Abstract

Background

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form of leishmaniasis. Meglumine antimoniate is the first line of available treatment in developing countries. There is limited research on the renal effects of antimonial compounds.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old Arab male patient presented to the dermatology clinic with a 9-month history of multiple skin lesions. The patient had a history of end-stage renal failure. Physical examination of these lesions revealed ulcerated nodules that are painless and non-itchy located on the hands, forearms, feet, and neck. The lesions were diagnosed as cutaneous leishmaniasis tropica on the basis of the histopathology of a skin biopsy and the patient’s region, which is endemic to female sandflies and this specific subtype cutaneous leishmaniasis. The patient started taking meglumine antimoniate intramuscular administration after the dialysis session at a dose of 750 mg. The lesions showed partial to complete remission after 60 days of treatment without any meglumine antimoniate side effects. The patient has not experienced any relapse of leishmaniasis since kidney transplantation 6 years ago.

Conclusion

This case highlights knowledge gaps in the therapeutic approach for using meglumine antimoniate in patients with end-stage renal failure undergoing hemodialysis. The need for further research and clinical trials to establish clear guidelines is essential.

Keywords: Cutaneous leishmaniasis, Meglumine antimoniate, Renal failure, Dialysis, Dermatology

Background

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), the most common form of leishmaniasis, is caused by protozoan parasites transmitted through the bite of infected female phlebotomine sandflies, leading to a major health problem in developing countries [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization, 85% of the global CL incidence occurs in eight countries: Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Algeria, Brazil, Colombia, and Peru [3]. Leishmaniasis occurs as a non-itchy and painless sore at the site of the bite, and can heal without scars on the skin [2, 3]. Meglumine antimoniate (MA) is the first line of available treatment in developing countries such as Syria [1]. This case describes the successful treatment of CL using MA in a patient with end-stage renal failure undergoing hemodialysis before kidney transplantation. This case is described in accordance with the criteria of CARE.

Case presentation

On 12th June 2017, a 25-year-old male presented to the dermatology clinic with a nine-month history of multiple skin lesions. multiple skin lesions nine months ago of that time. The patient had a history of end-stage renal failure due to untreated hypertension and used to undergo dialysis three times a week two years ago, after that had decided to perform a kidney transplantation. Physical examination of these lesions revealed ulcerated nodules that are painless and non-itchy, located on the hands, forearms, feet, and neck (Fig. 1). The lesions were diagnosed as cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) tropica based on the histopathology of a skin biopsy (Fig. 2) and the patient’s region, which is endemic to female sandflies and this specific subtype of CL. The lesions should be treated before the kidney transplantation procedure and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. The patient started taking meglumine antimoniate (MA) intramuscular administration after the dialysis session at a dose of 750 mg (the standard dose of MA is 75 mg/kg/day), with ongoing follow-up due to the absence of anti-Leishmanial drugs (such as liposomal amphotericin B) in our country that are safe for patients with renal failure. The lesions showed partial to complete remission after 60 days of treatment without any MA side effects with no observed side effects from MA (Fig. 3). After that, the patient started to undergo commenced kidney transplantation protocol. Eventually, the patient has not experienced any relapse of Leishmaniasis since undergoing kidney transplantation until the year 2023 in November 2017 until the present day. The renal function of the patient was normal post-transplantation, and he is currently living in good conditions (Fig. 4). Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Fig. 1.

Patient’s pictures revealing multiple skin lesions located on the hands (A, B, C, G), forearms (F, H, I), feet (D), and neck (E) at the time of clinic presentation

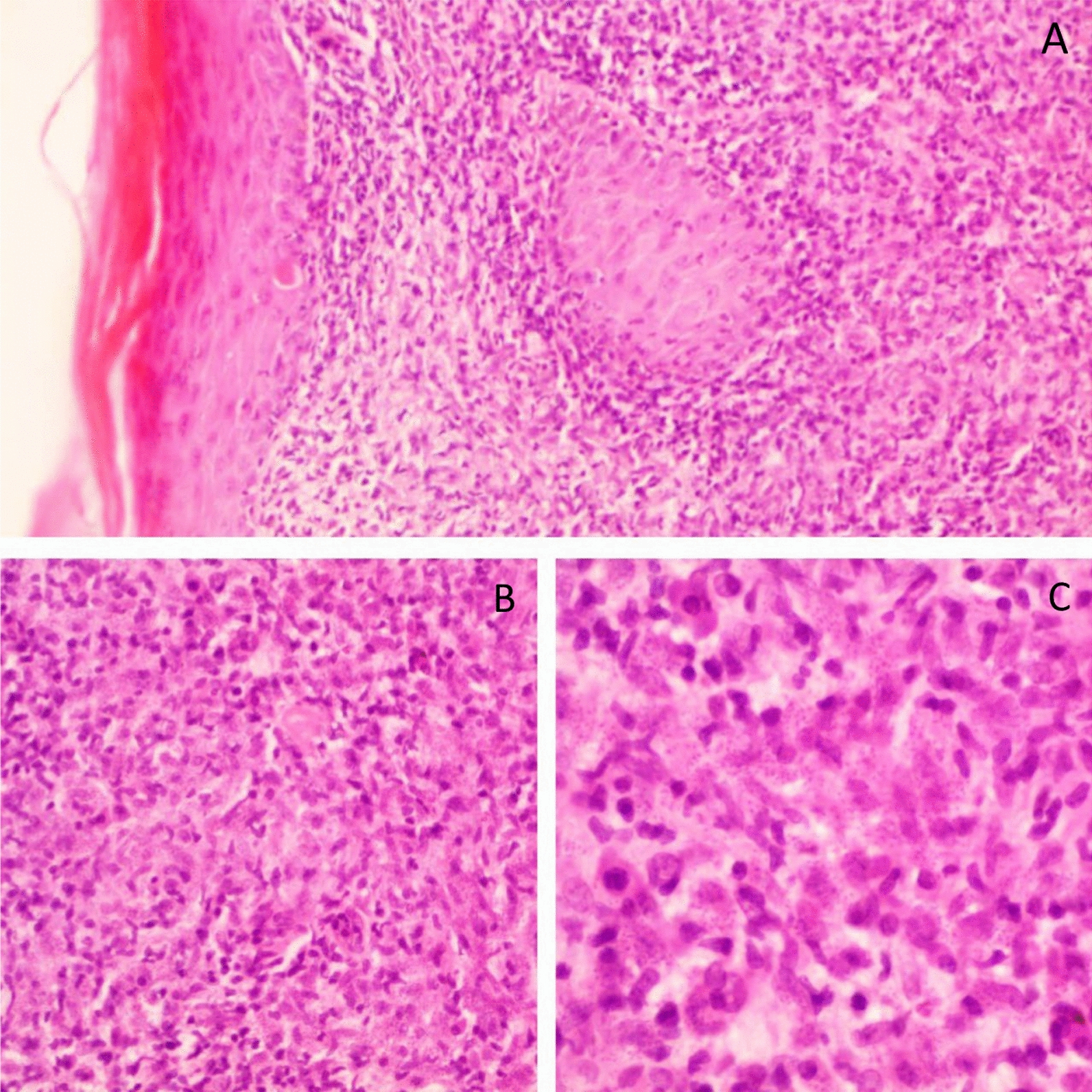

Fig. 2.

Histopathology of the skin biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin staining showing an ill-defined granuloma with multinucleated giant cells, diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and leishmania amastigotes within macrophages. Findings were observed under the following settings: (A) 4 × 0.1, (B) 10 × 0.25, (C) 40 × 0.65

Fig. 3.

Additional pictures of patient after 60 days of meglumine antimoniate intramuscular administration, revealing partial to complete remission of CL. Images (A, B, D, E) show partial to complete remission of CL on the forearms, while images (C, G, H) show partial to complete remission of CL on the hands. Image (F) shows partial to complete remission of CL on the neck

Fig. 4.

Patient pictures after kidney transplantation in 2023, revealing complete remission from CL without any relapse. Images (A, B, E) show complete remission from CL on the hand, while images (C, D, F) show complete remission from CL on the forearm

Discussion

CL is caused by a parasite from the genus Leishmania infection and is transmitted to humans by (female) sand flies bite [4]. MA, marketed as Glucantime, is currently the most effective treatment for CL, particularly in underdeveloped countries [1]. However, MA is associated with several adverse effects, primarily related to cumulative dosing. The most serious of these include cardiotoxicity and clinical pancreatitis, while less severe side effects may involve myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and elevated liver function tests [5]. However, there is limited research on the renal effects of antimonial compounds [5]. Approximately 80% of Glucantime is excreted through the kidneys in its active form, which imposes strict limitations on its use in patients with reduced renal clearance [5]. In this report, we detail the successful treatment of MA in a patient with end-stage renal failure (ESRF) undergoing hemodialysis, which presents unique challenges due to the drug’s renal clearance profile and potential for severe side effects. Importantly, there is a lack of data regarding the efficacy and safety of MA, specifically in hemodialysis patients, as most existing studies focus on other populations. One study suggests that alternative treatments such as liposomal amphotericin B are preferred due to their lower nephrotoxicity and safer administration profiles [5], However, given the unavailability of these alternatives in our region and the established efficacy of MA for CL, we opted to use MA with careful monitoring. In cases of refractory mucosal leishmaniasis, pentamidine has been used, but it may also cause temporary worsening of renal function [6]. The unavailability of these alternatives in our region necessitated the use of MA with close monitoring. Our patient received an intramuscular dose of 750 mg of Glucantime, which corresponds to half an ampoule, administered post-dialysis. (The recommended dose of Glucantime is 75 mg/kg/day.) We chose this lower experimental dose due to the patient’s suspended renal clearance and the absence of established treatment protocols for MA in patients with ESRF. Remarkably, after 60 days of treatment, the lesions showed partial to complete remission without any reported side effects from MA. Among the different mechanisms of action of antimonials, a prominent dual action against CL infection is observed: firstly, antimonials activate the macrophages to eliminate the infected parasites; and secondly, they inhibit trypanothione reductase, ultimately leading to parasite elimination. Accumulating evidence indicates that antimonials increase the expression of aquaglyceroporin (AQP1) and inhibit DNA topoisomerase, glycolysis pathways, ATP/GTP synthesis, and glucose metabolism, resulting in decrease viability of Leishmania parasites [7]. Different clinical trials have assessed the efficacy of intralesional antimonials, reporting healing rates between 56% and 93% [8]. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) recommends intralesional treatment for patients with single lesions who cannot tolerate systemic therapy due to conditions such as kidney or heart disease [9]. Alternative therapies—including cryotherapy, carbon dioxide laser treatment, thermotherapy, paromomycin cream, and zinc sulfate injections—have shown variable success rates [10]. However, the large number of lesions in our patient complicated the use of intralesional treatments and other treatment options. One previous case report described a patient with chronic renal failure who experienced severe complications, including cardiotoxicity, acute pancreatitis, and cardiogenic shock after receiving intravenous MA. This underscores the potential dangers of elevated plasma levels of the drug due to impaired renal clearance [5].

Conclusion

This case is significant as it highlights knowledge gaps in the therapeutic approach for using MA in patients with ESRF undergoing hemodialysis. Although this case suggests the possibility of successful MA treatment in this population, further investigation is crucial to understand optimal dosing, administration routes, and potential complications.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- CL

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

- MA

Meglumine antimoniate

- ESRF

End-stage renal failure

Author contributions

Hazem Arab: conceptualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review & editing. Yousef Alsaffaf: data curation, writing—original draft, and writing—review & editing. Ahmed Aldolly: writing—original draft and writing—review & editing. Abdullah Dukhan: writing—original draft. Thaer Douri: supervision, investigation, and writing—review & editing.

Funding

No funding applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable (this manuscript does not report data generation or analysis).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our institution (Hama University) does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series. Our study is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and CARE guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from the participant included in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: an error was identified in the Case presentation section as it was incomplete in addition the Abstract Case presentation section should read 750 mg without per week indication.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/19/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s13256-025-05490-x

References

- 1.Rahman A, Tahir M, Naveed T, et al. Comparison of meglumine antimoniate and miltefosine in cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2023;33(12):1367–71. 10.29271/jcpsp.2023.12.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scorza BM, Carvalho EM, Wilson ME. Cutaneous manifestations of human and murine leishmaniasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1296. 10.3390/ijms18061296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rooholamini Z, Dianat-Moghadam H, Esmaeilifallah M, Khanahmad H. From classical approaches to new developments in genetic engineering of live attenuated vaccine against cutaneous leishmaniasis: potential and immunization. Front Public Health. 2024;5(12):1382996. 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1382996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortazavi H, Salehi M, Kamyab K. Reactivation of cutaneous leishmaniasis after renal transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014: 251423. 10.1155/2014/251423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marques SA, Merlotto MR, Ramos PM, Marques MEA. American tegumentary leishmaniasis: severe side effects of pentavalent antimonial in a patient with chronic renal failure. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(3):355–7. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petruccelli KC, Couceiro KN, Guerra MDGVB, et al. Treatment of tegumentary leishmaniasis in two hemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease using two series of pentamidine. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2021;54:633–720. 10.1590/0037-8682-0633-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madusanka RK, Silva H, Karunaweera ND. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis and insights into species-specific responses: a narrative review. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11(2):695–711. 10.1007/s40121-022-00602-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rojas Cabrera E, Verduguez-Orellana A, Tordoya-Titichoca IJ, et al. Intralesional meglumine antimoniate: safe, feasible and effective therapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Bolivia. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(10):286. 10.3390/tropicalmed7100286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan American Health Organization. Guideline for the treatment of leishmaniasis in the Americas. Second edition. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. 10.37774/9789275125038.

- 10.Bashir U, Tahir M, Anwar MI, Manzoor F. Comparison of intralesional meglumine antimonite along with oral itraconazole to intralesional meglumine antimonite in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(6):1669–73. 10.12669/pjms.35.6.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable (this manuscript does not report data generation or analysis).