Abstract

Background

Late booking of antenatal care is a major contributing factor to the high rate of maternal deaths. Despite the World Health Organization’s recommendation for pregnant women to begin their first antenatal care visit within 12 weeks of gestation, delays in initiating antenatal care are common in sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, this study intended to examine the prevalence of late antenatal care booking and its predictors in extremely high (over 1,000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) and very high (between 500 and 1,000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries.

Methods

Our analysis utilized secondary data from the most recent Demographic and Health Surveys conducted between 2014 and 2022. A weighted sample of 74,552 women who had given birth within five years preceding the survey and had antenatal care visits for their last child were included. A multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression model was fitted. Statistical significance was declared at a p-value less than 0.05.

Results

The pooled prevalence of late antenatal care booking in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries was 70.16% (95% CI: 69.83,70.49). Poor wealth quantile (AOR = 1.71, 95%CI: 1.60,1.82), low community media exposure (AOR = 1.70, 95%CI: 1.63,1.78), grand multiparous (AOR = 1.66, 95%CI:1.52,1.81), no media exposure (AOR = 1.59, 95%CI, 1.52,1.67), married (AOR = 1.53, 95%CI: 1.44,1.63), middle wealth quantile (AOR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.33,1.51), not autonomous of house-hold decision-making (AOR = 1.28, 95%CI: 1.22,1.34), multiparous (AOR = 1.27, 95%CI, 1.18,1.35), secondary education (AOR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.16,1.34), family size of 5+ (AOR = 1.24, 95%CI:1.15,1.33), rural residence (AOR = 1.22, 95%CI: 1.15,1.30), big problem of distance (AOR = 1.20, 95%CI: 1.14,1.26), Not working (AOR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.11,1.23), partner’s no formal education (AOR = 1.17, 95%CI:1.08,1.27), age 15–24 years (AOR = 1.16, 95%CI:1.07,1.25), female household head (AOR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.80,0.91) were significant predictors of late antenatal care booking.

Conclusions

This study revealed that on average, seven in ten pregnant women in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries booked antenatal care late. Both individual and community-level factors influenced late antenatal care booking. The study recommends empowering women, improving rural healthcare access, and promoting comprehensive ANC education and community-based interventions to address late ANC booking in extremely high and very high maternal mortality SSA countries.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-025-07789-5.

Keywords: Antenatal care, Late booking, Multilevel analysis, DHS, SSA, Predictor factors

Background

Antenatal care (ANC) is essential for monitoring maternal health and fetal development, aiming to detect and manage pregnancy-related complications through medical care and health education [1]. As a key global strategy to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, early booking, ideally within the first trimester ensures timely access to vital services for a healthy pregnancy and safe delivery [2].

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3.1 aims to reduce global maternal mortality to fewer than 70 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030 [3]. Although maternal mortality dropped by 34.3% globally between 2000 and 2020, it remains unacceptably high in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, which recorded 545 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020 and accounted for 70% of global maternal deaths [4, 5]. Most maternal deaths are preventable through proven interventions, making their reduction a key global health priority [6].

According to the 2023 joint report by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the World Bank Group, and UNDESA, South Sudan, Chad and Nigeria had extremely high maternal mortality ratios (over 1,000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) [5]. Additionally, Central African Republic, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Somalia, Lesotho, Guinea, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, and Benin were categorized as having very high maternal mortality ratios countries in sub-Saharan Africa (500 to 1000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) [5].

The World Health Organization advises that pregnant women to have their first ANC visit during the first trimester (within the first 12 weeks) of gestation, followed by two and five visits in the second and third trimesters respectively [7]. It also advocates a shift from the focused ANC model, which recommends a minimum of four visits (ANC4+), to a more comprehensive approach involving eight contacts (ANC8+) that emphasizes the number, timing, and content of ANC contacts [7]. Early ANC is crucial for a healthy pregnancy and birth because it allows for early detection of potential complications, timely interventions, and access to essential health services for both the mother and baby [8].

ANC booking is the initial visit made by a pregnant woman. Late ANC booking refers to the initiation of ANC after the first trimester, usually beyond 12 weeks of pregnancy [9–11]. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the initiation of ANC in the first trimester, women mainly in sub-Saharan Africa delay their ANC booking [12, 13]. This delay is often due to limited awareness of the appropriate time to initiate ANC, the recommended number of visits, and a lack of understanding of pregnancy symptoms [9]. Globally, the prevalence of late ANC booking is around 57%, with a high discrepancy between developed and developing regions [10]. In developing countries, more than 55% of women booked late their ANC follow up compared to more than 15% in the developed region [10, 14].

Evidence shows that in low-income African countries, a significant proportion of maternal and neonatal deaths is often linked to delayed initiation of ANC [15, 16]. Late booking can reduce the effectiveness of ANC, as health problems might remain undetected or untreated for an extended period, potentially raising the risk of complications for both the mother and the baby [17]. It is essential to address the root causes that compel women to book late for ANC to effectively reduce maternal mortality and morbidity in resource-limited settings and to develop impactful maternal health interventions. However, there is a paucity of research on late ANC booking among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in countries with a high burden of maternal mortality. Furthermore, previous studies have typically been limited to specific countries and facility-based settings, which frequently failed to provide a broader perspective [17–20]. There is a pressing need for large-scale and high-quality population-based studies in sub-Saharan African, where a substantial share of maternal mortality takes place. Therefore, this study was aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of late ANC booking and its predictors among pregnant women in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries using nationally representative Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data. Identifying the factors influencing pregnant women’s delays in seeking care helps health policymakers and stakeholders design effective public health strategies to promote the timely initiation of ANC, thereby reducing maternal morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Study settings and data source

The study employed the latest Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from eight sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries with extremely high and very high maternal mortality ratios. The DHS is a comprehensive survey designed to gather nationally representative data on fundamental health indicators, including morbidity, mortality, and the use of maternal and child health services. The primary aim of DHS surveys is to offer high-quality data for monitoring and evaluating population health programs and to support evidence-based health policy development. DHS adhere to standardized procedures across all countries, including sampling, questionnaire design, data collection, cleaning, coding, and analysis, enabling cross-country comparisons [21]. The survey employed a multi-stage (two-stage) stratified sampling approach to select participants. Initially, enumeration areas were randomly selected, and in the second stage, households within those areas were randomly selected. The data used in this analysis were weighted to adjust for non-response and variations in the probability of selection.

The countries identified as having extremely high and very high maternal mortality ratios were selected from the 2023 maternal mortality estimation report jointly published by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the World Bank Group, and UNDESA [5]. According to the report; South Sudan, Chad, and Nigeria were identified as having extremely high maternal mortality ratios (over 1,000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births). Meanwhile, Central African, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Lesotho, Somalia, Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya and Benin were classified as having very high maternal mortality ratios (500 to 1000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) in sub-Saharan Africa. South Sudan, Somalia and Guinea Bissau were not included in the study due to the lack of a DHS dataset. One country, Central Africa was also excluded due to the data was collected 30 years back which is outdated. Finally, we included Chad, Nigeria, Liberia, Lesotho, Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya and Benin in our study (see Supplementary Table 1). In this study, women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who had given birth at least once in the five years preceding the survey and had ANC visit for their last child were included. We only computed the figures for the most recent birth, as recommended by DHS guidelines, even though data were available for all births to the women surveyed in the five years prior to the survey.

Variables and measurements

The outcome variable in this study was ‘late ANC booking.’ We classified the timing of the first ANC visit into two categories: early and late. Booking made after 12 weeks of gestation was categorized as late ANC booking, while booking made within the first 12 weeks was classified as early ANC booking [10, 22, 23]. Here, we considered the dependent variable a binary variable.

This study examined predictor variables at both the individual and community levels. These variables were chosen based on their theoretical relevance and practical importance to maternal healthcare utilization [24]. The study looked at individual-level factors including age (15–24, 25–34, 35–49), marital status (unmarried, married), education level (no formal education, primary, secondary, higher), occupation status (not working, working), Partners’ education (no formal education, primary, secondary, higher), family size (< 3, 3–5, 5+), wealth index (poor, middle, rich), mass media exposure (no, yes), sex of the household head (male, female), health insurance (no, yes), household decision-making autonomy (not autonomous, autonomous), parity (1, 2–4, 5+), ever-terminated pregnancy (no, yes) and wanted pregnancy of the last child (wanted, unwanted) [22].

The community-level variables considered were type of residence (urban, rural), community-level women’s literacy (low, high), community-level media exposure (low, high), community-level poverty (low, high), and distance from the health facility (big problem, not big problem) [22, 25, 26].

Community-level variables like type of residence and distance to health facilities were sourced directly from the DHS data set, retaining their original categorizations: Meanwhile, factors such as media exposure, literacy rate, and poverty were derived by aggregating individual-level data within the study clusters. These community-level variables were then, categorized as high or low based on the distribution of the proportional values computed for each variable. Then the cut-off point for categorization was determined based on the national median value, as these variables were not normally distributed [27].

Accordingly, community level of women’s education was classified as high if the proportion of women with at least primary level education was higher than the median cut-off value (50%) and low if the proportion was 50% or less [28]. Moreover, the wealth index was derived from data on various household assets to assess the cumulative wealth status of households. In the dataset, the categories for wealth index were presented as poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest. In this study, by merging poorest with poorer and richest with richer a new variable was generated with “poor”, “middle” and “rich” categories [29]. The community poverty level was classified as “high” when the proportion of reproductive women in the lowest wealth quintiles was greater than the median value, and “low” when the proportion was lower than the median value. Similarly, community level media exposure was determined by aggregating responses related to radio listening, TV watching, and newspaper reading. The variable was categorized as ‘high’ if the proportion of women with exposure to at least one form of media was greater than 50%, and ‘low’ otherwise [30].

Data analysis and model Building

The data were analyzed using Stata version 17 software [31]. Before analysis, the data were weighted by dividing the individual weight for women (v005/1,000,000) to ensure the representativeness of the DHS sample and to produce accurate estimates and standard errors. A multilevel mixed-effects binary logistic regression (both fixed and random effect) analysis was performed to determine factors at both the individual and community levels. Four models were applied in this study: the null model (without independent variables), model I (including individual-level factors), model II (including community-level factors), and model III (combining both individual- and community-level factors). To assess the model’s fit, model III, which included both individual and community-level variables, was chosen due to its highest likelihood ratio (LLR) and lowest deviance. Variables having a p-value of less than 0.2 in bivariable were used for multivariable analysis. Finally, in the multivariable analysis, Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81 confirmed the internal consistency of the items used in this study. Prior to fitting the final regression model, we evaluated multi-collinearity among the independent variables using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The results indicated no significant collinearity among the explanatory variables (mean VIF = 2.80). Previous studies have indicated that VIF values below 10 are considered acceptable [32, 33]. Findings were presented through narratives, tables, and figures.

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, percentages, and medians were used to summarize the data. Moreover, we evaluated model fitness using intraclass correlation coefficient, median odds ratio, proportional change in variance, and deviance. Finally, model III was identified as the best-fitting model for predicting late ANC booking among pregnant women, as it had the lowest deviance, 56,176.21 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Model comparison and random effect analysis result of late ANC booking in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries

| Random effect | Null model | Model I | Model II | Model III |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.46 |

| ICC (%) | 13.72 | 13.27 | 13.35 | 12.24 |

| MOR | 5.74 | 5.32 | 5.38 | 5.18 |

| PCV (%) | Ref | 19.35 | 17.74 | 25.80 |

| Model fitness | ||||

| Deviance | 87,822.09 | 56,886.54 | 72,299.87 | 56,176.21 |

Null model: No independent variables, Model I: Individual-level factors, Model II: Community-level factors, Model III: Combining both individual- and community-level factors, ICC: Intra-class Correlation Coefficient, MOR: Median Odds Ratio, PCV: Proportional Change in Variance

Results

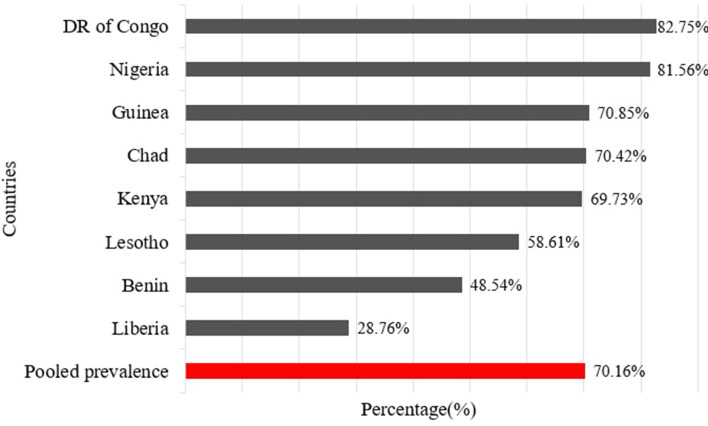

The pooled prevalence of late ANC booking among pregnant women in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries was 70.16% (95% CI: 69.83, 70.49). There were notable variations in the prevalence of late ANC booking across countries, with the highest, at 82.75% in Democratic Republic of Congo and the lowest at 28.76% in Liberia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of late ANC booking across countries in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries

Individual level factors

The analysis in this study included 74,552 women of reproductive age from eight sub-Saharan African countries, all of whom had given birth within the five years preceding the survey and had attended ANC visits for their most recent pregnancy. Most women (46.59%) were between the ages of 25 and 34. More than three-quarters (76.65%) were married. Additionally, 41.81% of the participants had no formal education. Around two-thirds (63.61%) were employed, and 57.20% had families with five or more members. Additionally, 35.20% of respondents’ partners were uneducated, and 42.29% came from the poor wealth quintiles. Additionally, 69.51% of the respondents had no exposure to media. The findings also revealed that 97.94% has no health insurance, over four-fifths (82.18%) lived with a male household head, and 69.62% had decision-making autonomy within the household. In terms of obstetric characteristics, 60.91% of the respondents gave birth to their last child in a health facility, and 46.61% had 2 to 4 children. Furthermore, 76.22% reported that their most recent pregnancy was wanted and 86.74% had experienced a terminated pregnancy (Table 2.

Table 2.

Individual level characteristics of respondents in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries (n = 74,552)

| Variables | Category | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current age in years | 15–24 | 21,940 | 29.43 |

| 25–34 | 34,733 | 46.59 | |

| 35–49 | 17,879 | 23.98 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 17,410 | 23.35 |

| Married | 57,142 | 76.65 | |

| Educational level of respondents | No education | 31,171 | 41.81 |

| Primary education (1–8) | 18,323 | 24.58 | |

| Secondary (9–12) | 20,477 | 27.47 | |

| Higher (college and above) | 4,582 | 6.15 | |

| Occupation status of respondents | Not working | 27,065 | 36.39 |

| Working | 47,311 | 63.61 | |

| Partners’ education | No education | 23,784 | 35.20 |

| Primary education (1–8) | 12,932 | 19.14 | |

| Secondary (9–12) | 21,626 | 32.01 | |

| Higher (college and above) | 9,223 | 13.65 | |

| Family size | < 3 | 9,924 | 13.31 |

| 3–5 | 21,984 | 29.49 | |

| 5+ | 42,644 | 57.20 | |

| Wealth index | Poor | 31,531 | 42.29 |

| Middle | 14,845 | 19.91 | |

| Rich | 28,176 | 37.79 | |

| Mass media exposure | No | 48,649 | 69.51 |

| Yes | 21,338 | 30.49 | |

| Sex of household head | Male | 61,269 | 82.18 |

| Female | 13,284 | 17.82 | |

| Having health insurance | No | 56,712 | 97.94 |

| Yes | 1,192 | 2.06 | |

| Household decision-making autonomy | Not autonomous | 19,909 | 30.38 |

| Autonomous | 45,626 | 69.62 | |

| Parity | 1 | 15,041 | 20.18 |

| 2–4 | 34,747 | 46.61 | |

| 5+ | 24,764 | 33.22 | |

| Ever terminated pregnancy | No | 64,647 | 86.74 |

| Yes | 9,885 | 13.26 | |

| Wanted pregnancy for the last child | Wanted | 56,801 | 76.22 |

| Unwanted | 17,724 | 23.78 |

Community-level factors

Almost two-thirds (64.98%) of the study participants resided in rural areas. Approximately 53.38% of the women came from communities with a high literacy rate, and about half (50.90%) had high community media exposure. Around half (52.06%) of the respondents lived in communities with low levels of poverty. Furthermore, 64.83% of the respondents did not face significant issues with distance from the health facility (Table 3).

Table 3.

Community-level characteristics of respondents in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan Africa countries (n = 74,552)

| Variables | Category | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Urban | 26,107 | 35.02 |

| Rural | 48,445 | 64.98 | |

| Community literacy status | Low | 34,753 | 46.62 |

| High | 39,799 | 53.38 | |

| Community media exposure | Low | 36,587 | 49.10 |

| High | 37,925 | 50.90 | |

| Community wealth status | Low | 38,812 | 52.06 |

| High | 35,740 | 47.94 | |

| Subjective distance from the health facility | Big problem | 22,053 | 35.17 |

| Not big problem | 40,653 | 64.83 |

Factors associated with late antenatal care booking among pregnant women in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries

As shown in Table 4, the odds of late ANC booking among pregnant women aged 15–24 years was 1.14 (AOR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.06, 1.23) times higher as compared to those women aged 35–49 years. We further observed that women in the poor and middle wealth quantiles were 1.71 (AOR = 1.71, 95%CI: 1.60, 1.82) and 1.41 (AOR = 1.41, 95%CI:1.33, 1.51) more likely to have late ANC booking than those women in the rich wealth quantile respectively. Moreover, women who have no jobs were 1.17 (AOR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.11, 1.23) times more likely to have late ANC booking as compared to their counterparts. In this study, the odds of having late ANC booking was 1.17 (AOR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.08, 1.27) and 1.24 (AOR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.16, 1.34) times higher for women whose partner had no educational and secondary education status respectively than for women whose partner had higher education level. Women with a family size of more than 5 members were 24% more likely to book late for ANC compared to those with fewer than 3 family members, 1.24 (AOR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.33). The odds of late ANC booking among women who were married was 1.53 (AOR = 1.53, 95%CI, 1.44, 1.63) times higher than their unmarried counterparts. Compared to women from male household heads, late ANC booking was lower by 15%, 0.85 (AOR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.80, 0.91) among women in female household heads. Our study has further revealed that women who were not autonomous in household decision-making were 28% more likely to book late for ANC compared to their counter parts 1.28 (AOR = 1.28, 95%CI: 1.22, 1.34). Furthermore, the likelihood of late ANC booking among women who had no media exposure was 1.59 (AOR = 1.59, 95%CI, 1.52, 1.67) times higher than their counterparts. The odds of late ANC booking was significantly higher among multiparous (AOR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.35) and grand multiparous women (AOR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.52, 1.81) compared to nulliparous women.

Table 4.

Multilevel logistic regression results of predictors associated with late ANC booking in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries (n = 74,552)

| Variables | ANC booking | Null model | Model 1 AOR (95% CI) | Model 2 AOR (95%CI) | Model 3 AOR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early n (%) | Late n (%) | |||||

| Individual level characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 15–24 | 6,677 (30.44) | 15,263 (69.56) | 1.16 (1.07, 1.25) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23)* | ||

| 25–34 | 10,687 (30.77) | 24,046 (69.23) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | ||

| 35–49 | 4,882 (27.31) | 12,997 (72.69) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Educational status of participants | ||||||

| No formal education | 7,538 (24.18) | 23,633 (75.82) | 1.05 (0.94, 1.18) | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) | ||

| Primary education | 5,433 (29.65) | 12,890 (70.35) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) | ||

| Secondary education | 7,148 (34.91) | 13,329 (65.09) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.18) | 1.04 (0.93, 1.16) | ||

| Higher education | 2,129 (46.45) | 2,454 (53.55) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poor | 7,194 (22.82) | 24,337 (77.18) | 1.93 (1.83, 2.05) | 1.71 (1.60, 1.82)* | ||

| Middle | 4,094 (27.58) | 10,751 (72.42) | 1.54 (1.45, 1.64) | 1.41 (1.33, 1.51)* | ||

| Rich | 10,959 (38.90) | 17,217 (51.10) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Not working | 7,372 (27.24) | 19,693 (72.76) | 1.19 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.11, 1.23)* | ||

| Working | 14,817 (31.32) | 32,494 (68.68) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Partners’ education | ||||||

| No education | 5,406 (22.73) | 18,377 (77.27) | 1.21 (1.12, 1.32) | 1.17 (1.08, 1.27)* | ||

| Primary | 3,802 (29.40) | 9,129 (70.60) | 1.09 (1.00, 1.18) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) | ||

| Secondary | 6,767 (31.29) | 14,860 (68.71) | 1.27 (1.19, 1.36) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.34)* | ||

| Higher | 3,711 (40.24) | 5,512 (59.76) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Family size | ||||||

| < 3 | 3,587 (36.14) | 6,338 (63.86) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3–5 | 7,057 (32.10) | 14,927 (67.90) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | ||

| 5+ | 11,603 (27.21) | 31,040 (72.79) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.35) | 1.24 (1.15, 1.33)* | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 6,270 (36.01) | 11,140 (63.99) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married | 15,977 (27.96) | 41,165 (72.04) | 1.56 (1.47, 1.66) | 1.53 (1.44, 1.63)* | ||

| Sex of household head | ||||||

| Male | 17,679 (28.86) | 43,589 (71.14) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 4,568 (34.39) | 8,716 (65.61) | 0.87 (0.82, 0.93) | 0.85 (0.80, 0.91)* | ||

| Health insurance | ||||||

| NO | 16,805 (29.63) | 39,907 (70.37) | 1.02 (0.88, 1.18) | 1.00 (0.86, 1.15) | ||

| Yes | 464 (38.95) | 728 (61.05) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Household decision-making autonomy | ||||||

| Not autonomous | 4,574 (22.97) | 15,335 (77.03) | 1.29 (1.23, 1.36) | 1.28 (1.22, 1.34)* | ||

| Autonomous | 14,591 (31.98) | 31,036 (68.02) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Media exposure | ||||||

| No | 12,770 (26.25) | 35,879 (73.75) | 1.60 (1.53, 1.68) | 1.59 (1.52, 1.67)* | ||

| Yes | 8,019 (37.58) | 13,319 (62.42) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 5,403 (35.92) | 9,638 (64.08) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multiparous | 11,059 (31.83) | 23,688 (68.17) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.33) | 1.27 (1.18, 1.35)* | ||

| Grand multiparous | 5,785 (23.36) | 18,979 (76.64) | 1.64 (1.51, 1.79) | 1.66 (1.52, 1.81)* | ||

| Ever terminated pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 18,937 (29.29) | 45,710 (70.71) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 22,243 (29.84) | 6,579 (66.56) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | ||

| Wanted of the last child | ||||||

| Wanted | 16,750 (29.49) | 40,051 (70.51) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Unwanted | 5,490 (30.98) | 12,234 (69.02) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | ||

| Community level variables | ||||||

| Residency | ||||||

| Urban | 10,018 (38.37) | 16,089 (61.63) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 12,229 (25.24) | 36,216 (74.76) | 1.79 (1.71, 1.87) | 1.22 (1.15, 1.30)* | ||

| Community literacy level | ||||||

| Low | 9,395 (27.03) | 25,357 (72.97) | 1.26 (1.13, 1.40) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) | ||

| High | 12,852 (32.29) | 26,948 (67.71) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Community media exposure | ||||||

| Low | 10,576 (28.91) | 26,011 (71.09) | 1.80 (1.72, 1.88) | 1.70 (1.63, 1.78)* | ||

| High | 11,646 (30.71) | 26,278 (69.29) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Community wealth status | ||||||

| Low | 12,540 (32.31) | 26,272 (67.69) | 0.90 (0.81, 1.00) | 0.97 (0.87, 1.09) | ||

| High | 9,707 (27.16) | 26,033 (72.84) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Subjective distance from the health facility | ||||||

| Big problem | 5,623 (25.50) | 16,430 (74.50) | 1.31 (1.26, 1.36) | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26)* | ||

| Not big problem | 13,017 (32.02) | 27,636 (67.98) | 1 | 1 | ||

*Statistically significant at p-value: <0.05, AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio, COR: Crude Odds Ratio, Model 1: Adjusted for individual-level characteristics, Model 2: Adjusted for community-level characteristics, Model 3: Adjusted for both individual and community-level characteristics

Regarding community-level factors, pregnant women living in rural areas were 22% more likely to have late ANC booking compared to those residing in urban dwellers 1.22 (AOR = 1.22, 95%CI: 1.15, 1.30). Moreover, the odds of late ANC booking among women from low community media exposure was (AOR = 1.70, 95%CI: 1.63, 1.78) times higher compared to high community media exposure. Women who faced significant challenges with the distance to a health facility had 1.20 times higher odds of booking late for ANC (AOR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.26) compared to those who did not perceive distance as a major issue.

Discussion

This study attempted to assess the pooled prevalence and predictors of late ANC booking in extremely high and very high maternal mortality sub-Saharan African countries. The study found that 70.16% of pregnant women booked late for ANC. This proportion of pregnant women who booked late was found higher compared to the studies conducted in Malaysia (27.6%) [34], Ethiopia (67.31% [22], Cameron (44%) [35], Debre Berhan (60%) [2], Woldia (59.5%) [36], Bhutan (67%) [37], Gambia (56%%) [38] and tertiary health institution in Nigeria (65%) [39], however was lower than studies conducted in Bududa District, Uganda (89%) [40], Ambo town, Ethiopia 86.8% [41], Fiji (79.7%) [42] and south Sudan (85%) [43]. This variation might be due to differences in study settings, awareness levels, accessibility of health services, and cultural practices across the countries or study areas. This finding was consistent with studies conducted in Mizan-Aman (70%) [44], southern Benin (75.4%) [45] and southern Nigeria (72.4%) [46].

The study has identified multiple individual and community-level factors that have a significant influence on late ANC booking among pregnant women in extremely high and very high maternal mortality SSA countries. In this study, younger women were observed more likely to have late ANC booking than older women. The odds of booking late ANC among pregnant women aged 15–24 years was 1.14 times higher as compared to those women aged 35–49 years. Similar associations were observed in previous studies; southern Ghana [47], East Wollega [48], and southwestern Nigeria [49]. However, this finding was in contrast with the study conducted in Zambia [50] and Malawi [51] where older women were more likely to delay ANC. This discrepancy may be attributed to contextual differences in health education, service accessibility, and sociocultural dynamics across settings. In some regions, such as Zambia and Malawi, younger women may receive more targeted reproductive health education through school-based or community programs which increases the awareness of the importance of early ANC. Additionally, younger women may be more exposed to health information via media or peer networks, or may face fewer responsibilities at home, making it easier to attend health services [52]. Conversely, in the current study setting, cultural norms, lack of autonomy, or limited experience with the healthcare system may contribute to younger women delaying care [53]. Differences in the organization and reach of maternal health services, including the availability of youth-friendly services, may also influence these patterns [54].

Moreover, we found a significant association between women’s household income and late ANC booking. In this study, women from low- and middle-income households were more likely to initiate ANC late compared to those from high-income households. This observation aligns with studies conducted in Ethiopia [55], Malawi [56], and India [57, 58] in which wealthier women were more likely to initiate ANC early compared to poorer women. The authors interpreted that the inability to afford direct or indirect healthcare costs, transportation challenges, and limited access to education about the benefits of early ANC booking may contribute to delays in ANC utilization among women from low- and middle-income households.

The job status of the women was another significant determinant factor. The likelihood of having late ANC booking was higher by 17% for those women who have no job in this study. This finding was inconsistent with the studies conducted in South Africa [59], Lundu district, Malayisia [60] and Nigeria [61]. The authors interpreted that this contrast may be due to better access to subsidized maternal health programs for unemployed women in South Africa, Malaysia, and Nigeria, which reduces barriers to early ANC booking.

We further found that women whose partners had no formal educational and secondary education status were found to have a higher likelihood of late ANC booking. Booking of late ANC was 1.17 and 1.24 times higher for women whose partner had no formal educational and secondary education status respectively than for women whose partner had a higher education level. This finding is congruent with other studies conducted in southern Ethiopia [62] and Zimbabwe [63]. A plausible explanation is that a higher level of educated partners may have a better understanding of the disadvantage of delayed ANC visits and support women to have early initiation of ANC visits. This implies that increasing educational opportunities for partners could potentially improve women’s initiation of early ANC visits. However, we did not find women’s education to be a predictor in this study. This may be due to the overriding influence of partners in healthcare decision-making or limited variability in women’s education levels, which could have reduced the power to detect a statistically significant association.

This study has revealed that women with a family size of 5 + were 24% more likely to book late for ANC compared to those women with fewer than three family members. This finding was supported by the previous study conducted in Ethiopia [55]. Possible reasons include limited financial resources caused by the burden of managing a large household on a modest income. In addition, being over occupied with family duties can be a reason to delays in ANC booking.

Another predictor associated with late ANC booking was marital status. We observed that the odds of late ANC booking among married women was 1.53 times higher than their unmarried counterparts. This finding contrasts the studies conducted in Lundu district, Malayisia [60], and Embu Teaching and Referral Hospital, Kenya [64]. This discrepancy might be due to differences in cultural norms, where in some contexts, unmarried women may face greater societal stigma or lack of support, leading to delayed ANC booking [65].

House hold head was a predictor the study found to be significantly associated with late ANC booking. Women from female household heads were 15% less likely to book later than those women from male household heads. Female household heads may have better decision-making power and awareness of the disadvantages of late ANC booking, making them more proactive in seeking early ANC [66].

Our study has further revealed that household decision-making autonomy was a significant determinant factor of late ANC booking. Women who were no autonomous for household decision making were 28% more likely to book ANC late compared to their counter parts. This may be due to a lack of control over healthcare decisions, as women without autonomy in household decision-making may face delays in seeking ANC due to dependence on others for approval [67].

In this study, health insurance was not significantly associated with late ANC booking. This may be due to the fact that ANC services are often provided free of charge or at minimal cost in many sub-Saharan African countries [68]. Consequently, financial barriers, typically addressed by health insurance are not the primary determinants of when women initiate antenatal care.

Consistent with previous studies in Masindi Hospital, Uganda [69] and Rwanda [70], our study has further revealed that the odds of late ANC booking was higher among women who had no media exposure compared to their counterparts. This finding may be explained by the fact that media exposure often increases awareness of the importance of initiating early ANC, providing women with the information needed to seek care promptly [71]. This finding highlights the importance of media as a tool for health education. It suggests that improving media exposure could enhance awareness about the benefits of early ANC, potentially reducing delays in ANC booking and improving positive pregnancy outcomes.

Parity was another significant predictor identified in our study, with higher parity associated with an increased likelihood of late ANC booking, similar to other studies in Ethiopia [22, 72], Ndola District, Zambia [73], and Myanmar [74]. Pregnant women with higher parity might book ANC late due to the burden of childcare or being occupied with managing a larger family. Another possible explanation could be that the health education received during previous pregnancies was ineffective in influencing or altering their behaviors.

Relating to community-level factors, women’s residence was significantly associated with late booking of ANC, indicating that community-level factors influence the likelihood of booking late ANC. Those pregnant women in rural areas were more likely to book late for ANC compared to women living in urban areas. This finding is in agreement with results from previous studies conducted in South Africa [59], Debre Markos Ethiopia [10], Malaysia [74] and Nigeria [75]. This may be because rural women are less likely to utilize maternal health services, such as timely initiation of ANC, due to limited availability and accessibility, as well as the unequal distribution of health facilities and healthcare personnel between urban and rural areas [76]. Moreover, rural women may encounter cultural barriers that hinder the early initiation of ANC, such as requiring their spouse’s approval.

Another identified factor that influenced late ANC booking in this study was community media exposure. The odds of late ANC booking among women from low community media exposure was 1.70 times higher as compared to their high community media exposure counterparts. This finding was congruent by the other studies done in southern Ethiopia [77], and Ghana [47]. This could be attributed to the fact that women exposed to media are more informed about the availability of maternal healthcare services and the advantages of utilizing these services promptly. This has an implication that low media exposure at the community level may contribute to delayed ANC booking among pregnant women.

In this study, it was observed that there was a significant association between distance from the health facility and late ANC booking. In agreement with a previous studies in Camerron [78], northern Uganda [79], and Ethiopia [80], those women with a big problem of distance from the health facility had 1.20 higher odds of booking late for ANC as compared to women with no big problem of distance from the health facility. This is because women living far from maternity facilities may face additional transportation costs and limited availability of transport, which can prevent them from accessing ANC services on time [81].

Strengths and limitations of the study

The key strength of this study lies in its utilization of nationally representative survey data and a large sample size. Moreover, it applied a multilevel mixed effect model to find a more valid result and to account the hierarchical nature of the survey data. Although the study has notable strengths, it also has limitations since the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between the dependent and independent variables. There might be a recall bias among the surveyed women since we used the most recent live births in the past five years before the survey.

Conclusions

Our study concluded that a significant proportion of pregnant women in extremely high and very high maternal mortality SSA countries booked ANC late. Moreover, the study identified age 15–24 years, poor wealth quantiles, middle wealth quantiles, not working, partner’s educational status of no formal education, primary education and secondary education, family size of 5+, being married, female household head, not autonomous of household decision-making, no media exposure, multiparous and grand multiparous as individual-level predictors of late ANC booking. Furthermore, rural residency, low community media exposure and big problem of distance from the health facility were identified as community-level predictors of late booking for ANC among pregnant women. Thus, this study emphasizes the need for integrated strategies of community engagement, policy reform, and health system improvements to effectively reduce late ANC booking in SSA countries with extremely high and very high maternal mortality. It recommends empowering women, improving rural healthcare access, and promoting comprehensive ANC education and community-based interventions to address late ANC booking in extremely high and very high maternal mortality SSA countries.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the DHS programs for the permission to use all the relevant data for this study.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Ante Natal Care

- AOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- DHS

Demography and Health Survey

- ICC

Intra-class Correlation Coefficient

- MMR

Maternal Mortality ratio: MOR: Median Odds Ratio

- PCV

Proportional Change in Variance

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. TZT conceived the idea, extracted the data, conducted analysis, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. KAD, GT, MGT, ED, DMG, AH, NW and MJ critically edited, revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have participated in the data analysis and interpretation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not funding was secured for this study.

Data availability

Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), which is freely available online at (https://dhsprogram.com).

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study did not involve information gathering from the study participants. Participants’ consent is inapplicable because the data is secondary and is available in the public domain. All procedures were applied per the Helsinki declarations. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available online at (http://www.dhsprogram.com).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wolde HF, Tsegaye AT, Sisay MM. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in addis Zemen primary hospital, South gondar, Ethiopia. Reproductive Health. 2019;16(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolola T, Morka W, Abdissa B. Antenatal care booking within the first trimester of pregnancy and its associated factors among pregnant women residing in an urban area: a cross-sectional study in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e032960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solnes Miltenburg A, Kvernflaten B, Meguid T, Sundby J. Towards renewed commitment to prevent maternal mortality and morbidity: learning from 30 years of maternal health priorities. Sex Reproductive Health Matters. 2023;31(1):2174245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okonji OC, Nzoputam CI, Ekholuenetale M, Okonji EF, Wegbom AI, Edet CK. Differentials in maternal mortality pattern in Sub-Saharan Africa countries: evidence from demographic and health survey data. Women. 2023;3(1):175–88. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organization WH, UNICEF, UNFPA. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates by WHO. World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division: World Health Organization; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girum T, Wasie A. Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries. Maternal Health Neonatology Perinatol. 2017;3:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Organization WH. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed]

- 8.Bola R, Ujoh F, Ukah UV, Lett R. Assessment and validation of the community maternal danger score algorithm. Global Health Res Policy. 2022;7(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ndomba A, Ntabaye M, Semali I, Kabalimu T, Ndossi G, Mashalla Y. Prevalence of late antenatal care booking among pregnant women attending public health facilities of Kigamboni municipality in Dar Es Salaam region, Tanzania. Afr Health Sci. 2023;23(2):623–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alem AZ, Yeshaw Y, Liyew AM, Tesema GA, Alamneh TS, Worku MG, Teshale AB, Tessema ZT. Timely initiation of antenatal care and its associated factors among pregnant women in sub-Saharan africa: A multicountry analysis of demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0262411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anaba EA, Afaya A. Correlates of late initiation and underutilisation of the recommended eight or more antenatal care visits among women of reproductive age: insights from the 2019 Ghana malaria Indicator survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e058693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alemu AA, Zeleke LB, Jember DA, Kassa GM, Khajehei M. Individual and community level determinants of delayed antenatal care initiation in ethiopia: A multilevel analysis of the 2019 Ethiopian Mini demographic health survey. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(5):e0300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musendo M, Chideme-Munodawafa A, Mhlanga M, Ndaimani A. Delayed first antenatal care visit by pregnant women. Correlates in a Zimbabwean Peri-urban district. Int J Innovative Res Dev. 2016;5(7):307–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moller A-B, Petzold M, Chou D, Say L. Early antenatal care visit: a systematic analysis of regional and global levels and trends of coverage from 1990 to 2013. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(10):e977–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musarandega R, Nyakura M, Machekano R, Pattinson R, Munjanja SP. Causes of maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan africa: a systematic review of studies published from 2015 to 2020. J Global Health 2021, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Said A, Malqvist M, Pembe AB, Massawe S, Hanson C. Causes of maternal deaths and delays in care: comparison between routine maternal death surveillance and response system and an obstetrician expert panel in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tadele F, Getachew N, Fentie K, Amdisa D. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in Jimma zone public hospitals, Southwest ethiopia, 2020. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adulo LA, Hassen SS. Magnitude and factors associated with late initiation of antenatal care booking on first visit among women in rural parts of Ethiopia. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2023;10(4):1693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samiah S, Stanikzai MH, Wasiq AW, Sayam H. Factors associated with late antenatal care initiation among pregnant women attending a comprehensive healthcare facility in Kandahar province, Afghanistan. Indian J Public Health. 2021;65(3):298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komuhangi G. Socio-Demographics and late antenatal care seeking behavior: a cross sectional study among pregnant women at Kyenjojo General Hospital, Western Uganda. 2020.

- 21.Tamirat KS, Sisay MM, Tesema GA, Tessema ZT. Determinants of adverse birth outcome in Sub-Saharan africa: analysis of recent demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teshale AB, Tesema GA. Prevalence and associated factors of delayed first antenatal care booking among reproductive age women in ethiopia; a multilevel analysis of EDHS 2016 data. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0235538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tola W, Negash E, Sileshi T, Wakgari N. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Ilu Ababor zone, Southwest ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0246230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh PK, Kumar C, Rai RK, Singh L. Factors associated with maternal healthcare services utilization in nine high focus States in india: a multilevel analysis based on 14 385 communities in 292 districts. Health Policy Plann. 2014;29(5):542–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appiah F. Individual and community-level factors associated with early initiation of antenatal care: multilevel modelling of 2018 Cameroon demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4):e0266594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zegeye AF, Asmamaw DB, Negash WD, Belachew TB, Fentie EA, Kidie AA, Baykeda TA, Fetene SM, Addis B, Maru Wubante S. Prevalence and determinants of post-neonatal mortality in East africa: a multilevel analysis of the recent demographic and health survey. Front Pead. 2025;13:1380913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liyew AM, Teshale AB. Individual and community level factors associated with anemia among lactating mothers in Ethiopia using data from Ethiopian demographic and health survey, 2016; a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jejaw M, Demissie KA, Tiruneh MG, Abera KM, Tsega Y, Endawkie A, Negash WD, Workie AM, Yohannes L, Getnet M. Prevalence and determinants of unintended pregnancy among rural reproductive age women in Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birhanu BE, Kebede DL, Kahsay AB, Belachew AB. Predictors of teenage pregnancy in ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shifti DM, Chojenta C, Holliday G, Loxton E. Individual and community level determinants of short birth interval in ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0227798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kothari P. Data analysis with STATA. Packt Publishing Ltd; 2015.

- 32.Kyriazos T, Poga M. Dealing with multicollinearity in factor analysis: the problem, detections, and solutions. Open J Stat. 2023;13(3):404–24. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leiby BD, Ahner DK. Multicollinearity applied Stepwise stochastic imputation: a large dataset imputation through correlation-based regression. J Big Data. 2023;10(1):23. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim P, Nasir F, Khuan L, Ahmad N. Factors associated with late booking of antenatal care among pregnant women during covid-19 pandemic. Malaysian J Public Health Med. 2023;23(2):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Budu E, Mohammed A, Adu C, Agbaglo E, Ameyaw EK, Yaya S. Factors associated with the number and timing of antenatal care visits among married women in cameroon: evidence from the 2018 Cameroon demographic and health survey. J Biosoc Sci. 2022;54(2):322–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adere A, Tilahun S. Magnitude of late initiation of antenatal care and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Woldia public. Ethiopia: Health Institution, North Wollo; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorji T, Das M, Van den Bergh R, Oo MM, Gyamtsho S, Tenzin K, Tshomo T, Ugen S. If we miss this chance, it’s futile later on–late antenatal booking and its determinants in bhutan: a mixed-methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nigatu SG, Birhan TY. The magnitude and determinants of delayed initiation of antenatal care among pregnant women in gambia; evidence from Gambia demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nnamani C, Onwusulu D, Offor C, Ekwebene O. Timing and associated factors of antenatal booking among pregnant women at a tertiary health institution in nigeria: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 2022;3(2):1646. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okwany J, Kimono A, FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO LATE ANTENATAL CARE BOOKING AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN IN BUDUDA HOSPITAL IN BUDUDA DISTRICT. Student’s J Health Res Afr. 2023;4(6):9–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damme TG. Factors associated with late antenatal care attendance among pregnant women attending health facilities of Ambo town, West Shoa zone, oromia region, central Ethiopia. Int J Med Pharm Sci. 2015;1(2):56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maharaj R, Mohammadnezhad M, Khan S. Characteristics and predictors of late antenatal booking among pregnant women in Fiji. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26(8):1667–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nasira Boi A, Izudi J, Atim F. Timely attendance of the first antenatal care among pregnant women aged 15–49 living with HIV in juba, South Sudan. Adv Public Health. 2022;2022(1):3252906. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Battu GG, Kassa RT, Negeri HA, Kitawu LD, Alemu KD. Late antenatal care booking and associated factors among pregnant women in mizan-aman town, South West ethiopia, 2021. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(1):e0000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekholuenetale M, Nzoputam CI, Barrow A, Onikan A. Women’s enlightenment and early antenatal care initiation are determining factors for the use of eight or more antenatal visits in benin: further analysis of the demographic and health survey. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Utuk NM, Ekanem A, Abasiattai AM. Timing and reasons for antenatal care booking among women in a tertiary health care center in Southern Nigeria. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6(9):3731–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manyeh AK, Amu A, Williams J, Gyapong M. Factors associated with the timing of antenatal clinic attendance among first-time mothers in rural Southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ejeta E, Dabsu R, Zewdie O, Merdassa E. Factors determining late antenatal care booking and the content of care among pregnant mother attending antenatal care services in East Wollega administrative zone, West Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J 2017, 27(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Adekanle D, Isawumi A. Late antenatal care booking and its predictors among pregnant women in South Western Nigeria. Online J Health Allied Sci 2008, 7(1).

- 50.Sinyange N, Sitali L, Jacobs C, Musonda P, Michelo C. Factors associated with late antenatal care booking: population based observations from the 2007 Zambia demographic and health survey. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palamuleni ME. Factors associated with late antenatal initiation among women in Malawi. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(2):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goodyear VA, Armour KM, Wood H. Young people and their engagement with health-related social media: New perspectives. Sport, education and society 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Idris IB, Hamis AA, Bukhori ABM, Hoong DCC, Yusop H, Shaharuddin MA-A, Fauzi NAFA, Kandayah T. Women’s autonomy in healthcare decision making: a systematic review. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golestani R, Farahani FK, Peters P. Exploring barriers to accessing health care services by young women in rural settings: a qualitative study in australia, canada, and Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dewau R, Muche A, Fentaw Z, Yalew M, Bitew G, Amsalu ET, Arefaynie M, Mekonen AM. Time to initiation of antenatal care and its predictors among pregnant women in ethiopia: Cox-gamma shared frailty model. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuuire VZ, Kangmennaang J, Atuoye KN, Antabe R, Boamah SA, Vercillo S, Amoyaw JA, Luginaah I. Timing and utilisation of antenatal care service in Nigeria and Malawi. Glob Public Health. 2017;12(6):711–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tripathy A, Mishra PS. Inequality in time to first antenatal care visits and its predictors among pregnant women in india: an evidence from National family health survey. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhatia M, Dwivedi LK, Banerjee K, Bansal A, Ranjan M, Dixit P. Pro-poor policies and improvements in maternal health outcomes in India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ebonwu J, Mumbauer A, Uys M, Wainberg ML, Medina-Marino A. Determinants of late antenatal care presentation in rural and peri-urban communities in South africa: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0191903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiee SFA. Late antenatal booking and its predictors in Lundu district of sarawak, Malaysia. Int J Public Health Res. 2018;8(2):956–64. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Solanke BL, Oyediran OO, Opadere AA, Bankole TO, Olupooye OO, Boku UI. What predicts delayed first antenatal care contact among primiparous women? Findings from a cross-sectional study in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tufa G, Tsegaye R, Seyoum D. Factors associated with timely antenatal care booking among pregnant women in remote area of bule hora district, Southern Ethiopia. Int J women’s health 2020:657–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Nyereyemhuka NC, Mavondo GA, Moyo O, Farai C, Nkazimulo M, Chavani O, Chamisa AJ. An analysis of factors contributing to late focused antenatal clinic (FANC) booking for pregnant women attending Hartcliffe polyclinic in harare, Zimbabwe. Asian J Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;3(2):26–46. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jemutai F, Impwii DK. Determinants of early antenatal care booking among pregnant women attending Embu teaching and referral hospital, Kenya: A Cross-sectional Survey.

- 65.Erasmus MO, Knight L, Dutton J. Barriers to accessing maternal health care amongst pregnant adolescents in South africa: a qualitative study. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:469–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dibaba B, Bekena M, Dingeta T, Refisa E, Bekele H, Nigussie S, Amentie E. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Hiwot Fana comprehensive specialized hospital, Eastern ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Front Global Women’s Health. 2024;5:1431876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haile A, Lonsako AA, Kebede FA, Adisu A, Elias A, Kasse T. Women autonomy in health care decision making and associated factors among postpartum women in Southern ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7(12):e70245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fabienne Richard MA, Witter S, Kelley A, Isidore, Sieleunou YK, Meessen B. Fee Exemption for Maternal Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of 11 Countries and Lessons for the Region. 2013.

- 69.Innocent M, Nderelimana O, Muv E, Habtu M, Rutayisire E. Factors influencing late utilization of first antenatal care services among pregnant women in Rwanda. J Clin Rev Case Rep. 2021;6(5):628–34. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Omona K, Kemigisha I, Mugume T, Muhanguzi A, Lubega S, Atuhaire O. Factors associated with late antenatal enrolment among pregnant women aged 15–49 Years At Masindi Hospital. 2021.

- 71.Phiri M, Mwanza J, Mwiche A, Lemba M, Malungo JR. Delay in timing of first antenatal care utilisation among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan africa: a multilevel mixed effect analysis. J Health Popul Nutr. 2025;44(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Ekholuenetale M, Shah V, Kadio B, Udenigwe O. Timing and adequate attendance of antenatal care visits among women in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chewe MM, Muleya MC, Maimbolwa M. Factors associated with late antenatal care booking among pregnant women in Ndola district, Zambia. Afr J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2016;10(4):169–78. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aung TZ, Oo WM, Khaing W, Lwin N, Dar HT. Late initiation of antenatal care and its determinants: a hospital based cross-sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3(4):900–5. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aliyu AA, Dahiru T. Predictors of delayed Antenatal Care (ANC) visits in Nigeria: secondary analysis of 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS). The Pan African medical journal 2017, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Samuel O, Zewotir T, North D. Decomposing the urban–rural inequalities in the utilisation of maternal health care services: evidence from 27 selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health. 2021;18:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geta MB, Yallew WW. Early initiation of antenatal care and factors associated with early antenatal care initiation at health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2017;2017(1):1624245. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tolefac PN, Halle-Ekane GE, Agbor VN, Sama CB, Ngwasiri C, Tebeu PM. Why do pregnant women present late for their first antenatal care consultation in cameroon?? Maternal Health Neonatology Perinatol. 2017;3:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turyasiima M, Tugume R, Openy A, Ahairwomugisha E, Opio R, Ntunguka M, Mahulo N, Akera P, Odongo-Aginya E. Determinants of first antenatal care visit by pregnant women at community based education, research and service sites in Northern Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2014;91(9):317–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weldemariam S, Damte A, Endris K, Palcon MC, Tesfay K, Berhe A, Araya T, Hagos H, Gebrehiwot H. Late antenatal care initiation: the case of public health centers in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sialubanje C, Massar K, van der Pijl MS, Kirch EM, Hamer DH, Ruiter RA. Improving access to skilled facility-based delivery services: women’s beliefs on facilitators and barriers to the utilisation of maternity waiting homes in rural Zambia. Reproductive Health. 2015;12:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), which is freely available online at (https://dhsprogram.com).