Abstract

Backgrounds

Paphiopedilum orchids, particularly the Chinese endemic Paphiopedilum armeniacum, are prized for their commercial and ornamental value, with the latter serving as a vital breeding resource owing to its distinctive yellow petals. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying yellow petal formation remain unclear.

Results

This work employed an integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic comparative analysis of P. armeniacum and two lighter-colored Paphiopedilum species (The sepals and petals are white.) to identify carotenoid-related differentially expressed genes and metabolites before and after blooming in all three species. Metabolomic analysis revealed a marked increase in six differential metabolites, including zeaxanthin, precorrin 2, and β-D-gentiobiosyl crocetin, in P. armeniacum, highlighting their critical role in yellow petal formation. Transcriptomic comparison identified 40 DEGs (including D27, GDSL-like, CYP97B3, LUT1, and PSY) linked to yellow pigmentation, most of which were consistently upregulated in P. armeniacum before and after blooming Integrative metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses demonstrated significant correlations between these genes and metabolites, suggesting their role in regulating carotenoid synthesis and accumulation in yellow petal formation. Furthermore, qRT-PCR elucidates the expression levels of candidate genes, identifying RPL13AD as the optimal reference gene across these three orchid species.

Conclusions

These works elucidate the expression patterns and regulatory roles of carotenoid-related genes in metabolic pathways during P. armeniacum blooming, providing new insights into the molecular mechanisms of carotenoid-mediated plant coloration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11648-0.

Keywords: Orchid, RNA sequencing, Biochemical pathways, Carotenoids

Background

The genus Paphiopedilum encompasses a striking group of orchids that are highly valued for their commercial and ornamental significance, with approximately 100 species primarily distributed across South and Southeast Asia [1]. However, extensive harvesting, trade, and habitat destruction have led to a rapid decline in wild populations, pushing some species toward extinction. Consequently, all Paphiopedilum species are listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), prohibiting their international trade [2]. Among these, Paphiopedilum armeniacum, which is endemic to China, is crucial for its predominantly apricot yellow flowers [3]. Similarly, Paphiopedilum emersonii, also known as the Slipper Orchid, is notable for its large, uniquely shaped white flowers with yellow lips [4], whereas Paphiopedilum delenatii features a white floral body with pink lips [5]. Compared to these two lighter-colored species, P. armeniacum exhibits a distinctive, vivid yellow hue across its lips, petals, and sepals, which is rare in the genus.

Carotenoids are a widely distributed class of natural pigments characterized by a polyene chain with conjugated double bonds that impart color because of their unique structure [6]. Previous studies on floral pigmentation have identified the carotenoids as the primary pigments responsible for yellow coloration in flowers such as Cymbidium hybrida [7], Tagetes erecta [8], Dendranthema morifolium [9], Lonicera japonica [10], and Osmanthus fragrans [11].

Although the key components of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway (CBP) in plants are well established [12–14], the transcriptional regulators controlling this pathway in flowers remain poorly understood [15, 16]. Carotenoid metabolite production is often closely associated with the expression of both the upstream and downstream genes. For instance, in Nicotiana langsdorffii × N. sanderae, the transcription factor MYB305, which is specifically expressed in flowers, can play a crucial role in floral nectary development and function [17]. In MYB305-silenced Nicotiana plants, β-carotene levels in the nectaries can be significantly reduced, resulting in a pale-yellow color rather than the deep pumpkin-orange color of the wild type [18]. Similarly, in Mimulus lewisii, the functional mutation in REDUCED CAROTENOID PIGMENTATION1 (RCP1) reduced CBP expression and carotenoid levels in nectar guides [19]. Another transcription factor, REDUCED CAROTENOID PIGMENTATION 2 (RCP2), has also been identified in Mimulus lewisii and is vital for plastid development and carotenoid biosynthesis. Overexpression of RCP2 in lighter or non-pigmented floral tissues, such as filaments and styles, enhances plastid formation and carotenoid accumulation [20].

This study investigated the molecular mechanisms of yellow pigmentation in Paphiopedilum by performing transcriptome sequencing of P. armeniacum, which exhibits entirely yellow flowers, and two lighter-colored species, P. emersonii and P. delenatii, at two blooming stages. Integrative transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses identified carotenoid-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and metabolites, leveraging annotations from seven databases. Pearson correlation analysis suggested that the DEGs could enhance yellow coloration in P. armeniacum during the initial blooming stage. Subsequently, qRT-PCR analysis was performed to validate the expression levels of candidate genes. In order to clarify the molecular basis for the distinct yellow pigmentation in P. armeniacum, this study aims to identify carotenoid-related genes and metabolites by comparing the transcriptomes and metabolomes of P. armeniacum with those of the two lighter-colored species (P. emersonii and P. delenatii) at the two developmental stages. It also aims to construct an integrated regulatory network based on transcriptomic and metabolomic data so as to reveal the key pathways and transcription factors involved in pigment accumulation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Graphical Abstract. This study compares the transcriptomes and metabolomes of P. armeniacum and two light-colored species at two developmental stages to identify carotenoid-related genes and metabolites responsible for P. armeniacum’s bright yellow pigmentation. The research will then be expanded to predict associated transcription factors and explore their correlations

Results

Analysis of metabolomic data

To examine the influence of carotenoid-related metabolites on color changes before and after blooming in the three Paphiopedilum species, a non-targeted metabolomic analysis was conducted at two blooming stages using the LC-QTOF platform. The analysis detected 16,568 peaks, leading to the identification of 3,964 metabolites.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to assess the overall metabolic differences between the samples and variation within groups. The results indicated that Principal Component 1 (PC1) and Principal Component 2 (PC2) accounted for 32.25% and 31.61% of the total variance, respectively. In the PC1-PC2 score plot, the pre-bloom (YS1) and post-bloom (YS2) samples of P. armeniacum were clearly separated from those of the other species, with closely clustered replicates, demonstrating high experimental reproducibility and reliability (Fig. 2A). Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) further elucidated the differences in metabolite accumulation among the samples. Using the filtering criteria of fold change ≥ 2 and VIP ≥ 1, the flowers of the same species formed distinct clusters, with significant metabolic differences observed between P. armeniacum and both P. emersonii and P. delenatii (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Comparative Metabolomic Analysis of Three Paphiopedilum Species Across Flowering Stages. (A) PCA of Three Paphiopedilum Species. Assessing inter-group differences among the three Paphiopedilum Species. Color codes: Red-Pink: YS1, Dark Yellow: YS2, Green: WS1, Cyan: WS2, Blue: PS1, Purple: PS2. (B) HCA Heatmap of Three Paphiopedilum Species. The clustering of the three Paphiopedilum Species reflects their similar metabolite expression patterns. The color of the samples has the same meaning as (A). (C) Volcano plots showing DAMs between P. armeniacum and P. emersonii, and between P. armeniacum and P. delenatii at respective pre- and post-bloom stages. (D) Venn diagram of yellow DAMs before blooming. Common DAMs between P. armeniacum and two light-colored Paphiopedilum species before blooming of Paphiopedilum. (E) Venn diagram of yellow DAMs after blooming. Common DAMs between Paphiopedilum and two light-colored Paphiopedilum species after blooming of Paphiopedilum. (F) Relative contents of Five DAMs in Three Paphiopedilum Species

To identify the metabolites contributing to the unique yellow coloration in P. armeniacum compared to the other two lighter-colored species, differential metabolites were analyzed between the two blooming stages using a fold change ≥ 2 and VIP ≥ 1. In the pre-bloom comparison (partially opened bud, YS1_vs_WS1), 2,285 DAMs were identified, of which 1,317 were upregulated and 968 were downregulated. Similarly, YS1_vs_PS1 revealed 1,908 DAMs, including 1,014 upregulated and 894 downregulated genes. In the post-bloom stage (partially opened bud, YS2_vs_WS2), identified 2,197 DAMs, with 1,157 upregulated and 1,040 downregulated, whereas YS2_vs_PS2 identified 2,324 DAMs, with 1,110 upregulated and 1,214 downregulated (Fig. 2C). To identify the metabolites potentially linked to the distinctive bright yellow coloration of P. armeniacum, differential metabolites were compared between P. armeniacum and the two lighter-colored species at both stages. This analysis formed two groups: the pre-bloom yellow-difference group (G1: YS1_vs_WS1, YS1_vs_PS1) and the post-bloom yellow-difference group (G2: YS2_vs_WS2, YS2_vs_PS2). Venn analysis revealed 1,237 shared differential metabolites in the pre-bloom stage and 1,467 in the post-bloom stage, with 1,954 overlapping metabolites between stages, suggesting that these were candidate metabolites involved in yellow pigmentation in P. armeniacum (Fig. 2D and E).

To further investigate the metabolites contributing to the yellow petal coloration of P. armeniacum, the differentially expressed metabolites were annotated using KEGG and GO databases (Table S1), identifying 47 carotenoid-related metabolites. Among these, we detected higher concentrations of key metabolites (relative content ≥ 105) in P. armeniacum, including zeaxanthin, precorrin 2, precorrin 6Y, β-D-gentiobiosyl crocetin, and caloxanthin (Table 1; Fig. 2F). Zeaxanthin, a carotenoid alcohol, is involved in the xanthophyll cycle and induces yellow pigmentation in several plants. Precorrin 2 and precorrin 6Y served as intermediates in the biosynthesis of vitamin B12 and siroheme [21]. β-D-gentiobiosyl crocetin was a major carotenoid in saffron, contributing to its vibrant yellow color, while caloxanthin was a key pigment in brown algae, participating in light energy capture and interconversion with zeaxanthin and nostoxanthin within the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway. These findings offer valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying yellow petal formation in P. armeniacum, emphasizing the role of carotenoid metabolism and pigment accumulation.

Table 1.

Differential metabolites with high abundance in P. armeniacum

| Name | YS1 | YS2 | WS1 | WS2 | PS1 | PS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precorrin 2 | 5.00E + 04 | 1.58E + 05 | 2.01E + 04 | 1.46E + 04 | 1.84E + 04 | 1.17E + 04 |

| Zeaxanthin | 8.66E + 05 | 1.02E + 06 | 2.56E + 05 | 3.90E + 05 | 2.66E + 05 | 3.39E + 05 |

| β-D-Gentiobiosyl crocetin | 7.15E + 04 | 1.73E + 05 | 1.94E + 04 | 1.62E + 04 | 1.05E + 04 | 4.35E + 03 |

| Caloxanthin | 2.58E + 05 | 4.17E + 05 | 4.12E + 04 | 6.59E + 04 | 2.75E + 04 | 2.79E + 04 |

| Precorrin 6Y | 4.47E + 05 | 6.53E + 05 | 1.11E + 05 | 4.80E + 04 | 4.52E + 04 | 3.60E + 04 |

| 3,4-Dihydrospheroidene | 8.39E + 04 | 1.24E + 05 | 2.69E + 04 | 1.51E + 04 | 2.37E + 04 | 3.32E + 04 |

Transcriptomic analysis results

To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying yellow coloration in P. armeniacum, transcriptome sequencing was conducted on 18 samples from three Paphiopedilum species, generating 171.37 Gb of high-quality data. Each sample yielded at least 6.04 Gb of clean data, with a Q30 base percentage exceeding 93.20%, ensuring data reliability (Table S2). A heatmap of sample correlations confirmed the effective clustering of samples with similar expression patterns, demonstrating strong reproducibility and consistency in the transcriptome data and providing a robust foundation for further analysis (Fig. S1A).

Following assembly, 99,914 unigenes were obtained, with an N50 of 2,085, indicating high assembly completeness. Among these, 31,246 unigenes exceeded 1 kb in length. (Fig. S1B and Table S3). Functional annotation of these unigenes was performed using seven databases, resulting in the annotation of 49,937 unigenes (Fig. S1C and Table S4). This provided essential foundational data for subsequent biological analyses.

Differential gene expression analysis

DEG analysis was performed using DESeq2 with a threshold of FDR < 0.05 and |log₂FC| ≥ 1, identifying DEGs between P. armeniacum and the two pale-colored Paphiopedilum species across two blooming stages. The YS1_vs_YS2 comparison revealed 4,363 DEGs, with 2,367 upregulated and 1,996 downregulated genes. In the YS1_vs_WS1 comparison, 22,101 DEGs were identified, including 10,777 upregulated and 11,324 downregulated genes. The YS1_vs_PS1 comparison yielded 25,963 DEGs, with 10,914 upregulated and 15,049 downregulated genes. For the YS2_vs_WS2, 24,235 DEGs were detected, comprising 10,861 upregulated and 14,474 downregulated genes. Finally, the YS2_vs_PS2 comparison identified 26,420 DEGs, with 12,342 upregulated and 14,077 downregulated.

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the unique bright yellow coloration of P. armeniacum, DEGs were compared with those of the two pale colored species at pre- and post-bloom stages. The pre-bloom comparisons (G1: YS1_vs_WS1, YS1_vs_PS1) identified 15,238 shared DEGs, whereas the post-bloom comparisons (G2: YS2_vs_WS2, YS2_vs_PS2) revealed 16,854 shared DEGs (Fig. 3A and B). Venn analysis of the pre- and post-bloom groups identified 11,407 common DEGs that were likely candidates contributing to the distinctive yellow pigmentation of P. armeniacum. These findings highlight the significant differences in gene expression patterns across blooming stages, suggesting that these genes play key roles in the biological processes and regulatory networks involved in the blooming process.

Fig. 3.

Transcriptomic and Functional Analysis of Carotenoid-related Genes in Three Paphiopedilum Species During Flowering Transition. (A) Venn diagram of DEGs before blooming. Common DEGs between P. armeniacum and two light-colored Paphiopedilum species before blooming of Paphiopedilum. (B) Venn diagram of yellow DEGs after blooming. Common DEGs between Paphiopedilum and two light-colored Paphiopedilum species after blooming of Paphiopedilum. (C) GO enrichment results of 150 carotenoid-related genes. (D) KEGG enrichment results of pathway genes related to 150 carotenoid genes. (E) Heatmap of Carotenoid-Related Differential Gene Metabolic Pathways in Three Orchid Species. GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate; PSY, phytoene synthase; PDS, phytoene desaturase; Z-ISO, ζ -carotene isomerase; ZDS, ζ -carotene desaturase; CrtISO, carotenoid isomerase; LCYE, lycopeneε-cyclase; LCYB, lycopene β-cyclase; BCH, β-carotene hydroxylase; CYP97A, cytochrome P450 carotene β-hydroxylase; CYP97C, cytochrome P450 carotene ε-hydroxylase; ZEP, zeaxanthin epoxidase; VDE, violaxanthin de-epoxidase; NXY, neoxanthin synthase; CCD, carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase; NCED, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase; ABA, abscisic acid

To investigate the genes potentially involved in yellow petal formation in P. armeniacum compared with the other two species, 150 carotenoid-related genes were identified through functional annotation of all transcripts. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed to elucidate the roles of these genes.

In the molecular function category, the sole enriched GO term was “catalytic activity” (Fig. 3C), highlighting the role of the selected genes in catalyzing metabolic reactions. In the cellular component category, the “cytoplasm” and “chloroplast/plastid” were enriched, which is consistent with the sites of carotenoid biosynthesis and storage in plant cells. In the biological process category, the significantly enriched GO terms included “lipid metabolic process”, “secondary metabolic process”, and “biosynthetic process”, all directly related to carotenoid synthesis and regulation. The enrichment of “metabolic process” suggests that these genes are involved in broader metabolic functions. Additionally, the terms of “response to light stimulus” and “response to abiotic stimulus” indicated potential roles in plant adaptation to environmental changes, linking carotenoids to stress defense mechanisms.

KEGG pathway analysis confirmed the importance of these genes in the “Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides” and “Carotenoid biosynthesis” pathways (Fig. 3D), indicating their central roles in plant secondary metabolism and shifts in secondary metabolite synthesis in petals across blooming stages. The enrichment of “Cytochrome P450” and “Prenyltransferases” pathways further suggested that these genes contributed to the synthesis of compounds involved in protecting plants from environmental stress.

To analyze the carotenoid pathway genes linked to yellow coloration in the three species, DEGs involved in carotenoid biosynthesis were selected from 150 pathway-related genes, yielding 40 carotenoid-related genes shared between the pre- and post-bloom yellow difference groups. To explore their roles in carotenoid regulation at different blooming stages, these 40 DEGs were mapped onto CBP metabolic and related pathways (Fig. 3E). After lycopene formation, the CBP pathway diverged into two routes, where one was catalyzed by LCYB to produce β-carotene, which was further processed by HYB, ZEP, and NSY to generate zeaxanthin, violaxanthin, and neoxanthin. These intermediates were then cleaved by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 (CCD1) family enzymes at the 5,6(5’,6’), 7,8(7’,8’), and 9,10(9’,10’) double bonds, yielding various volatile compounds [12–14].

Most DEGs in P. armeniacum were upregulated across both pre- and post-bloom stages, exhibiting significant differences between the two pale colored species. However, the differences between the two stages within P. armeniacum were less pronounced, indicating steady accumulation of carotenoid-regulating genes during blooming. Additionally, the key functional genes in the CBP pathway were consistently annotated across multiple databases, highlighting the relevant differentially expressed genes.

Several genes were linked to carotenoid degradation and synthesis of strigolactones and abscisic acid, including CCD1 and NCED, which were involved in carotenoid decomposition. Unigene_145533, Unigene_070584, and Unigene_067738, all upregulated in P. armeniacum, may regulate CCD1 and contribute to floral development or responses to environmental stress. Conversely, Unigene_122069 and Unigene_021080, which were expressed in the two pale-colored species but downregulated in P. armeniacum, could play a role in maintaining yellow pigmentation in P. armeniacum, while contributing to color loss in the other species.

Screening of transcription factors and correlation analysis of carotenoid-related functional genes

Transcription factors can be pivotal in regulating carotenoid gene expression by binding to the promoters of structural genes, thereby activating or inhibiting their expression and influencing carotenoid content and composition. Among the DEGs common to the three orchid species across the pre- and post-bloom stages, 648 transcription factors were predicted, spanning 457 gene families, including MYB, C2H2, C3H, bZIP, NAC, B3, HB, NF-Y, SET, and bHLH (Fig. S2). These families may be integral to pigment biosynthesis in orchids. MYB305, RCP1, and RCP2 were identified as transcription factors that were positively associated with carotenoid regulation in Nicotiana langsdorffii × N. sanderae, Mimulus lewisii, and Mimulus verbenaceus, respectively. The homology alignment of Paphiopedilum transcriptome sequences with these transcription factors and their Arabidopsis thaliana homologs (AT3G27810, AT5G40350, AT1G69560, AT1G26780, AT1G01320, AT4G28080, and AT1G15290) identified 18 MYB305 and 3 RCP1 genes.

To investigate the roles of these transcription factors in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway, correlation network analysis was conducted between the 21 identified transcription factors and DEGs within the pathway. The analysis revealed the significant correlations between many predicted transcription factors and specific CBP genes, such as Unigene_057660 with Unigene_035706, Unigene_149599, Unigene_053650, Unigene_001275, and Unigene_072220. These findings suggest potential regulatory relationships between transcription factors and key functional genes in CBP (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Regulatory Network and Correlation Analysis of Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Three Paphiopedilum Species. (A) Correlation Network of Transcription Factors and Differential Carotenoid Functional Genes. Blue nodes represent MYB305, and reddish-brown nodes represent RCP1. Key genes in the CBP metabolic pathway are divided into two clusters around CRTISO: orange-red and orange-yellow sections. (B) Pearson Correlation Heatmap of 6 Key Differential Metabolites and 40 Differential Genes. *: P ≤ 0.05, **: P ≤ 0.01, ***: P ≤ 0.001

Integrative metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis

Metabolomic analysis identified 47 carotenoid-related differential metabolites, while transcriptomic analysis revealed 40 DEGs closely associated with the yellow pigmentation of P. armeniacum. To identify the candidate genes involved in yellow color formation, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between these 40 DEGs from the pre- and post-bloom stages and the six metabolites with elevated concentrations in P. armeniacum. The analysis revealed significant correlations between most DEGs and the six metabolites (Fig. 4B). Notably, Unigene_149599, Unigene_068749, Unigene_139706, Unigene_064796, and Unigene_035706 were positively correlated with zeaxanthin and implicated in the zeaxanthin metabolic pathway based on KEGG annotations. Precorrin 2 displayed a significant positive correlation with Unigene_157735, Unigene_048714, Unigene_059313, and Unigene_064796.

Further analysis revealed significant correlations between caloxanthin and Unigene_064796, Unigene_140605, Unigene_139706, Unigene_076449, Unigene_045374, Unigene_068749, Unigene_157842, Unigene_067738, Unigene_145533, Unigene_079422, and Unigene_149599. Similarly, β-D-gentiobiosyl crocetin and precorrin 6Y demonstrated consistent and significant positive correlations with multiple genes, including Unigene_157735, Unigene_048714, Unigene_059313, Unigene_064796, Unigene_140605, Unigene_139706, Unigene_076449, Unigene_045374, Unigene_068749, Unigene_157842, Unigene_067738, Unigene_145533, Unigene_079422, and Unigene_149599. This pattern of shared correlation suggests potential synergistic interactions or common regulatory mechanisms between these genes and their metabolites. Additionally, 3,4-dihydrospheroidene was significantly positively correlated with Unigene_148628, Unigene_060755, Unigene_072220, Unigene_053650, Unigene_158603, Unigene_057546, Unigene_001275, and Unigene_035706.

Collectively, these findings suggest the presence of molecular regulatory networks between these metabolites and DEGs in P. armeniacum, which may influence carotenoid synthesis and accumulation, ultimately contributing to yellow pigmentation of its flowers.

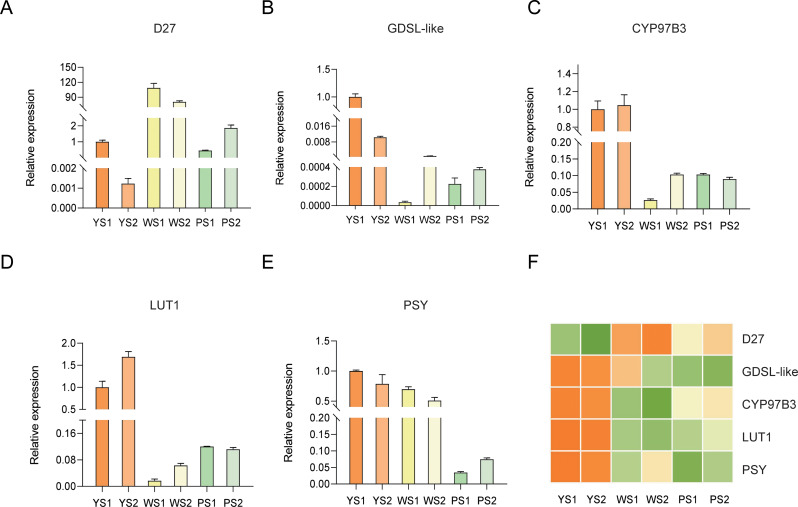

Validation of transcriptome data accuracy via qRT-PCR

From 47 differentially expressed genes, five candidate genes with significant differential expression Unigene_036751, Unigene_064796, Unigene_060755, Unigene_072220, and Unigene_079422 were randomly selected. Through multiple sequence alignment with the Arabidopsis thaliana genome, these five genes were annotated as D27, GDSL-like, CYP97B3, LUT1, and PSY, respectively. Subsequently, the expression levels of these five genes were further validated using qRT-PCR (Table S5). The results confirmed that the expression trends of these genes were consistent with the transcriptome data across the three Paphiopedilum species, validating the reliability of transcriptome analysis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

qRT-PCR Results of Five Genes in P. armeniacum, with Expression Levels Normalized to RPL13AD Expression in YS1. (A) qRT-PCR results for D27 (B) qRT-PCR results for GDAL-like (C) qRT-PCR results for CYP97B3 (D) qRT-PCR results for LUT1 (E) qRT-PCR results for PSY (F) Heatmap of gene expression levels for the five genes based on transcriptome sequencing. The progressive darkening of orange corresponds to increased degrees of gene up-regulation, while intensifying green coloration indicates stronger down-regulation, with pale yellow denoting baseline expression levels showing no statistically significant changes

Discussion

This study explored the mechanisms underlying the yellow petal coloration of P. armeniacum by comparing its transcriptome and metabolome with those of two light-colored Paphiopedilum species. Key genes and metabolites associated with bright yellow coloration in P. armeniacum were identified, offering new insights and candidate gene resources for Paphiopedilum breeding.

Key genes in the carotenoid metabolic pathway regulate the distribution of substrates for different carotenoids. Overexpression of LCYB led to β-carotenoid accumulation, while LCYE overexpression enhanced α-carotenoid production, resulting in lutein accumulation [11]. In Chrysanthemum morifolium, variations in carotenoid composition between petals and leaves are driven by the differential expression of LCYB and LCYE [22]. Similarly, in Oncidium cultivars, elevated LCYE transcript levels in leaves promoted lutein accumulation, while increased LCYB levels in floral tissues resulted in b, b-carotenoid accumulation [23]. Our metabolomic comparison revealed higher levels of zeaxanthin, precorrin 2, precorrin 6Y, β-D-gentiobiosyl crocetin, 3,4-dihydrospheroidene, and caloxanthin in P. armeniacum. The previous high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis exhibited the significant increases in violaxanthin, xanthophyll, zeaxanthin, and β-cryptoxanthin during P. armeniacum blooming, with zeaxanthin being particularly abundant [24]. Violaxanthin and zeaxanthin belong to the same metabolic branch in the carotenoid pathway. The low detection levels of α-carotene and β-carotene suggested that LCYB expression dominated the CBP pathway in P. armeniacum, with active downstream BCH expression further converting β-carotene into zeaxanthin. Additionally, other differential metabolites were identified, including precorrin 2 and precorrin 6Y, intermediates in vitamin B12 synthesis, and β-D-gentiobiosyl crocetin and caloxanthin, which directly contribute to pigment accumulation in plants. As a tetraterpenoid derivative, 3,4-dihydrospheroidene is also a type of carotenoid [25]. Besides zeaxanthin, these previously unidentified metabolites, combined with violaxanthin, xanthophyll, and β-cryptoxanthin, likely played a role in the distinctive yellow pigmentation of P. armeniacum.

Previous studies have successfully utilized combined transcriptome and metabolome analyses to identify gene networks regulating plant traits, such as the anthocyanin metabolic network in Cymbidium, in which anthocyanin biosynthesis genes and CeMYB104 expression are linked to purple sepal formation [26]. In this study, high-quality and reproducible transcriptome data were obtained from three orchid species across two blooming stages, highlighting carotenoid-related DEGs in a pathway heatmap (Fig. 3E). Notably, ZEP exhibited the highest number of differential transcripts, and its loss-of-function or silencing led to zeaxanthin accumulation [15, 27]. Metabolomic analysis revealed significantly elevated levels of violaxanthin and zeaxanthin in P. armeniacum compared to those in other species. The upregulation of genes encoding key enzymes, including BCH, ZEP, and VDE, likely contributed to the observed petal color differences. In a recent study, overexpression of the ClBCH from Cymbidium lowianum in Arabidopsis thaliana led to an increase in carotenoid concentration. Therefore, the BCH in P. armeniacum may also exhibit a similar expression pattern.

Genes involved in abscisic acid (ABA) synthesis, astaxanthin, and strigolactone metabolism, though not directly involved in carotenoid biosynthesis, may regulate the distribution or conversion of carotenoids. For instance, the stress response triggered by abscisic acid (ABA) can influence the expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes. This indirect impact on carotenoid concentration can result in flowers appearing yellow or orange [28]. Astaxanthin is responsible for the coloration of many plants, algae, and some bacteria. In plants, it plays a vital role in photosynthesis [29]. Strigolactone primarily functions in various plant development processes and is produced through the decomposition of carotenoids [30, 31]. As side branches of the CBP, the up-regulation and down-regulation of related genes may also lead to changes in flower color.

Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCD1 and CCD4) are known to influence carotenoid transformation and petal color variation [23, 32], whereas they do not directly regulate CBP transcription. The carotenoid cleavage oxygenase (CCO) family, which includes CCDs and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenases (NCEDs), catalyzes specific carotenoid oxidations to maintain carotenoid homeostasis and generate bioactive carotenoids such as plant hormones (ABA and SL), signaling molecules, and volatile/aromatic/pigment compounds [33]. In chrysanthemums, CCD4 expression is specific to white petals, and CCD4 RNAi silencing can change petal color from light to yellow [34]. Similarly, in Brassica napus, a transposon mutation in BnaCCD4, a CCD4 homolog, shifts petal color from light to yellow [32]. In our comparison of P. armeniacum with other orchids, four CCD1-related genes and two NCED-related genes were identified. Notably, Unigene_122069, Unigene_021080, and Unigene_124702 were upregulated in the two light-colored species, potentially explaining the lack of full yellow flower coloration observed in P. armeniacum.

In summary, our differential metabolite and gene expression analyses identified key carotenoid-related genes involved in yellow flower formation in P. armeniacum. In the future, sampling strategies for orchid materials could be further optimized by incorporating multiple temporal stages and tissue-specific sampling (e.g., petals, labella, sepals) coupled with spatiotemporal transcriptomics, to resolve cell type-specific regulatory networks governing carotenoid deposition. To validate candidate genes, functional studies such as Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) or heterologous expression in model plants (e.g., transgenic tobacco) could be implemented to assess their roles in pigment biosynthesis. These findings offer valuable insights for future research into the molecular mechanisms underlying yellow pigmentation in P. armeniacum.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the metabolome of three orchid species at the early and full bloom stages, confirming the presence of carotenoids contributing to the unique yellow coloration of P. armeniacum flowers. Five metabolites were identified as potential contributors to yellow pigment accumulation in P. armeniacum, with zeaxanthin being the most abundant carotenoid. Transcriptomic analysis revealed 40 carotenoid-related genes with distinct expression patterns in P. armeniacum and identified 21 potential transcription factors associated with the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway (CBP). Suitable reference genes for each Paphiopedilum species were selected and the accuracy of transcriptome sequencing was validated using qRT-PCR. These findings provide valuable molecular insights into the mechanisms underlying yellow coloration in P. armeniacum and offer a foundation for further studies on color polymorphism, species evolution, and the role of these factors in color evolution.

Materials

Plant materials and growth conditions

The three Paphiopedilum species used in this experiment, including P. armeniacum, P. delenatii, and P. emersonii, were cultivated in a controlled greenhouse Luyuan Flower Co. Ltd., Xingyi, Guizhou. The environmental conditions were set at a temperature of 24℃±1 and a relative humidity of 65%±5 RH, with a photoperiod of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness. This study focused on two key developmental stages, the early blooming stage (partially opened bud, S1) and full blooming stage (fully opened flower, S2), with specific notations for each species. For P. armeniacum, these stages were labeled YS1 and YS2 (Fig. 6A and D). P. emersonii was assigned as WS1 and WS2 (Fig. 6B and E), and P. delenatii was labeled PS1 and PS2 (Fig. 6C and F). Flowers were collected at these stages, with three individual flowers sampled for each Paphiopedilum species, serving as three independent biological replicates. The collected flowers were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C for subsequent transcriptome sequencing, metabolome sequencing, and real-time quantitative RT-qPCR analysis.

Fig. 6.

Morphology of Three Paphiopedilum Species at Various Stages. (A) P. armeniacum before blooming (YS1). (B) P. emersonii before blooming (WS1). (C) P. delenatii before blooming (PS1). (D) P. armeniacum after blooming (YS2). (E) P. emersonii after blooming (WS2). (F) P. delenatii after blooming (PS2)

Metabolite sample preparation and analysis

Sample preparation started with accurately weighing 50 mg portions. The main steps for metabolite extraction included: grinding samples in extraction solution with magnetic beads, ultrasonic treatment, centrifugation after incubation, drying the supernatant under vacuum, reconstituting the residue using the extraction solution, and then conducting the final instrumental analysis. Untargeted metabolite profiling was conducted using the LC-MS/MS platform consisting of a Waters Acquity I-Class PLUS ultra-performance liquid chromatography system coupled with a Waters Xevo G2-XS QTof high-resolution mass spectrometer (Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd.). Analyses were performed in both positive and negative ion modes using an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (Waters Corp., Milford, CT, USA) [35]. Differential metabolites (DAMs) were identified based on a variable importance in projection (VIP) score > 1, Student’s t-test (p < 0.05), and |log2FC| ≥ 0.50.

cDNA library construction, transcriptome sequencing, and screening of carotenoid-related genes

RNA was extracted using the Tiangen RNA Plant Plus kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Beijing, China), and its purity, concentration, and integrity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Finland) and Agilent 2100/LabChip GX system. Library construction involved end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and size selection of cDNA fragments, followed by PCR enrichment and quality verification using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Clustering was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using the TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS and paired-end sequencing was conducted on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. After sequencing, clean reads were generated by removing adapter sequences, poly-N, and low-quality reads, and Q20, Q30, GC content, and sequence duplication rates were calculated. Transcriptome assembly was performed using Trinity with a group-wise assembly approach, and the assembly quality was evaluated based on the N50 value (≥ 1 kb) [36].

The reads were aligned to the Unigene library using Bowtie, with the expression levels estimated by RSEM and reported as the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) [37–39]. The carotenoid-related genes were identified by annotation against seven databases: NCBI-nr, NCBI-nt, Pfam, EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG), Swiss-Prot, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Gene Ontology (GO). DEGs were identified using DEG-Seq2 with the selection criteria of |logFC| ≥ 1 and Padj ≤ 0.05. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of DEGs were conducted using TBtools to ensure reliable screening of gene sets [40]. Finally, TBtools was employed to generate pathway heat maps for the relevant identified genes.

Prediction and screening of transcription factors

The transcription factors within DEGs related to color changes before and after blooming can be predicted using the ITAK platform [41]. Currently, only three transcription factors related to carotenoid biosynthesis in flowers, NlMYB305, MlRCP1, and MvRCP2, have been reported. In this study, transcription factors involved in carotenoid metabolism were identified in three Paphiopedilum species by aligning their protein sequences with those reported in the literature and homologous sequences in Arabidopsis. Sequences with an E-value greater than 5 were classified as corresponding transcription factors. Furthermore, a correlation network between carotenoid metabolism-related DEGs and these transcription factors was constructed using Pearson correlation coefficients and visualized using Cytoscape [42].

Correlation analysis between carotenoid-related differential genes and differential metabolites

The Pearson correlation analysis was performed between DEGS and selected differential metabolites from the pre-bloom yellow comparison groups (YS1_vs_WS1, YS1_vs_PS2) and the post-bloom yellow comparison groups (YS2_vs_WS2, YS2_vs_PS2).

RT-qPCR analysis of carotenoid biosynthesis-related genes

RNA was extracted from flower tissues using a plant RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, China), and its concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer. cDNA synthesis was performed using a Bio-Rad iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Degenerate primers for each gene’s conserved region were designed using Primer Premier 6.0, and all primer sequences are detailed in Table S6. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using TB Green® Premix Ex TaqTM II (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan) on a qTOWER RT-PCR system (Analytik, Jena, Germany). The stability of seven reference genes (Actin, UBQ, GAPDH, β-TUB, RPL13AD, PIP1-2, 18sRNA) was assessed in three Paphiopedilum species using geNorm. M values were calculated, with lower values indicating greater stability. Based on V values (V/Vn + 1 < 0.15), the top reference genes were: RPL13AD and 18sRNA for P. armeniacum, β-TUB and 18sRNA for P. emersonii, and UBQ and β-TUB for P. delenatii. RPL13AD was chosen for subsequent experiments across all species.

Gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and normalized to the Ct value of the optimal reference gene in P. armeniacum at the pre-bloom stage [43].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Full-Length Transcriptome Sequencing Results.

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2. Distribution of Transcription Factor Gene Families.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure S3. geNorm Analysis Results.

Supplementary Material 4: Table S1. 47 DAMs Annotations Results.

Supplementary Material 5: Table S2 Statistical Summary of Sample Sequencing Data Evaluation.

Supplementary Material 6: Table S3. Transcriptome Assembly Statistics Table.

Supplementary Material 7: Table S4. Unigene Annotation Statistics Table for Three Paphiopedilum Species.

Supplementary Material 8: Table S5. Primer Sequences and Product Lengths of Genes Used in RT-qPCR.

Supplementary Material 9: Table S6. Primer Sequences and Product Lengths of Housekeeping Genes Used in RT-qPCR.

Acknowledgements

I extend my sincere gratitude to Professor Hu Tao for his invaluable support in my project and Chang Yanting for her guidance in writing the paper. Their assistance was instrumental to the successful completion of my work. I also thank the research team for their cooperation and support in data collection during my research project. Finally, I would like to thank MJEditor for linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- P. armeniacum

Paphiopedilum armeniacum

- P. emersonii

Paphiopedilum emersonii

- P. delenatii

Paphiopedilum delenatii

- YS1

P. armeniacum before blooming

- WS1

P. emersonii before blooming

- PS1

P. delenatii before blooming

- YS2

P. armeniacum after blooming

- WS2

P. emersonii after blooming

- PS2

P. delenatii after blooming

- CBP

Although the key components of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway

- KOG

EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GO

Gene Ontology

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DAMs

Differential metabolites

- RCP1

Reduced carotenoid pigmentation1reduced 1

- RCP2

Carotenoid pigmentation 2

- GGPP

Geranylgeranyl diphosphate

- PSY

Phytoene synthase

- PDS

Phytoene desaturase

- Z-ISO

ζ-carotene isomerase

- ZDS

ζ-carotene desaturase

- CrtISO

Carotenoid isomerase

- LCYE

Lycopeneε-cyclase

- LCYB

Lycopene β-cyclase

- BCH

β-carotene hydroxylase

- CYP97A

Cytochrome P450 carotene β-hydroxylase

- CYP97C

Cytochrome P450 carotene ε-hydroxylase

- ZEP

Zeaxanthin epoxidase

- VDE

Violaxanthin de-epoxidase

- NXY

Neoxanthin synthase

- CCD

Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase

- NCED

9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase

- ABA

Abscisic acid

Author contributions

YY, YC, YM, and ZJ conceived the research program and designed the study. YC, YM, YD, WZ, TC, PZ, and BY collected experimental materials and performed the experiments. YY and YC analyzed the data. YY, YC, and TH wrote the manuscript. ZJ and TH revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ICBR Fundamental Research Funds (grant numbers 1632023010 and 1632020001). The funders were not involved in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Data availability

The following information was supplied regarding the data availability: Transcriptome sequencing data are available in the NCBI SRA under the following accession numbers: PRJNA1134376, PRJNA1134374, PRJNA1134375, PRJNA1134378, PRJNA1134366, and PRJNA1134367.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yaqin Ye and Yanting Chang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zehui Jiang, Email: jiangzh@icbr.ac.cn.

Tao Hu, Email: hutao@icbr.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Teoh ES. Orchids of Asia. 3rd ed. Singapore: Times Editions-Marshall Cavendish; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M, Li SZ, Chen LJ, Li J, Li LQ, Rao WH, et al. Conservation and reintroduction of the rare and endangered Orchid Paphiopedilum armeniacum. Ecosyst Health Sustain. 2021;7(1):1903817. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mou ZMM, Yang N, Li SY, Hu H. Nitrogen requirements for vegetative growth, blooming, seed production, and Ramet growth of Paphiopedilum Armeniacum (Orchid). HortScience. 2012;47:585–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen XQ, Stephan W. Flora of China. Vol. 25, Orchidaceae. Beijing: Science; St. Louis: Botanical Garden Press;; 2009. pp. 36–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Averyanov L, Cribb P, Loc PK, Hiep NT. Slipper orchids of Vietnam. Compass Press Limited; 2003.

- 6.Hermanns AS, Zhou XS, Xu Q, Tadmor Y, Li L. Carotenoid pigment accumulation in horticultural plants. Hortic Plant J. 2020;6:343–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Albert NW, Zhang HB, Arathoon S, Boase MR, Ngo H, et al. Temporal and Spatial regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis provide diverse flower colour intensities and patterning in Cymbidium Orchid. Planta. 2014;240(5):983–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moehs CP, Tian L, Osteryoung KW, Dellapenna D. Analysis of carotenoid biosynthetic gene expression during marigold petal development. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;45:281–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kishimoto S, Maoka T, Nakayama M, Ohmiya A. Carotenoid composition in petals of chrysanthemum (Dendranthema grandiflorum (Ramat.) Kitamura). Phytochemistry. 2004;65(20):2781–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia Y, Chen WW, Xiang WB, Wang D, Xue BG, Liu XY, et al. Integrated metabolic profiling and transcriptome analysis of pigment accumulation in Lonicera japonica flower petals during colour-transition. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han YJ, Wang XH, Chen WC, Dong MF, Yuan WJ, Liu X, et al. Differential expression of carotenoid-related genes determines diversified carotenoid coloration in flower petal of Osmanthus fragrans. Tree Genet Genomes. 2014;10:329–38. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham FX, Gantt E. Genes and enzymes of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49(1):557–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschberg J. Carotenoid biosynthesis in blooming plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4(3):210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka Y, Sasaki N, Ohmiya A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant J. 2008;54:733–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Römer S, Lübeck J, Kauder F, Steiger S, Adomat C, Sandmann G. Genetic engineering of a zeaxanthin-rich potato by antisense inactivation and co-suppression of carotenoid epoxidation. Metab Eng. 2002;4(4):263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan H, Zhang JX, Nageswaran D, Li L. Carotenoid metabolism and regulation in horticultural crops. Hortic Res. 2015;2:15036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu GY, Ren G, Guirgis A, Thornburg RW. The MYB305 transcription factor regulates expression of nectarin genes in the ornamental tobacco floral nectary. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2672–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu GY, Thornburg RW. Knockdown of MYB305 disrupts nectary starch metabolism and floral nectar production. Plant J. 2012;70(3):377–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sagawa JM, Stanley LE, LaFountain AM, Frank HA, Liu C, Yuan YW. An R2R3-MYB transcription factor regulates carotenoid pigmentation in Mimulus lewisii flowers. New Phytol. 2016;209:1049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanley LE, Ding BQ, Sun W, Mou FJ, Hill C, Chen SL, et al. A tetratricopeptide repeat protein regulates carotenoid biosynthesis and chromoplast development in Monkeyflowers (Mimulus). BioRxiv. 2017. 10.1101/171249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren MJ, Raux E, Schubert HL, Escalante-Semerena JC. ChemInform abstract: the biosynthesis of adenosylcobalamin (vitamin B12). ChemInform. 2002;33(44):272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishimoto S, Ohmiya A. Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis in petals and leaves of chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium). Physiol Plant. 2006;128(3):436–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiou CY, Pan HA, Chuang YN, Yeh KW. Differential expression of carotenoid-related genes determines diversified carotenoid coloration in floral tissues of Oncidium cultivars. Planta. 2010;232(4):937–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai Y, Ma J, et al. Color components determination and full-length comparative transcriptomic analyses reveal the potential mechanism of carotenoid synthesis during Paphiopedilum armeniacum blooming. PeerJ. 2024;12:e16914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Roszak AW, McKendrick K, Gardiner AT, Mitchell IA, Isaacs NW, Cogdell RJ, et al. Protein regulation of carotenoid binding. Structure. 2004;12(5):765–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ai Y, Zheng QD, Wang MJ, Xiong LW, Li P, Guo LT, et al. Molecular mechanism of different flower color formation of Cymbidium ensifolium. Plant Mol Biol. 2023;113:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolters AMA, Uitdewilligen JGAML, Kloosterman BA, Hutten RCB, Visser RGF, van Eck HJ. Identification of alleles of carotenoid pathway genes important for Zeaxanthin accumulation in potato tubers. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;73(6):659–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu G, Luo L, Yao L, Wang C, Sun X, Du C. Examining carotenoid metabolism regulation and its role in flower color variation in Brassica rapa L. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(20):11164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishida Y, Berg PC, Shakersain B, Hecht K, Takikawa A, Tao R, Kakuta Y, Uragami C, Hashimoto H, Misawa N, et al. Astaxanthin: past, present, and future. Mar Drugs. 2023;21(10):514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patil S, Zafar SA, Uzair M, Zhao J, Fang J, Li X. An improved mesocotyl elongation assay for the rapid identification and characterization of Strigolactone-Related rice mutants. Agronomy. 2019;9(4):208. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia K-P, Baz L, Al-Babili S. From carotenoids to strigolactones[J]. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(9):2189–2204. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Zhang B, Liu C, Wang YQ, Yao X, Wang F, Wu JS, et al. Disruption of a CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE 4 gene converts flower colour from white to yellow in Brassica species. New Phytol. 2015;206(4):1513–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun TH, Li L. Toward the ‘golden’ era: the status in Uncovering the regulatory control of carotenoid accumulation in plants. Plant Sci. 2020;290:110331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohmiya A, Kishimoto S, Aida R, Yoshioka S, Sumitomo K. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CmCCD4a) contributes to white color formation in chrysanthemum petals. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang JL, Zhang T, Shen XT, Liu J, Zhao DL, Sun YW, et al. Serum metabolomics for early diagnosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by UHPLC-QTOF/MS. Metabolomics. 2016;12:116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng Y, Jiao C, Sun HH, Rosli HG, Pombo MA, Zhang PF, et al. iTAK: A program for genome-wide prediction and classification of plant transcription factors, transcriptional regulators, and protein kinases. Mol Plant. 2016;9:1667–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang L, Xu X, Li J, Zheng F, Li MZ, Yan JW, et al. Transcriptome analysis provides insights into the non-methylated lignin synthesis in Paphiopedilum Armeniacum seed. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Full-Length Transcriptome Sequencing Results.

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2. Distribution of Transcription Factor Gene Families.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure S3. geNorm Analysis Results.

Supplementary Material 4: Table S1. 47 DAMs Annotations Results.

Supplementary Material 5: Table S2 Statistical Summary of Sample Sequencing Data Evaluation.

Supplementary Material 6: Table S3. Transcriptome Assembly Statistics Table.

Supplementary Material 7: Table S4. Unigene Annotation Statistics Table for Three Paphiopedilum Species.

Supplementary Material 8: Table S5. Primer Sequences and Product Lengths of Genes Used in RT-qPCR.

Supplementary Material 9: Table S6. Primer Sequences and Product Lengths of Housekeeping Genes Used in RT-qPCR.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding the data availability: Transcriptome sequencing data are available in the NCBI SRA under the following accession numbers: PRJNA1134376, PRJNA1134374, PRJNA1134375, PRJNA1134378, PRJNA1134366, and PRJNA1134367.