Abstract

Shewanella spp. played pivotal ecological roles and were reported to be the progenitor of blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase genes. However, it remained unknown which species was the progenitor of different OXA-48 carbapenemase variants. To address this issue, we analysed the largest collection of Shewanella genomes to our knowledge and performed genetic and phenotypic analysis on Shewanella collected from Zhejiang province, China. Our results suggested that blaOXA-48-like was intrinsically carried by a few Shewanella species and different blaOXA-48-like variants were associated with different Shewanella species; for instance, Shewanella baltica was associated with blaOXA-924, and some Shewanella oncorhynchi and Shewanella putrefaciens carried blaOXA-900-like. The blaOXA-48-like genes carried by Shewanella xiamenensis were highly diverse. Comparatively, none of the Shewanella algae genomes carried blaOXA-48-like. Results of phylogenetic analysis supported the notion that OXA-48-like carbapenemase originated from different environmental Shewanella species and was captured by clinical species, particularly Enterobacterales. Different Shewanella species distributed in different niches in Zhejiang province, i.e. S. algae (n=12) and Shewanella indica (n=1) strains were all isolated from clinical settings and S. xiamenensis (n=23) and Shewanella mangrovisoli (n=2) were isolated from both hospital sewage and river water. blaOXA-48-like genes in Shewanella spp. from Zhejiang province were located on the chromosome. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the progenitor of different blaOXA-48-like variants with a focus on the Shewanella population. Results in this study highlighted the important role of Shewanella species in the ecosystem, particularly as the major source of the notorious carbapenemase gene, blaOXA-48. Control measures should be implemented to prevent further dissemination of such organisms in the hospital setting and the community.

Keywords: genomic characterization, OXA-48-like, progenitor, Shewanella spp., transmission

Impact Statement.

Shewanella sp. is an important environmental species playing pivotal ecological roles, with several members being pathogenic to human beings. Through genomic analysis of all available Shewanella genomes and epidemiological study of Shewanella strains from Zhejiang province, China, a few important conclusions were achieved, including the following: (1) blaOXA-48-like gene was intrinsically carried by some Shewanella species; (2) blaOXA-48-like originated from environmental Shewanella and was captured by Enterobacterales; (3) the distribution of Shewanella was niche specific in Zhejiang province, either environmentally or clinically; and (4) blaOXA-48-like in Shewanella was chromosome-borne. Results in this study highlighted the important role of Shewanella species in the ecosystem, particularly as the major source of the notorious carbapenemase gene, blaOXA-48.

Data Summary

The whole-genome sequencing data of all strains in this study have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1064064.

Introduction

Shewanella is a unique member of the Shewanellaceae family, which includes facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative rods [1]. As of March 2024, a total of 130 species have been identified in this genus (https://lpsn.dsmz.de/search?word=Shewanella). Shewanella is commonly considered an environmental genus widely distributed in nature, particularly in aquatic environments including seawater, freshwater and in marine organisms [2]. Some members of this genus, such as Shewanella oneidensis, have been identified that could potentially play beneficial roles in ecological processes such as serving as microbial fuel cells and bioremediation of toxic agents [3]. In addition, some species like Shewanella putrefaciens, Shewanella algae, Shewanella haliotis and Shewanella xiamenensis have been documented with pathogenicity in human beings [4]. Reported illnesses related to Shewanella include bacteremia, pneumonia, endocarditis, otitis media and soft tissue, skin, intracerebral, ocular and gastrointestinal infections, some of which could lead to serious clinical or even fatal consequences [5,7].

Antibiotic resistance is reported to be a natural phenomenon that predates the modern selective pressure of clinical antibiotic use [8]. The origin of many modern resistance genes in pathogens is likely environmental bacteria [9]; for instance, Acinetobacter radioresistens was the progenitor of the blaOXA-23 CHDL gene widespread in A. baumannii [10], Flavobacteriaceae was the potential ancestral source of tetracycline resistance gene tet(X) [11] and the RND efflux gene cluster tmexCD-toprJ conferring multidrug resistance originated from the chromosome of Pseudomonas [12]. Likewise, bacteria of the environmental genus, Shewanella, are a reservoir of antibiotic resistance determinants. Particularly, Shewanella was the progenitor of the Qnr-type quinolone resistance genes and the blaOXA-48-like oxacillinase class D β-lactamase-encoding genes conferring carbapenem resistance [2].

OXA-48-like carbapenemases are the most common carbapenemases in the clinically important pathogens, Enterobacterales, in certain regions of the world (e.g. the Middle East, North Africa and some European countries) [13]. The OXA-48-like carbapenemases are highly diverse, among which OXA-48, OXA-181, OXA-232, OXA-204, OXA-162 and OXA-244 are the most commonly reported [13]. Shewanella spp. were considered important reservoirs and progenitors of carbapenem-hydrolysing OXA enzymes, including OXA-48-like carbapenemase, which was the most common carbapenemase in Enterobacterales in certain regions of the world [13]. The first chromosome-encoded OXA carbapenemase in Shewanella spp., OXA-54, whose potential source could be S. oneidensis, was reported around the same time as OXA-48 [14]. Different Shewanella species could carry different blaOXA-48-like variants, for example, several variants including blaOXA-48, blaOXA-199, blaOXA-204 and blaOXA-181 were identified in S. xiamenensis, and blaOXA-54 was identified in S. oneidensis [14,18]. Mobile genetic elements, such as the composite transposon, Tn1999, were associated with the mobilization of OXA-48-like β-lactamase from the chromosome of Shewanella spp. to other bacteria, including Enterobacterales, posing a serious threat to human health [19]. Nevertheless, the genetic characteristics of the Shewanella population, the distribution and the transmission potential of blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase genes in Shewanella remained poorly understood. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive genomic characterization with genome sequences from both the National Center for BiotechnologyInformation (NCBI) database and our collection to fill this knowledge gap.

Methods

Genomic sequence retrieval, species identification and genetic characterization

All Shewanella spp. genomes publicly available in the NCBI Genome database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/genomes/) as of 1 September 2023 were downloaded. FastANI was used to calculate the whole-genome average nucleotide identity (ANI) between the downloaded genomes and the reference sequences of the 130 Shewanella species available in the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature database [20]. Species were identified based on the ANI values. The presence of blaOXA-48-like genes and other acquired antimicrobial resistance genes was identified using ResFinder 4.1 [21].

Phylogenetic analysis of Shewanella spp. from the database

All Shewanella spp. genomes from the NCBI database were screened for the presence of 40 conserved single-copy genes using FetchMG v1.0 [22]. These markers were translated into protein sequences, concatenated and aligned using muscle v5.1. The aligned amino acid sequence was trimmed using trimal v1.2rev59 [23]. FastTree v2.1.11 was used to construct an approximately maximum likelihood tree with default parameters [24]. The generated phylogenetic tree was visualized and edited with iTOL version 6 [25].

Sequence acquisition and alignment of the OXA-48-like protein

The amino acid sequence of all OXA-48-like carbapenemases available as of 1 December 2023 was downloaded from both the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (https://card.mcmaster.ca/) and the Pathogen Detection Reference Gene Catalog database. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using muscle v3.8.31 with default parameters [26]. A model with the least score (JTT+G) evaluated using the Models function in mega 7 was selected as the best amino acid substitution model to reconstruct the maximum likelihood tree [27]. Gaps and missing data were treated as partial deletions. Results were validated using 1,000 bootstrap replicates [27].

Strain collection and species identification

Shewanella strains were collected during the period 2022–2023 as part of an ongoing surveillance programme aimed at identifying Gram-negative organisms in Zhejiang province, China. Samples were collected from different sources in Zhejiang, including clinical settings, rivers and hospital sewages. Clinical samples, including pustule, sputum and blood, were collected from patients hospitalized in The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Jiefang Road). The hospital is one of the major medical centres in Zhejiang province and a large comprehensive tertiary hospital. In 2022, the annual outpatient volume of the hospital exceeded 5 million visits, reflecting its role as a leading medical centre in the region. Hospital sewage samples were collected from six hospitals in Zhejiang. River water samples were collected from four rivers in Zhejiang province. The geographic distributions of the sampling sites were listed in Table S4 (available in online Supplementary Material). Strains were isolated on LB agar plates containing 0.3 µg ml−1 meropenem. All strains were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). Subsequently, strains identified as belonging to Shewanella spp. were subjected to WGS to determine the exact species and facilitate further research.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of all Shewanella strains against 15 commonly used antibiotics (imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, cefmetazole, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefoperazone/sulbactam, ceftazidime/avibactam, cefepime, polymyxin B, tigecycline, ciprofloxacin, amikacin and aztreonam) were determined by the VITEK 2 COMPACT automatic microbiology analyser and interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines, except tigecycline and colistin [28], the breakpoints of which were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [29].

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight cultures by using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All Shewanella strains were subjected to whole-genome sequencing using the HiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Genome assembly was conducted with SPAdes v3.15.5 [30]. Oxford nanopore MinION sequencing was conducted to obtain the complete genome sequences of selected strains carrying different OXA-48-like variants, using the SQK-NBD114.24 sequencing kit and flowcell R10.4.1. The raw sequencing data were basecalled using Guppy 3.0.3 with default parameters [31]. A hybrid assembly of Illumina and nanopore sequencing reads was constructed using Unicycler v 0.5.0 [32]. Genome sequences were annotated using RAST v2.0 with manual editing [33]. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes were identified by ResFinder 4.1 [34]. A heatmap of antimicrobial resistance genes was plotted using TBtools [35]. Insertion sequences (ISs) were identified using ISfinder v2.0 [36]. The genetic location (chromosome or plasmid) of the blaOXA-48-like gene was determined by aligning the contigs carrying blaOXA-48-like with complete genome sequences in the NCBI database and those generated in this study. The harvest suite was used to build a phylogenetic tree in this study with default parameters [37]. The core genomes of the strains were aligned, and phylogenetic trees were constructed using Parsnp v1.2, while SNPs in core genes among different strains were calculated using Gingr and snp-dists software. Briefly, Parsnp, which combines the advantages of both whole-genome alignment and read mapping, was used to produce a core-genome alignment, variant calls and a SNP tree. The tree construction function embedded in Parsnp was accomplished with FastTree2. The tree was visualized and edited with iTOL version 6 [25].

Results

In silico analysis of the genomic landscape of the Shewanella population

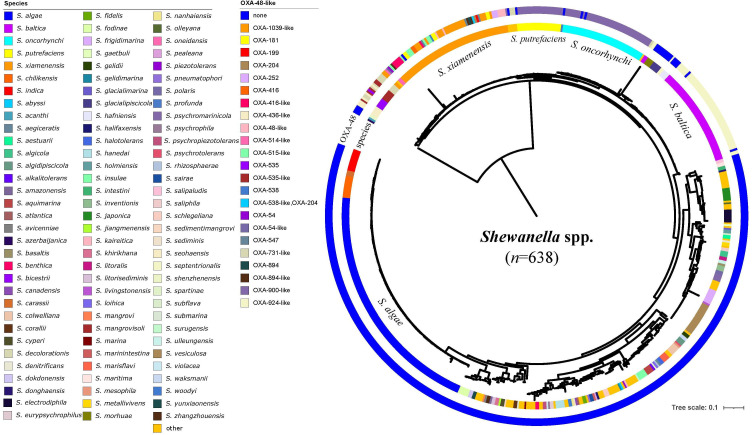

In silico analyses were performed with a total of 638 non-duplicated Shewanella genomes retrieved from the NCBI database (query performed on 1 September 2023). The source for most of the 638 strains was unavailable and was thus not analysed. ANI analysis suggested that 72 out of the 638 genomes shared <95% ANI with that of their closest reference Shewanella species (ANI ranging from 77.56 to 94.82%), indicating they could belong to novel species not reported previously. The remaining 566 genomes covered 99 Shewanella species, among which 40 species were represented by only one genome. S. algae (n=130, 23.0%), S. xiamenensis (n=64, 11.3%), Shewanella oncorhynchi (n=46, 8.1%), S. putrefaciens (n=24, 4.2%) and Shewanella vesiculosa (n=18, 3.2%) accounted for the dominant species (Fig. 1, Table S1).

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic tree of Shewanella spp. A total of 638 non-duplicated genome sequences were retrieved from the NCBI genome database and were used to build the phylogenetic tree. This tree was mid-rooted and visualized using iTOL. The circles from the innermost to outermost indicated the species and the production of OXA-48-like carbapenemase by each strain. The 72 strains that shared <95% identity with the reference genomes were labelled with ‘other’ to indicate that their species were not resolved.

Among the 638 Shewanella genomes, a total of 216 (33.9%) carried blaOXA-48-like genes, including 18 different variants which were blaOXA-900-like (n=68), blaOXA-924-like (n=55), blaOXA-1039-like (n=24), blaOXA-731-like (n=12), blaOXA-515-like (n=8), blaOXA-416-like (n=8), blaOXA-535-like (n=6), blaOXA-48-like (n=6), blaOXA-436-like (n=6), blaOXA-181 (n=6), blaOXA-54-like (n=5), blaOXA-894-like (n=4), blaOXA-252 (n=3), blaOXA-547 (n=3), blaOXA-538-like (n=2), blaOXA-204 (n=2), blaOXA-514-like (n=1) and blaOXA-199 (n=1). Strains carrying blaOXA-48-like were genetically closely related compared with those without blaOXA-48-like genes (Fig. 1). The 216 genomes belonged to 11 different species, including S. xiamenensis (n=66), Shewanella baltica (n=55), S. oncorhynchi (n=46), S. putrefaciens (n=23), Shewanella mangrovisoli (n=6), Shewanella seohaensis (n=5), Shewanella bicestrii (n=5), Shewanella decolorationis (n=4), S. oneidensis (n=3), Shewanella hafniensis (n=2) and Shewanella septentrionalis (n=1). Among these, one S. xiamenensis carried two blaOXA-48-like genes, blaOXA-538-like and blaOXA-204.

Different variants of the blaOXA-48-like genes were associated with different Shewanella species, for instance, blaOXA-924-like genes were detected predominantly in S. baltica (54/55, 98.2%), and blaOXA-900-like genes were mostly detected in S. oncorhynchi (44/68, 64.7%) and S. putrefaciens (23/68, 33.8%). All except one S. xiamenensis, with a total number of 66, carried the blaOXA-48-like genes. The blaOXA-48-like genes carried by S. xiamenensis were highly diverse, including blaOXA-1039-like (n=24), blaOXA-416-like (n=8), blaOXA-515-like (n=8), blaOXA-181 (n=6), blaOXA-48-like (n=6), blaOXA-894-like (n=4), blaOXA-252 (n=3), blaOXA-547 (n=3), blaOXA-538-like (n=2), blaOXA-204 (n=2) and blaOXA-199 (n=1). Comparatively, none of the S. algae genomes carried blaOXA-48-like genes (Fig. 1, Table S1).

Other antimicrobial resistance genes carried by the 638 Shewanella genomes are shown in Table S6. A total of 24 strains (3.8%) carried blaNDM-1, which belonged to S. xiamenensis (n=10), S. putrefaciens (n=9), S. bicestrii (n=3) and S. mangrovisoli (n=2). Three S. xiamenensis carried tet(X4), among which two co-carried the RND efflux gene cluster tmexCD3-toprJ3. Besides, one S. bicestrii carried blaVIM-2. These findings suggested Shewanella could be an important vector of last-line antibiotic resistance genes. Other dominant resistance genes carried by these Shewanella strains were blaOXA-SHE (n=134, 21.0%), qnrA3 (n=53, 8.3%) and qnrA7 (n=44, 6.9%), respectively.

Origin, diversity and evolutionary trend of OXA-48-like carbapenemase

The G+C content of Shewanella spp. ranged from 40.23 to 55.69% (Table S2), with the median being 45.3% (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/13542). That of the blaOXA-48-like genes ranged from 44.11 to 47.37 %, with a median of 44.61% (Table S3). These data suggested the G+C content of blaOXA-48-like genes was similar to that of a few but not all Shewanella species, suggesting only a few Shewanella species could be the ancestral source of the blaOXA-48-like genes. This was in line with the finding that only 33.9% of Shewanella genomes carried blaOXA-48-like genes. According to the observation on the blaOXA-48 variants carried by different Shewanella, we speculated that S. baltica (G+C content: 46.31 mol%) could be the progenitor of blaOXA-924-like genes (45.36 mol%); blaOXA-900-like genes (44.53 mol%) could be originated from S. oncorhynchi (45.26 mol%) and/or S. putrefaciens (44.61 mol%); and S. xiamenensis (46.27 mol%) could be the ancestral source of several blaOXA-48 variants such as blaOXA-1039-like (44.49 mol%), blaOXA-416-like (44.61 mol%), blaOXA-515-like (44.74 mol%), blaOXA-181 (45.36 mol%) and blaOXA-48-like (44.49 mol%).

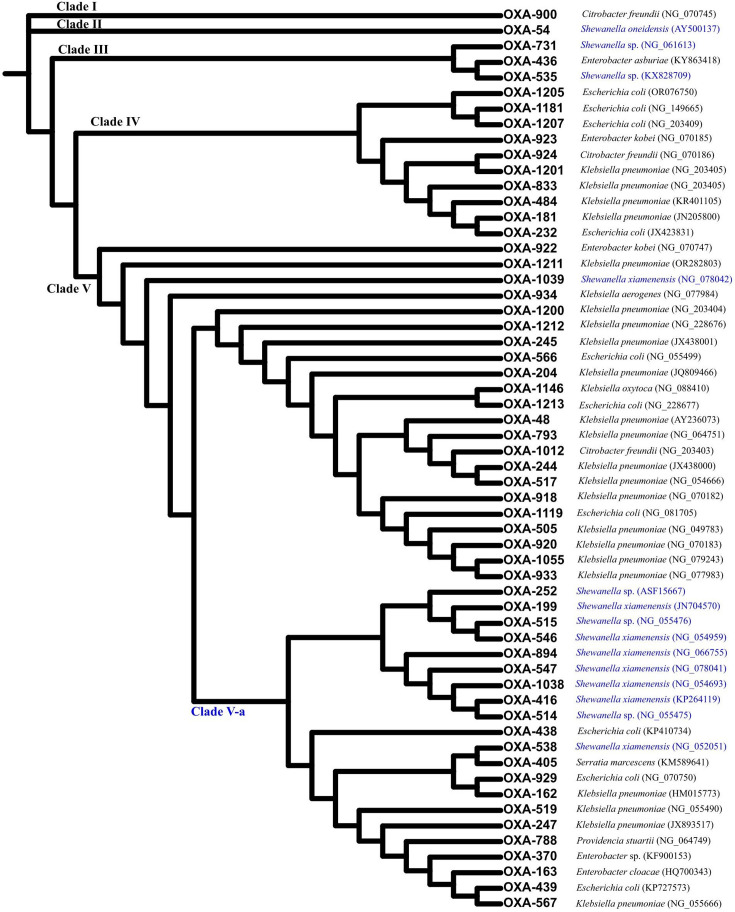

To test our hypothesis and determine the phylogenetic profile of OXA-48-like carbapenemase, multiple sequence alignment was performed on the amino acid sequences of a total of 58 OXA-48-like variants publicly available as of 1 December 2023. These variants shared 81.1–99.6% identity with OXA-48 sensu stricto. The reconstruction of an approximately maximum likelihood tree allowed us to identify five distinctive clades, the first two of which comprised only one variant, OXA-900 (Clade I) and OXA-54 (Clade II), which shared 81.1% and 92.5% identity with OXA-48, respectively (Fig. 2). Interestingly, OXA-900, proposed to be originated from Shewanella sp., was firstly reported from Citrobacter freundii, in which it was located on an antibiotic resistance island with mobile genetic elements on an IncC plasmid [38]. Clade V, which included OXA-48 sensu stricto, contained the highest number of OXA-48 variants (n=43). A subclade in Clade V, Clade V-a, comprised 21 OXA-48 variants reported from both Shewanella sp. and Enterobacterales, suggesting the close genetic relationship of such variants in these distantly related species. The remaining variants in Clade V were all reported from Enterobacterales except for OXA-1039, which was reported from S. xiamenensis, suggesting the further evolution of OXA-48-like carbapenemase after acquisition by Enterobacterales. Likewise, OXA-48 variants in Clade III (n=3) were from both Shewanella sp. and Enterobacterales, indicating the genus ancestor of blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase genes and its dissemination in Enterobacterales. Unlike these clades, OXA-48 variants in Clade IV (n=10) were all reported from Enterobacterales, including OXA-181 and OXA-232, the second and third most common global OXA-48-like derivatives [13] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic tree of all OXA-48-like carbapenemases. Cladogram of the tree of blaOXA-48-like genes with clades annotated on the branches. A total of 58 OXA-48-like carbapenemases publicly available as of 1 December 2023 are included. The annotation alongside different variants indicates the species from which the corresponding OXA-48-like carbapenemase was reported and the accession number of the associated nucleotide acid sequence. The variants reported from Shewanella spp. are annotated with blue fonts. The amino acid sequence alignment of the 58 OXA-48-like carbapenemases is shown in Figure S1.

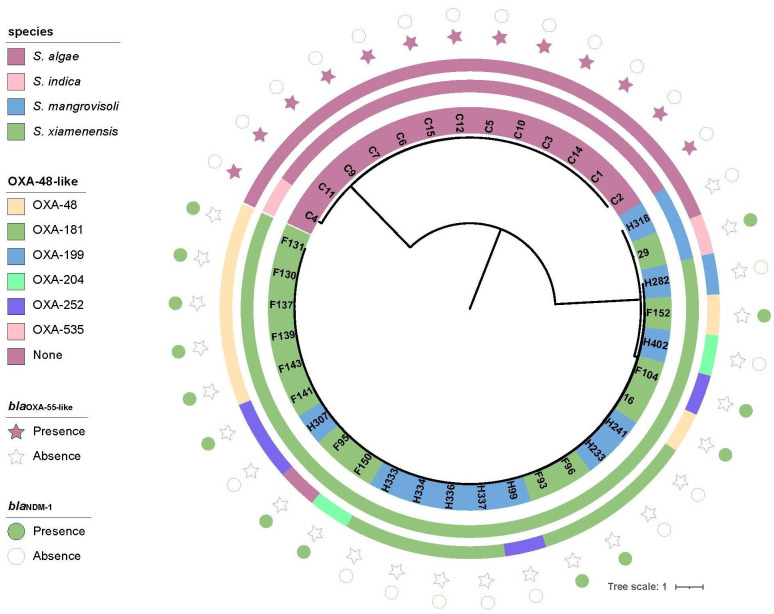

Species and carriage of carbapenemase genes of Shewanella spp. from different sources in Zhejiang province

A total of 38 Shewanella spp. were collected from different sources in Zhejiang province, including clinical settings (n=13), hospital sewage (n=14) and river water (n=11). Strains from the three sources were denoted with unique identifiers (IDs) beginning with C, F, and H, respectively. The 38 strains belonged to four different species, including S. xiamenensis (n=23), S. algae (n=12), S. mangrovisoli (n=2) and Shewanella indica (n=1). Interestingly, the S. algae and S. indica strains were all isolated from clinical settings. S. xiamenensis strains were isolated from both hospital sewage (n=13) and river water (n=10). Likewise, S. mangrovisoli was also isolated from both hospital sewage (n=1) and river water (n=1).

According to previous studies, the blaOXA-55 gene was intrinsic to S. algae [39]. Likewise, all the 13 clinical isolates carried the blaOXA-55-like carbapenemase genes. Yet, none of the clinical isolates carried the blaOXA-48-like gene. S. mangrovisoli strain H318 from river water did not carry any carbapenemase gene, and S. mangrovisoli strain 29 from hospital sewage carried both blaOXA-535-like and blaNDM-1 genes. All the S. xiamenensis from hospital sewage carried blaNDM-1, and none of the strains from river freshwater encoded the NDM carbapenemase. Like that of strains in the NCBI database, S. xiamenensis in our collection carried a wide diversity of blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase genes. The dominant blaOXA-48-like gene carried by the river water S. xiamenensis isolates was blaOXA-181 (n=6), followed by blaOXA-252-like (n=2), blaOXA-199-like (n=1) and blaOXA-204-like (n=1). The dominant blaOXA-48-like gene carried by the S. xiamenensis isolates from hospital sewage was blaOXA-48-like (n=7), followed by blaOXA-181 (n=2), blaOXA-252-like (n=2) and blaOXA-204-like (n=1). One S. xiamenensis from hospital sewage did not carry the blaOXA-48-like gene. (Fig. 3, Table S4).

Fig. 3. Phylogenetic tree of Shewanella spp. in this study. The background colour of the strains indicates the source of the corresponding strains which are from a clinical setting (pink), hospital sewage (green) and river (blue), respectively (strains from the three sources are denoted with IDs beginning with C, F and H, respectively). The innermost to outermost circles in this tree indicate the species, the production of OXA-48-like carbapenemase and the presence of the carbapenemase genes blaOXA-55-like and blaNDM-1, respectively.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Shewanella spp. in Zhejiang province

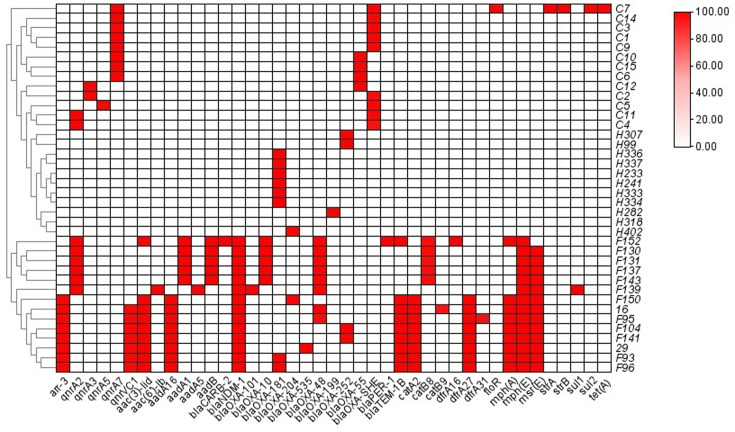

A heatmap was plotted to depict the patterns of antimicrobial resistance genes carried by Shewanella strains in this study (Fig. 4). Our results suggested that the resistance genes carried by Shewanella exhibited a source-associated pattern. Strains from clinical settings and river waters carried fewer resistance genes compared with those from hospital sewage. Specifically, strains from the river carried no resistance genes apart from blaOXA-48-like. Apart from one strain, S. algae C7, carrying a cassette of resistance genes including qnrA7, floR, strAB, sul2, tet(A) and blaOXA-55-like, all other Shewanella strains from clinical settings carried only two resistance genes, i.e. a quinolone resistance gene qnr and a blaOXA-55-like gene. Additionally, SNP analysis revealed that the 13 S. algae strains had an average SNP count of 78,610.9 and a median of 55,888, indicating that they do not belong to the same clone. The number of resistance genes carried by isolates from hospital wastewater ranged from 9 to 14, conferring resistance to different classes of antibiotics including aminoglycosides, quinolones, macrolides, phenicols, rifampin, sulphonamides, trimethoprim and β-lactamases (Fig. 4, Table S4). In line with the resistance gene profiles carried by each strain, the blaOXA-48-negative strains were susceptible to commonly used antibiotics, and blaOXA-48-positive strains were resistant to antibiotics such as carbapenemase (Tables 1 and S5).

Fig. 4. Heatmap of antimicrobial resistance genes carried by the Shewanella spp. in this study. Horizontal axes represent the antimicrobial resistance genes, and vertical axes represent the strain IDs. Red and white boxes represent the presence and absence of the corresponding items among sequenced isolates, respectively. The gradient identity bar indicates the percentage similarity of related genes. The similarity tree was calculated using agglomerative hierarchical clustering, with the degree of similarity between different clusters being calculated by the average linkage method and the degree of similarity of different isolates calculated with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Table 1. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Shewanella spp. in this study.

| Strainantibiotic | OXA-48-negative strain | OXA-48-positive strains | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 (µg ml−1) | MIC90 (µg ml−1) | MIC50 (µg ml−1) | MIC90 (µg ml−1) | |

| IPM | ≤1 | 2 | 64 | 128 |

| MEM | ≤1 | ≤1 | 32 | 64 |

| ETP | ≤2 | ≤2 | 128 | >128 |

| CMZ | ≤2 | 4 | ≤2 | 16 |

| CAZ | ≤2 | ≤2 | >128 | >128 |

| CTX | ≤4 | ≤4 | 128 | >128 |

| TZP | ≤8/4 | ≤8/4 | ≤8/4 | ≤8/4 |

| SCF | ≤8/4 | ≤8/4 | ≤8/4 | ≤8/4 |

| CAV | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 |

| FEP | ≤4 | ≤4 | 16 | 64 |

| PB | 1 | 1 | ≤0.5 | >8 |

| TGC | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 |

| CIP | ≤1 | 2 | ≤1 | 4 |

| AK | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 |

| ATM | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 |

AK, amikacin; ATM, aztreonam; CAV, ceftazidime/avibactam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CMZ, cefmetazole; CTX, cefotaxime; ETP, ertapenem; FEP, cefepime; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; PB, polymyxin B; SCF, cefoperazone/sulbactam; TGC, tigecycline; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam.

Genetic environment of blaOXA-48-like genes in Zhejiang province

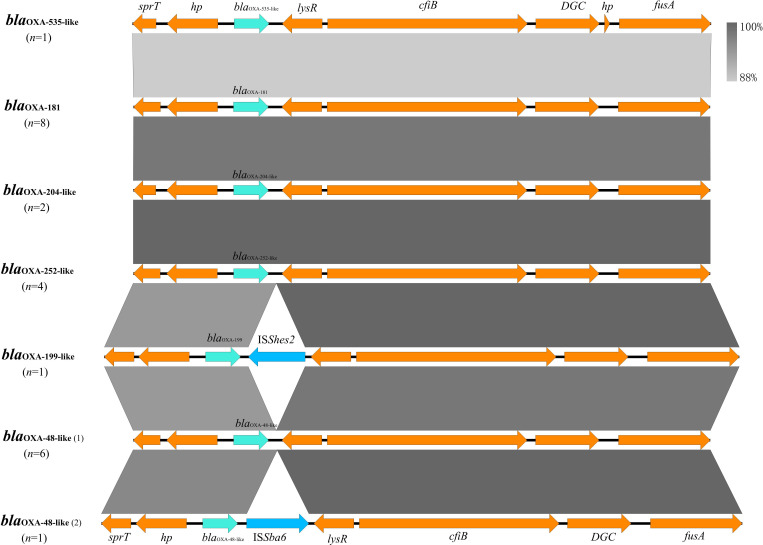

Genetic analysis suggested that blaOXA-48-like genes in all 23 Shewanella spp. were located on the chromosome. Despite variations in the sequences of blaOXA-48-like genes, all Shewanella species examined harboured these genes at an identical chromosomal locus. The core genetic contexts of blaOXA-48-like genes in Shewanella strains in this study were all sprT-hp-blaOXA-48-like-lysR-cfiB-DGC-fusA. Mobile elements were only observed in two strains inserted between the blaOXA-48-like and lysR genes, one of which is S. xiamenensis H282 from river water carrying blaOXA-199-like-ISShes2-lysR, and the other is S. xiamenensis F152 from hospital sewage carrying blaOXA-48-like-ISSba6-lysR (Fig. 5). The presence of such genes could be associated with the mobilization of blaOXA-48-like genes.

Fig. 5. Genetic context of blaOXA-48-like genes in this study. Cyan, blue and orange arrows indicate the antibiotic resistance gene blaOXA-48-like, mobile genetic element and other ORFs, respectively. Shading areas indicate the region of genetic elements sharing sequence identities. A number of strains with the corresponding genetic arrangements are given in brackets. Subtypes of the blaOXA-48-like genes are labelled alongside the corresponding arrows.

Discussion

Shewanella sp. is an important environmental species playing pivotal ecological roles, with several members being pathogenic to human beings [40]. Strains in this genus were considered important carriers and reservoirs of carbapenemase genes, particularly the Ambler class D β-lactamase which they carry on chromosomes [41]. Shewanella sp. was reported to be the progenitor of blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase genes, which were among the major causes of carbapenem resistance in clinically significant pathogens within the Enterobacterales order [13,14]. The Shewanella genus contained a total of 130 species at the time of writing, and a total of 58 OXA-48 variants were reported to date. Although the progenitors of several OXA-48-like carbapenemases have been investigated, there has been no systematic study reporting the association between different Shewanella species and these carbapenemase variants. Besides, the molecular epidemiology of Shewanella in Zhejiang province remained largely unknown. To address these issues, we analysed the largest collection of Shewanella genomes to our knowledge and performed genetic and phenotypic analysis on Shewanella collected from Zhejiang province. However, this study has certain limitations. The initial identification of collected strains was performed using MALDI-TOF MS, yet the available MS libraries contain only a limited number of Shewanella species references. This constraint raises the possibility of undetected Shewanella species that might have been missed during the identification process.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the progenitor of different blaOXA-48-like variants with a focus on the Shewanella population. Results in this study showed that different blaOXA-48-like variants originated from different Shewanella species, and only some of the Shewanella species were associated with the blaOXA-48 genes. In particular, S. xiamenensis could be the progenitor of different blaOXA-48 variants [16,18]. However, it is worth noting that the predominance of S. xiamenensis and S. algae in our findings may be influenced by their relatively higher abundance in the sampled populations, while other Shewanella species might be underrepresented due to their rarity. S. xiamenensis is a zoonotic pathogen commonly found in the aquatic ecosystem and rarely isolated from clinical samples [42]. Reflecting this rarity, our study, which examined a limited number of strains, did not include any S. xiamenensis isolates from clinical samples, aligning with the general scarcity of such clinical reports [39,42]. Our phylogenetic analysis further demonstrated that Shewanella spp. are progenitors of the blaOXA-48-like genes [17]. Besides, OXA-48-like carbapenemases have undergone constant evolution in Enterobacterales and were highly diverse, with at least five clades detected [13]. In our study, which was conducted with a small sample size in Zhejiang, the distribution of different Shewanella species appeared to be niche-specific: S. algae (n=12) and S. indica (n=1) strains were exclusively isolated from clinical settings, while S. xiamenensis (n=23) and S. mangrovisoli (n=2) were found in both hospital sewage and river water. However, due to the limited number of isolates analysed, the conclusions drawn from this study should be interpreted with caution, acknowledging the potential limitations on the generalizability of our findings. None of the clinical Shewanella isolates carried the blaOXA-48-like genes. Comparatively, all but one Shewanella isolate (S. mangrovisoli) from the water sample carried blaOXA-48-like. blaOXA-48-like genes in Shewanella spp. from Zhejiang were located on the chromosome. Findings in this study supported the notion that OXA-48-like carbapenemase originated from different environmental Shewanella species and was captured by clinical species, particularly Enterobacterales. Findings of this research underscore the significant function of Shewanella species within ecosystems, especially as the predominant origin of the notorious carbapenemase gene, blaOXA-48. It is imperative to enforce preventive strategies to curb the spread of these organisms in both hospital environments and communal settings.

Conclusions

In summary, our genomic analysis of all Shewanella strains in the database suggested that blaOXA-48-like was intrinsically carried by a few Shewanella species, and different blaOXA-48-like variants were associated with different Shewanella species. Particularly, the blaOXA-48-like genes carried by S. xiamenensis were highly diverse. Comparatively, none of the S. algae genomes carried blaOXA-48-like, although whether this result is influenced by species abundance requires further investigation. Our phylogenetic analysis of all OXA-48-like carbapenemases suggested they originated from different environmental Shewanella species and were captured by clinical species, particularly Enterobacterales. The distribution patterns of Shewanella species in Zhejiang province, with S. algae (n=12) and S. indica (n=1) isolated from clinical settings and S. xiamenensis (n=23) and S. mangrovisoli (n=2) from both hospital sewage and river water, should be interpreted in the context of our study’s limited sample size. blaOXA-48-like genes in Shewanella spp. in this study were located on the chromosome. Our findings underscored the pivotal ecological function of Shewanella species, notably as the primary conduit for the widely recognized carbapenemase gene, blaOXA-48.

Supplementary material

Abbreviations

- ANI

average nucleotide identity

- IDs

unique identifiers

- ISs

insertion sequences

- MICs

minimum inhibitory concentrations

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

Footnotes

Funding: This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2022YFD1800400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272392, 32300156, 82072341 and 81971987) and the Theme-Based Research Scheme (T11-104/22 R).

Author contributions: N.D. and Y.Z.:Conceptualization, statistical analysis, data visualization and writing – original draft. Y.W., X.J., Z.Y., C.L. and J.Y.: Sampling, statistical analysis and data visualization. H.Z., G.C. and S.C.: Materials, data visualization and funding acquisition. R.Z.: Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition and project administration. All authors commented on and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical statement: Ethical permission was granted by the Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2023-0733).

Contributor Information

Ning Dong, Email: dong.ning@connect.polyu.hk.

Rong Zhang, Email: zhang-rong@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Baker IR, Conley BE, Gralnick JA, Girguis PR. Evidence for horizontal and vertical transmission of Mtr-mediated extracellular electron transfer among the bacteria. mBio. 2021;13:e0290421. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02904-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yousfi K, Bekal S, Usongo V, Touati A. Current trends of human infections and antibiotic resistance of the genus Shewanella. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis . 2017;36:1353–1362. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2962-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Shewanella: from the briny depths below to human pathogen. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2014;40:293–312. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.726209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu K, Huang Z, Xiao Y, Wang D. Shewanella infection in humans: epidemiology, clinical features and pathogenicity. Virulence. 2022;13:1515–1532. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2022.2117831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Z, Yu K, Fu S, Xiao Y, Wei Q, et al. Genomic analysis reveals high intra-species diversity of Shewanella algae. Microb Genom. 2022;8:000786. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janda JM. Shewanella: a marine pathogen as an emerging cause of human disease. Clinic Microbiol Newsl. 2014;36:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2014.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller S, von Bonin S, Schneider R, Krüger M, Quick S, et al. Shewanella putrefaciens, a rare human pathogen: a review from a clinical perspective. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1033639. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1033639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, Morar M, Sung WWL, et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature. 2011;477:457–461. doi: 10.1038/nature10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finley RL, Collignon P, Larsson DJ, McEwen SA, Li X-Z, et al. The scourge of antibiotic resistance: the important role of the environment. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:704–710. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poirel L, Figueiredo S, Cattoir V, Carattoli A, Nordmann P. Acinetobacter radioresistens as a silent source of carbapenem resistance for Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1252–1256. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01304-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang R, Dong N, Shen Z, Zeng Y, Lu J, et al. Epidemiological and phylogenetic analysis reveals flavobacteriaceae as potential ancestral source of tigecycline resistance gene tet(X) Nat Commun. 2020;11:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18475-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv L, Wan M, Wang C, Gao X, Yang Q, et al. Emergence of a plasmid-encoded resistance-nodulation-division efflux pump conferring resistance to multiple drugs, including tigecycline, in Klebsiella pneumoniae. mBio. 2020;11:e02930–02919. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02930-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitout JD, Peirano G, Kock MM, Strydom K-A, Matsumura Y. The global ascendency of OXA-48-type carbapenemases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:00102–00119. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirel L, Héritier C, Nordmann P. Chromosome-encoded ambler class D beta-lactamase of Shewanella oneidensis as a progenitor of carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:348–351. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.348-351.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tacão M, Correia A, Henriques I. Environmental Shewanella xiamenensis strains that carry blaOXA-48 or blaOXA-204 genes: additional proof for blaOXA-48-like gene origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:6399–6400. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00771-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zong Z. Discovery of bla(OXA-199), a chromosome-based bla(OXA-48)-like variant, in Shewanella xiamenensis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tacão M, Araújo S, Vendas M, Alves A, Henriques I. Shewanella species as the origin of blaOXA-48 genes: insights into gene diversity, associated phenotypes and possible transfer mechanisms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;51:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potron A, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Origin of OXA-181, an emerging carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase, as a chromosomal gene in Shewanella xiamenensis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4405–4407. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00681-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mairi A, Pantel A, Sotto A, Lavigne J-P, Touati A. OXA-48-like carbapenemases producing Enterobacteriaceae in different niches. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37:587–604. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bortolaia V, Kaas RS, Ruppe E, Roberts MC, Schwarz S, et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mende DR, Sunagawa S, Zeller G, Bork P. Accurate and universal delineation of prokaryotic species. Nat Methods. 2013;10:881–884. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:127–128. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.In C. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Testing ECoAS Clinical breakpoints and dosing of antibiotics. 2019.

- 30.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li R, Xie M, Dong N, Lin D, Yang X, et al. Efficient generation of complete sequences of MDR-encoding plasmids by rapid assembly of MinION barcoding sequencing data. Gigascience. 2018;7:1–9. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, et al. The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D206–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frenk S, Rakovitsky N, Kon H, Rov R, Abramov S, et al. OXA-900, a novel OXA sub-family carbapenemase identified in Citrobacter freundii, evades detection by commercial molecular diagnostics tests. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1898. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9091898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zong Z. Nosocomial peripancreatic infection associated with Shewanella xiamenensis. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:1387–1390. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.031625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alex A, Antunes A. Whole-genome comparisons among the genus Shewanella reveal the enrichment of genes encoding ankyrin-repeats containing proteins in sponge-associated bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:5. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang X, Miao B, Zhao X, Bai X, Yuan M, et al. Unveiling the emergence and genetic diversity of OXA-48-like carbapenemase variants in Shewanella xiamenensis. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1325. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11051325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Y, Yao T, Wang Y, Zhao Z, Yang X, et al. First clinical isolation report of Shewanella xiamenensis from chinese giant salamander. Vet Res Forum. 2022;13:141–144. doi: 10.30466/vrf.2021.138797.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.