Abstract

The use of in vitro (fish cell lines) is a cost-effective, very rapid, and informative tool for toxicological assessments. Using the neutral red (NR) assay, we compared the in vitro acute toxicity (20hEC50) of twenty-six chemical substances on a rainbow trout gonad cell line (RTG-2) with their in vivo acute toxicity to Barbados Millions Poecilia reticulata (48hLC50, OECD 203) and crustacean Daphnia magna (48hEC50, OECD 202). The 20hEC50 values obtained by the NR assay were higher in nearly all the cases when compared to the 48hLC50 in P. reticulata and the 48hEC50 in D. magna, indicating that the sensitivity of the RTG-2 cell line was lower compared to P. reticulata and D. magna. A high (r = 0.89) and significant (P < 0.001) correlation was recorded between the 20hEC50 values of the RTG-2 and the 48hEC50 values of D. magna. The correlation between the 20hEC50 values of the RTG-2 and the 48hLC50 values of P. reticulata was lower (r = 0.65; P < 0.001), but also significant. The authors recommend use of the NR assay on the RTG-2 cell lines as a screening protocol to evaluate the toxicity of xenobiotics in aquatic environments to narrow the spectrum of the concentrations for the fish toxicity test.

Keywords: cytotoxicity, NR assay, Daphnia magna, fish cell line RTG-2, Poecilia reticulata

For ethical, scientific, and mainly economic reasons (Hutchinson et al. 2003; Segner 2004), in vitro models using fish cell lines have been developed for the screening toxicity of xenobiotics (Rachlin and Perlmutter 1968; Kocan et al. 1979; Ahne 1985; Bols et al. 1985). The first use of in vitro cytotoxicity assays with cultured fish cells was in 1968 (Rachlin and Perlmutte 1968). Cell cultures for the ecotoxicological assessment offer advantages over in vivo animal tests, and in vitro fish cell models are rapid, cheap, and reproducible. The white paper on a strategy for a chemical policy in the European Union (EU 2001) emphasised the reduction of animal testing and the development and application of in vitro analyses. Currently, the use of fish cell lines for the evaluation toxic effects of xenobiotics in an aquatic ecosystem is a technique for predicting the in vivo acute cytotoxicity (Kahraman and Sacan 2018). The neutral red (NR) assay is a widely used test for quantifying the cytotoxicity of xenobiotics in monolayer cell cultures. The NR assay is based on the accumulation of the neutral red dye in the lysosomes of the viable cells (Borenfreund and Puerner 1985). Exposure to substances causing membrane damage inhibits the accumulation of dye.

Many xenobiotics enter the aquatic ecosystem that, because of toxicity, their persistence, and bioaccumulation, can produce negative effects on aquatic organisms (Babin et al. 2008) and present a public health threat. The establishment of sensitive monitoring systems for the detection and toxicological evaluation is required (Caminada et al. 2006; Tan et al. 2008). Fish cell lines can be used for the determination of the cytotoxicity of xenobiotics in samples, and their application is likely to become a standard practice (Morcillo et al. 2016).

Analysis of the in vitro effects of xenobiotics can predict their toxic effects on in vivo aquatic organisms, and cytotoxic assay using cultured fish cells has become a useful tool in the initial screening of xenobiotics and their toxic effects (Martin-Alguacil et al. 1991; Araujo et al. 2000). The first step in the wide use of in vitro testing as models for animal experiments is the correlation of the in vitro and in vivo activity (Caminada et al. 2006). Our study provides the in vitro toxicity data of twenty-six xenobiotics that may serve as identification of the toxicity and as an elementary assessment. The data obtained from the in vitro toxicity tests was compared with the results of acute tests on in vivo Barbados Millions Poecilia reticulata and Daphnia magna.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cell culture RTG-2

The fibroblastic RTG-2 cell line, from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) gonads (cell line obtained from the cryobank of the Veterinary Research Institute, Brno, Czech Republic) was used for the NR assay. The cell line was grown in a minimal essential medium (MEM) with Earle’s salts, supplemented with a 10% foetal bovine serum; 20 mM HEPES/pH 7.2, antibiotics (neomycin); and l-glutamine, at 18 ± 2 °C. The cells were regularly divided every five days by dissociating with 0.05% (w/v) trypsin and 0.5 mM EDTA and sub-cultured at split ratios of ~1 : 3. The ingredients were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Prague, Czech Republic).

The cells were harvested at the exponential proliferation phase, seeded in 96-well microtitre plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at 3 000 cells/well in 100 μl of the cell medium, and incubated for 4 h at 20 °C. The test exposure started with replacement of the growth medium with the fresh same growth medium spiked with a tested concentration of the substance (there were seven different concentrations of the tested substance in one 96-well microtitre plate, with six repetitions of each concentration (Table 1) and incubated for 20 h at 20 °C.

Table 1. Allocation of the test cultures to the individual microtitre plate wells.

| Well | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| A | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B |

| B | B | C– | C+ | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | C– | B |

| C | B | C– | C+ | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | C– | B |

| D | B | C– | C+ | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | C– | B |

| E | B | C– | C+ | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | C– | B |

| F | B | C– | C+ | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | C– | B |

| G | B | C– | C+ | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | C– | B |

| H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B |

B = blank, 10% MEM without cells; C– = negative control, 10% MEM with cells; C+ = positive control, 2% DMSO (3,3 dichlorophenol) in 10% MEM with cells; P1–P7 = seven concentrations of the tested substances

Neutral red testing

The NR assay method (Clothier 1990; Hadler and Ahne 1990) is based on the capacity of the undamaged cellular lysosomes to take up the NR dye. The in vitro toxicity test was conducted in microtitration plates. The cell culture was exposed to the tested substance at 3 × 105 cells per 1 ml of the medium for 20 hours.

The test culture allocation of the individual wells of the microtitre plate is shown in Table 1. For the NR test, we used a blank, negative control, positive control, and seven concentrations of the tested substance, each in six repetitions, with the exception of twelve repetitions for the negative control. The colour intensity was assessed photometrically (SLT Spectra Shell 39053; SLT Lab Instruments, Salzburg, Austria). The 20hEC50, the concentration that decreased absorbance to 50% of that observed in the negative control at 20 h was determined from the mean values of the seven test wells. The positive control was included due to the validity of the test.

Toxicity tests

The in vivo acute toxicity tests were carried out according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guideline 202 Daphnia sp., Acute Immobilisation Test (48hEC50) (OECD 2004) and the OECD guideline 203 Fish, Acute Toxicity Test for Poecilia reticulata (48hLC50) (OECD 1992).

Tested substances

Chemicals intended for commercial use and toxicological standards were selected for testing. The tested substances are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Codes for the tested substances.

| Category of substances | Code |

| Surfactants | SAS 1–9 |

| Carbamate based pesticides | PK 1–6 |

| Glyphosate based pesticide | PG |

| Urea based pesticide | PU |

| Flame retardant | FFS |

| Organic amine | OA |

| Detergent + NaOH | D 1–2 |

| Aminopentanol | A |

| Bacillus subtilis spores | SBS |

| p-nitrophenol | p-NP |

| Zinc sulfate | Zn |

| Potassium bichromate | Cr |

Statistical analysis

The data of the concentration-dependent cytotoxicity relationships are presented in relation to the positive and negative controls. The concentrations that reduced the NR staining relative to the controls by 50% at 20 h were characterised as mid-range cytotoxicity values (20hEC50). Analysis of the data was performed in the Statgraphics Plus v5.1 program. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Correlation between the in vivo values (24hLC50 in P. reticulata and 48hEC50 in D. magna) and the in vitro cytotoxicity values (20hEC50) were determined by linear regression (EKO-TOX v5.1 software). The raw data were logarithmically transformed to express the regressive dependence.

Ethics

All the procedures complied with relevant legislative regulations of the Czech Republic (No. 166/1996 and No. 246/1992). The testing of acute toxicity to fish was approved by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, permission No. 513100/2013-MZE-17214. The study did not involve endangered or protected species.

RESULTS

The results of the in vitro tests carried out by the NR assay with the RTG-2 cell line are provided along with the results of the in vivo acute toxicity tests of P. reticulata and D. magna.

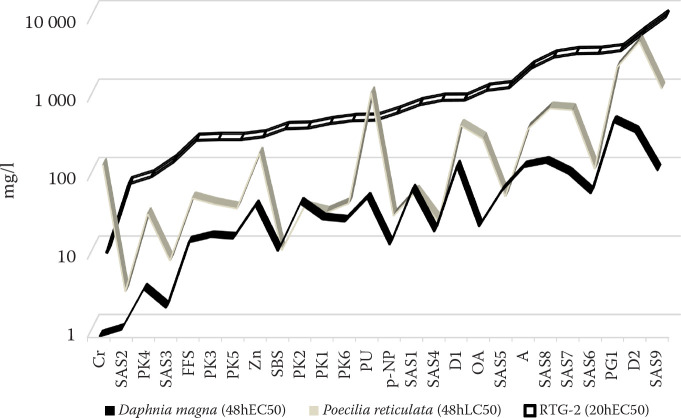

The 20hEC50 concentration in the fish cells was higher for nearly all the tested substances compared to the 48hLC50 concentration to P. reticulata and the 48hEC50 concentration to D. magna, indicating the lower sensitivity of the RTG-2 cell line to toxic agents compared to that observed in P. reticulata and D. magna (Figure 1). In Figure 1, the test substances are arranged on the x-axis according to the results of the cell toxicity tests (RTG-2 20hEC50) in order to clearly present a comparison of all three types of acute toxicity tests performed (fish cells – daphnia – fish). A continuous line of toxicity results was used to express the trend of similarity between the tests. While the sensitivity of the organisms differed, the responses to the specific chemicals showed a similar trend.

Figure 1. Results of the cytotoxicity test on the RTG-2 cells, the acute immobilisation test on Daphnia magna, and the acute toxicity test on Poecilia reticulata (mg/l).

The correlation between the in vitro and in vivo tests is shown in Figure 2. A significant correlation between the effects of almost all the tested substances on crustacean D. magna and RTG-2 cells was found (r = 0.89, P < 0.001). The correlation between the 20hEC50 values of RTG-2 and the 48hLC50 values of P. reticulata was lower (r = 0.65, P < 0.001), but significant.

Figure 2. Correlation of the in vivo 48hLC50 values ob-tained for Poecilia reticulata, the 48hEC50 values obtained for Daphnia magna, and the in vitro 20hEC50 value of the NR assay on the RTG-2 cells.

DISCUSSION

The effect of xenobiotics on organisms initially takes place at the cellular level. The use of in vitro cell cultures can be the first sensitive tool for the toxicological assessment of xenobiotics (Ni Shuilleabhain et al. 2004). The research of Segner (2004) confirms the good correlation of the fish cell lines or fish primary cell cultures with lethality data from fish acute toxicity tests. Halder and Ahne (1990), Kohlpoth and Rusche (1992), and Rusche and Kohlpoth (1993) compared the sensitivity of the in vitro toxicity of waste waters on a fibroblastic cell line from the Oncorhynchus mykiss liver (R1) and the in vivo exposure to Leuciscus idus melanotus. Agreement of the positive and/or negative results was reported in 89% of the cases by Halder and Ahne (1990) and in 86.6% of the cases by Rusche and Kohlpoth (1993). Kohlpoth and Rusche (1992) conducted 268 tests of waste water in 1988, 1989, and 1990 and reported agreement of the R1 cytotoxic assay and fish toxicity tests as 50, 70, and 75%, respectively.

Comparison of the sensitivity of the in vitro and in vivo testing of chemical substances was reported by Bols et al. (1985) and Bruschweiler et al. (1995). The former tested twelve chemical substances on RTG-2 cells and on rainbow trout fry. The ranking of the cytotoxicity values was in accordance with that of the toxicity values in fish. We found a lower sensitivity of the RTG-2 cell line compared with P. reticulata (Figure 1). However, the results of our toxicity tests on the RTG-2 showed a significant correlation with those of P. reticulata. A similar correlation was found by Bruschweiler et al. (1995) between the cytotoxicity and toxicity to fish (NR assay r = 0.86, P < 0.001, MTT test r = 0.80, P < 0.001).

According to Bruschweiler et al. (1995), the sensitivity of Oryzias latipes to twenty-one organic compounds of tin was higher, or similar to, than that of in vitro PCHC-1 liver cells (NR). In our tests on the RTG-2 cells, all the values of 20hEC50, except for K2Cr2O7 and a urea-based pesticide, were higher than the 48hEC50 values for P. reticulata. The comparison of our results with those of Bruschweiler et al. (1995) suggests the lower sensitivity of the RTG-2 cell line to toxic agents than that of the PCHC-1 cell line. While Bruschweiler et al. (1995) exclusively tested organic compounds, we tested inorganic substances. The sensitivity of the fish species used may also differ.

The aquatic crustacean D. magna is highly sensitive to toxic substances (Svobodova and Faina 1993) and is a common model species used in aquatic toxicology (OECD, ISO, ON 46 6807). The 48hEC50 values for D. magna of all twenty-six tested substances and preparations were lower than the 20hEC50 values for the RTG-2 cells (Table 2 and Figure 1). The correlation of these values was found to be high (r = 0.89) and significant (P < 0.001).

The levels of the toxicity depend on the exposed species, cell line, characteristics of the target substance, and on the dilution water or medium in which the test is carried out (Pitter 1980). An in vivo dilution medium contains a relatively high quantity of proteins. These can create insoluble complexes, particularly with metals, and significantly decrease the toxicity. Marion and Dinizeau (1983) reported that cadmium cytotoxicity in RTG-2 cells was observed only when the nutrient serum concentration in the diluting medium was decreased to 1%. We tested two inorganic compounds, potassium bichromate (K2Cr2O7) and zinc sulfate (ZnSO4 7H2O). The ratio of the potassium bichromate and zinc sulfate 20hEC50 value of the RTG-2 cells to the 48hEC50 value for D. magna was comparable to that observed for the other tested substances (Figure 1).

The 48hLC50 value of potassium bichromate in P. reticulata was higher than the 20hEC50 value in the RTG-2 cells, and the 48hLC50 value of zinc sulfate in P. reticulata was similar to the 20hEC50 value in the RTG-2 cells. It is necessary to take the composition of diluting medium and its potential effect on results of in vitro toxicity tests into account.

The results of this study allow for recommendation of the NR assay on an RTG-2 cell line as an appropriate screening method for the evaluation of the toxicity of xenobiotics in the aquatic environment, preferably with a preliminary test on D. magna. The verified correlation of the two tests will enable the use of a narrow range of concentrations of a substance for fish toxicity tests.

The 48hEC50 value in D. magna and the 48hLC50 value in P. reticulata were also similar (r = 0.89) and significant (P < 0.001) in all the tested substances.

As anthropogenic environmental contamination is increasing, the development and application of in vitro models to monitor the toxicity of new and existing chemicals is essential. We showed that NR assays using an RTG-2 cell line can be used as a screening method to detect and evaluate pollutants in the aquatic environment. Further research must be undertaken with a broader set of xenobiotics, and correlation with in vivo data must be performed.

Acknowledgement

Authors thank Ing. Vladimír Piačka for technical assistance.

Funding Statement

Supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, Project CENAKVA (LM2018099) and Project NAZV (QK1710310).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ahne W. Untersuchungen uber die Verwendung von Fischzellkulturen fur Toxizitatsbestimmungen zur Einschrankung und Ersatz des Fischtests [Use of fish cell cultures for toxicity determination in order to reduce and replace the fish tests]. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg B. 1985 May;180(5-6):480-504. German. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo CS, Marques SA, Carrondo MJ, Goncalves LM. In vitro response of the brown bullhead catfish (BB) and rainbow trout (RTG-2) cell lines to benzo[a]pyrene. Sci Total Environ. 2000 Mar 20;247(2-3):127-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babin MM, Canas I, Tarazona JV. An in vitro approach for ecotoxicity testing of toxic and hazardous wastes. Span J Agric Res. 2008 Oct;6(S1):124-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bols NC, Bolinska SA, Dixon DG, Hodson DV, Kaiser KLE. The use of fish cell-cultures as an indication of contaminant toxicity to fish. Aquat Toxicol. 1985 Mar;6(2):147-55. [Google Scholar]

- Borenfreund E, Puerner JA. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alternations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol Lett. 1985 Mar;24(2-3):119-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruschweiler BJ, Wurgler FE, Fent K. Cytotoxicity in vitro of organotin compounds to fish cells PHLC-1 (Poeciliopsis lucida). Aquat Toxicol. 1995 Jun;32(2-3):143-60. [Google Scholar]

- Caminada D, Escher C, Fent K. Cytotoxicity of pharmaceuticals found in aquatic systems: Comparison of PLHC-1 and RTG-2 fish cell lines. Aquat Toxicol. 2006 Aug 23;79(2):114-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clothier R. The frame modified neutral red uptake cytotoxicity test. Queen´s Medicinal Centre Nottingham, Invittox Protocol No. 3a. Nottingham, England: INVITTOX; 1990. 10 p. [Google Scholar]

- EU – European Union. White paper: Strategy for a future chemicals policy. COM 88 final. Brussels: Commision of the European Communities; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Halder M, Ahne W. Evaluation of waste water toxicity with three cytotoxicity tests. Z Wasser Abwass For. 1990 Aug;23(6):233-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson TH, Barrett S, Buzby M, Constable D, Hartmann A, Hayes E, Huggett D, Laenge R, Lillicrap AD, Straub JO, Thompson RS. A strategy to reduce the numbers of fish used in acute ecotoxicity testing of pharmaceuticals. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2003 Dec;22(12):3031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahraman EN, Sacan MT. On the prediction of cytotoxicity of diverse chemicals for topminnow (Poeciliopsis lucida) hepatoma cell line, PLHC-1. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2018 Sep;29(9):675-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocan RM, Landolt ML, Sabo KM. In vitro toxicity of 8 mutagens-carcinogens for 3 fish cell-lines. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1979 Sep;23(1-2):269-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlpoth M, Rusche B. Die Verwendung von Fischzellkulturen als Ersatz fur den Fischtest im Abwassergesetz [The use of fish cell cultures as a replacement for the fish test in the Waste Water Act]. In: Schoffel H, Schulte-Hermann R, Tritthart HA, editors. Moglichkeiten und Grenzen der Reduktion von Tierversuchen, Ersatz- und Erganzungsmethoden zu Tierversuchen [Possibilities and limits to the reduction of animal experiments, substitute and complementary methods to animal experiments]. Wien, New York: Springer; 1992. p. 118-21. German. [Google Scholar]

- Marion M, Denizeau F. Rainbow trout and human cells in culture for the evaluation of the toxicity of aquatic pollutants: A study with cadmium. Aquat Toxicol. 1983 May;3(4):329-43. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Alguacil N, Babich H, Rosenberg DW, Borenfreund E. In vitro response of the brown bullhead catfish cell line, BB, to aquatic pollutants. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1991 Jan;20(1):113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo P, Esteban MA, Cuesta A. Heavy metals produce toxicity, oxidative stress and apoptosis in the marine teleost fish SAF-1 cell line. Chemosphere. 2016 Feb;144(1):225-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Shuilleabhain S, Mothersill C, Sheehan D, O’Brien NM, O’ Halloran J, Van Pelt FN, Davoren M. In vitro cytotoxicity testing of three zinc metal salts using established fish cell lines. Toxicol In Vitro. 2004 Jun;18(3):365-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD´s guidelines for the testing of chemicals: 203 acute toxicity test for fish. Paris: OECD Publishing; 1992. 12 p. [Google Scholar]

- OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD´s guidelines for the testing of chemicals: 202 Daphnia sp., acute immobilisation test. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2004. 12 p. [Google Scholar]

- Pitter P. Vliv chemickeho slozeni vody, vcetne tzv. „tvrdosti“, na toxicitu kovu na vodni organismy [Effects of water chemistry including “hardness” on metal toxicity for aquatic organisms]. Vodní hospodářství. 1980 Aug;30(B):203-6. Czech. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin JW, Perlmutter A. Fish cells in culture for study of aquatic toxicants. Water Res. 1968 Aug;2(6):409-14. [Google Scholar]

- Rusche B, Kohlpoth M. The R1-cytotoxicity test as a replacement for the fish test stipulated in the German Waste Waters Act. In: Braunbeck T, Hanke W, Segner H, editors. Fish ecotoxicology and ecophysiology. Germany: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft; 1993. p. 81-92. [Google Scholar]

- Segner H. Cytotoxicity assay with fish cells as an alternative to the acute lethality assay with fish. Altern Lab Anim. 2004 Oct;32(4):375-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svobodova Z, Faina R. Aquatic testing of trichlorphon in the laboratory and field. In: Hill IR, Heimbach F, Leeuwangh P, Matthiessen P, editors. Freshwater field tests for hazard assessment of chemicals. Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers; 1994. p. 361-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tan F, Wang M, Wang W, Lu Y. Comparative evaluation of the cytotoxicity sensitivity of six fish cell lines to four heavy metals in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008 Feb;22(1):164-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]