Abstract

Background

The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is rising. However, its pathogenesis has not been fully understood, and the current therapeutic regimens are still limited. The aim of this study was to investigate the causal effect of plasma proteins on RA using Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Methods

We performed MR analysis with 4907 plasma protein genetic associations used for exposure and RA genome-wide association data used as outcomes. The method was dominated by Inverse Variance Weighting, in addition to MR-Egger and Weighted Median. Meanwhile, further external validation and reverse MR analysis were conducted to systematically assess the causal relationship between plasma proteins and RA.

Result

Preliminary MR analysis identified two proteins (SPAG11B and DEFB135) associated with RA, and elevated plasma levels of both proteins would reduce the risk of RA (for SPAG11B, OR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.40–0.61, p = 1.19 × 10− 10; for DEFB135, OR = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.15–0.52, p = 4.51 × 10− 5, using the IVW method). In the external validation phase, the results were reproducible for SPAG11B, but not for DEFB135. Reverse MR analysis pointed out that RA exhibited reverse causality for plasma levels of SPAG11B (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.89–0.98, p = 0.004), but not for DEFB135 (p = 0.93).

Conclusion

The results of MR analysis in this study supported that SPAG11B as a novel biomarker for RA was worthy of further investigation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41927-025-00521-y.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Plasma protein, SPAG11B, DEFB135, Mendelian randomization

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that can cause joint inflammation and structural damage such as joint swelling, deformity, and muscle atrophy, resulting in functional impairment [1, 2]. However, the exact pathogenesis of RA is not yet fully understood and there is a lack of targeted therapeutic options, so the prevalence and incidence of RA are increasing year by year [3, 4]. Exploring the etiology and potential therapeutic targets of RA is of great significance for developing therapeutic strategies to slow down its progression.

Plasma proteins are major regulators mediating numerous signaling pathways and biological processes and are considered biomarkers or therapeutic targets for disease [5]. Recently, proteomics-based studies have shown new promise in predicting disease events and potential therapeutic targets [6–9]. Unfortunately, few studies have been conducted to study RA-related plasma proteins based on large-scale population protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) [10, 11].

Genetic variants are randomly classified at the time of conception, and the Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis is to minimize the effect of confounders by using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) for exposure [12–14]. This solves the problem that traditional experimental methods are unable to efficiently account for the causality between exposure factors and outcome variables due to the presence of confounders [12, 13, 14]. MR can correlate plasma protein information obtained through high-throughput sequencing with genome-wide outcomes related to disease phenotypes [12, 15]. Thus, the utilization of human blood proteomics data in MR studies will contribute to a deeper understanding of plasma proteins causally associated with RA, thereby identifying proteins associated with RA causality, improving our understanding of the genetic architecture of RA, and providing new evidence for the identification of drug targets.

Methods

Study design and data sources

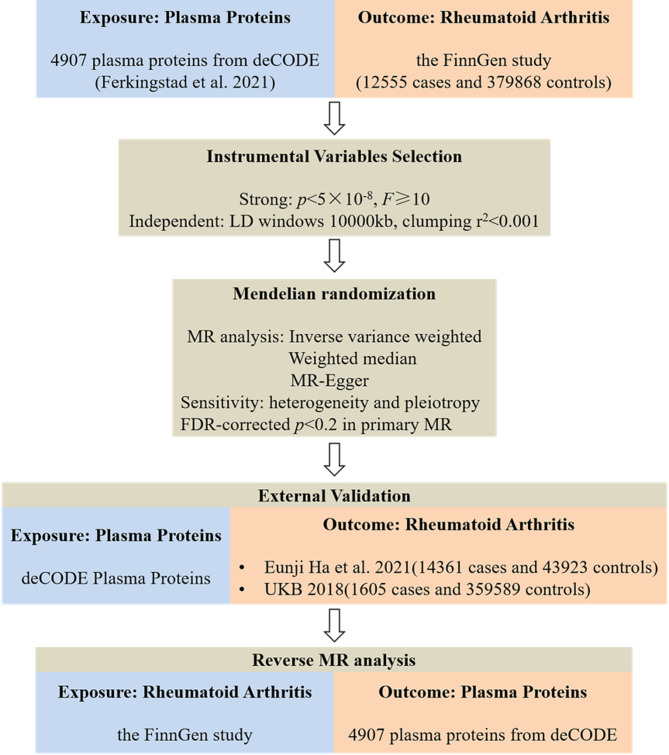

The analysis flowchart of this study was shown in Fig. 1. Plasma proteomics data were obtained from the deCODE database (https://www.decode.com/summarydata/), and RA data were collected from FinnGen (https://r9.risteys.finngen.fi/), Integrative Epidemiology Unit OpenGWAS (IEU, https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) and UK biobank (UKB, https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk) databases.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of MR analysis revealing causality from plasma proteins on RA. MR, Mendelian Randomization; FDR, false discovery rate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Genetic instruments selection

In this study, pQTL data from Ferkingstad et al. were used as exposure [16]. This dataset was based on 35,559 Icelanders who were tested for 4907 plasma proteins using the SomaScan version 4 assay (SomaLogic) and found 18,084 correlations between sequence variations and plasma protein levels [16]. Detailed information on genotyping, interpolation, and quality control can be found in the original paper [16]. For genetic IVs, we selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with genome-wide significance (p < 5 × 10− 8). To minimize the associated horizontal pleiotropy, we needed to eliminate the effect of linkage disequilibrium (LD, LD windows 10000 kb, clumping r2 < 0.001). To quantify the potential of pQTL to predict RA, F-statistics was used as an assessment tool, and IVs with F-statistics ≥ 10 were considered to have sufficient predictive power to be included in the next analysis.

Data sources for RA

In the preliminary MR analysis phase, data for the RA cohort were obtained from the FinnGen database (M13_RHEUMA), which was harvested from 392,423 participants (12555 cases and 379868 controls) and analyzed for 16,380,169 SNPs. The externally validated RA data were obtained from the IEU (ebi-a-GCST90013534) and UKB (ukb-d-M13_RHEUMA) databases. Among them, the IEU cohort included 14,361 cases and 43,923 controls, while UKB brought 1605 cases and 359,589 controls into the cohort.

MR analysis

All MR analysis in this study were performed using the TwoSampleMR package in R (https://github.com/MRCIEU/TwoSampleMR). Analysis methods included Inverse Variance Weighting (IVW), MR-Egger, and Weighted Median, with IVW selected as the primary method to determine the causal effect of plasma proteins on RA. IVW method assesses the causal relationship between exposure and outcome through a linear regression model, which can effectively utilize all available SNPs and thereby enhance statistical power. It has the advantages of high computational efficiency and strong statistical power, especially when the sample size is large [17]. In addition, the Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to perform multiple test correction for all p-values, and multiple comparisons were corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR). When the threshold was set to 0.05, no proteins significantly associated with RA were found. Therefore, the threshold was adjusted to 0.2 [18, 19]. In sensitivity analysis, we used a marker of heterogeneity for the IVW method (Cochran Q-derived p < 0.05) to assess potential heterogeneity among IVs. The intercept obtained in MR-Egger regression is an indicator of directional pleiotropy (p < 0.05 is considered to be present for directed pleiotropy) [12]. Therefore, MR-Egger regression was used to ensure the validity of MR analysis results. Leave-one-out analysis was used to evaluate whether a single SNP would drive or bias MR results.

Reverse MR analysis

Based on the same criteria for MR analysis as described above, we performed a reverse mendelian randomization analysis using the FinnGen RA cohort data as the exposure and deCODE plasma proteins identified as being associated with RA in the preliminary MR analysis as an outcome to explore potential reverse causality. The analysis was carried out by IVW (primary method), MR-Egger and Weighted Median.

Results

Causal effects of plasma proteins on RA

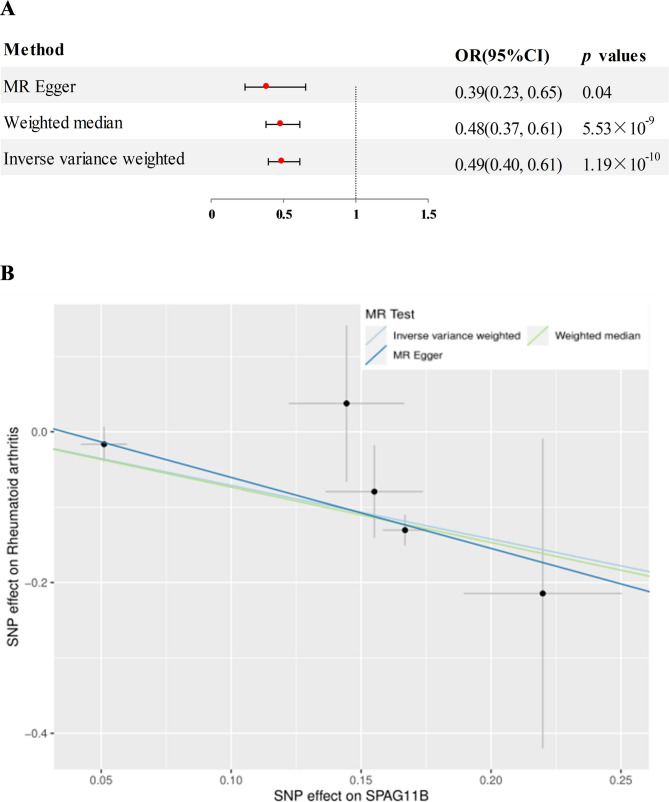

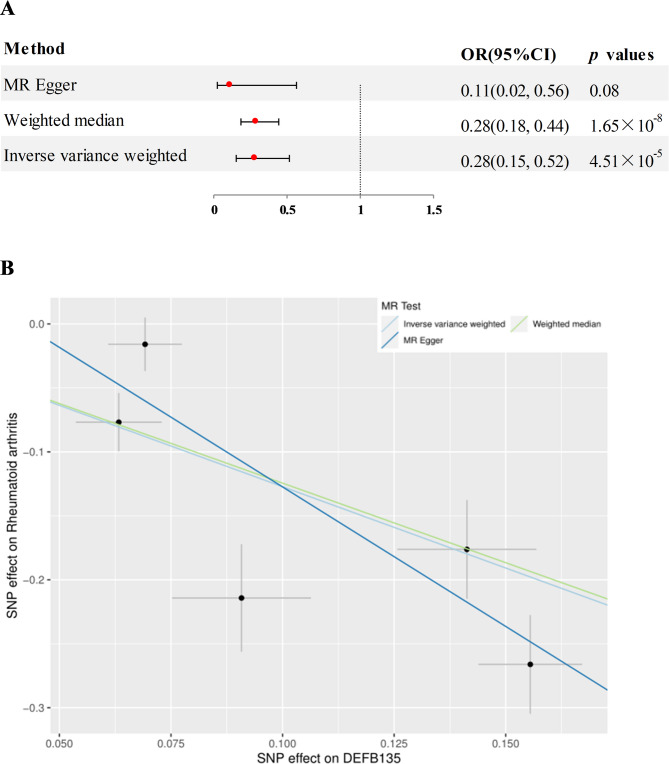

Preliminary MR analysis assessed 4907 plasma proteins for potential association with RA. After adjusting for FDR, two proteins significantly associated with RA were identified (Fig. 2), namely human sperm associated antigen 11 B (SPAG11B) and defensin beta 135 (DEFB135). In detail, elevated plasma levels of SPAG11B (OR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.40–0.61, p = 1.19 × 10− 10, using the IVW method) and DEFB135 (OR = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.15–0.52, p = 4.51 × 10− 5, using the IVW method ) attenuated the risk of RA. The results of SPAG11B were replicated in MR-Egger and Weighted Median analysis methods (Fig. 3A and B, genetic IVs shown in Figure S1a). The results of DEFB135 in Weighted Median were consistent with those of IVW, but p > 0.05 in MR-Egger analysis (Fig. 4A and B, genetic IVs shown in Figure S1b). Analysis combined with intercept and p-value in MR-Egger regression analysis showed that any potential pleiotropy of a single SNP was balanced, which meant that the probability of MR results being biased was relatively low (for SPAG11B, intercept = 0.033, p = 0.40; for DEFB135, intercept = 0.091, p = 0.32). Furthermore, no heterogeneity was observed for SPAG11B (p = 0.52). Although the Cochran’s Q Test for DEFB135 showed the presence of heterogeneity (p = 3.81 × 10− 4) that may be caused by different analytical platforms, experiments and populations, this did not affect the reliability of IVW results, which were acceptable [20].

Fig. 2.

Volcano plot of MR analysis for 4907 plasma proteins on RA risk

Fig. 3.

A MR analysis estimated the causal effect of SPAG11B on RA. B Scatterplot derived from MR on the potential of SPAG11B to predict RA

Fig. 4.

A MR analysis estimated the causal effect of DEFB135 on RA. B Scatterplot derived from MR on the potential of DEFB135 to predict RA

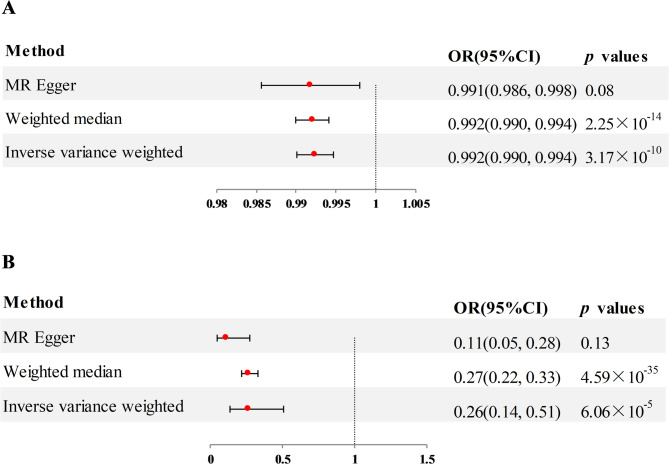

External validation

In the external validation phase, we selected two additional RA datasets and used the same analysis strategy to re-examine the two plasma proteins identified in the preliminary MR analysis as being associated with RA. Of these, the findings for SPAG11B in IEU (OR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.14–0.51, p = 6.06 × 10− 5, using the IVW method) and UKB (OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.990–0.994, p = 3.17 × 10− 10, using the IVW method) were consistent with those of the preliminary MR analysis, with higher plasma level associated with a lower risk of RA (Fig. 5A and B). No bias was seen in the multiplicity test for SPAG11B in both IEU and UKB (Pleiotropy and heterogeneity analysis shown in supplementary Table 1a and b). However, the external validation results of DEFB135 showed no significant correlation with the occurrence of RA (for IEU, p = 0.10; for UKB, p = 0.06; detailed results shown in supplementary Table 2), which was inconsistent with the preliminary MR results.

Fig. 5.

A MR analysis estimated the association of SPAG11B with RA from IEU. B MR analysis estimated the association of SPAG11B with RA from UKB

Reverse MR analysis

To examine whether there is a reverse causality between RA and candidate proteins, we next performed reverse MR analysis of the two plasma proteins identified in the preliminary analysis. The MR results of IVW showed that the occurrence of RA caused a reduction in plasma levels of SPAG11B (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.89–0.98, p = 0.004, Figure S2a and b). For DEFB135, the reverse MR results showed that there was no reverse causal effect of RA on DEFB135, meaning that the occurrence of RA did not lead to changes in plasma levels of DEFB135 (p = 0.93, supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

The incidence of RA is on the rise [3, 4]. Exploring the exact etiology and potential pathogenic mechanisms of RA to provide more effective treatment options for patients and to improve the prognosis is a current scientific issue that needs to be addressed. In this study, we used GWAS summary statistics from FinnGen, IEU and UKB and further performed proteomics MR analysis based on a large pQTL population to systematically evaluated the causal relationship between 4907 plasma proteins and RA.

Based on preliminary MR analysis of the FinnGen RA cohort, we found that SPAG11B was associated with the development of RA. Further external validation results based on the IEU and UKB RA cohorts were consistent. The higher the plasma level of SPAG11B, the lower the risk of RA. Reverse MR analysis revealed that SPAG11B plasma levels acquired changes when RA occurred. Specifically, the occurrence of RA caused a decrease in plasma levels of SPAG11B, suggesting its ability as a potential biomarker for predicting the occurrence of RA. The specific function of SPAG11B has not been clearly elucidated, but it is currently generally believed to be involved in the host’s innate defense and sperm maturation [21–24]. Wu et al. revealed that specific bacterial genera in the intestine might be involved in the occurrence of male infertility and reproductive inflammation by influencing SPAG11B [25]. An antibacterial study on lipopolysaccharide attacking the male reproductive tract of rats indicated that SPAG11B expression increased after LPS administration, suggesting its protective effect during male reproductive tract infections [26]. A study by Alexandre et al. demonstrated that SPAG11B had trypsin-like inhibitory activity and showed significant inhibition of trypsin-like activity, joint edema formation, and release of IL-6 and CXCL1/KC inflammatory factors through lentivirus-mediated heterologous expression of endogenous hSPAG11B/C in an animal model of arthritis [27]. The MR results in this study supported this experimental conclusion, and the OR value also suggested that elevated plasma levels of SPAG11B can reduce the risk of RA. Furthermore, a recent MR study has also identified that the plasma level of SPAG11B was negatively correlated with the risk of ankylosing spondylitis, with an OR value of 0.26 (95% CI 0.17–0.39) [28]. Based on these research results, we believe that the plasma level of SPAG11B may have a close association with autoimmune diseases, and its relationship with RA deserves further study.

For DEFB135, the preliminary MR analysis found an association between it and the risk of RA. Elevated plasma levels of DEFB135 could reduce the odds of developing RA, and it may play a protective role in the development of RA. However, the results were not reproduced during the external validation phase. The MR results of the IEU and UKB RA cohorts did not show significant correlation with the development of RA. The reasons for the difference might be population heterogeneity and the complexity of biological mechanisms. The allele frequencies, linkage disequilibrium structures or gene-environment interactions of different populations (such as race and geographical origin) are different, which may lead to the weakening or alteration of the association between IVs and exposure in external validation. Secondly, the environmental exposure (such as diet and lifestyle) of the external validation population is different from that of the initial study population, which may also affect the direction or intensity of the causal effect of the exposure-outcome relationship. Furthermore, the pathogenesis of RA is complex. The effect of DEFB135 may have a time window (such as affecting the outcome only at a specific stage of onset), and different age distributions of the externally validated population may also lead to differences in the effect. Further experiments or epidemiological studies are needed for verification. Notably, reverse MR results suggested that there was no reverse causality between DEFB135 and RA. In other words, the occurrence of RA did not cause changes in plasma levels of DEFB135. Forward MR results showed that an increase in the plasma level of DEFB135 could reduce the risk of RA, suggesting that DEFB135 may be an important molecular node affecting the pathogenesis of RA, which may bring new potential therapeutic targets and drug development ideas for RA. DEFB135 is a secreted antibacterial protein that is a member of the Beta defensin protein family [29]. The Beta defensin protein family is an important part of the mammalian innate defense system and plays an integral role in the specificity and reactivity of immune cells against inflammatory stimuli and pathogens [30, 31]. It was noted that the inhibitory effect of rNOD1 on Escherichia coli was through the activation of NF-κB signaling to induce DEFB135 expression [29]. By interacting with the chemokine receptor CCR6, Beta defensin protein attracted immature dendritic cells and memory T cells, thereby establishing a link with the adaptive immune system [32]. Several members of the Beta defensin protein family have been shown to be associated with autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjogren’s syndrome [33–36]. The MR results in this study suggested that DEFB135 may be a link in the pathogenesis of RA, but more research is needed before DEFB135 can be identified as a drug target for RA.

There were several limitations to this study. First, we only used a set of pQTL data to assess the association between plasma proteins and RA, and did not conduct external proteomics studies to validate these findings of ours. Secondly, we mainly investigated the effect of plasma causal proteins on the risk of RA in the population. However, the contribution of other components such as fatty acids [37], hormones [38] and gut microbiota [39] should not be overlooked. In addition, the exposure and outcome data used in this study were obtained from European populations. The proteomic data (deCODE) were Icelandic, the GWAS data (FinnGen, UKB and IEU) were European, but not homogeneous. There were potential population stratification bias and limited generalizability, and further research is needed to confirm the results.

Conclusion

Overall, our study investigated the causal relationship between plasma proteins and RA through forward and reverse MR analysis, revealing that increased plasma levels of SPAG11B and DEFB135 reduced the risk of RA. In addition, SPAG11B showed reverse causality with RA, suggesting that it had the potential to be a novel biomarker for RA. On the other hand, DEFB135 did not show reverse causality with RA and might be a potential therapeutic target for RA. However, it is necessary to establish RA cell lines and animal models for in vivo and in vitro experiments in the future to clarify the role of SPAG11B and DEFB135 in the progression of RA, and verify their potential as diagnostic markers or drug targets.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participants and researchers of the deCODE Genetics, FinnGen, Integrative Epidemiology Unit OpenGWAS and UK Biobank studies.

Abbreviations

- MR

Mendelian randomization

- GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

- SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- IVW

Inverse-variance weighted

- CI

Confidence interval

- IVs

Instrumental variables

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- FDR

False discovery rate

Author contributions

KL designed the study. KL, QL and WLacquired and analyzed the data. KL, RS and YL drafted the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or report writing.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary materials/references, and further inquiries can contact the authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a secondary analysis of publicly available GWAS datasets that have prior ethical approval, so no informed consent or ethical approval is required for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McInnes IB, Schett G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong LE, Wechalekar MD, Kutyna MM, et al. IDH mutant myeloid neoplasms are associated with seronegative rheumatoid arthritis and innate immune activation. Blood. 2024;143(18):1873–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Finckh A, Gilbert B, Hodkinson B, et al. Global epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(10):591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Matteo A, Bathon JM, Emery P. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2023;402(10416):2019–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Xu F, Ruan X, et al. Therapeutic targets for inflammatory bowel disease: proteome-wide Mendelian randomization and colocalization analyses. EBioMedicine. 2023;89:104494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng X, Wu WY, Onwuka JU, et al. Lung cancer risk discrimination of prediagnostic proteomics measurements compared with existing prediction tools. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;115(9):1050–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan S, Xu F, Zhang H, et al. Proteomic insights into modifiable risk of venous thromboembolism and cardiovascular comorbidities. J Thromb Haemost. 2024;22(3):738–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang C, Fagan AM, Perrin RJ, Rhinn H, Harari O, Cruchaga C. Mendelian randomization and genetic colocalization infer the effects of the multi-tissue proteome on 211 complex disease-related phenotypes. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo H, Huemer MT, Petrera A, et al. Association of plasma proteomics with incident coronary heart disease in individuals with and without type 2 diabetes: results from the population-based KORA study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira MB, Kobayashi M, Costa RQ, et al. Unsupervised clustering to differentiate rheumatoid arthritis patients based on proteomic signatures. Scand J Rheumatol. 2023;52(6):619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escal J, Neel T, Hodin S et al. Proteomics analyses of human plasma reveal triosephosphate isomerase as a potential blood marker of methotrexate resistance in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024;63(5):1368–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. JAMA. 2021;326(16):1614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan QQ, Wang H, Su WM, et al. TBK1, a prioritized drug repurposing target for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: evidence from druggable genome Mendelian randomization and Pharmacological verification in vitro. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson PC, Choi HK, Do R, Merriman TR. Insight into rheumatological cause and effect through the use of Mendelian randomization. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(8):486–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Li Q, Cao Z, Wu J. Multicenter proteome-wide Mendelian randomization study identifies causal plasma proteins in melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferkingstad E, Sulem P, Atlason BA, et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat Genet. 2021;53(12):1712–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mounier N, Kutalik Z. Bias correction for inverse variance weighting Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol. 2023;47(4):314–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hao X, Ren C, Zhou H, Li M, Zhang H, Liu X. Association between Circulating immune cells and the risk of prostate cancer: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1358416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed MU, Azad MAK, Li M, et al. Polymyxin-Induced metabolic perturbations in human lung epithelial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65(9):e0083521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan S, Carter P, Mason AM, Burgess S, Larsson SC. Coffee consumption and cardiovascular diseases: A Mendelian randomization study. Nutrients. 2021;13:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribeiro CM, Queiroz DB, Patrao MT, et al. Dynamic changes in the spatio-temporal expression of the beta-defensin SPAG11C in the developing rat epididymis and its regulation by androgens. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;404:141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu SG, Zou M, Yao GX, et al. Androgenic regulation of beta-defensins in the mouse epididymis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014;12:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drabovich AP, Jarvi K, Diamandis EP. Verification of male infertility biomarkers in seminal plasma by multiplex selected reaction monitoring assay. Mol Cell Proteom. 2011;10(12):M110004127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radhakrishnan Y, Hamil KG, Tan JA, et al. Novel partners of SPAG11B isoform D in the human male reproductive tract. Biol Reprod. 2009;81(4):647–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu X, Mei J, Qiao S, Long W, Feng Z, Feng G. Causal relationships between gut microbiota and male reproductive inflammation and infertility: insights from Mendelian randomization. Med (Baltim). 2025;104(17):e42323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswas B, Yenugu S. Antimicrobial responses in the male reproductive tract of lipopolysaccharide challenged rats. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65(6):557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denadai-Souza A, Ribeiro CM, Rolland C, et al. Effect of tryptase Inhibition on joint inflammation: a Pharmacological and lentivirus-mediated gene transfer study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Z, Liu C, Feng S, et al. Identification of novel protein biomarkers and therapeutic targets for ankylosing spondylitis using human Circulating plasma proteomics and genome analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2024;416(28):6357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo M, Wu F, Zhang Z, et al. Characterization of rabbit Nucleotide-Binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1) and the role of NOD1 signaling pathway during bacterial infection. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patil AA, Cai Y, Sang Y, Blecha F, Zhang G. Cross-species analysis of the mammalian beta-defensin gene family: presence of syntenic gene clusters and Preferential expression in the male reproductive tract. Physiol Genomics. 2005;23(1):5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schutte BC, Mitros JP, Bartlett JA, et al. Discovery of five conserved beta -defensin gene clusters using a computational search strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(4):2129–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang D, Chertov O, Bykovskaia SN, et al. Beta-defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286(5439):525–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardner M, Tuckwell D, Kostikova A et al. Analysis of serum proteomics data identifies a quantitative association between beta-defensin 2 at baseline and clinical response to IL-17 Blockade in psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open 2023;9(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Kolbinger F, Loesche C, Valentin MA, et al. beta-Defensin 2 is a responsive biomarker of IL-17A-driven skin pathology in patients with psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3):923–e932928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vordenbaumen S, Fischer-Betz R, Timm D, et al. Elevated levels of human beta-defensin 2 and human neutrophil peptides in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19(14):1648–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaneda Y, Yamaai T, Mizukawa N, et al. Localization of antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensins in minor salivary glands with Sjogren’s syndrome. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117(5):506–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao X, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Ma W, Yao X. The causal impact of saturated fatty acids on rheumatoid arthritis: a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1337256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malik S, Chakraborty D, Agnihotri P, Sharma A, Biswas S. Mitochondrial functioning in rheumatoid arthritis modulated by Estrogen: Evidence-based insight into the sex-based influence on mitochondria and disease. Mitochondrion. 2024;76:101854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao X, Zhang R, Wang X. The gut-joint axis: genetic evidence for a causal association between gut microbiota and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis and seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Med (Baltim). 2024;103(8):e37049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary materials/references, and further inquiries can contact the authors.