Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the characteristics and molecular mechanisms of orbital fibroblasts under three-dimensional (3D)–culture conditions.

Methods

Orbital connective tissue was collected from patients with thyroid eye disease (TED) and normal controls. Primary fibroblasts were cultured and used to generate 3D microspheres via the hanging drop. These spheroids were cultured for nine days, followed by biomechanical testing, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and RNA sequencing for transcriptomic analysis. Multiplex immunofluorescence staining was used to assess fibrosis markers, and quantitative PCR validated gene expression changes. TED and normal control (NC) tissues, as well as primary cultured fibroblasts, were also subjected to transcriptomic sequencing.

Results

TED-3D microspheres exhibited enhanced contractility, denser fiber deposition, and a characteristic fibrous ring at the periphery. TEM revealed more extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and stronger tissue remodeling in TED-3D. Fibrosis markers (α-SMA, COL1A1, FN1) increased significantly in TED-3D. Biomechanical testing showed higher stiffness in TED-3D compared to NC-3D. Transcriptomic analysis revealed significant differences, with genes involved in ECM remodeling and fibrosis pathways enriched in TED-3D. Transcriptomic comparison of TED-tissue, TED-2D, and TED-3D revealed that TED-3D is closer to tissue than TED-2D.

Conclusions

The 3D culture of orbital fibroblasts from TED induces in vivo-like tissue remodeling and fibrosis features. Compared to traditional two-dimensional culture, the expression pattern of TED-3D is closer to tissue, making it a more effective model for studying the mechanisms of TED-related fibrosis.

Keywords: thyroid eye disease, orbital fibroblasts, 3D culture, tissue remodeling, fibrosis

Thyroid eye disease (TED), also known as Graves’ orbitopathy, is one of the most common orbital disorders in adults. TED is primarily characterized by exophthalmos, extraocular muscle hypertrophy, and eyelid retraction and can be associated with impaired vision, all of which significantly impact patients’ quality of life.1,2 Tissue remodeling and fibrosis are central pathological processes in the progression of TED, with fibroblasts playing a crucial role in fibrosis development.2,3 Orbital fibroblasts (OFs) in TED secrete large amounts of collagen, fibronectin, and other extracellular matrix (ECM) components. On differentiation into myofibroblasts, they further exacerbate ECM deposition and increase tissue stiffness, ultimately worsening orbital fibrosis.4,5 However, the molecular mechanisms underlying tissue remodeling and fibrosis in TED remain unclear. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) culture of OFs is a common model in the study of TED. Because of their characteristic monolayer growth in vitro, it cannot faithfully simulate intercellular interactions and cell/ECM connections, severely limiting in-depth studies of tissue remodeling and fibrotic processes in TED.6,7 Under 2D culture conditions, the morphology, function, and gene expression of cells often differ significantly from their in vivo counterparts, making it difficult to capture dynamic disease processes and pathological features.8 Currently, in vitro studies of TED require additional stimulants (such as TGF-β1) to simulate specific pathological features.9,10 Also, there is a lack of a simple and efficient animal model for TED. Existing animal modeling methods generally require more than six months to establish, with low success rates, high costs, and ethical concerns.11 Furthermore, because of genetic differences between animals and humans, these models cannot fully replicate the human gene expression patterns. Therefore the development of more physiological models has become a key focus in the study of TED mechanisms.

In recent years, three-dimensional (3D) culture models, including spheroid and organoid technologies, have demonstrated significant advantages in fibrosis disease research.12 The 3D microenvironment offers cells a more natural growth space, simulating in vivo tissue microstructures and mechanical conditions, enabling cells to spatially arrange and interact with one another and the ECM in a manner closer to the in vivo state.13–15 Moreover, 3D culture systems can induce fibroblasts to differentiate into myofibroblasts, promoting ECM synthesis and remodeling, thus offering an important platform for studying cellular behavior and the molecular mechanisms underlying tissue fibrosis.16 In studies of pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis, 3D-culture systems have successfully uncovered mechanisms of fibroblast activation, the regulatory role of mechanical signals, and the activation of associated signaling pathways.17–19 Previous studies have shown that OFs from TED patients exhibit distinct characteristics in 3D collagen matrices, with fibroblasts from TED patients demonstrating enhanced matrix contraction in 3D collagen gels.20 Yang et al.21 further promoted the fibroblastic contraction phenotype by introducing macrophages into 3D gels. Ichioka et al.22 successfully constructed 3D organoid cultures of OFs and used these cultures to elucidate the ocular effects of several anti-glaucoma drugs. Furthermore, Ida et al.23 found that the prostaglandin and the rho-associated coiled-coil kinase inhibitor ripasudil could regulate gene expression in OFs in spheroids. Further research revealed that human-specific monoclonal antibody could promote adipogenesis in 3D cultured 3T3-L1 cells, simulating the adipogenesis characteristic of TED.24 Hikage et al.25 investigated the role of the IGF1R inhibitor Linsitinib in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy using an in vitro 3D spheroid model, demonstrating that Lins had a significant impact on the biological functions. These studies indicate that OFs could form spheroids, which contribute to the exploration of TED. However, these studies lack a systematic comparison of the phenotypic and molecular changes after 3D culture. Furthermore, as a new in vitro model, it needs to be compared with the traditional 2D culture model to determine its similarity to the in vivo environment.

The aim of this study was to develop a 3D culture system using TED fibroblasts and normal control (NC) fibroblasts to systematically investigate the biological characteristics, fibrosis marker expression, ultrastructural changes, mechanical properties, and transcriptomic-level gene expression differences of TED orbital fibroblasts within a 3D microenvironment. Through a series of experiments, we explored the fibrotic characteristics and molecular regulatory mechanisms of TED orbital fibroblasts in the 3D microenvironment, comparing the differences between 3D and 2D cultures, as well as between TED-3D and NC-3D cultures. Furthermore, we compared the sequencing results from 2D-culture, 3D-culture, and tissue samples, and found that the transcriptomic expression pattern in 3D culture was closer to that of the tissue samples. Our findings show that TED orbital fibroblasts in 3D culture exhibit significant differences compared to 2D culture, and that 3D culture induces tissue remodeling and fibrosis resembling in vivo conditions, making it superior to traditional 2D culture models. The experimental design flow is shown in Figure 1. Our study provides a basis for the selection of in vitro models for TED and contributes to the systematic exploration of the effects of 3D culture on TED fibroblasts.

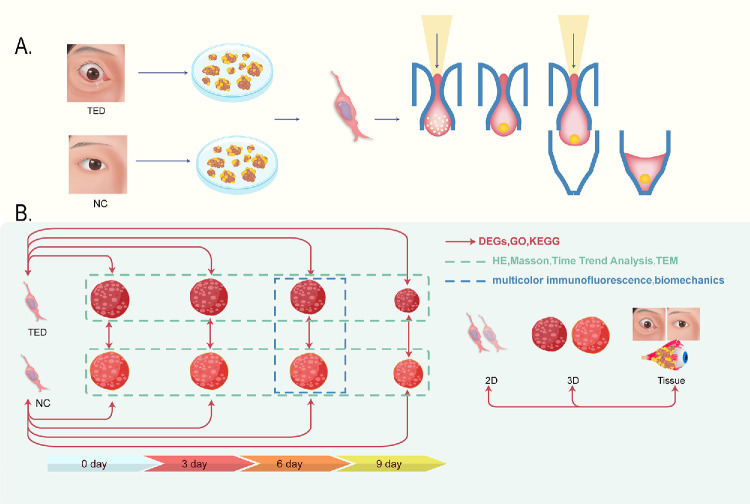

Figure 1.

Experimental design process. (A) Establishment of 3D microspheres using the hanging drop method. (B) Experimental group.

Material and Methods

Patient Collection

Orbital connective tissue samples were collected from 6 patients with thyroid eye disease (TED) and 6 normal control subjects, all obtained from the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, for primary cell culture and 3D spheroid culture. Additionally, orbital connective tissue samples from 6 TED patients and 6 control subjects were collected for PCR validation. For high-throughput RNA sequencing, orbital connective tissue was further collected from 12 TED patients and 6 control subjects. All TED patients met the criteria outlined by Bartley.26 Notably, patients who had received glucocorticoid or immunotherapy within the past 3 months were excluded, and none of the patients had undergone radiotherapy. Detailed patient information is provided in Table 1. All orbital connective tissue samples were collected during orbital decompression surgery, while the control group's adipose tissue was collected from patients undergoing enucleation due to intraocular tumors. All participants were fully informed about the study's purpose and provided written informed consent. This study adheres to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (2016KYPJ028).

Table 1.

Demographic Data of Orbital Connective Tissue Samples Used in This Research

| Clinical Characteristics | TED (n = 24) | Control (n = 18) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 45.33 ± 14.57 (24–72) | 49.61 ± 14.15 (28–77) | 0.345 |

| Sex | 0.764 | ||

| Male | 12 | 8 | |

| Female | 12 | 4 | |

| CAS | 1 (range 0–2) | — | NA |

| NOSPECS score | 4 (range 3–6) | — | NA |

CAS, Clinical Activity Score.

Age is reported as mean ± SD. CAS, NOSPECS score.

Cell Culture

Fresh orbital connective tissue was collected from the vessels, cut into small pieces, and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 1% streptomycin (100 mg/mL), and penicillin (100 mg/mL, Gibco) at 37°C for approximately 2 weeks. Primary orbital fibroblasts from passages 3 to 6 were used in subsequent experiments. It takes 5–6 days for the cells to reach 90% confluence.

3D Spheroid Culture

Once the cells reached approximately 90% confluence in culture dishes, they were washed, dissociated with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA, and resuspended in growth medium containing 0.25% w/v methylcellulose (TargetMol, Shanghai, China). Spheroids were cultured in the InSphero Akura PLUS Hanging Drop Culture System (InSphero, Zurich, Switzerland) for 2 days, then transferred to low-adhesion 96-well plates for the following culture.

3D Spheroid Multi-Color Immunofluorescence Staining

Spheroids were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, followed by paraffin embedding. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene and absolute ethanol, followed by rehydration with water. Antigen retrieval was performed in EDTA buffer (pH 8.0), followed by natural cooling and PBS washing. Sections were blocked with 3% BSA for 30 minutes, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C in a humidified chamber. The following day, sections were washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies at room temperature for 50 minutes in the dark. After washing, DAPI was used to stain the nuclei, and an anti-fade reagent was applied to reduce autofluorescence. Finally, the slides were mounted and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). All antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Biomechanical Testing of 3D Spheroids

The biomechanical properties of 3D spheroids were assessed using a nanoindentation testing system with a Berkovich pyramidal diamond indenter (BBJ-75) as the measurement probe. The maximum load was set to 20.00 mN, with loading and unloading rates of 20.00 mN/min, and the contact depth was set to 10000 nm. Both contact and retraction speeds were set to 20,000 nm/min, with a stiffness threshold of 100 µN/µm. Data were collected at a sampling frequency of 400 Hz, and force-displacement curves of the spheroids were analyzed to measure mechanical properties, including stiffness and the ratio of elastic to plastic work.

Transmission Electron Microscope Observation of 3D Spheroids

The 3D spheroids were fixed overnight in a 4% paraformaldehyde PBS solution, washed with PBS, and subsequently fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1–2 hours. The samples were then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%) and acetone, before embedding. After embedding, the samples were sectioned into approximately 100 nm thick ultrathin slices using an ultramicrotome, followed by staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Finally, the samples were examined and imaged using a transmission electron microscope (Tecnai G2 Spirit, Czech Republic).

RNA Isolation and Quality Control

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and confirmed by RNase-free agarose gel electrophoresis. After extraction, eukaryotic mRNA was enriched using Oligo(dT) beads.

RNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

The enriched mRNA was fragmented into short segments with a fragmentation buffer, followed by reverse transcription into cDNA using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB #7530, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The purified double-stranded cDNA fragments underwent end repair, an A-base was added, and Illumina sequencing adapters were ligated. The ligation products were purified using AMPure XP Beads (1.0X), and the cDNA library was subsequently amplified by PCR. The resulting library was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform (Repugene Technology, Hangzhou, China). Bioinformatics analysis was conducted using R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from 3D spheroids using a kit (ESscience, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized from RNA using PrimeScript RT Premix (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The relative expression levels of RNA were detected using the Roche LightCycler 480 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), with TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) used as the PCR reaction system. The primer sequences are listed in Table 2. GAPDH was used as the reference gene for data normalization.

Table 2.

Primer Sequences of Genes for q-PCR

| Genes | Sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| BARX1 | F: GAAAATAGTGCTGCAGGGCG |

| R: CTGCTCGCTCGTTGGAATTG | |

| SIM2 | F: CAGGAAGGGCAGGAGAGC |

| R: CGCTGCTTACTCCTTCGTCG | |

| PAX3 | F: GCCGTCAGTGAGTTCCATCA |

| R: CTCCAAGTCACCCAGCAAGT | |

| PLN | F: CAGCTGCCAAGGCTACCTAA |

| R: TTTGACGTGCTTGTTGAGGC | |

| FOXS1 | F: TGAGTAAAGGCAGCCTCACC |

| R: GCTGGGTCCTTCGAGAGTTC | |

| GAPDH | F: TTGCCATCAATGACCCCTT |

| R: CGCCCCACTTGATTTTGGA | |

| TFAP2B | F: TCTATGAGGACCGGCACGAT |

| R: CTCGAGTAGGGTCCTTGGGA | |

| ODAD2 | F: GTTGACCCGCGTCCTAGC |

| R: TTCCTCAGAGCCACACCCAT | |

| FENDRR | F: AATTGCAGATCCTCCCGTGG |

| R: GTAGGATAATCCCGGCTCGC | |

| THBS4 | F: AGGAGCAGCTTGGCCTAAAG |

| R: GCCTCTGACTGGAAGATGGG | |

| DACT2 | F: AGAGAGGAGGCGCAGGAG |

| R: GTCTCATCAACCGACCGGG |

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis and graphical representation were performed using GraphPad Prism (Prism 8.0.1, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The t-test was used to compare quantitative data between two groups. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Establishment of 3D Culture of Orbital Fibroblasts

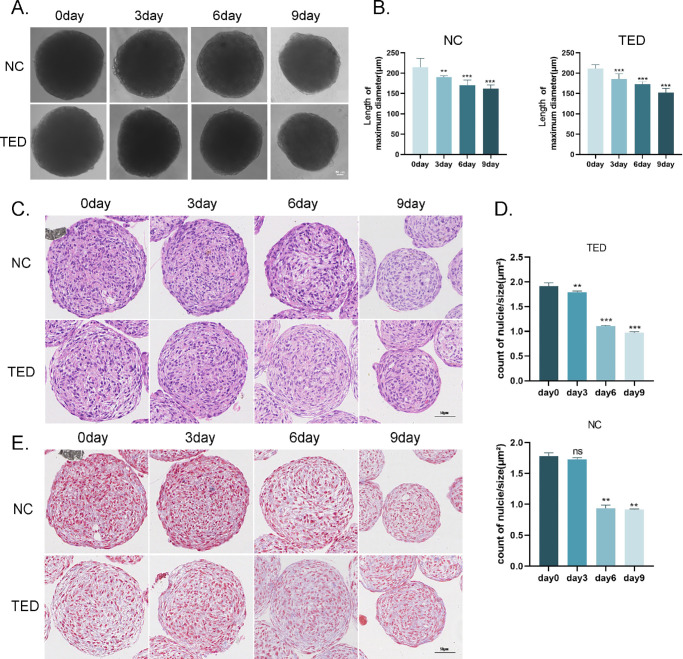

To construct and observe the 3D culture model of fibroblasts from TED and normal controls (NC), we used the hanging drop method to generate microspheres. After 48 hours of primary cell suspension culture, the microspheres were transferred to low-attachment 96-well plates (defined as Day 0) and cultured until Day 9. Microspheres were collected every three days for histological analysis and subsequent experiments. During the culture process, continuous observation of the microspheres was performed using an optical microscope (Fig. 2A). The results showed that the TED-3D microspheres gradually decreased in diameter and contracted from Day 0 to Day 6. The NC-3D group exhibited a similar trend. By Day 9, both TED-3D and NC-3D showed significant wrinkling of the microspheres. Quantitative analysis of the microsphere diameters (Fig. 2B further confirmed that the contraction in the TED group was significantly higher than that in the NC group. HE staining of tissue sections (Fig. 2C) showed that the TED microspheres were denser, with compactly arranged cells in the center and a variety of shapes. Notably, the TED group exhibited typical fusiform cell arrangement at the edge of the microspheres, with lighter nuclear staining, while the NC group had a looser cell structure with no obvious changes at the edges. Quantitative analysis of the HE staining images (Fig. 2D) further indicated the nuclear density in the TED-3D and NC-3D at time points. Masson staining results (Fig. 2E) showed that the TED group had denser fiber deposition, with a multilayered distribution pattern, especially at Day 6 and Day 9, where fibrous tissue was notably increased in the peripheral regions. We successfully established a 3D culture system for primary TED and NC fibroblasts. The TED group showed more obvious contraction, fusiform cell arrangement at the edges, and higher cell density with characteristic fiber arrangement during the culture process. We observed that the microsphere shape gradually improved and the volume gradually decreased from Day 0 to Day 6, but significant wrinkling occurred on Day 9. Based on these observations, we chose Day 6 as the key time point for subsequent biomechanical testing and multicolor fluorescence analysis.

Figure 2.

Establishment of 3D culture of orbital fibroblasts. (A) Light microscope image of microsphere culture. (B) Quantitative analysis of microsphere diameter. (C) H&E staining of microspheres. (D) Quantitative analysis of microsphere density. (E) Masson staining of microspheres. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns: not significant, compared to the control group. Scale bar: 50 µm

Microscopic Structural Changes in TED-3D and NC-3D culture

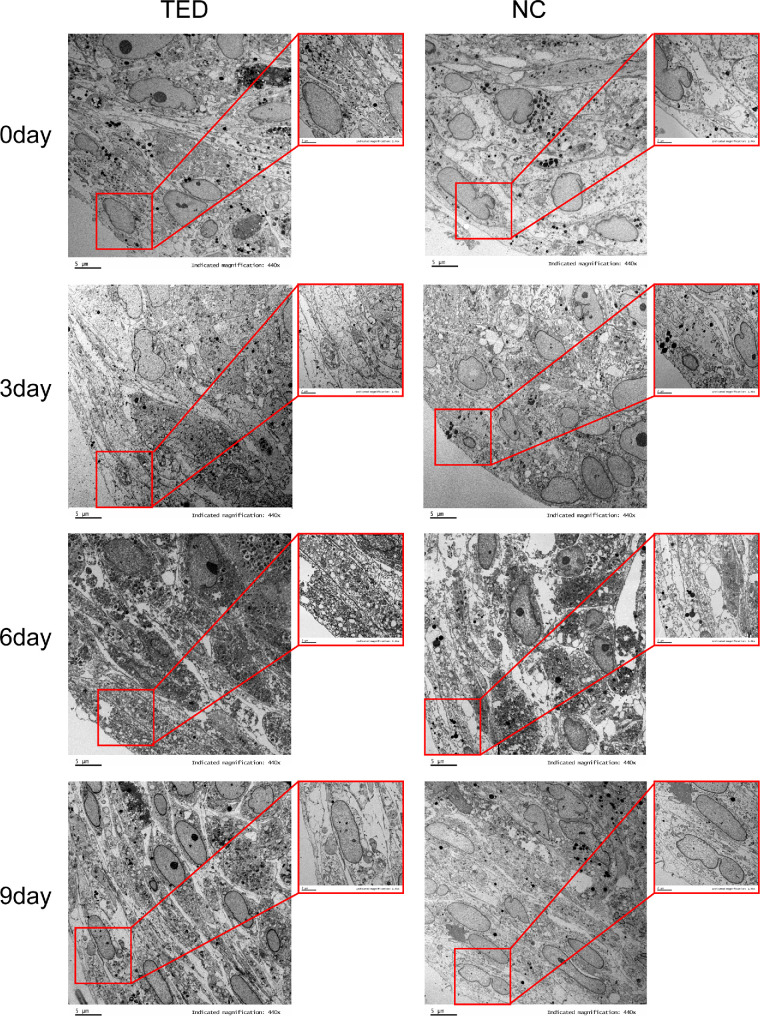

Samples from the 3D cultures were taken on Days 0, 3, 6, and 9, and the edge and center regions of the cell spheres were observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM images of the edge regions are shown in Figure 3, whereas the center region images are provided in Supplementary Figure S1. On Day 0, the cells in the TED group were arranged in a uniform direction with small intercellular spaces, forming a regular linear tissue structure. Local fusion was observed, with prominent nucleoli and numerous high-electron-density granules in the cytoplasm. In contrast, the cells in the NC group were arranged more loosely, with diverse nuclear shapes, including lobed or kidney-shaped structures, and no noticeable bundled structures or significant deposits were observed. On Day 3, the cells in the TED group were highly packed with abundant organelles. Distinct ECM deposition was present between the cells, and intercellular gaps were filled with bundled fibrous structures. In contrast, the NC group showed larger intercellular spaces, with a relatively loose arrangement and more independent tissue structure. On Day 6, the cells in the TED group were arranged more densely, with fusiform shapes and numerous vesicles in the cytoplasm. The intercellular filling structure became more organized. In the NC group, the cells were arranged with moderate density, and the cytoplasm and organelle structures were clearly visible. By Day 9, the cells in the TED group exhibited a further enhanced arrangement with a more defined directional alignment and increased ECM deposition. Although some organized structure was observed in the NC group, noticeable intercellular spacing remained. In the center region of the cell spheres, the structural differences between the TED and NC groups were relatively small, but the cells in the TED group were more tightly packed, with prominent nucleoli and higher contents of organelles such as lysosomes. This further supported the observation that cells in the TED group exhibited a stronger tissue remodeling ability in 3D culture.

Figure 3.

Microscopic structural changes in TED-3D and NC-3D culture.

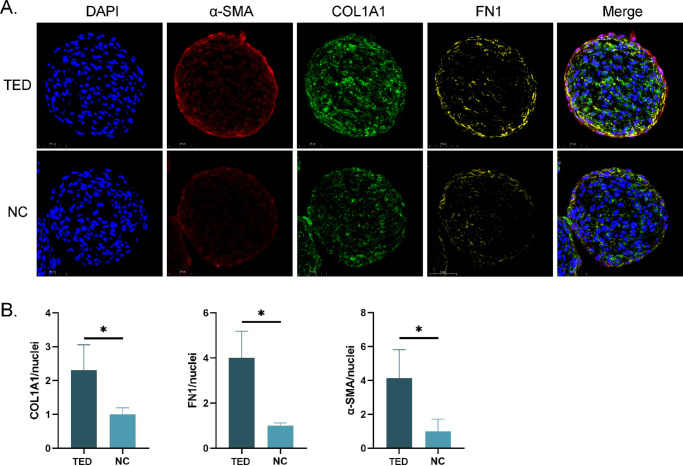

TED-3D Culture Induces Tissue-like Fibrotic Features

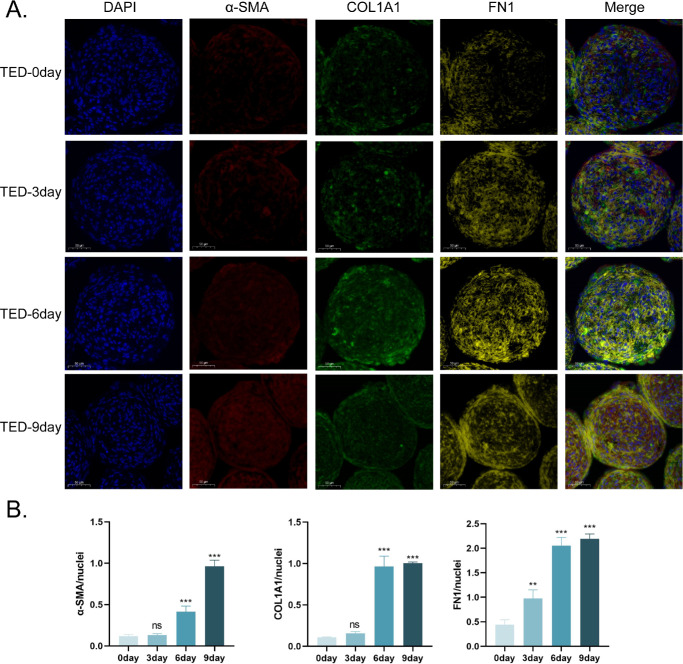

To further investigate the expression differences of fibrosis markers between the TED and NC groups under 3D culture conditions, multiplex immunofluorescence staining was performed on the microspheres. The results showed that with the extension of the culture time, the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), type I collagen (COL1A1), and fibronectin (FN1) significantly increased in the TED group. Specifically, the expression of α-SMA and COL1A1 started to rise significantly from Day 6 and further increased on Day 9, whereas the expression of FN1 began to increase on Day 3, indicating a delayed onset of different fibrosis markers over time (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analysis further confirmed this observation (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the expression of fibrosis markers in the NC group also increased, but the changes were not significant (Supplementary Fig. S2). We further compared the expression differences between TED-6d and NC-6d, and the results showed that the expression levels of α-SMA, COL1A1, and FN1 were significantly higher in the TED-3D group compared to the NC-3D group (Fig. 5A). Quantitative analysis also supported this observation (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, we found that the distribution of these fibrosis markers was not uniform within the cell spheres. α-SMA and FN1 were primarily concentrated at the periphery of the cell spheres, suggesting a higher degree of fibrosis in the edge regions, whereas COL1A1 was more evenly distributed throughout the entire cell sphere. This distribution pattern may reflect the active ECM remodeling and contraction activities of TED cells in 3D culture, particularly at the periphery of the spheres where fibrosis is more pronounced, possibly associated with stronger metabolic activity and mechanical stimulation in the edge regions of the cells.

Figure 4.

Fibrosis marker staining in TED microspheres. (A) Multicolor fluorescence staining of TED at different culture times. (B) Quantitative fluorescence analysis. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns: not significant, compared to the control group. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 5.

Fibrosis marker staining in TED and NC microspheres. (A) Multicolor fluorescence staining of TED and NC microspheres in six days. (B) Quantitative fluorescence analysis. *P < 0.05, compared to the control group. Scale bar: 50 µm.

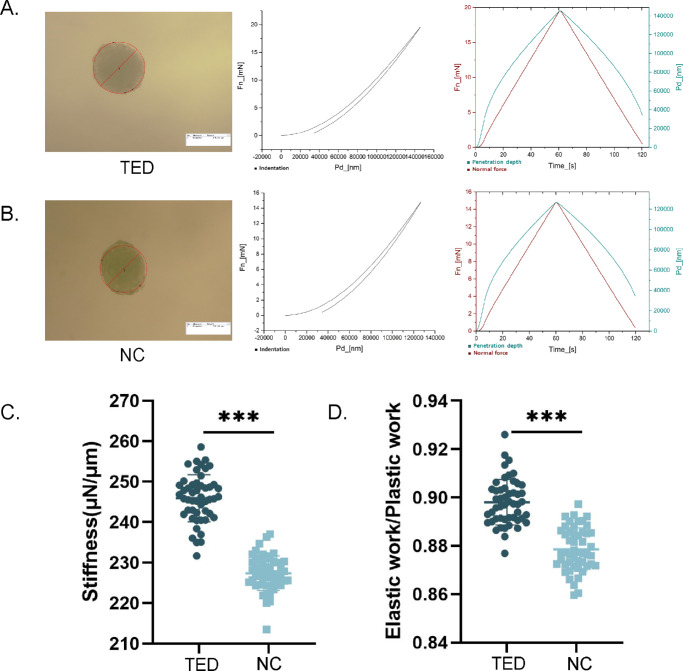

Stiffness Changes Induced by TED Fibroblasts

Nanoindentation tests were conducted to investigate the mechanical properties of TED-3D and NC-3D samples. Figures 6A and 6B show the force-displacement and force-time curves for TED-3D and NC-3D cultures. The TED-3D curves showed significant differences compared to the NC-3D group (Fig. 6B), with TED-3D exhibiting greater mechanical stiffness. Quantitative analysis revealed that the stiffness of the TED-3D group was significantly higher than that of the NC-3D group. Additionally, the elastic/plastic work ratio in the TED-3D group was significantly higher than in the NC-3D group, indicating greater elasticity in the TED-3D spheroids under 3D culture conditions.

Figure 6.

Biomechanical analysis of microspheres. (A) Nanoindentation experiments of TED-3D and NC-3D cultures. On the right, force-displacement and force-time curves for TED-3D. (B) Quantitative analysis of stiffness and elasticity of the 3D cultures. ***P < 0.001.

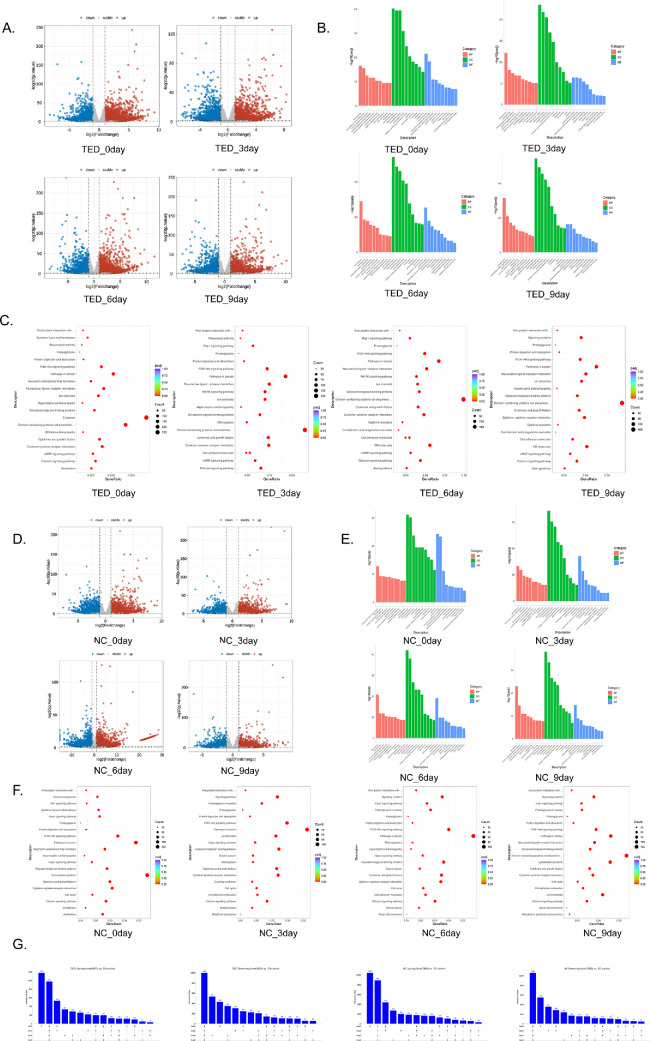

Transcriptomic Changes Between 3D and 2D Cultures

To analyze the expression changes in the 3D culture, we performed transcriptome sequencing for the TED-3D and NC-3D groups at each time point and compared them with the 2D cell sequencing results. The analysis revealed significant gene expression differences between TED-3D and NC-3D compared to TED-2D and NC-2D (Figs. 7A, 7D; Tables 3, 4). Table 5 lists the top five differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that were upregulated and downregulated in TED-3D across different time points, while Table 6 shows the top five DEGs for NC-3D at various time points. To further explore the potential biological functions of these genes and their associated signaling pathways, we conducted gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses (Figs. 7B, 7E). The GO enrichment analysis results showed that under TED-3D culture conditions, cell functions underwent significant changes over time, reflecting a typical tissue remodeling process. The relevant pathways primarily focused on “cell adhesion,” “extracellular region,” and “plasma membrane,” which are involved in structural maintenance, and the enrichment significance gradually increased as the culture extended. By Day 6, the pathway enrichment was significantly concentrated on “collagen-containing extracellular matrix,” “extracellular space,” and “extracellular matrix,” with a similar trend observed at Day 9, although the significance slightly decreased. The KEGG pathway analysis indicated that from Day 0 to Day 3, the main enrichment was in the “Calcium signaling pathway” and “Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction.” On Day 3, there was significant enrichment in fibrosis-related pathways such as the “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway.” By Day 9, in addition to the previous pathways, there was also new enrichment in signaling pathways related to tissue repair, such as “Ion channels.” (Figs. 7C, 7F) The TED and KEGG enrichment results for the NC-3D group were similar to those of the TED-3D group, also concentrating mainly on ECM and membrane structure-related pathways. However, the significance was considerably lower in the NC group compared to the TED group. Additionally, we used an UpSet plot to analyze the intersection of upregulated and downregulated genes under TED-3D and NC-3D conditions (Fig. 7G). The results showed that at Day 0, both TED-3D and NC-3D groups exhibited significant gene expression changes, suggesting that the initial response was the most intense, followed by stabilization over time. Overall, both TED and NC treatments led to extensive transcriptomic changes in fibroblasts under 3D culture conditions, primarily focusing on ECM, fibrosis-related functions, and pathways.

Figure 7.

Transcriptomic analysis at different time points of TED-3D vs TED-2D and NC-3D vs NC-2D. (A) Volcano plot of differential gene analysis between TED-3D and TED-2D. (B) GO analysis of differential genes between TED-3D and TED-2D. (C) KEGG analysis of differential genes between TED-3D and TED-2D. (D) Volcano plot of differential gene analysis between NC-3D and NC-2D. (E) GO analysis of differential genes between NC-3D and NC-2D. (F) KEGG analysis of differential genes between NC-3D and NC-2D. (G) UpSet plot of differential genes between TED and NC.

Table 3.

Number of DEGs in TED_3D Versus TED_2D Comparisons

| DEGs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparisons | Up | Down | Total |

| 3D_Day0 vs. 2D | 3432 | 2209 | 5641 |

| 3D_Day3 vs. 2D | 2259 | 2155 | 4414 |

| 3D_Day6 vs. 2D | 2172 | 2566 | 4738 |

| 3D_Day9 vs. 2D | 2199 | 2146 | 4345 |

Table 4.

Number of DEGs in NC_3D Versus NC_2D Comparisons

| DEGs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparisons | Up | Down | Total |

| 2D vs. 3D_Day0 | 2942 | 2340 | 5282 |

| 2D vs. 3D_Day3 | 2068 | 2235 | 4303 |

| 2D vs. 3D_Day6 | 1822 | 1853 | 3675 |

| 2D vs. 3D_Day9 | 1826 | 1975 | 3801 |

Table 5.

Top Five DEGs (Ranked by Fold Change) at Each Time Point in TED_3D Versus TED_2D

| Up-Regulation | Down-Regulation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 0 day | NOTUM | CXCL8 | CSF3 | FOSB | ODAM | PKD1L2 | LINC00906 | PSG1 | ABCB5 | IL26 |

| 3 day | NOTUM | FOSB | SLC16A6 | CDH23 | KCNK3 | IL26 | PSG1 | RASGRF1 | PSG11-AS1 | PSG5 |

| 6 day | COL10A1 | MMP13 | JPH3 | LINC01929 | SLC16A6 | CPA1 | MYPN | ANGPTL7 | LINC01085 | PSG1 |

| 9 day | COL10A1 | SLC16A6 | JPH3 | LINC01929 | NOTUM | CPA1 | LINC01111 | MYPN | CCDC190 | PSG3 |

Table 6.

Top Five DEGs (Ranked by Fold Change) at Each Time Point in NC_3D Versus NC_2D

| Up-Regulation | Down-Regulation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 0 day | NOTUM | PMCH | SNORD114-20 | CXCL8 | PCK1 | LINC00906 | CPA4 | PLCE1-AS1 | PSG1 | LINC01111 |

| 3 day | NOTUM | FOSB | PMCH | VSIG4 | LINC02392 | PSG1 | PLCE1-AS1 | CPA4 | THSD7B | ANKRD1 |

| 6 day | DLK1 | FOSB | SLC16A6 | LINC02392 | NR4A1AS | IL18 | LYPD6B | KLK5 | CPA4 | THSD7B |

| 9 day | LINC02392 | SPP1 | SLC16A6 | DLK1 | FOSB | CPA4 | LINC01111 | THSD7B | KRT223P | MYPN |

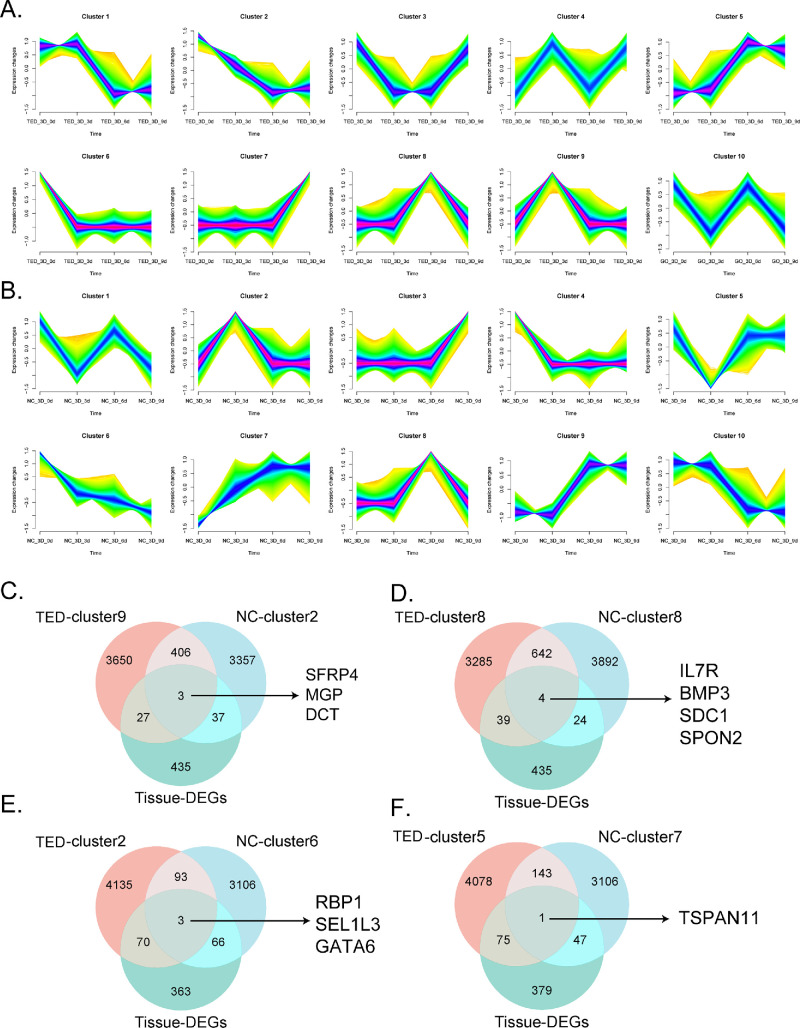

Time Trend Sequence Analysis of TED-3D and NC-3D

To investigate the dynamic gene expression patterns of fibroblasts under 3D culture conditions, time-series clustering analysis was performed on the TED-3D and NC-3D groups to explore genes with similar expression trends over time (Figs. 8A, 8B). Ten expression clusters were identified for each group. We selected cluster 2 (continually decreasing), cluster 5 (continually increasing), cluster 9 (peak at Day 3), and cluster 8 (peak at Day 6) from the TED-3D group for further study. The top genes of several clusters are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Furthermore, we intersected the characteristic clusters of TED-3D and NC-3D with the differentially expressed genes from TED tissue sequencing to explore common trend genes with opposing expression patterns or specific peaks in TED and NC (Figs. 8C–F). The TED tissue sequencing results were based on our previous research.27 The Venn diagram results revealed shared genes across multiple clusters, including SFRP4, MGP, DCT (intersection of TED-cluster9 and NC-cluster2, both reaching peak expression at Day 3), IL7R, BMP3, SDC1, SPON2 (intersection of TED-cluster8 and NC-cluster8, both reaching peak expression at Day 6), RBP1, SEL1L3, GATA6 (intersection of TED-cluster2 and NC-cluster6, with opposite expression trends), and TSPAN11 (intersection of TED-cluster2 and NC-cluster7, with similar expression trends). These intersecting genes may serve as key nodes in the TED-specific regulatory network.

Figure 8.

Time trend analysis of TED-3D and NC-3D. (A) Time trend analysis of TED-3D. (B) Time trend analysis of NC-3D. (C) Intersection of differential genes between TED-cluster9, NC-cluster2, and tissue sequencing. (D) Intersection of differential genes between TED-cluster8, NC-cluster8, and tissue sequencing. (E) Intersection of differential genes between TED-cluster2, NC-cluster6, and tissue sequencing. (F) Intersection of differential genes between TED-cluster5, NC-cluster7, and tissue sequencing.

A 3D Culture Model Closely Resembling Real Tissue at the Transcriptomic Level, Superior to 2D Model

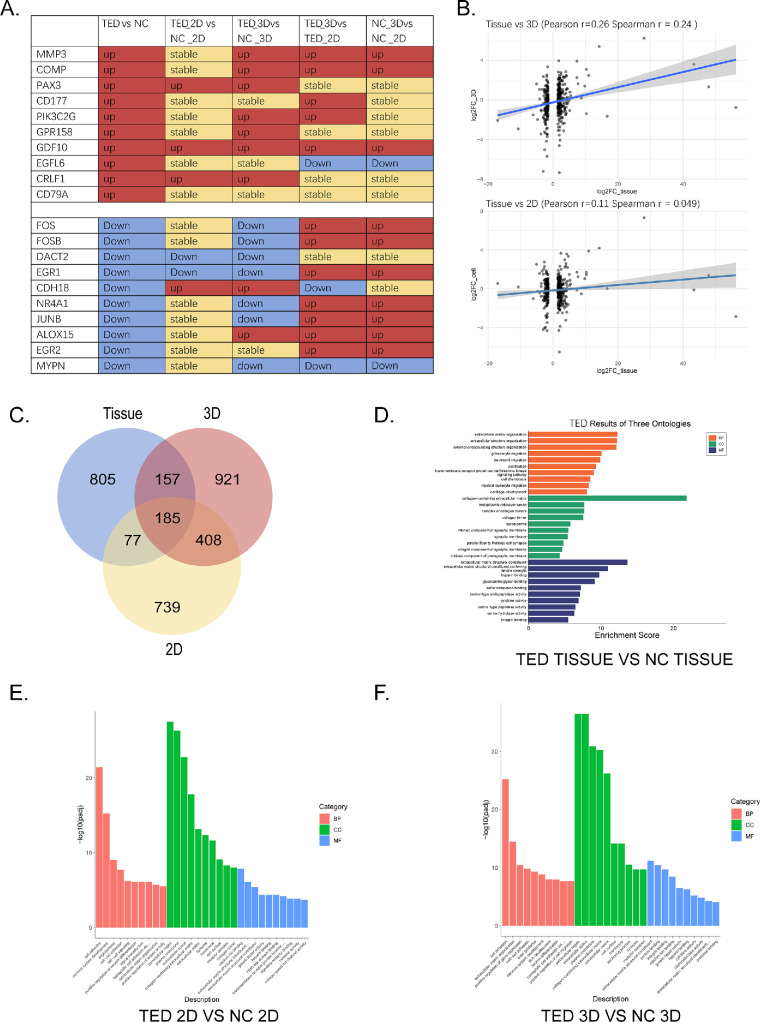

To compare the differences between 3D and 2D samples at different time points, as well as their consistency with tissue sequencing samples, we compared the transcriptomic profiles of the following three groups: TED-tissue versus NC-tissue, TED-2D versus NC-2D, TED-3D versus NC-3D. Figure 9A shows the trend changes of the top differential genes in the TED-tissue versus NC-tissue sequencing results across other groups. The results indicate that the differential gene expression pattern in TED-3D versus NC-3D is similar to that in tissue sequencing, whereas the TED-2D versus NC-2D comparison shows greater discrepancies with tissue sequencing results. Further correlation analysis revealed that the correlation between tissue samples and the 3D model was higher (r = 0.26) compared to 2D samples (r = 0.049) (Fig. 9B), suggesting that 3D culture conditions more effectively simulate the in vivo environment.

Figure 9.

Comparison of TED tissue transcriptomic sequencing, TED-3D transcriptomic sequencing, and TED-2D transcriptomic sequencing. (A) Trend analysis of differential genes from TED tissue sequencing in 3D and 2D cultures. (B) Comparison of the correlation between 3D culture, 2D culture, and tissue samples. (C) Intersection of GO pathways for differential genes in TED tissue sequencing, TED-3D sequencing, and TED-2D sequencing. (D) GO analysis of TED tissue sequencing. (E) GO analysis of TED-2D sequencing. (F) GO analysis of TED-3D sequencing.

We performed GO analysis on the differentially expressed genes in TED and NC groups under tissue, 2D, and 3D culture conditions, and conducted an intersection analysis of the identified pathways. The results showed that more GO enrichment results were shared between 3D culture conditions and tissue samples (Fig. 9C). The GO enrichment analysis indicated that the differentially expressed genes in tissue samples were primarily enriched in biological processes related to the ECM, such as ECM organization and extracellular structure organization, as well as cell adhesion functions (Fig. 9D). GO analysis for both 2D and 3D cultures was also predominantly enriched in these functions (Figs. 8E, 9F). However, the ECM composition and structural maintenance-related GO terms showed higher significance under 3D culture conditions.

We further analyzed the differential expressions in TED-3D and NC-3D at each time point, followed by GO and KEGG analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3). The results showed that the differential genes in TED-3D versus NC-3D were mainly enriched in functions related to cell adhesion and the extracellular region, and the significance of enrichment gradually increased with the culture time. KEGG analysis further revealed that the major enriched pathways in TED-3D versus NC-3D were Wnt-signaling pathway and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, both of which have been extensively studied in TED. Table 7 shows the top five upregulated and downregulated genes in the TED-3D versus NC-3D comparison. We also validated the differential genes at Day 6 using q-PCR, and the results were consistent with the transcriptome sequencing data (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Table 7.

Top Five DEGs (Ranked by Fold Change) at Each Time Point in TED_3D Versus NC_3D

| Up-Regulation | Down-Regulation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 0 day | BARX1 | PAX3 | SIM2 | LHX8 | EPYC | FENDRR | MKX | LINC02192 | DACT2 | ODAD2 |

| 3 day | BARX1 | SIM2 | PAX3 | LHX8 | ADGRB3 | ODAD2 | THBS4 | MKX | TFAP2B | LINC02192 |

| 6 day | BARX1 | SIM2 | PAX3 | PLN | FOXS1 | TFAP2B | ODAD2 | FENDRR | THBS4 | DACT2 |

| 9 day | BARX1 | SIM2 | PAX3 | SLC35D3 | FOXS1 | TFAP2B | BPIFB4 | SHOX | DACT2 | LEFTY2 |

Discussion

TED, one of the most prevalent orbital disorders in adults, is characterized by tissue remodeling and fibrosis, both of which are central to its pathogenesis.1 Fibroblast activation and ECM deposition play crucial roles in disease progression. Although significant advances have been made in developing targeted therapies that reduce inflammatory responses during the active phase of TED, the mechanisms underlying late-stage fibrosis remain poorly understood.28 Traditional 2D culture models, although widely used, fail to accurately simulate the in vivo microenvironment. These 2D systems lack the complex interactions between cells and ECM, resulting in considerable discrepancies in cell morphology, function, and gene expression compared to in vivo conditions.29–31 Wu et al.32 compared TED fibroblasts with healthy controls fibroblasts, revealing that both cell types exhibited similar migratory abilities and comparable expression of fibrosis markers such as FN1) and α-SMA. Current in vitro studies on TED often require the addition of stimulants, such as IL-1β or TGF-β1, to induce pathological features.33,34 Given that 2D cultures cannot inherently replicate key characteristics of tissue remodeling and fibrosis, the development of a more physiologically relevant 3D culture model is essential for gaining deeper insights into fibroblast behavior and the molecular mechanisms driving tissue remodeling and fibrosis in TED.

In recent years, 3D-culture technologies, including microsphere and organoid models,7 have made significant progress in cell biology and disease modeling. These technologies better simulate the in vivo tissue microenvironment by providing a more accurate representation of the three-dimensional structure and mechanical environment, enabling realistic simulation of cell spatial arrangements and mechanical signaling.35 This model allows for dynamic observation of changes in cell behavior, such as the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and the synthesis and remodeling of the ECM. The application of 3D models has been widespread in various research areas, including oncology, regenerative medicine, and fibrosis diseases.36–41 Previous studies have shown that fibroblasts from TED patients possess good spheroid-forming ability. Some research teams have successfully used this property to develop TED microsphere models for drug performance validation.20–25 However, despite this progress, research on the ultrastructural features and transcriptomic characteristics of TED-3D cultures is still relatively limited. As a promising in vitro model for TED, the TED-3D culture system not only requires further exploration of its unique ultrastructural and gene expression characteristics but should also be compared in detail with traditional 2D culture models to assess its superiority in simulating the vivo environment.

In this study, we used the hanging drop method to develop a 3D culture model for TED and NC fibroblasts. We systematically analyzed the morphological changes, fibrosis marker expression, ultrastructural characteristics, biomechanical properties, and transcriptomic differences of TED fibroblasts in the 3D microenvironment. Our results showed that TED fibroblasts exhibited enhanced contractility under 3D culture conditions. TED microspheres displayed tighter cellular arrangements and significantly increased ECM fiber deposition. Interestingly, the edges of TED microspheres exhibited a characteristic fibrous ring-like structure. We found that TED-3D cultures spontaneously induced tissue remodeling features, with the expression of fibrosis markers such as α-SMA, COL1A1, and FN1 gradually increasing over time and being significantly higher than in the NC group. Notably, α-SMA and FN1 were primarily concentrated at the surface of the microspheres, whereas COL1A1 exhibited a more uniform distribution throughout the microsphere. This uneven spatial distribution may reflect the mechanical stress gradients that the cells experience. Previous studies have shown that mechanical stretch signals can activate myofibroblasts, and cells at the surface of the microspheres experience higher mechanical tension.41–43 TEM revealed ultrastructural changes in both TED-3D and NC-3D cultures. Over time, the edge structures of TED microspheres became tighter, accompanied by increased ECM deposition. Biomechanical studies confirmed that the stiffness and elasticity of TED microspheres were significantly higher than those of the NC group. These results suggest that TED-3D can spontaneously induce tissue remodeling features, and there are significant differences compared to NC-3D.

Transcriptomic analysis compared gene expression changes at different time points between TED-3D and NC-3D cultures, with comparison to 2D-culture. Notably, 3D culture led to the upregulation of several differentially expressed genes, such as NOTUM, COL10A1, and LINC01929, which were upregulated at Day 0 and Day 3, suggesting their role as broad response factors involved in initial adaptive changes in cell morphology, adhesion, and ECM regulation. FOSB exhibited sustained upregulation in TED-3D cultures, whereas changes in the NC group were slower, indicating a stronger response in TED fibroblasts under 3D culture conditions. GO and KEGG pathway analyses revealed that 3D culture primarily enriched pathways related to ECM and membrane structures, with the TED group showing more significant enrichment. The UpSet plot summarized the trends in differential genes, showing that most genes underwent drastic changes at Day 0 (48 hours after hanging drop culture), after which they gradually stabilized.

We conducted a time-trend analysis of TED-3D and NC-3D groups at various time points and observed distinctive gene clusters. We also performed intersection analysis with tissue sequencing results, identifying genes such as SFRP4, MGP, and DCT that peaked at Day 3 and maintained low levels at other time points. These genes, involved in pathways like Wnt signaling (SFRP4),44 calcification regulation (MGP),45 and melanogenesis (DCT),46 exhibited consistent expression trends in both TED and NC groups, indicating their common role in responding to the 3D culture environment and possibly regulating ECM stability and cell adaptability. The expression of four genes (IL7R, BMP3, SDC1, and SPON2) peaked on Day 6 in the TED-3D culture model. IL7R is involved in immune responses, indicating its potential role in regulating immune reactions during TED fibrosis.47 BMP3, SDC1 and SPON2 are factors that promote cell proliferation and ECM synthesis.48–50 We also identified genes with opposite expression trends between TED-3D and NC-3D cultures. For example, the expression of RBP1, SEL1L3, and GATA6 continuously decreased in the TED group, while increasing in the NC group.51–53 The downregulation of RBP1 may affect vitamin A metabolism, SEL1L3 depletion may relate to ER stress, and GATA6 downregulation may impair cell development and repair. TSPAN11, which was continuously upregulated in TED, may promote fibroblast migration and fibrosis, enhancing pathological remodeling in TED tissues.54 In contrast, its downregulation in the NC group may help maintain the stability of normal cells and tissue repair.

We also focused on analyzing the differential genes between TED-3D and NC-3D and validated the top five upregulated and downregulated genes at Day 6 using qRT-PCR. We found that the top five upregulated genes in the TED-3D model were BARX1, SIM2, PAX3, PLN, and FOXS1. The upregulation of these genes may be closely related to cell proliferation, migration, and tissue remodeling during TED fibrosis. BARX1 is involved in embryonic development and cell fate determination, possibly reflecting the transformation of fibroblasts in fibrosis.55 SIM2 is associated with neural development and may affect fibroblast proliferation and migration.56 PAX3 plays an important role in cell migration and proliferation and may promote the transition of fibroblasts to a fibrotic phenotype.57 PLN is related to adaptation to mechanical tension, which may enhance cellular contractility, whereas FOXS1 regulates the cell cycle and repair processes, potentially driving fibrosis progression.58

More importantly, we compared the transcriptomic results from TED tissue, 2D cells, and 3D culture models for the first time. We found that compared to traditional 2D culture sequencing, the gene expression profile in 3D culture more closely resembles that of the in vivo tissue samples. Notably, the top genes that were upregulated and downregulated in the tissue samples were more accurately simulated in the 3D culture model. Additionally, the correlation between 3D culture and tissue samples is higher. GO analysis revealed that functions related to extracellular matrix and tissue remodeling were more highly enriched in the 3D group. These results highlight the superiority of 3D culture in mimicking the in vivo environment, making 3D sequencing a more reliable and physiologically relevant in vitro model for TED research.

In conclusion, this study successfully established a 3D culture model for TED and NC fibroblasts (TED-3D and NC-3D), providing insights into the morphological, molecular, and biomechanical changes occurring under 3D culture conditions. Our extensive transcriptomic analysis revealed significant alterations in gene expression during the 3D culture process, with the 3D model more closely resembling in vivo conditions than 2D culture. Although the 3D culture model presents significant advantages in simulating TED cell behavior and the microenvironment, it still faces technical challenges and limitations, such as the complexity of construction and maintenance, high costs, and the lack of blood supply and metabolic environment.59,60 Furthermore, a larger sample size is still needed to validate the stability of TED-3D. Considering the differences between 2D cultures and the vivo environment, as well as the lengthy modeling time and ethical concerns associated with animal models, the 3D culture model stands out as a promising alternative for TED research. It offers significant potential for advancing our understanding of disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of Core Facilities at State Key Laboratory of Ophthalmology, Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center for technical support.

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (8237109, and Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (SL2023A03J00480, Clinical High-tech and Major Technology Projects in Guangzhou (2024P-GX13).

Disclosure: X. Bao, None; Z. Xu, None; X. Wang, None; T. Zhang, None; H. Ye, None; H. Yang, None

References

- 1. Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362: 726–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lazarus JH. Epidemiology of Graves’ orbitopathy (GO) and relationship with thyroid disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 26: 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sahli E, Gunduz K. Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2017; 47: 94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor PN, Zhang L, Lee RWJ, et al.. New insights into the pathogenesis and nonsurgical management of Graves orbitopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020; 16: 104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith TJ, Hegedus L, Douglas RS, Role of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) pathway in the pathogenesis of Graves’ orbitopathy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 26: 291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li X, Lwin KT, Kumarasinghe HU, et al.. Quantifying biomass and visualizing cell coverage on fibrous scaffolds for cultivated meat production. Curr Protoc. 2024; 4(12): e70076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birtele M, Lancaster M, Quadrato G, Modelling human brain development and disease with organoids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2025; 26: 389–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu R, Chen R, Tu C, et al.. 3D models of sarcomas: the next-generation tool for personalized medicine. Phenomics. 2024; 4: 171–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang S, Wang X, Xiao W, et al.. Dihydroartemisinin exerts antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects in Graves’ ophthalmopathy by targeting orbital fibroblasts. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022; 13: 891922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li H, Ma C, Liu W, et al.. Gypenosides protect orbital fibroblasts in Graves ophthalmopathy via anti-inflammation and anti-fibrosis effects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020; 61(5): 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shen F, Liu J, Fang L, et al.. Development and application of animal models to study thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2023; 230: 109436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma SC, Xie YL, Wang Q, et al.. Application of eye organoids in the study of eye diseases. Exp Eye Res. 2024; 247: 110068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Egorova VV, Lavrenteva MP, Makhaeva LN, et al.. Fibrillar hydrogel inducing cell mechanotransduction for tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules. 2024; 25: 7674–7684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malandrino A, Zhang H, Schwarm N, et al.. Plasticity of 3D hydrogels predicts cell biological behavior. Biomacromolecules. 2024; 25: 7608–7618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicolas R, Bonnin MA, Blavet C, et al.. 3D-environment and muscle contraction regulate the heterogeneity of myonuclei. Skelet Muscle. 2024; 14: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Phatak VM, Croft SM, Rameshaiah Setty SG, et al.. Expression of transglutaminase-2 isoforms in normal human tissues and cancer cell lines: dysregulation of alternative splicing in cancer. Amino Acids. 2013; 44: 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nizamoglu M, Alleblas F, Koster T, et al.. Three dimensional fibrotic extracellular matrix directs microenvironment fiber remodeling by fibroblasts. Acta Biomater. 2024; 177: 118–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dabaghi M, Carpio MB, Saraei N, et al.. A roadmap for developing and engineering in vitro pulmonary fibrosis models. Biophys Rev (Melville). 2023; 4(2): 021302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rashidi N, Harasymowicz NS, Savadipour A, et al.. PIEZO1-mediated mechanotransduction regulates collagen synthesis on nanostructured 2D and 3D models of fibrosis. Acta Biomater. 2025; 193: 242–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li H, Fitchett C, Kozdon K, et al.. Independent adipogenic and contractile properties of fibroblasts in Graves’ orbitopathy: an in vitro model for the evaluation of treatments. PLoS One. 2014; 9(4): e95586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang IH, Rose GE, Ezra DG, et al.. Macrophages promote a profibrotic phenotype in orbital fibroblasts through increased hyaluronic acid production and cell contractility. Sci Rep. 2019; 9(1): 9622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ichioka H, Ida Y, Watanabe M, et al.. Prostaglandin F2alpha and EP2 agonists, and a ROCK inhibitor modulate the formation of 3D organoids of Grave's orbitopathy related human orbital fibroblasts. Exp Eye Res. 2021; 205: 108489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ida Y, Ichioka H, Furuhashi M, et al.. Reactivities of a prostanoid EP2 agonist, omidenepag, are useful for distinguishing between 3D spheroids of human orbital fibroblasts without or with Graves’ orbitopathy. Cells. 2021; 10(11): 3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Umetsu A, Sato T, Watanabe M, et al.. Unexpected crosslinking effects of a human thyroid stimulating monoclonal autoantibody, M22, with IGF1 on adipogenesis in 3T3L-1 cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24(2): 1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hikage F, Suzuki M, Sato T, et al.. Effects of linsitinib on M22 and IGF:1-treated 3D spheroids of human orbital fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2025; 15: 384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bartley GB, Gorman CA. Diagnostic criteria for Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995; 119: 792–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun A, Ye H, Xu Z, et al.. Serelaxin alleviates fibrosis in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy via the notch pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24(9): 8356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012; 18: 1028–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chunduri V, Maddi S. Role of in vitro two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) cell culture systems for ADME-Tox screening in drug discovery and development: a comprehensive review. ADMET DMPK. 2023; 11: 1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang X, Huang Z, Gao W, et al.. Current advances in 3D dynamic cell culture systems. Gels. 2022; 8: 829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krysko DV, Demuynck R, Efimova I, et al.. In vitro veritas: from 2D cultures to organ-on-a-chip models to study immunogenic cell death in the tumor microenvironment. Cells. 2022; 11: 3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu Y, Zhang J, Deng W, et al.. Comparison of orbital fibroblasts from Graves’ ophthalmopathy and healthy control. Heliyon. 2024; 10(7): e28397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yu WK, Hwang WL, Wang YC, et al.. Curcumin suppresses TGF-beta1-induced myofibroblast differentiation and attenuates angiogenic activity of orbital fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22: 6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang X, Yang S, Ye H, et al.. Disulfiram exerts antiadipogenic, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic therapeutic effects in an in vitro model of Graves’ orbitopathy. Thyroid. 2022; 32: 294–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shevtsov M, Pitkin E, Combs SE, et al.. Biocompatibility analysis of the silver-coated microporous titanium implants manufactured with 3D-printing technology. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2024; 14: 1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lewis SM, Callaway MK, Dos Santos CO. Clinical applications of 3D normal and breast cancer organoids: a review of concepts and methods. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2022; 247: 2176–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu R, Meng X, Yu X, et al.. From 2D to 3D co-culture systems: a review of co-culture models to study the neural cells interaction. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23: 13116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu X, Su Q, Zhang X, et al.. Recent advances of organ-on-a-chip in cancer modeling research. Biosensors (Basel). 2022; 12: 1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lui KN, Ngan ES. Human pluripotent stem cell-based models for Hirschsprung disease: from 2-D cell to 3-D organoid model. Cells. 2022; 11: 3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chiu HI, Wu SB, Tsai CC. The role of fibrogenesis and extracellular matrix proteins in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25: 3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ueland HO, Neset MT, Methlie P, et al.. Molecular biomarkers in thyroid eye disease: a literature review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023; 39(6S): S19–S28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blaauboer ME, Smit TH, Hanemaaijer R, et al.. Cyclic mechanical stretch reduces myofibroblast differentiation of primary lung fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011; 404: 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amar S, Smith L, Fields GB. Matrix metalloproteinase collagenolysis in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017; 1864(11 Pt A): 1940–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen R, Baron R, Gori F. Sfrp4 and the biology of cortical bone. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2022; 20: 153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wallin R, Wajih N, Greenwood GT, et al.. Arterial calcification: a review of mechanisms, animal models, and the prospects for therapy. Med Res Rev. 2001; 21: 274–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ainger SA, Yong XL, Wong SS, et al.. DCT protects human melanocytic cells from UVR and ROS damage and increases cell viability. Exp Dermatol. 2014; 23: 916–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Winer H, Rodrigues GOL, Hixon JA, et al.. IL-7: comprehensive review. Cytokine. 2022; 160: 156049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Song B, Li X, Xu Q, et al.. Inhibition of BMP3 increases the inflammatory response of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Aging (Albany NY). 2020; 12: 12305–12323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yu L, Xu H, Zhang S, et al.. SDC1 promotes cisplatin resistance in hepatic carcinoma cells via PI3K-AKT pathway. Hum Cell. 2020; 33: 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rana I, Kataria S, Tan TL, et al.. Mindin (SPON2) is essential for cutaneous fibrogenesis in a mouse model of systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2023; 143: 699–710.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yu J, Perri M, Jones JW, et al.. Altered RBP1 gene expression impacts epithelial cell retinoic acid, proliferation, and microenvironment. Cells. 2022; 11: 792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Elbert M, Neumann F, Kiefer M, et al.. Hyper-N-glycosylated SEL1L3 as auto-antigenic B-cell receptor target of primary vitreoretinal lymphomas. Sci Rep. 2024; 14(1): 9571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Deniset JF, Belke D, Lee WY, et al.. Gata6(+) pericardial cavity macrophages relocate to the injured heart and prevent cardiac fibrosis. Immunity. 2019; 51: 131–140.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nakanishi Y, Matsugaki A, Kawahara K, et al.. Unique arrangement of bone matrix orthogonal to osteoblast alignment controlled by Tspan11-mediated focal adhesion assembly. Biomaterials. 2019; 209: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guan X, Liang J, Xiang Y, et al.. BARX1 repressed FOXF1 expression and activated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway to drive lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 261(Pt 2): 129717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nie H, Chen Y. SIM2, associated with clinicopathologic features, promotes the malignant biological behaviors of endometrial carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2025; 25: 666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boudjadi S, Chatterjee B, Sun W, et al.. The expression and function of PAX3 in development and disease. Gene. 2018; 666: 145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Qiu J, Li M, Su C, et al.. FOXS1 promotes tumor progression by upregulating CXCL8 in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2022; 12: 894043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zuppinger C. 3D cardiac cell culture: a critical review of current technologies and applications. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019; 6: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Caddeo A, Maurotti S, Kovooru L, et al.. 3D culture models to study pathophysiology of steatotic liver disease. Atherosclerosis. 2024; 393: 117544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.