Abstract

Background

The retrogenesis hypothesis (RH) suggests that the functional and cognitive decline observed in Alzheimer's disease dementia mirrors in reverse order the brain development during childhood and adolescence.

Objective

Equivalent electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns between older adults across different cognitive decline stages and children across different brain maturation stages were directly compared.

Methods

To capture the complex patterns that allow for such a comparison, a regression model was trained on EEG data from N = 510 older adults, at different stages of cognitive reserve, to identify EEG markers predictive of global cognitive status. The model was then applied on the same EEG markers of N = 696 children across different ages.

Results

The model predicted MMSE scores with an average error of 2.53 and R2 of 0.80. When applied to children, predictions correlated positively with age (r = 0.73). Key predictors of cognitive function concordant in both populations were theta coherence (right frontal-left temporal/parietal), temporal Hjorth complexity, and beta edge frequency, supporting the RH.

Conclusions

These EEG features were inversely associated between older adults and children, supporting a functional underpinning of the retrogenesis model of dementia. Clinical validation of these biomarkers could favor their use in the continuous monitoring of cognitive function.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, cognitive function, developmental age, electroencephalography, frontotemporal dementia, Hjorth complexity, machine learning, Mini-Mental State Exam, spectral coherence

Introduction

The retrogenesis hypothesis (RH), initially coined by Reisberg et al. (1999/2002),1,2 postulates that the abilities lost in the incipient stages of Alzheimer's disease (AD) are those acquired later during development, between the ages of 13 and 19 years (e.g., holding a job, critical thinking). 3 As AD progresses to mild and moderate stages, individuals lose cognitive abilities typically developed between the ages of 5 to 12 years (e.g., handling simple finances, selecting proper clothing). In the later stages of AD, patients lose cognitive abilities acquired by infants younger than 5 years (e.g., speaking, walking). From a behavioral point of view, this theory is supported by various lines of evidence, including clinical functional observations, cognitive, and language studies.4–8 Notably, Rubial-Álvarez et al. (2013) have shown the progressive patterns of functional and cognitive decline observed in AD patients to be the inverse of those of acquisition of the same capacities in children aged 4 to 12 years old. 9 From a neuroanatomical point of view, the brain areas most affected by AD (e.g., hippocampus and association cortex) typically mature later during development.10–12 Neuroimaging studies on the RH typically examined only older populations without direct comparison with children and adolescents, with few exceptions, for example in examining white matter tracts. 12 Moreover, similar retrogenic mechanisms are observed in other neuropathological processes, such as those in frontotemporal dementia (FTD).2,13

A number of methods can be employed to assess the impairment or retention of cognitive function in older individuals and cognitive development in children. Having a comparable measure for both older subjects and children, however, poses a significant challenge. For the former, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a widely employed tool to measure global cognitive status in a quantitative and objective manner, facilitating comparisons with other studies in the field. The MMSE is a 30-point scale, ranging from normal cognition to severe impairment, reflecting cognitive decline in various domains that are relevant to the RH, including orientation, memory, attention, language, and visuospatial skills. 14 These domains are known to be affected in a specific order during AD progression, making the MMSE appropriate to study the RH. Nevertheless, the use of MMSE has some limitations such as its suboptimal sensitivity in early cognitive decline, assessment of executive function, and its comparability with children's development.

Electroencephalograms (EEG) provide a non-invasive, complementary proxy for assessing brain function across the lifespan, making them suitable for testing the RH. In contrast, more invasive neuroimaging, or molecular markers, though informative, are typically not acquired in children. This modality is also inexpensive, widely available, and commonly acquired for multiple clinical purposes not only in older subjects but also in children. Multiple studies have shown that certain EEG features are associated with cognitive decline and the progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia. 15–18 These reflect abnormalities in the brain's neuromodulatory subcortical and thalamocortical systems underpinning altered cortical arousal and vigilance in amnestic MCI (aMCI) individuals and AD patients during the disease progression. Therefore, we investigated whether and how EEG patterns could serve as a solid and reliable link between cognitive function decline and developmental age.

This study aimed to test the RH by directly mapping the EEG patterns of older subjects on to those of children and adolescents. We used a machine learning (ML) approach to analyze non-linear and complex interactions of EEG features between both populations. Extending previous EEG-based studies that have focused on discretely classifying EEG patterns into distinct groups (e.g., AD, MCI, cognitive controls),15–18 we explored a continuous regression between specific EEG features and MMSE scores of the older subjects across different stages of cognitive decline (cognitively normal, subjective cognitive decline, MCI, and dementia). We then assessed if the same EEG patterns would predict cognitive status and, in turn, developmental age in children (3 to 18 years of age). A significant positive correlation between the children's predictions and their respective ages would support the RH, directly matching the EEG patterns of the older subjects with those of children at comparable developmental stages. This approach provides an operationalized perspective on the RH. Interpreting the relevant EEG features for such correlation may reveal novel aspects of the neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes that mirror each other in both populations.

Methods

To directly compare the EEG patterns of children with those of older subjects, we devised a machine learning (ML) strategy to capture complex patterns that might not be apparent through simple statistical analysis. Our goal was to develop a ML model that serves as a function, f, capable of estimating the cognitive status of individuals from both populations based on their EEG patterns, in order to match different stages of child development with different stages of dementia progression.

First, we trained an ML regression model using the EEG patterns of older subjects, , to estimate their MMSE scores, . This training process resulted in a function that maps EEG patterns to numerical cognitive status values. Next, we applied this trained function, f, to the same EEG patterns of children, . This produced cognitive status values, , for the children. We then examined the correlation between and the respective children's ages. A positive correlation would suggest that the RH holds true according to these EEG patterns. With this framework, we then studied this mapping of EEG patterns into cognitive status, f, to understand how these patterns establish a link between the cognitive status of older subjects and age in children, using ML explainability techniques.

Older participants

For the older population, we analyzed EEG signals and cognitive assessment scores from four cohorts, collected at different clinics and locations. Table 1 summarizes their demographics, MMSE, and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) distributions. For simplicity, each cohort is identified by a letter, and the combined data will be referred to as the “older cohort” or “older dataset”.

Table 1.

Characterization of the older cohort (top panel) and the pediatric cohort (bottom panel).

| Cohort | Group | Subjects | EEG Sessions | Age | Gender | MMSE | CDR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | SMC | 318 | 631 | 76.0 ± 3.5 [69, 85] | 44% M | 28.7 ± 0.9 [27, 30] | 0 | |

| B | Nold | 17 | 17 | 78.0 ± 6.3 [69, 88] | 58% M | 29.1 ± 0.9 [28, 30] | 0 | |

| AD | 21 | 21 | 77.1 ± 4.3 [65, 83] | 57% M | 19.6 ± 3.4 [12, 24] | 1.52 ± 0.6 | ||

| C | Nold | 29 | 29 | 67.9 ± 4.5 [57, 78] | 62% M | 30.0 ± 0.0 [30, 30] | 0 | |

| FTD | 23 | 23 | 63.6 ± 8.2 [44, 78] | 61% M | 22.7 ± 8.2 [18, 27] | 0.75 ± 0.26 | ||

| AD | 36 | 36 | 66.4 ± 7.9 [49, 79] | 33% M | 17.5 ± 4.5 [4, 23] | 1.00 ± 0.54 | ||

| D | Nold | 23 | 23 | 68.7 ± 8.5 [56, 83] | 39% M | 28.3 ± 1.7 [23, 30] | 0 | |

| FTD | 14 | 14 | 70.5 ± 10.6 [57, 87] | 79% M | 26.1 ± 3.2 [19, 30] | [0.5, 2] | ||

| AD | 29 | 29 | 76.0 ± 7.7 [64, 98] | 31% M | 22.8 ± 2.8 [16, 27] | [0.5, 2] | ||

| All | Nold | 69 | 69 | 70.5 ± 7.4 [56, 83] | 53% M | 29.2 ± 1.3 [23, 30] | 0 | |

| SMC | 318 | 631 | 76.0 ± 3.5 [69, 85] | 44% M | 28.7 ± 0.9 [27, 30] | 0 | ||

| FTD | 37 | 37 | 66.2 ± 9.6 [44, 87] | 68% M | 23.7 ± 3.4 [18, 30] | [0, 2] | ||

| AD | 86 | 86 | 72.5 ± 9.0 [49, 98] | 38% M | 19.9 ± 4.3 [4, 27] | [0, 2] | ||

| Total | 510 | 823 | 74.0 ± 6.7 [44, 98] | 46% M | 26.9 ± 4.1 [4, 30] | [0, 2] | ||

| P | - | 59 | 62 | 6.8 ± 0.9 [3.3, 7.9] | 58% M | - | - | |

| 233 | 250 | 10.5 ± 1.5 [8.0, 13.0] | 64% M | |||||

| 415 | 477 | 15.4 ± 1.4 [13.0, 18.1] | 32% M | |||||

| Total | 696 (unique) | 789 | 12.8 ± 3.4 [3.3, 19.3] | 45% M | - | - | ||

Cohorts are shortly identified with one letter, and, when applicable, grouped by diagnosis: cognitive controls (Nold), with subjective memory complains (SMC), with Alzheimer's disease (AD), or with frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Age is given in years, and gender distribution is given as the ratio of male (M) participants. For continuous values, mean and standard deviation is provided as well as the range in square brackets.

Cohort A consisted of 316 participants with subjective memory complaints (SMCs), who participated in the INSIGHT-preAD study (2018). 19 Each underwent two 30-s eyes-closed resting-state EEG (rsEEG) sessions at the Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France. All participants presented with normal cognitive performance in psychometric testing at the time of recording, with MMSE scores of 27 or higher, and a CDR score of 0. Exclusion criteria included presymptomatic monogenic AD, neurological conditions (particularly epilepsy, extrapyramidal signs, visual hallucinations, brain tumor, subdural hematoma, head trauma history, and stroke in the previous 3 months), as well as other systemic or chronic conditions.

Cohort B comprised 38 participants recruited at the University Sapienza of Rome, Italy, first described in Babiloni et al. (2022). 20 Of these, 21 subjects had AD dementia (ADD) with MMSE scores between 12 and 24, and the remaining 17 were cognitively normal controls (Nold) with MMSE scores of 28 or higher and a CDR score of 0. Each participant underwent one eyes-closed rsEEG recording, with the corresponding MMSE test taken within 1 month before or after the EEG recording. Exclusion criteria included being younger than 55 years old; presence of cardiovascular, psychiatric, or neurological disorders; chronic use of analgesics, sedatives or hypnotics; and a Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) score over 5.

Cohort C included 88 participants recruited at the General University Hospital of Thessaloniki, Greece, first described in Miltiadous et al. (2021). 21 Of these, 36 had ADD, 23 had FTD, and 8 were Nold with no dementia diagnosis and MMSE scores of 30 and a CDR score of 0. Participants with ADD and FTD received their diagnoses a median of 25 months prior to EEG recording and had MMSE scores between 4 and 27. Each participant underwent one eyes-closed rsEEG recording. No dementia-related comorbidities were reported.

Cohort D included 66 participants recruited from clinics in five Latin American countries, first described in Prado et al. (2023). 22 Of these, 29 had ADD with Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) 23 scores between 9 and 22, 14 had FTD with MoCA scores between 12 and 30, and 23 were Nold with MoCA scores between 17 and 29 and a CDR score of 0. For coherence with other cohorts, MoCA scores were converted to MMSE scores using the equivalent weighted mean score reported by Fasnacht et al. (2023), 24 derived empirically from a large cohort who took both tests. Exclusion criteria included neurological conditions (e.g., brain tumor, brain hemorrhage, prion disease, Huntington's disease, ischemic or hemorrhagic conditions, history of stroke), B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, renal or liver insufficiency, and other systemic or chronic conditions.

Ethics statement: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their representatives, and study protocols were approved by the local institutional review boards and ethical committees, as detailed in each mentioned reference.

Children and adolescent participants

A basis set of 1419 participants was retrospectively and randomly selected from the in- and outpatients of the Department of Neurology, Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, and Psychotherapy in Childhood and Adolescence (KJPP) at the University Medical Centre of Rostock, Germany. Exclusion criteria based on the ICD-10 codes present in the clinical database reduced the cohort to 696 participants. Subjects with epilepsy, head trauma, congenital disorders, liver, endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases were excluded. Most importantly, participants with intellectual and developmental disorders were excluded due to their potential to significantly confound EEG-based cognitive assessment, ensuring that the included children were typically developing.

However, other psychiatric conditions are common in pediatric populations, which were not excluded. Included participants have other psychiatric symptoms or conditions, primarily behavioral and emotional (see Supplemental Table 1). While these participants may present with various other symptoms, the absence of cognitive disorders or deficits minimizes the likelihood of biased results, ensuring that the EEG measurements remain valid for evaluating cognitive function. This approach aligns with standard research practices, 25 where complete exclusion of all psychiatric conditions would result in a sample that is not representative of the typical child and adolescent population. Moreover, in pediatric populations with non-cognitive psychiatric conditions, cognitive abilities generally evolve predictably with age and education, even in children born preterm, making chronological age a pragmatically valid marker of cognitive development. 26 For example, neuroimaging and longitudinal cohort studies corroborate that predictable trajectories in memory, executive function, and verbal reasoning persist in mood and behavioral disorders, albeit with modulated efficiency.27–29 This predictability persists even in the presence of conditions like anxiety, depression, or conduct problems, provided these disorders do not co-occur with significant neurological impairments.27,28,30 Therefore, different development trajectory slopes may affect EEG feature variability, but not its general predictability. Although the included disorders are associated with some specific EEG features (e.g., ADHD-related theta/beta ratios 31 ), there is no current evidence that these features indicate cognitive disabilities comparable to those observed in cognitive decline in older adults – which is the purpose of this study.

The cohort included children as young as 3 years old and adolescents up to 18 years old, with a mean age of 13.2 ± 3.2 years. Most participants underwent one ambulatory EEG acquisition, while others had up to five longitudinal recordings, averaging 1.13 recordings per participant. Demographic details are summarized in the lower panel of Table 1 (cohort P).

Ethics statement: Data were collected as part of clinical routine, with approval for research use, while maintaining data privacy and anonymization, granted by the ethics committee of the University Medicine Rostock (Number of IRB-Board Approval #A 2018-0121). The studies are being conducted in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and its later amendments.

Electroencephalogram acquisition, selection, and denoising

In all EEG sessions, participants were seated comfortably in a light-dimmed room. Recordings may include different tasks and varied in session length and equipment specifications in each center, which were harmonized to ensure consistency. Only resting-state eyes-closed segments were used in this study.

The same denoising pipeline was applied to all datasets, schematically represented in Supplemental Figure 1, which includes filtering, downsampling to 128 Hz, attenuation and removal of heartbeat artifacts, bad channel interpolation, removal of noisy segments, and Independent Component Analysis to attenuate artifacts.

Post-denoising, the quality of each 24-s segment was assessed and ranked using three signal quality indices (SQIs) proposed in Pedroni et al. (2019). 32 A non-overlapping set of segments with the best quality was created for each session, as depicted in Supplemental Figure 2, which met criteria for downstream analysis.

Further details on acquisition protocols and pre-processing methods are provided in the Supplemental Material.

Electroencephalogram features

Features were extracted from the highest-quality, non-overlapping 24-s segments of each EEG session, divided into three 8-s blocks, with the results averaged. A total of 940 features spanning time, frequency, and connectivity domains were computed to capture EEG signal dynamics related to cognitive processes, which are summarized in Supplemental Table 2.

Hjorth features, or Hjorth parameters – activity, mobility, and complexity – were computed per channel like in Jiao et al. (2023), 33 as indicators of overall signal power, the proportion of standard deviation of the power spectrum, and the level of chaotic behavior in the EEG signal, respectively.

Spectral and connectivity features were extracted in five distinct frequency bands (or rhythms): Delta (1–4 Hz), Theta (4–8 Hz), Alpha (8–12 Hz), Beta (12–30 Hz), and Gamma (30–45 Hz). Key spectral metrics included relative power, entropy, and peak and edge frequencies, computed channel- and band-wise as in Al Zoubi et al. (2024). 34 Connectivity features, including coherence (COH) and phase lag index (PLI), were computed band- and region-wise as in Teipel et al. (2017), 35 to assess inter-regional synchrony across the regions Frontal, Temporal, Parietal, and Occipital.

Supplemental Table 3 provides the number of examples extracted from each individual dataset and the mean number of 24-s segments per unique session.

Oversampling strategies

The imbalance of MMSE scores in the older dataset is evident in Table 1, with fewer subjects having lower MMSE scores (0–15) compared to higher scores (16–30). Supplemental Figure 4A also illustrates this MMSE distribution in the older dataset. This distribution reflects the composition of the data from research cohorts focusing mainly on early stages of cognitive decline. This scarcity of examples with low MMSE scores will hinder the learning process of the ML regressor. To address this, two state-of-the-art oversampling strategies were employed. First, interpolation was used to generate examples for non-represented MMSE scores by linearly interpolating existing examples between MMSE 4 and 30. This ensured a finer resolution of MMSE scores, especially in underrepresented ranges. Second, Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) 36 for regression was applied to balance the number of examples across all MMSE scores. SMOTE generates synthetic examples by interpolating between an example and one of its five nearest neighbors, ensuring that these new examples are similar to real ones while filling gaps in underrepresented ranges. The detailed methodology is provided in Supplemental Material Section IV. These strategies were iteratively applied until achieving a balanced dataset with a minimum resolution of one MMSE score.

Machine learning regressor

A Gradient Boosting regressor was developed, using Scikit-learn 37 default implementation, to estimate MMSE scores from EEG features. Gradient Boosting combines multiple weak learners, such as decision trees, to form a robust predictive model by sequentially improving the residuals of previous models 38 . We used a tree-based model due to its typical effectiveness with large feature sets.

The model's hyperparameters were empirically optimized to minimize the absolute error between the predicted and actual MMSE scores obtained during neuropsychological assessments. It was found that the best design was with 300 estimators/trees, each with a maximum depth of 15. Supplemental Table 5 gives the complete hyperparameter settings and other design details for reproducibility. The next subsections explain the feature selection, training and testing procedures followed.

Selection of the best features for MMSE estimation

Feature selection was performed on the older dataset to identify the EEG features most predictive of MMSE scores. The older dataset was split, ensuring stratification by MMSE, age, and gender. One half was used for feature selection via Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) 39 and the other reserved for validation. The oversampling described previously was applied to mitigate low MMSE sample scarcity. RFE iteratively eliminated features, stopping when R-squared did not improve for 10 steps, producing a subset of empirically relevant features. These features were validated by training a model on a 70/30 train-test split scheme, ensuring stratification and subject independence between train and test sets. Evaluation was done according to the weighted Mean Absolute Error (WMAE), weighted Mean Squared Error (WMSE), and weighted R-squared (WR2) metrics computed according to MMSE frequencies in the test set. Although conducted on the older population with the MMSE score – a surrogate of global cognitive status – we hypothesized that these features would be indicative of cognitive performance across different age groups, including children and adolescents.

Validation of MMSE regressor on the older population

After feature selection, the model design was evaluated for its performance in estimating MMSE scores of the older population with the selected relevant features. A leave-one-example-out cross-validation (LOOCV) 40 scheme was followed. Despite being computationally expensive, LOOCV minimizes the impact of MMSE imbalance on model evaluation. Detailed methodology is given in Section IV of Supplemental Material. In LOOCV, each example is used for validation exactly once. At the end of all validation folds, the average of WMAE and WMSE metrics are taken from all validation examples, weighted accordingly to MMSE score frequency. The WR2 is also computed from all validation examples. These metrics were weighted according to MMSE score frequency to get a more reliable estimate of the model performance in an ideally balanced dataset. The model's hyperparameters were optimized to minimize the WMAE and WMSE values and maximize the WR2 (see Supplemental Table 5).

Training full-dataset model with older population

To achieve maximum predictive power, the optimized model was retrained on the entire older dataset, using all available examples from the older dataset, yielding a final “full-dataset” model intended for testing on the children's data. As before, the dataset was oversampled to address MMSE imbalance. Supplemental Figure 4 shows the MMSE distribution of the older dataset with real examples only, with interpolated examples added, and with SMOTE-generated examples added.

Applying trained full-dataset model on the children's population

The full-dataset model was then applied to EEG features extracted from dataset P, without oversampling, to test the RH. The model's outputs, ranging from 0 and 30, should not be interpreted as MMSE scores, as these would not be meaningful for children. Instead, they serve as a unitless indicator of global cognitive status of the subject to whose EEG of the input features belongs. Given that only children without developmental or cognitive disabilities were selected, their chronological age served as a surrogate for cognitive status to evaluate the model's performance. Therefore, a significant positive rank correlation between the model's outputs and children's ages would support the RH.

The normalized WR2 and the F-statistic of these predictions on children were computed using ordinary least squares (OLS) fitting to determine if predicted MMSE and age were two dependent variables. Moreover, the distribution of these predictions and age was checked against the RH boundaries proposed in Reiseberg et al. (1999), 1 where each MMSE score is mapped to a developmental age interval. Since the model was trained to output MMSE scores, we calculated the ratio of predictions falling in the correct developmental age interval. Additionally, the accuracy of predictions was computed in three larger developmental age intervals corresponding to MMSE ranges, where independence between the two variables was tested using a chi-squared test ( ). If MMSE and age were to be dependent, this would provide evidence supporting the RH, indicating that the EEG features related to cognitive status in older subjects were mirrored in children.

Explaining features importance

To interpret the model's performance on both populations, we employed a series of techniques to understand which EEG features have the most impact in predicting cognitive performance.

Using Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI), 41 we quantified each feature's contribution to MMSE prediction accuracy in the older population. MDI measures the average reduction in impurity when a feature is used for splitting in tree-based models, identifying features with the highest impact on minimizing prediction error.

To determine which features contribute most to accurate predictions in dataset P, considering how the relationship between developmental age and MMSE score is described in Reiseberg et al. (1999), 1 we employed a permutation testing. 42 By shuffling each feature independently, we assessed the resulting change in model performance. A significant drop from baseline WR2 indicates a feature's importance in accurate predictions. This permutation procedure was repeated 10 times, and feature importances were averaged to mitigate random experimental error. Partial dependence plots (PDPs) 38 further illustrated how key features influenced predictions by showing the effect of varying feature values while keeping others constant. To create these PDPs, dataset P was divided into 100 percentiles according to each feature of interest.

Finally, we identified EEG features linked to cognitive function across both populations. ANOVA tests assessed feature distributions within each cognitive range at a 95% confidence level, while Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) tests compared feature distributions between age groups to evaluate RH alignment. A significant difference in the distributions of counterpart age and MSME groups in both populations would not support the RH. Feature correlations were visualized through Pearson correlation matrices, and cosine similarity quantified matrix symmetry across age groups.

Results

Features selected for MMSE estimation

Approximately 50% of examples from the older dataset were randomly sampled for the feature selection process. The recursive feature elimination (RFE) process concluded with 80 features, as further iterations did not improve WR2. Hence, these 80 features were selected as the most relevant features for MMSE estimation, given the model and population heterogeneity of the dataset. Supplemental Table 4 enumerates these 80 selected features. Among these features, 36 were coherence (COH) features, 28 were spectral features, 10 were Hjorth features, and 6 were phase lag index (PLI) features.

The remaining half of the older dataset was used to independently assess the performance of these 80 features in estimating MMSE scores. A new model was trained with 70% of this subset and evaluated on the remaining 30%, yielding a WMAE of 2.789 ± 0.310, a WMSE of 13.051 ± 0.299 and a WR2 of 0.723 ± 0.071, demonstrating the features’ efficacy in estimating MMSE scores. The regression plot for the test set is shown in Supplemental Figure 3.

Validation of MMSE estimation on the older population

The model's hyperparameters were optimized to minimize the predictions absolute error, and its design details can be found in Supplemental Table 5. To validate the model design for MMSE estimation, a LOOCV scheme was employed using the older dataset, involving 2297 folds. Each fold used one example for validation and the remaining 2296 examples for training. After augmentation, training sets contained 5400 examples, with 200 instances per MMSE score.

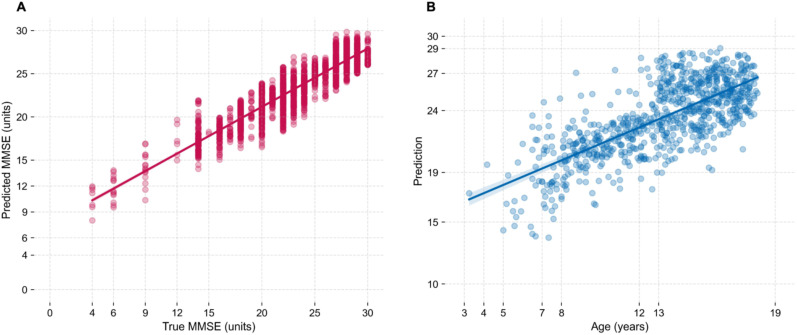

The MMSE predictions and true scores for each validation example are plotted in Figure 1A. Across all validation sets, the average WMAE was 2.527 ± 3.069 and the average WMSE was 10.552 ± 0.272. A linear regression using all examples’ predictions and true scores attained a WR2 of 0.804 ± 0.066, indicating the model's strong performance in estimating MMSE scores based on the selected EEG features from older subjects.

Figure 1.

Regression of EEG features from older subjects (left, A) and of EEG features from children (right, B). A) Regression between predicted and true MMSE scores of validation examples of LOOCV procedure, with the older dataset. Each point represents one validation example independently evaluated on each CV fold. Regression is taken on all points (2297 points). B) Regression between the chronological age of children and the numerical predictions indicative of cognitive function outputted by the full-dataset MMSE regressor model. Each point represents one session of dataset P (789 points).

Training full-dataset model with older population and applying it to the children's population

With the validated model design and selected features, a new model was trained using all examples from the older population. The older dataset was augmented with the two oversampling techniques previously described, making up a total of 23,842 examples to train this model.

Following training of the full-dataset model of older subjects, the examples of children's features (dataset P) were input to the model, which outputted corresponding numerical predictions. The numerical values outputted should be interpreted as an indirect measure of cognitive status, not as MMSE scores. Figure 1B shows the predictions obtained for the examples of dataset P against the corresponding chronological age of each subject at the time of EEG recording. Pearson and Spearman rank correlations between these predictions and the children's age were 0.7250 ( ) and 0.7024 ( ), respectively, confirming a positive rank correlation between MMSE in older subjects and age in children. The normalized WR2 between the two variables was 0.5724, and the F-statistic 872.4 ( ) with 787 degrees of freedom. The residuals can be inspected in Supplemental Figure 6.

Considering the model is trained to output MMSE scores, 90.87% of the predictions fell within developmental age intervals that agree with the RH boundaries proposed in Reiseberg et al. (1999). 1 Figure 2A highlights in green the predictions, equivalent to MMSE scores, coherent with the respective age of the subjects, according to the RH. Moreover, when dividing the predictions by groups of MMSE score ranges [0, 19], [19, 24], and [24, 30], and the ages by group ranges [0, 8], [8, 13], and [13, 19], a confusion matrix (Figure 2B) showed a of 522.27 ( ), further supporting a strong dependence between both variables, in line with the RH.

Figure 2.

Accuracy of the numerical predictions in dataset P according to the known boundaries between MMSE and developmental age. A) Regression of Figure 1 where the predictions highlighted in green, when considered as MMSE scores, are coherent with the developmental ages proposed by the RH. B) Confusion matrix when considering a classification task with 3 counterpart groups of corresponding MMSE scores and developmental age intervals.

Understanding EEG features importance for cognitive status in both populations

The trained ML model works as a function that, given 80 EEG features from any subject, outputs a single value, predictor of the cognitive status of that subject. The 80 determined EEG features were selected in the process of minimizing the error of this function. Hence, a careful analysis of these features is necessary to understand how they form structures and patterns present in the data that are associated with cognitive status in both populations.

By computing the Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI) of each feature given the examples of the older dataset used to train the model, we can sort each of the 80 features by importance. The 15 features with the highest MDI are shown in Figure 3A, making them the most important features to make accurate MMSE estimations in the older population. The Hjorth complexity at T3, the Edge Frequency at O2 in the beta band, and the theta COH between the frontal right and parietal left lobes were found to be the most important features.

Figure 3.

Most important features given by the trained model on the older dataset (left, A) and by the permutation testing on the children's dataset (right, B). On the left, feature importance is given by the mean decrease in impurity. On the right, feature importance is given by the non-decrease in error when permutating the respecting feature. The absolute values of both scales are not directly comparable. Highlighted in color are the features in common.

The MDI is computed from the state of the model's parameters after being trained with the older people dataset, and does not reveal which features were more important for accurate predictions in dataset P – for that we conducted permutation testing. Figure 3B shows the 15 most important features according to permutation testing. The Hjorth complexity at T3, the delta COH between frontal right and temporal left lobes, and the alpha COH between temporal left and right lobes revealed to be the most important features for accurate regression with age in the children's population.

Inferences must derive from a rank analysis and relative distances in importance, since the methods used to compute the feature importance in each population are different, and the importance values themselves are not on the same scale. Figure 3 links and color-highlights the intersection between these two sets of features. In this intersection, there were 8 out of 15 features in common, making them of primary interest for understanding the resting-state electrophysiological similarities of the brain during maturation and during degeneration.

To further assess how each feature affects the regression of children's EEGs, we analyzed their partial dependence plots (PDPs), which show how changes in each feature influence predictions. This approach helps reveal if relationships are linearly straightforward or more complex. 43 For each feature plot, we varied its values, predicted outcomes, and averaged results while holding other features constant. Figure 4 shows the six features with the overall steepest PDP slopes, indicating they provide clear decision boundaries. Notably, 5 out of these 6 features were among the most important features identified in common for both populations. The first two features in the upper panel of Figure 4 exhibit roughly positive slopes (monotonically non-decreasing) relationships, whereas the remaining features display roughly negative slopes (monotonically non-increasing) relationships. This analysis provides insights into the individual effects of these features on the model's predictions, highlighting their significance in understanding cognitive function across both populations.

Figure 4.

Partial dependence plots (PDPs) with highest positive (top panel) and negative (bottom panel) slope. In each PDP, the x-axis depicts the range of values each feature can take, and the y-axis shows the influence of each value the feature can take on the predicted outcome of the model, while holding all other features constant. The steepness of the slope indicates the strength of the feature's influence on the predicted outcome. All dataset P examples were evaluated on the trained full-dataset model.

EEG coherence, Hjorth, and spectral biomarkers of cognitive status

The EEG coherence between the right frontal lobe and the left temporoparietal regions in the delta and theta bands were identified by the permutation testing as the most important coherence features. Their significance extended to the older population in the theta band, as depicted in Figure 3. These theta features also exhibited high slopes in their PDPs (Figure 4), which is further supported by the distribution of these features in the children's EEGs: Figure 5 shows in blue their distributions on the children's EEGs and in red their distribution on the EEGs from the older population. In both features, the ANOVA p-value is below 0.05 among the three MMSE groups in the older population, and similarly below 0.05 among the three age groups in the children's population. This indicates that the three group distributions within each population are significantly different for both features. Each plot also includes the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic, with an asterisk denoting a p-value below 0.05, between each distribution counterpart of the two populations. The relatively low KS values (except for 0.44 between MMSE 0–15 and age 0–8 in Frontal(R)-Temporal(R)) suggest that distribution pairs were alike at corresponding stages of development and dementia, indicating that these two features link the two populations in terms of cognitive function. These features alone have a predictive influence on cognitive function, a distinction not shared by the remaining COH features of Feature 4 (ANOVA p = 0.12; not shown).

Figure 5.

Distribution of coherence (COH) features with significant predictive power for cognition over three MMSE and age counterpart groups. A) COH between right frontal and left temporal lobes in theta band; B) COH between right frontal and left parietal lobes in theta band. For each feature, all examples were normalized. Red is the distribution of the older population, and blue is the distribution of the children's population. Quartiles 1, 2 and 3 are drawn for the joint distributions of both populations. The KS statistic between each MMSE/age counterpart is given above each violin (* if KS ).

Figure 6 presents the grand-average topographic maps of the values of the Hjorth Complexity at T3 and the beta Edge Frequency at O2 for both populations – two of the most important features. The Hjorth Complexity at T3 is markedly low in the higher MMSE score range (average for the older dataset between MMSE scores of 13 and 28) and resembles the topology of children aged 6 to 13. Conversely, the average value at T3 increases in the lower MMSE score range, similar to the average value for children aged 6 years or younger. For the Edge Frequency in the beta band, the average value at O2 decreases from the higher to the lower MMSE score range. Likewise, the topology in the higher MMSE score range is like that of children aged 6 to 13, and the average O2 value for children aged 6 or younger also decreases, mirroring the pattern in the older population. This suggests that these two features might serve as a link between the two populations concerning cognitive function.

Figure 6.

Topographic maps of Beta Edge Frequency (left, A) and Hjorth complexity (right, B), over two MMSE and age counterpart groups. For each feature, all examples were normalized. Cohort mean values are presented for the highlighted channels of interest. A) Channel O2 is highlighted, showing a positive correlation between its mean value and both MMSE and age. B) Channel T3 is highlighted, showing a negative correlation between its mean value and both MMSE and age.

Interactions between features

The pairwise correlation among the 15 most important features, as well as their correlation with MMSE score and age, is evaluated in Figure 7. The left map focuses on the most important features identified in Figure 3A, while the right map focuses on those in Figure 3B. Correlations in the lower triangle of these matrices are computed using the EEGs from the older dataset, whereas the upper triangle correlations are derived from EEGs of the pediatric dataset. Only real examples are used without oversampling. A notable degree of symmetry is observed between the upper and lower triangles in both the left (Cosine Similarity = 0.773) and right (Cosine Similarity = 0.856) maps, indicating that the interactions between these features are quite similar across both populations.

Figure 7.

Correlation maps between the most important features and target variables. A) Pair-wise Pearson correlation between the important features found in Figure 3A. B) Pair-wise Pearson correlation between the important features found in Figure 3B. In both matrices, in the lower triangle correlations were computed on the older dataset feature vectors, whereas in the upper triangle correlations were computed on the pediatric dataset feature vectors.

Furthermore, we computed two-way PDPs to examine how feature pairs jointly affect predictions. Monotonic relationships emerged, reflecting pair-wise correlations, such as between the theta coherence of the right frontal and left parietal lobes and the delta COH of the right frontal and left temporal lobes, as well as between Hjorth Mobility at O1 and gamma COH of the right frontal and left parietal lobes (Supplemental Figure 7A). Complex, sometimes quasi-linear, interactions were observed, especially involving Hjorth Mobility at O1 with various COH features and spectral entropy/edge frequency in the occipital lobe with COH/PLI features (Supplemental Figure 7B and 7C). Such interactions suggest these feature pairs enhance predictive power, notably for children's regression, even if individual predictive strength is limited. For instance, alpha COH between left and right temporal lobes, though highly ranked for both groups, displayed non-linear correlations with targets; its interactions with Hjorth Mobility at O1 and theta COH between the right frontal and left temporal lobes highlight its importance in the model (Supplemental Figure 7D).

Discussion

A novel ML strategy was devised to test the hypothesis that the functional brain processes in dementia mirror in reversed order those of brain development in children. Based on resting-state EEG (rsEEG) features, a regression model was trained to predict global cognitive status in older participants, using their MMSE scores. The trained model was then applied on the same rsEEG features of children and adolescents, producing predictions that were then compared with their ages. This model allowed us to identify EEG features predictors of cognitive function shared by both populations and frame them in the context of the retrogenesis hypothesis (RH). These common features are of vital importance to understand how cognitive decline in dementia relates with cognitive development in childhood.

Temporal Hjorth complexity as a measure of cognitive status

Hjorth Complexity at the left temporal region emerged as the most important feature in both populations (Figure 3) for estimating global cognitive status. A negative correlation between Hjorth Complexity at T3 and MMSE scores in adults (r = -0.58), as well as a negative correlation with age in children (r = -0.45) was shown in Figure 7. These findings highlight distinct yet interconnected processes of neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration, which align with the RH.

The observed negative correlation with children's age, where Hjorth Complexity decreases as children grow older, can be explained by developmental processes related to neural plasticity and cortical specialization. During early childhood, the brain exhibits high plasticity, characterized by abundant synaptic connections and less efficient neural circuits.44–46 Figure 6B showed that temporal Hjorth Complexity is initially higher in younger children and decreases as they grow. Since the Hjorth Complexity measures rapid changes in cortical frequencies, capturing local variability and chaos, 47 the observed decrease suggests less temporal EEG chaos as children grow. As the brain matures, synaptic pruning refines cortical networks, reducing redundant connections and optimizing communication pathways. 48 This process leads to a decrease in Hjorth Complexity over time, reflecting a shift from diffuse, plastic networks to more efficient, organized and specialized ones. 49 Moreover, Figure 6B shows that this decrease occurs bilaterally in the temporal lobes – regions heavily involved in language and memory functions – suggesting this decrease represents a reorganization of cortical circuits into more stable, less chaotic and efficient configurations that support these higher-order cognitive processes.

In contrast, Hjorth Complexity at T3 increases as MMSE scores decrease in adults with cognitive decline (Figure 6B). This finding aligns with Jiao et al. (2023), 33 where Hjorth Complexity correlated negatively with MMSE (r = -0.42). This complexity surge parallels reduced electrophysiological entropy in AD, indicating a shift toward unstable, irreversible, and non-equilibrium dynamics. 50 As dementia advances, the brain undergoes abnormal synaptic loss and neuronal death,51,52 leading to network disorganization. Functional MRI and EEG studies demonstrate reduced small-world architecture in AD networks, characterized by diminished local clustering and inefficient global integration. 53 The increase in temporal Hjorth Complexity reflects this maladaptive state, with the breakdown of hierarchical organization of brain networks, 54 neural circuits losing their specialization, 52 reflecting a failure to maintain stable neural activity patterns necessary for effective memory and language function. Magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies corroborate this, showing disrupted inter-frequency hubs in the cingulate cortex, which are critical for cross-frequency coupling during memory tasks. 53 This increase in temporal chaos mirrors childhood, but this time as consequence of synaptic and neuronal loss rather than a healthy dynamism.

In children, decreasing complexity reflects the refinement of neural circuits through synaptic pruning and specialization. In adults with cognitive decline, the opposite occurs: neural circuits lose their specialization and become less efficient, resulting again in increased Hjorth complexity. This inverse relationship between aging-related neurodegeneration and childhood neurodevelopment supports the RH by highlighting how EEG patterns reflect opposing trends across these two processes.

Spectral coherence along the lifespan

Spectral coherence features dominated the most predictive features identified separately for the older participants and the children (Figure 3). Notably, five of these coherence features shared a common strong predictive influence for both populations. Particularly, the theta coherences between right frontal and left temporoparietal regions emerged as key features in both populations. Theta coherence (4–7 Hz) plays a critical role in large-scale inter-regional communication of cortical and subcortical networks. 55 Higher coherence in this band indicates stronger synchronization and more effective communication across a specific pair of regions. The inverted tendencies shown in Figure 5 can be explained by the distinct opposite trends in inter-regional communication between the frontal and temporoparietal regions.

Specifically, as children grow older, theta coherence was shown to decrease (Figure 5). Early in development, higher theta coherence indicates stronger synchronization among these brain regions, which is crucial for processes such as memory encoding, language acquisition, and executive function, problem-solving and learning. 56 Once more, this heightened coherence in younger children reflects immature but highly plastic neural circuits that rely on broad inter-regional communication to support cognitive development.56–58. As children grow older, synaptic pruning and cortical specialization refine these networks56,59,60, leading to more efficient and localized connectivity, as indicated by the decrease in theta coherence with age. The developmental decrease In theta coherence reflects the brain's transition from diffuse Inter-regional communication to more specialized local processing 58 .

In contrast, we observe an increase in theta coherence with cognitive decline in adults, inverting the trend observed in neurodevelopment and brain maturation in children. However, this increase does not signify healthy synchronization but rather reflects network dysregulation and maladaptive neural activity. Previous studies have consistently reported elevated theta power and coherence in ADD and MCI, for instance, in mid-frontal and posterior cingulate cortices 61 , suggesting hypoactivation of the default mode network (DMN). These increases are not associated with improved cognition but instead mark a slowing of oscillatory activity linked to pathological processes62,63.

In one hand, temporal and parietal regions are heavily involved in episodic memory encoding and retrieval. fMRI and EEG studies demonstrate that the lateral parietal cortex (LPC) reactivates memory content during retrieval 64 , with parietal theta-gamma coupling facilitating sensory integration and spatial memory 65 , processes impaired in AD. In the other hand, frontal regions play a critical role in executive function, modulating working memory and attentional resources. Right frontal theta coherence during spatial attention tasks reflects top-down coordination with parietal regions, a mechanism disrupted in AD66,67. Therefore, the observed increase in theta coherence between these regions may reflect compensatory mechanisms where remaining networks attempt to synchronize activity to offset functional deficits. In early AD, residual frontal networks may upregulate theta coherence to offset temporoparietal dysfunction. Enhanced frontal gamma connectivity in prodromal stages correlates with preserved cognitive scores, implying initial compensatory efforts62,68.

However, this compensation is often inefficient and unsustainable as neurodegeneration progresses, resulting in impaired cognitive performance and exacerbating executive dysfunction 66 . Elevated inter-regional theta coherence correlates with poorer memory performance, indicating futile hyperactivation62,65. In temporal lobe-epilepsy (TLE), analogous theta-gamma coupling increases pre-ictally but precipitates seizures, illustrating how maladaptive synchronization exacerbates network failure 63 . Similarly, AD patients’ frontal overactivation fails to rescue hippocampal-parietal connectivity loss. As parietal and temporal hubs degenerate, their capacity to synchronize with frontal executive networks diminishes, leading to disorganized theta activity and cognitive decline68,69.

The opposing trends observed between children and adults highlight the inverse relationship between neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes. In children, decreasing theta coherence reflects the refinement of neural circuits through synaptic pruning and specialization. In adults with cognitive decline, increasing theta coherence signifies a breakdown of efficient connectivity due to synaptic loss and neuronal degeneration. This inversion supports the RH by demonstrating how EEG biomarkers capture opposing trends across these two processes.

EEG-based cognitive predictors alignment with existent mechanisms

These findings align with established evidence showing alterations in rsEEG rhythms during AD progression, specifically increases in slower rhythms (e.g., delta and theta) and decreases in faster rhythms (e.g., alpha)70–73. Besides the key features already discussed, Figure 7 shows other features in the delta and theta bands (e.g., delta coherence frontal right – temporal left) negatively correlating with age in children and MMSE in adults, and alpha features (e.g., alpha coherence temporal left – temporal right) positively correlating with age in children and MMSE in adults. These changes have been interpreted as abnormal synchronization at slow frequencies (<7 Hz) in cortical pyramidal neurons, driven by neurons in the thalamocortical and corticothalamic circuits that exhibit bursting action potentials at these slow frequencies74,75. This bursting mode inhibits information processing in thalamocortical and corticothalamic neurons due to the relatively long intervals of membrane hyperpolarization (inhibition) between action potential bursts 75 . As a result, there is a disruption in functional connectivity involving cholinergic basal forebrain, thalamic, and visual cortical networks from the early stages of the disease 76 .

Our findings in Hjorth complexity and theta coherence may seem counterintuitive at first due to the child development mirroring in dementia being explained primarily by maladaptation mechanisms. However, the spectra of our EEG data align with existing spectral markers observed in neurodegeneration and neurodevelopment, validating their good quality and utility. Our older dataset confirmed delta and theta relative power increases and alpha power decreases with AD progression (Supplemental Figure 8A-C), a peak activity shift often characteristic of AD 51 . In children and adolescents, delta and theta relative powers decreased with age, while alpha power became more prominent, consistent with the literature77–79. The alpha peak frequency also increased in children from approximately 8 to 10 Hz as visual processing abilities developed 80 (Supplemental Figure 8D). Therefore, other delta, theta and alpha specific patterns in our findings are plausible given the data follows the established spectral landmarks that characterize the progression of AD and other dementias.17,66,70,73,81–85

Limitations

The linear model fitted to the children's predictions (Subsection 3.3) revealed that about 57% of the variation in global cognitive status in children could be explained by their chronological age. This relationship was statistically significant (p < 0.001), but 43% of the variation remained unexplained. Several factors may contribute to this unexplained variance, from the target variables used (MMSE and age), to cofactors not considered, to ML modelling and tuning. While valuable insights into dementia EEG landmarks can be derived, some methodological limitations must be acknowledged.

Usage of MMSE scores in adults

The use of MMSE scores in older adults to quantify global cognitive status has inherent limitations, that may impact its sensitivity and specificity in detecting cognitive impairments, particularly in diverse populations. First, the MMSE shows reduced sensitivity in detecting early and prodromal stages of cognitive decline compared to other tools such as the MoCA 86 . Second, the MMSE is influenced by educational level, potentially leading to false positives in individuals with lower education and false negatives in those with higher education. This educational bias highlights a critical limitation when applying the MMSE across populations with varying educational systems. Third, cultural and linguistic differences can further affect MMSE accuracy, particularly language-dependent and culturally-specific items, limiting its applicability in cross-cultural research. Additionally, the MMSE provides limited insight into subtle language deficits and executive function domains (e.g., planning, organization, and higher-order decision-making), which a) are among the first abilities affected in neurodegenerative diseases and b) can be particularly affected in patients with significant cognitive deficits. Finally, differences in administration and scoring based on examiner experience or interpretation introduce an additional layer of subjectivity into what should ideally be an objective assessment. Moreover, subjective factors such as fatigue levels, emotional state, or anxiety during testing can influence MMSE results, hindering the accurate assessment of individuals’ true cognitive abilities. Despite these limitations, the MMSE remains a pragmatic choice for large-scale studies due to its standard and widespread use in clinical and research settings for assessing global cognitive function. Its widespread adoption facilitates comparisons across studies and datasets. In this study, it was selected for being readily available across datasets and aligning with our objective of investigating broad patterns of neurodegeneration. Future studies should consider integrating more comprehensive neuropsychological assessments to provide a more nuanced understanding of specific cognitive domains and improve sensitivity to early-stage cognitive decline.

Usage of age in children

Chronological age was used as a proxy for cognitive function in children, an assumption supported by the exclusion criteria of the pediatric cohort. However, age does not account for individual variability in developmental trajectories. Factors such as genetic predisposition, environmental influences, and socioeconomic status can result in significant differences among children of the same age87,88. For instance, while most children reach certain milestones at expected ages, some may achieve them earlier or later due to these external factors. This variability introduces noise into the model and may limit its ability to capture nuanced aspects of cognitive function. Moreover, chronological age is not the same as developmental age, which can be more accurately measured with markers such as brain age or epigenetic clocks. Whenever possible, future research should incorporate additional measures of developmental or cognitive age, alongside chronological age to better account for individual variability.

Drawing parallels between adults’ MMSE and children's age

The direct comparison between MMSE scores in older adults and chronological age in children provides valuable insights but demands careful interpretation to avoid oversimplifying the complexity of the neurodegenerative and neurodevelopment processes. These two variables serve as proxies for cognitive function but differ fundamentally in their nature and sensitivity. First, the MMSE is a performance-based marker of cognitive decline, while chronological age is a developmental marker of cognitive maturation. As aforementioned, MMSE primarily assesses global cognitive function through tasks related to memory, orientation, and language, while chronological age reflects broader developmental milestones that are influenced by education and environmental factors. Although both measures were used to align EEG patterns across populations, the cognitive processes being measured by MMSE in adults and those inferred from chronological age in children may not be fully equivalent. Second, scaling issues arise when comparing these variables. Neither the relationship between MMSE and cognitive function is linear, nor the relationship between chronological age and cognitive development is linear. This makes the relationship between MMSE in adults and age in children also non-linear, therefore expecting an R2 of 1.00 in Figure 2A is unrealistic. Our simulations suggest that 0.81 would be the optimal case for this dataset, according to the association described in Reisberg et al. (2002) 2 . In fact, studies that have applied the MMSE to children, albeit inappropriately, suggest that MMSE scores are not linearly related to age but exhibit a quasi-linear relationship89,90. Nonetheless, our regression analysis revealed a weighted R2 of 0.57 and a significant correlation (r = 0.73) between EEG-based cognitive status and chronological age in children, sufficiently strong evidence to support the RH.

Demographic and cognitive diversity across adult cohorts

EEG shows potential to estimate cognitive status across adult populations with diverse demographic and cognitive profiles. However, the variability in adult cohorts may introduce biases. For example, Cohort A included participants from France with SMCs, while Cohort B included participants from Greece spanning a broader cognitive spectrum. These differences in geography, culture, and cognitive reserve could influence EEG patterns and hinder the model's ability to generalize. Combined with this variability, the imbalance in MMSE distributions across cohorts may impact the model's learning process by limiting its exposure to certain cognitive states. Despite these challenges, capturing such diversity is essential for developing ML models that are generalizable to real-world populations. Similar EEG-based approaches have been successfully implemented in diverse settings, such as international networks like ReDLat and UL-BCRN, which have demonstrated their utility in detecting dementia-related changes across varied socio-cultural contexts 91 . To mitigate potential biases introduced by cohort variability, we employed stratified data splitting by MMSE score, age, and gender during cross-validation to ensure balanced representation within training and test sets. While demographic variability may influence predictions, it is important to note that in the ML context, the impact of such biases tends to decrease as dataset size grows. Future studies should incorporate sufficiently large datasets to enhance generalizability 92 , perhaps encompassing even greater diversity, better capturing the full spectrum of demographic and cognitive profiles of real-world populations.

Pediatric cohort variability

The inclusion of children and adolescents with mental and behavioral symptoms and conditions in the pediatric cohort may introduce potential variability in EEG features unrelated to typical cognitive development. However, this decision was made to ensure that our sample reflects real-world pediatric populations, as overly restrictive exclusion criteria could lead to a non-representative subset 25 . Importantly, the most relevant EEG features analyzed in this study are not specific to these disorders, reducing the likelihood of significant confounding effects. Nonetheless, we acknowledge this variability as a potential limitation, and future research should consider stratifying analyses by subgroups or incorporating additional covariates to control for these influences.

Impact of oversampling strategies

Another potential source of bias in our results stems from the use of oversampling techniques to address MMSE score imbalances. While these introduce synthetic variability into the data, this variability was controlled to remain minimal, akin to noise in electrophysiological recordings. Moreover, the synthetic examples are derived from real examples, ensuring that they reflect plausible EEG patterns rather than artificial constructs. Importantly, to prevent overestimation of model performance, we followed the “Train on Synthetic, Test on Real” (TSTR) methodology, where oversampling is applied only to the training data within each cross-validation fold, while the test fold remained unaltered. This ensured no data leakage and provided a realistic assessment of model performance. While oversampling can influence results, it is a common approach to achieve sufficient resolution for regression learning. Future studies should resolve dataset imbalances commonly found in clinical datasets.

Variability in EEG acquisition protocols

The EEG datasets used in this study were acquired across multiple centers using different instruments, electrode layouts, and acquisition systems. Although we applied a uniform preprocessing pipeline to mitigate these differences, variability in signal quality and impedance across datasets may influence the results. For example, the pediatric dataset was obtained from clinical routine diagnostics rather than research-specific protocols, which introduced additional heterogeneity in recording conditions. While these differences were minimized by focusing exclusively on eyes-closed resting-state segments and applying strict quality control measures (Supplemental Material Section II), residual variability cannot be entirely ruled out.

The role of EEG in a comprehensive AD model and future directions

The rsEEG features found in this study contribute to a deeper understanding of the neurophysiological oscillatory mechanisms underlying the retrogenesis pattern. The inverse correlations observed in Hjorth complexity and theta coherence provide strong support for RH by demonstrating how EEG biomarkers capture opposing trends during neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration. These findings suggest that EEG biomarkers not only reflect structural changes but also capture functional shifts in neural dynamics that are consistent with the RH's framework. However, these features do not fully explain the retrogenesis process, as that would underestimate the complexity of neurodegenerative mechanisms and developmental processes. These processes may involve a dynamic interplay of neuropathological, neuroinflammatory, cerebrovascular, and neurodegenerative factors, further influenced by individual risk and resilience factors, including genetics and cognitive brain reserve 93 . A comprehensive systems model of AD requires a panel of neurobiological, neuropathological, and neuroanatomical biomarkers94,95. Our exploratory findings extend this model, improving our electrophysiological understanding of AD.

The present results may support multiple innovative research directions. Firstly, EEG-based dementia biomarkers may contribute to decision support tools available to areas without specialized staff or expensive equipment. The temporal Hjorth complexity can serve as a noninvasive indicator of subtle neurodegenerative changes. Shifts in complexity may emerge even before pronounced clinical symptoms are observed, making this parameter valuable in longitudinal monitoring 96 . Measuring inter-regional theta coherence can help detect early network changes that precede, or accompany, cognitive decline, potentially aiding in the identification of patients at higher risk of progressing from MCI to AD. Additionally, integrating these EEG features with other modalities, such as structural or functional MRI, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of their neurobiological underpinnings.

Secondly, since AD patients tend to exhibit disrupted global and local network connectivity, especially in the DMN, continuously recording specific EEG connectivity features might enhance our understanding on the disruption of brain connectivity throughout the natural course of dementia as well as its pre-clinical stages. Moreover, longitudinal EEG studies that track changes in brain connectivity, which can be translated to global cognitive status, will help to identify when significant cognitive declines are likely to occur.

Conclusion

Carried out by a novel ML strategy, the same brain rsEEG patterns were directly mapped between older adults and a younger population of children and adolescents. Using the same EEG features, a significant positive rank correlation was found between the MMSE score of older adults and the chronological age of younger subjects. The most predictive features of global cognitive status were left temporal Hjorth complexity from large-band activity and anterior-posterior inter-hemisphere theta coherence. In children, decreasing Hjorth complexity and theta coherence reflect the refinement of neural circuits through synaptic pruning and specialization. In adults with cognitive decline, increasing Hjorth complexity and theta coherence signify network disorganization and maladaptive changes caused by synaptic loss. These exploratory findings offer new insights and align with established EEG landmarks and known pathophysiological processes in AD and neurodevelopment, particularly highlighting the role of slower theta rhythms in frontal and temporoparietal networks, linked to cognitive decline in aging and cognitive enhancement during normal development. The shared predictive power of the presented biomarkers across both populations underscores their potential as universal indicators of cognitive health and supports the RH. Future research should focus on validating these biomarkers in larger cohorts and exploring their utility in estimating reserve of specific cognitive domains.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-alz-10.1177_13872877251352119 for Electroencephalogram features support the retrogenesis hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: Exploratory comparison of brain changes in aging and childhood by João Areias Saraiva, Martin Becker, Martin Dyrba, Burcu Bölükbaş, Enrico Michele Salamone, Claudio Babiloni, Michael Kölch, Harald Hampel, Stefan Teipel, Thomas Kirste and Christoph Berger in Journal of Alzheimer's Disease

Acknowledgments

The Authors acknowledge Greta Kirstein for her invaluable contribution in managing and interpreting the KJPP EEG recordings (cohort P).

We thank the members of the INSIGHT-preAD study group (cohort A): Audrain C, Auffret A, Bakardjian H, Baldacci F, Batrancourt B, Benakki I, Benali H, Bertin H, Bertrand A, Bombois S, Boukadida L, Cacciamani F, Causse V, Cavedo E, Cherif Touil S, Chiesa PA, Chupin M, Colliot O, Dalla Barba G, Depaulis M, Dos Santos A, Dubois B, Dubois M, Epelbaum S, Fontaine B, Francisque H, Gagliardi G, Genin A, Genthon R, George N, Glasman P, Gombert F, Habert MO, Hampel H, Hewa H, Houot M, Jungalee N, Kas A, La Corte V, Le Roy F, Lehericy S, Letondor C, Levy M, Lista S, Lowrey M, Ly J, Makiese O, Mangin JF, Masetti I, Mendes A, Metzinger C, Michon A, Mochel F, Nait Arab R, Nyasse F, Perrin C, Poirier F, Poisson C, Potier MC, Ratovohery S, Revillon M, Rojkova K, Santos-Andrade K, Schindler R, Servera MC, Seux L, Simon V, Skovronsky D, Thiebaut M, Uspenskaya O, Vergallo A, Villain N, Vlaincu M, Younsi N.

We thank Dharmendra Jahkar, Susanna Lopez, and Giusepper Noce from Sapienza University of Rome for providing the Sapiezna EEG dataset and associated documentation (cohort B).

We also thank the research groups that made datasets C and D publicly available.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: João Areias Saraiva https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3715-0304

Martin Becker https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4296-3481

Martin Dyrba https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3353-3167

Burcu Bölükbaş https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3941-3019

Enrico Michele Salamone https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9619-7455

Claudio Babiloni https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5245-9839

Michael Kölch https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2878-5121

Harald Hampel https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0894-8982

Stefan Teipel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3586-3194

Thomas Kirste https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8956-9820

Christoph Berger https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0832-5526

Ethical considerations: For the datasets provided to us by third parties, the study protocols were approved by the local institutional review boards and ethical committees, as detailed in INSIGHT et al. (2018), 19 Babiloni et al. (2022), 20 Miltiadous et al. (2021), 21 and Prado et al. (2023). 22 For the dataset acquired at the University Medicine Rostock, the local ethics committee approved the usage of the data for this research study (IRB-Board Approval #A 2018-0121).

Consent to participate: For the datasets provided to us by third parties, written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their representatives prior to data acquisition. For the dataset acquired at the University Medicine Rostock, written informed consent was waived by the local ethics committee, since the data was acquired during clinical routines and fetched retrospectively for research use, guaranteeing all records were anonymized.

Author contributions: João Areias Saraiva: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Visualization; Writing – original draft.

Martin Becker: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Martin Dyrba: Formal analysis; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Burcu Bölükbaş: Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Enrico Michele Salamone: Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Claudio Babiloni: Formal analysis; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Michael Kölch: Project administration; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Harald Hampel: Resources; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Stefan Teipel: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Thomas Kirste: Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Christoph Berger: Data curation; Resources; Software; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was mainly funded by the European Union's HORIZON – Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) Doctoral Networks 2021 program, under the grant agreement number 101071485 of the CombiDiag MSCA Doctoral Network. This study also received funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under grant number 01IS22077.

Part of data collection for this project was conducted at the Sorbonne University, Paris, France, supported (awarded to H.H.) by the AXA Research Fund, the “Fondation partenariale Sorbonne Université” and the “Fondation pour la Recherche sur Alzheimer,” Paris, France. Ce travail a bénéficié d’une aide del’Etat “Investissements d’avenir” ANR-10-IAIHU-06. The research leading to these results has received funding from the program “Investissements d’avenir” ANR-10-IAIHU-06 (Agence Nationale de la Recherche-10-IA Agence Institut Hospitalo Universitaire-6). This manuscript benefited from the support of the Program “PHOENIX,” led by the Sorbonne University Foundation and sponsored by la Fondation pour la Recherche sur Alzheimer (awarded to H.H.). Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, , HORIZON EUROPE Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: S.T. was member of advisory boards for Lilly, Eisai, Biogen, and GE Healthcare. He is member of the Independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board of the study ENVISION (Biogen). H.H. is an employee of Eisai Inc.; however, this article does not represent the opinion of Eisai. H.H. declares no competing financial interests related to the present article, and his contribution to this article reflects only and exclusively his academic and scientific expertise as part of an academic appointment at Sorbonne University, Paris, France. He serves as a Reviewing Editor and previously as Senior Associate Editor for the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia. Part of this study was initiated and developed in line with the Alzheimer's Precision Medicine Initiative (APMI) and Neurodegeneration Precision Medicine (NPMI) framework. The remaining authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement: Dataset A was collected in the context of the INSIGHT pre-AD study, which by the time of submission is now concluded; however, data may be available upon request to Bruno DUBOIS (bruno.dubois@aphp.fr). Dataset B an in-house dataset, collected at University Sapienza Rome, and it is available upon request to Claudio Babiloni (claudio.babiloni@uniroma1.it). Dataset C is a public dataset available at https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds004504/versions/1.0.2. Dataset D is a public dataset available at https://www.synapse.org/Synapse:syn51549340/wiki/624187. Dataset P is an in-house dataset and may be available to share upon request to Christoph Berger (christoph.berger@med.uni-rostock.de).

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Reisberg B, Franssen EH, Hasan SM, et al. Retrogenesis: clinical, physiologic, and pathologic mechanisms in brain aging, Alzheimer’s and other dementing processes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999; 249: S28–S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reisberg B, Franssen EH, Souren LEM, et al. Evidence and mechanisms of retrogenesis in Alzheimer’s and other dementias: management and treatment import. Am J Alzheimers Dis Demen 2002; 17: 202–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, Anand R, et al. Functional staging of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1984; 435: 481–483. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie C, Fong MC-M, Ma MK-H, et al. The retrogenesis of age-related decline in declarative and procedural memory. Front Psychol 2023; 14: 1212614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gayraud F, Loureiro IS, Frouin C, et al. Lexical deterioration in Alzheimer’s disease. In: 10th International Conference of Experimental Linguistics, Lisbonne, Portugal, pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mello CBD, Abrisqueta-Gomez J, Xavier GF, et al. Involution of categorical thinking processes in Alzheimer’s disease: preliminary results. Dement Neuropsychol 2008; 2: 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simoes Loureiro I, Lefebvre L. Retrogenesis of semantic knowledge: comparative approach of acquisition and deterioration of concepts in semantic memory. Neuropsychology 2016; 30: 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakebeeke TH, Chaouch A, Caflisch J, et al. Comparing neuromotor functions in 45- and 65-year-old adults with 18-year-old adolescents. Front Hum Neurosci 2023; 17: 1286393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]