Abstract

Objectives

This study investigated the nanomechanical properties, microstructure, and composition of dentinogenesis imperfecta type II (DGI-II) peritubular dentin (PTD) and intertubular dentin (ITD) and examined the correlations between them.

Materials and methods

Six samples from each of the normal and DGI-II groups were prepared by cutting the midcoronal dentin perpendicular to the dentin tubules. The number and morphology of the dentin tubules were then observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Hydroxyapatite (HAP) was detected using high-resolution atomic force microscopy (HR-AFM). The chemical composition was determined using atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR). The nanomechanical properties were evaluated using amplitude modulation-frequency modulation (AM-FM) techniques. Finally, a multiple linear regression (MLR) model was used to verify the correlations between PTD and ITD.

Results

SEM of the DGI-II dentin revealed a considerable reduction in the number and area of the tubules. HR-AFM revealed dramatic increases in the HAP particle size and DGI-II dentin nanoscale roughness, especially PTDs. AFM-IR revealed that in the DGI-II groups, the phosphate content decreased in both the PTDs and ITDs, whereas the amide I (A-I) and amide II (A-II) content was elevated in the ITDs. AM-FM testing revealed a considerable reduction in the Young’s modulus and increases in the PTD and ITD indentations in the DGI-II dentin. MLR demonstrated that the changes in microstructure and composition were related to a decrease in the nanomechanical properties of the DGI-II dentin.

Conclusions

The DGI-II dentin nanomechanical properties deteriorated considerably, especially those of the PTDs, presumably because of alterations in the HAP and chemical composition.

Clinical relevance

Understanding the nanomechanical properties, microstructure, and composition of DGI-II dentin could help dentists develop novel individualized restorative techniques.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-06315-5.

Keywords: Dentinogenesis imperfecta, Peritubular dentin, Intertubular dentin, Microstructure, Chemical composition, Nanomechanical properties

Introduction

Dentinogenic imperfecta (DGI) is a hereditary disorder that affects dentin formation and the mineralization of dentin [1]. DGI can be categorized into three types—that is, DGI-I, DGI-II, and DGI-III [2]. In DGI-II, the lack of scalloping at the dentin-enamel junction renders enamel prone to detachment from the dentin, leading to rapid tooth wear [3]. Our previous research revealed that the mechanical properties of DGI-II dentin—particularly its tribological performance—are inferior to those of normal dentin [4]. Consequently, patients with DGI-II have varying degrees of teeth abrasion and a decrease in the occlusal vertical dimension, which can lead to dentition defects in severe cases [5–7]. Given that dentin serves as the substrate used in most current restorative procedures, a thorough understanding of the correlation between the structural and mechanical properties of the dentin matrix is critical to the success of restorative dental materials. Consequently, a thorough study of changes in the nanomechanical properties and microstructure of DGI-II coronal dentin is of considerable importance in revealing the mechanism of clinical symptoms and the treatment of patients with DGI-II.

Dentin, which constitutes the major portion of teeth, primarily comprises hydroxyapatite (HAP) as its inorganic component with approximately 90% of its organic matrix comprising type I collagen. Research has indicated that deep dentin manifests inferior resilience relative to superficial dentin, attributable to the elevated mineral-to-collagen ratio in the deep dentin [8]. Moreover, the mineral density and microhardness are considerably lower, with the amount of Mg being reduced in the dentin of a DGI-II sample compared to that of the wild type [9]. Additionally, our previous research has shown that the tribological properties of DGI-II dentin are reduced, intimately linked to the disordered microstructure and compositional deficiencies [4]. These studies suggest that the mechanical properties of dentin are closely related to its structure and composition.

Dentin tubules—a distinct and important structure of dentin—have a tubule diameter that gradually expands from 0.8 μm at the dentin-enamel junction (DEJ) to 2.5 μm in the vicinity of the proximal pulp [10]. The highly mineralized structure surrounding the tubules—known as peritubular dentin (PTD)—is approximately 0.5–1 μm thick. The reticular structure with collagen fibers is known as intertubular dentin (ITD) [11]. PTDs and ITDs are composed of different volume fractions of collagen and HAP at the nanoscale. Moreover, the collagen imparts a certain degree of viscoelasticity to the dentin, whereas the HAP imparts strength and hardness to it [12]. Accordingly, ITDs and PTDs have been found to have a notable effect on the mechanical properties and fracture behavior of dentin [13, 14]. From a macroscopic to microscopic perspective, although current research on the biomechanical properties and structure of dentin has been continuously deepening [15–19], studies on the nanomechanical properties and microstructures of PTDs and ITDs in DGI-II dentin have yet to be reported.

The methods used in previous studies on the mechanical properties and structure of DGI-II dentin have been of low resolution, limiting distinct resolving of the PTDs and ITDs. Forien et al. [20] visualized the spatial distribution of nanocrystalline HAP around the dentin tubules using X-ray diffraction nanotomography but failed to differentiate between the ITDs and PTDs. Zanette et al. [21] used ptychographic X-ray tomography to distinguish the ITDs and PTDs. Although they quantified the difference in mineralization density between them, they did not investigate differences in the elemental distribution and nanocrystalline structure between the ITDs and PTDs. Huang et al. [22] employed atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR) and amplitude modulation-frequency modulation (AM-FM) for the first time to determine the chemical composition and mechanical properties of normal human dentin at the nanoscale. Additionally, they found that the mineral content and elastic modulus of the PTDs were higher than those of the ITDs. Consequently, in this study, we analyzed the heterogeneity of the structure, chemical composition, and nanomechanical properties of PTDs and ITDs in normal and DGI-II dentin using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), high-resolution atomic force microscopy (HR-AFM), AM-FM, and AFM-IR. Ultimately, we aim to understand the correlation between the nanomechanical properties, microstructure, and chemical composition, to pave the way for the development of improved dental materials and treatment strategies.

Materials and methods

Tooth collection and specimen Preparation

Mandibular caries-free third molars from 20- to 23-year-old males(n = 6) requiring extraction as part of their dental treatment were collected from three normal and three DGI-II patients from different families. This study was conducted with the approval of the Wenzhou Medical University Ethics Committee (WYKQ2023006). After extraction, the teeth were immediately rinsed with massive saline at room temperature to remove any blood, and any soft tissue from the surface of the teeth was carefully removed using instruments. After thorough cleaning and careful treatment, the teeth were stored in saline at 4 ℃. The patients were free of systemic diseases and in good physical condition.

The crown was sectioned from each tooth using a diamond-coated band saw (Minitom; Struers, Copenhagen, Denmark) under running water. Two samples (2 × 2 × 2 mm) perpendicular to the dentin tubules per tooth were collected. Each group comprised 12 dentin discs, with six discs allocated for SEM analysis and the remaining six discs reserved for other experiments in this study. After being embedded in resin, the samples were ground using #800 sandpaper under cold water. All samples were then ground successively using a series of silicon carbide papers (1200, 1500, 2400 and 3000 grit), and polished with 2.5, 1.5, 1.0, 0.5, and 0.25 μm diamond paste, in that order. All samples were ultrasonically washed with distilled water to remove any debris.

Scanning Electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

All specimens were immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 24 h to achieve chemical fixation, dehydrated—which involved the replacement of aqueous components and fixatives through an ascending ethanol series—air-dried to eliminate residual dehydrating agents to prepare the specimen for vacuum compatibility, and coated with a 10-nm Au thin film under vacuum condition using a mini sputter coater (SC7620, Quorum Technologies, Laughton, East Sussex, UK). A scanning electron microscope (Hitachi SU8010) was used to image the most representative area where the morphology and quantity of dentin tubules were relatively uniform in each group at different magnifications. The SEM images were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 image analysis software (Media Cybernetics, USA) to determine the boundaries of the dentin tubules via grayscale gradient analysis, which in turn could be used to calculate the number and area of the tubules [23]. Five representative images were acquired per dentin disk and the image-derived measurements were averaged to generate an individual value per disk.

High-resolution atomic force microscopy imaging

High-resolution topography (height images), magnitude images, and phase images were obtained using commercial AFM (MFP-3D, Oxford Instruments, High Wycombe, UK). At least five sets of AFM images were taken in the normal group and DGI-II group respectively. The magnitude images revealed the material morphology, and the phase images were used to identify areas with different material phases (such as the composition and elasticity, amongst others) [24]. A large area (10 × 10 μm) was initially mapped to identify the PTD and the ITD regions on specimen surfaces. Height and phase mapping (3 × 3 nm2) of the PTDs and ITDs were then performed over a scanned area of 1 × 1 μm. The HAP sizes of the PTDs and ITDs were analyzed using ImageJ particle analysis software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). In this study, the HAP nano-roughness was quantified via HR-AFM using the root mean square (RMS) of the surface height variations [25]. The roughness parameters for each image were calculated using Gwyddion freeware [26].

Atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy

The IR absorption spectra were obtained using a Nano-IR2s instrument (Anasys Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The instrument consists of a tunable infrared laser focused on a sample in the proximity of the AFM probe tip. The oscillation amplitude of the AFM cantilever was recorded at each laser wavenumber to determine the IR absorption of each specimen. The correspondence between the molecular groups and wavenumber in summarized in Table 1 in the Appendix. The baseline for each spectrum was determined through local minimum fitting. The baseline was then subtracted from the corresponding wave peak of the functional group as the absorbance intensity to eliminate IR absorption interference in the matrix and thick samples [22]. The carbonate/phosphate (CO32−/PO43−) ratio—which is an indication of the degree of carbonate substitution for phosphate—was calculated from the ratio of the integrated area under carbonate (CO33 − v3) and phosphate (PO43−ν1, ν3) bands [27, 28].

Table 1.

Multiple linear regression and associated p values

| Independent variables | The Young’s modulus of the PTD | The Young’s modulus of the ITD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | p value | 95% CI | Coef. | SE | p value | 95% CI | |||

| Constant | 21.296 | 5.522 | p < 0.05 | 9.590 | 33.002 | 33.694 | 12.640 | p < 0.05 | 6.897 | 60.490 |

| CO32−/PO43− ratio | -8.412 | 1.039 | p < 0.001 | -10.614 | -6.211 | 0.158 | 1.683 | p < 0.05 | -3.411 | 3.727 |

| A-I/A-III ratio | 9.864 | 3.202 | p < 0.05 | 3.075 | 16.653 | 3.236 | 3.502 | p < 0.05 | -4.188 | 10.661 |

| HAP size | -0.017 | 0.013 | p < 0.05 | -0.045 | 0.010 | -0.052 | 0.016 | p < 0.01 | -0.086 | -0.018 |

| p < 0.001, R2 = 0.996. | p < 0.001, R2 = 0.914. | |||||||||

Amplitude modulation-frequency modulation testing

The mechanical properties of the PTDs and ITDs under wet conditions were examined at the nanoscale using an Asylum Research MFP-3D Infinity AFM system with AM-FM mode. An AC160TS-R3 probe from Olympus Corporation was used for the AM-FM. The specimens were scanned directly in AM-FM mode without any processing. The scanning speed was set at 0.5 line/s.

Statistical analysis

All data shown are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The crystal size, A-I/A-III ratio, indentation depth, and Young’s modulus of the PTDs and ITDs in the two groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Finally, MLR was used to verify the correlations between the aforementioned criteria. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

SEM results

SEM revealed that the tubules in the normal group (Fig. 1A and B) were uniformly distributed and regular in shape. By contrast, the number of DGI-II dentin tubules (Fig. 1D and E) decreased significantly, and the shape of the tubules was irregular. Additionally, the PTD surface of the normal group was smooth and the ITD surface was slightly rough (Fig. 1C). Irregular hydroxyapatite crystals filled the DGI-II dentinal tubule area (Fig. 1F), and the surfaces of the PTDs and ITDs were rough and uneven. Quantitative analyses (Fig. 1G and H) showed that the number and area of the dentin tubules in the DGI-II group were significantly lower than those in the normal group (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 1.

SEM images of normal and DGI-II coronal dentin

A-C: SEM images of the normal dentin surfaces at 500 ×, 2000 ×, and 10,000 × magnifications. D-F: SEM images of the DGI-II dentin surfaces at 500 ×, 2000 ×, and 10,000 × magnifications. G: The quantitative analysis of the area of the dentin tubules at 2000 × magnification of the SEM. H: The quantitative analysis of the number of dentin tubules at 10,000× magnification of the SEM. **** indicates significant difference between groups (p < 0.0001). Scale bars: 20 μm (A and D), 5 μm (B and E), 1 μm (C and F).

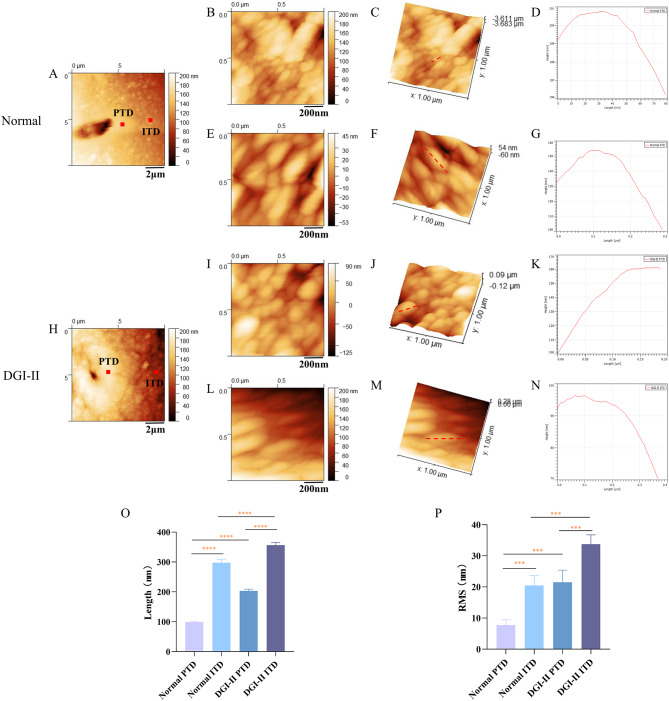

HR-AFM results

In the PTD region of the normal group, apatite crystals with smooth surfaces exhibited a dense, fine-grained structure, whereas apatite crystals in the ITD region appeared as coarse granules (Fig. 2A). However, in the DGI-II group, the tubules were significantly smaller in diameter and the apatite crystals in the ITD region were coarser and had rougher and more uneven surfaces than those in the PTD region (Fig. 2H). The apatite crystals in the PTD region of the normal group were spherical in shape with fine particles (Fig. 2B and C) and a crystal length of approximately 100 nm (Fig. 2D), whereas those in the ITD region were cylindrical with coarse particles (Fig. 2E and F) and a crystal length of approximately 300 nm (Fig. 2G). Despite the normal shape of the apatite particles in the PTD region of the DGI-II group, the size of the particles increased significantly compared to those of the PTDs in the normal group (Fig. 2I and J), with a crystal length of approximately 200 nm (Fig. 2K), whereas the apatite crystals in the ITD region were elongated (Fig. 2L and M), with a crystal length of approximately 380 nm (Fig. 2N).

Fig. 2.

HR-AFM images of the PTD and ITD in normal and DGI-II coronal dentin

Quantitative analysis (Fig. 2O and P) revealed that in the ITD region of the normal group, the HAP size was significantly larger than that of the PTDs (p < 0.0001), and the HAP nano-roughness was noticeably more than that of the PTDs (p < 0.0001). This pattern was also evident in the DGI-II group. However, compared to the normal group, the HAP size and nano-roughness increased in both the PTD and ITD regions of the DGI-II group, with the increase being more pronounced in the PTD region (p < 0.0001).

A and H: The 10 × 10 μm HR-AFM images of the normal and DGI-II coronal dentin. B-D and I-K: Crystal contour mapping, 1 × 1 μm height mapping, and phase diagram of the PTD region in normal and DGI-II groups. E-G and L-N: Crystal contour mapping, 1 × 1 μm height mapping, and phase diagram of the ITD region in normal and DGI-II groups. O and P: The quantitative analysis of the size and nanoroughness of HAP in the PTD and ITD regions of normal and DGI-II groups. *** indicates significant difference between groups (p < 0.001). **** indicates extremely significant difference between groups (p < 0.0001). Scale bars: 2 μm (A and H), 200 nm (B, E, I and L).

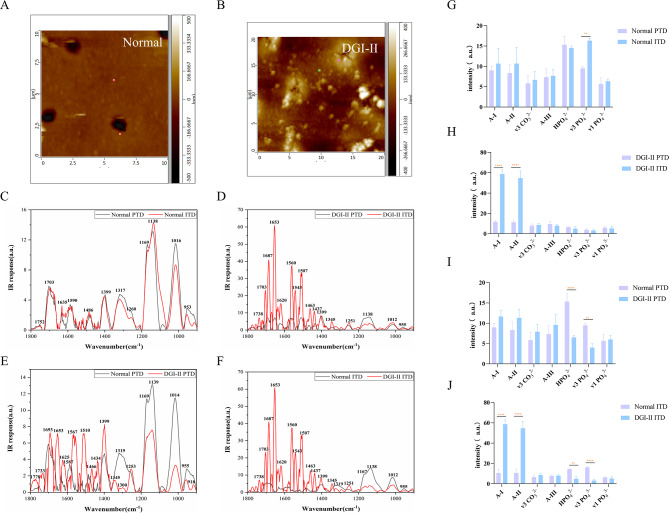

AFM-IR results

As shown in the IR spectrum, apart from a significant difference in the peak intensity of PO43 − v3 (p < 0.01), there was no statistically significant difference between the PTDs and ITDs in the normal dentin in terms of peak intensities of the functional groups (Fig. 3C and G). However, in the DGI-II group, there was a significant difference between PTDs and ITDs in the peak intensities of A-I and A-II (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3D and H). The statistical results suggested that the PO43 − v3 and HPO42− content of the PTDs in the DGI-II group were lower than those in the normal group (p < 0.01), whereas the A-I, A-II, A-III, and CO32 − v3 content did not exhibit any statistically significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 3E and I). A similar pattern was evident when comparing the IR absorption spectra of the ITDs between the normal and DGI-II groups, with the statistical results indicating that the two groups differed primarily in the peak intensities of HPO43−, PO43−v3, A-I, and A-II (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3F and J).

Fig. 3.

AFM-IR spectra of the PTD and ITD in normal and DGI-II coronal dentin

A and B: AFM images of the normal and DGI-II coronal dentin. C: AFM-IR spectra of the PTD and ITD in the normal group. D: AFM-IR spectra of the PTD and ITD in the DGI-II group. E: AFM-IR spectra of the PTD in the normal and DGI-II groups. F: AFM-IR spectra of the ITD in the normal and DGI-II groups. G-J: Quantitative results of the peak intensity of the corresponding functional groups in C-F. ** indicates significant difference between groups (p < 0.01). **** indicates extremely significant difference between groups (p < 0.0001).

Nanoindentation results

Compared with the flattened and smooth PTDs in the normal group (Fig. 4A), the PTDs in the DGI-II group (Fig. 4F) were smaller, and granular apatite crystal structures were evident. Moreover, the tubule diameter of the DGI-II dentin was smaller than that of the normal dentin, but the ITDs in both groups exhibited globular structures. In the Young’s modulus images (Fig. 4B and G), the color scale represents the relative difference in Young’s modulus, differentiating between the PTDs and ITDs. A 4 μm contour line spanning the PTD and ITD regions in Fig. 4B and D was selected for the contour mappings (Fig. 4C and E). It was evident that the Young’s modulus decreased significantly and the indentation depth gradually deepened from the PTD region to the ITD region in the normal dentin. An analogous pattern was evident in the DGI-II group (Fig. 4G and J).

Fig. 4.

Young’s Modulus and nanoindentation mapping of the PTD and ITD in normal and DGI-II coronal dentin

Quantitative analysis (Fig. 4K and L) indicated that the PTDs exhibited a higher Young’s modulus and shallower indentation depth than those of the ITDs in the normal and DGI-II groups (p < 0.05). Moreover, it was evident that whether in the PTD or ITD regions, the Young’s modulus of the DGI-II group was smaller and the indentation depth deeper than those of the normal group (p < 0.05).

A and F: AFM images of the normal and DGI-II coronal dentin. B and G: Young’s modulus mappings of the normal and DGI-II groups. C and H: Contour mappings made by selecting a 4 μm contour line spanning the PTD and ITD regions in B and G. D and I: Nanoindentation mappings of the normal and DGI-II groups. E and J: Contour mappings made by selecting a 4 μm contour line spanning the PTD and ITD regions in D and I. K and L: Quantitative analysis of Young’s modulus and indentation depths of the PTD and ITD in two groups. * indicates significant difference between groups (p < 0.05). ** indicates very significant difference between groups (p < 0.01). Scale bars: 2 μm (A, B, D, F, J and I).

Multiple linear regression analysis

The results (Table 1) revealed that the Young’s modulus—measured using nanoindentation (evaluated by AM-FM)—was associated with the CO32−/PO43− ratio (quantified by AFM-IR), A-I/A-III ratio (determined by AFM-IR), and the HAP size (analyzed by HR-AFM) in both the PTDs and ITDs (p < 0.05), suggesting that changes in the mechanical properties of the DGI-II coronal dentin were related to alterations in its components and structure.

Discussion

DGI-II is an autosomal dominant hereditary disease with severe deficiency in dentin hypomineralization [29]. Owing to the morphological alterations of the DEJ, the enamel can be easily stripped from the tooth surface, resulting in rapid wear of the exposed hypomineralized dentin [30]. From a reverse engineering perspective, the ultimate goal of dental restorative materials is to closely approximate the longevity and performance of natural teeth. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of the pertinent properties of dentin under both normal and pathological conditions is imperative. The investigation into the nanomechanical properties, microstructure, and chemical composition of coronal dentin in DGI-II patients holds major implications for the prevention, treatment, and enhancement of restorative outcomes for this condition. In this study, we found that the nanomechanical properties of PTDs and ITDs in DGI-II dentin deteriorated significantly. These changes could be attributed to modifications in the microstructural and chemical attributes of the dentin.

Dentin contains numerous dentin tubules, and it has been determined that the number and diameter of dentin tubules can influence the dentin hardness. However, this effect can be caused by changes in the microstructure [10]. Dentin possesses a unique hierarchical structure containing two-layered microstructures—that is, ITDs and PTDs—both of which can have a significant effect on the mechanical properties and fracture behavior of dentin [13, 14]. Maghami et al. [31] determined that PTDs enhanced the dentin resistance to crack growth, whereas ITDs increased the dentin toughness. Rong et al. [32] demonstrated that PTDs played a crucial role in reinforcing the overall stiffness of dentin. Moreover, there were distinct differences in the mechanical properties of the PTDs and ITDs in normal dentin. Ziskind et al. [33] observed a gradual reduction in Young’s modulus from values as high as 40–42 GPa within the PTD region, to values of 17 GPa within the ITD region. Consequently, we can conclude that the Young’s modulus of the PTDs in normal dentin is higher than that of the ITDs. The results of AM-FM testing in this study showed that in both the normal and DGI-II groups, the Young’s modulus of the PTDs in coronal dentin was significantly higher than that of the ITDs, with the indentation depth being shallower than that of the ITDs (Fig. 4K and L), consistent with the results of earlier research [34]. Compared to the normal group, the DGI-II group exhibited a reduced Young’s modulus in both the PTDs and ITDs, indicative of decreasing DGI-II dentin stiffness (Fig. 4K). The deeper indentation depths of both the PTDs and ITDs in the DGI-II group than in the normal group, were indicative of decreased hardness (Fig. 4L). The above results collectively indicate a decrease in the nanomechanical properties of coronal dentin in the DGI-II condition, consistent with our previous observations that the nanohardness and elastic modulus of coronal dentin in DGI-II were significantly impaired [4].

Numerous studies have confirmed that the HAP size in the ITD region is larger than that in the PTD region [35, 36] and clarified the difference in mechanical properties between the PTDs and ITDs from a crystal-structure perspective. Sui et al. [24] discovered that the mean crystallite size of ITDs (32 ± 8 nm) was larger than that in PTDs (22 ± 3 nm). The finer-grained and more highly mineralized structure of PTDs accounts for its higher Young’s modulus and mean hardness compared with those of ITDs [33]. The HR-AFM images showed that in the PTD region of both the normal (Fig. 2B and E) and DGI-II (Fig. 2I and L) groups, the apatite crystals with a smooth surface exhibited a dense, fine-grained structure, whereas the apatite crystals in the ITD region appeared as coarse granules. Additionally, the HAP size in the ITD region was larger than that in the PTD region (Fig. 2O), which was consistent with previous results [35, 36]. Analysis demonstrated an increase in the crystal particle size and nanoscale roughness of the PTDs and ITDs in DGI-II dentin, especially in the PTDs (Fig. 2O and P). This result suggests that the increase in HAP size of the DGI-II coronal dentin could be one of the reasons for the decrease in its mechanical properties.

Dentin is a biocomposite comprising both organic and inorganic components. The inorganic composition enhances the elastic modulus and hardness of dentin [37, 38], whereas the mineralization of the organic component, collagen fibers, plays an important role in ensuring the mechanical properties of dentin [39–41]. However, the organic and mineral content of the PTDs and ITDs are not identical [42, 43]. Xu et al. [44] discovered that the mineral-to-matrix ratios in PTDs were three times higher than those in ITDs. Based on the AFM-IR results (Fig. 3C and G), we can conclude that the PTDs in normal dentin contained more minerals (e.g., PO43−v3), whereas the ITDs contained more organic matter (e.g., A- I, A-II, and A-III), which was consistent with previous findings. The same phenomenon was also evident in the DGI-II group (Fig. 3D and H). The statistical results indicated a reduction in mineral content (e.g., PO43−v3 and HPO42−), but no significant change in organic matter content (e.g., A-I, A-II, A-III, and CO32 − v3) in the PTD region of DGI-II dentin compared to the normal group (Fig. 3I). Additionally, the analysis revealed a decrease in mineral content (e.g., PO43−v3 and HPO42−) and an increase in organic matter content (e.g., A-I and A-III) in the ITD region of DGI-II dentin compared to the normal group (Fig. 3J). These findings imply that the altered chemical composition of the DGI-II coronal dentin could affect its mechanical properties.

In summary, this study revealed differences in the nanomechanical properties, microstructure, and composition of PTDs and ITDs between normal and DGI-II coronal dentin and clarified their correlations. These findings could serve as an impetus for developing novel bonding and restorative materials tailored to the unique characteristics of DGI-II dentin. From a clinical perspective, selecting restorative materials with mechanical properties matching those of dentin is critical to minimizing stress concentrations [45]. Notably, the size of intrafibrillar minerals plays a pivotal role in dentin adhesion, as it affects the space available for adhesive monomer penetration into demineralized collagen fibrils [46]. Additionally, the organic and inorganic composition of dentin govern the adhesive interface quality between the tooth and the restorative materials [47].

However, this study had some limitations. In terms of sample selection, although factors such as age and sex were matched as much as possible between the two groups, there were still certain individual differences. For example, an individual’s dietary habits can influence dentin formation and mineralization [48]. Theoretically, the control-group sample should be selected from healthy individuals in the patient’s family who are matched for age and sex; however, in practice, it can be difficult to obtain an exact match. Moreover, further in-depth research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which DGI-II affects the dentin composition and structure.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that the PTD and ITD of DGI-II exhibited a larger HAP size compared to that of the normal dentin. Notably, the PTD exhibited decreased mineral content accompanied by increased organic content, whereas the ITD exhibited reduced mineralization without significant changes in organic components. Importantly, these microstructural and compositional alterations were strongly correlated with the impaired nanomechanical properties evident in the DGI-II dentin.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following grants: Wenzhou Science and Technology Bureau Public Welfare Social Development (Medical and Health) Science and Technology Project (grant no. ZY2021015). Medical Health Science and Technology Major Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (grant no. WKJ-ZJ-2311), Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82270991), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China/Outstanding Youth Science Foundation (grant no. LR21H140002).

Abbreviations

- AFM-IR

Atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy

- AM-FM

Amplitude modulation-frequency modulation

- A-I

Amide I; A-II: amide II

- DGI

Dentinogenesis imperfect

- DGI-II

Dentinogenesis imperfecta type II

- HAP

Hydroxyapatite

- HR-AFM

High-resolution atomic force microscopy

- ITD

Intertubular dentin

- MLR

Multiple linear regression

- PTD

Peritubular dentin

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

Author contributions

G.J., J.T. and J.H. contributed to data acquisition and analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; C.W., T.J., Y.M., M.Y. and C.Y. contributed to data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; W.X. and C.S. contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; H.S. contributed to conception, design, data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: Wenzhou Science and Technology Bureau Public Welfare Social Development (Medical and Health) Science and Technology Project (grant no. ZY2021015). Medical Health Science and Technology Major Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (grant no. WKJ-ZJ-2311), Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82270991), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China/Outstanding Youth Science Foundation (grant no. LR21H140002).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with the approval of the Wenzhou Medical University Ethics Committee (WYKQ2023006). Written informed consents were obtained from all the study participants. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Gao Jia, Jiang Tianle, and Jiang Haofu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Wang Xia, Email: xiawang1216@163.com.

Chen Shuomin, Email: csm168168@Outlook.com.

Huang Shengbin, Email: huangsb003@wmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Kim J-W, Simmer JP. Hereditary dentin defects. J Dent Res. 2007;86:392–9. 10.1177/154405910708600502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields ED, Bixler D, el-Kafrawy AM. A proposed classification for heritable human dentine defects with a description of a new entity. Arch Oral Biol. 1973;18:543–53. 10.1016/0003-9969(73)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barron MJ, McDonnell ST, Mackie I, Dixon MJ. Hereditary dentine disorders: dentinogenesis imperfecta and dentine dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:31. 10.1186/1750-1172-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao J, Wang L, Jiang Y, et al. Nanoscopic wear behavior of dentinogenesis imperfecta type II tooth dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;120:104585. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Zhao J, Li C, et al. DSPP mutation in dentinogenesis imperfecta shields type II. Nat Genet. 2001;27:151–2. 10.1038/84765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai H, Agula H, Wu Q, et al. A novel DSPP mutation causes dentinogenesis imperfecta type II in a large Mongolian family. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:23. 10.1186/1471-2350-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taleb K, Lauridsen E, Daugaard-Jensen J, et al. Dentinogenesis imperfecta type II- genotype and phenotype analyses in three Danish families. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2018;6:339–49. 10.1002/mgg3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryou H, Amin N, Ross A, et al. Contributions of microstructure and chemical composition to the mechanical properties of dentin. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22:1127–35. 10.1007/s10856-011-4293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park H, Hyun H-K, Woo KM, Kim J-W. Physicochemical properties of dentinogenesis imperfecta with a known DSPP mutation. Arch Oral Biol. 2020;117:104815. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall GW Jr, Marshall SJ, Kinney JH, Balooch M. The dentin substrate: structure and properties related to bonding. J Dent. 1997;25:441–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stock SR, Deymier-Black AC, Veis A, et al. Bovine and equine peritubular and intertubular dentin. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:3969–77. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Wu R, Shen L, et al. The multi-scale meso-mechanics model of viscoelastic dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2022;136:105525. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2022.105525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An B, Wagner HD. Role of microstructure on fracture of dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2016;59:527–37. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, Sui T. Insights into the reinforcement role of peritubular dentine subjected to acid dissolution. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;103:103614. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2019.103614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortiz-Ruiz AJ, Teruel-Fernández J, de D, Alcolea-Rubio LA, et al. Structural differences in enamel and dentin in human, bovine, porcine, and ovine teeth. Ann Anat. 2018;218:7–17. 10.1016/j.aanat.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaslansky P, Friesem AA, Weiner S. Structure and mechanical properties of the soft zone separating bulk dentin and enamel in crowns of human teeth: insight into tooth function. J Struct Biol. 2006;153:188–99. 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S, Arola D, Ricucci D, et al. Biomechanical perspectives on dentine cracks and fractures: implications in their clinical management. J Dent. 2023;130:104424. 10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vennat E, Hemmati A, Schmitt N, Aubry D. The role of lateral branches on effective stiffness and local overstresses in dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;116:104329. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu J, Chen Y, Zhou M, et al. Effects of cryopreservation on the Biomechanical properties of dentin in cryopreserved teeth: an in-vitro study. Cryobiology. 2023;111:96–103. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2023.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forien J-B, Fleck C, Cloetens P, et al. Compressive residual strains in mineral nanoparticles as a possible origin of enhanced crack resistance in human tooth dentin. Nano Lett. 2015;15:3729–34. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanette I, Enders B, Dierolf M, et al. Ptychographic X-ray nanotomography quantifies mineral distributions in human dentine. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9210. 10.1038/srep09210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang L, Zhang X, Shao J, et al. Nanoscale chemical and mechanical heterogeneity of human dentin characterized by AFM-IR and bimodal AFM. J Adv Res. 2019;22:163–71. 10.1016/j.jare.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun X, Ban J, Sha X, Wang W, Jiao Y, Wang W, et al. Effect of er,cr:ysgg laser at different output powers on the micromorphology and the bond property of Non-Carious sclerotic dentin to resin composites. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0142311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sui T, Dluhoš J, Li T, et al. Structure-Function correlative microscopy of peritubular and intertubular dentine. Mater (Basel). 2018;11:1493. 10.3390/ma11091493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarialioglu Gungor A, Donmez N. Dentin erosion preventive effects of various plant extracts: an in vitro atomic force microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and nanoindentation study. Microsc Res Tech. 2021;84:1042–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zurick KM, Qin C, Bernards MT. Mineralization induction effects of osteopontin, bone sialoprotein, and dentin phosphoprotein on a biomimetic collagen substrate. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101:1571–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tesch W, Eidelman N, Roschger P, Goldenberg F, Klaushofer K, Fratzl P. Graded microstructure and mechanical properties of human crown dentin. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abu Zeid ST, Alamoudi RA, Abou Neel EA, Mokeem Saleh AA. Morphological and spectroscopic study of an apatite layer induced by Fast-Set versus Regular-Set endosequence root repair materials. Mater (Basel). 2019;12:3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacDougall M, Dong J, Acevedo AC. Molecular basis of human dentin diseases. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:2536–46. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de La Dure-Molla M, Philippe Fournier B, Berdal A. Isolated dentinogenesis imperfecta and dentin dysplasia: revision of the classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:445–51. 10.1038/ejhg.2014.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maghami E, Pejman R, Najafi AR. Fracture micromechanics of human dentin: A microscale numerical model. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;114:104171. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.104171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R, Niu L, Li Q, et al. The peritubular reinforcement effect of porous dentine microstructure. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0183982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziskind D, Hasday M, Cohen SR, Wagner HD. Young’s modulus of peritubular and intertubular human dentin by nano-indentation tests. J Struct Biol. 2011;174:23–30. 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinney JH, Balooch M, Marshall SJ, et al. Atomic force microscope measurements of the hardness and elasticity of peritubular and intertubular human dentin. J Biomech Eng. 1996;118:133–5. 10.1115/1.2795939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Wang J, Sun J, et al. Hierarchical structure and mechanical properties of remineralized dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2014;40:297–306. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinney JH, Pople JA, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ. Collagen orientation and crystallite size in human dentin: a small angle X-ray scattering study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:31–7. 10.1007/s00223-001-0006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abou Neel EA, Aljabo A, Strange A, et al. Demineralization-remineralization dynamics in teeth and bone. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:4743–63. 10.2147/IJN.S107624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sui T, Sandholzer MA, Baimpas N, et al. Multiscale modelling and diffraction-based characterization of elastic behaviour of human dentine. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:7937–47. 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu L, Wei M. Biomineralization of Collagen-Based materials for hard tissue repair. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:944. 10.3390/ijms22020944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samiei M, Alipour M, Khezri K, et al. Application of collagen and mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative dentistry. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;17:606–20. 10.2174/1574888X17666211220100521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen C, Mao C, Sun J, et al. Glutaraldehyde-induced remineralization improves the mechanical properties and biostability of dentin collagen. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016;67:657–65. 10.1016/j.msec.2016.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberg M, Kulkarni AB, Young M, Boskey A. Dentin: structure, composition and mineralization. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2011;3:711–35. 10.2741/e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leung N, Harper RA, Zhu B, et al. 4D microstructural changes in dentinal tubules during acid demineralisation. Dent Mater. 2021;37:1714–23. 10.1016/j.dental.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu C, Wang Y. Chemical composition and structure of peritubular and intertubular human dentine revisited. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:383–91. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dietschi D, Duc O, Krejci I, Sadan A. Biomechanical considerations for the restoration of endodontically treated teeth: a systematic review of the literature–Part 1. Composition and micro- and macrostructure alterations. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:733–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakabayashi N, Nakamura M, Yasuda N. Hybrid layer as a dentin-bonding mechanism. J Esthet Dent. 1991;3:133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matos AB, Trevelin LT, Silva BTFda, Francisconi-Dos-Rios LF, Siriani LK, Cardoso MV. Bonding efficiency and durability: current possibilities. Braz Oral Res. 2017;31(suppl 1):e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye X, Zhang J, Yang P. Hyperlipidemia induced by high-fat diet enhances dentin formation and delays dentin mineralization in mouse incisor. J Mol Histol. 2016;47:467–74. 10.1007/s10735-016-9691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.