Abstract

Background

The C797S mutation is one of the most common mechanisms of acquired resistance to third generation EGFR TKIs, yet no approved therapies have been available to target it. Here we developed a novel selective EGFR C797S inhibitor, HS-10375, and report the results of pre-clinical research and the first-in-human phase 1 trial.

Methods

Ba/F3 cell lines and patient-derived cells expressing mutant EGFR were used to test the selectively inhibitory potency of HS-10375 in vitro, and cell line-derived xenograft animal models were used to evaluate the anticancer efficacy of HS-10375 in vivo. In the phase 1 trial, HS-10375 was administered orally at six dose levels (10–240 mg) daily (QD) in 21-day cycles, following a rule-based, rolling six design. The primary objectives were the safety, tolerability and maximum tolerated dose (MTD). The secondary objectives included PK parameters and anti-tumor activity.

Results

HS-10375 showed more potent activity in inhibiting EGFR phosphorylation compared to 1st to 3rd generation EGFR TKIs in C797S triple-mutant cell lines. HS-10375 also exhibited comparable inhibitory activity to 1st- and 2nd- generation EGFR TKIs and superior activity to 3rd-generation EGFR TKIs in C797S double-mutant cell lines. Furthermore, cells harboring EGFR double or triple C797S mutation underwent remarkable apoptosis upon HS-10375 treatment. HS-10375 effectively inhibited tumor growth in C797S triple-mutant mouse models. In the first-in-human trial, 28 patients with advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancers who harbored EGFR mutation and who had experienced treatment failure with EGFR TKI treatment received at least one dose of HS-10375. Dose-limiting toxicities were observed in 2 patients at 240 mg QD, and MTD was reached at HS-10375 150 mg QD. The most common treatment-related adverse events were vomit (37.0%), loss of appetite (33.3%), and elevated AST (33.3%). One patient with EGFR mutations showed tumor shrinkage after progression on five-line treatment including gefitinib, almonertinib, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and EGFRxHER3 antibody–drug conjugate.

Conclusions

HS-10375 demonstrated potent and mutant-selective activity against the EGFR C797S mutation in preclinical results, and showed an acceptable safety profile and objective response in a first-in-human phase 1 trial.

Trial registration This trial is registered on China Drug Trials (CTR20220045), and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05435248).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-06613-0.

Keywords: EGFR TKI, Non-small cell lung cancer, HS-10375, C797S mutation, Targeted therapy

Background

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80–85% of all lung cancers, and mutations in the kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are its key oncogenic drivers, especially in adenocarcinoma [1–3]. Over the past two decades, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have shown superiority in treating patients with EGFR-positive NSCLC over chemotherapy [4–7]. Third generation EGFR TKIs have even become the preferred standard treatment for advanced EGFR mutant NSCLCs [4, 8–10]. However, acquired resistance inevitably emerges after treatment with 3rd generation EGFR TKIs (3rd EGFR TKIs), which leads to disease progression [11–16]. Thus, prolonging the progression survival of 3rd TKIs or overcoming their acquired resistance is an urgent unmet clinical need.

The predominant resistance mechanism of 3rd generation EGFR TKI osimertinib is a tertiary point mutation at the C797 residue of EGFR [17]. Due to absence of the Cysteine 797, the acrylamide warhead of the 3rd EGFR-TKIs can no longer reacted with thiol group of C797, which disrupts covalent bonding of the EGFR-TKI inhibitor, resulting in disease progression [18, 19]. The C797S mutation accounts for 10% to 26% of 3rd-EGFR-TKI-resistant patients in second-line and 7% in first-line settings [11, 19, 20]. However, after such progression on 3rd EGFR TKIs, no approved targeted therapy is available according to current guidelines [4]. For these patients, turning to chemotherapy contained systemic treatments was the only option.

Fourth-generation EGFR TKIs are emerging as a promising therapeutic strategy to address acquired resistance mechanism of third-generation EGFR TKI, particularly the C797S mutation. BLU-945, has demonstrated preliminary clinical activity in the phase 1/2 SYMPHONY trial (NCT04862780), including tumor regression in patients with C797S-mediated resistance and evidence of central nervous system penetration [21]. Additional candidates, such as BBT-176 and EAI045, have reported partial responses in C797S-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) during phase 1 evaluations [22, 23]. BDTX-1535 is currently the most advanced in clinical development. It has demonstrated preliminary efficacy in a Phase 1 clinical trial (NCT05565422) with objective tumor responses and a manageable safety profile in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, including those resistant to prior EGFR TKI therapy [24, 25]. However, no fourth-generation EGFR-TKI has been clinically approved to date.

Given the high unmet medical need for the next generation of EGFR TKIs, we developed HS-10375. HS-10375 is an orally bioavailable, highly selective, small molecular inhibitor of EGFR C797S mutations. The compound shows excellent pharmacokinetics, good efficacy, and favorable tolerability in pre-clinical animal model studies. In this study, we reported the preclinical findings, clinical safety profile, preliminary anti-tumor activity, and pharmacokinetics of HS-10375 in advanced non–small cell lung cancer patients.

Methods

Cell lines and reagents

All EGFR kinase assays used are described in Additional file 1. Details of the in vitro and in vivo experiments are also presented in Additional file 1.

In vitro EGFR phosphorylation assays and western blot analysis

A LANCE Ultra Phosphorylated EGFR (Y1068) TR-FRET Cellular Detection Kit (PerkinElmer) was used to detect p-EGFR levels. Here, cells were seeded into 384-well culture plates at a certain density and left to grow overnight. The cells then were treated with different concentrations of drugs, and the fluorescence values were detected at 665/620 nm. IC50 values were obtained using GraphPad Prism with log (inhibitor) vs. response-Variable slope (four parameters) settings, and western blots were performed to analyze phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068), EGFR, phospho-AKT (Ser473), AKT, phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204), and ERK.

Cell viability assays and flow cytometry analysis

A431 and Ba/F3 Del19/T790M/C797S cells were treated with serially diluted HS-10375. Cell viability was then measured by CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega), and dose–response curves were generated using GraphPad Prism with log (inhibitor) vs. response-Variable slope (four parameters) settings. Additionally, an Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (#A211-01, Vazyme) was used to investigate cell apoptosis. Next, Ba/F3 cells with EGFR mutations were seeded in a 12-well plate at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well and incubated with gradient concentrations of HS-10375 for 48 h, and H1975-OR and PC-9-OR cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and incubated with gradient concentrations of HS-10375 for 48 h. Flow cytometry analysis was subsequently performed using a BD cytoFLEX flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the data were analyzed using cytoFLEX software.

Xenograft and allograft studies

All procedures in this study related to animal handling, care, and treatment were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) and local IACUC guidelines.

For PC9 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S, Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S, and Ba/F3 EGFR-L858R/T790M/C797S xenograft and allograft models, 0.1 mL cell suspension (containing 2 × 106 cells) were subcutaneously inoculated at the right flank of NOD SCID mice or BALB/c nude mice for tumor development. For the PDX model, the tumors of NSCLC PDX model LD1-0025–200717 were sliced into 3 × 3 × 3 mm (about 45–60 mg) fragments and implanted subcutaneously in the right flank of Nu/Nu mice. When their mean tumor volumes reached 100–300 mm3, all mice were treated with vehicle or HS-10375once daily by oral for the indicated time period. Tumor size was measured twice a week, and the volume was expressed in mm3. Tumor growth inhibition (TGI) was calculated for each group, and body weight was measured twice a week.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics analysis

For pharmacokinetics (PK) analysis, plasma, tumor, and brain tissue samples of Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S xenograft model mice were collected at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after single oral administration of HS-10375 at 20 mg/kg. HS-10375 concentration was analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) at the Shanghai Center for Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics Research. For pharmacodynamics (PD) analysis, 100 mg of tumor tissues were homogenized by Tissuelyser (Qiagen) at 85 Hz for 2 min, and western blotting was performed to analyze the protein expression. The primary antibodies p-EGFR (Tyr1068; #3777S), EGFR (#4267S), and p-ERK1/2 (#4370S) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, and GAPDH (#MA5-15738-A488) was purchased from Thermo Fisher.

First-in-human phase 1 trial

Patients and study design

The first-in-human phase 1 study of HS-10375 was conducted at 4 sites (Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Hunan Cancer Hospital, Henan Cancer Hospital, and the First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Science and Technology) in China. Eligible patients were enrolled according to the following criteria: aged ≥ 18 years with histologically or cytological confirmed locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC and who harbored EGFR mutation (detected by PCR of tumor tissue or blood samples on-site or at a central laboratory); and radiologically confirmed disease progression after EGFR TKI with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1 and adequate organ functions. Patients who had received prior treatment with other 4th EGFR TKIs were excluded.

Dose-escalation followed per a rule-based rolling six design. Patients received HS-10375 orally after a 7-day washout period and then continuously at the same dose daily in 21-day cycles. The dose limiting toxicity (DLT) period lasted for 28 days, spanning from the single dosing to the end of Cycle 1 of repeated dosing. DLT is defined as any toxicity, judged by the investigator to be related to HS-10375, and meets the following criteria during the dose escalation phase: (1) grade ≥ 3 febrile neutropenia; (2) grade 4 decreased neutrophil lasting for > 3 days; (3) grade ≥ 3 decreased neutrophil with infection; (4) grade 4 decreased platelet; (6) grade ≥ 3 decreased platelet with hemorrhage (grade ≥ 2 hemorrhage); (5) grade 3 decreased platelet (lasting for ≥ 7 days without hemorrhage); (6) grade ≥ 4 anemia; (7) Any non-hematological toxicities of grade ≥ 3, with the exception of alopecia, grade 3 fatigue lasting < 7 days, and grade 3 events including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, decreased appetite, or mucositis, as well as grade ≥ 3 electrolyte disturbances or laboratory abnormalities; (8) adverse events leading to dose interruption for more than 14 days without recovery. During the dose-escalation phase, 10 mg once daily (QD) of HS-10375 was the starting dose as determined by preclinical study evidence, and the subsequent dose levels were 30 mg QD, 60 mg QD, 90 mg QD, 150 mg QD, and 240 mg QD. Intrapatient dose-escalation was not allowed, and a safety review was conducted to evaluate safety parameters, such as adverse events, DLTs, tolerability, and available PK/PD data to decide on the next dose schedule prior to all next dose level recruitment. Patients could be discontinued from treatment due to disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent.

The primary objectives were the safety, tolerability and maximum tolerated dose (MTD). The secondary objectives included PK parameters and anti-tumor activity. Safety endpoints consisted of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), and efficacy endpoints included objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR).

The study protocol, amendments, and informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards/independent ethics committees at all sites. All patients provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the International Council for Harmonization and the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Safety was monitored by the safety review committee (SRC), which comprised investigators and sponsor representatives.

This study was registered on the official site of China National Medical Products Administration http://www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn/index.html, Registration Number: CTR20220045, Date of Registration: 2022.01.10; and registered on clinicaltrials.gov; Registration number: NCT05435248; Date of registration: 2022.06.23.

Safety and efficacy assessments

Evaluation of safety was based primarily on the incidence, severity, and type of adverse events (AEs). AEs were graded 1 to 5 according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE 5.0) and monitored from treatment initiation up to 28 days after the last dose. During HS-10375 treatment, patients with unresolved adverse reactions were permitted to receive symptomatic treatment and follow-up after their reactions returned to grade 1 or less. Safety laboratory assessments were conducted at local laboratories according to the visit schedules.

Efficacy was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors Version 1.1 (RECIST V1.1). Tumors were assessed at baseline and every two treatment cycles, including tumor-related symptoms and physical and imaging examination (CT or MRI) of superficial lesions. Additional CT or MRI scans could be performed on suspicious lesions as determined by investigators. As specified in RECIST V1.1, confirmations confirmation of initial evaluations indicating partial response (PR) was required to be performed after a 4-week interval, and stable disease (SD) needed to persist for at least 5 weeks in order to be confirmed. Additional CT or MRI scans were permitted for suspicious lesions at the discretion of the investigators as well. ORR was estimated from the proportion of patients with the best overall response of confirmed complete response (CR) or confirmed partial response (PR).

Pharmacokinetic assessments

On day 1 intensive PK samples were taken at pre-dose and 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h post-dose (cycle 0). After 21-day continuous dosing during cycle 1, on day 28 (cycle 2), pre-dose and 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 24 post-dose PK samples were collected. A standard noncompartmental approach was used to generate the PK parameters of HS-10375, including area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to reach Cmax (Tmax), accumulation ratio (Rac, AUC cycle2 day1 /AUCsingle dose, day 1), elimination half-life (t1/2), and AUC0-t (area under the concentration–time curve from time 0 to the last measurable concentration). AUCs were calculated using the linear up and log down rule.

Statistical analysis

In this study the safety set (SS) was defined as all enrolled patients who took at least one dose of HS-10375, and the efficacy evaluation set (EES) was defined as all enrolled patients who took at least one dose of HS-10375 and received at least one post baseline investigator assessment. Safety and PK data were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods. Estimates of ORR, DCR and corresponding 95% Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals (CIs) based on the investigator-assessments were calculated. Additionally, survival outcomes, including progression-free survival (PFS) and duration of response (DoR), were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier method, and the median PFS, median DoR together with their corresponding 95% CIs were computed at months 6,9, and were given. All statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Preclinical study results

HS-10375 exhibits binding affinity toward the ATP-binding site of EGFR T790M/C797S.

The chemical structure of HS-10375 is visualized in Fig. 1A, which also shows how HS-10375 binds to the ATP-binding site of EGFR L858R/T790M/C797S. Here, the dimethylphosphine oxide makes a hydrogen bond with Lys745, the pyrimidine and followed amino form hydrogen bonds with Met793 in the hinge region, and the bromine in pyrimidine forms hydrophobic interaction with Met790. Furthermore, the substituted benzene ring forms multiple hydrophobic interactions with surrounding residues, and the 3-(methoxymethyl) azetidine moiety forms salt bridges with Glu804 and Asp800 and hydrogen bond with Arg803. As the figure shows, HS-10375 binds deeply in the ATP-binding pocket and interacts with Met790 and Lys745, which may contribute to its high potency against EGFR. Moreover, T790M is absent from EGFR-WT, so the interaction between HS-10375 and Met790 further contributes to its selectivity over EGFR-WT. Although HS-10375 does not directly interact with Ser797, Ser797 can form a hydrogen bond with Asp800, so the salt bridge between HS-10375 and Asp800 might also be beneficial for the activity and selectivity of HS-10375.

Fig. 1.

The inhibitory activity of HS-10375 against EGFR C797S in vitro. A The chemical structure of HS-10375 and its interaction model binding to EGFR L858R/T790M/C797S. B, C The kinase inhibitory activity of HS-10375 against EGFR WT and EGFR C797S (Del19/T790M/C797S, L858R/T790M/C797S, Del19/C797S, and L858R/C797S), as well as other EGFR mutations (Del19, T790M, L858R, L858R/T790M, and Del19/T790M). D Mean IC50 values for HS-10375 and TQB3804 in different EGFR mutations. All values are the average of two or three independent biological replicates. E The anti-proliferation activity of HS-10375 in A431 and Ba/F3 Del19/T790M/C797S cells. F The inhibitory activity of HS-10375 against other tyrosine kinases

HS-10375 is a potent and selective inhibitor of EGFR kinase activity

We evaluated the inhibitory profile of HS-10375 using biochemical kinase assays. At Km ATP concentration, HS-10375 showed potent inhibitory activity against EGFR that harbored C797S mutations (Del19/T790M/C797S, L858R/T790M/C797S, Del19/C797S, and L858R/C797S), and common and/or T790M mutations (Del19, T790M, L858R/T790M, and Del19/T790M) with IC50 < 1.5 nM, which was comparable with a fourth-generation EGFR inhibitor TQB3804 (Fig. 1B–D, and Additional file 3: Fig. S1). A literature-based comparison of inhibitory profiles of HS-10375 and other 4th-generation EGFR TKIs (BBT-176, BLU-945 and EAI045) is listed in Additional file 2: Table S1. Importantly, HS-10375 showed weaker activity against wild type EGFR (Fig. 1B and D). To confirm the WT-sparing activity of HS-10375, cell growth inhibition assays were conducted. Here, HS-10375 showed strong activity against Ba/F3 EGFR Del19/T790M/C797S cells with IC50 of 24.87 nM, but the IC50 of HS-10375 against EGFR-wildtype A431 cells was 148.93 nM, sixfold higher than EGFR Del19/T790M/C797S (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, to evaluate any off-target effects of HS-10375, we also tested it against 29 kinases, and each of these IC50 values are presented in Fig. 1F and Additional file 2: Table S2. Three of them, FAK, FER, and PDGFR-beta, were inhibited, with IC50 values of 0.51, 1.3, and 1.3 nM, respectively. Taken together, HS-10375 displayed potent kinase inhibitory activity that was primarily restricted to EGFR mutant proteins, with limited off-target activity against the rest of the kinome.

HS-10375 inhibits EGFR signaling in C797S mutant and osimertinib-resistant cell lines

To evaluate the effect of HS-10375 on EGFR signaling, we conducted TR-FRET assays. HS-10375 potently inhibited EGFR Del19/T790M/C797S phosphorylation with an IC50 of 24 nM, at least 139 times more potently than gefitinib, afatinib, or osimertinib (IC50 > 10 μM, 3.35 μM, and > 10 μM, respectively) (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the activity of HS-10375 against C797S and other classes of mutants was also assessed in Ba/F3 cells with different EGFR mutants. Among Ba/F3 EGFR-L858R, L858R/C797S, L858R/T790M/C797S, Del19/C797S, and Del19/T790M/C797S, HS-10375 robustly inhibited EGFR signaling and phosphorylated EGFR (p-EGFR) at concentrations of 100 nmol/L and 1,000 nmol/L (Fig. 2B–F), which showed superior or comparable inhibition activity compared to 1st-, 2nd-, and 3rd-− generation EGFR TKIs. In PC9-OR (osimertinib-resistant) and NCI-H1975-OR C797S mutant cell lines, HS-10375 also exhibited superior p-EGFR inhibition activity compared to osimertinib (Fig. 2G). Furthermore, it showed a superior ability to induce apoptosis compared to osimertinib in BaF3 and PC9 cells with EGFR triple- or double-C797S mutation (Fig. 2H and Additional file 3: Fig. S2). Overall, HS-10375 displayed potent p-EGFR inhibition and induced remarkable apoptosis against EGFR that harbored C797S.

Fig. 2.

The effects of HS-10375 on EGFR phosphorylation in vitro. A The cellular p-EGFR inhibition activity of HS-10375 and other EGFR TKIs. B–G Representative western blots comparing inhibition of EGFR-mediated signaling in Ba/F3 cells with different EGFR mutants by erlotinib, afatinib, osimertinib, and HS-10375. OR: osimertinib resistance. H Flow cytometry analysis of HS-10375 and osimertinib-induced apoptosis percentage in BaF3 EGFR-L858R/C797S, Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S, and PC9 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S cells

HS-10375 showed dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth and was well tolerated in EGFR C797S-muntant preclinical animal models

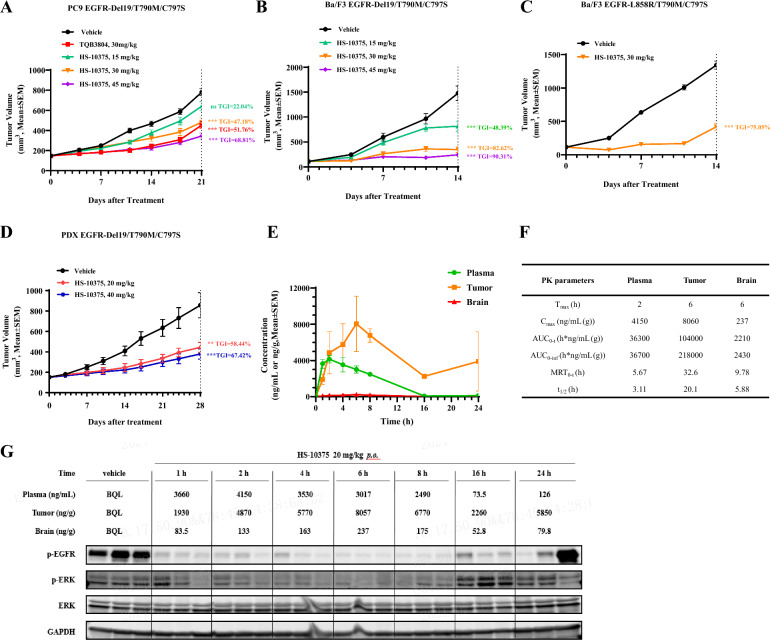

To explore the in vivo activity of HS-10375, we tested HS-10375 in mice bearing PC9 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S, Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S, and Ba/F3 EGFR L858R/T790M/C797S xenografts or allografts. Once-daily oral dosing of HS-10375 showed dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth (Fig. 3A–C) and was well tolerated (Additional file 3: Fig. S3A–C). Meanwhile, HS-10375 exhibited comparable tumor growth inhibition with TQB3804 in PC9 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S xenograft model (Fig. 3A). In the LD1-0025–200717 EGFR 19Del/T790M/C797S PDX model, HS-10375 also demonstrated antitumor efficacy (Fig. 3D) and did not cause body weight loss (Additional file 3: Fig. S3D). We also evaluated the in vivo distribution of HS-10375 in plasma, tumor, and brain tissues from Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S tumor-bearing mice after a single oral administration of 20 mg/kg HS-10375, as well as the inhibitory effect on the level of phosphorylated EGFR (p-EGFR) in tumor tissue. As shown in Fig. 3E–F, HS-10375 demonstrated good pharmacokinetics characteristics. The exposure of HS-10375 in tumor tissues was significantly higher than that in plasma, indicating that HS-10375 was enriched in tumor tissues and exhibited antitumor effects. In addition, HS-10375 also had a certain exposure level in the brain, which accounted for 6.09% of the plasma exposure, though its effect on metastatic encephaloma remains to be further verified. In addition, HS-10375 showed significant inhibition against p-EGFR protein levels and its downstream signaling in tumor tissue at 1–8 h (Fig. 3G). After 16 h, p-EGFR began to recover, but was still lower than vehicle, and this was related to the decrease of HS-10375 concentration observed in the tumor tissue. Taken together, these data indicate that HS-10375 may have efficacious antitumor effects in C797S lung cancer and good PK and PD relationships.

Fig. 3.

The antitumor activity of HS-10375 against EGFR-mutant models in vivo. A Antitumor activity of HS-10375 and TQB3804 in PC9 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S xenograft model. B, C Antitumor activity of HS-10375 in Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S and Ba/F3 EGFR-L858R/T790M/C797S xenograft models. D Antitumor activity of HS-10375 in the PDX model LD1–0025–200717 (EGFR Del19/T790M/C797S). Tumor volume at the endpoint versus vehicle control was performed by two-way ANOVA (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). E Plasma, tumor and brain concentration profiles of HS-10375 in the Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S xenograft model after single oral administration. F PK parameters of HS-10375 in the Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S xenograft model. G Western blot analysis of p-EGFR, p-ERK, and total ERK in the Ba/F3 EGFR-Del19/T790M/C797S xenograft tumors in mice that were dosed with 20 mg/kg of HS-10375

Clinical study findings

Patient demographics

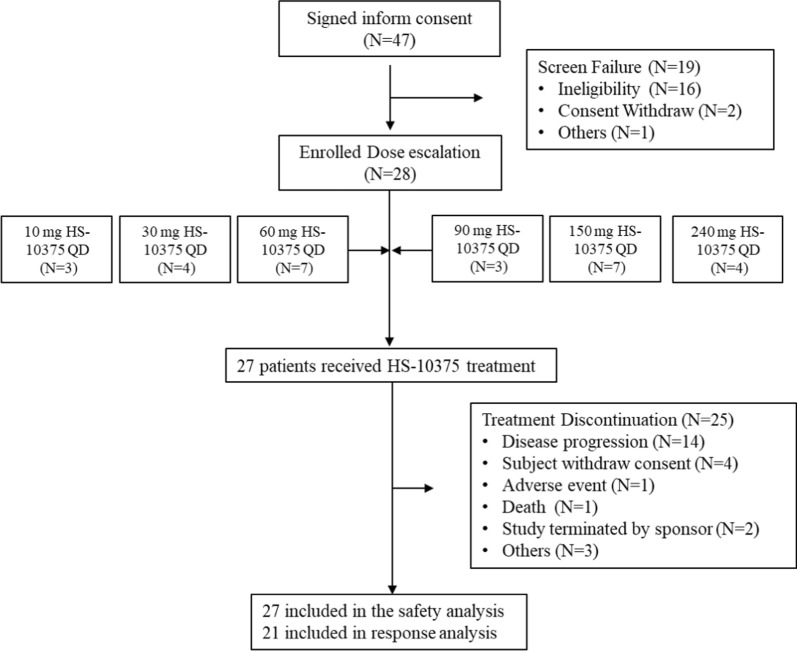

Between February 25, 2022 and the data cutoff date of June 13, 2023, a total of 28 patients were enrolled in a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. At the cutoff date, 27 patients were included in the safety set (SS), and 21 patients were included in the EES (Fig. 4). The demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age of patients in the SS was 57.4 years (range: 41–72), 40.7% patients were female, and more than a third of the patients had a history of smoking (37.0% of patients). All patients were adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations and had disease progression after EGFR-TKI treatment, and one had EGFR C797S mutations (EGFR 19del/T790M/C797S). Before participating in this study, 25.9% (7/27) had received previous immunotherapy, and 48.1% (13/27) had received previous chemotherapy. Central nervous system metastases were present in 48.1% of the cases (13/27) at baseline.

Fig. 4.

Study flowchart

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | 10 mg QD (N = 3) n (%) | 30 mg QD (N = 4) n (%) | 60 mg QD (N = 7) n (%) | 90 mg QD (N = 3) n (%) | 150 mg QD (N = 6) n (%) | 240 mg QD (N = 4) n (%) | Total (N = 27) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 54.0 (49,58) | 56.0 (41,68) | 59.0 (44,69) | 63.0 (49,72) | 55.0 (41,59) | 64.5 (53,67) | 58.0 (41,72) |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Never | 2 (66.7) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (25.0) | 17 (63.0) |

| Former | 1 (33.3) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (75.0) | 10 (37.0) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2 (66.7) | 2 (50.0) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | 16 (59.3) |

| Female | 1 (33.3) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 11 (40.7) |

| Prior Systemic Treatments | |||||||

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | 3 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 27 (100.0) |

| Chemotherapy | 3 (100.0) | 2 (50.0) | 4 (57.1) | 0 | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 13 (48.1) |

| Immunotherapy | 2 (66.7) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 7 (25.9) |

| Others | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) |

| ECOG PS | |||||||

| 0 | 3 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (11.1) |

| 1 | 0 | 4 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 24 (88.9) |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | |||||||

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 3 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 26 (96.3) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) |

| Disease stage at initial diagnosis, n (%) | |||||||

| IVA | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 3 (11.1) |

| IVB | 2 (66.7) | 4 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 2 (66.7) | 6 (100.0) | 3 (75.0) | 24 (88.9) |

| Previous treatment lines | |||||||

| 1 | 0 | 2 (50.0) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 7 (25.9) |

| 2 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | 9 (33.3) |

| ≥ 3 | 3 (100.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 0 | 11 (40.7) |

| Type of EGFR alterations | |||||||

| Ex19del | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 11 (40.7) |

| Ex19del + T790M | 2 (66.7) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 3 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 8 (29.6) |

| L858R | 0 | 0 | 3 (42.9) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 5 (18.5) |

| Ex19del + T790M + C797S | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) |

| L858R + L792V + E709V | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) |

| L858R + T790M + C797G + L718Q | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) |

| Brain metastases, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 1 (33.3) | 2 (50.0) | 6 (85.7) | 0 | 3 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 13 (48.1) |

| No | 2 (66.7) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (100.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | 14 (51.9) |

Safety and the maximum tolerated dose

Among the 27 patients, treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) were observed in 81.5% of patients. The incidence of TRAEs of any grade that occurred in ≥ 10% of patients is summarized in Table 2. The most common adverse-event profiles involved vomiting (37.0%), loss of appetite (33.3%), and increased AST (33.3%). No patient experienced interstitial pneumonitis. Grade ≥ 3 TRAEs were experienced by 6 patients (22.2%; Additional file 2: Table S3), the most frequent of which were weakness (7.4%), diarrhea (3.7%), vomiting (3.7%), hypercalcemia (3.7%), loss of appetite (3.7%), decreased ejection fraction (3.7%), proteinuria (3.7%), pneumonia (3.7%), and hypertension (3.7%) (Table 2). The incidence and grade of gastrointestinal toxicity were both higher in the high-dose group (150 mg QD and 240 mg QD) than in the low-dose group (10–90 mg QD).

Table 2.

Treatment-related AEs that occurred in ≥ 10% of participants

| AE categories | All Grades n (%) | Grade ≥ 3 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Vomit | 10 (37.0) | 1 (3.7) |

| Anorexia | 9 (33.3) | / |

| AST increased | 9 (33.3) | / |

| Nausea | 8 (29.6) | / |

| Diarrhea | 6 (22.2) | 1 (3.7) |

| ALT increased | 6 (22.2) | / |

| Serum creatinine elevated | 6 (22.2) | / |

| Weak | 5 (18.5) | / |

| Urine protein positive | 4 (14.8) | / |

| Weight loss | 4 (14.8) | / |

| ALP increased | 4 (14.8) | / |

| γ-GTT increased | 3 (11.1) | / |

| WBC increased | 3 (11.1) | / |

| LDH increased | 3 (11.1) | / |

| Neutrophil count elevated | 3 (11.1) | / |

| Hypokalemia | 3 (11.1) | / |

| Sensitivity to chills and heat | 3 (11.1) | / |

| Anemia | 3 (11.1) | / |

Treatment-related severe adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 18.5% (5/27) of patients, of which fatigue (7.4%) was the most common. No patients experienced TRAEs that led to dose adjustment, but 3.7% (1 of 27) of the patients experienced TRAEs that led to dose discontinuation, namely fatigue (Grade 2), vomiting (Grade 2), and nausea (Grade 2). At the data cutoff date, no fatal AEs had occurred that was considered to be related to HS-10375 (Additional file 2: Table S3).

Dose-limiting toxicities occurred in two patients at 240 mg QD (grade 3 fatigue and grade 3 lung infections, respectively) and MTD was reached at 150 mg QD.

Efficacy

Twenty-one patients were included in the efficacy evaluation set, and the efficacy assessments are summarized in Additional file 2: Table S4 and Additional file 3: Figs. S4–5. Overall, the percentage of patients with a confirmed objective response was 4.8% (95% CI 0.1 to 23.8), as only one patient had a confirmed partial response. The DCR was 14.3% (95% CI 3.1 to 36.3).

One 58-year-old female patient had been receiving treatment with gefitinib, almonertinib, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and EGFR x HER3 antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma since March, 2019. EGFR 19Del was found at the time of diagnosis, and she was enrolled in the phase 1 trial (dose-escalation phase) and allocated to the HS-10375 150 mg once-daily cohort. After 6 weeks of treatment, CT scans showed shrinkage of the target lesion (inferior lobe of right lung, 39.3% reduction by the short axis diameter as assessed by the investigator) (Fig. 5), and a CT scan at week 12 showed further improvements. The investigator’s evaluation therefore indicated a confirmed partial response after the first follow-up according to RECIST v.1.1 standards.

Fig. 5.

Response to HS-10375 in the patient with C797S mutation during the phase 1 study. Serial CT images at baseline and week 6 revealed significant improvements in the target lesion of the inferior lobe of the right lung

A 53-year-old female patient with stage IV lung adenocarcinoma harboring EGFR 19Del mutation, had been treated with gefitinib and osimertinib since 2019. Despite these treatments, the disease progressed, and additional genetic testing revealed the presence of T790M and C797S mutations. Then she was enrolled in the phase 1 trial (dose-escalation phase) and was allocated to 30 mg QD cohort of HS-10375. These side effects were manageable and did not require dose adjustment or discontinuation of the treatment. Despite the manageable toxicities, the patient reported progressive worsening of chest tightness and dyspnea. A follow-up CT scan confirmed considerable improvement in non-target lesions (left pleural effusion) by RECIST v.1.1 standards.

Pharmacokinetics

All 27 patients had PK samples collected. The mean plasma concentration–time profiles of HS-10375 after single and multiple oral doses of 10–240 mg are shown in Additional file 3: Figs. S6–7. After a single oral administration of 10–240 mg of HS-10375, the absorption was relatively rapid, and the median Tmax of HS-10375 in different dose groups was 1.98–4.01 h (Additional file 2: Tables S5–6)., In the dose range of 30–240 mg, the Cmax, AUClast, and AUC0-∞ of HS-10375 increased with the dosage. The mean t1/2 was 24.26–34.50 h. After multiple administration of 10–150 mg of HS-10375, the mean accumulation ratio of the AUCss and Cmax were approximately 2.1–4.7 and 1.7–4.1, respectively. The Cmax_ss, and AUCss exposure flattened with increasing doses between 60-150 mg.

Discussion

Osimertinib and other 3rd-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor has currently approved as standard therapy for NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations, however acquired resistance mechanisms has limited their clinical effectiveness. EGFR C797S mutation accounts for 7–26% of cases in patients resistance to first-, second-line osimertinib treatment [11]. Currently, no EGFR C797S inhibitors have been approved and treatment options for patients with this mutation are limited, which highlights the urgent need for the development. Here, we report the preclinical characterization of HS-10375, a novel selective EGFR C797S tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and the results of a phase 1 clinical trial in patients with advanced NSCLC.

HS-10375 is a novel 4th-generation EGFR TKI binds to the ATP-binding site of EGFR L858R/T790M/C797S, demonstrated mutant-selective activity against the EGFR C797S mutation in preclinical studies. In vitro models, HS-10375 exhibits potent inhibitory activity against EGFR C797S-containing triple or double mutants. HS-10375 further demonstrated efficacy in various in vivo cell-derived xenografts and PDX models harboring 19Del/T790M/C797S and L858R/T790M/C797S mutations. Preclinical results suggest that HS-10375 showed dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth and was well tolerated in EGFR C797S-muntant preclinical models. HS-10375 exhibited a distinct mechanism of action by inhibiting EGFR phosphorylation, demonstrated superior phosphorylation inhibition in cells that harbored the C797S mutation. This mechanism not only supports the clinical efficacy of HS-10375 but also provides a theoretical foundation for its continued development.

Within this phase 1 study, HS-10375 exhibited a manageable safety profile at various dose levels. The spectrum of adverse events mainly included gastrointestinal toxicity, such as increased alanine aminotransferase, similar to the toxicity of current therapies and other 4th-generation EGFR TKIs which are still in the clinical trial [21, 22, 26]. Two DLTs were observed in the trial at the 240 mg QD dose. Although some patients experienced grade ≥ 3 TRAEs, these were manageable with standard clinical practices. HS-10375 has not shown ≥ 3 liver toxicity in clinical data, which was superior to certain 4th EGFR TKIs [26]. We also observed some treatment responses in a small number of patients. As the number of patients was limited, RP2D was undefined.

At present, a number of new options are being evaluated to overcome acquired resistance to 3rd EGFR TKIs, such as novel drugs targeting EGFR, targeted drug combinations, chemotherapy combined with anti-angiogenic drugs, and novel antibody drug conjugates. Chemotherapy-based combination therapy and novel antibody drug conjugates have achieved good results, however, chemotherapy toxicities such as myelosuppression were inevitable [27–29]. For example, in Orient-031 trial, PD-1 antibody combined with chemotherapy has been found to improve the tumor response significantly, although it comes with significant side effects that are intolerable [27]. Another form of exploration is antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) treatment, such as U3-1402 and BL-B01D1 [28, 29]. These drugs are characterized by high response rates but again also significant side effects. Oral C797S inhibitors, such as HS-10375, might offer potential treatment options for patients who were resistant to third-generation EGFR-TKIs, with reduced side effects and increased ease of administration.

This study is also with its limitations. First, the sample size of this phase 1 single arm study was comparatively small. Besides, due to the C797S mutation typically emerging after resistance to osimertinib, and the fact that repeated tumor biopsies as well as plasma genotyping at the time of progression on osimertinib are not common practice, selection of patients with the C797S mutation is challenging. Indeed, this study documented a single case with the C797S mutation, while no significant clinical responses were observed. The limited clinical dataset underscores for further investigation into the efficacy of HS-10375 in this molecularly defined population.

Secondly, data for biomarkers such as ctDNA analyses (liquid biopsy) are lacking. The different clinical performance of pharmaceutical products may be influenced by multiple factors, including drug structure, the genotypic profile of enrolled patient populations, prior lines of therapy received and so on. The mechanisms of resistance to third-generation EGFR TKIs can be broadly categorized as on-target and off-target mechanisms, depending on whether they involve activation of EGFR-dependent or EGFR-independent pathways, respectively [30]. Regarding HS-10375, we hypothesize that the primary contributing factor might be the absence of systematic screening coexisting driver genetic alterations beyond EGFR during the dose-escalation phase. The genetic landscape of populations resistant to third-generation EGFR TKIs is notably complex, with concurrent resistance-associated genetic alterations potentially impacting therapeutic efficacy [31]. This observation aligns with emerging evidence from other investigational agents in this class, such as BBT-176 [22]. Systematic screening for these additional genetic alterations could provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of resistance and help optimize the clinical development of HS-10375. Recent studies on 4th EGFR TKIs, such as BDTX-1535, have actively investigated the correlation between circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) dynamics and therapeutic efficacy [25]. Unfortunately, such screening was not included in our trial design. Future research should therefore focus on larger-scale clinical trials and more exploratory biomarker researches.

Conclusions

Preliminary observations from our investigation suggest tolerable safety characteristics and early signs of therapeutic activity with HS-10375. Future research should focus on investigating the potential of HS-10375 in combination with other treatments to overcome resistance to EGFR TKIs, an area that warrants further exploration.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients and their care givers who participated in this clinical trial.

Abbreviations

- ADC

Antibody–drug conjugate

- AE

Adverse event

- AKT

Protein kinase B

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- AUC

Area under the plasma concentration–time curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- Cmax

Maximum plasma concentration

- CR

Complete response

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTCAE

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- DCR

Disease control rate

- DLT

Dose-limiting toxicity

- DoR

Duration of response

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EES

Efficacy evaluation set

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- IC50

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- MAD

Maximum applicable dose

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MTD

Maximum tolerated dose

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ORR

Objective response rate

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PD

Pharmacodynamics

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PK

Pharmacokinetics

- PR

Partial response

- PS

Performance status

- QD

Once daily

- Rac

Accumulation ratio

- RECIST

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- SAE

Severe adverse event

- SRC

Safety review committee

- SS

Safety set

- t1/2

Elimination half-life

- TEAE

Treatment-emergent adverse event

- TKI

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- Tmax

Time to reach Cmax

- TRAE

Treatment-related adverse event

- WT

Wildtype

Author contributions

Conceptualization, P.G., H.Z. and L.Z.; methodology, H.Z. and L.Z.; formal analysis, Z.C. and B.S.; investigation, J.Z., J.X., L.W., Z.Z., Q.W., Y.M., Y.H., Y. Y, Y. Zhao, W.F., Y. Zhang, Q.L., D.S., X.S. and P.G.; writing – original draft, J.Z., Y.M., W.X., Y.Y., D.S., X.S. and P.G.; writing – review & editing, all authors; supervision, H.Z. and L.Z.

Funding

This work was supported by Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD0519700), National Natural Science Funds of China (82241232, 82272789, 82473346), Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (202206010141), Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau Basic and Applied Basic Research Project (SL2022A04J01033), and Young Talents program of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (YTP-SYSUCC-0094).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This clinical trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (A2021-184–01). Informed consent was provided by all recruited subjects prior to the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of individual data was obtained from all patients.

Competing interests

W.X., Yan Yang, Z.C., B.S., D.S., X.S. and P.G. are the employees of Hansoh Pharmaceutical Group Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China. Other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jianhua Zhan, Jinhui Xue, Lin Wu, Zhiye Zhang and Qiming Wang have contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Hongyun Zhao, Email: zhaohy@sysucc.org.cn.

Li Zhang, Email: zhangli@sysucc.org.cn.

References

- 1.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553(7689):446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung cancer 2020: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(1):1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mithoowani H, Febbraro M. Non-small-cell lung cancer in 2022: a review for general practitioners in oncology. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(3):1828–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoneda K, Imanishi N, Ichiki Y, Tanaka F. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR-mutations. J uoeh. 2019;41(2):153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan I, Planchard D. Osimertinib in the treatment of patients with epidermal growth factor receptor T790M mutation-positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: clinical trial evidence and experience. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(6):549–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Marti A, Navarro A, Felip E. Epidermal growth factor receptor first generation tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(Suppl 3):S235–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu K, Xie F, Wang F, Fu L. Therapeutic strategies for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients with osimertinib resistance. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304(5676):1497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, Eberlein C, Nebhan CA, Spitzler PJ, et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(9):1046–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonetti A, Sharma S, Minari R, Perego P, Giovannetti E, Tiseo M. Resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(9):725–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu SG, Shih JY. Management of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI-targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CK, Kim S, Lee JS, Lee JE, Kim SM, Yang IS, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals novel resistance mechanisms and molecular heterogeneity in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer with acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs. Lung Cancer. 2017;113:106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertoli E, De Carlo E, Del Conte A, Stanzione B, Revelant A, Fassetta K, et al. Acquired resistance to osimertinib in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer: how do we overcome it? Int J Mol Sci. 2022. 10.3390/ijms23136936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(75):75–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kontos F, Michelakos T, Kurokawa T, Sadagopan A, Schwab JH, Ferrone CR, et al. B7–H3: an attractive target for antibody-based immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(5):1227–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao HY, Xi XX, Xin M, Zhang SQ. Overcoming C797S mutation: the challenges and prospects of the fourth-generation EGFR-TKIs. Bioorg Chem. 2022;128:106057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang H, Wu Y, Xiao Q, He D, Zhou T, Liu W, et al. Design, synthesis and evaluation of the Brigatinib analogues as potent inhibitors against tertiary EGFR mutants (EGFR(del19/T790M/C797S) and EGFR(L858R/T790M/C797S)). Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2022;72:128729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thress KS, Paweletz CP, Felip E, Cho BC, Stetson D, Dougherty B, et al. Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat Med. 2015;21(6):560–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chmielecki J, Mok T, Wu YL, Han JY, Ahn MJ, Ramalingam SS, et al. Analysis of acquired resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer from the AURA3 trial. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eno MS, Brubaker JD, Campbell JE, De Savi C, Guzi TJ, Williams BD, et al. Discovery of BLU-945, a reversible, potent, and wild-type-sparing next-generation EGFR mutant inhibitor for treatment-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. J Med Chem. 2022;65(14):9662–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim SM, Fujino T, Kim C, Lee G, Lee YH, Kim DW, et al. BBT-176, a novel fourth-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor for osimertinib-resistant EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(16):3004–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia Y, Yun CH, Park E, Ercan D, Manuia M, Juarez J, et al. Overcoming EGFR(T790M) and EGFR(C797S) resistance with mutant-selective allosteric inhibitors. Nature. 2016;534(7605):129–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.BDTX-1535 Goes after Osimertinib Resistance. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(12):2952–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dardenne E, O’Connor M, Nilsson M, He J, Yu X, Heymach JV, et al. Abstract 1229: BDTX-1535: a MasterKey EGFR inhibitor targeting classical and non-classical oncogenic driver mutations and the C797S acquired resistance mutation to address the evolving molecular landscape of EGFR mutant NSCLC. Cancer Res. 2024;84(6):1229. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elamin YY, Nagasaka M, Shum E, Bazhenova L, Camidge DR, Cho BC, et al. BLU-945 monotherapy and in combination with osimertinib (OSI) in previously treated patients with advanced EGFR-mutant (EGFRm) NSCLC in the phase 1/2 SYMPHONY study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16):9011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu S, Wu L, Jian H, Cheng Y, Wang Q, Fang J, et al. Sintilimab plus chemotherapy for patients with EGFR-mutated non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer with disease progression after EGFR tyrosine-kinase inhibitor therapy (ORIENT-31): second interim analysis from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(7):624–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janne PA, Yu HA, Johnson ML, Steuer CE, Vigliotti M, Iacobucci C, et al. Safety and preliminary antitumor activity of U3–1402: a HER3-targeted antibody drug conjugate in EGFR TKI-resistant, EGFRm NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):9010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Y, Huang Y, Zhao Y, Zhao S, Xue J, Yang Y, et al. BL-B01D1, a first-in-class EGFR-HER3 bispecific antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, multicentre, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25(7):901–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou F, Guo H, Xia Y, Le X, Tan DSW, Ramalingam SS, et al. The changing treatment landscape of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2025;22(2):95–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotow JK, Lee JK, Madison RW, Oxnard GR, Jänne PA, Schrock AB. Real-world genomic profile of EGFR second-site mutations and other osimertinib resistance mechanisms and clinical landscape of NSCLC post-osimertinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2024;19(2):227–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.