Abstract

Background

Ticks are a type of hematophagous parasite, serving as critical vectors of pathogens that cause numerous human and animal diseases. Climate change has driven the geographical expansion of tick populations and increased the global transmission risk of tick-borne diseases. However, there has been a lack of comprehensive data on tick species distribution and their associated pathogen profiles in Xinjiang, China.

Methods

Ticks were collected from 19 sampling sites across nine regions in Xinjiang. The species were identified using both morphological and molecular biological methods. The presence of tick-borne bacterial and protozoan pathogens was detected through polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Finally, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses were performed to further characterize the identified ticks and pathogens.

Results

A total of 1093 ticks were collected and identified, representing four genera and nine species, with Hyalomma asiaticum being the dominant species. Haplotype diversity and genetic differentiation analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene of the dominant species demonstrated that the Hy. asiaticum population in Xinjiang exhibits high haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.734), low nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00403), and significant genetic differentiation (Fst = 0.19716). Pathogen detection using PCR revealed an infection rate of 9.3% for Anaplasma, 18.1% for Rickettsia, and 9.0% for piroplasms. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA sequences indicated that the Anaplasma genus identified in ticks comprised Anaplasma ovis, Anaplasma sp., and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Phylogenetic analysis based on the opmA gene showed that the Rickettsia genus identified in ticks included Rickettsia aeschlimannii, Rickettsia conorii, Rickettsia slovaca, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii, Rickettsia sp., Candidatus Rickettsia barbariae, and Candidatus Rickettsia jingxinensis. Similarly, phylogenetic analysis based on the 18S rRNA gene demonstrated that the piroplasms identified in ticks included Theileria annulata, Theileria ovis, Babesia bigemina, Babesia occultans, and Babesia sp. All gene sequences of the detected pathogens showed 99.8–100% identity with corresponding sequences deposited in GenBank.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Xinjiang harbors a rich diversity of tick species with a wide geographical distribution. Furthermore, the tick-borne pathogens in this region are complex and diverse. These results underscore the necessity of sustained and enhanced surveillance efforts targeting ticks and tick-borne diseases in this region

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13071-025-06857-1.

Keywords: Tick species, Tick-borne pathogens, Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia, Borrelia burgdorferi, Piroplasm, Xinjiang

Background

Ticks are a type of obligate hematophagous arthropod with a broad range of hosts and can parasitize birds, amphibians, and nearly all terrestrial vertebrates, including humans [1, 2]. Epidemiologically, they are recognized as the second most significant vector of human pathogens only next to mosquitoes and also primary vectors for zoonotic disease transmission in animals [3]. During blood-feeding, ticks inflict mechanical damage to the hosts and simultaneously transmit various pathogens, causing severe zoonotic infections and therefore posing substantial risks to public health and livestock industry [4]. Since 1982, 33 tick-associated pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and protozoa, have been identified in mainland China [5].

Rickettsia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia are gram-negative intracellular symbionts and significant tick-borne pathogens. Rickettsia spp. can be classified into four major groups: spotted fever group (SFG), typhus group (TG), ancestral group (AG), and transitional group (TRG). Among these groups, the TG and SFG harbor numerous clinically significant human pathogens. For instance, Rickettsia prowazekii and Rickettsia typhi in the TG group are causative agents of epidemic typhus and endemic typhus, respectively. The SFG group, as the largest taxon in the Rickettsia genus, mainly comprises pathogens responsible for Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsii), Japanese spotted fever (Rickettsia japonica), Mediterranean spotted fever (Rickettsia conorii), and African tick bite fever (Rickettsia africae) [6, 7]. Anaplasma and Ehrlichia, which belong to the Rickettsiales order and Anaplasmataceae family, carry various animal pathogens, such as Anaplasma marginale, Anaplasma centrale, Anaplasma bovis, Ehrlichia minasensis, and Ehrlichia canis [8, 9]. Notably, several of these pathogens exhibit zoonotic potential; for example, Anaplasma phagocytophilum causes human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), while Ehrlichia chaffeensis is associated with human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) [10]. A newly identified species, Anaplasma capra, represents newly emerging risks, as it can induce febrile syndromes with headache and fatigue in humans [11].

Piroplasmosis is a tick-borne protozoan disease caused by Babesia spp. and Theileria spp., posing significant threats to both domestic livestock (such as cattle, sheep, horses) and wildlife, with occasional zoonotic spillover to humans [12]. The clinical symptoms of piroplasmosis include anemia, hyperthermia, jaundice, and hemoglobinuria. In severe cases, it can lead to the death of the host, causing significant economic losses to the livestock industry [13, 14]. In China, piroplasmosis is endemic across diverse regions. Bovine theileriosis is prevalent in Xinjiang, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia. Concurrently, bovine babesiosis has been reported in 21 provinces of China, particularly in Xinjiang, Gansu, Inner Mongolia, Tibet, Henan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan [15].

Xinjiang is situated on the northwestern border of China and geographically central to the Eurasian continent, representing one of the China’s five major pastoral regions [16]. Owing to its vast territories, diverse geographical landscapes, and rich biodiversity in forest–grassland ecosystems, Xinjiang provides ideal habitats for ticks, making it a hotspot for tick species diversity (48 species across eight genera and two families, accounting for approximately one third of all tick species documented in China) and a high-risk zone for tick-borne diseases [17]. To date, various tick-borne diseases have been reported in Xinjiang, including tick-borne encephalitis (TBE), Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Lyme borreliosis, spotted fever group rickettsioses, and piroplasmosis [18]. The spread and prevalence of both traditional and newly emerging tick-borne diseases are further exacerbated by extensive border with eight countries and frequent international livestock trade in this region [19]. Since there has been limited research on tick-borne diseases in neighboring countries, it is crucial to conduct epidemiological surveys and continuous monitoring of tick-borne pathogens in Xinjiang for better disease prevention and control in this region. In this study, we collected ectoparasitic ticks from livestock farms across different ecoregions in Xinjiang to investigate the prevalence and genetic diversity of tick-borne bacterial and protozoan pathogens. The findings are expected to facilitate informed and targeted control of tick-borne diseases and alleviate zoonotic threats in this region.

Methods

Collection and species identification of tick samples

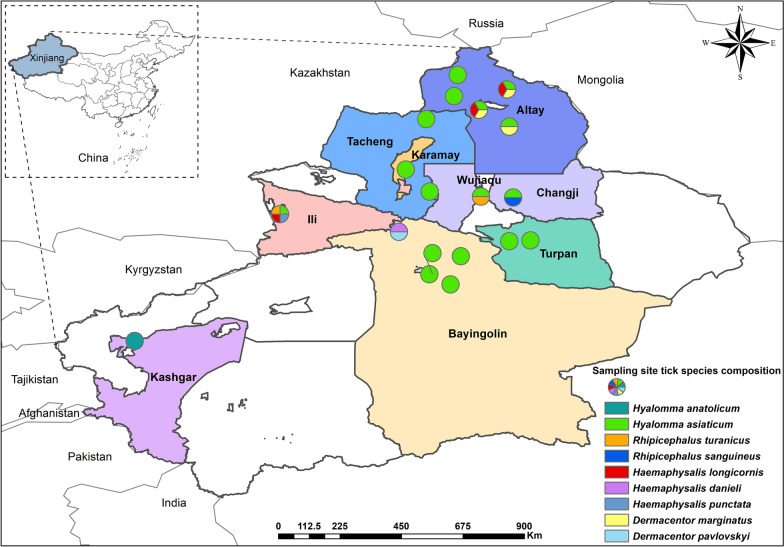

From May to June in 2023 and 2024, a total of 1093 adult ticks, including both blood-fed and unfed ticks, were randomly collected from the body surfaces of free-ranging mammalian hosts at 19 sampling sites across nine regions in Xinjiang, including Altay, Tacheng, Ili, Karamay, Changji, Wujiaqu, Turpan, Bayingolin, and Kashgar (Fig. 1). The ticks were collected from various body parts of the hosts, including the ears, periocular, neck, perineum, perianal area, and the base of the tail [20].

Fig. 1.

Ticks collected across various regions in Xinjiang, China. In the figure, circular markers indicate sampling sites, with each color corresponding to a distinct tick species

Tick species were initially identified morphologically under a stereo microscope (Nikon, Shanghai, China) with a taxonomic key on the basis of features such as basis capituli, scutum, anal groove, and peritreme [21, 22] and then confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (Additional File 1: Supplementary Table S1) [23].

DNA extraction

All the ticks were sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol, washed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2–7.4), dried on filter papers, and collected in individual sterile microtubes. Ticks were individually homogenized using Tissuelyser-24 (Jingxin, Shanghai, China) with 3.0 mm stainless steel beads in 200 μl of PBS. Genomic DNA was extracted from the homogenates using TIANamp Tissue and Blood Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) and stored at –20 ℃ according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens

Bacterial pathogens (Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia, and Borrelia burgdorferi) and protozoan pathogens (Theileria and Babesia) were screened using conventional PCR, nested PCR, or semi-nested PCR with the corresponding primers described in previous studies (Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1) [24–27]. Nuclease-free water was used as the negative control set in each PCR assay. PCR reactions were performed in a T100™ Thermal cycler (Applied Bio-Rad, CA, USA), using the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 ℃ for 3 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 ℃ for 15 s, annealing for 15 s and extension at 72 ℃ for 15 s/kb; and a final extension at 72 ℃ for 5 min. Annealing temperatures are listed in Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1. PCR products (5 μl) were analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. The target amplicons were sent to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) for bi-directional Sanger sequencing.

Sequence analysis

The obtained sequences were checked and assembled using Chromas 2.6.6 and SeqMan 7.1 (DNASTAR, Madison, Wisconsin, USA), which were then aligned with sequences deposited in GenBank database by BLASTn search to determine the nucleotide identities and similarities. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal X2 [28] and BioEdit 7.0.9.1 [29]. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm on the basis of the best-fit substitution model determined by MEGA 7.0 software with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess tree stability. The target gene sequences of ticks as well as Anaplasma spp., Rickettsia spp., Theileria spp., and Babesia spp. detected in ticks (Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S2) and different reference sequences in GenBank (Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S3) were used for genetic evolution analysis. Sarcoptes scabiei (accession no. AF387675.1) was used as an outgroup of the tick phylogenetic tree. R. conorii (accession no. L36107.1) was included in the tree of Anaplasma as the outgroup. To analyze the genetic diversity of the dominant tick species, DnaSP version 6.10.04 software was used to quantify the number of haplotypes (Hn) and calculate the haplotype diversity (Hd) and nucleotide diversity (π) [30]; PopART version 1.7 was used to construct a haplotype network [31]; furthermore, Arlequin version 3.5.2.2 was used to calculate the genetic differentiation index (F statistics, Fst); and a neutrality test was performed to obtain Fu’s Fs and Tajima’s D values [32].

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 software was used for statistical analysis. The difference in infection rate by Anaplasma, Rickettsia, and piroplasms among different regions was compared by Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) test. Significant differences were determined at P < 0.05.

Results

Identification of tick species

A total of 1093 ticks were collected and subjected to morphological and molecular identification, which were identified as four genera and nine species, namely Hyalomma anatolicum, Hyalomma asiaticum, Dermacentor marginatus, Dermacentor pavlovskyi, Rhipicephalus turanicus, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Haemaphysalis longicornis, Haemaphysalis punctata, and Haemaphysalis danieli. Hy. asiaticum (72.0%, 787/1093) was the dominant tick species, while Ha. danieli (0.4%, 4/1093) was the rarest species (Table 1). Among the nine regions sampled, the largest number of ticks was collected in the Altay region (37.2%, 407/1093); the smallest number of ticks was collected in the Kashgar region (2.4%, 26/1093); while the richest tick species were collected in the Ili region (Table 1).

Table 1.

Species identification and quantity statistics of ticks from nine regions in Xinjiang

| Region | Sampling site | Geographical coordinates (°N, °E) | Geographical inhabitants | Host | Tick species | Number | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude (m) | Habitat types | |||||||

| Kashgar | Kashgar | 39.5, 76.1 | 1267 | Desert, Gobi | Cattle | Hy. anatolicum | 26 | 26 |

| Bayingolin | Korlaa |

41.7, 85.9 41.7, 85.8 |

903–908 | Plain | Sheep | Hy. asiaticum | 63 | 151 |

| Yuli | 41.4, 86.2 | 889 | Desert, Gobi | Cattle | 42 | |||

| Hoxud | 42.3, 86.9 | 1122 | Montane grassland | Cattle, sheep | 30 | |||

| Hejing | 43.1, 84.8 | 2511 | Alpine frigid grassland | Sheep | Ha. danieli | 4 | ||

| D. pavlovskyi | 12 | |||||||

| Turpan | Toksuna |

42.8, 88.6 42.8, 88.5 |

134–138 | Desert steppe | Cattle | Hy. asiaticum | 115 | 115 |

| Wujiaqu | Wujiaqu | 44.2, 87.5 | 460 | Plain grassland | Cattle, sheep | Hy. asiaticum | 94 | 136 |

| R. turanicus | 42 | |||||||

| Changji | Fukang | 44.2, 88.6 | 580 | Plain grassland | Sheep | Hy. asiaticum | 44 | 50 |

| R. sanguineus | 6 | |||||||

| Karamay | Karamay | 45.1, 85.1 | 293 | Desert steppe | Cattle | Hy. asiaticum | 78 | 78 |

| Tacheng | Shawan | 44.4, 85.8 | 409 | Desert steppe | Cattle | Hy. asiaticum | 70 | 89 |

| Hefeng | 46.8, 85.7 | 1295 | Desert steppe | Sheep | 19 | |||

| Ili | Qapqal | 43.7, 80.9 | 890 | Mountain grassland | Sheep | Hy. asiaticum | 8 | 41 |

| R. turanicus | 17 | |||||||

| Ha. longicornis | 10 | |||||||

| Ha. punctata | 6 | |||||||

| Altay | Altay | 47.8, 88.4 | 897 | Mountain grassland | Cattle, sheep | Hy. asiaticum | 34 | 407 |

| Ha. longicornis | 1 | |||||||

| D. marginatus | 52 | |||||||

| Fuyun | 46.6, 88.5 | 656 | Meadow steppe | Hy. asiaticum | 41 | |||

| D. marginatus | 1 | |||||||

| Fuhai | 47.1, 87.5 | 499 | Composite area of river valley and oasis | Hy. asiaticum | 126 | |||

| Ha. longicornis | 11 | |||||||

| D. marginatus | 118 | |||||||

| Burqin | 47.9, 86.6 | 480 | Meadow steppe | Hy. asiaticum | 17 | |||

| Habahe | 48.3, 86.8 | 512 | Composite area of river valley and oasis | 6 | ||||

| Total | – | – | – | – | – | 1093 | ||

aKorla and Torkun each include two sampling sites

Detection of bacterial pathogens in ticks

Anaplasma and Rickettsia were detected in the ticks, while Ehrlichia or B. burgdorferi was not detected. Semi-nested PCR targeting the 16S rRNA gene revealed an overall Anaplasma infection rate of 9.3% (102/1093). Anaplasma infection was the most prevalent in the Kashgar region, while the least prevalent in the Turpan region (Table 2). There were statistically significant differences (χ2 = 97.217, df = 8, P < 0.01) in the prevalence of tick infection among different regions (Table 2). The amplified fragment size of the positive samples was 650 base pairs (bp).

Table 2.

Prevalence of tick-borne bacterial and piroplasmosis pathogens in ticks from nine regions of Xinjiang

| Region | Sampling site | Number of examined ticks | Number of infected ticks (%, 95% confidence interval (CI)) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piroplasms | Anaplasma | Rickettsia | |||

| Kashgar | Kashgar | 26 | 20 (76.9%) | 7 (26.9%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Bayingolin | Korla | 63 | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (15.9%) | 20 (31.7%) |

| Yuli | 42 | 2 (4.8%) | 12 (28.6%) | 14 (33.3%) | |

| Hoxud | 30 | 9 (30.0%) | 13 (43.3%) | 3 (10.0%) | |

| Hejing | 16 | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | |

| Turpan | Toksun | 115 | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (1.7%) | 7 (6.1%) |

| Wujiaqu | Wujiaqu | 136 | 1 (0.7%) | 5 (3.7%) | 35 (25.7%) |

| Changji | Fukang | 50 | 7 (14.0%) | 12 (24.0%) | 4 (8.0%) |

| Karamay | Karamay | 78 | 4 (5.1%) | 15 (19.2%) | 3 (3.8%) |

| Tacheng | Shawan | 70 | 2 (2.9%) | 6 (8.6%) | 1 (1.4%) |

| Hefeng | 19 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | |

| Ili | Qapqal | 41 | 4 (9.8%) | 6 (14.6%) | 7 (17.1%) |

| Altay | Altay | 87 | 11 (12.6%) | 2 (2.3%) | 26 (29.9%) |

| Fuyun | 42 | 5 (11.9%) | 4 (9.5%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Fuhai | 255 | 29 (11.4%) | 8 (3.1%) | 69 (27.1%) | |

| Burqin | 17 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Habahe | 6 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total | – | 1093 | 98 (9.0%, 7.3–10.7%) | 102 (9.3%, 7.6–11.1%) | 198 (18.1%, 15.8–20.4%) |

| Chi-squared | – | – | 175.870 | 97.217 | 60.988 |

| P-value | – | – | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

To detect Rickettsia, all tick samples were screened using semi-nested PCR targeting the ompA gene, and the results showed an overall infection rate of 18.1% (198/1093). The positive samples displayed an expected amplicon size of 533 bp. Notably, the prevalence of Rickettsia infection was the highest in the Kashgar region, whereas it was the lowest in the Turpan region (Table 2). Statistically significant differences (χ2 = 60.988, df = 8, P < 0.01) in infection rates were observed among various regions (Table 2).

Detection of piroplasms in ticks

Conventional PCR targeting the 18S rRNA gene showed that the overall prevalence of piroplasms in ticks across all regions was 9.0% (98/1093). The carriage rate of piroplasms in ticks from various regions followed a descending order of Kashgar (76.9%); Changji (14.0%); Altay (11.1%); Ili (9.8%); Bayingolin (8.6%); Karamay (5.1%); Tacheng (2.2%); Turpan (1.7%); and Wujiaqu (0.7%; Table 2). Statistical analysis indicated significant differences in piroplasm infection rates among different regions (χ2 = 175.870, df = 8, P < 0.01), as presented in Table 2. Positive samples exhibited an expected amplicon size of 1600 bp during PCR amplification.

Analysis of tick-borne pathogen infection status under the influence of different factors

To investigate the impact of blood-feeding status of ticks on the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens, the 1093 collected ticks were grouped into blood-fed ticks (n = 319) and unfed ticks (n = 774) according to their physiological feeding states. Pathogen detection revealed that the prevalences of Anaplasma spp., Rickettsia spp., and piroplasms were 10.3% (33/319); 21.3% (68/319); and 9.7% (31/319) in blood-fed ticks, while 8.9% (69/774); 16.8% (130/774); and 8.7% (67/774) in unfed ticks, respectively.

Chi-squared tests showed no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of Anaplasma (χ2 = 0.546, df = 1, P > 0.05), Rickettsia (χ2 = 3.112, df = 1, P > 0.05), or piroplasms (χ2 = 0.312, df = 1, P > 0.05) between blood-fed and unfed ticks (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pathogen infection prevalences in ticks across different blood-feeding status

| Hematophagous state | Number of examined ticks | Number of infected ticks (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piroplasms | Anaplasma | Rickettsia | ||

| Blood-fed | 319 | 31 (9.7%) | 33 (10.3%) | 68 (21.3%) |

| Unfed | 774 | 67 (8.7%) | 69 (8.9%) | 130 (16.8%) |

| Total | 1093 | 98 (9.0%) | 102 (9.3%) | 198 (18.1%) |

| Chi-squared | – | 0.312 | 0.546 | 3.112 |

| P-value | – | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 |

Given that different tick-borne pathogens typically rely on specific tick species as primary transmission vectors, we analyzed the correlation between tick species and pathogen prevalence. The results showed that Hy. asiaticum harbored the greatest variety of pathogens (11 species), whereas no pathogen was detected in Ha. danieli. Analysis of Anaplasma infection in different tick species revealed that A. ovis was detected in five tick species, with no significant differences in prevalence among different tick species (χ2 = 13.999, df = 8, P > 0.05). Anaplasma sp. was only found in Hy. anatolicum and Hy. asiaticum and exhibited significant differences in prevalence among different tick species (χ2 = 47.957, df = 8, P < 0.01). A. phagocytophilum was only detected in Hy. asiaticum (Table 4). Analysis of Rickettsia infection in different tick species showed that Rickettsia raoultii, Candidatus Rickettsia barbariae, and Candidatus Rickettsia jingxinensis were detected in multiple tick species; R. conorii, Rickettsia slovaca, and Rickettsia sp. were only found in single tick species. Except for Rickettsia sp., the infection rate of six Rickettsia species, including Rickettsia aeschlimannii and R. conorii, showed significant differences among different tick species (Table 5). Analysis of piroplasm infection in different tick species revealed that Theileria ovis was prevalent in four tick species; Theileria annulata was exclusively detected in Hyalomma spp.; and each of Babesia bigemina, Babesia occultans, and Babesia sp. was restricted to a single tick species. Significant differences were found in the infection rate of T. annulata, T. ovis, and B. occultans, while not in that of B. bigemina and Babesia sp. among different tick species (Table 6).

Table 4.

Anaplasma prevalences across different tick species

| Tick species | Number of examined ticks | Number of infected ticks (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. ovis | Anaplasma sp. | A. phagocytophilum | ||

| Hy. anatolicum | 26 | 0 | 7 (26.9) | 0 |

| Hy. asiaticum | 787 | 40 (5.1) | 37 (4.7) | 6 (0.8) |

| D. marginatus | 171 | 6 (3.5) | 0 | 0 |

| D. pavlovskyi | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R. turanicus | 59 | 3 (5.1) | 0 | 0 |

| R. sanguineus | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Ha. longicornis | 22 | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Ha. punctata | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ha. danieli | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1093 | 52 (4.8) | 44 (4.0) | 6 (0.5) |

| Chi-squared | – | 13.999 | 47.957 | 2.346 |

| P value | – | > 0.05 | < 0.01 | > 0.05 |

Table 5.

Rickettsia prevalences across different tick species

| Tick species | Number of examined ticks | Number of infected ticks (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. aeschlimannii | R. conorii | R. slovaca | R. raoultii | Rickettsia sp. | Candidatus R. barbariae |

Candidatus R. jingxinensis |

||

| Hy. anatolicum | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (15.4) |

| Hy. asiaticum | 787 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 28 (3.6) | 5 (0.6) | 0 | 82 (10.4) |

| D. marginatus | 171 | 0 | 0 | 7 (4.1) | 45 (26.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D. pavlovskyi | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 |

| R. turanicus | 59 | 0 | 11 (18.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (10.2) | 0 |

| R. sanguineus | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Ha. longicornis | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (13.6) | 0 | 2 (9.1) | 0 |

| Ha. punctata | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ha. danieli | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1093 | 2 (0.2) | 11 (1.0) | 7 (0.6) | 77 (7.0) | 5 (0.5) | 9 (0.8) | 87 (8.0) |

| Chi-squared | – | 89.942 | 194.740 | 37.986 | 120.732 | 1.953 | 98.111 | 32.772 |

| P value | – | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | > 0.05 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

Table 6.

Piroplasm prevalences across different tick species

| Tick species | Number of examined ticks | Number of infected ticks (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. annulata | T. ovis | B. bigemina | B. occultans | Babesia sp. | ||

| Hy. anatolicum | 26 | 20 (76.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hy. asiaticum | 787 | 30 (3.8) | 25 (3.2) | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (0.5) |

| D. marginatus | 171 | 0 | 13 (7.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D. pavlovskyi | 12 | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R. turanicus | 59 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 0 |

| R. sanguineus | 6 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ha. longicornis | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ha. punctata | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ha. danieli | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1093 | 50 (4.6) | 41 (3.8) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.4) |

| Chi-squared | – | 326.230 | 20.621 | 0.779 | 17.541 | 1.561 |

| P value | – | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | > 0.05 | 0.01–0.05 | > 0.05 |

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of tick species

All tick species were subjected to PCR amplification using specific primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene, yielding a 460 bp fragment consistent with the expected size of the 16S rRNA gene. Subsequent sequencing and BLASTn analysis in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database confirmed that the results were aligned with those of morphological identification.

Ticks collected from the Kashgar region were exclusively identified as Hy. anatolicum, exhibiting 100% identity with the Turkish strain (KR870971.1). In the Bayingolin region, the ticks included Hy. asiaticum, Ha. danieli, and D. pavlovskyi, showing 99.3–99.8% and 100% identity with the Hy. asiaticum strain from Kazakhstan (OR486027.1) and Xinjiang (MK530106.1, OR452926.1), respectively; 99.3% identity with the Chinese strain of Ha. danieli (NC_062065.1); and 99.1% identity with the Hebei strain of D. pavlovskyi (OK493294.1). Ticks from the Turpan region were all identified as Hy. asiaticum, with 99.8% identity to the Xinjiang strain (MG021188.1). In Wujiaqu, the ticks comprised Hy. asiaticum and R. turanicus, which displayed 99.1–99.5% and 100% identity with the Hy. asiaticum strain from Kazakhstan (OR486027.1) and Xinjiang (MG021188.1), respectively, and 99.3–100% identity with R. turanicus strains from Xinjiang (MT254805.1, KY583073.1). Ticks from Changji included Hy. asiaticum and R. sanguineus, with 99.5% and 100% identity to strains from Kazakhstan (OR486027.1) and Xinjiang (KU183525.1), respectively. Ticks from Karamay were all Hy. asiaticum, showing 99.5% identity to the Kazakhstan strain (OR486027.1). In Tacheng, all ticks were Hy. asiaticum, with 99.8–100% identity to the Xinjiang strain (MG021188.1). Ticks from Ili included Hy. asiaticum, R. turanicus, Ha. longicornis, and Ha. punctata, exhibiting 100%, 99.5%, 100%, and 99.8% identity to the strains from Kazakhstan (OR486027.1), Xinjiang (KY583073.1), Nanjing, and Xinjiang (MF002566.1), respectively. Finally, ticks from Altay comprised Hy. asiaticum, Ha. longicornis, and D. marginatus, with 99.5–99.8%, 100%, and 100% identity to the strains from Kazakhstan (OR486027.1), Nanjing (PP486235.1), and Kazakhstan (OR486023.1), respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA sequences classified the 48 sequences into five major clades, which corresponded to the Hyalomma, Dermacentor, Haemaphysalis (two subclades), and Rhipicephalus genera. Species within the same genus were clustered together, with clear distinction between different genera. Notably, Ha. danieli from Hejing County formed a distinct clade, suggesting significant evolutionary divergence within the Haemaphysalis genus (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of tick species based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Phylogenetic tree was conducted using the neighbor-joining method under the Tamura 3-parameter model. The robustness of the tree topology was assessed through bootstrap analysis with 1000 pseudoreplicates. In the figure, the purple, green, yellow, pink, red–brown, and blue regions represent species of the Hyalomma, Rhipicephalus Dermacentor, Haemaphysalis, Ixodes, and Argasidae genera, respectively. Outgroup taxa are labeled in blue text. Bootstrap values are indicated by blue dots on the branches, with dot size proportional to the bootstrap support value (larger dots indicate higher support)

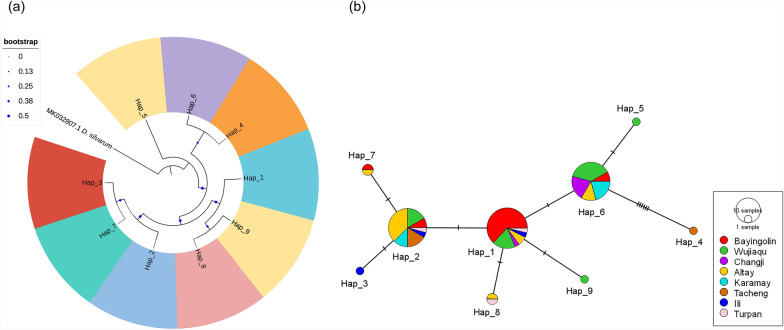

Haplotype diversity analysis of the 16S rRNA gene in Hy. asiaticum

Genetic diversity analysis of 83 mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene sequences from eight Hy. asiaticum populations (including 73 new sequences and 10 sequences retrieved from GenBank, whose detailed information is provided in Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S4) revealed nine distinct haplotypes. Among these haplotypes, five were shared haplotypes (Hap_1 to Hap_2, Hap_6 to Hap_8), while the other four were unique haplotypes (Hap_3 to Hap_5, Hap_9). The overall haplotype diversity (Hd) was 0.734, with a nucleotide diversity (π) of 0.00403. Population analysis showed that the Changji population exhibited the lowest haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.333), while the Turpan and Ili populations displayed the highest haplotype diversity (Hd = 1.000). The Changji population showed the lowest nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00113), whereas the Tacheng population had the highest nucleotide diversity (π = 0.01081; Table 7). These results indicated that the eight populations have high haplotype diversity but relatively low nucleotide diversity, which is a characteristic of tick populations with high genetic variability. Tajima’s D tests revealed negative values for all populations except for the population from Karamay (Table 7), suggesting that the seven populations have undergone expansion, while the population from Karamay may have been restricted by a bottleneck effect.

Table 7.

Population diversity parameters of Hy. asiaticum

| Population | No. | Hn | Shared haplotype | Private haplotype | Hd | π | Tajima’s D | Fu’s Fs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayingolin | 22 | 4 | Hap_1, Hap_2, Hap_6, Hap_7 | – | 0.403 | 0.00173 | −0.98105 | −1.428 |

| Turpan | 3 | 3 | Hap_1, Hap_2, Hap_8 | – | 1.000 | 0.00450 | NA | −1.216 |

| Wujiaqu | 20 | 5 | Hap_1, Hap_2, Hap_6 | Hap_5, Hap_9 | 0.726 | 0.00359 | −0.16515 | −0.958 |

| Changji | 6 | 2 | Hap_1, Hap_6 | − | 0.333 | 0.00113 | −0.93302 | −0.003 |

| Karamay | 8 | 2 | Hap_2, Hap_6 | − | 0.536 | 0.00362 | 1.44880 | 2.083 |

| Tacheng | 5 | 2 | Hap_2 | Hap_4 | 0.400 | 0.01081 | −1.17432 | 3.679 |

| Ili | 3 | 3 | Hap_1, Hap_2 | Hap_3 | 1.000 | 0.00450 | NA | −1.216 |

| Altay | 16 | 5 | Hap_1, Hap_2, Hap_6, Hap_7, Hap_8 | – | 0.667 | 0.00363 | −0.33859 | −1.243 |

| Total | 83 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 0.734 | 0.00403 | −1.50200 | −2.467 |

No. number of isolates, Hn number of haplotypes, Hd haplotype diversity, π nucleotide diversity, NA test was not applied because the sample size was less than four

Haplotype evolutionary analysis revealed that the eight Hy. asiaticum populations in Xinjiang did not form independent lineages, as their phylogenetic relationships exhibited a cross-nested pattern and no significant geographic differentiation (Fig. 3a). The haplotype network analysis also demonstrated that haplotypes from the eight populations did not form distinct lineage structures and were interwoven with each other. Hap_1 occupied the central position in the network, with other haplotypes being distributed peripherally as derived haplotypes, indicating that Hap_1 is a stable haplotype formed during the evolutionary history of Hy. asiaticum (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Haplotype phylogenetic tree (a) and network (b) of Hy. asiaticum based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. a Hap_5 and Hap_9, which were derived from the same population, are indicated by the same color, while other haplotypes, representing distinct populations, are displayed in different colors. b Haplotype network depicting the distribution of haplotypes across populations, with each color corresponding to a unique population. The size of each circle is proportional to the frequency of the respective haplotype. Transverse lines on the network represent a gene mutation site

Genetic differentiation of the 16S rRNA gene in Hy. asiaticum

The genetic differentiation index (Fst) among the eight populations of Hy. asiaticum in Xinjiang ranged from −0.12113 to 0.63889. The genetic differentiation was the weakest between the Turpan and Altai populations, while it was the strongest between the Changji and Ili populations (Table 8).

Table 8.

Genetic differentiation coefficients among populations of Hy. asiaticum

| Population | Bayingolin | Altay | Tacheng | Ili | Wujiaqu | Changji | Karamay | Turpan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayingolin | 0.00000 | |||||||

| Altay | 0.22134 | 0.00000 | ||||||

| Tacheng | 0.38085 | 0.04920 | 0.00000 | |||||

| Ili | 0.33425 | −0.06040 | −0.12113 | 0.00000 | ||||

| Wujiaqu | 0.15476 | 0.17778 | 0.26438 | 0.25626 | 0.00000 | |||

| Changji | 0.52235 | 0.44512 | 0.38030 | 0.63889 | 0.05927 | 0.00000 | ||

| Karamay | 0.30730 | 0.13041 | 0.14038 | 0.22499 | −0.04101 | 0.08682 | 0.00000 | |

| Turpan | 0.07899 | −0.01964 | 0.14038 | −0.09091 | 0.13859 | 0.55172 | 0.17799 | 0.00000 |

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) revealed that 19.7% of the total genetic variations occurred among populations, while 80.3% of them were variations within populations (Table 9), indicating that the genetic diversity within populations is significantly greater than that between populations.

Table 9.

Analysis of molecular variance among populations of Hy. asiaticum

| Source of variation | df | Sum of squares | Variance components |

Percentage variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among populations | 7 | 11.691 | 0.12172 | 19.7 |

| Within populations | 75 | 37.176 | 0.49568 | 80.3 |

| Total | 82 | 48.867 | 0.61741 | – |

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of various tick-borne pathogens

For the Anaplasma genus, three species (A. ovis, Anaplasma sp., and A. phagocytophilum) were identified in the ticks. In the Kashgar, Bayingolin, and Turpan regions, all detected Anaplasma species were identified as Anaplasma sp., with a 100% identity to Anaplasma sp. from Xinjiang (KJ410247.1). The Anaplasma species in tick samples from the Wujiaqu, Changji, Karamay, Tacheng, and Altay regions were identified as A. ovis. Notably, the A. ovis found in Karamay demonstrated 99.8% identity with the Qinghai strain (OR214930.1), while those from other regions exhibited 99.8–100% identity with the Chinese strain (KX579073.1). Furthermore, ticks from the Ili region were found to harbor Anaplasma, which was identified as A. phagocytophilum, with a 100% identity to the Taiwanese strain (OL690560.1). Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences from Anaplasma species with R. conorii as the outgroup revealed distinct clustering patterns. The sequences of A. ovis, A. phagocytophilum, and Anaplasma sp. formed distinct monophyletic clades with their respective reference sequences from GenBank. Notably, the geographical variants of A. ovis diverged into sister clades, demonstrating potential genetic differentiation among distinct geographical populations (Fig. 4).

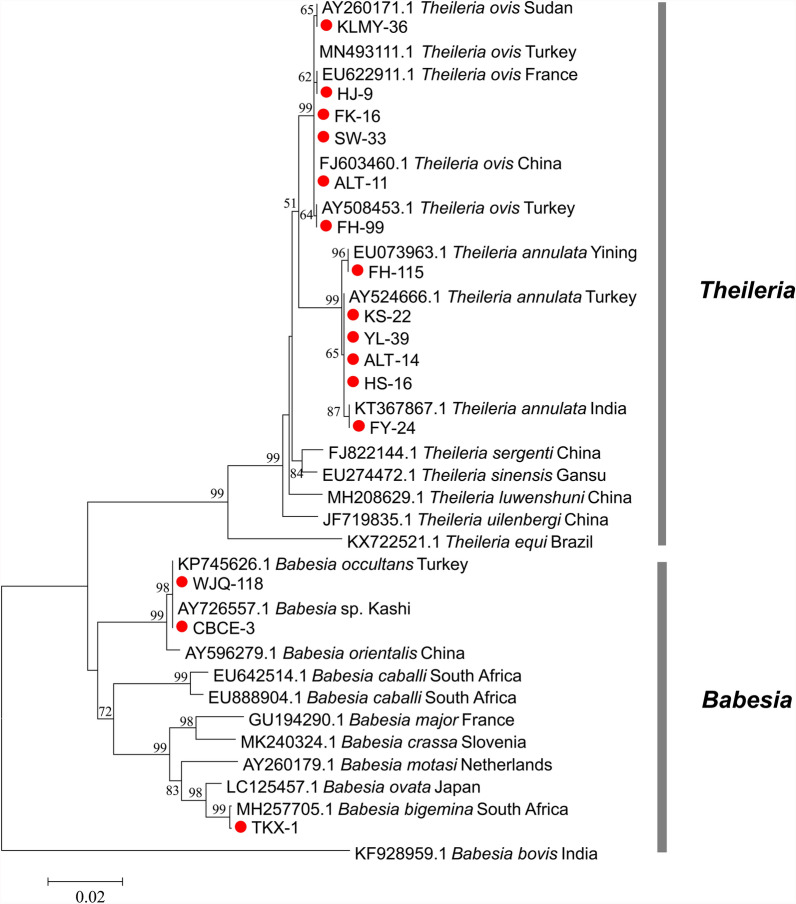

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of piroplasms based on 18S rRNA gene sequences. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method under the Tamura–Nei parameter model. Sequences obtained from this study are highlighted with red circles in the tree

For Rickettsia, seven species were identified in ticks collected from various regions of Xinjiang, including R. aeschlimannii, R. conorii, R. slovaca, R. conorii subsp. raoultii, Rickettsia sp., Candidatus R. barbariae, and Candidatus R. jingxinensis. In the Kashgar region, Candidatus R. jingxinensis was detected, which exhibited 99.8% nucleotide identity with the Indian strain (MN463686.1). In the Bayingolin region, multiple Rickettsia species were identified, including R. aeschlimannii, R. conorii subsp. raoultii, Candidatus R. barbariae, and Candidatus R. jingxinensis, all of which displayed 100% identity with their respective reference strains, namely the Russian strain of R. aeschlimannii (PP431067.1), the Russian strain of R. conorii subsp. raoultii (OQ723938.1), the Kashi strain of Candidatus R. barbariae (OM475678.1), the Indian strain of Candidatus R. jingxinensis (MN463686.1), and the Chinese strain of Candidatus R. jingxinensis (OP776196.1). In the Turpan region, Candidatus R. jingxinensis was detected, which showed a 100% identity with the Indian strain (MN463686.1). In Wujiaqu City, R. conorii, Candidatus R. barbariae, and Candidatus R. jingxinensis were identified, with 100% identity to the Xinjiang strain of R. conorii (MF002512.1); the Kashi strain of Candidatus R. barbariae (OM475678.1); and the Indian strain of Candidatus R. jingxinensis (MN463686.1). In the Changji region and Karamay City, all Rickettsia species were identified as Candidatus R. jingxinensis, which exhibited 99.8–100% identity with the Indian strain (MN463686.1). In the Tacheng region, R. conorii subsp. raoultii was detected, showing 100% identity with the Turkish strain (PP998265.1). In the Ili region, a diverse array of Rickettsia species was identified, including R. aeschlimannii, R. conorii subsp. raoultii, Candidatus R. barbariae, and Candidatus R. jingxinensis, all of which demonstrated 100% identity with their reference strains from various regions, including the Russian strain of R. aeschlimannii (PP431067.1), the Turkish strain of R. conorii subsp. raoultii (PP998265.1), the Chinese strain of R. conorii subsp. raoultii (PP117785.1), the Kashi strain of Candidatus R. barbariae (OM475678.1), and the Indian strain of Candidatus R. jingxinensis (MN463686.1). In Altay, R. slovaca, Rickettsia sp., Candidatus R. barbariae, Candidatus R. jingxinensis, and R. conorii subsp. raoultii were detected, where the former four species had 100% identity to the Italian strain of R. slovaca (HM161786.1), the Chinese strain of Rickettsia sp. (AY093696.1), the Kashi strain of Candidatus R. barbariae (OM475678.1), and the Chinese strain of Candidatus R. jingxinensis (OP776196.1), respectively, while R. conorii subsp. raoultii showed 100% identity to the Turkish strain (PP998265.1), the Heilongjiang strain (MH212184.1), the Chinese strain (PP117785.1), and the Russian strain (OQ723938.1). The phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of the opmA gene of Rickettsia revealed that the seven Rickettsia species obtained in this study were clustered in the same clades with their corresponding reference strains, and the bootstrap support values ranged from 74.0% to 100%. Notably, the R. conorii subsp. raoultii identified in this study formed a clade with R. raoultii, while exhibiting a distant phylogenetic relationship with R. conorii. The Chinese strain of R. conorii subsp. raoultii formed a sister clade with strains from other geographical origins, suggesting significant genetic differentiation among populations of this subspecies from different regions (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of Anaplasma based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method under the Kimura two-parameter model. Red triangles indicate sequences obtained from this study

For piroplasms, based on the 18S rRNA gene, the 98 piroplasm-positive tick samples were infected with five piroplasm species (T. annulata, T. ovis, B. bigemina, B. occultans, and Babesia sp.). In the Kashgar region, the detected piroplasms were identified as T. annulata, which showed a 100% identity with the Turkish strain of T. annulata (AY524666.1). In the Bayingolin region, the detected piroplasms included T. annulata and T. ovis, both of which showed a 100% identity to the Turkish strain of T. annulata (AY524666.1) and the French strain of T. ovis (EU622911.1), respectively. In the Turpan region, B. bigemina was detected in the ticks, which shared 99.9% identity with the South African strain of B. bigemina (MH257705.1). In Wujiaqu City, ticks contained B. occultans, which showed 100% identity with the Turkish strain of B. occultans (KP745626.1). In the Changji region, Karamay City, and Tacheng region, the detected piroplasms were all identified as T. ovis, displaying 100% identity with the Turkish strain (MN493111.1), the Sudanese strain (AY260171.1), and the Turkish strain (MN493111.1), respectively. In the Ili region, ticks were found to harbor Babesia sp., exhibiting 100% identity with Kashi strain (AY726557.1). Finally, ticks in the Altay region showed the presence of both T. annulata and T. ovis, with T. annulata showing 100% identity to the Turkish strain (AY524666.1), the Yining strain (EU073963.1), and the Indian strain (KT367867.1); and T. ovis showing 100% identity to the Chinese strain (FJ603460.1) and the Turkish strain (AY508453.1). Phylogenetic analysis based on 18S rRNA gene sequences of piroplasm species revealed that the five piroplasm species identified in this study were clustered into monophyletic clades together with their corresponding reference strains. The tree topology could be divided into three major clades: clade I, which exclusively comprises a Theileria species, including T. annulata and T. ovis obtained in this study, along with reference sequences of T. annulata, T. ovis, and other Theileria spp. from the GenBank; clade II, which encompasses Babesia species, including B. bigemina, Babesia sp., and B. occultans identified in this study, as well as reference strains of B. bigemina, Babesia sp., B. occultans, and other Babesia spp. from GenBank; and clade III, which is represented solely by the B. bovis Indian reference strain. This pronounced segregation underscored substantial genetic divergence between the Theileria and Babesia genera (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of Rickettsia based on ompA gene sequences. The phylogenetic tree was performed using the neighbor-joining method under the Tamura three-parameter model. Red diamonds indicate sequences obtained from this study

Discussion

Xinjiang is characterized by a high diversity of ticks, with the recording of 48 species across two families and eight genera since the initiation of tick fauna surveys in the 1950 s [33]. About three decades ago, I. persulcatus, D. nuttalli, Hy. asiaticum, D. marginatus, and D. niveus were dominant in the tick communities [34]. However, there have been dynamic shifts in prevalent tick species in recent decades. Initial surveys across 14 northern counties revealed that Hy. asiaticum, Ha. punctata, D. nuttalli, D. marginatus, and R. turanicus are predominant ticks infesting livestock [35]. Subsequent expansion of the scope to 35 counties (particularly border areas) revealed a distinct dominance of R. turanicus, D. niveus, Hy. asiaticum, and D. marginatus in domestic animals [17]. More recently, a comprehensive tick distribution dataset, which involved 108 counties and was synthesized from literature databases and historical records, identified Hy. asiaticum, R. turanicus, D. marginatus, and Ha. punctata as currently predominant tick species [33]. In this study, the 1093 ticks collected from 19 sampling sites across nine regions of Xinjiang were classified into nine species spanning four genera. Hy. asiaticum (72.0%, 787/1,093) was identified as the dominant species, followed by D. marginatus (15.6%, 171/1,093) and R. turanicus (5.4%, 59/1,093), which is slightly different from previous reports. Hy. asiaticum was collected in all regions except for Kashgar in this study, indicating that there is a wide distribution of this tick species in the Xinjiang region. This finding is consistent with earlier reports on the presence of Hy. asiaticum in the Junggar Basin, eastern Xinjiang basins (Yanqi, Turpan, Hami), the Tarim Basin, and parts of northern Xinjiang [36], suggesting minimal changes in its geographic distribution. Conversely, D. marginatus was only collected in the Altai region in this study, which contrasts with previous reports of its widespread distribution in the Tianshan Mountains, the Ili River Valley, the Altai Mountains, the Junggar Basin, and the Tarim Basin [37]. R. turanicus was detected in Wujiaqu and Ili, and its primary distribution was historically concentrated in the Tarim Basin and parts of the Tianshan Mountains and Ili River Valley [17]. However, recent findings in Fukang, Jimsar, Changji, Hutubi [38], and the Sixth Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps [39] have suggested an expanding trend of the geographic range for this species. Notably, Ha. longicornis—a species widely distributed across Asia and the Pacific, including China, Russia, South Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and the South Pacific Islands [40], was detected in Ili and Altai. This species was previously reported in China’s northern and central provinces [41] and had only one prior record in Xinjiang (Changji) [42]. Its expanded detection signals a potential trend of northward spread of this species in Xinjiang. These findings highlight the shifting patterns of dominant tick species and their geographic distribution across Xinjiang. Given the role of ticks as vectors for pathogens, such spatial dynamics may drive the spread of tick-borne diseases. Hence, continuous surveillance of tick distribution and population trends is critical for mitigating public health risks associated with these arthropod-borne pathogens.

Hyalomma asiaticum is the dominant tick species in Xinjiang widely reported across the region [33–36]. However, there are still critical knowledge gaps regarding its haplotype diversity, genetic differentiation, and population expansion dynamics. Here, we analyzed the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene sequences from eight Hy. asiaticum populations in Xinjiang to assess their genetic diversity and population structure. The results revealed high haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.734) and low nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00403) across the eight populations. According to the genetic diversity classification by Grant et al. [43], these populations are characterized by high haplotype diversity and low nucleotide diversity, indicating a stable genetic structure. This pattern is in line with the findings of Zhu et al. [44] on the genetic diversity of D. niveus in Xinjiang. The observed high haplotype diversity suggests that these populations have undergone long-term development and evolution, resulting in the formation of a large and stable population. Genetic differentiation index (Fst) and genetic distance are essential metrics for evaluating the population divergence. Theoretically, the Fst values range from −1 to 1, with a value closer to zero indicating lower differentiation between populations [45]. In this study, the Fst values among the eight Hy. asiaticum populations ranged from −0.12113 to 0.63889, indicating that most populations have moderate-to-high genetic differentiation. Notably, the populations in Turpan and Ili showed moderate-to-high differentiation from those in other regions, which may be attributable to limited sample sizes (Table 7). Conversely, differentiation between other populations may stem from geographic isolation caused by the mountainous terrain of Xinjiang, which restricts the flow of genes.

Climate change tends to drive the geographic expansion of tick populations and increases global transmission risk of tick-borne diseases. However, there has been rather limited research on tick-borne pathogens in northwest China [35]. In this study, we conducted surveillance on tick-borne bacteria and piroplasms in ticks collected from 19 sampling sites in Xinjiang, northwest China. The results revealed an overall prevalence of 9.3% (102/1093) for Anaplasma, 18.1% (198/1093) for Rickettsia, and 9.0% (98/1093) for piroplasms. The high prevalence rate of Rickettsia aligns with prior reports (10.59%) for the southern edge of the Gurbantünggüt Desert in northern Xinjiang [46]. Three Anaplasma species, seven Rickettsia species, and five piroplasm species were identified. Among the identified Anaplasma species, A. ovis was the most prevalent, which was detected in ticks from Altay, Tacheng, Karamay, Changji, and Wujiaqu. Anaplasma ovis, which was first identified in sheep in 1912 [47], has been recognized as a potential zoonotic pathogen [48]. In China, A. ovis has a wide distribution and infects various animal hosts [49, 50]. While earlier studies have failed to detect A. ovis in D. nuttalli and D. marginatus ticks from 11 Xinjiang counties [51], subsequent molecular studies confirmed its presence in Hy. anatolicum, D. nuttalli, and D. marginatus [19]. This study further expanded the range of its vectors to include Hy. asiaticum, R. turanicus, and D. marginatus. R. raoultii was predominant among the detected Rickettsia species. R. raoultii is a novel species within the Rickettsia genus and was first identified in Dermacentor ticks in Russia and France in 2008 [52]. Human infections caused by R. raoultii have been reported globally [53]. In China, R. raoultii was first detected in Xinjiang in 2012 [54], with subsequent reports in D. marginatus from Habahe County (17.6%) in 2016 [55] and in D. marginatus and D. silvarum from Zhaosu and Hejing Counties (36.8% prevalence in Hejing) in 2021 [56]. Our detection of R. raoultii in multiple tick species across Altay, Tacheng, Ili, and Bayingolin, highlights the need for further studies to assess its risk level and prevent human infections. For piroplasms, T. ovis was the dominant species, which is currently restricted to Xinjiang, and its primary vector is Hy. anatolicum [57]. A survey in 2017 found that T. ovis is the predominant Theileria species infecting sheep in southern Xinjiang [58], and its nucleic acid was detected in R. sanguineus, Ha. punctata, and Hy. rufipes in 2022 [59], suggesting its potential emergence as a major Theileria species in this region. Notably, we detected the nucleic acid of B. occultans in ticks, a species rarely reported in China. Since its first detection in Hy. asiaticum ticks from Alashankou on the China–Kazakhstan border in 2016 [60], B. occultans has been detected in D. nuttalli from Jimunai County; Hy. anatolicum from Artux City; Hy. asiaticum from Fuyun and Burqin Counties; and D. marginatus from Tacheng City [59, 61]. Our discovery of B. occultans in R. turanicus from Wujiaqu indicates the expansion of both its vector range and geographic distribution, suggesting necessity of strengthening surveillance on B. occultans.

However, this study still has several limitations that should be noted. First, the sample sizes for certain tick species and specific regions were small, which may restrict the comprehensive detection of tick-borne pathogens and the comparative analysis of pathogen prevalence across different areas. Second, we did not collect animal blood samples to correlate the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens detected with potential host infections. For instance, while B. occultans was detected in ticks collected from sheep, the positive PCR results could not distinguish whether the pathogen originated from degraded sheep blood in the tick gut or from an established B. occultans infection within the tick. Therefore, the role of ticks in the transmission of B. occultans requires further investigation.

Conclusions

This study elucidates the diversity and distribution of tick species across nine regions in Xinjiang, China and identifies the presence and infection status of multiple tick-borne pathogens. Furthermore, it provides preliminary evidence for the genetic differentiation and population expansion of distinct Hy. asiaticum populations in this region. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the epidemiology of ticks and tick-borne pathogens, offering a foundation for future research on them and targeted control strategies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used for tick species identification and screening of tick-borne pathogens. Table S2. Sequencing data obtained in this study. Table S3. Reference sequence information used for phylogenetic tree construction in the study. Table S4. Reference sequence information for haplotype phylogenetic tree construction of Hy. asiaticum. Fig. S1. Phylogenetic analysis of tick species based on 16S rRNA gene sequences.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the staff of the Xinjiang Academy of Animal Husbandry, the Fukang Agricultural and Rural Bureau, and Urumqi County Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Station for their invaluable assistance and support in the collection of tick samples.

Abbreviations

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- SFG

Spotted fever group

- TG

Typhus group

- AG

Ancestral group

- TRG

Transitional group

- HGA

Human granulocytic anaplasmosis

- HME

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis

- TBE

Tick-borne encephalitis

- CCHF

Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- NJ

Neighbor-joining

- Hn

Number of haplotypes

- Hd

Haplotype diversity

- π

Nucleotide diversity

- Fst

F statistics

- AMOVA

Analysis of molecular variance

- χ2

Chi-squared

- TBPs

Tick-borne pathogens

Author contributions

Conceptualization—Bingjie Wang, Junlong Zhao, and Lan He. Data curation—Bingjie Wang. Formal analysis—Bingjie Wang, Dongfang Li, Lan He, and Junlong Zhao. Funding acquisition—Junlong Zhao. Investigation—Bingjie Wang, Zhiqiang Liu, Shiying Zhu, Jinchao Zhang, Wenwen Qi, and Jianyu Wang. Methodology—Bingjie Wang, Zhiqiang Liu, Lan He, and Junlong Zhao. Writing—original draft preparation—Bingjie Wang. Writing—review and editing—Lan He and Junlong Zhao.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1801202). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University. Written informed consent was obtained from herders and farm owners prior to sampling. All procedures strictly adhered to the noninvasive principle, ensuring that host animals (cattle and sheep) experienced no additional harm or stress during the process. Ticks were collected solely through superficial examination and mechanical removal from the epidermis of the animal.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lan He, Email: helan@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Junlong Zhao, Email: zhaojunlong@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ghai RR, Mutinda M, Ezenwa VO. Limited sharing of tick-borne hemoparasites between sympatric wild and domestic ungulates. Vet Parasitol. 2016;226:167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beati L, Klompen H. Phylogeography of ticks (Acari: Ixodida). Annu Rev Entomol. 2019;64:379–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Fuente J, Estrada-Pena A, Venzal JM, Kocan KM, Sonenshine DE. Overview: ticks as vectors of pathogens that cause disease in humans and animals. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6938–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang LQ, Liu K, Li XL, Liang S, Yang Y, Yao HW, et al. Emerging tick-borne infections in mainland China: an increasing public health threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1467–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanton LS. The Rickettsioses: a practical update. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:213–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillespie JJ, Williams K, Shukla M, Snyder EE, Nordberg EK, Ceraul SM, et al. Rickettsia phylogenomics: unwinding the intricacies of obligate intracellular life. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao HQ, Liu PP, Xue F, Lu M, Qin XC, Li K. Molecular detection and identification of Candidatus Ehrlichia Hainanensis, a novel Ehrlichia species in rodents from Hainan Province, China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2021;34:1020–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu M, Tian J, Zhao H, Jiang H, Qin X, Wang W, et al. Molecular survey of vector-borne pathogens in ticks, sheep keds, and domestic animals from Ngawa, Southwest China. Pathogens. 2022;11:606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail N, McBride JW. Tick-borne emerging infections: Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:317–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Zheng YC, Ma L, Jia N, Jiang BG, Jiang RR, et al. Human infection with a novel tick-borne Anaplasma species in China: a surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:663–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malgwi SA, Ogunsakin RE, Oladepo AD, Adeleke MA, Okpeku M. A forty-year analysis of the literature on Babesia infection (1982–2022): a systematic bibliometric approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:6156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Florin-Christensen M, Suarez CE, Rodriguez AE, Flores DA, Schnittger L. Vaccines against bovine babesiosis: where we are now and possible roads ahead. Parasitology. 2014;141:1563–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onyiche TE, Suganuma K, Igarashi I, Yokoyama N, Xuan XN, Thekisoe O. A review on equine piroplasmosis: epidemiology, vector ecology, risk factors, host immunity, diagnosis and control. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin H, Lu WS, Luo JX. Babesiosis in China. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1997;29:11S-15S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takada N, Masuzawa T, Ishiguro F, Fujita H, Kudeken M, Mitani H, et al. Lyme disease Borrelia spp. in ticks and rodents from Northwestern China. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5161–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng JL, Jiang MM, Yang MH, Bo XW, Zhao SS, Zhang YY, et al. Tick distribution in border regions of Northwestern China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10:665–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu ZJ, Liu JZ. Progress in research on tick-borne diseases and vector ticks. J Appl Entomol. 2015;52:1072–81. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li YC, Wen XX, Li M, Moumouni PFA, Galon EM, Guo QY, et al. Molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens harbored by ticks collected from livestock in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11:101478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Wang YM, Yang GL, Liu HY, Xin Z. Ticks and tick-borne novel bunyavirus collected from the natural environment and domestic animals in Jinan city, East China. Exp Appl Acarol. 2016;68:213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor M, Coop R, Wall R. Veterinary parasitology. 4th ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell Publication; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker AR, Bouattour A, Camicas JL, Estrada-Pena A, Horak IG, Latif AA, et al. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa: a guide to identification of species. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh. 2003.

- 23.Black WC, Piesman J. Phylogeny of hard- and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10034–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen BH, Cao WC, Pan H. Ehrlichiae and ehrlichial diseases in china. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;990:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balayeva NM, Eremeeva ME, Ignatovich VF, Rudakov NV, Reschetnikova TA, Samoilenko IE, et al. Biological and genetic characterization of Rickettsia sibirica strains isolated in the endemic area of the north Asian tick typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:685–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu CY, Jiang BG, Liu W, Zhao QM, Wu XM, Zhang PH, et al. Presence of pathogenic Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks and rodents in Zhejiang, South-East China. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:980–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oosthuizen MC, Zweygarth E, Collins NE, Troskie M, Penzhorn BL. Identification of a novel Babesia sp. from a sable antelope (Hippotragus niger Harris, 1838). J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2247–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alzohairy MA. BioEdit: an important software for molecular biology. GERF Bull Biosci. 2011;21:60–1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leigh JW, Bryant D. PopART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol Evol. 2015;6:1110–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:564–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma R, Li CF, Gao A, Jiang N, Li J, Hu W, et al. Tick species diversity and potential distribution alternation of dominant ticks under different climate scenarios in Xinjiang, China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18:e0012108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ni J, Lin HL, Xu XF, Ren QY, Aizezi MLK, Luo J, et al. Coxiella burnetii is widespread in ticks (Ixodidae) in the Xinjiang areas of China. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YZ, Mu LM, Zhang K, Yang MH, Zhang L, Du JY, et al. A broad-range survey of ticks from livestock in Northern Xinjiang: changes in tick distribution and the isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu EC, Hu ZX, Mi XY, Li CS, He WW, Gan L, et al. Distribution prediction of Hyalomma asiaticum (Acari: Ixodidae) in a localized region in Northwestern China. J Parasitol. 2022;108:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang GL, Zheng Z, Sun X, Liu XM, Liu R, Li HL. A survey of tick species and its distribution with the landscape structure in Xinjiang. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2016;27:432–5. 10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2016.05.003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu ZQ. Geographical distribution and molecular characteristics of ticks and molecular detection of important tick-borne pathogens in northern Xinjiang. Shihezi: Shihezi University. 2019. 10.27332/d.cnki.gshzu.2019.000002.

- 39.Zhao CX, Wu T, Liu XP, Wu J. Investigation of tick species and their carrying African swine fever virus in the Sixth Division of the Corps. Anim Husb Vet Med. 2022;54:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao L, Li J, Cui XM, Jia N, Wei JT, Xia LY, et al. Distribution of Haemaphysalis longicornis and associated pathogens: analysis of pooled data from a China field survey and global published data. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4:320–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang XJ, Chen Z, Liu JZ. The valid genus and species names of ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Argasidae, Ixodidae) in China. J Hebei Norm Univ (Nat Sci). 2008;4:529–33. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao GP, Wang YX, Fan ZW, Ji Y, Liu MJ, Zhang WH, et al. Mapping ticks and tick-borne pathogens in China. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant W, Bowen B. Shallow population histories in deep evolutionary lineages of marine fishes: insights from sardines and anchovies and lessons for conservation. J Hered. 1998;89:415–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu YT, BaTu MK, Song RQ, Liu SF, Xu ZM, BaYin CH. Analysis on genetic diversity of Dermacentor niveus characteristics in three regions of Xinjiang. CJPVM. 2018;40:260–3. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright S. Genetical structure of populations. Nature. 1950;166:247–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meng QL, Qiao J, Sheng JL, Wang JW, Wang WS, Yao N, et al. Survey on tick-borne anaplasmataceae in the south edge of Gurbantunggut Desert. Chin J Vet Sci. 2012;32:1158–63. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renneker S, Abdo J, Salih DE, Karagenç T, Bilgiç H, Torina A, et al. Can Anaplasma ovis in small ruminants be neglected any longer? Transbound Emerg Dis. 2013;60:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chochlakis D, Ioannou I, Tselentis Y, Psaroulaki A. Human anaplasmosis and Anaplasma ovis variant. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1031–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang JF, Li YQ, Liu ZJ, Liu JL, Niu QL, Ren QY, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of Anaplasma spp. in sheep and cattle from Xinjiang, northwest China. Parasit Vectors. 2015;19:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan YQ, Wang KL, Cui YY, Zhou YC, Zhao SS, Zhang YJ, et al. Molecular detection and phylogenetic analyses of Anaplasma spp. in Haemaphysalis longicornis from goats in four provinces of China. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song R, Wang Q, Guo F, Liu X, Song S, Chen C, et al. Detection of Babesia spp., Theileria spp. and Anaplasma ovis in border regions, northwestern China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65:1537–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mediannikov O, Matsumoto K, Samoylenko I, Drancourt M, Roux V, Rydkina E, et al. Rickettsia raoultii sp. nov., a spotted fever group Rickettsia associated with Dermacentor ticks in Europe and Russia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:1635–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parola P, Rovery C, Rolain JM, Brouqui P, Davoust B, Raoult D. Rickettsia slovaca and R. raoultii in tick-borne Rickettsioses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1105–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tian ZC, Liu GY, Shen H, Xie JR, Luo J, Tian MY. First report on the occurrence of Rickettsia slovaca and Rickettsia raoultii in Dermacentor silvarum in China. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu LJ, Chen Q, Yang Y, Wang JC, Cao XM, Zhang S, et al. Investigations on Rickettsia in ticks at the Sino-Russian and Sino-Mongolian borders, China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015;15:785–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y, Wen XX, Xiao PP, Fan XL, Li M, Chahan BY. Molecular identification of Theileria equi, Babesia caballi, and Rickettsia in adult ticks from north of Xinjiang, China. Vet Med Sci. 2021;7:2219–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li YQ, Guan GQ, Ma ML, Liu JL, Ren QY, Luo JX, et al. Theileria ovis discovered in China. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:304–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qi M, Cui YY, Song XM, Zhao AY, Bo J, Zheng ML, et al. Common occurrence of Theileria annulata and the first report of T. ovis in dairy cattle from Southern Xinjiang, China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:1446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiu XF, Lin HL, Luo J, Aizezi MLK, Kang FY, Ni J, et al. Molecular identification of piroplasm in ticks of Xinjiang border areas. Progr Vet Med. 2022;43:31–7. 10.16437/j.cnki.1007-5038.2022.01.010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luo D, Yin XP, Wang AD, Tian YH, Liang Z, Ba T, et al. The first detection of Babesia genotype from tick at Alataw Pass, China–Kazakhstan border. Chin J Endemiol. 2016;35:633–5. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang LJ, Liu D, Ma B, Bu SP, Song RX, Wang YZ. Investigation on piroplasms in on-host ticks in border area of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2023;34:564–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used for tick species identification and screening of tick-borne pathogens. Table S2. Sequencing data obtained in this study. Table S3. Reference sequence information used for phylogenetic tree construction in the study. Table S4. Reference sequence information for haplotype phylogenetic tree construction of Hy. asiaticum. Fig. S1. Phylogenetic analysis of tick species based on 16S rRNA gene sequences.

Data Availability Statement

Data are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.