ABSTRACT

Aims

This study describes the factors that motivate final‐year medical students to undertake a structured experience of peer‐assisted learning (PAL) as student tutors and explores their perceptions of the relevance of teaching to their future careers.

Methods

This exploratory qualitative study involved semistructured interviews with nine final‐year medical students undertaking PAL within a formal medical education elective as part of their studies. Interviews were transcribed and analysed thematically.

Results

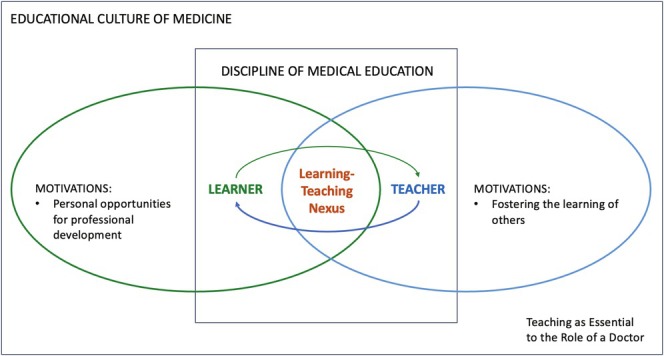

Five themes were developed during analysis. Participants' motivations to undertake PAL within a medical education elective were influenced by: (1) prior positive experiences with PAL; (2) fostering the learning of others; and (3) personal opportunities for professional development. Participants viewed (4) teaching as essential to the role of a doctor. Additionally, they expressed (5) a desire for further information about medical education career pathways. Recognising the relationships between these themes, we developed a learning‐teaching nexus conceptual framework.

Conclusion

Students' intentions to undertake PAL as student tutors as part of a medical education elective are influenced by perceived benefits to both self and others. Additionally, teaching is seen as a critical component of the role of a doctor. The learning–teaching nexus offers a framework to assist medical educators to maximally integrate opportunities for students to develop their identities as learners and teachers.

Keywords: medical education, near‐peer teaching, peer‐assisted learning

1. Introduction

Teaching is considered a core competency and part of the professional identity of medical practitioners, evidenced by its presence in medical education regulatory requirements [1, 2, 3]. Indeed, medicine relies on a strong educational culture, sustained by clinician goodwill to train its workforce. Yet, several studies highlight difficulties in recruiting and retaining sufficient clinical teachers [4, 5] despite the critical importance of successive generations participating in teaching. One strategy to address this shortage is to support medical students to develop teaching skills through peer‐assisted learning (PAL) programs.

Teaching is considered a core competency and part of the professional identity of medical practitioners.

PAL, also referred to as ‘near‐peer teaching’, can be defined as ‘people from similar social groupings who are not professional teachers helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching’. [6] PAL can take the form of leading tutorial groups, teaching practical skills and providing mentorship to new students, among other activities [7]. In this paper, we use the term ‘PAL’ to describe the pedagogical concept, and ‘near‐peer tutor’ to refer to those providing teaching in this context.

To date, literature has focused predominantly on the impacts of PAL, demonstrating benefits for both student learners [8, 9, 10, 11] and, to a lesser extent, near‐peer tutors [10, 12, 13]. PAL can enhance teaching effectiveness, create more positive learning environments, support near‐peer tutors in developing academic skills and build an educational culture [7, 14]. This provides a compelling case for medical programs to incorporate PAL initiatives into curricula. Yet, the factors that drive student involvement in such initiatives, and the extent to which students perceive these opportunities as relevant to their training, are less understood.

PAL can enhance teaching effectiveness, create more positive learning environments, support near‐peer tutors to develop academic skills, and build an educational culture [7, 14].

This study sought to address these gaps by the following: (1) describing factors that motivate final‐year medical students to become involved in PAL through a medical education elective and (2) exploring student perceptions about teaching in the context of their future medical careers.

2. Methods

This exploratory qualitative study, conducted at the University of Adelaide (UofA), was approved by the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC project number: 6218). UofA offers a 6‐year undergraduate medical program comprising ‘preclinical’ (Years 1–3) and ‘clinical’ (Years 4–6) phases. In Year 6, students undertake 4‐week placements, choosing from a range of clinical electives or a university‐based medical education elective. Students voluntarily nominate elective preferences via an enrolment process, with no direct strategies undertaken to attract students. Typically, a maximum of 12 places are available per rotation, with no minimum student number required for the elective to be offered.

The elective involves students assuming the role of near‐peer tutors for Year 1–3 students in small group, scenario‐based learning and clinical skills workshops. The elective has been offered for over 10 years and provides a structured experience where near‐peer tutors teach and/or facilitate learning alongside, and under the supervision of, academic staff. Additionally, students are supported to develop teaching and learning expertise by creating and reviewing teaching materials and delivering an oral presentation about a medical education journal article at a ‘MedEd Journal Club’. Students' teaching skills are assessed via a supervisor report and their oral presentation.

The elective involves students assuming the role of near‐peer tutors for Year 1–3 students in small group, scenario‐based learning and clinical skills workshops.

2.1. Participants

Final‐year students undertaking the elective at the time of data collection were invited to participate (August–November 2023). Students who met the selection criteria (n = 18) were contacted by AUTHOR1 via email with information about the study, prior to elective commencement. As a faculty member, AUTHOR1 may have been known to some participants in a teaching capacity. To mitigate possible conflicts of interest, AUTHOR1 was not involved in assessing elective students throughout the study.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected from individual semistructured interviews to facilitate a detailed exploration of individual perspectives. Data were collected using an interview guide developed by the authors (see Supplementary Material 1). Questions, informed by the literature and the authors' experience of medical education, were piloted prior to data collection to ensure comprehensibility and suitability to elicit responses relevant to study aims. Participants were asked to describe prior experiences of PAL, understanding of the elective and anticipated outcomes (aim 1). Additionally, participants were asked to describe the relevance of the elective to their future career and medical education as a discipline (aim 2). All interviews were informed by the core questions in the guide. Where necessary, additional prompt questions were utilised to stimulate conversation and/or provide clarity.

All interviews were conducted in‐person by AUTHOR1 between August and November 2023 and lasted approximately 30 min. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by AUTHOR1. Field notes were kept throughout. Participants received a copy of their transcript for verification to enhance fittingness and confirmability. Data were analysed using an inductive thematic approach, guided by Braun and Clarke [15]. This involved familiarisation, identification of codes and development and review of themes. Coding was primarily undertaken by AUTHOR1, with co‐coding of several transcripts at deliberate intervals. One early transcript was co‐coded by AUTHOR4 with subsequent discussion between authors to enhance credibility of the coding process. Saturation was determined through discussion among researchers, after co‐coding of two transcripts by AUTHOR2 and AUTHOR3 did not identify further themes.

2.3. Reflexivity

All researchers are full‐time medical education academics. AUTHOR1 has a background in clinical medicine and a postgraduate clinical education qualification, AUTHOR3 has a clinical background in general practice, AUTHOR2 has a background in medical research and AUTHOR4 has a background in secondary education and qualitative educational research. AUTHOR1, AUTHOR3 and AUTHOR2 are employed at UofA, contributing unique ‘insider’ perspectives. AUTHOR4 works at Flinders University and brings a relative ‘outsider’ perspective. As medical students, AUTHOR1 and AUTHOR3 completed a medical education elective during their training and now co‐coordinate the UofA elective. Consequently, each researcher brings different expertise and perspectives to the research which have informed methodological decisions and interpretations of the data.

3. Results

Nine Year 6 medical students agreed to participate in the study. In examining students' motivations to undertake PAL and the perceived relevance of the medical education elective to their future careers, five themes were developed during data analysis. Three themes guided students' motivations: (1) prior positive experiences with PAL, (2) fostering the learning of others and (3) personal opportunities for professional development. Two themes informed participants' perceptions of the relevance of teaching to their future careers: (4) teaching as essential to the role of a doctor and (5) medical education as a possible career path.

3.1. Motivations to Undertake PAL

-

1

Prior positive experiences with PAL

All participants reported positive prior PAL experiences as learners. They explained how near‐peer tutors enriched their learning, complementing the teaching provided by faculty. Near‐peer tutors supported participants' learning by providing “… tips and good ways to find information, like what good resources were, how to identify what is actually helpful” (S5). They served as role models for participants, ultimately inspiring them to undertake the medical elective themselves:

… if, say, they hadn't been there previously… I would probably approach [near‐peer tutoring] with a bit of confusion and be like, oh I don't know what this role is. And I probably wouldn't have been as … quick to be like, yeah I'll do that. (S8)

Most participants reported having discussed the elective with peers who had previously undertaken it. Peer feedback was consistently positive, with the time commitment flagged as a potential, but not insurmountable, challenge:

My friend who did it earlier had really enjoyed it. I'd heard it was a good chance to meet younger students … and reflect on your knowledge… Some people had said there were some long days … that's alright… I'm used to long days, so that wasn't really an issue. (S9)

-

2

Fostering the Learning of Others

The desire to make a positive contribution to the education of junior medical students was a key motivating factor. While this altruism stemmed from prior positive PAL experiences as a learner (Theme 1), it was also influenced by the broader educational culture. Participants were acutely aware of the contributions that others had made to their education, inspiring them to ‘give back’ the following:

I have been taught by so many great people and, therefore, I feel motivated to pass it on to the years below me. (S1)

Participants described a deliberate, purposeful intention to draw upon their own learning experiences and personal challenges in their role as a near‐peer tutor:

… as a student, I personally found some of the CBL [case‐based learning] tutors a bit daunting … another reason I wanted to be a part of this was to … be the tutor that I wanted to have … approachable … (S3)

Participants also described intended contributions to support junior students' personal and professional development, again drawing upon their own learning experiences:

I was a really, really shy first year, and my [near‐peer tutors] helped encourage me to become someone who actually became quite a good communicator, so I kind of have a soft spot for people who feel that they can't speak in a big group with loud personalities. (S2)

-

3

Personal opportunities for professional development

Participants highlighted a variety of anticipated personal development benefits from involvement in PAL. They described mutual benefits, including the opportunity to reinforce their medical knowledge while simultaneously developing teaching skills:

… I love teaching, but I also do it because it is such a nice refresher for me, and it kind of completes the circle of … teaching others but also making sure I'm up to date. (S2)

While acknowledging this benefit, some participants described a lack of confidence in their medical knowledge and expressed concern about their ability to answer questions from students. Several participants described reframing their discomfort over time, recognising it as an opportunity for growth, and becoming more comfortable with not knowing:

I'm worried about not knowing. I think that's my main fear … sometimes when students ask me, I'm like, ‘Oh yeah, I think I should know that.’ But then I don't know, so I think coming to terms with that. But I think through that, I've also developed like, sometimes it's ok to say you don't know. And I think that being able to accept that mentally has helped as well. (S3)

Beyond knowledge and teaching skill development, some participants described the experience as an opportunity to develop their professional identity:

… this rotation is also [helping me with] maturing a bit more, becoming more like a doctor. Because the younger years, and also the tutors do kind of look up to and rely on you as a senior medical student … that pushes you into the position of needing to mature a bit more, needing to act … professionally. (S3)

3.2. Relevance of Teaching to Future Career

-

4

Teaching Is essential to the Role of a Doctor

Teaching was considered integral to the doctor's professional role, recognising the broad applications of teaching: educating peers, junior doctors, medical students, patients, and the community. Some participants described medicine and teaching as inextricably linked:

I've never properly considered teaching as a separate part of my career, but I think it's so important. It's like an ingrained part of at least working in a public hospital. There are always going to be students and people below you. (S1)

This relationship between medicine and teaching was perceived as embedded in a broader educational culture within the profession. Participants considered teaching a necessary responsibility rather than an ‘optional extra’. This is related not only to others' development but also to ensuring their own medical practice remains contemporary through continuing professional development:

… if you are a doctor, you should at least have some willingness to teach and to be asked questions … because I think it makes you a better doctor … if you're keeping up to date with … new research and you are learning from your juniors … there's that kind of teaching circuit that goes around. (S2)

-

5

Medical Education as a Career Path of Interest

Participants widely reported limited awareness of medical education as a discipline and career pathway. It was evident that engagement in the elective facilitated awareness of careers in medical education:

I never really considered it as a career pathway, but I think that coming into contact with … [faculty members] … seeing these people who are in the university made me realise, like, oh yeah, medical education is a career pathway. (S3)

In addition to raising awareness about career opportunities, participants' engagement with PAL supported their orientation to the medical education discipline. One participant identified exposure to the medical education literature and community as contributing to this:

… the journal club we had, I found that actually pretty useful. I didn't realise there were so many Med Ed articles and research going on. … in the last couple of months, [faculty member] actually posted on our MyUni page inviting us to … I think it was a Med Ed conference. I think that's when I realised that oh, Med Ed is actually like a career pathway in itself. (S3)

Participants expressed a desire to learn about opportunities to incorporate education into their future careers. They suggested that information about nontraditional pathways be incorporated into their degree as follows:

I think that the nonclinical pathways, I would like to learn more about, not just med ed [sic] but, like, medicolegal things, all sorts of things like in research … and even … the CEO of the hospital, that sort of stuff. (S1)

3.3. The Learning‐Teaching Nexus

The five themes are strongly interrelated and were used to develop a conceptual model to illustrate the development of medical education capital through the learning‐teaching nexus (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The learning‐teaching nexus themes.

Central to this model is the bidirectional, complementary relationship between learning and teaching. Motivations to undertake PAL were guided by participants' occupancy of both learning and teaching roles. As learners, participants recognised opportunities to consolidate medical knowledge while developing teaching competency. As teachers, participants were driven by an altruistic desire to contribute to the learning of others. The learning‐teaching nexus is situated within a strong educational culture in medicine, highlighting the integral role of teaching. Extending on this, experiences within the learning‐teaching nexus can inspire and provoke curiosity about medical education as a discipline, creating space for further exploration as part of one's career.

Motivations to undertake PAL were guided by participants' occupancy of both learning and teaching roles.

4. Discussion

This study found that medical students' motivations to undertake PAL are informed by prior experiences with PAL and perceived benefits to junior students' learning and themselves as developing medical professionals. The opportunity to formally engage in PAL via a medical education elective provides a context to raise awareness about medical education as a discipline and possible career pathway.

The opportunity to formally engage in PAL via a medical education elective provides a context to raise awareness about medical education as a discipline and possible career pathway.

Participants recognised teaching as integral to the role of a doctor, reinforcing its status as a core competency for future practice [1, 2, 3]—a finding supported by the literature [16]. This awareness of the importance of teaching seemed to underlie participants' motivations to undertake the medical education elective.

Altruism and service are intrinsic to the role of a doctor in society. The World Medical Association's Declaration of Geneva (the ‘modern Hippocratic oath’) refers to the sharing of “… medical knowledge for the benefit of the patient and the advancement of healthcare” [17]. Given this, the finding that altruism was a key factor in participants' decision to undertake the medical education elective is unsurprising. Indeed, this finding was echoed in a study of paediatric doctors' reasons for engaging in preceptorship [18]. Collectively, these results suggest that altruistic beliefs form early and are further reinforced throughout training. Positive PAL experiences as a learner facilitated decision‐making to undertake the medical education elective. This may illustrate ‘altruism in action’, wherein senior students inspire subsequent generations who, in turn, contribute to future PAL programs. This strengthens the impetus to offer such programs alongside faculty‐led teaching.

Consistent with other literature [8, 9, 11, 13, 16], participants cited personal utility of near‐peer tutoring to consolidate learning while supporting their professional development. The relationship between professional identity formation and engagement in PAL remains underexplored, though evidence of benefits is emerging. A 2019 study identified improvements across several personal and professional competencies among near‐peer tutors participating in a PAL program [19]. More recently, another study identified strengthening of professional identity as a teacher among near‐peer tutors, increasing the capacity to manage ambiguity [16]. While uncertainty tolerance is recognised as a core competency by medical regulation bodies [20], it has been recognised as a ‘threshold concept’ because it can be troublesome to learn [21]. PAL contexts may, therefore, support students to develop and demonstrate this competency.

Participants expressed interest in learning more about medical education career pathways, with one participant extending this to nontraditional medical careers. Although research is limited, reports from Korea and Australia indicate that 12% [22] and 20% [23] of medical graduates, respectively, consider alternatives to traditional clinical careers. Nonclinical careers such as medical education can carry stigmatising perceptions [24], deterring individuals from pursuing nontraditional pathways. Challenging these perceptions could support the development of a culture wherein medical education careers are validated and valued [24]. Medical schools are well placed to craft a new narrative by exposing students to diverse opportunities to build career capital. PAL initiatives can facilitate awareness of career pathways and help change the narrative about nontraditional careers.

4.1. Limitations

This research was conducted at a single institution with a well‐established elective. Participants' views about teaching are likely to be influenced by the broader institutional culture. Additionally, the findings represent a small group of participants who opted to undertake a formal medical education elective and participate in the study. They therefore likely present the views of those with positive PAL experiences and an interest in medical education. Further research could examine the perspectives of larger, more diverse populations to ascertain the extent to which views are shared.

5. Conclusion

Final‐year medical students who opt to engage in PAL are motivated by the needs of both the individual and the collective. As learners, the experience is perceived as a valuable opportunity to consolidate medical knowledge while developing teaching competency. As teachers, the opportunity to ‘give back’ served as recognition of their own positive learning experiences as near‐peer tutees. Medical educators can harness opportunities afforded by medical education electives to facilitate students' experiences within the broader educational culture in medicine, creating space for career exploration. Initiatives such as PAL can raise awareness of medical education as a discipline and inspire future generations of medical educators.

Author Contributions

Matthew Arnold: conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, project administration, investigation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation. Andrea Dillon: conceptualization, methodology, validation, project administration, formal analysis. Christian Mingorance: writing – review and editing, methodology, conceptualization, validation, project administration, formal analysis. Svetlana King: conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing, writing – original draft, methodology, validation, formal analysis, project administration.

Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC project number: 6218).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1. Interview guide.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.

References

- 1. General Medical Council , Outcomes for Graduates (General Medical Council, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Medical Council , Standards for Assessment and Accreditation of Primary Medical Programs by the AMC (2012).

- 3. CanMEDS , Physician Competency Framework: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (2015).

- 4. Paul C. R., Vercio C., Tenney‐Soeiro R., et al., “The Decline in Community Preceptor Teaching Activity: Exploring the Perspectives of Pediatricians Who No Longer Teach Medical Students,” Academic Medicine 95 (2020): 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christner J. G., Dallaghan G. B., Briscoe G., et al., “The Community Preceptor Crisis: Recruiting and Retaining Community‐Based Faculty to Teach Medical Students‐A Shared Perspective From the Alliance for Clinical Education,” Teaching and Learning in Medicine 28 (2016): 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Topping K. J., “The Effectiveness of Peer Tutoring in Further and Higher Education: A Typology and Review of the Literature,” Higher Education 32 (1996): 321–345. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ten Cate O. and Durning S., “Peer Teaching in Medical Education: Twelve Reasons to Move From Theory to Practice,” Medical Teacher 29 (2007): 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahsin S., Abbas S., Zaidi N., Azad N., and Kaleem F., “Reciprocal Benefit to Senior and Junior Peers: An Outcome of a Pilot Research Workshop at Medical University,” Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 65 (2015): 882–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khaw C. and Raw L., “The Outcomes and Acceptability of Near‐Peer Teaching Among Medical Students in Clinical Skills,” International Journal of Medical Education 7 (2016): 188–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scicluna H. A., O'Sullivan A. J., Boyle P., Jones P. D., and McNeil H. P., “Peer Learning in the UNSW Medicine Program,” BMC Medical Education 15 (2015): 167, 10.1186/s12909-015-0450-y . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brierley C., Ellis L., and Reid E. R., “Peer‐Assisted Learning in Medical Education: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Medical Education 56 (2022): 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson A. J., Nelson S. V., Linn A. M., Raw L. E., Kildea H. B., and Tonkin A. L., “Tomorrow's Educators … Today? Implementing Near‐Peer Teaching for Medical Students,” Medical Teacher 35, no. 2 (2013): 156–159, 10.3109/0142159X.2012.737961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hall S., Harrison C. H., Stephens J., et al., “The Benefits of Being a Near‐Peer Teacher,” Clinical Teacher 15 (2018): 403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ten Cate O. and Durning S., “Dimensions and Psychology of Peer Teaching in Medical Education,” Medical Teacher 29 (2007): 546–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braun V. and Clarke V., “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2006): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kruskie M. E., Byram J. N., and Mussell J. C., “Near‐Peer Teaching Opportunities Influence Professional Identity Formation as Educators in Future Clinicians,” Medical Science Educator 33 (2023): 1515–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Medical Association . Declaration of Geneva. 1948 (adapted 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Beck Dallaghan G. L., Alerte A. M., Ryan M. S., et al., “Recruiting and Retaining Community‐Based Preceptors: A Multicenter Qualitative Action Study of Pediatric Preceptors,” Academic Medicine 92 (2017): 1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alvarez S. and Schultz J. H., “Professional and Personal Competency Development in Near‐Peer Tutors of Gross Anatomy: A Longitudinal Mixed‐Methods Study,” Anatomical Sciences Education 12 (2019): 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patel P., Hancock J., Rogers M., and Pollard S. R., “Improving Uncertainty Tolerance in Medical Students: A Scoping Review,” Medical Education 56 (2022): 1163–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collett T., Neve H., and Stephen N., “Using Audio Diaries to Identify Threshold Concepts in ‘Softer’ Disciplines: A Focus on Medical Education,” Practice and Evidence of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 12 (2017): 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim K.‐J., Park J.‐H., Lee Y.‐H., and Choi K., “What Is Different About Medical Students Interested in Non‐Clinical Careers?,” BMC Medical Education 13 (2013): 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Medical Board of Australia and AHPRA . Medical Training Survey (2022).

- 24. Church H. and Brown M. E. L., “Rise of the Med‐Ed‐ists: Achieving a Critical Mass of Non‐Practicing Clinicians Within Medical Education,” Medical Education 56 (2022): 1160–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Interview guide.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.