Abstract

Purpose

Optic nerve invasion (ONI) is an important risk factor for extraocular metastasis in retinoblastoma. This study evaluates the impact of pre-enucleation chemotherapy, delayed enucleation, and adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in patients with varying degree of ONI on histopathology.

Methods

A retrospective review of consecutive enucleated eyes with any degree of ONI from 29 Chinese treatment centers 2012–2017. Children with other high-risk histopathological features, extraocular disease at diagnosis or bilateral enucleation were excluded.

Results

Among 2500 enucleated eyes, 386 eyes with isolated ONI (one eye per child) met the inclusion criteria: prelaminar (n = 204), intralaminar (n = 70), retrolaminar without tumor at transected optic nerve (n = 96), or retrolaminar with tumor at transected end (n = 16). Primary enucleation was performed in 59% of cases, whereas 41% underwent secondary enucleation after eye salvage therapies. Delayed enucleation beyond six months from diagnosis significantly increased the likelihood of tumor at optic nerve transection (21% vs. 2%; P < 0.001). The five-year cause-specific survival (CSS) was 96.7% overall: prelaminar (100%), intralaminar (98%), retrolaminar without transected end involvement (94%), or tumor at transected optic nerve (58%). Secondarily enucleated eyes with retrolaminar ONI without transected end involvement had lower CSS than those primarily enucleated (85.6% vs. 100%; P = 0.022). The five-year CSS was higher but not statistically significant, for eyes treated with or without adjuvant chemotherapy: intralaminar ONI (100% vs. 95.7%; P = 0.193), retrolaminar ONI without tumor at transected end (100% vs. 93.5; P = 0.413), and tumor at the transected end (80.0% vs. 45.0%; P = 0.192).

Conclusions

Timely enucleation reduces the risk of tumor involvement at optic nerve transection. Delay in enucleation by pre-enucleation chemotherapy may reduce the effectiveness of subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy.

Keywords: retinoblastoma, optic nerve invasion, chemotherapy, survival, mortality

Optic nerve invasion (ONI) in retinoblastoma is a well-established risk factor for systemic metastasis and mortality.1,2 ONI contributes to metastasis either through contiguous intracranial extension or seeding of tumor into the cerebrospinal fluid via leptomeningeal invasion.3,4 The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) pTNM classifies ONI into prelaminar, intralaminar, retrolaminar and tumor at the transected end of optic nerve.5 Greater extent of ONI increases the risk of extraocular spread. Despite this general trend, cases of brain metastasis in the absence of optic nerve involvement have been reported.6–8

Various forms of chemotherapy have emerged, showing potential of improved eye salvage. Consequently, there is a global trend towards primary chemotherapy rather than primary enucleation. However, chemotherapy may mask existing pathologic risk features in the eventually enucleated eye, disguising high-risk eyes as low risk.9,10 Undertreatment of children with masked high risk could account for children with brain metastasis in the apparent absence of high-risk ONI.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is administered after enucleation to treat potential metastasis from eyes with high-risk histopathologic features. Although prelaminar ONI is generally considered low-risk and retrolaminar ONI high-risk, there remains a lack of consensus regarding the risk associated with intralaminar ONI and potential benefit of adjuvant treatment for this group.11

In this retrospective study, we reviewed eyes with isolated ONI identified on pathology. The objective was to assess the impact of pre- and post-enucleation chemotherapy on metastatic mortality. A secondary aim was to determine whether pre-enucleation chemotherapy influences the extent of ONI.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee at Beijing Children's Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We reviewed records of all children managed by 29 Chinese treatment centers between January 2012 and December 2017. The last follow-up date was November 18, 2021. Inclusion criteria were any degree of ONI on histopathology of enucleated eyes. Excluded were children with extraocular disease (extrascleral or optic nerve invasion) evident on imaging at diagnosis, concurrent high-risk pathologic features (massive choroidal invasion, scleral invasion, or overt extraocular disease), or who underwent bilateral enucleation and children whose pathology microscopic sections were not reviewed by an ophthalmic pathologist.

At initial diagnosis, all children underwent routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (or computed tomography at centers where MRI is not available) to screen for extraocular disease. Repeat imaging was not routinely performed before enucleation. Clinical data collected included sex, laterality, clinical staging, treatment before and after enucleation, location of any metastasis, histopathology features, staging, and dates of diagnosis, last follow-up, and death.

Pathology Review

Enucleation and pathology slide preparation were performed either at affiliated academic centers or the patients’ local hospitals. All microscopic sections included in this study were transferred to, stained, and reviewed by subspecialized ophthalmic pathologists at three academic centers: Beijing Children's Hospital (N.J.), Beijing Tongren Hospital, or Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center. Optic nerve invasion was categorized as prelaminar, intralaminar, retrolaminar without involvement of the transected end, or retrolaminar with tumor present at the transected end. Additional invasion into anterior segment structures, choroid, sclera, and orbit was recorded. Throughout the article, “retrolaminar optic nerve invasion” refers to cases where the transected optic nerve end is free of tumor, unless cut end involvement is specifically indicated.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy Regimen

Decisions for adjuvant chemotherapy were made by the retinoblastoma specialist(s), medical oncologist, and children's parents. All children with retrolaminar ONI with or without transected end involvement were offered adjuvant treatment. Systemic adjuvant chemotherapy included intravenous carboplatin 560 mg/m2 on day 1, etoposide 150 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 or teniposide 230 mg/m2 on day 2, and vincristine 1.5 mg/m2 on day 2, on a cycle of 28 days. Adjuvant IAC with each cycle lasting 28 days, involved intra-arterial delivery of melphalan (0.4 mg/kg), topotecan (1 mg), and lobaplatin (10 mg, or 5 mg for children under six months) for cycle 1; melphalan (0.4 mg/kg) and topotecan (1 mg) for cycle 2; and cycle 3 repeated the regimen of cycle 1. The number of chemotherapy cycles varied because of a multitude of factors, such as treatment of the contralateral eye, parental choice (financial constraint, concern about side effects, or perception that the disease was cured), institutional protocols and medical contraindications to chemotherapy (i.e., severe thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, or adverse event from chemotherapy).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous and categorical variables were compared using Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 test, respectively. Kaplan-Meier was used to estimate cause-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival, with log-rank test to compare survival between groups. Cause-specific survival is defined as death secondary to retinoblastoma metastasis. Receiver operating characteristic analysis was used to define threshold based on time from diagnosis to enucleation. Sensitivity, 1 − specificity, and Youden's index were calculated for values of time from diagnosis to enucleation corresponding to CSS. The time with the highest Youden's index rounded to the nearest value was selected as threshold. All reported P values are two-sided, and P < 0.05 indicated significance. All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between 2012 and 2017, a total of 1908 patients (n = 2500 eyes) were diagnosed with intraocular retinoblastoma. During this period, 1041 eyes underwent enucleation, of which 188 were excluded because of the absence of microscopic slides to review and AJCC staging by an ophthalmic pathologist. ONI without other high-risk histopathology features was identified in 390 eyes. After the exclusion of four eyes with bilateral enucleation, 386 eyes met the inclusion criteria, with each enucleated eye corresponding to one child (raw data provided in Supplementary Table S1). Of these eyes, 360 (93%) were enucleated and had microscopic sections prepared at one of the three hospitals with an ophthalmic pathology service. The remaining 26 eyes were enucleated and had microscopic sections prepared at their local hospitals and subsequently reviewed and staged by one of the ophthalmic pathologists.

The degree of optic nerve invasion in 386 eligible eyes was categorized as prelaminar (n = 204), intralaminar (70), retrolaminar (n = 112), without tumor at transected end (n = 96), or tumor at transected end (n = 16). Of 96 eyes with retrolaminar invasion without tumor at transected end, 37 (39%) had less than 1 mm of retrolaminar ONI, whereas 59 (61%) had 1 mm or more. The clinical characteristics of the studied children are summarized in Table 1. More advanced optic nerve invasion on pathology correlated with higher IIRC12 or AJCC5 clinical staging. The median follow-up since diagnosis was 66.1 months (0–117.0 months).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of Studied Children and Eyes

| Characteristic | Prelaminar ONI (n = 204) | Intralaminar ONI (n = 70) | Retrolaminar ONI (n = 96) | Tumor at Transected End (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 128 (63%) | 37 (53%) | 50 (52%) | 10 (63%) |

| Female | 76 (37%) | 33 (47%) | 46 (48%) | 6 (38%) |

| Age of diagnosis (months) | ||||

| Median | 21 | 22 | 23 | 26 |

| Range | 1–84 | 3–89 | 2–111 | 3–80 |

| Laterality | ||||

| Unilateral | 169 (83%) | 60 (86%) | 82 (85%) | 15 (94%) |

| Bilateral | 35 (17%) | 10 (14%) | 14 (15%) | 1 (6%) |

| IIRC of Studied Eye | ||||

| D | 103 (50%) | 32 (46%) | 21 (22%) | 5 (31%) |

| E | 97 (48%) | 38 (54%) | 74 (77%) | 11 (69%) |

| Unknown | 4 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| AJCC cTNM of Studied Eye | ||||

| cT2b | 102 (50%) | 32 (46%) | 21 (22%) | 5 (31%) |

| cT3a | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| cT3b | 26 (13%) | 5 (7%) | 18 (19%) | 2 (13%) |

| cT3c | 43 (21%) | 12 (17%) | 28 (29%) | 2 (13%) |

| cT3d | 29 (14%) | 20 (29%) | 28 (29%) | 7 (43%) |

| Unknown | 4 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

IIRC, International Intraocular Retinoblastoma Classification.

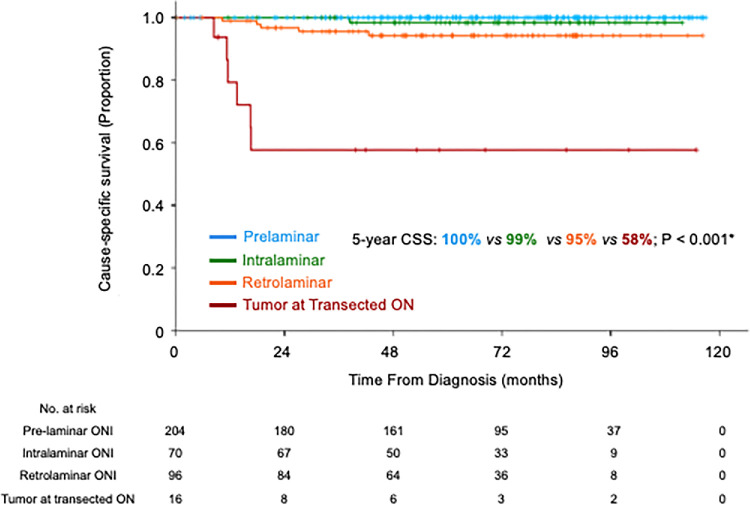

Pre-Enucleation Therapy

Enucleation was primary in 230 (59%) children and secondary in 156 (41%) children. Among 156 children who underwent secondary enucleation, pre-enucleation therapies included systemic chemotherapy (n = 145), intra-arterial chemotherapy (n = 31), tylectomy (n = 17),13 and intravitreal chemotherapy (n = 4). Of these 156, 125 (80%) received only systemic chemotherapy, 11 (7%) received only intra-arterial chemotherapy and 20 (13%) received both. Tylectomy was performed as a secondary eye-salvage therapy after inadequate response to chemotherapy. Pre-tylectomy treatments included systemic chemotherapy alone (n = 11), intra-arterial chemotherapy alone (n = 1), or both (n = 5). Of the 17 children who underwent tylectomy, 12 received adjuvant therapy: systemic chemotherapy alone (n = 4), intravitreal chemotherapy alone (n = 6), or both (n = 2). The median time from diagnosis to enucleation was 0.4 months (range, 0–49.6 months), shorter for those with primary enucleation versus secondary enucleation (median 0.1 vs. 3.2 months; P < 0.001). Children with tumor at the transected optic nerve had significantly longer median time from diagnosis to enucleation than those with prelaminar (7.5 vs. 0.7 months; P = 0.013), intralaminar (7.5 vs. 0.2 months; P = 0.002), or retrolaminar ONI (7.5 vs. 0.3 months; P = 0.002) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Boxplot showing time from diagnosis to enucleation (months) based on the degree of ONI.

The receiver operating characteristic analysis identified a time from diagnosis to enucleation >6 months as the threshold for predicting the likelihood of having tumor at transected optic nerve (Supplementary Table S2). Eyes with delay from diagnosis to enucleation >6 months were 15 times more likely to have tumor at transected end than eyes enucleated <6 months (21.2% vs. 1.7%; P < 0.001). Table 2 demonstrates that eyes with longer delay between diagnosis to enucleation (due to systemic or intra-arterial chemotherapy, or tylectomy), were more likely to have tumor at the transected end of optic nerve.

Table 2.

Treatment and Histopathology of Eyes With Varying Time From Diagnosis to Enucleation

| Time From Diagnosis to Enucleation | Median Pre-Enu IVC Cyclces (If Any) | Median Pre-Enu IAC Cyclces (If Any) | Number (%) With Tylectomy | Prelaminar ONI | Intralaminar ONI | Retrolaminar ONI | Tumor at Transected End |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3 months (n = 301) | 2 | 2 | 1 (0.3%) | 152 (50%) | 60 (20%) | 84 (28%) | 5 (2%) |

| 3 to 6 months (n = 38) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 28 (74%) | 4 (11%) | 5 (13%) | 1 (3%) |

| 6 to 9 months (n = 18) | 6 | 3 | 1 (6%) | 8 (44%) | 4 (22%) | 1 (6%) | 5 (28%) |

| >9 months (n = 29) | 4 | 2 | 15 (52%) | 16 (55%) | 2 (7%) | 6 (21%) | 5 (17%) |

IAC, intra-arterial chemotherapy; IVC, intravenous chemotherapy; Pre-enu, pre-enucleation.

Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy was given to 166 patients with ONI: prelaminar (n = 40 [20%], median 2 cycles), intralaminar (n = 29 [41%], median 3 cycles), retrolaminar (n = 85 [89%], median 6 cycles), tumor at transected optic nerve (n = 12 [75%], median 6 cycles). Adjuvant external beam radiation was given to eight children with ONI: retrolaminar (n = 2), tumor at transected optic nerve (n = 6). The two children with retrolaminar invasion without transected end involvement received radiotherapy because tumor cells were found in their cerebrospinal fluid.

Mortality

Fifteen children died: 12 died of retinoblastoma metastasis with extraocular disease involving the brain (n = 6), orbit (n = 2), cerebrospinal fluid (n = 1), lung (n = 1), left femoral neck (n = 1), or lumbar vertebra (n = 1); three non-metastatic deaths were due to pineoblastoma (n = 1), brain hemorrhage (n = 1), or acute myeloid leukemia14,15 (n = 1) (patient no. 377 who developed leukemia received three cycles of intra-arterial chemotherapy and six cycles of post-enucleation systemic chemotherapy). Clinical and treatment features of children who died of metastasis are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. Of the 16 children who died of tumor metastasis, three had bilateral disease, and none had an active tumor in the contralateral eye at the last follow-up; therefore these deaths were attributed to tumor relapse from the enucleated eye. The median time from diagnosis to metastatic death was 16.6 months (range 8.4–42.6).

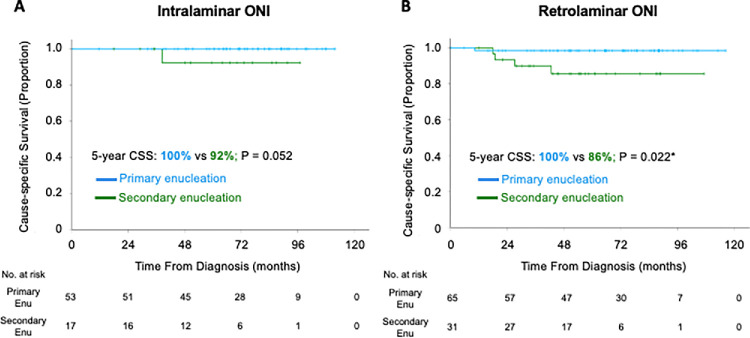

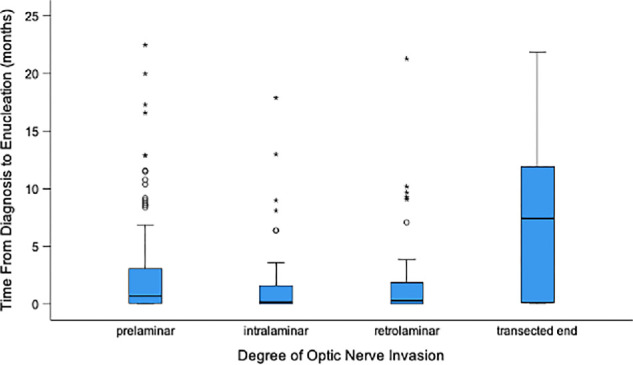

The five-year overall survival rate was 95.9% (95% confidence interval, 93.9%–97.9%) and the five-year CSS was 96.7% (95% confidence interval, 94.9%–98.5%). More advanced ONI was associated with a lower five-year CSS: prelaminar (100%), intralaminar (98.4%), retrolaminar (94.2%), and tumor at transected optic nerve (57.7%) (Fig. 2). Secondarily enucleated children with retrolaminar ONI had lower five-year CSS compared to primarily enucleated children with the same pathological feature (85.6% vs. 98.4%; P = 0.022) (Fig. 3). Children who were secondarily enucleated with intra-laminar ONI (92.3% vs. 100%; P = 0.052) and tumor at transected end (44.4% vs. 83.3%; P = 0.299) trended to worse survival than primarily enucleated children.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of CSS of children with various degree of ONI.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of CSS of children with primary and secondary enucleation. (A) Intralaminar ONI. (B) Retrolaminar optic nerve invasion without tumor at transected end. Enu, enucleation. *P < 0.05.

Children with prelaminar ONI (100% vs. 100%), intralaminar ONI (95.7% vs. 100%; P = 0.193) or retrolaminar ONI (93.5% vs. 100%; P = 0.413) had similar five-year CSS, regardless of whether they received adjuvant chemotherapy. The 16 children with tumor at optic nerve transection, showed a trend toward higher five-year CSS if they were treated with adjuvant chemoradiation versus no adjuvant treatment (80.0% vs. 45.0%; P = 0.192).

Discussion

ONI is arguably the most important pathological risk factor predicting survival outcomes of children affected by retinoblastoma. Our study of 386 enucleated eyes with isolated ONI is the largest reported to date. We show that delayed enucleation beyond six months, (intending globe salvage) was associated with a higher likelihood of tumor at the transected optic nerve. Children with equivalent extent of ONI exhibited lower survival after secondary enucleation than primary enucleation.

The presence of tumor at transected optic nerve indicates incomplete tumor removal and extraocular disease. Despite aggressive therapy, mortality remains high. However, our study and others suggest that these children benefit from adjuvant chemoradiation.10,16–21 In our cohort, the five-year survival rate exceeded 90% for prelaminar, intralaminar, and retrolaminar ONI without transected end involvement, but there was a sharp decline in survival to 58% when tumor was present at the transected end of the optic nerve. A separate chart review of children treated during the same study period revealed that nine out of 809 (1%) children with IIRC Group D/E disease who did not undergo enucleation developed metastasis leading to death, excluding those who abandoned treatment (five-year CSS 99%) (unpublished data).

Our study shows that tumor at the transected optic nerve end is significantly more likely when enucleation is delayed beyond six months from diagnosis. Delay may result from attempts at eye salvage with chemotherapy or surgery, hesitancy to proceed with enucleation, or late tumor recurrence. Our findings strongly support timely enucleation of eyes with low likelihood of successful salvage may prevent metastasis and morbidity of adjuvant radiotherapy.

Our study highlights that children with retrolaminar ONI exhibited significantly lower survival when they had been treated with pre-enucleation chemotherapy, than children who had primary enucleation. Similar trends (not statistically significant) were observed for children with intralaminar ONI and tumor at transected end. This may reflect chemoresistance, since tumors that failed primary chemotherapy are less likely to respond to adjuvant chemotherapy.22,23 Chemotherapy may also mask the initial extent of ONI, leading to underestimation of need for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Although retrolaminar ONI is universally recognized as a high-risk feature,11 there is no consensus on the role of adjuvant treatment. A survey by the European Retinoblastoma Group revealed that all participating centers recommended adjuvant chemotherapy for retrolaminar ONI, while no treatment was advocated for prelaminar or intralaminar ONI.20 However, Chantada et al.24 reported that 21 children with isolated retrolaminar ONI all survived without adjuvant chemotherapy. Chantada et al.24 proposed that children with retrolaminar ONI have a good prognosis without adjuvant chemotherapy and rescue therapy if there is systemic relapse.

In the present study, survival for intralaminar and retrolaminar ONI was 100% with adjuvant chemotherapy, not significantly different from those without adjuvant chemotherapy. The long-term adverse effects of radiotherapy, including subsequent malignant neoplasms, outweigh the potential benefit of avoiding adjuvant chemotherapy.25 Presently, we recommend adjuvant chemotherapy for eyes with retrolaminar ONI, particularly when pre-enucleation chemotherapy was given. In a randomized controlled clinical trial, Ye et al.26 showed that three cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy were non-inferior to six cycles, in terms of disease-free survival for children with high-risk histopathology.

Our study reported on pathology performed during routine clinical care in China without centralized pathology processing. Although all pathology slides were reviewed by an ophthalmic pathologist, variability in preparation at local centers possibly led to underrecognition of high-risk features. The Children's Oncology Group highlighted considerable discordance between central consensus pathology review and pathology reports by contributing institutions.27 Another limitation of our present study is CT imaging in centers without MRI access, which potentially falsely excludes extraocular disease at diagnosis.28 Additional limitations include retrospective design and nonuniform chemotherapy. The strength of this study is its large sample size in a real-world context, extended follow-up, strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, and focused evaluation of an isolated histopathologic feature.

Conclusions

Our study underscores the crucial role of timely enucleation in reducing the risk of tumor extending to optic nerve transection. Our study also points out potential influence of pre-enucleation chemotherapy at reducing effectiveness of subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy. These results suggest careful reassessment of mortality consequence of extended eye salvage therapy and delaying enucleation, especially for eyes with limited visual potential or a low likelihood of successful salvage. Our findings aim to support clinicians and caregivers in making informed decisions regarding the management of children with retinoblastoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xuan Zhang and Bin Li, ocular pathologists at Beijing Tongren Hospital and Peng Li, ocular pathologist at Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, for their expert review of the pathology at their respective centers.

Disclosure: Z.X. Feng, None; J. Zhao, None; D. D'Souza, None; N. Zhang, None; M. Jin, None; B. Gallie, None

References

- 1. Magramm I, Abramson DH, Ellsworth RM.. Optic nerve involvement in retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology . 1989; 96: 217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Baez K, Cater JR, De-Potter P.. Optic nerve invasion of retinoblastoma. Metastatic potential and clinical risk factors. Cancer . 1994; 73: 692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Munier FL. Classification and management of seeds in retinoblastoma. Ellsworth Lecture Ghent August 24th 2013. Ophthalmic Genet . 2014; 35: 193–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chevez-Barrios P, Hurwitz MY, Louie K, et al.. Metastatic and nonmetastatic models of retinoblastoma. Am J Pathol . 2000; 157: 1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mallipatna A, Gallie BL, Chévez-Barrios P, et al.. Retinoblastoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual . 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2017: 819–831. [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacKay CJ, Abramson DH, Ellsworth RM.. Metastatic patterns of retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol . 1984; 102: 391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu JE, Francis JH, Dunkel IJ, et al.. Metastases and death rates after primary enucleation of unilateral retinoblastoma in the USA 2007-2017. Br J Ophthalmol . 2019; 103: 1272–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feng ZX, Zhao J, Zhang N, Jin M, Gallie B. Adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival for children with massive choroidal invasion of retinoblastoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2023; 64(11): 27–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao J, Dimaras H, Massey C, et al.. Pre-enucleation chemotherapy for eyes severely affected by retinoblastoma masks risk of tumor extension and increases death from metastasis. J Clin Oncol . 2011; 29: 845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhao J, Feng ZX, Wei M, et al.. Impact of systemic chemotherapy and delayed enucleation on survival of children with advanced intraocular retinoblastoma. Ophthalmol Retina . 2020; 4: 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaliki S, Shields CL, Cassoux N, et al.. Defining high-risk retinoblastoma: a multicenter global survey. JAMA Ophthalmol . 2022; 140: 30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murphree AL. Intraocular retinoblastoma: the case for a new group classification. Ophthalmol Clin North Am . 2005; 18: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao J, Li Q, Feng ZX, et al.. Tylectomy safety in salvage of eyes with retinoblastoma. Cancers . 2021; 13: 5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leahey AM, Shields CL.. Chronic myeloid leukemia versus acute myeloid leukemia in patients with retinoblastoma. Oman J Ophthalmol . 2021; 14: 134–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weintraub M, Revel-Vilk S, Charit M, Aker M, Pe'er J.. Secondary acute myeloid leukemia after etoposide therapy for retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol . 2007; 29: 646–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaliki S, Tahiliani P, Mishra DK, Srinivasan V, Ali MH, Reddy VA.. Optic nerve infiltration by retinoblastoma: predictive clinical features and outcome. Retina . 2016; 36: 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaliki S, Srinivasan V, Gupta A, Mishra DK, Naik MN.. Clinical features predictive of high-risk retinoblastoma in 403 Asian Indian patients: a case-control study. Ophthalmology . 2015; 122: 1165–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Honavar SG, Singh AD, Shields CL, et al.. Postenucleation adjuvant therapy in high-risk retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol . 2002; 120: 923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh AD, Shields CL, Shields JA.. Prognostic factors in retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus . 2000; 37: 134–141; quiz 168–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dittner-Moormann S, Reschke M, Abbink FCH, et al.. Adjuvant therapy of histopathological risk factors of retinoblastoma in Europe: A survey by the European Retinoblastoma Group (EURbG). Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2021; 68(6): e28963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chantada GL, Guitter MR, Fandino AC, et al.. Treatment results in patients with retinoblastoma and invasion to the cut end of the optic nerve. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2009; 52: 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cara S, Tannock IF.. Retreatment of patients with the same chemotherapy: implications for clinical mechanisms of drug resistance. Ann Oncol . 2001; 12: 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu C, Chen J, Liu Y.. Rechallenge therapy versus tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) for advanced metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective study. Sci Rep . 2025; 15(1): 4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24. Chantada GL, Dunkel IJ, de Davila MT, Abramson DH.. Retinoblastoma patients with high risk ocular pathological features: who needs adjuvant therapy? Br J Ophthalmol . 2004; 88: 1069–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong FL, Boice JD Jr., Abramson DH, et al.. Cancer incidence after retinoblastoma. Radiation dose and sarcoma risk. JAMA . 1997; 278: 1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ye H, Xue K, Zhang P, et al.. Three vs 6 cycles of chemotherapy for high-risk retinoblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2024; 332: 1634–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chevez-Barrios P, Eagle RC Jr., Krailo M, et al.. Study of unilateral retinoblastoma with and without histopathologic high-risk features and the role of adjuvant chemotherapy: a children's oncology group study. J Clin Oncol . 2019; 37: 2883–2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brisse HJ, Guesmi M, Aerts I, et al.. Relevance of CT and MRI in retinoblastoma for the diagnosis of postlaminar invasion with normal-size optic nerve: a retrospective study of 150 patients with histological comparison. Pediatr Radiol . 2007; 37: 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.