Abstract

Iron (Fe) is essential for normal plant growth and development. In rice, Fe deficiency leads to stunted growth, leaf chlorosis, reduced photosynthetic capacity, and ultimately, yield loss. Most studies have focused on investigating the mechanisms of Fe deficiency responses in rice roots; however, the effects of shoot Fe redistribution on Fe deficiency response remain poorly understood. Phloem transport plays a vital role in distributing Fe to new tissues. To investigate the effects of enhanced phloem-mediated Fe transport on rice adaptability to iron deficiency, we subjected transgenic lines with higher phloem Fe efflux rates and wild-type (WT) plants to Fe-deficient conditions. The growth, leaf photosynthetic rate, and Fe content of transgenic and WT seedlings under different Fe concentrations were compared. The results showed that the transgenic lines exhibited elevated shoot length, root length, shoot dry weight, leaf chlorophyll content, and net photosynthetic rates under Fe-deficient conditions. Under both Fe-sufficient and Fe-deficient conditions, the transgenic lines had significantly higher Fe content, Fe accumulation, and phloem Fe efflux rates than the WT. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed that enhanced Fe transport via phloem resulted in improved Fe availability through the sequestration of Fe ions and vacuolar transport pathways in the shoots. It also upregulated the EARLY LESION LEAF 1 (ELL1) expression and modulated the sucrose synthase activity, thereby promoting chlorophyll synthesis and leaf photosynthesis. Additionally, enhanced Fe transport influenced the gibberellin (GA) catabolism and plant hormone signal transduction in the roots, reducing the GA content and modulating the cytokinin (CTK), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ETH) signaling to induce Fe deficiency response and promote Fe uptake. These findings demonstrate that phloem-mediated Fe transport participated in Fe deficiency response, and enhancing this improved the adaptability of rice seedlings to low Fe conditions. In specific, rice seedlings with a high capacity for phloem-mediated Fe transport exhibited a strong iron uptake, translocation, and remobilization capacity, thereby maintaining normal growth and development and successfully adapting to the low-Fe environment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12284-025-00816-1.

Keywords: Rice (Oryza Sativa L.), Iron Deficiency, Phloem, Iron transport, Plant hormone signal transduction

Background

Iron (Fe), an essential micronutrient for plant growth and development, serves as a critical cofactor for numerous enzymes and participates in the synthesis of the chlorophyll precursor δ-aminolevulinic acid (Riaz and Guerinot 2021). Under Fe-deficient conditions, rice seedlings exhibit inhibited growth, resulting in decreased plant height, root length, and root and shoot dry weights (Chen et al. 2018b), as well as leaf chlorosis characterized by reduced chlorophyll content, disrupted chloroplast structure, and significantly low net photosynthetic rate (Chen et al. 2018a). Compared to rice grown in Fe-sufficient soils, those cultivated in Fe-deficient soils exhibit reduced plant height, fewer tillers, delayed flowering, and lower grain weight and seed-setting rate, ultimately resulting in significantly lower yield (Sakariyawo et al. 2020). Rice plants at the early growth stage are more susceptible to Fe deficiency than those at the later stage (Mori et al. 1991). Therefore, investigating the mechanisms underlying Fe deficiency responses and enhancing tolerance to Fe deficiency are vital for improved rice production.

Promoting Fe uptake in the roots is a critical strategy for Fe deficiency responses in rice. Fe in the soil predominantly exists in insoluble forms, such as oxides or hydroxides, which limit its bioavailability. Deoxymugineic acid (DMA) is a highly efficient phytosiderophore that chelates Fe(III) (Takagi 1976). The expression of genes encoding key enzymes for DMA synthesis, including nicotianamine synthase (NAS), nicotianamine aminotransferase (NAAT), and DMA synthase (DMAS), is upregulated under Fe-deficient conditions, thereby promoting DMA synthesis in the roots (Inoue et al. 2003, 2008; Bashir et al. 2006). The expression of TRANSPORTER OF MUGINEIC ACID FAMILY PHYTOSIDEROPHORES 1 (OsTOM1), which encodes the transporter responsible for DMA efflux, is also induced under Fe-deficient conditions (Nozoye et al. 2011). Hence, increased Fe availability in the rhizosphere can be achieved by promoting DMA synthesis and secretion. Rice employs a dual strategy for Fe acquisition from the soil. One strategy involves the direct absorption of free Fe(II) through IRON-REGULATED TRANSPORTER 1 (OsIRT1). Another strategy involves the secretion of DMA to chelate Fe(III) and form the Fe(III)-DMA complex, which is taken up by YELLOW STRIPE-LIKE 15 (OsYSL15). Notably, OsIRT1 and OsYSL15 expression in the roots is significantly upregulated under Fe-deficient conditions (Ishimaru et al. 2006; Inoue et al. 2009). Overall, rice responds to Fe deficiency by increasing Fe availability in the rhizosphere and enhancing Fe absorption capacity in the roots.

Mobilizing and redistributing internally stored Fe are essential to cope with Fe deficiency. In plants, ferritin (FER) is known as a cellular Fe sink that can accommodate up to 4500 Fe atoms (Briat et al. 2010). In addition to FER, vacuoles are responsible for Fe storage. The vacuole iron transporter (VIT) is responsible for transporting excess Fe from the cytoplasm to the vacuoles (Kim et al. 2006). Rice can utilize Fe more efficiently by regulating Fe transport between the cytoplasm and vacuole, in which natural resistance-associated macrophage (NRAMP) plays an important role in transporting stored Fe from the vacuoles (Lanquar et al. 2005). Although Fe has poor mobility, Fe deficiency can promote Fe translocation from the roots to the shoots and alter Fe distribution (Tsukamoto et al. 2009; Che et al. 2021). Under Fe-deficient conditions, both OsIRT1 and OsNAS are highly expressed in the shoot phloem, suggesting that OsIRT1 may also function in long-distance Fe transport within the shoots (Inoue et al. 2003; Ishimaru et al. 2006). Among the rice YSL family members that participate in Fe distribution, the expression of OsYSL2, OsYSL9, and OsYSL15 in the leaves is induced by Fe deficiency (Koike et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2009; Senoura et al. 2017). Generally, Fe(III)-DMA and Fe(II)-NA are the main forms of Fe transported in the shoots (Nishiyama et al. 2012). However, only OsYSL9 exhibited both Fe(II)-NA and Fe(III)-DMA transport activities, suggesting its significant role in Fe transport within rice shoots. Senoura et al. (2017) found that under Fe-sufficient conditions, the growth phenotype of OsYSL9-knockdown rice was not significantly different from that of non-transgenic plants. Compared to non-transgenic rice, the plant height, SPAD value of new leaves, and Fe content in the leaves of OsYSL9-knockdown plants were significantly decreased under Fe-deficient conditions. These results indicate that the downregulation of OsYSL9 improves sensitivity to Fe deficiency, suggesting that OsYSL9 may have crucial functions in Fe deficiency response. Under Fe-deficient conditions, the expression of genes involved in Fe transport, including OsYSL9, OsIRT1, and OsNAS, was detected in phloem cells, suggesting that phloem-mediated Fe transport may be important for Fe deficiency response.

Due to poor Fe mobility, new leaves are more prone to chlorosis than mature leaves under Fe-deficient conditions. For instance, barley can enhance Fe-deficiency tolerance by accelerating the senescence of lower leaves and promoting Fe re-translocation from old to new leaves, thereby reducing the negative impact of chlorosis in new leaves (Hirai et al. 2007; Higuchi et al. 2011). By contrast, the capacity for Fe remobilization in rice was weaker than that in barley, as evidenced by the significantly reduced SPAD values in new rice leaves even when root Fe uptake is enhanced under Fe-deficient conditions (Maruyama et al. 2005). These results imply that the promotion of Fe distribution and re-translocation to new leaves may contribute to Fe deficiency response in rice. Phloem is an important route for iron translocation. Tsukamoto et al. (2009) found that 52Fe translocation from the roots to the mature leaves was not affected, whereas new leaves were reduced after steam treatment, suggesting that the phloem route is essential for Fe distribution in new leaves. Previous studies have reported that the expression of iron acquisition genes in roots is regulated by phloem iron (or some signal derived from the phloem), rather than the total iron content in the roots (Lucena et al. 2006; García et al. 2011). In dicotyledonous plants, the iron content of the phloem sap can reflect the iron content of the leaves, and the capacity of phloem iron transport can influence the iron deficiency response in roots (Maas et al. 1988). These results demonstrated that phloem iron transport contributes to Fe deficiency response. However, the role of phloem-mediated iron transport in the regulation of the Fe deficiency response in rice remains unclear. In addition, Fe deficiency signals, such as nitric oxide (NO) and sucrose, generated in the shoots are also transmitted to the roots through the phloem, facilitating shoot-to-root communication (Chen et al. 2018a; García et al. 2013), which also indicates that phloem transport plays an important role in the iron deficiency response. Therefore, we speculate that phloem-mediated Fe transport may be a critical component of the regulatory mechanism for Fe deficiency responses in rice.

In this study, we selected two transgenic rice lines with enhanced phloem-mediated Fe transport capacities as the experimental materials (Fig. S1). To investigate the effects of enhanced Fe transport via phloem on rice seedlings in response to Fe deficiency, we compared the growth, chlorophyll content, and Fe status between transgenic and wild-type seedlings after treatment with 40 (Fe-sufficient) and 10 µM (Fe-deficient) Fe. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed key cellular and regulatory pathways that were altered in the leaves and roots under different Fe concentrations. We validated the expression of selected genes using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and determined the related metabolite levels. Our results will expand the understanding of plant responses to Fe deficiency and provide new insights into improving rice growth under Fe-deficient conditions.

Results

Effect of Enhancing Phloem Fe Transport on Plant Growth Under Different Fe Concentration Treatments

The transgenic lines pOsSUT1::OsYSL9 (SY) and pOsSUT1::OsIRT1 (SI) demonstrated enhanced phloem-mediated iron transport capacity. Compared to wild-type (WT) plants, SY lines exhibited higher grain iron content, grain weight, number of primary branches, and net photosynthetic rate. Similarly, SI lines also showed superior performance in multiple agronomic traits, including elevated grain iron content, higher grain number per panicle and grain weight, increased primary and secondary branches, and enhanced photosynthetic efficiency. These yield and grain quality traits displayed consistent trends in different SY lines, as did in different SI lines (unpublished data). In this study, the most outstanding performing lines pOsSUT1::OsYSL9 line 3 (SY-3), and pOsSUT1::OsIRT1 line 4 (SI-4) were used for investigation.

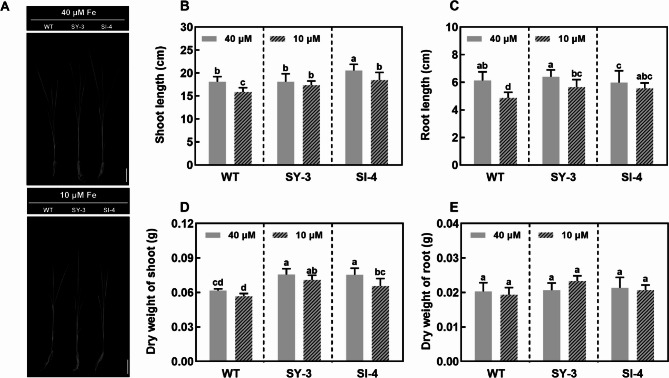

The plant growth of Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4 was significantly inhibited at 7 DAT (Fig. 1A). Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the shoot lengths of Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4 decreased by 12.5, 4.1, and 10.2%, respectively, whereas the root lengths decreased by 20.8, 11.7, and 7.2%, respectively (Fig. 1B, C). Fe deficiency also reduced the shoot dry weight but had no significant effect on the root dry weight (Fig. 1D, E). Furthermore, the shoot dry weights of SY-3 and SI-4 were significantly higher than those of the WT in both treatment groups. These results suggest that enhanced phloem-mediated Fe transport is beneficial to plant growth and promotes dry matter accumulation in Fe-deficient shoots.

Fig. 1.

Seedling growth of wild-type (WT) and transgenic pOsSUT1::OsYSL9 line 3 (SY-3) and pOsSUT1::OsIRT1 line 4 (SI-4) rice at 7 days after treatment (DAT) with 10 and 40 µM iron (Fe). A Photograph of seedlings. Scale bar = 1 cm. Shoot (B) and root (C) lengths (n = 10 replicates). Dry weight of the shoots (D) and roots (E) (n = 3 replicates). Data are presented as means ± SD. Different letters indicate significance based on Duncan’s test (P < 0.05)

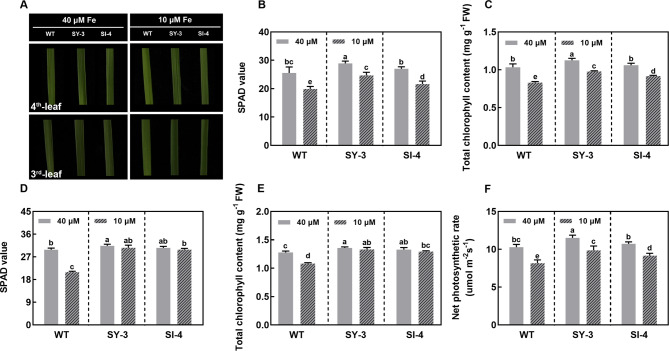

Effect of Enhancing Phloem Fe Transport on Leaf Color and Photosynthesis Under Different Fe Concentration Treatments

At 7 DAT, the Fe-deficient conditions induced noticeable changes in the leaf color of new and mature leaves (Fig. 2A). Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the SPAD values were significantly lower in the new leaves of Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4, with 22.07, 14.60, and 19.85% reductions, respectively (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the total chlorophyll content of new leaves was significantly decreased in the Fe-deficient group, with reductions of 19.72, 13.00, and 13.47% in the WT, SY-3, and SI-4, respectively (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Leaf chlorophyll contents and photosynthetic rates in wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice at 7 days after treatment (DAT) with 10 and 40 µM iron (Fe). A Photograph of leaf color. SPAD values (B) and total chlorophyll contents (C) of the 4th leaves. SPAD values (D) and total chlorophyll contents (E) of the 3rd leaves. F Net photosynthetic rate of the 3rd leaves. Data in B, D and F represent the means ± SD of five replicates. Data in C and E represent the means ± SD of four replicates. Different letters indicate significance based on Duncan’s test (P < 0.05)

Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the SPAD value and total chlorophyll content of mature leaves in the WT were significantly decreased by 29.83 and 15.19%, respectively (Fig. 2D and E). By contrast, no significant changes in the SPAD value or total chlorophyll content were observed in the mature leaves of SY-3 and SI-4 in both groups. However, the net photosynthetic rate in the mature leaves was significantly reduced in the Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4, with 20.62, 14.26, and 14.55% reductions, respectively (Fig. 2F). This indicates that Fe deficiency significantly affects the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic capacity of rice leaves. Notably, Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 exhibited significantly higher chlorophyll contents and net photosynthetic rates than Fe-deficient WT, suggesting that rice with enhanced phloem-mediated Fe transport has better adaptability to Fe deficiency.

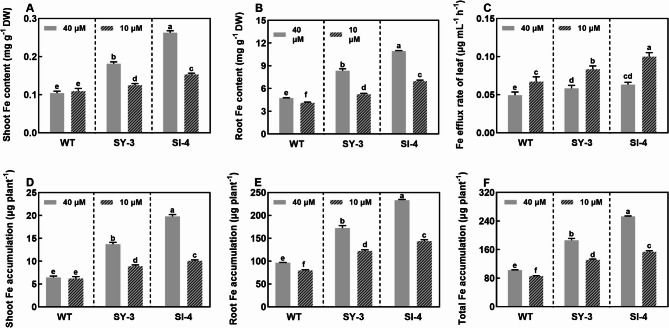

Effect of Enhancing Phloem Fe Transport on Plant Fe Status Under Different Fe Concentration Treatments

In the Fe-sufficient group, the Fe contents in the shoots were 1.7 and 2.5 times higher in SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT, respectively (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the Fe contents in the roots were 1.8 and 2.3 times higher in SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT, respectively (Fig. 3B). Notably, the Fe contents of Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 were significantly higher than that of Fe-sufficient WT, indicating better Fe uptake in SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT. The Fe content in Fe-deficient WT shoots showed no significant difference to that of Fe-sufficient WT. However, the Fe contents in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 shoots significantly decreased, with 31.0 and 41.6% reductions, respectively (Fig. 3A). Fe deficiency also significantly reduced the Fe contents in the WT, SY-3, and SI-4 roots by 13.1, 37.1, and 36.4%, respectively (Fig. 3B). At different Fe concentrations, the Fe transport rate in the phloem of mature SY-3 and SI-4 leaves was significantly higher than that in the WT. Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the Fe efflux rates in the phloem of Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4 mature leaves increased by 36.1, 42.9, and 58.1%, respectively (Fig. 3C). This suggests that the Fe transport capacity in the phloem of SY-3 and SI-4 leaves was higher than that in the WT.

Fig. 3.

Iron status in wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice at 7 days after treatment (DAT) with 10 and 40 µM iron (Fe). Fe content in the shoots (A) and roots (B). C Fe efflux rate of the leaf phloem at 3 DAT (n = 4 replicates). Fe accumulation in the shoots (D), roots (E), and whole plants (F). Data in A, B, D, E, and F represent the means ± SD of three replicates. Different letters indicate significance based on Duncan’s test (P < 0.05)

At different Fe concentrations, Fe accumulation in the shoots and roots of SY-3 and SI-4 was also significantly higher than that in the WT. Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the Fe accumulation in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4 shoots was reduced by 3.6, 35.3, and 49.1%, respectively, and with 17.4, 29.0, and 38.4% reductions in the roots, respectively (Fig. 3D, E). By contrast, total Fe accumulation in Fe-sufficient SY-3 and SI-4 seedlings was 1.8 and 2.5 times that in the WT, respectively (Fig. 3F). Similarly, total Fe accumulation in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 seedlings was 1.5 and 1.8 times that in the WT, respectively. These results show that the Fe contents in SY-3 and SI-4 were higher than that in the WT in both treatment groups. Additionally, the Fe contents in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 were significantly higher than that in Fe-sufficient WT. Therefore, enhancing phloem-mediated Fe transport may improve the adaptability of rice to Fe deficiency, potentially by increasing the threshold for Fe uptake and accumulation during stress response.

Effects of Enhancing Phloem Fe Transport on the Expression of Genes in Rice Leaves Under Different Fe Concentration Treatments

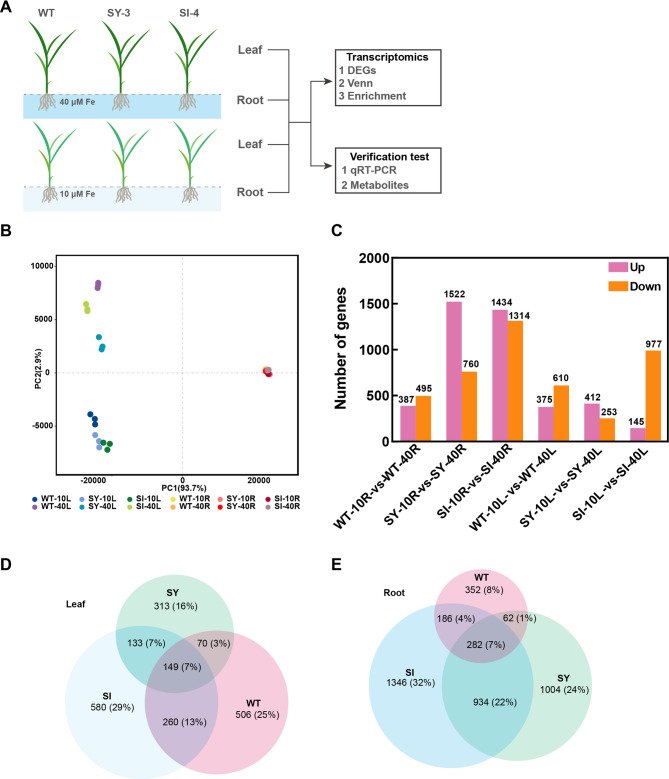

RNA-seq analysis of the mature leaves and roots from treated WT, SY-3, and SI-4 was performed to investigate the changes in gene expression in response to different Fe concentrations (Fig. 4A). For the leaves, the PCA results showed that each group was distinctly separate, with samples from the same group clustered together (Fig. 4B). The gene expression patterns in the WT, SY-3, and SI-4 leaves were significantly different between the Fe-sufficient and Fe-deficient treatments. For the roots, samples from the same group were closely grouped together, and the gene expression patterns in the WT, SY-3, and SI-4 were relatively similar under different Fe concentrations. There were 985, 665, and 1122 DEGs identified in the WT, SY-3, and SI-4 leaves, respectively (Fig. 4C). Among the Fe deficiency-responsive DEGs, 149 were common to the WT, SY-3, and SI-4, whereas 260 were unique to SY-3 and SI-4 (Fig. 4D). In the roots, 882, 2282, and 2748 DEGs were identified in the WT, SY-3, and SI-4, respectively (Fig. 4C). Among the Fe deficiency-responsive DEGs, 282 were common to the WT, SY-3, and SI-4, whereas 934 were unique to SY-3 and SI-4 (Fig. 4E). Overall, the number of DEGs was higher in the roots than in the leaves. Additionally, the number of DEGs in SY-3 and SI-4 roots was higher compared to the WT.

Fig. 4.

RNA sequencing analysis of the leaves (L) and roots (R) from wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice after treatment with 10 and 40 µM iron (Fe). A Diagram of the experimental setup. B Principal component analysis of identified genes. C Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the leaves and roots per treatment. Up, upregulated; Down, downregulated. Venn diagrams of DEGs in the leaves (D) and roots (E)

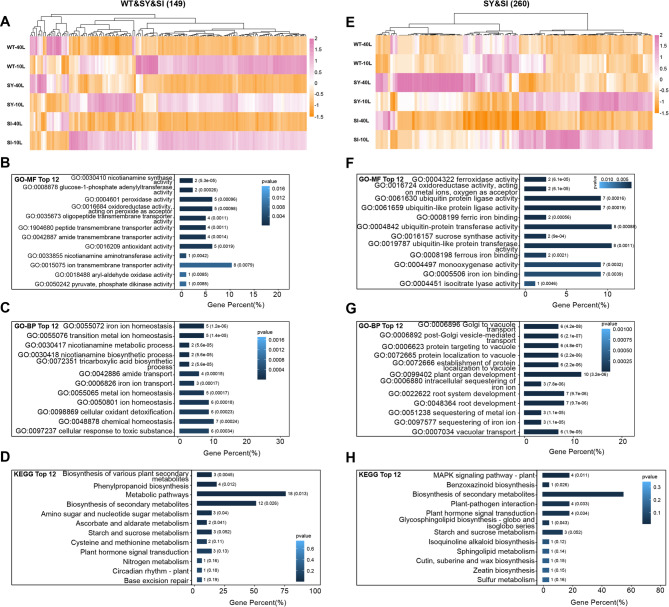

Hierarchical clustering of the 149 common leaf-specific DEGs showed that the expression patterns were similar across the three genotypes (Fig. 5A). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses indicated that these were primarily involved in ‘iron ion homeostasis’, ‘ion transmembrane transporter activity’, ‘nicotianamine synthase activity’, ‘starch and sucrose metabolism’, and ‘plant hormone signal transduction’ (Fig. 5B–D). Hierarchical clustering of the 260 unique leaf-specific DEGs revealed highly similar expression patterns between SY-3 and SI-4, which were markedly different from those in the WT (Fig. 5E). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed that these were mainly associated with ‘sequestering of iron ion’, ‘vacuolar transport’, ‘iron ion binding’, ‘sucrose synthase activity’, and ‘plant hormone signal transduction’ (Fig. 5F–H).

Fig. 5.

Functional analysis of leaf-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to iron deficiency. Hierarchical clustering (A) and KEGG (B), GO-MF (C), and GO-BP (D) enrichment analyses of 149 DEGs common to the wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4. Hierarchical clustering (E) and KEGG (F), GO-MF (G), and GO-BP (H) enrichment analyses of 260 DEGs unique to SY-3 and SI-4

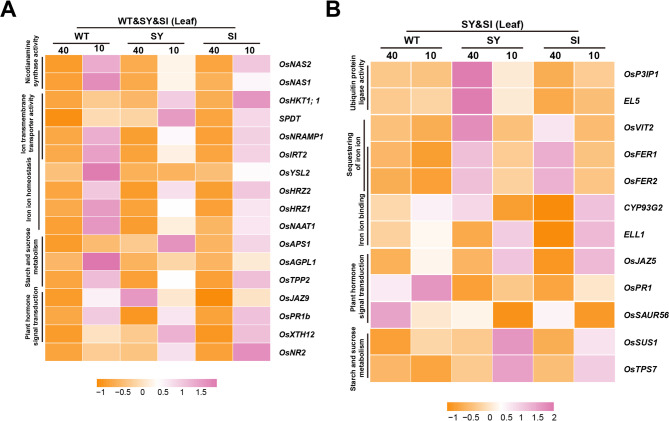

Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the expression of genes involved in ‘iron ion homeostasis’ and ‘nicotianamine synthase activity’ was upregulated in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3 and SI-4 leaves, showing consistent trends (Fig. 6A). In SY-3 and SI-4 leaves, the expressions of genes involved in ‘iron ion binding’ ‘plant hormone signal transduction’, ‘starch and sucrose metabolism’, and ‘iron ion sequestration’ showed significant changes (Fig. 6B). By contrast, no significant changes in the expression of the same genes were observed in both Fe-sufficient and Fe-deficient WT. Notably, the qPCR results were consistent with the RNA-seq data. Compared to Fe-sufficient plants, the expression levels of NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 1 (OsNAS1), OsNAS2, NICOTIANAMINE AMINOTRANSFERASE 1 (OsNAAT1), OsYSL2, OsIRT2, and NATURAL RESISTANCE-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE 1 (OsNRAMP1) in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3 and SI-4 leaves were significantly upregulated (Fig. S2). VACUOLAR IRON TRANSPORTER 2 (OsVIT2), OsFER1, and OsFER2 expression levels in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 leaves were downregulated compared to Fe-sufficient plants (Fig. 7A–C). Conversely, SUCROSE SYNTHASE 1 (OsSUS1), TREHALOSE-6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 7 (OsTPS7), and EARLY LESION LEAF 1 (ELL1) expression levels were upregulated in Fe-deficient plants (Fig. 7D–F), with significantly higher expression in SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT.

Fig. 6.

Key leaf-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with iron deficiency response in wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice. A Heat map of key DEGs associated with ‘plant hormone signal transduction’, ‘starch and sucrose metabolism’, ‘iron ion homeostasis’, ‘ion transmembrane transporter activity’, and ‘iron ion binding’. B Heat map of key DEGs unique to SY-3 and SI-4 and associated with ‘starch and sucrose metabolism’, ‘plant hormone signal transduction’, ‘iron ion binding’, ‘sequestering of iron ion’, and ‘ubiquitin protein ligase activity’. Data represent the means of three replicates

Fig. 7.

Expression validation of iron deficiency response genes in the leaves of wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice. Relative expression of OsVIT2 (A), OsFER1 (B), OsFER2 (C), OsSUS1 (D), OsTPS7 (E), and ELL1 (F). Data represent the means ± SD of three replicates. Different letters indicate significance based on Duncan’s test (P < 0.05)

Effects of Enhancing Phloem Fe Transport on the Expression of Genes in Rice Roots Under Different Fe Concentration Treatments

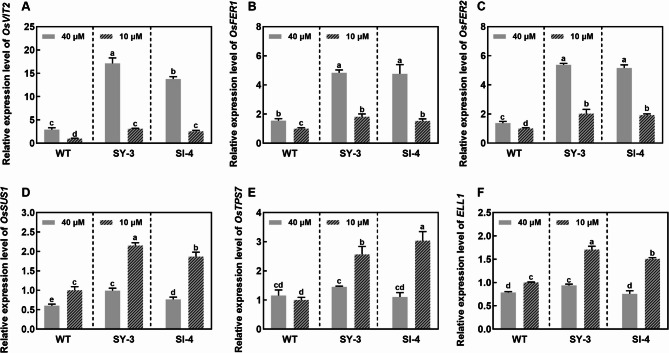

Hierarchical clustering of the 282 common root-specific DEGs showed similar expression patterns across the three genotypes (Fig. 8A). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses indicated that these were primarily involved in ‘transmembrane transporter activity’, ‘nicotianamine synthase activity’, and ‘iron ion binding’ (Fig. 8B–D). Hierarchical clustering of the 934 unique root-specific DEGs revealed highly similar expression patterns between SY-3 and SI-4, which distinctly varied from those in the WT (Fig. 8E). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses suggested that these were mainly associated with ‘plant hormone signal transduction’, ‘ion binding’, ‘response to stimulus’, and ‘gibberellin catabolic’ (Fig. 8F–H).

Fig. 8.

Functional analysis of root-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to iron deficiency. Hierarchical clustering (A) and KEGG (B), GO-MF (C), and GO-BP (D) enrichment analyses of 282 DEGs common to the wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4. Hierarchical clustering (E) and KEGG (F), GO-MF (G), and GO-BP (H) enrichment analyses of 934 DEGs unique to SY-3 and SI-4

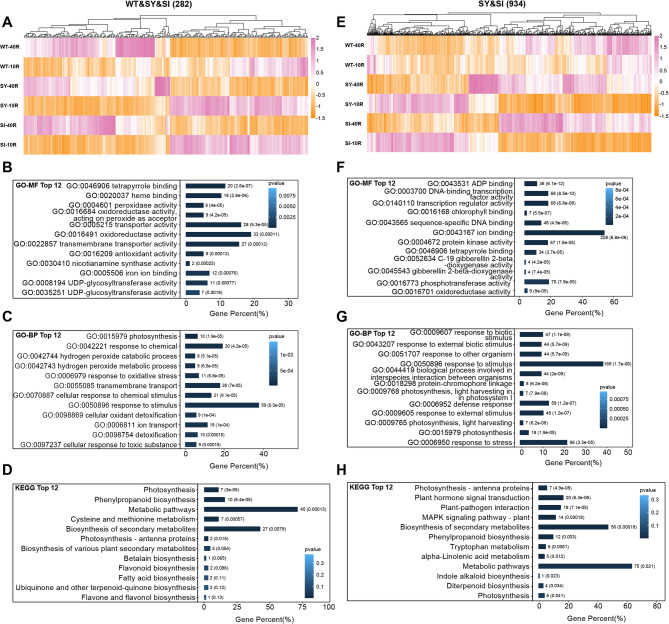

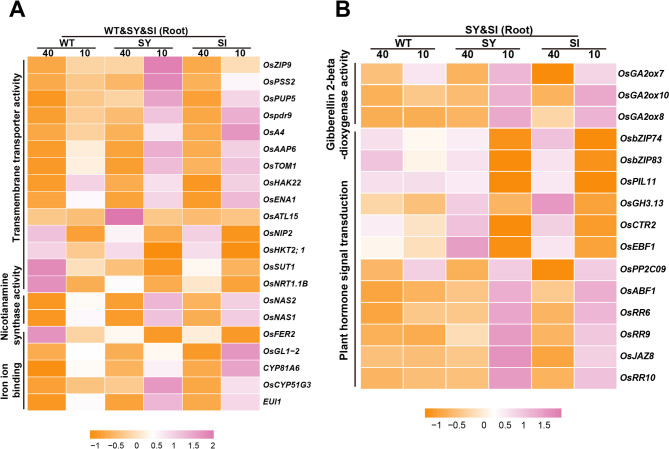

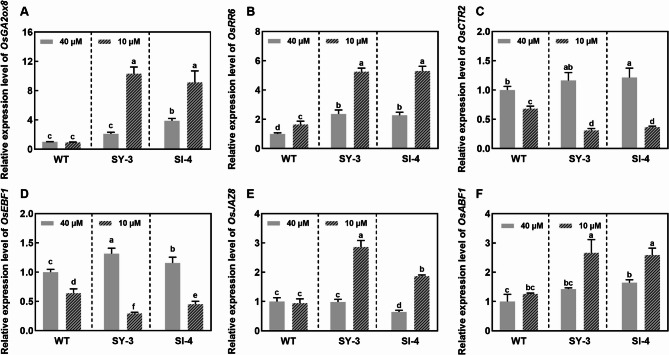

Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the expression of genes associated with ‘transmembrane transporter activity’ and ‘nicotianamine synthase activity’ was significantly upregulated in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3 and SI-4 roots (Fig. 9A). Conversely, OsFER2 expression levels was significantly downregulated in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4 roots. In both treatment groups, the expression of genes involved in ‘gibberellin catabolism’ and ‘plant hormone signal transduction’ showed significant changes in SY-3 and SI-4 roots, whereas those in the WT had no significant changes (Fig. 9B). The qPCR results also corroborated those of the RNA-seq analysis. Compared to Fe-sufficient plants, the expression of OsFER2 was downregulated, while OsNAS1, OsNAS2, OsTOM1, EFFLUX TRANSPORTER OF NA (OsENA1), and ELONGATED UPPERMOST INTERNODE1 (OsEUI1) expression levels were upregulated in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3 and SI-4 roots (Fig. S3). In specific, GIBBERELLIN 2-OXIDASE 8 (OsGA2ox8), A-TYPE RESPONSE REGULATOR 6 (OsRR6), JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN 8 (OsJAZ8), and ABSCISIC ACID-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT-BINDING FACTOR 1 (OsABF1) expression levels in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 roots were higher than those in Fe-sufficient plants, especially compared to the WT (Fig. 10A, B, E, and F). By contrast, CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE 2 (OsCTR2) and EIN3-BINDING F-BOX PROTEIN 1 (OsEBF1) expression levels were downregulated in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 roots (Fig. 10C, D).

Fig. 9.

Key root-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with iron deficiency response in the wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice. A Heat map of key DEGs associated with ‘transmembrane transporter activity’, ‘nicotinamide synthase activity’, and ‘iron ion binding’. B Heat map of key DEGs unique to SY-3 and SI-4 and associated with ‘transmembrane transporter activity’, ‘nicotinamide synthase activity’, and ‘iron ion binding’. Data represent the means of three replicates

Fig. 10.

Expression validation of iron deficiency response genes in the roots of wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice. Relative expression of OsGA2ox8 (A), OsRR6 (B), OsCTR2 (C), OsEBF1 (D), OsJAZ8 (E), and OsABF1 (F). Data represent the means ± SD of three replicates. Different letters indicate significance based on Duncan’s test (P < 0.05)

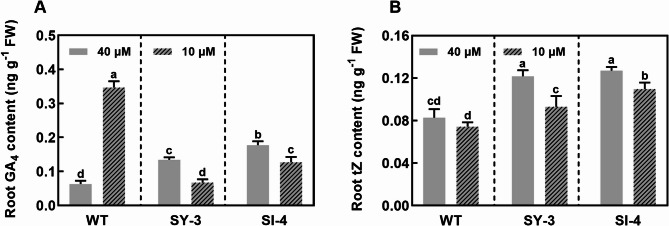

Since, gibberellin 2-beta dioxygenase participates in GA catabolism (Thomas et al. 1999; Hsieh et al. 2021), the GA levels in the roots were measured. The GA4 contents were significantly higher in Fe-sufficient SY-3 and SI-4 roots than in the WT. Compared to Fe-sufficient WT, the GA4 content was significantly increased in Fe-deficient WT roots. However, the GA4 contents in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 roots were significantly lower than that in the WT (Fig. 11A). Based on the RNA-seq results, the expression of genes involved in gibberellin biosynthesis were analyzed, specifically gibberellin 20-oxidase genes (OsGA20oxs) and gibberellin 3-beta hydroxylase genes (OsGA3oxs). Compared to the WT, OsGA20ox1 and OsGA20ox7 expression in Fe-sufficient SY-3 and SI-4 roots was higher, whereas OsGA20ox2, OsGA2ox3, and OsGA3ox2 expression levels were not significantly different. Furthermore, the OsGA20ox2, OsGA2ox3, and OsGA20ox7 expression was upregulated in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4 roots. OsGA20ox1 expression in SY-3 and SI-4 was significantly downregulated under Fe-deficient conditions, whereas that in the WT remained unchanged (Fig. S4). OsRR6 expression is reportedly related to the tZ content (Hirose et al. 2007). In both groups, the tZ contents in SY-3 and SI-4 roots were significantly higher than that in the WT (Fig. 11B). Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, the tZ content in the roots of Fe-deficient plants was reduced.

Fig. 11.

Hormone contents in wild-type (WT) and transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 rice roots after treatment with 10 and 40 µM iron: GA4 (A) and tZ (B). Data represent the means ± SD of three replicates. Different letters indicate significance based on Duncan’s test (P < 0.05)

Discussion

Phloem-Mediated Fe Transport is Critical for Fe Deficiency Response in Rice

Fe plays a vital role in plant growth and development (Guerinot 2001; Curie and Mari 2017). Fe deficiency significantly inhibits chlorophyll biosynthesis and photosynthesis, resulting in yellow young leaves, reduced photosynthetic areas, and decreased dry weight, ultimately affecting crop yield (Roriz et al. 2014; Aksoy et al. 2017). Comparatively, Fe re-translocation from old to young leaves is more efficient in barley than in rice under Fe-deficient conditions (Maruyama et al. 2005). Under Fe-sufficient conditions, the ratio of water-soluble Fe to total Fe in the old and new leaves was nearly identical in barley and rice. Notably, under Fe-deficient conditions, this ratio decreased in rice, particularly in the new leaves, but remained unchanged in barley. Thus, Fe availability is a critical strategy for Fe deficiency response in rice.

The phloem is an important route for transporting nutrients to new leaves. When apple plants suffer from zinc deficiency, higher zinc levels are transported to the phloem (Xie et al. 2019). Similarly, the radioactivity of 52Fe in the phloem is higher in Fe-deficient barley than in Fe-sufficient plants (Tsukamoto et al. 2009). These results indicate that phloem transport participates in nutrient deficiency response. In the present study, we found that Fe deficiency promoted phloem-mediated Fe transport, as evidenced by the significantly elevated Fe efflux rate in the phloem of Fe-deficient rice leaves (Fig. 3C). In addition, the expression levels of the phloem-specific genes OsYSL2, OsNAS1, and OsNAS2 were upregulated in the shoots (Fig. 6A), suggesting that Fe deficiency can promote phloem-mediated Fe transport.

Fe deficiency induces plants to secrete more protons (H+) and phytosiderophores from the roots, enhancing Fe solubility in the rhizosphere and promoting Fe uptake (Kobayashi and Nishizawa 2012). In the WT, SY-3, and SI-4 roots, PLASMA MEMBRANE H+-ATPASE 4 (OsA4), OsNAS1, OsNAS2, and OsTOM1 expression levels were significantly upregulated under Fe-deficient conditions (Fig. 9A). Upregulation of OsA4 promotes proton secretion and increases Fe solubility in the rhizosphere (Santi et al. 2005; Santi and Schmidt 2009). The upregulation of OsNAS1, OsNAS2, and OsTOM1 also enhances DMA synthesis and efflux (Bashir et al. 2006; Nozoye et al. 2011). Notably, this effect was more pronounced in the transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT (Fig. 9A). These results suggest that enhancing phloem-mediated Fe transport improves Fe deficiency response in the roots. Previous studies reported that disrupted phloem-mediated Fe transport affects Fe deficiency responses. In Arabidopsis, AtYSL1 and AtYSL3 are involved in phloem-mediated Fe transport. Although ysl1 and ysl3 single mutants exhibited no obvious phenotypes, the ysl1ysl3 double mutant showed leaf chlorosis. Under Fe-sufficient conditions, the Fe contents were significantly lower in the ysl1ysl3 shoots and roots than in the WT, but the root ferric reductase activity and AtIRT1 expression remained unchanged. Similarly, the root ferric reductase activity and AtIRT1 expression in the ysl1ysl3 were comparable to those in the WT under Fe-deficient conditions. These results indicate that the response of ysl1ysl3 plants to low Fe levels was abnormal because the Fe deficiency response of the roots was not significantly upregulated despite reduced Fe content (Waters et al. 2006). Altogether, these results imply that phloem-mediated Fe transport is important for Fe deficiency response in rice.

Promoting Phloem-Mediated Fe Transport Improves Fe Availability in Fe-Deficient Shoots

In this study, Fe accumulation was significantly higher in the transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT. Moreover, Fe accumulation was significantly higher in the Fe-deficient transgenic lines than in the Fe-sufficient WT (Fig. 3D–F). These results indicate that plants with enhanced phloem-mediated Fe transport have a better Fe uptake capacity. In both treatment groups, OsFER1, OsFER2, and OsVIT2 expression was significantly higher in the leaves of SY-3 and SI-4 than those in the WT (Fig. 7A–C), indicating that SY-3 and SI-4 plants have better Fe storage capacities. Notably, the downregulation of OsFER1, OsFER2, and OsVIT2 expression was more pronounced in the transgenic lines than in the WT under Fe-deficient conditions (Figs. 6B and 7A–C). OsFER1 and OsFER2 play crucial roles in Fe storage and homeostatic regulation, and their downregulation may affect Fe allocation and utilization (Stein et al. 2009). Similarly, OsVIT2 is highly responsive to Fe deficiency. Rice osvit2 mutant plants exhibit decreased Fe accumulation in the leaves and increased Fe levels in the phloem exudates (Zhang et al. 2012), which is consistent with our results (Figs. 3 and 6B). Moreover, the reduced Fe accumulation in transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 shoots was greater than that in the WT (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that enhancing phloem-mediated Fe transport improves Fe availability by altering Fe transport and storage and facilitating Fe remobilization.

Fe availability in plants is closely linked to chlorophyll biosynthesis and chloroplast development (Graziano and Lamattina 2007; Jeong and Guerinot 2009; Saito et al. 2021). In our study, the transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 developed greener leaves under Fe-deficient conditions, with higher SPAD values and total chlorophyll content than the WT (Fig. 2A–E). Leaf color and chlorophyll content are reliable indicators of the Fe status (Hoan et al. 1992; Bashir et al. 2014; Pereira et al. 2014). Under both Fe-sufficient and Fe-deficient conditions, the Fe contents in SY-3 and SI-4 shoots were significantly higher than that in the WT. Fe is also important for chlorophyll synthesis. The high Fe contents in SY-3 and SI-4 may have promoted the chlorophyll biosynthesis (Fig. 3A). Essentially, chloroplast development and function are regulated by ELL1. In rice ell1 mutants, the chlorophyll content decreased and the expression of chloroplast degradation-related genes increased, resulting in serious chloroplast degradation (Cui et al. 2021). ELL1 expression in SY-3 and SI-4 leaves was significantly upregulated under Fe-deficient conditions, with a much higher increase compared to the WT (Figs. 6B and 7F). NO can reportedly influence leaf chlorophyll content (Graziano and Lamattina 2007). Under Fe-sufficient conditions, the leaf chlorophyll content increased after NO treatment. Exogenous NO treatment can also reverse the chlorotic phenotype of maize leaves caused by Fe deficiency or the functional loss of Yellow Stripe 1 (ZmYS1) and ZmYS3 (Graziano et al. 2002). In plants, nitrate reductase (NR) is involved in NO synthesis (Rockel et al. 2002; Gao et al. 2019). In this study, OsNR2 expression in the leaves was higher in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT (Fig. 6A); OsNR2 upregulation may have promoted NO production in the leaves. The chlorophyll content was also higher in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT. These results suggest that enhancing phloem-mediated Fe transport promotes chloroplast development and chlorophyll synthesis by increasing Fe content, upregulating ELL1expression, and inducing NO generation in the leaves (Fig. 12).

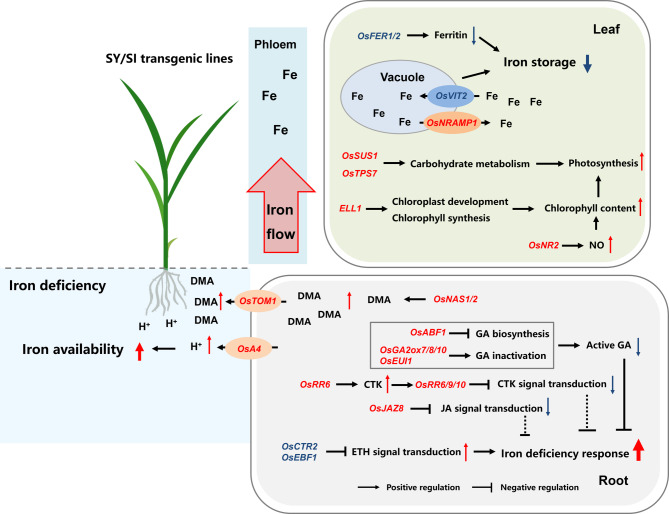

Fig. 12.

Schematic diagram showing the potential mechanism to improve iron (Fe) deficiency tolerance in rice thorough enhanced phloem-mediated Fe transport. Under Fe-deficient conditions, Fe storage in transgenic SY and SI leaves is reduced by the downregulated expression of FERRITIN and VACUOLAR IRON TRANSPORTER 2 (OsVIT2), whereas NATURAL RESISTANCE-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE 1 (OsNRAMP1) expression is upregulated to promote Fe efflux from the vacuoles. Chlorophyll content is increased by upregulating EARLY LESION LEAF 1 (ELL1) and NITRATE REDUCTASE 2 (OsNR2) expression and modulating carbohydrate metabolism to enhance leaf photosynthesis. In the roots, deoxymugineic acid (DMA) synthesis and efflux are promoted by upregulating the expression of NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 1 (OsNAS1), OsNAS2, and TRANSPORTER OF MUGINEIC ACID FAMILY PHYTOSIDEROPHORES 1 (OsTOM1), whereas PLASMA MEMBRANE H+-ATPASE 4 (OsA4) expression is upregulated to enhance H+ secretion, thereby improving Fe availability in the rhizosphere. Additionally, OsABF1, OsGA2oxs, and OsEUI1 are overexpressed to suppress gibberellin (GA) synthesis and promote GA inactivation, thereby reducing root GA content and mitigating its negative regulatory effects on Fe deficiency responses. Furthermore, Fe deficiency response in the roots is enhanced by modulating the cytokinin (CTK), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ETH) signaling pathways. Consequently, the tolerance of transgenic SY and SI rice seedlings to Fe deficiency stress is significantly improved

In addition, the net photosynthetic rate in the leaves was significantly higher in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT (Fig. 2F). High SUS and TPS activities during carbohydrate metabolism promote sucrose degradation. Compared to the Fe-sufficient group, OsSUS1 and OsTPS7 expression was significantly upregulated in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 leaves, whereas the changes were minimal in Fe-deficient WT (Fig. 6B). Thus, promoting phloem-mediated Fe transport may improve the net photosynthetic rate by influencing sucrose catabolism in the leaves under Fe-deficient conditions. Compared to the WT, the transgenic SY-3 and SI-4 exhibited higher dry weights under Fe-deficient conditions (Fig. 1). The leaf color and plant biomass indicated the improved adaptation of SY-3 and SI-4 seedlings to Fe deficiency, suggesting that promoting phloem-mediated iron transport enhances leaf photosynthesis by increasing chlorophyll content and regulating carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 12).

Overall, inducing phloem-mediated Fe transport reduced the Fe storage and promoted the remobilization of vacuolar Fe in the leaves under Fe-deficient conditions, thereby improving chlorophyll biosynthesis and mitigating the negative effects of Fe deficiency on leaf photosynthesis (Fig. 12).

Enhancing Phloem-Mediated Fe Transport Promotes Hormone Signal Transduction in Fe-Deficient Roots

In this study, the number of DEGs in the Fe-deficient roots far exceeded that in the leaves, with a significantly higher number in SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT (Fig. 4C). This suggests that Fe deficiency in the rhizosphere rapidly induces Fe deficiency responses in the roots much faster than in the leaves. The RNA-seq data revealed that the unique Fe deficiency-responsive pathways in SY-3 and SI-4 roots were involved in hormone signal transduction (Fig. 9B). In rice, GA, cytokinin (CTK), and jasmonic acid (JA) are known to negatively regulate Fe deficiency responses, whereas ethylene (ETH) positively regulates these responses.

The production of active GA is inhibited by Fe deficiency (Wild et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2020). Wang et al. (2017) found that both exogenous application of GA and endogenous increase in bioactive GA can reduce the iron concentration in the shoots by suppressing the expression of OsYSL2 involved in long-distance iron transport, then aggravating chlorosis and reducing growth. Under Fe-sufficient conditions, the GA4 contents in SY-3 and SI-4 roots were higher than that in the WT (Fig. 11A). Since GA negatively regulates Fe deficiency responses (Wang et al. 2017), rice plants may have reduced GA content by suppressing GA biosynthesis or promoting GA catabolism. In our study, the GA4 content in the roots was significantly decreased in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4, but was significantly increased in Fe-deficient WT (Fig. 11A), which is inconsistent with previous findings. Additionally, GA biosynthesis genes were significantly upregulated in the roots of both Fe-deficient WT and transgenic lines (Fig. S4). The upregulation ofOsEUI1, encoding a GA-inactivating enzyme, reduces the endogenous GA content in rice (Zhu et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2017). Here, Fe deficiency upregulated the OsEUI1 in the roots, with a higher expression in SY-3 and SI-4 than in the WT (Fig. 9A). Hence, we speculate that GA synthesis in the roots may be induced in the early stages of Fe deficiency to promote root development. As Fe deficiency persists, the activity of GA inactivation enzymes increases, gradually reducing the content of active GA in the roots. GA 2-oxidase (OsGA2) functions by converting GA precursors or bioactive GA into inactive forms through 2β-hydroxylation (Thomas et al. 1999; Hsieh et al. 2021). OsGA2ox7, OsGA2ox8, and OsGA2ox10 expression in the roots was significantly upregulated in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4, but remained unchanged in the WT (Fig. 9B). OsGA2oxs upregulation enhances root GA2 activity, promoting the degradation of active GA. As a key regulator of GA homeostasis, OsABF1 overexpression in rice results in a GA-deficient phenotype that can be restored by exogenous GA treatment (Amir Hossain et al. 2010; Tang et al. 2021), indicating that the increased OsABF1 expression suppressed GA synthesis. Under Fe-deficient conditions, OsABF1 expression was upregulated in SY-3 and SI-4 roots but showed no significant change in the WT (Fig. 9B). These results suggest that enhancing phloem-mediated Fe transport can rapidly induce GA catabolism to promote GA inactivation under Fe-deficient conditions, simultaneously suppressing GA synthesis through signal transduction, thereby reducing root GA content and mitigating its negative regulatory effects on Fe deficiency responses (Fig. 12).

In addition to GA, genes involved in the CTK, JA, and ETH signal transduction pathways exhibited differential expression in Fe-deficient WT, SY-3, and SI-4 roots (Fig. 9B). The expression of A-type response regulators OsRR6, OsRR9, and OsRR10 was significantly upregulated in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 roots but was unchanged in the WT (Fig. 9B). OsRR expression is induced by CTK levels and negatively regulates CTK signaling (Hirose et al. 2007; Tsai et al. 2012). In addition, transgenic rice with overexpressed OsRR6 has higher tZ content than the WT (Hirose et al. 2007). Here, OsRR6 expression was significantly higher in SY-3 and SI-4 roots than in the WT under both treatment conditions (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, the tZ contents in SY-3 and SI-4 roots remained significantly higher than that in the WT (Fig. 11B). High CTK content may have promoted root growth and enhanced Fe uptake (Figs. 1C and 3B). Fe deficiency elevates JA levels in rice during the early stages of Fe deficiency, subsequently inducing the expression of JA signaling repressors (OsJAZs) (Yamada et al. 2012; Kobayashi et al. 2016). Similarly, OsJAZ8 expression was significantly upregulated in SY-3 and SI-4 roots. The upregulation of OsRR6, OsRR9, OsRR10, and OsJAZ8 under Fe deficiency also suppressed CTK and JA signaling, reducing their negative regulatory effects on Fe deficiency response. The expression of ETH signaling-associated OsCTR2 and OsEBF1 was significantly downregulated in SY-3 and SI-4 roots (Fig. 9B). OsCTR2, homologous to Arabidopsis CTR1, negatively regulates ETH signaling, whereas the E3 ligase OsEBF1 mediates the degradation of the positive regulator ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE LIKE 1 (OsEIL1) through ubiquitination, thereby inhibiting ETH signaling (Wang et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2020). Iron deficiency induces ETH production and signaling in rice. Treatment with the ETH precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) not only strongly induced the expression of OsNAS1 and OsNAS2 in rice roots, but also upregulated the expression of OsYSL15 and OsIRT1, especially under Fe-deficient conditions. These findings suggest that ETH signaling enhances rice tolerance to iron deficiency by coordinately upregulating phytosiderophores biosynthesis and iron transport pathways (Wu et al. 2011). OsCTR2 and OsEBF1 downregulation may alleviate the suppression of ETH signaling, thereby upregulating the expression levels of OsNAS1 and OsNAS2 in SY-3 and SI-4 roots (Fig. S3), and enhancing ETH positive regulatory effects on Fe-deficiency responses. These results demonstrate that enhancing phloem-mediated Fe transport improves adaptability to Fe deficiency by suppressing CTK and JA signaling and enhancing ETH signaling in the roots, thereby enabling rapid Fe deficiency responses (Fig. 12).

Conclusions

In summary, enhancing phloem-mediated Fe transport can improve the adaptability of rice seedlings to Fe deficiency stress. Phloem-mediated Fe transport was improved in transgenic SY-3 and SI-4, with significantly higher Fe content and accumulation than in the WT. This is supported by the superior growth, SPAD values, and total chlorophyll contents in Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 compared to the WT. Additionally, SY-3 and SI-4 seedlings showed reduced negative regulation and enhanced positive regulation of Fe deficiency responses by modulating the GA levels and hormone signal transduction, elevating the threshold for Fe uptake and storage. Fe-deficient SY-3 and SI-4 had stronger Fe uptake, translocation, and remobilization capacities, promoting chlorophyll synthesis and maintaining normal growth and development. Furthermore, hormone signal transduction in SY-3 and SI-4 roots responded more rapidly to Fe deficiency, allowing immediate adaptation to a low-Fe environment. Our findings provide new insights for breeding rice varieties with high tolerance to Fe deficiency stress and offer novel directions for rice cultivation under Fe-deficient conditions, potentially improving yield.

Materials and methods

Plant Materials and Experimental Setups

Two plasmids were created using the phloem-specific sucrose transporter OsSUT1 (LOC_Os03g07480) promoter (2000 bp) to fuse the Fe transport genes, OsYSL9 (LOC_Os04g45860) cDNA (1974 bp), and OsIRT1 (LOC_Os03g46470) cDNA (1125 bp). The pOsSUT1::OsYSL9 and pOsSUT1::OsIRT1 plasmids were introduced into the rice cultivar Nipponbare via Agrobacterium (EHA105)-mediated transformation to generate the SY and SI transgenic rice plants, respectively. Transgenic lines SY-3 and SI-4 were used as the experimental groups, with WT Nipponbare as the control.

Seeds were surface-sterilized using 15% hydrogen peroxide. The sterilized seeds were washed thrice with distilled water, left in the dark for 72 h, and sown on moist quartz sand. After 2 weeks, the seedlings were transferred to a hydroponic system containing a one-half strength nutrient solution, consisting of KNO3 (1 mM), (NH4)2SO4 (0.5 mM), KH2PO4 (0.25 mM), MgCl2·6H2O (0.3 mM), CaCl2 (0.67 mM), MnCl2·4H2O (9 µM), H3BO3 (18.4 µM), Na2MoO4·2H2O (0.54 µM), ZnSO4·7H2O (0.14 µM), CuSO4·5H2O (0.16 µM), and Na2SiO3·9H2O (0.3 mM), and supplied with 40 µM Fe(II)-EDTA (pH 5.5). The rice seedlings were planted in a growth chamber with a 15-h light photoperiod, 28 and 24 ℃ (day/night) temperatures, and 70% relative humidity. At the 3-leaf stage (third leaf fully expanded), rice plants were divided into two batches and treated with 40 and 10 µM Fe(II)-EDTA to represent the Fe-sufficient and Fe-deficient groups, respectively.

Sampling

At 3 days after treatment (DAT), the phloem sap of the mature 3rd leaves was collected for Fe efflux rate analysis. At 7 DAT, the shoot and root tissues were harvested to measure the length, dry weight, and Fe content. The leaf chlorophyll content and photosynthetic rate were also measured at 7 DAT. Additionally, a separate batch of mature leaf and root tissues were collected from the same set of plants at 3 DAT and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA-seq and hormone analyses.

Measurement of Plant Growth

At 7 DAT, the shoot and root lengths were recorded using a ruler, and the seedlings were harvested and separated into the shoots and roots. The shoots and roots were dried at 80 ℃ until reaching a constant weight, and the dry biomass was measured.

Measurement of Leaf Chlorophyll Content and Photosynthetic Rate

At 7 DAT, the 3rd and 4th leaves were collected to determine the chlorophyll content. SPAD values were measured using SPAD-502 PLUS (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The total chlorophyll content was determined using spectrophotometry, following the method by Graziano et al. (2002). Fresh samples (0.1 g) were homogenized with 10 mL 80% acetone solution, followed by shaking at 20 ℃ in the dark for 12 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 663 and 645 nm using a spectrophotometer. The net photosynthetic rate of the 3rd leaves was measured using LI-6400 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) at 7 DAT.

Analysis of Fe Content

At 7 DAT, the rice seedlings were washed with deionized water and separated into the roots and shoots. The roots were soaked in 1 mM K2-EDTA for 10 min and washed thrice with deionized water. The root and shoot samples were deactivated at 105 ℃ for 30 min and dried at 80 ℃ to a constant weight. Dried samples (0.1 g) were digested with 2 mL nitric acid (Guaranteed reagent) using ETHOS One (Milestone, Sorisole, Italy). Distilled water was added to the digestion solution to a final volume of 50 mL. Fe concentration was analyzed via inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Optima 8000; PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, USA).

The calculation for Fe content is as follows:

|

The calculation for Fe accumulation is as follows:

|

Analysis of Fe Efflux Rate in the Leaf Phloem

The EDTA-facilitated exudation method was used to collect the phloem sap (Lin et al. 2023). At 3 DAT, the mature leaf was cut using a ceramic razor blade in a medium containing 10 mM EDTA-K2. The leaves were immediately transferred to a 10-mL tube with 2 mL EDTA-K2 solution (10 mM, pH = 8.0). For sap collection, the tubes were placed in a dark and humid chamber for 2 h. For Fe analysis, the phloem sap of each material from eight leaves per treatment was freeze-dried and re-dissolved in 12 mL 10% nitric acid. Fe concentration was analyzed using Optima 8000 (PerkinElmer).

Measurement of Root Hormone Content

At 3 DAT, the roots were washed thrice with deionized water and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Fresh samples (0.3 g) were homogenized in 1 mL extraction solution (1000:500:1 isopropanol: ultrapure water: hydrochloric acid) and shaken at 4 ℃ in the dark for 30 min. Subsequently, 2 mL mixed solution (1:1 extraction solution: dichloromethane) was added to the sample, followed by shaking at 4 ℃ in the dark for 30 min and centrifugation (4 ℃, 12000 rpm, 10 min). The lower organic phase was collected in another tube containing 0.2 g anhydrous magnesium sulfate and vortexed for 1 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, concentrated under dark conditions, and re-dissolved in 0.2 mL 0.1% formic acid-methanol solution. After filtering through a 0.22-µm membrane, the gibberellins and trans-zeatin (tZ) contents were analyzed via ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry using 1290 Infinity II (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and 6500 Qtrap (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA).

RNA‑seq Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the 3rd leaves and roots using RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) were used for RNA quantification and assessment.

Library construction and sequencing were performed using NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Clean reads were aligned to the rice reference genome (Oryza sativa Japonica, GCF_001433935.1_IRGSP-1.0) using HISAT2 (Kim et al. 2015). RNA-seq analysis was conducted using OmicShare (https://www.omicshare.com; Gene Denovo, Guangzhou, China). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to evaluate sample variability and reproducibility. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with fold changes ≥ 2 and FDR values ≤ 0.05, were identified using DESeq2 (Love et al. 2014). The Z-score algorithm was applied to calculate the relative values for heat map visualization. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) databases were used for annotation. Significantly enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways were obtained using OmicShare tools.

Real‑time qPCR

Residual RNA samples from the RNA-seq analysis were used to validate the expression of DEGs via real‑time qPCR (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific). DEG expression was calculated using the relative quantification method (2−ΔΔCt), with OsActin as internal control (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Each qPCR experiment included three biological replicates per sample. The primers used are listed in Table S1.

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used for data organization and recording. SPSS 25.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) were used for statistical analysis and data visualization, respectively.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of our laboratory for their help in sample collection. We thank Jin Wang, Jun Chen and Chunhua Zhang from the Biological Experiment Teaching Center (College of Life Sciences, Nanjing Agriculture University) for their help in using microwave digestion system and ICP-OES.

Abbreviations

- ACC

1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid

- CTK

Cytokinin

- DAT

Days after treatment

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DMA

Deoxymugineic acid

- DMAS

Deoxymugineic acid synthase

- ETH

Ethylene

- Fe

Iron

- FER

Ferritin

- frd3

FERRIC REDICTASE DEFECTIVE 3

- GA

Gibberellin

- GO

Gene Ontology

- JA

Jasmonic acid

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- NAS

Nicotianamine synthase

- NAAT

Nicotianamine amino-transferase

- NRAMP

Natural resistance-associated macrophage

- NT

Non-transgenic

- OsA4

PLASMA MEMBRANE H+ -ATPASE 4

- OsABF1

ABSCISIC ACID-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT-BINDING FACTOR 1

- OsCTR2

CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE 2

- OsEBF1

EIN3-BINDING F-BOX PROTEIN 1

- OsELL1

EARLY LESION LEAF 1

- OsENA1

EFFLUX TRANSPORTER OF NA

- OsEUI1

ELONGATED UPPERMOST INTERNODE1

- OsGA2ox

GIBBERELLIN 2-OXIDASE

- OsGA3ox

GIBBERELLIN 3Β-HYDROXYLASE

- OsGA20ox

GIBBERELLIN 20-OXIDASE

- OsIRT

IRON-REGULATED TRANSPORTER

- OsJAZ8

JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN 8

- OsNAAT1

NICOTIANAMINE AMINOTRANSFERASE 1

- OsNAS

NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE

- OsNR2

NITRATE REDUCTASE 2

- OsNRAMP1

NATURAL RESISTANCE-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE 1

- OsRR

A-TYPE RESPONSE REGULATOR

- OsSUT1

SUCROSE TRANSPORTER 1

- OsTOM1

TRANSPORTER OF MUGINEIC ACID FAMILY PHYTOSIDEROPHORES 1

- OsVIT2

VACUOLE IRON TRANSPORTER 2

- OsYSL

YELLOW STRIPE-LIKE

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- qPCR

Quantitative PCR

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SI

POsSUT1::OsIRT1

- SPAD

Soil–plant analysis development

- SY

POsSUT1::OsYSL9

- VIT

Vacuole iron transporter

- WT

Wild-type

Author contributions

L.C., G.L., Z.L., and Y.D. designed the experiments. Y.L. and B.L. performed the experiments. Y.L. and Y.H. analyzed the RNA-seq data. Y.L. and L.C. wrote the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No 32272206), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD2301304, 2022YFD2301404) and the Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production co-sponsored by Province and Ministry (CIC-MCP).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aksoy E, Maqbool A, Tindas İ, Caliskan S (2017) Soybean: A new frontier in Understanding the iron deficiency tolerance mechanisms in plants. Plant Soil 418(1–2):37–44. 10.1007/s11104-016-3157-x [Google Scholar]

- Amir Hossain Md, Lee Y, Cho JI et al (2010) The bZIP transcription factor OsABF1 is an ABA responsive element binding factor that enhances abiotic stress signaling in rice. Plant Mol Biol 72(4–5):557–566. 10.1007/s11103-009-9592-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir K, Inoue H, Nagasaka S et al (2006) Cloning and characterization of Deoxymugineic acid synthase genes from graminaceous plants. J Biol Chem 281:32395–32402. 10.1074/jbc.M604133200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir K, Hanada K, Shimizu M et al (2014) Transcriptomic analysis of rice in response to iron deficiency and excess. Rice 7:18. 10.1186/s12284-014-0018-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briat JF, Duc C, Ravet K, Gaymard F (2010) Ferritins and iron storage in plants. Biochimica et biophysica acta (BBA). - Gen Subj 1800:806–814. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che J, Yamaji N, Ma JF (2021) Role of a vacuolar iron transporter OsVIT2 in the distribution of iron to rice grains. New Phytol 230:1049–1062. 10.1111/nph.17219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wang GP, Chen PF et al (2018a) Shoot-Root communication plays a key role in physiological alterations of rice (Oryza sativa) under iron deficiency. Front Plant Sci 9:757. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PF, Chen L, Jiang ZR et al (2018b) Sucrose is involved in the regulation of iron deficiency responses in rice (Oryza sativa L). Plant Cell Rep 37(5):789–798. 10.1007/s00299-018-2267-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhang NN, Pan Q et al (2020) Hydrogen sulphide alleviates iron deficiency by promoting iron availability and plant hormone levels in Glycine max seedlings. BMC Plant Biol 20:383. 10.1186/s12870-020-02601-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Peng Y, Zhang Q et al (2021) Disruption of EARLY LESION LEAF 1, encoding a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, induces ROS accumulation and cell death in rice. Plant J 105(4):942–956. 10.1111/tpj.15079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C, Mari S (2017) New routes for plant iron mining. New Phytol 214(2):521–525. 10.1111/nph.14364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Wang Y, Chen G et al (2019) The indica nitrate reductase gene OsNR2 allele enhances rice yield potential and nitrogen use efficiency. Nat Commun 10:5207. 10.1038/s41467-019-13110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García MJ, Suárez V, Romera FJ et al (2011) A new model involving ethylene, nitric oxide and Fe to explain the regulation of Fe-acquisition genes in strategy I plants. Plant Physiol Biochem 49:537–544. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García MJ, Romera FJ, Stacey MG et al (2013) Shoot to root communication is necessary to control the expression of iron-acquisition genes in strategy I plants. Planta 237:65–75. 10.1007/s00425-012-1757-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano M, Lamattina L (2007) Nitric oxide accumulation is required for molecular and physiological responses to iron deficiency in tomato roots. Plant J 52(5):949–960. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano M, Beligni MV, Lamattina L (2002) Nitric oxide improves internal iron availability in plants. Plant Physiol 130(4):1852–1859. 10.1104/pp.009076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerinot ML (2001) Improving rice yields—ironing out the details. Nat Biotechnol 19(5):417–418. 10.1038/88067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose NX, Makita N, Kojima M et al (2007) Overexpression of a type-A response regulator alters rice morphology and cytokinin metabolism. Plant Cell Physiol 48(3):523–539. 10.1093/pcp/pcm022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi K, Saito A, Mikami Y, Miwa E (2011) Modulation of macronutrient metabolism in barley leaves under iron-deficient condition. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 57(2):233–247. 10.1080/00380768.2011.564574 [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M, Higuchi K, Sasaki H et al (2007) Contribution of iron associated with high-molecular-weight substances to the maintenance of the SPAD value of young leaves of barley under iron-deficient conditions. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 53(5):612–620. 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2007.00190 [Google Scholar]

- Hoan NT, Prasada Rao U, Siddiq EA (1992) Genetics of tolerance to iron chlorosis in rice. Plant Soil 146(1–2):233–239. 10.1007/BF00012017 [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh KT, Chen YT, Hu TJ et al (2021) Comparisons within the rice GA 2-oxidase gene family revealed three dominant paralogs and a functional attenuated gene that led to the identification of four amino acid variants associated with GA deactivation capability. Rice 14:70. 10.1186/s12284-021-00499-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Higuchi K, Takahashi M et al (2003) Three rice Nicotianamine synthase genes, OsNAS1, OsNAS2, and OsNAS3 are expressed in cells involved in long-distance transport of iron and differentially regulated by iron. Plant J 45:S184–S184. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01878.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Takahashi M, Kobayashi T et al (2008) Identification and localisation of the rice Nicotianamine aminotransferase gene OsNAAT1 expression suggests the site of phytosiderophore synthesis in rice. Plant Mol Biol 66(1–2):193–203. 10.1007/s11103-007-9262-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Kobayashi T, Nozoye T et al (2009) Rice OsYSL15 is an iron-regulated iron(III)-deoxymugineic acid transporter expressed in the roots and is essential for iron uptake in early growth of the seedlings. J Biol Chem 284:3470–3479. 10.1074/jbc.M806042200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y, Suzuki M, Tsukamoto T et al (2006) Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+-phytosiderophore and as Fe2+. Plant J 45:335–346. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Guerinot ML (2009) Homing in on iron homeostasis in plants. Trends Plant Sci 14(5):280–285. 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SA, Punshon T, Lanzirotti A et al (2006) Localization of iron in Arabidopsis seed requires the vacuolar membrane transporter VIT1. Science 314(5803):1295–1298. 10.1126/science.1132563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2015) HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12(4):357–U121. 10.1038/nmeth.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Nishizawa NK (2012) Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 63:131–152. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Itai RN, Senoura T et al (2016) Jasmonate signaling is activated in the very early stages of iron deficiency responses in rice roots. Plant Mol Biol 91(4–5):533–547. 10.1007/s11103-016-0486-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike S, Inoue H, Mizuno D et al (2004) OsYSL2 is a rice metal-nicotianamine transporter that is regulated by iron and expressed in the phloem. Plant J 39(3):415–424. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V, Lelièvre F, Bolte S et al (2005) Mobilization of vacuolar iron by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is essential for seed germination on low iron. EMBO J 24(23):4041–4051. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Chiecko JC, Kim SA et al (2009) Disruption of OsYSL15 leads to iron inefficiency in rice plants. Plant Physiol 150(2):786–800. 10.1104/pp.109.135418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Hu YX, Wu Y et al (2023) Inhibition of sucrose source-to-sink transport reduces iron accumulation in rice. J Plant Growth Regul 43(5):1496–1570. 10.1007/s00344-023-11200-y [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–∆∆CT method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucena C, Waters BM, Romera FJ et al (2006) Ethylene could influence ferric reductase, iron transporter, and H+-ATPase gene expression by affecting FER (or FER-like) gene activity. J Exp Bot 57:4145–4154. 10.1093/jxb/erl189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Yang X, Shi Z, Miao X (2020) Novel crosstalk between ethylene- and jasmonic acid-pathway responses to a piercing–sucking insect in rice. New Phytol 225(1):474–487. 10.1111/nph.16111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas FM, van de Wetering DAM, van Beusichem ML, Bienfait HF (1988) Characterization of phloem Iron and its possible role in the regulation of Fe-Efficiency reactions. Plant Physiol 87:167–171. 10.1104/pp.87.1.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Higuchi K, Yoshida M, Tadano T (2005) Comparison of iron availability in leaves of barley and rice. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 51(7):1035–1042. 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2005.tb00142.x [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Nishizawa N, Hayashi H et al (1991) Why are young rice plants highly susceptible to iron deficiency? In: Chen, Y., Hadar, Y. (eds) Iron Nutrition and Interactions in Plants. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Iron Nutrition and Interactions in Plants, Jerusalem, June 1989. Developments in Plant and Soil Sciences, vol 43. Springer, Dordrecht, p 175–188. 10.1007/978-94-011-3294-7_23 43:175–188

- Nishiyama R, Kato M, Nagata S et al (2012) Identification of Zn–Nicotianamine and Fe–2′-Deoxymugineic acid in the phloem Sap from rice plants (Oryza sativa L). Plant Cell Physiol 53(2):381–390. 10.1093/pcp/pcr188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozoye T, Nagasaka S, Kobayashi T et al (2011) Phytosiderophore efflux transporters are crucial for Iron acquisition in graminaceous plants. J Biol Chem 286(7):5446–5454. 10.1074/jbc.M110.180026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MP, Santos C, Gomes A, Vasconcelos MW (2014) Cultivar variability of iron uptake mechanisms in rice (Oryza sativa L). Plant Physiol Biochem 85:21–30. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riaz N, Guerinot ML (2021) All together now: regulation of the iron deficiency response. J Exp Bot 72(6):2045–2055. 10.1093/jxb/erab003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockel P, Strube F, Rockel A et al (2002) Regulation of nitric oxide (NO) production by plant nitrate reductase in vivo and in vitro. J Exp Bot 53(366):103–110. 10.1093/jexbot/53.366.103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roriz M, Carvalho SMP, Vasconcelos MW (2014) High relative air humidity influences mineral accumulation and growth in iron deficient soybean plants. Front Plant Sci 5:726. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Shinjo S, Ito D et al (2021) Enhancement of photosynthetic iron-use efficiency is an important trait of hordeum vulgare for adaptation of photosystems to iron deficiency. Plants. 10(2):234. 10.3390/plants10020234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakariyawo OS, Oyedeji OE, Soretire AA (2020) Effect of iron deficiency on the growth, development and grain yield of some selected upland rice genotypes in the rainforest. J Plant Nutr 43(6):851–863. 10.1080/01904167.2020.1711936 [Google Scholar]

- Santi S, Schmidt W (2009) Dissecting iron deficiency-induced proton extrusion in Arabidopsis roots. New Phytol 183(4):1072–1084. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi S, Cesco S, Varanini Z, Pinton R (2005) Two plasma membrane H+-ATPase genes are differentially expressed in iron-deficient cucumber plants. Plant Physiol Biochem 43(3):287–292. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoura T, Sakashita E, Kobayashi T et al (2017) The iron-chelate transporter OsYSL9 plays a role in iron distribution in developing rice grains. Plant Mol Biol 95(4–5):375–387. 10.1007/s11103-017-0656-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RJ, Ricachenevsky FK, Fett JP (2009) Differential regulation of the two rice ferritin genes (OsFER1 and OsFER2). Plant Sci 177(6):563–569. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.08.001 [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S (1976) Naturally occurring iron-chelating compounds in oat- and rice-root washings: I. Activity measurement and preliminary characterization. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 22:423–433. 10.1080/00380768.1976.10433004 [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Xu H, Wang Y et al (2021) OsABF1 represses Gibberellin biosynthesis to regulate plant height and seed germination in rice (Oryza sativa L). Int J Mol Sci 22:12220. 10.3390/ijms222212220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P (1999) Molecular cloning and functional expression of Gibberellin 2-oxidases, multifunctional enzymes involved in Gibberellin deactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96(8):4698–4703. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YC, Weir NR, Hill K et al (2012) Characterization of genes involved in cytokinin signaling and metabolism from rice. Plant Physiol 158(4):1666–1684. 10.1104/pp.111.192765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto T, Nakanishi H, Uchida H et al (2009) 52Fe translocation in barley as monitored by a Positron-Emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS): evidence for the direct translocation of Fe from roots to young leaves via phloem. Plant Cell Physiol 50(1):48–57. 10.1093/pcp/pcn192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhang W, Yin Z, Wen CK (2013) Rice CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE-RESPONSE2 is involved in the ethylene-receptor signalling and regulation of various aspects of rice growth and development. J Exp Bot 64(16):4863–4875. 10.1093/jxb/ert272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wei H, Xue Z, Zhang WH (2017) Gibberellins regulate iron deficiency-response by influencing iron transport and translocation in rice seedlings (Oryza sativa). Ann Bot 119(6):945–956. 10.1093/aob/mcw250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Chu HH, DiDonato RJ et al (2006) Mutations in Arabidopsis Yellow Stripe-Like1 and Yellow Stripe-Like3 reveal their roles in metal Iorn homeostasis and loading of metal irons in seeds. Plant Physiol 141(4):1446–1458. 10.1104/pp.106.082586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild M, Davière JM, Regnault T et al (2016) Tissue-Specific regulation of Gibberellin signaling Fine-Tunes Arabidopsis Iron-Deficiency responses. Dev Cell 37:190–200. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JJ, Wang C, Zheng LQ et al (2011) Ethylene is involved in the regulation of iron homeostasis by regulating the expression of iron-acquisition-related genes in Oryza sativa. J Exp Bot 62:667–674. 10.1093/jxb/erq301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie R, Zhao J, Lu L et al (2019) Efficient phloem remobilization of Zn protects Apple trees during the early stages of Zn deficiency. Plant Cell Environ 42(12):3167–3181. 10.1111/pce.13621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Kano A, Tamaoki D et al (2012) Involvement of OsJAZ8 in Jasmonate-Induced resistance to bacterial blight in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 53(12):2060–2072. 10.1093/pcp/pcs145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xu Y, Yi H, Gong J (2012) Vacuolar membrane transporters OsVIT1 and OsVIT2 modulate iron translocation between flag leaves and seeds in rice. Plant J 72(3):400–410. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Nomura T, Xu Y et al (2006) ELONGATED UPPERMOST INTERNODE encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase that epoxidizes gibberellins in a novel deactivation reaction in rice. Plant Cell 18(2):442–456. 10.1105/tpc.105.038455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.