Abstract

Purposes

The preoperative distinction between atypical meningioma (AM) and intracranial solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) holds significant importance in guiding surgical approach decisions and prognostic assessments.

Methods

A total of 310 SFT patients and 203 AM patients were retrospectively included and stratified into training and validation cohorts. Employing the elastic net algorithm, relevant features were identified to form the fusion radiomic model. Subsequently, a clinical-radiomic combined model was developed by integrating the fusion radiomic model with significant clinical variables through multivariate logistic regression analysis. The models’ calibration, discriminative capacity, and clinical utility were thoroughly assessed.

Results

The fusion radiomic model was crafted from 17 radiomic features, achieving AUC values of 0.920 in the training set and 0.870 in the validation set. Subsequently, the clinical-radiomic combined model exhibited AUC values of 0.930 and 0.890 in the training and validation sets, indicating commendable discrimination and calibration. Assessment through decision curve analysis underscored the clinical utility of both the fusion radiomic model and the clinical-radiomic combined model for individuals with intracranial SFT and AM.

Conclusions

The clinical-radiomic combined model exhibited notable sensitivity and exceptional efficacy in the distinctive diagnosis of intracranial SFT and AM, holding promise for the non-invasive advancement of personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Intracranial solitary fibrous tumor, Atypical meningioma, Radiomics, Algorithm, Diagnosis

Introduction

Intracranial solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) represents a rare mesenchymal tumor distinguished by its marked aggressiveness and substantial vascularization, also known as hemangiopericytoma (HPC) [1, 2]. HPC are now commonly called by the international neuro-oncology community as intracranial SFT and possess well defined neuropathological characteristics such as positive expression of mainly STAT6 but also CD34, Bcl-2 protein, and vimentin [3]. Various aspects of intracranial SFT bear resemblance to meningioma, as both entities stem from the meninges and share akin imaging attributes, notably in the case of atypical meningioma (AM), posing challenges in preoperative differentiation from intracranial SFT. Nonetheless, AM and intracranial SFT manifest distinct histological traits and biological behaviors [4, 5].

In contrast to AMs, intracranial SFT of WHO grade II-III are categorized as malignant tumors displaying a proclivity for recurrence and metastasis [6]. Intracranial SFT exhibits heightened aggression, robust vascularization, and a susceptibility to intraoperative hemorrhage, accompanied by an elevated postoperative recurrence rate and a bleaker prognosis [1, 7]. Consequently, meticulous preoperative preparations are imperative to facilitate maximal surgical resection and ensure safety for intracranial SFT, involving nuanced surgical approaches, preoperative embolization of tumor-feeding arteries, utilization of intraoperative navigation tools, and adequate blood reserves [8, 9]. The divergent preoperative readiness and therapeutic paradigms for these two tumors underscore the significance of precise preoperative differentiation. The substantial convergence in radiological traits between intracranial SFT and AM presents a formidable obstacle to preoperative imaging distinction [10]. Despite the typical male predominance and relatively early onset associated with intracranial SFT, diagnosis based solely on these factors proves challenging [11]. Earlier research has indicated that radiomic characteristics could aid in discerning intracranial SFT from meningioma [5, 12]. Nevertheless, greater emphasis should be placed on differentiating between AM and intracranial SFT, given their higher likelihood of clinical confusion.

Radiomics represents an effective and non-invasive approach for the comprehensive exploration of tumor characteristics on a large scale [13, 14]. Within the realm of neuro-oncologic radiomics, the extraction of high-dimensional information and concealed insights not accessible through traditional imaging methodologies can significantly enhance the diagnostic precision and efficacy concerning intracranial tumors [15–17]. The study of intracranial SFT and AM has historically encountered limitations due to their relatively low incidence rates, with a current absence of radiomic studies catering to the differential diagnosis of these tumors. Therefore, the primary objective of this investigation is to construct a clinical-radiomic combined model integrating radiomic features with clinical data to enable the pre-surgical differentiation of intracranial SFT and AM. This model aims to facilitate preoperative management strategies and treatment decisions for patients afflicted with intracranial SFT and AM.

Materials and methods

Patients

In this study, a cohort of 513 individuals diagnosed with intracranial SFT (n = 310) or AM (n = 203) was collected fromBeijing Tiantan Hospital of Capital Medical University according to the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) pathology classification criteria for central nervous system tumors [4]. The selection criteria for SFT and AM patients outlined as follows: (1) individuals diagnosed with intracranial SFT or AM who underwent primary tumor resection surgery at Beijing Tiantan Hospital between 2010 and 2022; (2) availability of postoperative pathological diagnostic results; (3) completion of preoperative cranial T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging (CE-T1WI) MRI scans; (4) comprehensive clinical data recorded at the time of initial diagnosis. Subsequently, all participants were randomly allocated to either the training group (utilized for model construction, n = 342) or the validation group (utilized for model validation, n = 171) in a 2:1 ratio.

Clinical characteristics

A total of seven preoperative clinical parameters were gathered from all enrolled patients, encompassing age, gender, location 1 (supratentorial or infratentorial), location 2 (skull base or non-skull base), location 3 (paravenous sinus or non-paravenous sinus), presence of dural tail (negative or positive), and occurrence of peritumoral serious edema (negative or positive). Additionally, the postoperative pathological findings of each patient are instrumental in determining whether the tumor corresponds to an intracranial SFT or an AM. According to the 2021 WHO pathology guidelines [2, 4], AM is characterized by elevated mitotic activity (defined as ≥ 4 mitoses per 10 high-power fields), evidence of brain invasion, or the presence of at least three distinct histological features, which include high cellularity, prominent nucleoli, sheet-like architecture, or spontaneous necrosis [18, 19].

Regions of interest (ROI) delineating and radiomic feature extraction

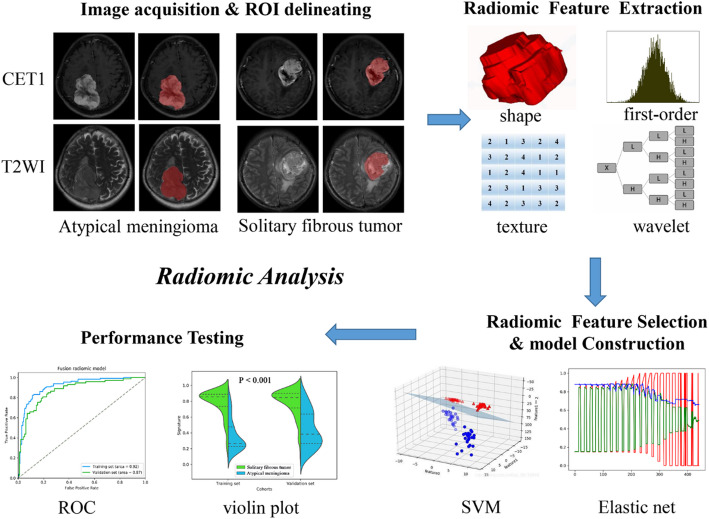

The illustration in Figure.1 portrays the sequential steps involved in this investigation. An adept neuroradiologist boasting 8 years of experience employed the ITK-SNAP software for delineating the three-dimensional regions of interest (ROIs) pertaining to the tumors evident in the T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging (CE-T1WI) MRI scans. Subsequently, a seasoned neurosurgeon with 13 years of expertise validated the segmentation process. Any discrepancies arising between the two neuroradiologists were adjudicated through collaborative discourse. Following this, the PyRadiomics algorithm was leveraged to extract a total of 1562 quantitative radiomic features from the mentioned segmented ROIs, all of which were standardized to a numerical scale ranging from 0 to 1 [17, 20].

The delineation of the four feature types proceeded as follows [17]: (1) The shape and size features (n = 14) remained unaffected by the grayscale intensity distribution within the tumor; (2) First-order statistics (n = 180) delineated the voxel intensity distribution in the image through foundational metrics; (3) Texture features (n = 680) were derived from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) and gray-level run-length matrix (GLRLM) to delineate the spatial distribution or patterns of voxel intensity; (4) Wavelet features (n = 688) effectively separated textural data by decomposing the original image into low and high frequencies akin to Fourier analysis, ensuring the disentanglement of textural information.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the present study. (I) a. Brain MR images acquisition (axial T2WI and sagittal CE-T1WI). b. ROI segmentation by ITK-SNAP software. (II) Four categories radiomics features extracted by PyRadiomics algorithm. (III) Radiomic Feature selection by elastic net and support vector machine (SVM) algorithm. (IV) And model training and testing

Radiomic features selection and fusion radiomic model construction

Following the extraction of radiomic features, a discriminative process is implemented to mitigate overfitting concerns [17, 21]. Initially, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied to identify the substantially distinct radiomic features between patients presenting intracranial SFT and AM. Subsequently, the elastic net al.gorithm, integrating the virtues of the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) and ridge regression, was employed to cherry-pick the most enlightening features [15]. LASSO, a prevalent tool in high-dimensional data analysis, holds promise in enhancing predictive accuracy and interpretability. Lastly, recursive feature elimination (RFE) was engaged to ascertain the ultimate radiomic features, a process facilitated by a quintuple cross-validation methodology.

Subsequent to the screening of radiomic features, a T1 radiomic model was meticulously crafted around the chosen CE-T1WI radiomic characteristics. Concurrently, the T2 radiomic model was meticulously fashioned utilizing T2 radiomic features. A unified radiomic model, amalgamating CE-T1WI and T2 radiomic features, was meticulously devised employing the support vector machine (SVM) method within the training dataset. Moreover, the violin plot technique was harnessed to discern variations in the distribution of signatures within the fusion radiomic model between intracranial SFT and AM across both the training and validation datasets. To exhibit the predictive potential of the fusion radiomic model, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was enlisted [22].

Construction and validation of clinical and clinical-radiomic combined model

The model derived from all clinical characteristics was systematically crafted utilizing multivariate logistic regression analysis. Subsequently, to refine a more precise and thorough model to differentiate between intracranial SFT and AM, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) [23] was leveraged to identify the most critical clinical features. An intricate clinical-radiomic combined model was then fashioned through the integration of the fusion radiomic model and pivotal clinical features. The configuration and parameters of this clinical-radiomic combined model were elucidated in the form of a nomogram. Extensive assessments were carried out using ROC curve analyses to assess the discriminatory efficacy of both the clinical model and the clinical-radiomic combined model.

Calibration curve analysis (CCA) and decision curve analysis (DCA)

The CCA evaluates the alignment between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes utilizing the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. In our study, both CCA and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test were employed to assess the concordance between observed pathological findings and the predicted diagnostic outcomes of the fusion radiomic model and the clinical-radiomic combined model. Additionally, the clinical utility of both models was assessed using DCA, which quantifies the net benefits across various threshold probabilities [24]. DCA evaluates clinical utility by calculating the net benefit at different thresholds, weighing the clinical implications of true-positive identifications against the unnecessary interventions prompted by false positives, thereby simulating real-world diagnostic decision-making scenarios. The CCA has validated the statistical accuracy of the models, while DCA demonstrates their practical significance in clinical practice.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Within this investigation, a cohort comprising 513 individuals diagnosed with either intracranial SFT or AM was delineated. The average age at diagnosis stood at 47.0 years (ranging from 35.0 to 56.0 years), with a nearly balanced male-to-female ratio of 1.004:1 (257 males and 256 females). Among the cohort, 171 patients (33.3%) exhibited peritumoral edema, while 90 patients (17.5%) displayed a dural tail in CET1WI images. Specifically, 310 patients (60.4%) received a pathological diagnosis of intracranial SFT, while 203 patients (39.6%) were categorized as AM cases. A comprehensive overview of all incorporated clinical features can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics of training and validation sets

| Characteristics | All sets (n = 513) | Training set(n = 342) | Validation set (n = 171) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 47.0(35.0–56.0) | 47.0(35.0–56.0) | 45.0(35.0–56.0) | 0.841 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 256(49.9%) | 168(49.1%) | 88(51.5%) | 0.617 |

| Male | 257(50.1%) | 174(50.9%) | 83(48.5%) | |

| Location 1 | ||||

| Supratentorial | 418(81.5%) | 279(81.6%) | 139(81.3%) | 0.936 |

| Infratentorial | 95(18.5%) | 63(18.4%) | 32(18.7%) | |

| Location 2 | ||||

| Non skull base | 329(64.1%) | 222(64.9%) | 107(62.6%) | 0.603 |

| Skull base | 184(35.9%) | 120(35.1%) | 64(37.4%) | |

| Location 3 | ||||

| Non paravenous sinus | 303(59.1%) | 199(58.2%) | 104(60.8%) | 0.568 |

| Paravenous sinus | 210(40.9%) | 143(41.8%) | 67(39.2%) | |

| Dural tail | ||||

| Negative | 423(82.5%) | 287(83.9%) | 136(79.5%) | 0.218 |

| Positive | 90(17.5%) | 55(16.1%) | 35(20.5%) | |

| Peritumoral edema | ||||

| Negative | 342(66.7%) | 220(64.3%) | 122(71.3%) | 0.112 |

| Positive | 171(33.3%) | 122(35.7%) | 49(28.7%) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| SFT | 310(60.4%) | 212(62.0%) | 98(57.3%) | 0.307 |

| AM | 203(39.6%) | 130(38.0%) | 73(42.7%) |

Categorical variables were presented as the number (percentage). Continuous variables consistent with a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, otherwise the median and quartile are used. Chi-Square was used to compare the differences in categorical variables. Nonparametric test was used to compare the differences in continuous variables with non-normal distribution

SFT, Solitary fibrous tumor; AM, Atypical meningioma

The comparison between the training set and the validation set revealed no substantial interclass distinctions concerning age (P = 0.841), gender (P = 0.617), location 1, 2, 3 (P = 0.936, 0.603, 0.568), presence of a dural tail (P = 0.218), peritumoral edema (P = 0.112), and diagnostic outcomes (P = 0.307) as delineated in Table 1. These findings support the validity of employing both datasets for training and testing purposes.

Correlation between postoperative pathological diagnosis and clinical characteristics

Age, supratentorial or infratentorial location, the presence of a dural tail, and peritumoral edema exhibited significant correlations with the pathological diagnosis (all P < 0.01, Table 2). The findings indicated that older patients with infratentorial tumors featuring a dural tail and severe peritumoral edema were more prone to an AM diagnosis. In contrast, there were no discernible gender disparities (P = 0.437) or variations in location 2 and 3 (P = 0.473, 0.869) observed between patients diagnosed with intracranial SFT and those with AM.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) and atypical meningioma (AM)

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 513) | SFT (n = 310) |

AM (n = 203) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 47.0(35.0–56.0) | 43.5(32.0–52.0) | 52.0(41.0–62.0) | 0.000 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 256(49.9%) | 159(51.3%) | 97(47.8%) | 0.437 |

| Male | 257(50.1%) | 151(48.7%) | 106(52.2%) | |

| Location 1 | ||||

| Supratentorial | 418(81.5%) | 240(77.4%) | 178(87.7%) | 0.003 |

| Infratentorial | 95(18.5%) | 70(22.6%) | 25(12.3%) | |

| Location 2 | ||||

| Non skull base | 329(64.1%) | 195(62.9%) | 134(66.0%) | 0.473 |

| Skull base | 184(35.9%) | 115(37.1%) | 69(34.0%) | |

| Location 3 | ||||

| Non paravenous sinus | 303(59.1%) | 184(59.4%) | 119(58.6%) | 0.869 |

| Paravenous sinus | 210(40.9%) | 126(40.6%) | 84(41.4%) | |

| Dural tail | ||||

| Negative | 423(82.5%) | 290(93.5%) | 133(65.5%) | 0.000 |

| Positive | 90(17.5%) | 20(6.5%) | 70(34.5%) | |

| Peritumoral edema | ||||

| Negative | 342(66.7%) | 233(75.2%) | 109(53.7%) | 0.000 |

| Positive | 171(33.3%) | 77(24.8%) | 94(46.3%) |

Categorical variables were presented as the number (percentage). Continuous variables consistent with a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, otherwise the median and quartile are used. Chi-Square was used to compare the differences in categorical variables. Nonparametric test was used to compare the differences in continuous variables with non-normal distribution

SFT, Solitary fibrous tumor; AM, Atypical meningioma

In Table 3, univariate analysis was employed to identify the distinct clinical risk factors independently influencing postoperative pathological diagnoses within both the training and validation sets.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of clinical characteristics of intracranial solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) and atypical meningioma (AM) patients in the training set and validation set

| Characteristics | Training set (n = 342) | P-value | Validation set(n = 171) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFT (n = 212) |

AM (n = 130) |

SFT (n = 98) |

AM (n = 73) |

|||

| Age (year) | 45.0(31.0–52.0) | 52.5(40.8–64.0) | 0.000 | 41.0(34.0-51.5) | 50.0(41.5–58.5) | 0.000 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 112(52.8%) | 56(43.1%) | 0.080 | 47(48.0%) | 41(56.2%) | 0.288 |

| Male | 100(47.2%) | 74(56.9%) | 51(52.0%) | 32(43.8%) | ||

| Location 1 | ||||||

| Supratentorial | 164(77.4%) | 115(88.5%) | 0.010 | 76(77.6%) | 63(86.3%) | 0.147 |

| Infratentorial | 48(22.6%) | 15(11.5%) | 22(22.4%) | 10(13.7%) | ||

| Location 2 | ||||||

| Non skull base | 137(64.6%) | 85(65.4%) | 0.886 | 58(59.2%) | 49(67.1%) | 0.289 |

| Skull base | 75(35.4%) | 45(34.6%) | 40(20.8%) | 24(32.9%) | ||

| Location 3 | ||||||

| Non paravenous sinus | 123(58.0%) | 76(58.5%) | 0.936 | 61(62.2%) | 43(58.9%) | 0.658 |

| Paravenous sinus | 89(42.0%) | 54(41.5%) | 37(37.8%) | 30(41.1%) | ||

| Dural tail | ||||||

| Negative | 199(93.9%) | 88(67.7%) | 0.000 | 91(92.9%) | 45(61.6%) | 0.000 |

| Positive | 13(6.1%) | 42(32.3%) | 7(7.1%) | 28(38.4%) | ||

| Peritumoral edema | ||||||

| Negative | 155(73.1%) | 65(50.0%) | 0.000 | 78(79.6%) | 44(60.3%) | 0.006 |

| Positive | 57(26.9%) | 65(50.0%) | 20(20.4%) | 29(39.7%) | ||

Categorical variables were presented as the number (percentage). Continuous variables consistent with a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, otherwise the median and quartile are used. Chi-Square was used to compare the differences in categorical variables. Nonparametric test was used to compare the differences in continuous variables with non-normal distribution

SFT, Solitary fibrous tumor; AM, Atypical meningioma

Within the training and validation sets, univariate analysis was utilized to identify the autonomous clinical risk traits influencing pathological diagnoses. Consistent with earlier findings, a substantial relationship was observed between the diagnosis and age (P < 0.0001), location 1 (P = 0.01), the presence of a dural tail (P < 0.0001), and peritumoral edema (P < 0.0001) in the training set. In the validation set, age (P < 0.0001), the presence of a dural tail (P < 0.0001), and peritumoral edema (P = 0.006) demonstrated tendencies toward an association with the pathological diagnosis.

Radiomic feature selection and radiomic model construction

Initially, 3124 radiomic features were derived from T2WI and CE-T1WI MRI scans in a single patient. Subsequently, 888 radiomic features were distilled using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, with 21 valuable features discerned via the ‘elastic net’ algorithm. Ultimately, the RFE algorithm pinpointed 17 radiomic features (comprising 11 from CE-T1WI and 6 from T2WI images) as definitive features for subsequent model development. Each of these 17 chosen radiomic features, encompassing 3 first-order features, 10 texture features, and 4 wavelet features, showcased remarkable distinctions between patients with intracranial SFT and AM (all P < 0.0001, as delineated in Table 4).

Table 4.

Detail information of 17 selected key radiomic features

| Squence | Feature name | Feature type | SFT | AM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CET1 | square_firstorder_Skewness | First order | 0.420(0.358–0.499) | 0.479(0.412–0.548) | 0.0001 |

| square_glcm_InverseVariance | Texture | 0.192(0.134–0.275) | 0.297(0.198–0.457) | 0.0001 | |

| gradient_glcm_InverseVariance | Texture | 0.650(0.550–0.749) | 0.765(0.640–0.862) | 0.0001 | |

| exponential_glcm_InverseVariance | Texture | 0.404(0.261–0.596) | 0.664(0.436–0.797) | 0.0001 | |

| exponential_glcm_DifferenceVariance | Texture | 0.074(0.018–0.160) | 0.017(0.003–0.070) | 0.0001 | |

| exponential_gldm_DependenceNonUniformity | Texture | 0.154(0.076–0.302) | 0.070(0.037–0.129) | 0.0001 | |

| squareroot_glcm_DifferenceAverage | Texture | 0.186(0.140–0.264) | 0.149(0.108–0.208) | 0.0001 | |

| square_glrlm_RunPercentage | Texture | 0.957(0.932–0.970) | 0.936(0.892–0.959) | 0.0001 | |

| square_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity | Texture | 0.166(0.076–0.331) | 0.097(0.048–0.174) | 0.0001 | |

| wavelet-LHL_firstorder_Maximum | Wavelet | 0.321(0.249–0.443) | 0.237(0.174–0.321) | 0.0001 | |

| wavelet-HLL_glrlm_GrayLevelVariance | Wavelet | 0.165(0.110–0.290) | 0.108(0.056–0.204) | 0.0001 | |

| T2WI | lbp-3D-m1_glcm_ClusterProminence | First order | 0.673(0.593–0.7750) | 0.590(0.499–0.649) | 0.0001 |

| lbp-3D-m1_firstorder_InterquartileRange | First order | 0.580(0.500-0.714) | 0.500(0.429–0.571) | 0.0001 | |

| logarithm_glcm_InverseVariance | Texture | 0.484(0.381–0.597) | 0.622(0.486–0.734) | 0.0001 | |

| squareroot_glcm_DifferenceVariance | Texture | 0.107(0.055–0.187) | 0.050(0.030–0.103) | 0.0001 | |

| wavelet-HHL_glszm_Zone% | Wavelet | 0.544(0.448–0.677) | 0.409(0.299–0.577) | 0.0001 | |

| wavelet-HHH_glcm_JointAverage | Wavelet | 0.400(0.281–0.520) | 0.320(0.239–0.438) | 0.0001 |

SFT, Solitary fibrous tumor; AM, Atypical meningioma; T2WI, T2-weighted imaging; CE- T1WI, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging

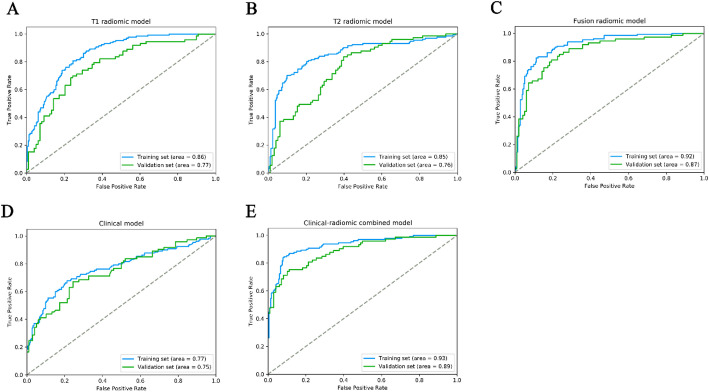

The selected 11 CE-T1WI radiomic features were then entered into an SVM to build a T1 radiomic model, which showed discrimination in predicting the postoperative pathological diagnosis with AUC values of 0.860 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.834–0.880, training set) and 0.770 (95% CI, 0.744–0.801, validation set) (Figure. 2 A and Table 5). The T2 radiomic model was constructed by SVM with 6 T2WI radiomic features, and its AUC value was 0.850 (95% CI, 0.827–0.880) in the training set and 0.760 (95% CI, 0.728–0.787) in the validation set (Figure. 2B; Table 5).

Table 5.

Detail diagnostic ability of all developed models

| Model | Performance | AUC | ACC | SE | SP | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CET1 radiomic model | Training set | 0.860(0.834–0.880) | 0.754(0.728–0.782) | 0.577(0.524–0.629) | 0.863(0.836–0.892) | 0.721(0.671–0.775) | 0.769(0.736-0.800) |

| Validation set | 0.770(0.744–0.801) | 0.696(0.669–0.725) | 0.411(0.366–0.458) | 0.908(0.884–0.932) | 0.769(0.713–0.824) | 0.674(0.641–0.709) | |

| T2 radiomic model | Training set | 0.850(0.827–0.880) | 0.795(0.770–0.821) | 0.754(0.711–0.798) | 0.821(0.789–0.852) | 0.721(0.675–0.766) | 0.845(0.816–0.873) |

| Validation set | 0.760(0.728–0.787) | 0.673(0.644–0.701) | 0.616(0.569–0.663) | 0.714(0.679–0.750) | 0.616(0.570–0.662) | 0.714(0.678–0.751) | |

| Clinical model | Training set | 0.770(0.735–0.801) | 0.749(0.721–0.776) | 0.500(0.451–0.550) | 0.901(0.877–0.925) | 0.756(0.703–0.811) | 0.746(0.715–0.777) |

| Validation set | 0.750(0.715–0.775) | 0.690(0.662–0.717) | 0.452(0.405–0.498) | 0.867(0.840–0.893) | 0.717(0.664–0.769) | 0.680(0.645–0.713) | |

| Fusion radiomic model | Training set | 0.920(0.898–0.934) | 0.839(0.816–0.862) | 0.831(0.792–0.870) | 0.844(0.816–0.872) | 0.766(0.726–0.806) | 0.890(0.864–0.917) |

| Validation set | 0.870(0.849–0.896) | 0.789(0.764–0.815) | 0.699(0.655–0.743) | 0.857(0.828–0.886) | 0.785(0.743–0.826) | 0.792(0.760–0.825) | |

| Clinical-radiomic model | Training set | 0.930(0.911–0.946) | 0.874(0.854–0.895) | 0.792(0.751–0.834) | 0.925(0.904–0.946) | 0.866(0.830–0.902) | 0.879(0.854–0.904) |

| Validation set | 0.890(0.868–0.908) | 0.819(0.795–0.842) | 0.671(0.627–0.717) | 0.929(0.907–0.950) | 0.875(0.839–0.910) | 0.791(0.761–0.821) |

ACC, accuracy; AUC, area under curve; PPV, positive predict value; NPV, negative predictive value

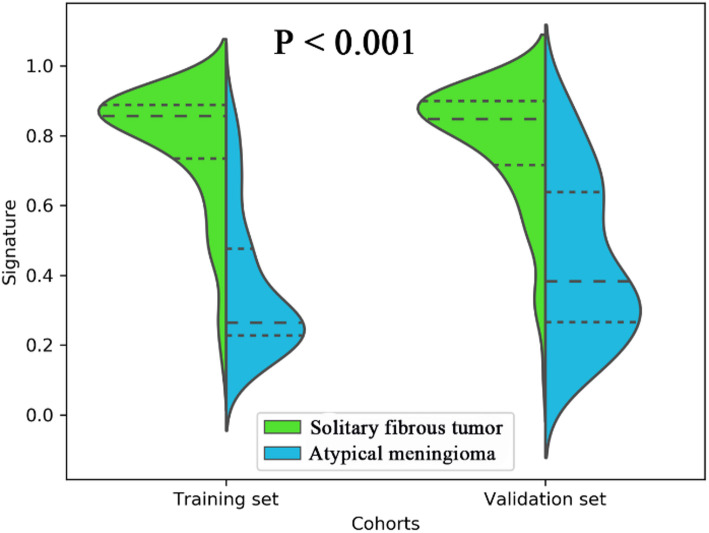

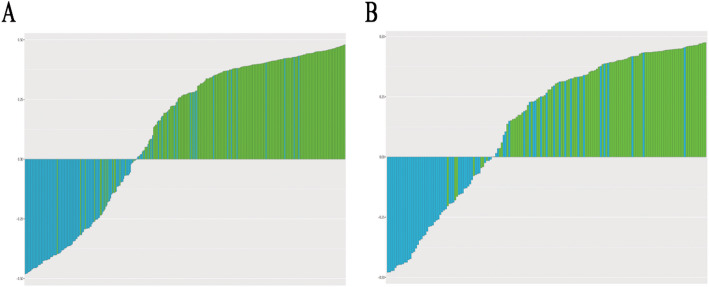

Employing all 17 designated features, a fusion radiomic model was meticulously crafted. The violin plot vividly illustrated substantial disparities in the distribution pattern of the fusion radiomic model’s signature between intracranial SFT and AM within both the training and validation cohorts (All P < 0.01; as shown in Fig. 3). Exhibiting remarkable discernment capabilities, the fusion radiomic model exhibited exemplary accuracy in prognosticating postoperative pathological diagnoses, boasting AUC values of 0.920 (95% CI, 0.898–0.934, training set) and 0.870 (95% CI, 0.849–0.896, validation set) correspondingly (Fig. 2C; Table 5).

Fig. 3.

A violin plot comparing the signature distribution of the fusion radiomic model between intracranial solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) and atypical meningioma (AM) patients

Fig. 2.

The performance of ROC curves for the three predictive models the training and validation sets. (A) T1 radiomic model; (B) T2 radiomic model; (C) fusion radiomic model; (D) Clinical model; (E) Clinical-radiomic combined model

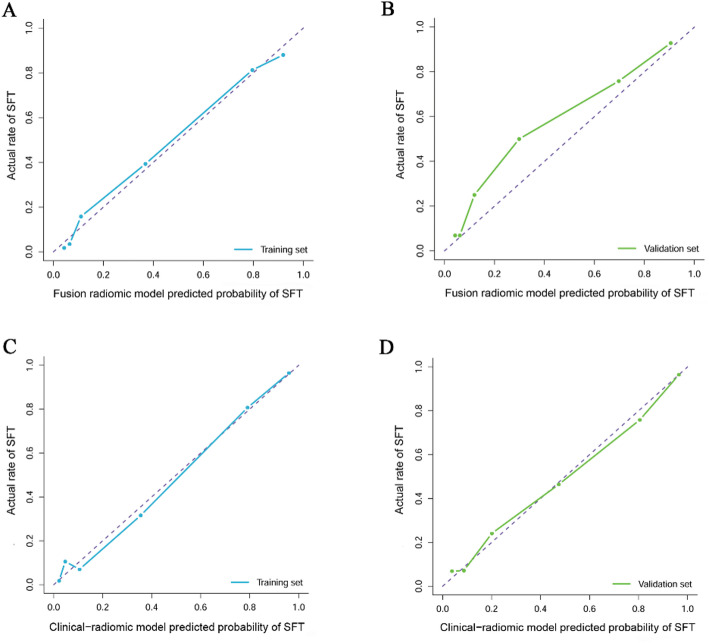

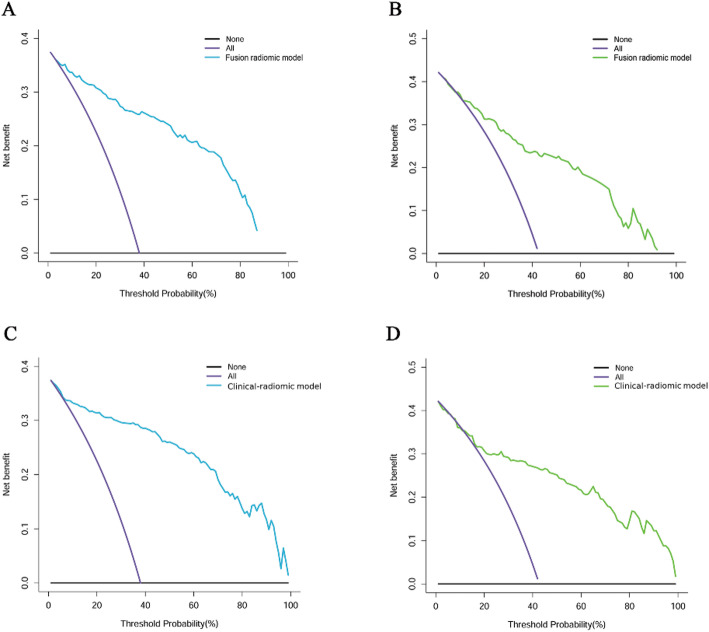

Furthermore, the CCA for the fusion radiomic model exhibited commendable concordance between real-world observations and predictions within the training set (P = 0.355; as illustrated in Fig. 4A). However, discrepancies arose between the actual observed values and the predictions generated by the fusion radiomic model in the validation set (P = 0.025; depicted in Fig. 4B). The DCA for the fusion radiomic model can be observed in Figs. 5A-B. Evidently, the fusion radiomic model yielded a tangible advantage over the alternative approaches, surpassing a threshold probability of > 3% in the training set and > 9% in the validation set. These findings underscore the practical clinical efficacy of the fusion radiomic model.

Fig. 4.

Calibration curve analysis for the fusion radiomic model (A: training set, B: validation set) and clinical-radiomic combined model (C: training set, D: validation set)

Fig. 5.

Decision curve analysis for for the fusion radiomic model (A: training set, B: validation set) and clinical-radiomic combined model (C: training set, D: validation set). The Y-axis measures the net benefit. The blue (A, C: training set) and green (B, D: validation set) line represents the radiomics model. The purple line represents the assumption that all patients were diagnosed as intracranial solitary fibrous tumor (SFT). The black line represents the assumption that all patients diagnosed as atypical meningioma

Calibration curves depict the calibration of model in terms of the agreement between the actual observations and predictions of tumor diagnosis. The Y axis represents the actual rate. The X axis represents the predicted probability. The diagonal purple line represents perfect prediction by an ideal model. The blue (A, C: training set) and green (B, D: validation set) lines represent the performance of the model, of which a closer fit to the diagonal purple line represents a better prediction.

Performance of clinical and clinical-radiomic combined model

In the training dataset, seven carefully chosen clinical features were utilized to formulate a clinical model. Subsequently, the efficacy of this clinical model was validated in a separate validation set. The outcomes revealed AUC values of 0.770 (95% CI, 0.735–0.801) and 0.750 (95% CI, 0.715–0.775) for the training and validation sets, respectively (fig. 2d; Table 5).

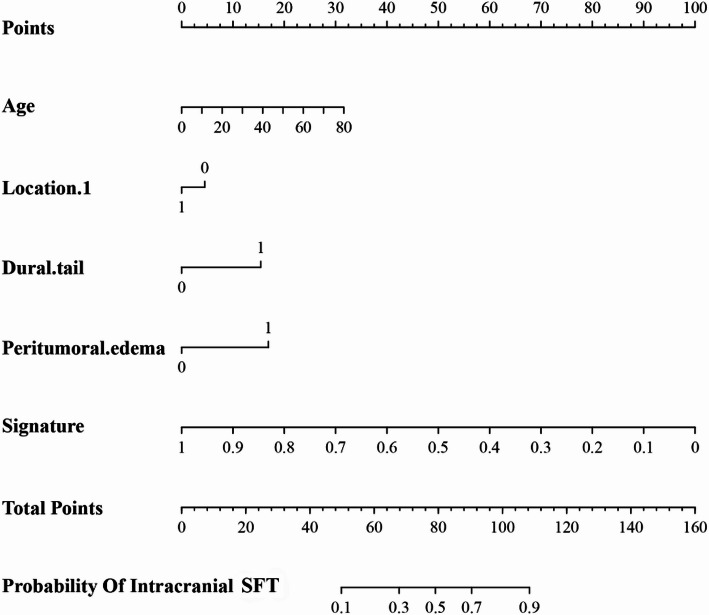

in addition, after screening by aic, four clinical characteristics (including age, location 1, dural tail, peritumoral edema) and signature of fusion radiomic model were determined to establish the clinical-radiomic combined model, yielded an auc of 0.930 (95% ci, 0.911–0.946) in the training set and 0.890 (95% ci, 0.868–0.908) in the validation set (figure. 2e; Table 5). the clinical-radiomic combined model’s predictive accuracy of diagnosis was 0.874 (0.854–0.895) in the training set and 0.819 (0.795–0.842) in the validation set. the detailed predictive indicators of the three aforementioned models are shown in Table 4. bar plots showed the accuracy of clinical-radiomic combined model in the diagnosis of intracranial sft or am (figure. 6). as showed in Figure. 7, the clinical-radiomic combined model is presented as a nomogram.

Fig. 6.

Bar plots for the clinical-radiomic combined model in the training (A) and validation sets (B). The blue histogram above the horizontal axis and the green histogram below the horizontal axis indicate the patients with correct diagnosis of the clinical-radiomic combined model

Fig. 7.

A nomogram derived from the clinical-radiomic combined model. This nomogram is used based on the value of signature of radiomic model and four clinical characteristics, including age, location 1 (supratentorial or infratentorial), dural tail, and peritumoral edema. Draw a vertical line from the corresponding axis of each factor until it reaches the first “Points” line. Next, summarize the points of all risk factors, then draw a vertical line that falls vertically from the “Total Points” axis until it reaches the last axis to the diagnostic probability of intracranial solitary fibrous tumor (SFT)

Calibration and clinical usefulness analysis

The results of the CCA illustrated a strong concordance between the actual observed values and the clinical-radiomic combined model in both the training (P = 0.223; depicted in Fig. 4C) and validation sets (P = 0.674; illustrated in Fig. 4D) for the clinical-radiomic combined model. Moreover, the clinical-radiomic combined model yielded superior net benefits compared to both schemes, surpassing a threshold probability of > 0% for the training set (Fig. 5C) and > 12% for the validation set (Fig. 5D). These results affirm the clinical utility of the clinical-radiomic combined model. Additionally, the decision curve analysis demonstrated enhanced performance for the fusion radiomic model in the realm of clinical applications.

Discussion

In the current investigation, we conducted a retrospective analysis of meticulously curated data from a cohort of patients with intracranial SFT and AMs with histopathological confirmation over the past decade. Employing a radiomic approach based on T2WI and CE-T1WI MRI scans, we aimed to proficiently discern intracranial SFT and AM prior to surgical intervention.

SFT originating within the confines of the central nervous system is an exceedingly uncommon occurrence [5, 25]. Initially categorized as hemangioblastic meningioma, intracranial SFT was subsequently recognized to stem from the epithelial cells of meningeal mesenchymal capillaries rather than meningeal epithelial cells[1]. Typically solitary, intracranial SFT is predominantly associated with the dura mater, often anchoring to the falx or sagittal sinus of the brain, or manifesting within the epidural region [26]. Classified as a malignant tumor of WHO grade II-III, intracranial SFT demonstrates a proclivity for recurrence and metastasis [6]. On the other hand, accounting for 20% of all meningiomas, atypical meningiomas (AMs) are designated as WHO grade II tumors [27]. Notably aggressive, AMs exhibit a 5-year recurrence rate of 40% [28]. While sharing similarities in imaging characteristics, the treatment modalities and prognoses of intracranial SFT and AMs diverge significantly. Intracranial SFT displays heightened aggressiveness, pronounced vascularity, susceptibility to intraoperative hemorrhage, elevated postoperative recurrence rates, and a poorer prognosis [1]. Hence, the precise preoperative diagnosis of intracranial SFT holds paramount importance in the strategic planning of operations and the assessment of prognostic outcomes.

Given the absence of definitive molecular markers, researchers endeavored to leverage preoperative images for the differentiation of intracranial SFT and AM. Intracranial SFT exhibits a spectrum of MRI manifestations, oftentimes irregular or lobulated, showcasing a medley of signals and asymmetric enhancement attributed to cystic degeneration and necrosis [25]. Contrarily, benign meningiomas are characterized by smooth contours, homogenous signals, minimal lobulation, and may exhibit indications of calcification along with a dural tail. Cystic lesions may occur in both benign meningiomas and AM, radiomic research analysis indicate that ADC coefficients are significantly lower in grade II-III tumors. However, the MRI profiles of AMs mirror those of intracranial SFT, featuring asymmetrical signals, erratic lobulation, and an irregular meningeal tail, among others. Consequently, within clinical frameworks, the precise differentiation between AMs and intracranial SFT based solely on conventional imaging modalities proves to be a challenging endeavor [12]. Thus, the exigent call for a potent, precise, and universally adopted tool for the preoperative distinction of AMs and intracranial SFT remains unmet.

Radiomics, grounded in the quantitative classification of high-throughput data extracted from images, serves as a tool for delineating intratumoral heterogeneity [29]. With the evolution of clinical imaging datasets, image-based computational models are assuming an increasingly pivotal role in ensuring the precise diagnosis, characterization, and management of intracranial neoplasms [30]. Within the realm of the central nervous system, radiomics finds manifold applications, encompassing differential and classificatory diagnostics [31], prognostication of molecular details [32], evaluation of therapeutic response, disease progression, and prognostic assessment [17, 33]. The radiomic process unfolds through four key stages, involving image acquisition and reconstruction, delineation of tumor regions of interest (ROIs), extraction and curation of radiomic features, as well as model establishment and validation [30, 34]. Noteworthy studies have harnessed the radiomics methodology to differentiate intracranial SFT from meningioma [12] and angiomatous meningioma [35] in the preoperative phase. However, investigations concerning AMs, which tend to confound with intracranial SFT, currently remain scarce. In this present inquiry, we employ a radiomic approach to discern intracranial SFT from AM prior to surgical intervention.

Within our current investigation, a total of 17 features were meticulously scrutinized, culminating in the development of a fusion radiomic model that exhibited commendable equilibrium in performance across both the training [0.920 (95% CI, 0.898–0.934)] and validation [0.870 (95% CI, 0.849–0.896)] cohorts. Subsequently, a novel clinical-radiomic combined model was crafted, seamlessly integrating the fusion radiomic model with handpicked clinical features, yielding impressive AUC values of 0.930 (95% CI, 0.911–0.946) and 0.890 (95% CI, 0.868–0.908) within the training and validation sets, respectively. Notably, both the fusion radiomic model and the clinical-radiomic combined model showcased exemplary calibration and discriminatory acumen. Furthermore, the user-friendly nature of the clinical-radiomic combined model portends its utility in accurately discerning AM from intracranial SFT prior to surgical interventions.

Historically constrained by the rarity of occurrences, research pertaining to intracranial SFT has encountered limitations. To transcend these confines, we meticulously amassed imaging, clinical, and pathological data from 310 intracranial SFT cases originating from a singular institution for this pioneering radiomic investigation. This invaluable dataset, characterized by its substantial size, augurs well for the production of more robust findings compared to antecedent fragmented case studies.

Despite the significant contributions of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the use of a single-center recruitment strategy may introduce selection bias, highlighting the necessity for future collaborative studies to assess the reproducibility of our clinical-radiomic combined model. Additionally, due to the indolent nature of SFTs, prognostic correlations necessitate prospective validation, making it essential to conduct further studies to confirm the model’s efficacy and robustness. The tumor diagnoses included in this research were based on the time of diagnosis and were validated according to the 2021 WHO diagnostic criteria; however, these criteria are subject to updates over time, and the evolving classification system will require future validation. Finally, the variability in methodologies within the field of radiomics, which includes diverse approaches to feature extraction, selection, and model development, suggests that further refinement could improve the outcomes of subsequent investigations.

Conclusions

Preoperative identification of AM and intracranial SFT can greatly assist clinicians in decision making, surgical planning and potentially improve prognostic outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first application of radiomic-based artificial intelligence methods that integrate radiomic features with clinical characteristics to effectively differentiate between AM and intracranial SFT. The clinical-radiomic combined model incorporating the fusion radiomic model and four clinical characteristics showed great performance and high sensitivity in the differential diagnosis of AM and intracranial SFT, and to assist in the development of individualized treatment of patients with AM and intracranial SFT.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors provided contributions to study conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the article, or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yanghua Fan and Panpan Liu. Liang Wang and Junting Zhang revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Zhen Wu and Yanghua Fan take final responsibility for this article.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 82102144), Clinical Science Research Fund of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College (23LHHGYMP07), and National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0112500) .

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The need for patients’ informed consent was waved. All investigations conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and were performed with permission by the responsible Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Tiantan Hospital.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Yanghua Fan and Panpan Liu contributed equally to this work. Correspondence: Zhen Wu (wz_ttyy@163.com) and (fanyanghua1992@163.com)

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yanghua Fan, Email: fanyanghua1992@163.com.

Zhen Wu, Email: wz_ttyy@163.com.

References

- 1.Cohen-Inbar O. Nervous system Hemangiopericytoma. Can J Neurol Sci 2019: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:1231–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gubian A, Ganau M, Cebula H, Todeschi J, Scibilia A, Noel G, et al. Intracranial solitary fibrous tumors: A heterogeneous entity with an uncertain clinical behavior. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:e48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gritsch S, Batchelor TT, Gonzalez Castro LN. Diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic implications of the 2021 world health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer. 2022;128:47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Y, Gu F, Luo YL, Li SG, Jia XF, Gu LX, et al. The role of tumor parenchyma and brain cortex signal intensity ratio in differentiating solitary fibrous tumors and meningiomas. Discov Oncol. 2024;15:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 world health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan AA, Ahuja S, Mankotia DS, Zaheer S. Intracranial solitary fibrous tumors: clinical, radiological, and histopathological insights along with review of literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;260:155456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiariti M, Goetz P, El-Maghraby H, Tailor J, Kitchen N. Hemangiopericytoma: long-term outcome revisited. Clinical Article. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Deng W, Sun P. Effect of different treatments for intracranial solitary fibrous tumors: retrospective analysis of 31 patients. World Neurosurg. 2022;166:e60–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutkowski MJ, Jian BJ, Bloch O, Chen C, Sughrue ME, Tihan T, et al. Intracranial hemangiopericytoma: clinical experience and treatment considerations in a modern series of 40 adult patients. Cancer. 2012;118:1628–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu W, Shi JX, Cheng HL, Wang HD, Hang CH, Shi QL, et al. Hemangiopericytomas in the central nervous system. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:519–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei J, Li L, Han Y, Gu D, Chen Q, Wang J, et al. Accurate preoperative distinction of intracranial Hemangiopericytoma from meningioma using a multihabitat and Multisequence-Based radiomics diagnostic technique. Front Oncol. 2020;10:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, de Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the Bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:749–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan L, Wu Y, Wu S, Zhang C, Zhu X. Preoperative discrimination of invasive and non-invasive breast cancer using machine learning based on automated breast volume scanning (ABVS) radiomics and virtual touch quantification (VTQ). Discov Oncol. 2024;15:565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan Y, Huo X, Li X, Wang L, Wu Z. Non-invasive preoperative imaging differential diagnosis of pineal region tumor: A novel developed and validated multiparametric MRI-based clinicoradiomic model. Radiother Oncol. 2022;167:277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu FY, Sun YF, Yin XP, Zhang Y, Xing LH, Ma ZP, et al. Using machine learning-based radiomics to differentiate between glioma and solitary brain metastasis from lung cancer and its subtypes. Discov Oncol. 2023;14:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan Y, Guo S, Tao C, Fang H, Mou A, Feng M, et al. Noninvasive radiomics approach predicts dopamine agonists treatment response in patients with prolactinoma: A multicenter study. Acad Radiol. 2025;32:612–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alghamdi M, Li H, Olivotto I, Easaw J, Kelly J, Nordal R, et al. Atypical meningioma: referral patterns, treatment and adherence to guidelines. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44:283–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner CP, McLay J, Hermans IF, Correia J, Bok A, Mehrabi N, et al. Tumour infiltrating lymphocyte density differs by meningioma type and is associated with prognosis in atypical meningioma. Pathology. 2022;54:417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Griethuysen JJM, Fedorov A, Parmar C, Hosny A, Aucoin N, Narayan V, et al. Computational radiomics system to Decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e104–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Q, Li Q, Mi R, Ye H, Zhang H, Chen B, et al. Radiomics nomogram Building from multiparametric MRI to predict grade in patients with glioma: A cohort study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erturk SM. Receiver operating characteristic analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W784. author reply W785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan W. Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57:120–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Elkin EB, Gonen M. Extensions to decision curve analysis, a novel method for evaluating diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2008;8:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F, Cai B, Du Y, Huang Y. Diagnosis and treatment of Hemangiopericytoma in the central nervous system. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14:1578–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melone AG, D’Elia A, Santoro F, Salvati M, Delfini R, Cantore G, et al. Intracranial hemangiopericytoma–our experience in 30 years: a series of 43 cases and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2014;81:556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaher A, Abdelbari Mattar M, Zayed DH, Ellatif RA, Ashamallah SA. Atypical meningioma: a study of prognostic factors. World Neurosurg. 2013;80:549–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T, Horowitz PM, James CD, Lukas RV. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol. 2018;14:2161–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Angelis R, Casale R, Coquelet N, Ikhlef S, Mokhtari A, Simoni P, et al. The impact of radiomics in the management of soft tissue sarcoma. Discov Oncol. 2024;15:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan Y, Feng M, Wang R. Application of radiomics in central nervous system diseases: a systematic literature review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;187:105565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fotouhi M, Shahbandi A, Mehr FSK, Shahla MM, Nouredini SM, Kankam SB, et al. Application of radiomics for diagnosis, subtyping, and prognostication of medulloblastomas: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2024;47:827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan X, Li J, Huang B, Lu H, Lu C, Pan M, et al. Noninvasive radiomics model reveals macrophage infiltration in glioma. Cancer Lett. 2023;573:216380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Xu W, Fei Y, Wu M, Yuan J, Qiu L, et al. A MRI-based radiomics model for predicting the response to Anlotinb combined with Temozolomide in recurrent malignant glioma patients. Discov Oncol. 2023;14:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao B, Fan Y, Zhang Z, Tan Z, Yang H, Tu W, et al. Three-Dimensional radiomics features from Multi-Parameter MRI combined with clinical characteristics predict postoperative cerebral edema exacerbation in patients with meningioma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:625220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Lu Y, Xiong J, Wang D, She D, Kuai X, et al. Presurgical differentiation between malignant haemangiopericytoma and angiomatous meningioma by a radiomics approach based on texture analysis. J Neuroradiol. 2019;46:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.