Abstract

Background

There is a need to expand the current scope of assessment tools usually applied to patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA). This study aimed to assess the psychometric properties (reliability and discriminant validity) of a set of new patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) called PROfuture, after analysing the performance of individual items of the questionnaires.

Results

Patients included in the Spanish SMA Patient-Reported Registry (RegistrAME) were invited to answer 10 questionnaires: Fatigability; Pain; Scoliosis and Contractures (S&C); Feeding (F); Breathing and Voice (B&V); Sleep and Rest (S&R); Vulnerability; Infections and Hospitalisations (I&H); Time spent in care (T); and Mobility and Independence (M&I). The diagnosis date, type of SMA, functional classification, and comorbidities were also collected. A total of 160 patients of the 330 included in RegistrAME participated in the study: mean age (SD) 18 (16.6) years, 27.5% non-sitter, 46.88% sitter, and 25.63% walker, 20.0% type 1 SMA, 51.88% type 2, and 28.12% type 3. The frequency of symptoms varied from 43.5% of patients reporting some degree of Pain to 96.3% reporting some degree of Fatigability. The reliability assessed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was > 0.75 for all the PROs and > 0.9 for S&C, F, B&V, T, and M&I. Regarding content validity, scores were higher (worse health status) in type 1 SMA patients than in types 2 and 3, and were also higher for non-sitter patients than for sitter and walker patients.

Conclusions

The ten questionnaires included in the PROfuture set were developed based on what people living with spinal muscular atrophy and their caregivers consider relevant. This preliminary study provides an initial basis to consider their potential usefulness in assessing aspects that matter to this population. The early findings are promising, however, further extensive psychometric evaluation is needed. PROfuture is a new set of patient-reported outcome measures, specifically designed by and for individuals living with spinal muscular atrophy and their caregivers. Future studies will help strengthen the evidence regarding its reliability and validity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13023-025-03832-y.

Keywords: Spinal muscular atrophy, Patient reported outcomes, Psychometric properties, Quality of life, Treatment outcomes

.

Background

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neuromuscular disease characterized by the degeneration of motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord [1]. The most common cause of SMA is a biallelic mutation in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene [2, 3]. On average, the estimated combined incidence of all types of SMA is 8 per 100,000 live births, with a prevalence of 1–2 per 100,000 persons [4]. Despite SMA being a rare disease, it has been one of the leading monogenic causes of infant mortality [5]. Moreover, a recently published study has shown that, during the pre-treatment era, patients with SMA of all ages and phenotypes had a higher all-cause mortality rate compared with age-matched controls [6]. The impact on those living with SMA and their families goes beyond the progressive mobility impairment and physical deterioration. SMA patients and their families experience a high level of emotional and social burden due to the loss of functional abilities, expectations, premature death, or social discomfort and stigma, among others [7]. Thus, SMA usually has a huge impact on the health-related quality of life of patients and their families [8–10].

Currently, different motor function scales and questionnaires are used to evaluate the functional state of patients with SMA depending on their phenotype and age. Among them, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND) [11], the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE) [12], the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale-Expanded (HFMSE) [13], the Revised Upper Limb Module (RULM) [14], and the Six-minute walk test (6MWT) [15] are the most used scales in Spain.

However, these scales show both floor and ceiling effects, especially in adult patients [16]. Moreover, they focus on motor function, neglecting other areas relevant to patients and that might improve with new treatments. This idea has been underlined in several published studies. One of these [17] highlighted that current scales and questionnaires do not adequately address the full burden of SMA due to the heterogeneity of the disease. The authors stated that it is important to broaden the way these patients are evaluated. Another study [18] provided information about the impact of several symptoms on adult patients with SMA.

Therefore, bearing in mind the need to expand the current scope of assessment tools usually applied to SMA patients, five focus groups with patient experts and caregivers were organised by the Spanish SMA Foundation (FundAME, by its Spanish acronym). The objective of these groups was to obtain information on the impact of the disease on patients’ lives, including physical, psychological, and social aspects, while considering the different phenotypes of the disease. Details on the methodology used and results obtained have been reported elsewhere [19]. As a result, a set of 142 items grouped into 10 domains or questionnaires (PROfuture) were developed. The 10 questionnaires assess different areas: Fatigability, Pain, Scoliosis and Contractures, Feeding, Breathing and Voice, Sleep and Rest, Vulnerability, Infections and Hospitalisations, Time spent in care, and Mobility and Independence. The questionnaire was incorporated as a new module into the FundAME patient registry, RegistrAME, which adheres to a rigorous curation system [20]. All questionnaires were designed with clear and straightforward language to minimise misinterpretation. A pilot phase was conducted to validate the online format and ensure consistency with face-to-face administration [19] (Supplementary material: PROfuture Dataset). To facilitate the patient’s experience and ensure they feel identified with the questions they need to answer, a design based on a computerized assisted administration system was used. This system operates using health data previously entered into the registry and dynamically adapts the questions according to the health data collected, related to variables such as age, motor level, use of a wheelchair, and type of wheelchair (electric, manual, or mixed). The questions are presented specifically and sequentially according to these predefined criteria, ensuring that each participant only sees the relevant questions. This can be seen in the Supplementary Material, where the questions are displayed according to motor level or wheelchair usage.

By doing this, firstly, patients only answer those questionnaires that assess areas of life that they feel impacted and do not receive questions that are out of context and/or emotionally inappropriate, thereby assuring, secondarily, adherence to the response process, in addition to shortening the time that the patient must invest in the task.

In the present study, the performance of individual items and the psychometric properties of the new questionnaires (reliability and discriminant validity) were analysed.

Methods

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted. Patients included in the Spanish SMA Patient-Reported Registry (RegistrAME) [20] were invited to participate; if the patient was under 12 years old, their parents were invited as surrogates. All patients in the RegistrAME have a confirmed diagnosis of autosomal recessive 5q SMA (genetic confirmation of biallelic mutation predictive of loss-of-function of the SMN1 gene) and had signed an informed consent to participate in the registry. For patients between 12 and 17 years of age, the assent of the patients and the informed consent of their parents were obtained. For patients between 2 and 12 years old, the parents signed the informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Hospital Clínico San Carlos” of Madrid (21/561-E).

. Patients or their parents were asked to answer the set of 10 PROfuture questionnaires via the RegistrAME website. Each questionnaire focuses on a specific domain: Fatigability (19 items), Pain (10 items), Scoliosis and Contractures (12 items), Feeding (21 items), Breathing and Voice (8 items), Sleep and Rest (4 items), Vulnerability (9 items), Infections and Hospitalisations (4 items), Time Spent in Care (10 items), and Mobility and Independence (45 items).

Diagnostic date, SMA type, number of SMN2 copies, functional classification, and comorbidities were also collected. The data collection started on May 1, 2020, and finished on April 30, 2021.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the statistical package SAS®.

Item analysis. This analysis first sought to verify that the items grouped in each PROfuture questionnaire assessed the same concept, and then to build the score for each questionnaire after deleting items with bad performance. This analysis included (1) the percentage of missing responses for each item; (2) the distribution of responses for each item; and (3) the estimation of item-total correlation coefficients, to assess their discriminative power (homogeneity index). Items with missing values for more than 20% of patients who were expected to respond (some items are only presented based on a response to a previous item), those with a skewed distribution of responses (ceiling or floor effect greater than 20%), and those that showed an item-total correlation coefficient of less than 0.30 were eliminated from the questionnaire. An exploratory factorial analysis was then carried out with the items belonging to each of the questionnaires to group them into dimensions (a questionnaire may have more than one dimension if so determined in this analysis). Subsequently, the score calculation for each questionnaire was performed as a percentage; thus, a higher score indicates a higher impact of the disease.

Analysis of the domains or questionnaires. For each scale, the following analyses were carried out: (1) reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which should be greater than 0.7; and (2) analysis of the discriminant validity, comparing the scores of the questionnaires among the different groups of patients according to SMA type, age, SMN2 copy number, and current ambulation status.

Results

Of the 330 SMA patients enrolled in RegistrAME, 160 agreed to participate in the present study and completed the PROfuture questionnaires. The number of patients who reported an impact on each area and completed the respective questionnaire were: Fatigability (N = 155), Sleep and Rest (N = 151), Infections and Hospitalisations (N = 132), Vulnerability (N = 130), Mobility and Independence (N = 129), Scoliosis and Contractures (N = 121), Breathing and Voice (N = 117), Feeding (N = 116), Time spent in care (N = 115), and Pain (N = 70). Only 45 patients reported symptoms in all domains and, consequently, answered all the questionnaires.

According to the type of SMA, 32 patients (20.0%) were classified as type 1, 83 (51.88%) as type 2, and 45 (28.12%) as type 3. For this classification, the onset of symptoms and the maximum motor level achieved were considered. The main characteristics of the sample, according to SMA type, are shown in Table 1. According to functional status, 41 patients were classified as “walkers”, 75 as “sitters” and 44 as “non-sitters”. Among the “walkers”, 18 (43.9%) walked independently and never used a wheelchair, 9 (22%) walked at home alone but needed a wheelchair when leaving home, and 14 (34.1%) walked short routes but used a wheelchair for longer stretches. Among the “sitters”, 4 (5.3%) were able to sit and stand up on their own, 11 (14.5%) were able to sit on their own but not stand, and 61 (80.2%) were not able to sit on their own but could remain seated independently.

Table 1.

Main sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample

| SMA 1 (n = 32) | SMA 2 (n = 83) | SMA 3 (n = 45) | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age. Mean (SD). | 4.56 (4.41) | 17.02 (14.07) | 29.09 (18.88) | 17.93 (16.62) |

| Range [min-max] | [1–21] | [2–62] | [3–76] | [1–76] |

| Number of SMN2 copies. N (%) | ||||

| 2 copies | 24 (75.00%) | 8 (9.64%) | 1 (2.20%) | 33 (20.63%) |

| 3 copies | 7 (21.88%) | 65 (78.31%) | 27 (60.00%) | 99 (61.88%) |

| 4 copies | 3 (3.61%) | 16 (35.56%) | 19 (11.88%) | |

| Functional classification. N (%) | ||||

| Non-sitter | 14 (43.75%) | 28 (33.73%) | 2 (4.44%) | 44 (27.50%) |

| Sitter | 15 (46.88%) | 49 (59.04%) | 11 (24.44%) | 75 (46.88%) |

| Walker | 3 (9.38%) | 6 (7.23%) | 32 (71.11%) | 41 (25.63%) |

| Disease-modifying treatment for SMA. N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 32 (100%) | 60 (72.29%) | 33 (73.33%) | 125 (78.13%) |

| No | - | 23 (27.71%) | 12 (26.67%) | 35 (21.87%) |

To account for differences in responses from patients and proxies, we identified who was responding to the questionnaire in the registry. All responses for participants under the age of 15 were completed by parents, while participants aged 21 or older completed the questionnaire independently. For participants aged 16 to 20, responses were mixed between patients and parents. While all responses were analysed collectively in this study due to sample size limitations, future research will separately analyse patient and proxy data to explore potential differences.

Item analysis

Items with bad performance according to pre-specified criteria were eliminated from the questionnaire. The following items were eliminated: Feeding (five items referring to gastric button feeding were removed for scoring purposes due to a low item-total correlation coefficient, although they will be kept in the questionnaire for descriptive purposes for a specific group of the SMA patient population), Breathing and Voice (one item was deleted because a high number of values were missing), Vulnerability (two items were removed because of a high ceiling effect), Infections and Hospitalisations (a score could not be generated for this dimension, although it was considered useful for descriptive purposes), and Mobility and Independence (seven items removed due to a ceiling effect, eight items due to a floor effect, and one additional item due to a low item-total correlation coefficient). No items were removed from Fatigability, Pain, Scoliosis and Contractures, Sleep and Rest, and Time spent in care.

Exploratory factor analysis allowed us to identify different sub-dimensions in most of the questionnaires (Fatigability-2 factors; Pain-5 factors; Scoliosis and Contractures-3 factors; Feeding-2 factors; Breathing and Voice-2 factors; Vulnerability-4 factors; Time spent in care-2 factors; and Mobility and Independence-3 factors), which accounted for more than 80% of the score variance. Despite this, the research team decided to build only one global score for each questionnaire, considering that the first loading factor in each questionnaire accounted for ≥ 50% of the score variance and that item-total correlation was high in all cases. A score was not calculated for Sleep and Rest because it has one factor for every single item of the questionnaire, nor for Infections and Hospitalisations as it was decided to use them only for descriptive purposes (see above).

Analysis of the questionnaires

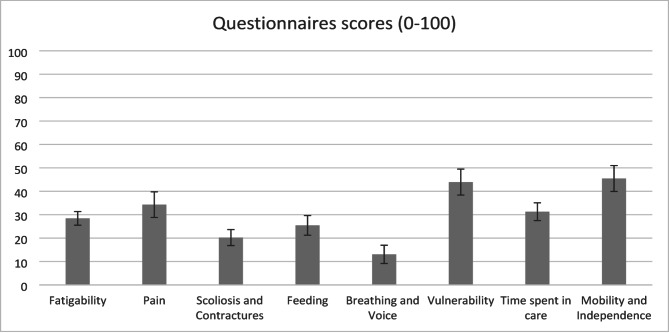

The mean total scores of the questionnaires, after deleting items with bad performance, are presented in Fig. 1. For Sleep and Rest and Hospitalisations, where a total score was not calculated, the answer distribution is presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Mean scores and standard error of the PROfuture questionnaires

Table 2.

Distribution of items of sleep and rest and hospitalisations

| Sleep and Rest items | Total | Hospitalisations items | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Have you woken up during the night to ask for help and to be helped to move in bed? | Valid N | 151 | 1. Number of respiratory infections during the last month | Valid N | 132 |

| Never | 47 (31.13%) | 0 | 119 (90.15%) | ||

| Rarely | 17 (11.26%) | 1 | 6 (4.55%) | ||

| Sometimes | 20 (13.25%) | Missing | 7 (5.30%) | ||

| Very often | 16 (10.60%) | 2. Number of visits to the emergency room in the last 3 months | Valid N | 132 | |

| Always | 48 (31.79%) | 0 | 110 (83.33%) | ||

| Missing | 3 (1.99%%) | 1 | 14 (10.61%) | ||

| 1a. The nights that you have woken up, how many times is usual? | Valid N | 95 | 2 | 1 (0.76%) | |

| 1 time | 26 (27.37%) | Missing | 7 (5.30%) | ||

| 2–3 times | 49 (51.58%) | 3. Number of days admitted to the hospital or at home during the last 3 months | Valid N | 132 | |

| 4 + times | 20 (21.05%) | 0 | 115 (87.12%) | ||

| 2. If you use a ventilation device, did you wake up during the night because it bothered you? | Valid N | 151 | 1 | 4 (3.03%) | |

| Never | 59 (39.07%) | 2 | 3 (2.27%) | ||

| Rarely | 16 (10.60%) | 7+ | 1 (0.76%) | ||

| Sometimes | 20 (13.25%) | Missing | 9 (6.82%) | ||

| Very often | 2 (1.32%) | 3a. Of the days in the hospital, how many were in the intensive care unit during the last 3 months? | Valid N | 8 | |

| Always | 6 (3.97%) | 0 | 8 (100%) | ||

| Missing | 48 (31.79%) | ||||

| 3. Have you woke up tired after sleeping at night? | Valid N | 151 | |||

| Never | 45 (29.80%) | ||||

| Rarely | 53 (35.10%) | ||||

| Sometimes | 35 (23.18%) | ||||

| Very often | 7 (4.64%) | ||||

| Always | 1 (0.66%) | ||||

| Missing | 56 (37.09%) |

To assess the internal consistency of each domain, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for the total scores of all ten PROfuture questionnaires. As shown in Table 3, all scales demonstrated good to excellent internal reliability, with alpha values ranging from 0.78 to 0.97.

Table 3.

Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of profuture questionnaires

| Questionnaire | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|

| Fatigability | 0.83 |

| Pain | 0.78 |

| Scoliosis and Contractures | 0.91 |

| Feeding | 0.97 |

| Breathing and Voice | 0.95 |

| Vulnerability | 0.78 |

| Time Spent in Care | 0.94 |

| Mobility and Independence | 0.97 |

Differences in questionnaire scores between different groups of patients based on the type of SMA and current ambulation status are presented in Tables 4 and 5 respectively; and those according to age and the number of SMN2 copies are presented in Tables 6 and 7. Overall, the questionnaires discriminated well between the different subgroups of patients.

Table 4.

Scores of the profuture questionnaires according to SMA type classification

| Variable | SMA 1 | SMA 2 | SMA 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores (0–100) for Fatigability | Valid N | 31 | 81 | 42 | 155 |

| Mean (SD) | 30.38 (24.71) | 28.97 (16.78) | 26.25 (15.18) | 28.43 (18.16) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Pain | Valid N | 10 | 36 | 19 | 65 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.01 (19.39) | 37.46 (21.91) | 35.83 (21.80) | 34.30 (22.07) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Scoliosis and Contractures | Valid N | 26 | 63 | 25 | 115 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.56 (15.87) | 23.55 (20.71) | 13.38 (11.39) | 20.23 (18.33) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Feeding | Valid N | 23 | 63 | 23 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 40.51 (26.28) | 24.69 (19.93) | 13.29 (13.62) | 25.44 (22.04) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Breathing and Voice | Valid N | 25 | 63 | 23 | 112 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.36 (24.34) | 11.48 (13.25) | 3.48 (6.30) | 13.06 (17.20) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Vulnerability | Valid N | 25 | 72 | 28 | 126 |

| Mean (SD) | 47.68 (27.79) | 44.36 (25.96) | 40.26 (28.91) | 43.92 (26.87) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Time spent in care | Valid N | 16 | 63 | 29 | 109 |

| Mean (SD) | 41.03 (16.95) | 30.99 (16.37) | 27.33 (16.19) | 31.28 (16.89) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Mobility and Independence | Valid N | 19 | 65 | 29 | 114 |

| Mean (SD) | 63.41 (27.02) | 50.62 (20.68) | 23.69 (20.04) | 45.47 (25.81) |

Table 5.

Scores of the profuture questionnaires according to current ambulation status

| Variable | Non-sitter | Sitter | Walker | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores (0–100) for Fatigability | Valid N | 42 | 72 | 41 | 155 |

| Mean (SD) | 41.81 (21.35) | 21.59 (12.73) | 26.74 (15.46) | 28.43 (18.16) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Pain | Valid N | 19 | 29 | 17 | 65 |

| Mean (SD) | 41.24 (22.82) | 31.05 (20.21) | 32.08 (23.81) | 34.30 (22.07) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Scoliosis and Contractures | Valid N | 33 | 58 | 24 | 115 |

| Mean (SD) | 30.65 (21.94) | 18.81 (15.39) | 9.34 (11.10) | 20.23 (18.33) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Feeding | Valid N | 31 | 56 | 23 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 36.32 (28.08) | 24.05 (18.06) | 14.19 (14.54) | 25.44 (22.04) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Breathing and Voice | Valid N | 33 | 56 | 23 | 112 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.58 (16.68) | 10.87 (13.99) | 9.02 (22.49) | 13.06 (17.20) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Vulnerability | Valid N | 35 | 65 | 26 | 126 |

| Mean (SD) | 56.82 (23.89) | 39.56 (26.40) | 37.44 (26.91) | 43.92 (26.87) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Time spent in care | Valid N | 29 | 56 | 24 | 109 |

| Mean (SD) | 32.21 (18.24) | 33.14 (16.53) | 25.81 (15.52) | 31.28 (16.89) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Mobility and Independence | Valid N | 33 | 57 | 24 | 114 |

| Mean (SD) | 69.72 (16.71) | 44.03 (18.83) | 15.56 (15.46) | 45.47 (25.81) |

Table 6.

Scores of the profuture questionnaires according to age

| Variable | < 2 years | 2–6 years | 7–10 years | 11–15 years | > 15 years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores (0–100) for Fatigability | Valid N | 2 | 46 | 22 | 18 | 67 | 155 |

| Mean (SD) | 31.25 (8.84) | 25.73 (18.36) | 27.46 (19.36) | 21.82 (9.87) | 32.30 (19.01) | 28.43 (18.16) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Pain | Valid N | 0 | 13 | 6 | 10 | 36 | 65 |

| Mean (SD) | . (.) | 17.92 (16.12) | 30.85 (13.12) | 34.72 (18.35) | 40.67 (23.39) | 34.30 (22.07) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Scoliosis and Contractures | Valid N | 2 | 36 | 14 | 10 | 53 | 115 |

| Mean (SD) | 30.80 (0.00) | 12.59 (13.16) | 16.88 (14.34) | 26.69 (18.53) | 24.69 (20.80) | 20.23 (18.33) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Feeding | Valid N | 1 | 35 | 12 | 10 | 52 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 50.80 (.) | 26.39 (18.41) | 26.13 (24.08) | 16.09 (5.13) | 25.96 (25.52) | 25.44 (22.04) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Breathing and Voice | Valid N | 2 | 36 | 13 | 10 | 51 | 112 |

| Mean (SD) | 37.50 (53.03) | 16.44 (20.68) | 4.00 (4.90) | 7.20 (9.00) | 13.16 (14.84) | 13.06 (17.20) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Vulnerability | Valid N | 2 | 36 | 18 | 14 | 56 | 126 |

| Mean (SD) | 42.00 (59.40) | 39.01 (24.17) | 29.19 (24.82) | 43.06 (20.30) | 52.09 (27.61) | 43.92 (26.87) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Time spent in care | Valid N | 1 | 24 | 17 | 13 | 54 | 109 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.30 (.) | 35.00 (18.62) | 31.47 (15.78) | 42.82 (17.80) | 26.88 (14.99) | 31.28 (16.89) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Mobility and Independence | Valid N | 1 | 27 | 17 | 13 | 56 | 114 |

| Mean (SD) | 25.70 (.) | 51.56 (28.72) | 37.65 (24.75) | 45.75 (16.26) | 45.20 (26.43) | 45.47 (25.81) |

Table 7.

Scores of the profuture questionnaires according to SMN2 copy number

| Variable | 2 copies | 3 copies | 4 copies | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores (0–100) for Fatigability | Valid N | 31 | 95 | 20 | 148 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.55 (21.93) | 30.31 (16.97) | 23.76 (19.23) | 28.61 (18.35) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Pain | Valid N | 10 | 36 | 19 | 65 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.01 (19.39) | 37.46 (21.91) | 35.83 (21.80) | 34.30 (22.07) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Scoliosis and Contractures | Valid N | 26 | 71 | 14 | 112 |

| Mean (SD) | 16.77 (12.46) | 22.51 (19.89) | 15.00 (19.30) | 20.09 (18.42) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Feeding | Valid N | 24 | 68 | 14 | 107 |

| Mean (SD) | 33.01 (22.13) | 26.10 (22.43) | 12.24 (16.37) | 25.65 (22.29) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Breathing and Voice | Valid N | 25 | 69 | 14 | 109 |

| Mean (SD) | 24.25 (24.49) | 10.89 (13.47) | 2.86 (6.55) | 12.86 (17.29) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Vulnerability | Valid N | 26 | 79 | 16 | 122 |

| Mean (SD) | 44.98 (29.77) | 41.54 (24.81) | 45.09 (30.34) | 43.05 (26.61) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Time spent in care | Valid N | 18 | 70 | 16 | 105 |

| Mean (SD) | 40.25 (13.74) | 30.45 (17.26) | 25.51 (17.32) | 31.27 (17.11) | |

| Scores (0–100) for Mobility and Independence | Valid N | 22 | 71 | 16 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 52.59 (29.67) | 46.39 (23.27) | 27.02 (26.91) | 44.92 (26.06) |

Discussion

The motor scales and questionnaires currently used in patients with SMA do not usually assess the full burden of this disease [17, 18]. Therefore, there is a need for new measures incorporating other important areas of patients’ lives that are not covered by the pre-existing tools [21, 22]. Thus, to expand the scope of the assessment tools currently applied to SMA patients, ten new questionnaires (PROfuture) were developed by a multidisciplinary team of SMA patients and experts. A previous multicentre study assessed four of these questionnaires (Fatigability, Breathing and Voice, Sleep and Rest, and Vulnerability) along with other outcome measurements (SMA Tool) in a multicentre clinical-based setting [23]. In contrast, in the present study, all ten questionnaires were assessed online in a home-based setting. After analysing individual item functioning and deleting some items with bad performance according to prefixed criteria, total scores were built for each questionnaire, except for Sleep and Rest and Infections and Hospitalisations. The questionnaires showed good reliability and discriminant validity.

The exploratory factor analysis showed multidimensionality in all questionnaires analysed, nevertheless, the research group decided to build only one total score for each questionnaire in order to facilitate the interpretability of the scores when using the questionnaires in routine clinical practice. Total scores were not created for Sleep and Rest and Infections and Hospitalisations, however, the small number of items in these questionnaires makes them useful to assess their respective areas, without the need for a total score.

All questionnaires but one (Pain) were answered by more than 70% of patients. Fatigability was the most frequently reported area of impairment (97% of patients). This was followed by Vulnerability, Scoliosis and Contractures, and Mobility and Independence, regardless of the SMA type or functional subgroup This discrepancy in participation suggests a potential influence of the program’s design. Originally, the program was conceived for use on laptops or tablets and was not fully adapted for mobile devices. This lack of adaptation could have restricted the visibility of certain areas on mobile devices, thereby potentially affecting participants’ engagement in those areas.

The highest scores were observed in Vulnerability, Mobility and Independence, Pain, and Time spent in care, indicating that some areas that were not so frequently reported may also have a significant impact on patients’ lives. Some areas, like Mobility and Independence and Pain, are assessed in other questionnaires, such as the SMAIS [24], the EK2 scale [25], and SMA-HI [26]; however, it is remarkable that other areas, like Vulnerability and Time spent, in care are not explored by other tools. This is even more important in the case of Vulnerability, which was answered by 81% of participants and showed the highest impact of all questionnaires. It is worth noting that the Pain questionnaire was answered by less than half of the patients, yet its total score was the third highest of the ten questionnaires. This suggests that, although pain is less frequent than other symptoms, it may have a significant impact on some SMA patients. The mean scores (standard deviation) for Fatigability, Breathing and Voice, and Vulnerability obtained by the patients in the previous study using these questionnaires [23] were 21.86 (19.66), 8.88 (15.18,) and 13.41 (18.36), respectively. These scores were slightly lower than those of the present study for Fatigability and Breathing and Voice, and considerably lower in the case of Vulnerability. However, the sample included herein incorporated more patients under eight years of age than the previous study (31.25% vs. 24.77%) and more patients with more severe forms of the disease (SMA 1 patients: 20% vs. 7.96%).

The Fatigability questionnaire confirmed previous results [23] of good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha close to 0.8, and good discriminant validity, showing higher scores in patients with younger onset (type 1) and worse function (non-sitter). A greater impact of fatigability on non-sitter patients had been previously suggested in a preliminary study, using the same questionnaire, but focusing on adolescent and adult patients [27].

The Pain questionnaire showed good reliability, like Fatigability. The discriminant validity was also good for ambulation status (it was higher in non-sitters than in sitters vs. walkers), but not for SMA type: Pain scores were higher in patients with SMA types 2 and 3, compared with type 1. Moreover, there was a consistent increase in Pain scores with age (Table 6), suggesting that pain is less frequent and severe in children under 11 years old.

Scoliosis and Contractures showed very good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha > 0.9. Concerning discriminant validity, scores of non-sitter patients were higher than those of sitter and walker patients, and scores of type 2 patients showed the highest impact of this area on this group of patients compared with type 1 and type 3 patients. Again, this suggests an increasing impact of scoliosis and contractures with age in non-sitter patients. Consistently, there is an increase in scores with age (Table 6), particularly between 11 and 15 years old, reflecting the natural history of the disease [28].

The Feeding questionnaire demonstrated very good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97) and good discriminant validity, presenting higher scores in patients with more severe disease.

Cronbach’s alpha of the Breathing and Voice questionnaire was 0.95, showing very good reliability. Discriminant validity was also good since patients with more severe disease had higher scores, as found in the previous study [23].

The Vulnerability questionnaire showed good reliability and discriminant validity, as in the previous study [23].

The Time spent in care questionnaire showed very good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94). The discriminant validity was good for SMA type and severity but, interestingly, scores were similar for non-sitter and sitter patients, suggesting that ambulation is key for determining the time spent in care.

Mobility and Independence showed a very high Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, indicating very good reliability. Discriminant validity was also good as patients with more severe disease had higher scores.

PROFuture PROM comprises a set of 10 different questionnaires that specifically assess the areas of life that are more relevant to a specific patient in order to detect small changes that could be meaningful for that subject. The research team considered this mode of assessing patients’ symptoms more useful (instead of developing a unique score by adding the scores from all dimensions), and probably more sensitive to changes, for the evaluation of future treatments.

Limitations of the study

One limitation of the present study is that data was collected through the website of the Fundame registry, which may skew the profile of patients evaluated towards those more engaged. A second limitation is that the sample includes very heterogeneous patients regarding demographic and disease-related characteristics, combining both patients’ and parents’ responses, which might make the interpretation of the results difficult. However, the objective of the study was precisely to provide an overview of disease burden over the whole disease spectrum and, in children under 12 years old, parents are the most reliable informants. Moreover, despite this limitation, we were able to demonstrate the good or very good reliability and validity of most questionnaires.

While all responses were analysed collectively in this study due to sample size limitations, identifying patient and proxy responses allowed us to ensure clarity in the data. Future research will build on this foundation by separately analysing these groups to further refine the tool and enhance its applicability across diverse respondent types.

The data were collected from a self-reported patient registry, which inherently relies on the proactivity and willingness of patients to participate. This may influence the profile of the evaluated patients, as those who are more engaged or proactive could be overrepresented, potentially leading to a less diverse sample. The criterion validity could not be assessed as no other questionnaire (RULM, HFMSE…) was collected from participants in this study. Additionally, convergent and criterion validity will be established to further validate PROfuture. Plans are already in place to evaluate its correlations with established clinical tools (e.g., RULM, HFMSE) and to explore its relationship with broader clinical endpoints.

Conclusions

The PROfuture questionnaires, developed by patients for patients in the current era of new treatments for SMA, can help to better characterize the impact of SMA on different areas of patients’ lives that are currently unexplored by other tools. These questionnaires can be implemented both in home- and clinical-based settings. Moreover, they can be used together (as a comprehensive tool) or separately, depending on the objectives of the study, making them ideal for their use in research settings. Future longitudinal studies should assess the sensitivity to change of the PROfuture questionnaires in a home-based setting so that they can be incorporated into clinical trials and practice.

Additionally, convergent and criterion validity will be established to further validate PROfuture. Plans are already in place to evaluate its correlations with established clinical tools (e.g., RULM, HFMSE) and to explore its relationship with broader clinical endpoints. This step will be essential to position PROfuture as a reliable and robust outcome measure for both clinical and research applications.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are immensely grateful to all the patients and their families for their collaboration in this project.

Abbreviations

- SMA

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

- PROMs

Patient-reported outcome measures

- S&C

Scoliosis and Contractures

- F

Feeding

- B&V

Breathing and Voice

- S&R

Sleep and Rest

- I&H

Infections and Hospitalisations

- T

Time spent in care

- M&I

Mobility and Independence

- SMN1

Survival motor neuron 1 gene

- CHOP INTEND

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders

- HINE

Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination

- HFMSE

Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale-Expanded

- RULM

Revised Upper Limb Module

- 6MWT

Six-minute walk test

Author contributions

SIPP, ML JM, MD and JFVC have contributed to the conception, design, and interpretation of data and substantially revised it. MGC has contributed to the conception, design, acquisition, curation, and interpretation of data and substantially revised it. PR has contributed to the conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafted the work.

Funding

This project has been funded by FundAME with partial financial support provided by Roche, Novartis, and Biogen.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are not publicly available. This is to protect the study participants’ privacy. Data could be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Hospital Clínico San Carlos” of Madrid (21/561-E). All participants provided their informed consent to participate in the registry.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MGC has received support from Roche for attendance at scientific congresses. SIPP has received honoraria for conferences, consultancies, and participation in clinical trials with Biogen, Roche and Novartis outside the submitted work. ML has offered advisory support to Roche in the development of risdiplam. JM has received honoraria for conferences, consultancies, and participation in clinical trials with Biogen, PTC, Roche, and Avexis outside the submitted work. MD has no conflict of interest to declare. PR was an employee of IQVIA who received an honorarium from Fundame in connection with the development of this manuscript. JFVC is funded by grants of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (JR19/00030, PI Vázquez) and received personal fees from Biogen and Roche outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Markowitz JA, Singh P, Darras BT. Spinal muscular atrophy: a clinical and research update. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrar MA, Kiernan MC. The Genetics of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Progress and Challenges. Neurotherapeutics: The Journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2015;12(2):290–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kolb SJ, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin. 2015;33(4):831–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhaart IEC, Robertson A, Wilson IJ, Aartsma-Rus A, Cameron S, Jones CC, et al. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q-linked spinal muscular atrophy - a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugarman EA, Nagan N, Zhu H, Akmaev VR, Zhou Z, Rohlfs EM, et al. Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of > 72,400 specimens. Eur J Hum Genetics: EJHG. 2012;20(1):27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viscidi E, Juneja M, Wang J, Wang N, Li L, Farwell W, et al. Comparative All-Cause mortality among a large population of patients with spinal muscular atrophy versus matched controls. Neurol Therapy. 2022;11(1):449–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian Y, McGraw S, Henne J, Jarecki J, Hobby K, Yeh WS. Understanding the experiences and needs of individuals with spinal muscular atrophy and their parents: a qualitative study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landfeldt E, Edström J, Sejersen T, Tulinius M, Lochmüller H, Kirschner J. Quality of life of patients with spinal muscular atrophy: A systematic review. Eur J Pediatr Neurology: EJPN: Official J Eur Pediatr Neurol Soc. 2019;23(3):347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belter L, Cruz R, Jarecki J. Quality of life data for individuals affected by spinal muscular atrophy: a baseline dataset from the cure SMA community update survey. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peña-Longobardo LM, Aranda-Reneo I, Oliva-Moreno J, Litzkendorf S, Durand-Zaleski I, Tizzano E et al. The economic impact and Health-Related quality of life of spinal muscular atrophy. An analysis across Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Glanzman AM, Mazzone E, Main M, Pelliccioni M, Wood J, Swoboda KJ, et al. The children’s hospital of Philadelphia infant test of neuromuscular disorders (CHOP INTEND): test development and reliability. Neuromuscul Disorders: NMD. 2010;20(3):155–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haataja L, Mercuri E, Regev R, Cowan F, Rutherford M, Dubowitz V, et al. Optimality score for the neurologic examination of the infant at 12 and 18 months of age. J Pediatr. 1999;135(2 Pt 1):153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Hagen JM, Glanzman AM, McDermott MP, Ryan PA, Flickinger J, Quigley J, et al. An expanded version of the Hammersmith functional motor scale for SMA II and III patients. Neuromuscul Disorders: NMD. 2007;17(9–10):693–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzone ES, Mayhew A, Montes J, Ramsey D, Fanelli L, Young SD, et al. Revised upper limb module for spinal muscular atrophy: development of a new module. Muscle Nerve. 2017;55(6):869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montes J, McDermott MP, Martens WB, Dunaway S, Glanzman AM, Riley S, et al. Six-Minute walk test demonstrates motor fatigue in spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2010;74(10):833–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vázquez-Costa JF, Povedano M, Nascimiento-Osorio AE, Moreno Escribano A, Kapetanovic Garcia S, Dominguez R, et al. Validation of motor and functional scales for the evaluation of adult patients with 5q spinal muscular atrophy. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(12):3666–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGraw S, Qian Y, Henne J, Jarecki J, Hobby K, Yeh WS. A qualitative study of perceptions of meaningful change in spinal muscular atrophy. BMC Neurol. 2017;17(1):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mongiovi P, Dilek N, Garland C, Hunter M, Kissel JT, Luebbe E, et al. Patient reported impact of symptoms in spinal muscular atrophy (PRISM-SMA). Neurology. 2018;91(13):e1206–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Lemus M, Cattinari MG, Pascual SI, Medina J, García M, Magallón A et al. Identification of the most relevant aspects of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) with impact on the quality of life of SMA patients and their caregivers: the profuture project, a qualitative study. J Patient-Rep Outcomes. 24 de julio de 2024;8:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cattinari MG, de Lemus M, Tizzano E. RegistrAME: the Spanish self-reported patient registry of spinal muscular atrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024;19(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercuri E, Messina S, Montes J, Muntoni F, Sansone VA. Patient and parent oriented tools to assess health-related quality of life, activity of daily living and caregiver burden in SMA. Rome, 13 July 2019. Neuromuscul Disorders: NMD. 2020;30(5):431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gusset N, Stalens C, Stumpe E, Klouvi L, Mejat A, Ouillade MC, et al. Understanding European patient expectations towards current therapeutic development in spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disorders: NMD. 2021;31(5):419–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vázquez-Costa JF, Branas-Pampillón M, Medina-Cantillo J, Povedano M, Pitarch-Castellano I, López-Lobato M et al. Validation of a set of instruments to assess Patient- and Caregiver-Oriented measurements in spinal muscular atrophy: results of the SMA-TOOL study. Neurol Therapy. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Trundell D, Skalicky A, Staunton H, Hareendran A, Le Scouiller S, Barrett L, et al. Development of the SMA independence scale-upper limb module (SMAIS-ULM): A novel scale for individuals with type 2 and non-ambulant type 3 SMA. J Neurol Sci. 2022;432:120059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steffensen B, Hyde S, Lyager S, Mattsson E. Validity of the EK scale: a functional assessment of non-ambulatory individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy or spinal muscular atrophy. Physiotherapy Res International: J Researchers Clin Phys Therapy. 2001;6(3):119–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zizzi CE, Luebbe E, Mongiovi P, Hunter M, Dilek N, Garland C, et al. The spinal muscular atrophy health index: A novel outcome for measuring how a patient feels and functions. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):837–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domine MC, Cattinari MG, De Lemus M, Castellano IP, Ñungo Garzón NC, Sevilla-Matecón T et al. Physical fatigue and perceived fatigability in adolescents and adults with spinal muscular atrophy: a pilot study. Neurol Perspect. 2022.

- 28.Wijngaarde CA, Brink RC, de Kort FAS, Stam M, Otto LAM, Asselman FL, et al. Natural course of scoliosis and lifetime risk of scoliosis surgery in spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2019;93(2):e149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are not publicly available. This is to protect the study participants’ privacy. Data could be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.