Abstract

Background

Pathological complete response (pCR) to neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NAST) is an established prognostic marker in breast cancer (BC). Multimodal deep learning (DL), integrating diverse data sources (radiology, pathology, omics, clinical), holds promise for improving pCR prediction accuracy. This systematic review synthesizes evidence on multimodal DL for pCR prediction and compares its performance against unimodal DL.

Methods

Following PRISMA, we searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science (January 2015–April 2025) for studies applying DL to predict pCR in BC patients receiving NAST, using data from radiology, digital pathology (DP), multi-omics, and/or clinical records, and reporting AUC. Data on study design, DL architectures, and performance (AUC) were extracted. A narrative synthesis was conducted due to heterogeneity.

Results

Fifty-one studies, mostly retrospective (90.2%, median cohort 281), were included. Magnetic resonance imaging and DP were common primary modalities. Multimodal approaches were used in 52.9% of studies, often combining imaging with clinical data. Convolutional neural networks were the dominant architecture (88.2%). Longitudinal imaging improved prediction over baseline-only (median AUC 0.91 vs. 0.82). Overall, the median AUC across studies was 0.88, with 35.3% achieving AUC ≥ 0.90. Multimodal models showed a modest but consistent improvement over unimodal approaches (median AUC 0.88 vs. 0.83). Omics and clinical text were rarely primary DL inputs.

Conclusion

DL models demonstrate promising accuracy for pCR prediction, especially when integrating multiple modalities and longitudinal imaging. However, significant methodological heterogeneity, reliance on retrospective data, and limited external validation hinder clinical translation. Future research should prioritize prospective validation, integration underutilized data (multi-omics, clinical), and explainable AI to advance DL predictors to the clinical setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13062-025-00661-8.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Neoadjuvant treatment, Deep learning, Multimodal prediction

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a heterogeneous disease where neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NAST) may improve surgical and survival outcomes [1]. The achievement of pathological complete response (pCR), defined as the absence of invasive tumor cells in the breast and axillary lymph nodes (ypT0/is, ypN0) [2], is a key prognostic indicator. Several studies, including meta-analyses, have demonstrated that patients achieving pCR often experience significantly better disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), particularly in aggressive subtypes such as triple-negative (TNBC) and HER2-positive BC (HER2+ BC) [3, 4]. Given its strong association with long-term outcomes, pCR prediction has become clinically important for tailoring personalized treatment strategies [5]. Early prediction models primarily incorporated clinical variables (tumor size, stage, hormone receptor status, HER2 status) into classical statistical methods like logistic regression-based nomograms [6, 7]. With the emergence of radiomics, handcrafted imaging features extracted from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or mammography (MG) were combined with classical machine learning (CML) algorithms (e.g., support vector machine, random forest) to enhance pCR prediction [8, 9]. Parallel to radiomics, quantitative pathomics in digital pathology (DP) imaging and molecular multi-omics expanded the opportunities for predictive modeling, though these often relied on manual or semi-automatic feature engineering [10, 11].

Deep learning (DL)—defined as a type of machine learning (ML) based on artificial neural networks in which multiple layers of processing are used to extract progressively higher level features from data—is an important development in the context of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies [12]. DL architectures, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated significant performance gains in image-related tasks across various medical fields [13]. Their capacity to automatically extract hierarchical features from imaging data has facilitated investigations into predicting pCR in BC without the need for handcrafted feature engineering [14]. Other DL approaches, including autoencoders (AEs), have demonstrated significant potential for extracting, processing, and integrating deep features from high-dimensional molecular tumor profiling data, such as genomic sequencing, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics [15, 16]. Such frameworks have demonstrated effectiveness in classification tasks for cancer management [17]. Advanced DL models, including large language models (LLMs) or smaller domain-specific language models (e.g. BioBERT), have similarly demonstrated effectiveness in extracting latent representations from biomedical text data [18]. The transition towards multimodal DL, which combines imaging (radiological and histological), molecular profiling, and clinical data, offers a comprehensive approach to capturing the complexity of tumor biology and patient-specific factors. Multimodal DL models integrating clinical data with pretreatment imaging have been developed to predict pCR to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in BC, demonstrating improved predictive performance [19]. Cross-modal approaches that combine DP imaging with longitudinal radiological imaging data acquired during treatment have also shown significant potential for early and accurate prediction of pCR [20]. Recent literature highlights the potential of multimodal DL approaches in precision oncology, emphasizing the need for further research to fully harness their clinical potential [21].

Despite the expanding body of literature, a comprehensive synthesis of studies focusing on DL-driven, multimodal pCR predictors in BC remains limited. Thus, this systematic review aims to address this knowledge gap by systematically evaluating current evidence on multimodal DL approaches for predicting pCR in BC patients treated with NAST. We also examine and compare single versus multimodal approaches and summarize methodological aspects, emphasizing strengths, limitations, and opportunities for advancement, particularly through the incorporation of advanced architectures such as transformers and LLMs, prospective multi-center designs, and underexplored data modalities including molecular multi-omics and free-text clinical notes.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Below, we detail the search strategy, eligibility criteria, study selection, data extraction, and data synthesis methods.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science databases on January 17, 2025, and updated on April 15, 2025. Articles published from January 1, 2015 onwards were considered, restricted to English-language studies involving Humans. The search aimed to identify investigations evaluating AI methodologies applied to neoadjuvant treatment in BC, using a structured combination of controlled vocabulary and free-text keywords categorized into three thematic areas: 1) the BC domain, including terms such as "breast cancer", "breast carcinoma" and "breast neoplasm"; 2) the NAST domain, including keywords encompassed "neoadjuvant therapy", "neoadjuvant chemotherapy", "neoadjuvant immunotherapy" and "preoperative therapy"; and 3) the the AI domain covering terms including “artificial intelligence”, "machine learning," "deep learning," "neural networks," "transformers," "large language models", “autoencoders”, and associated acronyms (AI, ML, LLM, CNN, GAN, GPT, BERT), as well as advanced techniques like "federated learning", "transfer learning", "ensemble learning", "self-supervised learnin"g, and "multimodal AI". These three domains were combined using the Boolean operator "AND," and the strategy was customized according to the indexing terms and syntax of each database. The complete search strategy and exact syntax used for each database are detailed in the supplementary methods (Supplementary File 1).

Eligibility criteria

Studies selected included invasive BC patients across various subtypes treated with NAST, involving chemotherapy alone or combined with targeted therapies and immunotherapy. The primary focus was on studies employing DL-based AI approaches to predict NAST effectiveness, specifically pCR. DL architectures were required for either feature extraction (including automatic tumor detection) or classifier/predictor construction. Eligible studies incorporated primary data for the prediction from at least one key domain: (i) radiological imaging [MRI, MG, ultrasound imaging (US), computed tomography (CT), or positron emission tomography (PET)]; (ii) DP (histopathological imaging); (iii) multi-omic tumor profiling (including genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics); or (iv) clinical information from electronic medical records (EMRs) or textual clinical reports (radiology and pathology reports, or routine molecular biomarkers). Studies had to provide quantitative performance metrics (at least the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve—AUC) specifically on pCR. Included were observational studies (retrospective and prospective), clinical trials featuring AI sub-studies, and methodological articles validated in public BC cohorts. Excluded were editorials, letters, conference abstracts, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, studies with insufficient sample size (< 30 patients), individual case reports, those lacking primary outcome metrics, metrics on response assessments which were not pCR rate, preclinical model studies and studies that applied AI methods which were not identifiable as DL (i.e. neural network with multiple hidden layers).

Study selection and data extraction

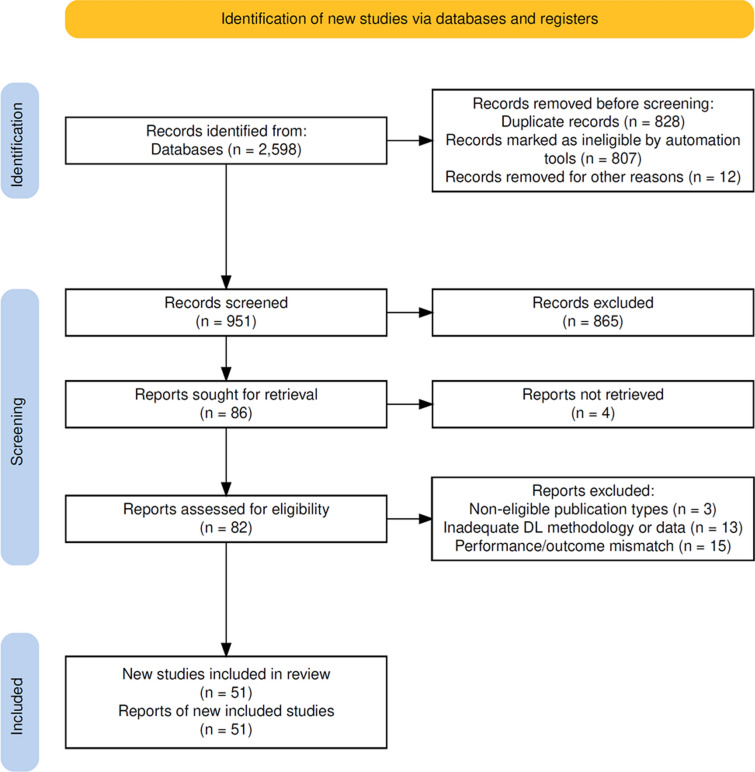

All identified studies were managed using Zotero. Following deduplication, six authors (EK, LF, TA, LP, LG, and RK) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance, ensuring each record was evaluated by at least two authors. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions among these authors, and any persistent disagreements were adjudicated by consultation with senior authors (GB, GC, and PV). Subsequently, selected articles underwent independent full-text review by pairs among the same six authors (EK, LF, TA, LP, LG, and RK), strictly applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The entire selection and review process, including the number of studies excluded at each stage with detailed reasons, is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). Data extraction from the final studies was also independently performed by these six authors (EK, LF, TA, LP, LG, and RK) using a structured Microsoft Excel form. Extracted information included study characteristics (authors, publication year, study design, cohort size, data source type), patient demographics, tumor attributes, data modalities utilized (radiological imaging, digital histopathology, multi-omic profiling, clinical data), AI methodologies, and predictive performance metrics.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). DL, deep learning

Data synthesis and analysis

Given the substantial methodological variability observed across studies, encompassing differences in AI approaches such as diverse DL architectures, the distinct types of input data, different multimodal integration strategies, as well as variability in reported performance metrics and outcomes, a rigorous quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Consequently, we conducted a comprehensive narrative synthesis. Descriptive summary statistics for all 51 studies, grouped by subtype, study design, primary and secondary modalities, number of imaging time points, and AI technique are provided in supplementary data (Supplementary File 2).

Results

Overview of included studies

A total of 51 studies were selected for final synthesis in this systematic review, all employing DL models to predict pCR in BC patients undergoing NAST. Figure 1 comprehensively illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram, detailing the initial identification of 2,598 records, removal of duplicates (n = 828), exclusion of clearly ineligible records (n = 807), and exclusion based on title and abstract screening (n = 865). Subsequently, 82 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 31 were excluded for specific reasons: non-eligible publication types (n = 3), inadequate/absent DL methodology or data (n = 13), or mismatch in terms of NAST outcome and/or performance metrics (n = 15), ultimately resulting in 51 studies included in this review.

The majority of these studies adopted retrospective designs [n = 46 (90.2%)], with 28 conducted at a single center and the remaining 23 utilizing multi-center cohorts (sometimes relying on public datasets). Sample sizes varied widely, ranging from 31 to 3,352 patients [22, 23], with a median cohort size of 281 patients. Most studies (41/51) enrolled heterogeneous populations comprising multiple BC subtypes [TNBC, HER2+ BC, and hormone receptor-negative/HER2-negative breast cancer (HR+ /HER2- BC)]. Among the remaining studies, five specifically focused on TNBC patients [24–28], two exclusively investigated HER2+ BC [29, 30], one included both HER2+ BC and TNBC patients [31], one targeted patients with HER2-low BC [32], and one examined HER2- BC [33]. Thirty-nine studies (76.5%) validated/tested the final model on an independent patient cohort that was not used during the training phase. This independent cohort could be external (in the case of multi-center studies), internal (a held-out subgroup in single center studies), or a public dataset.

Most of the investigations [n = 37 (72.5%)] leveraged radiological imaging as the primary data modality to predict pCR through DL. MRI was predominant, utilized in 20 studies, followed by US, which served as the main data source in 12 studies. Several other radiological and functional imaging techniques were less commonly investigated, including CT (2 studies) [34, 35], MG (2 studies) [36, 37], and PET (1 study) [22]. In the domain of histopathology, DP was the primary modality in 13 studies, highlighting its relevance in this context. In contrast, only a single study primarily utilized RNA sequencing data [32] for DL analysis (in the domain of molecular -omics profiling), while studies applying DL primarily on textual clinical data to predict pCR were notably absent. Figure 2 provides a Sankey diagram of how each study’s primary modality is combined with secondary and even tertiary inputs. In particular, 27 out of the 51 studies (52.9%) employed multimodal approaches, integrating two or more data types to enhance predictive accuracy. In most cases (24/27), multimodal predictive models combined the primary modality with just one additional data type; clinical data was the most frequently integrated secondary modality, being utilized in 23 studies, while CT was combined with DP in only one study [38]. Among bimodal combinations, the integration of MRI with clinical data was the most common, observed in 11 studies. Conversely, DP frequently appeared as a single modality, being employed alone in 8 of the 13 studies using DP as the primary data source. A smaller subset of three studies explored multimodal integration involving three data modalities. Specifically, two studies utilized US as the primary modality, supplementing it with DP and clinical data [20, 39], whereas the third study employed MRI as the primary modality combined with MG and clinical data [23]. Notably, none of the studies integrated all four data domains (radiological, histopathological, molecular, and clinical) simultaneously to predict pCR, thereby missing potential synergistic gains that multi-modal fusion may offer.

Fig. 2.

Sankey diagram showing the distribution of primary, secondary and tertiary modalities among the 51 studies included in this review. The left column indicates each study’s primary data modality, the middle column its secondary data modality, and the right column its tertiary data modality. Flow widths are proportional to the number of studies integrating a data modality level with the next. MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging; DP, Digital pathology; US, Ultrasonography (Ultrasound); CT, Computed tomography; MG, Mammography; PET, Positron emission tomography; RNA, RNA Sequencing data; Clinical: Clinical data; None, No additional data modality. Numbers in parentheses denote study counts (n) for each modality at the given level

With respect to DL strategies, the majority of the studies [n = 45 (88.2%)] utilized CNNs as the core architecture for feature extraction from imaging data. In nine studies, CNNs were combined with advanced DL components, such as attention mechanisms and/or transformer modules (particularly within multimodal frameworks) [36, 37, 40–44], or long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [45, 46] when longitudinal imaging data were incorporated. Five studies employed exclusively transformer architecture (without CNNs) for feature extraction [20, 30, 47–49], with different adaptations of attention mechanisms. Additionally, in five studies, CNNs were supplemented with domain-specific methods, such as handcrafted radiomics or quantitative ultrasound-derived or classical pathomic features [38, 50–53]. Regarding the multimodal integration and/or the classifier, most studies (n = 33) employed end-to-end DL strategies, retaining CNNs or other DL methods throughout the predictive pipeline. Conversely, 18 studies adopted hybrid approaches, limiting DL to the feature extraction step and relying on CML methods, including support vector machines or regularized regression models (e.g., LASSO logistic regression), for integration and final predictions. Longitudinal imaging data acquisition emerged as a relevant factor for pCR prediction. Specifically, 22 studies leveraged imaging data (predominantly MRI and US) collected at multiple time points (ranging from two to five acquisitions at early, mid-, and post-NAST phases) to build predictive models. In contrast, the majority of studies (n = 29) exclusively utilized baseline pre-NAST imaging data.

Reported pCR rates (considering all patients involved in the respective works) varied substantially across studies, ranging from 16.7% [39] to 59.1% [30], with a mean pCR rate of 32.8%. However, this proportion increased to 42.8% when selecting for studies including only patients with TNBC and/or HER2+ BC. All studies reported performance metrics evaluating the ability of the final predictive models to discriminate between pCR and non-pCR cases, most frequently using AUC. Across the reviewed studies, AUC values ranged from 0.70 to 1.00, with a median of 0.88 and a mean of 0.85. Notably, 18 out of the 51 studies (35.3%) reported AUC values equal to or greater than 0.90, highlighting their high discriminative capacity in predicting pCR. Median and mean AUC values improved from 0.83 in the 23 studies using a single data modality to 0.88 and 0.86, respectively, in the 28 studies integrating at least one additional data type. Among the modalities frequently used as standalone data sources, median and mean AUC values were 0.79 and 0.80 for DP (8 studies), 0.84 and 0.86 for MRI (8 studies), and 0.92 and 0.89 for US (4 studies), respectively. In studies incorporating clinical data alongside these primary imaging modalities, DP-based models showed modest improvements of 0.02–0.03 in median and mean AUC, MRI-based models demonstrated a more substantial increase of 0.04 in the median AUC, whereas US-based models exhibited minimal changes upon integrating clinical data. Additionally, acquiring imaging data at one more supplementary time point (early-, mid-, or post-NAST) beyond the baseline (pre-NAST) significantly increased median and mean AUC values from 0.82 to 0.91. However, incorporating more than one additional imaging acquisitions did not further enhance predictive performance. Key summary statistics of the selected 51 studies, including cohort sizes, pCR rates, and AUC distributions across all study categories can be found in supplementary data (Supplementary File 2).

MRI-based deep learning approaches for predicting pCR

Focusing specifically on the 20 studies identified in this review that utilized MRI as the primary data modality for DL-based prediction (Table 1), one study employed a retro‐prospective [27] design while all others were retrospective. Ten were multicenter studies, and nine among these leveraged the publicly available I-SPY1 [14, 44, 54–57] or I-SPY2 [23, 45, 46] cohorts as the primary study population or as additional external validation sets. The remaining ten studies were single-center, with one incorporating I-SPY2 [49] data for external validation. The majority of investigations encompassed nearly all BC subtypes, whereas one study exclusively focused on TNBC [27], and another focused on both TNBC and HER2+ BC [31]. Nearly all of the studies employed T1-based dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI. Eight studies employed only MRI for prediction, seven of them using end-to-end DL. Three of these studies [42, 55, 58] utilized only pre-NAST MRI, achieving an AUC range of 0.72–0.85 for pCR prediction, while the remaining five studies [27, 49, 51, 59, 60] incorporated MRI scans from the early-to-mid treatment phase, reporting an improved AUC range of 0.81–0.97. Eleven studies incorporated clinical variables alongside MRI data, utilizing demographic factors (age), tumor biological characteristics (ER, PR, HER2 status, Ki67), tumor staging (TNM), histopathological grading, menopausal status, and type of NAST regimen as predictive features, achieving AUC values ranging from 0.70 to 0.93. Across these MRI‐based investigations three main patterns of AUC improvement were confirmed also by intra-study comparisons. First, transitioning from radiomics to DL tends to improve performance, although head-to-head comparisons were limited [41, 61]. Second, combining MRI features with clinical data yields a performance gain over unimodal imaging approaches [14, 19, 31, 41, 44–46, 54, 56, 57, 61]. Finally, leveraging multiple time points (pre‐, early‐, mid- or post‐treatment) further raises predictive accuracy [14, 41, 45, 46, 48, 56].

Table 1.

Summary of studies using breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as the primary input for pathologic complete response (pCR) prediction models

| Author, year | Citation Nr | Study design | BC subtype | Data modalities | Longitudinal imaging | AI techniques | Nr of Pts | Held-out cohort | Overall pCR Rate (%) | Best validation AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al., 2024 | 31 | Retrospective Single center | HER2+ BC and TNBC | MRI and Clinical | No | CNN end-to-end | 852 | Yes | 36.4 | 0.70 |

| Liu et al., 2020 | 55 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI only | No | CNN end-to-end | 131 | No | 30.5 | 0.72 |

| Massafra et al., 2022 | 57 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | No | CNN followed by CML | 225 | Yes | 29.3 | 0.80 |

| Comes et al., 2024 | 49 | Retrospective Single center (P) | Mixed | MRI only | Yes | TRA end-to-end | 106 | Yes | 36.8 | 0.81 |

| Comes et al., 2024 | 58 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | MRI only | No | CNN end-to-end | 120 | No | 34.2 | 0.82 |

| Dammu et al., 2023 | 14 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 155 | No | 27.1 | 0.83 |

| Jing et al., 2024 | 45 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 624 | No | 34.1 | 0.83 |

| Peng et al., 2022 | 61 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | No | CNN end-to-end | 356 | No | 23.3 | 0.83 |

| Zhou et al., 2023 | 27 | Retro-prospective Single center | TNBC | MRI only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 210 | Yes | 48.1 | 0.83 |

| Hao et al., 2023 | 42 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | MRI only | No | CNN end-to-end | 442 | Yes | 21.5 | 0.85 |

| Gao et al., 2024 | 23 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI, MG and Clinical | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 3352 | Yes | 23.5 | 0.88 |

| Verma et al., 2023 | 54 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 121 | Yes | 30.6 | 0.88 |

| Joo et al., 2021 | 19 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | No | CNN end-to-end | 536 | Yes | 24.8 | 0.89 |

| Comes et al., 2021 | 56 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | Yes | CNN followed by CML | 134 | Yes | 27.6 | 0.90 |

| Wang et al., 2025 | 44 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | No | CNN end-to-end | 281 | Yes | 41.3 | 0.90 |

| El Adoui et al., 2020 | 59 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | MRI only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 56 | Yes | 35.7 | 0.91 |

| Huang et al., 2023 | 51 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | MRI only | Yes | CNN followed by CML | 1262 | Yes | 34.9 | 0.93 |

| Li et al., 2023 | 41 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | Yes | CNN followed by CML | 95 | Yes | 25.3 | 0.93 |

| Liu et al., 2025 | 46 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | MRI and Clinical | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 385 | Yes | 33.8 | 0.93 |

| Qu et al., 2020 | 60 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | MRI only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 302 | Yes | 43.7 | 0.97 |

BC, Breast cancer; HER2+ BC, HER2-positive breast cancer; TNBC, Triple negative breast cancer; MG, Mammography; Clinical, Clinical data; AI, Artificial intelligence; CNN, Convolutional neural network; TRA, Transformer architecture; CML, Classical machine learning; Nr of Pts, Number of patients; (P), a Public dataset was involved; AUC, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve

With regards to neural network architectures, several studies employed custom-designed CNN, typically using end-to-end DL strategies for prediction, achieving AUC values ranging from 0.72 to 0.97 [14, 27, 44, 54, 55, 58–60]. Other investigations adopted pre-designed CNN architectures such as AlexNet [56, 57], ResNet [19, 23, 31, 42, 45, 51, 61], VGG [46], or hybrid models [41], reporting AUC values between 0.70 and 0.93. Among these, some studies trained these architectures de novo on their datasets, while others utilized pretrained CNNs leveraging transfer learning from large external datasets. Although pretrained CNN models were predominantly applied within end-to-end DL frameworks, some studies used CML methods to ensemble or integrate features extracted from one or more data modalities. Additionally, integration of transformer-based attention mechanisms or LSTM modules into CNN architectures was explored in several studies, and notably, one study exclusively implemented a Vision Transformer architecture [49].

Predictive value of deep learning models using ultrasound data

Twelve studies employed US as the primary data modality for DL-based prediction of pCR (Table 2). Among these, six studies were single-center, while eight utilized multicentric datasets. Most studies (n = 10) were retrospective, with two single-center studies designed prospectively [43, 62]. Investigated cohorts predominantly comprised mixed BC subtypes, except for one study specifically targeting HER2+ BC [29]. All included studies utilized two-dimensional (2D) US, primarily grayscale B-mode. Some investigations incorporated multiparametric US approaches, including strain elastography and various plane acquisitions (longitudinal, transverse, and largest cross-sectional planes). Four studies utilized exclusively US data for pCR prediction [29, 43, 47, 63], employing imaging acquired at pre-, early-, and/or mid-NAST, reporting AUC values ranging from 0.76 to 0.96. Six studies integrated clinical data with US imaging to form bimodal prediction models. Among these, half were limited to pre-NAST imaging acquisitions [52, 62, 64] and half integrated post-NAST imaging [48, 50, 53], with respective AUC ranges of 0.83–0.91 and 0.89–0.84. Two additional studies adopted a trimodal design, integrating US, DP, and clinical data, achieving AUC of 0.79 when only pre-NAST US was used [39] and AUC of 0.88 when early-NAST US was integrated [20]. Notably, eight studies out of 12 utilized longitudinal US assessments, combining pre-NAST imaging with subsequent early-, mid-, or post-NAST acquisitions.

Table 2.

Summary of studies using breast ultrasound (US) imaging as the primary input for pathologic complete response (pCR) prediction models

| Author, year | Citation nr | Study design | BC subtype | Data modalities | Longitudinal imaging | AI techniques | Nr of Pts | Held-out cohort | Overall pCR Rate (%) | Best validation AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gu et al., 2023 | 48 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | US and Clinical | Yes | TRA end-to-end | 484 | Yes | 34.3 | 0.90 |

| Gu et al., 2024 | 62 | Prospective Single center | Mixed | US and Clinical | No | CNN end-to-end | 170 | Yes | 37.1 | 0.88 |

| Guo et al., 2024 | 20 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | US, DP and Clinical | Yes | TRA end-to-end | 596 | Yes | 26.0 | 0.88 |

| Jiang et al., 2021 | 50 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | US and Clinical | Yes | CNN followed by CML | 592 | Yes | 31.8 | 0.94 |

| Jiang et al., 2024 | 39 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | US, DP and Clinical | No | CNN followed by CML | 311 | Yes | 16.7 | 0.79 |

| Liu et al., 2022 | 29 | Retrospective Multicenter | HER2+ BC | US only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 393 | Yes | 29.0 | 0.96 |

| Liu et al., 2025 | 53 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | US and Clinical | Yes | CNN followed by CML | 243 | Yes | 28.4 | 0.89 |

| Tong et al., 2023 | 47 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | US only | Yes | TRA end-to-end | 484 | Yes | 34.3 | 0.90 |

| Wang et al., 2024 | 52 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | US and Clinical | No | CNN followed by CML | 155 | Yes | 25.2 | 0.91 |

| Xie et al., 2022 | 63 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | US only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 114 | No | 34.2 | 0.94 |

| You et al., 2024 | 64 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | US and Clinical | No | CNN end-to-end | 1409 | Yes | 37.6 | 0.83 |

| Zhang et al., 2024 | 43 | Prospective Single center | Mixed | US only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 57 | Yes | 50.9 | 0.76 |

BC, Breast cancer; HER2+ BC, HER2-positive Breast Cancer; DP, Digital Pathology; Clinical, Clinical data; AI, Artificial intelligence; CNN, Convolutional neural network; TRA, Transformer architecture; CML, Classical machine learning; Nr of Pts, Number of patients; (P), a Public dataset was involved; AUC, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve

Regarding feature extraction methodologies, all 12 studies leveraged DL techniques to various extent; however, three also incorporated quantitative radiomic parameters [50, 52, 53]. DL architectures varied across studies: six employed customized de novo CNNs [29, 43, 63] or transformer-based models [20, 47, 48] in end-to-end DL pipelines, consistently utilizing pre-NAST imaging alongside at least one subsequent US acquisition, with reported AUCs ranging from 0.76 to 96. Five studies utilized pre-trained models (DenseNet [50, 62], ResNet [39], DenseNet-ResNet combination [53], VGG [52]), integrating features via classical ML methods for final predictions; of these, three studies relied exclusively on pre-NAST imaging, reporting AUCs from 0.79 to 81, while three studies included longitudinal imaging with AUC ranging from 0.89 to 0.84. One study implemented a hybrid approach, combining pre-trained and custom-built DL model components, yielding an AUC of 0.83 [64].

Studies based on other radiological and functional imaging

Five studies utilizing imaging modalities beyond MR and US were identified, all including mixed BC subtypes (Table 3). Two single-center studies from the same research group specifically utilized MG alone for predicting pathological complete response (pCR). The first study, with a retro-prospective design, applied a pretrained transformer for tumor detection and a ResNet model for feature extraction and classification on pre-NAST 2D digital mammograms, achieving an AUC of 0.71 [37]. The subsequent prospective study leveraged digital breast tomosynthesis (3D) images acquired at three distinct time points (pre-NAST, after two NAST cycles, and post-NAST) [36]. Using a pretrained 3D ResNet coupled with an attention module, longitudinal imaging significantly enhanced predictive performance, resulting in a final AUC of 0.83.

Table 3.

Summary of studies using computed tomography (CT), mammography (MG) or positron emission tomography (PET) imaging as the primary input for pathologic complete response (pCR) prediction models

| Author, year | Citation nr | Study design | BC subtype | Data modalities | Longitudinal imaging | AI techniques | Nr of Pts | Held-out cohort | Overall pCR Rate (%) | Best validation AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulut et al., 2023 | 22 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | PET only | No | CNN end-to-end | 31 | No | 29.0 | 0.90 |

| Förnvik et al., 2024 | 36 | Prospective Single center | Mixed | MG only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 149 | Yes | 22.1 | 0.83 |

| Rezaeijo et al., 2021 | 34 | Retrospective Single center (P) | Mixed | CT only | Yes | CNN end-to-end | 121 | Yes | 47.9 | 1.00 |

| Skarping et al., 2022 | 37 | Retro-prospective Single center | Mixed | MG only | No | CNN end-to-end | 453 | Yes | 21.0 | 0.71 |

| Tan et al., 2022 | 35 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | CT and Clinical | No | CNN end-to-end | 324 | Yes | 22.8 | 0.77 |

BC, Breast cancer; Clinical, Clinical data; AI, Artificial intelligence; CNN, Convolutional neural network; Nr of Pts, Number of patients; (P), a Public dataset was involved; AUC, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve

Two additional retrospective studies utilized breast CT within end-to-end DL frameworks for pCR prediction. The first employed publicly available imaging data (QIN-Breast dataset from The Cancer Imaging Archive), with CT images obtained pre-NAST and after the first treatment cycle [34]. An ensemble deep transfer learning approach integrating pretrained ResNet and DenseNet architectures demonstrated exceptionally high predictive accuracy, achieving an AUC of 1.00 in internal testing [34]. The second retrospective, multicentric study combined pre-NAST CTI and clinical data [35]. Employing both quantitative radiomics and DL-based feature extraction through a custom MultiResUnet3D architecture, the study showed that combining imaging features with clinical data via logistic regression improved predictive performance to an AUC of 0.77, superior to either modality alone.

Lastly, a smaller retrospective single-center study assessed the predictive utility of pre-NAST breast 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CTI) [22]. Employing a pretrained ResNet architecture in an end-to-end DL framework, this investigation reported an AUC of 0.90; however, evaluation was limited to cross-validation.

Leveraging digital pathology imaging through deep learning

Thirteen studies utilized pre-NAST DP imaging to develop DL models for predicting pCR (Table 4). All studies were retrospective, with diverse BC subtype representations: seven examined mixed subtypes, four focused specifically on TNBC [24–26, 28], one on HER2+ BC [30], and another on HER2- BC (including both HR+/HER2− BC and TNBC cases) [33]. Eight studies used DP as the only data input [24–26, 33, 40, 65–67], reporting area AUC values ranging from 0.71 to 0.96 (median 0.80). Four studies combined DP-derived features with clinical data [28, 30, 68, 69], with reported AUC ranges between 0.75 and 0.89 (median 0.81). A single study integrated DP with CT, achieving an AUC of 0.93.

Table 4.

Summary of studies using digital pathology (DP) imaging as the primary input for pathologic complete response (pCR) prediction models

| Author | Citation nr | Study design | BC subtype | Data modalities | Longitudinal imaging | AI techniques | Nr of Pts | Held-out Cohort | Overall pCR Rate (%) | Best validation AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattarai et al., 2024 | 25 | Retrospective Single center | TNBC | DP only | No | CNN followed by CML | 76 | No | 57.9 | 0.71 |

| Fanucci et al., 2023 | 33 | Retrospective Multicenter | HER2- BC | DP only | No | CNN followed by CML | 113 | No | 29.2 | 0.71 |

| Aswolinskiy et al., 2023 | 67 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | Mixed | DP only | No | CNN followed by CML | 973 | Yes | 24.0 | 0.72 |

| Krishnamurthy et al., 2023 | 28 | Retrospective Single center | TNBC | DP and Clinical | No | CNN followed by CML | 243 | Yes | 37.4 | 0.75 |

| Li et al., 2022 | 66 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | DP only | No | CNN followed by CML | 874 | Yes | 25.6 | 0.78 |

| Zeng et al., 2024 | 69 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | DP and Clinical | No | CNN followed by CML | 440 | Yes | 28.2 | 0.78 |

| Li et al., 2022 | 65 | Retrospective Multicenter | Mixed | DP only | No | CNN followed by CML | 1035 | Yes | 24.5 | 0.79 |

| Li et al., 2024 | 26 | Retrospective Single center | TNBC | DP only | No | CNN end-to-end | 105 | No | 45.7 | 0.82 |

| Wang et al., 2025 | 30 | Retrospective Single center | HER2+ BC | DP and Clinical | No | TRA followed by CML | 399 | No | 59.1 | 0.84 |

| Li et al., 2021 | 68 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | DP and Clinical | No | CNN followed by CML | 540 | Yes | 18.9 | 0.89 |

| Saednia et al., 2023 | 40 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | DP only | No | CNN end-to-end | 207 | Yes | 25.1 | 0.89 |

| Zhang et al., 2023 | 38 | Retrospective Single center | Mixed | DP and CT | No | CNN followed by CML | 211 | Yes | 38.9 | 0.93 |

| Duanmu et al., 2022 | 24 | Retrospective Single center | TNBC | DP only | No | CNN end-to-end | 73 | No | 58.9 | 0.96 |

BC, Breast cancer; HER2+ BC, HER2-positive Breast cancer; HER2- BC, HER2-negative Breast Cancer; TNBC, Triple negative breast cancer; CT, Computed tomography; Clinical, Clinical data; AI, Artificial intelligence; CNN, Convolutional neural network; TRA, Transformer architecture; CML, Classical machine learning; Nr of Pts, Number of patients; (P), a Public dataset was involved; AUC, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve

Twelve investigations used WSIs, primarily captured with specialized scanners: eight at 40× magnification, three at 20× magnification, and one at 10× magnification. Ten of these studies utilized H&E staining exclusively, while two incorporated additional stains with proliferation markers (Ki67 and PH3) [24, 25]. One study deviated from WSIs, capturing selected fields via microscopy (20× objective) of HER2-stained slides, and employed a vision transformer for feature extraction followed by logistic regression, reporting an AUC of 0.84 through cross-validation without independent testing. The remaining 12 studies relied on CNN-based feature extraction. Three studies employed ResNet architectures, either pretrained followed by CML [38, 66] or trained de novo in end-to-end DL pipeline [24]. Two studies utilized Inception architectures combined with CML classifiers [65, 68], while two other investigations leveraged VGG architectures (one pretrained, followed by CML prediction [26, 69], the other trained de novo with DL prediction [26]). Other employed architectures included pretrained U-Net [67] and de novo trained Mask R-CNN [25] coupled with CML, and de novo trained CoatNet using an end-to-end DL approach [40]. Two studies introduced novel customized CNN architectures paired with CML classifiers [28, 33]. In summary, six studies employing pre-designed CNN architectures trained de novo reported AUC values ranging from 0.71 to 0.96 (median 0.86). Four studies utilizing pretrained CNN models achieved AUCs from 0.72 to 0.93 (median 0.78), whereas two studies employing custom-designed models achieved AUCs of 0.71 and 0.75.

Deep learning applied to molecular omics and clinical text data

We identified only one study falling in the category of investigations that applied DL on tumor molecular data (i.e. genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics and/or proteomics) (Table 5). In particular, this study involved 368 patients diagnosed with HER2-low BC from the I-SPY2 Trial [32]. Investigators applied DL on transcriptomic data (mRNA) as the primary data modality, and integrated it with clinical data (including textual elements from pathology reports) obtaining a final classifier with an excellent AUC of 0.92 in predicting pCR. The DL architecture consisted in a customized fully connected network with 6 hidden layers, that fused differential gene expression patterns with clinical elements in an end-to-end DL fashion.

Table 5.

Summary of a study using RNA sequencing data as the primary input for pathologic complete response (pCR) prediction models

| Author | Citation nr | Study design | BC subtype | Data modalities | Longitudinal imaging | AI techniques | Nr of Pts | Held-out cohort | Overall pCR Rate (%) | Best validation AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al., 2023 | 32 | Retrospective Multicenter (P) | HER2-low BC | RNA and Clinical | No | FCN end-to-end | 368 | Yes | 26.6 | 0.92 |

BC, Breast cancer; Clinical, Clinical data; AI, Artificial intelligence; FCN, Fully connected neural network; Nr of Pts, Number of patients; (P), a Public dataset was involved; AUC, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve

In this systematic review we did not identify any investigation that employed pre-surgical clinical data as the primary data input modality in DL-based predictors of pCR in BC patients undergoing NAST.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes the landscape of DL applications across multiple data types to predict pCR to NAST in BC. Our analysis of 51 studies reveals a rapidly evolving field with considerable potential, particularly for multimodal approaches, while also highlighting significant methodological heterogeneity and areas for future development.

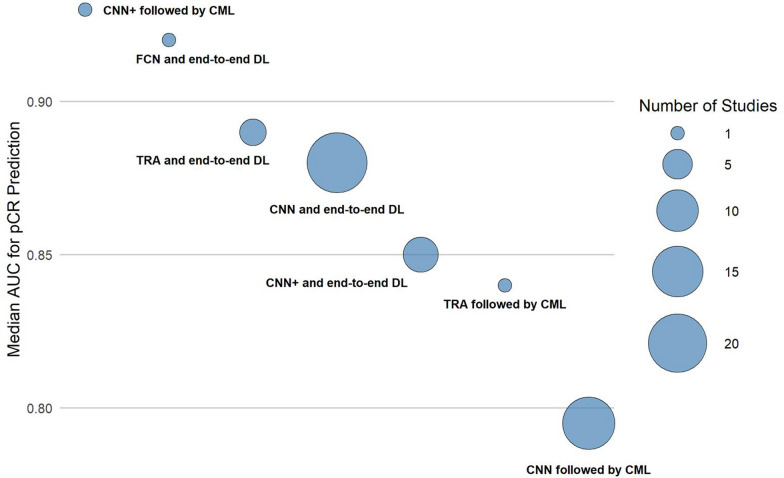

We confirm the growing interest in deep learning for pCR prediction, primarily using radiological data (MRI and US), followed by DP imaging (Fig. 2). Multimodal models generally performed better than single-modality models in the same study; however, formal statistical comparison was not reported. A compelling demonstration of how true multimodality and end-to-end DL can work in concert was published recently. Using a prospective, multicentre cohort of 1004 patients, the DL model fused pretreatment MRI, WSI pathology images and structured clinical variables inside one unified CNN-based pipeline, and achieved an external-test AUC of 0.88 and a prospective-test AUC of 0.91, significantly higher than any of its single-modality counterparts [70]. In our systematic review, clinical data integration was the most common strategy yielding some performance improvements, especially alongside MRI. Among the 51 studies, purely end-to-end CNN pipelines were not only the most common (n = 21) but also the most accurate (median AUC 0.88). When the CNN served only as a feature extractor and the final classifier was performed using conventional ML, performance dipped appreciably (median 0.80). Adding attention blocks to a CNN backbone yielded an intermediate benefit (median 0.85), while the small pool of transformer-only models posted a slightly higher median (0.89). A similar pattern emerged across input modalities: MRI-only models reached a median AUC of 0.84, which climbed to 0.88 once routine clinical variables were fused; DP rose modestly from 0.79 to 0.81 with the same addition, whereas US maintained high accuracy regardless of fusion (0.92 vs 0.90), probably because of the frequent addition of mid-treatment inputs. For instance, one of the studies we included in the systematic review extracted features from biopsy WSIs using a VGG16 CNN-architecture and, after fusing them with routine clinicopathological variables in an SVM, improved AUC from 0.79 to 0.84 in the training set and from 0.71 to 0.78 on an external cohort [69]. Beyond the modalities analysed in this review, additional imaging inputs are possible. An example is functional optical imaging which is also being explored in this context: a study fused co-registered US imaging with diffuse optical tomography (DOT) in a dual-input transformer, plus clinical variables, and achieved an AUC of 0.96 (vs 0.87 for US and 0.82 for DOT alone), underscoring that additional, complementary imaging streams can further enhance multimodal DL performance [71]. Taken together, these trends reinforce two messages already apparent in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1: (i) end-to-end deep learning usually outperforms hybrid pipelines, and (ii) incremental clinical context can improve performance, depending on the imaging modality involved. Incorporating longitudinal imaging during NAST boosted accuracy over baseline imaging alone, underscoring the value of capturing tumor dynamics during treatment. However, more than two imaging time points did not offer further gains. DL models achieved a median AUC of 0.88, with 35.3% reporting ≥ 0.90, indicating strong discrimination for pCR. Because many AUCs were reported from retrospective single-centre cohorts, these values should be interpreted cautiously. Median and mean AUC values were slightly higher (by 0.01–0.04) in studies with intermediate cohort sizes (156–400 patients) and those with intermediate-to-high pCR rates (above 27%), highlighting a limitation: model performance appears to degrade when pCR rates fall below 25%(Supplementary File 2). Interestingly, this trend toward higher AUC was even more pronounced (by 0.04–0.05) among studies that validated results independently on a held-out test cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2). Nonetheless, within these studies, the AUC values derived from independent testing cohorts (which we report in this study) were consistently lower compared to cross-validation AUC obtained from the training cohorts. From an assisted clinical decision-making perspective, an externally validated model that reaches an AUC of about 0.90 means that in roughly nine out of ten patient pairs the algorithm will correctly rank the likelihood of achieving pCR, giving the breast oncologist a reliable probability estimate on which to tailor (or even forego) neoadjuvant therapy intensity.

Fig. 3.

Bubble plot displaying the median Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) of studies grouped based on the deep learning (DL) architecture utilized. Each circle represents a set of studies, with relative dimension representing the number of studies included. CNN, Convolutional neural network; CNN + , Convolutional neural network augmented with additional modules like Attention mechanisms, etc.; TRA, Transformer architecture; CML, Classical machine learning

CNNs are the cornerstone, used in nearly 90% of studies for feature extraction within end-to-end pipelines. Many studies augment CNNs with attention, transformers, or LSTMs for longitudinal data, and a small but growing number rely solely on transformer architectures. Although end-to-end deep learning predominated, a minority (18 studies) used hybrid models with DL for feature extraction and conventional ML for data integration and final prediction. The optimal strategy remains unclear and likely depends on data characteristics and availability. Our findings align with broader trends of predictive models in oncology: moving from traditional statistical models or ML with handcrafted features (like radiomics) to DL enhances discriminative power, especially when integrating multiple data types. A prior meta-analysis of MRI-based ML for NAST response reported higher AUC for DL (0.92) than classical ML + radiomics (0.85), and showed that adding clinical or histopathologic information improved performance (0.90 vs. 0.82 for MRI alone) [72]. These results independently confirm the value of clinical integration and the benefit of multimodal data. Compared to earlier reviews focused on unimodal radiomics or classical ML, this review highlights the shift toward sophisticated, data-driven feature extraction and integration, while underscoring persistent challenges in standardization and validation.

Despite promising AUCs, most studies (90.2%) were retrospective with potential selection bias, which often inflates performance because favourable cases are unintentionally over-represented. Moreover, often studies used the same public datasets, limiting causal inference, generalizability, and introducing risk of overfitting. Although 76.5% included independent testing on held-out cohorts, they were often from the same institution and true external validation remains scarce. Methodological heterogeneity—in patient cohorts, BC subtypes, NAST regimens, imaging protocols, DL architectures, fusion strategies, pCR definitions, and performance reporting—hinders direct comparisons and precludes meta-analysis. Notably, molecular multi‑omics data remain underutilized: we found only one transcriptomics-based DL study for pCR prediction [32]. Yet prior work has shown many signals highlighting the potential predictive power of molecular multi-omics in the DL framework. In fact, DL has been successfully applied directly on raw cancer DNA sequence data for BC type prediction and driver gene identification [73], on epigenomic data (DNA methylation) for classifying BC subtypes [74], and in sophisticated efforts to integrate multi-omics data (including copy number alterations, mutations, methylation, RNA, and protein expression)—sometimes combined with clinical data—to predict broader outcomes like survival and drug response in BC [75–77]. More specifically on breast cancer, several recent molecular biology work underscores just how much actionable signal is being left unexploited. Metabolic and signalling drivers such as the RRP9-JUN/AKT axis [78] and ZFP64-mediated glycolytic reprogramming [79] have been shown to accelerate tumour growth, while a circSpdyA-encoded 127-aa micro-peptide directly binds FASN to boost lipogenesis and dampen NK-cell cytotoxicity [80]. Immune-modulatory molecules like MOSPD1, whose silencing augments response to anti-PD-L1 therapy [81], and epigenetic regulators such as the PML1-WDR5 complex [82] or the hypoxia-activated XBP1s/HDAC2/EZH2 cassette that represses ΔNp63α [83] further illustrate the breadth of mechanistic biomarkers now charted. Even single-patient multi-omic atlases, e.g. the claudin-low luminal B breast cancer case carrying high TMB and APOBEC signatures [84], show how layered genomic, epigenomic and immune biomarkers data can contain predictive information to complement other data inputs. Incorporating such mechanistic features, whether as raw omics tensors or distilled pathway scores, into future multimodal DL frameworks could enhance biological interpretability, synergise with WSI‐derived morphometry, and ultimately refine personalised therapy selection. Similarly, the complete absence of studies using DL primarily on pre-treatment clinical text data (e.g., EMR data, pathology/radiology reports, clinical notes) represents a missed opportunity. While classical ML approaches applied to structured clinicopathological data have shown moderate success in predicting pCR, achieving AUCs around 0.71–0.79 in recent studies [85, 86], these methods typically rely on pre-selected features. The potential of leveraging the richer, unstructured information within clinical narratives using advanced DL techniques like LLMs remains largely underexplored for pre-treatment pCR prediction in this context. Although one study demonstrated the feasibility of using LLMs to extract pCR information from post-surgery pathology reports [87], and the general power of LLMs for deep phenotyping from clinical text is established [88], no eligible study in our review applied these powerful text-processing models to predict pCR using pre-NAST clinical narratives. Critically, no study attempted to integrate all four major data domains (radiological, pathological, molecular, clinical), which would be necessary to build truly comprehensive predictive models.

Current DL models show strong potential but are not yet ready for routine clinical use. Their retrospective design, lack of external validation, and methodological variability must be addressed to ensure reliability in clinical decisions. Future research should prioritize prospective, multi‑center trials for robust validation, standardize MRI protocols, pCR definitions, and feature‑extraction methods, and adopt unified outcome measures to improve reproducibility. True multimodal integration should incorporate underutilized modalities using sophisticated fusion techniques beyond simple concatenation. This holistic approach holds substantial promise for improved predictive accuracy and personalized patient management. Moreover, ongoing exploration and application of advanced DL architectures, including transformers, graph neural networks and foundation models [89–91], should be encouraged.

Equally important is the development and implementation of explainable AI methods, which were formally included in the design by few of the studies included in the review [23, 58]. A recent example of good practice is in fact a Multi-modal Response Prediction model, which used Integrated Gradients to rank modality-specific contributions and confirmed that histopathological subtype and MRI-derived features were the principal drivers of its predictions, thereby providing clinicians with transparent, clinically plausible explanations for each case [23]. Explainability is critical for moving beyond the "black box" nature of DL models, fostering clinical trust, and clarifying the specific factors influencing predictions. Robust model evaluation beyond AUC is also critical. Decision curve analysis, model calibration, and assessments of clinical impact on patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness should be incorporated to determine whether high AUCs translate into clinically useful decision thresholds. Finally, fostering multi-institutional collaboration and employing privacy-preserving methods such as federated learning could overcome limitations associated with single-center studies. Indeed, federated learning approaches have already demonstrated feasibility in this domain, having been used to build predictors of NAST response by applying machine learning to WSIs and clinical data across different institutions while maintaining data privacy behind their respective firewalls [92]. This collaborative approach would facilitate model training on larger, more diverse datasets, thus enhancing generalizability and potential clinical utility.

The strengths of this review include a systematic search strategy across multiple databases and a focused synthesis of current methodologies, performance, and gaps. While another systematic review published in 2022 also explored DL for pathological complete response prediction, its focus was limited to MRI and clinical data [93], whereas the present review encompasses a broader range of modalities, offering a more comprehensive and updated perspective. However, its main limitation is the inability to perform a quantitative meta-analysis due to the significant heterogeneity across the included studies, necessitating a narrative synthesis without a single pooled estimate of effect size.

Conclusion

This systematic review highlights the potential of DL, particularly when applied multimodally, for predicting pCR to NAST in BC. This review demonstrates that multimodal DL approaches can achieve high discriminative performance for pCR prediction in retrospective cohorts; however, their clinical utility remains unproven without prospective validation. Likewise, multimodal models hold the potential to redirect patients to more effective/tolerated (escalation/de-escalation) schedules, considering the growing pipeline of neoadjuvant treatments. The integration of multiple data sources, most commonly imaging and clinical data, along with the use of longitudinal assessments during therapy, often demonstrates improved predictive performance compared to unimodal or baseline-only approaches. Despite these promising results, the field is characterized by significant methodological heterogeneity, a predominance of retrospective studies, and a lack of rigorous external validation, which currently limits the clinical applicability of these models. Advancing the field towards clinical utility requires prioritizing prospective multi-center validation studies, fostering standardization in data acquisition and reporting, developing innovative methods for integrating underutilized data like multi-omics and clinical text, exploring “new generation” DL architectures, and embedding explainable AI techniques. Addressing these challenges is crucial for building robust, generalizable, and trustworthy models capable of facilitating personalized treatment strategies in BC care.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Elisabetta Landi and Ashanti Zampa for technical and administrative support.

Author contributions

Eriseld Krasniqi: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Lorena Filomeno: methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing. Teresa Arcuri: methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing. Gianluigi Ferretti: writing—review and editing. Simona Gasparro: writing—review and editing. Alberto Fulvi: writing—review and editing. Arianna Roselli: writing—review and editing. Loretta D’Onofrio: writing—review and editing. Laura Pizzuti: methodology, writing—review and editing. Maddalena Barba: writing—review and editing. Marcello Maugeri-Saccà: supervision, writing-review and editing. Claudio Botti: writing—review and editing. Franco Graziano: writing—review and editing. Ilaria Puccica: writing—review and editing. Sonia Cappelli: writing-review and editing. Fabio Pelle: writing-review and editing. Flavia Cavicchi: writing—review and editing. Amedeo Villanucci: writing—review and editing. Ida Paris: writing-review and editing. Fabio Calabrò: writing-review and editing. Sandra Rea: writing-review and editing. Maurizio Costantini: writing—review and editing. Letizia Perracchio: writing—review and editing. Giuseppe Sanguineti: writing—review and editing. Silvia Takanen: writing—review and editing. Laura Marucci: writing—review and editing. Laura Greco: methodology, writing—review and editing. Rami Kayal: methodology, writing-review and editing. Luca Moscetti: writing-review and editing. Elisa Marchesini: writing—review and editing. Nicola Calonaci: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—review and editing. Giovanni Blandino: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing. Giulio Caravagna: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, supervision, writing-review and editing. Patrizia Vici: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported through funding from the institutional “Ricerca Corrente” granted by the Italian Ministry of Health.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary data files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Giulio Caravagna and Patrizia Vici have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Eriseld Krasniqi, Email: eriseld.krasniqi@ifo.it.

Teresa Arcuri, Email: teresa.arcuri@ifo.it.

References

- 1.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, Mehta K, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384:164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, Rajan R, Kuerer H, Valero V, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spring LM, Fell G, Arfe A, Sharma C, Greenup R, Reynolds KL, et al. Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and impact on breast cancer recurrence and survival: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2838–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer J-U, Costa SD, Eidtmann H, Fasching PA, et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houssami N, Macaskill P, von Minckwitz G, Marinovich ML, Mamounas E. Meta-analysis of the association of breast cancer subtype and pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3342–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rouzier R, Pusztai L, Delaloge S, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Andre F, Hess KR, et al. Nomograms to predict pathologic complete response and metastasis-free survival after preoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Zhang J, Wang B, Zhang H, He J, Wang K. A nomogram based on clinicopathological features and serological indicators predicting breast pathologic complete response of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan M, Wu G, Cheng H, Zhang J, Shao G, Li L. Radiomic analysis of DCE-MRI for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Eur J Radiol. 2017;94:140–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Li C, Wang H, Jiang L, Chen M. Comparison of radiomics-based machine-learning classifiers for the pretreatment prediction of pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer. PeerJ. 2024;12:e17683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saednia K, Lagree A, Alera MA, Fleshner L, Shiner A, Law E, et al. Quantitative digital histopathology and machine learning to predict pathological complete response to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients using pre-treatment tumor biopsies. Sci Rep. 2022;12:9690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sammut S-J, Crispin-Ortuzar M, Chin S-F, Provenzano E, Bardwell HA, Ma W, et al. Multi-omic machine learning predictor of breast cancer therapy response. Nature. 2022;601:623–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521:436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia H, Zhang J, Ma K, Qiao X, Ren L, Shi X. Application of convolutional neural networks in medical images: a bibliometric analysis. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2024;14:3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dammu H, Ren T, Duong TQ. Deep learning prediction of pathological complete response, residual cancer burden, and progression-free survival in breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE. 2023;18:e0280148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franco EF, Rana P, Cruz A, Calderón VV, Azevedo V, Ramos RTJ, et al. Performance comparison of deep learning autoencoders for cancer subtype detection using multi-omics data. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Wang Y. Extracting a biologically latent space of lung cancer epigenetics with variational autoencoders. BMC Bioinf. 2019;20:568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munquad S, Das AB. DeepAutoGlioma: a deep learning autoencoder-based multi-omics data integration and classification tools for glioma subtyping. BioData Min. 2023;16:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, Kim D, Kim S, So CH, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:1234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joo S, Ko ES, Kwon S, Jeon E, Jung H, Kim J-Y, et al. Multimodal deep learning models for the prediction of pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11:18800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J, Chen B, Cao H, Dai Q, Qin L, Zhang J, et al. Cross-modal deep learning model for predicting pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H, Yang M, Chen J, Yao G, Zou Q, Jia L. Multimodal deep learning approaches for precision oncology: a comprehensive review. Brief Bioinform. 2024;26:bbae699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulut G, Atilgan HI, Çınarer G, Kılıç K, Yıkar D, Parlar T. Prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer by using a deep learning model with 18F-FDG PET/CT. PLoS ONE. 2023;18:e0290543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Y, Ventura-Diaz S, Wang X, He M, Xu Z, Weir A, et al. An explainable longitudinal multi-modal fusion model for predicting neoadjuvant therapy response in women with breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15:9613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duanmu H, Bhattarai S, Li H, Shi Z, Wang F, Teodoro G, et al. A spatial attention guided deep learning system for prediction of pathological complete response using breast cancer histopathology images. Bioinformatics. 2022;38:4605–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattarai S, Saini G, Li H, Seth G, Fisher TB, Janssen EAM, et al. Predicting neoadjuvant treatment response in triple-negative breast cancer using machine learning. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;14:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Teodoro G, Jiang Y, Kong J. NACNet: A histology context-aware transformer graph convolution network for predicting treatment response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2024;118:102467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Z, Adrada BE, Candelaria RP, Elshafeey NA, Boge M, Mohamed RM, et al. Prediction of pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant systemic therapy in triple negative breast cancer using deep learning on multiparametric MRI. Sci Rep. 2023;13:1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnamurthy S, Jain P, Tripathy D, Basset R, Randhawa R, Muhammad H, et al. Predicting response of triple-negative breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy using a deep convolutional neural network-based artificial intelligence tool. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2023;7:e2200181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, Xie Y, Cui Y, Feng S, et al. Early prediction of treatment response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on longitudinal ultrasound images of HER2-positive breast cancer patients by Siamese multi-task network: a multicentre, retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;52:101562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Gao G, Tian C, Zhang J, Jiao D-C, Liu Z-Z. Next-generation sequencing based deep learning model for prediction of HER2 status and response to HER2-targeted neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2025;151:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S-Y, Lee J, Cho N, Kim Y-G. Deep-learning based discrimination of pathologic complete response using MRI in HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2024;14:23065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X, Lin Z, Yu Q, Qiu C, Lai C, Huang H, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic model for HER2-low breast cancer to evaluate neoadjuvant therapy. Gland Surg. 2023;12:183–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fanucci KA, Bai Y, Pelekanou V, Nahleh ZA, Shafi S, Burela S, et al. Image analysis-based tumor infiltrating lymphocytes measurement predicts breast cancer pathologic complete response in SWOG S0800 neoadjuvant chemotherapy trial. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2023;9:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rezaeijo SM, Ghorvei M, Mofid B. Predicting breast cancer response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy using ensemble deep transfer learning based on CT images. J Xray Sci Technol. 2021;29:835–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi TH, Hian OH, Kumaran AM, Tan TJ, Cong TRY, Su-Xin GL, et al. Multi-center evaluation of artificial intelligent imaging and clinical models for predicting neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;193:121–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Förnvik D, Borgquist S, Larsson M, Zackrisson S, Skarping I. Deep learning analysis of serial digital breast tomosynthesis images in a prospective cohort of breast cancer patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Radiol. 2024;178:111624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skarping I, Larsson M, Förnvik D. Analysis of mammograms using artificial intelligence to predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: proof of concept. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:3131–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Wu Q, Yin W, Yang L, Xiao B, Wang J, et al. Development and validation of a radiopathomic model for predicting pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang C, Zhang X, Qu T, Yang X, Xiu Y, Yu X, et al. The prediction of pCR and chemosensitivity for breast cancer patients using DLG3, RADL and Pathomics signatures based on machine learning and deep learning. Transl Oncol. 2024;46:101985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saednia K, Tran WT, Sadeghi-Naini A. A hierarchical self-attention-guided deep learning framework to predict breast cancer response to chemotherapy using pre-treatment tumor biopsies. Med Phys. 2023;50:7852–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Fan Y, Xu D, Li Y, Zhong Z, Pan H, et al. Deep learning radiomic analysis of DCE-MRI combined with clinical characteristics predicts pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1041142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hao X, Xu H, Zhao N, Yu T, Hamalainen T, Cong F. Predicting pathological complete response based on weakly and semi-supervised joint learning from breast cancer MRI. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2023;2023:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Deng J, Huang J, Mei L, Liao N, Yao F, et al. Monitoring response to neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer in all treatment phases using an ultrasound deep learning model. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1255618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang F, Zou Z, Sakla N, Partyka L, Rawal N, Singh G, et al. TopoTxR: A topology-guided deep convolutional network for breast parenchyma learning on DCE-MRIs. Med Image Anal. 2025;99:103373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jing B, Wang K, Schmitz E, Tang S, Li Y, Zhang Y, et al. Prediction of pathological complete response to chemotherapy for breast cancer using deep neural network with uncertainty quantification. Med Phys. 2024;51:9385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J, Li X, Wang G, Zeng W, Zeng H, Wen C, et al. Time-series MR images identifying complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer using a deep learning approach. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2025;61:184–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong T, Li D, Gu J, Chen G, Bai G, Yang X, et al. Dual-input transformer: An end-to-end model for preoperative assessment of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer ultrasonography. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27:251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gu J, Tong T, Xu D, Cheng F, Fang C, He C, et al. Deep learning radiomics of ultrasonography for comprehensively predicting tumor and axillary lymph node status after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: a multicenter study. Cancer. 2023;129:356–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Comes MC, Fanizzi A, Bove S, Boldrini L, Latorre A, Guven DC, et al. Monitoring over time of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients through an ensemble vision transformers-based model. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e70482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang M, Li C-L, Luo X-M, Chuan Z-R, Lv W-Z, Li X, et al. Ultrasound-based deep learning radiomics in the assessment of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021;147:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang Y, Zhu T, Zhang X, Li W, Zheng X, Cheng M, et al. Longitudinal MRI-based fusion novel model predicts pathological complete response in breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter, retrospective study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Li X, Zhang H, Duan T, Zhang C, Zhao T. Deep learning radiomics based on two-dimensional ultrasound for predicting the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Ultrason Imaging. 2024;46:357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y-X, Liu Q-H, Hu Q-H, Shi J-Y, Liu G-L, Liu H, et al. Ultrasound-based deep learning radiomics nomogram for tumor and axillary lymph node status prediction after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Acad Radiol. 2025;32:12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verma M, Abdelrahman L, Collado-Mesa F, Abdel-Mottaleb M. Multimodal spatiotemporal deep learning framework to predict response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Diagnostics (Basel) [Internet]. 2023;13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37443648/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Liu MZ, Mutasa S, Chang P, Siddique M, Jambawalikar S, Ha R. A novel CNN algorithm for pathological complete response prediction using an I-SPY TRIAL breast MRI database. Magn Reson Imaging. 2020;73:148–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Comes MC, Fanizzi A, Bove S, Didonna V, Diotaiuti S, La Forgia D, et al. Early prediction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy response by exploiting a transfer learning approach on breast DCE-MRIs. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massafra R, Comes MC, Bove S, Didonna V, Gatta G, Giotta F, et al. Robustness evaluation of a deep learning model on sagittal and axial breast DCE-MRIs to predict pathological Complete Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Pers Med. 2022;12:953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Comes MC, Fanizzi A, Bove S, Didonna V, Diotiaiuti S, Fadda F, et al. Explainable 3D CNN based on baseline breast DCE-MRI to give an early prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Comput Biol Med. 2024;172:108132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.El Adoui M, Drisis S, Benjelloun M. Multi-input deep learning architecture for predicting breast tumor response to chemotherapy using quantitative MR images. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2020;15:1491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qu Y-H, Zhu H-T, Cao K, Li X-T, Ye M, Sun Y-S. Prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer using a deep learning (DL) method. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:651–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng Y, Cheng Z, Gong C, Zheng C, Zhang X, Wu Z, et al. Pretreatment DCE-MRI-based deep learning outperforms radiomics analysis in predicting pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:846775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gu J, Zhong X, Fang C, Lou W, Fu P, Woodruff HC, et al. Deep learning of multimodal ultrasound: Stratifying the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer before treatment. Oncologist. 2024;29:e187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie J, Shi H, Du C, Song X, Wei J, Dong Q, et al. Dual-branch convolutional neural network based on ultrasound imaging in the early prediction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:812463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.You J, Huang Y, Ouyang L, Zhang X, Chen P, Wu X, et al. Automated and reusable deep learning (AutoRDL) framework for predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer using ultrasound images: a retrospective, multicentre study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;69:102499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li F, Yang Y, Wei Y, Zhao Y, Fu J, Xiao X, et al. Predicting neoadjuvant chemotherapy benefit using deep learning from stromal histology in breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li B, Li F, Liu Z, Xu F, Ye G, Li W, et al. Deep learning with biopsy whole slide images for pretreatment prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a multicenter study. Breast. 2022;66:183–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aswolinskiy W, Munari E, Horlings HM, Mulder L, Bogina G, Sanders J, et al. PROACTING: predicting pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer from routine diagnostic histopathology biopsies with deep learning. Breast Cancer Res. 2023;25:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]