plot between leaf and root. E Response permutation test plot (n = 6) for the OPLS-DA model between leaf and root. F Venn diagram of DEMs in the Flower_vs_Root, Fruit_vs_Root, and Leaf_vs_Root groups

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to identify metabolite differences between groups and assess variability within groups. PCA results showed that PC1 and PC2 explained 39.3% and 29.8% of the total variance, respectively, with a cumulative contribution of 69.1%. Samples clearly clustered by tissue, indicating significant metabolite differences (Fig. 1B). PCA score plots also showed tight clustering of Quality Control (QC) samples, indicating good repeatability and stability of the analytical system. Hierarchical clustering heatmaps confirmed good biological duplication within sample groups and significant variation between groups (Fig. 1C).

Orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and model validation (Fig. 1D, 1E) demonstrated clear differentiation among all tissues, confirming model stability and reliability. Differential metabolites were identified using variable importance in projection (VIP) analysis, with fold change (FC) ≥ 2 or ≤ 0.5 and VIP ≥ 1 as criteria, resulting in 368 significantly different metabolites. Since medicinal properties of PL primarily derive from the roots containing numerous pharmacologically active substances, this study focused on distinguishing metabolic differences between the medicinal and non-medicinal parts. The “Fruit_vs_Root” comparison identified 135 DEMs (93 upregulated and 42 downregulated). The “Leaf_vs_Root” comparison had 122 DEMs (72 metabolites upregulated and 50 downregulated). The “Flower_vs_Root” had the fewest DEMs, with 60 metabolites upregulated and 51 metabolites downregulated. DEMs across three comparisons are shown in Additional Table 2. The higher number of DEMs involving the roots suggested that the medicinal use of PL roots is linked to their unique pharmacological constituents. A Venn diagram (Fig. 1F) of DEMs illustrated 74 common DEMs among three comparison groups, suggesting shared metabolic pathways or regulatory mechanisms across tissues.

Table 2.

Plant UGTs from other species with annotated functions and special modification sites

| Gene ID | Accession No | Species | Group | UGT family | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtUGT71B6 [59] | NC_003074.8 | Arabidopsis thaliana | E | 71 | Abscisic acid uridine diphosphate glucosyltransferases |

| BvUGT73 C10 [60] | JQ291613.1 | Barbarea vulgaris subsp. Arcuata | D | 73 | Sapogenin 3-O-glucosyltransferases |

| PgUGT73 AL1 [40] | KT159806.1 | Punica granatum | D | 73 | Hydrolyzable tannin glucosyltransferases |

| HvUGT14077 [61] | NC_058522.1 | Hordeum vulgare subsp. Vulgare | D | 73 | anthocyanin 3'-O-beta-glucosyltransferase |

| HaUGT74B1 [62] | NC_035447.2 | Helianthus annuus | L | 74 | N-hydroxythioamide S-beta-glucosyltransferase |

| ApUGT74E(ApUGT5) [63] | NW_026137566.1 | Andrographis paniculata | L | 74 | neoandrographolide glucosyltransferases |

| AtUGT74 F2 [59] | NC_003071.7 | Arabidopsis thaliana | L | 74 | salicylic acid, benzoic acid, and athranilate glucosyltransferase |

| AtUGT75B1 [59] | NC_003070.9 | Arabidopsis thaliana | L | 75 | callose 1,3-beta-glucosyltransferases |

| AtUGT75B2 [59] | NC_003070.9 | Arabidopsis thaliana | L | 75 | callose 1,3-beta-glucosyltransferases, salicylic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, and other benzoates glucosyltransferase |

| GhUGT1 [64] | NC_053427.1 | Gossypium hirsutum | H | 76 | iridoid glucosyltransferase-like |

| GmUGT79 A6 [65] | NM_001288595.2 | Glycine max | A | 79 | flavonol 3-O-glucoside |

| AtUGT80B1 [59] | KJ396595.1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 80 | steryl glucosyltransferase | |

| PgUGT84 A2 [41] | NM_001426723.1 | Punica granatum | L | 84 | gallate 1-beta-glucosyltransferase-like/gallic acid 4-O-glucosides glycosyltransferase |

| CsUGT85 K11 [57] | AB847092.1 | Camellia sinensis | G | 85 | Aroma beta-Primeverosides glucosyltransferases |

| SrUGT85 C2 [66] | ON249035.1 | Stevia rebaudiana | G | 85 | steviolglycoside glucosyltransferase |

| VvGT16(VviUGT85 A2L5) [67] | XM_002263122.1 | Vitis vinifera | G | 85 | Nerol monoterpenyl β-d-glucosides |

| GmUGT88E3 [68] | NM_001248232.2 | Glycine max | E | 88 | isoflavone 7-O-glucosyltransferase |

| TwUGT88B1 [69] | MH414913.1 | Tripterygium wilfordii | E | 88 | triptophenolide glucoside |

| VvGT7(VviUGT88 A1L3) [58] | XM_002276510.2 | Vitis vinifera | E | 88 |

Monoterpenols, nerol, geraniol, and citronellol glucosyltransferase |

| VvGT14(VviUGT85 A2L4) [58] | XM_002285734.2 | Vitis vinifera | E | 88 | citronellol/monoterpenyl glucosyltransferase |

| ScUGT1 [70] | AB537178.1 | Sinningia cardinalis | E | 88 | 3-deoxyanthocyanidin 5-O-glucosyltransferase |

To further analyze metabolites abundance profiles across different tissues, K-means clustering analysis was performed. Metabolites were divided into five subclusters (Fig. 2). Subcluster_1 contained 283 metabolites significantly increased in roots, including terpenoids and glycosides such as albiflorin, benzoylpaeoniflorin, paeoniflorin, and paeonilactone C. Leaves contained 539 significantly accumulated metabolites, including 90 terpenoids, 34 fatty acyls, and 26 carbohydrates and conjugates. Flowers contained 296 significantly accumulated metabolites, mainly flavonoids, benzoic acids and derivatives, and organic acids and derivatives. Fruits contained 225 significantly accumulated metabolites, primarily terpenoids, flavonoids and fatty acyls. Notably, 48 metabolites showed highly accumulation in roots and fruits compared to flowers and leaves, primarily amino acids, peptides and analogues, benzoic acids and derivatives, terpenoids, and flavonoids. K-means analysis further clarified metabolites abundance patterns, revealing tissue-specific accumulation.

Fig. 2.

K-means clustering analysis of differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) among four tissues (root, leaf, fruit, flower)

KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted to explore functional classification of the DEMs from the three different comparisons. Results indicated that DEMs from three comparisons were enriched in similar pathways, including flavone and flavanol biosynthesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, amino acid biosynthesis, and ABC transporter pathway (Fig. 3). This suggested that secondary metabolites biosynthesis and transporter processes among different tissues might contribute significantly to the accumulation of pharmacologically active substances in root.

Fig. 3.

KEGG enrichment analysis of DEMs in four tissues of Paeonia Lactiflora Pall. A Flower_vs_Root, (B) Fruit_vs_Root, (C) Leaf_vs_Root. Numbers indicate enriched metabolites in each term, the Top 20 most significant categories with p value < 0.05 are shown

Transcriptome profiling of different PL tissues

Twenty cDNA libraries were constructed and sequenced from root, leaf, flower, and fruit tissues of PL. After quality assessment and removal of low-quality data, 853,423,688 high-quality reads were obtained and assembled into 289,313 unigenes. These unigenes had an average length of 394 bp, average GC content of 45.78%, and an N50 of 410 bp. Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) assessment indicated 90.02% of transcripts were complete, while 7.81% were missing. Overall, 28,556 (81.63%) unigenes were annotated by BLAST searches against five public databases. Specifically, 22,613 (64.64%), 27,223 (77.82%), 15,548 (45.46%), 16,194 (46.29%) and 15,904 (45.46%) unigenes were annotated in the Swiss Prot, Non-redundant (Nr), Gene Ontology (GO), eukaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases, respectively. Unigenes annotated in the GO database were mainly classified into three categories with 58 GO terms. Within biological process, cellular component, and molecular function, the largest GO terms were “cellular process”, “metabolic process”, “cell part”, “organelle”, “catalytic activity”, and “binding”, respectively (Additional Fig. 1). Unigenes annotated in KEGG were primarily associated with “genetic information processing”, “signaling and cellular processes”, “metabolism”, and “signal transduction” pathways (Additional Fig. 2).

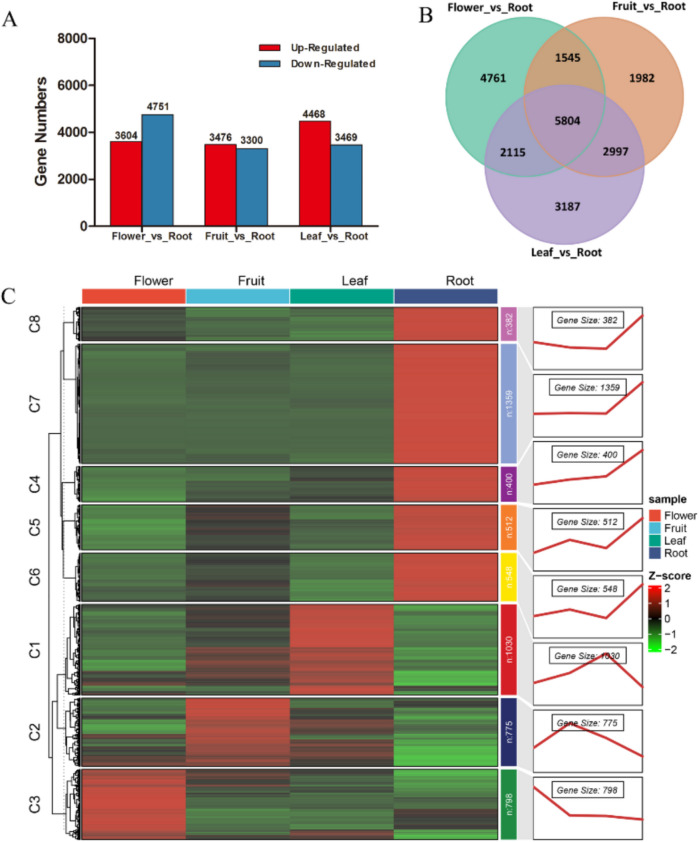

Using criteria of |log2 (fold change)|≥ 1 and P < 0.05, 23,068 significant DEGs were identified across three comparisons, with 5804 DEGs common to all comparisons (Fig. 4A). The “Flower_vs_Root” comparison had the highest number of significant DEGs, including 3604 upregulated and 4751 downregulated genes (Fig. 4B), indicating profound transcriptional divergence. In “Fruit_vs_Root” and “Leaf_vs_Root” comparisons, upregulated DEGs numbered 3476 and 4468, respectively, while downregulated DEGs numbered 3300 and 3469, respectively. To further analyze the differences among tissues, expression trends of DEGs were clustered into eight modules (Fig. 4C). Module C1 contained 1030 enriched genes highly expression in Leaves. Modules C2 (775 genes) and C3 (798 genes) exhibited increased expression in fruits and flowers, respectively. Modules C4-C8 showed similar trends, with sharply increased expression in roots compared to other tissues. The clustering highlighted distinct expression patterns in each tissue.

Fig. 4.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in three comparison groups (Flower_vs_Root, Fruit_vs_Root, Leaf_vs_Root). A Number of significant upregulated and downregulated DEGs across comparisons. B Venn diagram of overlapping DEGs among three comparison groups. C Cluster analysis of DEGs illustrating expression trends across modules

To elucidate biological functions, significant DEGs underwent GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. GO enrichment analysis revealed significant downregulated DEGs in Flower_vs_Root enriched in “secondary metabolic process”, “isoprenoid metabolic process”, “terpenoid metabolic process”, “hormone metabolic process”, “monooxygenase activity”, “glucosyltransferase activity” and “oxidoreductase activity” (Additional Fig. 3). Significant upregulated DEGs enriched in “flavonoid metabolic process”, “photosynthesis”, “phosphatase activity”, and “carboxylic ester hydrolase activity”. KEGG enrichment analysis showed significant downregulated DEGs primarily in “Plant − pathogen interaction”, “MAPK signaling pathway”, “Plant hormone signal transduction”, “Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450”, and “Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis”. Significant upregulated DEGs primarily enriched in “Photosynthesis”, “Stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis”, “Flavonoid biosynthesis”, and “Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis”. DEGs in the other two comparisons showed similar GO and KEGG enrichment patterns (Additional Fig. 4 and 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of CYP450 s (A) and UGTs (B). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using Muscle alignment and the Maximum-likelihood method. Bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates) was used to evaluate tree quality. Different CYP450 s and UGTs families were color-coded. The outer heatmap in the CYP450 s phylogenetic tree illustrated differential expression levels across four tissues. Expression data were normalized and centered, ranging from −2 to 2

For MGs biosynthesis, 56, 12 and 11 unigenes were involved in Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (ko00900), Monoterpenoid biosynthesis (ko00902), and Limonene and pinene degradation (ko00903) pathway, respectively. For GGs biosynthesis, 40 unigenes were involved, primarily associated with Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis(ko00400), Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (ko01110), and Metabolic pathways (ko01100). For flavonoids biosynthesis, 134, 35 and 22 unigenes participated in Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940), Flavonoid biosynthesis (ko00941), and Isoflavonoid biosynthesis (ko00943) pathway, respectively. Additionally, 24, 22 and 80 DEGs related to MGs, GGs and flavonoids biosynthesis were identified in Fruit_vs_Root; 22, 20 and 89 DEGs in Flower_vs_Root; and 26, 22 and 87 DEGs in Leaf_vs_Root, respectively.

Identification of candidate CYP450 s and UGTs in MGs, GGs and flavonoids biosynthesis

Research on MGs biosynthesis primarily focused on upstream genes, while downstream genes such as cytochrome P450 (CYP450 s) and UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGTs) remained unclear. Genome-wide analysis identified 249 CYP450 s and 85 UGTs. After removing short sequences (< 1000bp), 131 CYP450 s and 50 UGTs remained. To predict the enzyme functions, nonredundant CYP450 s and UGTs with complete open reading frames (ORFs) were classified into clans via phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 5).

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that 31 different CYP450 s in the CYP71 clan (Fig. 5A), including three from the CYP71D, ten from the CYP71 A, and seven from the CYP76 subfamilies. The CYP 71 clan is involved in plant monoterpene metabolism. Remarkably, CYP71 AN24.1, CYP71 AN24.2, CYP71 AN24.3, CYP71 AU50.2, CYP71E1, CYP71E7.2, CYP76B10.2, CYP82 A3.3, and CYP78 A6 exhibited substantially elevated expression in roots compared to other tissues. These genes demonstrated moderate to high root-specific expression, with τ index values ranging from 0.689 to 0.955 (Additional Table 3). Based on both expression and gene family analysis, these nine CYP450 genes were identified as candidate genes for paeoniflorin biosynthesis.

Table 3.

Primers details for genes detection by RT-qPCR

| Gene name | Primer sequence (5` → 3`) |

|---|---|

| Plactin-F | TTGTGCTGGATTCTGGTGATGGTG |

| Plactin-R | AGACGGAGGATAGCGTGAGGAAG |

| GLOS1-F | TGGCAAAGGGTCTACGCAAAGTG |

| GLOS1-R | CGGTGGGTAAATCGGCTCAATCTC |

| PLY8-F | CCGCCACGCTGTCATCCAAG |

| PLY8-R | GGACATTCGCTCCACGACCATC |

| CHSY-F | ACGAGGAAGAGGTCACTTGAGGAAG |

| CHSY-R | ACGCTATGCAACACAACGGTCTC |

| COMT1-F | GTGGTTGATGTTGGCGGAGGTC |

| COMT1-R | CCAGGATAGTGTTGGGCGTGTTG |

| DXS-F | TTGACGGCACAATAAAGTGGAGACC |

| DXS-R | TACTGTTGCTGCGATATGAGATGGC |

| SDR1-F | ATTGTGGTGTTGGCAGCTAGAGATG |

| SDR1-R | AAGCCGCAAGGGAAGCAATACTAG |

| RLC1-F | CGATGCTAGTCAGTGAAGTGGAACC |

| RLC1-R | CACTGCTGCTGCTGTTGTTGTTG |

| FLS-F | AAGACGACCGTTGGATTGATGCC |

| FLS-R | CACGCTCCTGTACTTGCCATTACTC |

| 4 CL2-F | GAAGCCACGGAACGAACCATAGAC |

| 4 CL2-R | AGCCACCTGGAAACCCTTGTATTTG |

| F3PH-F | CCGCATCAGTCTCTAGCCTCATTG |

| F3PH-R | GACGCCGCCACCACAACATC |

| HMGR-F | CCACATCTCAGTTACCATGCCTTCC |

| HMGR-R | ACCTTTCACACCCAGCAAGTTCAG |

| TPS05-F | TCAGCCCATATACCGCAAGGAAATG |

| TPS05-R | AGGACTGCCCTGGACCACATG |

During phylogenetic analysis, several candidate UGT genes related to MGs biosynthesis were identified by comparison with functionally characterized UGT genes from other species. Seventeen UGTs belonging to the UGT76, UGT709, UGT85, UGT86, UGT88, and UGT91 subfamilies were identified as potentially involved in MGs biosynthesis in PL. However, only UGT88 A1(τ = 0.731) and UGT91 A1.1 (τ = 0.941) exhibited higher expression levels in roots compared to other tissues. Their τ index values indicate moderate and strong root-specific expression, supporting their roles as candidate UGTs in monoterpenes glycosylation.

Additionally, several UGT subfamilies associated with of flavonoid glycosides and gallic glycosides biosynthesis were identified. A total of 24 UGT genes from UGT71, UGT73, UGT75, UGT79, UGT88, UGT89, UGT90, and UGT92 subfamilies were potentially involved in flavonoid glycoside biosynthesis. Among these, UGT71 A15.2, UGT71 A16, UGT71 K1, UGT71 K2, UGT73 C6, UGT73 C25, UGT75L6, UGT75L17.1, UGT88 F3.3, and UGT89B2 were clearly annotated with functions including anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase, tetrahydroxychalcone-2’-glucosyltransferase, anthocyanidin 5,3-O-glucosyltransferase, phloretin 4'-O-glucosyltransferase and flavonol 5-O-glucosyltransferase, respectively. The remaining 14 UGTs were considered novel candidate genes for flavonoid biosynthesis.

Notably, the UGT88 family displayed broad substrate specificity. In the phylogenetic tree, UGT88 F3.3 clustered closely with UGT88 F3.1 and ScUGT1. Given that UGT88 F3.3 and ScUGT1 function as anthocyanidin 5,3-O-glucosyltransferases, UGT88 F3.1 was speculated to have a similar role. Additionally, UGT88 A1 clustered with monoterpenoid glucosyltransferases VvUGT7, TwUGT88B1, and GmUGT88E3, suggesting its involvement in terpenoid biosynthesis. Genes potentially involved in gallic glycoside biosynthesis included UGT84 A24.1 and UGT84 A24.2.

In summary, nine CYP450 s and two UGTs were identified as new candidate genes for MGs biosynthesis, while 16 UGTs were identified for flavonoids biosynthesis. This analysis highlighted the efficacy of using phylogenetic trees to explore gene function and substrate specificity, providing important candidate genes for further studies.

Expression patterns and pathway mapping of key DEMs and DEGs associated with MGs, GGs and flavonoids biosynthesis

To further identify key structural genes and examine tissue-specific expression patterns of MGs, GGs and flavonoids, DEGs and DEMs involved in these metabolic processes were mapped onto their respective metabolic pathway.

A comprehensive annotation identified for 46 transcripts related to the MGs biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 6). Enzyme genes involved in MGs biosynthesis were categorized into four groups: 14 genes, including Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (ACAT), hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGS), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR), mevalonate kinase (MVK), phosphomevalonate kinase (PMVK), and diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase (MVD) were involved in the MVA pathway; nine genes, including 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS), 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR), 2-C-mehyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidyltransferase 2 (ISPD2), 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase (ISPE), 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphoaphate synthase (ISPF), 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate synthase (ISPG), and 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate reductase (ISPH), participated in the MEP pathway; four genes, including cinnamoyl-CoA hydratase/dehydrogenase (CHD), ketoacyl-CoA thiolase 1 (KAT1), 1,4-dihydroxy-2- naphthoyl-CoA thioesterase 1 (DHNAT1), and benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (BALDH), belonged to the benzoic acid pathway; and 19 genes, including isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase (IDI2), geranyl diphosphate phosphohydrolase (GPPS), (-)-alpha-terpineol synthase (PIN), Benzyl Alcohol Acetyltransferase (BAHD), CYP71, CYP76, CYP78, CYP82, UGT88, and UGT91, were associated with the down-stream pathway.

Fig. 6.

Schematic diagram of the proposed monoterpene glycosides (MGs) biosynthesis pathway, including mevalonate (MVA) pathway, methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway, benzoic acid biosynthesis (non-β-oxidative and core β-oxidative) pathway, and monoterpene modification and glycosylation. DEMs are highlighted in red font alongside heatmaps; DEGs are labeled in black font alongside heatmaps. Solid arrows represent single-step reactions; and dashed arrows represent multi-step reactions. Black and red abbreviations adjacent to arrows indicate validated and unverified enzymes, respectively. Corresponding full enzyme names and compounds names are provided in the Abbreviations section

Expression levels of key enzyme genes in the MVA and MEP pathways were significantly elevated across all tissues. However, 16 enzyme genes, including DXS2, MVK, MVD2, GPPS, PIN.3, CYP71 AN24.1, CYP71 AN24.2, CYP71 AN24.3, CYP71E1, CYP71E7.2, CYP71 AU50.2, CYP76B10.2, CYP78 A6, CYP82 A3.3, UGT88 A1, and UGT91 A1.1, exhibited notably higher expression levels in roots than other tissues. Except for DXS2 gene in MEP pathway and MVK, MVD2 in MVA pathway, the remaining 14 highly expressed genes primarily functioned in the final stages of MG biosynthesis. This finding suggests that later-stage MG biosynthesis r predominantly occurs in roots.

A total of 20 DEMs were classified as monoterpenes and MGs, including four major active components—paeoniflorin, oxypaeoniflorin, albiflorin, and benzoylpaeoniflorin—in PL. Nine MGs, including paeoniflorin, albiflorin, oxypaeoniflorin, benzoylpaeoniflorin, demethyloleuropein, aucubin, verbenalin, oleuropein, and suspensolide F accumulated predominantely in roots. In contrast, compounds such as neryl arabinofuranosyl-glucoside, lyciumoside IV, cinnamoside, oleoside 11-methyl ester, (1R*,2R*,4R*,8S*)-p-menthane-1,2,8,9-tetrol 9-glucoside, valtrate, and pisumionoside were premarily abundant in leaves. Notably, oxypaeoniflorin and oleoside 11-methyl ester were highly accumulated in both roots and fruits. Furthermore, benzoic acid and its derivatives, important as benzoyl ligands of MGs, were of particular interest. Five benzoic acid derivatives identified among DEMs, included orsellinic acid, 3,4-dihydroxy-5-(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoyloxy) benzoic acid, 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid, and 2,4,6-trihydroxybenzoic acid. Orsellinic acid accumulated predominantly was highly accumulated in roots, while 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid, and 2,4,6-trihydroxybenzoic acid were mainly enriched in fruits.

Ten DEGs and 14 DEMs were mapped onto the GGs biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 7). While 6-cinnamoyl-1-galloylglucose and 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)−1,2-propanediol 2-O-(galloyl-glucoside) (HMP-GG) were predominantly found in leaves and roots, respectively, most GGs and intermediates such as shikimic acid, gallic acid, and m-trigallic acid were concentrated primarily in flowers and fruits. Correspondingly, aside from UGT84 A24.2 and DHS dehydratase (AroZ), which showed high expression in roots, other GGs biosynthetic genes were mainly expressed in flowers, fruits and leaves. DAQ synthase.1(AroB.1), shikimate dehydratase (AroE), and UGT84 A24.1 were highly expressed in fruits, while DAQ synthase.2 (AroB.2) was highly expressed in leaves.

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram of the proposed gallaglycosides (GGs) biosynthesis pathway. DEMs are highlighted in red font alongside heatmaps; DEGs are labeled in black font alongside heatmaps. Solid arrows represent single-step reactions; and dashed arrows represent multi-step reactions. Black and red abbreviations adjacent to arrows indicate validated and unverified enzymes, respectively. Corresponding full enzyme names and compounds names are provided in the Abbreviations section

Similarly, 63 DEGs and 52 DEMs were mapped to the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 8). Enzymes involved in the flavonoids biosynthesis included phenylalanine ammonialyase (PAL), cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4 CL), CHS, CHI, F3H, flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase (F3’H), flavonoid 3′5’-hydroxylase (F3′5’H), flavonol synthase (FLS), DFR, isoflavone synthase (IFS), isoflavone O-methyltransferase (IOMT), vestitone reductase (VR), 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase (HID), trans-resveratrol di-O-methyltransferase (ROMT), CYP81Q32, UGT, leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR) and anthocyanidin reductase (ANR). Most enzyme genes (54/63) were highly expressed in flowers, fruits and leaves. However, nine genes (4 CLL6.1, IOMT3.1, ROMT.1, CYP81Q32.6, UGT88 F3.1, UGT73 C25, UGT89B2, LAR, and ANS) showed high expression in roots. Similarly, most flavonoids (34/52) accumulated in the flowers, fruits and leaves. Conversely, 18 flavonoids and flavonoid glycosides, including flavan-3-ols (pinocembrin and catechin), proanthocyanidins (procyanidin B2, procyanidin C1 and procyanidin B5), anthocyanidins (leucopelargonidin), anthocyanins (cinnamtannin A2), isoflavonoids (pseudobaptigenin, isoformononetin, isoliquiritin), flavonoid glycosides (isoliquiritin, eriodictyol 7-(6-galloylglucoside)), narigenin, 2’,4’,6’-trihydroxydihydrochalcone, hesperetin, hesperidin, luteolin and loquatoside were highly accumulated in roots.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of the proposed flavonoids biosynthesis pathway. DEMs are highlighted in red font alongside heatmaps; DEGs are labeled in black font alongside heatmaps. Solid arrows represent single-step reactions; and dashed arrows represent multi-step reactions. Black and red abbreviations adjacent to arrows indicate validated and unverified enzymes, respectively. Corresponding full enzyme names and compounds names are provided in the Abbreviations section

Notably, some enzyme genes and their corresponding metabolites, such as ANR and procyanidin B2, showed both highly expression and accumulation in roots. However, inconsistency between gene expression and metabolite accumulation within the same tissue occurred. For instance, CHSY.1 did not show peak expression in roots despite high chalcone concentrations, suggesting chalcone may be synthesized elsewhere and subsequently transported to the roots. These results implied that not all identified enzyme genes are directly responsible for the corresponding metabolites, or that biosynthesis and ultimate metabolite accumulation might occur in the different tissues.

The phenylpropanoid pathway contained multiple downstream branches, with lignin and flavonoid pathways as two major branches. This pathway also produced several phenolic compounds as lignin precursors. Six DEMs and sixteen DEGs were identified. DEMs were mainly phenolic acids, including caffeic acid and its derivatives (trans-caffeic acid ester, cryptochlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, and trans-ferulic acid), which accumulated significantly in leaves and fruits. Notably, paeonol was highly accumulated in roots. DEGs included key enzyme genes involved in lignin biosynthesis, namely caffeate/5-hydroxyferulate 3-O-methyltransferase (COMT), caffeoyl CoA 3-O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), caffeoyl shikimate esterase (CSE), HCT, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), feruloyl CoA ortho-hydroxylase 3 (F6H13) and omega-hydroxypalmitate O-feruloyl transferase (HHT). Specifically, COMT1.2, COMT1.3, and CSE were predominantly expressed in flowers, CCoAOMT.3, CCR1.1, CAD1.1, and CAD6 in fruits, CCoAOMT.2 in leaves, and COMT1.1 in roots.

Integration analysis of transcriptome and metabolome data in PL

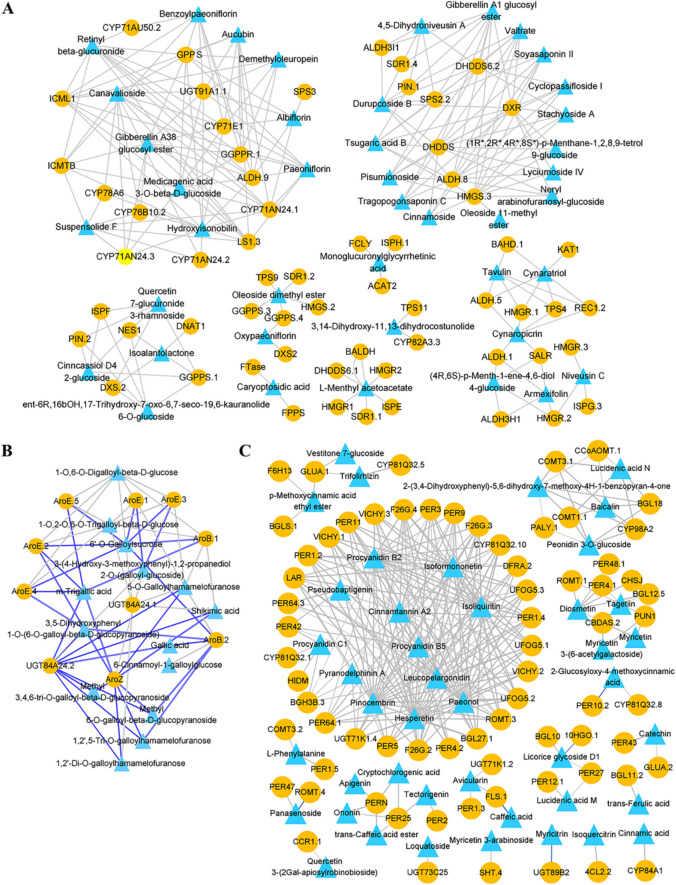

To clarify relationships between metabolites and genes related to MGs, GGs, and flavonoids, correlation network analysis was performed for DEMs significantly accumulated in roots (r > 0.98). In the MGs biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 9A), several genes including geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), aldehyde dehydrogenase 9 (ALDH.9), CYP71E1 and UGT91 A1.1 were strongly correlated with paeoniflorin, albiflorin and benzoylpaeoniflorin. Paeoniflorin also showed strong correlation with isoprenylcysteine alpha-carbonyl methylesterase 1 (ICML1) and CYP71 AN24.1; albiflorin closely correlated with CYP71 AN24.1 and solanesyl diphosphate synthase 3 (SPS3); and benzoylpaeoniflorin closely correlated with ICML.1, geranylgeranyl diphosphate reductase (GGPPR.1), CYP71 AU50.2 and isoprenylcysteine O-methyltransferase B (ICMTB). Additionally, oxypaeoniflorin displayed significant correlations with geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPS.3) and DXS2. In the GGs biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 9B), 1-O,6-O-digalloyl-beta-D-glucose (2GG) and 1-O,2-O,6-O-trigalloyl-beta-D-glucose (3GG) were highly positively correlated with UGT84 A24.1, AroB.1 and AroE.4, while 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)−1,2-propanediol 2-O-(galloyl-glucoside) (1GG) strongly correlated with UGT84 A24.2 and AroZ.

Fig. 9.

Correlation network of DEGs and DEMs related to (A) monoterpene glycosides (MGs), (B) gallaglycosides (GGs), and (C) flavonoids. Yellow circles represent DEGs and blue triangles represent DEMs. Grey edges indicate positive correlations, and blue edges indicate negative correlations between DEGs and DEMs

In the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 9C), flavonoids abundant in roots—such as hesperetin, pinocembrin, paeonol, isoformononetin, isoliquiritin, pyranodelphinin A, procyanidin B2, leucopelargonidin, cinnamtannin A2, procyanidin B5, pseudobaptigenin, and procyanidin C1— were highly correlated (r > 0.98) with genes including ten peroxidases (PER), three furostanol glycoside 26-O-beta-glucosidase (F26G), one DFR, three anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFOG), three vicianin hydrolase (VICHY), one ROMT, two beta-glucosidase (BGL), one LAR, two CYP81Q32, one UGT71 K1, and one HID. Notably, UGT71 K1.4 was identified as a newly discovered glycosyltransferase involved in flavonoid glycosylation, while the other genes were associated with flavonoids biosynthesis pathways (ko00940, ko00941, ko00943).

To further identify key biosynthetic and regulatory genes involved in three main constituents of PL, Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) was performed to explore gene modules with synergistic expression patterns. After filtering low-expression genes (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments, FPKM < 10), 6028 unigenes were classified into seven different modules. Different colors represented distinct co-expression modules (Fig. 10A, B).

Fig. 10.

Correlation analysis between modules and physiological traits using WGCNA. A Gene clustering dendrogram; and (B) Module heatmap of 6028 unigenes among tissues. C Relationships between module and constituent contents. D Eigengenes expression patterns of seven WGCNA clustering modules across tissues. E KEGG enrichment scatterplots of turquoise, green, and blue modules

The WGCNA revealed that the turquoise, green and blue modules significantly correlated with MGs and flavonoids, including paeoniflorin, albiflorin, benzoylparoniflorin, oxypaeoniflorin, procyanidin B2, procyanidin B5 and cinnamatannin A2 (Fig. 10C). In addition, paeonol, paeonilactone C and 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)−1,2-propanediol 2-O-(galloyl-glucoside) (HMP-GG) showed similar patterns. The turquoise module exhibited the highest positive correlation, while the green and blue modules showed negative correlations. The turquoise module was characterized by significant upregulation of DEGs in roots (Fig. 10D). Genes in this module were significantly enriched in ribosome, metabolic pathways, spliceosome, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and nucleocytoplasmic transport by KEGG (Fig. 10E). The blue module was enriched in metabolic pathways, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathways, whereas the green module was significantly enriched in metabolic pathways (Fig. 10E).

The blue and yellow modules showed significant positive correlations with the contents of 2GG, 3GG and 3,4-dihydroxy-5-(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoyloxy) benzoic acid (BA). Additionally, green and black modules positively correlated with gallic acid (GA), 2,4,6-Trihydroxybenzoic acid, and 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid. These modules exhibited significant upregulation of DEGs in fruits and flowers (Fig. 10D). Clustering results indicated that genes in the blue, green and turquoise modules were likely involved in MGs, GGs and flavonoids biosynthesis, highlighting the need for further detailed studies based on these modules.

Moreover, hub gene related to MGs and flavonoids were identified by Cytohubba, and the top 20 genes were displayed in the co-expression networks. Three, five and sixteen structural genes associated with the MGs were found in turquoise, green and blue modules (Fig. 11A-C), respectively, while eight, two and eight structural genes associated with the flavonoids (Fig. 11D-F) were found in the same modules. Specifically, CYP71 AN24.1, MVD2, and FOLK in the turquoise module, ISPH, BADH.2, FNTA, FACE1, and ACAT2 in the green module, and HMGCS.1, ISPG, ACAT1, SDR1.1, GGPPS, BALDH, AL3H1, FPPS1, IDI2, PMK, HMGR.1, HMGR2, HMGR.2, and HMGS.2 in the blue module were identified as MG-related hub genes. PER42, CAD1.2, MTDH.2, F26G, PER52, CCoAOMT.1, F3H, and UGT89B2 in the turquoise module, UGT74G1.1 and MTDH.1 in the green module, MTDH.3, UGT89 A2, BGL11.2, UGT1, CAD1.1, UGT88 F3, 4 CL2.1, and CCL7 in the blue module were identified as flavonoids-related hub genes.

Fig. 11.

Co-expression networks of the top 20 DEGs related to MGs and flavonoid in different modules by WGCNA. A-C Co-expression network of MGs. D-F Co-expression network of flavonoids. A, D Turquoise module. B, E Green module; C, F Blue module

Structural similarity of candidate CYP450 s and UGTs

To functionally validate the roles of the candidate genes CYP71 AN24.1, UGT91 A1.1, and UGT89B2, identified through integrated omics analysis, ESMfold and TM-align were employed for comparative structural modeling and similarity assessment. The predicted tertiary 3D structures of these enzymes revealed conserved catalytic domains critical for substrate binding (Fig. 12). Quantitative structural comparisons further demonstrated significant divergence between their homologs and paralogs (Table 1). CYP71 AN24.1 exhibited hierarchical conservation pattern across multiple evolutionary scales. It demonstrated exceptionally high conservation with CYP71 A1 subfamily members (TM-score: 0.928–0.969; RMSD: 0.97–1.86 Å). Notably, its closest structural homolog, CYP71 A1.1, exhibited near-perfect alignment (TM-score = 0.969, RMSD = 0.97 Å), strongly indicating a highly conserved catalytic mechanism within this subfamily. Furthermore, CYP71 AN24.1 maintained high structural similarity with its paralogs CYP71 AN24.2 and CYP71 AN24.3 (TM-score: 0.933 for both; RMSD: 2.19–2.35 Å), suggesting evolutionary constraints preserving core structural features despite potential functional diversification. It exhibited slight structure divergence from its orthologs PdCYP71 AN24 (TM-score: 0.913; RMSD: 2.08 Å) and PmCYP71 AN24 (TM-score: 0.913; RMSD: 2.10 Å), implying potential functional differentiation between CYP71 AN24.1 and its orthologs in species such as Prunus mume and Prunus dulcis. Exceptional conservation between PmCYP71 AN24 and PdCYP71 AN24 (TM-score = 0.999, RMSD = 0.23 Å), indicated strict functional conservation of this enzyme across closely related Prunus species.

Fig. 12.

Structural prediction and similarity analysis. A-C Predicted tertiary 3D structures of CYP71 AN24.1, UGT91 A1.1 and UGT89B2. D-F Superimposed structures of CYP71 AN24.1 and PmCYP71 AN24, UGT91 A1.1 and GpUGT91 A1, UGT89B2 and SrUGT89B2

Based on the provided TM-score and RMSD values (Table 1), UGT91 A1.1 displayed moderate structural conservation with its homologs (TM-score: 0.824–0.888; RMSD: 2.24–2.85 Å). However, discernible variations suggest evolutionary and functional divergence. Notably, UGT91 A1.1 exhibited greater structural divergence from the flavonoid-specific glycosyltransferase GmUGT79 A6 (TM-score = 0.824, RMSD = 2.85 Å) compared to other proteins, suggesting potential functional differentiation in substrate recognition. Similarly, structural dissimilarity from gypenoside-modifying GpUGT91 A1 (TM-score = 0.872, RMSD = 2.24 Å) was evident. In contrast, UGT89B2 exhibited remarkable structural conservation (TM-score > 0.94, RMSD < 1.82 Å) with its homologs UGT89 A2, SrUGT89B2 and SmUGT89B2, showing particularly high similarity to SmUGT89B2. This evolutionary convergence suggests UGT89B2 likely functions in rutin biosynthesis rather than steviol glycoside modification.

qRT-PCR validation

To verify the reliability of the transcriptome data, twelve DEGs underwent qRT-PCR validation. Three DEGs related to terpenoids biosynthesis, and nine DEGs associated with flavonoid biosynthesis were selected. Expression levels varied across PL tissues. Results revealed high consistency with RNA-seq data, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.8220 to 0.9999, and p values from 0.01 to 0.33 (Fig. 13). These findings confirmed the robustness of the RNA-seq data, providing a reliable foundation for further studies on terpenoids and flavonoids biosynthesis genes.

Fig. 13.

Correlation analysis between qRT-PCR and RNA-seq results. r represents Pearson`s correlation coefficient, p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance

Global biosynthesis networks

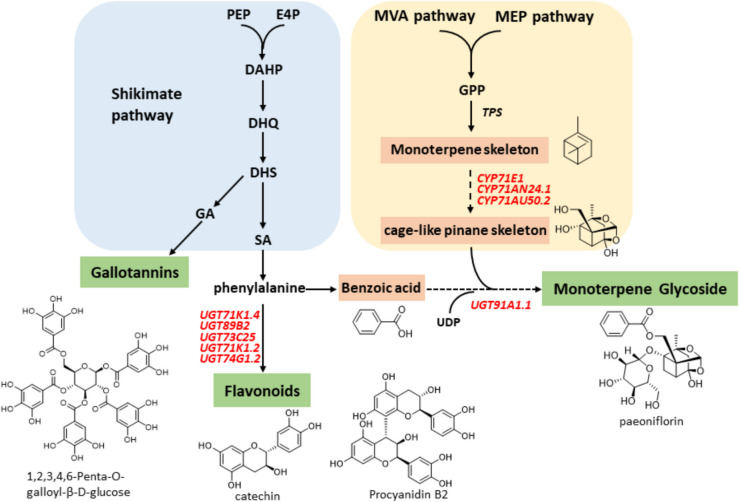

Integrated analysis of the three major active constituent pathways reveals an intricately interconnected metabolic network (Fig. 14). Central to this network is 3-dehydroshikimic acid (DHS), serving as a pivotal branch point. DHS is converted into gallic acid (GA) by AroE. UDP glycosyltransferases subsequently attach diverse glycosyl moieties, generating structurally varied galloylglycoside derivatives. DHS is also converted into shikimic acid (SA), leading to phenylalanine formation, a precursor of benzoic acid, flavonoids, and lignins. Additionally, benzoic acid derivatives act as acyl donors, transferring benzoyl groups to MGs through BAHD acyltransferases, establishing biochemical connectivity between phenylpropanoid and terpenoid pathways. These interconnected pathways suggest coordinated regulation of major active constituents in PL.

Fig. 14.

Schematic networks of main active constituent biosynthesis in Paeonia lactiflora Pall. Red fonts indicate novel candidate genes

Discussion

Paeonia lactiflora Pall. (PL) possesses significant ornamental, edible and medicinal value. It is the botanical source of the traditional Chinese medicine “Paeoniae Radix Alba” (Baishao) and “Paeoniae Radix Rubra” (Chishao), belonging to the Paeoniaceae family. Within this family, P. suffruticosa (PS) and P. veitchii (PV) are widely used as the original source for Moutan Cortex (Mudanpi) and Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), respectively. The roots of PS, PV, and PL share similar phytochemical profiles, predominantly containing MGs, GGs, and flavonoids, such as paeoniflorin, 3GG, catechin and their detrivatives. The characteristic cage-like pinane skeleton of MGs serves as a chemotaxonomic marker for the Paeoniaceae family [25]. Limited understanding of the biosynthesis of constituent biosynthesis and widespread distribution of Paeoniaceae plants have made this plant family a current research focus.

Metabolic and molecular basis of MGs in PL

MGs, particularly paeoniflorin, not only serve as marker compounds of PL but also critically contribute to its pharmacological activity. Metabolomics analysis indicated that MGs predominantly accumulate in roots, with eight MGs identified. Transcriptomics analysis further identified 16 highly expressed genes related to MGs biosynthesis in roots, primarily downstream genes (e.g., CYP71E1, UGT88 A1) involved in glycosylation and oxidative modification. This strongly supports the hypothesis that late-stage modification of MGs occurs mainly in roots.

Previous studies on MGs biosynthesis focused predominantly on upstream genes involved in terpenoid backbone pathway [6, 26]. Notably, Ma et al. [27] identified a terpene synthase PlPIN, which catalyzes the conversion of GPP to α-pinene and participates in the paeoniflorin biosynthesis.

This study also identified 29 genes in MVA/MEP pathways and monoterpene synthases associated with terpene skeletons biosynthesis. Zhang et al. [8] systematically reviewed paeoniflorin biosynthesis and proposed a hypothetical post-modification pathway, underscoring the importance of characterizing downstream MG biosynthetic enzymes.

CYP450 s and UGTs have been hypothesized to function in the terpenoid post-modification. Through phylogenetic and expression level analyses, nine candidate CYP450 s were identified. Current evidence indicates that CYP450 s involved in monoterpene biosynthesis primarily belong to the CYP71 Clan, especially CYP71 and CYP76 families [24]. Specifically, CYP450 s involved in cyclic monoterpenes biosynthesis largely belong to the CYP71 family, particularly the CYP71D subfamily [28]. Examples include CYP71D13 and CYP71D14 involved in menthol biosynthesis in spearmint [29], and CYP71 AV1 involved in linalool biosynthesis in Salvia officinalis. Additionally, CYP76 C1 participates in monoterpenoids metabolism at Arabidopsis [30]. These CYP450 enzymes significantly contribute to cyclization and functionalization of monoterpenoids through oxidation, thus contributing significantly to plants secondary metabolism.

Despite lacking clear functional annotation, the CYP71 A subfamily shares high homology with CYP71D members, justifying its priority in screening strategies. Additionally, CYP71E1, CYP71 AN24.1, and CYP71 AU50.2 exhibited strong positive correlations with key MGs enzyme genes based on correlation analysis. All three genes belong to the CYP71 clan. Integrative analyses combining expression profiles, and phylogenetic relationships, correlation analysis and WGCNA strongly support CYP71 AN24.1 as a novel candidate gene for MGs biosynthesis.

The hierarchical structural conservation of CYP71 AN24.1 provides valuable insights into its functional evolution. The enzyme's structural similarity to CYP71 A1.1 (TM-score = 0.969) strongly suggests conserved evolutionary functions. This alignment indicates a specialization in oxidizing or hydroxylating terpenoid or alkaloid substrates, supported by conserved active-site features observed in related CYP71 A oxidases [31]. While paralogs CYP71 AN24.2 and CYP71 AN24.3 retain core catalytic architecture (TM-score: 0.933), their elevated RMSD values (2.19–2.35 Å) align with the “core rigidity, periphery plasticity” paradigm observed in plant P450 enzyme [32].

To further narrow candidate UGTs, monoterpenoids biosynthesis pathways reported in other species were compared. Phylogenetic analysis identified 17 UGTs across six subfamilies (UGT76, UGT709, UGT85, UGT86, UGT88, UGT91) as potential contributors to MG biosynthesis in PL. Notably, UGT85, UGT709, and UGT76 subfamilies were implicated in P. veitchii MG biosynthesis [33, 34]. Root-specific expression profiling further narrowed candidate genes to UGT88 A1 and UGT91 A1.1. Correlation analysis combined with WGCNA identified UGT91 A1.1 as a candidate UGTs involved in MG biosynthesis.

UGTs modulates the structural diversity and bioactivity of plant secondary metabolites through glycosyltransferase reactions. UGT91 A1 demonstrates functional versatility, mediating anthocyanin glycosylation in Arabidopsis thaliana together with UGT79B1 [35], and gypenoside modification with CYP94 A1 in Gynostemma pentaphyllum [36]. Integrated multi-omics analysis identified UGT91 C1 and UGT91 A1 as highly active candidates in ginsenoside metabolism, although their mechanistic roles remain unclear [37]. Collectively, these findings suggest UGT91 A1 exhibits catalytic activity toward structurally diverse substrates, reflecting broad substrate selectivity and functional versatility.

In our study, UGT91 A1.1 exhibited notable structure divergence from flavonoid glycosyltransferase GmUGT79 A6 (TM-score = 0.82362, RMSD = 2.85 Å). Despite this divergence, UGT91 A1.1 showed substantial structural conservation with GpUGT91 A1 (TM-score = 0.87196, RMSD = 2.24 Å). Integrated WGCNA and tissue-specific expression profiles suggest UGT91 A1.1 preferentially facilitates terpenoid glycosylation rather than flavonoid glycosylation.

Metabolic and molecular basis of GGs in PL

GGs, the second most abundant constituents of the Paeoniaceae family, exhibit various pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and anticancer properties [38, 39]. Metabolomic profiling identified ten structurally distinct GGs, ranging from mono- to pentagalloyl esters conjugated to diverse glycosyl moieties—including hamamelofuranose, glucopyranoside, sucrose, and glucose. Transcriptomic analysis identified 14 biosynthetic genes associated with GGs biosynthesis, with spatial expression mapping highlighting root-specific biosynthesis. Shikimate pathway enzymes AroB and AroE mediate gallic acid synthesis, while UGT84 A subfamily members—particularly UGT84 A24.1—catalyze β−1-O-glucose ester formation via conserved nucleophilic acyl transfer, a signature reaction of plant galloyltransferases [40–42]. Correlation network analysis prioritized UGT84 A24.1, AroB.1, and AroE.4 as hub genes, suggesting strong transcriptional coordination between gallate supply and glycoside assembly.

Metabolic and molecular basis of flavonoids in PL

Flavonoids are among the most abundant compounds in PL, yet their therapeutic potential remains underexplored compared to MGs and GGs. Unlike the complex terpenoid pathways, flavonoids biosynthesis pathway of are relatively well-characterized. Previous studies on Paeonia flavonoids primarily focused on their roles in pigmentation and ornamental traits [11, 15], leaving pharmacological properties largely unexplored. Our integrated multi-omics approach identified 205 DEGs and 67 DEMs related to flavonoids biosynthesis. Metabolomic profiling revealed the accumulation of 18 flavonoids and their glycosides in the roots, whereas flavonoids typically concentrated in plant leaves, stems and flowers. These root-localized derivatives likely significantly contribute to PL's medicinal efficacy. Moreover, 21 candidate UGTs were identified through phylogenetic analysis. Four UGTs (UGT71 K1.4, UGT89B2, UGT73 C25, UGT71 K1.2) were identified by correlation analysis (r > 0.98). WGCNA further pinpointed 18 hub genes, including UGT1, UGT74G1.1, UGT88 F3, UGT89 A2 and UGT89B2, associated with flavonoid biosynthesis. Finally, overlap of phylogenetic relationships, WGCNA and tissue-specific expression patterns across tissues highlighted UGT89B2 as a root-specific glycosyltransferase candidate.

UGT89B2 exemplifies catalytic plasticity in plant secondary metabolism, demonstrating notable substrate promiscuity across species and substantial substrate heterogeneity. In Stevia rebaudiana, SrUGT89B2 is thought to be involved in steviol glycosides biosynthesis [43], while its ortholog SmUGT89B2 in Solanum melongena encodes a key enzyme in the rutin biosynthetic pathway [44]. Structural prediction and similarity analysis indicated that PlUGT89B2 shared greater structural conservation with SmUGT89B2, suggesting a preference for flavonoid glycoside modification rather than terpenoid modification. Although structural parallels imply specialization in flavonoid glycosylation, definitive biochemical validation of UGT89B2 in PL through heterologous expression and enzymatic assays remains essential.

In sum, this study provides a foundational framework for biosynthetic pathways of MGs, GGs, and flavonoids through correlated metabolite-gene networks, future research must include heterologous expression, enzyme assays, and genetic manipulation to confirm candidate genes (e.g., CYP71 AN24.1, UGT91 A1.1, and UGT89B2). Collectively, these findings enhance understanding of metabolic processes and molecular mechanisms underlying active constituent biosynthesis in PL.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Three-year-old PL plants were cultivated in the Germplasm Resources Garden of Zhejiang Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Sampling was conducted during peak flowering stage (late April to early May). Four distinct tissues—root, leaf, flower and young fruit—were sampled separately. Each sample was evenly divided into three portions: one for metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses, another for quantitative analysis, and the third for validation experiments. Six biological replicates per tissue were collected for robust metabolic profiling, and five replicates for RNA sequencing. After thorough removal of sediment, samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80℃ until further analysis.

Untargeted metabolome profiling

Samples were thawed slowly at 4℃. Subsequently, 200 mg of each sample was weighed, and 100µl of ice-cooled water was added. The mixture was ground using a ball mill until homogenization. Subsequently, 400µL of pre-cooled methanol/acetonitrile solution (1:1, v/v) was added for metabolite extraction. The solution was sonicated twice for 30 min at 4℃. Following centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 20 min, 4℃), the supernatant was vacuum-dried and then redissolved in 200 µL of 30% acetonitrile (v/v). After a second centrifugation (14,000 g, 15 min, 4℃), the supernatant was transferred to insert-equipped vials for metabolomics analysis.

Metabolites were analyzed using an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-Orbitrap MS) system (UPLC, Vanquish, Thermo, USA; MS, Q-Exactive, Thermo, USA) [45, 46]. A Waters HSS T3 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8μm) was used. The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid-aqueous solution (A) and 0.1% formic acid-acetonitrile-isopropyl alcohol (B), with gradient elution as follows: 0.0–2.0 min (90:10 A/B), 6.0–15.0 min (40:60 A/B), 15.1–17.0 min (90:10 A/B). Flow rate was maintained at 0.3 mL/min, column temperature was set at 40℃. The injection volume was 2µL. Samples were maintained in an automatic sampler at 4℃ during analysis. To minimize instrument viability, a random sequence was used for continuous analysis of samples. QC samples were inserted to monitor system stability and data reliability. MS data were acquired using a high-resolution mass spectrometry detection system with a heated electrospray ionization (ESI) source both in positive and negative ion mode. ESI parameters were set as follows: sheath gas pressure, 40 psi; auxiliary gas pressure, 10 psi; spray voltage, −2.8kV/3.0kV; auxiliary gas heater temperature, 350℃; capillary temperature 320℃.

Raw MS data were collected by Xcalibur 4.1 on the Q-Exactive and processed by Progenesis QI (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA). A data matrix including retention time, mass-to-charge ratio and peak intensity was obtained using both self-built database and public database (http://www.hmdb.ca/, https://metlin.scripps.edu/). Data preprocessing involved: (1) retaining variables with more than 80% non-zero values per sample group; (2) normalizing total peak intensity and filtered variables (RSD > 30%) in QC samples; (3) Converting data to log10 scale for subsequent analyses.

The data matrix was analyzed using R 4.2.3 (https://www.r-project.org/). Univariate statistical analyses (volcano plots, Venn diagram) and multivariate data analyses (PCA, OPLS-DA) were performed. Model robustness was evaluated by sevenfold cross-validation and permutation tests. Metabolites with the VIP ≥ 1 and FC ≥ 2 or fold change (FC) ≤ 0.5, along with p-value < 0.05, were considered statistically significant. K-means and hierarchical clustering heatmap analyses were performed using R package. Function annotation and enrichment analysis of DEMs was conducted using KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/compound/ and http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/pathway. html).

Transcriptome profiling

Total RNA was extracted and purified using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (TIANGEN, DP441, China). cDNA libraries were prepared with the U-mRNAseq Library Prep Kit (KAITAI-BIO, AT4221, China), following the manufacturer’s instruction. Libraries were sequenced with 2 × 150bp paired-end reads on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform by Novogene Co. Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Clean reads were obtained by removing adapters, low quality reads and those with an N ratio > 5%, and assembled using fastp 0.23.4 [47]. The transcripts were clustered into unigenes using TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL 65) [48]. Transcriptome assembly and annotation completeness were assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO 5.7.1) [49]. Raw transcriptome sequence data were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) [50] at the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa).

Unigene sequences were queried against public databases (GO, KEGG, Pfam, Nr, KOG and Swiss-Prot) using eggNOG 5.0.2 and diamond 2.1.9.163 software [51, 52]. Expression levels for each sample were estimated by RSEM 1.3.1 [53], and calculated based on FPKM values. Differentially expressed analysis among groups was performed using DESeq 1.42.1 [54]. P-values were adjusted using the BH algorithm to control the false discovery rate (FDR) [55]. Threshold of |log2 FC|≥ 1 and FDR < 0.05 were applied to identify DEGs. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed on each comparison to determine the functions of DEGs.

Phylogenetic analysis of CYP450 s and UGTs

Phylogenetic analysis integrated with expression profiling across four tissues was performed to screen CYP450 s and UGTs genes potentially involved of MGs, GGs, and flavonoids biosynthesis in PL. Reference sequences of CYP450 and UGT genes known from other plant species were included to assess functional relevance. Genome-wide identification of CYP450 and UGT family members was conducted, followed by exclusion of short sequences (< 1000 bp) and retention of nonredundant genes with complete ORFs. These genes were classified into clans based on phylogenetic clustering.

For CYP450 phylogenetic analysis, tissue-specific expression patterns were visualized as heatmaps alongside phylogenetic trees. For UGT analysis, candidate genes from PL were aligned with UGT homologs from Arabidopsis [56], tea [57], and grape [58]; detailed gene information (accession numbers and functions) is summarized in Table 2 [40, 41, 59–70]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA 11.0 [71] with the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method (1,000 bootstrap replicates). Results were visualized using the interactive tree visualization tool, tvBOT 2.5 (https://www.chiplot.online/tvbot.html) [72].

Genes exhibiting high roots-specific expression were prioritized among those functionally related to MGs, GGs and flavonoids biosynthesis. Additionally, the tissue-specificity τ index [73] was applied to evaluate root-enriched CYP450 and UGT candidates. The τ index ranged from 0 (housekeeping) to 1 (strictly tissue-specific), calculated as follows:

where N is the number of tissues, and is the normalized expression level (max-scaled) in tissue . Genes with τ > 0.85 were classified as highly tissue-specific, while 0.15 ≤ τ ≤ 0.85 showed moderate specificity.

Integration analysis of transcriptome and metabolome data

To clarify relationships between genes and metabolites involved in MGs, GGs, and flavonoids biosynthesis, correlation analysis and WGCNA were performed. Person correlation analysis was conducted between the DEGs and DEMs related to each of these biosynthetic pathways. The WGCNA package in R was utilized to identify closely related gene modules among significant DEGs (FDR < 0.05) across four tissues [74]. Initially, a similarity matrix was constructed by calculating correlations among all selected genes. Genes with low expression were (FPKM < 10) excluded. Remaining genes were used to construct the weighted co-expression network with default parameters (weight = 0.85, min module size = 30). Overlapping DEGs and co-expressed genes extracted from the co-expression network identified potentially important genes. Cytohubba 0.1 [75] was applied to identify hub genes. Correlation and hub genes networks were visualized using Cytoscape 3.9.1 (https://cytoscape.org/) [76]. Overlapping candidate genes related to MGs, GGs, and flavonoids biosynthesis, based on expression profiling, phylogenetic, and WGCNA analyses, was confirmed as novel putative genes.

Structure similarity analysis of putative CYP450 s and UGTs

To further determine the functions of the putative genes, protein structure prediction was performed and compared with known functional gene structures. The ExPasy Translate Tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/) was used to identify CDS regions of target genes and translate them into amino acid sequences. Protein tertiary structures were predicted using ESMFold [77], a transformer-based language model optimized for atomic-level structure prediction from amino acid sequences.

Predicted structures of candidate genes, including CYP 71 AN24.1, UGT91 A1.1, and UGT89B2, were compared with reference proteins of known functions (e.g., PmCYP71 AN24, PmCYP71 AN24, GmUGT79 A6, GpUGT91 A1, SrUGT89B2, SmUGT89B2) using global alignment metrics, including TM-score and root mean square deviation (RMSD) [78]. TM-score were calculated using TM-align [79], with values > 0.5 indicating significant structural homology [80], and RMSD < 4Å were considered functionally relevant. PyMOL 3.0 [81] was used for the visualization of the predicted protein structures.

Validation of RNA-Seq by qRT-PCR

To verify the reliability and accuracy of sequencing data, 12 candidate DEGs were selected, and gene expression levels were measured using qRT-PCR. Primers were designed with Primers 5.0 (Primer-E Ltd., Plymouth, UK) based on transcriptomic sequences and listed in Table 3. The Pl-actin gene was used as an internal reference for normalization. The qRT-PCR assay was performed using FastKing RT Kit (with gDNase) (Tiangen, Beijing, China) and SuperReal PreMix Plus (SYBR Green) Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Reactions for each sample were conducted in triplicat. Gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔCt method [82] and validated against sequencing results through Pearson correlation analysis.

Conclusions

Metabolomic profiling and transcriptome analysis of PL revealed specific metabolite accumulation and gene expression patterns across different tissues. This study systematically identified the DEMs and DEGs associated with MGs, GGs, and flavonoids—the primary bioactive constituents—to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of their pharmacological effects. In total, 19 DEMs and 90 DEGs associated with MGs, ten DEMs and 14 DEGs associated with GGs, and 205 DEMs and 67 DEGs associated with flavonoids were identified. Notably, roots (the medicinally relevant tissue) exhibited substantial accumulation of eight MGs, two GGs, and 18 flavonoids, corresponding with high expression levels of 16, two, and nine structure genes, respectively. Additionally, nine CYP450 s and two UGTs were identified as novel candidate genes involved in MGs biosynthesis, and 14 UGTs were identified for flavonoids through phylogenetic and expression analyses. Correlation analysis prioritized CYP71E1, CYP71 AN24.1, CYP71 AU50.2, and UGT91 A1.1 for MGs biosynthesis, along with UGT71 K1.4, UGT89B2, UGT73 C25, and UGT71 K1.2 for flavonoids biosynthesis. WGCNA revealed turquoise, green, and blue modules significantly associated with MGs and flavonoids biosynthesis, revealing 24 hub genes for MGs and 18 for flavonoids. The overlap of phylogenetic, expression level, correlation and WGCNA analyses identified CYP71 AN24.1 and UGT91 A1.1 as putative MGs biosynthetic genes, and UGT89B2 as a flavonoid-related candidate. Protein structure prediction and similarity analyses further supported their functional conservation with known terpenoid-modifying enzymes and flavonoid-specific glycosyltransferases, respectively. These findings provide a robust theoretical foundation for future metabolic engineering aimed at optimizing biosynthetic genes associated with primary active constituents in PL.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACAT

Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase

- AroF

DAHP synthase

- AroB

DAQ synthase

- AroD

DHQ dehydratase

- AroZ

DHS dehydratase

- AroE

Shikimate dehydratase

- ANR

Anthocyanidin reductase

- ANS

Anthocyanin synthase

- BA

3,4-Dihydroxy-5-(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoyloxy) benzoic acid

- BA-CoA

Benzoyl-CoA

- BAld

Benzaldehyde

- BALDH

Benzaldehyde dehydrogenase

- BAHD

Benzyl alcohol acetyltransferases

- BGL

Beta-glucosidase

- BUSCO

Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs

- C3H

Coumarate 3-hydroxylase

- C4H

Cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase

- CAD

Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase

- CCoAOMT

Caffeoyl CoA 3-O-methyltransferase

- CCR

Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase

- CDP-ME

4-(Cytidine-5’-diphospho) -2-C-methyl-D-erythritol

- CDP-MEP

2-Phospho-4-(Cytidine-5’-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol

- CHI

Chalcone isomerase

- CHS

Chalcone synthase

- CHD

Cinnamoyl-CoA hydratase/dehydrogenase

- 4 CL

4-Coumarate-CoA ligase

- COMT

Caffeate/5-hydroxyferulate 3-O-methyltransferase

- CSE

Caffeoyl shikimate esterase

- CYP450

Cytochrome P450

- DAHP

3-Deoxy-D-arabinoheptulosonic acid-7-phosphate

- DEG

Differential expressed genes

- DEM

Differential expressed metabolites

- DFR

Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase

- DHNAT1

1,4-Dihydroxy-2- naphthoyl-CoA thioesterase 1

- DHQ

3-Dehydroquinic acid

- 3-DHS

3-Dehydroshikimic acid

- DMAPP

Dimethylallyl diphosphate

- DOXP

1-Deoxy-D-xylulose -5-phosphDXS: 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase

- DXR

1-Deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase

- E4P

D-erythrose-4-phosphate

- FC

Fold change

- F3′5’H

Flavonoid 3′5’-hydroxylase

- F3H

Flavanone 3-hydroxylase

- F3’H

Flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase

- F5H

Ferulate 5-hydroxylase

- F6H13

Feruloyl CoA ortho-hydroxylase 3

- FLS

Flavonol synthase

- F26G

Furostanol glycoside 26-O-beta-glucosidase

- FNS

Flavone synthase

- FPKM

Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments

- GA-3P

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

- GA

Gallic acid

- GG

Gallaglycoside

- HMP-GG

3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,2-propanediol 2-O-(galloyl-glucoside)

- 2GG

Digalloglycosides /1-O,6-O-digalloyl-beta-D-glucose

- 3GG

Trigalloglycosides /1-O,2-O,6-O-trigalloyl-beta-D-glucose

- 4GG

Tetragalloglycosides

- 5GG

Pentagalloglycosides/1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucopyranose

- 6GG

Hexagalloglycosides

- 7GG

Heptagalloglycosides

- 8GG

Octagalloglycosides

- 9GG

Nonagalloglycosides

- 10GG

Decagalloglycosides

- 11GG

Undecagalloglysides

- 12GG

Dodecagalloslydides

- GGPPR

Geranylgeranyl diphosphate reductase

- GGPPS

Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase

- GPPS

Geranyl diphosphate synthase

- GPP

Geranyl diphosphate

- GT

Gallacyltransferase

- HID

2-Hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase

- HCT

Hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyl transferase

- HHT

Omega-hydroxypalmitate O-feruloyl transferase

- HMDB

Human Metabolome Database

- HMGS

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase

- HMGR

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase

- HMBPP

4-Hydroxy-3-methylbut-2- enyldiphosphate

- HMG-CoA

Hydroxymethyl-glutaryl-CoA

- 3H3PP-CoA

3-Hydroxy-3-phenylpropanoyl-CoA

- ICML1

Isoprenylcysteine alpha-carbonyl methylesterase 1

- ICMTB

Isoprenylcysteine O-methyltransferase B

- IDI

Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase

- IFS

Isoflavone synthase

- IOMT

Isoflavone O-methyltransferase

- IPP

Isopentenyl diphosphate

- ISPD

2-C-mehyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidyltransferase

- ISPE

4-Diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase

- ISPF

2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphoaphate synthase

- ISPG

1-Hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate synthase

- ISPH

1-Hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate reductase

- KAT

Ketoacyl-CoA thiolase

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- KOG

Eukaryotic Orthologous Groups

- LAR

Leucoanthocyanidin reductase

- MEP

2-C-Methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate

- ME-Cpp

2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2.4-cyclodiphosphate

- MGs

Monoterpene glycosides

- MVA

Mevalonate

- MVAP

Mevalonate-5-phosphate

- MVAPP

Mevalonate-5-diphosphate

- MVK

Mevalonate kinase

- MVD

Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase

- Nr

Non-redundant

- 3O3PP-CoA

3-Oxo-3-phenylpropanoyl-CoA

- OPLS-DA

Orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis

- ORFs

Open reading frames

- PAE

Pairwise aligned errors

- PL

Paeonia lactiflora Pall.

- pLDDT

Outputting per-residue confidence scores

- PMVK

Phosphomevalonate kinase

- PIN

(-)-Alpha-terpineol synthase

- PAL

Phenylalanine ammonialyase

- PEP

Phosphoenolpyruvic acid

- PER

Peroxidase

- PCA

Protocatechuic acid

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- QC

Quality control

- ROMT

Trans-resveratrol di-O-methyltransferase

- RMSD

Root mean square deviation

- SA

Shikimic acid

- SPS3

Solanesyl diphosphate synthase 3

- VIP

Variable importance in projection

- VICHY

Vicianin hydrolase

- VR

Vestitone reductase

- UGOG

Anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase

- UGT

UDP-glycosyltransferase

- WGCNA

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

Authors’ contributions

P.X. and J.P. conceived the study and were responsible for the design and methodology. W.L. and M.Y. developed the methodology and conducted the experiments. R.C. provided the software for data analysis. K.L. and J.L. performed the validation of the results. C.C. and X.J. carried out the formal analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data. J.C. performed the protein structure prediction and similarity analysis. X.W. and M.Y. were involved in the investigation and collection of data. K.L. and H.D. provided essential resources and contributed to the data curation. P.X. and J.L. prepared the original draft of the manuscript. J.P. and Y.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.L. and X.J. were responsible for the visualization of the data. J.P. supervised the project. W.L. administered the project and ensured its smooth execution. P.X. and J.P. secured the funding for the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundations [grant number LQ19H280006 and LMS25H280006]; Zhejiang Key Discipline in Traditional Chinese Medicine for Pharmaceutical Botany [grant number 2024-XK-06] and “the open competition mechanism to select the best candidates"project, from Pan’an County, Zhejiang Province [grant number PZYF202102].

Data availability