Abstract

Background:

Black women, relative to their Black male and White counterparts, may be more prone to experiencing racism and sexism in academic and other professional settings due to the “double jeopardy” or stigma of being both Black and a woman. Few studies have quantitatively studied how Black women in academic and professional spaces may mitigate the oppressive circumstances experienced by engaging in a coping strategy called identity shifting.

Objectives:

This study used an intersectional framework to investigate the relationships between the strong Black woman (SBW) stereotype, gendered racial identity centrality (GRIC), identity shifting, and mental health outcomes among 289 Black women (Mage = 29.46 years, SD = 10.74). It was hypothesized that there was a significant positive relationship between endorsement of the SBW schema, GRIC, and identity shifting. Additionally, we hypothesized the relationship between SBW and identity shifting is moderated by mental health such that more (a) depressive (b) and anxiety symptoms will result in a stronger relationship between stereotype endorsement and identity shifting strategies.

Design:

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional design using data collected in 2019 and 2020 from a larger validation study.

Methods:

Participants were recruited through emails, campus flyers, text messages, and social media postings. After providing informed consent, participants completed a 30- to 40-min online survey via Qualtrics.

Results:

There was partial support for the first hypothesis. While greater endorsement of the SBW stereotype by Black women did result in engagement with more identity shifting strategies, the relationship between these strategies and GRIC was not significant. The second hypothesis was not supported as mental health variables did not moderate the relationship between SBW and identity shifting.

Conclusion:

The importance of examining the gendered racial experiences of Black women is discussed, along with the importance of addressing SBW and identity shifting in academia and in professional workspaces.

Keywords: strong Black woman, identity shifting, gendered racial identity, anxiety, depression, Black women

Plain language summary

The strong Black woman stereotype and identity shifting among Black women in academic and other professional spaces

Black women, due to the ‘double jeopardy’ or stigma of being both Black and a woman, may be more prone to experiencing racism and sexism in academic and professional settings, relative to their Black male and White male and female counterparts. Few studies have quantitatively studied how Black women in academic and professional spaces may mitigate the oppressive circumstances experienced by engaging in a coping strategy called identity shifting. This study used an intersectional framework to investigate the relationships between the Strong Black Woman (SBW) stereotype, gendered racial identity centrality (GRIC), identity shifting, and mental health outcomes among 289 Black women (Mage = 29.46 years, SD = 10.74). It was hypothesized that there was a significant positive relationship between endorsement of the SBW stereotype, GRIC, and identity shifting and the relationship between SBW and identity shifting is moderated by mental health such that more (a) depressive and (b) anxiety symptoms will result in a stronger relationship between stereotype endorsement and identity shifting strategies. All participants completed a 30–40-minute online survey via Qualtrics. There was partial support for the first hypothesis. While greater endorsement of the SBW stereotype by Black women did result in engagement with more identity shifting strategies, the relationship between these strategies and GRIC was not significant. The second hypothesis was not supported as mental health variables did not moderate the relationship between SBW and identity shifting.

Introduction

Black (for the purposes of our study, “Black” is an inclusive term to represent all people of African descent) women, due to the “double jeopardy” or stigma of being both Black and a woman, may be more prone to experiencing racism and sexism in academic and other professional settings (i.e., workplace or environment where people work or conduct business), relative to their Black male and White counterparts. 1 The combination of racial and gender-related stress experienced by Black women in the workplace increases their allostatic load (i.e., wear and tear on the body), and can facilitate other mental and physical health problems. 2 Additionally, it can and influence their upward mobility in the workplace. 3 Black women remain underrepresented in leadership positions in academic (e.g., college/universities, academic centers, and laboratories) workspaces, and due to power structures, many are victims of discrimination, tokenism, and/or workplace bullying. Work by Thomas et al. 4 found that Black women in academia are prone to experiencing what is referred to as the “Pet to Threat” phenomenon. The Pet to Threat phenomenon illustrates women of color (e.g., Black women) may be initially perceived as non-threatening and compliant at the beginning of their careers, often viewed as “pets.” However, as they progress professionally, they are more likely to report being targets of discrimination or workplace bullying because they are seen as a threat. For example, Dr. Antoinette Candia-Bailey was a Black woman Vice President at Lincoln University in Missouri who experienced harassment and bullying by her White male supervisor. She was ignored when she expressed concerns about her experiences of discrimination, which impacted her mental health, and subsequently died by suicide. 5 Due to experiences of discrimination, tokenism, marginalization, and isolation, Black women are more likely to experience stress and subsequently may develop reactive coping strategies. 6

Few studies have quantitatively studied how Black women in academic and other professional spaces may mitigate the oppressive circumstances experienced by engaging in a coping strategy called identity shifting. Identity shifting is defined as the conscious or unconscious process of altering how one talks, behaves, one’s appearance, and perspectives. 6 An illustrative example of identity shifting is when Black women may consistently change the tone of their voice to avoid being labeled as “aggressive.” Considering the oppression Black women experience based on their race, gender, and other marginalized identities, an intersectional framework was critical to use in this study.

The theoretical framework of intersectionality is essential to the exploration of psychological factors that could promote or hinder the career advancement of individuals who belong to multiple marginalized groups, such as Black women. Psychology, as a discipline, has a history of focusing on social identities as separate, instead of overlapping constructs. An intersectional framework provides a lens for reflecting on meanings and experiences of systems of power and oppression that shape Black women’s lived experiences, such as within an academic and/or other professional workspace context. As such, race, gender, social class, sexual orientation, and other identity markers may be distinct socially constructed groupings; however, they are not independent experiences and may inform multiple combinations of oppression.7 –9 Previous research have outlined that it is essential to examine the interconnecting systems of racism and sexism among Black women and how it is interrelated with their overall mental health in the broader U.S. context and within workplaces settings in particular.10 –12 The intersectional framework allows scholars to examine how Black women in academic and other professional workspaces are confronted with the strong Black woman (SBW) stereotype, and engage in identity shifting to navigate interlocking systems of racism and sexism. The present study examines the SBW stereotype and its relationship with Black women’s intersectional experiences with gendered racial identity development. Additionally, we explore how SBW, and mental health symptomology can influence engagement in identity shifting as a coping strategy for navigating academic and other professional workspaces.

Strong Black woman

The history of the SBW stereotype has socio-political and historical roots in slavery. It was used to depict Black women as being emotionally and intellectually deficient, but physically able to endure abuse by oppressors. 13 Since the times of enslavement, the stereotype of the SBW has been internalized by numerous Black women and has been characterized by emotional restraint (or silencing), independence, and excessive caretaking of others.14 –17 While Black women’s relationship with the SBW stereotype is complicated, it has endured for generations and has evolved into a treasured identity for many. It has also served as a strategy for psychological resistance while facing daily microaggressions and oppressive interactions and environments. 18 As noted by Davis and Jones, 15 scholars are acknowledging the paradoxical nature of the image of SBW stereotype. The image of the SBW stereotype has implications that are best understood as a duality, and not a dichotomy.17,19 Shorter-Gooden and Washington 20 noted that Black women who embody the SBW may be psychologically healthier than those who do not as it has been linked to enhanced self-esteem and increased adaptability in multiple contexts. 16 However, for others, it is a stigmatized stereotype that portrays Black women as angry and aggressive. 21 In fact, Pusey 22 noted that the SBW and the angry Black woman (ABW) stereotype run concurrent with each other. The stigma of being “angry” or even “superhuman” may weigh heavily on Black women, such that some choose a façade, and others choose what they may deem as a more “authentic” self.

Consequently, the SBW and ABW stereotypes, among others, can negatively affect how Black women are perceived and treated by others in workplace settings. Scholars have found that oppressive workplace experiences (e.g., being stereotyped) may affect Black women’s careers and manifest in ways such as unfair demotion, threats of job loss, and can negatively impact their aspirations to excel in their given career path. 23 Additionally, research has shown that those who experience workplace discord are more likely to report higher levels of burnout and lower levels of organizational commitment. 24 Black women who internalize the SBW schema may suffer in silence with experiences of discrimination as they may feel pressured to meet the expectations of various roles, including roles in professional settings. 25

Unfortunately, there is limited empirical sociodemographic data available regarding the endorsement and enactment of the SBW schema. Platt and Fanning 26 noted that “to date, there is a paucity of empirical research exploring any within-group differences in the endorsement of SBW among Black women, specifically which demographic variables are predictive of SBW endorsement” (p. 63). Age differences in endorsement of SBW appear to be reported most often in the studies that provide demographic information. In the Bailey 27 study, the SBW schema was most strongly endorsed by Black women who were closer to, and over “middle age” (defined in the study as 38–59 years). The younger women in the study were hesitant to identify with the schema as strongly. These findings are in line with earlier published work on young Black women, particularly those in college, that show an overall reluctance with associating with the SBW schema as it has traditionally been defined.16,28 Conversely, a recent study 26 examining SBW endorsement and demographic characteristics among 185 Black women (over the age of 18) reported that as Black women participants aged, they were less likely to endorse the SBW schema. The authors also found that neither income, nor education, was a statistically significant predictor of SBW endorsement. While we know socioeconomic status (SES) and social positioning are important sociodemographic characteristics to explore, there are not many studies that examine the relationship with the endorsement of SBW among Black women.

Black women representing sociodemographic diversity may identify themselves as an SBW and still recognize the negative perceptions of the label. For instance, Black college women in the Nelson et al. 16 study not only identified themselves as an SBW but also acknowledged the negative stigma associated with it, as well as harmful psychological consequences. This further exemplifies the duality of the stereotype. Jones et al. 10 conducted a study with 220 Black college women (aged 18–48 years) to investigate their perceptions of the SBW stereotype, and how they believe others see the SBW label. Over 85% of participants indicated the importance of SBW in their lives even though almost half (42.65%) acknowledged that “ was the most common stigmatized perception by others. 10 Even when they were aware of the negative stigma attached to the schema, participants still indicated that being seen as an SBW was important to their identity.

SBW and mental health

Black girls and women are often socialized at an early age to be resilient in the face of oppression.29,30 Donovan and West 31 found that internalizing SBW, at some levels, for Black women was found to buffer against anxiety symptoms in the face of adversity. Although SBW is taught as a survival mechanism, it is often reinforced at the peril of one’s own emotional and psychological well-being. 15 Due to historical, and current, injustices and generational trauma experienced based on race and gender, there may be a certain level of pride that comes with being perceived as strong, resilient, and unbreakable. Embodying and portraying oneself as an SBW may often be supported and affirmed by other Black, and non-Black, men and women. However, when the SBW stereotype is celebrated, without critical examination of the toll it takes, it is replicated and transmitted repeatedly as a “badge of honor.” Those who believe that the definition of a Black woman is to persevere through whatever adversity or situation arises, no matter the price, could be at risk for negating and minimizing their mental and physical health. Recent research points to negative consequences associated with internalizing the SBW schema, especially as it relates to psychological wellness.18,32,33 Black women who identify with SBW may have difficulty starting 34 and staying in therapy due to ambivalence around acknowledging the need for help and around focusing on self-care. 35 Jones and Shorter-Gooden 36 demonstrated that upholding the SBW is also linked to depression. Abrams et al. 18 found that in a sample of 194 Black women (aged 18–82 years), those with a mid-to-high endorsement of SBW experienced greater psychological distress. Additionally, greater adherence to the SBW stereotype was found to moderate the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms.

Embodying the SBW stereotype may affect Black women’s mental health, as well as exacerbate common barriers Black women face in the workplace. Previous literature examining the experiences of Black women in professional spaces report that they face unrealistic or unfair expectations from their peers and supervisors to either “do it all” (i.e., projection of the SBW schema) or are perceived as incapable.37 –39 Carter-Sowell and Zimmerman 37 investigated factors that impact the attrition of Black women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and explained that their experiences in the workplace are often characterized by being perceived as incompetent in addition to the presence of negative stereotypes held about them (i.e., the ABW). On the other hand, some Black women in academic and other professional workplaces are perceived as successful and are thus labeled as “superwomen,” which can lead to experiencing incredibly high expectations and a burdensome workload. 38 In a case study on the well-being of Black women in STEM spaces, authors reported in all cases Black women experienced stress and mental exhaustion from the expectation to embody the SBW schema. 40 These studies illustrate the framework of intersectionality through centering how facing intangible barriers such as racism and sexism in academic and other professional workspaces can impact Black women’s expectation to align themselves with the SBW schema. For instance, Black women are expected to embody the SBW schema through racialized and gendered expectations, such as maintaining emotional resilience, putting the needs of others before their own, overachievement, and remaining silent in the face of discrimination. Thus, indicating their overall ability to persist in these spaces may be affected by how others perceive their race and gender identity.

Gendered racial identity centrality

Another factor that might influence how Black women navigate experiences of discrimination in work environments is their identity development. Though Black women have many important identities (e.g., race, gender, social class, and sexual orientation), Settles 41 argued that the distinctive experiences of U.S. Black women may lead them to be more conscious of their intersectional gendered racial identity (e.g., identification as being Black and a woman). Related research has examined identity centrality, which is the extent to which social identity is important to one’s overall self-concept. 42 Gendered racial identity centrality (GRIC) describes the significance that Black women attribute to identification being Black and a woman.43,44

Research regarding the centrality of racial and gender identities in the development of one’s professional identity may be helpful to better understand Black women’s GRIC. 45 Specifically, the buffering effects of racial centrality 46 and gender centrality 47 have at least partially mediated discrimination and microaggressive instances for Black women and girls in academic and other professional spaces. Thus, the intersection of Black women’s racial and gender identities can positively (or negatively) affect their psychological well-being and coping strategies, such as engaging in identity shifting. 41 Jones et al. 21 explored the relationship between gendered racism, identity shifting, GRIC, and mental health outcomes among young adult Black women. Results indicate that GRIC was associated with higher levels of anxiety symptoms and identity shifting among this population. 21

It is critical to further investigate the identity centrality of Black women in academic and other professional workspaces using an intersectional framework that includes their gendered racial identity. The expectation is that the centrality of their gendered racial identity possesses a comparable protective function for Black women in workplace experiences with implications for their coping strategies. Namely, by providing a buffer from discrimination, GRIC may have a positive relationship to the identity shifting behaviors Black women employ to navigate discrimination, racism, and prejudice in their workplaces. Given these intersectional perspectives, we hypothesize that greater GRIC will be associated with greater engagement in identity shifting strategies among participants. This Black womanness pride is integral for Black women’s successful navigation of academic and other professional environments, where their identities are often not affirmed, but stigmatized. Thus, their gendered racial identity development likely informs their engagement in identity shifting.

Identity shifting as a coping mechanism

As indicated previously, one coping strategy that Black women engage in to navigate different life stressors is known as identity shifting. Identity shifting is defined as the conscious and unconscious process of an individual altering how they talk, behave, their appearance, and perspective to mitigate experiences of discrimination and to build relationships.6,10,48 Pusey 22 posited that Black women can assume a “game face” in repressive situations and contexts. This game face is not an authentic representation of the self, but instead an identity shift to cope with the pressure and help alleviate the stress and adverse consequences of certain interactions and situations.

Previous research has shown that Black women who engage in identity shifting may alter how they talk or behave to avoid experiences of discrimination 6 and/or to advance socially or professionally. 49 For example, some Black women may wear their hair straight instead of wearing Afrocentric hairstyles (e.g., afro, locs) in the workplace.50,51 Research suggests that there are negative outcomes associated with shifting. More engagement in shifting strategies was associated with higher levels of depression symptoms and higher levels of anxiety among young adult Black women. 21 While research has shown the benefits and costs of shifting, more quantitative research is needed to explore the relationship between identity shifting as a coping strategy, SBW phenomenon, GRIC, and mental health outcomes among a diverse population of U.S. Black women in academic and other professional work environments. Utilizing an intersectional approach, it is possible that Black women in these spaces may engage in identity shifting strategies due to the pressures of conforming to the SBW schema, which may be associated with greater mental health outcomes.

Present study

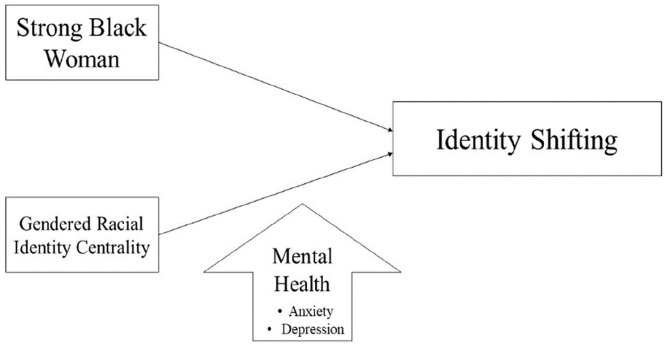

The present study uses an intersectional framework to examine the relationship between endorsement of the SBW stereotype, GRIC, and identity shifting strategies among Black women in academic and other professional settings. Additionally, the study investigates whether mental health, specifically anxiety and depression, moderates these relationships. The conceptual model is shown in Figure 1. We hypothesize the following: (1) a significant positive relationship between endorsement of the SBW stereotype, GRIC, and identity shifting such that greater endorsement of the stereotype and higher levels of identity centrality will be associated with more identity shifting coping strategies; and (2) the relationship between SBW and identity shifting is moderated by mental health such that more (a) depressive and (b) anxiety symptoms will result in a stronger relationship between stereotype endorsement and identity shifting strategies.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Method

Participants

Data for this study were collected in 2019 and 2020 as a part of a larger validation study. The sample included 289 Black/African American participants, ranging from 18 to 72 (Mage = 29.46, SD = 10.74) years of age. In terms of gender, participants primarily identified as a woman (88.6%), with one participant identifying as “non-binary” (0.3%). Most participants identified as heterosexual (74.4%), single (70.4%), Christian (51.2%), and an SBW (76.8%). With regard to education, 30.1% of participants reported having a 4-year degree, and 37.4% had an advanced degree. Of those employed in academic and other professional settings, 38.28% were at a post-secondary institution (college or university), 25% were in the private sector, and 8.59% were local, state, or federal government employees. A pre-screening survey was initially administered to all recruited participants. If participants met the study’s eligibility, they proceeded to the full online survey. All participants had to self-identify as Black/African American and a woman in the pre-screening survey; however, some participants chose not to answer the demographic questions at the end of the online survey and are captured as “Missing” (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Characteristics | N = 289 |

|---|---|

| Race, n (%) | |

| African American/Black | 221 (76.5) |

| African/Caribbean/West Indian | 8 (2.8) |

| Missing | 60 (20.8) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Woman | 256 (88.6) |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.3) |

| Missing | 32 (11.1) |

| Strong Black woman identification, n (%) | |

| Yes | 222 (76.8) |

| No | 32 (11.1) |

| Missing | 35 (12.1) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 61 (21.1) |

| Bachelor’s degree (BA, BS) | 87 (30.1) |

| Graduate/professional degree master’s degree | 108 (37.4) |

| Missing | 33 (11.4) |

| Family income, n (%) | |

| Under $30,000 | 31 (10.7) |

| $30,001 to $50,000 | 93 (32.2) |

| $50,001 to $75,000 | 45 (15.6) |

| $75,001 to $95,000 | 30 (10.4) |

| $95,001 or more | 58 (20.1) |

| Missing | 32 (11.1) |

| Sexual orientation, n (%) | |

| Heterosexual/straight | 215 (74.4) |

| Bisexual | 29 (10) |

| Lesbian/gay | 5 (1.7) |

| Queer | 3 (1) |

| Unsure | 4 (1.4) |

| Missing | 33 (11.4) |

Recruitment and procedure

Participants were sampled and recruited via Institutional Review Board-approved emails, campus flyers, and text messages to personal and professional networks, student organizations, and social media postings (e.g., Facebook). Eligibility criteria included: (1) self-identifying as an African American/Black woman; (2) 18 years and older; and is either (3) a full-time undergraduate or graduate student OR a full-time employee currently working in an academic or another workplace environment. All participants affirmed their eligibility through an initial pre-screening online survey and consent online and then completed a 30- to 40-min online survey via Qualtrics. Students were compensated $15, and non-students were given an additional $5 (e.g., $20) for participating in the study. Non-students were given additional money to enhance the recruitment of this particular sample.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire included questions about age, educational attainment, family income, sexual orientation, marital status, SBW identification question (yes or no), and religious affiliation. Based on previous literature, we chose four demographic variables as covariates. Specifically, we included age, income, educational attainment (no 4-year degree, 4-year degree, advanced degree), and self-identification as an SBW. Categorical variables were dummy coded before being entered into the analytical models.

Strong Black woman schema

To assess Black women’s awareness of the SBW schema, in which Black women should be selfless, nurturers, strong, self-reliant, and suppress their emotions, a 16-item measurement (e.g., Mammy and Superwoman subscales) from the Stereotypical Roles for Black Women Scale 52 was used. The Mammy and Superwoman subscales were combined to create the SBW subscale, as recommended in the original article. 52 Sample items include, “If I fall apart, I will be a failure,” and “I am overworked, overwhelmed, and/or underappreciated.” Participants used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), and responses were averaged together such that higher scores (scores ranging from 4 to 5) indicated greater agreement with the SBW stereotype (α = 0.82), showing good internal consistency, which is consistent with the previous research which reported α = 0.82 in a sample of Black women. 10

Gendered racial identity centrality

To assess the centrality and importance of the intersection of Black women’s racial identity and gender identity, items were adapted from the racial centrality subscale from the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity. 53 The terms “Black” and “Black people” were replaced with “Black woman” and “Black women”; otherwise, item wording was identical to the original 7-item measure, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include, “In general, being a Black woman is an important part of my self-image” and “Overall, being a Black woman has very little to do with how I feel about myself” (reversed). Responses across items were averaged together such that higher scores, scores ranging from 5 to 7, indicate higher centrality (α = 0.72) and is similar to other studies which reported Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.76 to 0.80.10,11

Identity shifting

Identity shifting was assessed using the Identity Shifting for Black Women Scale (ISBWS), 54 a 15-item scale measuring how Black women alter how they talk, their behaviors, appearance, and perspective to mitigate experiences of discrimination and to enhance intraracial relationships. Sample items include: “Due to the pressures to fit into White environments, I feel as though I can’t be myself during my professional interactions in predominantly White contexts.” and “I adapt the way I talk to enhance my social relationships in predominantly Black environments.” Scale items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses across items were averaged together such that higher scores, scores ranging from 4 to 5, indicate higher levels of shifting (α = 0.86; reporting good internal consistency) and is like the original study which had a reliability coefficient of 0.88. 54

Anxiety symptoms

To assess an individual’s self-report of anxiety symptoms, the 21-item Beck Anxiety Inventory 55 was used. Sample items include, “unable to relax” or “nervous.” Scale items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Severely-it bothered me a lot). The values for each item are summed yielding an overall or total score for all 21 symptoms that can range between 0 and 63 points. Responses were summed and higher scores (scores ranging from 26 to 63) indicate higher levels of anxiety symptoms (α = 0.89), showing good internal consistency. The original study reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92, 55 which is similar to the present study.

Depression symptoms

To assess an individual’s self-report of depression symptoms, the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory 56 was used. Sample items include “sadness,” and “pessimism.” Every question had a 4-point Likert scale of answers regarding the intensity of depression symptoms (0–3). Responses were summed for a total score of 0–63 and higher scores (scores ranging from 26 to 63) indicate higher levels of depression symptoms (α = 0.89), illustrating good internal consistency. Similarly, past research reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 in a sample of Black women. 10

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analyses included running descriptive statistics and correlation analyses in IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29). 57 Next, we investigated the constructs of interest using path analysis in a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework in Mplus 8.7. We identified 19 missing data patterns, suggesting that our data is missing at random. We opted for the default estimation procedure in Mplus—full-information maximum likelihood—to handle missing data, as it allowed for all available data to be included in our models. To answer the first research hypothesis (are the SBW stereotype and GRIC associated with identity shifting?), we regressed identity shifting on SBW, GRIC, and covariates simultaneously. To answer the second research hypothesis (does anxiety or depression moderate the links in model 1?), we first grand mean centered each variable of interest. Using an intersectional framework, we then created two new interaction terms for each moderator—one with SBW and one with GRIC. A total of four interaction terms resulted to capture interactions for both anxiety and depression. The final step was to add these interaction terms to the original model and rerun the analyses. Anxiety and depression were highly correlated, so we utilized two moderation models—one with anxiety interaction terms and one with depression interaction terms—to avoid issues of collinearity. No statistically significant interactions emerged, meaning we did not have to conduct any interaction probing.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Before investigating our research hypotheses, we examined our data and conducted preliminary analyses to explore whether relationships exist between our variables of interest. Descriptive statistics showed that participants scored high on identity shifting (M = 50.83, SD = 10.54, range 15–71), the SBW measure (M = 3.62, SD = 0.59, range 1–5), and on GRIC (M = 3.71, SD = 0.64, range 1–5). Scores were lower for both anxiety (M = 17.71, SD = 10.00, range 0–62) and depression (M = 16.14, SD = 8.98, range 0–62).

Correlation analyses revealed significant relationships between identity shifting and most of the predictors (p < 0.001 for SBW, anxiety, and depression; p = 0.08 for GRIC). In addition, anxiety was significantly associated with SBW and GRIC, and depression was significantly associated with SBW (p < 0.001 for all). Table 2 displays correlation and descriptive statistics for each variable.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations and descriptive statistics of central variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity shifting | — | ||||

| 2. Strong Black woman stereotype | 0.39** | — | |||

| 3. Gendered racial identity centrality | −0.11 | 0.10 | — | ||

| 4. Anxiety | 0.26** | 0.27** | 0.23** | — | |

| 5. Depression | 0.28** | 0.30** | −0.09 | 0.56** | — |

| M | 50.83 | 3.62 | 3.71 | 17.72 | 16.14 |

| SD | 10.54 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 10.00 | 8.98 |

| N | 289 | 264 | 263 | 260 | 265 |

SD: standard deviation.

p < 0.01.

Direct paths

For the first research hypothesis (see model 1 in Table 3), we examined the influence of the SBW stereotype and GRIC on Black women’s identity shifting strategies using path analyses in a SEM framework. The model utilized maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR), and fit statistics indicated that the model reached saturation (Comparative Fit Index = 1, c2 = 0). Our hypothesis was partially supported. Among the hypothesized predictors, significant direct effects only emerged for the SBW stereotype (b = 5.63, p < 0.001). Covariates included age, income, educational attainment, and self-identification as an SBW. Of these, we found three significant effects. Age was negatively associated with identity shifting (b = −0.30, p < 0.001), meaning that as Black women get older, they are likely to utilize fewer identity shifting strategies. In contrast, income was positively associated with identity shifting (b = 1.70, p < 0.01), which suggests that affluent Black women use identity shifting strategies more often than their economically disadvantaged counterparts. Finally, self-identification as an SBW was positively associated with identity shifting (b = 3.01, p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Direct path model and moderation models predicting identity shifting.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Strong Black woman stereotype | 0.31*** | 0.06 | 0.32*** | 0.06 | 0.30*** | 0.06 |

| Gendered racial identity centrality | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.004 | 0.06 |

| Anxiety | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | ||

| Depression | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ||

| Age | 0.31*** | 0.09 | 0.32*** | 0.09 | 0.30*** | 0.09 |

| Income | 0.22** | 0.08 | 0.22** | 0.08 | 0.21** | 0.08 |

| Education (reference: bachelor’s degree) | ||||||

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Advanced degree | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.08 |

| Views self as strong Black woman | 0.10* | 0.05 | 0.10* | 0.05 | 0.09* | 0.04 |

| Anxiety × strong Black woman stereotype | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||||

| Anxiety × gendered racial identity centrality | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||

| Depression × strong Black woman Stereotype | −0.06 | 0.07 | ||||

| Depression × gendered racial identity centrality | 0.10 | 0.06 | ||||

SE: standard error.

p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Moderation

To explore the second research hypothesis, which sought to establish whether mental health symptoms moderate the above direct paths, we created two moderation models—one for anxiety (see model 2 in Table 3) and one for depression (see model 3 in Table 3). Because the variables of interest are all continuous, we centered each predictor and moderator, then created interaction terms. As such, additional path analysis models with MLR estimation tested a total of four interactions (anxiety × SBW stereotype, anxiety × GRIC, depression × SBW stereotype, and depression × GRIC). Neither anxiety interaction term was significant (p = 0.45 for SBW, p = 0.82 for GRIC), but the depression interaction terms showed trends toward significance. When entered into a model without covariates, both depression interaction variables were statistically significant (p = 0.04 for SBW stereotype and p = 0.01 for GRIC). However, upon adding covariates into the model, the significance decreased for the SBW interaction term (p = 0.39) and for the GRIC interaction term (p = 0.10). Therefore, we conclude that potential interaction effects stemmed from one or more of the covariates, and participants with anxiety and depression do not differ from those who do not have these mental health concerns.

Discussion

The focus of this study was to examine, through an intersectional lens, the relationship between the endorsement of the SBW stereotype, GRIC, mental health symptomology, and identity shifting among Black women in academic and other professional workplace environments. It is important to recognize how the combination of racism and sexism in these spaces exact certain psychological tolls on Black women 58 and how they cope with these encounters. It is our hope that our research adds to the growing literature focusing on how embracing the SBW stereotype may influence coping mechanisms and mental health symptoms among Black women navigating academia and other workplace environments.

Our first hypothesis was partially supported. While greater endorsement of the SBW schema by Black women did result in engagement with more identity shifting strategies, the relationship between these strategies and GRIC was not significant. Those participants who highly identified with the characteristics of the SBW stereotype were more likely to utilize identity shifting strategies on campus and/or other professional workplaces. Dickens et al. 59 noted that Black women who endorse certain stigmatized stereotypes such as the SBW often recognize that they will experience hypervisibility, the feeling of being overly visible because of race and/or gender and may shift as a way to not confirm stereotypes. Upon further examination of the demographics, there was a significant negative relationship between age and endorsement of the SBW stereotype, just as in the Bailey 27 study. We posit that the younger women in the study were similar to those in the Bailey study and were hesitant to identify with the stereotype as it was traditionally understood. Younger women did not score as high as the older women on the SBW measure in the study; however, like the Jones et al. 10 study, more than three-fourths (76.8%) of all participants in the study identified as an SBW. This supports previous studies that report Black women embracing SBW and viewing it as a key component of how they see themselves.17,20,31,35,60 Additionally, this further substantiates the duality of the concept and the probable tension that Black women, of all ages, feel when they think about being an SBW. While this study did not focus on the relationship between income or SES and SBW, the authors acknowledge that more work is needed in this area. As noted by Erving et al., 61 SES or social status may nuance the endorsement, embodiment, and expectations of those who identify as an SBW. Currently, available empirical data does not demonstrate whether obtaining a higher level of education, income, or occupational status, mitigates or exacerbates the connection to SBW as an identity for Black women.

While there is pride in identifying as an SBW, there is also a price to pay. If the cultural expectation is for Black women to be strong, independent, emotional regulated, yet caretaking and selfless, even in the face of a multitude of -isms, we must be clear that it may come at a cost to their overall health. An article by Richards 62 notes that Black women face significant disparities in mental health care and are about half as likely to seek care as White women. The SBW script has profound effects on coping behaviors, and taking on the SBW persona can result in not seeking help when needed. This may be to avoid the perception of being weak, which is believed to be contradictory to an SBW. This finding suggests the importance of creating opportunities to support Black women in the workplace by offering culturally responsive programming. More resources and attention must be allocated to the myriads of challenges that Black women, and other minoritized women, face in the workplace. An example of this, in academia, is provided by Hall and Dickens63(p10) who noted that “changing the cultural landscape that has been established, supported, and transmitted throughout much of the academy, will take intentional, action-oriented strategies by those in positions of power and influence. To simply acknowledge and/or understand the barriers that Black women encounter in universities is not sufficient. There must be personal, institutional, and systemic commitment to recruitment, retention, and supporting Black women to thrive. . . .” Please note, the need to institute and support change is not just reserved for academic spaces, but all workspaces.

Although the GRIC scores were high for our sample, they were not significantly related to identity shifting. Jones et al. 10 also did not see a significant correlation; however, the relationship was positive among the Black women in their study and negative among the ones in our study. Black women who had higher GRIC were older, had higher incomes, evidenced fewer anxiety symptoms, and identified themselves as an SBW. The internalization of GRIC and SBW presents interesting fodder for discussion as it relates to coping strategies. GRIC may act as a buffer to combat the possible adverse consequences of maintaining the SBW stereotype. A Black woman whose Blackness is central to how she sees herself may be less inclined to engage in identity shifting and choose to be her “authentic self” as an act of resistance, defiance, and a form of self-care. Choosing wellness is a form of resistance because it involves guarding oneself from internalizing stereotypes and negative perceptions from others by countering the norms and expectations set forth by the organization’s work culture. 59

Black women’s GRIC scores were significantly related to anxiety symptoms, in a positive direction, but not depression symptoms. As the centrality and importance of the intersection of their racial identity and gender identity increased, so did their reported anxiety symptoms. While this finding is in line with the Jones et al. 21 study, there is variability in the outcomes of published studies that examine the influence of GRIC on mental health outcomes for Black women. Leath et al. 64 found that Black women with higher GRIC scores evidenced better mental health outcomes. Black women’s gendered racial identity beliefs play a role in shaping their self-concept, 11 and their awareness of racial and gender bias. 65 They are also multi-dimensional and require more understanding of the underlying mechanisms of GRIC as well as the contextual factors that may contribute to higher, or lower, scores on mental health variables.

Our second hypothesis was not supported. Mental health symptomology did not moderate the relationship between endorsement of SBW and identity shifting. The demographic covariates appeared to be causing the interaction effects. Research on the SBW stereotype and mental health among Black women have been heavily studied within the field of psychology 21 ; however, this literature is missing an understanding of how Black women in academic and other professional workspaces cope with the daily pressures and stress of being tokenized in these environments. This study addresses these concerns by exploring how the SBW and mental health can influence engagement in identity shifting as a coping strategy among Black women. In addition to enhancing the empirical literature, these findings have programmatic and outreach implications for recruitment, retention, and support of Black women in academia, and other professional settings. Donovan and West 31 discussed how Black women in college who endorse SBW may have difficulty acknowledging their need for assistance and support and seeking psychological assistance. They may be more prone to suffer in silence because it is what they believe they should do. Creating campaigns that normalize the importance of psychological well-being and therapy for Black women, and address the stigma attached to mental health, is one strategy in academia. A strategy for organizations is to create outreach and support programs, such as Employee Assistance Programs, that focus on both physical and psychological health and well-being. Additionally, ensuring that the programs have administrative and clinical staff who are culturally responsive to the needs and experiences of Black women.

Now more than ever, we need to be focused on psychological and emotional well-being. Castelin and White 66 noted that individual traits such as low-self compassion, self-silencing, and maladaptive perfectionism have been shown to mediate the relationship between SBW and psychological health. From an early age, Black girls and women are socialized to adopt the SBW persona, and it is reinforced and modeled within their relationships and in media. 61 There has been a growing number of stories on social media sites, including professional sites such as LinkedIn, from Black women describing their experiences with toxic academic and other professional workplace cultures. Social media post after post detail the discrimination, racism, sexism, tokenism, bullying, harassment, and burnout experienced by Black women in these spaces and call attention to the need for Black women to prioritize physical, psychological, and emotional health. This research supports the importance of unlearning what Taylor 67 notes as the mindset that says, “you don’t have time to rest.”

Strengths and limitations

This study adds to the empirical literature on the relationships between SBW, GRIC, identity shifting, and mental health. Additionally, it complements a growing body of work examining the experiences of Black women in academic and other professional spaces to increase diversity and inclusion in those fields. The limitations include a cross-sectional research design and thus, inferences about cause and effect cannot be determined. Future studies may consider utilizing a longitudinal design to explore how these variables may influence Black women’s identity shifting strategies and persistence in academic and other professional workspaces, over time. This study utilized self-reports from participants and thus, there is always the risk of receiving misinformation. One important element to explore in future studies is to identify whether participants felt tokenized, ostracized, or supported in their institutions and/or workspaces. This would have been important to assess as this is likely influential in the embodiment and performance of the SBW stereotype, as well as identity shifting as a coping strategy for dealing with the environment. Being tokenized or underrepresented in academic and other work environments can result in negative consequences 68 such as barriers to success and may manifest in negative psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression. 1 Another limitation is the absence of a power calculation for the sample prior to data analysis. Post hoc calculations demonstrated that our sample size (N = 289) had adequate power to detect a medium effect (f2 = 0.15, α = 0.05) with a model using three predictors. Although the data for this study came from a larger validation study, to ensure adequate power for subsamples, the calculation should be done a priori. Finally, the authors focused on the intersection of race and gender; however, it is acknowledged that there are multiple other important and relevant social categories such as social class, sexuality, and geography. Future studies should adopt an intersectional approach to include a more diverse range of participants to better explore these potential differences. However, that was beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusion

Overall, the importance of exploring the relationship between experiences of gendered racism and mental health among Black women in academic and other workspaces is critical. Past work exploring Black women’s use of identity shifting as a coping strategy does not include discourse on its relationship to the SBW phenomenon, GRIC, and mental health outcomes. Due to the low representation of Black women in academic and other professional spaces, Black women may experience tokenism and may feel the need to shift and uphold characteristics of the SBW stereotype, which can negatively influence their mental health. Black women may engage in emotional restraint (or silencing), in the face of experiences of workplace bullying and discrimination in academia and other work environments. Engagement in coping strategies, such as identity shifting, can take a psychological toll on Black women due to the pressures of consistently altering one’s behaviors and speech to mitigate experiences of discrimination. This research supports the need to re-imagine the SBW persona. Instead of putting the weight of the world on their shoulders, or always being strong, even in the face of adversity, let us reimagine that identifying as an SBW means knowing when and how to say “no.” This also includes taking time off to re-group when necessary, protecting one’s time and energy, and making one’s health THE priority.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all of the participants who provided us with their time and effort during this study.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Naomi M. Hall  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6009-0050

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6009-0050

Ethical consideration: The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at both Winston-Salem State University and Spelman College approved this study (IRB protocol number 6487E8).

Consent to participate: All participants affirmed their eligibility and informed consent online, prior to participating in the study. Participants were presented and read the consent form online via Qualtrics and indicated their agreement to participate by selecting an option to continue with the survey. Those who did not agree were directed to the end of the survey without completing it.

Author contributions: Naomi M. Hall: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Resources; Supervision; Project administration; Data curation.

Danielle D. Dickens: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Kelly A. Minor: Writing – original draft; Formal analysis.

Zharia Thomas: Data curation; Visualization.

Cheyane Mitchell: Data curation; Visualization.

Nailah Johnson: Data curation; Visualization.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation grant #1832141. The authors are grateful to the participants for their honesty and transparency throughout this research.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement: The authors will consider making data available to interested researchers, by request.

References

- 1. Dickens D, Jones M, Hall NM. Being a token Black female faculty member in Physics: exploring research on gendered racism, identity shifting as a coping strategy, and inclusivity in Physics. Phys Teach 2020; 58(5): 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allen AM, Wang Y, Chae DH, et al. Racial discrimination, the superwoman schema, and allostatic load: exploring an integrative stress coping model among African American women. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2019; 1: 104–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jerald MC, Cole ER, Ward LM, et al. Controlling images: low awareness of group stereotypes affects Black women’s well-being. J Couns Psychol 2017; 64(5): 487–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thomas KM, Johnson-Bailey J, Phelps RE, et al. Women of color at midcareer: going from pet to threat. In: Comas-Diaz L, Green B. (eds) The psychological health of women of color: intersections, challenges, and opportunities. Guilford Press, 2013, pp.275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asmelash L. An HBCU administrator’s suicide is raising painful questions about Black mental health. CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2024/02/27/us/hbcu-lincoln-university-missouri-suicide-questions-black-mental-health/index.html (2024).

- 6. Dickens DD, Chavez EL. Navigating the workplace: the costs and benefits of shifting identities at work among early career U.S. Black women. Sex Roles 2018; 78(11–12): 760–774. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol 2009; 64(3): 170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corneille M, Lee A, Allen S, et al. Barriers to the advancement of women of color faculty in STEM: the need for promoting equity using an intersectional framework. Equal Divers Incl 2019; 38(3): 328–348. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hogg MA, Terry DJ. The dynamic, diverse, and variable faces of organizational identity. Acad Manage Rev 2000; 25(1): 150–152. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones MK, Harris KJ, Reynolds AA. In their own words: the meaning of the Strong Black Woman schema among Black U.S. college women. Sex Roles 2021; 84: 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lewis JA, Williams MG, Peppers EJ, et al. Applying intersectionality to explore the relations between gendered racism and health among Black women. J Couns Psychol 2017; 64(5): 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ong M, Wright C, Espinosa L, et al. Inside the double bind: a synthesis of empirical research on undergraduate and graduate women of color in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Harv Educ Rev 2011; 81(2): 172–209. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collins P. Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abrams JA, Maxwell M, Pope M, et al. Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: deepening our understanding of the “Strong Black Woman” schema. Psychol Women Q 2014; 38(4): 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis SM, Jones MK. Black women at war: a comprehensive framework research on the strong Black Woman. Women’s Studies in Communication 2021; 44(3): 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nelson T, Cardemil E, Adeoye C. Rethinking strength: Black women’s perceptions of the “strong Black woman” role. Psychol Women Q 2016; 40(4): 551–563. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woods-Giscombé CL. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qual Health Res 2010; 20: 668–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abrams JA, Hill A, Maxwell M. Underneath the mask of the strong Black woman schema: disentangling influences of strength and self-silencing on depressive symptoms among US Black women. Sex Roles 2019; 80(9): 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Watson NN, Hunter CD. Anxiety and depression among African American women: the costs of strength and negative attitudes toward psychological help-seeking. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2015; 21(4): 604–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shorter-Gooden K, Washington N. Young, Black, and female: the challenge of weaving an identity. J Adolesc 1996; 19(5): 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones MS, Womack V, Jérémie-Brink G, et al. Gendered racism and mental health among young adult US Black women: the moderating roles of gendered racial identity centrality and identity shifting. Sex Roles 2021; 85: 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pusey L. Living with the mantle of the strong Black woman. Fields 2021; 7(1): 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hollis LP. Bullied out of position: Black women’s complex intersectionality, workplace bullying, and resulting career disruption. J Black Sex Relatsh 2018; 4(3): 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nielsen MB, Einarsen S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: a meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2012; 26(4): 309–332. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Geyton T, Johnson N, Ross K. ‘I’m good’: examining the internalization of the strong Black woman archetype. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 2022; 32(1): 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Platt LF, Fanning SC. The strong Black woman concept: associated demographic characteristics and perceived stress among Black women. J Black Psychol 2023; 49(1): 58–84. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bailey V. Stronger: an examination of the effects of the strong Black woman narrative through the lifespan of African American women. Master’s Thesis, Georgia State University, USA, https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/119/ (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28. West L, Donovan R, Daniel A. The price of strength: Black college women’s perspectives on the strong Black woman stereotype. Women Ther 2016; 39(3–4): 390–412. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McLaurin-Jones TL, Anderson AS, Marshall VJ, et al. Superwomen and sleep: an assessment of Black college women across the African Diaspora. Int J Behav Med 2021; 28: 130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bell EL, Nkomo SM. Armoring: leaming to withstand racial oppression. J Comp Fam Stud 1998; 29(2): 285–295. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Donovan R, West L. Stress and mental health moderating role of the strong Black woman stereotype. J Black Psychol 2015; 41(4): 384–396. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Black AR, Woods-Giscombé C. Applying the stress and ‘strength’ hypothesis to Black women’s breast cancer screening delays. Stress Health 2012; 28(5): 389–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones MK, Hill-Jarrett TG, Latimer K, et al. The role of coping in the relationship between endorsement of the Strong Black Woman schema and depressive symptoms among Black women. J Black Psychol 2021; 47(7): 578–592. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Woodward AT. Discrimination and help-seeking: use of professional services and informal support among African Americans, Black Caribbeans, and non-Hispanic Whites with a mental disorder. Race Soc Probl 2011; 3: 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Romero RE. The icon of the strong Black woman: the paradox of strength. In: Jackson LC, Greene B. (eds) Psychotherapy with African American women: innovations in psychodynamic perspectives and practice. Guilford Press, 2000, pp.225–238. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones MC, Shorter-Gooden K. Shifting: the double lives of Black women in America. Harper Collins, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carter-Sowell AR, Zimmerman CA. Hidden in plain sight: locating, validating, and advocating the stigma experiences of women of color. Sex Roles 2015; 73(9): 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thomas JO, Joseph N, Williams A, et al. Speaking truth to power: exploring the intersectional experiences of Black women in computing. In: 2018 Research on Equity and Sustained Participation in Engineering, Computing, and Technology (RESPECT). IEEE, 2018, pp.1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Williams MJ, George-Jones J, Hebl M. The face of STEM: racial phenotypic stereotypicality predicts STEM persistence by—and ability attributions about—students of color. J Pers Soc Psychol 2019; 116(3): 416–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McGee EO, Bentley L. The troubled success of Black women in STEM. Cogn Instr 2017; 35(4): 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Settles IH. Use of an intersectional framework to understand Black women’s racial and gender identities. Sex Roles 2006; 54(9–10): 589–601. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thoits PA. On merging identity theory and stress research. Soc Psychol Q 1991; 54: 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jones MK, Day SX. An exploration of Black women’s gendered racial identity using a multidimensional and intersectional approach. Sex Roles 2018; 79(1–2): 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thomas AJ, Hacker JD, Hoxha D. Gendered racial identity of Black young women. Sex Roles 2011; 64(7–8): 530–542. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith KC, Boakye B, Williams D, et al. The exploration of how identity intersectionality strengthens STEM identity for Black female undergraduates attending a Historically Black College and University. J Negro Educ 2019; 88(3): 407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Butler-Barnes ST, Leath S, Williams A, et al. Promoting resilience among African American girls: racial identity as a protective factor. Child Dev 2018; 89(6): e552–e571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Settles IH, O’Connor RC, Yap SC. Climate perceptions and identity interference among undergraduate women in STEM: the protective role of gender identity. Psychol Women Q 2016; 40(4): 488–503. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Holder A, Jackson MA, Ponterotto JG. Racial microaggression experiences and coping strategies of Black women in corporate leadership. Qual Psychol 2015; 2(2): 164–180. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hall JC, Everett JE, Hamilton-Mason J. Black women talk about workplace stress and how they cope. J Black Stud 2012; 43(2): 207–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Opie TR, Phillips KW. Hair penalties: the negative influence of Afrocentric hair on ratings of Black women’s dominance and professionalism. Front Psychol 2015; 6: 1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shih M, Young MJ, Bucher A. Working to reduce the effects of discrimination: identity management strategies in organizations. Am Psychol 2013; 68(3): 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, Speight SL. Toward the development of the stereotypic roles for Black women scale. J Black Psychol 2004; 30(3): 426–442. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sellers RM, Rowley SA, Chavous TM, et al. The Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: a preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997; 73(4): 805–815. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dickens DD, Hall NM, Watson-Singleton NN, et al. Initial construction and validation of the identity shifting for Black women scale. Psychol Women Q 2022; 46(3): 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56(6): 893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988; 8(1): 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 57. IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, Speight SL. Gendered racism, psychological distress, and coping styles of African American women. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2008; 14(4): 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dickens DD, Womack VY, Dimes T. Managing hypervisibility: an exploration of theory and research on identity shifting strategies in the workplace among Black women. J Vocat Behav 2019; 113: 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. Behind the mask of the strong Black woman: voice and the embodiment of a costly performance. Temple University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Erving CL, McKinnon II, Van Dyke ME, et al. Superwoman schema and self-rated health in Black women: is socioeconomic status a moderator? Soc Sci Med 2024; 340: 116445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Richards E. The state of mental health of Black women: clinical considerations. Psychiatr Times 2021; 38(9): 14. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hall NM, Dickens D. Celebrating and supporting Black women in physics: creating a culture of inclusivity. APS Physics Gazette Newsletter, https://aps.org/programs/women/reports/gazette/index.cfm (2020).

- 64. Leath S, Johnson K, Regis DR, et al. Gendered racial identity, positive health, and mental health among Black adult women. Emerg Adulthood. Epub ahead of print 16 January 2025. DOI: 10.1177/21676968251315202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Thomas Z, Banks J, Eaton AA, et al. 25 years of psychology research on the “strong black woman.” Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2022; 16(9): e12705. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Castelin S, White G. “I’m a strong independent Black woman”: the Strong Black Woman schema and mental health in college-aged Black women. Psychol Women Q 2022; 46(2): 196–208. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Taylor M. Stress is Killing Black women, Expert Says, https://21ninety.com/stress-is-killing-black-women (2024, accessed May 29, 2024).

- 68. Watkins MB, Simmons A, Umphress E. It’s not black and white: toward a contingency perspective on the consequences of being a token. Acad Manag Perspect 2019; 33(3): 334–365. [Google Scholar]