Abstract

Abstract

The Na+ (or H+)-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (also called RNF, rhodobacter nitrogen fixation, complex) catalyzes the oxidation of reduced ferredoxin with NAD+, hereby generating an electrochemical gradient. In the reverse reaction driven by an electrochemical gradient, RNF provides reduced ferredoxin using NADH as electron donor. RNF plays a crucial role in the metabolism of many anaerobes, such as amino acid fermenters, acetogens, or aceticlastic methanogens. The Na+-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (NQR), which has evolved from an RNF, is found in selected bacterial groups including anaerobic, marine, or pathogenic organisms. Since NQR and RNF are not related to eukaryotic respiratory complex I (NADH:quinone oxidoreductase), members of this oxidoreductase family are promising targets for novel antibiotics. RNF and NQR share a membrane-bound core complex consisting of four subunits, which represent an essential functional module for redox-driven cation transport. Several recent 3D structures of RNF and NQR in different states put forward conformational coupling of electron transfer and Na+ translocation reaction steps. Based on this common principle, putative reaction mechanisms of RNF and NQR redox pumps are compared.

Key points

• Electrogenic ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductases (RNF complexes) are found in bacteria and archaea.

• The Na+ -translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (NQR) is evolutionary related to RNF.

• The mechanism of energy conversion by RNF/NQR complexes is based on conformational coupling of electron transfer and cation transport reactions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00253-025-13531-0.

Keywords: Electron transport, Respiration, Electrochemical proton gradient, Electrochemical sodium gradient, RNF, NQR

Introduction

In most chemotrophic microorganisms, the endergonic synthesis of ATP is inevitably linked to the oxidation of a substrate and reduction of an acceptor molecule. The continuous re-oxidation of this acceptor is crucial to maintain ATP synthesis and ultimately requires excretion of fermentation products as in substrate level phosphorylation, or utilization of exogenous electron acceptors as in oxidative phosphorylation. In both scenarios, cellular electron carriers such as NADH/NAD+ and reduced/oxidized ferredoxin (Fd) play an important role. Both carriers act as substrates for the membrane-bound RNF complex (rhodobacter nitrogen fixation complex, also termed NFO, NAD+:ferredoxin oxidoreductase complex). The name RNF was based on the finding that the six genes rnfABCDE were essential for N2 fixation in Rhodobacter capsulatus (Schmehl et al. 1993). The authors proposed that these genes encode subunits of a membrane-bound electron transfer complex, which provides low-potential electrons in the form of reduced ferredoxin for the reduction of N2 by nitrogenase. This function of RNF was also confirmed in other N2 fixing bacteria such as Azotobacter vinelandii (Martin Del Campo et al. 2022). Here, RNF exploits the proton motive force (pmf) of the bacterial membrane to push electrons from NADH to the lower-potential ferredoxin, operating in the so-called reverse electron transfer mode. RNF complexes from amino acid-fermenting bacteria (Brüggemann et al. 2003; Boiangiu et al. 2005; Vitt et al. 2022) and the related Na+-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (NQR) (Hau et al. 2023) preferably operate in the so-called forward electron transfer mode, coupling the electron transfer from a low-potential to a high-potential substrate to the transport of Na+ from the cytoplasm to the periplasm under formation of an electrochemical Na+ gradient (ΔµNa+). Depending on the growth substrates, the RNF in acetogenic bacteria is crucial for establishing ΔµNa+ (forward electron transfer mode), or for the formation of reduced ferredoxin from NADH driven by ΔµNa+ (reverse electron transfer mode) (Schuchmann and Müller 2016; Westphal et al. 2018). RNF represents an important metabolic oxidoreductase as it links the redox reactions between NADH/NAD+ and ferredoxinox/red to the formation or utilization of electrochemical Na+ or H+ gradients. In these different roles, it is widespread in the bacterial kingdom and also present in certain archaeal lineages (Hess et al. 2016). In marked contrast to RNF, the NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (NQR) is found only in some bacterial groups. An ancient RNF represents the ancestor of NQR, which first appeared in the Bacteroidetes (Munoz et al. 2020). A comparison of the six Nqr subunits with the six Rnf subunits reveals a conserved core of four membrane-bound subunits (RnfD/NqrB, RnfG/NqrC, RnfE/NqrD, RnfA/NqrE) (Table 1). This suggests that the mechanism of redox-driven cation translocation across the membrane is shared between RNF and NQR. In RNF and the related NQR, we find both Na+ and H+ dependent complexes.

Table 1.

Comparison of subunits of RNF and NQR complexes

| NQR V. cholerae | RNF C. tetanomorphum | RNF1 A. vinelandii | RNF A. woodii |

| Hau et al. (2023) | Vitt et al. (2022) | Zhang and Einsle (2024) | Kumar et al. (2025) |

| PDB code 8 A1U | PDB code 7ZC6 | PDB code 8 AHX | PDB code 9ERK |

| Subunit | Subunit | Subunit | |

| Cofactors | Cofactors | Cofactors | |

| RMSD (to corresponding NQR subunit) | RMSD (to corresponding NQR subunit) | RMSD (to corresponding NQR subunit) | |

| Sequence identity (with corresponding NQR subunit) | Sequence identity (with corresponding NQR subunit) | Sequence identity (with corresponding NQR subunit) | |

| NqrA | RnfC | RnfC | RnfC |

| No cofactor | 1 FMN | 1 FMN | 1 FMN |

| 2 [4Fe-4S] | 2 [4Fe-4S] | 2 [4Fe-4S] | |

| 4.05 Å (403 C,α 93% of all) | 4.02 Å (404 Cα, 85% of all) | 4.14 Å (404 Cα, 91% of all) | |

| 17.7% (403 residues) | 13.9% (404 residues) | 15.6% (404 residues) | |

| NqrB | RnfD | RnfD | RnfD |

| 1 riboflavin | 1 riboflavin | 1 riboflavin | 1 riboflavin |

| 1 covalent FMN | 1 covalent FMN | 1 covalent FMN | 1 covalent FMN |

| 1 ubiquinone | 1.47 Å (271 Cα, 89% of all) | 1.46Å (288 C 83% of all) | 1.38 Å (275 C 86% of all) |

| 35.0% (271 residues) | 28.8% (288 residues) | 34.2% (275 residues) | |

| NqrC | RnfG | RnfG | RnfG |

| 1 covalent FMN | 1 covalent FMN | 1 covalent FMN | 1 covalent FMN |

| 2.82 Å (183 Cα, 98% of all) | 3.33 Å (191 Cα, 97% of all) | 3.26 Å (190 C, 92% of all) | |

| 19.1% (183 residues) | 16.2% (191 residues) | 16.8% (190 residues) | |

| NqrD | RnfE | RnfE | RnfE |

| 1 [2Fe-2S] (between NqrD/E) | 1 [2Fe-2S] (between RnfA/E) | 1 [2Fe-2S] (between RnfA/E) | 1 [2Fe-2S] (between RnfA/E) |

| 1.48 Å (190 Cα, 98% of all) | 1.89 Å (195 Caα, 91% of all) | 1.57 Å (193 Cα, 98% of all) | |

| 37.9% (190 residues) | 34.9% (195 residues) | 37.8% (193 residues) | |

| NqrE | RnfA | RnfA | RnfA |

| 2.16 Å (187 Cα, 98% of all) | 1.16 Å (189 Cα, 100% of all) | 2.05 Å (188 Cα, 98% of all) | |

| 39.0% (187 residues) | 38.6% (189 residues) | 43.1% (193 residues) | |

| - | RnfB | RnfB | RnfB |

| 5 [4Fe-4S] | 2 [4Fe-4S] | 7 [4Fe-4S] | |

| 1 [4Fe-4S] in flexible domain | 1 [4Fe-4S] in flexible domain | 1 [4Fe-4S] in flexible domain | |

| NqrF | - | - | - |

| 1 FAD | |||

| 1 [2 Fe-2S] | |||

| 1 NADH | |||

| - | - | RnfH | - |

| No cofactor |

No homologous subunit in other complexes

Structural alignments were prepared with TM-align (Zhang 2005)

Ultimately, the question is whether ancient ATP synthases were driven by an electrochemical Na+ or proton gradient. Studying the evolution of F-type versus V-type ATP synthases and considering Na+ or H+ specificities of the enzymes as predicted from sequence comparisons, Galperin and colleagues argue that Na+-specific ATP synthases predated H+-dependent enzymes and propose that ancestral membrane bioenergetics used Na+ (Mulkidjanian et al. 2008). This is in contrast to a hydrothermal vent scenario of the origin of life where the energy metabolism of early cells is powered by existing pH gradients (outside acidic) (Lane 2020), and primordial, energy-converting protein complexes are proposed to be proton-dependent. While the question of cation specificity of primordial pumps is not easily settled, it seems very plausible that an ATP synthase operating together with RNF represents an ancient chemiosmotic system, which still prevails in the metabolism of many bacteria and archaea (Marreiros et al. 2016). In an elegant series of experiments using the purified complexes from Thermotoga maritima co-reconstituted in proteoliposomes, it was shown that the electrochemical Na+ gradient established by RNF drives synthesis of ATP by the Na+-dependent F1FO ATP synthase (Kuhns et al. 2020b).

Here we describe the functions of selected RNF and NQR complexes, considering their role in metabolism and energy conservation in selected microorganisms. Recent findings on the structure and function of RNF and NQR are summarized. A comparative, structural analysis of both complexes reveals a highly conserved, membrane-bound core complex composed of four subunits, which interacts with different electron input and electron output modules. Considering both structural and functional studies, conformational coupling of electron transfer and cation transport processes is identified as the common mechanistic principle of the RNF/NQR oxidoreductase family.

Physiological functions of selected RNF and NQR complexes

RNF of Clostridium tetani and C. tetanomorphum: energy conservation during the fermentation of glutamate

The genome analysis of C. tetani revealed that this pathogenic bacterium possesses an RNF complex (Brüggemann et al. 2003). The related bacterium C. tetanomorphum has a rather high content of RNF (Boiangiu et al. 2005), which facilitated purification and subsequent structural analysis of the complex (Vitt et al. 2022). C. tetani and C. tetanomorphum ferment glutamate via (S,S)−3-methylaspartate according to the following Eq. (1):

| 1 |

(ΔG°′ = − 314 kJ).

The proposed pathway starts with the conversion of 5 (S)-glutamate to 5 ammonia, 5 acetate, and 5 pyruvate (Buckel and Thauer 2013). The pyruvates are oxidized to 5 CO2 and 5 acetyl-CoA, whereby 10 ferredoxins are reduced. From 3 acetyl-CoA, 3 ATP are synthesized via substrate level phosphorylation. Additional 4 ferredoxins are reduced via electron bifurcation during butyrate synthesis from 2 acetyl-CoA, 2 acetate, and 6 NADH. H2 production requires 2 reduced ferredoxins. In total, 12 reduced ferredoxins are formed serving as electron donors for RNF, which reduces 6 NAD+ to generate 6 NADH under translocation of 12 Na+. Since 5 Na+ are probably required for the uptake of 5 glutamates, 7 Na+ remain for the chemiosmotic synthesis of about 1.75 ATP. Together with the 3 ATP obtained from acetyl-CoA, 4.75 ATP are obtained from 5 glutamate (approximately 1 ATP/glutamate); see also (Buckel 2021).

RNF of Acetobacterium woodii: energy conservation during reduction of CO2 to acetate

RNF represents an important oxidoreductase for energy conservation in A. woodii, which reversibly couples the oxidation of reduced ferredoxin and reduction of NAD+ to the translocation of Na+ (Hess et al. 2013; Schuchmann and Müller 2014, 2016; Westphal et al. 2018). Recently, the structure of A. woodii RNF was reported (Kumar et al. 2025). A. woodii synthesizes acetate from H2 and CO2 using the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (Ragsdale and Pierce 2008) according to the following Eq. (2):

| 2 |

The first step of the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is the production of formate catalyzed by the hydrogen dependent CO2 reductase (Eq. 3):

| 3 |

For the next steps reduced ferredoxin (Fdˉ) and NADH are required, which are provided by a bifurcating hydrogenase (Schuchmann and Müller 2012) (Eq. 4). This oxidoreductase catalyzes two one-electron transfers from H2 (E°′ = − 414 mV), one to the high potential NAD+ (E°′ = − 320 mV) which drives the other electron to the low potential ferredoxin (Fd, E°′ = − 420 to − 450 mV).

| 4 |

The carbon metabolism proceeds by formylation of tetrahydrofolate (THF) to N5-formyl-THF, which requires ATP hydrolysis. The product cyclizes to N5-N10-methenyl-THF, which is reduced with 2 NADH via N5,N10-methylene-THF to N10-methyl-THF. The methyl group is transferred to a corrinoid-Fe-S protein and combined with CO and CoASH to afford acetyl-CoA, from which acetate and ATP are synthesized. CO is obtained by reduction of CO2 with 2 Fdˉ. The biochemistry of acetogenesis is reviewed in (Ragsdale 2008). The overall reaction is summarized in Eq. (5):

| 5 |

The bifurcating hydrogenase reduces 4 Fd and 2 NAD+ with 4 H2. 3 Fdˉ are consumed during acetate synthesis, a fourth Fdˉ reduces 0.5 NAD+ catalyzed by RNF whereby 1 Na+ is transported across the membrane and then used for the chemiosmotic synthesis of about 0.3–0.4 ATP. Since one ATP is consumed by formylation of THF and one ATP is generated via acetyl-CoA, ΔµNa+ produced by RNF is crucial for energy conservation (Schuchmann and Müller 2014).

RNF of Azotobacter vinelandii: the power supply for biological nitrogen fixation

Biological nitrogen fixation performed by diazotrophic bacteria requires large amounts of energy in the form of 16 ATP and 8 low potential electrons to overcome the high activation barrier for cleavage of the dinitrogen triple bond by the enzyme nitrogenase (Einsle 2023). Nitrogenase of the model diazotroph A. vinelandii operates at a redox potential of − 0.62 V, thus the redox potential of NADH is not sufficiently low for N2 fixation. In A. vinelandii, ferredoxin or flavodoxin therefore act as electron donor. While reduced flavodoxin is provided by the electron-bifurcating Fix system (reviewed in (Barney 2020)) ferredoxin is reduced by RNF that uses the proton motive force and NADH as electron donor in a reverse electron transfer reaction. A. vinelandii contains two rnf gene clusters coding for RNF1 and RNF2. RNF1 is the primary electron source for nitrogenase and the rnf1 gene cluster is expressed under nitrogen fixating (nif) conditions (Barney and Plunkett 2022), while the rnf2 gene cluster is expressed independently of a nitrogen source (Curatti et al. 2005). Recently, Zhang and Einsle (2024) have reported the structure of A. vinelandii RNF1. Compared to other structurally characterized RNF complexes (Vitt et al. 2022; Kumar et al. 2025), the A. vinelandii RNF shows some differences, in particular, an additional, cytoplasmic subunit RnfH that does not contain a redox cofactor. These differences in RNF of A. vinelandii RNF might be crucial to promote reduction of ferredoxin in the reverse electron transfer mode driven by the electrochemical proton gradient (Zhang and Einsle 2024). This proton motive force is generated by aerobic respiration providing a large surplus of ATP (Alleman et al. 2021).

RSX of Escherichia coli: protection against superoxide and nitric oxide

The RsxABCDGE complex (RSX) is a homologue of the RnfABCDGE complex (RNF) and is supposed to act as NAD(P)H-dependent reducing system of the oxidized form of the transcriptional regulator SoxR, as shown for E. coli (Lee et al. 2022). SoxR is a small [2Fe-2S] cluster containing protein that binds to DNA (Ding et al. 1996). Oxidative stress by reactive oxygen species or nitric oxide leads to the oxidation of the [2Fe-2S] cluster from the reduced form [Fe(II)-Fe(III)] to the all-ferric form [Fe(III)-Fe(III)] thereby activating SoxR. SoxR in the oxidized active state initiates the transcription of the downstream regulator soxS, which in turn activates the expression of the stress regulon. Among the activated genes is rsxABCDGE, rseC and interestingly apbE. After the oxidative stress is relieved, the SoxR is inactivated by reduction through RsxABCDGE together with RseC (Lee et al. 2022). ApbE is a flavin transferase (Bertsova et al. 2013) that catalyzes the covalent attachment of FMN to Thr residues recognizing a specific sequence motif. Such a motif is present in RsxD (homologous to RnfD or NqrB) and RsxG (homologous to RnfG or NqrC). The reduction potential of free SoxR has been determined as − 285 mV, above of that of ferredoxin (− 420 mV) and NAD+ (− 320 mV) (Ding et al. 1996). The question arises, why the cell uses RSX and a ΔµNa+/H+ to reduce ferredoxin and subsequently SoxR, while the potential of NADH would be sufficient to reduce SoxR.

RNF of archaea: aceticlastic methanogenesis in Methanosarcina acetivorans

The M. acetivorans RNF comprises, besides the six subunits RnfABCDGE, an additional multiheme c-type cytochrome, which is expected to facilitate electron transfer to methanophenazine or extracellular electron acceptors (Gupta et al. 2024). M. acetivorans critically relies on this Na+-translocating RNF (Schlegel et al. 2012b) to provide reduced methanophenazine for the final reduction step in methanogenesis, the reduction of the heterodisulfide CoM-S–S-CoB to CoM-SH and CoB-SH catalyzed by HdrED (heterodisulfide reductase) (Suharti et al. 2014; Ferry 2020). With the help of ATP, acetate is activated to acetyl-CoA, which in the presence of tetrahydrosarcinapterin is cleaved to CO, CoA, and methyl-tetrahydrosarcinapterin. Reduced ferredoxin, generated by the action of CO with carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, acts as electron donor for the Na+-translocating RNF (Schlegel et al. 2012b). Methyl-tetrahydrosarcinapterin reacts with CoM-SH to tetrahydrosarcinapterin and methyl-S-CoM, whereby the energy of the methyl-transfer from N to S is used to generate an electrochemical Na+ gradient (Becher et al. 1992; Lienard et al. 1996). Subsequently, methyl-S-CoM and the electron donor CoB-SH are converted to methane and the heterodisulfide CoM-S–S-CoB. The chemiosmotic potential generated by RNF and other primary pumps is used to drive ATP synthesis by the A1AO ATP synthase, which may use Na+ and H+ as coupling cation (Schlegel et al. 2012a). However, the reported stoichiometries of Na+ translocated by RNF are not sufficient to provide the energy required (Schlegel et al. 2012b). Further studies indicate that also energy conservation by means of electron bifurcation is important for survival of M. acetivorans in native environments (Prakash et al. 2019; Song et al. 2023).

NQR of Vibrio cholerae: the redox Na+ pump of a human pathogen

The Na+-translocating NQR was first discovered in marine Vibrio species (Unemoto et al. 1977) and was later found in many bacterial groups (Reyes-Prieto et al. 2014; Munoz et al. 2020; Sampaio et al. 2022). It operates in the forward mode and uses NADH as electron donor and ubiquinone as electron acceptor. Like RNF, it is composed of six subunits termed NqrABCDEF. In many pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera disease, NQR contributes to the virulence of the pathogen (Dibrov et al. 2017; Steuber and Fritz 2024). While the V. cholerae NQR is a Na+ pump (Toulouse et al. 2017), NQR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa transports H+ rather than Na+ (Raba et al. 2018). The central role of NQR in the energy metabolism of many pathogens, in particular of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Acinetobacter baumannii defines it as a possible target for new antibacterial drugs. NQR is also found in strict anaerobes such as Segatella bryantii. Here, NQR reduces menaquinone to menaquinol, which acts as electron donor for the reduction of fumarate (Schleicher et al. 2021; Hau et al. 2024).

NQR has evolved from RNF

The structural similarity of the core subunits of RNF and NQR outlined here corroborates that NQR has evolved from RNF (reviewed in (Biegel et al. 2011)). During evolution a duplication of the rnf operon occurred and sequence data indicate that NQR evolved originally in the Bacteroidota (Munoz et al. 2020), which radiated about 1.7 billion years ago (Ward and Shih 2022). The loss of the rnfB gene from this duplicated operon was presumably compensated by acquiring a gene coding for a monooxygenase reductase of the FNR family. This gene codes for NqrF in NQR and replaces RnfB as electron input module. It seems likely that NQR originally evolved as a NADH: menaquinone reductase and ubiquinone reductase activity has evolved later, suggesting that NQR reducing menaquinone like the one from Segatella bryantii (Schleicher et al. 2021; Hau et al. 2024) represents an evolutionary older homolog.

Subunits, cofactors, and electron transfer in RNF/NQR complexes

A series of recent structures of Na+-NQR and RNF complexes yielded detailed insights into the architecture and function of these redox-driven pumps (Kishikawa et al. 2022; Vitt et al. 2022; Hau et al. 2023; Zhang and Einsle 2024; Kumar et al. 2025). A compilation of structural information available for RNF and NQR, as well as for individual NQR subunits from different bacteria is provided in the electronic supplementary material (Table S1). Functional properties of RNF and NQR which are derived from biochemical and physiological experiments are summarized in Table S2.

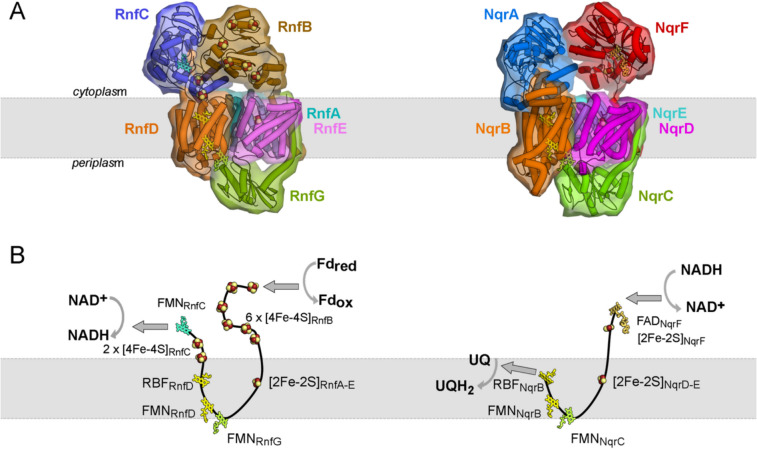

Despite the different functions of RNF and NQR in the diverse organisms most of their subunits are conserved and, in particular, the four membrane-bound subunits RnfAEDG and NqrEDBC exhibit a strikingly high structural similarity (Fig. 1). These four subunits constitute the energy-conserving core machinery and harbor a set of unusual redox cofactors: an intramembranous [2Fe-2S] cluster, two covalently attached FMNs, and a riboflavin (Fig. 1). The extraordinary properties of these cofactors are emphasized by the necessity to deploy additional proteins for the insertion into the complex. The covalent attachment of FMN (flavinylation) is catalyzed by the flavin transferase ApbE and was demonstrated for RNF from V. cholerae (Backiel et al. 2008), for RNF1 from A. vinelandii (Bertsova et al. 2021), and for the NQR from V. harveyi and K. pneumoniae (Bertsova et al. 2013). Moreover, the insertion of the intramembranous [2Fe-2S] into NQR seems to require the small membrane-bound iron-sulfur maturation protein NqrM in V. cholerae (Kostyrko et al. 2016; Agarwal et al. 2020). The genes coding for ApbE and NqrM are located on the nqr operon in V. cholerae downstream of the structural nqrABCDEF genes and are co-transcribed with the structural genes (Agarwal et al. 2020). The first structure of Na+-NQR in 2014 (Steuber et al. 2014) revealed that these aforementioned four cofactors, the intramembranous [2Fe-2S] cluster, the two covalently attached FMNs, and the riboflavin form an unexpected electron transfer pathway where the electron passes twice the cytoplasmic membrane. Electrons originating from an electron donor in the cytoplasm are transferred via these cofactors across the membrane to the periplasmic aspect and back to the electron acceptor at the cytoplasmic aspect (Fig. 1). This unusual pathway is, e.g., in stark contrast to complex I where the electron transfer chain is localized in the peripheral arm (reviewed in (Parey et al. 2020; Sazanov 2023)). Even more striking was the observation that several redox cofactors in the electron transfer chain reside too far from each other to allow for fast electron transfer. It became clear that several large conformational changes are required for the function of the complex (Steuber et al. 2014). Detailed information on these conformational changes became available only recently by new structural data on RNF and NQR (see also Table S1) in combination with kinetic analysis and site directed mutagenesis (Kishikawa et al. 2022; Vitt et al. 2022; Hau et al. 2023; Zhang and Einsle 2024; Kumar et al. 2025). In the following, we give a concise description of the structure of the individual subunits of RNF and NQR and describe their function in electron transfer and associated conformational changes starting from the electron donor subunit to the final electron acceptor subunit.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of RNF (C. tetanomorphum) and NQR (V. cholerae) architecture and electron transfer pathways. A Left, RNF from C. tetanomorphum (pdb code 7zc6); right, NQR from V. cholerae (pdb code 8a1w). The ferredoxin domain of RnfB, which was not resolved in the cryo-EM map, was modeled here by AlphaFold (Jumper et al. 2021) to complete the structure. Five out of the six subunits of both complexes share high homology as indicated by similar coloring. RnfC/NqrA: blue, RnfD/NqrB: orange, RnfG/NqrC: green, RnfA/NqrE: cyan, RnfE/NqrD: magenta; RnfB: brown, NqrF: red. B The cofactors of the integral transmembrane subunits RnfD/NqrB, RnfA/NqrE, RnfE/NqrD, and RnfG/NqrC are strictly conserved and reside at almost exactly the same positions in both complexes revealing an identical transmembrane electron-transfer pathway in RNF and NQR. RnfB subunit with six [4Fe-4S] clusters is structurally not related to NqrF, which harbors a FAD and a [2Fe-2S] cluster. RnfC and NqrA are structurally closely related; however, NqrA lacks any redox cofactors. The function of RnfC in the RNF complex is to transfer electrons from riboflavinRnfD to the electron acceptor NAD+, while in NQR the electrons are directly transferred to ubiquinone in the membrane. The grey arrows indicate the forward reaction from a low potential electron donor to a high potential electron acceptor

The electron input module RnfB/NqrF

In the forward electron transfer mode, RnfB accepts electrons from ferredoxin (Fig. 1) and inserts these into the catalytic core formed by RnfAEDG. RnfB is composed of a single N-terminal TM helix and two hydrophilic, cytoplasmic domains. In the RnfB subunits structurally characterized so far, the central ferredoxin-like cytoplasmic domain is flexibly tethered to the TM helix and contains one [4Fe-4S] cluster. The C-terminal cytoplasmic domain differs among RNF from different organisms, comprising between two and seven [4Fe-4S] clusters (Table 1). This domain serves as acceptor for cytoplasmic ferredoxins and transfers the electrons via the small [4Fe-4S] ferredoxin domain to the membrane subunits RnfA-E. Interestingly, the small ferredoxin-like domain of RnfB positioned between the C-terminal domain of RnfB and subunits RnfA-E is not well resolved in the structures reported so far (Vitt et al. 2022; Zhang and Einsle 2024; Kumar et al. 2025), which probably reflects a high degree of flexibility of this domain.

During evolution of NQR the RnfB subunit was replaced by NqrF (Reyes-Prieto et al. 2014) that is, similar to RnfB, composed of a single TM helix, a small and flexible ferredoxin-like domain carrying a [2 Fe-2S] cluster, and a larger electron input domain. The latter comprises a FAD containing FNR-like domain whose FADNqrF accepts a hydride from NADH. NqrF is not related to the NADH-oxidizing subunit of the mitochondrial complex I (Parey et al. 2021) and its NADH-binding pocket is therefore well-suited for the development of new antibiotics (Kaminski et al. 2022). Electrons are shuttled from these electron donor modules RnfB and NqrF into the conserved energy-converting core machinery. The four membrane subunits of this core are organized as three functional units, which catalyze transmembrane electron transfer and couple it to Na+ or H+ translocation across the membrane as shown by mutational and functional studies (Juárez et al. 2010) and the first structure of the NQR complex (Steuber et al. 2014).

RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD

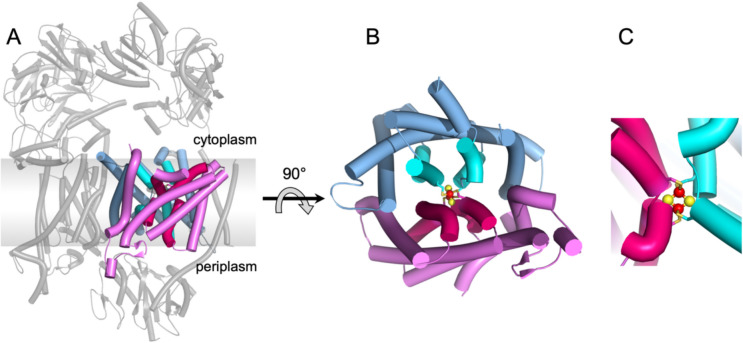

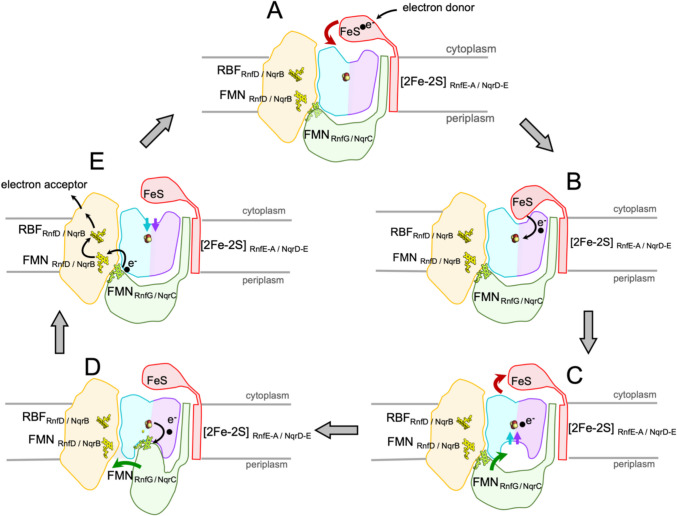

The first unit of the core machinery comprises a compact heterodimer of RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD that accepts a single electron from RnfB/NqrF and transfers the electron across the membrane to the periplasmic side as demonstrated by stopped-flow fast kinetics experiments for NQR (Hau et al. 2023). The structures of RnfA-E/NqrE-D are exceptionally well conserved (Table 1) reflected also by a high sequence identity between the RNF and NQR complexes (electronic supplementary material, Fig. S1). Interestingly, the rnfA and rnfE genes are result of a duplication of a single ancestor gene (Rapp et al. 2006). The structurally closely related encoded proteins are arranged in an inverted topology (Figs. 1, 2) (Sääf et al. 1999). Both subunits RnfA-RnfE or NqrE-NqrD consists each of six TM helices. As a whole, the RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD dimer exhibits eight outer TM helices that encircle four inner TM helices (Fig. 2). Notably, the inner four TM helices are interrupted by a short unstructured stretch splitting the helix into two half-helices. Each second half-helix contains a Cys residue, which together coordinate a [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 2) in the center of the RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD dimer and in the middle of the membrane. This extraordinary cluster has been characterized in detail for NQR by various spectroscopic techniques (Hau et al. 2023) and its presence in RNF has been confirmed by recent structural data (Zhang and Einsle 2024; Kumar et al. 2025). The [2Fe-2S] cluster in RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD dimer accepts electrons from the cytoplasmic FeS cluster of the flexible ferredoxin domain of RnfB/NqrF and transfers these electrons across the membrane to the periplasmic side to the flavin containing RnfG/NqrC. This transmembrane electron transfer is controlled by conformational changes of the RnfA-E/NqrD-E dimer, which are likely controlled by the redox-state of the intramembranous [2Fe-2S] cluster (Hau et al. 2023). Two major conformations representing snapshots of the transmembrane electron transfer have been resolved for NqrD-E in several structures (Hau et al. 2023), which must occur also in RnfA-E. Based on the experimental data it is proposed that in the oxidized state the RnfA-E/NqrD-E dimer opens towards the cytoplasmic side and the flexible ferredoxin domain of RnfB or NqrF can access the [2Fe-2S] cluster. Upon reduction of the cluster, the conformation of the dimer changes and opens towards to the periplasmic side while it closes at the cytoplasmic side. At the periplasmic side, the subunit RnfG/NqrC can now reach the [2Fe-2S] cluster in RnfA-E/NqrD-E to accept the electron (Fig. 3) as documented by structural and cross linking data (Hau et al. 2023). Thus, there is alternating access of the cytoplasmic and periplasmic redox partners to the [2Fe-2S] cluster in RnfA-E/NqrD-E dependent on the redox state of the cluster.

Fig. 2.

Architecture of the RnfA-E/NqrE-D dimer coordinating a membrane-bound [2Fe-2S] cluster. A, Structure of NQR of V. cholerae indicating the localization of NqrE (blue/cyan) and NqrD (magenta/purple) in NQR. The membrane plane is indicated by a grey box. B, View of the NqrE-D subunits from the periplasm. The inner helices of NqrE (cyan) and of NqrD (purple) each provide a Cys (in total 4) to coordinate the [2Fe-2S] cluster. C, Close-up view of the inner helices coordinating the [2Fe-2S] cluster.

Fig. 3.

Conformational changes during electron transfer in RNF/NQR. A The unusual electron transfer in RNF/NQR through the membrane is initiated by the transfer of an electron to the ferredoxin-like domain of RnfB/NqrF (red). The RnfE-A/NqrD-E heterodimer (magenta/cyan) adopts an inward conformation that allows access of the intramembranous [2Fe-2S]RnfE-A/NqrD-E cluster from the cytoplasmic side, whereas access for RnfG/NqrC (green) from the periplasmic/extracellular side is blocked. B The FeS cluster of the flexibly tethered ferredoxin-like domain of RnfB/NqrF can bind sufficiently close to [2Fe-2S]RnfE-A/NqrD-E to rapidly transfer an electron. C The reduction of [2Fe-2S]RnfE-A/NqrD-E triggers an inward-outward switch in subunits RnfE-A/NqrE-D, obstructing access to [2Fe-2S]RnfE-A/NqrD-E from the cytoplasmic side, and facilitating access to [2Fe-2S]RnfE-A/NqrD-E from the periplasmic/extracellular side. D RnfG/NqrC has shifted from RnfD/NqrB (yellow) to a position close to RnfE-A/NqrD-E and the electron is transferred from the [2Fe-2S]RnfE-A/NqrD-E to FMNRnfG/NqrC. E The oxidation of [2Fe-2S]RnfE-A/NqrD-E triggers the outward-inward switch and the rotation of RnfG/NqrC towards RnfD/NqrB. Subsequently, rapid electron transfer proceeds from FMNRnfG/NqrC to FMNRnfD/NqrB, and from there to riboflavin (RBF) in RnfD/NqrB. From RBFRnfD the electron is transferred to the proximal iron-sulfur cluster of subunit RnfC and from RBFNqrB, to ubiquinone

RnfG/NqrC

The second unit of the core machinery is represented by subunit RnfG/NqrC predominantly located at the extracellular/periplasmic membrane side. It is composed of a single N-terminal TM helix, a linker helix, and a large C-terminal globular α/β domain. The latter harbors as redox cofactor an FMN that is covalently attached to a conserved threonine (electronic supplementary material, Fig. S2) via a phosphodiester bond. The isoalloxazine ring of FMN is not fully embedded in the protein matrix and is partially exposed. The structures of RnfG and NqrC are reasonably well conserved, as documented by low RMSD values over the entire structure (Table 1); however, this is not reflected in sequence similarity. In structure-based alignments, the sequence identity is rather low, except for the regions in the proximity of the FMN. In particular conserved are residues 223–227 (NqrC V. cholerae numbering) containing the FMN-binding T225, residue K207 forming a salt bridge to the phosphate group of FMN, and residues 172–176 (Fig. S2), which form a binding pocket for the isoalloxazine ring. RnfG/NqrC shuttles the electron from RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD to RnfD/NqrB as proposed first for NQR (Steuber et al. 2014) bridging an unusually large distance of approximately 35 Å between the redox cofactors of these subunits (Figs. 3, 4). Electron transfer across such large distances is not feasible and is overcome by a large conformational change of RnfG/NqrC switching between RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD and RnfD/NqrB. For NQR, it was shown that the hydrophilic domain of NqrC undergoes a rotational movement by approximately 25–30° (Fig. 4). A combined approach using mutagenesis, cross-linking by engineered cysteines, and mass spectrometric studies together with X-ray and cryo-EM structures demonstrated that NqrC moves during catalysis between NqrD/NqrE and NqrB (Hau et al. 2023). Similar switching movements have been proposed for the homologous RnfG (Zhang and Einsle 2024; Kumar et al. 2025). Thus, RnfG/NqrC acts as an electron transfer switch module controlling electron transfer between [2Fe-2S]RnfAE/NqrED and FMNRnfD/NqrB. Notably, the cryo-EM structures determined so far of RNF or NQR complexes revealed RnfG/NqrC primarily located at RnfD/NqrB, while in the crystal structure of NQR the soluble domain of NqrC was positioned at the NqrDE dimer (Steuber et al. 2014) most likely stabilized by crystal contacts. These findings put forward that the localization of subunit RnfG/NqrC at RnfD/NqrB is energetically favored or stabilized and that the movement towards RnfA-RnfE/NqrE-NqrD heterodimer requires energy. However, the energetics causing these large movements of RnfG/NqrC are not yet understood and are subject of further investigations.

Fig. 4.

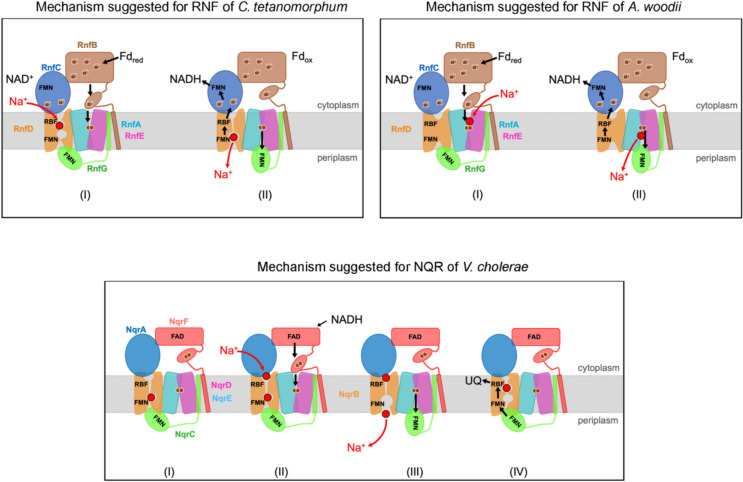

Proposed mechanisms of redox-driven Na+ transport by RNF and NQR. Conserved RNF/NQR subunits are presented with identical colors. In RNF operating in the forward electron transfer mode illustrated here, electrons are provided by reduced ferredoxin, while in NQR NADH serves as electron donor. Top, left: Proposed Na+ transport mechanism by RNF from C. tetanomorphum via a gated channel in RnfD. (I) The flexible reduced ferredoxin-like domain binds to the inward-facing state of RnfA-E, reduces its [2Fe-2S] cluster and fixes a Na+ in a strained state. (II) The RnfG shuttle moves to the outward-facing position of RnfA-E, thereby triggering pore opening at RnfD and Na+ passage. After reduction RnfG flips back to RnfD and induces a conformational change that leads to the release of Na+. The electron is transferred further to RnfC and NAD+. Top, right: Proposed Na+ transport mechanism by RNF from A. woodii via RnfA-E. (I) Na+ and the reduced RnfB ferredoxin-like domain bind to the inward-facing conformation. Upon [2Fe-2S]RnfA-E reduction, an inward-to-outward switch translocates Na+ to the periplasm. The electron is shuttled via RnfG, RnfD and RnfC to NAD+. Bottom: Proposed mechanism for NQR from V. cholerae via NqrB (I) Na+ is bound in NqrB at the periplasmic half-channel, but release is blocked by NqrC. NqrD-E heterodimer opens to the cytoplasmic side. (II) An electron is transferred from NqrF to the membrane [2Fe-2S]NqrD-E cluster. This triggers an inward-to-outward switch of NqrD-E and prompts Na+ binding to NqrB (III). NqrC moves from NqrB towards NqrD-E and Na+ is released from NqrB to the periplasm. (IV) NqrC switches back to NqrB. It is proposed that electron transfer to FMNNqrB triggers translocation of the Na+ in NqrB. The electron is transferred via riboflavinNqrB to ubiquinone. Starting again from state (I), the second electron derived from the FAD semiquinone in NqrF is injected into the core, and the cycle is repeated. Per NADH oxidized, one ubiquinol is formed and two Na+ are translocated

RnfD/NqrB

The third unit of the core machinery is subunit RnfD/NqrB, which represents with 10 TM helices the largest integral membrane subunit of RNF and NQR (Figs. 1, 3). Remarkably, RnfD/NqrB is structurally and evolutionary related to the ammonium/urea transporter family that also translocate cations or solutes across the membrane (Andrade et al. 2005; Levin et al. 2012). In contrast to the solute transporters, RnfD/NqrB contains FMN and riboflavin as redox cofactors. Riboflavin as a redox cofactor is rather unique to RNF and NQR and has not been observed so far in other flavin enzymes or respiratory complexes. While the riboflavin is localized closer to the cytoplasmic side, FMN is located in proximity to the periplasmic side and is covalently bound via a phosphodiester bond to a threonine (electronic supplementary material, Fig. S3). The electron is transferred from the FMN of the switch module RnfG/NqrC to FMNRnfD/NqrB, from which it rapidly flows to riboflavinRnfD/NqrB about 8 Å apart. The further electron transfer from riboflavinRnfD/NqrB to the terminal electron acceptor differs in RNF and NQR. In RnfD, the electron is shuttled from riboflavinRnfD to RnfC, the site of the terminal acceptor NAD+. In NqrB, the electron from riboflavinNqrB directly flows to the terminal electron acceptor ubiquinone bound to NqrB (Hau et al. 2023). The quinone binding site is not located within the protein core like, e.g., in complex I, but in a pocket at the protein surface. The binding site is formed by two further N-terminal amphipathic helices of NqrB (Hau et al. 2023) not present in RnfD (Fig. S3). Several inhibitors like 2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline-N-oxide (HQNO) (Hau et al. 2023), aurachin D-42, and korormicin A (Kishikawa et al. 2022) bind to this quinone-binding site of NqrB.

The electron output module RnfC

RnfC catalyzes NAD+ reduction in RNF operating in forward electron transfer mode and contains one FMN and 2 [4Fe-4S] cofactors (Fig. 1). The electron output module RnfC is primarily composed of a larger FMN-carrying domain that is related to the FMN containing NuoF of complex I, and a small C-terminal ferredoxin domain carrying two [4Fe-4S] clusters. The two [4Fe-4S] clusters bridge the riboflavin of RnfD inside the membrane (Fig. 1) to the FMN of RnfC (Vitt et al. 2022; Zhang and Einsle 2024; Kumar et al. 2025) and after the transfer of two electrons a hydride is donated from reduced FMN to NAD+ (Kuhns et al. 2020a). In contrast to RnfC of C. tetanomorphum or of A. woodii, RnfC of A. vinelandii displays a C-terminal elongated helix of more than 50 residues length, which interacts with RnfB and RnfH. The exact function of this long helix is not yet understood.

The subunit NqrA of NQR is highly homologous and structurally similar to RnfC; however, it does not contain any redox cofactors and cannot be assigned a direct function. We have speculated that NqrA might be required to stabilize the membrane subunit NqrB or the position of NqrF in the cytoplasm (Hau et al. 2023), but other functions cannot be ruled out.

Mechanism of redox-driven ion transport in RNF/NQR complexes

In light of the evolutionary relationship and high structural similarity between RNF and NQR, it is likely that both complexes operate via a similar mechanism for redox-driven ion translocation. The unique architecture of RNF/NQR compared to other well characterized respiratory complexes implies that ion translocation must be quite different from other so far described mechanisms, e.g., for complex I (Parey et al. 2020; Sazanov 2023). The unusual transmembrane electron transfer pathway and the large conformational changes linked to electron transfer in RNF/NQR clearly set them apart from other known respiratory complexes. This has been proposed already by the results from former biochemical, spectroscopic, and mutational studies on the redox reactions, the ion transport reaction and the coupling of both reactions as summarized in previous reviews (Verkhovsky and Bogachev 2010; Biegel et al. 2011; Juárez and Barquera 2012; Buckel and Thauer 2013; Steuber et al. 2015) (see also Table S2). And finally, considering a time span of at least 1 billion years of separate evolution of RNF and NQR (Reyes-Prieto et al. 2014; Munoz et al. 2020; Ward and Shih 2022) one cannot rule out some differences in the mechanism of these complexes.

While we meanwhile have very good evidence for the electron transfer steps and can provide a reasonable model, the ion transport process and the coupling between both processes is not fully understood yet and a matter of debate. So far, different putative mechanisms have been suggested for RNF and NQR (Fig. 4), nevertheless all mechanistic scenarios of RNF and NQR are based on common principles: Exergonic electron transfer steps and the endergonic ion translocation are indirectly coupled via various structural rearrangements.

In the mechanism suggested for NQR and for RNF from C. tetanomorphum, a central role of RnfD/NqrB is proposed (Vitt et al. 2022; Hau et al. 2023). Comparative structural studies revealed a close structural and evolutionary relationship between RnfD/NqrB and the ammonium/urea solute transporter family marking RnfD/NqrB as a plausible candidate for ion translocation. Of note, in the structures available so far, the observed conformational changes in RnfD/NqrB are rather small compared to the changes in other subunits. Nevertheless, comparison of RnfD/NqrB with the solute transporters revealed several differences. The structure of the solute transporters exhibits a continuous channel for the transported molecule. In contrast, in RnfD/NqrB, a putative ion pathway is characterized by a constriction blocking a continuous flow, which is required for a pumping mechanism. This constriction site is mainly formed by the bulky hydrophobic side chains of F338 and F342 (NqrB numbering), which might act as a gate during ion translocation. Mutation of either F338 or F342 to a smaller alanine resulted in 30% lower voltage formation for NQR. This might be caused by a backflow of Na+ due to incomplete closure of the proposed gate (Hau et al. 2023). The pathway through NqrB also includes a bona fide binding site of the coupling ion Na+ (Hau et al. 2023) localized between the constriction and a proposed periplasmic exit site. Since Na+ and water exhibit very similar density, Na+ can only be identified by the higher coordination number and the coordination geometry. In NqrB, the Na+ is coordinated by backbone carbonyl oxygens of A263, V275, V332 (Fig. S3) and two water molecules (Hau et al. 2023). Interestingly, in A. vinelandii RNF, the protonatable sidechain of glutamate E219 resides at the position of the Na+ in NQR, suggesting this site could allow binding of a proton instead of a Na+. C. tetanomorphum RnfD contains an alanine at this position, compatible with Na+ coordination (Fig. S3). As described in Fig. 4, the energy to convert the relaxed closed into the strained open state is presumably provided by Na+ binding (Vitt et al. 2022) and, in particular, by the conformational changes of the ferredoxin domain of RnfB/NqrF and RnfG/NqrC propagated to the constriction.

In a further mechanism recently described for RNF of A. woodii (Kumar et al. 2025), Na+ translocation is proposed to proceed across the RnfA-E heterodimer. Although the RnfA-E/NqrE-D have no structural homologue, its overall architecture with half helices in the core is reminiscent of H+/solute and Na+/solute symporters operating via an alternating access mechanism between inward-facing and outward-facing conformations (Gotfryd et al. 2020). Like H+/solute and Na+/solute symporters, the RnfA-E/NqrE-D dimer exhibits two different conformations, where the structure opens either to the cytoplasmic aspect or to the periplasmic aspect. Interestingly, the closure in the RnfA-E/NqrE-D dimer is in the midst of the membrane next to the [2Fe-2S] cluster. Kumar et al. (2025) proposed a conformational change in the RnfA-E dimer during electron transfer that allows a Na+ to shuttle across the membrane and supported this hypothesis by mutations and elaborate molecular dynamics studies.

The large conformational changes in RNF/NQR and the suggested mechanisms set these complexes apart from so far described respiratory enzymes and illustrate the different solutions nature has elaborated to couple redox reactions and transport processes. The recent studies have revealed many fascinating and unique properties of RNF/NQR, but future studies are needed to answer open questions and shed more light into the details of these remarkable molecular machines. New approaches might provide a comprehensive picture of putative further conformations of RNF/NQR and of the redox states coupled to distinct steps of ion translocation.

Structure and function of RNF and NQR: an outlook

Ferredoxins are primordial redox carriers, which link the central metabolism to ATP regeneration in many anaerobes. RNF plays a crucial role in pathways of energy conservation, which have occurred early in evolution, as it couples the oxidation of reduced ferredoxin to the build-up of an electrochemical Na+ (or H+) gradient driving ATP synthesis. RNF also provides reduced ferredoxin for energy-demanding processes such as N2 fixation, defining it as a versatile bioenergetic machine for reduction or oxidation of ferredoxins. Understanding the structure, function, and mechanism of RNF opens opportunities to optimize biotechnological processes and modulate the redox state of the ferredoxin pool in a cell with the help of RNF. Applying metabolic engineering could, e.g., potentially drive conversion of CO2 into biofuels in acetogenic bacteria (Katsyv and Müller 2020). Moreover, RNF and NQR are essential respiratory enzymes in many pathogens like pathogenic clostridia or highly virulent and multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which are top listed in the WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024 (Sati et al. 2025). The now available structures of these complexes represent an excellent basis for structure-based drug design to obtain novel, specific inhibitors against these pathogens, for which new antibiotics are urgently needed.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant 311211092 to GF and JS).

Abbreviations

- RNF

Rhodobacter nitrogen fixation complex (Na+ or H+ -translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase)

- RSX

Reducing system for SoxR

- NQR

Na+ or H+ -translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase

- Rbf

Riboflavin

- UQ

Ubiquinone

- UQH2

Ubiquinol

Author contribution

W.B., U.E., J.V, G.F and J.S. wrote the manuscript. U.E., J.V. and G.F. prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant 311211092).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agarwal S, Bernt M, Toulouse C, Kurz H, Pfannstiel J, D’Alvise P, Hasselmann M, Block AM, Häse CC, Fritz G, Steuber J (2020) Impact of Na + -translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase on iron uptake and nqrM expression in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 202. 10.1128/JB.00681-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alleman AB, Mus F, Peters JW (2021) Metabolic model of the nitrogen-fixing obligate aerobe Azotobacter vinelandii predicts its adaptation to oxygen concentration and metal availability. mBio 12:e02593–21. 10.1128/mBio.02593-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Andrade SLA, Dickmanns A, Ficner R, Einsle O (2005) Crystal structure of the archaeal ammonium transporter Amt-1 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:14994–14999. 10.1073/pnas.0506254102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backiel J, Zagorevski DV, Wang Z, Nilges MJ, Barquera B (2008) Covalent binding of flavins to RnfG and RnfD in the Rnf complex from Vibrio cholerae. Biochemistry 47:11273–11284. 10.1021/bi800920j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney BM (2020) Aerobic nitrogen-fixing bacteria for hydrogen and ammonium production: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:1383–1399. 10.1007/s00253-019-10210-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney BM, Plunkett MH (2022) Rnf1 is the primary electron source to nitrogenase in a high-ammonium-accumulating strain of Azotobacter vinelandii. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 106:5051–5061. 10.1007/s00253-022-12059-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher B, Müller V, Gottschalk G (1992) N5-methyl-tetrahydromethanopterin:coenzyme M methyltransferase of Methanosarcina strain Gö1 is an Na+-translocating membrane protein. J Bacteriol 174:7656–7660. 10.1128/jb.174.23.7656-7660.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsova YV, Fadeeva MS, Kostyrko VA, Serebryakova MV, Baykov AA, Bogachev AV (2013) Alternative pyrimidine biosynthesis protein ApbE is a flavin transferase catalyzing covalent attachment of FMN to a Threonine residue in bacterial flavoproteins. J Biol Chem 288:14276–14286. 10.1074/jbc.M113.455402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsova YV, Serebryakova MV, Baykov AA, Bogachev AV (2021) The flavin transferase ApbE flavinylates the ferredoxin:NAD+-oxidoreductase Rnf required for N2 fixation in Azotobacter vinelandii. FEMS Microbiol Lett 368:fnab130. 10.1093/femsle/fnab130 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Biegel E, Schmidt S, González JM, Müller V (2011) Biochemistry, evolution and physiological function of the Rnf complex, a novel ion-motive electron transport complex in prokaryotes. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:613–634. 10.1007/s00018-010-0555-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiangiu CD, Jayamani E, Brügel D, Herrmann G, Kim J, Forzi L, Hedderich R, Vgenopoulou I, Pierik AJ, Steuber J, Buckel W (2005) Sodium ion pumps and hydrogen production in glutamate fermenting anaerobic bacteria. Microb Physiol 10:105–119. 10.1159/000091558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann H, Bäumer S, Fricke WF, Wiezer A, Liesegang H, Decker I, Herzberg C, Martínez-Arias R, Merkl R, Henne A, Gottschalk G (2003) The genome sequence of Clostridium tetani, the causative agent of tetanus disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:1316–1321. 10.1073/pnas.0335853100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W (2021) Energy conservation in fermentations of anaerobic bacteria. Front Microbiol 12:703525. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.703525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buckel W, Thauer RK (2013) Energy conservation via electron bifurcating ferredoxin reduction and proton/Na+ translocating ferredoxin oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1827:94–113. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curatti L, Brown CS, Ludden PW, Rubio LM (2005) Genes required for rapid expression of nitrogenase activity in Azotobacter vinelandii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:6291–6296. 10.1073/pnas.0501216102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibrov P, Dibrov E, Pierce GN (2017) Na+-NQR (Na+-translocating NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) as a novel target for antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:653–671. 10.1093/femsre/fux032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Hidalgo E, Demple B (1996) The redox state of the [2Fe-2S] clusters in SoxR protein regulates its activity as a transcription factor. J Biol Chem 271:33173–33175. 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einsle O (2023) Catalysis and structure of nitrogenases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 83:102719. 10.1016/j.sbi.2023.102719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JG (2020) Methanosarcina acetivorans: a model for mechanistic understanding of aceticlastic and reverse methanogenesis. Front Microbiol 11:1806. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotfryd K, Boesen T, Mortensen JS, Khelashvili G, Quick M, Terry DS, Missel JW, LeVine MV, Gourdon P, Blanchard SC, Javitch JA, Weinstein H, Loland CJ, Nissen P, Gether U (2020) X-ray structure of LeuT in an inward-facing occluded conformation reveals mechanism of substrate release. Nat Commun 11:1005. 10.1038/s41467-020-14735-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D, Chen K, Elliott SJ, Nayak DD (2024) MmcA is an electron conduit that facilitates both intracellular and extracellular electron transport in Methanosarcina acetivorans. Nat Commun 15:3300. 10.1038/s41467-024-47564-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hau J-L, Kaltwasser S, Muras V, Casutt MS, Vohl G, Claußen B, Steffen W, Leitner A, Bill E, Cutsail GE, DeBeer S, Vonck J, Steuber J, Fritz G (2023) Conformational coupling of redox-driven Na+-translocation in Vibrio cholerae NADH:quinone oxidoreductase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 30:1686–1694. 10.1038/s41594-023-01099-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hau J-L, Schleicher L, Herdan S, Simon J, Seifert J, Fritz G, Steuber J (2024) Functionality of the Na+-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase and quinol:fumarate reductase from Prevotella bryantii inferred from homology modeling. Arch Microbiol 206:32. 10.1007/s00203-023-03769-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess V, Gallegos R, Jones JA, Barquera B, Malamy MH, Müller V (2016) Occurrence of ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase activity and its ion specificity in several Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. PeerJ 4:e1515. 10.7717/peerj.1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess V, Schuchmann K, Müller V (2013) The ferredoxin:NAD+ Oxidoreductase (Rnf) from the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii Requires Na+ and is reversibly coupled to the membrane potential. J Biol Chem 288:31496–31502. 10.1074/jbc.M113.510255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juárez O, Barquera B (2012) Insights into the mechanism of electron transfer and sodium translocation of the Na+-pumping NADH:quinone oxidoreductase. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1817:1823–1832. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juárez O, Morgan JE, Nilges MJ, Barquera B (2010) Energy transducing redox steps of the Na + -pumping NADH:quinone oxidoreductase from Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:12505–12510. 10.1073/pnas.1002866107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A, Potapenko A, Bridgland A, Meyer C, Kohl SAA, Ballard AJ, Cowie A, Romera-Paredes B, Nikolov S, Jain R, Adler J, Back T, Petersen S, Reiman D, Clancy E, Zielinski M, Steinegger M, Pacholska M, Berghammer T, Bodenstein S, Silver D, Vinyals O, Senior AW, Kavukcuoglu K, Kohli P, Hassabis D (2021) Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596:583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Vera L, Stegmann DP, Vering J, Eris D, Smith KML, Huang C-Y, Meier N, Steuber J, Wang M, Fritz G, Wojdyla JA, Sharpe ME (2022) Fast fragment- and compound-screening pipeline at the Swiss light source. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 78:328–336. 10.1107/S2059798322000705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsyv A, Müller V (2020) Overcoming energetic barriers in acetogenic C1 conversion. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8:621166. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.621166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishikawa J, Ishikawa M, Masuya T, Murai M, Kitazumi Y, Butler NL, Kato T, Barquera B, Miyoshi H (2022) Cryo-EM structures of Na+-pumping NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase from Vibrio cholerae. Nat Commun 13:4082. 10.1038/s41467-022-31718-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyrko VA, Bertsova YV, Serebryakova MV, Baykov AA, Bogachev AV (2016) NqrM (DUF539) Protein is required for maturation of bacterial Na+ -translocating NADH: Quinone oxidoreductase. J Bacteriol 198:655–663. 10.1128/JB.00757-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns M, Schuchmann V, Schmidt S, Friedrich T, Wiechmann A, Müller V (2020a) The Rnf complex from the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii: purification and characterization of RnfC and RnfB. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1861:148263. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns M, Trifunović D, Huber H, Müller V (2020b) The Rnf complex is a Na+ coupled respiratory enzyme in a fermenting bacterium. Thermotoga Maritima Commun Biol 3:431. 10.1038/s42003-020-01158-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Roth J, Kim H, Saura P, Bohn S, Reif-Trauttmansdorff T, Schubert A, Kaila VRI, Schuller JM, Müller V (2025) Molecular principles of redox-coupled sodium pumping of the ancient Rnf machinery. Nat Commun 16:2302. 10.1038/s41467-025-57375-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N (2020) How energy flow shapes cell evolution. Curr Biol 30:R471–R476. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K-L, Lee K-C, Lee J-H, Roe J-H (2022) Characterization of components of a reducing system for SoxR in the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J Microbiol 60:387–394. 10.1007/s12275-022-1667-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin EJ, Cao Y, Enkavi G, Quick M, Pan Y, Tajkhorshid E, Zhou M (2012) Structure and permeation mechanism of a mammalian urea transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:11194–11199. 10.1073/pnas.1207362109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienard T, Becher B, Marschall M, Bowien S, Gottschalk G (1996) Sodium ion translocation by N5 -methyltetrahydromethanopterin: coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanosarcina mazei Gö1 reconstituted in ether lipid liposomes. Eur J Biochem 239:857–864. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0857u.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marreiros BC, Calisto F, Castro PJ, Duarte AM, Sena FV, Silva AF, Sousa FM, Teixeira M, Refojo PN, Pereira MM (2016) Exploring membrane respiratory chains. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1857:1039–1067. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Del Campo JS, Rigsbee J, Bueno Batista M, Mus F, Rubio LM, Einsle O, Peters JW, Dixon R, Dean DR, Dos Santos PC (2022) Overview of physiological, biochemical, and regulatory aspects of nitrogen fixation in Azotobacter vinelandii. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 57:492–538. 10.1080/10409238.2023.2181309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkidjanian AY, Galperin MY, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV (2008) Evolutionary primacy of sodium bioenergetics. Biol Direct 3:13. 10.1186/1745-6150-3-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz R, Teeling H, Amann R, Rosselló-Móra R (2020) Ancestry and adaptive radiation of Bacteroidetes as assessed by comparative genomics. Syst Appl Microbiol 43:126065. 10.1016/j.syapm.2020.126065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parey K, Wirth C, Vonck J, Zickermann V (2020) Respiratory complex I—structure, mechanism and evolution. Curr Opin Struct Biol 63:1–9. 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parey K, Lasham J, Mills DJ, Djurabekova A, Haapanen O, Yoga EG, Xie H, Kühlbrandt W, Sharma V, Vonck J, Zickermann V (2021) High-resolution structure and dynamics of mitochondrial complex I—Insights into the proton pumping mechanism. Sci Adv 7:eabj3221. 10.1126/sciadv.abj3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Prakash D, Chauhan SS, Ferry JG (2019) Life on the thermodynamic edge: respiratory growth of an acetotrophic methanogen. Sci Adv 5:eaaw9059. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw9059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Raba DA, Rosas-Lemus M, Menzer WM, Li C, Fang X, Liang P, Tuz K, Minh DDL, Juárez O (2018) Characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa NQR complex, a bacterial proton pump with roles in autopoisoning resistance. J Biol Chem 293:15664–15677. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale SW (2008) Enzymology of the wood–ljungdahl pathway of acetogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1125:129–136. 10.1196/annals.1419.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale SW, Pierce E (2008) Acetogenesis and the wood–Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 fixation. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteomics 1784:1873–1898. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp M, Granseth E, Seppälä S, Von Heijne G (2006) Identification and evolution of dual-topology membrane proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13:112–116. 10.1038/nsmb1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Prieto A, Barquera B, Juárez O (2014) Origin and evolution of the sodium-pumping NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase. PLoS ONE 9:e96696. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sääf A, Johansson M, Wallin E, Von Heijne G (1999) Divergent evolution of membrane protein topology: the Escherichia coli RnfA and RnfE homologues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:8540–8544. 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio A, Silva V, Poeta P, Aonofriesei F (2022) Vibrio spp.: life strategies, ecology, and risks in a changing environment. Diversity 14:97. 10.3390/d14020097

- Sati H, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Hansen P, Garlasco J, Campagnaro E, Boccia S, Castillo-Polo JA, Magrini E, Garcia-Vello P, Wool E, Gigante V, Duffy E, Cassini A, Huttner B, Pardo PR, Naghavi M, Mirzayev F, Zignol M, Cameron A, Tacconelli E, Aboderin A, Al Ghoribi M, Al-Salman J, Amir A, Apisarnthanarak A, Blaser M, El-Sharif A, Essack S, Harbarth S, Huang X, Kapoor G, Knight G, Muhwa JC, Monnet DL, Ousassa T, Sacsaquispe R, Severin J, Sugai M, Taneja N, Umubyeyi Nyaruhirira A (2025) The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: a prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis S1473309925001185. 10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00118-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sazanov LA (2023) From the ‘black box’ to ‘domino effect’ mechanism: what have we learned from the structures of respiratory complex I. Biochem J 480:319–333. 10.1042/BCJ20210285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel K, Leone V, Faraldo-Gómez JD, Müller V (2012a) Promiscuous archaeal ATP synthase concurrently coupled to Na+ and H+ translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:947–952. 10.1073/pnas.1115796109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel K, Welte C, Deppenmeier U, Müller V (2012b) Electron transport during aceticlastic methanogenesis by Methanosarcina acetivorans involves a sodium-translocating Rnf complex. FEBS J 279:4444–4452. 10.1111/febs.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher L, Trautmann A, Stegmann DP, Fritz G, Gätgens J, Bott M, Hein S, Simon J, Seifert J, Steuber J (2021) A sodium-translocating module linking succinate production to formation of membrane potential in Prevotella bryantii. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e01211-e1221. 10.1128/AEM.01211-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmehl M, Jahn A, Vilsendorf MZ, A, Hennecke S, Masepohl B, Schuppler M, Marxer M, Oelze J, Klipp W (1993) Identification of a new class of nitrogen fixation genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus: a putative membrane complex involved in electron transport to nitrogenase. Molec Gen Genet 241–241:602–615. 10.1007/BF00279903 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schuchmann K, Müller V (2012) A bacterial electron-bifurcating hydrogenase. J Biol Chem 287:31165–31171. 10.1074/jbc.M112.395038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchmann K, Müller V (2014) Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:809–821. 10.1038/nrmicro3365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchmann K, Müller V (2016) Energetics and application of heterotrophy in acetogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:4056–4069. 10.1128/AEM.00882-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Huang R, Li L, Du K, Zhu F, Song C, Yuan X, Wang M, Wang S, Ferry JG, Zhou S, Yan Z (2023) Humic acid-dependent respiratory growth of Methanosarcina acetivorans involves pyrroloquinoline quinone. ISME J 17:2103–2111. 10.1038/s41396-023-01520-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuber J, Fritz G (2024) The Na+-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (Na+-NQR): Physiological role, structure and function of a redox-driven, molecular machine. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1865:149485. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2024.149485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuber J, Vohl G, Casutt MS, Vorburger T, Diederichs K, Fritz G (2014) Structure of the V. cholerae Na+-pumping NADH:quinone oxidoreductase. Nature 516:62–67. 10.1038/nature14003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuber J, Vohl G, Muras V, Toulouse C, Claußen B, Vorburger T, Fritz G (2015) The structure of Na+-translocating of NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase of Vibrio cholerae: implications on coupling between electron transfer and Na+ transport. Biol Chem 396:1015–1030. 10.1515/hsz-2015-0128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suharti S, Wang M, De Vries S, Ferry JG (2014) Characterization of the RnfB and RnfG subunits of the Rnf complex from the archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans. PLoS ONE 9:e97966. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulouse C, Claussen B, Muras V, Fritz G, Steuber J (2017) Strong pH dependence of coupling efficiency of the Na+-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (Na+-NQR) of Vibrio cholerae. Biol Chem 398:251–260. 10.1515/hsz-2016-0238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unemoto T, Hayashi M, Hayashi M (1977) Na+-dependent activation of NADH oxidase in membrane fractions from halophilic Vibrio alginolyticus and V. costicolus. The Journal of Biochemistry 82:1389–1395. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhovsky MI, Bogachev AV (2010) Sodium-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase as a redox-driven ion pump. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1797:738–746. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitt S, Prinz S, Eisinger M, Ermler U, Buckel W (2022) Purification and structural characterization of the Na+-translocating ferredoxin: NAD+ reductase (Rnf) complex of Clostridium tetanomorphum. Nat Commun 13:6315. 10.1038/s41467-022-34007-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM, Shih PM (2022) Phototrophy and carbon fixation in Chlorobi postdate the rise of oxygen. PLoS ONE 17:e0270187. 10.1371/journal.pone.0270187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal L, Wiechmann A, Baker J, Minton NP, Müller V (2018) The Rnf complex is an energy-coupled transhydrogenase essential to reversibly link cellular NADH and ferredoxin pools in the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii. J Bacteriol 200. 10.1128/JB.00357-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y (2005) TM-align: a protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res 33:2302–2309. 10.1093/nar/gki524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Einsle O (2024) Architecture of the RNF1 complex that drives biological nitrogen fixation. Nat Chem Biol 20:1078–1085. 10.1038/s41589-024-01641-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.