Abstract

Background

During dental procedures, an individual may experience anxiety, which is referred to as dental anxiety (DA). This fear presents a dilemma for both dentists and patients because it causes people to avoid or even deny dental care, thereby affecting their oral health and quality of life.

Objectives

This study aimed to (1) identify factors related to DA and (2) construct a model from various factors, including oral health habits and social support, among students in Indonesia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was used in the form of a self-report questionnaire administered online to 554 students selected using convenience sampling. The questionnaire consisted of Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) items and questions about demographic information (field of study, year of intake / batch, etc.), oral health behaviors (frequency of toothbrushing, dental visit, etc.), social (parents, friends, others) and spiritual support (calm down and pray). The data were analyzed with chi-square tests, logistic regression and structural equation modelling using various statistical software programs, such as IBM SPSS and WarpPLS.

Results

The final sample considered of 554 students, 155 (28%) of whom had a high DA score. Of the students, 286 (51.6%) were attending the School of Health Science cluster, and the largest single group (37%) belonged to the 2020 year of intake (batch). The fields of study, frequency of toothbrushing, reason for the last dental visit, oral health problem experience, self-ratings of oral health (SROH), and support from friends and spiritual support were significantly associated with DA. These results were supported by the odds ratios of the various variables, which ranged from 0.85 to 2.79. The coefficient of determination of the proposed model’s (R2) value was 0.15.

Conclusions

Dental anxiety among students in Indonesia was significantly associated with the demographic (fields of study), behaviors (frequency of toothbrushing, reason for the last dental visit, past dental experience, SROH), social support (from friends) and spiritual support. Although the proposed SEM model accounted for 15% of the variance in DA, further studies are needed to explore other potential contributing factors to better understand and address dental anxiety in this population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-06287-6.

Keywords: Dental anxiety, Health and non-health students, Oral health behavior, Spiritual support, Human development index, Structural equation modeling

Introduction

Dental anxiety (DA) is a global health issue that impairs individuals’ dental health and quality of life [1]. An epidemiological study found that 10–20% of persons experience high levels of DA [2]. Considering its high incidence, DA is a serious health concern, particularly given its significant influence on oral health [3]. DA is a type of emotion and tension in the form of fear that arises in response to dental care from the prospect of visiting a dentist [4, 5] or in a more extreme form, dental phobia, is a barrier to receiving dental care [6]. Health students can help improve the oral health of the community by applying their knowledge [7] especially DA manegement since a recent study found that people with low literacy scores had higher DA scores than those with high literacy scores [8]. This is a challenge that must be overcome to reduce treatment barriers, as significant DA leads to poor oral health and, in certain cases, poor quality of life [5, 8, 9].

Several studies on DA and related factors in various countries have been published [1–4, 6–8]. In Indonesia, these include several articles on DA and related issues covering specific and limited demographics [7, 10, 11].For instance, a study by Amelia et al. (2020) found significant differences in DA levels between health and non-health students, with health students having lower levels of DA than their counterparts [10]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have offered structural equation modeling (SEM) to explain the relationship between DA and related factors in Indonesia. Therefore, the purpose of this study is (1) to identify the factors that are related to DA and (2) to construct a model from various related factors, including demographics, oral health behaviors, social, and spiritual support, among students in Indonesia.

Materials and methods

Study design and sample

This cross-sectional study was conducted from October to December 2023 among Universitas Indonesia (UI) undergraduate students (N = 38,689) using convenience sampling. This study was approved by the Faculty of Dentistry Universitas Indonesia Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 81/Ethical Approval/FKGUI/XI/2023), and each participant provided electronic informed consent (via Google Forms). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki [12]. The sample size was estimated using the online Raosoft calculator (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html), as has been done in previous studies [13–15]. Following prior studies, the power of the test was set at 95%, with a 5% error margin and a response distribution of 30% (assuming the proportion of students with DA in a previous study) [16]. This resulted in a minimum sample size of 381 students. Hence, 554 students were enrolled to account for participant dropout.

Data collection

The participants were reached through a network of student bodies. A total of 554 students from all faculties at UI (categorized as health students and non-health students) volunteered to participate. The students were divided into two groups: health students (286 from five faculties) and non-health students (268 from 10 faculties). The modified questionnaire was distributed online. At the beginning of the questionnaire, there was also information about the background and objectives of the study, a data confidentiality statement, and a statement of willingness.

Research instruments

DA was assessed using the Indonesian version of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) [17]. This instrument was selected because the questionnaire is easy to answer, has been proven valid (r > 0.6 and r > 0.7, respectively) and reliable (cronbach’s alpha > 0.6 and > 0.8, respectively) [17, 18], and is widely translated into other languages and because the question items presented are short and comprehensive [6, 19, 20]. These items include visiting the dentist for treatment tomorrow, sitting in the waiting room to wait for treatment, tooth drilling, dental scaling and polishing, and local anesthetic injection to the gums [21]. The next questionnaire, addressing oral health behaviors, was taken from the Oral Health Questionnaire Survey in Adults developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2013 [22], which includes the last visit to the dentist, the reason for the last appointment, the respondent’s perception of his or her oral health state, pain/discomfort in the teeth and mouth, frequency of tooth brushing, and self-rated oral health (SROH) [23]. Unlike the dental anxiety and behavioral variables, which were based on pre-existing questionnaires, the authors developed the questionnaires for demographic data, social support, and spiritual support. The two questionnaires were subsequently merged with demographic factors such as the respondents’ identities, including their name/initials, field of study (health and non-health), gender, year of intake (batch), and region of origin along with social and spiritual support.

Hence, this study questionnaire can be regarded as a developed or modified one due to the incorporation and supplementation process involved. Further tests has been conducted to assess the validity (construct) and reliability (internal consistency / cronbach’s alpha) of this questionnaire. The English questionnaire is attached as a supplementary file.

Variables

The outcome variable was DA. The questionnaire used was the MDAS. The MDAS questionnaire is filled in independently by respondents and uses a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 = not anxious and 5 = extremely anxious) to determine the level of DA. The total score is between 5 and 25 and is then categorized into low anxiety (5–14) and high anxiety (≥ 15).

The independent variables comprised four components: demographic factors, oral health behavior, social support, and spiritual support. The demographic factors included gender, year of intake (batch), and place of origin. The questions regarding oral health behavior were developed from several items from the Oral Health Questionnaire Survey in Adults (WHO 2013), such as the time and reason for the last dental appointment. In addition, questions about oral pain or discomfort, SROH (good, fair, and poor), and frequency of toothbrushing were asked.

Social support was composed of two components: social interaction and surrounding support. As regards social interaction, the respondents were given one statement about social media (how many social media accounts do you have? ). As concerns surrounding support, the respondents were given three “Yes/No” items: one statement about parental support (“My parents accompanied me to visit the dentist”), one about support from friends (“My friends accompanied me to visit the dentist”), and one about support from another family member (“another family member accompanied me to visit the dentist”). Each statement was categorized in one of two ways, namely, a score of 0 as “NO” and a score of 1 as “YES.” The scores from the three statements were then added up (minimum score 0 and maximum 3). The total results were grouped into two categories: no support (total score 0) and have support (total score 1–3).

The presence of spiritual support from oral health professionals was obtained through two questions: the presence/absence of advice from the dentist enabling the patient to calm down before the treatment and the presence/absence of advice from the dentist about praying/worshipping before treatment. Each statement was categorized in one of two ways, namely, a score of 0 as “NO” and a score of 1 as “YES.” The scores from the two statements were then added up (minimum score 0 and maximum 2). The total results were grouped into two categories: no support (total score 0) and have support (total score 1–2).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 24.0 (IBM Chicago-IL, USA). The statistical significance level was 5% (p < 0.05). The chi-square test (for categorical variables) was performed to evaluate the association between DA and the other factors. Odds ratios (ORs) for DA were determined for numerous variables using binary logistic regression. A model was also proposed with the partial least squares-statistical equation model (PLS-SEM) [24] using WarpPLS 8.0 [25]. The model fit was evaluated using classic and additional indices. For the classic indices were used the average path coefficient (APC), Average R-squared (ARS), Average adjusted R-squared (AARS), Average block VIF (AVIF), Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF), and Tenenhaus Goodness of Fit (GoF). For the additional indices were used Simpson’s paradox ratio (SPR), R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR), Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) and Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR).

Results

The validity of the questionnaire was evaluated through the responses of 30 students who were not involved in this study. All the items in the questionnaire were deemed to be valid. Each item had a correlation coefficient greater than 0.361. Cronbach’s alpha was deemed reliable when it surpassed the threshold of 0.60 (0.890).

As shown in Table 1, the final participant sample consisted of 554 students from a university in Indonesia. Among them, 146 (26.4%) were male, and 408 (73.6%) were female; 155 (28%) had a high DA score, 286 (51.6%) were from the School of Health Science cluster, and the largest single group came from batch 2020 (37%). The fields of study, frequency of toothbrushing, reason for the last dental visit, oral health problem experience, SROH, and support from friends and spiritual support were significantly associated with DA levels. Gender, batch, place of origin, number of social media accounts, and the time of the last dental visit as well as support from parents and relatives had insignificant associations with DA levels.

Table 1.

Association between several factors and dental anxiety among students in Indonesia

| Variable | Dental Anxiety | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Low DA (n = 399) n (%) |

High DA (n = 155) n (%) |

p-value* | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 146 | 100 (68.5) | 46 (31.5) | 0.268 |

| Female | 408 | 299 (73.3) | 109 (26.7) | |

| Field of Study | ||||

| Health | 286 | 224 (78.3) | 62 (21.7) | 0.001 |

| Non-Health | 268 | 175 (65.3) | 93 (34.7) | |

| Batch | ||||

| 2020 | 205 | 148 (72.2) | 57 (27.8) | 0.289 |

| 2021 | 116 | 83 (71.6) | 33 (28.4) | |

| 2022 | 146 | 107 (73.3) | 39 (26.7) | |

| 2023 | 87 | 61 (70.1) | 26 (29.9) | |

| Place of Origin | ||||

| The Western Region of Indonesia | 530 | 383 (72.3) | 147 (27.7) | 0.550 |

| The Eastern Region of Indonesia | 24 | 16 (66.7) | 8 (33.3) | |

| Number of Social Media Accounts | ||||

| More than 5 | 116 | 88 (75.9) | 28 (24.1) | 0.300 |

| 5 or Less | 438 | 311 (71.0) | 127 (29.0) | |

| Frequency of Toothbrushing | ||||

| Twice or more per day | 437 | 328 (75.1) | 109 (24.9) | 0.004 |

| Once per day | 90 | 57 (63.3) | 33 (36.7) | |

| Lower Frequency | 27 | 14 (51.9) | 13 (48.1) | |

| Experience of any oral pain or discomfort within the last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 258 | 160 (62.0) | 37 (14.3) | < 0.001 |

| No | 296 | 239 (80.7) | 19 (6.4) | |

| Self-Rated Oral Health (SROH) | ||||

| Good | 330 | 253 (76.7) | 77 (23.3) | 0.007 |

| Fair | 175 | 117 (66.9) | 58 (33.1) | |

| Poor | 49 | 29 (59.2) | 20 (40.8) | |

| Experience of a Dental Visit (Last) | ||||

| < / = 6 months ago | 171 | 134 (78.4) | 37 (21.6) | 0.063 |

| > 6–12 months ago | 107 | 75 (70.1) | 32 (29.9) | |

| > 1–2 years ago | 73 | 56 (76.7) | 17 (23.3) | |

| > 2–5 years ago | 62 | 40 (64.5) | 22 (35.5) | |

| > 5 years ago | 84 | 60 (71.4) | 24 (28.6) | |

| Never Going to Dentist (No Experience) | 57 | 34 (59.6) | 23 (40.4) | |

| Reason for Last Dental Visit | ||||

| Consultation | 36 | 26 (72.2) | 10 (27.8) | < 0.001 |

| Routine Checks | 95 | 77 (81.1) | 18 (18.9) | |

| (Continuing) Dental Treatment | 178 | 144 (80.9) | 34 (19.1) | |

| Pain/ Dental (Tooth, Gum, Other) Problem | 163 | 99 (60.7) | 64 (39.3) | |

| Don’t Remember | 25 | 19 (76.0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Never Going to Dentist (No Experience) | 57 | 34 (59.6) | 23 (40.4) | |

| Social Support for Dental Visit (n = 497) | ||||

| Support from Friends | ||||

| No | 435 | 327(75.2) | 108 (24.8) | 0.021 |

| Yes | 62 | 38 (61.3) | 24 (38.7) | |

| Support from Parents | ||||

| No | 191 | 148 (77.5) | 43 (22.5) | 0.107 |

| Yes | 306 | 217 (70.9) | 89 (29.1) | |

| Support from Other Relatives | ||||

| No | 449 | 335 (74.6) | 114 (25.4) | 0.071 |

| Yes | 48 | 30 (62.5) | 18 (37.5) | |

| Spiritual Support from OHP | ||||

| Dentist asked to Calm Down | ||||

| No | 195 | 160 (82.1) | 35 (17.9) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 302 | 205 (67.9) | 97 (32.1) | |

| Dentist asked to Pray | ||||

| No | 392 | 303 (77.3) | 89 (22.7) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 105 | 62 (59.0) | 43 (41.0) | |

These results were supported by the ORs of the variables, which ranged from 0.85 to 2.79, as shown in Table 2. In terms of probability, the female students were almost 1.3 times more likely to experience DA than the male students. Meanwhile, the non-health students had an almost two-fold greater probability of experiencing DA than the health students, while the more senior students were likely to have a lower probability of experiencing DA than those in batch 2023. Furthermore, the students from the eastern part of Indonesia were 1.3 times more likely than their counterparts to experience DA. In terms of social media accounts, students who had five or fewer accounts were almost 1.3 times more likely than students who had more than five accounts to experience DA. The students with a lower frequency of toothbrushing had a 2.79-fold higher probability of DA, whereas those who brushed their teeth once a day had an almost 1.74-fold higher probability of DA than those who did so twice or more per day. The students who had experience of any oral pain or discomfort within the last 12 months had a 2.56-fold higher probability of DA. Meanwhile, students who reported poor oral health had a 2.27-fold higher probability of DA, those without experience of visiting the dentist had an almost 2.5-fold higher probability of DA, and those for whom dental problems were the reason for the last dental visit had a 1.68-fold higher probability of DA. In terms of social support, the students who were not accompanied by a friend, parent, or other relative had 1.62-fold, 1.08-fold, and 1.39-fold higher probabilities of DA, respectively. The students who did not receive spiritual support from oral health professional (asked to calm down and or to pray) had a 1.79-fold and 1.90-fold higher probability of DA, respectively.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of several factors with DA among students in Indonesia

| Variable | Dental Anxiety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Low DA (n = 399) n (%) |

High DA (n = 56) n (%) |

OR | 95% CI (lower-upper) |

|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 146 | 100 (68.5) | 46 (31.5) | 1 | |

| Female | 408 | 299 (73.3) | 109 (26.7) | 1.262 | 0.835–1.906 |

| Field of Study | |||||

| Health | 286 | 224 (78.3) | 62 (21.7) | 1 | |

| Non-Health | 268 | 175 (65.3) | 93 (34.7) | 1.920 | 1.317-2.800 |

| Batch | |||||

| 2020 | 205 | 148 (72.2) | 57 (27.8) | 0.904 | 0.521–1.568 |

| 2021 | 116 | 83 (71.6) | 33 (28.4) | 0.933 | 0.506–1.719 |

| 2022 | 146 | 107 (73.3) | 39 (26.7) | 0.855 | 0.475–1.539 |

| 2023 | 87 | 61 (70.1) | 26 (29.9) | 1 | |

| Place of Origin | |||||

| The Western Region of Indonesia | 530 | 383 (72.3) | 147 (27.7) | 1 | |

| The Eastern Region of Indonesia | 24 | 16 (66.7) | 8 (33.3) | 1.303 | 0.546–3.109 |

| Number of Social Media Accounts | |||||

| More than 5 | 116 | 88 (75.9) | 28 (24.1) | 1 | |

| 5 or Less | 438 | 311 (71.0) | 127 (29.0) | 1.283 | 0.800-2.059 |

| Frequency of Toothbrushing | |||||

| Twice or more per day | 437 | 328 (75.1) | 109 (24.9) | 1 | |

| Once per day | 90 | 57 (63.3) | 33 (36.7) | 1.742 | 1.078–2.816 |

| Lower Frequency | 27 | 14 (51.9) | 13 (48.1) | 2.794 | 1.274–6.129 |

| Experience of any oral pain or discomfort within the last 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 258 | 160 (62.0) | 37 (14.3) | 2.568 | 1.751–3.767 |

| No | 296 | 239 (80.7) | 19 (6.4) | 1 | |

| Self-Rated Oral Health (SROH) | |||||

| Good | 330 | 253 (76.7) | 77 (23.3) | 1 | |

| Fair | 175 | 117 (66.9) | 58 (33.1) | 1.629 | 1.086–2.442 |

| Poor | 49 | 29 (59.2) | 20 (40.8) | 2.266 | 1.214–4.230 |

| Experience of a Dental Visit (Last) | |||||

| < / = 6 months ago | 171 | 134 (78.4) | 37 (21.6) | 1 | |

| > 6–12 months ago | 107 | 75 (70.1) | 32 (29.9) | 1.099 | 0.572–2.113 |

| > 1–2 years ago | 73 | 56 (76.7) | 17 (23.3) | 1.992 | 1.056–3.758 |

| > 2–5 years ago | 62 | 40 (64.5) | 22 (35.5) | 1.449 | 0.797–2.632 |

| > 5 years ago | 84 | 60 (71.4) | 24 (28.6) | 1.545 | 0.891–2.681 |

| Never Going to Dentist (No Experience) | 57 | 34 (59.6) | 23 (40.4) | 2.450 | 1.289–4.657 |

| Reason for Last Dental Visit | |||||

| Consultation | 36 | 26 (72.2) | 10 (27.8) | 1 | |

| Routine Checks | 95 | 77 (81.1) | 18 (18.9) | 0.608 | 0.249–1.483 |

| (Continuing) Dental Treatment | 178 | 144 (80.9) | 34 (19.1) | 0.614 | 0.271–1.393 |

| Have Dental Problem (Toothache, Gum or other oral pain) | 163 | 99 (60.7) | 64 (39.3) | 1.681 | 0.760–3.719 |

| Don’t Remember | 25 | 19 (76.0) | 6 (24.0) | 0.821 | 0.254–2.652 |

| Never Going to Dentist (No Experience) | 57 | 34 (59.6) | 23 (40.4) | 1.759 | 0.714–4.331 |

| Social Support for Dental Visit (n = 497) | |||||

| Support from Friends | |||||

| No | 435 | 327(75.2) | 108 (24.8) | 1.618 | 0.700-3.736 |

| Yes | 62 | 38 (61.3) | 24 (38.7) | 1 | |

| Support from Parents | |||||

| No | 191 | 148 (77.5) | 43 (22.5) | 1.076 | 0.412–2.814 |

| Yes | 306 | 217 (70.9) | 89 (29.1) | 1 | |

| Support from Other Relatives | |||||

| No | 449 | 335 (74.6) | 114 (25.4) | 1.378 | 0.719–2.641 |

| Yes | 48 | 30 (62.5) | 18 (37.5) | 1 | |

| Spiritual Support from OHP | |||||

| Dentist asked to Calm down | |||||

| No | 195 | 160 (82.1) | 35 (17.9) | 1.779 | 1.116–2.836 |

| Yes | 302 | 205 (67.9) | 97 (32.1) | 1 | |

| Dentist asked to Pray | |||||

| No | 392 | 303 (77.3) | 89 (22.7) | 1.899 | 1.170–3.082 |

| Yes | 105 | 62 (59.0) | 43 (41.0) | 1 | |

*bold denotes significancy < 0.05

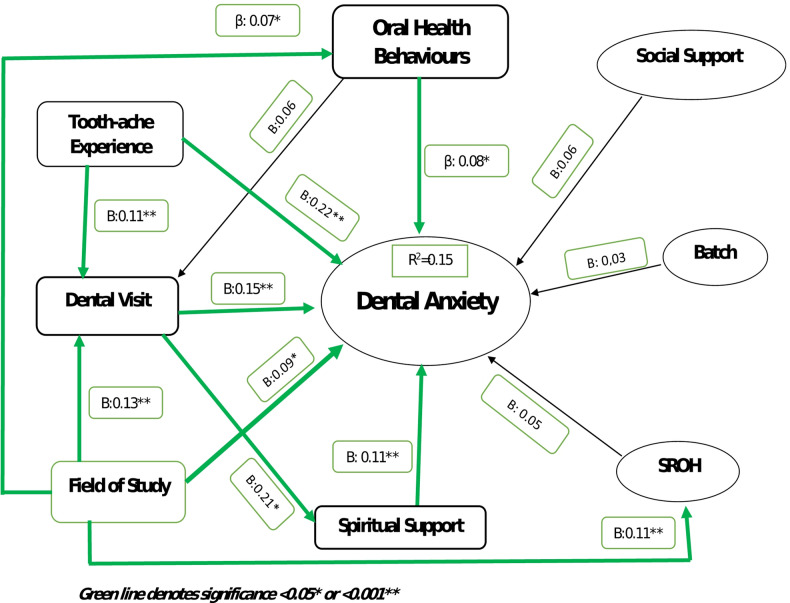

The path model was tested using variables of interest, such as demographics, behavioral, social and spiritual support, and DA among students. PLS-SEM was used, and Fig. 1 depicts the path model of the variables related to DA among students. The path model fit was examined using both the classic and additional indices. APC was 0.104 (p = 0.003), ARS was 0.045 (p = 0.072), AARS was 0.040 (p = 0.087), AVIF was 1.109, and AFVIF was 1.108 (values ≤ 3.3 are considered ideal), and GoF was 0.201 (small). The SPR for the new indices was 0.867 (acceptable if greater than 0.7; ideally equal to 1). The RSCR was 0.950 (acceptable if greater than or equal to 0.9; ideally equal to 1). The SSR was 1 (acceptable if greater than or equal to 0.7), whereas the NLBCDR was 0.900. Each index met the stated criteria for good or acceptable fit [25]. The coefficient of determination from the proposed model’s (R2) value was 0.15 (15%).

Fig. 1.

Path diagram factors related to the dental anxiety among university students in Indonesia

Figure 1 shows that for the direct effect of OHB, toothache experience (TAE), dental visit (DV), field of study (FoS), and spiritual support were significant; in other words, the direct effect of these factors affected DA with β = 0.08, β = 0.22, β = 0.15, β = 0.09, and β = 0.11, respectively. Meanwhile, social support, batch, SROH, and social interaction played an insignificant role in DA with β = 0.06, β = 0.03, β = 0.05 and β = 0.06, respectively.

The indirect effect between FoS and DA, which was mediated by OHB, DV, and SROH, showed significancy with β = 0.07, β = 0.13, and β = 0.11 respectively. Meanwhile, the indirect effect between DV and DA, which was mediated by spiritual support, was also significant with β = 0.21. Moreover, the indirect significant effect between TAE and DA, which was mediated by DV, was revealed with β = 0.11. The indirect insignificant effect between OHB and DA, which was mediated by DV, was showed with β = 0.06.

Discussion

In terms of demographic factors, females and batch-2020 students dominated. However, these factors did not show significant associations with DA. A study by Jasser et al. (2019) corroborated the finding that gender bears no correlation with DA [26]. Similarly, Alansaari et al. (2023) reported that gender had an insignificant association with DA among adult patients visiting dental clinics in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) [27]. In contrast, a study conducted by Qi et al. in 2021 found significant differences between gender [28]. The diverse outcomes might indicate that DA can affect individuals regardless of their gender. A previous study that focused in DA and gender, revealed that female had more probability of DA and also suggested that gender was still a predictor for DA [29]. So, gender is not only a demographic identity but more than that, gender remains a factor that may need to be included in future research on dental anxiety. In addition, it is essential to allocate an equal focus related to DA to both males and females.

A significant association was revealed between the FoS and DA. A larger proportion of non-health students than health students experienced high DA. This finding is consistent with previous research in Indonesia [10], Romania [30], and Yemen [31], which revealed that non-health students had higher DA. This finding supports the hypothesis that one of the determining variables for DA is the field of study, namely, knowledge and information, as well as interest in a topic that is typically found in a field of study.

The year of intake (batch) had an insignificant association with DA. This finding was in line with a previous study in Brunei [28]. This similarity might be attributed to the similarity of geographic and ethnic characteristics, as Brunei is also a Southeast Asian country. In contrast, this finding differed from similar previous studies in Israel [32] and India [9], which reported significant differences according to year of intake. This difference could be explained by the difference in the geographical and other characteristics of the study participants. The year of intake (batch) might represent the duration of students’ exposure to the atmosphere and system of andragogy education including interaction with dental students. However, the duration as a student did not guarantee access to correct information related to dental anxiety (especially if not accompanied by interaction) even though information is one of the factors related to dental anxiety [33]. The scarcity of findings on how batch relates to DA among students might indicate that this variable should be elaborated in the future.

The Central Bureau of Statistics categorizes Indonesia into two regions: the Western Region of Indonesia (WRI) and Eastern Region of Indonesia (ERI). The average value of the Human Development Index (HDI) 2017–2022 for the WRI is 72.45, while for the ERI it is 68.26. This suggests that the ERI’s human resources (HR) are still far behind those of the WRI and that there is still a gap in human development in Indonesia. The HDI is a concept that describes the state of each population based on the outcomes of human development achievements, taking into account three key factors: health, education, and income [34]. This study’s findings at least support the notion that a person’s place of origin encompasses not only geographical location, but also a wide range of other factors, such as their health. The higher likelihood of DA in the ERI aligns with the region’s lower HDI rating. This discovery may explain the initial correlation established between DA and HDI, as represented by the place of origin variable. The HDI variable could be considered by researchers examining DA in future studies.

The number of social media accounts showed no significant relationship with DA although those respondents with fewer accounts had a higher probability of DA. A previous study among undergraduate students in the United States also showed that social support on social media was not significantly related to depression, anxiety, or social isolation [35]. A study in Türkiye showed that communication through social media was significantly related to DA [36]. Despite the varying findings on the relationship between social media and DA, it is undeniable that social media could be regarded as a “double-edged sword.” Several studies have shown that social media provide positive support for the mental health of their users, but many other studies reveal that social media have the opposite impact [37]. The number of social media accounts was not just a meaningless number. It provided meaningful implicit information for us to pay attention to, especially regarding virtual interactions that might reduce or increase DA. Therefore, it is necessary to continue education about responsible social media use, which should strengthen mental well-being.

Interestingly, frequency of toothbrushing was significantly related to DA. In addition to the relationship, the lower frequency group had a higher probability of DA up to 2–3 times than the group that brushed their teeth twice a day or more. This finding aligns with several previous studies from various countries, demonstrating that individuals with high dental care anxiety are closely linked to poor oral hygiene habits and have a heightened susceptibility to oral diseases. Two similar studies in Germany among general adults population [38] and university students [39] revealed the same findings. A study in Russia also showed that dental visits and the frequency of toothbrushing among dental students were associated with DA [40]. Thus, this finding further strengthens the relationship between toothbrushing frequency and DA. A behavior that is directly related to oral hygiene is not only important for oral health but also closely related to mental well-being. A question regarding toothbrushing frequency may even be able to predict a person’s level of DA. Further research at the clinic or community level on this hypothesis may need to be considered in the future.

Previous experience of any oral pain or discomfort significantly increases the probability of DA. This finding is clearly in line with a number of studies stating that previous oral pain or discomfort is closely related to DA. A study among women in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) revealed that the participants who had pain or discomfort showed significantly higher DA than those without pain or discomfort [41]. The previous TAE also had a significant association with DA, as revealed by a study among children in Sweden [42]. The similarity of findings across these three studies strengthens the indication that the experience of oral pain and discomfort contributes to DA. Therefore, elaborating questions related to the experience of oral pain and discomfort may be relevant in both clinical and population survey settings.

SROH had a significant association with DA. The likelihood of DA rose as SROH declined. This finding is consistent with a previous study in the Swedish population, which found a significant relationship between poor SROH and DA levels [43]. This finding is particularly relevant in the field of psychology, given that, consciously or unconsciously, this finding is particularly relevant in the field of psychology given that, consciously or unconsciously, poor SROH reflect a person’s DA.

There was no significant association between DA and the time of the last dental visit. However, the longer the time since the last DV, the higher the likelihood of DA. Research on adult patients in the UAE had similar results [27]. A study of pregnant women in KSA found that the time since the most recent visit was substantially associated with DA levels [41]. Gender differences and pregnancy circumstances might be contributing causes to these disparities. The time of the last dental visit might also show participants’ hesitation to see the dentist. This hesitation might be linked to DA, however the relationship was statistically insignificant as found in this study. Furthermore, the time of the last dental visit might be presumed to be related to the degree of oral disease, with the longer the interval, the less severe the condition. Despite these discrepancies in findings, the time of the last dental visit remains an important factor to consider when studying DA.

The reason for the last dental visit showed a non-significant association with DA. Nevertheless, students who visited the dentist because they had dental problems had an almost 1.7-fold higher probability of DA than the “consultation” group. This is comprehensible given that when individuals have dental health issues, they tend to accept certain treatment techniques despite the fact that some treatments, such as extractions, surgery, and anesthetic injections, cause DA [44].

Social support, especially from friends, showed a significant association with DA, while familial support showed an insignificant relationship. However, groups that do not receive social support from their surroundings are more likely to experience DA than others. This finding is consistent with earlier research suggesting that perceived familial support is essential. Adolescents who perceive more familial support are less likely to suffer DA. Family functionality, including roles and affective involvement, influences DA levels [45].

Spiritual support given by dentists during office visits demonstrated a substantial correlation with DA. The provision of spiritual support by dentists may represent a relatively new aspect in the context of DA. Research has established a connection between spiritual support and reduced levels of overall anxiety. A comprehensive analysis of 74 previous studies found that interventions incorporating religious and spiritual practices were generally effective in addressing depression and anxiety in young individuals [46]. The application of a biopsychosocial-spiritual model in the field of dentistry should be further promoted. Vermette and Doolittle suggested strategies for a biopsychosocial-spiritual model of medical education [47], which can be applied to other health professions. This finding might be among the supporting evidence that the application of this model will improve mental well-being.

The overall findings of this study should be viewed in light of its limitations. First, the cross-sectional study design cannot confirm the direction of causal links. However, with PLS-SEM, the arrows are always single-headed, indicating directional correlations. Single-headed arrows are considered predictive relationships, but they can also be viewed as causal relationships with strong theoretical bases [24]. The study’s generalizability is limited due to the use of the convenience sampling technique and because all the participants are from the same institution. However, this study could still serve as a reference since the university has a diverse student body, encompassing various religions, ethnicities, places of origin, socioeconomic statuses, and other factors, and the proposed model might remain relevant to the circumstances of Indonesian students. Third, one disadvantage of collecting data online is the difficulty of determining whether participants completed the questionnaire independently. An additional issue is determining whether a person completed the questionnaire once or several times. To address these issues, Google Forms requires a full name and email address. Notwithstanding its shortcomings, this study could be regarded as a pioneering examination of DA among students in Indonesia that takes into account HDI and social and spiritual support. It presents the first proposed SEM model, encompassing multiple factors simultaneously, that could be applicable to other universities and countries.

Conclusion

DA among students in Indonesia was related to several factors. The fields of study, frequency of toothbrushing, reason for the last dental visit, oral health problem experience, SROH, and support from friends and spiritual support were significantly associated with DA. The other variables, namely, gender, year of intake (batch), place of origin/HDI, number of social media accounts, time of last dental visit, and support from parents and relatives, had insignificant associations with DA. A SEM model was developed to account for 15% of the relationships between the variables and the DA experienced by students in Indonesia. Future research is anticipated to investigate additional factors including academic stress levels, parents’ socioeconomic status, and so on, which may influence DA in Indonesian students, thereby refining and broadening the proposed model.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study and publication were funded by the Directorate of Research and Development, Universitas Indonesia under Hibah PUTI Q1 2024 (Grant no NKB-329/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2024).The authors express their gratitude and appreciation to all participants and all parties who have contributed directly or indirectly to this study. The authors also express their admiration for the people’s tenacity in the fight for freedom and humanity in Palestine and around the world.

Abbreviations

- DA

Dental Anxiety

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Science

- SEM

Structural equation modeling

- MDAS

Modified Dental Anxiety Scale

- ORs

Odds Ratio

- UI

Universitas Indonesia

- SROH

Self-Rated Oral Health

- OHP

Oral Health Professional

- OHB

Oral Health Behaviors

- PLS-SEM

The Partial Least Square-Statistical Equation Model

- TAE

Toothache experience

- DV

Dental Visit

- HDI

Human Development Index

- WRI

Western Region of Indonesia

- ERI

Eastern Region of Indonesia

Author contributions

HN, KP, AR, and HDH prepared the Conceptualization. HN, KP, AR, IA and AB prepared and wrote methodology and software. HN and KP did validation of data process. HN, KP, AR and IA conducted formal analysis. HN, KP, AR, HDH, IA and AB did investigation and KP did the Data Collection. HN, KP, AR, IA and AB wrote original draft preparation. HN, AR, HDH, IA, and AB wrote, reviewed and editing process as well as Funding acquisition for this study and publication. All authors reviewed the manuscript and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work.

Funding

This research is funded by Directorate of Research and Development, Universitas Indonesia under “Hibah PUTI Q1 2024 (Grant no NKB-329/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2024).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available for ethical and privacy reasons.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Faculty of Dentistry Universitas Indonesia Research Ethics Committee (approval no.81/Ethical Approval/FKGUI/XI/2023), and each participant provided electronic informed consent (via Google Form). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki [12].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Greer AE. Relationship Between Dental Behaviors and Dental Anxiety among College Students. M.S. United States -- Louisiana: Southeastern Louisiana University; 2021.

- 2.Gasparro R, Di Spirito F, Cangiano M, De Benedictis A, Sammartino P, Sammartino G, Bochicchio V, Maldonato NM, Scandurra C. A Cross-Sectional study on cognitive vulnerability patterns in dental anxiety: the Italian validation of the dental fear maintenance questionnaire (DFMQ). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukumaran I, Taylor S, Thomson WM. The prevalence and impact of dental anxiety among adult new Zealanders. Int Dent J. 2021;71(2):122–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeddy N, Nithya S, Radhika T, Jeddy N. Dental anxiety and influencing factors: A cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey. Indian J Dent Res. 2018;29(1):10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minja IK, Kahabuka FK. Dental anxiety and its consequences to oral health care attendance and delivery. Anxiety Disord Child Adulthood 2019, 35.

- 6.Muneer MU, Ismail F, Munir N, Shakoor A, Das G, Ahmed AR, Ahmed MA. Dental anxiety and influencing factors in adults. Healthcare: 2022. MDPI; 2022. p. 2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Puteri WC, Ruata ANA, Ananda GC, Panama MGS, Puspitaningrum MS, Waskita FA, Palupi R. Literacy level on dental and oral health in health students (Non Dentisty). Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol 2020, 14(4).

- 8.AZODO CC. Association between oral health literacy and dental anxiety among dental outpatients. Nigerian J Med Dent Educ. 2019;1(12):8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhury CR, Khijmatgar S, Chowdhury A, Harding S, Lynch E, Gootveld M. Dental anxiety in first- and final-year Indian dental students. BDJ Open. 2019;5:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amelia S, Listiani D, Palupi R. The difference of dental anxiety levelon healthcare and Non-Healthcare students. Medico-Legal Update 2020, 20(4).

- 11.Nofiyanti D, Gracea RS, Diba SF, Friday LC, Yanuaryska RD. Factors influencing anxiety levels during dental radiographic examination among dental students. Malaysian J Med Health Sci 2023, 19(5).

- 12.Association WM. World medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mustafa RM, Alrabadi NN, Alshali RZ, Khader YS, Ahmad DM. Knowledge, attitude, behavior, and stress related to COVID-19 among undergraduate health care students in Jordan. Eur J Dentistry. 2020;14(S 01):S50–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novrinda H, Darwita RR, Subagyo KA. The effect of educational video on COVID-19 and dental emergency literacy among students during pandemic era. Eur J Dentistry 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Novrinda H, Lambe PT, Darwita RR, Lee J-Y. The use of mouthguards and related factors among basketball players in Indonesia. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waireri AW, Gichu N, Alumera H, Gathece L. Dental anxiety among dental students at the university of Nairobi dental school, Kenya. Int J Innovative Res Dev 2019, 8(7).

- 17.Riksavianti F, Samad R. Reliabilitas Dan validitas Dari modified dental anxiety scale Dalam versi Bahasa Indonesia (Reliability and validity of modified dental anxiety scale in the Indonesian version). J Dentomaxillofacial Sci. 2014;13(3):145–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maulina T, Nadiyah Ridho S, Asnely Putri F. Validation of modified dental anxiety scale for dental extraction procedure (MDAS-DEP). Open Dentistry J. 2019;13(1):358–63. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christina Makri D. Evaluation of dental anxiety and of its determinants in a Greek sample. Int J Caring Sci. 2020;13(2):791–803. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erhamza TS, Carpar KA. Relation to sociodemographic factors and habits with dental anxiety, dental fear, and quality of life among students of different faculties. J Contemp Dentistry. 2020;10(1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassem El Hajj H, Fares Y, Abou-Abbas L. Psychometric evaluation of the Lebanese Arabic version of the dental fear survey: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Organization WH. Oral health surveys: basic methods. 5th ed. World Health Organization; 2013.

- 23.Lawal FB. Global self-rating of oral health as summary tool for oral health evaluation in low-resource settings. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5(Suppl 1):S1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer Nature; 2021.

- 25.Kock N. WarpPLS user manual: version 8.0. In. Loredo. Texas, USA: ScriptWarp Systems™; 2022. p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Jasser R, Almashaan G, Alwaalan H, Alkhzim N, Albougami A. Dental anxiety among dental, medical, and nursing students of two major universities in the central region of the Kingdom of Saudi arabia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alansaari ABO, Tawfik A, Jaber MA, Khamis AH, Elameen EM. Prevalence and Socio-Demographic correlates of dental anxiety among a group of adult patients attending dental outpatient clinics: A study from UAE. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(12):6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan ZQ, Sa’idah IN, Rahman HA, Dhaliwal JS. Dental anxiety among undergraduate students of a National university in Brunei Darussalam. Progress Drug Discovery Biomedical Sci 2021, 4(1).

- 29.Dadalti MT, Cunha AJ, Souza TG, Silva BA, Luiz RR, Risso PA. Anxiety about dental treatment a gender issue. Acta Odontológica Latinoam. 2021;34(2):195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Done AE, Preoteasa E, Preoteasa ct, dental anxiety and dental attendance frequency of dental students versus students majoring in other fields. Romanian J Oral Rehabilitation 2024, 16(2).

- 31.Madfa AA, Al-Zubaidi SM, Shibam AH, Al-ansi WA, AL-Beshari LA, Al-Haj AM. Dental fear and anxiety levels of a University Population in a sample from Yemen.

- 32.Blumer S, Peretz B, Yukler N, Nissan S. Dental anxiety, fear and anxiety of performing dental treatments among dental students during clinical studies. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;44(6):407–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akomolafe AG, Fatusi OA, Folayan MO, Mosaku KS, Adejobi AF, Njokanma AR. Relationship between types of information, dental anxiety, and postoperative pain following third molar surgery: a randomized study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023;81(3):329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayu W, Joko S. Determinan Indeks Pembangunan Manusia Kawasan Timur Indonesia (KTI). Jurnal Magister Ekonomi Syariah. 2024;3(1 Juni):61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meshi D, Ellithorpe ME. Problematic social media use and social support received in real-life versus on social media: associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addict Behav. 2021;119:106949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivrikaya EC, Yilmaz O, Sivrikaya P. Dentist-patient communication on dental anxiety using the social media: A randomized controlled trial. Scand J Psychol. 2021;62(6):780–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A. A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolescence Youth. 2020;25(1):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winkler CH, Bjelopavlovic M, Lehmann KM, Petrowski K, Irmscher L, Berth H. Impact of dental anxiety on dental care routine and Oral-Health-Related quality of life in a German adult Population-A Cross-Sectional study. J Clin Med 2023, 12(16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Mueller M, Schorle S, Vach K, Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Schlueter N. Relationship between dental experiences, oral hygiene education and self-reported oral hygiene behaviour. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0264306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drachev SN, Brenn T, Trovik TA. Prevalence of and factors associated with dental anxiety among medical and dental students of the Northern state medical university, arkhangelsk, North-West Russia. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1454786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.AlRatroot S, Alotaibi G, AlBishi F, Khan S, Ashraf Nazir M. Dental anxiety amongst pregnant women: relationship with dental attendance and sociodemographic factors. Int Dent J. 2022;72(2):179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahlander A, Soares F, Grindefjord M, Dahllöf G. Factors associated with dental fear and anxiety in children aged 7 to 9 years. Dentistry J. 2019;7(3):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svensson L, Hakeberg M, Boman UW. Dental anxiety, concomitant factors and change in prevalence over 50 years. Community Dent Health. 2016;33(2):121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaffar BO, Alagl AS, Al-Ansari AA. The prevalence, causes, and relativity of dental anxiety in adult patients to irregular dental visits. Saudi Med J. 2014;35(6):598–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maden EA, Maden O, Karabulut B, Polat GG. Evaluation of factors affecting dental anxiety in adolescents. Cumhuriyet Dent J. 2021;24(3):244–55. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aggarwal S, Wright J, Morgan A, Patton G, Reavley N. Religiosity and spirituality in the prevention and management of depression and anxiety in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vermette D, Doolittle B. What educators can learn from the Biopsychosocial-Spiritual model of patient care: time for holistic medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(8):2062–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available for ethical and privacy reasons.