Abstract

Objective

This study aims to preliminarily evaluate the early safety and efficacy of one-stage repair of residual aortic dissection using dense metal mesh stents combined with improved release and post-processing techniques.

Methods

A prospective, single-center, single-arm clinical trial was designed and implemented, enrolling patients with residual aortic dissection to undergo metal mesh stent implantation under guidance of stent release and post-processing techniques. Patients received aortic CTA follow-up at 30 days post-surgery to assess early safety and efficacy.

Results

A total of 25 patients were enrolled, 14 in the (sub)acute phase and 11 in the chronic phase. No postoperative deaths, reinterventions, or aortic-related adverse events like malperfusion or ischemia were reported. The immediate technical success rate was 100%. For (sub)acute cases, the true lumen volume increased by 176.10%, while the false lumen decreased by 83.95%. False lumen thrombosis was grade II in two patients (14.29%), grade III in seven (50.00%), and grade IV in five (35.71%). For chronic cases, the true lumen volume increased by 96.92%, while the false lumen decreased by 73.43%. Thrombosis was grade II in three patients (27.27%), grade III in five (45.45%), and grade IV in three (27.27%). Postoperative aortic CTA showed that all visceral artery branches remained patent, and high-risk ischemic branches were converted to non-high-risk.

Conclusions

Preliminary results suggest that dense mesh stents combined with release and post-processing techniques have acceptable early safety and efficacy. For acute and chronic residual aortic dissection patients with visceral artery branch involvement, this method may offer an alternative treatment option. Registration no. ChiCTR2200055277.

Keywords: Residual aortic dissection, endovascular repair, dense mesh stent, release and post-processing technique, aortic remodeling

Introduction

Acute aortic dissection (AAD) is a critical condition in cardiovascular surgery, with more than half of the cases involving the entire length of the aorta.1,2 Due to the presence of aortic branches, traditional surgical and endovascular treatments cannot achieve a one-stage complete repair of the aorta during the initial intervention, resulting in the persistence of residual aortic dissection (RAD) in the distal aorta.3,4

In the early stages, secondary tears in the dissection can act as protective factors, but once the primary tear is sealed, these secondary tears become dangerous, keeping the false lumen patent. Approximately 50% of patients develop progressive aortic enlargement after the initial repair, leading to complications like thoracoabdominal aneurysms or malperfusion, often requiring reinterventions.5–7 RAD involving visceral artery branches significantly complicates further interventions.

Endovascular repair is one of the primary treatment options for RAD. In recent years, several endovascular techniques and devices have been developed to address the complexities of RAD involving visceral artery branches.8–10 However, no optimal repair strategy has been universally accepted. 11

An ideal repair strategy should allow for a minimally invasive, simple, safe, and effective one-stage repair of RAD. Dense metal mesh stents have been used in treating aortic dissection but with inconsistent results, limiting their application. 12 However, their ability to preserve branch vessel blood flow still shows potential for treating aortic dissection. This study was based on a specific type of dense mesh stent, with the design of four release and post-processing techniques, and aimed to preliminarily evaluate the safety and efficacy of one-stage repair of RAD while preserving major branch blood supply and promoting physiological remodeling of the aorta.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study's data were obtained from a prospective, multi-center, open-label, and single-arm clinical trial. It was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Registration No. ChiCTR2200055277) and approved by the ethics committee of the center [(2023) No. (2)]. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent prior to participation. Inclusion criteria: (1) age 18–80 years, (2) diagnosed with RAD based on CTA or intraoperative angiography, (3) RAD extends to the renal arteries or beyond, (4) a prosthetic graft was replaced or a covered stent was implanted at the proximal aorta during the initial repair, and (5) patients voluntarily participated and signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria: (1) no suitable vascular access, (2) known allergies to nickel-titanium alloy, contrast agents, antiplatelet, or anticoagulant drugs, (3) severe heart failure (NYHA III or above), and (4) connective tissue diseases affecting the aorta. Patients received dense mesh stents combined with release and post-processing techniques for RAD repair. Postoperative CTA at 30 days evaluated key outcomes. Primary safety endpoints: (1) major adverse events (MAEs) within 30 days post-surgery, including organ malperfusion, limb ischemia, spinal cord ischemia, reintervention, and all-cause mortality. Primary efficacy endpoint: The rate of false lumen thrombosis in RAD 30 days postoperatively (Grade I: volume reduction <30%; Grade II: 30%–70%; Grade III: >70% but <100%; and Grade IV: complete thrombosis). Immediate technical success is defined as successful stent implantation and expansion with good morphology and accurate positioning, without severe complications requiring surgical intervention, and no intraoperative mortality. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975), as revised in 2024. The reporting of this study conforms to CONSORT guidelines. 13

Patients

From February 2023 to October 2023, a total of 29 patients were screened at Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, and 25 patients underwent dense mesh stent implantation guided by release and post-processing techniques, including 14 (sub)acute cases and 11 chronic cases. All patients completed a 30-day postoperative aortic CTA follow-up.

Devices

The trial used a dense mesh stent (manufactured by Shanghai Qigong Medical Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), composed of nickel–titanium alloy. The stent's structure includes thick metal wires as strengthening ribs, forming the framework of the stent, while finer wires are woven into a mesh structure with an approximate porosity of 70%. The release mechanism of the stent is positioned at both ends, allowing adjustment of its length through the delivery system. The stent's diameter and length are inversely proportional, depending on its size. Stents are classified into straight-tube or branched types, and further into main-body stents (for the aorta) or peripheral stents (for the iliac arteries) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the dense mesh stent and delivery system. (A) Natural state; (B) encapsulated state; (C) ex vivo simulation state; and (D) stent delivery system.

Unlike covered stents, which directly seal the intimal tear, the dense mesh stent theoretically expands the true lumen through extensive and uniform radial support, promoting the reattachment of the aortic intima and adventitia. In this process, the aortic adventitia acts as a biological patch to seal the residual intimal tears of the dissected aorta. Over time, endothelialization of the stent's inner surface further reinforces this repair mechanism. Since the false lumen pressure in patients with RAD is lower than before the initial repair, and the distal tear is generally smaller than the primary tear, this mechanism is feasible in most cases. Additionally, due to the porous nature of the dense mesh stent, it allows blood flow to pass through, enabling direct coverage of the aortic branch region while maintaining long-term patency of the branch vessels.

Stent release and post-processing techniques

Preoperative aortic angiography was performed to confirm the location of the lesion, and a guidewire was advanced from the true lumen into the false lumen through the distal tear with a guiding catheter pre-positioned for use.

Precise stent positioning

Based on preoperative aortic CTA measurements, the appropriate stent size is selected. The position of the delivery system is determined according to the expected final position, diameter, and length after release.

Segmental compression release

After the delivery system reaches the predetermined position, the sheath is gradually retracted. The proximal and distal ends of the stent are compressed to the target diameter, ensuring pre-release shaping. The stent is released proximally by overlapping ∼3 cm with the previous stent, followed by distal release. Ensure that the overlap zone does not involve the visceral artery branch segment.

Balloon-assisted expansion

If the stent is limited in expansion, or there are “bird-beak” deformations at the proximal and distal ends, a non-compliant balloon is used for post-expansion to achieve ideal shaping.

Accurate closure of the false lumen tear

After stent implantation, intraoperative angiography is performed to assess branch vessel perfusion and the effectiveness of the procedure. When angiography after stent deployment and balloon molding indicates the presence of significant residual tears and persistent flow outside the stent, embolic materials (such as coils) are delivered through the pre-positioned catheter in the false lumen to precisely seal the tear. The operation is completed once the false lumen has disappeared or only minimal leakage remains (Figure 2 and Supplemental File 1, https://youtu.be/XMNfOv6UJck).

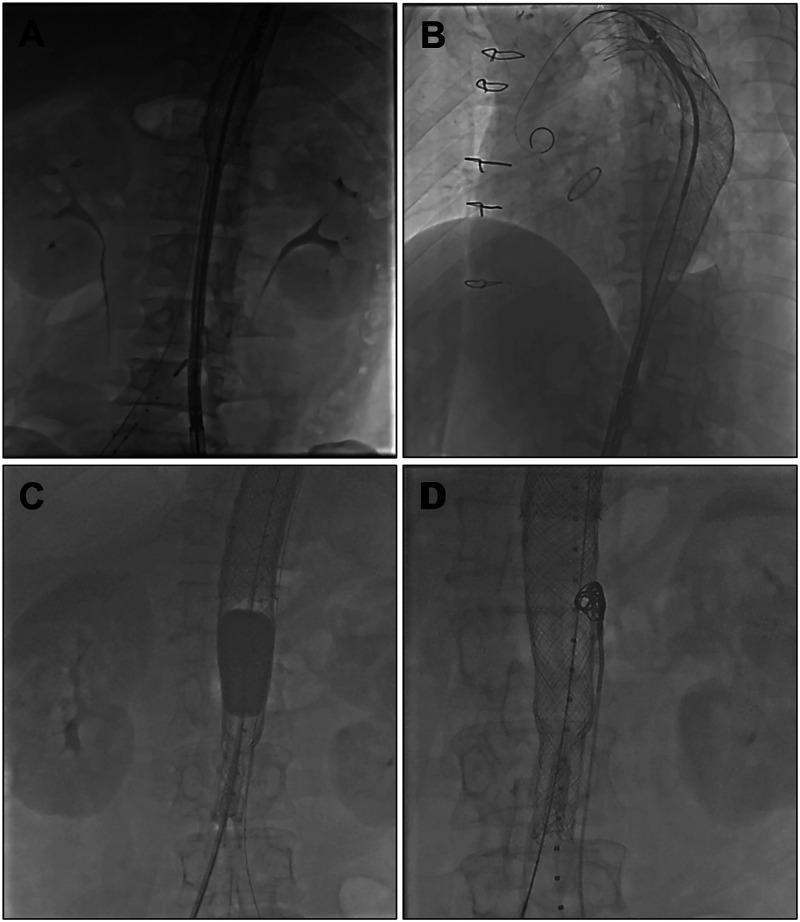

Figure 2.

Stent release and post-processing techniques. (A) Precise stent positioning; (B) segmental compression release; (C) balloon-assisted expansion; and (D) accurate closure of the false lumen tear.

Postoperatively, patients are prescribed clopidogrel 75 mg daily for three months and aspirin 100 mg daily for 6 months.

Aortic CTA measurements

To minimize radiation exposure, preoperative aortic CTA within 30 days before stent implantation is used for baseline measurements. Aortic CTA reconstruction and measurements are performed using MIMICS 21 software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). The aorta is divided into three segments: Segment A: From the distal edge of the stent-graft to the upper edge of the celiac trunk. Segment B: From the upper edge of the celiac trunk to the lower edge of the renal artery. Segment C: From the lower edge of the renal artery to the distal end of the common iliac artery. Measurements included the aortic length of segments A, B, and C, length of the iliac arteries, aortic and true lumen diameters at the distal end of the stent-graft, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower edge of the renal arteries. Routine measurements of the following parameters are performed before and after surgery: long diameter, area of true and false lumen at the distal end of the stent-graft, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower edge of the renal arteries; volumes of the true and false lumens in segments A, B, and C of the aorta. Aortic length measurements are taken along the vessel centerline, excluding thrombosed portions from false lumen areas and volumes (Figure 3).

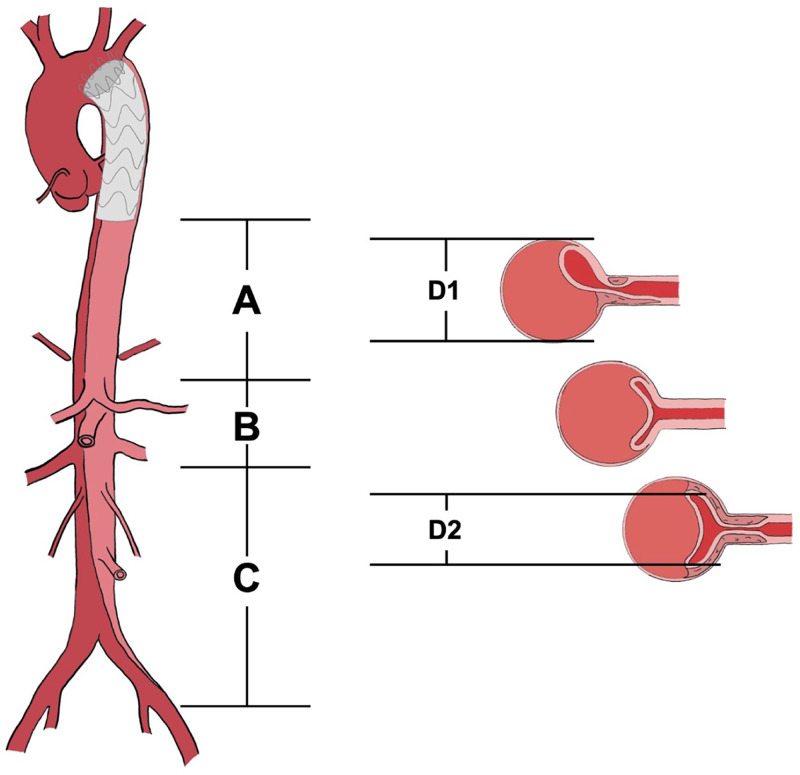

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of aortic measurements. (A–C) Schematic diagram of the segments of the aorta; D1: aortic diameter; D2: the diameter of the true lumen of the aorta. D1 and D2 are used to confirm the post-deployment diameter of the stent.

Our measurement principles followed the society for vascular surgery (SVS) and society of thoracic surgeons (STSs) reporting standards for type B aortic dissections. 14 The aortic CTA images in DICOM format were imported into MIMICS software for analysis. The region of interest was selected, and thresholding was applied to segment the aorta based on Hounsfield Unit values. Manual adjustments and region-growing techniques were used to refine the segmentation, ensuring accurate differentiation between the true lumen, false lumen, and the aortic wall.

The centerline of the aorta was automatically or manually generated to serve as a reference for subsequent measurements. Along this centerline, the total aortic length, as well as the lengths of predefined aortic segments, were measured. Cross-sectional planes perpendicular to the centerline were created at specified locations to assess diameters. The diameters of the aorta and the true lumen were measured at these planes.

For area measurement, cross-sectional slices were analyzed at predefined locations, where the true lumen and false lumen were manually outlined or automatically extracted. The software provided calculated areas based on pixel distribution. Volumetric measurement was performed through three-dimensional reconstruction of the aorta, true lumen, and false lumen using the segmented data. The volume of each lumen was derived by integrating the cross-sectional areas along the aortic length.

All measured parameters were reviewed for accuracy, and adjustments were made as needed. The final dataset, including aortic length, diameters, areas, and volumes, was then exported for further statistical analysis.

Laboratory and imaging assessments

Laboratory tests and imaging (except for aortic CTA) are performed within 7 days before surgery and again within 7 days postoperatively.

Definitions

The acute phase is defined as occurring within 14 days of aortic dissection onset, the subacute phase within 15–90 days, and the chronic phase beyond 90 days. Malperfusion syndrome is defined as follows 11 : gastrointestinal malperfusion: abdominal pain combined with CTA evidence of celiac trunk or superior mesenteric artery occlusion or severe stenosis. Renal malperfusion: oliguria or anuria combined with aortic CTA showing renal perfusion defects. Limb malperfusion: pain in the extremities with loss of arterial pulses (brachial or femoral). Spinal ischemia: partial or complete sensory or motor function loss unrelated to limb ischemia.

Visceral artery branch ischemia is classified based on Hiroshi's criteria. 15 The perfusion types of visceral artery branches are classified into three categories. In type I, the dissection does not extend to the branch artery. Type I-a refers to branch vessels perfused by the true lumen of the aorta without being affected by the false lumen. Type I-b refers to branch vessels perfused by the true lumen of the aorta, but the true lumen is compressed by the false lumen. Type I-c refers to branch vessel ostia that are occluded or significantly narrowed due to coverage by the intimal flap. In type II, the dissection extends into the branch artery. Type II-a refers to distal branch vessels with sufficient secondary tears, resulting in perfusion of the branch false lumen being comparable to or greater than that of the branch true lumen. Type II-b refers to distal branch vessels with insufficient or no secondary tears, leading to significantly less or absent perfusion of the branch false lumen compared to the branch true lumen. Type II-b-1 refers to cases where the branch true lumen is not compressed by the branch false lumen, and perfusion remains normal, whereas type II-b-2 refers to cases where the branch true lumen is compressed by the branch false lumen, leading to significantly reduced perfusion. In type III, the dissection causes avulsion of the branch vessel ostium. Type III-a refers to branch vessels perfused by a patent aortic false lumen, with or without branch vessel dissection. Type III-b refers to branch true lumens compressed by the branch false lumen, significantly reducing perfusion from the aortic false lumen. Type III-c refers to branch vessels perfused by the aortic false lumen, but perfusion is significantly reduced due to thrombosis within the false lumen. Among these subtypes, I-b, I-c, II-b-2, III-b, and III-c are classified as high-risk types.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation was performed using PASS software 2020 (NCSS LLC., Kaysville, UT, USA). Based on prior literature, assuming a 30-day Grade III or above false lumen thrombosis rate of 50% and a target rate of 22%, with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%, the required sample size was 20 patients. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Shapiro-Wilk and Q-Q plot methods were used to assess data normality. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and categorical data were presented as numbers (percentages). Independent sample t-tests were used to compare means between acute/subacute and chronic patients, and paired t-tests were used for pre- and post-operative comparisons. A chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical data. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

From February 2023 to October 2023, a total of 29 patients were screened at Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, and 25 patients underwent dense mesh stent implantation guided by release and post-processing techniques. Among the excluded patients, one lacked an anatomical access route, one had severe renal impairment with serum creatinine levels exceeding 2.5 times the upper normal limit and was deemed unsuitable for inclusion by the investigators, one had a malignant tumor and was scheduled for chemotherapy, and one had severe heart failure (NYHA class IV). Five patients (20.00%) had RAD extending distally to zone 9, 11 patients (44.00%) to zone 10, and nine patients (36.00%) to zone 11.

Of the 25 enrolled patients, 23 (92.00%) were male, with a mean age of 51.4 years. The cohort included 14 (56.00%) acute/subacute cases and 11 (44.00%) chronic cases. Thirteen patients (52.00%) had type A dissections, and 12 patients (48.00%) had type B dissections. For type A dissection, the initial repair involved ascending aortic replacement or aortic root replacement combined with total arch replacement and frozen elephant trunk implantation. For type B dissection, the initial repair was TEVAR. In (sub)acute cases, the average interval from onset to enrollment surgery was 11.1 days, and from initial repair to enrollment surgery was 6.0 days. In chronic cases, the average interval from onset to surgery was 1179.5 days, and from initial repair to enrollment surgery was 1177.4 days. Preoperative complications included 1 patient (4.00%) with gastrointestinal malperfusion and 1 patient (4.00%) with lower limb malperfusion (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variables | Acute (n = 14) | Chronic (n = 11) | Total (n = 25) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval (days) | 11.14 ± 5.90 | 1179.45 ± 1339.97 | 525.20 ± 1048.09 | 0.016 |

| Male | 13 (92.90%) | 10 (90.90%) | 23 (92.00%) | 1.000 |

| Age (years) | 54.86 ± 10.27 | 46.91 ± 10.27 | 51.36 ± 10.83 | 0.067 |

| Hypertension | 10 (71.40%) | 10 (90.90%) | 20 (80.00%) | 0.341 |

| TAAD | 6 (42.90%) | 7 (63.60%) | 13 (52.00%) | 0.428 |

| From TL | ||||

| CT | 11 (78.6%) | 7 (63.6%) | 18 (72.0%) | 0.656 |

| SMA | 14 (100.0%) | 10 (90.9%) | 24 (96.0%) | 0.440 |

| RRA | 12 (85.7%) | 10 (90.9%) | 22 (88.0%) | 1.000 |

| LRA | 8 (57.1%) | 8 (72.7%) | 16 (64.0%) | 0.677 |

| Malperfusion | ||||

| Mesenteric | 1 (7.14%) | 0 | 1 (4.00%) | 1.000 |

| Peripheral | 1 (7.14%) | 0 | 1 (4.00%) | 1.000 |

| WBC (109/L) | 10.64 ± 3.97 | 8.15 ± 2.22 | 9.54 ± 3.49 | 0.077 |

| Hb (g/L) | 122.93 ± 28.92 | 143.64 ± 16.40 | 132.04 ± 25.98 | 0.035 |

| DD (ng/mL) | 3290.11 ± 4756.29 | 650.40 ± 422.53 | 1900.79 ± 3460.83 | 0.135 |

| ALT (U/L) | 45.86 ± 40.76 | 26.64 ± 19.07 | 37.40 ± 33.86 | 0.135 |

| AST (U/L) | 24.93 ± 11.76 | 22.55 ± 10.25 | 23.88 ± 10.96 | 0.600 |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 96.43 ± 32.97 | 93.10 ± 19.24 | 94.96 ± 27.31 | 0.769 |

ALT: glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; AST: glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; CT: celiac trunk; DD: D-dimer; Hb: hemoglobin; Interval: time interval between symptom onset and surgery; LRA: left renal artery; RRA: right renal artery; Scr: Serum creatinine; SMA: superior mesenteric artery; TAAD: type A aortic dissection; TL: true lumen; WBC: white blood cell counts.

Safety

No deaths occurred during the 30-day follow-up. None of the patients required a second surgery, nor did any develop organ malperfusion, limb ischemia, spinal cord ischemia, or other aortic-related complications.

Efficacy

The average operative time was 153.60±86.74 minutes, with 188.57±95.91 minutes for (sub)acute phase patients and 109.09 ± 47.00 minutes for chronic phase patients (P = 0.013). On average, each patient received 4.08 ± 1.50 stents, with (sub)acute-phase patients receiving 4.07 ± 1.59 stents and chronic-phase patients receiving 4.37 ± 1.02 stents (P = 0.591). The immediate technical success rate was 100%.

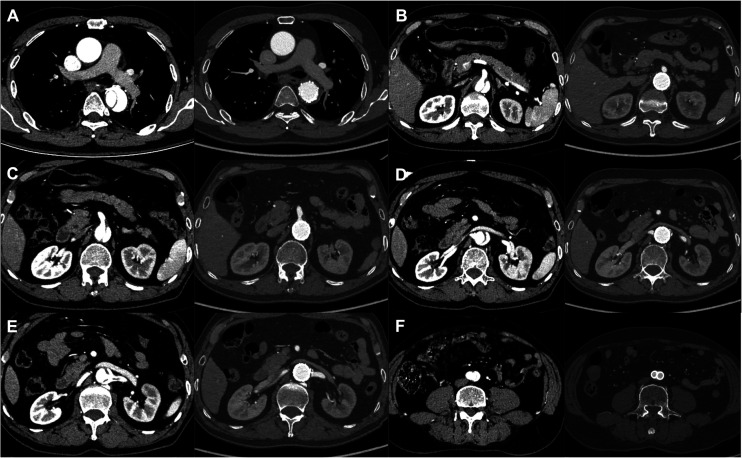

For (sub)acute cases, the true lumen occupied 51.06% preoperatively and 92.40% postoperatively, with an average increase of 176.10% in true lumen volume and an average decrease of 83.95% in false lumen volume. At the distal end of the stent-graft, the upper edge of the celiac trunk, and the lower edge of the renal artery, the true lumen area increased by an average of 106.07%, 183.03%, and 274.47%, respectively. At the same levels, the false lumen area decreased by an average of 71.52%, 87.13%, and 90.51%, respectively. Two patients (14.29%) achieved grade II false lumen thrombosis, seven patients (50.00%) achieved grade III, and five patients (35.71%) achieved grade IV thrombosis (Table 2 and Figure 4, with Supplemental File 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative-aortic remodeling of (sub)acute patients.

| Variables | Pre (n = 14) | Post (n = 14) | Rate (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD (mm) | 30.33 ± 4.60 | 29.71 ± 6.27 | −1.55 ± 17.13 | 0.648 |

| CAD | 28.63 ± 1.99 | 29.23 ± 2.68 | 2.18 ± 7.34 | 0.298 |

| RAD | 22.45 ± 2.11 | 24.30 ± 2.75 | 8.47 ± 10.01 | 0.009 |

| STA (mm2) | 295.40 ± 116.58 | 522.41 ± 122.99 | 106.07 ± 106.57 | <0.001 |

| CTA | 217.18 ± 54.87 | 575.00 ± 106.32 | 183.03 ± 100.7 | <0.001 |

| RTA | 165.89 ± 94.01 | 426.96 ± 101.28 | 274.47 ± 317.5 | <0.001 |

| SFA | 227.44 ± 241.74 | 71.43 ± 136.35 | −71.52 ± 36.86 | 0.007 |

| CFA | 269.96 ± 117.07 | 39.46 ± 72.70 | −87.13 ± 24.33 | <0.001 |

| RFA | 164.96 ± 93.72 | 15.38 ± 40.08 | −90.51 ± 23.78 | <0.001 |

| ATV (cm3) | 33.16 ± 23.35 | 87.19 ± 45.50 | 232.73 ± 223.41 | <0.001 |

| BTV | 8.05 ± 2.94 | 19.97 ± 6.17 | 204.77 ± 227.91 | <0.001 |

| CTV | 24.50 ± 11.77 | 44.14 ± 6.36 | 125.36 ± 122.07 | <0.001 |

| TTV | 65.71 ± 33.25 | 151.29 ± 42.80 | 176.1 ± 161.55 | <0.001 |

| AFV | 39.84 ± 33.00 | 7.83 ± 11.05 | −84.18 ± 16.65 | 0.001 |

| BFV | 9.50 ± 5.73 | 1.29 ± 2.74 | −89.39 ± 22.62 | <0.001 |

| CFV | 18.89 ± 13.75 | 5.28 ± 6.51 | −76.25 ± 25.23 | <0.001 |

| TFV | 68.24 ± 38.08 | 14.40 ± 18.29 | −83.95 ± 15.82 | <0.001 |

SAD, CAD, and RAD: aortic diameter at the lower margin of the covered stent, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower margin of the renal artery, respectively. STA, CTA, and RTA: aortic true lumen areas at the lower margin of the covered stent, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower margin of the renal artery, respectively. SFA, CFA, and RFA: aortic false lumen areas at the lower margin of the stent, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower margin of the renal artery, respectively. ATV, BTV, CTV, and TTV: aortic true volumes of A, B, C segments and total aorta. AFV, BFV, CFV, and TFV: aortic false volumes of A, B, C segments and total aorta. Rate: rate of change.

Figure 4.

The preoperative and postoperative cross-sectional areas of the aorta at the mid-thoracic aorta level (A), celiac trunk level (B), superior mesenteric artery level (C), right renal artery level (D), left renal artery level (E), and iliac artery level (F).

For chronic cases, the true lumen accounted for 54.66% preoperatively and 87.34% postoperatively, with an average increase of 96.92% in true lumen volume and an average decrease of 73.43% in false lumen volume. At the distal end of the stent-graft, the upper edge of the celiac trunk, and the lower edge of the renal artery, the true lumen area increased by an average of 19.70%, 122.99%, and 195.71%, respectively. At the same levels, the false lumen area decreased by an average of 84.19%, 70.76%, and 81.52%, respectively. Three patients (27.27%) achieved grade II false lumen thrombosis, five patients (45.45%) achieved grade III, and three patients (27.27%) achieved grade IV thrombosis (Table 3 and Figure 4, with Supplemental File 2).

Table 3.

Postoperative-aortic remodeling of chronic patients.

| Variables | Pre (n = 11) | Post (n = 11) | Rate (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD (mm) | 28.75 ± 8.31 | 28.70 ± 8.23 | 1.33 ± 13.01 | 0.963 |

| CAD | 31.77 ± 6.40 | 30.51 ± 6.25 | −3.27 ± 11.14 | 0.274 |

| RAD | 25.46 ± 5.18 | 27.28 ± 5.65 | 7.82 ± 12.39 | 0.056 |

| STA (mm2) | 373.27 ± 126.31 | 424.42 ± 156.86 | 19.7 ± 42.7 | 0.253 |

| CTA | 241.94 ± 84.71 | 494.30 ± 106.91 | 122.99 ± 86.94 | <0.001 |

| RTA | 169.96 ± 58.39 | 460.15 ± 101.18 | 195.71 ± 97.66 | <0.001 |

| SFA | 68.39 ± 182.97 | 3.36 ± 11.14 | −84.19 ± 27.39 | 0.266 |

| CFA | 356.40 ± 247.15 | 126.73 ± 188.05 | −70.76 ± 29.43 | <0.001 |

| RFA | 212.16 ± 185.04 | 69.18 ± 129.81 | −81.52 ± 27.98 | <0.001 |

| ATV (cm3) | 34.25 ± 18.42 | 59.67 ± 26.64 | 82.59 ± 49.24 | <0.001 |

| BTV | 8.71 ± 2.85 | 19.92 ± 5.68 | 141.8 ± 77.76 | <0.001 |

| CTV | 23.83 ± 10.68 | 44.29 ± 9.89 | 121.14 ± 98.25 | <0.001 |

| TTV | 66.79 ± 25.71 | 123.89 ± 33.30 | 96.92 ± 50.93 | <0.001 |

| AFV | 23.88 ± 22.79 | 5.53 ± 4.60 | −68.22 ± 21.22 | 0.011 |

| BFV | 12.72 ± 10.78 | 4.59 ± 8.66 | −71.65 ± 35.42 | 0.001 |

| CFV | 27.23 ± 21.28 | 9.51 ± 10.01 | −68.73 ± 20.28 | 0.002 |

| TFV | 63.83 ± 43.79 | 19.63 ± 17.63 | −73.43 ± 18.37 | 0.001 |

SAD, CAD, RAD: aortic diameter at the lower margin of the covered stent, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower margin of the renal artery, respectively. STA, CTA, RTA: aortic true lumen areas at the lower margin of the covered stent, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower margin of the renal artery, respectively. SFA, CFA, RFA: aortic false lumen areas at the lower margin of the stent, upper margin of the celiac trunk, and lower margin of the renal artery, respectively. ATV, BTV, CTV, TTV: aortic true volumes of A, B, C segments and total aorta. AFV, BFV, CFV, TFV: aortic false volumes of A, B, C segments and total aorta. Rate: rate of change.

Visceral arteries

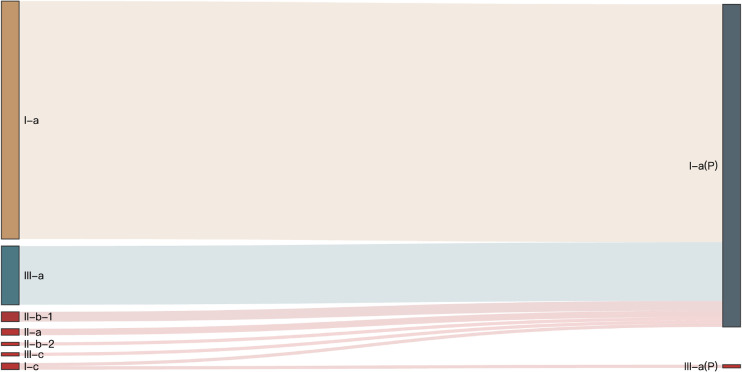

Postoperative aortic CTA indicated that all visceral artery branches remained patent, with high-risk ischemic branches converting to non-high-risk types (Figure 5). Perioperative ultrasound showed no significant changes in the width and flow velocity of the visceral artery branches (Table 4).

Figure 5.

Conversion of visceral artery perfusion type. I-c, II-b-2, and III-c represent high-risk ischemic types, while P indicates the postoperative branch type.

Table 4.

Postoperative–visceral arterial vascular ultrasound.

| Variables | Pre (n = 25) | Post (n = 25) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMAW (cm) | 0.59 ± 0.14 | 0.63 ± 0.12 | 0.188 |

| SMAPSV (cm/s) | 193.50 ± 87.30 | 173.85 ± 73.05 | 0.416 |

| LRAW | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.097 |

| LRAPSV | 155.25 ± 69.99 | 119.42 ± 54.21 | 0.161 |

| RRAW | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 0.48 ± 0.12 | 0.514 |

| RRAPSV | 154.75 ± 47.09 | 149.58 ± 120.73 | 0.851 |

LRAW: left renal artery blood flow width; LRAPSV: peak systolic flow velocity of left renal artery; RRAW: right renal artery blood flow width; RRAPSV: peak systolic flow velocity of right renal artery; SMAW: superior mesenteric artery blood flow width; SMAPSV: peak systolic flow velocity of superior mesenteric artery.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that the dense mesh stent combined with release and post-processing techniques for one-stage repair of RAD have demonstrated favorable early safety and efficacy. None of the patients experienced new onset organ malperfusion, limb ischemia, spinal cord ischemia, secondary surgery, or death within 30 days postoperatively. Postoperative aortic CTA showed that the true lumen volume increased by an average of 141.26%, and the false lumen volume decreased by an average of 79.32%. High-risk ischemic visceral artery branches were converted to non-high-risk types, and all visceral artery branches remained patent.

Currently available endovascular techniques for treating RAD include TEVAR, PETTICOAT, STABILISE, Knickerbocker, Candy-Plug, false lumen embolization, parallel grafting, and F/B-EVAR. Techniques like PETTICOAT and STABILISE address the inability of traditional stent-grafts to span visceral artery branches, and their use is gradually increasing. False lumen embolization techniques isolate retrograde blood flow, promoting aortic remodeling. The parallel graft technique, however, has a high incidence of endoleaks, making it more suitable as a supplemental treatment in emergency settings. 16 F/B-EVAR is primarily used for aneurysmal aortic disease due to the limitations of its large delivery system. In this study, we compare the results with techniques like PETTICOAT, STABILISE, and other clinical trials using dense mesh stents.

Safety

A modified PETTICOAT technique 17 study included 35 patients with acute type B aortic dissection. Within 30 days postoperatively, five patients (14.3%) experienced acute kidney injury, one patient (2.8%) developed paraplegia, one patient (2.8%) experienced aortic rupture, and two patients (5.7%) required re-intervention. In another report on E-PETTICOAT, 18 16 patients with acute or subacute type B aortic dissection were treated, with one case (7%) of intraoperative aortic rupture and no other major aortic complications in the early postoperative period. A study on the STABILISE technique reported 19 a 2% mortality rate, a 5% incidence of paraplegia, and 2% visceral malperfusion among 41 patients with acute type B aortic dissection. A clinical study on dense mesh stents 20 included 23 patients with complicated type B aortic dissection, and none experienced device-related neurological or systemic complications. During the one-year follow-up, no patients required re-intervention. In our study, none of the patients experienced new organ malperfusion, limb ischemia, spinal cord ischemia, secondary surgery, or death within 30 days postoperatively.

The use of covered stents in PETTICOAT and STABILISE techniques increases the risk of spinal cord ischemia due to the longer covered length compared to traditional TEVAR, which can lead to paraplegia. Unlike covered stents, dense mesh stents are more effective in preserving blood supply to aortic branches. 21 Even branches originating from the false lumen can retain effective blood flow after reattachment of the inner and outer membranes, resulting in a lower rate of paraplegia (none observed so far in our study). Additionally, the lower porosity of dense mesh stents allows for more uniform aortic support, making them more resistant to rupture during balloon expansion. In addition, the metal structure of covered stents and the high porosity of bare metal stents used in techniques like PETTICOAT result in uneven stress distribution across the aorta, which may lead to aortic rupture during balloon expansion. In contrast, the lower porosity of dense mesh stents ensures a more uniform distribution of support force on the aorta, allowing it to withstand greater expansion pressures. In fact, during clinical trials, instances of non-compliant aortic balloons rupturing due to excessive pressure were observed, yet the aorta remained intact and safe in these cases.

Efficacy

The presence of a residual false lumen after the initial repair of aortic dissection can lead to progressive aortic dilation and rupture in some patients. 22 Severely compressed true lumens can also impair blood flow to the aortic branches and distal tissues. Traditionally, aortic diameter has been used to evaluate postoperative remodeling, but assessing aortic volume theoretically provides a more accurate representation of aortic remodeling. 23

A modified PETTICOAT study reported 17 that true lumen volume increased by 167.74% and 154.17% in the thoracic and abdominal aorta, respectively, while false lumen volume decreased by 75% and 39.24%. Another study using the E-PETTICOAT technique for chronic type B aortic dissection reported 24 a 96.60% reduction in false lumen volume, with 1 patient (5%) requiring visceral branch stenting. Yet another study involving 16 patients with acute or subacute type B dissection reported 18 complete false lumen thrombosis in all patients within the stented segment, with nine patients (56%) requiring visceral branch stenting. A study on the STABILISE technique 19 included 41 patients with acute type B aortic dissection, of whom 13 (32%) underwent implantation of visceral artery branch stents. At one year postoperatively, all patients demonstrated complete false lumen thrombosis within the stent-covered region, and 16 (39%) achieved complete false lumen thrombosis in the infrarenal aorta. Another report 20 on dense mesh stent technology included 23 patients with complicated type B dissections. One year postoperatively, true lumen volume increased by 75.9%, while false lumen volume decreased by 42.8%. A separate study on dense mesh stent technology 25 included 56 patients with RAD. At one year, the true lumen volume increased by 22.55 cm3, and the false lumen volume decreased by 21.94 cm3. In this study, aortic CTA at 30 days postoperatively indicated an average true lumen volume increase of 141.26% (73.04 cm3) and an average false lumen volume reduction of 79.32% (49.6 cm3).

According to existing studies, the degree of aortic remodeling is closely related to the coverage range of the stent graft. The classic PETTICOAT and STABILISE techniques are limited in achieving complete thrombosis of the false lumen due to the absence of stent coverage in the infrarenal abdominal aorta. While the E-PETTICOAT technique achieves a relatively high rate of false lumen thrombosis, the associated bare metal stent has limitations, such as a high porosity, insufficient radial support, and inability to seal distal tears completely. As a result, additional interventions like branch bridging stents are often required to enhance the repair, which increases procedural time and poses a risk of long-term stent occlusion. 26 Dense mesh stents, with their optimized porosity, offer stronger radial support. Their post-deployment pore diameter, averaging 1–2 mm, can seal most distal tears with a mean long-axis diameter of ∼5 mm. Previous clinical trials of dense mesh stents largely adopted traditional deployment techniques and principles of covered stents. However, the deployment of dense mesh stents involves not only circumferential changes but also length alterations, and these two changes are positively correlated. Achieving the ideal post-deployment diameter—generally matching the aortic diameter at the corresponding level—is crucial to fully utilize the dense mesh stent's robust radial support. Based on the correlation between post-deployment length and diameter of dense mesh stents, this study developed precision positioning, segmental compression-release, and balloon-assisted expansion techniques. The first ensures that the overlapping regions of the stent do not involve visceral arterial branches, thereby preserving their perfusion. The latter two techniques maximize the stent's radial support, promoting reattachment of most of the aortic intima to the adventitia, thereby eliminating the false lumen and sealing distal tears. It is worth noting that some clinical studies 25 on dense mesh stents suggest that balloon post-dilation is unnecessary due to the shape-memory properties of the titanium alloy used in the stent. However, postoperative angiography often reveals suboptimal stent morphology in most patients, particularly in cases of chronic true lumen narrowing or at the proximal and distal stent ends. Adequate balloon dilation pressure is therefore required to assist shaping and enhance remodeling effects. The findings of this study corroborate this, showing that the combined use of post-dilation techniques resulted in greater true lumen expansion and false lumen thrombosis. Additionally, this study designed a precise false lumen sealing technique for addressing residual micro-distal tears following dense mesh stent implantation. With the false lumen significantly compressed after stent deployment, conditions are favorable for the attachment and fixation of embolization materials. Furthermore, the small size and reduced flow of residual tears simplify the sealing process, ensuring thorough results. At 30 days postoperatively, some patients in this study had not achieved complete false lumen thrombosis. As patients are required to take antiplatelet medications for the first six months postoperatively, it is theoretically expected that aortic remodeling will gradually improve over time.

Visceral artery branches

According to the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD), 27 renal malperfusion occurs in 18% of AAD patients, gastrointestinal malperfusion in 3.7% (type A) and 7% (type B), and limb malperfusion in 9.7%. Malperfusion syndromes are known independent risk factors for poor outcomes in AAD patients. In this study, one patient had gastrointestinal malperfusion and one patient had limb malperfusion preoperatively. By 30 days postoperatively, these symptoms had resolved, and all high-risk ischemic visceral branches had reverted to non-high-risk status. Intraoperative angiography and postoperative aortic CTA indicated that the uniform radial support provided by the dense mesh stent facilitates in-situ reattachment of the aortic intima to the adventitia. This not only avoids the need for visceral artery reconstruction but also alleviates dynamic ischemia and most cases of static ischemia in visceral artery branches.

Limitations

For the following reasons, the inclusion criteria of this study were relatively broad.

Due to the lower rate of hypertension control, the average onset age of aortic dissection patients in China is ∼ 10 years younger than in developed countries. 28 Patients who survive the initial repair have a longer expected lifespan, making long-term prognosis a critical concern. When RAD progresses to late-stage aneurysmal dilation or organ malperfusion, more complex surgical or endovascular repair techniques are required. However, the uneven distribution of medical resources in China means that many patients in the advanced stages of disease may not have access to optimal treatment. This leaves them in a prolonged state of anxiety and fear, significantly affecting their quality of life. As a result, many patients prefer a more proactive approach to managing their residual disease.

Although RAD may not cause significant symptoms in the short term, for newly diagnosed AAD patients, achieving a one-stage repair of the entire aorta would undoubtedly be a better option. However, due to the complexity of acute-phase disease, conducting clinical trials in these patients poses both ethical concerns and challenges in maintaining study quality. In contrast, chronic RAD patients are in a relatively stable condition. Conducting trials to repair residual disease under voluntary patient participation is safer and can provide valuable data to guide future applications of the device in acute-phase patients.

In patients without aneurysmal degeneration, the aortic morphology remains relatively normal, providing optimal conditions for endovascular repair. This allows for a better therapeutic effect while minimizing the number of implanted devices.

For these reasons, we have chosen to perform early intervention in patients with RAD involving the visceral artery branches, under conditions of patient willingness and proactive participation. If the safety and efficacy of the stent are confirmed, we plan to extend its use to the initial repair of AAD. This would involve combining it with appropriate open surgical or endovascular techniques to explore the feasibility of one-stage repair of the entire aortic pathology.

Further studies are required to identify risk factors associated with poor outcomes in RAD patients, as well as to define the most appropriate patient populations for these techniques.

Given the study's nature as a clinical trial for a novel medical device, it was designed as a single-arm study with a relatively small sample size and short follow-up period, due to ethical considerations. Long-term safety and efficacy of these techniques will require larger studies and extended follow-up, and we plan to continue reporting the long-term outcomes of enrolled patients.

We observed that some chronic patients had suboptimal aortic remodeling, which requires further study. Future work should focus on improving predictive models for surgical outcomes and optimizing product designs and techniques to enhance aortic remodeling.

Conclusion

Preliminary results indicate that the combined use of four stent release and post-processing techniques—precise stent positioning, segmental compression release, balloon-assisted expansion, and accurate closure of the false lumen tear—can effectively expand the true lumen and reduce or eliminate the false lumen while preserving branch blood flow with relatively low technical complexity. Long-term results require further follow-up. For acute and chronic patients with visceral artery branch involvement requiring intervention, this technique may offer a viable alternative treatment.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-sci-10.1177_00368504251340800 for Preliminary results of one-stage repair of residual aortic dissection using dense mesh stent combined with release and post-processing techniques by Shouming Li, Huanyu Qiao, Chen Zhang, Tao Bai, Bo Yang, Honglei Zhao, Kefeng Zhang, Zhang Cheng, Hongbo Zhang, Xiaohai Ma and Yongmin Liu in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-sci-10.1177_00368504251340800 for Preliminary results of one-stage repair of residual aortic dissection using dense mesh stent combined with release and post-processing techniques by Shouming Li, Huanyu Qiao, Chen Zhang, Tao Bai, Bo Yang, Honglei Zhao, Kefeng Zhang, Zhang Cheng, Hongbo Zhang, Xiaohai Ma and Yongmin Liu in Science Progress

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the medical staff at Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, for their support in patient management and data collection. We also appreciate the contributions of our colleagues and researchers who provided valuable insights during the study. We utilized AI-assisted tools for language polishing in this study.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Shouming Li https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4930-551X

Zhang Cheng https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3647-7241

Ethical considerations: This study received ethical approval from the Beijing Anzhen Hospital IRB [(2023) No. (2)] on 30 December 2022.

Authors’ contributions: Yongmin Liu and Xiaohai Ma were responsible for study design and article review. Shouming Li conducted the study, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the article. Huanyu Qiao, Chen Zhang, Tao Bai, Bo Yang, Honglei Zhao, Kefeng Zhang, Zhang Cheng, and Hongbo Zhang were responsible for study implementation.

Informed consent: The authors confirm that patient data used in this study were collected with written informed consent and in compliance with applicable regulations. Patients provided consent for the publication of anonymized data, and all efforts were made to ensure patient privacy and confidentiality.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission, Administrative Commission of Zhongguancun Science Park (grant number Z191100006619094).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Yamaguchi T, Nakai M, Yano T, et al. Population-based incidence and outcomes of acute aortic dissection in Japan. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2021; 10: 701–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohl LP, Isselbacher EM, Majahalme N, et al. Comparison of outcomes in DeBakey type AI versus AII aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol 2018; 122: 689–695. 20180630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie E, Yang F, Liu Y, et al. Timing and outcome of endovascular repair for uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg: Official J Eur Soc Vasc Surg 2021; 61: 788–797. 20210410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Y, Lingala B, Baiocchi M, et al. Type A aortic dissection-experience over 5 decades: JACC historical breakthroughs in perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76: 1703–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roselli EE, Loor G, He J, et al. Distal aortic interventions after repair of ascending dissection: the argument for a more aggressive approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 149: S117–124. e113. 20141120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Ma W, Chen J, et al. Distal remodeling after operations for extensive acute aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2021; 112: 83–90. 20201021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan Z, Li Y, Jin B, et al. Remodeling of aortic configuration and abdominal aortic branch perfusion after endovascular repair of acute type B aortic dissection: a computed tomographic angiography follow-up. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021; 8: 752849. 20211025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertoglio L, Rinaldi E, Melissano G, et al. The PETTICOAT concept for endovascular treatment of type B aortic dissection. J Cardiovasc Surg 2019; 60: 91–99. 20170209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eleshra A, Rohlffs F, Spanos K, et al. Aortic remodeling after custom-made candy-plug for distal false lumen occlusion in aortic dissection. J Endovasc Ther: Official J Int Soc Endovasc Special 2021; 28: 399–406. 20210226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahlberg A, Mascia D, Bertoglio L, et al. New technical approach for type B dissection: from the PETTICOAT to the STABILISE concept. J Cardiovasc Surg 2019; 60: 281–288. 20190220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams ML, de Boer M, Hwang B, et al. Thoracic endovascular repair of chronic type B aortic dissection: a systematic review. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2022; 11: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sultan S, Hynes N, Sultan M. When not to implant the multilayer flow modulator: lessons learned from application outside the indications for use in patients with thoracoabdominal pathologies. J Endovasc Ther: Official J Int Soc Endovasc Special 2014; 21: 96–112. 2014/02/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152: 726–732. 20100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lombardi JV, Hughes GC, Appoo JJ, et al. Society for vascular surgery (SVS) and society of thoracic surgeons (STS) reporting standards for type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg 2020; 71: 723–747. 20200127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagamine H, Ueno Y, Ueda H, et al. A new classification system for branch artery perfusion patterns in acute aortic dissection for examining the effects of central aortic repair. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg: Official J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thoracic Surg 2013; 44: 146–153. 20121213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Li Z, Feng J, et al. Total endovascular repair with parallel stent-grafts for postdissection thoracoabdominal aneurysm after prior proximal repair. J Endovasc Ther: Official J Int Soc Endovasc Special 2019; 26: 668–675. 20190731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He H, Yao K, Nie WP, et al. Modified petticoat technique with Pre-placement of a distal bare stent improves early aortic remodeling after complicated acute Stanford type B aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg: Official J Eur Soc Vasc Surg 2015; 50: 450–459. 2015/06/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leo E, Molinari ACL, Ferraresi M, et al. Short term outcomes of distal extended endovascular aortic repair (DEEVAR) petticoat in acute and subacute complicated type B aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg: Official J Eur Soc Vasc Surg 2021; 62: 569–574. 20210721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faure EM, El Batti S, Abou Rjeili M, et al. Mid-term outcomes of stent assisted balloon induced intimal disruption and relamination in aortic dissection repair (STABILISE) in acute type B aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg: Official J Eur Soc Vasc Surg 2018; 56: 209–215. 20180608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costache VS, Meekel JP, Costache A, et al. One-year single-center results of the multilayer flow modulator stents for the treatment of type B aortic dissection. J Endovasc Ther: Official J Int Soc Endovasc Special 2021; 28: 20–31. 20200901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu C, Wang H, Yang P, et al. Early results of the newly-designed flowdynamics dense mesh stent for residual dissection after proximal repair of Stanford type A or type B aortic dissection: a preliminary single-center report from a multicenter, prospective, and randomized study. Journal of Endovascular Therapy 2023; 31: 984–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porto A, Omnes V, Bartoli MA, et al. Reintervention of residual aortic dissection after type A aortic repair: results of a prospective follow-up at 5 years. J Clin Med 2023; 12: 20230318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regeer MV, Martina B, Versteegh MI, et al. Prognostic implications of descending thoracic aorta dilation after surgery for aortic dissection. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017; 11: 1–7. 20161025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazimierczak A, Rynio P, Jędrzejczak T, et al. Expanded petticoat technique to promote the reduction of contrasted false lumen volume in patients with chronic type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2019; 70: 1782–1791. 20190911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu C, Duan W, Li Z, et al. One-year results of the flowdynamics dense mesh stent for residual dissection after proximal repair of Stanford type A or type B aortic dissection: a multicenter, prospective, and randomized study. Int J Surg 2024; 110: 4151–4160. 20240701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molski M, Jankowska M, Mross K, et al. The extended PETTICOAT technique does not guarantee favorable remodeling after acute type B aortic dissection. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej 2022; 18: 283–289. 20221102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Bossone E, et al. Insights from the international registry of acute aortic dissection: a 20-year experience of collaborative clinical research. Circulation 2018; 137: 1846–1860. 2018/04/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Duan W, Xue Y, et al. Clinical features of acute aortic dissection from the registry of aortic dissection in China. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 148: 2995–3000. 20140804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-sci-10.1177_00368504251340800 for Preliminary results of one-stage repair of residual aortic dissection using dense mesh stent combined with release and post-processing techniques by Shouming Li, Huanyu Qiao, Chen Zhang, Tao Bai, Bo Yang, Honglei Zhao, Kefeng Zhang, Zhang Cheng, Hongbo Zhang, Xiaohai Ma and Yongmin Liu in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-sci-10.1177_00368504251340800 for Preliminary results of one-stage repair of residual aortic dissection using dense mesh stent combined with release and post-processing techniques by Shouming Li, Huanyu Qiao, Chen Zhang, Tao Bai, Bo Yang, Honglei Zhao, Kefeng Zhang, Zhang Cheng, Hongbo Zhang, Xiaohai Ma and Yongmin Liu in Science Progress