Abstract

Changes in brain iron levels are a consistent feature of multiple sclerosis (MS) over its disease course. They encompass iron loss in oligodendrocytes in myelinated brain regions and iron accumulation in myeloid cells at so-called paramagnetic rims of chronic active lesions. Here, we explore the mechanisms behind this overall shift of iron from oligodendrocytes (OLs) to myeloid cells (MCs) and the loss of total brain-iron in MS. We investigated the expression of various iron importers and exporters, applying immunohistochemistry to a sample of control and MS autopsy cases. Additionally, we studied the transcriptional response of iron-related genes in primary rodent OL progenitor cells (OPCs) and microglia (MG) to various combinations of known MS-relevant pro-inflammatory stimuli together with iron loading. Histologically, we identified a correlation of OL-iron accumulation and the expression of the ferritin receptor TIM1 in myelinated white matter and observed an increase in the expression of iron-related proteins in myeloid cells at the lesion rims of MS plaques. qPCR revealed a marked increase of the heme scavenging and degradation machinery of MG under IFN-γ exposure, while OPCs changed to a more iron-inert phenotype with apparent decreased iron handling capabilities under MS-like inflammatory stimulation. Collectively, our data suggest that OL iron loss in MS is mainly due to a decrease in ferritin iron import. Iron accumulation in MCs at rims of chronic active lesions is in part driven by up-regulation of heme import and metabolism, while these cells also actively export ferritin.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40478-025-02020-0.

Keywords: Iron loss, Iron rim lesions, Multiple sclerosis, Oligodendrocytes, Microglia

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS), characterized by focal demyelination and neurodegeneration [1]. MS is highly heterogeneous regarding the disease activity and progression of neurological symptoms. However, the prospective identification and monitoring of patients with an accelerated progression of clinical symptoms is still challenging [2]. In this context, MR-based iron imaging has gained interest, as iron levels and distribution are markedly altered in the brains of MS patients [3, 4].

Iron and iron-sensitive MRI signals have been reported to be reduced in the MS brain tissue outside white and grey matter lesions and in the inactive center of chronic active (CA) and inactive (I) lesions [3–8], while an iron accumulation was described mainly in the globus pallidus and the putamen [9, 10]. In vivo iron loss has been studied in the thalamus and the non-lesioned white matter, where it correlates with a longer disease course and increasing disability [6, 11–14].

In MS, iron loss mainly affects oligodendrocytes (OLs), which require high amounts of intracellular iron for regular functioning [3, 15]. OLs are the cells containing the highest amount of intracellular iron in the healthy CNS [16] and, consequently, these cells are highly affected by iron deprivation [17]. While OL progenitor cells (OPCs) have a wide repertoire of iron uptake mechanisms such as the transferrin receptor [18, 19], mature OLs mainly depend on ferritin uptake via TIM1 [20, 21] to sustain intracellular iron concentrations. In the adult brain, ferritin is provided by astrocytes [22] and MCs [23] to OLs. The mechanisms underlying OL iron loss in MS are incompletely understood.

A subset of CA lesions shows iron accumulation in myeloid cells (MCs) at the lesion rim (LR) [4, 24, 25]. These lesions typically persist, expand over several years, and show continuous axonal damage at the lesion edge [4, 26–28].

While microglia (MG) are essential for proper myelin integrity, OL functioning, and neuronal development [29–31], iron-laden MG were identified to shift towards a neurotoxic phenotype [32]. Loss of the homeostatic MG-signature is correlated to MG iron loading [30, 33, 34]. Proinflammatory activation induces uptake of iron, mainly via non-transferrin-bound iron uptake mechanisms [35, 36]. In MS, iron laden MCs are localized at the lesion rim, where blood-derived heme and hemoglobin might promote intracellular iron accumulation [25, 37–39].

While the biological consequences of iron handling in MCs and OLs are studied widely, we aimed at elucidating the alterations of the iron uptake, heme degradation and iron export machinery on an autopsy sample of MS cases and controls, as well as in cell culture experiments, to identify potential mechanisms underlying the shift of iron from OLs to MCs and the consecutive loss of iron.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All investigations on post-mortem human samples were performed in accordance with the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EC-vote: 1067/2024 and 1636/2019). Studies on primary rodent cell cultures were performed in accordance with the 2010/63/EU directive. As all procedures were performed post-sacrifice, no review board approval was needed. Animals were primarily sacrificed for diagnostics assays.

Autopsy sample

Brain tissues from 15 people with MS (pwMS) and 19 controls were included in total, with only supratentorial tissues considered. Although precise disease durations were not available for all pwMS, clinical histories suggest a disease duration of at least several years for all cases. No active, but only chronic active and inactive MS lesions were included here.

We compiled a sample of 11 control cases (age ± standard deviation: 55 ± 16.5 years, female to male: 6:5) with no history of neurological disease and only minor findings upon neuropathological examination for the correlation analysis of TIM1 and Turnbull’s blue (TBB) optical densitometry (OD). For comparative analysis, we sex- and age-matched our MS cohort (age ± standard deviation: 56 ± 14.6 years, female to male: 10:5) to a control sample (age ± standard deviation: 56 ± 14.9 years, female to male: 10:5). Sample characteristics and tissue locations are shown in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Histology sample

| ID | Disease Course | Sex | Age (years) | Disease Duration | Lesion Type | Region | TIM1 (CO = 1.2) | LRP1 (CO = 1.2) | CD63 (CO = 1.3) | HEPH (CO = 1.7) | HRG1 (CO = 1.5) | TBB | TIM1 ~ TBB OD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl 1 | / | f | 70 | / | / | st WM | X | ||||||

| Ctrl 2 | / | m | 23 | / | / | st WM | X | ||||||

| Ctrl 3 | / | m | 75 | / | / | st WM | X | ||||||

| Ctrl 4 | / | f | 35 | / | / | st WM | X | ||||||

| Ctrl 5 | / | f | 49 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl 6 | / | m | 65 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ctrl 7 | / | f | 43 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl 8 | / | f | 54 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl 9 | / | m | 71 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl 10 | / | m | 32 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl 11 | / | f | 60 | / | / | WM DGM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ctrl 12 | / | f | 35 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Ctrl 13 | / | f | 62 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ctrl 14 | / | m | 56 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ctrl 15 | / | f | 84 | / | / | WM DGM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl 16 | / | m | 73 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X (WM DGM) |

| Ctrl 17 | / | f | 68 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl 18 | / | f | 44 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ctrl 19 | / | f | 44 | / | / | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| MS 1 | NA | m | 68 | NA | CA | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 2 | RRMS | m | 52 | NA | CA | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 3 | RRMS | m | 65 | 300 | I | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 4 | SPMS | f | 46 | 276 | CA | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 5 | SPMS | f | 44 | 252 | I | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 6 | SPMS | m | 73 | 120 | I | st WM | X | X | X | X | |||

| MS 7 | RRMS | f | 78 | 312 | I | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| MS 8 | RRMS | f | 46 | 216 | I | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 9 | SPMS | m | 34 | NA | CA | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 10 | SPMS | f | 50 | > 120 | CA | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 11 | PPMS | f | 30 | 84 | CA | WM DGM | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| MS 12 | NA | f | 76 | NA | I | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 13 | SPMS | f | 57 | 348 | I | WM DGM | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| MS 14 | SPMS | f | 61 | NA | CA | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MS 15 | NA | f | 60 | 408 | I | st WM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ctrl Mean Age ± SD |

56 ± 14.9 |

56 ± 14.9 |

56 ± 14.9 |

54.9 ± 14.8 |

56 ± 14.9 |

57.5 ± 14.2 |

55 ± 16.5 |

||||||

| MS Mean Age ± SD |

54.6 ± 14.9 |

56 ± 14.6 |

56 ± 14.6 |

56 ± 14.6 |

54.9 ± 11.8 |

56 ± 14.6 |

|||||||

| Ctrl Sex (f: m) | 10:5 | 10:5 | 10:5 | 10:4 | 10:5 | 9:5 | 6:5 | ||||||

| MS Sex (f: m) | 9:4 | 10:5 | 10:5 | 10:5 | 8:4 | 10:5 | |||||||

| Overall: | Ctrl Mean Age ± SD |

54.9± 16.5 |

MS Mean Age ± SD |

56 ± 14.6 |

|||||||||

| Ctrl Sex (f: m) | 12:7 | MS Sex (f: m) | 10:5 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: CA, chronic active; CO, cutoff of the normalized cellular staining intensity; Ctrl, control; f, female; I, inactive; m, male; NA, not available; OD, optical density; PPMS, primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SD, standard deviation; SPMS, secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; st WM, supratentorial white matter; TBB, Turnbull’s blue; WM DGM, white matter next to deep grey matter

Histo- and immunohistochemistry

Following block selection, 2 μm thick tissue slices were cut and placed onto silane-coated glass slides (Star Frost). After dry-heating the slides at 70 °C for 30 min, they were stored at room temperature. To visualize ferrous and ferric non-heme iron, the 3´,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) enhanced Turnbull blue (TBB) staining was performed using established protocols [3].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as described previously [40]. Slides were deparaffinized in xylene and, following rehydration, endogenous peroxidase was blocked by immersing the sections in 0.9% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min. Depending on the antibody (Table 2), heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed using either a pH6 citrate buffer (GV80511, Dako Omnis) or a pH9 EDTA buffer (GV80411, Dako Omnis) in a steamer (PT200, Dako Omnis) at 95 °C for 20 min. After blocking of nonspecific protein binding with 10% fetal calf serum in TRIS-buffered saline (TBS, pH = 7.4) for 10 min, the primary antibodies were diluted in antibody diluent (S2022, Dako Omnis) overnight at of 4 °C. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit Ig-antibody (K5007, Dako Omnis) was applied for 25 min. Slides were developed with a DAB buffer combination (K3468, Dako Omnis). Following counterstaining with Mayer’s hemalum, dehydration and incubation in n-butyl acetate, slides were coverslipped using a xylene based mounting medium (9990441, Epredia).

Table 2.

List of antibodies used for immunohistochemistry, including information on the targets, producers, catalogue numbers, retrieval methods for immunohistochemistry, concentrations for immunohistochemistry, respective concentrations for Immunofluorescence double-labeling, and host species. Abbreviations: Cat., catalogue; IF, Immunofluorescence staining; IHC, immunohistochemistry; OPCs, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells

| Antigen | Official full name | Target | Producer | Cat. Number | Antigen retrieval | IHC concentration | IF concentration | species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD63 | Cluster of Differentiation 63 | Vesicle associated protein | Biorbyt | orb229829 | low | 1:2000 | 1:1000 | rabbit |

| CD68 | Cluster of Differentiation 68 | Myeloid cells | Dako | M0814 | / | / | 1:500 | mouse |

| HEPH | Hephaestin | Ferroxidase | Santa Cruz biotech | sc-365,365 | low | 1:1000 | / | mouse |

| HRG1 | Heme responsive gene 1 | Heme-transporter | Invitrogen | PA5-42191 | none | 1:2000 | 1:1000 | rabbit |

| LRP1 | Low density lipoprotein receptor related protein 1 | Heme-hemopexin receptor | abcam | ab92544 | high | 1:500 | 1:250 | rabbit |

| MBP | Myelin basic protein | Myelin | Nordic BioSite | BSH-7697 | / | / | 1:100 | mouse |

| NG2 | Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 | OPCs | Sigma-Aldrich | ab5320 | / | / | 1:200 | mouse |

| TIM1 | T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 | H-ferritin receptor | Invitrogen | PA598302 | high | 1:2000 | 1:1000 | rabbit |

Immunofluorescence histochemistry

Immunofluorescence double-labeling was performed as described previously [41]. Following deparaffinization, rehydration and blocking of endogenous peroxidase, a pH6 buffer was used for heat-induced antigen retrieval andparaffin autofluorescence was blocked using 1% sodium borohydride in TBS for two minutes twice. Unspecific binding of antibodies was blocked with 10% normal goat serum for 30 min. Primary antibodies were applied in Dako antibody diluent. Following overnight incubation at 4 °C, fluorophore-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit (AF488, 711-485-152, Jackson ImmunoResearch; Cy3, 111-165-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and anti-mouse (AF488, 115-545-166, Jackson ImmunoResearch; Cy3, 115-165-166, Jackson ImmunoResearch) antibodies were applied diluted in Dako antibody diluent in the respective producer recommended concentrations. After nuclear staining with 1 µg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, D1306, Invitrogen) in TBS, the slides were coverslipped using an aqueous mounting medium (18606, Polysciences) and stored at 4 °C. Images were taken using a fluorescence microscope (BX63, Olympus) and Olympus CellSens software.

The double-labeled slides were quantified in QuPath v0.4.3 [42]. First, cells were detected on the DAPI channel. Then a classifier for each channel on the mean intracellular channel-intensity was set up. These two classifiers were then combined in a composite classifier. Regions for quantification were similar to those for cellular quantification of single stainings (see below).

Histological quantifications

All quantifications on DAB-stained slides were made in QuPath v0.4.3 [42]. For the TIM1-TBB correlation analysis, blocks from our control sample were selected. On each slide, three regions of interest (ROIs) were selected and placed in areas presenting the lowest, intermediate, and highest levels of white matter iron. Mean optical densitometry of the DAB staining vector was then measured for the respective regions on adjacent slides for TIM1 positivity and TBB positivity.

For the cellular quantification, a single slide per case was used and the whole white matter region available was annotated. ROIs on MS cases were defined as follows: the lesion center (LC) was defined as the demyelinated area, the lesion rim (LR) was an area of roughly 0.3 mm centering the border of the demyelinated area and expanding over the area of maximal MC accumulation. The LR is surrounded by the periplaque white matter (PPWM), which was further subdivided into close PPWM (LR to 3 mm) and PPWM (close PPWM to 1 cm from LR). White matter outside the PPWM was classified as normal-appearing white matter (NAWM). Larger vessels were excluded from the annotated area. On control slides, all available white matter was classified as normal white matter (NWM). Slides with obvious staining artefacts were excluded from the analysis.

Cells were identified using the cell detection tool on an adjusted hematoxylin vector. Cell detection was adapted regarding staining variations in between runs. Cell expansion was set to 2 μm. A groovy script was created, producing a ratio of mean DAB OD of the cell and the mean DAB of the 25 μm surrounding circular tile, to account for differences in background staining of the IHC stainings between blocks. For each antibody staining an individual cutoff was chosen (see Table 1).

Due to the high specificity of our TBB staining with no background reactivity, no correction for iron background staining was performed. Iron positivity was defined as a mean intracellular DAB TBB intensity > 0.25.

Lesion classification

We based our evaluations on the classification described elsewhere [43]. Briefly, we identified lesions as clearly demyelinated areas in the LFB staining. By evaluating the distribution of CD68+ myeloid cells, we classified the lesions into inactive (a clear decrease in cell density in the LC with no accumulation of CD68+ cells at the LC; I) and chronic active (an increase in CD68+ cells at the LR as compared to the surrounding PPWM and the LC; CA). Active lesions, characterized by an even accumulation of myeloid cells in the LC and LR, were not included in this study. The MS sample comprised 7 CA lesions and 8 I lesions (Table 1).

Isolation of primary rodent cell cultures

We used a previously published protocol [44], adapted from McCarthy et al. [45]. Shortly, timed pregnant Sprague Dawley rats were sacrificed, and the embryonic day 20 (E20) pubs were collected. The fetal cortices were isolated from the meninges, the brainstem, and the hippocampus, and diced in HBSS (14175095, Gibco) with 3% penicillin/streptomycin (PS) (1514022, Gibco). Subsequently, a single cell suspension was created using Miltenyi’s Neural Tissue Dissociation Kit (130–092–628, Miltenyi) in combination with C tubes (130-093-237, Miltenyi) and a heated tissue dissociator (130–096–427, Miltenyi). The cell suspension was filtered through a 70 μm strainer, and 300,000 cells/ml were seeded in DMEM/F12 + Glutamax (10565018, Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1%PS and 1% B27 (17504044, Gibco) onto T75 flasks (12 ml), creating a mixed glial cell culture comprised of MG, astrocytes, OPCs, and neurons. Media half changes were conducted every 2–3 days.

After 7–14 days the bottom astrocyte layer reached complete confluency and pushed the MG and OPC populations to the upper-most layer. Using cell type-specific adhesive forces, the subpopulations were separated by shaking with an orbital shaker (MTS 4, IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG). MG were separated by shaking the mixed culture for one and a half hours at 300 rpm. The supernatant containing MG was collected, centrifuged at 300 g for 4 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in one part DMEM/F12 + 10% FBS + 1% PS and one part TIC medium, comprised of DMEM/F12 + Glutamax with 1% PS, 10 ng/ml recombinant rat M-CSF (400 − 28, PeproTech), 2 ng/ml recombinant human TGF-β2 (100-35B, PeproTech), 1.5 µg/ ml ovine cholesterol (700000P, Avanti), 100 µg/ml human apo-Transferrin (T1147, Sigma-Aldrich), 5 µg/ml human insulin (16634, Sigma), 5 µg/ml N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; A9165, Sigma-Aldrich), and 15 ng/ml sodium selenite (S5261, Sigma) [46]. Cells were seeded at a density of 300,000/ml onto 6-well (2 ml per well) and 12-well (1 ml per well) plates and after 24 h, a 2/3 media change with TIC medium was performed to starve the MG of serum.

The medium of the original T75 was replenished and they were left for 2 h to equilibrate and recover. These cells were shaken for 16–20 h at 270 rpm. The supernatant was seeded onto uncoated dishes for differential adhesion. Contaminating MG and astrocytes share a higher tendency to adhere to uncoated surfaces and are thus more likely to be tethered to the surface after incubation. After 1 h, the final supernatant was filtered through a 40 μm strainer. Finally, the OPCs were seeded at a density of 300,000 cells/ml in OPC proliferation medium comprised of DMEM/F12 + Glutamax with 2% B27, 1% PS, 100 µg/mL BSA (9048-46-8, Sigma Aldrich), 100 µg/ml human transferrin, 5 µg/ml NAC, 5 g/ml human insulin, 62.5 ng/ml progesterone (P8773, Sigma Aldrich), 40 ng/ml sodium selenite, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360070, Gibco) and 20 ng/ml recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-AA (100–13A, Gibco), adapted from Bormann et al. [44].

Purity of our cultures was previously established at > 95% Iba1+ MG and > 90% NG2+ OPCs [44].

Exposure experiments

All exposure experiments were conducted at least 48 h after seeding, following at least one media change, with an exposure duration of 24 h. We selected the established MS driving cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ [47] as stimuli, as well as cell type specific iron formulations. Concentrations of cytokines and iron conditions were drawn from literature and previous experiments, showing no relevant amount of cell death but transcriptional response after 24 h [48, 49]. The concentration for all IFN-γ (400-20, Gibco) experiments was set at 20 ng/ml [50] and for TNF-α (10291-TA, RND) at 25 ng/ml [51]. Iron dextran (ID) (D8517, Sigma-Aldrich) was chosen for iron loading of MG, as described elsewhere [40, 52], while we decided to load OPCs with equus ferritin (CAS9007-73, merck), due to ferritin reportedly being the most relevant iron source of mature OLs [20]. MG were exposed to 2.08 µg/ml of ID, while the concentration of equus ferritin in the OPC experiments was set at 80 µg/ml. Higher concentrations of iron were chosen for OPCs, because they are described as holding the highest amount of intracellular iron in the healthy brain [16] as well as having a smaller transcriptional response to these stimuli, when compared to MG.

cDNA generation and qPCR

RNA was isolated using the peqGOLD, RNA isolation, MicroSpin Total RNA Kit (13-6831-02, VWR), following manufacturer’s recommendations. cDNA was generated using the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (1708891, Bio-Rad) as per producers’ recommendations.

All primers but the Rpl13a1 primer [44] for quantitative PCR (qPCR) were generated by using primer blast [53] on NCBI [54] (see Table 3).

Table 3.

List of primer sequences used for qPCR, including official full name, and function of the encoded protein

| Gene | Official Full Name | Function | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd63 | Cluster of Differentiation 63 | Vesicle associated gene | 5’-AGA GCA TCA AGA AGC GTC GG-3’ | 5’-CTG CTA CGC CAA TGG CAA TC-3’ |

| Fth1 | Ferritin heavy chain 1 | Iron storage/Ferroxidase | 5’-TGC CAT CAA CCG CCA GAT CAA-3’ | 5’-GCT CTC CCA GTC ATC ACG GTC-3’ |

| Hamp | Hepcidin antimicrobial peptide | Ferroportin inhibitor | 5’-AGA TGG CAC TAA GCA CTC GG-3’ | 5’-CTG CAG AGC CGT AGT CTG TC-3’ |

| Heph | Hephaestin | Ferroxidase | 5’-TGG AGC ATG GCT GAT GCA CT-3’ | 5’-TGC CCA GCA TCT TCA CAT TGC-3’ |

| Hmox1 | Heme oxigenase 1 | Heme degradation encyme | 5’-CAG AAG AGG CTA AGA CCG CC-3’ | 5’-AGA GGT AGT ATC TTG AAC CAG GC-3’ |

| Lrp1 | Low density lipoprotein receptor related protein 1 | Heme-hemopexin receptor | 5’-AACTGGCACACGGGCACTAT-3’ | 5’-TTTGCGCCACCTCAATCACG-3’ |

| Rpl13a | Ribosomal protein L13A | Reference gene | 5’-GGA TCC CTC CAC CCT ATG ACA-3’ | 5’-CTG GTA CTT CCA CCC GAC CTC-3’ |

| Scara5 | Scavenging receptor class A, member 5 | Ferritin light chain receptor | 5’-GAC AGC TCG TTT TGG GCA AG-3’ | 5’-CCC CAT TTG GAG AAC TGG CA-3’ |

| Slc11a2 | Solute carrier family 11 member 2 | Divalent metal channel | 5’-AAT AGG CTG GAG GAT CGC AGG-3’ | 5’-GGT ATC TTC GCT CAG CAG GAC T-3’ |

| Slc40a1 | Solute carrier family 40 member 1 | Iron exporter | 5’-TTC CGC ACT TTT CGA GAT GG-3’ | 5’-TAC AGT CGA AGC CCA GGA CTG-3’ |

| Slc48a1 | Solute carrier family 48 member 1 | Heme channel | 5’-TTC TTC GTC TGG ACG GTG G-3’ | 5’-AAC GTC AGG AAG GTG CAG AA-3’ |

| Timd2 | T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 2 | Ferritin receptor | 5’-GAA GCT GCA GAG AAA CCC GAC-3’ | 5’-AAT TCT GGC CTG CTC CAC CAC-3’ |

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using the BioRAD SsoAdvanced universal SYBRR Green Supermix (1725271, Bio-Rad,) on an AriaMX PCR-system (40972, Agilent), with initial denaturation on 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s of denaturation at 95 °C, 30 s of annealing, and extension at 60 °C. We generated fold changes via the ΔΔCT method, using Rpl13a1 as the reference gene [55]. Obvious outliers were excluded before this step. For plotting we used the log2 fold changes (log2FC) when ΔCT values were below 15, when none of the groups averages was below this ΔCT we did not plot the results.

Statistical testing

For qPCR results we used GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1. qPCR results were analyzed using Welch’s analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s T3 for multiple comparisons. Immunohistochemical data were analyzed using the scripting language R (v4.3.0 [56]), and RStudio (v2023.06.0 + 421 [57]). For data wrangling the dplyr (v1.1.4 [58]), and tidyverse (v2.0.0 [59]), packages were used. The OD correlations were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation from base R, due to violation of homoscedasticity and nonlinearity of DAB OD measurements. Comparisons between NWM and NAWM were performed using Welch’s t-test for unequal variances. To adjust for staining variations between slides and runs, the data from MS cases was analyzed via a random effects model from the lme4 package (v1.1.35.1 [60]), using the interaction of location and lesion activity as the fixed effect and case number as the random intercept (cell count/mm2 ~ location*lesion type + (1|case)). Pairwise comparisons were computed using the emmeans package (v.1.8.8 [61]), applying Tukey’s test for p-value adjustment. Data visualization was performed via the ggplot2 package (v.3.4.4 [62]). Due to small sample sizes, p-values below 0.1 were considered statistical trends, while p-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Iron and Iron uptake in controls and MS

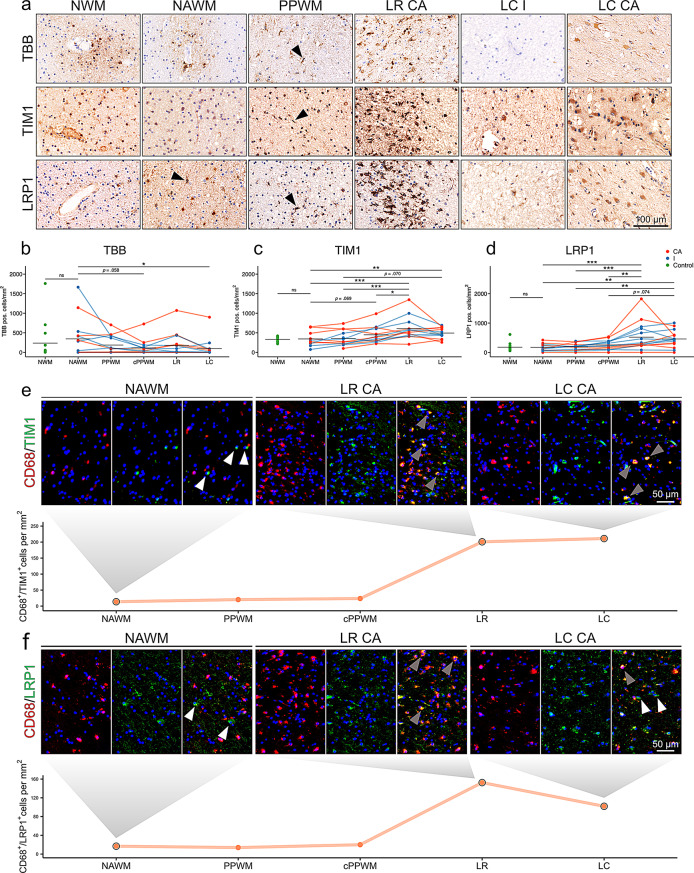

In controls, OLs contained the highest amounts of intracellular iron, with highest levels observed in the subcortical U-fibers and WM in the vicinity of deep grey matter regions. In the WM of the centrum semiovale, iron was distributed in a patchy pattern, with highest amounts in perivascular OLs (Fig. 2a, S1a), as described [3, 63]. The relative distribution of iron was similar between the normal white matter (NWM) of controls and the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) of pwMS. In the lesion-adjacent periplaque white matter (PPWM), additionally to OLs, ramified cells with a MG morphology [64] accumulated iron (Fig. 2a). At the LR of a subset (50%) of CA lesions (6), iron accumulation was found in MCs, with either ameboid, dystrophic or phagocytic features [65] (Fig. 2a, b). In the inactive center of lesions, TBB+ cells were almost completely absent, except for a single CA LC having shown noticeable iron accumulation in astrocytes (Fig. 2a). The frequency of iron-positive cells was significantly reduced in the lesion center and showed a decreasing trend in the close PPWM compared to the NAWM (Fig. 2b). Collectively, the frequency of cells holding iron is reduced in a lesion dependent manner, while some CA lesions show an accumulation of iron laden MCs at the LR.

Fig. 2.

Iron, TIM1 and LRP1 in the supratentorial WM of pwMS. (a) Image panel of TBB, TIM1 and LRP1 on the normal white matter (NWM) of controls, the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM), periplaque white matter (PPWM), the lesion rim (LR) of chronic active (CA) lesions, and the lesion center (LC) of inactive (I) and chronic acitive (CA) lesions. Arrowheads indicate cells with a typical ramified MG morphology. Quantification of (b) TBB+, (c) TIM1+, and (d) LRP1+ positive cells overall. Black lines indicate means. NWM and NAWM were compared using Welch’s t-test for unequal variances. For comparison of NAWM, distant PPWM, close PPWM (cPPWM), LR and LC a mixed effects model with case as a random intercept effect was chosen (positive cells/mm2 ~ location*type (CA, I) + (1|case)). Significant p-values are indicated with asterisks: *≤ 0.05, ** ≤0.01, *** ≤0.001. (e) and (f) double-labeling of TIM1 and LRP1 with the phagocytosis marker CD68 on a tissue block of a CA lesion. White arrowheads indicate single positive cells for TIM1 and LRP1, grey arrowheads indicate double positive cells. The plots show quantification of one CA lesion.

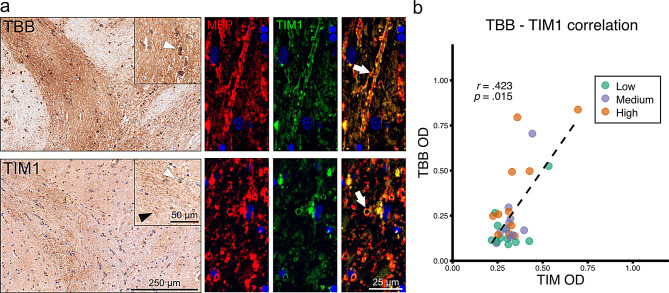

To investigate iron uptake in the WM of controls, we studied the expression of the ferritin receptor TIM1 and the receptor for heme-hemopexin complexes, LRP1. TIM1 was expressed on OLs in essentially all studied brain regions (Fig. 1a; Fig. S1a, b). In iron-rich regions, such as the nucleus dentatus and the deep grey matter, in addition, strongly TIM1-positive granular and partly ring-shaped structures were found, suggesting its localization on iron-laden myelin sheaths. Double-labeling using the myelin protein MBP and TIM1 on iron-rich white matter regions confirmed colocalization (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we have shown a positive correlation of TBB and TIM1 intensity using digital quantification (Fig. 1b). TIM1 was expressed in OLs in similar frequencies in the NWM and the NAWM. In the PPWM, partly dystrophic MCs increasingly expressed TIM1. Upregulation in MCs culminated in a pronounced accumulation of TIM1+ MCs at the LR of both CA and I lesions. In the LC, sparse positivity of cells mainly with a macrophage or astrocyte morphology was found (Fig. 2a, S1b). Statistical testing showed a significant increase of TIM1+ cells at the LR and the LC, when compared to NAWM and PPWM regions (Fig. 2c). These findings imply that TIM1 is expressed in MCs in an activation dependent manner.

Fig. 1.

Exploration of iron and TIM1 staining patterns (a) TBB and TIM1 staining on pencil fibers in putamen. Co-labeling of MBP and TIM1 revealed colocalization in this area. White arrowheads indicate positive cells. Black arrowheads indicate granular TIM1 positivity. White arrows indicate double positive myelin sheaths. (b) TBB and TIM1 optical densitometry (OD) of one region of interest per control tissue block each with low, medium, and high iron density correlated (Spearman’s correlation, r =.423, p =.015).

LRP1 was expressed in a subset of round OL-shaped cells (Fig. a; S1a, b). Previous data suggest that the expression of LRP1 is restricted to OL progenitor cells (OPCs) [19]. We therefore used co-labeling with NG2 and found the majority of LRP1+ cells in the white matter of controls were NG2+ OPCs (Fig. S1c). LRP1 showed no significant correlation with iron OD in the tissues of controls (data not shown).

While LRP1 was restricted to OPC-shaped cells in the NWM, the NAWM of MS cases already contained ramified bipolar LRP1+ cells, typical for MG (Fig. S1b). This trend continued throughout the PPWM (Fig. 2a). At the LR continuing towards the LC, the number of LRP1+ cells with a macrophage and astrocyte phenotypes increased markedly (Fig. 2a, d).

Collectively, our results suggested an increase in TIM1 and LRP1 expression in MCs towards the MS lesion, putatively driven by inflammation. We confirmed this finding via double-labeling with the MC marker CD68 on a CA lesion (Fig. 2e, f).

OPCs exhibit an iron-inert phenotype upon proinflammatory stimulation

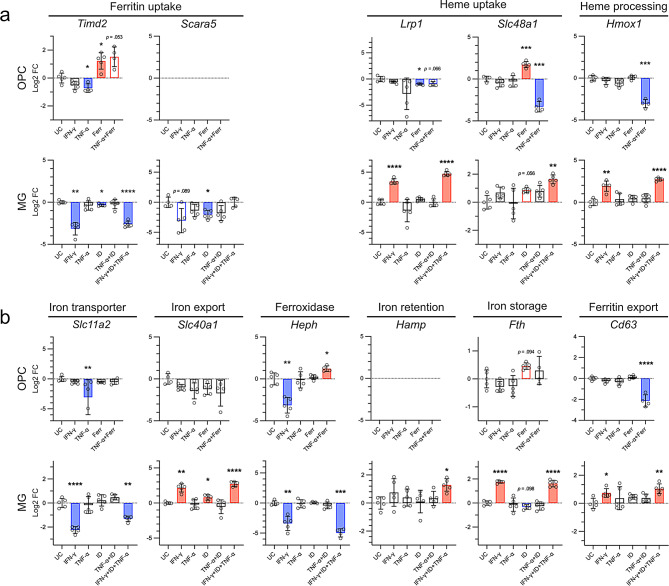

Primary rodent OPCs exhibited a weak but significant downregulation of Timd2, the rodent homologue of TIM1 [21], upon TNF-α stimulation. Conversely, iron laden ferritin (Ferr) exposure significantly induced Timd2, non-significantly so even in combination with TNF-α (Fig. 3a). The expression of the ferritin light chain receptor Scara5 [66] remained below biologically relevant levels under all conditions (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

qPCR results of primary rodent OPCs and MG. Cells were isolated using shaking of mixed glial cell cultures. MG and OPCs were stimulated for 24 h. Data were analysed using the Δ ΔCT method. Data were plotted as log2 fold changes. In cases of low expression levels (OPC/Scara5 and OPC/Hamp), no data points were plotted. Bars indicate the mean, whiskers indicate the standard deviation. Statistical testing was performed using Welch’s ANOVA for unequal variances, multiple comparisons were corrected using Dunnett’s T3. Significant p-values are indicated with asterisks: *≤ 0.05, ** ≤0.01, *** ≤0.001.

The heme-hemopexin receptor Lrp1 was significantly downregulated upon Ferr exposure in OPCs. In contrast, Ferr induced expression of the heme transporter channel Hrg1 (Slc48a1), which facilitates heme-iron transport from the lysosome to the cytoplasm, while Slc48a1 and the heme degradation enzyme heme-oxygenase 1 (Hmox1) were significantly downregulated upon TNF-α + Ferr exposure (Fig. 3a).

Regarding OPC iron export, we studied the expression of Cd63, implicated in ferritin export via extracellular vesicles [67], ferroportin (Fp, encoded by Slc40a1), and the ferroxidase hephaestin (Heph), partnering with ferroportin for iron export. Cd63 was downregulated upon TNF-α + Ferr stimulation upon iron loading only. Conversely, the iron exporter channel Fp was downregulated in all conditions, albeit non-significantly. IFN-γ led to a downregulation of Heph, while the combination of TNF-α and ferritin led to its minor upregulation. We found no Ferr induced alterations in any transcripts known to contain iron responsive elements, such as Cd63, Slc40a1, Heph, ferritin heavy chain 1 (Fth), or the divalent metal transporter 1 (Dmt1; encoded by Slc11a2). Slc11a2 was downregulated in the TNF-α condition, while this effect was not found in combination with Ferr (Fig. 3b).

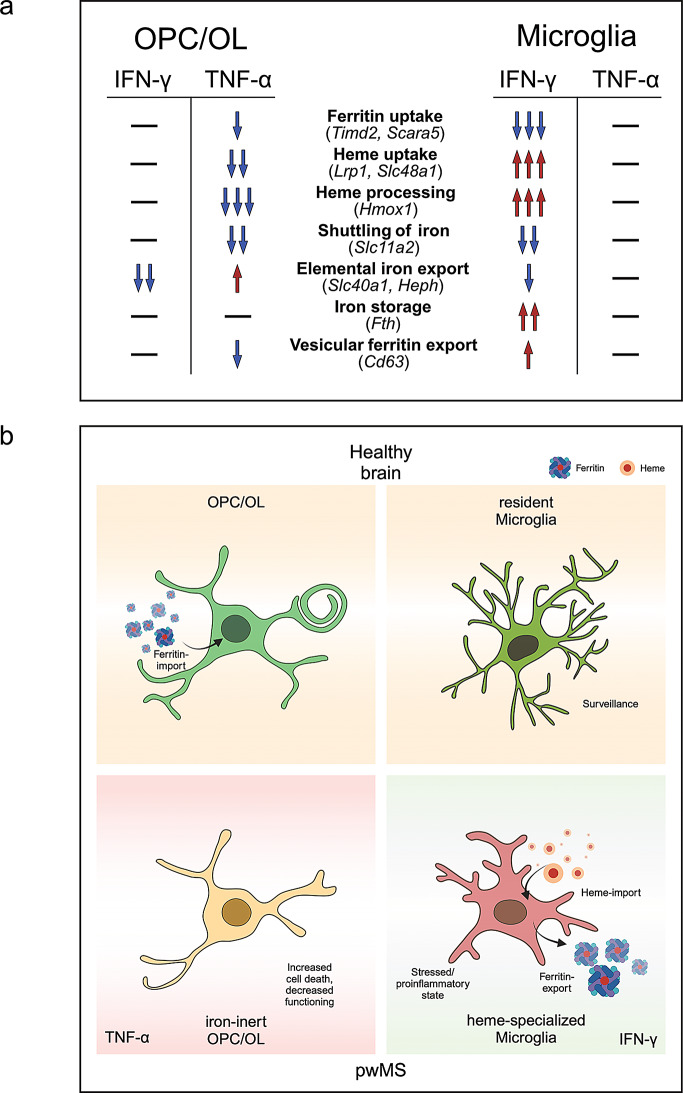

Collectively, these data suggest decreased iron importer capabilities in OPCs in the TNF-α conditions.

IFN-γ induced the expression of heme-handling transcripts in MG

MG showed a pronounced downregulation of Timd2 in all IFN-γ conditions, which contrasts with our observations on the autopsy tissues, where TIM1 was increased towards the lesion rim. Transcripts of the ferritin light chain receptor Scara5 were downregulated upon IFN-γ (not significant) and iron-dextran (ID). Studying heme uptake and degradation, we found a clear upregulation of Lrp1 in all IFN-γ conditions, while Cd163 was not found to be expressed to a biologically relevant degree in MG (CT > 35 in all conditions, data not shown). Transcription of the heme channel Slc48a1 was significantly induced in the combination condition (TNF-α, IFN-γ and ID), mimicking the environment of iron-laden MG at the LR [68]. The RNA levels of Hmox1 were notably upregulated under IFN-γ conditions (Fig. 3a). Additionally, IFN-γ signaling induced an upregulation of the ferritin export-associated protein Cd63 and Slc40a1. Fp (encoded by Slc40a1) functions in conjunction with Heph, which exhibited a significant downregulation in the presence of IFN-γ. When considering the concurrent upregulation of the Fp-inhibitor Hamp in the combined condition (IFN-γ, ID, and TNF-α), interpreting whether a functional increase in Fp facilitated Fe2+ export occurs in the IFN-γ conditions becomes challenging. Fth transcripts showed a 4-fold increase in the presence of IFN-γ, while the Fe2+ transmembrane transporter Dmt1 exhibited a decrease in expression. This is contrasted by findings of inflammatory stimulation with amyloid beta and LPS inducing Dmt1 [35]. ID on its own had little impact on the expression profile of those RNAs containing an iron responsive element, which are Slc40a1, Heph, Fth, Slc11a2, Cd63 (Fig. 3b).

Taken together, we found differential expression of iron handling genes in OPCs and MG, with an overall pattern of less iron handling in OPCs mainly via TNF-α, versus increased heme-iron processing in MG mainly upon IFN-γ stimulation, in part moderated by iron.

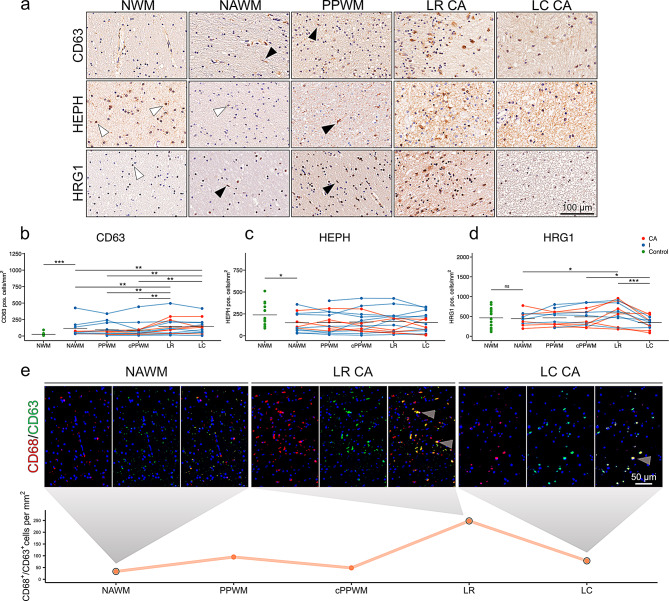

Histological validation of inflammation-responsive iron genes

We inferred from our qPCR data that CD63 and HRG1 are upregulated in MCs in MS, while HEPH might be downregulated in perilesional areas. Upon neuropathological inspection of control cases, we found CD63 expression on endothelial cells and astrocytes (Fig. 4a). We also found a significant increase in the frequency of CD63+ cells in the NAWM of pwMS when compared to the NWM of controls (Fig. 4b). Cells with an MC morphology express CD63 in this region. In the vicinity of WM lesions (PPWM), an increased number of cells up-regulate CD63, culminating in high expression levels in foamy macrophages at the LR of CA and I lesions (Fig. 4a). At the LC of CA as well as I lesions, we found a sustained up-regulation in cells with a range of different cellular phenotypes (Fig. 4a). These observations were substantiated via quantification, showing significant increases in CD63+ cells towards the LR and LC of all lesion types (see Fig. 4b). Upon co-labeling of CD63 and CD68, CD63+ phagocytes markedly increased towards the lesion, with a punctum maximum at the LR (Fig. 4e). This confirms our qPCR data showing IFN-γ-driven CD63 induction in MG.

Fig. 4.

Validation of qPCR targets found in cell culture experiments. (a) CD63, HEPH and HRG1 stainings on a control and in MS cases. Black arrowheadsindicate rod shaped microglia. White arrowheads indicate oligodendrocytes. Quantification of (b) CD63+, (c) HEPH+, and (d) HRG1+ positive cells. Black lines indicate means. Normal white matter (NWM) and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) of the CD63 staining were compared using Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. NWM and NAWM of HEPH and HRG1 were compared using Welch’s t-test for unequal variances. For comparsion of NAWM, distant periplaque white matter (PPWM), close PPWM (cPPWM), lesion rim (LR) and lesion center (LC) a mixed effects model was chosen with case as a random intercept effect (positive cells/mm2 ~ location*type (CA, I) + (1|case)). Significant p-values are indicated with asterisks: *≤ 0.05, ** ≤0.01, *** ≤0.001. (e) Double-labeling of CD63 and CD68 on a CA lesion. Grey arrowheads indicate double positive cells. The plot shows quantification of one CA lesion.

To add to the previous histological data on HEPH [3], we stained supratentorial CNS tissues of 15 MS cases and of 14 controls (Fig. 4a). HEPH was extensively expressed in OLs throughout NWM regions (Fig. 4a, Fig. S1a, b). We confirmed the previously described downregulation of HEPH in the NAWM compared to the NWM, within the OL population (Fig. 4a, c). Within the MS cases, no significant alterations between ROIs were found, although the frequency of HEPH+ cells in general decreased in the LC.

Fig. 5.

Graphical summary of RNA expression data. (a) Representation of the alterations of iron-handling mechanisms in oligodendrocytes (OL) and OL progenitor cells (OPC) under inflammatory conditions as suggested by qPCR data. (b) Implicated phenotypical alterations in OPC/OL and microglia (MG) in the brains of people with MS. Created in BioRender.com. https://BioRender.com

We found HRG1 to be mainly expressed in OLs in the NWM (Fig. 4a). No differences in frequencies of HRG1+ cells between the NAWM and the NWM were found (Fig. 4d). The cell types expressing HRG1 in the NAWM showed multiple phenotypes, such as OLs, MG, and astrocytes. At the LR of MS lesions foamy and ameboid macrophages showed clear HRG1 positivity (Fig. 4a). The accumulation of these cells at the LR was significant when compared to the NAWM. The number of HRG1+ cells decreased again towards the LC (Fig. 4d).

Collectively, the inflammatory environment of MS was linked to the upregulation of CD63 and HRG1 in MCs, while HEPH was reduced in MS tissues, in line with our qPCR data.

Discussion

In our view, this study provides novel insights into the dynamic nature of iron handling in MS.

Iron content alterations are a consistent feature of progressive MS pathology [1]. Multiple cell types in the CNS are participating in the processes underlying the iron alterations, in principle leading to diffuse iron loss from myelinated regions in the MS brain and focal iron accumulation in a subset of chronic active MS lesions, leading to paramagnetic rim lesions (PRLs) in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both iron loss and accumulation are spatially connected [69], suggesting a mechanistic inter-relation of these processes.

Since OLs are the major iron-storing cells in the non-lesioned CNS [16], any substantial loss from myelinated white matter regions necessarily implicates changes in OL iron handling [3]. Conversely, iron accumulation in MS predominantly occurs in MCs, including MG, as demonstrated by multiple studies [24, 25]. While iron accumulation in MCs and its effects were extensively studied on a cellular level, comparable data on OL iron loss is still scarce. Our transcriptional analyses of primary rodent cell cultures as well as histological examinations of human control and MS tissues revealed an upregulation of iron-related proteins in MCs while OLs generally seemed to shift to a more iron-inert phenotype (Fig. 5). Our current results on iron-responsive MCs partly add to a large body of already existing data. However, we believe that increased iron uptake, turnover and mobilization by MCs in conjunction with a generally decreased iron handling in OLs would represent a novel and useful framework for the understanding of iron alterations in pathological states of the CNS, particularly in progressive MS.

OLs require iron for maturation, myelination, and functioning [17, 70]. Without direct contact to the neurovascular unit, they are supplied with ferritin iron mainly by surrounding glia [22, 23]. TIM1 is accordingly described to be the main iron importer in mature human OLs [21]. In controls, we indeed found TIM1 expression in OLs and its correlation with tissue iron levels. In addition, we were able to localize TIM1 to the myelin sheaths of iron-rich regions by means of immunohistochemistry, which substantiates its role in iron uptake into OLs and particularly myelin under homeostatic conditions [21]. This potential role of TIM1 is further corroborated by our cell culture experiments, where its expression was induced upon ferritin loading, suggesting ligand- and iron-dependent induction of TIM1. Such a positive feedback mechanism supports the preferential and profound OL iron uptake, since a ferritin shell may contain up to 4500 iron atoms. By contrast, LRP1 was mainly expressed by OPCs, and not mature OLs in the white matter of controls and pwMS [71]. Upon stimulation with TNF-α + Ferr, Heph was significantly up-regulated, while it was downregulated upon IFN-γ, which confirms the observed HEPH+ OL decrease on the immunohistochemical level in MS NAWM versus control NWM, both in our previous [3] and current study. Collectively, OPC iron importers, including Timd2 and Lrp1, were either downregulated or unchanged under pro-inflammatory cell culture conditions. However, OPCs downregulated heme-iron processing proteins upon TNF-α stimulation, including a significant downregulation of Hmox1, which also shields cells from oxidative stress [72]. Inferring from our cell culture model and histological data, reduced OL iron might thus be mediated by a reduction in iron import, and less so due to OL iron export increase, as suggested previously [3, 5]. However, reduced OL iron might also result from a preferential loss of iron-containing OLs, since iron-rich OLs are at elevated risk of cell death under pro-inflammatory conditions involving TNF-α [48]. Both mechanisms (OL iron export, loss of iron-rich OLs) might occur side-by-side, however, and it remains to be studied to which relative extent these take place. Regarding the consequences of iron depletion, it is well established that iron deficiency during development leads to severe disturbances in myelin maturation, content, and structure [63]. However, the effects of OL iron deficiency in the adult brain are less well established and might, for example, influence iron-dependent processes such as remyelination [73], possibly warranting future studies.

Since iron complexes from perishing OLs could likely be taken up by MCs via TIM1, SCARA5, and DMT1, as well as products from cell debris scavenging per se. This interpretation is backed up by our histological data, showing marked increase of MC TIM1 at the chronic active lesion rim, where myelin and oligodendrocytes get damaged and degraded [24].

LRP1, which mediates the uptake of heme-hemopexin complexes [74, 75], is also implied in OPC maturation [76, 77] and thus potentially supports iron uptake OPCs. Its suppression upon ferritin loading should be interpreted with caution, since it might be due to an induction of maturation towards OLs, which is accompanied by a Lrp1 loss.

Iron accumulation in MCs is a well-established phenomenon in MS, forming the biophysical basis of PRLs [25–27, 40, 78, 79]. The known persistence of PRLs implies a stable and non-dynamic situation of MC iron load. This is also reflected in the persistence of iron depositions over months following hemorrhagic infusion of the brain [80]. Our cell culture and histopathological data also suggest a more dynamic situation, as we found an upregulation of the putative ferritin exporting protein Cd63 [81, 82] upon IFN-γ, and a higher frequency of CD63+ MCs surrounding MS plaques on a histological level. Together with our previous study on the haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex receptor CD163 upregulation in iron-loaded MCs at chronic active lesion rims [25], our data suggest that MG/MCs take up hemoglobin or heme-iron to shield tissue from-heme induced tissue damage [83], leading to iron loading of onsite macrophages, potentially followed by an excretion of ferritin-complexed iron. The idea of dynamic iron handling in MCs is corroborated by findings of increased liquor ferritin concentrations in brain hemorrhage, infection [84], and also progressive MS [85].

Our qPCR data on MG provide further support for upregulation of specific iron importers in MG/MCs under inflammatory conditions [25]. We found a marked upregulation of transcripts of the heme uptake and breakdown machinery upon IFN-γ stimulation, as well as increased expression of the tetraspanin Cd63, which is involved in ferritin export. Conversely, Dmt1 transcripts, encoded by Slc11a2 and relevant for non-heme iron uptake [86], were significantly downregulated. We thus suggest that the inflammatory environment of MS induces a heme-specialized MG phenotype, mainly via IFN-γ, effectively transforming heme-iron to ferritin-iron, while OPCs seem to become overally iron-inert and iron-depleted, possibly mainly via TNF-α. While we found an abundance of LRP1+ and TIM1+ phagocytes at the LR of CA lesions, Timd2 was not induced by exposure to our tested set of stimuli in MG. This implies that further stimuli are needed to produce the rim-macrophage phenotype. Histological validation showed an increase of HRG1 (encoded by Slc48a1 in rodents) and CD63 expression in MCs at the lesion rim, while the iron export-associated ferroxidase HEPH was reduced in MS tissues. Thus, we suggest that iron rim sustenance is a sign of ongoing BBB-disturbance, with IFN-γ induced, heme-ingesting MCs facilitating blood iron scavenging [87, 88].

The transcriptional response of MG to iron loading is highly context dependent. In the absence of a distinct pro-inflammatory stimulus, iron laden MG do not show an increase in pro-inflammatory genes [49, 50] and even providing OLs with ferritin [23, 49], while preactivated MG, e.g. with serum [40] or TNF-α [49], have been shown to shift to a pro-inflammatory phenotype, while losing resting microglial genes. Iron laden MCs at the rims of CA lesions are typically correlated with ongoing inflammation and axonal break down [26, 89, 90] and typical finding in MS [3, 30, 91, 92].

OL iron loss and MC iron accumulation seem to be partly inter-related, as suggested by recent MRI literature showing the relation of susceptibility loss, an MRI surrogate for iron content, in non-lesioned pulvinar thalami and presence as well as distance of paramagnetic rim lesions (PRLs) [69]. A potential consequence of iron loading and potential explanation for the loss of iron laden OLs is iron-dependent cellular demise [5]. Ferroptosis is a novel non-apoptotic programmed cell death mechanism, potentially leading to increased cellular demise in the iron laden OL population, as well as iron laden MCs [32, 93]. To which extent each of these populations are pushed towards ferroptosis in MS is still to be determined.

Limitations

This study is restricted by the small sample size of the autopsy sample, the differences between rodent and human cells [94], and potential differences between OPCs and mature OLs. By combining histological examinations on a human autopsy sample with rodent cell culture experiments, we make a cumulative case for the mechanisms behind the shift of iron from oligodendrocytes to myeloid cells.

Conclusions

In summary, we propose a dynamic process of iron handling in MS. Upon MS-typical widespread TNF-α signaling, OLs might be impaired in their ability to take up iron and react to oxidative stress, while IFN-γ-stimulated MCs ingest iron-laden blood products and iron from perishing OLs, leading to an accumulation in this cellular compartment, followed by a conversion to ferritin iron and, possibly, a subsequent mobilization into extracellular vesicles. This interpretation provides a biological framework for understanding iron accumulation and mobilization in MS and holds implications for clinical decision making and future drug development. However, further validation is needed through additional experimental setups, including functional studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1: Low magnification images of LFB, iron, TIM1, LRP1, and HEPH, including cell specific staining patterns and NG2 and LRP1 co-labeling. (a) Luxol fast blue (LFB) staining shows white matter of a control with an even myelin staining pattern. Turnbull’s blue-staining (TBB) shows a patchy pattern of iron in the WM with highest levels in oligodendrocytes (OLs) surrounding vessels. TIM1, LRP1, and HEPH are expressed in cells with an oligodendrocyte (OL) like morphology. White arrowheads indicate positive cells. (b) Figure panel depicts glial and foamy macrophage (MP) morphology with staining patterns in controls and MS cases. OLs and OL progenitor cells (OPCs) appear as small round cells with a collapsed cytoplasm, occasionally leading to a fried egg shaped morphology. Astrocytes (AC) contain a nucleus with loosely configured chromatin, an extensive cytoplasm with multiple longer processes. Microglia (MG) in the aged brain have an elongated tubular nucleus with a bipolar distribution of processes. Foamy MPs have a compact nucleus and a large round cell body with multiple granules. (c) In the white matter of a control, most cells showing clear LRP1 positivity were NG2 positive, suggesting an OPC restricted expression. White arrows indicate double positive cells.

Author contributions

C.J.R. and S.H.: conceptualization and overall design. C.J.R., D.B., A.S., A.N., and G.T.: investigation–execution of cell culture experiments. C.J.R., A.N., G.T., E.P., and C.H.: investigation–execution of immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence stainings. C.J.R. and S.H.: data analysis. T.B., M.M., R.H., F.S., and S.H.: resources. F.S. and S.H.: funding acquisition. MM supervised D.B. R.H. and S.H. supervised C.J.R. S.H. supervised A.S., A.N., G.T., and E.P. C.J.R., T.B., M.M., F.S., and S.H. writing–original draft, visualization. All authors have participated in writing and have critically revised the manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results received funding by two research grants, awarded to SH in 2023 and 2024, of the “MS-Forschungsgesellschaft Österreich” and by the National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01NS114227. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

All studies on post-mortem human samples were performed in accordance with the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EC-vote: 1067/2024 and 1636/2019). Studies on primary rodent cell cultures were performed in accordance with the 2010/63/EU directive. As all procedures were performed post-sacrifice, no review board approval was needed. Animals were primarily sacrificed for diagnostics assays.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kuhlmann T et al (2023) Multiple sclerosis progression: time for a new mechanism-driven framework. Lancet Neurol 22(1):78–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calabrese M et al (2024) Determinants and biomarkers of progression independent of relapses in multiple sclerosis. Annals of Neurology [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hametner S et al (2013) Iron and neurodegeneration in the multiple sclerosis brain. Ann Neurol 74(6):848–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahmanzadeh R et al (2022) A new advanced MRI biomarker for remyelinated lesions in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 92(3):486–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweser F et al (2021) Decreasing brain iron in multiple sclerosis: the difference between concentration and content in iron MRI. Hum Brain Mapp 42(5):1463–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweser F et al (2018) Mapping of thalamic magnetic susceptibility in multiple sclerosis indicates decreasing iron with disease duration: A proposed mechanistic relationship between inflammation and oligodendrocyte vitality. NeuroImage 167:438–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao B et al (2014) 7 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging to detect cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 9(10):e108863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paling D et al (2012) Reduced R2’ in multiple sclerosis normal appearing white matter and lesions May reflect decreased Myelin and iron content. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83(8):785–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalil M et al (2015) Dynamics of brain iron levels in multiple sclerosis: A longitudinal 3T MRI study. Neurology 84(24):2396–2402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalil M et al (2011) Determinants of brain iron in multiple sclerosis: a quantitative 3T MRI study. Neurology 77(18):1691–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgetova A et al (2017) Thalamic Iron differentiates Primary-Progressive and Relapsing-Remitting multiple sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38(6):1079–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zivadinov R et al (2018) Brain Iron at quantitative MRI is associated with disability in multiple sclerosis. Radiology 289(2):487–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontillo G et al (2021) Unraveling deep Gray matter atrophy and Iron and Myelin changes in multiple sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 42(7):1223–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández-Torres E et al (2015) Orientation dependent MR signal decay differentiates between people with MS, their asymptomatic siblings and unrelated healthy controls. PLoS ONE 10(10):e0140956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephenson E et al (2014) Iron in multiple sclerosis: roles in neurodegeneration and repair. Nat Reviews Neurol 10(8):459–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinert A et al (2019) Iron concentrations in neurons and glial cells with estimates on ferritin concentrations. BMC Neurosci 20(1):25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beard JL, Wiesinger JA, Connor JR (2003) Pre- and postweaning iron deficiency alters myelination in Sprague-Dawley rats. Dev Neurosci 25(5):308–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J et al (2024) Contrasting Iron metabolism in undifferentiated versus differentiated MO3.13 oligodendrocytes via IL-1β-Induced Iron regulatory protein 1. Neurochem Res 49(2):466–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández-Castañeda A et al (2020) The active contribution of OPCs to neuroinflammation is mediated by LRP1. Acta Neuropathol 139:365–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todorich B, Zhang X, Connor JR (2011) H-ferritin is the major source of iron for oligodendrocytes. Glia 59(6):927–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiou B et al (2018) Semaphorin4A and H-ferritin utilize Tim‐1 on human oligodendrocytes: a novel neuro‐immune axis. Glia 66(7):1317–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheli VT et al (2021) H-ferritin expression in astrocytes is necessary for proper oligodendrocyte development and myelination. Glia 69(12):2981–2998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schonberg DL et al (2012) Ferritin stimulates oligodendrocyte genesis in the adult spinal cord and can be transferred from macrophages to NG2 cells in vivo. J Neurosci 32(16):5374–5384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dal-Bianco A et al (2017) Slow expansion of multiple sclerosis iron rim lesions: pathology and 7 T magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Neuropathol 133(1):25–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofmann A et al (2023) Myeloid cell iron uptake pathways and paramagnetic rim formation in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol 146(5):707–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dal-Bianco A et al (2021) Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis iron rim lesions in 7 T MRI. Brain 144(3):833–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krajnc N et al (2022) Peripheral hemolysis in relation to Iron rim presence and brain volume in multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol 13:928582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeves JA et al (2024) Paramagnetic rim lesions predict greater long-term relapse rates and clinical progression over 10 years. Mult Scler 30(4–5):535–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNamara NB et al (2023) Microglia regulate central nervous system Myelin growth and integrity. Nature 613(7942):120–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Absinta M et al (2021) A lymphocyte–microglia–astrocyte axis in chronic active multiple sclerosis. Nature 597(7878):709–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paolicelli RC et al (2011) Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science 333(6048):1456–1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan SK et al (2023) Microglia ferroptosis is regulated by SEC24B and contributes to neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 26(1):12–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zrzavy T et al (2017) Loss of ‘homeostatic’ microglia and patterns of their activation in active multiple sclerosis. Brain 140(7):1900–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paolicelli RC et al (2022) Microglia States and nomenclature: A field at its crossroads. Neuron 110(21):3458–3483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarthy RC et al (2018) Inflammation-induced iron transport and metabolism by brain microglia. J Biol Chem 293(20):7853–7863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rathore KI, Redensek A, David S (2012) Iron homeostasis in astrocytes and microglia is differentially regulated by TNF-α and TGF‐β1. Glia 60(5):738–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen CE et al (2024) Inflammation-induced TRPV4 channels exacerbate blood–brain barrier dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflamm 21(1):72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida Y et al (2020) Iron leakage owing to blood–brain barrier disruption in small vessel disease CADASIL. Neurology 95(9):e1188–e1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams C (1988) Perivascular iron deposition and other vascular damage in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 51(2):260–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinmaurer A et al (2024) The relation between BTK expression and iron accumulation of myeloid cells in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol: p. e13240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Schwaiger C et al (2023) Dynamic induction of the myelin-associated growth inhibitor Nogo-A in perilesional plasticity regions after human spinal cord injury. Brain Pathol 33(1):e13098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bankhead P et al (2017) QuPath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep 7(1):16878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frischer JM et al (2015) Clinical and pathological insights into the dynamic nature of the white matter multiple sclerosis plaque. Ann Neurol 78(5):710–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bormann D et al (2023) Exploring the heterogeneous transcriptional response of the CNS to systemic LPS and Poly(I:C). Neurobiol Dis 188:106339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarthy KD, de Vellis J (1980) Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol 85(3):890–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bohlen CJ et al (2017) Diverse requirements for microglial survival, specification, and function revealed by Defined-Medium cultures. Neuron 94(4):759–773e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck J et al (1988) Increased production of interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor precedes clinical manifestation in multiple sclerosis: do cytokines trigger off exacerbations? Acta Neurol Scand 78(4):318–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X et al (2005) Cytokine toxicity to oligodendrocyte precursors is mediated by iron. Glia 52(3):199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X et al (2006) Cellular iron status influences the functional relationship between microglia and oligodendrocytes. Glia 54(8):795–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kenkhuis B et al (2022) Iron accumulation induces oxidative stress, while depressing inflammatory polarization in human iPSC-derived microglia. Stem Cell Rep 17(6):1351–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brás JP et al (2020) TNF-alpha-induced microglia activation requires miR-342: impact on NF-kB signaling and neurotoxicity. Cell Death Dis 11(6):415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kroner A et al (2014) TNF and increased intracellular iron alter macrophage polarization to a detrimental M1 phenotype in the injured spinal cord. Neuron 83(5):1098–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye J et al (2012) Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics 13:134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sayers EW et al (2022) Database resources of the National center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res 50(D1):D20–d26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boccazzi M et al (2021) The immune-inflammatory response of oligodendrocytes in a murine model of preterm white matter injury: the role of TLR3 activation. Cell Death Dis 12(2):166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Core Team R (2013) R., R: A language and environment for statistical computing

- 57.Allaire J, Boston (2012) MA 770(394):165–171 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wickham H et al (2023) Vaughan, D. dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation (R Package Version) 1.1.2) https://CRAN.R-project.org/web/packages/dplyr

- 59.Wickham H et al (2019) Welcome to the tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 4(43):1686 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Douglas Bates M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67(1):1–48 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lenth RV (2023) emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means

- 62.Hadley W (2016) Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer

- 63.Ortiz E et al (2004) Effect of manipulation of iron storage, transport, or availability on Myelin composition and brain iron content in three different animal models. J Neurosci Res 77(5):681–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kettenmann H et al (2011) Physiology of microglia. Physiol Rev 91(2):461–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Loughlin E et al (2018) Microglial phenotypes and functions in multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med 8(2):a028993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li JY et al (2009) Scara5 is a ferritin receptor mediating non-transferrin iron delivery. Dev Cell 16(1):35–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Truman-Rosentsvit M et al (2018) Ferritin is secreted via 2 distinct nonclassical vesicular pathways. Blood J Am Soc Hematol 131(3):342–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boven LA et al (2005) Myelin-laden macrophages are anti-inflammatory, consistent with foam cells in multiple sclerosis. Brain 129(2):517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reeves JA et al (2025) Association between paramagnetic rim lesions and pulvinar iron depletion in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 93:106187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morath DJ, Mayer-Pröschel M (2001) Iron modulates the differentiation of a distinct population of glial precursor cells into oligodendrocytes. Dev Biol 237(1):232–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Auderset L, Cullen CL, Young KM (2016) Low density lipoprotein-receptor related protein 1 is differentially expressed by neuronal and glial populations in the developing and mature mouse central nervous system. PLoS ONE 11(6):e0155878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poss P K.D., Tonegawa S. (1997) Reduced stress defense in Heme Oxygenase 1-deficient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94(20):10925–10930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheli VT et al (2020) Iron metabolism in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, implications for myelination and remyelination. ASN Neuro 12:1759091420962681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang G et al (2018) TLR7 (Toll-Like receptor 7) facilitates Heme scavenging through the BTK (Bruton tyrosine Kinase)-CRT (Calreticulin)-LRP1 (Low-Density lipoprotein receptor-Related Protein-1)-Hx (Hemopexin) pathway in murine intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 49(12):3020–3029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tolosano E et al (2010) Heme scavenging and the other facets of hemopexin. Antioxid Redox Signal 12(2):305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Auderset L et al (2020) Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) is a negative regulator of oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation in the adult mouse brain. Front Cell Dev Biology 8:564351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin J-P et al (2017) LRP1 regulates peroxisome biogenesis and cholesterol homeostasis in oligodendrocytes and is required for proper CNS Myelin development and repair. Elife 6:e30498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Popescu BF et al (2017) Pathogenic implications of distinct patterns of iron and zinc in chronic MS lesions. Acta Neuropathol 134(1):45–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pitt D et al (2010) Imaging cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis with ultra–high-field magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol 67(7):812–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hua Y et al (2006) Long-term effects of experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: the role of iron. J Neurosurg JNS 104(2):305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Torti SV, Torti FM (2021) CD63 orchestrates ferritin export. Blood. J Am Soc Hematol 138(16):1387–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yanatori I et al (2021) CD63 is regulated by iron via the IRE-IRP system and is important for ferritin secretion by extracellular vesicles. Blood 138(16):1490–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kumar S, Bandyopadhyay U (2005) Free Heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol Lett 157(3):175–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kolodziej MA et al (2014) Cerebrospinal fluid ferritin—unspecific and unsuitable for disease monitoring. Neurol Neurochir Pol 48(2):116–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.LeVine SM et al (1999) Ferritin, transferrin and iron concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients. Brain Res 821(2):511–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yanatori I et al (2010) Heme and non-heme iron transporters in non-polarized and polarized cells. BMC Cell Biol 11:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hochmeister S et al (2006) Dysferlin is a new marker for leaky brain blood vessels in multiple sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 65(9):855–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Choi S et al (2021) Blood-brain barrier breakdown in non-enhancing multiple sclerosis lesions detected by 7-Tesla MP2RAGE ∆T1 mapping. PLoS ONE 16(4):e0249973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hu H et al (2022) The heterogeneity of tissue destruction between iron rim lesions and non-iron rim lesions in multiple sclerosis: A diffusion MRI study. Multiple Scler Relat Disorders 66:104070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chomyk A et al (2024) Transcript profiles of microglia/macrophage cells at the borders of chronic active and subpial Gray matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 95(5):907–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van der Poel M et al (2019) Transcriptional profiling of human microglia reveals grey–white matter heterogeneity and multiple sclerosis-associated changes. Nat Commun 10(1):1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Williams R et al (2012) Pathogenic implications of iron accumulation in multiple sclerosis. J Neurochem 120(1):7–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li X et al (2022) Ferroptosis as a mechanism of oligodendrocyte loss and demyelination in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 373:577995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Smith AM, Dragunow M (2014) The human side of microglia. Trends Neurosci 37(3):125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1: Low magnification images of LFB, iron, TIM1, LRP1, and HEPH, including cell specific staining patterns and NG2 and LRP1 co-labeling. (a) Luxol fast blue (LFB) staining shows white matter of a control with an even myelin staining pattern. Turnbull’s blue-staining (TBB) shows a patchy pattern of iron in the WM with highest levels in oligodendrocytes (OLs) surrounding vessels. TIM1, LRP1, and HEPH are expressed in cells with an oligodendrocyte (OL) like morphology. White arrowheads indicate positive cells. (b) Figure panel depicts glial and foamy macrophage (MP) morphology with staining patterns in controls and MS cases. OLs and OL progenitor cells (OPCs) appear as small round cells with a collapsed cytoplasm, occasionally leading to a fried egg shaped morphology. Astrocytes (AC) contain a nucleus with loosely configured chromatin, an extensive cytoplasm with multiple longer processes. Microglia (MG) in the aged brain have an elongated tubular nucleus with a bipolar distribution of processes. Foamy MPs have a compact nucleus and a large round cell body with multiple granules. (c) In the white matter of a control, most cells showing clear LRP1 positivity were NG2 positive, suggesting an OPC restricted expression. White arrows indicate double positive cells.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.