Abstract

Background

HPV vaccination is highly effective in preventing HPV infection and subsequent precancers and invasive cancers related to HPV. Unfortunately, vaccine coverage in the U.S. lags behind national and global targets. College students are an important audience for catch-up vaccination given suboptimal population coverage in adolescents. This study examined factors associated with college healthcare provider (HCP) practices for routinely screening HPV vaccination history of female college students.

Methods

One thousand two hundred twenty-one U.S. college HCPs completed surveys and reported on a variety of screening practices in college health centers, including assessing the HPV vaccination status of female college students. Participants included nurse practitioners, physicians, and physician assistants.

Results

Forty-five percent of college HCPs reported routinely screening the HPV vaccination histories of most (≥ 70%) of their female students. Nurse practitioners (NPs) were more likely than other providers to consistently assess HPV vaccination status. In multivariable logistic regression modeling, high rates of routine HPV vaccination screening were associated with NP role, more positive provider attitudes and self-efficacy toward screening, larger institutions, college-level policies, in-service trainings and electronic health record prompts that supported HPV vaccination history screening. No differences were found by other provider demographic factors, institution type or region.

Conclusions

College health centers present unique opportunities to identify unvaccinated female students and offer or refer them for vaccination. Future research needs to examine HPV vaccination status and screening among other types of college students and identify the multi-level factors that act as facilitators and barriers to assessing HPV vaccination status and offering the HPV vaccine.

Keywords: College health, HPV vaccination, Female college students

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an important tool for primary prevention of HPV infection. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection; 80% of teens and adults will become infected [1]. Most infections are transient but some infections persist and high-risk strains of HPV can cause precancer or cancer of the cervix as well as anal, oral-pharyngeal, penile, vaginal and vulvar cancers [1, 2]. HPV vaccination prevents an estimated 90% of HPV-related cancers [2].

HPV vaccination recommendations

HPV vaccination is primarily targeted to children/adolescents ages 9–12, for optimal effectiveness (before onset of sexual activity and potential HPV exposure). Only two doses are required for completion if initiated before age 15, whereas three doses are required thereafter [3]. Healthy People 2030 objectives include a target of 80% HPV vaccination completion for adolescents ages 13–15, but as of 2022, the rate of HPV vaccination completion among 13–15-year-olds in the U.S. was only 58.6% [4] and still only 62.6% if including adolescents up to age 17 [5]. Catch-up vaccination is now recommended for unvaccinated adolescents and adults up to age 26, with shared decision-making for adults up to age 45 [3]. Most research to address suboptimal HPV vaccination rates has focused on parents’ attitudes and intentions to vaccinate their children [6–9] and strategies to impact parents’ decisions to have their children get the HPV vaccine [10–13]. There is less evidence regarding catch-up vaccination for emerging adults over age 18 who may be making decisions regarding HPV vaccination themselves.

Screening for HPV vaccination history

In addition to the college healthcare provider’s (HCP’s) role in screening and intervening for various health risks in the college health setting [14], careful review of student’s health history is important to identify whether students are up to date on routine preventive health measures such as HPV vaccination. Unlike other childhood and adolescent vaccinations, HPV vaccination is not required for entry to college. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends catch-up HPV vaccination for all unvaccinated persons (regardless of gender) up to age 26 [3]. The American College Health Association (ACHA) recommends catch-up vaccination for unvaccinated students up to age 26, [15] because vaccination completion remains low in this age group. In 2021, only 51.4% of college students who participated in the National College Health Assessment survey reported having completed HPV vaccination; 44.5% had not initiated HPV vaccination or did not know their vaccination status [16].

Studies suggest that there is high acceptability of HPV vaccine among college students, [17–19] but limited awareness that it is still an option for them and may be available to them through their college health center. [20] HCP discussion of HPV vaccine in this setting is an important factor in increasing HPV vaccine uptake [21, 22]. College HCPs can play an important role in identifying students who have not completed their HPV vaccine series. However, little is known about provider practices related to assessing HPV vaccination status in college health settings. The purpose of the current study was to examine college HCP attitudes and practices related to screening female college students for HPV vaccination completion and identify provider- and college-level factors associated with consistent screening.

Methods

Design

The National College Healthcare Provider Survey was the first phase of a three-phase study of college health screening practices funded by the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ; R01HS027154) A nationally representative sample of nurse practitioners [NPs], physicians [MD/DOs] and physician assistants [PAs]) was recruited and invited to participate in the survey in 2022 [14]. The study framework [14] was adapted from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [23] and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [24, 25]. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the IRB of Binghamton University (#FWA00000174/Study00002435) prior to data collection.

Site and sample

A national sampling frame of college HCPs was created from the U.S. Department of Education database [26] and identification of healthcare providers from the college/university websites (Procedures are described in detail elsewhere [14]). In order to be included, colleges had to be accredited, general degree-granting colleges or universities, enroll more than 2,500 undergraduate students, and provide an on-campus college health center with providers identified by name on their website. Providers were eligible to participate if they were NPs, MD/DOs or PAs employed in the college health center, over the age of 18 and able to read and understand English [14].

Procedures

Participants were recruited using an adaptation of the Dillman Tailored Method [27] (described in detail elsewhere [14]). Potential participants were contacted by mail and invited to participate. Survey packets and reminder postcards were also sent via the U.S. mail. Participants were offered $20 Amazon.com gift cards as incentives to participate and were provided with a link to complete the surveys online if they preferred.

Measures

College HCPs were asked about their demographic characteristics, attitudes, self-efficacy and practices related to “routinely” assessing/screening female students’ HPV vaccination history and offering HPV vaccination. Potentially influential college/organization-level influences (e.g., college location, type, policies to screen, recent trainings on how to assess HPV vaccination status, and electronic health record [EHR] prompts to screen) were also assessed. Single-item measures regarding HPV vaccination were informed by constructs from the TPB [23] and CFIR [24, 25] theoretical frameworks and have not been previously validated.

Demographics

Demographic characteristics included HCP gender identity, age, race, Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity, role (MD/DO, PA, NP), college region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), urbanicity of the college location (rural, suburban, urban), college type (public, private with religious affiliation, private without religious affiliation), Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU)/Minority Serving Institution (MSI) designation, and undergraduate enrollment (< 2,500, 2,500 – 4,999, 5,000 – 9,999, 10,000–19,999, ≥ 20,000). Trichotomous variables for HCP role, urbanicity and college type were recoded for analysis as dichotomous variables: NP vs. other (physician/PA); urban vs. other (rural/suburban); and public vs. other (private secular/private religious).

HPV vaccination-related attitudes and self-efficacy

College HCPs were asked: “In your opinion, is it a bad idea or a good idea to routinely screen for or ask about HPV vaccine history with every female student who visits the college health center?” Response options were on a 5-point Likert-type scale (“very bad idea” to “very good idea”). Participants were also asked about their confidence or self-efficacy related to screening students’ HPV vaccination status with the question: “During the next semester, I am confident that I could ask female students about their HPV vaccination status. 5-point Likert-type response options ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” These provider attitude and self-efficacy questions were single-item measures based on TPB constructs [23]. For ease of interpretation, responses were later dichotomized into two categories: good idea/positive attitude (“good idea/very good idea”) vs. other and agree/positive self-efficacy (“somewhat agree/strongly agree”) vs. other.

College-level factors

HCPs were asked several yes/no questions about practices, policies and other organizational factors in their college health centers: “Does your college health center have a policy to routinely ask about or screen all female students for HPV vaccine history?”; “Do the electronic health records (EHRs) include prompts or reminders to ask about or screen for HPV vaccine history?” (for those using EHRs); and “During the past year, have there been any trainings or in-services on HPV Vaccine?” These were single-item measures and response options were binary (1 = yes; 0 = no).

Outcome Variable: HPV vaccination-related practices

College HCPs who indicated that they provided direct care to students were asked: “Of the female college students who you saw at the college health center during the spring 2022 semester, approximately what percentage (%) did you screen for or ask about HPV vaccine history?” Response options ranged from 0 to 100% in increments of 10% (e.g., 0%, 10%, 20%, etc.). A dichotomized outcome variable was then created to indicate “consistent screening” or routinely screening the HPV vaccination history/status of “most” female students, defined as routinely screening ≥ 70% of their female students (1 = routinely screening ≥ 70% of female students; 0 = routinely screening < 70% of female students).

Analysis

All of the survey data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM version 28). Paper surveys were reviewed and the data were double-entered and verified in a separate database prior to merging with the data from the online surveys. Data were examined for non-normal distributions and extreme values. Percentages of missing data and patterns of missingness were assessed for each variable. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and means were reported for categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively.

Multivariable logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of demographic characteristics, providers’ HPV vaccination-related attitudes and self-efficacy, and college-level factors on the likelihood of HCPs routinely screening the HPV vaccination status of most (≥ 70%) of their female student patients. P-values of the regression coefficients were used to identify statistically significant predictors, and adjusted odds ratios were examined to explain their effects on the likelihood of consistent routine screening of HPV vaccination status. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses. The potential for multicollinearity among predictor variables was examined using the Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs). A maximum VIF in excess of 10 is commonly taken as an indicator of potentially harmful collinearity that should be addressed [28]. In this study, the VIFs of all predictors range 1 and 2, indicating no concerning multicollinearity among predictors in the multivariable regression model.

Results

Participation and demographics

1,221 surveys were returned by college HCPs from 49 states and the District of Columbia (40.78% response rate); two-thirds completed online surveys and one-third completed paper surveys. Sixty-two surveys were eliminated for duplicate submissions and/or for having extensive amounts of missing data. We analyzed data from a final sample of 1,159 participants [14]. Participant characteristics are described in Table 1; the majority of participants identified as female, were White, and were nurse practitioners. Nearly 3/4 of participants were employed by state colleges/universities and 2/3 were from large universities with more than 10,000 undergraduate students. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for individual provider characteristics and HPV vaccine-related survey responses as well as organizational factors that could potentially impact assessing/screening for HPV vaccination history.

Table 1.

National College Healthcare Provider Survey demographics and HPV vaccine responses (N = 1,159)

| Frequency/Mean | Values | Missing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCP Age | 25/233/299/360/198/18 | 1–6: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69,70 (years old) | 26 |

| HCP Gender | 170/938 | 0–1: male vs. female | 51 |

| HCP Race | 49/932/92/7/22 | 1–5: African American or Black, Caucasian/white, Asian/Pacific islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Other | 57 |

| HCP Ethnicity | 1072/50 | 0–1: non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic | 37 |

| HCP Role | 517/599 | 0–1: physician/physician assistant vs. nurse practitioner | 43 |

| College Type | 315/844 | 0–1: private vs. public | 0 |

| HBCU/MSI | 968/169 | 0–1: no, yes | 22 |

| Urbanicity | 602/555 | 0–1: rural/suburban vs. urban | 2 |

| Enrollment | 26/168/242/274/432 | 1–5: < 2,500, 2,500–4,999, 5,000–9,999, 10,000–19,999,20,000 | 17 |

| Region | 336/250/315/258 | 1–4: Northeast, Midwest, South, West | 0 |

|

HCP attitudes toward screening “In your opinion is it a bad idea or a good idea to routinely screen for HPV vaccine history with every female student who visits the health center” |

149/970 | 0–1: neutral/bad idea/very bad idea vs. good idea/very good idea | 40 |

|

HCP attitudes toward offering HPV vaccination “College HCPs should offer HPV vaccinations to unvaccinated female students” |

195/921 | 0–1: neutral/disagree/strongly disagree vs. agree/strongly agree | 43 |

|

HCP self-efficacy for screening “During the next semester, I am confident that I could ask female students about their HPV vaccination status” |

116/996 | 0–1: neutral/disagree/strongly disagree vs. agree/strongly agree | 47 |

|

HCP self-efficacy for offering HPV vaccination “During the next semester, I am confident that I could offer HPV vaccination to unvaccinated female students.” |

193/912 | 0–1: neutral/disagree/strongly disagree vs. agree/strongly agree | 54 |

|

Policy to screen Does your college health center have a policy to routinely ask about or screen all female students for HPV vaccine history? |

465/626 | 0–1: no, yes | 68 |

|

EHR prompt to screen (For those using electronic health records) “Do the EHRs include prompts or reminders to ask about or screen for HPV vaccine history?” |

647/408 | 0–1: no, yes | 104 |

|

In-service/training in last year “During the past year, have there been any trainings or in-services HPV vaccine?” |

895/136 | 0–1: no, yes | 128 |

|

HPV vaccine screening rates “Of the female college students who you saw at the college health center during the spring 2022 semester, approximately what percentage (%) did you screen for or ask about HPV vaccine history?” |

54.71 ± 35.81 | 0–100: integer | 75 |

| HCP reports consistent screening of female students’ HPV vaccination history | 597/487 | 0–1: no (< 70) vs. yes (70) | 75 |

Abbreviation: HCP Healthcare provider, HPV Human papillomavirus, NP Nurse practitioner, PA Physician assistant, MD/DO Medical doctor/doctor of osteopathy, HBCU Historically Black colleges and universities, MSI Minority serving institution, EHR Electronic health record

Assessing/screening for HPV vaccination history/status

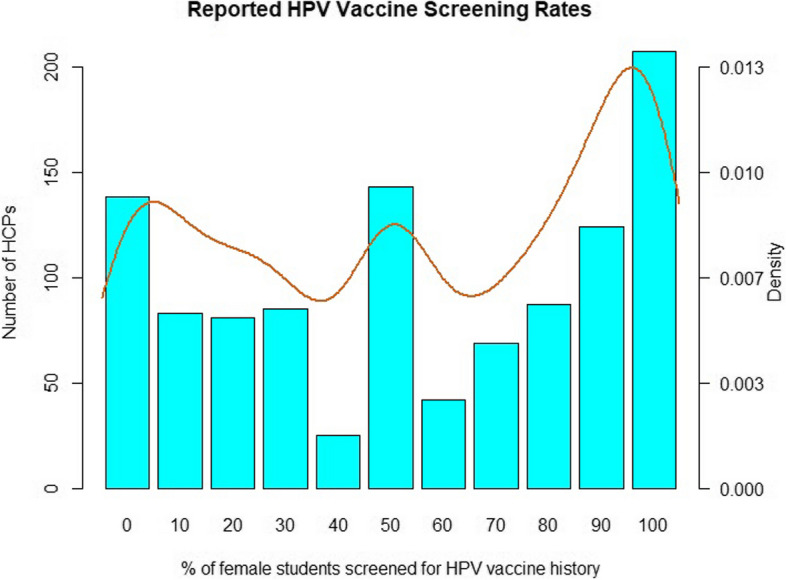

The mean HPV vaccination history screening rate reported by college HCPs was 54.71% (median = 50%); however, there was significant variability in screening rates, with responses as low as 0% and as high as 100%. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of HPV vaccination screening rates among college HCPs, with an orange density line that highlights the trends. Screening rates cluster around 0% and 100%, with fewer HCPs in the middle. Given this variability in reported screening rates, we focused our multivariable analyses on provider and college/organizational predictors of consistent routine screening of most female students’ HPV vaccination history (defined as reported screening rate of ≥ 70%). This threshold was chosen based on perceived clinical relevance of screening to mean screening “most” students. Based on the distribution of reported screening rates we wanted to choose a rate that was above the median and mathematically a 70% screening rate is the 60th percentile for this variable.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of HPV vaccine screening rates reported by college healthcare providers (HCPs)

Figure 1 caption: The bar chart shows the number of college HCPs by screening rate, with a density curve overlay for trend visualization.

HCP demographic characteristics that were significantly correlated with consistent routine screening of students’ HPV vaccination history in bivariate analyses were included in the logistic regression model along with potentially influential provider and organizational constructs from the TPB [23] and CFIR [24, 25] theoretical frameworks. Table 2 presents the results of the multivariable logistic regression model used to examine provider- and college-level predictors of consistent routine screening for HPV vaccination history. The logistic regression model was statistically significant (p < 0.001) and correctly classified 73.17% of the HCPs with Cross Validation. Multiple pseudo- R2 measures were examined which indicated a moderate model fit (Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.3987, Tjur’s R2 = 0.3138, and McFadden’s R2 = 0.2569) [29].

Table 2.

Logistic regression for predictors of consistent screening of female students' HPV vaccination history

| B | SE |

Adjusted OR |

95%CI | Wald Statistic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCP Role (NP vs. other) | 0.26 | 0.09 | 1.3 | [1.09,1.54] | 2.97 | 0.003 |

| HCP attitudes toward screening | 0.39 | 0.11 | 1.47 | [1.19,1.87] | 3.37 | 0.001 |

| HCP self-efficacy for screening | 0.55 | 0.14 | 1.73 | [1.34,2.37] | 3.82 | < 0.001 |

| College type (State vs. private) | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.96 | [0.78,1.19] | −0.34 | 0.737 |

| HBCU/MSI | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.97 | [0.81,1.15] | −0.38 | 0.704 |

| Urbanicity (urban vs. other) | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.96 | [0.81,1.14] | −0.46 | 0.644 |

| Enrollmenta | 0.27 | 0.11 | 1.31 | [1.05,1.63] | 2.39 | 0.017 |

| REGION (baseline Northeast)a | ||||||

| Midwest | −0.02 | 0.26 | 0.98 | [0.59,1.63] | −0.07 | 0.945 |

| South | −0.10 | 0.24 | 0.90 | [0.56,1.45] | −0.43 | 0.665 |

| West | 0.17 | 0.27 | 1.18 | [0.70,2.00] | 0.62 | 0.536 |

| Policy to screen | 0.86 | 0.10 | 2.37 | [1.96,2.87] | 8.93 | < 0.001 |

| EHR prompt to screen | 0.23 | 0.09 | 1.26 | [1.05,1.51] | 2.47 | 0.013 |

| In-Service/training in last year | 0.25 | 0.09 | 1.29 | [1.09,1.53] | 2.91 | 0.004 |

| Nagelkerke's R2 = 0.3987 | ||||||

| Tjur's R2 = 0.3138 | ||||||

| McFadden's R2 = 0.2569 | ||||||

Abbreviation: HCP Healthcare provider, HPV Human papillomavirus, NP Nurse practitioner, HBCU Historically Black colleges and universities, MSI Minority serving institution, EHR Electronic health record

aEnrollment is characterized by a 5-point Likert scale with 1–5 indicating < 2,500, 2,500–4,999, 5,000–9,999, 10,000–19,999, 20,000, and thus is treated as a continuous independent variable in the logistic regression; Region is treated as a nominal variable with northeast as the baseline group; Remaining variables are all binary variables

Provider-level predictors

At the individual provider-level, significant predictors of consistent routine screening were HCP role, positive attitudes and perceived self-efficacy towards assessing HPV vaccination history. NPs had 1.3 times greater odds of reporting routinely screening for HPV vaccination history than other providers (PAs/MDs/DOs). Providers who reported positive attitudes towards screening for HPV vaccination history had 1.5 times greater odds of reporting that they routinely asked most (≥ 70%) of their female college students about HPV vaccination history compared to others. Similarly, HCPs who reported positive self-efficacy/confidence related to assessing/screening female students’ HPV vaccination history had 1.7 times greater odds of reporting routinely screening most (≥ 70%) of their female college students compared to those who reported low self-efficacy/confidence.

College-level predictors

At the college/organization-level, the size of the college/university, health center policies and prompts to screen HPV vaccination history and recent in-services/trainings on HPV vaccination were all found to be significantly associated with high rates of routine screening for HPV vaccination status. HCPs practicing in colleges/universities with larger enrollment were more likely than those in smaller schools to report routinely screening for HPV vaccination history. Providers whose college health centers had a policy to screen for HPV vaccination had 2.4 times greater odds of reporting consistent routine screening practices compared to other HCPs. Providers who reported that their college health center had EHR prompts or reminders to ask about or screen for HPV vaccination history had 1.3 times greater odds of reporting high rates of routine screening of female students compared to HCPs without EHR prompts. Those who reported their organizations offered HPV vaccine-related trainings or in-services during the past year were also more likely to report high rates of routinely screening female students’ HPV vaccination status compared to other providers. At the organizational level, no significant differences were found between public and private institutions nor urban vs rural/suburban locations. At the system level, no significant differences were found in rates of routine screening for HPV vaccination history by region.

Discussion

We examined college HCP attitudes and practices related to screening the HPV vaccination history/status of female students as part of a national survey of college HCPs. We found that college HCPs on average reported routinely screening the HPV vaccination histories of approximately half of their female college students; however, only 45% of college HCPs reported routinely screening most (≥ 70%) of the female students in their college health settings. In multivariable analyses, provider-level as well as college-level factors were found to be significant influences as to whether college HCPs consistently screened/assessed the HPV vaccination status of most of their female students.

At the individual provider level, we found NPs were more likely to routinely assess/screen their female students’ HPV vaccination histories than PAs or MDs. This is consistent with previous findings that NPs report higher rates of screening for a variety of health-related issues in college health settings [14, 30]. In addition, consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [23], we found that college HCPs with positive attitudes towards screening for HPV vaccination history and those who reported greater self-efficacy regarding screening were more likely to report consistently screening/assessing the HPV vaccination history of most of their female college students. This finding suggests that some college HCPs view HPV vaccination screening as a priority and have adopted it as part of their routine clinical practice. Although there is strong evidence that provider recommendations act as important motivators in increasing HPV vaccination among college students [21, 22], in order to recommend vaccination, college HCPs have to first identify students who have not completed HPV vaccination. Given that fewer than half of college HCPs are consistently and routinely screening their female college students’ HPV vaccination history, there is room and a need for practice improvement in this area. We found that provider attitudes and confidence were positively associated with HPV vaccination screening practices. Interventions to improve HPV vaccination screening practices should promote positive attitudes and self-efficacy towards screening. However, a previous qualitative study with college HCPs showed time constraints and lack of readily available HPV vaccine documentation impacted HCPs’ attitudes towards routinely screening all students’ HPV vaccination history. HCPs also reported greater ease integrating HPV vaccination history screening into women’s health visits vs. primary care visits [31]. These findings suggest that practice-level factors beyond the individual provider would also need to be addressed to support routine screening for HPV vaccination history.

At the college/organization level, policies regarding HPV vaccination history screening, in-service trainings and EHR prompts increased the likelihood that college HCPs routinely screened most of their female college students for HPV vaccination status/history. If the practice/organization has prioritized HPV vaccination as a preventive health measure, policies and systems may be in place and the likelihood of identifying unvaccinated students may be increased. A previous study in a pediatric practice setting found that provider and staff education as well as regular feedback on clinic vaccination rates increased provider prioritization of HPV vaccination and subsequently HPV vaccination rates [32]. In terms of system-level interventions, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend staff and provider education to ensure consistent messaging across the practice regarding HPV vaccine, and health center policies to screen patients at every encounter regarding their HPV vaccination status [33].

No significant differences in college HCPs’ reported rates of routine screening of female students’ HPV vaccination status were found by college type (except enrollment size), urbanicity or region. To our knowledge, no previous studies have directly examined college HCP practices regarding HPV vaccine at the national scale. There are however known regional variations in HPV vaccination rates among young adults in the US, with lower rates reported in the South, West and Midwest compared to the Northeast [34]. Given previous region-specific studies showing college HCP recommendation is an important influence on vaccine uptake [21, 35], more in-depth study of system-level factors that might influence college HCP practices for screening HPV vaccination status and recommending/offering HPV vaccination is needed.

College students over the age of 18 are often living independently for the first time and making their own self-care and healthcare decisions [14]. Given that a recent study found that more than half of female college students used college health services during the past 6 months [36], encounters with college HCPs represent an important opportunity to identify students who have not yet completed HPV vaccination and may be interested in getting the HPV vaccine.

Limitations

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. This was a cross-sectional survey, with survey responses representing provider-reported practice at a moment in time. The survey also relied on self-reported rates of screening/assessing for HPV vaccination history; it is possible that providers may have over- or under-estimated their actual screening practices. In addition, the primary funded focus of the National College Healthcare Provider Survey was on screening for IPV/SV in female college students; as such, the measures of HPV vaccination-related attitudes and practices were abbreviated. Our study was strengthened by a large national sample of college HCPs representing diverse geographic regions as well as college and provider types.

Implications

Low rates of routine screening for HPV vaccination history among college HCPs seem to represent serious gaps and missed opportunities for identifying unvaccinated or under-vaccinated students. College health centers are uniquely positioned to help promote completion of the recommended HPV vaccine series and reduce the risk of future HPV-related cancers and other sequelae. Future studies should examine whether all students, including male and nonbinary/transgender students, are being screened for HPV vaccination history and offered HPV vaccination in college health settings.

Conclusions

New strategies are needed to achieve greater HPV vaccination coverage in the US and reduce the future risk of cervical and other HPV-related cancers. College students are an important audience for catch-up vaccination in the young adult population, but our national study found that many college HCPs are not routinely assessing the HPV vaccination histories of their female college students. Future research is needed to further understand and address the multi-system level influences of HCP screening practices in order to promote provider beliefs and self-efficacy to screen for HPV vaccination status and identify students eligible for vaccination. Provider attitudes and beliefs and organizational policies and trainings that are found to facilitate the uptake of routine screening of HPV vaccination status should be incorporated into the design of theory-based, tailored interventions to promote the routine screening of HPV vaccination status among all college students.

Authors’ contributions

K.H. and M.S. conceptualized and designed the study; E.L., B.S., K.H., and M.S. contributed to data analysis and interpretation; B.S. and B.L. conducted data analysis and prepared Tables 1-2; E.L., K.H., and B.S., drafted and revised the manuscript. M.S., contributed to manuscript revisions. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); R01HS027154 (M. Sutherland and M.K. Hutchinson, MPIs), Multi-level Influences of Violence Screening in College Health Centers; funded in part by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): R03HS029605 (E. Liebermann, PI).

Data availability

Data is available on request to Melissa Sutherland @masutherland@uri.edu.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the IRB of Binghamton University (#FWA00000174/Study00002435), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infections. 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/hpv.htm. Cited 2022 Jul 16.

- 2.National Cancer Institute. HPV and Cancer. 2021. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer. Cited 2022 Jul 16.

- 3.Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Trends Progress Report. Bethesda, MD: NIH, DHHS; 2024. Available from: https://progressreport.cancer.gov. Cited 16 Jul 2022.

- 5.Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Valier MR, Fredua B, et al. Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(34):912–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trim K, Nagji N, Elit L, Roy K. Parental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours towards Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Their Children: A Systematic Review from 2001 to 2011. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szilagyi PG, Albertin CS, Gurfinkel D, Saville AW, Vangala S, Rice JD, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of HPV vaccine hesitancy among parents of adolescents across the US. Vaccine. 2020;38(38):6027–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galbraith KV, Lechuga J, Jenerette CM, Moore LAD, Palmer MH, Hamilton JB. Parental acceptance and uptake of the HPV vaccine among African-Americans and Latinos in the United States: A literature review. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisk LE, Allchin A, Witt WP. Disparities in Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Awareness Among US Parents of Preadolescents and Adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(2):117–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenhauer L, Hansen BR, Pandian V. Strategies to improve human papillomavirus vaccination rates among adolescents in family practice settings in the United States: A systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(3–4):341–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krantz L, Ollberding NJ, Beck AF, Carol BM. Increasing HPV Vaccination Coverage Through Provider-Based Interventions. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57(3):319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vollrath K, Thul S, Holcombe J. Meaningful Methods for Increasing Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Rates: An Integrative Literature Review. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32(2):119–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33(9):1223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland MA, Hutchinson MK, Si B, Ding Y, Liebermann E, Connolly SL, et al. Health screenings in college health centers: Variations in practice. J American College Health. 2024;1–8. 10.1080/07448481.2024.2361307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.American College Health Association. ACHA Guidelines: Immunization Recommendations for College Students. 2022. Available from: https://www.acha.org/documents/resources/guidelines/ACHA_Immunization_Recommendations_April2022.pdf. Cited 2022 Jul 16.

- 16.American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment III-Fall 2021 Reference Group Executive Summary. Available from: https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-III_FALL_2021_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf. Cited 16 Jul 2022.

- 17.LaJoie AS, Kerr JC, Clover RD, Harper DM. Influencers and preference predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among US male and female young adult college students. Papillomavirus Research. 2018;5:114–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuño VL, Gonzalez M, Loredo SM, Nigon BM, Garcia F. A Cross-Sectional Study of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Utilization Among University Women: The Role of Ethnicity, Race, and Risk Factors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20(2):131–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NatipagonShah B, Lee E, Lee SY. Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices Among U. S. College Students Concerning Papillomavirus Vaccination. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):380–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellogg C, Shu J, Arroyo A, Dinh NT, Wade N, Sanchez E, et al. A significant portion of college students are not aware of HPV disease and HPV vaccine recommendations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1760–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLendon L, Puckett J, Green C, James J, Head KJ, Yun Lee H, et al. Factors associated with HPV vaccination initiation among United States college students. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(4):1033–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnard M, Cole AC, Ward L, Gravlee E, Cole ML, Compretta C. Interventions to increase uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine in unvaccinated college students: A systematic literature review. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2019;14: 100884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci. 2009;4(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation Sci. 2022;17(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Education Statistics [NCES.. National Center for Educational Statistics. n.d. Available from: https://nces.ed.gov/. Cited 16 Jul 2022.

- 27.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed mode surveys: The tailored design method, 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2014. xvii, 509 p. (Internet, phone, mail, and mixed mode surveys: The tailored design method, 4th ed.).

- 28.Mason CH, Perreault WD. Collinearity, Power, and Interpretation of Multiple Regression Analysis. J Mark Res. 1991Aug;28(3):268–80. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes G, Choudhury RA, McRoberts N. Summary Measures of Predictive Power Associated with Logistic Regression Models of Disease Risk. Phytopathology®. 2019;109(5):712–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sutherland MA, Hutchinson MK. Intimate partner and sexual violence screening practices of college health care providers. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;39:217–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glenn BA, Nonzee NJ, Tieu L, Pedone B, Cowgill BO, Bastani R. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in the transition between adolescence and adulthood. Vaccine. 2021;39(25):3435–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLean HQ, VanWormer JJ, Chow BDW, Birchmeier B, Vickers E, DeVries E, et al. Improving Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Use in an Integrated Health System: Impact of a Provider and Staff Intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(2):252–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Five Ways to Boost Vaccination Rates. 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vaccination-considerations/boost-rates.html. Cited 2024 Aug 15.

- 34.Adjei Boakye E, Babatunde OA, Wang M, Osazuwa-Peters N, Jenkins W, Lee M, et al. Geographic Variation in Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Initiation and Completion Among Young Adults in the US Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(3):387–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vu M, Bednarczyk RA, Escoffery C, Getachew B, Berg CJ. Human papillomavirus vaccination among diverse college students in the state of Georgia: who receives recommendation, who initiates and what are the reasons? Health Educ Res. 2019;34(4):415–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sutherland MA, Fantasia HC, Hutchinson MK. Screening for Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence in College Women: Missed Opportunities. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26(2):217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on request to Melissa Sutherland @masutherland@uri.edu.